Jean v. Nelson Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jean v. Nelson Brief for Petitioners, 1984. 39a5e722-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/583b0b76-a81d-438f-8ebd-ed19ea5ba26d/jean-v-nelson-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

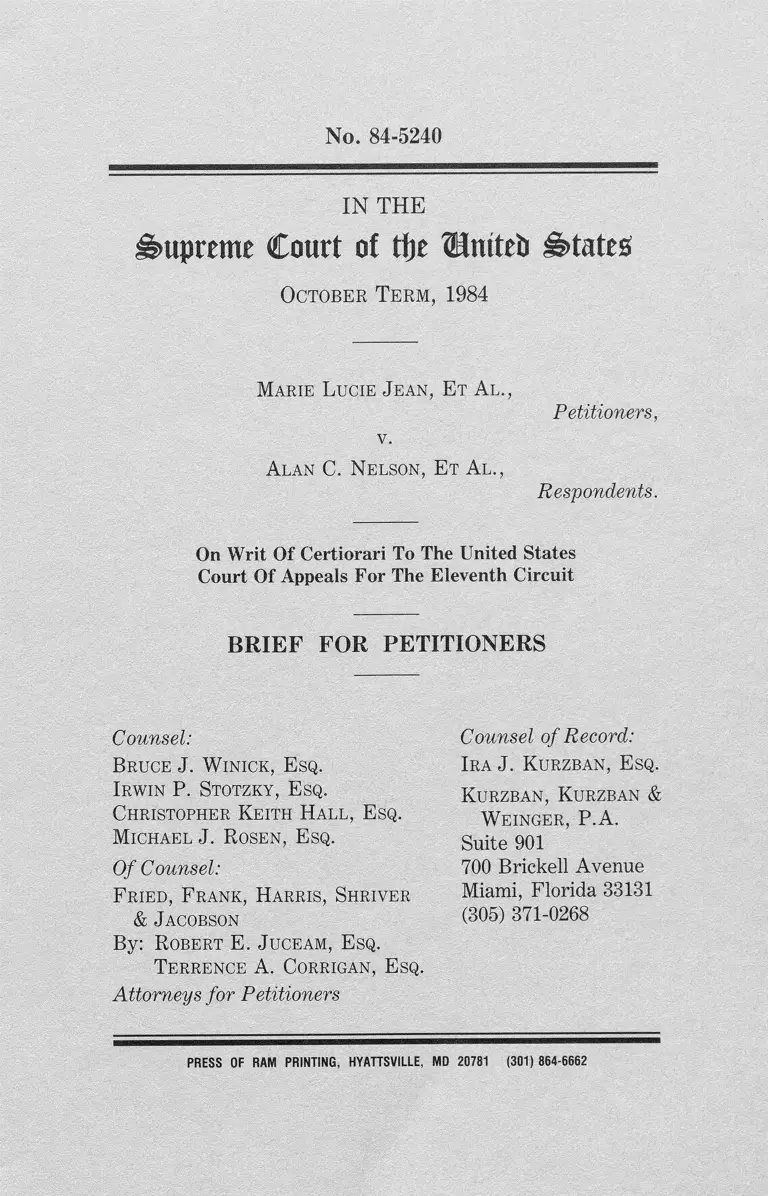

No. 84-5240

IN TH E

Supreme Court of tfje ®lntteb States;

October T e r m , 1984

Marie Lucie J ean, E t A l.,

Petitioners,

v.

A lan C. N elson, E t A l.,

Respondents.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States

Court Of Appeals For The Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Counsel:

Bruce J. W inick, E sq.

Irwin P. Stotzky, E sq.

Christopher Keith Hall, E sq.

Michael J. Rosen, E sq.

Of Counsel:

F ried, F rank, Harris, Shriver

& Jacobson

By: Robert E. Juceam, E sq.

Terrence A. Corrigan, E sq.

Attorneys for Petitioners

Counsel of Record:

Ira J. Kurzban, E sq.

Kurzban, Kurzban &

Weinger, P.A.

Suite 901

700 Brickell Avenue

Miami, Florida 33131

(305) 371-0268

PRESS OF RAM PRINTING, HYATTSVILLE, MD 20781 (301) 864-6662

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED1

Is invidious discrimination on the basis of race and national

ity by immigration enforcement officials, acting pursuant to

neutral statutes and directives, in the incarceration of ex

cludable black Haitian refugees in detention camps, wholly

beyond constitutional scrutiny?

Whatever judicial deference may be accorded the actions of

Congress and the President in exercising their authority to

admit or exclude aliens, does such deference wholly preclude

constitutional review of the established invidiously discrimina

tory conduct of low-level government officials in regard to

non-admission questions?

Does Shaughnessy v. United States ex rel. Mezei, 345 U.S.

206 (1953), have continuing validity, and should it be extended

to permit invidious discrimination based on race and national

origin by Immigration and Naturalization Service enforcement

officials in the incarceration of aliens pending a determination

of their asylum claims? 1

1 The parties to the proceedings are listed below. The petitioners

are: Marie Lucie Jean, Lucien Louis, Herold Jacques, Jean Louis

Servebien, Pierre Silien, Wilner Luberisse, Job Dessin, Joel Casmir,

Serge Verdieu, Milfort Vilgard, and the heirs of Prophete Tal

leyrand, on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated. Mr.

Talleyrand committed suicide during the pendency of this suit while

being held in detention by the Immigration and Naturalization Ser

vice.

The respondents are: Alan C. Nelson, Commissioner, Immigration

and Naturalization Service; Perry Rivkind, District Director,

Immigration and Naturalization Service, District VI; Leonard Row

land, Assistant District Director for Deportation, Immigration and

Naturalization Service, District VI; Franklin Graves, Immigration

and Naturalization Service, Officer in Charge, Krome Avenue North

Detention Facility; The Immigration and Naturalization Service; and

William French Smith, Attorney General of the United States.

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Au th o rities .......... ........................................ jv

Opinions Below .............. i

J urisdictional Statem ent .................................................. 1

Constitutional And Statutory P rovisions Involved 2

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 3

1. The Petitioners And The Applicable Statutory, Reg

ulatory And Treaty Provisions ................................. 4

2. The Genesis Of The Case ............................................ 7

3. The Announced, Facially N eutral Detention Policy 7

4. The Detention Policy Applied To Haitians: Proof Of

Discrimination Under Arlington Heights ............... 10

a. Statistical And Non-Quantitative Evidence Of

A Disproportionate Impact ............................... 11

b. Historical Background Of D iscrim ination___ 14

c. O ther Factors Under Arlington Heights ___ 16

d. No Justification Existed Or Was Offered For

The Proven Invidious Discrimination Against

P e titio n e rs .............................................................. 17

5. The Devastating Effect Of Incarceration ............... 18

Summary of Argument . . . ........ 21

Argum ent................................................................................. 24

I. Black Haitian Refugees Are E ntitled to E qual

P rotection of The La w .............. .............................. 24

A. Excludable Aliens Are “Persons” Protected By

The Fifth Amendment ....................................... 25

B. None Of The Cases Cited By The Lower Court

Could Possibly Justify A Finding That Petition

ers Are Not Persons Within The Meaning Of

The Fifth Amendment ....................................... 28

Page

Ill

Table of Contents Continued

Page

II. Permitting Constitutional Scrutiny of D iscrimi

natory Incarceration by Immigration E nforce

ment Officials of E xcludable A liens Pending A

D etermination of Their A dmissibility W ould

N either Hamper the E xecutive’s E nforcement

of Immigration Laws N or Interfere W ith the

Sovereign A uthority of Congress and the Presi

dent To Decide W ho W ill Be Permitted E ntry

Into Our Society .......................................................... 29

A. The Considerations Of National Sovereignty

And Separation Of Powers That Insulate Deci

sions Concerning Admission Of Aliens Into Our

Country From Close Judicial Scrutiny Do Not

Apply To Decisions Concerning Incarceration

Of Aliens Pending A Determination Of Their

Admissibility.............................. ............ ......... 31

B. Since Even Congressional And Presidential

Decisions Concerning The Admission Of Aliens

Are Subject To Constitutional Scrutiny, Dis

crim inatory Incarceration By Subordinate

Agency Officials Must Be Subject To Con

stitutional R ev iew ............................................. 36

III. T he L ower Court Improperly R elied U pon

Shaughnessy v. United States E x R el. Mezei,

345 U. S. 206 (1953), Which Is N ot Controlling and

The U nderlying Premises of Which Have Been

Rejected ........................................................................... 39

A. Mezei Does Not Control This C a s e ................ 40

B. The Underlying Premises Of Mezei Have Been

Rejected By Subsequent Constitutional Devel

opments ........................... 44

Conclusion ............................................................................... 46

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967)

Page

45

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Develop

ment Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) ........ii, 10, 12, 15, 16

Augustin v. Sava, 735 F.2d 32 (2d Cir. 1984) .............. 26

Balzac v. Porto Rico, 258 U.S. 298 (1922) .................... 26

Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535 (1971)............................... 45

Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564 (1972) ........... 45

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) ......................... 44

Carlson v. Landon, 342 U.S. 524 (1952) .................... 29, 30

The Chinese Exclusion Case, 130 U.S. 581 (1889) . . . 23, 36

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857) . 4

Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. (4 Wall.) 281 (1866) . 26, 36, 39

Fiallo v. Bell, 430 U.S. 787 (1977) ...................... 23, 35, 36

Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U.S. 698 (1893) 34, 36

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970) ........................ 45

Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565 (1975)................................. 45

Greenholtz v. Inmates of Neb. Penal & Correctional

Complex, 442 U.S. 1 (1979) ................................. ... 34

Haitian Refugee Center v. Civiletti, 503 F. Supp. 442

(S.D. Fla. 1980), affd as modified sub nom. Haitian

Refugee Center v. Smith, 676 F.2d 1023 (5th Cir.

1982)........................................................................... 5, 16

Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, 426 U.S. 88

(1976) ..................................................... 23, 36, 37, 38

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954)...................... 24

Hudson v. Palmer, 104 S. Ct. 3194 (1984) .................... 24

The Japanese Immigrant Case (Kaoru Yamataya v.

Fisher), 189 U.S. 86 (1903)....................................... 26

Jean v. Meissner, 90 F.R.D. 658 (S.D. Fla. 1981) ___ 1

Jean v. Nelson, 105 S.Ct. 565 (1984) ........................... 1; 21

Jean v. Nelson, 733 F.2d 908 (11th Cir. 1984).............. 1

Jean v. Nelson, 727 F.2d 957 (11th Cir. 1984)........passim

Jean v. Nelson, 711 F.2d 1455 (11th Cir. 1983) . . . . passim

V

Jean v. Nelson, 683 F.2d 1311 (11th Cir. 1982)............ 1

Kaplan v. Tod, 267 U.S. 228 (1925) ........................... 32, 43

Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144 (1963) .. 45

Kleindienst v. Mandel, 408 U.S. 753 (1972) ........ 34-35, 40

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214

(1944) .......................................................... 25, 30, 36, 39

Kwong Hai Chew v. Colding, 344 U.S. 590 (1953) .. 28, 29

Landon v. Plasencia, 459 U.S. 21 (1982) ...................... 28

Lee v. Washington, 390 U.S. 333 (1968) ....................... 24

Leng May Ma v. Barber, 357 U.S. 185 (1958) . 6, 8, 22, 32

Louis v. Meissner, 532 F. Supp. 881 (S.D. Fla. 1982) . 1

Louis v. Meissner, 530 F. Supp. 924 (S.D. Fla.

1981) ......................................... . 1, 4, 16, 18, 20

Louis v. Nelson, 544 F. Supp. 1004 (S.D. Fla.

1982) ........................................................... 1, 4, 17, 31, 33

Louis v. Nelson, 544 F. Supp. 973 (S.D. Fla.

1982) ............................................................. 1, 6, 8, 12, 19

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137

(1803) .................................................................. 36, 38-39

Mathews v. Diaz, 426 U.S. 67 (1976) ......................... 25, 26

Meachum v. Fano, 427 U.S. 215 (1976) ....................... 34

National Council of Churches v. Egan, No. 79-2959-CIV-

WMH (S.D. Fla. 1979)........‘ .................................... 16

National Council of Churches v. Immigration and

Naturalization Service, No. 78-5163-CIV-JLK(S.D.

Fla. 1979) .................................................................... 16

New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713

(1971) ............................. ................................................ 45

Nishimura Ekiu v. United States, 142 U.S. 651

(1892) ........................................................................ 28, 34

Oyler v. Boles, 368 U.S. 448 (1962) ............................... 43

Patmore v. Sidoti, 104 S.Ct. 1879 (1984) ..................... 24

Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982) ........... 22, 25, 26, 27

Table of Authorities Continued

Page

VI

Regents of the Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265(1978) 38

Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1 (1957) ........................ 26, 36, 45

Rodriguez-Fernandez v. Wilkinson, 654 F.2d 1382 (10th

Cir. 1981) ..................................................................... 26

Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545 (1979) ........................... 24

Russian Volunteer Fleet v. United States, 282 U.S. 481

(1931) .......................... .................................... 26, 27, 28

Sannon v. United States, 460 F.Supp. 458 (S.D. Fla.

1978) ........................................................................... 15-16

Sannon v. United States, 427 F.Supp. 1270 (S.D. Fla.

1977), vacated and remanded on other grounds, 566

F.2d 104 (5th Cir. 1978) ........................................... 15

Shaughnessy v. United States ex rel. Mezei, 345 U.S. 206

(1953) ............ passim

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Education, 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ........................... 21

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) ................................. 45

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U.S. 312 (1921) ....................... 24

United States v. De?nanett, 629 F.2d 862 (3d Cir,), cert,

denied, 450 U.S. 910 (1980) ...................................... 26

United States v. Henry, 604 F.2d 908 (5th Cir. 1979) . 26

United States v. Pink, 315 U.S. 203 (1942) .................. 26

United States ex rel. Knauff v. Shaughnessy, 338 U.S.

537 (1950)........................................................... 28, 34, 45

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) .................... 10

Wong Wing v. United States, 163 U.S. 228 (1896) .. passim

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) . . . 12, 24, 25, 26

Yiu Sing Chun v. Sava, 708 F.2d 869 (2d Cir. 1983) .. 26

Table of Authorities Continued

Page

Constitutional, Statutory A nd Treaty Provisions:

U.S. Const., amend. V. ................ ............ ........ . . . . passim

5 U.S.C. § 553 ...................... . 7, 20, 33

8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(42) ....................................................... 44

Table of Authorities Continued

Page

8 U.S.C. § 1152(a) ........

8 U.S.C. § 1158 ............

8 U.S.C. § 1182 ............

8 U.S.C. § 1182(a)........

8 U.S.C. § 1182(d)(5)(A)

8 U.S.C. § 1182(f) ........

8 U.S.C. § 1225(b)

8 U.S.C. § 1253(h)

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) . . . .

. . . 8, 44

5

. passim

. . . 35

. passim

9, 38, 40

6

2

United Nations Convention and Protocol Relating to the

Status of Refugees, done January 31,1967,19U.S.T.

6223, T.I.A.S. 6577 (entered into force with respect to

the United States, Nov. 1, 1968) ..................... 5, 9, 44

R ules A nd Regulations:

8C .F .R . § 208.1 ............................................................... 5, 6

8 C.F.R. § 208.3 ................................................................ 5

8 C.F.R. § 236.3 ................................................................ 5

8 C.F.R. § 242.17(c) .......................................................... 5

Other A uthorities:

111 Cong. Rec. H21765, H21778, S24446, S24482-83,

S24781 (1965) .............................................................. 8, 9

111 Cong. Rec. H21759, H21764, H21787, S24238, (1965) 44

2 Davis, Administrative Law (2d ed. 1979) .................. 46

Hart, The Power of Congress to Limit the Jurisdiction of

Federal Courts: An Exercise in Dialectic, 66 Harv.

L. Rev. 1362 (1953) .................................................. 45

Hearings on S. 500, 89th Cong., 1st Sess., Part 1 (1965) 44

Helton, The Most Ambitious Pro Bono Ever Attempted,

12 Hum. Rts. 19 (1984) ............................................. 33

Martin, Due Process and Membership in the National

Community: Political Asylum and Beyond, 44 U.

Pitt. L. Rev. 165 (1983) . ' . ......................................... 46

Vlll

Page

Note, Constitutional Limits on the Power to Exclude

Aliens, 82 Colum. L. Rev. 957 (1982) .................... 46

Schuck, The Transformation of Immigration Law, 84

Colum. L. Rev. 1 (1984) ........................................... 46

S. Rep. No. 590, 96th Cong. 2d Sess. (1980) ................ 44

Statement of the President, U.S. Immigration and Refu

gee Policy, July 30, 1981 ......................................... 8, 10

L. Tribe, American Constitutional Law (1978)............ 37

V an Alstyne, The Demise of the Rights-Privilege Distinc

tion in Constitutional Law, 81 Harv. L. Rev. 1439

(1968)............................................................................ 45

Table of Authorities Continued

OPINIONS BELOW

On December 3, 1984, this Court granted certiorari and

petitioners’ motion to proceed in forma pauperis. Jean v.

Nelson, 105 S.Ct. 563 (1984) (J.A. 358).

On May 4, 1984, the United States Court of Appeals for the

Eleventh Circuit denied petitioners’ request for a rehearing of

its en banc decision, Jean v. Nelson, 733 F.2d 908 (11th Cir.

1984) (J.A. 355)1 and entered its final judgment on rehearing en

banc, which is not reported. (J.A. 356). The en banc court’s

opinion is reported. Jean v. Nelson, 727 F.2d 957 (11th Cir.

1984) (“Jean II”) (J.A. 292). The panel opinion is reported.

Jean v. Nelson, 711 F.2d 1455 (11th Cir. 1983) (“Jean I”) (J.A.

193). The decision of the court of appeals denying the govern

ment’s request for a stay is also reported. Jean v. Nelson, 683

F.2d 1311 (11th Cir. 1982) (J.A. 191).

The district court’s final judgment is reported, Louis v.

Nelson, 544 F. Supp. 1004 (S.D. Fla. 1982) (“Louis IV”) (J.A.

175), as is its opinion. Louis v. Nelson, 544 F.Supp. 973 (S.D.

Fla. 1982) (“Louis III”) (J.A. 112). Other earlier opinions of the

district court are also reported, including its decision dismiss

ing several claims before trial on jurisdictional grounds, Louis

v. Meissner, 532 F. Supp. 881 (S.D. Fla. 1982) (“Louis II”)

(J.A. 78), its decision enjoining exclusion hearings against

unrepresented incarcerated class members, Louis v. Meiss

ner, 530 F.Supp. 924 (S.D. Fla. 1981) (“Louis I”) (J.A. 58), and

its decision permitting petitioners’ amended petition and com

plaint. Jean v. Meissner, 90 F.R.D. 658 (S.D. Fla. 1981).

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

This case seeks review of the decision of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit en banc entered on

February 28, 1984. (J.A. 292). On May 4, 1984, that court

1 “J.A .” refers to the Joint Appendix to the briefs on the merits in

this case.

2

denied petitioners’ request for rehearing en banc (J.A. 355),

and entered its judgment. (J.A. 356). Petitioners filed a timely

petition for certiorari on August 1, 1984. The petition was

granted by this Court on December 3, 1984.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1254(1) (1982).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED

Petitioners’ claims are based on the equal protection guaran

tee of the due process clause of the fifth amendment to the

United States Constitution, and 8 U.S.C. § 1182(d)(5)(A)

(1982). These provisions are set forth below:

U.S. Const., amend. V:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or

otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or

indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the

land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual

service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any

person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in

jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any

criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be de

prived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of

law; nor shall private property be taken for public use,

without just compensation.

8 U.S.C. § 1182(d)(5)(A) (1982):

The Attorney General may, except as provided in sub-

paragraph (B), in his discretion parole into the United

States temporarily under such conditions as he may pre

scribe for emergent reasons or for reasons deemed strictly

in the public interest any alien applying for admission to

the United States, but such parole of such alien shall not be

regarded as an admission of the alien and when the pur

poses of such parole shall, in the opinion of the Attorney

General, have been served the alien shall forthwith return

or be returned to the custody from which he was paroled

and thereafter his case shall continue to be dealt with in

the same manner as that of any other applicant for admis

sion to the United States.

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case challenges the Eleventh Circuit’s unprecedented

holding that invidious race and national origin discrimination in

the incarceration of black Haitian refugees by low-level

immigration enforcement officials is wholly immune from con

stitutional scrutiny. Petitioners do not challenge the authority

of the Congress, the President, the Attorney General, or even

of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (“INS”) to

admit or exclude aliens. They do not challenge the proposition

that the Constitution limits neither the grounds on which an

alien seeking initial admission may be excluded, nor the proce

dures employed in making that determination. Indeed, peti

tioners do not even challenge the authority of INS to maintain a

policy of detaining excludable aliens on a non-discriminatory

basis. Petitioners challenge only the authority of INS enforce

ment officials to discriminate invidiously in decisions concern

ing the incarceration of excludable aliens pending a determina

tion of their claims to asylum. As the record in this case

demonstrates, without contradiction, INS officials have dis

criminated invidiously against black Haitian refugees in decid

ing to incarcerate them initially, and in prolonging their in

carceration without parole pending a determination of their

asylum claims.

Notwithstanding what a panel of the Eleventh Circuit found

to be overwhelming and unrebutted evidence establishing a

stark pattern of invidious discrimination,2 the en banc court

held that excludable aliens such as Haitian petitioners may not

assert the equal protection component of the fifth amendment

2 The en banc court, without questioning or disturbing, Jean II

(J.A. 295), the detailed factual findings of invidious discrimination

made by a panel of the Eleventh Circuit, Jean I (J.A. 246-276, 290),

proceeded to decide the constitutional question: “whether the Hai

tian plaintiffs may invoke the equal protection guarantee of the fifth

amendment’s due process clause as a basis for challenging the

government’s refusal to grant them parole.” Jean II (J.A. 296). It,

therefore, implicitly concurred in the panel’s factual findings that the

evidence established intentional discrimination.

4

against such practices. This holding—that excludable aliens

are outside the protection of the Constitution—is not only

unprecedented, but it is at war with our nation’s history,

values, and constitutional traditions.3 Moreover, no circum

stance of this case—not the race or nationality of petitioners,

not their status as excludable aliens, and not the government’s

interests—could possibly justify the en banc court’s decision.

1. The Petitioners And The Applicable Statutory, Regula

tory And Treaty Provisions

Petitioners, approximately 2,000 black Haitian asylum

seekers,4 are part of the first substantial flight of black re

fugees who have come to our shores seeking political asylum.

They made “a long and perilous journey” over eight hundred

miles of open sea, Louis I (J. A. 61), to escape the harsh political

3 Not since the Dred Scott decision, Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60

U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), has this or any other court ever held thata

class of persons is wholly immune from constitutional protection. Nor

has any court, except for the en banc Eleventh Circuit’s opinion, ever

held that invidiously discriminatory incarceration is immune from all

constitutional review.

4 The district court certified the class as:

All Haitian aliens who have arrived in the Southern District of

Florida on or after May 20, 1981, who are applying for entry into

the United States and who are presently held in detention pend

ing exclusion proceedings at various INS detention facilities, for

whom an order of exclusion has not been entered and who are

unrepresented by counsel.

Louis I (J. A. 69). The class was later amended in the Final Judgment

to include all Haitians in detention for whom a G-28 (counsel’s notice

of appearance form) had been filed. Louis IV (J. A. 176). Although the

district court released many class members from detention, a sub

stantial number of class members still are being held in detention.

Jean II (J.A. 296).

5

conditions in Haiti. Our government,5 including our courts6 as

well as international organizations and other observers,7 have

repeatedly recognized the repressive political conditions from

which these Haitians fled. Upon their arrival in the United

States, many of the petitioners sought asylum and requested

they not be sent back to Haiti because they feared persecution

or death.8

Under our law, any alien, regardless of race or nationality,

has a statutory, regulatory and treaty right to seek asylum if

he has a well founded fear of persecution, 8 U.S.C. § 1158, 8

C.F.R. §§ 208 et seq., 236.3, or if his life or freedom would be

threatened if returned to his country of origin. 8 U.S.C.

§ 1253(h), 8 C.F.R. § 208.3, § 242.17(c), United Nations Pro

tocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, done January 31,

1967, 19 U.S.T. 6223, T.I.A.S. 6577 (entered into force with

5 Record (“R.”) at Vol. 51, pp. 2568-2570 (testimony of Steven

Cohen, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, Bureau of Human

Rights and Humanitarian Affairs between 1977-1980, that the

United States Embassy in Haiti and other U.S. government depart

ments that had studied the issue had concluded that “Haiti was highly

repressive and there is virtually no or little political freedom in

Haiti.”).

6 Haitian Refugee Center v. Civiletti, 503 F.Supp. 442, 450 (S.D.

Fla. 1980) (“Haitians have flocked to the shores of South Florida

fleeing the most repressive government in the Americas”), affd as

modified sub nom. Haitian Refugee Center v. Smith, 676 F.2d 1023

(5th Cir. 1982).

7 Petitioners’ Exhibit (“Px.”) 129 (R. at Vol. 52, pp. 2774, 2775,

2781), Px. 164 (R. at Vol. 52, pp. 2773, 2775, 2781), Px. 165 (id,),

168-174,177 (R. at Vol. 52, pp. 2796-98; Vol. 53, p. 2863), Px. 184 (R.

at Vol. 52, pp. 2773, 2775, 2781); R. at Vol. 52, pp. 2769-2799 (testi

mony of Patricia Rengel, Director of the Washington Office of

Amnesty International); R. at Vol. 51, pp. 2654-2748 (testimony of

Michael Hooper, Director of the Haitian Project of the Lawyers

Committee for International Human Rights).

8See, e.g., R. at Vol. 46, pp. 1720-1721 (testimony of Pierre Silien);

R. at Vol. 46, p. 1734 (testimony of Henrick Desulme).

6

respect to the United States, Nov. 1,1968), Art. 33. Excludable

aliens, such as the Haitian petitioners, are accorded these

rights whether they arrive at our shores by boat or by other

means. 8 C.F.R. § 208.1. The process for determining asylum

claims is complex and often takes many months,9 in sharp

contrast to the relatively immediate determinations that are

made by the thousands daily in non-asylum exclusion cases.

Although Congress permitted the Attorney General to in

carcerate aliens on a non-discriminatory basis during the

determination of an alien’s claim, 8 U.S.C. § 1225(b), the stat

ute does not require incarceration and was not read to require

incarceration by INS officials from 1954 until this case. Leng

May Ma v. Barber, 357 U.S. 185, 190 (1958); Louis III (J.A.

150-53); R. at Vol. 38, pp. 123-130,151, 211-217; Vol. 40, p. 611;

Vol. 45, p. 1613. Indeed, Congress specifically provided that

excludable aliens, such as petitioners, could be paroled10 pend

ing a d e term ina tion of th e ir adm issib ility . 8 U .S .C .

§ 1182(d)(5). Prior to the events of this case, excludable aliens

seeking asylum pending determinations of their claims were

routinely paroled under this statute, regardless of race or

nationality. R. at Vol. 38, pp. 173-175; Vol. 40, p. 606; Vol. 41,

p. 819. This case arose precisely because INS officials denied

parole to black Haitian asylum seekers based on their race and

nationality, in contrast to all other excludable aliens, including

similarly situated asylum seekers entering Florida from Cuba

and Nicaragua. In short, INS applied Congress’ intent to per

mit temporary release pending a determination of admissibil

ity, as expressed in 8 U.S.C. § 1182(d)(5)(A), to all except

black Haitian refugees.

9R. at Vol. 38, pp. 186-87 (testimony of Charles Gordon).

10 The word “parole” has two entirely separate meanings in

immigration law. Only temporary parole is involved here. The parole

involved is not parole into the country in the sense of admission, but

ra th e r tem porary release from physical custody pending a

determination of asylum or final excludability.

7

2. The Genesis Of The Case

This case began in response to the actions of INS officials

during the week of June 1-5, 1981, in holding mass exclusion

“hearings” for Haitian refugees seeking asylum in the United

States. The respondents held these hearings behind locked

courtroom doors and intentionally barred pro bono counsel

who sought access to the Haitians. INS officers deliberately

routed Haitians being brought to the INS courtroom from the

detention center through back stairwells and immigration

offices at a double-time pace, to avoid lawyers known to be

waiting in public areas of the courthouse offering to provide

them with free legal assistance. The subsequent hearings, held

without lawyers, and marred by inaccurate and misleading

translations, prevented the Haitians from understanding the

proceedings or being informed of their rights. Jean I (J.A.

195); Louis I (J.A. 60-62); R. at Vol. 45, pp. 1596-98.

On June 10, 1981, petitioners—a class of black Haitian re

fugees seeking asylum—filed an emergency habeas corpus

petition challenging the procedural fairness of these hearings

and the discriminatory treatment applied only to Haitians.

After a hearing that documented the procedural irregularities

and the inaccurate, misleading translations of the mass hear

ings, the government confessed error, but not before respon

dents improperly deported eleven Haitians. Jean I (J.A. 195).11

3. The Announced, Facially Neutral Detention Policy

At approximately the same time that these unlawful actions

took place, the Administration established a new policy of

detention for excludable aliens.11 12 In discussing this policy, high

11 The government admitted that these procedures “were faulty

and not in compliance with law.” Jean I (J.A. 195).

12 It did so without complying with the rulemaking requirements of

the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553 (1982) (“APA”), as

the district court and Eleventh Circuit panel found. Jean I (J.A.

8

ranking members of the Executive branch spoke with a single

voice: they publicly proclaimed that the policy of detention

should be applied evenhandedly to all aliens seeking asylum.

In describing this new policy to the Congress, the Attorney

General called for an “evenhanded” rule of detention. Jean I

(J.A. 212). At the same time, the President confirmed that

administrative action was to be “consistent with fair proce

dures and our constitution,” and “consistent with our values of

individual privacy and freedom.” Statement of the President,

United States Immigration and Refugee Policy, July 30, 1981

at 829, cited in Jean I (J.A. 208-09). The Associate Attorney

General and third-ranking official at the Department of Jus

tice, bearing primary responsibility for immigration, testified

at trial that if the detention policy was being applied in a

discriminatory manner, that was contrary to the intent of the

Attorney General, and that any official doing so should be

reprimanded or dismissed. Jean I (J.A. 217); R. at Vol. 49, p.

2343. Furthermore, congressional policy strongly condemned

invidious discrimination by the INS on the basis of race and

nationality in all immigration m atters.13 Although Congress

219-37); Louis III (J.A. 220-37). This abruptly changed a long

standing policy, in effect since 1954, of releasing all aliens pending a

determination of their admissibility unless the alien was likely to

abscond or posed a threat to national security. Jean I (J.A. 207-08);

Leng May Ma v. Barber, 357 U.S. at 190.

13 In 1965, Congress abolished the national origin quota system and

special immigration restrictions relating to Orientals, and forbade

discrimination based on race, sex, nationality, place of birth or place

of residence in all immigration matters. Act of October 3, 1965, P.L.

89-236, 76 Stat. 911, 8 U.S.C. § 1152(a) (1982). Indeed, members of

Congress compared this legislation to the Civil Rights Act. See, e.g.,

111 Cong. Rec. S24781 (Sept. 22,1965) (“Last year the Congress took

a great step toward the elimination of racial discrimination against

American citizens here at home. . . . This immigration reform bill is

no less a civil rights measure. It will end four decades of intolerance

toward those who seek shelter on our shores, and who, until they

9

gave the President authority to impose restrictions on the

entry of any class of aliens found detrimental to the United

States, 8 U.S.C. § 1182(f),14 this grant of authority was con

ditioned on his issuance of a proclamation. Here, however, the

have actually sought entrance, have looked upon our nation as a

refuge and a haven from intolerance.”) (remarks of Sen. Tydings);

111 Cong. Rec. H21765 (Aug. 25,1965) (“I would consider the amend

ments to the Immigration and Nationality Act to be as important as

the landmark legislation of this Congress relating to the Civil Rights

Act. The central purpose . . . [of the bill] is to once again undo

discrimination. . . .”) (remarks of Rep. Sweeney). The legislative

history is replete with denunciations of race and nationality as

criteria in the administration of our immigration laws. See, e.g., I l l

Cong. Rec. S24482-83 (Sept. 20, 1965) (‘‘It will eliminate from the

statute books a form of discrimination totally alien to the Constitu

tion. Distinctions based on race or national origin assume what our

law, our traditions and our common sense deny: that the worth of

men can be judged on a group basis.”) (remarks of Sen. Kennedy); id.

at S24446 (Sept. 20, 1965) (“Elimination of racial barriers against

citizens of other lands is a logical extension of eliminating discrimina

tion against American citizens.”) (remarks of Sen. Fong).

In 1968, the United States acceded to the United Nations Protocol

Relating to the Status of Refugees, done January 31, 1967, 19 U.S.T.

6223, T.I.A.S. 6577 (entered into force with respect to the United

States Nov. 1, 1968), provisions of which specifically prohibit dis

crimination against refugees on the grounds of race or national ori

gin. For example, Article 3 of the Protocol specifically provides: “The

Contracting States shall apply the provisions of this Convention to

refugees without discrimination as to race, religion or country of

origin.” The provisions include a prohibition against refoulment (Art.

33), restriction of movement (Art. 31(2)), and against penalizing an

alien for his method of entry (Art. 31(1)). The accession by Congress

to the Protocol shows Congress’ commitment to a non-discriminatory

policy in dealing with asylum seekers such as the Haitian petitioners.

148 U.S.C. § 1182(f) states:

Whenever the President finds that the entry of any aliens or of

any class of aliens into the United States would be detrimental to

the interests of the United States, he may by proclamation, and

1 0

President neither issued any such proclamation nor made any

finding as to the petitioners or any other racial or nationality

group. Despite the Attorney General’s publicly expressed in

tention, the President’s statement, and congressional policy

providing for facial neutrality and nondiscriminatory applica

tion of parole under 8 U.S.C. § 1182(d)(5)(A)(1982),* 15 INS

enforcement officials applied this facially neutral policy dis-

criminatorily against the Haitians, resulting in their prolonged

incarceration.16

4. The Detention Policy Applied To Haitians: Proof Of Dis

crimination Under Arlington Heights

The record reveals an overwhelming and unrebutted stark

pattern of discrimination against Haitian refugees sufficient to

meet the most exacting requirements for proving intentional

discrimination. Jean I (J.A. 246-76, 290). See Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429

U.S. 252 (1977); Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976).

Petitioners proved that INS enforcement officials intentional

ly discriminated against black Haitian nationals in initially

incarcerating them, and in keeping them in prolonged in

carceration pending a determination of their claims to political

asylum. Jean I (J.A. 276). Petitioners proved intentional dis

crimination both directly and indirectly through witnesses,

for such period as he shall deem necessary, suspend the entry of

all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrants or nonimmigrants,

or impose on the entry of aliens any restrictions he may deem to

be appropriate.

15The legislative history of 8 U.S.C. § 1182(d)(5)(A) centers on

non-discriminatory factors such as reuniting families and releasing

detainees for medical reasons. Jean II (J.A. 348) (Kravitz, J., con

curring and dissenting).

16 Unlike excludable aliens of other nationalities who were not

incarcerated or, in a small percentage of cases, were incarcerated

only briefly (usually less than 72 hours), Haitians were incarcerated

for prolonged periods of time. Indeed, in most cases, the incarcera

tion of Haitians lasted up to one year. Jean I (J.A. 195).

1 1

documents, and expert statistical analysis of data provided by

respondents. Jean I (J.A. 274).

a. Statistical And Non-Quantitative Evidence Of A Dispro

portionate Impact

At trial, petitioners introduced a wealth of statistical evi

dence which confirmed the vastly disproportionate impact of

the INS detention policy on Haitian aliens as compared with

other similarly situated excludable aliens seeking asylum, such

as Cubans and Nicaraguans. Petitioners’ statistical expert,

Dr. Gitlow, examined several sets of data, all of which were

supplied by the government. One set of data contained

secondary inspection logs at the Miami airport between Au

gust 1,1981 and April, 1982. Px. 186 (R. at Vol. 53, p. 2873; R.

at 2986), Px. 187 (R. at Vol. 53, pp. 2875, 2885; R. at 2986), Px.

188 (R. at Vol. 53, pp. 2876-2920; R. at 2986). Dr. Gitlow

analyzed three separate compilations of this data to ensure

accuracy. He found in each of these compilations that the

probability of so many more Haitians than non-Haitians being

detained, or so many fewer Haitians paroled, was “on the order

of less than two in ten billion times.” Jean I (J.A. 248); R. at

Vol. 53, p. 2948. In some cases, it was “far less than one in ten

billion,” Jean I (J.A. 248); R. at Vol. 53 p. 2949, and equalled

approximately 17.6 standard deviations. Id. at 2951.

The second set of data reflected persons placed in exclusion

or in an exclusion catagory who sought entry into the United

States between August 1, 1981 and November 1, 1981. The

data was coded by nationality, documentation, attempted en

try, date of parole, length of detention, whether an asylum

claim was filed, family ties, and comments. Px. 189 (R. at Vol.

53, p. 2906), Px. 190 (id. pp. 2907-2920; R. at 2986), Px. 191 (R.

at Vol. 53, p. 2951; R. at 2986); Jean I (J.A. 248-49). Dr. Gitlow

performed binomial analysis on a number of compilations of

this data. He evaluated both detention versus parole and

length of detention. With regard to each data set, Dr. Gitlow

concluded that the chance that the disparate impact of the INS

detention policy on Haitians could have occurred at random

1 2

was “astronomically remote,” R. at Vol. 53, p. 2955, and that

the relationship between being Haitian and being detained was

“statistically significant.” Jean I (J.A. 249). Indeed, for some

of the data sets, Dr. Gitlow declined to calculate the standard

deviation because “it would be so large that my calculator

would not hold the numbers.” Jean 1 (J.A. 249); R. at Vol. 53,

pp. 2964-2965. Dr. Gitlow also performed multivariate, or Chi-

squared, analysis of this data to take account of the possible

impact of documentation status and other variables, and con

cluded that the relationship between being Haitian and being

detained remained statistically significant, after eliminating

the effects of these variables. Jean I (J.A. 249-50).

The third set of data, Px. 188 (R. at Vol. 53, pp. 2876-2920; R.

at 2986), Px. 193-196 (R. at Vol. 53, pp. 3016-18, 3029-30, 3033;

R. at 2986), taken from the government’s computer system at

the Krome detention camp, covered detention and parole be

tween January and April 1982. This data revealed that the

relationship between being Haitian and being detained was

highly statistically significant, Jean I (J.A. 250), with standard

deviations ranging from 7.64 to over 15. R. at Vol. 53, p. 3037.

Dr. Gitlow also analyzed data introduced by the government

and reached equally, if not more damaging, conclusions from

this evidence. Jean I (J.A. 250).

Petitioners’ statistical evidence showed such a disparate

impact on Haitians that, by itself, it demonstrated a pattern of

discrimination “as stark as that in Gomillion . . . or Yick Wo. ”

Jean I (J.A. 250-51) quoting Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at

266. In sum, the Administration’s new detention policy, in

tended to be neutral in coverage, was applied by INS enforce

ment officials to Haitians in a manner so disparate that expert

statistical testimony described the chances that the disparity

could have occurred at random as “a statistical joke.” Jean I

(J.A. 249).17

17 Indeed, even the district court found that it was “undisputed”

that the new detention policy had a disproportionate impact on the

petitioners. Louis 111 (J.A. 165).

13

Furthermore, testimony of witnesses and the government’s

own documents18 dramatically revealed that INS officials dis-

criminatorily targeted Haitians for incarceration, Jean I (J. A.

251-59), while releasing other excludable aliens similarly situ

ated. The most dramatic comparison was presented by the

treatm ent accorded Nicaraguan applicants. Robert Boyer, an

immigration attorney specializing in Nicaraguan asylum mat

ters (R. at Vol. 39, pp. 400-401), testified at length concerning

the treatm ent received by Nicaraguans who sought political

asylum in the United States and whose admissibility was chal

lenged. Id. at 400-450 et seq. In contrast to the treatment of the

Haitians, Boyer testified that very few, if any, Nicaraguans

had been placed in exclusion proceedings before they had the

opportunity to seek political asylum before the District Direc

tor. Id. at 405. Boyer testified that his Nicaraguan clients in

exclusion proceedings had been regularly released from in

carceration (id. at 418-419), and that other than one isolated

case of a Nicaraguan convicted of a cocaine charge, none of his

many Nicaraguan clients whose admissibility had been chal

lenged was subjected to prolonged incarceration. Id. at 420.19

Similarly, Frank Murray, an attorney who at the time of his

testimony had practiced immigration law in South Florida for

thirteen years, testified that his non-Haitian clients whose

admissibility was challenged at the airport were paroled into

the United States for their deferred inspection and were con

tinued on parole following the service of an order to show cause

why the alien should not be excluded, form 1-122. R. at Vol. 42,

18 See footnotes 23 and 24, infra.

19 This non-detention policy included individuals assisted by the

Nicaraguan Refugee Organization (R. at Vol. 39, p. 420), which

Boyer represented (id. at 401) and which had assisted 12,000 to

13,000 Nicaraguans since 1979. Id. at 403. Further, he testified that

the Nicaraguans, once questioned as to admissibility, were regularly

released. These included both documented and undocumented

Nicaraguans who arrived either by boat or at the airport. Id. at

449-450.

14

pp. 970-973. In contrast, Haitians were served with I-122s

shortly after their arrival (id. at 973-974), and were held in

detention pending a hearing. Id. at 974.

Finally, incarcerated Haitians provided poignant personal

testimony to the fact of discriminatory incarceration of Hai

tians as compared to other groups of similarly situated aliens,

such as Cubans, Colombians, and Mexicans. R. at Vol. 42, pp.

963-964; Vol. 43, pp. 1205, 1259; Vol. 46, p. 1690. Respondents

did not rebut, or even attempt to rebut, this testimony. Jean I

(J.A. 259).

b. Historical Background Of Discrimination

The discriminatory application of prolonged incarceration to

Haitians occurred in the context of a lengthy historical pattern

of discrimination by INS officials against black Haitian re

fugees. Jean I (J.A. 254). Numerous witnesses,20 including

“former high-ranking INS and Department of Justice officials

attested to the persistent targeting and mistreatment of Hai

20 Virtually from their initial landing on our nation’s shores, Hai

tians have been treated differently and far worse than all other

persons seeking asylum. Many witnesses and documents provided

unrebutted evidence of this discrimination. Ira Goilobin, a well

known immigration lawyer and counsel to the National Council of

Churches, testified to the persistent discriminatory treatment of

Haitians over ten years. Jean I (J.A. 254-55) R. at Vol. 40, p. 645 et

seq. Indeed, the discriminatory conduct toward Haitians by INS

officials has even been explicitly conceded by government officials. In

May 1979, the Deputy Associate Attorney General, in a memoran

dum to the General Counsel of INS, stated that “we should strive to

end the double standard that now seems to prevail between the

handling of these Haitian claims and those made by others.” Jean I

(J.A. 252); Px. 109a (R. at Vol. 40, pp. 656-657).

The discriminatory treatment of Haitians was also testified to by

Charles Gordon, a former General Counsel of the INS and the leading

authority on immigration law of the United States. Mr. Gordon

stated that he “never heard of a policy to single out any other

15

tian[s].” Jean I (J.A. 252). The “unrebutted and unexplained

testimony” showed “a historical pattern of discrimination

under Arlington Heights.” Jean I (J.A. 253-54).21

particular group other than Haitians,” R. at Vol. 38, p. 140, and that

he never heard of simultaneous scheduling of lawyers for any group

other than Haitians. Id. at 157-158; Jean I (J.A. 252).

Other knowledgeable witnesses testified to the disparate treat

ment of black Haitian refugees as compared to Cubans, Nicaraguans

and other groups seeking asylum between 1972 and 1980 in regard to

refugee status, release, work authorization, length of incarceration

and treatment in incarceration. See testimony of Monsignor Brian

Walsh, a well-known expert on refugee matters, Jean I (J.A. 252); R.

at Vol. 38, pp. 260-264; Larry Mahoney, the Public Affairs Officer for

the Department of State in the Cuban/Haitian Task Force from July

1980 to May 1981, Jean I (J.A. 253); R. at Vol. 43, pp. 1140-43,

1148-50; Jacqueline Rowe, an Equal Opportunity Officer for the

Community Action Agency of Metro-Dade County, Jean I (J.A. 253);

R. at Vol. 44, pp. 1355-72, 1385 et seq. In addition, the Mayor of

Miami, Maurice Ferre, stated that in his experience as a government

official he was aware there had been “indeed a differential in the way

Cubans were being treated and the Haitians.” JeanIQ. A. 252); R. at

Vol. 41, p. 787.

21 The present case is only the latest in a series of cases brought by

Haitians to challenge the disparate treatment of Haitian asylum

seekers as compared to other groups of refugees. All of these cases

demonstrate that Haitians historically have been the victims of law

less conduct by INS enforcement officials.

For over a decade, INS enforcement officials have systematically

denied Haitian refugees seeking asylum in this country their right to

the fair and impartial administration of our immigration laws. They

have unlawfully denied Haitians their statutory and treaty rights to a

hearing before an immigration judge in exclusion proceedings on

their claims for political asylum. Sannon v. United States, 427 F.

Supp. 1270 (S.D. Fla. 1977), vacated and remanded on other

grounds, 566 F.2d 104 (5th Cir. 1978). They have unlawfully denied

Haitians their right to notice of the procedures that the government

intended to use against them in exclusion proceedings. Sannon v.

16

c. Other Factors Under Arlington Heights

In addition to statistical and historical evidence, the record

demonstrated “a plethora” of other evidence of discriminatory

intent under Arlington Heigh ts, including departures from the

normal procedural sequence and administrative history. Jean

I (J.A. 251). For example, INS officials departed from their

normal procedures in the treatm ent of aliens by intentionally

cutting off the Haitians’ rights to claim asylum,22 and by deny

ing them fair hearings. Jeanl{J.A. 256n.40);Louis/(J .A . 63).

Further, the evidence of administrative history demon

strated that enforcement officials intentionally singled out

Haitians for discriminatory treatment. Jean I (J.A. 252). In

deed, the INS established a special code number for Haitians

which appeared “on a variety of documents alarming as to both

their number and content.” Jean I (J.A. 257).23 Internal docu-

United States, 460 F. Supp. 458 (S.D. Fla. 1978). They have

unlawfully denied Haitians the right to work during the pendency of

their asylum claims. National Council of Churches v. Egan, No.

79-2959-Civ-WMH (S.D. Fla. 1979). They have unlawfully denied

Haitians access to information to support their asylum claims. Na

tional Council of Churches v. Immigration and Naturalization

Service, No. 78-5163-Civ-JLK (S.D. Fla. 1979). They have unlawful

ly denied Haitians the very right to be heard on their asylum claims,

and have subjected them to a special “Haitian Program.” Haitian

Refugee Centers. Civiletti, 503 F. Supp. 442 (S.D. Fla. 1980), affd as

modified sub nom. Haitian Refugee Center v. Smith, 676 F.2d 1023

(5th Cir. 1982). They have unlawfully denied Haitians their right to

counsel and to fair process in their exclusion hearings by shipping

them, like cattle, to remote areas of America. Louis I (J.A. 60-62).

See Jean I (J.A. 287).

22 Px. 94 at 1 (R. at Vol. 38, p. 162) (“[Haitian] aliens will immedi

ately be served with Notice to Appear for exclusion hearings before

they can make asylum applications to the District Director, thus

cutting off that option.”).

23 See, e.g., Px. 80 (R. at Vol. 48, p. 2048), “Report as to status of

space for detention and prior surveys” (David Crosland, General

Counsel INS to David Hiller, Special Assistant to the Attorney

17

merits of the INS itself demonstrated an awareness that the

detention policy would have its greatest impact on black Hai

tians who amounted to a tiny fraction of aliens similarly situ

ated. Jean I (J.A. 258). Other INS documents demonstrated

that low-level officials singled out Haitians for disparate treat

ment both before and after the President adopted a uniform

detention policy in the summer of 1981. Jean I (J.A. 258).24

d. No Justification Existed Or Was Offered For The

Proven Invidious Discrimination Against Petitioners

Respondents never refuted any of the evidence of invidious

discrimination, except to protest that they did not intend to

discriminate. The incarceration of Haitians in an invidiously

discriminatory manner was also devoid of any justification.

The Haitians posed no threat to the national security, were not

likely to abscond, and represented an insignificant number of

undocumented aliens seeking entry into the United States.

Jean I (J.A. 255 n.38); Louis IV (J.A. 178). Indeed, the Hai

tians represented less than two percent of the undocumented

immigration into the United States. Jean I (J.A. 255 n.38).

General, 19 May 1981); Px. 86 (R. at Vol. 47, p. 1830), “Contingency

Plan for the Detention of Cubans/Haitians in Florida and Other

Locations” (Hugh J. Brian, Action Associate Commissioner,

Enforcement to Doris Meissner, Deputy Commissioner, 27 April

1981) (specifically referring to eliminating the right to apply for

asylum to the District Director); Px. 92 (R. at Vol. 47, p. 1834),

“Cuban/Haitian Policy” (Crosland to Hiller, 2 April 1981) (detention

of Haitians and Cubans); Px. 94 (R. at Vol. 38, p. 162), “Haitian

Policy” (Crosland to Kenneth Starr, Counselor to the Attorney

General, 20 March 1981) (deprive Haitians of the right to claim

political asylum before District Director; detention for Haitians de

spite fact that appeal process could extend over one year).

24 The best example of this is Px. 1 (R. at Vol. 38, pp. 138-39) a telex

from the Regional Commissioner, Dallas to INS District Director,

New Orleans, INS Associate Commissioner for Enforcement, and

INS Associate Commissioner for Detention and Deportation, dated

September 2, 1981, requiring that “Haitians . . . be detained . . . .”

18

Moreover, INS officials conceded that the Haitians were not

incarcerated because they were a threat to national security or

likely to abscond. R. at Vol. 43, p. 1160; Vol. 47, p. 2035; Vol.

49, pp. 2338, 2396, 2398.

Respondents did not attempt to justify their discriminatory

actions on these or on any other grounds. Rather, they merely

contended that they had not discriminated against the Hai

tians, a contention totally belied by the record. As the panel

opinion noted:

All told plaintiffs mustered an impressive array of witnes

ses and an equally impressive number of documents to

demonstrate circumstantially, and to an extent directly,

intentional government discrimination against Haitians.

This evidence, in addition to the statistical evidence, was

unrebutted but for the government’s testimonial evi

dence, which can at best be termed “mere protestation.”

Without evidence of similar mistreatment of other immi

grant groups, the district court had no factual basis for

finding these practices were directed at others, or that

they would be directed to others who were similarly situ

ated. Based on the lack of evidence, the district court’s

findings are clearly erroneous.

Jean I (J.A. 259).

5. The Devastating Effect Of Incarceration

INS officials discriminated against Haitians not only in the

initial and then prolonged incarceration of class members, but

also in the manner in which they incarcerated them. Haitians

were shipped to federal prisons and INS detention facilities

throughout the United States, which were located in “deso

late, remote, hostile, culturally diverse areas, containing a

paucity of available legal support and few, if any, Creole in

terpreters.” Louis I (J.A. 61). For example, INS officials

shipped Haitians, already represented in Florida by immigra

tion lawyers, from Florida to isolated desert areas such as Big

Springs, Texas or other isolated areas such as Raybrook, New

York, where immigration counsel were unavailable. INS had

never before treated any other race or nationality in this man

19

ner. R. at Vol. 42, p. 977; Vol. 38, pp. 161, 219 (testimony of

Charles Gordon). They separated husbands and wives and

parents and children, with “cruel results.” Louis III (J. A. 125

n.24); R. at Vol. 43, p. 1141; Vol. 44, pp. 1479-81. They applied

the detention policy to Haitian children, Louis III (J. A. 126-27

n.24), Px. 45 (R. at Vol. 45, pp. 1529-1531), Px. 46 (id, at

1561-1562), Px. 47 (id.); the elderly, Px. 47 (R. at Vol. 45, pp.

1561-1562), Px. 48 (id.); and those with medical problems. Px.

47 (id.), Px. 48 (id.). They held petitioners in substandard

facilities and subjected them to harsh conditions, R. at Vol. 41,

pp. 918-19, in sharp contrast to asylum seekers of other

nationalities.26 They physically abused some Haitians, R. at

Vol. 43, pp. 1224, 1251, and denied others appropriate care for

their medical conditions. Id. at 1258. They moved some Hai

tians to other facilities at night, without allowing them to take

their own clothes or belongings and without telling them where

they were going, leading some to be terrified that they were

being taken to Haiti. R. at Vol. 41, pp. 923-25. The district

28 In contrast to the Haitians, INS officials treated other similarly

situated groups in a humane fashion. Larry Mahoney, the Public

Affairs Officer for the Department of State in the Cuban/Haitian

Task Force from July 1980 to May 1981, noted the incredible dis

parity between Cuban and Haitian refugees detained at Krome. He

stated poignantly that Haitians “were not being treated the same as

the Cubans were” at Krome. R. at Vol. 43, p. 1143. He noted the

discriminatory treatment that Haitians previously received “still

exists at Krome.” Id. at 1140-41. Mahoney recounted that Krome,

commonly referred to as the “Caribbean Ellis Island,” provided

completely different services for Cubans and Haitians. Cubans were

able to resettle swiftly, and substantially more resources were put

toward their resettlement than that of the Haitians. Id. at 1148-50.

Moreover, while Haitians were always segregated by sex and had no

access to telephones, Cuban families were allowed to stay together

and a bank of telephones was put in “almost overnight” for the

Cubans. Id. at 1140-42. In addition, Cubans were provided re

creational facilities and trips outside of Krome. His request to pro

vide the same facilities to Haitians was denied. Id. at 1143.

2 0

court aptly concluded that the INS was playing a “human shell

game” with the Haitians. Louis I (J.A. 61).

The effect of such long-term and isolated detention was

devastating. Master’s Report and Recommendations at 12,14,

15, 16, 18 (R. 2112, 2114, 2115, 2116, 2118); Px. 62.1A (R. at

Vol. 39, pp. 335-36). The mental health of many of the Haitians

in detention deteriorated rapidly under these conditions. R. at

Vol. 39, pp. 370-371; Vol. 42, p. 1058. Indeed, one of the named

plaintiffs, Prophete Talleyrand, committed suicide while incar

cerated during the pendency of this litigation.

* * *

After carefully reviewing the evidence presented to the trial

court, the panel affirmed the district court’s conclusion that the

fifth amendment applied to excludable aliens, such as the Hai

tian petitioners, but reversed as “clearly erroneous” its factual

determination that petitioners had failed to carry their burden

of proving that government officials had intended to discrimi

nate in the incarceration of the Haitians. Jean I (J.A. 290).26

The panel remanded to the district court, ordering it to grant

broad injunctive relief prohibiting future invidious discrimina

tion against petitioners. Jean I (J.A. 291).

On August 16, 1983, the court of appeals ordered rehearing

en banc. On February 28,1984, the en banc court dismissed the

government’s appeal on the APA issue as moot and remanded

to the district court with instructions to vacate the injunctive

relief based on the APA violation. Jean II (J.A. 295). The en

banc court, which neither questioned nor rejected the panel’s

factual findings of invidious discrimination, nevertheless re

versed the panel’s holding that such discrimination could

violate the Constitution. The en banc court found that low-

level executive branch officials possess power in immigration

matters that is wholly unrestrained by the Constitution. It

held broadly that “excludable aliens such as the Haitian plain

26 The procedural history of the litigation prior to the panel’s deci

sion is summarized in the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari at 11 n.6.

2 1

tiffs have no constitutional rights with respect to their applica

tions for admission, asylum or parole.” Jean II (J.A. 341).

The en banc court suggested that a non-constitutional stand

ard to measure abuse of discretion could be employed by the

district court on remand, although it was unclear what issues

would be subject to this standard. It purports to be a standard

solely for reviewing alleged abuses of discretion by INS

enforcement officials. It is not, however, a standard for

reviewing the petitioners’ claims of discrimination.27 Four

members of the en banc court dissented from the court’s con

stitutional conclusions and its standard for reviewing abuses of

discretion by low-level agency officials. Jean II (J.A. 346-54).

On May 4, 1984, the court of appeals denied petitioners’

request for rehearing en banc, (J.A. 355), and for a stay pend

ing petition for a writ of certiorari, and entered its final judg

ment on rehearing en banc. (J.A. 356). On August 1, 1984,

petitioners timely filed a petition for writ of certiorari, which

this Court granted on December 3, 1984. 105 S.Ct. 563 (1984).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. No principle is more fundamental to this nation than that

invidious discrimination on the basis of race and national origin

by government officials has no acceptable place in our society.

The unprecedented holding of the court below—that the action

of INS enforcement officials in incarcerating petitioners solely

on the basis of their race and nationality is wholly beyond

27 The remand is directed only to those “class members presently in

detention.” Jean II (J.A. 330). The remand is not directed to, and

provides no relief for, the approximately 1700 class members who

have been released from detention. In the absence of reversal of the

en banc court’s decision by this Court, these petitioners would be

deprived of injunctive relief to prevent the recurrence of the pattern

of discrimination to which Haitians have been subjected for ten years

by INS officials. See Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971); Jean 1 (J.A. 290-91).

2 2

constitutional scrutiny—is fundamentally at odds with this

basic principle.

Neither legal precedent nor the facts of this case could

possibly justify the en banc court’s conclusions. This case does

not present a challenge to the power of Congress or the Execu

tive to admit or deny admission to aliens. It merely challenges

invidious discrimination in incarceration on the basis of race

and nationality against black Haitian refugees by INS enforce

ment officials.

Petitioners are persons “in any ordinary sense of that term ,”

Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 210 (1982), and, as such, are

entitled to challenge invidiously discriminatory incarceration

by INS enforcement officials. No government interest could

ever justify the total absence of constitutional scrutiny of such

discrimination.

2. The en banc court refused to subject respondents’ in

carceration of these black Haitian refugees to any con

stitutional review because, in its view, the discriminatory in

carceration was somehow related to the important govern

ment interest in controlling the entry of aliens. Not only is the

en banc court’s premise false both factually and legally, but its

constitutional conclusion would not follow in any event. On the

facts of this case, there was no danger that temporary release

on parole would lead to absconding or risk the nation’s

security—the traditional reasons supporting detention—and

INS officials conceded as much. See pp. 17-18, supra. Nor has

the temporary release of these petitioners pending determina

tion of their asylum claims been tantamount to their admission.

Parole determinations are entirely separate from admission

both factually and legally, and have no effect on immigration

status. Leng May Ma v. Barber, 357 U.S. at 190; 8 U.S.C.

§ 1182(d)(5)(A). As a result, parole does not interfere with the

power of Congress and the President to determine admission

questions and does not implicate the considerations of national

sovereignty and separation of powers that insulate admission

questions from close judicial scrutiny.

23

Petitioners do not contend that the Constitution requires the

adoption of any particular substantive policy in regard to

detention or parole, but only that whatever policy is adopted

must be applied in an evenhanded manner. Even assuming

arguendo a relationship between incarceration and admission,

discriminatory incarceration simply does not implicate any

legitimate concerns pertaining to the regulation of admission of

aliens into our country.

In any case, even the broad power concededly possessed by

Congress and the President to regulate admission into the

country, and in appropriate cases to make distinctions in

admission based on nationality, is not immune from con

stitutional scrutiny. Fiallo v. Bell, 430 U.S. 787, 793 n.5

(1977); The Chinese Exclusion Case, 130 U.S. 581, 604 (1889).

A fortiori where Congress and the President have chosen not

to draw such distinctions in the application of incarceration

pending a determination of admissibility, and where the Attor

ney General announced and intended an evenhanded policy,

discriminatory incarceration by subordinate enforcement offi

cials must receive constitutional scrutiny. Hampton v. Mow

Sun Wong, 426 U.S. 88 (1976).

3. Furthermore, the en banc court’s conclusion was based

on a fundamental misreading of Shaughnessy v. United States

ex rel. Mezei, 345 U.S. 206 (1953), which it believed “con

trolled” its decision. Mezei, however, is not controlling because

the Court’s holding rested upon the recognition that Mezei’s

incarceration, unlike the incarceration here, was to continue

his previously determined exclusion order. While Mezei’s re

lease would have “nullified” his exclusion order based on na

tional security and would have granted him a de facto admis

sion because no other country would accept him, neither of

those factors is present here. Moreover, this case does not, as

did Mezei, implicate procedural due process hearing rights,

but rather the equal protection of the law. Further, the prem

ises underlying the result in Mezei have been rejected by

subsequent constitutional developments.

24

ARGUMENT

I. BLACK HAITIAN REFUGEES ARE ENTITLED TO

EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAW

No principle is more fundamental to our nation’s history or

values or more firmly established in our law than that invidious

discrimination on the basis of race and national origin by

government officials has no acceptable place in our political and

social life.28 The Eleventh Circuit’s unprecedented holding—

that the actions of INS enforcement officials in incax derating

petitioners solely on the basis of their race and nationality is

wholly beyond constitutional scrutiny—is fundamentally at

war with this basic principle. Nothing in the facts of this case29

can justify the Eleventh Circuit’s conclusion, and no overriding

governmental interest is at stake that could possibly justify a

28 No value is more enshrined in our law or in our nation’s life than

the non-discrimination principle contained in the fifth and fourteenth

amendments. As Chief Justice Taft wrote for the Court in Truax v.

Corrigan, 257 U.S. 312, 332 (1921), “Our whole system of law is

predicated on the general, fundamental principle of equality of appli

cation of the law. ” Moreover, discrimination based on race and na

tional origin “strikes at the core concerns” of the fifth and fourteenth

amendments “and at fundamental values of our society and our legal

system.” Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545, 564 (1979). This Court

recently reemphasized the “important federal concerns arising from

the Constitution’s commitment to eradicating discrimination based

on race.” Palmore v. Sidoti, 104 S.Ct. 1879, 1881 (1984). Indeed, in

Lee v. Washington, 390 U.S. 333 (1968), this Court affirmed that

even a class of persons whose substantive liberty interests have

largely been extinguished by their valid convictions—sentenced

prisoners—may not be subjected to racial discrimination, a holding

reiterated just this past term. Hudson v. Palmer, 104 S.Ct. 3194,

3198 (1984) (“invidious racial discrimination is as intolerable within a

prison as outside”). The same core concerns apply equally to matters

concerning discrimination based upon national origin. Hernandez v.

Texas, 347 U.S. 475, 479 (1954); Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356

(1886).

29 See pp. 17-18, supra.

25

total absence of constitutional scrutiny. Indeed, even during

the most extreme emergency such as the perceived threat of

invasion and sabotage in the midst of a world war, this Court

subjected discriminatory incarceration to constitutional scru

tiny. Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944). Nor do

separation of powers concerns that would ordinarily command

judicial deference to the political branches of the federal

government apply where, as here, those political branches

have established a neutral policy that was then applied by

low-level agency officials “with an evil eye and an unequal hand

------” Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 373-74 (1886).

A. Excludable Aliens Are “Persons” Protected By The

Fifth Amendment

The equal protection guarantee of the fifth amendment pro

tects all “persons” without qualification. The fifth amendment

provides that “No person shall. . . be deprived of life, liberty,

or property, without due process of law . . . .” (Emphasis

added). This language could not be more explicit. Unlike the

limitation of citizenship under the privileges and immunities

clause of the fourteenth amendment, or the requirement that a

person be “within the jurisdiction” of a state under the equal

protection clause of the fourteenth amendment, the fifth

amendment permits neither a geographic nor a citizenship

limitation. It encompasses all persons wherever situated, in

cluding all aliens. Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 210 (1982)

(“Whatever his status under the immigration laws, an alien

surely is a ‘person’ in any ordinary sense of that term. Aliens,

even aliens whose presence in this country is unlawful, have

long been recognized as ‘persons’ guaranteed due process of

law by the Fifth and Fourteenth amendments.”); Mathews v.

Diaz, 426 U.S. 67, 77 (1975) (“Even [an alien] whose presence

in this country is unlawful, involuntary, or transitory is enti

tled to that constitutional protection.”); Wong Wing v. United

States, 163 U.S. 228, 238 (1896) (“all persons within the territo

ry of the United States are entitled to the protection guaran

26

teed by [the fifth amendment]”);30 Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118

U.S. 356, 369 (1886) (“These provisions are universal in their

application, to all persons within the territorial jurisdiction

. . . .”); Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. (4 Wall.) 281, 295 (1866)

(“The Constitution . . . covers with the shield of its protection

all classes of men, at all times, and under all circumstances.”).

The fifth amendment protects citizens and foreign nationals

without distinction, including friendly aliens, United States v.

Pink, 315 U.S. 203, 228 (1942), aliens outside the United

States, Russian Volunteer Fleet v. United States, 282 U.S.

481 (1931), citizens challenging actions by the United States

taken against them outside the country, Reid v. Covert, 354

U.S. 1 (1957); Balzac w. Porto Rico, 258 U.S. 298, 312-13 (1922)

(“The Constitution of the United States is in force . . . wher

ever and whenever the sovereign power of [the] government is

exerted”), aliens illegally within the country, Plyler v. Doe,

457 U.S. 202, 210 (1982); Mathews v. Diaz, 426 U.S. 67, 77

(1976), and excludable aliens stopped at the border or allowed

into the country but considered as though stopped at the

border.31 Thus, any person may invoke the fifth amendment to

30 In Wong Wing, this Court recognized that regardless of an alien’s

status in this country, federal courts may review challenges to his

detention under the fifth amendment. Although the aliens involved in

Wong Wing, under present terminology, would be deemed deport

able rather than excludable aliens, the decision in Wong Wing oc

curred before this Court’s decision in The Japanese Immigrant Case

(Kaoru Kamataya v. Fisher), 189 U.S. 86 (1903), adopting this

distinction. As a result, the broad language in Wong Wing defining

aliens as “persons” within the coverage of the fifth amendment

should not be limited to deportable aliens. Ironically, this principle

was recognized by even the en banc court. Jean II (J.A. 318 n.22).

31 Augustin v. Sava, 735 F.2d 32, 37 (2d Cir. 1984); Yin Sing Chun

v. Sava, 708 F.2d 869, 877 (2d Cir. 1983); Rodriguez-Femandez v.

Wilkinson, 654 F.2d 1382, 1387 (10th Cir. 1981); United States v.

Henry, 604 F.2d 908, 913 (5th Cir. 1979); see also United States v.

Demanett, 629 F.2d 862 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 450 U.S. 910 (1980)

(fourth amendment rights).

27

challenge action by the United States government, regardless

of his immigration status and regardless of whether he is or is

deemed to be inside the country, outside of it, or “at the

border.” Plainly, if an excludable alien (or even an alien

corporation) not within the territorial boundaries of the United

States may invoke the protections of the fifth amendment, as

may an unlawful alien within our boundaries, an excludable

alien who, although physically present within our boundaries is

deemed to be “at the border” for immigration purposes, is

protected by the Constitution. As persons “in any ordinary

sense of that term ,” Plylerv. Doe, 457 U.S. at 210, excludable

aliens such as the Haitian petitioners cannot be barred from

invoking the Constitution to challenge governmental actions

taken against them.

The en banc court’s failure to recognize or address the pri

mary question of the fifth amendment’s coverage led that court