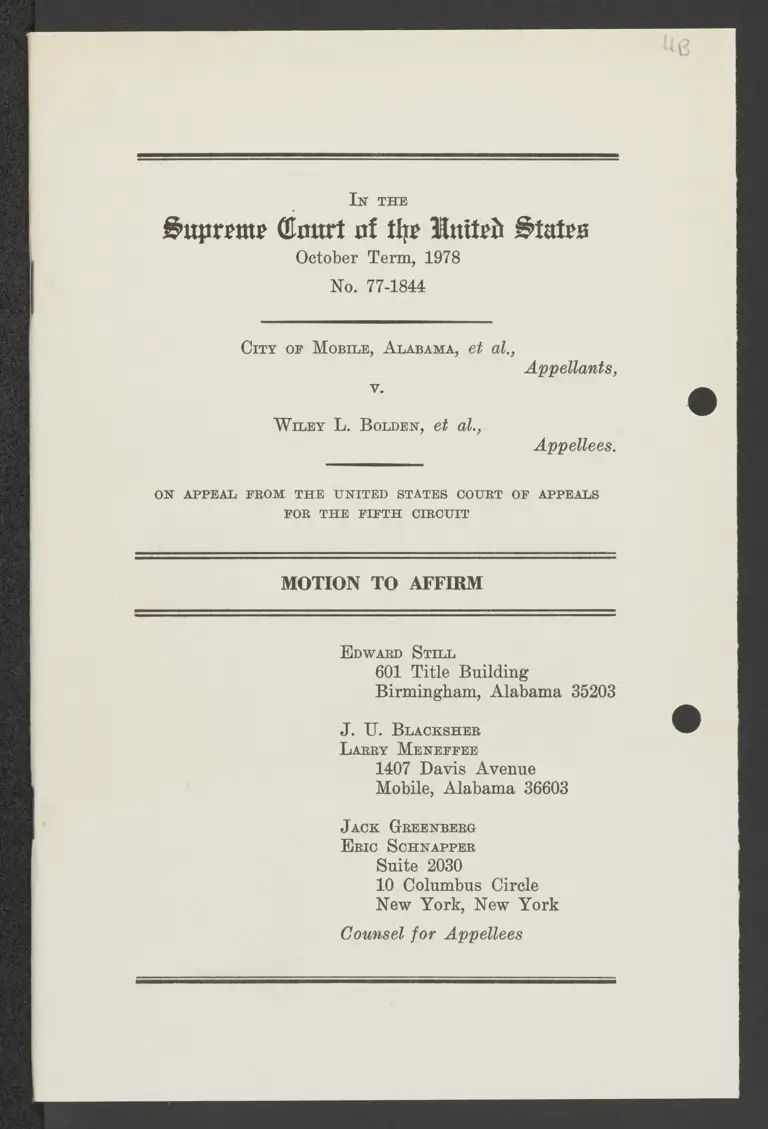

Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

July 3, 1978

29 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Motion to Affirm, 1978. 2b5a8976-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/58d0d15b-075c-49c3-8d85-2d933134ad71/motion-to-affirm. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1978

No. 77-1844

City or MoBILE, ALABAMA, ef al.,

Appellants,

Vv.

Wey L. BoLpEN, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MOTION TO AFFIRM

Epwarp STILL

601 Title Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

J. U. BLACKSHER

Larry MENEFFEE

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

JACK GREENBERG

Eric ScHENAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Counsel for Appellees

INDEX

PAGE

QUESTIONS: PRESENTED ook caidiins veo vnminns 1

STATEMENT ... ose 800020. 080i sts wii 2

1. The Long History of Voting

Discrimination Against Blacks

In Mobile. i, ooo edisieanest 2

2. The Present Denial of Effective

Participation In The Political

{gor ORO LR Cols EOE OE en RE 5

3. Unresponsiveness of Elected

Officials To Black Community

IRECTESES oo nvinnc mis cis ne sins 6

ARGUMENT . cov oss vinnssnnasiiansiioriveds 8

CONCLUSION vv: cs iiinviisioiniois « a vie sisiansin sin whe s 20

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252

(VT77) vise iins sn tiaisnc ssn senins 9.11.12

Bradas v. Rapides Parish Police Jury,

508 F.24 1109.(5¢h Cir. .1975) .J. 16

Blacks United for Lasting Leadership,

Inc v. City of-Shreveport, 571

F.2d 248 (5th Ciy. 1978) ..... 0. 12,15

INDEX

PAGE

Davis v. Schnell, 81 P.Supp. 372

(SD. Ala, OAR) os asa an 3

Ferguson v. Win Parish Police

Jury. 528 ¥.24 -592 (5th Cir.

1976)... oii chia ss sh aha eh aus 16

Gomillion 'v, Lightfoot, 364: U.5. 339

£19603... uoredinvieveds ao, I... 9

Graves Mfg. Co. v. Linde Co., 336 U.S.

270196). 0. i, Se SER BE He ie 9

‘Howard v. Adams County Board of

Supervisors, 453 F.2d 455

(Sth Cir A972): .. .. f.avddi li... 16

Kendricks v. Walder, 527 F.2d4 44

(7th Clr. 1975). ...00cviivnsoioses 11

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554

7.24 1239 (5th Cir. 1977)........... 16

Moore v. Leflore County Board of

Election Commissioners, 502

F.2d 62% (5th Civ. 1974)...... .... 16

Nevett iv. Sides, 571 F.2d 209 :(5th

Cir. 1978)... ..:.. 0.5... sama. oo; 12,15

Panior v. Iberville Parish School

Bd., 536 F.2d 101 {5th Cir.

1976). .:2. 03. .0: 0.400). Jd. 00. 0. 16

INDEX

PAGE

Robinson v. Commissioners Court,

505 F.2d 674 (5th-Cir.

1974) ove cininte nin vinintainonets afk wih oe ahs +tncess 16

Smith v. Allright, 321 U.S. 649

LA944) oo vrs cis omnia bisa nia soni 3

Thomasville Branch of the N.A.A.C.P.

v, Thomas County, 571 F.2d

257 (5th Cir, 1978). .......: S000, 16

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229

(IG78Y se tivcne i cine iis esses snes 16

White v. Resester, 412 U.S. 755

(1973) 2000 Ln aaa aa 1.8;

14,16

Wise v. Lipscomb, 46 U.S.L.W. 4777

C1978) oct ssc niin sein ia cin vino 17

~ 3i1 ~-

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1978

No. 77 -1844

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

WILEY 1. BOLDEN, et al.,

Appellees.

—— ———— ———————————————— ————— ——— —————

On Appeal From The United States Court of

Appeals For the Fifth Circuit

MOTION TO AFFIRM

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

i. Were the concurrent factual findings

of the courts below, that Mobile's at-large

election plan is maintained for the purpose of

discriminating against black voters; clearly

erroneous?

2. Should the decision of the Court

of Appeals be affirmed on the alternative

ground--considered but not relied on by a

majority of the Fifth Circuit panel-—-that

Mobile's at-large election plan had the effect

of disenfranchising black voters in violation of

White v,. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)?

3. Did the District Court err in adopting

its own plan where the appellants refused to

propose any remedial plans and where the Dis-

trict Court injunction expressly permits state

and local officials to modify that court plan?

STATEMENT

Black citizens of Mobile, Alabama, brought

this action in June, 1975, challenging the

at-large system of electing members of the

Mobile City Commission. Following a 6 day

trial, in which 37 witnesses testified and 153

documentary exhibits were introduced, and

following a half-day tour of the city by the

District Judge, the trial court determined that

the at-large elections were being used purpose-

fully and invidiously to discriminate against

black voters. The salient findings of fact,

affirmed in all respects by the Court of Appeals

are as follows:

1. The Long History Of Voting Discrimination

Against Blacks in Mobile

The '"Redemption' of Alabama by the Bourbon

Democrats from Federal Reconstruction policies

culminated with the enactment of various so-

called Progressive reforms. In Alabama, the

Progressive movement included disfranchisment of

blacks because they were considered a corrupting

influence. The 1901 Albama Constitutional

Convention was called for the primary purpose

of disenfranchising blacks. The cumulative poll

tax and grandfather clause were the primary

devices used to accomplish this. Delegates from

Mobile led the efforts to remove blacks from

politics in 1901, and some of these same white

Mobilians promoted the adoption of an at-large

elected city commission for Mobile in 1911.

Only token numbers of blacks were allowed to

register and vote until passage of the Voting

Rights Act of=1965. 3.84, pp. 219b=20b,;: 29.

Alabama operated an all-white Democratic primary

until well after it was outlawed by this Court

in “Smith v. Allright, 321 0.8..649. L1944)...4A

white state legislator from Mobile was chiefly

responsible for the enactment of interpretation

tests as a device to prevent blacks from voting

after the white primary was struck down. The

interpretation tests were declared unconstitu-

tional by the federal court in Mobile. Davis

v, Schnell, ‘81 F.Supp. 872 {8.D. Ala. 1948),

aff'd £336:0.9.:933:(1949),

In 1974, the Mobile County legislative

delegation sponsored a special law to enable

Mobile to change to a Mayor-Council form of

government after a referendum election. A

former State Senator from Mobile who partici-

pated in the law's passage testified that the

local delegation chose to provide for at-large

election of the proposed council, rather than

single-member districts, because of racial

cond iderBiibns:

Q. Why was the opposition to

single-member districts so strong?

A. At that time, the reason

argued in the legislative delega-

tion, very simply was this, that if

you do that, then the public is going

to come out and say that the Mobile

Legislative Delegation has just

passed a bill that would put blacks

in City office. Which it would have

done had the City voters adopted the

Mayor-Council form of govenment.

The District Court found, as a matter of

fact, that "[t]hese factors prevented any effec-

tive redistricting which would result in any

benefit to the black voters passing until the

State was redistricted by a Federal Court order."

J.S., p. 30h,

- 5 =

2. The Present Denial Of Effective

Participation In The Political Process

In the opinion of the court below, the

total absence of black elected officials

in Mobile was Ylolnly one! indication that

local political processes are not equally open

[to blacks). 3.8, °p. 7b. The District Judge

also relied upon evidence presenting a thorough

analysis of racial politics in Mobile.

Expert statisticians and political scien-

tists analyzed most of the local elections

in ‘the city tana county over the ‘past 15

years. The unsuccessful candicacies of 4

black citizens who sought school board seats, 3

blacks who ran for city commission and 23 black

candidates for at-large legislative seats

were thoroughly explored, as were the racial

campaign tactics used to stir up white backlash

and defeat several white candidates who dared

to espouse some interests of the black community.

1/ The City of Mobile contains approximately

two-thirds of the population of Mobile County.

The District Court considered the election

experiences of black candidates in county-wide

races to be relevant as well as to an analysis

of icity politics, J.5., pp. ob=10b, 13b, n.7.

While most white candidates actively seek black

votes as well as white votes, there was uniform

agreement among the experts and politicians that

to be successful a candidate must be careful not

to be tagged with the "bloc [black] vote," which

was tantamount to the "kiss of death," according

to the City's own expert political scientist.

All of the witnesses (except one defendant city

commissioner) agreed that it would be difficult

if not possible for a black candidate to over-

come the solid racially polarized voting pat-

terns in Mobile and win an at-large election.

Most of the prominent leaders and politicians in

the black community testified at trial, and

without exception they agreed that the futility

of the effort prevented them from even con-

sidering running for the city commission under

the at-large system. The District’ Court ‘ac-

cepted the opinion of plaintiffs' expert politi-

cal scientist that black voting strength is

"basically cancelled or negated in the at-large

structure in the Mobile City elections."

3. Unresponsiveness Of Elected Officials

To Black Community Interests

Much of the long trial was devoted to

evidence of how unfairly Mobile's all-white

government has treated black citizens. The

District Court found that "[t]he at-large elected

city commissioners have not been responsive to

the: minorities" meeds.J.8., p. 11B." To support

this finding, the court's opinion refers first to

continuing racial discrimination by the city in

employment. The court still monitors compliance

with its earlier decree ordering desegregation of

the Mobile Police Department. Id. Other federal

court orders were required to desegregate public

facilities in the City of Mobile. 3.8 p. 120.

Blacks have been appointed to important govern-

mental boards and committees in only token

numbers. J.S., pp. .12B=14b. : Black residential

areas have suffered inequitable neglect with

respect to such vital services as drainage

control, paving and resurfacing streets and the

placement of sidewalks. J.5., DBs 4307171).

Perhaps most importantly, the court found

that city commissioners have been insensitive

to long-standing complaints of police brutality

directed against blacks and the continuing

recurrence of cross burnings. In particular,

the trial judge was critical of the "timid and

slow reaction" of city government in investigat-

ing and disciplining seven white Mobile police

officers who actually carried out a "mock lynch-

ing" of a black suspect on a downtown street

corner. It was confirmed finally that these

officers placed a rope around the suspect's neck,

threw it over a live oak branch, and pulled the

black man to his tiptoes. The court found that

the "sluggish and timid response" of elected city

officials to the lynching incident "is another

manifestation of the low priority given to the

needs of black citizens and of the political fear

of a white backlash vote when black citizens’

needs are at stake." J.S., p. 19b.

ARGUMENT

I. Notwithstanding appellants' extensive

discussion of the meaning and application of

the dilution rule of White v. Regester, 412

U.5.°755° (1973), ‘the decisions below rest, in the

first instance, not merely on the discriminatory

impact of the at-large election system, but on a

finding of fact that Mobile's system of electing

Commissioners is motivated by an unconstitu-

tional desire to discriminate against blacks.

J.8. Sipp. 12a, -30b." ‘This case thus presents

primarily an application of Gomillion v. Light-

foot; 7364 0.8, 339 (1960), and Arlington Heights

v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429

0.8:2252 (C1977).

The "district court made a finding of

discriminatory intent after an exhaustive

analysis of the evidence presented at a six day

trial’ J.8., pp. 2860-310. The court of

appeals carefully scrutinized the record and

concluded that the district judge's detailed

findings of fact were not clearly et totiedus and

that they compelled a finding of discriminatory

intent. J.S.,, p. "1223. "This Court does mot

ordinarily 'undertake to review concurrent

findings of fact by two courts below in the

absence of a very obvious and exceptional

showing of error." Graver Mfg. Co. v. Linde

Co.,: 336 U.8.:271, 275.(196]1), No such unusual

circumstances are present here.

The record contains ample evidence to

support the finding that discriminatory intent

lay behind the decision of the legislature to

maintain the at-large election of Commissioners

in Mobile. Until 1965 blacks were largely unable

to register in Mobile or elsewhere in Alabama,

and racial discrimination in voting had been the

announced state policy since at least 1901. The

district court found, based on the direct testi-

- 10 -

mony of several state legislators who partici-

pated in consideration of redistricting bills for

Mobile, that the legislature would not pass "any

effective redistricting which would result in any

benefit to black: voters.” . .J.S8., Pp. .30b... At~

large elections were found to effectively disen-

franchise blacks in Mobile because of a particu-

larly virulent hostility by white voters, who

have not only voted as a bloc against any black

candidate for any office in Mobile, but have also

repeatedly defeated white candicates who have

been notably responsive to black needs. J.S., p.

17b-10b.. After detailed analysis of all the

election returns, the district court considered

and rejected appellants’ contention at trial

that, just because blacks sometimes vote for

winners in elections. that are not racially

polarized, they wield an effective '"swing vote."

Against this background of historical

discrimination against black voters in Alabama,

and in light of a present legislative practice of

refusing to adopt redistricting measures that

might result in the election of blacks, the

courts below were entirely justified in conclud-

ing that the maintenance of at-large voting in

- 11 -

this particular case was racially motivated.

Arlington Heights v. Mewtropolitan Housing Corp.,

supra, 429 U.S. at 266-68. The lower courts did

not ignore appellants' assertion that the at-

large elections have been used for over half a

century because of corruption problems in 1911;

they merely made a factual determination that

that somewhat implausible explanation was not the

actual reason for maintaining the present method

of election.2/

Appellants suggest the courts below adopted

a rule of law that discriminatory intent must be

inferred whenever a legislature fails to adopt a

districting plan it knows is favorable to blacks.

J.8., PDP. 7, 24-26. "Appellants point ‘tono

language in either opinion adopting such a rule,

and none is to be found. On “the contrary, the

same panel of the Fifth Circuit which affirmed

a finding of discriminatory intent in this case

2 The decisions below express no preference

for single-member districts as opposed to

at-large elections from a political science

standpoint. Beyond the issue of racial discrimi-

nation, political commentators disagree whether

the purported greater "efficiency" of at-large

elected local governments can offset their high

price of political control by strong financial

interests and the loss of grass-roots input.

See Kendricks v. Walder, 527 F.2d 44, 51-54 (7th

Cir. 1975) (Pell, J., dissenting).

- 12 -

held in two companion cases that such intent had

not been adequately demonstrated, even though

both of those cases involved the same circum-

stances which appellants claim mandate a finding

of ‘intent under the Pifth Circuit's decisions.

Nevett v. Sides, i571 PF.24 209 (5th::Cir. +1978);

Blacks United for Lasting Leadership, Inc. v.

City of Shreveport, 571 F.2d 248 45th Cir. 1978).

Appellants argue that appellees were obligated

to establish not only that maintenance of the

at-large plan was motivated in part by a racial-

ly discriminatory purpose, but also that that

plan would not have resulted even absent that

unlawful purpose; the burden of proof as to the

latter issue, however, was clearly on appellants.

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp.,

429 .0.8..:252,.2709,: n.21 (1978). The decisions

below do: not sound the "death knell of the

Commission form of government' outside of Mobile,

and even there do not forbid the retention of

important aspects of the Commission system in

Mobiles)

3 The appellants are free, for example, to

establish a triumvirate of elected executive

officials and to permit a member of the single-

member district council to also run for and hold

such an executive position.

- 13 -

Neither did the decisions below adopt a

"tort" standard of intent, as claimed by appel-

Yantsindi Se, cppiicty 113, The district court did

hold "that the present dilution of black

Mobilians is a natural and foreseeable consequent

of the at-large system imposed in 1911," and

"that the evidence supports the tort standard as

advocated by the plaintiffs." J.S.," pp. 29p-30b.

But the opinion explicitly stated: "However,

this court prefers not to base its decision on

this theory," 3.8., pvp. '30b. Rather, the trial

judge based his finding of purposeful discrimina-

tion on direct evidence of the legislature's

racial ‘motives. J.S., pp. 29b-31b. The court of

appeals affirmed on this ground as well. J.S.,

P.'141.,

The courts below adopted no general rule

about the validity of at-large elections or the

Commission form of government, but merely

determined on the specific evidence before

them that respondents had established discrimina-

tory intent. Such a finding, as the disposition

of the companion cases shows, does not purport

to dictate the outcome of other litigation

regarding the use of at-large elections or the

Commission form of government, and affirmance by

this Court of that factual finding on the record

in this particular case will not establish any

new legal principle. Under these circumstances

the Court should adhere to the '"two court rule"

and decline to . review that factual finding.

2; Whether the diluting effect of

Mobile's at-large elections was sufficient by

itself to warrant relief under White v. Regester

is only an alternative ground for affirming the

decision below. In the court of appeals only one

judge, specially concurring, found liability on

that basis, and appellants do not purport to find

in his one-sentence concurring opinion a substan-

tial ground for: appeals - JuS., pv 7a. The

district court concluded that the at-large plan,

in addition to its unconstitutional purpose, also

had an unconstitutional impact. But itis: not

the practice of this Court to grant plenary

review to decide the conrrectness of independent

alternative grounds available to support other-

wise proper decisions.

Appellants assert that the court of appeals

adopted a number of inappropriate rules of laws,

but are able to point to no language in the

opinion below incorporating these alleged rules

= 15 y=

Appellants contend, for example, that the Fifth

Circuit in this case held "in effect" that the

existence of racially polarized voting was of

"controlling significance," yet concede that the

rule actually articulated by the same panel in a

companion case uses polarized voting ''merely as

the starting point for further constitutional

analysis? oJ.8. pid. Appellants claim the

court of appeals "effectively" required that

electoral systems be so structured as to guaran-

tee the election of minority candidates, J.S.,

pp. 6, 17, but in two companion cases the same

panel declined to order the use of single-member

districts which would have thus assisted minority

candidates. Appellants advance a number of

assertions regarding facts in this case relevent

to White, urging, for example, that blacks in

Mobile can participate in a meaningful way in the

political process and that the all-white govern-

ment there 1s fairly responsive to minority

needs, :J.8., pp. 7-8; the. findings of. the dis-

trict court, however, were to the contrary on

each of those issues, and those findings were

4/ Nevett 'v. Sides, S571'F.2d 209 (5th Cir.

1978); Blacks United for Lasting Leadership,

Inc. .v. City of Shreveport, 57) F.2d . 248 (53th

Cir.~1978).

- 16 -

not, and are not claimed to be, clearly erroneous.

The alternative ground available under

White v. Regester and noted by the concurring

opinion and the district court represents merely

a routine application of White v. Regester

as clarified "by "a longline of icarefully con-

SM sidered appellate decisions.=' Appellants did

not generally question in the court of appeals

the established Fifth Circuit law in this area

and did not assert that the principles of White

v. Regester should not be applied to city elec-

tions. Appellants did argue below that White v.

Regester had been modified by Washington v.

Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), and that an at-large

election plan which had the effect of disen-

5¢ Thomasville Branch of the N.A.A.C.P., v.

Thomas County, 571 F.2d 257 (5th Cir. 1973);

Kirksey.v., Broad of Supervisers, ..554 F.2d. 139

{5th Cir.), cert. denied, U.S.

(1977); ‘Panior v. Iberville Parish School Bd.,

536..F.2d 101 {5th Cir. 1976):. Ferguson,v. Winn

Parish Police Jury, 528 F.2d. 592 (5th Cir.

1976); Bradas v. Rapides Parish Police Jury, 508

F.24..1109..¢(5h, Cir... 1975); Robinson v. Commis—

sioners Court, 505 F.2d 674 (5th Cir. 1974);

Moore v. Leflore County Board of Election

Commigesioners, 502 7.24 621 (5th Cir. 1974):

Howard v. Adams County Board of Supervisors,

4537 .2d 455. (5th Cir.), cert denied 407:U.S. 925

(£1972).

-17 -

franchising blacks was nonetheless valid unless

motivated by a discriminatory purpose; on that

6/ issue, however, appellants prevailed —/ and they

do not seek review of that aspect of the deci-

sion below.

3. The Jurisdictional Statement contains

a question regarding the remedy fashioned by the

district court, and the history of that issue is

delineated, but the matter 1s not discussed at

length in the body of the Jurisdictional State-

ment. J.S.; "pp. 44 ,:15-16;

The appropriateness of the remedy was

properly analyzed by the court of appeals.

J.S.5° pp. 15a-17ai Appellants inexplicably

refused in “the "district court to offer any

plan for the conduct of elections or the crea-

tion of single-member districts. Under that

cicumstance it was the obligation "of the

federal court to devise and impose a reapportion-

ment plan." Wise v. Lipscomb, 46 U.S.L.W. 4777,

4779 (1978). Manifestly some alteration in

Mobile's method of election was required to

remedy the proven violation, and since the

6/ Appellants maintain that, for the reasons

stated in the concurring opinion of Judge Wisdom

in Nevett, the court of appeals decision was

erroneous in this regard. Were probable juris-

diction noted we would so argue.

- 18 -

plan was ordered by the district court it was

required to-prefer single-member districts. . 1d.

Appellants' recalcitrant refusal to assist in

the framing of a decree forced the district

court to resolve the details of a plan which it

would have preferred to leave to state or local

authorities; ifor this reason the court's idecree

expressly provides that state and local offi-.

cialsi‘vetain ‘their ‘authority ‘to alter the ‘plan

adopted by the court in any respect other than

the reinstitution of at-large seats. J.S.; pp.

24-34.

Appellants imply thdat'Pthe trial court

abused its discretion by formulating a "strong

mayor" plan (based on a synthesis of special

statutes governing Birmingham and Montgomery)

instead of utilizing the "weak mayor" option

offered by the general Alabama law. J Suis = Ps

15, inJd7. In: fact, ‘however, :ilt was at. .the

instance of appellants' counsel, who during and

after trial pleaded with the court not to employ

the "weak mayor" form as a remedy, that the

district judge appointed a blue-ribbon panel to

develop an interim "strong mayor" plan. Although y P

the Jurisdictional Statement suggests the district

- 19 -

judge altered Mobile's non-partisan method of

electing city official, "3.8., p. 22, n:26, in

fact the judge retained that practice. Js,

pp. 7d-9d. Appellants did not attack this

remedy in the court of appeals, except to argue

that no remedy was possible because at-large

elections are an integral part of commission

government. In any event, the appellants,

having failed in 1976 to offer the district

court any proposed remedial plan, cannot now

complain in this Court about the details of the

plan actually adopted.

- 20 -

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons the judgment of the

court of appeals should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

EDWARD STILL

601 Title Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

J.U. BLACKSHER

LARRY MENEFFEE

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

JACK GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Counsel for Appellees

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 3rd day of August,

1978, I served three copies of the Motion to Affirm on

counsel for appellants by depositing them in the United

States mall, first class postage prepaid, addressed to:

Charles S. Rhyne

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Suite 800

Washington, D.C. 20036.

I further certify that all parties reguired to be served

have been served.

\ \

£>

a PA fu 0 — fe i

Eric Schnapper

Counsel for Appellees

a

MEILEN PRESS INC —N. Y. C. Po 219