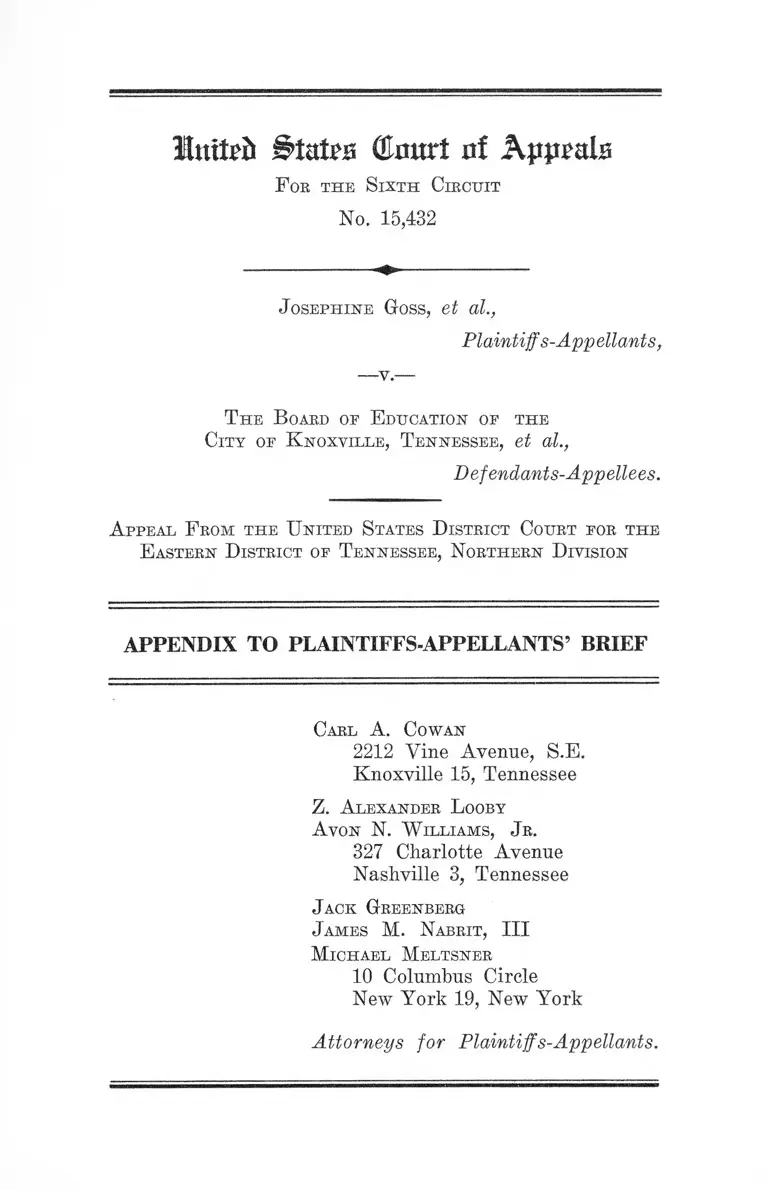

Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Appendix to Plaintiffs-Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Appendix to Plaintiffs-Appellants' Brief, 1963. 391877de-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/58a7238e-984e-43bf-b94f-f01cc02dae15/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-appendix-to-plaintiffs-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

luiteii States GImtrt nf Appeals

F ob the Sixth Cibcixit

No. 15,432

J osephine Goss, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-v-

T he B oard oe E ducation op the

City op K noxville, T ennessee, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal F bom the U nited States D istrict Court pob the

E astern District op T ennessee, Northern Division

APPENDIX TO PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue, S.E.

Knoxville 15, Tennessee

Z. Alexander L ooby

Avon N. W illiams, J r.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiff's-Appellants.

INDEX TO APPEN DIX

PAGE

Motion for Further Relief ....... ................................. 5a

Statement of Defendants in Response to Motion for

Further Relief ....................................................... 6a.

Amendment to Plan of Desegregation..................... 7a

Specifications of Objections to Amended Plan Filed

by Knoxville Board of Education ......................... 9a

Amendment to Specifications of Objections to

Amended Plan Filed by Knoxville Board of Edu

cation ................... 15a

Reply of Defendant Knoxville Board of Education

to Specifications of Objections to Amended Plan .... 16a

Report on Behalf of Board of Education of the City

of Knoxville............................................................. 18a

Specifications of Objections to Second Amended Plan

Filed by Knoxville Board of Education .............. 20a

Excerpts From Transcript—April 1, 1963 ........... 22a

Defendants’ Witnesses:

Dr. John H. Burkhart

Direct..................................................... 22a

Cross .................................................... 27a

Relevant Docket Entries ........................................... la

11

PAGE

Thomas N. Johnston

Direct ....................................... 49a

Cross ..................................................... 62a

Redirect ................................................ 103a

Recross .................................................. 104a

Exhibit No. 1 ........................... 105a

Exhibit No. 2 ............................................................. 107a

Farther Report of Board of Education of the City

of Knoxville ........................................................... 108a

Judgment .................................................................... 109a

Opinion of Robert L. Taylor, U.S.D.J....................... 112a

Notice of Appeal ....................................... 118a

Report of Changes in Desegregation Plan Made by

the Board of Education in Response to Order of

April 4, 1963 ........................................................... 119a

Proposed Action to Meet District Court’s Decree on

Desegregation ......................................................... 120a

1962

June 8

June 18

June 22

Aug. 3

Ittttefn States iiatrirt (tart

Civil Docket 3984

J osephine Goss, et al.,

—v.-

Plaintiffs,

T he Boabd op E ducation op the

City op K noxville, Tennessee, et al.,

Defendants.

R elevant D ocket Entries

Mandate and copy of Opinion of U. S. Court of

Appeals, affirming in part, modifying in part,

and remanding cause for further proceedings,

filed.

Motion for further relief on behalf of plaintiffs,

filed.

Statement of Defendants in Response to Motion

for Further Relief Filed.

Mandate and copy of Opinion of U. S. Court of

Appeals affirming judgment except insofar as

it pertains to transfer procedures and remand

ing case to District Judge with instructions to

retain jurisdiction and to require an amendment

that will permit all students to transfer as a

matter of right, when they qualify for the courses

which they desire to take in another one of the

two high schools here involved, and such course

is not available to them in the school they are

attending, filed.

2a

Aug. 15 Amendment to plan of desegregation to include

the fourth grade, as well as the third grade,

effective September 1, 1962, filed.

Sept. 18 Specifications of Objections to Amended Plan

filed by Knoxville Board of Education filed.

Sept. 19 Amendment to Specifications of Objections to

Amended Plan filed by Knoxville Board of Edu

cation, filed.

Oct. 16 Reply of defendant Knoxville Board of Edu

cation to specifications of objections to amended

plan, filed.

1963

Mar. 16 Certified copy of resolution of Board of Educa

tion, filed.

Mar. 16 Report on behalf of Board of Education of the

City of Knoxville, filed.

Mar. 28 Specifications of objections to second amended

plan filed by Knoxville Board of Education, filed.

April 1 Further Report of Board of Education of the

City of Knoxville filed.

April 1 Exhibits No. 1 and 2, filed.

April 1 Order of hearing of specifications of objections

to amended plan, evidence and statements of

counsel heard, the Court approved the plan of

desegregation through the sixth grade in Sep

tember 1963; Ordered that distributive educa

tion classes be made available to Negroes—either

in white or negro schools; ordered that Negroes

be admitted to Van Gilder School or that a

similar facility be made available to Austin High

School, entered in Civ. Ord. Bk. 25, page 57.

Relevant Docket Entries

3a

April 4 Judgment and order that the Board of Education

put plan of desegregation as amended into ef

fect, including the desegregation of the summer

high schools; that the Board take further action

effecting such change in administration and

transfer procedures in the Fulton Vocational and

Technical Plan as shall make said plan fully

conform to the opinion of the Court of Appeals,

Sixth Circuit announced on July 6, 1962; that

the Board shall effectuate such enlargement or

change in its administration of that portion of

its educational program known as the Vangilder

Program so as to provide equal and like courses

of training at Austin or other Negro high school

for the Negro pupils, or if such not be provided,

so as to admit pupils to the school teaching and

facilities in this program without regard to race;

and likewise the distributive education courses

now provided by the Board; that the jurisdic

tion of the action is retained during period of

transition, to all of the foregoing action of the

court except Paragraph 2(d) the plaintiffs ex

cept, entered in Civil Order Book 25, page 67

and filed.

April 29 Opinion of Judge Robert L. Taylor as rendered

from the Bench, that the Board file an amended

plan with respect to Fulton High School showing

that it complied with mandate of Court of Ap

peals ; that classes for children comparable to

those which are now being operated in white

schools be made available and that the colored

children who qualify be admitted to classes if

and when they apply; in all other respects the

Relevant Docket Entries

4a

Relevant Docket Entries

amended plan is approved; classes will be made

available for the distributive education colored

students within a reasonable time; the original

opinion stands as amended by Court of Appeals

in the mandate; and counsel to prepare and pre

sent order in conformity with views expressed

herein, filed.

May 2 Notice of Appeal filed.

May 7 Original copy of Transcript of Proceedings on

Specifications of Objections to Amended Plan

filed.

May 15 Report of changes in desegregation plan made

by the Board of Education in response to Order

of April 4, 1963 filed.

5a

M otion for Further R e lie f

I n the

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F oe the E astern District of T ennessee

Northern Division

[ same t it l e ]

Come the plaintiffs and respectfully move the Court

to require the defendants to file immediately, a supplemen

tal plan for accelerating desegregation of the City Schools

of Knoxville, Tennessee as of the beginning of the 1962-

1963 academic school year, in accordance with the mandate

and opinion of the United State Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit filed in this Court on 8 June 1962, said opin

ion having been rendered and filed by the Court of Appeals

with its Clerk on 3 April 1962.

Z. Alexander L ooby and

Avon N. W illiams, J r.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue, S.E.

Knoxville 15, Tennessee

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

6a

Statem ent o f D efendants in R esponse to M otion

fo r Further R e lie f

I n the

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F ob the E astern D istrict oe T ennessee

Northern Division

[ sam e t it l e ]

In response to motion for further relief filed by Plaintiff,

Defendants say that the pressure of problems of annexa

tion and the proposal of consolidation has delayed comple

tion of an amended plan of desegregation, and may fur

ther delay this but Defendants expect to file such a plan

by August 1st of this year. Since the plan is not to be

effective until September, it is believed that Plaintiffs

will not suffer hardship if the plan is filed by August 1st.

S. F rank F owler

7a

A m endm ent to P lan o f D esegregation

I s THE

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F or the E asters District of T essessee

Northern Division

[ same t it l e ]

Pursuant to the opinion and mandate of the Court of

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit filed herein on June 8, 1962,

the defendant Board of Education has amended the plan

of desegregation for the public schools of Knoxville, Ten

nessee, which plan was filed herein on April 8, 1960.

The amendatory action consisted of the adoption of a resolu

tion which concurred in the recommendation of Superin

tendent Johnston that the school integration schedule be

stepped up to include the fourth grade, as well as the third

grade, effective September 1, 1962. A copy of the rele

vant portion of the minutes is attached.

This August 14th, 1962.

S. F rank F owler

Attorney for Defendants

1412 Hamilton National Bank Building

Knoxville, Tennessee

8a

EXCERPT FROM SPECIAL MEETING OF THE

BOARD OF EDUCATION, KNOXVILLE, TENNES

SEE ANNEXED TO AMENDMENT

Minutes of a special meeting of the Board of Education

held in the office of the Board at Fifth and Central at 12:00

noon on Monday, June 25, 1962.

Members present: Dr. Burkhart, Mrs. Chapman, Mr.

Linville, Mr. Ray and Mr. Shafer.

I ntegration Schedule

Superintendent Johnston recommended that the school

integration schedule be stepped up to include the 4th grade

as well as the 3rd grade, effective September 1, 1962.

On motion made by Mr. Ray and seconded by Mr. Lin

ville, it was moved that the Board concur in the Superin

tendent’s recommendation. Motion carried.

9a

Specifications o f O bjections to A m ended P lan F iled

by K n oxv ille Board o f E ducation

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the E astern District of T ennessee

Northern Division

[ same t it l e ]

The plaintiffs, Josephine Goss, et al., respectfully object

to the amended plan filed in the above entitled cause on

or about the 14th day of August, 1962, by the defendant,

The Board of Education of the City of Knoxville, Ten

nessee, and specify as ground of objection the following:

1. That the amended plan, providing that the school

integration schedule be stepped up to include the fourth

grade as well as the third grade, effective September 1,1962,

does not provide for elimination of racial segregation of

the public schools of Knoxville “with all deliberate speed”

as required by the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

2. That the amended plan does not take into account the

period of over five (5) years which elapsed during which

the defendant, Knoxville Board of Education, completely

failed and refused to comply with the said requirements

of the due process and equal protection clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States as enunciated by the decisions of the Supreme Court

in Brown v. Board of Education on May 17, 1954,—347

U S 483, 74 S. Ct. 686 and on May 31, 1955,-349 U S 294,

10a

75 S. Ct. 753. The defendant refused to put any plan into

effect until September 1960 when the grade a year plan was

initiated pursuant to a judgment of this Court on August

20, 1960.

3. The amended plan does not take into account the

period of over eight (8) years which have elapsed since

the first Brown decision.

4. The amended plan adopted at this late date does

not meet either the spirit or specific requirements of the

decision of the Supreme Court, and the decision of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (April

3, 1962).

5. That the additional eight (8) years period provided

in said plan does not realistically and promptly accelerate

desegregation and does not comply with the Mandates of

the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals for “good faith

compliance at the earliest practicable date.”

6. That the additional eight (8) year period provided

in said plan is not “necessary in the public interest” and is

not “consistent with good faith compliance at the earliest

practicable date” in accordance with the said requirements

of due process and equal protection clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

7. The defendants have not carried their burden of

showing any problems related to public school administra

tion arising from:

a. “the physical condition of the School Plant”;

b. “the school transportation system”;

Specifications of Objections to Amended Plan

11a

c. “personnel” ;

d. “revision of school districts and attendance areas

into compact units to achieve a system of determining

admission to the public schools on a non-racial basis” ;

e. “revision of local laws and regulations which may

be necessary in solving the foregoing problems” ;

as specified by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of

Education (May 31, 1955), 349 U S 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99

L Ed 653, which necessitate the additional time contem

plated by their plan for compliance with the constitutional

requirements of a racially unsegregated public educa

tional system.

8. That the amended plan forever deprives the infant

plaintiffs and all other Negro children now enrolled in

the public schools of Knoxville, Tennessee above the fourth

grade of their rights to a racially unsegregated public edu

cation, except for the courses of technical and vocational

training available for Negro students at Fulton High

School when said courses are not offered at Austin High

School, and for this reason violated the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment of

the Constitution of the United States.

9. That the amended plan fails to eliminate racial segre

gation in technical and vocational training and forever de

prives infant plaintiffs and all other Negro children en

rolled in the public schools of Knoxville above the fourth

grade of their rights to enroll in and attend Fulton Tech

nical High School and other special technical and voca

tional schools, except for the narrow and restricted excep

tion mentioned hereinabove, as to which residence is not

Specifications of Objections to Amended Plan

12a

based on location of residence and for this reason does

not comply with the decisions of the Supreme Court in

Brown v. Board of Education, Supra, and violates the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States. Con

siderations based on race are involved in all of the pres

ent practices and plans of the defendant Board as to

whether or not a student seeking technical and vocational

training is required to enroll and attend Fulton High School

or is required to enroll and attend Austin High School, and

the racial factors therein provided are manifestly designed

and necessarily operate to perpetuate racial segregation.

Said plaintiffs and those similarly situated are thereby de

prived of due process of law and the equal protection of the

laws, is violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the

Constitution of the United States.

10. That the amended plan forever deprives the infant

plaintiffs and all other Negro children now enrolled in the

public schools of Knoxville above the fourth grade of their

rights to enroll in and attend summer schools as to which

enrollment is not based on location of residence, and for

this reason, said plan does not comply with the decisions

of the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education,

Supra, and violates the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

11. That the amended plan forever deprives the infant

plaintiffs and all other Negro children now enrolled in the

public schools of Knoxville above the fourth grade of their

rights to enroll in and attend schools or classes for handi

capped children, schools or classes for gifted children and

any other educational training of a specialized nature as to

Specifications of Objections to Amended Plan

13a

which enrollment is not based on location of residence, and

for this reason said plan does not comply with the decisions

of the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education,

Supra, and violated the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States.

W herefore, the P laintiffs P ray:

1. That the Court advance this cause upon the docket

and set the matter for hearing on an early date certain,

upon the amended plan of the defendant Board of Education

of the City of Knoxville and plaintiffs’ above objections

thereto.

2. That the said plan now proposed by defendant Board

of Education of the City of Knoxville be disapproved by the

Court as not conforming to the due process and equal pro

tection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States.

3. That the Court order the defendant Board to submit

a supplemental and realistic plan forthwith that will sub

stantially and promptly accelerate desegregation and there

by comply with the Mandates of the Supreme Court and the

Court of Appeals for “good faith compliance at the earliest

practicable date,” as to the remaining eight grades; and

as to the summer schools or courses, technical and voca

tional schools or courses, schools or courses for handi

capped children and schools or courses for gifted children

and any other educational training of a specialized nature

and as to which enrollment is not based on location of resi

dence, in the public school system of Knoxville; that said

supplemental plan to be effective not later than the be

Specifications of Objections to Amended Plan

14a

ginning of the Winter Semester or Term of the City

Schools of Knoxville in January, 1963.

Respectfully submitted,

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue, S.E.

Knoxville 15, Tennessee

Z. Alexander L ooby

Avon N. W illiams, J r.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville, Tennessee

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Specifications of Objections to Amended Plan

15a

A m endm ent to Specifications o f O bjections to

A m ended P lan F iled by K n oxville Board o f

E ducation

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the E astern District oe T ennessee

Northern Division

[ same t it l e ]

Come the plaintiffs, Josephine Goss, et al., in this cause

and amend their Specifications of Objections, heretofore

filed on September 18, 1962 and before a responsive plead

ing was filed, to the Amended Plan of the defendant, The

Board of Education of the City of Knoxville, Tennessee

by striking out the first word, to-wit, “residence” in line

eight (8) of section nine (9) on page three (3) thereof

and inserting in lieu thereof the word “enrollment”.

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue, S.E.

Knoxville 15, Tennessee

An Attorney for Plaintiffs

16a

R eply o f D efendant K n oxv ille Board o f Education

to Specifications o f O bjections to A m ended P lan

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the E astern D istrict of T ennessee

Northern Division

[ same t it l e ]

In reply to specifications of objections to amended plan

filed by the Knoxville Board of Education, which specifica

tions were filed herein on September 18, 1962, the defen

dants say as follows:

The amended plan, to which the objections are addressed,

presents a good faith determination by the defendant Board

of Education in expediting the desegregation process in

the public schools of Knoxville, Tennessee, in full compli

ance with the decision in this case of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.

The objections merely seek a reconsideration of factual

matters which were fully and deliberately explored and

considered in the various hearings that have already taken

place in this case and in this Court. Some of the objections

specified are simply copied from objections previously filed

to the plan originally submitted. There is no reason why

this case should be retried upon facts found to be true by

this Court and accepted by the Court of Appeals.

The defendant Board of Education in good faith has de

termined the full extent to which the mandate of the Court

17a

Reply of Defendant Knoxville Board of Education

to Specifications of Objections to Amended Plan

of Appeals, directing speedier desegregation, can be car

ried out under the circumstances of this community. It

appears inequitable that the defendant should be subjected

to the harassment of repeated petitions to this Court.

S. F rank F owler

Attorney for Defendant

18a

R eport on B eh a lf o f Board o f E ducation o f the

City o f K n oxville

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob the E astern D istrict of T ennessee

Northern Division

[ sam e t it l e ]

On behalf of the defendant Board of Education of the

City of Knoxville it is reported that at a meeting duly held

on March 11, 1963, it was decided to desegregate grades

five and six, in accordance with the plan filed with the court.

Certified copy of the resolution is attached hereto.

S. F rank F owler

Attorney for Board of Education

of the City of Knoxville

Dated: March 15,1963

19a

EXCEEPT FEOM MINUTES OF THE EXECUTIVE

SESSION OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION,

KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE ANNEXED TO RE

POET

P olicy Relative the Desegregation of the

K noxville City S chools

On motion made by Mr. Ray and seconded by Mr. Lin-

ville, it was moved that the Board concur in the Superin

tendent’s recommendation and establish as the Board’s

policy that effective with the school year 1963-64 desegre

gation would apply to the fifth and sixth grades. Motion

was carried by unanimous vote of the Board.

It is certified that the foregoing motion was duly adopted

at an executive meeting of the Knoxville Board of Educa

tion duly held on March 11,1963.

/ s / Alex A. S hafer

Alex A. Shafer

Secretary

Knoxville Board of Education

20a

Specifications o f O bjections to Second A m ended

Plan F iled by K n oxv ille Board o f E ducation

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob the E astern D istrict of T ennessee

Northern Division

[same title]

The Plaintiffs, Josephine Goss, et al., respectfully ob

ject to the Second Amended Plan filed in the above entitled

cause on or about the 15th day of March 1963 by the de

fendant, The Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

Tennessee; and specify as ground of objection the same

Specifications of Objections and applicable prayers there

to filed by the said Plaintiffs on September 18, 1962 to the

Amended Plan filed by said defendant on the 14th day of

August, 1962, and, therefore, pray that the same be incor

porated herein by reference, except that Prayer No. 3 be

modified to the extent that said supplemental and realistic

plan to be effective not later than the beginning of the

Summer Term of the City Schools of Knoxville in June

1963. Plaintiffs further pray that the Court hear this mat

ter together and along with the Amended Plan of the de-

21a

Specifications of Objections to Second Amended Plan

fendant, and plaintiff’s objections thereto, which have been

docketed for a hearing on the 1st day of April, 1963.

Respectfully submitted,

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue, S.E.

Knoxville, Tennessee

Z. A lexander L ooby

Avon N. W illiams, J r.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville, Tennessee

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

22a

E xcerpts From Transcript

A pril 1 , 1 9 6 3

* # # * #

- 3 6 -

Dr. J ohn H. Burkhart, called as a witness by and on

behalf of the defendant, a fte r having been first duly sworn,

was examined and testified as follow s:

Direct Examination by Mr. Fowler:

Q. Tour name is Dr. John Burkhart? A. Yes, sir.

Q. You are chairman of the Board of Education, City

of Knoxville? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Were you chairman at the time of the adoption of the

grade-a-year desegregation plan? A. Yes, sir.

—37—

Q. Have you been chairman continuously since? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Are you an active practicing physician? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. To which set of duties do you devote most of your

time, your physician duties or School Board duties? A.

To my physician duties.

# # # #

By Mr. Fowler:

Q. Dr. Burkhart, you are generally familiar with the

progress of the desegregation process in the Knoxville city

schools? A. Yes, sir.

—38—

Q. Since the beginning. We have two or three issues for

examination here today as a result of the colloquies that

have gone along so far in this court room and one of them

concerns the speed of the desegregation process. Origi

nally it was to proceed at one grade a year.

23a

Now after the case had been to the Court of Appeals and

the speed-up so directed by that Court, what action did the

Board of Education of Knoxville take? A. In August, I

believe, of last year the Board determined that because of

this command, and also because it was its feeling that—

Mr. Williams: We object to the Board’s feeling.

The Court: Overruled. Go ahead.

The Witness: I am sorry, I didn’t hear that ob

jection.

The Court: Counsel objected and the Court passed

on the objection. He objected to your feeling, but I

will let that go into the record.

A. (Continuing) The Board acts in accord to how the

Board feels in any matter, its opinion, as regards policy

in the school system.

The Court: In that connection, Dr. Burkhart, so

as the record will be clear, when you use the word

“feel” if you mean your personal feelings, the ob-

—39—

jection would be technically good and the Court

would have to sustain it, but when you use the word

“feeling”, if that implies the judgment or the opinion

of the Board after deliberation, and so forth, then

it is competent.

A. (Continuing) Well, sir, judgment would have been a

better word. Judgment is the word I should have used.

It is the Board’s judgment, collective judgment, that the

desegregation process had proceeded very smoothly with

out any difficulty and that it could without harming the

administrative function and the educational processes of

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Direct

24a

tlie children involved, speed its plan up by desegregating

two years in the fall of 1962, grades three and four.

I t has since acted again on the same basis to desegregate

two more grades beginning in the fall of this year, com

pleting the desegregation of the elementary grades.

And this, I might point out, is something that will be

three grades ahead of what the requirement was in the

grade-a-year plan.

By Mr. Fowler:

Q. And you will actually finish the whole twelve grades

earlier than the City of Nashville on its grade-a-year which

—40—

started about three years earlier? A. Yes, sir.

Mr. Williams: That is objected to, if your Honor

please.

The Court: Overruled. Go ahead.

By Mr. Fowler:

Q. Why did the Board determine to go faster, the two

grades, Dr. Burkhart? A. Well, it is our judgment that

this is still a transitional period of adjustment, that we

must act in view of experience, as our experience seems

to indicate, and that the two years is as fast as we felt

we could go with propriety.

Now there are other opportunities all along for the

Board to speed up or drop back, I suppose, to the one

grade-a-year proposition, but it was our feeling that we got

to the elementary level.

There is a rather arbitrary division, but there is a divi

sion in your school levels. Elementary, junior high and

senior high—and that we could start there possibly and

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Direct

25a

then make a decision in the following year about the pro

cedure from there on.

Q. With respect to the Fulton plan, it has been sug

gested that there have been some improprieties in the ad

ministration of the plan of transfer of Negro applicant pu-

—41—

pils to Fulton High School, perhaps you will know the

workings of a transfer plan. Have you any decision about

that? A. Well, yes, sir. I regret that the notice to appear

here this morning to testify has been of such recent date

I have not had an opportunity to refresh my memory on

many of the actions and policies of the Board, but it is my

opinion now, as of now, that the transfer provisions as re

spects Fulton are the same transfer provisions for all ap

plicants at Fulton for the vocational courses. Because

Fulton is our vocational high school, and also for the whole

city, and also our academic high school for a certain district

or area, so the provision, the transfer provisions and how

the student in other district applies for transfer to that

school, is the same.

—45—

* # # # #

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Direct

By Mr. Fowler:

Q. Do you know anything about the handicapped and

crippled children and the gifted children matters to which

—46—

Mr. Cowan was referring this morning? A. We have a

program, or special program, for gifted children.

As respects the handicapped, the only program that I

can think of just now that we have which is not integrated

up to the sixth grade as, or will be as through the sixth

grade this fall, is the Van Gilder Occupational Training

26a

Center which is an experimental program started some two

or three years ago which has been over-crowded and very

much cramped for space with a backlog of applicants since

the first day it opened and which is for children above the

seventh grade.

As regards the others, they are integrated.

The Court: Read that last answer. This is the

gifted children ?

The Witness: This is the handicapped.

The Court: Above the seventh grade, what is it?

The Witness: We have the Van Gilder Occupa

tional Training Center. It is a shelter work-shop

experimental program for junior high school stu

dents only, to train them to work with machines and

materials.

Originally it was planned to be held at the Van

Gilder School which is why it is named Yan Gilder,

—47—

but the school was not adequate and it was moved

and is now part of the building at Moses School.

Since we have not desegregated past the sixth

grade, this is still a segregated part of our system.

The Court: Is it integrated from the sixth grade

down?

The Witness: No, it doesn’t include students from

the sixth grade down. The handicapped children

from the sixth grade down, that program is inte

grated.

The Court: Then that goes along with the plan?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: It isn’t any different from the other

plan?

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Direct

The Witness: That is correct.

The Court: All right.

Mr. Fowler: That is all.

The Court: What about the gifted children?

The Witness: We have no program for the gifted

children, no special classes, no special program for

gifted children on any age level.

Mr. Fowler: You may ask him.

—4 8 -

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams:

Q. Dr. Burkhart, you are familiar with this, is there a

difference between a multiple handicapped child and the

educatable mentally retarded? A. I am sorry, Mr. Wil

liams.

Q. Is there a difference between a multiple handicapped

child and the educatable mentally retarded child? A. Mul

tiple handicapped?

Q. Yes. I mean, for example, a child with cerebral palsy

or something like that. A. We distinguish between the

severely mentally retarded and educatable mentally re

tarded.

Q. You have special classes for these children, don’t you?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you have been keeping the handicapped children

segregated above the grade level of the desegregation also,

haven’t you ?

Mr. Fowler: May I have that question read ?

Q. You have been keeping these handicapped children

segregated above the level of your plan? A. I believe so.

Q. And this is likewise true of the educatable mentally

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

28a

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

—49—

retarded, you have segregated classes for them? A. Above

the levels ?

Q. Yes. A. Yes.

Q. Did you know that according to the testimony of your

superintendent before the last hearing you don’t have but

about four hundred total Negro and white edueatable men

tally retarded in the entire school system, or didn’t have

at that time; did you know that? A. No. I am not aware

of the statistics on the matter without reviewing, and I

haven’t had an opportunity to review.

Q. What statistics have you reviewed since 1962? A.

Well, I couldn’t tell you. I review many statistics but I

haven’t reviewed any since I was ordered to appear in this

court to testify two days ago.

Q. You haven’t reviewed any since you last testified

here either, have you, regarding this problem? A. Oh, yes,

I have reviewed—

Q. What statistics have you reviewed? I am not asking

you to give figures at the moment. I believe Mr. Johnston

will have that. I am asking you to state what documents

you have reviewed pertaining to the desegregation prob

lem since you were last here in court? A. Well, I have

—50—

been furnished periodically with attendance figures of all

the schools, and the figures I don’t have that you quoted

as regards how many EMRs, SMRs children we have,

and we are furnished those regularly, and an annual report

of our school system annually.

Q. Did you review any figures after the Sixth Circuit

Court of Appeals said that you all ought to accelerate?

A. Oh, yes.

Q. You did? All right, what figures did you review?

29a

A. Our attendance figures as respecting the grade dis

tribution in all of our schools, we review periodically.

Q. How many Negro students did you find would be at

tending—out of the total how many Negro students did you

find would be eligible to attend white schools if you de

segregated all grades ? A. I don’t know.

Q. Did you have that before you? A. I had that.

Q. You had that before you? A. Yes, sir, over a year

ago.

Q. And you had it before you how long—you had before

you what your desegregation experience was the first year

—51—

of desegregation, didn't you ? A. Yes, sir.

Q. First and second year? A. No, sir.

Q. And that experience showed that you all had trans

ferred all your white students out of your Negro schools,

did it not? A. I didn’t understand that question.

Q. That experience had shown that all white students

who were allegedly assigned to Negro schools were per

mitted to, just go on back to the white schools; that was

shown by that experience, wasn’t it? A. I believe so. I

don’t recall any occasion of a white student at a Negro

school.

Q. That experience likewise showed that approximately,

only approximately one-third of the Negroes who were eli

gible to attend the white schools were attending them, did

it not? A. I don’t recall the figures.

Q. Well, do you have in mind any vague idea, Dr. Burk

hart, of how many Negro children and white children would

be involved in desegregated situations if you desegregated

the whole system? A. Not at the present time without

review.

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

30a

Q. Well, you knew as late as two days that you were

—5 2 -

going to be here today, didn’t you ? A. Yes, sir.

Q. You were subpoenaed here to testify! A. Yes, sir,

two days ago.

Q. Well, it wouldn’t take you long, you have got your

superintendent here who is very able, I must say, who re

viewed these statistics, he has got them in his file, hasn’t

he! A. Yes, sir.

Q. And it would have taken you just fifteen minutes to

glance over that instrument and refresh your recollection

on it, wouldn’t it! A. I don’t know how long it would have

taken.

Q. Well, as a matter of fact, Dr. Burkhart, you all just

decided that one year was enough last fall, didn’t you, your

decision that you just desegregate one year! A. Two

years.

Q. Two years! A. Yes, sir.

Q. Well, when you first filed your plan it was to desegre

gate one additional year, wasn’t it f A. Right.

Q. And then you decided later to desegregate two addi

tional years! A. And an additional year above the one

—52—

that we were required by the plan, and then this year

another additional year.

Q. So you just desegregated one additional year in addi

tion to the one that you were required under your old plan!

A. One additional; yes, sir.

Q. And you did not decide to do that until after we had

in fact, counsel had brought in and filed a motion for further

relief, you knew about that, didn’t you! A. Yes, sir.

Q. This decision came down in April. Did your counsel

come out and tell you that the Court of Appeals had stated

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

31a

in the opinion of the Court that it expected the Board to

move before September and counsel stated to the Court,

in substance, that he expected the Board would move to

accelerate? A. Yes, sir. Our counsel kept us informed.

Q. And you likewise knew that the plaintiff should have

an opportunity to object to your plan if you should move

too slowly, didn’t you? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Why then did the Board wait until August just before

school opened to file this accelerated plan so that the plain

tiff did not have time to object and get a hearing? A.

—54—

I can’t tell you why the Board waited until August. It was

August before the Board acted upon it.

Q. Just the way the Board has acted throughout this

case, just waiting on something, isn’t that true? A. I don’t

care to answer that question. You are asking—

Q. The Board did not have a real reason for doing that,

did it, Dr. Burkhart? A. Well, the Board has, if I may

answer in this way, the Board has many other things that

it must consider, and it acts upon—there are other matters

before the Board of Education, many other matters.

Q. But the Board has considered those other matters

for many, many years now and do you think it is about time

the Board got around to giving a little attention to this mat

ter? A. I think the Board has given it considerable at

tention.

Q. Did you have any problem of transportation in re

gard to—did you discuss any problem of transportation in

determining to desegregate one grade extra last year? A.

Do you mean did we think that this would create or solve

problems ?

—55—

Q. No, I mean did you have any objective scientific ma

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

32a

terial before you to justify your determination to deny the

constitutional rights of several thousand children? A. We

acted always in my judgment on the basis of the facts

that we had at our disposal and the judgment of our Board

as to what constituted the maintenance of good educational

procedures through our system.

Q. Now what I am asking you is name some of the facts,

just a few of the facts. A. Name—

Q. Any of the facts on which you based your alleged judg

ment of yours. A. All right. We felt that, it was our

judgment, that to proceed rapidly, more rapidly than we

were proceeding would interrupt our educational processes

by causing possibly some upheaval of the administrative

procedure in the schools, of causing some community ac

tivity which would be not in the best interest of our chil

dren, and that since this was a matter that needed to be

worked out with some degree of caution that we were pro

ceeding fast enough.

Q. Now what upheaval of administrative procedure are

you talking about? What evidence did you have before

you of any administrative upheaval? A. Not any evi-

—56—

dence that it had happened but evidence that it might

happen.

Q. What evidence did you have that it might happen? A.

Because when you change the zoning you create shifts of

students population back and forth in a rapid way which

would cause a great deal of administrative difficulty.

Q. Well, you rezoned the entire school system in one or

two months in 1960, didn’t you? A. Not our entire system,

I don’t believe. Some certain areas.

Q. You mean that your superintendent was mistaken

when at the hearing he brought in and exhibited to the

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

33a

Court a zoning map showing the rezoning of the entire

school system? A. We did not change, I don’t believe,

and I could be wrong on this and my memory is not always

as good, Mr. Williams, as yours, but I could be wrong, I

don’t believe we changed the entire zoning of our system.

Perhaps it is true and if our superintendent said we did,

we did, because he is much more acquainted with it than

we are.

Q. I am sure you all did rezone and put them—you had

a dual set of zoning system before. You had a Negro zone

—57—

and a white zone. A. Right.

Q. And isn’t it true that in 1960 pursuant to an order

of the Court that Mr. Marable, your child supervisor, made

a survey and rezoned the whole system from a dual zone

to a single zone? A. As it applied to the grades we were

going to desegregate.

Q. Of course, this was as it applied—you mean to tell

me he has been getting up a zoning map each year? A.

No.

Q. So this applied to the entire school system, didn’t it,

Dr. Burkhart? A. Yes, I think it did apply. I think it did

apply to the entire school to be effective as the desegrega

tion process increased.

Q. But the zone was established and done in just a

month or so. What you are talking about is maybe as each

additional grade is desegregated you would have a few

more teachers involved in the situation; that is what you

are talking about? A. And considerably more students.

Q. And a few more students involved. As a matter

of fact, under your transfer plan you haven’t had very

—58—

many students involved, have you? A. No, sir.

Dr. John 11. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

34a

Q. About sixty eligible out of some twenty thousand stu

dents the first year, didn’t you, in the first grade? A. I

don’t remember the exact number.

Q. But out of some twenty-two thousand students there

was about that amount, you had about sixty something

eligible and about twenty something of the Negro children

were in four or five or six white schools and that was the

extent, just about the total extent of desegregation here

today; that is true, isn’t it, is it not? A. As I say, I

am not acquainted enough to remember the numbers.

Q. Dr. Burkhart, are you here telling the Court that in

exercising some policy and administrative judgment as

a Board member you couldn’t even recall enough about

it to tell the Court about how many Negro children were

involved in desegregation last year? A. What I am trying

to say, Mr. Williams, and I don’t remember these figures

and I ’m sorry that I don’t, what I am trying to say is

every time the Board acts on a matter we are apprised

of statistics. It considers the statistics and it renders its

collective judgment on those and other matters which it

brings into consideration, but then the members of the

- 5 9 -

Board of Education, as public people, there are other ac

tivities and you cannot keep these figures in your head

and you are not aware of them as are your administrative

personnel or the administrative staff.

They are on file in my office and when the need arises

I refer to them, but when I am subpoenaed to come into

this court with two days notice and ask to testify as to

certain statistics that applied in 1960, I have no way of

pulling it out of my head.

Q. I am now asking you about statistics that you are

telling the Court that you based your judgment on last

fall, just this past fall. A. Well, that is—

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

35a

Q. 1962, just a few months ago, and also just recently,

and you are telling the Court—when was this amendment,

in March—you are telling the Court in Mareh you exer

cised a policy judgment that two more years was fast

enough. You can remember last month, can’t you? A. Yes,

I can remember some things last month but there are figures

I can’t remember as of yesterday and without any at

tempt to be disrespectful to either you or this Court, I would

like to point out that you have at your disposal figures

which you refer to constantly and I have nothing to refer to.

—60—

Q. I won’t get into that. I will simply ask you this,

Dr. Burkhart, maybe we can cut this short.

Then in short your testimony is that you exercised a

judgment last fall and last month regarding the addition

of these grades, and based on some figures that you don’t

have and you don’t have any idea what they consisted of?

A. Not a good enough idea to testify under oath.

Q. And, as a matter of fact, your basic two reasons—

when I say “you”, I am referring to the Board—that the

Board is here asking the Court to approve this six year

desegregation is because you felt there would be an up

heaval of the administrative procedure consisting of hav

ing to involve a few more teachers in the administrative

process, teachers and children, and that there might be some

segregationist community activity which might not be in

the interest of the children—those are the two reasons for

opposing this plan? A. That is right, and I included in

that, I believe the statement that any of these things can

interfere with the orderly educational process of our

children and we are trying to protect them from that.

Q. But you haven’t had that to happen in Knoxville?

—61—

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

A. Not yet; no, sir.

36a

Q. And if it were to happen yon still have a police force

in Knoxville, do you not, sir? A. Yes, sir.

Q. I believe you have testified previously that you felt

that the police force of Knoxville could handle any prob

lem that might arise with respect to violation of law; is

that correct? A. Ultimately—

Q. I have been reading the paper about the activities

of your police force. A. Ultimately they could handle it;

yes, sir.

Q. Are you sure there are some facilities for handicapped

children where Negroes are concerned? A. Well, I am sure

there are facilities for handicapped children.

Q. There are not at all, are there? A. Yes. We have

EMR, classes and SMR for Negroes.

Q. That is a different form of handicapped child? A.

No, they are handicapped because we have facilities for

the blind, for the hard of hearing, for the—

Q. Are they considered as educatable mentally retarded

- 6 2 -

children? A. They are considered as handicapped.

Q. So that educatable mentally retarded is a little dif

ferent from handicapped, isn’t it? A. No, sir. It is all

public education.

Q. Isn’t this what the Van Gilder School is about, for

the education of handicapjjed children as opposed to edu

catable mentally retarded children? A. No. It is for a

type of handicapped but, of course, mentally retardation is

a handicap.

Q. Well, we understand that but the Van Gilder School

is provided for the education of physically handicapped

children, is it not? A. No, sir.

Q. It is mentally handicapped? A. Mentally handi

capped.

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

37a

Q. What is your distinction between what they get at

the Van Gilder Occupational School and the other classes,

would you tell me, sir, classes for educatable mentally re

tarded? A. Well, I will try. The educatable mentally re

tarded are children in the lower grades who are slow in

their learning process and who need to be given extra time

and special teaching and special guidance in helding them

learn the courses.

- 6 3 -

Now those at Van Gilder are in the junior high school

grades who have I.Q.’s below an established level, and I

have forgotten again. This is a figure that I can’t remem

ber but I believe it is 80, below that level—who can be

given some training in some of the vocational activities, very

low grade type of thing. Making little plastic things and a

little weaving, and so forth.

Q. Well, Dr. Burkhart, isn’t it true Negro children in

your present state of affairs need that type training more

than white children if you are going to look at them as a

class? A. You mean be more of them with an I.Q. below

80 than the white children?

Q. That is what your superintendent testified at the last

trial, isn’t that correct? A. It is correct.

Q. If you provide this training for a racial group which,

according to your figures has less need for it, and you are

citing the deficiency of this second group which has more

need for it as a reason for not allowing them to receive

the training, sir, isn’t that true? A. As I stated earlier

this program has been, is an experimental program to see

if it would be advisable to continue with the program and

to expand it from time to time.

—64—

I just pointed out it has been crowded and there are

applicants of both races, I am sure, although I cannot docu

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

38a

ment an application from any individual person, which can

not be filled because of the crowded conditions at Van Gilder.

Q. How long has this school been in existence? A. I

believe three years but that could be plus or minus one

or two years.

Q. Your present plan is to discontinue it or not? A. No,

this plan, this program is subject to the provision of the

funds for it every time it is on the program. This is more

or less if funds are available.

Q. But it is going at the present? A. It is going at

present.

Q. And then only white children are in it and it is not

proposed to let any Negro children in until the grades are

reached in accordance with whatever plan is approved here

today? A. That is correct.

By the Court:

Q. Now, I am not quite clear, only white children are—

I understood you to say first that you did not have any

program for gifted children. A. Yes, sir.

—65—

Q. Now I understood you to say second that you did

have an experimental program for handicapped children,

mentally and physically retarded children, and that that

program was handled just exactly like the Van Gilder

handled it for the other school children. That is to say,

it was integrated up to the sixth grade, or would be in

tegrated up to the sixth grade and segregated from the

sixth grade on. Am I correct in that? A. Yes, sir.

Q. All right, then, what was that statement about the

other, that last? A. It is a program that is called the Van

Gilder Occupational Training Center just for the seventh,

eighth and ninth grade children. This is an experimental

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

39a

program which was originally financed for us mostly by the

federal government and has been kept on through other

funds, and this is the seventh, eighth and ninth grades and

it is segregated.

Q. That is for what, handicapped children? A. For

handicapped in the sense they are of low intelligence quo

tient.

The Court: All right.

By Mr. Williams:

Q. Dr. Burkhart, when you say segregated, you don’t

mean to imply that you got a comparable Negro school.

—66—

This is the only school of this kind, isn’t it? A. Of course,

that is right.

Q. You are providing nothing like this for the Negro

children with low I.Q. which the superintendent was talking

about on the trial of the case? A. That is correct.

The Court: That has been in operation three

years ?

The Witness: I believe three years.

The Court: All right.

The Witness: About.

By Mr. Williams:

Q. Now, Dr. Burkhart, you gave as your reason on

direct examination, you were talking about experience, that

experience indicated, that you based your approval of only

two additional grades this year on the fact you were

still in a transitional period and we are deciding how much

transition is required, and that something about experience,

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

40a

as experience indicates that you felt that two years was as

fast as you could go with propriety.

What experience are you talking about; what do you mean

by that? A. The experience that we got along well with

one year and again one year, and we felt like that doubling

the speed about as fast as anyone would go on this at this

- 6 7 -

particular time.

In other words, if you double your speed you are increas

ing it considerably, and our experience was that that would

be fast enough to go.

Q. You did not double your speed last September, did

you? A. Well, we added one—if you are saying that we

only went through the fourth grade instead of three, that is

really not doubling but we doubled the speed at which we

ordinarily do it.

Q. You mean you are doubling your rate of speed? A.

Yes.

Q. You did not double the rate of speed this year? A.

No.

Q. You left things as they were. Now let me ask you, you

presently have nothing in this plan to indicate how you in

tend to proceed after this, do you? A. No, sir.

Q. So that you are doing the same thing that the Nash

ville School Board did in 1957 which was rejected by the

Court, and you asked this Court to approve six years de

segregation and then let you decide later on how fast to

desegregate the rest of the school system, that is correct,

— 68—

isn’t it? A. I suppose. We haven’t made any provision

about past this time.

Q. So that you could conceivably under this plan, when

you got to the sixth grade you could stop and you could

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

41a

conceivably decide to wait four years before yon got to the

next grade, couldn’t you? A. I don’t believe we could

wait four years.

Q. But you might decide to wait two years before you

went on to the—even to the junior high school, mightn’t you?

A. We could. Under this plan we could.

Q. And under this plan you could, and as a matter of fact,

carrying it on out, you could conceivably wait five years,

couldn’t you? A. No.

Q. There is nothing in the plan that says you can’t. A.

Under the present system we have to go a grade-a-year.

Q. Under the present plan you have to go a grade-a-year?

A. Doesn’t it?

Q. No, the only, the amended plan which you have sub

mitted here, your amended plan says we are going to the

—6 9 -

sixth grade as of September. A. The original plan was a

grade-a-year plan.

Q. And you consider the original plan as still in effect

except for this amendment as to the rate of speed; is that

correct? A. Yes. Whether the amendment adds to the

original plan, I don’t know.

Q. So what you are now proposing is to go to the sixth

grade as of September 1963 and then a grade-a-year there

after? A. No.

Q. You still want to go a grade-a-year—what are you

proposing to the Court? A. What we are proposing is

that we can act—we are bound, we feel, to act under the

provisions of the grade-a-year plan. That is the absolute

minimum. We cannot go back past that but by amending

this we can pick up these two grades this fall.

We can at any time we feel in our judgment it is proper

to do so desegregate future grades with any rapidity that it

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

42a

is our judgment is proper providing we do not become

slower than the plan that we must operate under, which

is the grade-a-year.

Q. Dr. Burkhart, did you construe this plan as having

that same feature in it when you first proposed to the

—70—

Court that you could speed up at any time? A. The one

grade-a-year ?

Q. Yes. A. Yes, sir.

Q. As a matter of fact, that was one of the advantages

the superintendent gave; that is true, isn’t it? A. That is

right.

Q. Well, why is it, and let me ask you, the plan went into

effect in the year, September 1960, you desegregated the

first grade; that is correct, is it not? A. Right.

Q. You desegregated only the second grade in September,

1961; correct? A. Right.

Q. You had no plans whatever for desegregating any

other than the third grade in 1962 before the Sixth Cir

cuit mandate came down, did you? A. We had taken no

action but we had discussed it many times.

Q. Well, why hadn’t you discussed it before the first

year, to determine that between the first and second years,

you said you wanted some experience, didn’t you get some

experience the first year? A. Very little.

Q. Didn’t have enough judgment? A. That’s right.

—71—

Q. That enabled you to keep the white schools white

and the Negro schools Negro and it wasn’t very harmful

and provided in your sound judgment that good experience,

didn’t it? A. No, sir.

Q. Then you didn’t want or need experience, so then I go

back and ask you why you did not decide to speed up de

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

43a

segregation a little more and get some experience so yon

could afford these children their constitutional rights! A.

Well, I thought I had answered it but I will try again.

We felt after the end of the school year that we should

proceed along the lines that we had originally stated there,

a grade-a-year, proceed with one more, give us more ex

perience, more opportunity to experience what will happen.

There were schools that became involved in this second

year, I believe there were, and I could be wrong on that, this

again is a matter of memory—but we did involve more

schools and more problems and more parents in the second

year than we did the first, and that, we felt, gave us ex

perience to justify our action to speed up the plan in the

following year, and this year it seemed that we had had

enough experience to do the same thing and it seemed

— 72—

to be a logical place to separate this at the end of the

sixth grade for the purpose of getting it into a package

and observing that before we proceed into the higher grades

where if any difficulty is going to occur we can—

Q. Getting back a bit, you say you hadn’t even considered

speeding up between the first and second years. You said

you had not taken any action before the Supreme Court

mandate came down. Now you were implying maybe you

had considered it, is that true! A. Yes.

Q. Well, why didn’t you—did you tell your lawyer to

go up to Cincinnati and fight like everything to get the

twelve year, grade-a-year approved, why didn’t you let him

tell the Court you were considering, right now considering

desegregating two more grades and twm more the following

year! A. Well, I don’t recall that the Board gave our at

torney any instructions as to how to proceed in that par

ticular at the moment. He proceeds as our attorney. We

act with his advice.

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

44a

Q. Let me ask you this, are the plaintiffs here engaged

in a lawsuit against your attorney or against you, against

the School Board? A. It must be against me, or our

Board, I would say.

—73—

Q. The School Board knew that its attorney was down

here trying to get the Court to approve a twelve year grade-

a-year plan, didn’t it? A. Yes, but before I answer that

may I ask your Honor if I can request the Marshal to call

my office and ask that my patients be dismissed because ob

viously I am not going to get away soon.

Q. I am not going to be much longer with Dr. Burkhart.

I promise. I wouldn’t want to keep you from your patients.

I won’t be more than two minutes longer. That is two law

yer’s minutes, however. A. Would you restate your ques

tion?

Q. The Board knew, did it not, Dr. Burkhart, that their

attorney was trying or resisting the appeal of the plaintiffs

from the twelve year plan? A. Yes, our Board has been—

Mr. Fowler has kept us acquainted, of course, with the argu

ments and the positions that he has been taking before

all the Courts.

Q. And the Board did not at any time give him instruc

tions to say to the Court we are willing to speed up? A. I,

don’t recall that we did in particular.

Q. And, as a matter of fact, you don’t even know any

thing about this alleged experience that you are talking

about that you had the first year, the second year, except

—74—

that it was not enough really to give you a good basis for

solving any administrative problems in desegregation? A.

I know considerably more about the experience than that.

Q. Now with regard to your junior high schools and

Dr. John II. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

45a

the senior high schools. The longer you delay some kind

of desegregation then the longer you delay in getting the

experience to help you to solve the problems there; that is

true, isn’t it? A. The longer you delay that the longer you

delay your experience, but the good you have experienced in

the lower grades and the more you give the people an op

portunity to become accustomed to this, you should have

less difficulty as you get into the higher grades, is our

opinion.

Q. As a matter of fact, that is predicated on your proposi

tion, your original proposition, you started all children

together and let them start out on a desegregated basis and

leave the other children segregated the way they were;

is that right? A. Yes, but we have gotten away from that,

of course.

Q. You have gotten away from that and you haven’t

had any problems, have you? A. No, sir.

—175—

Q. Under your transfer plan which keeps practically

complete segregation anyway, so why should there be any

more problems in the junior high school or high school?

A. Because we are dealing with older children.

Q. Well, what experience do you have that substantiates

that proposition in desegregating older Negro and white

children? A. No experience in Knoxville.

Q. You haven’t considered any, the Delaware plan which

says that you should desegregate immediately, have you;

you are not considering the Delaware plan? A. No, sir.

Q. The reason for that is, you say Knoxville is a pecu

liar place and the Board has got to have experience, that

is what you have told the Court, isn’t it? A. We think ex

perience is very helpful and also our observation of what

has happened in other communities, in our neighborhood,

and that has influenced our decision.

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

46a

Q. You are saying to the Court we want experience, we

don’t care that they desegregated peacefully in Louisville,

St. Louis, Washington, and everywhere else, we want to

have our own experience here, and yet you want to ask

the Court at the same time to delay these children and keep

you from getting the very experience you say you want?

—76—

A. We think there is a considerable difference between

what happened in Washington and what happens in Knox

ville.

Q. You know, I am sorry I mentioned that. I knew you

would enjoy that.

What I am asking you about is about this experience

thing. If you would answer that question, please, sir. A.

About do I think the experience here in Knoxville is what

we are interested in?

Q. Yes. Isn’t that the basic reason that you say to the

Court we need time because Knoxville is a peculiar situa

tion, the Louisville experience isn’t good enough for Knox

ville? A. Yes.

Q. All right. So you have asked for experience. Doesn’t

it follow that you are not trying to get the experience that

you are telling the Court one needs, and wouldn’t you get

it better if you desegregated, if you desegregated the

junior high schools and the high schools along with the

grade schools or at least some portion of them? A. No,

we don’t think so.

Q. You would get it sooner, wouldn’t you? A. You could

—77—-

get experience but maybe not the kind of experience we

are interested in.

Q. Well, how do you know what kind of experience you

are going to get until you have some desegregation? A.

Hr. Williams, if we had desegregated the twelve grades

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

47a

simultaneously, we would have experience, a tremendous

amount of it.

Q. And soon. One of your plans, alternative plans sug

gested by you or your staff suggested that, didn’t it! A.

Yes, sir. But that experience would not have given us any

help in trying to decide how to go ahead because the ex

perience would not have been fruitful.

Q. What experience have been fruitful with respect to

the desegregation you have had! A. Each year we in

crease the grades that are desegregated. We change the

age in which there is a relationship in the school room be

tween colored and white. We are getting closer to the age

where we think the situation might become difficult, getting

closer to it.

Q. Based on what! A. Based on what!

Q. Yes, you have never had any experience in that re

gard. A. We read the newspapers and listen—

— 78—

Q. Did you hear about New Orleans where they had a

big riot and boycott down there about some two or three

year old children, five and six year old children; did

you read that! A. Yes.

Q. Aren’t you here before the Court proposing to the

Court that experience in one area is not similar here in

Knoxville! A. No, because that experience in the far dis

tant areas—New Orleans is extremely different from Knox

ville. Knoxville is extremely different from Washington

and St. Louis.

Q. Louisville is an extremely distant area! A. Louis

ville is more distant than Nashville and Clinton.

Q. Nashville is a fairly close area! A. Yes.

Q. Humphreys County is 70 miles from Nashville, Wil

son County is 30 miles from Nashville, between here and

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

48a

Nashville, they desegregated the entire school system there

in one year, about two years ago under Court order; you

haven’t considered that experience at all? A. No, sir.

Q. When you boil it right down you just don’t want to

move that fast and cannot present the Court with a single

- 7 9 -

factor which it should take cognizance of to support that,

can you? A. Well, you are asking me in one word to de

feat our case.

Q. Well, I want you to tell me the truth, if it defeats a

man’s case if he tells the truth, then I say he should be

willing to have his case defeated. A. I am trying to tell

the truth, if you will word your question a little differently.

Q. If the question is answered no, it is answered no; if

the answer is yes, it is yes. I am simply asking.

Well, maybe it would be better to have the eourt re

porter read the question.

Mr. Fowler: May it please the Court, counsel is

arguing a tremendous amount.

The Court: I went into that question in detail

the other time in the hearing, and if you answered it

then we will go to something else.

Mr. Williams: That is all, Dr. Burkhart.

(Witness excused.)

The Court: Take a short recess, gentlemen.

(A short recess was had, after which the following

proceedings were had.)

Dr. John H. Burkhart—for Defendant—Cross

49a

Thomas N. Johnston—for Defendant—Direct

—SO—

T homas N. J ohnston, called as a witness by and on be

half of the defendant, a fte r having been first duly sworn,

was examined and testified as follow s:

Direct Examination by Mr. Fowler:

Q. You are Mr. Thomas Johnston? A. Yes, sir.

Q. You are the same person that was superintendent of

schools of the City of Knoxville in the previous hearing we

have had in this case? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you have been superintendent since when? A.

Since July, 1955.

Q. Mr. Johnston, this morning, as you know, we are re

viewing the facts which have led the Board of Education to

make its decision in this desegregation problem.

Can you summarize for us the facts which were pertinent

in the first examination of this matter here in this court

which lead you to adopt the original one grade-a-year plan,

and in your own words, if you like, tell us the relevancy, if

any, between those reasons then existing and your actions

later where you adopted two grades-a-year as a plan.

—81—

What I am trying to do is shorten the hearing, Mr. John

ston. A. Back in the summer of 1955 and for quite a time

after that, the Board of Education discussed what might

be an appropriate plan to comply with the Cii’cuit Court

ruling.

Over the years they discussed many plans but, as I re

call, it was our Board, and they have changed a little bit

since 1955, since I have been superintendent and I have

never noticed or known of a single Board member whoever

said that we want to work out a plan by which we can

circumvent or not comply with this ruling but, rather, al

50a

ways what would be the best way to comply and at the

same time maintain an orderly educational program for

both the white children and the Negro children and not

create tension and emotional upsets and disturbances in

the community.

Mr. Williams: May it please the Court, we dislike

to interrupt Mr. Johnston but we will say to the

Court, the Court’s ruling was that we will not go into

those matters.

The Court: You are right, but the great trouble

with that, you are going into it on your cross exam

ination and I can’t let you go into it and cut it off.

—82—

You are exactly right, that is what I held. I went

over this ground thoroughly, at least I thought I did,

and if you will just put it in a thumbnail sketch, Mr.

Johnston, because you testified in detail at these

other hearings, did you not?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: And I undertook to analyze your tes

timony, did I not, in that other opinion?

The Witness: Yes.

The Court: I am familiar with it and I would

cut you off, Mr. Johnston, but since he has gone

into it with the other witness on cross examination,

I don’t think it would be fair.

Mr. Fowler: I am perfectly willing to be cut off

but as counsel pointed out, the burden, theoretically

at least, is upon the School Board.

The Court: That is right. He may answer. Go

ahead.

Thomas N. Johnston—for Defendant—Direct

51a

A. (Continuing) Well, to make it short, at long last the

Board of Education decided to put into effect the grade-a-

year plan and they did so on my recommendation, and I gave

them some six or seven reasons in support of this plan

and all of that is a matter of record.

I thought of all the plans that we had analyzed and dis-

—83—

cussed that that would be the best, and we could profit by

the experience year to year starting with the first grade.