McCleskey v. Zant Brief for Petitioners Post-Hearing Memorandum of Law

Public Court Documents

September 26, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCleskey v. Zant Brief for Petitioners Post-Hearing Memorandum of Law, 1983. a4f01e66-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5885c326-5fb3-49d3-8ae4-8d6d84f9cd71/mccleskey-v-zant-brief-for-petitioners-post-hearing-memorandum-of-law. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

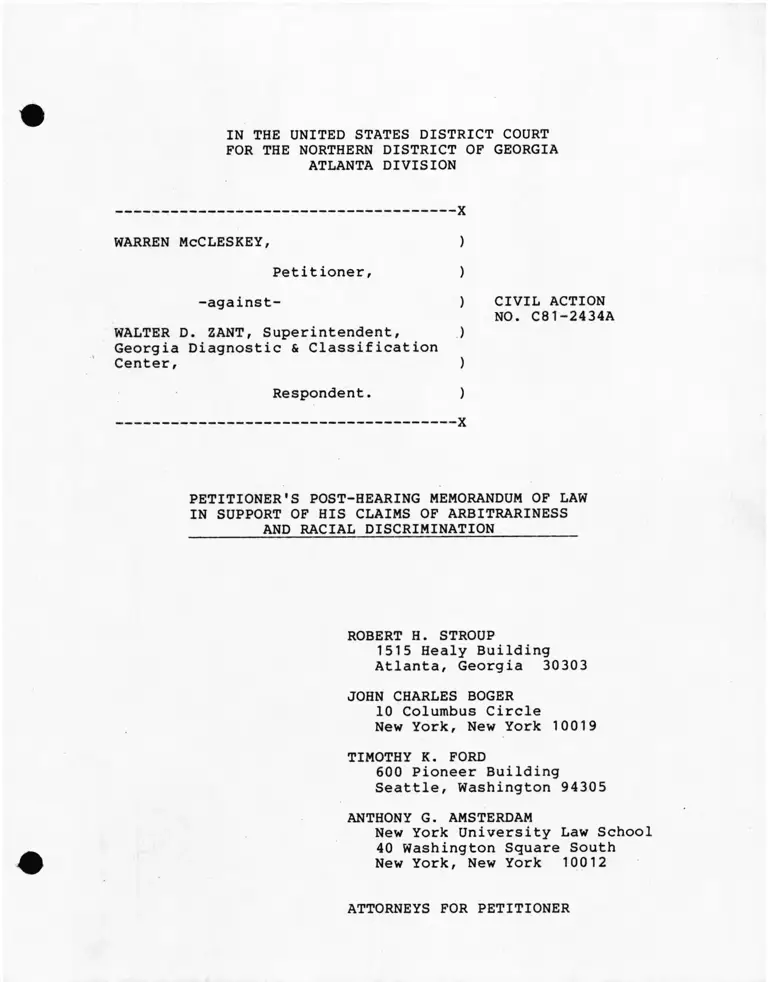

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

ATLANTA DIVISION

X

WARREN McCLESKEY, )

Petitioner, )

-against- )

WALTER D. ZANT, Superintendent, )

Georgia Diagnostic & Classification

Center, )

CIVIL ACTION

NO. C81-2434A

Respondent )

X

PETITIONER'S POST-HEARING MEMORANDUM OF LAW

IN SUPPORT OF HIS CLAIMS OF ARBITRARINESS

AND RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

ROBERT H. STROUP

1515 Healy Building

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

JOHN CHARLES BOGER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

TIMOTHY K. FORD

600 Pioneer Building

Seattle, Washington 94305

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

New York University Law School

40 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

ATTORNEYS FOR PETITIONER

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTRODUCTION ............................................ 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS ................... .................. 3

I. Petitioner's Case-In-Chief ..................... 3

A. Professor David Baldus ..................... 3

1. Areas of Expertise ..................... 3

2. Development of Research Objectives ..... 5

3. Procedural Reform Study ("PRS") ........ 7

a. Design of PRS ...................... 8

b. Data Collection for PRS ............ 11

c. Data Entry and Cleaning for PRS .... 12

4. Charging and Sentencing Study ("CSS") .. 13

a. Design of CSS ...................... 14

b. Data Collection for CSS ............ 17

B. Edward Gates ................................ 18

1. Data Collection for PRS ................ 18

2. Data Collection for CSS ................ 20

C . Professor David Baldus (resumed) ........... 21

1. Data Entry and Cleaning for CSS ....... 21

2. Methods of Analysis .................... 23

3. Analysis of Racial Disparities ......... 24

a. Unadjusted Measures of Disparities . 24

b. Adjusted Measures of Disparities ... 25

4. Racial Disparities at Different

Procedural Stages ....................... 34

5. Analysis of Rival Hypotheses ........... 35

6. Fulton County Data ..................... 36

a. Analysis of Statistical Dispari

ties ................................ 37

b. "Near Neighbors" Analysis .......... 39

c. Police Homicides ................... 40

7. Professor Baldus' Conclusions .......... 41

D. Dr. George Woodworth ........................ 42

1. Area of Expertise ....................... 42

2. Responsibilities in the PRS ............. 43

3. CSS Sampling Plan ....................... 44

4. Selection of Statistical Techniques .... 44

5. Diagnostic Tests ........................ 45

6. Models of the Observed Racial Dispari

ties ..................................... 47

l

E. Lewis Slayton Deposition ................... 48

F. Other Evidence .............................. 48

II. Respondent's Case ................................ 49

A. Dr. Joseph Katz .............................. 49

1. Areas of Expertise ..................... 49

2. Critiques of Petitioner's Studies ..... 51

a. Use of Foil Method ................ 51

b. Inconsistencies in the Data ......... 51

c. Treatment of Unknowns .............. 51

3. Dr. Katz's Conclusions ................ 52

B. Dr. Robert Burford .......................... 52

1. Area of Expertise ...................... 52

2. Pitfalls in the Use of Statistical

Analysis ................................ 53

3. Dr. Burford's Conclusions .............. 54

III. Petitioner's Rebuttal Case ..................... 54

A. Professor Baldus ............................ 54

B. Dr. Woodworth ................................ 57

1. Statistical Issues ..................... 57

2. Warren McClesky's Level of Aggravation . 58

C. Dr. Richard Berk ............................. 59

1. Areas of Expertise ..................... 59

2. Quality of Petitioner's Studies ....... 60

3. The Objections of Dr. Katz and Dr.

Burford ................................. 61

D. The Lawyer's Model .......................... 62

ARGUMENT

Introduction: The Applicable Law ....................... 63

I. The Basic Equal Protection Principles ........... 69

A. The Nature of the Equal Protection

Violations .................................. 72

gage

Page

1. The Historical Purpose of the

Amendment .............................. 72

2. Traditional Equal Protection

Principles ........ *................... 77

3. Race as an Aggravating Circumstance ... 81A

B. The Issue of Standing ..................... 84

II. The Standards for Evaluation of Petitioner's

Equal Protection Claim ......................... 86

A. The Issue of Discriminatory Intent ......... 86

B . The Legal Significance of the Statistical

Evidence ................................... 93

C . The Relevant Universe for Comparison of

Disparities ................................ 104

1. Statewide Jurisdiction ................ 104

2. The Relevant Decisionmaking Stages .... 109

3. Consideration of the Aggravation Level. 113

D. The State's Burden of Proof ............. 115

III. The Appropriate Relief ........................ 124

CONCLUSION ............................................ 126

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

ATLANTA DIVISION

WARREN McCLESKEY,

Petitioner,

-against-

-X

)

)

)

WALTER D. ZANT, Superintendent, )

Georgia Diagnostic & Classification

Center, )

Respondent. )

-X

CIVIL ACTION

NO. C81-2434A

PETITIONER'S POST-HEARING MEMORANDUM OF LAW

IN SUPPORT OF HIS CLAIMS OF ARBITRARINESS

AND RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

INTRODUCTION

Petitioner Warren McCleskey ("petitioner") has alleged in

his petition for a writ of habeas corpus two related grounds

for relief, both of which challenge the application of Georgia's

capital statute: (i) that the "death penalty is administered

arbitrarily, capriciously, and whimsically in the State of

Georgia (Habeas Petition, Claim G, 1(1[ 45-50); and, that

(ii) it "is imposed ... pursuant to a pattern and practice ...

to discriminate on the grounds of race" (Habeas Petition, Claim

H, If 11 51-53), in violation of the Eighth Amendment and the

Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.

This Court, in an order entered October 8, 1982, granted

petitioner's motion for an evidentiary hearing on his claim of

systemwide racial discrimination under the Equal ProtectionV

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. An evidentiary hearing

was held in Atlanta on August 8-19, 1983. Petitioner's case

in chief was presented through the testimony of two expert

witnesses, Professor David C. Baldus and Dr. George Woodworth,

as well as two principal lay witnesses, Edward Gates, and L.G.

Warr, an official employed by Georgia Board of Pardons and

2/

Paroles. Respondent Walter D. Zant ("respondent") offered

the testimony of two expert witnesses, Dr. Joseph Katz and Dr.

Roger Burford. In rebuttal, petitioner recalled Professor

Baldus and Dr. Woodworth, and presented further expert testi

mony from Dr. Richard Berk.

At the close of the hearing, the Court invited the parties

to file memoranda of law setting forth their principal legal

arguments. This memorandum is being submitted pursuant to that

1/ The Court noted in its order that "it appears ... that

petitioner's Eighth Amendment argument has been rejected by

this circuit in Spinkellink v. Wainwright, 578 F.2d 582, 612-14

(5th Cir. 1978) ... [but] petitioner's Fourteenth Amendment claim

may be appropriate for consideration in the context of statisti

cal evidence which the petitioner proposes to present." Order

of October 8, 1982, at 4.

2/ Petitioner also introduced the transcript of a deposition

of Lewis Stayton, the District Attorney of the Atlanta Judicial

Circuit, and offered brief testimony from petitioner's sister.

Petitioner proffered a report by Professor Samuel Gross and

Robert Mauro; the report was excluded from evidence by the Court.

2

invitation.

presented to

tions of his

In it. petitioner will first outline the evidence

3/

the Court, and then state the legal founda-

constitutional claims.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

I. Petitioner's Case-in-Chief

A . Professor David Baldus

1 . Areas of Expertise

Petitioner's first expert witness was Professor David C.

Baldus, currently Distinguished Professor of Law at the University

of Iowa. Professor Baldus testified that a principal focus of

his academic research and writing during the past decade has been

upon the use of empirical social scientific research in legal

contexts. During that time, Professor Baldus has co-authored a

4/

widely cited (see DB6) work on the law of discrimination,

see D. BALDUS & J. COLE, STATISTICAL PROOF OF DISCRIMINATION

(1980), as well as a number of significant articles analyzing the

use of statistical techniques in the assessment of claims of

3/ Due to the length and complexity of the evidentiary hearing,

and the fact that no transcript of the testimony has yet been

completed, petitioner does not purport to set forth a comprehen

sive statement of the evidence in this memorandum. Instead, the

statement of facts will necessarily be confined to a review of

the principal features of the evidence.

4/ Each reference to petitioner's exhibits will be indicated

by a reference to the initials of the witness during whose

testimony the exhibit was offered (e.g., David Baldus becomes

"DB"), followed by the exhibit number.

3

discrimination. Professor Baldus has also authored

several important analytical articles on other death penalty

6/

issues. Professor Baldus served in 1975-1976 as the

national Program Director for Law and Social Science of the

National Science Foundation (DB1, at 1), and he has been re

tained as a consultant to the Supreme Courts of Delaware and of

South Dakota to propose empirical techniques for their appellate

proportionality review of capital cases (DB1, at 4). Professor

Baldus is currently the principal consultant to the Task

Force of the National Center for State Courts on proportionality

review of capital cases. He is the recipient of numerous grants

and awards from the National Institute of Justice, the National

Science Foundation, the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, and

other organizations for his professional research on discrimina

tion in capital sentencing (jld. , 3-4). Professor Baldus has been

invited to serve on the Board of Editors of several distinguished

7/

journals concerning the issues of law and social science, and

5/

5/ See Baldus & Cole, "Quantitative Proof of Intentional Dis

crimination," 1 EVAL. QUAR. 53 (1977); Cole & Baldus, "Statistical

Modelling to Support a Claim of Intentional Discrimination,"

PROCEEDINGS, AM. STATIS. ASSN., SOC. SCI. SECTION.

6/ See Baldus & Cole, "A Comparison of the Work of Thorsten

Sellin and Isaac Ehrlich on the Deterrent Effect of Capital

Punishment," 85 YALE L.J. 170 (1976); Baldus, Pulaski, Wood-

worth & Kyle, "Identifying Comparatively Excessive Sentences

of Death," 33 STAN. L. REV. 601 (1980); Baldus, Pulaski &

Woodworth, "Proportionality Review of Death Sentences: An

Empirical Study of the Georgia Experience," J. CRIM. L. &

CRIMINOLOGY (1983) (forthcoming).

7/ Evaluation Quarterly (1976-1979); Law and Policy Quarterly

(1978-1979) (see DB1, at 3).

4

has served as a consultant to an eminent Special Committee on

Empirical Data in Legal Decision-Making of the Association of the

Bar of the City of New York.

After hearing his qualifications, the Court accepted

Professor Baldus as an expert in "the empirical study of the

legal system, with particular expertise in methods of analysis

and proof of discrimination in a legal context."

2. Development of Research Objectives

Professor Baldus testified that he first became interested

in empirical research on a state's application of its capital

puhishment statutes shortly after Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S.

153 (1976) and related cases had been announced by the Supreme

Court in mid-1976. Those cases, Baldus explained, explicitly

rested upon certain assumptions about how the post-Furman

capital statutes would operate: (i) that sentencing decisions

would be guided and limited by the criteria set forth in

capital statutes; (ii) that under such statutes, cases would

receive evenhanded treatment; (iii) that appellate sentence

review would guarantee statewide uniformity of treatment, by

corrcting any significant disparities in local disposition of

capital cases; and (iv) that the influenced of illegitimate

factors such as race or sex, would be eliminated by these

sentencing constraints on prosecutorial and jury discretion.

Professor Baldus testified that his own research and

training led him to conclude that the Supreme Court's assump

5

tions in Gregg were susceptible to rigorous empirical evalution

employing accepted statistical and social scientific methods.

Toward that end — in collaboration with two colleagues, Dr.

George Woodworth, an Associate Professor of Statistics at the

University of Iowa, and Professor Charles Pulaski, a Professor

of Criminal Law now at Arizona State University Law School —

Baldus undertook in 1977 the preparation and planning of a major

research effort to evaluate the application of post-Furman

capital statutes. In the spring semester of 1977, Professor

Baldus began a review of previous professional literature on

capital sentencing research and related areas, which eventually

comprised examination of over one hundred books and articles.

8/

(See DB13.) Baldus and his colleagues also obtained access

to the most well-known prior data sets on the imposition of

capital sentences in the United States, including the Wolfgang

rape study which formed the empirical basis for the challenge

brought in Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 F.2d 138 (8th Cir. 1968),

rev'd on other grounds, 398 U.S. 262 (1970), and the Stanford

9/

Law School study. They examined the questionnaires em-

8/ Baldus testified that his research was particularly aided

by other pioneering works on racial discrimination in the appli

cation of capital statutes, see, e.g., Johnson, "The Negro and

Crime," 217 ANNALS 93 (1941); Garfinkel, "Research Note on

Inter- and Intra- Racial Homicide," 27 SOCIAL FORCES 369 (1949);

Wolfgang & Riedel, "Race, Judicial Discretion, and the Death

Penalty," 407 ANNALS 119 (1973); Wolfgang & Riedel, "Rape, Race,

and the Death Penalty in Georgia," 45 AM. J. ORTHO PSYCHIAT.

658 (1975); Bowers & Pierce, "Arbitrariness and Discrimination

under Post-Furman Capital Statutes," 26 CRIME & DELINQ. 563 (1980).

9/ See "A Study of the California Penalty Jury in First Degree

Murder Cases," 21 STAN. L. REV. 1297 (1969).

6

researchers, and ran additional analyses to learn about factors

which might be important to the conduct of their own studies.

After these preliminary investigations, Baldus and his

colleagues began to formulate the general design of their own

research. They settled upon a retrospective non-experimental

±0/

study as the best available general method of investigation.

They then chose the State of Georgia as the jurisdiction

for study, based upon a consideration of such factors as the

widespread use in other jurisdictions of a Georgia-type capital

11/statute, the favorable accessibility of records in Georgia,

and numbers of capital cases in that state sufficiently large

to meet statistical requirements for analysis of data.

ployed in those studies, reran the analyses conducted by prior

3. Procedural Reform Study ("PRS”)

The first of the two Baldus studies, the Procedural

Reform Study, was a multi-purpose effort designed not only to

address the question of possible discrimination in the admin-

10/ Under such a design, researchers gather data from available

records and other sources on plausible factors that might have

affected an outcome of interest (here the imposition of sentence

in a homicide case) in cases over a period of time. They then

used statistical methods to analyze the relative incidence

of those outcomes dependent upon the presence or absence of

the other factors observed. Professor Baldus testified that this

method was successfully employed in, among others, the National

Halothane Study, which Baldus and his colleagues reviewed

carefully for methodological assistance.

11/ Baldus testified that he made inquiry of the Georgia De

partment of Offender Rehabilitation, the Georgia Department

of Pardons and Paroles, and the Georgia Supreme Court, all of

which eventually agreed to make their records on homicide

cases available to him for research purposes. (See DB 24.)

7

istration of Georgia's capital statutes, but to examine appellate

sentencing review, pre- and post-Furman sentencing, and other

questions not directly relevant to the issues before this Court.

Professor Baldus limited his testimony to those aspects and

findings of the PRS germane to petitioner's claims.

The PRS, initially supported by a small grant from the Uni

versity of Iowa Law Foundation, subsequently received major

funding for data collection from the National Institute of

Justice, as well as additional funds from Syracuse University

Law School. Work in the final stages of data analysis was

assisted by a grant from the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation

distributed through the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. Research data collection and analysis for the PRS

took place from 1977 through 1983.

a. Design of PRS

In formulating their research design for the PRS, Baldus

and his colleagues first identified the legal decision-points

within the Georgia charging and sentencing system which they

would study and then settled upon the "universe" of cases on

which they would seek information. After reviewing the various

stages which characterize Georgia's procedure for the disposition

of homicide cases (see DB21), Baldus decided to focus the PRS

on two decision-points: the prosecutor's decision whether to

seek a death sentence once a murder conviction had been obtained

8

trial. Baldus defined the universe of cases to

include all persons arrested between the effective date of

Georgia's post-Furman capital statute, March 28, 1973, and

June 10, 1978 (i) who were convicted of murder after trial

and received either life or death sentences, or (ii) who

received death sentences after a plea of guilty, and who either

(i) appealed their cases to the Supreme Court of Georgia (ii)

or whose cases appeared in the files of both the Department

of Offender Rehabilitation ("DOR") and the Department of Pardons

12/

and Paroles ("DPP"). This universe comprised 594 defendants.

(See DB 26.) Penalty trials had occurred in 193 of these

cases, including 12 in which two or more penalty trials had

taken place, for a total of 206 penalty trials. In all, 113

death sentences had been imposed in these 206 trials.

For each case within this universe, Baldus and his col

leagues proposed to collect comprehensive data on the crime,

the defendant, and the victim. Factors were selected for inclu

sion in the study based upon the prior research of Baldus, a

review of questionnaires employed by other researchers such as

Wolfgang as well as upon the judgment of Baldus, Pulaski and

others about what factors might possibly influence prosecutors

12/ The decision to limit the universe to cases in which a

murder conviction or plea had been obtained minimized concern

about difference in the strength of evidence of guilt. The

decision to limit the universe to cases in which an appeal had

been taken or in which DOR and DPP files appeared was a necessary

restriction based upon availability of data.

at trial; and the jury's sentencing verdict following a penalty

9

and juries in their sentencing decisions. The initial PRS

questionnaire, titled the "Supreme Court Questionnaire," was

drafted by Baldus working in collaboration with a law school

graduate with an advanced degree in political science, Frederick

Kyle (see DB 27), and went through many revisions incorporating

the suggestions of Pulaski, Woodworth, and others with whom it

was shared. In final form, the Supreme Court Questionnaire

was 120 pages in length and addressed over 480 factors or "vari

ables." After preliminary field use suggested the unwieldiness

of the Supreme Court Questionnaire, and after analysis revealed

a number of variables which provided little useful information,

a second, somewhat more abbreviated instrument, titled the

Georgia Parole Board (or Procedural Reform Study) Questionnaire,

was developed (see DB 35). Much of the reduction in size of

this second questionnaire came from changes in its physical

design to re-format the same items more compactly. Other varia

bles meant to permit a coder to indicate whether actors in the

sentencing process had been "aware" of a particular variable were

dropped as almost impossible to determine from available records

in most instances. A few items were added to the second question

naire. Eventually, information on 330 cases was coded onto the

Supreme Court Questionnaire, while information on 351 cases was

coded onto the Georgia Parole Board Questionnaire. Eighty-seven

cases were coded onto both questionnaires. (See DB 28, at

2. )

10

b. Data Collection for PRS

Data collection efforts for the PRS began in Georgia during

the summer of 1979. Baldus recruited Frederick Kyle, who had

assisted in drafting the Supreme Court Questionnaire, and two other

students carefully selected by Baldus for their intelligence and

willingness to undertake meticulous detail work. Initially, the

Supreme Court Questionnaires were filled out on site in Georgia;

quickly, however, it became evident that because of the unwield

iness of that questionnaire, a better procedure would be to gather

information in Georgia which would later be coded onto the

questionnaires at the University of Iowa. Several items were

collected for this purpose, including: (i) a Georgia Supreme

Court opinion, if one had been rendered (see DB 29); (ii) a trial

judge's report prepared pursuant to Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2537(a),

if one was available in the Georgia Supreme Court (see DB 30);

(iii) a "card summary" prepared by the Assistant to the Supreme

Court of Georgia, if available (see DB 31); a procedural record

of the case (see DB 32); (iv) an abstract of the facts, dic

tated or prepared by the coders in Georgia from the appellate

briefs in the case, supplemented by transcript information (see

DB 33); and a narrative summary of the case (see DB 3, at 3).

In addition to those data sources, Baldus and his colleagues

relied upon basic information on the crime, the defendant and the

victim obtained from the Department of Pardons and Paroles,

information on the defendant obtained from the Department of

Offender Rehabilitation, information on the sex, race and age

of the victim — if otherwise unavailable — obtained from

Georgia's Bureau of Vital Statistics, as well as information on

whether or not a penalty trial had occurred, obtained from

counsel in the cases if necessary (see DB 28; DB 36).

The 1979 data collection effort continued in the fall of

1980 under the direction of Edward Gates, a Yale graduate

highly recommended for his care and precision by former employers

at a Yale medical research facility. Baldus trained Gates and

his co-workers during a four-day training session in August,

1980, in the office of Georgia's Board of Pardons and Paroles,

familiarizing them with the documents, conducting dry run

tests in questionnaire completion, and discussing at length

any problems that arose.- To maintain consistency in coding,

Baldus developed a set of rules or protocols governing

coding of the instruments, which were followed by all the

coders. These protocols were reduced to written form, and a

copy was provided to Gates and other coders in August of 1980.

Baldus, who returned to Iowa, remained in contact with

Gates daily by telephone, answering any questions that may11/have arisen during the day's coding.

C . Data Entry and Cleaning for PRS

To code the abstracts and other material forwarded

13/ While information on most of the cases in the PRS was

gathered in 1979 and 1980, Edward Gates completed the

collection effort in the final 80 cases during the summer

of 1981. (See DB 28, at 2.)

12

from Georgia onto the Supreme Court and PRS questionnaires,

University of Iowa law students with criminal law course exper

ience, again chosen for intelligence, diligence, and care

in detailed work. The students received thorough training

from Professors Baldus and Pulaski, and they worked under the

supervision of Ralph Allen, a supervisor who checked each

questionnaire. The students held regular weekly meetings to

discuss with Professor Baldus and their supervisor any

problems they had encountered, and consistent protocols were

developed to guide coding in all areas.

Following the manual coding of the questionnaires,

Professor Baldus hired the Laboratory for Political Research

at the University of Iowa to enter the data onto magnetic

computer tape. Rigorous procedures were developed to ensure

accurate transposal of the data, including a special program

to signal the entry of any unauthorized codes by programmers.

A printout of the data entered was carefully read by profes

sionals against the original questionnaires to spot any errors,

and a worksheet recorded any such errors for correction on the

magnetic tapes (see DB 50).

3. Charging and Sentencing Study ("CSS")

In 1980, Professor Baldus was contacted for advice by the

NAACP Legal Defense Fund in connection with a grant application

being submitted to the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation seeking

funds to conduct social scientific research into the death

13

penalty. Several months later, the Legal Defense Fund informed

Baldus that the grant had been approved and invited him to con

duct the research. Under that arrangement, the Legal Defense Fund

would provide the funds for the out-of-pocket expenses of a study,

ceding complete control over all details of the research and

analysis to Professor Baldus (apart from the jurisdiction to be

studied, which would be a joint decision). Once the analysis

had been completed, Baldus would be available to testify concerning

his conclusions if the Legal Defense Fund requested, but Baldus

would be free to publish without restriction whatever findings

14/the study might uncover. After some further discussions,

the parties agreed in the fall of 1980 to focus this Charging

and Sentencing Study ("CSS") on the State of Georgia.

a. Design of CSS

The CSS, by focusing once again on the State of Georgia,

permitted Professor Baldus and his colleagues to enlarge their

PRS inquiry in several important respects: first, they were

able, by identification of a different universe, to examine

decision-points in Georgia's procedural process stretching back

to the point of indictment, thereby including information

on prosecutorial plea-bargaining decisions as well as jury guilt

determinations; secondly, they broadened their inquiry to include

14/ Baldus indeed expressly informed LDF at the outset that

his prior analysis of the Stanford Study data left him skep

tical that any racial discrimination would be uncovered by

such research.

14

cases resulting in voluntary manslaughter convictions as well

as murder convictions; and thirdly by development of a new ques

tionnaire, they were able to take into account strength-of-

evidence variables not directly considered in the PRS. Beyond

these advances, the deliberate overlapping of the two related

studies provided Professor Baldus with a number of important means

to confirm the accuracy and reliability of each study.

To obtain these benefits, Baldus defined a universe including

all offenders who were arrested before January 1, 1980 for a

homicide committed under Georgia's post-Furman capital statutes,

who were subsequently convicted of murder or of voluntary man

slaughter. From this universe of 2484 cases, Professors Baldus

15/

and Woodworth drew two samples. The first, devised accord

ing to statistically valid and acceptable sampling procedures

(see the testimony of Dr. Woodworth, infra), comprised a sample

of 1066 cases, stratified to include 100% of all death-sentenced

± 6/

cases, 100% of all life-sentenced cases afer a penalty

trial, and a random sample of 41% of all life-sentenced cases

without a penalty trial, and 35% of all voluntary manslaughter

cases. The stratification had a second dimension; Professors

Baldus and Woodworth designed the sample to include a minimum

25% representation of cases from each of Georgia's 42 judicial

circuits to ensure full statewide coverage.

15/ As indicated above, the PRS did not involve any sampling

procedures. All cases within the universe as defined were

subject to study.

16/ Because of the unavailability of records on one capitally-

sentenced inmate, the final sample includes only 99% (127 of 128)

of the death-sentenced cases.

15

The second sample employed by Baldus and Woodworth in the

CSS included all penalty trial decisions known to have occurred

during the relevant time period, on which records were available,

a total of 253 of 254. Among those 253, 237 also appeared in the

larger CSS Stratified Sample of 1066; the remaining 16 cases com

prised 13 successive penalty trials for defendants whose

initial sentences had been vacated, as well as 3 cases included

in Georgia Supreme Court files, but not in the file of the

Department of Offender Rehabilitation. (This latter sample, of

course, permitted Baldus to analyze all penalty decisions

during the period. In his analyses involving prosecutorial

decisions, Baldus explained that, since a prosecutor's treatment

on the first occasion inevitably would affect his disposition

of the second, it could be misleading to count two dispositions

of a defendant by a single decisionmaker on successive prosecutions.

When two separate sentencing juries evaluated a capital defendant,

however, no such problems arose. The two samples permitted both

analyses to be employed throughout the CSS, as appropriate.)

After a universe had been defined and a sample drawn,

Baldus began development of a new questionnaire. Since the CSS

sought to examine or "model" decisions made much earlier in the

charging and sentencing process than those examined in the PRS,

additional questions had to be devised to gather information on

such matters as the plea bargaining process and jury conviction

trials. A second major area of expansion was the effort to

obtain information on the strength of the evidence, an especially

16

important factor since this study included cases originally

charged as murders which resulted in pleas or convictions for

manslaughter. Professor Baldus devised these strength-of-evi-

dence questions after a thorough review of the professional

literature and consultation with other experts who had also

worked in this area. The final CSS questionnaires (see DB 38)

also included additional variables on a defendant's prior record

and other aggravating and mitigating factors suggested by profes

sional colleagues, by attorneys and by preliminary evaluation

of the PRS questionnaires.

b. Data Collection for CSS

Data for the CSS were collected from essentially the same

sources used for the PRS: the Department of Pardons and Paroles,

the Deparment of Offender Rehabilitation (see DB 40), the Supreme

Court of Georgia, the Bureau of Vital Statistics (see DB 47),

supplemented by limited inquiries to individual attorneys to

obtain information on whether plea bargains occurred, whether

penalty trials occurred, and the status (retained or appointed)

of defense counsel (see DB 45, at 3-6; DB 46) (see generally

DB 39).

Physical coding of the CSS questionnaires was completed

directly from the official records in Georgia by five law students

working under the supervision of Edward Gates, who had been

one of Baldus' two coders for the PRS in Georgia in 1980.

The five students were selected by Baldus after a nationwide

recruitment effort at 30 law schools; once again, Baldus

17

or Gates contacted references of the strongest candidates before

hiring decisions were made (see DB 42).

As in the PRS, an elaborate written protocol to govern data

entries was written, explained to the coders, and updated as

questions arose. (See DB 43.) After a week-long training session

in Atlanta under the supervision of Professor Baldus, Gates and

the law students remained in contact with Baldus throughout the

summer to resolve issues and questions that arose.

B. Edward Gates

At this point during the evidentiary hearing, petitioner

presented the testimony of Edward Gates who, as indicated above,

was integrally involved in data collection efforts both in the

PRS and in the CSS. Gates testified that he was a 1977 grad

uate of Yale University, with a Bachelor of Science degree in

biology. Following his undergraduate training, Gates worked as

a research assistant in the Cancer Research Laboratory of Tufts

Medical School, developing data sets on cellular manipulation

experiments, recording his observations and making measurements

to be used in this medical research. (See EG 1.)

1. Data Collection for PRS

Gates testified that he was hired by Professor Baldus in

August of 1980 to collect data for the PRS. Prior to travelling

to Georgia, he was sent coding instructions and practice ques

tionnaires to permit him to begin his training. During mid-

18

September, 1980, he met with Baldus in Atlanta, reviewed the

practice questionnaires, and met with records officials in the

Georgia Archives (where Supreme Court records were stored) and

in the Department of Pardons and Paroles. After several

additional days of training and coding practice, he worked at

the Archives each workday from mid-September until late October,

1980, reviewing trial transcripts, appellate briefs, trial

judges's reports, and Supreme Court opinions before preparing

abstracts and a narrative summary.

Gates testified that he followed the written coding

procedures throughout, and that problems or inconsistencies were

discussed with Professor Baldus each day at 4:00 p.m. When

changes in coding procedures were made, Gates testified that he

checked previously coded questionnaires to ensure consistent

application of the new protocols.

In late October, coding work moved from the Archives to the

Pardons and Paroles offices. There, Gates had access to police

report summaries completed by Pardons and Paroles investigators,

Federal Bureau of Investigation "rap sheets," field investigator

reports on each defendant, and sometimes actual police or witness

statements. Gates pointed out an illustrative example of a case

he had coded (see DB 34) and reviewed at length the coding

decisions he made in that case, one of over 200 he coded

employing the Procedural Reform Study questionnaire. In

response to questioning from the court, Gates explained that his

instructions in coding the PRS questionnaire were to draw

19

reasonable inferences from the file in completing the foils.

(These instructions later were altered, Gates noted, for

purposes of the coding of the CSS questionnaire.)

Gates left Georgia in mid-January of 1981; he completed the

final PRS questionnaires during the summer of 1981, during his

tenure as supervisor of the CSS data collection effort in

Atlanta.

2. Data Collection for CSS

During early 1981, Gates was invited by Professor Baldus to

serve as project supervisor of the CSS data collection effort.

In the spring of 1981, he worked extensively with Baldus on a

draft of the CSS questionnaire, assisted in hiring the coders

for the 1981 project, and drafted a set of written instructions

for the coders (see DB 4).

Gates came to Georgia in late May of 1981, participated

with Professor Baldus in a week-long training session with the

five law student coders, and then supervised their performance

throughout the summer. He reviewed personally the files and

questionnaries in each of the first one hundred cases coded by

the students, to ensure consistency, and thereafter he regularly

reviewed at least one case each day for each coder. At least

twice during the summer, Gates gave all coders the same file and

asked them to code and cross-check the results with those

completed by the other coders. Gates spoke frequently by

telephone with Baldus and discussed problems that arose in

interpretation on a daily basis. As in earlier collection

20

efforts, the protocols resolving questions of interpretation

were reduced to written form, the final end-of-summer draft of

which is incorporated in DB 43 (EG 5). Gates testified that he

made great efforts to ensure that all questionnaires were coded

consistently, revising all previous coded questionnaires when a

disputed issue was subsequently resolved.

Gates noted that for the CSS questionnaire, coders were

given far less leeway than in the PRS to draw inferences from the

record. Moreover, in the event of unresolved conflicting statements,

they were instructed to code in a manner that would support the

legitimacy of the conviction and sentence imposed in the case.

In sum, Gates testified that while the data for the PRS was

very carefully coded, the data effort for the CSS was even more

thoroughly entered, checked and reviewed. Both data collection

efforts followed high standards of data collection, with

rigorous efforts made to insure accuracy and consistency.

C. Professor David Baldus (resumed)

1. Data Entry and Cleaning for CSS

Upon receipt of six boxes of completed CSS questionnaires

at the end of August,' 1981, Professor Baldus testified that he

faced five principal tasks before data analysis could begin.

The first was to complete collection of any missing data,

especially concerning the race of the victim, the occurrence of

a plea bargain, and the occurrence of a penalty trial in life-

sentenced cases. As in the PRS study, he accomplished this

21

task through inquiries directed to the Bureau of Vital Statistics

(see DB 47) and to counsel in the cases (see DB 45-46). His

second task was the entry of the data onto magnetic computer

tapes, a responsibility performed under contract by the Laboratory

for Political Science. The program director subsequently reported

to Professor Baldus that, as as result of the careful data entry

procedures employed,-including a special program that immediately

identified the entry of any unauthorized code, the error remaining

in the data base as a result of the data entry process is estimated

to be less than 1/6 of 1 percent, and that the procedures he had

followed conform to accepted social science data entry practices.

Baldus' third task was to merge magnetic tapes created by

the Political Science Laboratory, which contained the data

collected by his coders in Georgia, with the magnetic tapes

provided by the Department of Offender Rehabilitation, which

contained personal data on each offender. This was accomplished

through development of a computer program under the supervision

of Professor Woodworth. Next, Professors Baldus and Woodworth

engaged in an extensive data "cleaning'' process, attempting

through various techniques — crosschecking between the PRS

and CSS files, manually comparing entries with the case sum

maries, completing crosstabular computer runs for consistency

between two logically related variables — to identify any

coding errors in the data. Of course, upon identification,

22

Baldus entered a program to correct the errors. (See DB 51).

The final step preceding analysis was the "recoding" of

variables from the format in which they appeared on the CSS

questionnaire into a binary form appropriate for machine analysis.

Professor Baldus performed this recoding (see DB 54, DB 55),

limiting the study to 230+ recoded variables considered relevant

for an assessment of the question at issue: whether Georgia's

charging and sentencing system might be affected by racial

factors.

11/

2. Methods of Analysis

As the data was being collected and entered, Professor

Baldus testified that he developed a general strategy of

analysis. First, he would determine the patterns of homicides in

Georgia and any disparities in the rate of imposition of death

sentence by race. Then he would examine a series of alternative

hypotheses that might explain any apparent racial disparities.

Among these hypotheses were that any apparent disparities could

be accounted for: (i) by the presence or absence of one or

more statutory aggravating circumstances; (ii) by the presence

or absence of mitigating circumstances; (iii) by the strength of

the evidence in the different cases; (iv) by the particular time

period during which the sentences were imposed; (v) by the

geographical area (urban or rural) in which the sentences were

imposed; (vi) by whether judges or juries imposed sentence;

17/ Among the approximately 500,000 total entries in the CSS

study, Professor Baldus testified that he found and corrected

a total of perhaps 200 errors.

23

(vii) by the stage of the charging and sentencing system at

which different cases were disposed; (viii) by other, less

clearly anticipated, but nevertheless influential factors or

combinations of factors; or (ix) by chance.

Professor Baldus also reasoned that if any racial dispari

ties survived analysis by a variety of statistical techniques,

employing a variety of measurements, directed at a number of

different decision-points, principles of "triangulation” would

leave him with great confidence that such disparities were real,

persistent features of the Georgia system, rather than statis

tical artifacts conditioned by a narrow set of assumptions or

conditions.

For these related reasons, Professor Baldus and his

colleagues proposed to subject their data to a wide variety of

analyses, attentive throughout to whether any racial disparities

remained stable.

3. Analysis of Racial Disparities

a. Unadjusted Measures of Disparities

Before subjecting his data to rigorous statistical

analyses, Professor Baldus spent time developing a sense for the

basic, unadjusted parameters of his data which could thereby

inform his later analysis. He first examined the overall

homicide and death sentencing rates during the 1974-1979 period

18/

(see DB 57), the disposition of homicide cases at

18/ Unless otherwise indicated, the Baldus exhibits reflect

data from the CSS.

24

successive stages of the charging and sentencing process (see

DB 58; DB 59) and the frequency distraction of each of the

CSS variables among his universe of cases (see DB 60).

Next, Baldus did unadjusted analyses to determine whether

the race-of-victim and race-of-defendant disparities reported

by earlier researchers in Georgia would be reflected in his data

as well. In fact, marked disparities did appear: while death

sentences were imposed in 11 percent of white victim cases,

death sentences were imposed in only 1 percent of black victim

cases, a 10 point unadjusted disparity (see DB 62). While a

slightly higher percentage of white defendants received death

sentences than black defendants (.07 vs. .04) (ijd. ) , when the

victim/offender racial combinations were separated out, the

pattern consistently reported by earlier researchers appeared:

Black Def./

White Vic.

.22

(50/228)

White Def./

White Vic.

.08

(58/745)

Black Def./

Black Vic.

. 01

(18/1438)

White Def./

Black Vic.

.03

(2/64)

b. Adjusted Measures of Disparities

Baldus testified, of course, that he was well aware that

these unadjusted racial disparities alone could not decisively

answer the question whether racial factors in fact play a real

and persistent part in the Georgia capital sentencing system.

To answer that question, a variety of additional explanatory

factors would have to be considered as well. Baldus illustrated

this point by observing that although the unadjusted impact of

the presence or absence of the "(b)(8)" aggravating

25

circumstance on the likelihood of a death sentence

appeared to be 23 points (see DB 61), simultaneous consideration

or "control" for both (b)(8) and a single additional factor

20/

— the presence or absence of the "(b)(10)" statutory factor

— reduced the disparities reported for the (b)(8) factor from

.23 to .04 in cases with (b )(10) present, and to -.03 in cases

without the (b )(10) factor. (See DB 64.)

Baldus explained that another way to measure the impact of

a factor such as (b)(8) was by its coefficient in a least

squares regression. That coefficient would reflect the average

of the disparities within each of the separate subcategories, or

cells (here two cells, one with the (b )(10) factor present, and

one with (b )(10) absent). (See DB 64; DB 65.) Still another

measure of the impact of the factor would be by the use of

logistic regression procedures, which would produce both a

difficult-to-interpret coefficient and a more simply understood

"death odds multiplier," derived directly from the logistic

coefficient, which would reflect the extent to which the presence

of a particular factor, here (b)(8), might multiply the odds that

21/

a case would receive a death sentence. Baldus testified that,

19/ O.C.G.A. § 17-10-30.(b)(8) denominates the murder of a

peace officer in the performance of his duties as an aggravating

circumstance.

20/ O.C.G.A. § 17-10-30.(b)(10) denominates murder committed

to avoid arrest as an aggravated murder.

21/ DB 64 reflects that the least squares coefficient for the

(b)(8) factor was .02, the logistic coefficient was -.03, and

the "death odds" multiplier was .97.

±9/

26

by means of regular and widely-accepted statistical calculations,

these measures could be employed so as to assess the independent

impact of a particular variable while controlling simultaneously

for a multitude of separate additional variables.

Armed with these tools to measure the impact of a variable

after controlling simultaneously for the effects of other

variables, Professor Baldus began a series of analyses involving

the race of the victim and the race of the defendant — first con

trolling only for the presence or absence of the other racial factor

(see DB 69; DB 70), then controlling for the presence or absence

of a felony murder circumstance (see DB 71; DB 72; DB 73), then

controlling for the presence or absence of a serious prior

record (see DB 74), then controlling simultaneously for felony

murder and prior record (see.DB 77), and finally controlling

simultaneously for nine statutory aggravating circumstances as

well as prior record (see DB 78). In all these analyses, Baldus

found that the race of the victim continued to play a substantial,

independent role, and the race of the defendant played a lesser,

22 /

somewhat more marginal, but not insignificant role as well.

22/ Professor Baldus testified concerning another important

measure which affected the evaluation of his findings — the

measure of statistical significance. Expressed in parentheses

throughout his tables and figures in terms of "p" values, (with

a p-value of.10 or less being conventionally accepted as "margin

ally significant," a p-value of .05 accepted as "significant,"

and a p-value of .01 or less accepted as "highly statisticaly

significant"), this measure p computes the likelihood that, if in

the universe as a whole no real differences exist, the reported

differences could have been derived purely by chance. Baldus

explained that a p-value of .05 means that only one time in

twenty could a reported disparity have been derived by chance if,

in fact, in the universe of cases, no such disparity existed. A

p-value of .01 would reflect a one-in-one hundred likelihood, a

p-value of .10 a ten-in-one hundred likelihood, that chance alone

could explain the reported disparity.

27

Having testified to these preliminary findings, Professor

Baldus turned then to a series of more rigorous analyses (which

petitioner expressly contended to the court were responsive to

the criteria set forth by the Circuit Court in Smith v. Balkcom,

671 F.2d 858 (5th Cir. Unit B 1982) (on rehearing.)* In the

first of these (DB 79), Baldus found that when he took into

account or controlled simultaneously for all of Georgia's

statutory aggravating circumstances, as well as for 75 additional

mitigating factors, both the race of the victim and the race of

the defendant played a significant independent role in the

determination of the likelihood of a death sentence. Measured

, 23/

in a weighted least squares regression analysis, race of victim

displays a .10 point coefficient, a result very highly statist

ically significant at the 1-in-1000 level. The logistic

coefficient and the death odds multiplier of 8.2 are also very

highly statistically significant. The race of defendant effect

measured by least squares regression was .07, highly statist

ically significant at the 1-in-100 level; employing logistic

measures, however, the race of defendant coefficient was not

statistically significant, and the death odds multiplier was

1.4.

23/ Because the stratified CSS sample required weighting under

accepted statistical techniques, a weighted least squares regres

sion result is reflected. As an alternative measurement, Pro

fessor Baldus performed the logistic regression here on the

unweighted data. Both measures show significant disparities.

28

defendant effects measured after adjustment or control for a

graduated series of other factors, from none at all, to over 230

factors — related to the crime, the defendant, the victim,

co-perpetrators as well as the strength of the evidence —

24/

simultaneously. (See DB 80.) Professor Baldus-emphasized

that as controls were imposed for additional factors, although

the measure of the race-of-victim effect diminished slightly

from .10 to .06, it remained persistent and highly statistically

significant in each analysis. The race of defendant impact,

although more unstable, nevertheless reflected a .06 impact in

the analysis which controlled for 230+ factors simultaneously,

highly significant at the 1-in-100 level.

Professor Baldus attempted to clarify the significance of

these numbers by comparing the coefficients of the race-of-

victim and race-of-defendant factors with those of other im

portant factors relevant to capital sentencing decisions.

Exhibit DB 81 reflects that the race of the victim factor,

measured by weighted least squares regression methods, plays

a role in capital sentencing decisions in Georgia as signif

icant as the (i) presence or absence of a prior record of

murder, armed robbery or rape (a statutory aggravating circum

stance — (b)(1)); (ii) whether the defendant was the prime

mover in planning the homicide, and plays a role virtually as

24/ This latter analysis controls for every recoded variable

used by Professor Baldus in the CSS analyses, all of which are

identified at DB 60.

Professor Baldus next reported the race-of-victim and

29

significant as two other statutory aggravating circumstances (the

murder was committed to avoid arrest — (b )(10) — and the

defendant was a prisoner or an escapee — (b)(9)). The race

of defendant, though slightly less important, yet appears a more

significant factor than whether the victim was a stranger or an

acquaintance, whether the defendant was under 17 years of age,

or whether the defendant had a history of alcohol or drug abuse.

The comparable logistic regression measures reported in DB 82,

while varying in detail, tell the same story: the race of the

victim, and to a lesser extent the race of the defendant,

play a role in capital sentencing decisions in Georgia more

significant than many widely recognized legitimate factors.

The race of the victim indeed plays a role as important as many

of Georgia's ten statutory aggravating circumstances in

determining which defendants will receive a death sentence.

With these important results at hand, Professor Baldus

began a series of alternative analyses to determine whether

the employment of other "models" or groupings of relevant

factors might possibly diminish or eliminate the strong racial

effects his data had revealed. Exhibit DB 83 reflects the

results of these analyses. Whether Baldus employed his full

file of recoded variables, a selection of 44 other variables most

strongly associated with the likelihood of a death sentence, or

selections of variables made according to other recognized

30

both the magnitude and the statist-

25/

statistical techniques,

ical significance of the race of the victim factor remained

remarkably stable and persistent. (The race of the defendant

factor, as in earlier analyses, was more unstable; although

strong in the least squares analyses, it virtually disappeared in

the logistic analyses.)

Baldus next, in a series of analyses (see DB 85- DB 87)

examined the race-of-victim and defendant effects within the

subcategories of homicide accompanied by one of the two statutory

aggravating factors, — (b)(2), contemporaneous felony, or

(b)(7), horrible or inhuman — which are present in the vast

majority of all homicides that received a death sentence (see DB

84). These analyses confirmed that within the subcategories

of homicide most represented on Georgia's Death Row, the same

racial influences persist, irrespective of the other factors

controlled for simultaneously (see DB 85). Among the various

subgroups of (b)(2) cases, subdivided further according to

the kind of accompanying felony, the racial factors continue to

play a role. (See DB 86; DB 87.)

25/ Two of Professor Baldus' analyses involved the use of

step-wise regressions, in which a model is constructed by

mechanically selecting, in successive "steps," the single factor

which has the most significant impact on the death-sentencing

outcome, and then the most significant remaining factor with the

first, most significant factor removed. Baldus performed this

step-wise analysis using both least squares and logistic

regressions. Baldus also performed a factor analysis, in which

the information coded in his variables is recombined into

different "mathematical factors" to reduce the possibility that

multicolinearity among closely related variables may be distorting

the true effect of the racial factors.

31

analysis of the racial factors — this method directly responsive

to respondent's unsupported suggestion that the disproportionate

death-sentencing rates among white victim cases can be explained

by the fact that such cases are systematicaly more aggravated.

To examine this suggesstion, Baldus divided all of the CSS cases

into eight, roughly equally-sized groups, based upon their overall

levels of aggravation as measured by an aggravation-mitigation

26/

index. Baldus observed that in the less-aggravated categories,

no race-of-victim or defendant disparities were found, since virtually

no one received a death sentence. Among the three most aggravated

groups of homicides, however, where a death sentence became a

possibility, strong race-of-victim disparities, and weaker, but

marginally significant race-of-defendant disparities, emerged.

(See DB 89.)

Baldus refined this analysis by dividing the 500 most

aggravated cases into 8 subgroups according to his aggravation/

mitigation index. Among these 500 cases, the race-of-victim

disparities were most dramatic in the mid-range of cases, those

neither highly aggravated nor least aggravated where the latitude

for the exercise of sentencing discretion was the greatest.

(See DB 90.) While death sentencing rates climbed overall as

the cases became more aggravated, especially victims within the

groups of the cases involving black defendants, such as petitioner

McCleskey, the race-of-victim disparities in the mid-range

26/ Baldus noted that a similar method of analysis was a prominent

feature of the National Halothane Study.

Professor Baldus then described yet another method of

32

reflected substantial race-of-victim disparities:

Black Def.

Category White Vic. Black Vic

3 .30 . 11

(3/10) (2/18)

4 .23 .0

(3/13) (0/15)

5 .35 .17

(9/26) (2/12/)

6 .38 .05

(3/8) (1/20)

7 .64 .39

(9/14) (5/13)

(DB 90.)

Race of defendant disparities, at least in white victim cases

were also substantial, with black defendants involved in homi

cides of white victims substantially more likely than white

defendants to receive a death sentence.

White Vic.

Category Black Def. White Def.

3 .30 .03

(3/10) (1/39)

4 .23 .04

(3/13) (1/29)

5 .35 .20

(9/26) (4/20)

6 .38 .16

(3/8) (5/32)

7 .64 .39

(9/14) (5/39)

(DB 91. )

33

the hypothesis that racial factors play a significant role in

Georgia's capital sentencing system, but they conform to the

"liberation hypothesis" set forth in Kalven & Zeisel's The

27/

American Jury. That hypothesis proposes that illegitimate

sentencing considerations are most likely to come into play

where the discretion afforded the decisionmaker -is greatest,

i.e., where the facts are neither so overwhelmingly strong nor

so weak that the sentencing outcome is foreordained.

4. Racial Disparities at Different Procedural Stages

Another central issue of Professor Baldus' analysis, one

made possible by the comprehensive data obtained in the CSS,

was his effort to follow indicted murder cases through the

charging and sentencing system, to determine at what procedural

points the racial disparities manifested themselves. Baldus

observed at the outset that, as expected, the proportion of

white victim cases rose sharply as the cases advanced through

the system, from 39 percent at indictment to 84 percent at

death-sentencing, while the black defendant/white victim

proportion rose even faster, from 9 percent to 39 percent.

(See DB 93.) The two most significant points affecting

these changes were the prosecutor's decision on whether or

not to permit a plea to voluntary manslaughter, and the prose

cutor's decision, among convicted cases, of who to take on to a

sentencing trial. (See DB 94.)

27/ H. KALVEN & H. ZEISEL, THE AMERICAN JURY 164-67 (1966).

These results, Professor Baldus suggested, not only support

34

The race-of-victim disparities for the prosecutor's decision

on whether to seek a penalty trial are particularly striking,

consistently substantial and very highly statistically significant

in both the PRS and the CSS, irrespective of the number of

variables or the model used to analyze the decision (see DB 95).

The race-of-defendant disparities at this procedural stage were

substantial in the CSS, though relatively minor and not statist

ically significant in the PRS. (Id.) Logistic regression

analysis reflects a similar pattern of disparities in both the

CSS and the PRS. (see DB 96. ).

5. Analysis of Other Rival Hypotheses

Professor Baldus then reported seriatim on a number of

different alternative hypotheses that might have been thought

likely to reduce or eliminate Georgia's persistent racial dispar

ities. All were analyzed? none had any significant effects.

Baldus first hypothesized that appellate sentence review by the

Georgia Supreme Court might eliminate the disparities. Yet

while the coefficients were slightly reduced and the statistical

significance measures dropped somewhat after appellate review,

most models (apart from the stepwise regression models) continued

to reflect real and significant race-of-victim disparities and

somewhat less consistent, but observable race-of-defendant

effects as well.

35

Baldus next hypothesized that the disparities do not reflect

substantial changes or improvements that may have occurred in the

Georgia system between 1974 and 1979. Yet when the cases were

subdivided by two-year periods, although some minor fluctuations

were observable, the disparities in the 1978-1979 period were

almost identical to those in 1974-1975. (See. DB 103.) An

urban-rural breakdown, undertaken to see whether different

sentencing rates in different regions might produce a false

impression of disparities despite evenhanded treatment within

each region, produced instead evidence of racial disparities in

both areas, (although stronger racial effects appeared to be

present in rural areas (See DB 104.)) Finally, no discernable

difference developed when sentencing decisions by juries alone

were compared with decisions from by sentencing judges and

juries. (See DB 105.)

6. Fulton County Data

Professor Baldus testified that, at the request of peti

tioner, he conducted a series of further analyses on data drawn

from Fulton County, where petitioner was convicted and sentenced.

The purpose of the analyses was to determine whether or not the

racial factors so clearly a part of the statewide capital

sentencing system played a part in sentencing patterns in Fulton

County as well. Since the smaller universe of Fulton County

cases placed some inherent limits upon the statistical operations

that could be conducted, Professor Baldus supplemented these

statistical analyses with two "qualitative" studies: (i) a "near

36

neighbors" analysis of the treatment of other cases at a level of

aggravation similar to that of petitioner; and (recognizing that

petitioner's victim has been a police officer) an analysis of the

treatment of other police victim cases in Fulton County.

a* Analysis of Statistical Disparities

Professor Baldus began his statistical analysis by observing

the unadjusted disparities in treatment by victim/defendant

racial combinations at six separate decision points in

Fulton County's charging and sentencing system. The results

show an overall pattern roughly similar to the statewide pattern:

Black Def. White Def. Black Def. White Def.

White Vic. White Vic. Black Vic. Black Vic.

.06

(3/52)

.05 .005 .0

(5/108) (2/412) (0/8)

(DB 106.) The unadjusted figures also suggest (i) a greater

willingness by prosecutors to permit defendants to plead to

voluntary manslaughter in black victim cases, (ii) a greater

likelihood of receiving a conviction for murder in white victim

cases, and (iii) a sharply higher death sentencing rate for white

victim cases among cases advancing to a penalty phase. (DB 106;

DB 107.) When Professor Baldus controlled for the presence or

absence of each of Georgia's statutory aggravating circumstances

separately, he found very clear patterns of race-of-victim

disparities among those case categories in which death sentences

were most frequently imposed (DB 108). Among (b)(2) and (b)(8)

cases — two aggravating cirstances present in petitioner's own

37

case — the race-of-victim disparities were .09 and .20 respec

tively (although the number of (b)(8) cases was too small to

support a broad inference of discrimination).

When Professor Baldus controlled simultaneously for a host

of variables, including 9 statutory aggravating circumstances,

a large number of mitigating circumstances, and factors related

to both the crime and the defendant (see DB 114 n.1 and DB

96A, Schedule 3), strong and highly statistically significant

race-of-victim disparities were evident in both the decision of

prosecutors to accept a plea (-.55, p=.0001) and the decision to

advance a case to a penalty trial after conviction (.20, p=.01)

(DB 114). Race-of-defendant disparities were also substantial

and statistically significant at the plea stage (-.40, p=.01) and

at the stage where the prosecutor must decide whether to advance

a case to a penalty trial (.19, p=.02) (DB 114). These racial

disparities in fact, were even stronger in Fulton County

than they were statewide.

Although the combined affects of all decision-points

in this analysis for Fulton County did not display significant

racial effects, Professor Baldus suggested that this was likely

explained by the very small number of death-sentenced cases in

Fulton County, which made precise statistical judgments on

overall impact more difficult.

38

b. Near Neighbors" Analysis

Aware of the limits that this small universe of cases would

impose on a full statistical analysis of Fulton County data,

Professor Baldus undertook a qualitative analysis of those cases

in Fulton County with a similar level of aggravation to petitioner

the "near neighbors." Baldus identified these neighboring

cases by creating an index through a multiple regression analysis

of those non-suspect factors most predictive of the likelihood of

a death sentence statewide. Baldus then rank-ordered all Fulton

County cases by means of this index, and identified the group

of cases nearest to petitioner. He then broke these cases, 32

in all, into three subgroups — more aggravated, typical, and

less aggravated — based upon a qualitative analysis of the

case summaries in these 32 cases. Among these three subgroups,

he calculated the death-sentencing rates by race-of-victim. As

in the statewide patterns, no disparities existed in the less

aggravated subcategory, since no death sentences were imposed

there at all. In the "typical" and "more aggravated" sub

categories, however, race-of-victim disparities of .40 and

.42 respectively, appeared. (See DB 109; DB 110.) Professor

Baldus testified that this near neighbors analysis strongly

reinforced the evidence from the unadjusted figures that racial

disparities, especially by race-of-victim, are at work not only

statewide, but in Fulton County as well.

39

c. Police Homicides

Professor Baldus' final Fulton County analysis looked

at the disposition of 10 police-victim homicides, involving

18 defendants, in Fulton County since 1973. (See DB 115.)

Among these 18 potential cases, petitioner alone received

28/

a death sentence. Professor Baldus divided 17 of the cases

into two subgroups, one subgroup of ten designated as "less

aggravated," the other subgroup of seven designated as "aggra

vated." (See DB 116.) The "aggravated" cases were defined

to include triggerpersons who had committed a serious contem

poraneous offense during the homicide. Among the seven aggra

vated cases, three were permitted to plead guilty and two were

convicted, but the prosecutor decided not to advance the cases

to a penalty trial. Two additional cases involved convictions

advanced to a penalty trial. In one of the two, petitioner's

case, involving a white officer, a death sentence was imposed;

in the other case, involving a black officer, a life sentence

was imposed.

Although Professor Baldus was reluctant to draw any broad in

ference from this analysis of a handful of cases, he did note

that this low death-sentencing rate for police-victim cases in

Fulton County paralleled the statewide pattern. Moreover,

the results of this analysis were clearly consistent with peti

tioner's overall hypothesis.

28/ One defendant, treated as mentally deranged by the system,

was not included in the analysis.

40

7. Professor Baldus' Conclusions

In response to questions posed by petitioner's counsel

(see DB 12), Professor Baldus offered his expert opinion —

in reliance upon his own extensive analyses of the PRS and CSS

studies, as well as his extensive review of the data, research

and conclusions of other researchers — that sentencing dis

parities do exist in the State of Georgia based upon the race of

the victim, that these disparities persist even when Georgia

statutory aggravating factors, non-statutory aggravating factors,

mitigating factors, and measures of the strength of the evidence

are simultaneously taken into account. Professor Baldus further

testified that these race-of-victim factors are evident at

crucial stages in the charging and sentencing process of Fulton

County as well, and that he has concluded that these factors

have a real and significant impact on the imposition of death

sentences in Georgia.

Professor Baldus also addressed the significance of the

race-of-defendant factor. While he testified that it was not

nearly so strong and persistent as the race of the victim, he

noted that it did display some marginal effects overall, and that

the black defendant/white victim racial combination appeared to

have some real impact on sentencing decisions as well.

41

D• Dr. George Woodworth

1. Area of Expertise

Petitioner's second expert witness was Dr. George Woodworth,

Associate Professor of Statistics and Director of the Statistical

Consulting Center at the University of Iowa. Dr. Woodworth

testified that he received graduate training as a theoretical

statistician under a nationally recognized faculty at the

University of Minnesota. (See GW 1.) One principal focus of

his academic research during his graduate training and thereafter

has been the analysis of "nonparametric" or discrete outcome

data, such as that collected and analyzed in petitioner's case.

After receiving his Ph.D. degree in statistics, Dr. Woodworth

was offered an academic position in the Department of Statistics

at Stanford University, where he first became professionally

interested in applied statistical research. While at Stanford,

Dr. Woodworth taught nonparametric statistical analysis, multi

variate analysis and other related courses. He was also selected

to conduct a comprehensive review of the statistical methodology

employed in the National Halothane Study, for presentation to

the National Research Council. Thereafter, upon accepting an

invitation to come to the University of Iowa, Dr. Woodworth

agreed to become the director of Iowa's Statistical Consulting

Center, in which capacity he has reviewed and consulted as a

statistician in ten to twenty empirical studies a year during

the past eight years.

42

Dr. Woodworth has published in a number of premier

refereed professional journals of statistics on nonparametric

scaling tests and other questions related to his expertise

in this case. He has also taught courses in "the theory of

probability, statistical computation, applied statistics,

and experimental design and methodology. In his research

and consulting work, Dr. Woodworth has had extensive

experience in the use of computers for computer-assisted

statistical analysis.

After hearing his credentials, the Court qualified Dr.

Woodworth as an expert in the theory and application of sta

tistics and in statistical computation, especially of discrete

outcome data such as that analyzed in the studies before the

Court.

2. Responsibilities in the PRS

Dr. Woodworth testified that he worked closely with Professor

Baldus in devising statistically valid and acceptable procedures

for the selection of a universe of cases for inclusion

in the PRS. Dr. Woodworth also reviewed the procedures

governing the selection of cases to be included in the three

subgroups on which data were collected at different times and

with different instruments to ensure that acceptable principles

of random case selection were employed.

Dr. Woodworth next oversaw the conversion of the data

received from the PRS coders into a form suitable for statistical

analysis, and he merged the several separate data sets into one

43

comprehensive file, carefully following established statistical

and computer procedures. Dr. Woodworth also assisted in the

cleaning of the PRS data, using computer techniques to uncover

possible errors in the coding of the data.

3. CSS Sampling Plan

Dr. Woodworth's next principal responsibility was the

design of the sampling plan for the CSS, including the develop

ment of appropriate weighting techniques for the stratified

design. In designing the sample, Dr. Woodworth consulted with

Dr. Leon Burmeister, a leading national specialist in sampling

procedures. Dr. Burmeister approved the CSS design, which Dr.

Woodworth found to have employed valid and statistically accept

able procedures throughout. Dr. Woodworth explained in detail

how the sample was drawn, and how the weights for analysis of the