Santiago v Victim Services Agency Brief Plaintiff Appellants

Public Court Documents

September 28, 1984

43 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Santiago v Victim Services Agency Brief Plaintiff Appellants, 1984. 6f5b739e-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5883b4bf-2f10-45a0-bb6d-d714cf6b3c10/santiago-v-victim-services-agency-brief-plaintiff-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

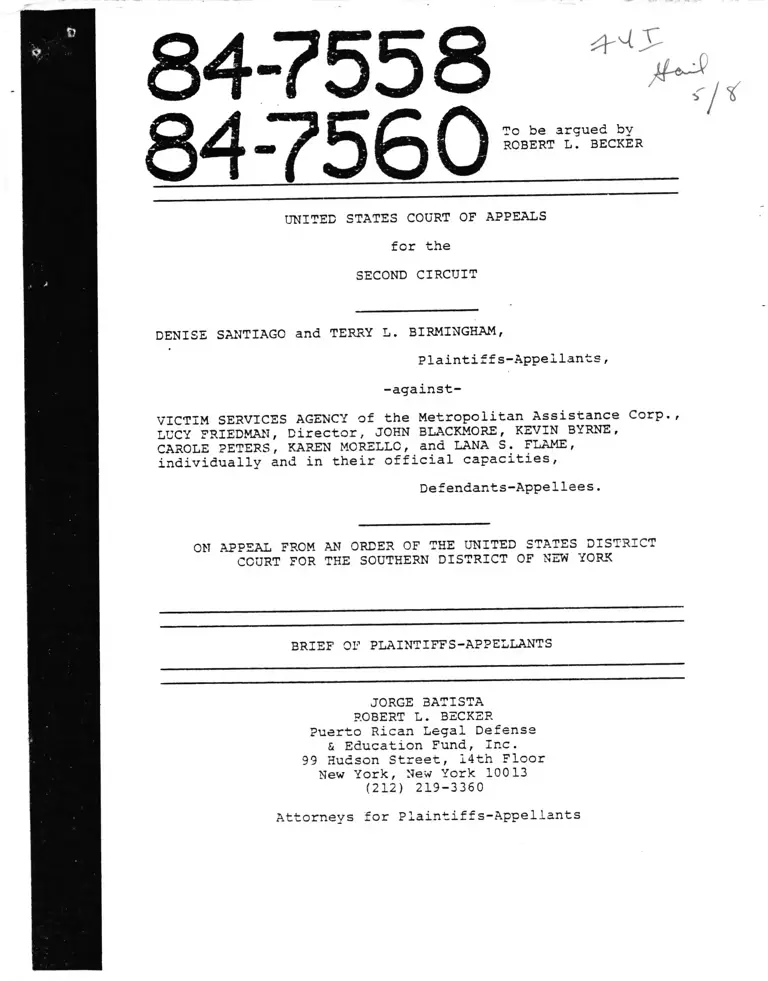

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

for the

SECOND CIRCUIT

DENISE SANTIAGO and TERRY L. BIRMINGHAM,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-against-

VICTIM SERVICES AGENCY of the Metropolitan Assistance Corp.,

LUCY FRIEDMAN, Director, JOHN BLACKMORE, KEVIN BYRNE,

CAROLE PETERS, KAREN MORELLC, and LANA S. FLAME,

individually and in their official capacities,

Defendants-Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM AN ORDER OF THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JORGE BATISTA

ROBERT L . BECKER

Puerto Rican Legal Defense

& Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, I4th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-3360

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF CASES...................................... i

QUESTIONS PRESENTED................................ iv

STATEMENT OF FACTS................................. 1

ARGUMENT

POINT I

PLAINTIFFS' VOLUNTARY DISMISSAL

OF THIS ACTION PURSUANT TO

RULE 41(a)(1)(i) OF THE FEDERAL

RULES OF CIVIL PROCEDURE PRECLU

DED THE DISTRICT COURT FROM SUB

SEQUENTLY ASSESSING ATTORNEYS'

FEES AGAINST THEM.................. 7

POINT II

THIS ACTION WAS NOT FRIVOLOUS

UNREASONABLE OR WITHOUT FOUNDA

TION AND ACCORDINGLY, DEFENDANTS

ARE NOT ENTITLED TO ATTORNEYS'

FEES FROM PLAINTIFFS............... 17

POINT III

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN

ASSESSING ATTORNEYS' FEES AGAINST

PLAINTIFFS' FORMER COUNSEL IN THE

ABSENCE OF A HEARING OR ANY

FINDING OF BAD FAITH............... 2 7

CONCLUSION.......................................... 37

TABLE OF CASES

American Cyanamid Co. v. McGhee, 317

F.2d 295 (5th Cir. 1963)..........

Barry v. Barchi, 443 U.S. 55 (1979).........

Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535 (1971)..........

Bernstein v. Birch Wathen School, 71 A.D. 2d

--------- 179 (1979), aff* 1d ,~51~N.Y. 2d 932

(1980)............................

Carter v. United States, 547 P.2d 528

(5th Cir. 1977)...................

Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434

U.S. 412 (1978)...................

Colucci v. New York Times Co., 533 F.Supp.

1011 (S.D.N.Y. 1982)..............

Corcoran v. Columbia Broadcasting Co., 121

F.2d 575 (D.C. Cir. 1941) .........

D.C. Electronics, Inc. v. Nartron Corp., 511

F .2d 294 (6th Cir. 1975) . . . .......

Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67 (1972)..........

Gear v. City of DesMoines, 25 FEP Cases 1400

(S.D. Iowa 1981).....................

Glass v. Pfeffer, 675 F.2d 252 (10th Cir.

1981).................................

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970)........

Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565 (1975).............

Harvey Aluminum v. American Cyanamid Co., 203

F .2d 105 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 345

U.S. 964 (1953)......................

Hughes v. Rowe, 449 U.S. 5 (1980)..............

Jackson v. City of Kileen, 654 F.2d 1181

(5th Cir. 1981)......................

Page

8

35

35

21

7, 11

18, 24-25

28-29

16

10, 11,

12, 13

35

20

33

34

35

12

18-19

21

l

Page

Knox v. Cornell University, 30 FEP Cases 433

(N.D.N.Y. 1982)......................

Littman v. Bache & Co., 252 F.2d 479

(2d Cir. 1958)........................

McDonnell Douqlas Corp. v. Green, 411

U.S. 792 (1973)......................

McFarland v. Gregory, 425 F.2d 608

(9th Cir. 1983)......................

Memphis Light, Gas & Water Div. v. Craft,

--- 436 U.S. 1 (1978)... .................

Merit Insurance Co. v. Leatherby Insurance Co.,

581 F .2d 137 (7th Cir. 1978 ..........

Miracle Mile Associates v. City of Rochester,

617 F .2d 18 (2d Cir. 1980)...........

Montgomery v. Yellow Freight Systems, Inc.,

---- “---- 671 F .2d 412 (10th Cir. 1982).......

20

13

19

34

35

9

30, 31, 32

21

Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. v.

U.S.E.P.A., 703 F .2d 700 (3rd Cir. 1983

Nemeroff v. Abelson, 620 F. 2d. 339

(2d. Cir. 1980).........................

Nemeroff v. Abelson, 704 F .2d 652 (2d Cir. 1983)

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc. ,

390 U.S. 400 (1.968)........ ...........

Newsday, Inc., v. Ross, 80 A.D. 2d 1 (2981).....

Pilot Freight Carriers Inc., v. International

Brotherhood of Teamsters, 506 F .2d

9T4 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 422 U.S.

1048 ....................................

PRC Harris, Inc., v. Boeing Co., 700 F.2d

894 (2d Cir. 1983).....................

Roadway Express, Inc., v. Piper, 447 U.S.

752 (1980)..............................

Ross v. Comsat, 34 FEP Cases 260 (D. Md. 1984) . . . .

Runyan v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976)............

17-18

29

30

17

20

12

30

15, 27, 29,

31, 33

20

29

li

Page

Ryan v. New York Telephone Co., - N.Y.2d -

(1984) (Slip opn. June 14 , 1984)........... 20

Smith v. District of Columbia, 29 FEP Cases

1129 (D.D.C. 1982).......................... 21

Stenseth v. Greater Fort Worth and Tarrant

County Community Action Agency,

673 F . 2d 842 (5th Cir. 1982)............... 22

Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine,

450 U.S. 248 (1981)......................... 19

Thorp v. Scarne, 599 F.2d 1169 (2d Cir.

1979)........................................ 8 , 9 , 10 ,

13

United States v. Blodget, 709 F.2d 608

(9th Cir. 1983)............................. 34

United States for Heydt v. Citizens State Bank,

688 F . 2d 444 (8th Cir. 1982)............... 16

United States Postal Service v. Aikens, - U.S. - ,

75 L. Ed. 2d 403 (1983)...................... 19

Weinberger v. Kendrick, 698 F.2d 61 (2d Cir. 1982)... 30

Williams v. Ezell, 531 F.2d 1261 (5th Cir.

1976)........................................ 8 , 10

Wooten v. New York Telephone Co., 485

F.Supp 748 (S.D.N.Y. 1980)................... 21

iii

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether plaintiffs' voluntary dismissal of this

action pursuant to Rule 41(a)(1)(i) of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure precluded the district court from subse

quently assessing attorneys' fees against them.

2. Whether this action was frivolous, unreasonable or

without foundation thereby entitling defendants to attor

neys' fees from plaintiffs.

3. Whether the district court erred in assessing

attorneys' fees against plaintiffs' former counsel in the

absence of a hearing or any finding of bad faith.

IV

STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND FACTS

Plaintiffs-appellants ("plaintiffs") commenced this

action on May 2, 1983 seeking to contest their terminations

from defendant-appellee ("defendant") Victim Services Agency

("VSA") in January, 1983. Plaintiffs, one of whom is

Hispanic and the other black, alleged in their complaint

that their terminations violated the First and Fourteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution, 42 U.S.C.

§§1981, 1983 and 1985, and also constituted conspiracy,

defamation, defamation per se and intentional infliction of

emotional distress which were asserted as pendant state

claims. (J.A.150-153)*.

Simultaneously with the filing of this action plain

tiffs moved by order to show cause for a preliminary injunc

tion restoring them to their former positions with VSA.

Argument of counsel was heard on May 6, 1983 and an

evidentiary hearing was held on June 3 and 8, 1983. (J.A.

10). At the conclusion of the June 8th hearing the district

court issued a decision from the bench denying plaintiffs'

motion for a preliminary injunction. Id. That ruling was

confirmed in a written opinion dated June 10, 1984. (J.A.

18-34) .

* References in this format are to pages of the Joint

Appendix.

Less than a week later, on June 16, 1983, plaintiffs

filed a notice of voluntary dismissal pursuant to Rule 41(a)

(1)(i) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. (J.A. 136).

Notwithstanding the dismissal, on August 3, 1983, almost

2 months later, defendants moved for attorneys' fees. (J.A.

103). Defendants' motion was granted in the amount of

$19,352.45 in a memorandum decision dated February 3, 1984.

(J.A. 9-17). Of that amount the lower court allocated

$50.00 against each of the plaintiffs and the balance,

$19,252.45, against plaintiffs' attorney, Gabe Kaimowitz.

On February 12, 1984 Mr. Kaimowitz filed a motion for

reconsideration and an evidentiary hearing pursuant to Rule

59(e) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure on his own

behalf. (J.A. 39). Three days later plaintiffs also filed

a Rule 59(e) motion. (J.A. 49). By memorandum

endorsement dated May 23, 1984, these motions were denied.

(J.A. 8).* Plaintiffs and Mr. Kaimowitz both filed notices

of appeal on June 22, 1984. (J.A. 5-7).

* This case was assigned to Judge Werker when it was

originally filed. In March and April, 1984, during the

pendency of the Rule 59(e) motions and Judge Werker's

illness, two orders in this matter were issued by Judge

Duffy granting defendants' request for adjournments of the

motions. (J.A. 61, 62). The May 23, 1984 decision denying

the Rule 59(e) motions was also issued by Judge Duffy, Judge

Werker having passed away on May 10, 1984. (J.A. 8). At no

time prior to the denial of these motions had plaintiffs

been informed of any reassignment of this action. Nor is

this reflected in the docket sheets. (J.A. 3-4). However,

on May 31, 1984, a week after Judge Duffy's decision, a

Notice of Reassignment was issued by the district court

clerk reassigning this action to Judge Broderick. (J.A.

82). This was entered on the docket sheet on June 1, 1984.

(J.A. 4).

2

At the time plaintiffs filed this action they had valid

reason to believe their federal constitutional and statutory

rights had been violated and their counsel acted in good

faith in initiating this lawsuit. Plaintiffs Birmingham and

Santiago were terminated from their positions as counselors

with the Bronx Family Court Office of VSA on January 17 and

19, 1983 respectively. (J.A. 147). They were discharged

because of "activities involving illegal substances". (J.A.

142). This was based on the alleged observations of one

individual, Patricia Johnson (J.A. 13, 199, 204), who, in an

affidavit sworn to the 10th day of March, 1983, at the

behest of VSA Executive Director Lucy Friedman, claimed to

have seen and told her supervisor of these activities a

significant amount of time before plaintiffs were terminat

ed. (J.A. 221).

Although these observations, if proved true, might well

have justified plaintiffs' dismissal, events which occurred

between the dates of plaintiffs' termination and the prelim

inary injunction hearing paint a very different picture.

Pursuant to agency policy, a Personnel Action Committee

("PAC") consisting of five agency employees was convened to

investigate and recommend to the Executive Director whether

plaintiffs' terminations should be upheld. Plaintiff

Santiago testified at .a hearing held by the PAC on March 7,

1983 and plaintiff Birmingham and Ms. Johnson testified at a

March 16, 1983 hearing. (J.A. 199). Both plaintiffs

3

testified that they did not use any drugs while employees of

VSA. (J .A . 50). Ms. Johnson, who testified under oath,

essentially recanted the statements in her earlier affida

vit. (J .A. 199). On the basis of all of the evidence

before it, the PAC unanimously recommended that both plain

tiffs be reinstated with backpay. (J.A. 198). Although

VSA's Executive Director, defendant Friedman, did not adopt

this recommendation, it represented, prior to the filing of

this lawsuit, the judgment of five VSA personnel who had

heard testimony, read affidavits and other documents, and

were in a position to evaluate issues of credibility, that

plaintiffs' terminations were unsubstantiated and

unjustified. Id.

Plaintiffs were also required to appear and testify at

hearings before administrative law judges in connection with

their applications for unemployment insurance following

their discharges. In both cases, VSA appeared by counsel

and opposed plaintiffs' requests for benefits. (J.A.

56, 57). In decisions dated May 24 and 26, 1983

administrative law judges credited plaintiffs' testimony

over the evidence adduced by defendants through their

counsel and concluded that plaintiffs had not lost their

jobs through misconduct. Id.

Thus, prior to the preliminary injunction hearing, two

independent fact-finding bodies or agencies credited plain

tiffs' testimony of non-drug use over the contrary position,

4

advanced both then and at the preliminary injunction

hearing, by defendants.

Under these circumstances it was entirely reasonable

for plaintiffs' counsel to question the stated reason for

his clients' termination. In examining this, two motives

were suggested. First, plaintiffs had been very active in

attempting to organize a union at VSA. (J.A. 146-147, 150).

Second, although plaintiffs are Hispanic and black respec

tively, everyone who participated in the decision to

terminate them was white. It is particularly significant

that although John Campbell, a black, was a supervisor of

plaintiffs one step removed, he was the only person in the

chain of command who was not consulted about the decision to

terminate plaintiffs. (J.A. 483). In a like manner, the

unanimous decision of the PAC, whose membership was

predominantly minority, was rejected by VSA's white

executive director even though she candidly admitted she did

not have any information concerning the plaintiffs that was

different than the information before the PAC. (J.A. 429,

430). Based on this pattern of by-passing and reversing any

input into the decisional process by minorities plaintiffs

instituted a lawsuit against VSA alleging, among other

things, that their right to be free from discrimination

under the Fourteenth Amendment and their right to contract

as guaranteed by 42 U.S.C. §1981 had been violated. (J.A.

150-151) .

5

As noted above, a preliminary injunction hearing was

held and, in a written opinion dated June 10, 1983, plain

tiffs' application to be reinstated was denied. Six days

later plaintiffs filed a notice of voluntary dismissal

pursuant to Rule 41(a)(1)(i) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure. Although not required to do so, on June 17, 1983

Judge Werker "So Ordered" the notice of voluntary dismissal.

(j .A. 80). Thus, this lawsuit lasted only a matter of about

six weeks from commencement to dismissal. After the

district court opinion plaintiffs made no further efforts to

litigate the claims ruled upon by the court.

Because, however, a subsequent Rule 59(e) motion

seeking reconsideration of the assessment of $19,352.45 in

attorneys' fees against plaintiffs and their former counsel

was unsuccessful, plaintiffs now appeal to this Court.

6

POINT I

PLAINTIFFS' VOLUNTARY

DISMISSAL OF THIS ACTION

PURSUANT TO RULE 41(a)(1)

(i) OF THE FEDERAL RULES

OF CIVIL PROCEDURE PRE

CLUDED THE DISTRICT COURT

FROM SUBSEQUENTLY ASSESSING

ATTORNEYS' FEES AGAINST

THEM.

Before addressing the question of whether the district

court utilized the correct legal standards in assessing

attorneys' fees against plaintiffs and their former attor

ney, it is necessary to determine whether the court had the

authority to even consider defendants' fee application.

Plaintiffs submit that once a voluntary notice of dismissal

was filed the lower court was without authority to award

defendants attorneys' fees.

On June 16, 1983 plaintiffs served and filed a notice

of voluntary dismissal pursuant to Rule 41(a)(1)(i) of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. (J.A. 136). It is

undisputed that up to that point defendants had neither

served an answer nor moved for summary judgment. Under

these circumstances plaintiffs had an absolute right to

dismiss their lawsuit. Carter v. United States, 547 F.2d

528, 529 (5th Cir. 1977). "The court had no power or

7

discretion to deny plaintiffs' right to dismiss or to attach

any condition or burden to that right"*. Williams v. Ezell,

531 F .2d 1261, 1264 (5th Cir. 1976). The lower court's

subsequent order awarding defendants' attorneys' fees, more

than seven months after the voluntary dismissal, was

therefore a nullity. Id; Derfner & Wolf, Court Awarded

Attorneys Fees, §9.02[3][a].

The rationale for these conclusions is obvious from a

reading’of Rule 41(a). Dismissal under subdivision

(a)(1)(i) merely requires the filing of a notice of dismiss

al prior to service of an answer or motion for summary

judgment. In contrast, dismissal at a later point, in the

absence of a stipulation signed by the parties, requires an

order of the court which may be granted "upon such terms and

conditions as the court deems proper." Rule 41(a)(2).

This Court has charcicterized the language of Rule

41(a)(1)(i) as "unambiguous". Thorp v. Scarne, 599 F.2d

1169, 1173 (2d Cir. 1979). Thus, it has quoted with ap

proval the following language from American Cyanamid Co. v.

McGhee, 317 F.2d 295, 297 (5th Cir. 1963):

* In their opposition to the Rule 59(e) motions below

defendants contended that plaintiffs Rule 41(a)(1)(i)

argument was inapplicable since the court did not impose any

burdens or conditions on the voluntary dismissal. This^

misses the point entirely. As the remainder of this point

demonstrates, once a notice of voluntary dismissal has been

filed, the case is closed for all purposes and the court is

powerless to grant any relief arising from that case.

8

So long as plaintiff has not been

served with his adversary's answer

or motion for summary judgment he

need do no more than file a notice

of dismissal with the Clerk._ That

document itself closes the file.

There is nothing defendant can do

to fan the ashes of that action

into life and the court has no role

to play. This is a matter of right

running to the plaintiff and may^

not be extinguished or circumscribed

by adversary or court. There is not

even a perfunctory order of court

closing the file. Its alpha and

omega was the doing of the plaintiff

alone.

Thorp v. Scarne, 599

F.2d at 1176.

The lower court's decision appears to suggest that its

reservation of the fee issue at the conclusion of the

preliminary injunction hearing overcomes the clear language

of the Rule. (J.A. 11). Assuming arguendo, a reservation of

the fee issue, it is still clear that this could not serve

to modify the effect of a voluntary dismissal under Rule

41(a)(1)(i). In Merit Insurance Co. v. Leatherbv Insurance

Co., 581 F .2d 137 (7th Cir. 1978), the district court

preliminarily granted a three month stay of the action and

ordered arbitration pursuant to the contract between the

parties. After a further extension of the stay the plain

tiff filed a notice of dismissal pursuant to Rule

41(a)(1)(i). A motion by the defendant to vacate the notice

of dismissal was denied by the district court and affirmed

by the court of appeals. The notice of dismissal therefore

had the effect of negating a prior order compelling arbi

tration. If a Rule 41(a)(1)(i) notice of dismissal can

9

negate a prior order it certainly can negate a reservation

of attorneys' fees which was never even reduced to an order.

In addition, as already noted, Williams v. Ezell, 531

F.2d at 1264, specifically stands for the proposition that

an order granting attorneys' fees subsequent to a Rule

41(a)(1)(i) voluntary dismissal is a nullity. Although

there was no attempted reservation of the fee issue in

Ezell, it is clear from that court's opinion that "Rule

41(a)(1) 'means precisely what it says'", that a prior

reservation can do nothing to alter the effect of a Rule

41(a)(1)(i) dismissal. Id. at 1263. The rule is clear and

unambiguous and contains no exceptions. D.C. Electronics,

Inc, v. Nartron Corp., 511 F.2d 294, 296 (6th Cir. 1975).

Once the notice of dismissal is filed the case is closed in

all respects. Thorp v. Scarne, 599 F.2d at 1176.

The facts in Thorp v. Scarne confirm the outcome

advanced by plaintiffs. There the court conducted a hearing

on plaintiffs' application for a temporary restraining order

on two dates five days apart. At the conclusion of the

hearing on the second date the court denied plaintiff's

application. At that time it also indicated that it would

grant a motion for summary judgment in favor of the defen

dants on the basis of their brief submitted on the motion

for a temporary restraining order and therefore "directed

the defendants to file a formal motion." Id. at 1172, ftnt.

4. (Emphasis added.) The following day, before defendants

had filed their motion for summary judgment, plaintiff filed

10

a notice of voluntary dismissal under Rule 41(a)(1)(i).

Even though defendants filed their motion for summary

judgment a few hours later (id. at 1171) (no answer had

ever been filed), this Court ruled that plaintiff's notice

of dismissal had to be honored.

In the case at bar the court's allowance to defendants

to apply for attorneys' fees is, at best, the equivalent of

the Thorp court's direction to defendants to file a motion

for summary judgment. If the latter could not survive in

the face of an intervening notice of dismissal, there is no

basis to suggest that the allowance to file for attorneys'

fees survives a notice of dismissal. This is all the more

true here since there was no court directive but merely an

acknowledgment that defendants could do that which they were

free to do in any event. (J.A. 618).

If the result of a notice of dismissal seems harsh, it

was easily within the power of defendants to avoid its

adverse impact. "Defendants who desire to prevent plain

tiffs from invoking their unfettered right to dismiss

actions under Rule 41(a)(1) may do so by taking the simple

step of filing an answer." Carter v. United States, 547

F 2d at 259. It is simply defendants' own lack of diligence

in serving and filing an answer or motion for summary

judgment that prevents them from seeking to obtain attor

neys' fees at this juncture. See, D.C. Electronics, Inc. v.

Nartron Corp., 511 F .2d at 298.

11

Defendants may attempt to argue, primarily on the

authority of Harvey Aluminum v. American Cyanamid Co., 203

F.2d 105 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 345 U.S. 964 (1953), that

because the district court reached the "merits of the

controversy", plaintiffs were foreclosed from obtaining the

benefits of a voluntary notice of dismissal. This, however,

ignores the clear and unambiguous language of Rule

41(a)(1)(i) and the fact that Harvey has not been followed

in other jurisdictions or even by this Court in subsequent

decisions.

Rule 41(a)(1)(i) is neither vague nor ambiguous.

"[T]he drafters employed precise language" to define when a

voluntary notice of dismissal could be employed. D .C

Electronics v. Nartron Corp., 511 F.2d at 297. Rule 41

(a)(1)(i) "establish[es] a bright-line test marking the

termination of a plaintiff's otherwise unfettered right

voluntarily and unilaterally to dismiss an action." Thorp

v. Scarne, 599 F.2d at 1175. Since the Rule creates no

exception for cases which may have reached the merits of

the controversy" notwithstanding no answer or summary

judgment motion having been filed, it would be improper for

a court to impose such an exception. In fact, application

of the Harvey rule would result in a "flat amendment of Rule

41(a)(1) to preclude dismissal by notice in any case where

preliminary injunctive relief is sought." Pilot Freight

Carriers Inc. v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters, 506

12

F .2d 914, 916 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 422 U.S. 1048

(1975) .

The legislative history of Rule 41(a) also confirms

this result. In 1946 Rule 41(a)(1)(i) was amended to

provide that service of a motion for summary judgment would

have the same effect in preventing absolute dismissal as was

originally created with the service of an answer. Rule 41,

Notes of Advisory Committee on 1946 Amendments. Since that

time Rule 41 has been amended on three more occasions but

"it has not been broadened to include other motions or

pleadings which would bar a dismissal by notice. D •̂ »

Electronics, Inc, v. Nartron Corp., 511 F.2d at 296. It is

clear therefore that even after a preliminary injunction

hearing where the merits may have been considered a volun

tary notice of dismissal is effective in the absence of an

intervening answer or motion for summary judgment.

All of this is consistent with the views expressed by

this Circuit in decisions subsequent to the Harvey opinion.

Just three years after Harvey in Littman v. Bache & Co., 25.

F .2d 479 (2d Cir. 1958), this Court refused to follow the

reasoning of its earlier decision by distinguishing the

facts of that case. More recently, in Thorp v. Scarne, 599

F .2d at 1175 this Court wrote:

Harvev Aluminum has not been well

received. Although its rationale

is occasionally reiterated in dictum,

subsequent cases have almost uniformly

either distinguished Harvev Aluminum,

limiting the case to its particular

13

factual setting, or forthrightly

rejected it as poorly reasoned.

This Court then went on to specifically criticize the

reasoning of Harvey. It noted that Harvey does damage to

the "bright-line test" of Rule 41(a)(1)(i) and would result

in a blanket amendment to the Rule precluding its applica

tion in instances where a preliminary injunction has been

sought even though never proposed on any of the four oc

casions when Rule 41 has been amended. Id. at 1175-1176.

Finally, the court observed that a defendant can be protect

ed against the possibly harsh application of Rule

41(a)(1)(i) by simply filing an answer or motion for summary

judgment. Id.

The linchpin of the district court's reasoning for

overcoming the effect of Rule 41(a) (1) (i) appears to be the

court's power to reserve the issue of attorneys' fees

pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1988. (J.A. 11). As already

discussed, there is no authority, at least in the context of

Rule 41(a) (1) (i), to support .this. The authority is all to

the contrary. Beyond this, there was no reservation of the

fee issue in the traditional sense. Reserving attorneys

fees is typically done in the context of dismissing the

underlying action. It preserves a party's right to apply

for fees notwithstanding the dismissal. At the time defen

dants requested an opportunity to move for attorneys' fees

there had been no dismissal of this action and none was

discussed. There was no need for a reservation of the

issue. Considered in the context of the discussion which

14

took place, the court simply confirmed defendant's right to

do, at that time, what they could do without court approval.

The fact that there was no reservation of attorneys'

fees is made all the more apparent by the lower court's

actions with respect to the notice of voluntary dismissal.

The original notice of voluntary dismissal was "So Ordered"

by Judge Werker on June 17, 1983. (J.A. 80). Judge Werker

also noted in the body of the notice that defendants had not

filed an answer and changed the caption of the document from

"Notice of Voluntary Dismissal" to "Notice & Order of

Voluntary Dismissal". Id. Had the lower court intended to

reserve the issue of attorneys' fees it would have been

reasonable to expect some indication of that at this point.

Instead, its actions were completely contrary to any

intention to reserve the fee issue.

Moreover, even if there had been a reservation of the

fee issue pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1988 as the lower court

suggests, that could not have served as a basis for later

assessing fees against plaintiffs' former attorney. It is

undisputed that Section 1988 makes no mention of attorney

liability for fees and costs. Roadway Express v. Piper, 447

U.S. 752, 761 (1980). Therefore, reservation of the fee

issue pursuant to Section 1988 could in no way serve as the

predicate for later assessing fees against plaintiffs

counsel. This is all the more so where a voluntary notice

of dismissal has been filed in the interim.

15

Finally, the district court's citation to Natural

Resources Defense Council, Inc., v. U.S.E.P.A^, 703 F.2d 700

(3rd Cir. 1983) and United States for Heydt v. Citizens

State Bank, 688 F.2d 444 (8th Cir. 1982), does not lend any

support for the position that a voluntary dismissal under

Rule 41(a)(1)(i) is ineffective with respect to a subsequent

application for attorneys' fees. Neither case involved a

dismissal pursuant to Rule 41(a)(1)(i)- In fact, there was

no dismissal at all in Natural Resources Defense Council and

the dismissal in United States for Heydt was pursuant to a

stipulation of settlement. The reference to voluntary

dismissal in both cases was in the context of determining

prevailing party status and, even at that, was purely dicta.

Both cases cited Corcoran v. Columbia Broadcasting Co.,

121 F.2d 575 (D.C. Cir. 1941), which is no more applicable

to this case than those cases. Corcoran involved a volun

tary dismissal pursuant to Rule 41(a)(2). There it is

understandable that prevailing party status might be con

sidered because, as already noted, a district court can

condition dismissal on various sanctions including the

payment of attorneys' fees. Additionally, in Corcoran the

court actually ignored Rule 41 and looked to the underlying

substantive statute as the basis for the award of fees.

Derfner & V7olf, Court Awarded Attorney Fees, 59.02 [3] [a].

Once a plaintiff has properly invoked Rule 41(a)(1)(i),

the district court is powerless to award attorneys' fees.

16

POINT II

THIS ACTION WAS NOT FRIVOLOUS,

UNREASONABLE OR WITHOUT FOUN

DATION AND ACCORDINGLY, DEFENDANTS

ARE NOT ENTITLED TO ATTORNEYS'

FEES FROM PLAINTIFFS.

Even if this Court were to conclude that plaintiffs

voluntary dismissal pursuant to Rule 41(a)(1)(i) did not

prevent the district court from reaching the merits of

defendants' application for attorneys' fees, it is clear

that because this action was not frivolous, unreasonable or

without foundation, defendants were not entitled to an award

of fees from plaintiffs.

A prevailing plaintiff in a civil rights action "should

ordinarily recover an attorney's fee unless special circum

stances would render such an award unjust." Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968).

The purpose of counsel fee provisions for plaintiffs is not

punitive, but rather, to encourage private enforcement of

broad governmental policies by removing financial impedi

ments :

When a Dlaintiff brings an action

under [Title II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964] he cannot recover damages.

If he obtains an injunction, he does so

not for himself alone but also as a

"private attorney general," vindicating

a policy that Congress considered of the

highest priority. If successful plain-

17

tiffs were routinely forced to bear^

their own attorneys' fees, few aggrieved

parties would be in a position to advance

the public interest by invoking the in

junctive powers of the Federal courts.

Congress therefore enacted the provision

for counsel fees— *** to encourage

individuals injured by racial discrimi

tion to seek judicial relief under Title II

Tr!_ Ftnt, nmitted.

The rule for a prevailing defendant, however, is quite

different. There a district court is empowered to award

attorneys' fees only "upon a finding that the plaintiff's

action was frivolous, unreasonable, or without founda

tion..." Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412

421 (1978).

Although the words "frivolous" and "unreasonable" are

somewhat abstract, they have been given greater specificity

and meaning. In Christiansburg the Court concluded from

limited legislative history that the purpose in granting

fees to defendants was "to protect [them] from burdensome

litigation having no legal or factual basis." Id. at 420.

At another point it defined "meritless" as "groundless or

without foundation." Id. at 421.

in Hughes v. Rowe, 449 U.S. 5 (1980), the Court re-

peated this admonition. "The plaintiff's action must be

meritless in the sense that it is groundless or without

foundation." Id. at 14. The Court added, however, that

[a] negations that, upon careful

examination, prove legally insuf-

18

ficient to require a trial are

not, for that reason alone, ground

less" or "without foundation" as

required by Christiansburg.

Id. at 15-16

In essence the court must be persuaded that plaintiff

can produce no evidence whatsoever to support his claim or

that plaintiff has no colorable legal theory. Derfner &

Wolf, Court Awarded Attorney Fees, «[10,04 [3] [a] . This

simply is not the case here.

Plaintiffs' theory of discrimination, for example,

accorded with accepted practice. If they could demonstrate

that the only legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason advanced

by the employer for their terminations was untrue and merely

a pretext, it was more likely than not that they had been

terminated for impermissible (i.e. discriminatory) reasons.

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 805 (1973);

Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248,

256 (1981). It is also important to keep m mind that a

plaintiff is not required to submit direct evidence of

discriminatory intent in order to prevail. United States

Postal Service v. Aitkins, - U.S.-, 75 L.Ed.2d 403, 411

(1983). Viewed from this perspective, the facts clearly

support a colorable theory of discrimination.

Both plaintiffs are minorities. All of those who

recommended or approved of their terminations were white.

There have never been any allegations that plaintiffs did

not perform their jobs adequately. The purported reason for

19

termination advanced by defendants was based on the state

ment of one person who had recanted her accusations.

Plaintiffs testified on two separate occasions where they

denied any involvement in drugs - the proferred basis for

their terminations. On both occasions their testimony was

given credence and their reinstatement recommended and their

entitlement to unemployment insurance benefits upheld,

respectively. . Thus, up to June, 1983, two independent

fact-finding bodies or individuals credited plaintiffs'

testimony rather than testimony and evidence submitted by

the employer. While plaintiffs might not have prevailed

ultimately, these facts more than support a viable theory of

discrimination. Under these circumstances it can

hardly be concluded that prior to the preliminary injunction

hearing plaintiffs' action was frivolous.*

In analyzing plaintiffs' prima facie case on the

discrimination claim the district court found fault with the

fact that plaintiffs were not replaced by non-minorities.

(J.A. 26). Yet proof of replacement efforts generally, and

proof of replacement by a non-minority in particular,

*The findings of non-drug use by the two Administrative

Law Judges in the unemployment insurance hearing are partic

ularly significant. Where a party has had a full and fair

opportunity to litigate issues in an unemployment insurance

appeal proceeding, it is collaterally estopped from relit-

igating those issues in a subsequent judicial proceeding,

including actions alleging discrimination. Knox v. Cornell

University, 30 FEP Cases 433 , 435-436 (N.D.N.Y.^1982)_, Gear

v. City of DesMoines, 25 FEP Cases 1400, 1405 (S.D. Iowa

1981); Ross v. Comsat, 34 FEP Cases 260, 263-264 (D^ Md.

1984). See also, Ryan v. New York Telephone Co., -N.Y.-

(1984) (Slip opn. June 14 , 1984); Newsday,— Inc. v. Ross, 80

20

have not been held to be essential factors in establishing a

claim of discriminatory discharge. Smith v. District of

Columbia, 29 FEP Cases 1129 (D.D.C. 1982); Wooten v. New

York Telephone Co., 485 F.Supp. 748 (S.D.N.Y. 1980); Jackson

v. City of Killeen, 654 F.2d 1181, 1184 n.3 (5th Cir. 1981).

Plaintiffs' case was no less substantial than other

cases where the courts refused to award attorneys' fees to

defendants. In Montgomery v. Yellow Freight System, Inc.,

671 F .2d 412 (10th Cir. 1982), a mechanic sued under Title

VII to contest his discharge for sleeping in a truck during

his shift while other vehicles were awaiting servicing. The

plaintiff appears to have conceded the truth of this but

claimed that on another occasion three mechanics (including

himself) were found asleep but not fired. It was also

claimed that on one occasion a supervisor not involved in

the decision to terminate plaintiff made a disparaging

remark about his race. The court concluded that plaintiff

failed to carry his burden of demonstrating that the reason

for his termination was pretextual and that [t]here was

ample evidence that appellant was fired for a legitimate

reason, sleeping on the job." Id. at 413. Nevertheless,

the court refused to uphold the employer's claim for attor-

Footnote continued from page 20

A.D. 2d 1 (1981); Bernstein v. Birch Wathen School, 71 A.D.

2d 179 (1979, aff'd, 51 N.Y. 2d 932 (1980). Since the

non-discriminatory reason advanced in this action for

plaintiffs' terminations was the same as that used to

support the denial of unemployment insurance benefits,

defendants would have been estopped at a trial of this

action from relitigating the facts of plaintiffs' termina

tions .

21

neys' fees because even on the record of that case [t]here

was some evidence of disparate treatment...' a"*- 414.

In stenseth v. Greater Fort Worth and Tarrant County

Community Action Agency, 673 F.2d 842 (5th Cir. 1982) , a

counselor and administrator of a CETA program brought suit

under 42 U.S.C. §1983 alleging that the procedures utilized

in his termination violated his civil rights. Plaintiff was

terminated for his inadequacies as an administrator, evi

dence of which the court found to be "strong and clear

(id. at 847) and which the plaintiff virtually conceded as

being true. The court also found that plaintiff's termina

tion hearing "without question met constitutional require

ments of due process and fairness." Id. Notwithstanding

the obvious weaknesses in the case, the district court's

assessment of over $16,000 in fees against the plaintiff was

reversed in part on the basis that "it cannot be

characterized as frivolous for plaintiff to rely upon the

slender reed that the regulations [for termination] actually

applied more broadly than they seemed, in terms, to apply.

Id. at 849. (Emphasis added).

Unlike those situations, in the present case plaintiffs

never conceded the truth of the reason advanced for their

terminations. The only evidentiary basis for concluding

that plaintiffs had been involved in drugs was highly

questionable at best and, as noted above, was recognized in

two separate fact-finding proceedings.

22

This case is also distinguished by a pattern of

by-passing or disregarding the input of minorities in the

decision making process. John Campbell, the only black in

the chain of command was virtually ignored in deciding

whether to terminate plaintiffs. The absence of any expla

nation for this is particularly difficult to understand in

light of the position of his supervisor, Kevin Byrne, who

testified that he wanted Campbell to assume complete respon

sibility for the Family Court unit. (J.A. 482). The

rejection of the PAC, four of whose members were minorities

(J.A. 148), is also perplexing. The critical issue in this

case was a question of fact. Only the members of the PAC

heard, and were thus in a position to evaluate the credibil

ity of, all of the relevant witnesses. Ms. Friedman admit

ted she did not have possession of any information not

available to the PAC (J.A. 429, 430) and, because she had

not interviewed everyone, actually had less information

available to her.

This consistent by—passing or rejection of input by

minorities at each stage of the decisional process, when

coupled with the race of the plaintiffs and those who

approved their termination and the fact that the purported

reason for their termination had been adjudged unjustified

and unsubstantiated on at least two occasions, gave plain

tiffs and their former counsel a more than legitimate basis

for initiating this action.

23

The reasonableness with which plaintiffs litigated this

action is also evidenced by events prior to its initiation

and subsequent to the decision on the preliminary injunction

motion. After the Personnel Action Committee hearing

plaintiffs, through counsel, sought to negotiate a settle

ment of their claims. Only after it became apparent that a

settlement could not be reached was this action commenced.

(J .A. 41). Additionally, less than a week after the

district court's written opinion denying plaintiffs' motion

for a preliminary injunction they voluntarily discontinued

this action pursuant to Rule 41(a)(1)(i). This action

lasted only a total of six weeks and only two weeks from the

first evidentiary hearing. Under no circumstances can it be

claimed that plaintiffs persisted in vexatiously litigating

a case after they knew, or should have known, that it was

meritless.

In Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412,

421-422 (1978), the Supreme Court admonished district courts

to

resist the understandable temptation

to engage in post hoc reasoning by

concluding that because a plaintiff

did not prevail, his action must have

been unreasonable or without foundation.

This kind of hindsight logic could

discourage all but the most airtight

claims, for seldom can a prospective

plaintiff be sure of ultimate success.

No matter how honest one's belief that

he has been the victim of discrimination,

no matter how meritorious one’s claim may

appear at the outset, the course of litiga

tion is rarely predictable. Decisive

24

facts may not emerge until discovery or

trial. The law may change or clarify in

the midst of litigation. Even when the

law or the facts appear questionable or

unfavorable at the outset, a party may

have an entirely reasonable ground for

bringing suit.

Measured against these considerations, it simply cannot

be concluded that plaintiffs were without any factual or

legal basis for bringing this lawsuit or, having filed the

action, for litigating it until the notice of voluntary

dismissal was filed.

In fact, the district court's finding that this lawsuit

was frivolous is explainable only by its failure to heed the

principle that courts should not engage in post hoc reason

ing. This is evident from its treatment of the Section 1983

claim requiring proof that defendants have acted under color

of state law. It is common knowledge that VSA is a publicly

funded agency that provides services in the criminal justice

system on an intimate basis with various state and local

agencies. For example, in the case of battered women, VSA,

through conducting interviews and taking pictures of

victims, almost acts as the invesitgatory arm of the

District Attorney's Office. (J.A. 399-401). What only

became known to plaintiffs after the preliminary injunction

hearing at which Lucy Friedman, VSA's executive director,

testified, was that much of VSA's public funding comes from

the federal government, that no government entities

participate in the selection of VSA's board of directors or

the development of personnel policies and that defendant

25

Friedman did not consult with any federal, state or city

officials in connection with her decisions concerning the

two plaintiffs. (J.A. 403, 437, 439).* Viewed in retro

spect, as the district court did, plaintiffs' claim of state

action may indeed appear weak. Viewed from the perspective

of the commencement of this action, the assertion of claims

based on state action was not unreasonable.

This was not a case where discovery was possible either

before the action was filed or prior to the preliminary

injunction hearing. To the extent that the preliminary

injunction hearing revealed weaknesses in plaintiffs' case,

they discontinued the action almost immediately thereafter.

Under all of these circumstances it is impossible to con

clude that plaintiffs vexatiously sought to litigate this

action after they knew or should have known that it was

meritless.

* None of these facts were contained in Ms. Friedman's

lengthy affidavit submitted in opposition to the motion for

a preliminary injunction. (J.A. 250-270).

26

POINT III

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN

ASSESSING ATTORNEYS' FEES

AGAINST PLAINTIFFS' FORMER

COUNSEL IN THE ABSENCE OF A

HEARING OR ANY FINDING OF

BAD .FAITH.

Except for $100, the district court assessed the entire

fee sought by defendants against plaintiffs' former counsel.

The Court determined that it was authorized to assess legal

fees against an attorney on the basis of 28 U.S.C. §1927,

Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and on the

basis of its inherent equitable powers as explained in

Roadway Express, Inc, v. Piper. 447 U.S. 752 (1980).

Preliminarily, Rule 11 provides that an attorney s

signature to a pleading, motion or other paper constitutes,

among other things, a certificate that after reasonable

inquiry he believes the pleading, motion or other paper to

be "grounded in fact and warranted by existing law". It

therefore follows that attorneys' fees can only be assessed

under this provision upon a determination that, at the time

of signing the pleading, motion or other paper the attorney

knew or should have known that the action was unsupportable.

The district court made no such finding and there is nothing

in the record that would permit such a finding.

27

Section 1927 also contains limitations apparently not

considered by the court below. The statute only permits

fees against an attorney "who multiplies the proceedings ...

unreasonably and vexatiously..." Additionally, the amount

is limited to "the excess costs, expenses and attorneys'

fees reasonably incurred because of such conduct." Here too

the lower court made no findings consistent with these

standards and the record is entirely devoid of any basis for

finding that plaintiffs' attorney unreasonably and

vexatiously multiplied the proceedings.

Apart from these considerations, all of the cited bases

for assessing fees against counsel require a finding that

the lawsuit was brought or litigated in bad faith. In

Colucci v. New York Times Co., 533 F.Supp. 1011, 1013-1014

(S.D.N.Y. 1982), Judge Weinfeld discussed the requirements

of Section 1927 as follows:

The sanctions authorized under section

1927 are not to be lightly imposed; nor

are they to be triggered because a law

yer vigorously and zealously pressed

his client's interests. The power to

assess the fees against an attorney

should be exercised with restraint

lest the prospect thereof chill the

ardor of proper and forceful advocacy

on behalf of a client. To justify the

imposition of excess costs of liti

gation upon an attorney his conduct must

be of an egregious nature, stamped by

bad faith that is violative of recog

nized standards in the conduct of liti

gation. The section is directed against

attorneys who willfully abuse judicial

processes. (Emphasis added, ftnt. omit

ted. )

28

Judge Weinfeld further observed at 1014:

If the mere failure of a party to sus-

tain the allegations of his complaint is

sufficient to establish that an attopney

had thereby multiplied the proceeding

"unreasonably and vexatiously, then in

almost every instance of failure to

submit proof to sustain a claim, section

1927 would automatically come into play.

In any event, there is not the slightest

basis for charging that the attorneys'

failure to present the proof required to

sustain the retaliation charge was moti

vated by bad faith or in any way was

violative of standard practice.

The standard for assessing fees under Rule 11 is also •

bad faith. Nemeroff v. Abelson, 620 F.2d 339, 350 (2d. Cir.

1980). Likewise, assessment of fees under the court's

inherent equitable powers can only be done where the attor

ney's conduct amounts to bad faith and where a specific

finding to that effect has been made. Roadway Express, Inc,

v. Piper, 447 U.S. at 767.

Judge Weinfeld's admonition that a party's inability to

meet his burden of proof is not a basis for automatically

concluding that a case was litigated in bad faith has been

acknowledged by the Supreme Court. In Runyon v. McCrary,

427 U.S. 160, 183 (1976), the Court wrote:

Simply because the facts were found

against the schools does not by itself

prove that threshold of irresponsible

conduct for which a penalty assessment

would be justified. Whenever the facts

in a case are disputed, a court perforce

must decide that one party's version is

inaccurate. Yet it would be unreasonable

to conclude ipso facto that the party had

acted in bad faith.

29

This Court too has recognized that even if an action is

without merit it does not follow that it was brought in bad

faith. Miracle Mile Associates v. City of Rochester, 617

F .2d 18, 21 {2d Cir. 1980)? PRC Harris, Inc, v. Boeing .Co.,

700 F .2d 894, 898 (2d Cir. 1983). In Weinberger v.

Kendrick, 698 F.2d 61, 80 (2d Cir. 1982), this Court ex

plained in detail the applicable standard and its rationale.

We have required, however, a high degree

of specificity in factual findings of

lower courts when attorneys' fees are

awarded on the basis of bad faith, ....

and that there be "clear evidence" that

the challenged actions "are entirely with

out color and [are taken] for reasons of

harassment or delay for other improper

purposes", ... These requirements are

a sound means of ensuring that persons

with colorable claims will not be deterred

from pursuing their rights by the fear of

an award of attorneys' fees against

them,...

The injunction that assessment of fees on the basis of bad

faith must be utilized with caution and applied only in

compelling or unusual circumstances so as not to deter

plaintiffs from suing to enforce their rights was reiterated

again in Nemeroff v. Abelson, 704 F.2d 652, 654 (2d Cir.

1983) .

Measured against these standards, the lower court

opinion was deficient in several respects. First, it is not

at all clear that the district court even recognized that

bad faith was the appropriate standard for assessing a fees

against the attorney. The term "bad faith" appears only

once in the entire opinion and then in connection with a

30

quote from Roadway Express, Inc, v. Pi£er, 447 U.S. 752

(1980). (J.A. 14). Second, even it it was aware of the bad

faith standard, it is clear that the lower court did not

utilize it. It justified the assessment against Mr.

Kaimowitz because he was "better able to afford [it]" (J.A.

13) and because he had to assume responsibility for the

defense of a "meritless" lawsuit. (J.A. 16). Counsel's

better ability to bear the costs of a fee assessment is

nowhere expressed as the proper standard and is inconsistent

with the particular facts in this case. (J.A. 43).

Similarly, while a meritless lawsuit may trigger an assess

ment of fees against a plaintiff, as all of the cases

demonstrate, only a specific finding of bad faith provides a

basis for charging an attorney with his adversary's legal

fees. The lower court decision is devoid of any such

findings. Finally, an examination of the entire record

discloses no evidence of bad faith. While people may differ

as to the wisdom of having initiated this action, there is

simply nothing in the record which supports a conclusion

that it was brought to harass defendants or for some other

impermissible motive.

A comparison of the facts of Miracle Mile Associates v.

C.itv of Rochester, 617 F.2d at 18 with this case makes it

clear that there is no basis for a finding of bad faith

here. In Miracle Mile plaintiffs were developers of a

regional shopping center in a suburb of Rochester. They

sued in the Western District of New York the City of

31

Rochester and various city officials who controlled vacant

land that was seen as being in competition with their plans

for constructing a suburban shopping center. Plaintiffs

specific complaint was that by petitioning the state to

begin an environmental quality review of plaintiffs plans

defendants, as competitors, acted in restraint of trade in

violation of the Sherman Act and the Donnelly Act. Plain

tiffs, using the same counsel, had previously brought a

similar lawsuit in the Northern District of New York to

challenge efforts to block construction of shopping malls in

that area. In that case, the district court, in an opinion

affirmed by this Court, with certiorari denied by the

Supreme Court, dismissed the complaint holding that the

municipality's conduct was protected under the

Noerr-Pennington doctrine. Notwithstanding this, this Court

held that the filing of the second suit, which was found to

be considerably weaker than the first and in fact without

merit, by the same counsel who were characterized as no

strangers to the legal principles which are applicable here"

(Miracle Mile Associates v. City of Rochester, 617 F.2d at

20), did not amount to bad faith.

Certainly here where, on the basis of the PAC recommen

dation and the findings of the administrative law judges,

plaintiffs and counsel had legitimate grounds for believing

that the proffered reason for plaintiffs' termination could

not be supported, their initiation of this lawsuit cannot be

32

characterized as having been in bad faith.

In addition to not recognizing or applying the correct

legal standard in this case, the district court’s decision

is fatally flawed in one other significant respect. The

court failed to provide plaintiff's former counsel with a

hearing at which he would have had the opportunity to rebut

any allegation of bad faith by explaining his motivation in

commencing the action. This is all the more true given the

size of the assessment against counsel.

When the district court determines to assess fees

against an attorney, that changes significantly the focus of

the litigation. Up to that point issues of relief and

liability are matters between the parties who have subjected

themselves to the jurisdiction of the court for those

purposes. Undoubtedly because of this and the consequent

due process implications, the Supreme Court has cautioned

that fees against an attorney "should not be assessed ...

without fair notice and an opportunity for a hearing on the

record." Roadway Express, Inc, v. Piper, 447 U.S. at 767 .

In Glass v. Pfeffer, 657 F.2d 252, 258 (10th Cir. 1981), it

was specifically held that assessment of fees against an

attorney must be reversed in the absence of notice and an

opportunity for a hearing.

In a case in which the size of the penalty under Rule

37 was less than half of the amount assessed here this Court

was constrained to rule that the size alone warranted an

33

opportunity for a hearing and the right to cross-examine.

McFarland v. Gregory, 425 F.2d 443, 450 (2d Cir. 1970). In

United States v. Blodgett, 709 F.2d 608, 610 (9th Cir.

1983) , the court wrote that "...the mere fact that an appeal

is frivolous does not of itself establish bad faith. To

establish bad faith on this record, a hearing was required

to determine if the appeal was taken solely for purposes of

delay."

The teaching of these cases is clear. Bad faith

assumes some sort of impermissible motive on the part of

counsel such as harassment or delay. Because counsel's

motivation is normally not apparent on the face of the

record, a court's finding of bad faith in the absence of a

hearing is likely to be erroneous. In addition to the

court's inability to properly determine the issue of bad

faith, the lack of a hearing prevents counsel, as was the

case here, from having a meaningful opportunity demonstrate

affirmatively that the lawsuit was brought in good faith.

When, as was the case here, a finding of bad faith can

result in the imposition of a penalty in excess of $19,000

against counsel, elementary concepts of fairness dictate

that counsel be affo’rded a hearing at which to explain his

motives. Anything less denies to lawyers the right to due

process that is afforded to citizens generally in a whole

host of different contexts. Se e.g. Goldberg v. Kelly, 397

U.S. 254 (1970) , (pretermination hearing required before

34

discontinuance of welfare benefits); Fuentes v. Shevin, 407

U.S. 67 (1972) , (hearing required prior to the replevin of

personal property purchased under a conditional sales

contract); Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535 (1971), (hearing

required prior to the suspension of a driver s license),

Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565 (1975), (hearing required before

suspending pupil from school for up to 10 days); Barry v.

Barchi, 443 U.S. 55 (1979), (hearing required before suspen

sion of a horse trainer's license); Memphis Light, Gas &

Water Div. v. Craft, 436 U.S. 1 (1978) , (informal hearing

required prior to discontinuance of utility servies).

Certainly an attorney's interest in being protected against

an erroneous penalty of over $19,000 is at least as great as

the interests accorded due process protection in the above

cases.

The record in this case falls considerably short of the

standards governing the assessment of fees against an

attorney on the basis of bad faith. First, for the reasons

already discussed, there was a legitimate basis, both

legally and factually, for commencing this action. Second,

the Court made no specific finding of bad faith by Mr.

Kaimowitz and it is not at all clear from its opinion that

the court even considered this standard separate and apart

from whether the lawsuit was meritless or frivolous.

Finally, it is undisputed that there was no opportunity for

a hearing at which counsel could affirmatively demonstrate

35

his good faith conduct. Under all of these circumstances

the award of attorneys' fees against plaintiffs' former

counsel was in error.

36

i

rs

CONCLUSION

Based on the foregoing, the district court's order

dated February 3, 1984 awarding attorney's fees against

plaintiffs and their former counsel should be reversed in

its entirety.

Dated: New York, New York

September 28, 1984

Respectfully submitted,

^ j ' .* toJORGE BATISTA

ROBERT L.. BECKER

Puerto Rican Legal Defense

& Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

14th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-3360

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

37