Mapp v. Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga, Tennessee Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mapp v. Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga, Tennessee Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1975. d85176fc-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/58e67559-11b1-4970-90ca-31ca46be04ae/mapp-v-board-of-education-of-the-city-of-chattanooga-tennessee-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

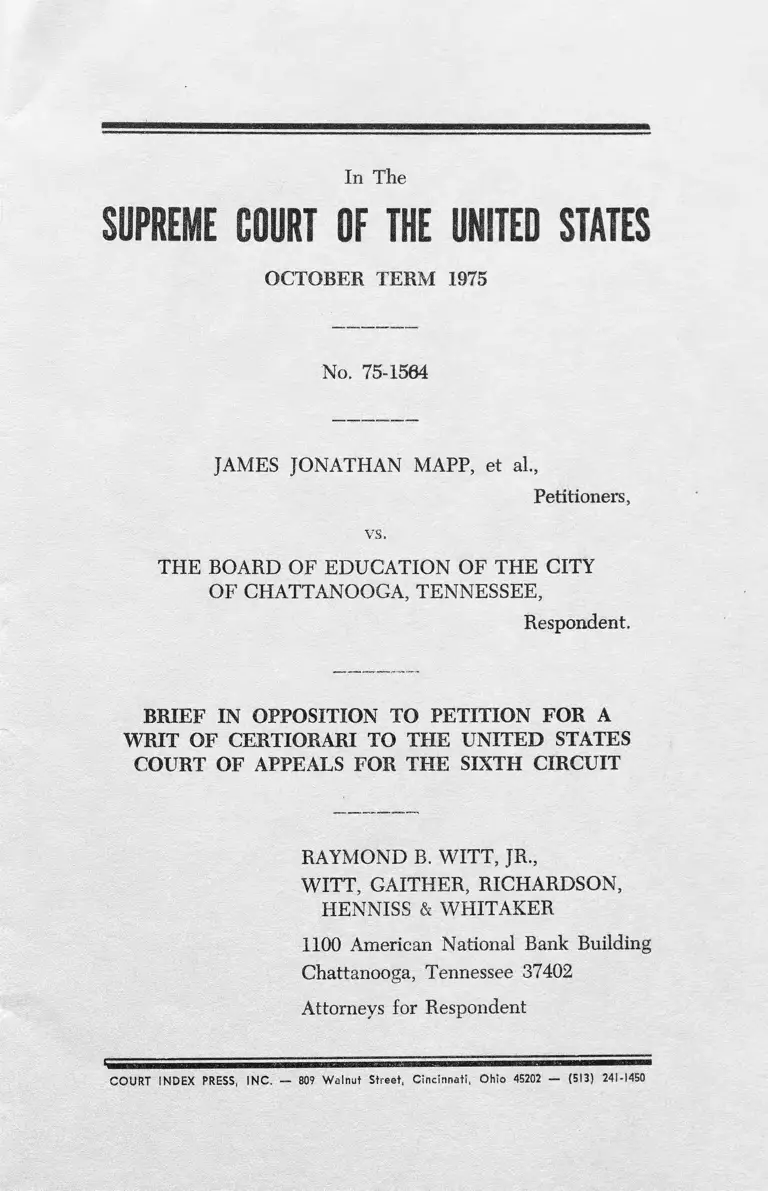

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM 1975

No. 75-1564

JAMES JONATHAN MAPP, et ah,

Petitioners,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY

OF CHATTANOOGA, TENNESSEE,

Respondent.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR A

WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

RAYMOND B. W ITT, JR.,

W ITT, GAITHER, RICHARDSON,

HENNISS & WHITAKER

1100 American National Bank Building

Chattanooga, Tennessee 37402

Attorneys for Respondent

COURT INDEX PRESS, INC. — 809 Walnut Street, Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 — (513) 241-1450

INDEX

Page

COUNTER STATEMENT OF THE QUESTIONS

PRESENTED ......................................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............................................... 3

The Action Under Review Here ......................................... 3

Factual Background ................................................................. 3

REASONS FOR DENYING THE W RIT ............................ 10

CONCLUSION .............................. 16

APPENDIX A: Decision of Court of Appeals dated

October 20, 1975 and Order of

January 27, 1976 .................................. la-19a

APPENDIX B; Book entitled “Chattanooga Public

Schools Chattanooga, Tennessee,

Attendance Zones Pupil Enrollment

Data, Part III, Summary Analysis

of Enrollment Experience, Black-

White Ratio Stability” ........................ 20a-27a

II.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka I,

374 U.S. 483 ................................................................... 3, 10, 11

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka II,

394 U.S. 295 .......................................................... 3, 10, 11, 15

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

Virginia, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ............................................. 11

Mapp v. Board of Education of Chattanooga,

329 F.Supp. 1374 .................................................

aff’d 477 F.2d 851 (6th Cir. 1973) ...................

cert, denied 414 U.S. 1022 (1 9 7 3 )...................

373 F.2d 75 (1967) ...........................................

366 F.Supp. 1257 (1 9 7 3 )....................................

Pasadena City Board of Education, et al v. Nancy

Anne Spangler, et al and United States of America,

44 U.S.L.W. 3271 ................................................................... 7, 8

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1 9 7 1 )................................ 4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 12, 15

Constitutional Provisions:

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution ............................................................................. 11

2, 5

2, 5

. 2

. 4

. 14

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM 1975

No. 75-1564

JAMES JONATHAN MAPP, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY

OF CHATTANOOGA, TENNESSEE,

Respondent.

BR IEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR A

W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Respondent accepts Petitioners’ statement of jurisdiction but

cannot accept their statement of tire question presented or

the statement of the case.

COUNTER STATEMENT OF THE

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The questions presented which were correctly resolved by

the District Court and the Appellate Court are whether a

formerly de jure dual school system is under a continuing

annual responsibility to assign its white children throughout

the school system in such a manner as to avoid having any

schools with a racial balance disproportionate to the system-

wide racial balance where such racial disproportion as may

then exist in the system “is not the result of any present

Of past discrimination upon the part of the Board or other

state agency,” but “rather is a consequence of demographic

and other factors not within any reasonable responsibility of

the Board.”1 * * * 5 The District Court and the Court of Appeals

answer was in the negative and should be affirmed by a denial

of the Petitioners’ petition for a writ of certiorari.

The second issue correctly decided by the District Court

and the Appellate Court is as follows: whether once a de

jure school system has implemented a desegregation plan, as

approved by the District Court and the Court of Appeals, with

petition having been denied by the United States Supreme

Court, is there any Constitutional requirement that additional

white students received into the school system through annex

ation subsequent to the District Court order be dispersed

throughout the system in order to achieve a racial balance

system-wide? Both the District Court and the Court of Ap

peals answered this question in the negative and should be

affirmed by this court’s denial of the Petitioners’ petition for

writ of certiorari.

The October 20, 1975 2-1 decision of the Court of Appeals

affirms the District Court without any qualifications. A peti

tion for rehearing and a suggestion of a rehearing en banc

in said case was denied by the Court of Appeals on January

27, 1976. A copy of said opinions appears as Appendix A to

this brief in opposition.

1 Mapp v. Board of Education of Chattanooga, 329 F.Supp. 1374,

1384 (aff’d 477 F .2d 851) (6th Cir. 197 3 ), cert, denied, 414 U.S.

1022 (1 9 7 3 ). As to the Junior High Schools the District Court said:

“Rather, such limited racial imbalance as may remain is the conse

quence of demographical, residential, or other factors which in

no reasonable sense could be attributed to School Board action

or inaction, past or present, nor to that of any other state agency.

The Court is accordingly of the opinion that the defendants’ plan

for desegregation of the Chattanooga Junior High Schools will

eliminate ‘all vestiges of state imposed segregation’ as required

by the Swann decision.” (Emphasis added)

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The Action Under Review Here

This petition seeks to review a judgment of the District

Court in a school desegregation case affirmed by the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, where the Dis

trict Court refused to order the submission of a new desegrega

tion plan when two high schools remained substantially all

black in spite of affirmative efforts by the Chattanooga Board

of Education (hereinafter referred to as C B E ) to desegregate

said schools and where subsequent and proposed territorial

annexation would appear to provide additional white students

in the system. Such is the essence of respondent’s appeal,

Case No. 74-2100, and the Court of Appeals affirmed.

All of the testimony with reference to the subsequent and

proposed annexation was introduced by the Petitioners in re

buttal and response to a motion for further relief by CBE

requesting amendment of the Amended Desegregation Plan of

June 16, 1971. The motion of CBE was the reason for the

evidentiary hearing in October of 1973.

The District Court’s opinion also refused to allow CBE to

amend a previously approved desegregation plan involving

decisions based upon race, contiguous busing, pairing, cluster

ing, and racial gerrymandering of zones. The limited amend

ment was sought by respondent (C B E) in order to receive

the Court’s permission to implement changes in the desegrega

tion plan designed to diminish the white withdrawal from the

system. The Court of Appeals affirmed the District Court, No.

74-2101.

Factual Background

On July 22, 1955, respondent issued its initial statement

of policy in response to the decisions of this Court in Broum

v. Board of Education of Topeka I, 347 U.S. 483, and Brown

11, 349 U.S. 295, decided on May 17, 1954 and May 31, 1954,

respectively, on the subject of student desegregation in public

4

schools. The opening paragraph of said statement read as

follows:

“The Chattanooga Board of Education will comply with

the decision of the United States Supreme Court on the

matter of integration in the public schools.”2

The Board immediately undertook a process of elucida

tion with the formation of an interracial advisory committee.3

The elucidation process was continued until this litigation

was filed on April 6, 1960. A gradual desegregation plan was

approved in 1962 with 16 selected elementary schools being

desegregated in September of that year in grades one, two, and

three. All dual zones would have been abolished by 1988.

At that point in time all parties presumed such to be compli

ance with the Constitution.

The pace of the desegregation was accelerated pursuant to

District Court order following a motion for further relief by

plaintiffs, filed March 29, 1965. The complete elimination of

dual zones in all grades was effected by December, 1986. Sub

sequent to affirmance by the Court of Appeals,4 the only

issue remaining was that of faculty assignments until February

of 1971 when the District Court dismissed a motion by Peti

tioners for summary judgment, but set an evidentiary hearing

classifying the issues for trial and placing the burden of proof

upon Respondent to prove that the actions taken by Respon

dent met the obligation to establish a unitary school system.

Shortly after this Court’s opinion in Swarm v. Charlotte-

M ecklenburg Board o f Education, 402 U.S. 1 (4/20/71) in

May, the evidentiary hearing was completed and a new de

segregation plan was ordered to “maximize integration” re

2 The complete text of this statement appears as Appendix C in a

petition filed by CBE with this Court on January 29, 1975, No. 75-1077.

3 Said statement appears as Appendix D in petition No. 75-1077.

4 373 F.2d 75 (1967 ).

5

quiring for the first time decisions based upon race for the

purpose of achieving an adequate constitutional remedy.5

Initial and partial implementation of the 1971 desegregation

plan began in September of 1971 under the supervision of the

District Court.

Petitioners took an appeal from this decision on the basis

that the deviations from a racial balance in the approved plan

were unacceptable and unconstitutional. A cross appeal was

taken by CBE contending that remedial measures permitted

by this Court in Swann were permissible, not required, and

only in a school system found to be in default of its constitu

tional obligation; and that CBE was not in default. CBE

further contended that the District Court opinion in its refer

ence to maximizing integration read the racial balance lan

guage in Swann as being constitutionally mandatory' and not

merely “a starting point.”

In a 2-1 Appellate Court decision rendered on October 11,

1972 the case was remanded to the District Court. Following

a motion for rehearing and suggestion of rehearing en banc

by petitioners, a rehearing en banc was granted with oral

argument taking place on December 14, 1972. On April 30,

1973, 477 F,2d 851, an en banc decision of the Court of Ap

peals reversed the 2-1 decision and affirmed the District Court s

opinion.6

In the summer of 1973 and as a result of the experience of

two years under the amended desegregation plan, CBE, having

experienced substantial withdrawal of white students from the

system, conducted a careful evaluation of the system and

particularly the possible causes of the withdrawal from the

schools. The 1971 amended desegregation plan had not been

fully implemented in the elementary and junior high schools

5 329 F.Supp. 1374 (1 9 7 1 ).

6 477 F .2d 851, with Judges Weick and O’Sullivan dissenting and with

a separate concurrence by Judge Miller,

6

during the two years experience under examination. CBE also

made a projection of the possible impact upon the system of

additional busing projected for full implementation of the

plan. Recognizing the possible constitutional obligation upon

a board to avoid inaction which might later be alleged to have

contributed to student resegregation, CBE, on July 20, 1973,

filed a Motion for Further Relief: to Adjust Amended Plan of

Desegregation, as filed June 16, 1971. An extended evidentiary

hearing was held in Gctber of 1973 in which the actual ex

perience of CBE in September of 1971, September 1972, and

September 1973 was presented to the District Court, as well

as CBE’s plan for attempting to counter the white student

withdrawal as reflected by the statistical data for the three

years in question.

In rebuttal, Petitioners offered testimony with reference to

the probable impact of the completion of annexation (then

imminent) of certain areas contiguous to the Chattanooga

system with said areas being populated predominately by white

students.

CBE’s motion to amend the plan was denied in an opinion

entered on November 16, 1973. Such opinion provided specific

guidelines to CBE as to the creation of zones with reference

to annexed schools, the adjustment of zones within the system,

and further providing that any such creation or adjustment of

zones would be required to be submitted to the federal court

30 days prior to their effective date.

On December 26, 1973, Petitioners filed a motion to amend

the memorandum opinion of November 16, 1973 and for a

new trial and further relief. Said motion was supplemented

with an amendment on January 7, 1974. Said motion was

denied by the District Court on June 20, 1974 and subsequent

thereto on July 12, 1974 Petitioners filed a notice of appeal

requesting a complete new desegregation plan for the Chatta

nooga system. Subsequent thereto on July 22, CBE filed a cross

appeal with reference to the District Court’s denial of its

7

motion to amend the plan. Both cases were docketed in the

Appellate Court on September 30, 19747

The appellate oral argument was held on April 18, 1975

resulting in a 2-1 decision affirming the District Court without

qualifications, said opinion being filed on October 20, 1975.7 8

Thereafter, the Petitioners filed “Motion for Rehearing or Re

hearing en banc” on November 4, 1975 followed by an “Amend

ed Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion of Rehearing en

banc” on November 21, 1975, pursuant to a grant of extension

in time in which to file said amendment, having been noted on

November 4, 1975.

In the interim between the filing of the original motion for

rehearing and the filing of the petition for rehearing, this Court

granted certiorari in the case of Pasadena City Board of Educa

tion, et al. v. Nancy Anne Spangler, et al. and United States

of America, No. 75-164, on November 11, 1975.

In the amended petition of November 21, 1975 Petitioners

brought to the attention of the Court of Appeals the second

question presented in the petition for writ of certiorari filed on

behalf of the Pasadena City Board of Education which read

as follows:

“2) Is a school system required to amend its judicially

validated desegregation plan to accommodate for annual

demographic changes for which it is in no way respon

sible? Id., at 3271.”

The Petitioners went on to suggest that this Court’s decision

in Spangler might clarify the language of Swann with respect

to the need for “year to year adjustments” and provide guid

ance to the Court of Appeals in re-evaluating its decision in the

Chattanooga case. In the conclusion to their petition of No

7 For a more complete statement of the facts from July, 1955 foiwaid,

see Appendix E to CBE’s petition before this Court, No. 75-1077.

8 Pages 8 (a ) through 2 7 (a ) inclusive in Petitioners’ Appendix and

pages 1 (a ) through 1 7 (a ) of Respondent’s petition in No. 75-1077.

8

vember 21, 1975, Petitioners went on to request that any

action upon their motion for rehearing be stayed, pending this

Court’s decision in Spangler, supra.

Upon receiving notification on November 11, 1975 of the

action of this Court in granting certiorari in Spangler, CBE’s

counsel requested and received a copy of the petition for writ

of certiorari as filed on behalf of the Pasadena School Board.

Following an analysis of this petition, CBE sought and received

permission from counsel in the Spangler case to file an amicus

curiae brief in that case. The brief was filed in the last week

of December 1975.

On January 27, 1976 an order by the Appellate Court was

filed denying Petitioners’ petition for a rehearing.9

The next day, Wednesday, January 28, 1976, a petition by

CBE seeking a writ of certiorari to review the judgment of the

United States District Court, Eastern District of Tennessee,

Southern Division, made and entered into this case pursuant

to the memorandum opinion of November 16, 1973, and/or

the affirmance of said opinion of the District Court affirmed

by the United States District Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit on October 20, 1975, was placed in the mail from Cin

cinnati, Ohio directed to the Clerk of the United States Su

preme Court,

On the following day, Thursday, January 29, CBE received

in the United States mail its first notice of the action of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in the

form of a copy of an order denying the petition for rehearing

of plaintiffs-appellants, James Jonathan Mapp, et al, in No.

74-2100, as filed on Tuesday, January 27. Said petition by

CBE was received and filed by the Clerk of this Court on

Friday, January 30.

Petitioners herein did not respond to said petition by CBE.

On Saturday, April 17, 1976, counsel for CBE received a copy

of a letter addressed to counsel for Petitioners herein from the

clerk of this court dated April 14, 1976, indicating this Court’s

9 Pages 2 8 (a ) , 2 9 (a ) Petitioners’ Appendix, and pages 18a, 19a of

Respondent’s Appendix hereto. ■

9

request that Petitioners herein respond to the January 30, 1976

petition by CBE, No, 75-1077.

Subsequent thereto on Monday, April 26, 1976, this petition

was filed with the Clerk of this Court and counsel for CBE

received a copy thereof on April 28, 1976.

There are numerous inaccuracies reflected in the statement

of the case by Petitioners. Illustrative is the reference on page

three referring to the District Court order of February 4, 1972

approving the Board’s plan to establish a system-wide voca

tional technical high school. The record will indicate that

CBE has maintained a system-wide vocational technical high

school since 1966. In fact, counsel for Petitioners excluded

consideration of the Kirkman Technical School from the scope

of the desegregation plan by a statement in open court during

the initial part of the hearing in 1971.

The initial appeal from the decision of November 16, 1973

was that of the Petitioners after the District Court Judge de

nied their motion to amend said order and for a new trial

and/or further relief. It was subsequent to and as a result

of this action by Petitioners that the decision was made by

CBE to cross appeal from that part of the District Court

opinion denying their request for permission to amend its

plan.

A further inaccuracy is reflected on page six where it is

indicated that the four high schools would be "utilized fully

for academic programs.” All of the high schools have other

than academic programs and the change was to make the

programs in all four high schools substantially similar with

regard to their educational content including the nonacademic

area.

In 1971 the Board’s projections with reference to the affirm

ative action to desegregate Riverside and Howard were in no

part dependent upon current proposals for elementary and

junior high school facilities. The initial projections were based

upon students actually in the 9th grade, the 10th grade, and

the 11th grade in the zones as redrawn at the direction of the

Court.

10

An examination of Exhibit B would indicate that the follow

ing references on page seven were inaccurate:

“Since the plan was not implemented in any meaningful

sense in September 1971, . .

“No implementation of elementary provisions of the

Board’s 1971 plan had occurred by the start of the

1972-73 academic year.”

On page nine and ten the Petitioners state:

“It also approved the Board’s proposal to assign students

from the newly annexed areas to over 80% white facilities.”

The proposal to the District Court by CBE in October 1973

did not include any proposals with reference to student assign

ment in newly annexed areas subsequent to the hearing.

SEASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

Certiorari should be denied because the decision of the

Court of Appeals is consistent completely with applicable de

cisions of this Court in Brown 1 and II and its progeny, particu

larly Swann.

Demographic changes and other changes within a school

system, subsequent to district court approval of an amended

plan of desegregation, when not caused either directly or in

directly by such school system’s action or inaction, have no

relevance to the affirmative desegregation constitutional duty

of the school system even though undesirable racial propor

tions in schools in the system are the result.

The argument of the Petitioners ignores cause. They con

strue the constitution to require a school board to act affirma

tively to eradicate racial segregation no matter what caused

the racial segregation; and when their own statement of their

interpretation of the Constitution is limited to “state-imposed

segregation.”10

10 Petition, p. 14.

li

And further as primary support for such a constitutional con

clusion, Petitioners proceed immediately to quote from this

Court’s opinion in Swann v. Charlotte-M ecklenhurg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971). Such quotation utilizes “state-

enforced discrimination” and “state-imposed segregation” indi

cating with unquestioned clarity that this Court was not in

any manner directing its attention to racial segregation caused

by other than state action.

If the Petitioners’ constitutional interpretation is accepted,

all of the states of the Union must then assume, as a consti

tutional duty, the affirmative obligation to act to remove

all racial segregation which may exist in the future, without

any consideration of cause. This Court has not so construed

the Fourteenth Amendment. Brown I and 11 were concerned

solely with complete school segregation created solely by the

state.11

Mr. Justice Brennan’s unanimous opinion in Green v. Coun

ty School Board o f Neiv Kent County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430

(1968), the repeated references to “state-imposed segregation”

made it clear that this Court was not addressing its attention

to racial segregation no matter what its cause.12 Swann, supra,

11 “In each instance they have been denied admission to schools

attended by white children under laws requiring or permitting

segregation according to race.” Brown 7, pp. 487-8. (Emphasis

added)

1 2 Green, supra, included the following:

“. . . the State acting through the local school board and school

officials, organized and operated a dual system, . . .” page 435.

“. . . in the context of the State-imposed segregated pattern . . .”

page 432.

“. . . then operating State-compelled dual systems . . . ” page

432.

“. . . toward disestablishing State-imposed segregation.” page

439.

“. . . for dismantling the State-imposed dual system . . .” page

439.

. . and the Court should retain jurisdiction until it is clear

that State-imposed segregation has been completely removed.”

page 439.

“A desegregation program to effectuate conversion of a State-

imposed dual system to a unitary, non-racial system . . .” page 441.

was completely consistent with this constitutional concept

re-enforcing it with eight or more direct references, in a

manner such as to permit no suggestion of ambiguity.13

Petitioners’ theory is then supported by wholly inaccurate

references to the racial changes since 1971 in an effort to

convince this Court that defendant CBE has somehow misled

the District Court and the Appellate Court by submitting a

paper plan and then failing to implement such plan.

The pace and the scope of racial desegregation in the Chatta

nooga School System (CSS) is reflected in the eight pages

of Exhibit B to this opposition brief. Such is only a minute

portion of the statistical facts submitted to the District Court

during the evidentiary hearing in October of 1973.14

1 3 “We granted certiorari in this case to review important issues

as to the duties of school authorities and the scope of powers of

Federal Courts under this Court’s mandates to eliminate racially

separate schools established and maintained by state action.” (Em

phasis added) Swann, supra, p. 5.

“. . . state-imposed segregation by race in public schools denies

equal protection of the laws.” p. 11

“. . . where dual school systems had historically been maintained

by operation of state laws.” Such is followed by a quote from

Green which includes the term ‘state-imposed segregation.’ p. 13

“. . . the massive problem of converting from the state-enforced

discrimination . . .” p. 14

“. . . to eliminate from the public schools all vestiges of state-

imposed segregation . . .” p. 15

“. . . the responsibilities of school authorities in desegregating

a state-enforced dual school system . . .” p. 18

“. . . a potent weapon for creating or maintaining a state-

segregated school system . . .” p. 21

l 4 Exhibit No. 3, Book entitled, “Chattanooga Public Schools, Chatta

nooga, Tennessee, Attendance Zones. Pupil Enrollment Data, Part III,

Summary Analysis of Enrollment Experience, Black-White Ratio Sta

bility” introduced as evidence (with a copy handed to local counsel,

Mr. Williams) on October 3, 1973, Volume I, page 148 of the trial

transcriot. Such data was prepared from school system summary reports

Form O S/CR 102, entitled “Elementary and Secondary School Civil

13

Petitioners represent to this Court (p. 15) that ‘ By the

end of the 1972-73 academic year, however, little of the 1971

desegregation plan had advanced beyond the drawing board.

(It should be remembered that dual zones had been en

tirely disestablished in this system in 1988.) Twenty-three

(23) of the twenty-nine (29) elementary schools were then

desegregated. One all-black elementary school, Avondale, had

shifted from all-white in 1962-63, to all-black in 1971-72 with

out any action upon the part of CBE. Bell, Donaldson, Pine-

ville, Piney Woods, and Trotter had not been desegregated

because of the lack of transportation needed to implement the

1971 amended plan. East Lake, Highland Park, Howard,

Normal Park, Orchard Knob, Pineville and Smith were not

substantially desegregated because of the same reason. How

ever, such implementation was ordered by the District Court s

opinion of November 16, 1973, which is the subject of this

appeal. Since such final compliance transpired subsequent

to the October 1973 hearing, these facts are not in the record

on appeal as it was fully implemented in January-February

of 1974. The statistical and other evidence of such imple

mentation is now a part of the District Court record as an

exhibit to an affidavit of the School Superintendent, Dr. James

W. Plenry, filed on August 2, 1974. Such facts were made

available to the Court of Appeals prior to or during the oral

argument of April 18, 1975.

The tone and detail of the Petitioners’ argument is designed

to convince this Court that CBE has somehow hoodwinked

both the District and the Appellate Court. The facts reflected

in Exhibit B considered alone negate any such conclusion or

inference. The respondent suggests that judicial notice of

these facts is necessary for the Court s evaluation of factual

inaccuracies which appear throughout the petition.

In the first full paragraph on page 16, the petition com-

Rights Survey” filed each year by CBE as required under Title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, U.S. Department of Health, Education and

Welfare, Office of Civil Rights, Washington, D. C.

14

plains that the action of the District Court Judge character

izes “the situation as one in which a . . . plan . . . had been

implemented fully . . The record is that the District Court

in 1973 ordered full implementation of the elementary and

junior high schools but recognized that the high school part

of the plan had been fully implemented by the introduction

of zoning at the high school level.15 Freedom of choice for the

high schools only had been in effect since 1968 since the dual

zones had been abolished. The three formerly all-white high

schools had been substantially desegregated voluntarily by

1971. (See Exhibit B, p. 27a).

The dissent at the Appellate level confirms the above

analysis with reference to elementary and junior high schools

with the opening sentence of his dissent from the denial of

the petition to rehear:

“Although the Board of Education of the City of Chatta

nooga has at long last, under orders of the Supreme

Court, and the United States District Court, proceeded

to bring its grade schools and junior high schools into

com pliance with the Constitution o f the United States,

as to two of its high schools it has signally failed to do

so.” (emphasis added)

Petitioners confusion is further reflected on page 18 where

it states that the Court of Appeals, “. . . operated on the in

correct assumption that the 1971 (high school) provisions

had been fully implemented in September of 1971.” Such was

a fact, and not an incorrect assumption, evident from the

record, not challenged in the trial court.56 The plan did not

5 5 Mapp v. Board of Education, 366 F.Supp. 1257 (1973) p. 1261:

‘It further appears from the testimony given upon the recent trial

of this cause that the defendants are prepared to promptly effect

implementation of the final school desegregation plan herein ap

proved. Such implementation shall be effected no later than the

commencement of the midyear school semester.”

56 p- 27a of Appendix B, hereto.

15

produce its desired result as to high schools, but such was

not due to failure to implement, but for other reasons be

yond the control of CBE and so found to be a fact by the

District Court; a fact found by the Court of Appeals not

to be clearly erroneous.17

The allegation that CBE has immunized its system “from

effecting any meaningful desegregation” is in stark contrast

to the results. So is the charge that it pursued “every tactical

advantage to postpone the day when its implementation is

actually required.” (p. 19)

17 pp. 5a, 6a of Appendix A hereto:

Having implemented the plan for desegregating the high schools

by establishing zones for attendances which were designed to

achieve a high degree of racial balance throughout the system,

and having provided further for continuance of a majority-to-

minority transfer policy, the district judge conceived that he had

obeyed the mandate of Brown v. Board of Education of 2 opeka

II, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown II) and more particularly of

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971). So do we. Presumably, the district judge might have or

dered a further realignment when the first plan did not achieve the

proper balance ratio, and yet another if that did not hold. Indeed

if such were found to have been required to carry out the constitu

tional mandate to eliminate the vestiges of a dual system, it would

simply have to be done, and we have no doubt the district judge

would faithfully have carried out that duty. What he was finally

faced with here, however, was rather a more subtle and lingering

malaise of fear and bias in the private sector which persisted after

curative action had been taken to eliminate the dual system itself.

Swann v. Board of Education recognizes that this latter may be

beyond the effective reach of the Equal Protection Clause:

“Our objective in dealing with the issues presented by these

cases is to see that school authorities exclude no pupil of a

racial minority from any school, directly or indirectly, on

account of race; it does not and cannot embrace all the

problems of racial prejudice, even when those problems

contribute to disportionate racial concentrations in some

schools.”

Swann v. Board of Education, supra, 402 U.S. at 23

16

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is respectfully submitted: (1)

that the petition should be denied and that a Writ of Certi

orari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit should not issue in case No. 74-2100, Petitioners’ ap

peal to the Appellate Court; and (2) as the petition by CBE

to this Court, No. 75-1077, requests an affirmance of the Ap

pellate Court decision and that of the District Court, that

the petition of CBE No. 75-1077, also be denied, including

No. 74-2101.

Respectfully submitted,

W ITT, GAITHER, RICHARDSON,

HENNISS & WHITAKER

RAYMOND B. W ITT, JR.

Attorneys for Respondent

Chattanooga Board of Education

1100 American National Bank

Building

Chattanooga, Tennessee 37402

Date: May 13, 1976

APPENDIX A

Nos. 74-2100 and 74-2101

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

J ames J onathan Mapp, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants (74-2100),

Plaintiffs-Appellees (74-2101),

v.

T he B oard of E ducation of the

C ity of Chattanooga, T ennessee,

et a l,

Defendants-Appellees (74-2100),

Defendants-Appellants (74-2101).

A p p e a l from the

United States District

Court for the Eastern

District of Tennessee.

Decided and Filed October 20, 1975.

Before: W eick, E dwards and E ngel, Circuit Judges.

E ngel, Circuit Judge, delivered the opinion of the Court in

which W eick, Circuit Judge, joined. E dwards, Circuit Judge

(pp. 7a-17a), delivered a separate dissenting opinion.

E ngel, Circuit Judge. This desegregation case is once more

before the court,' this time on cross-appeals from an order of

the district court entered June 24, 1974. That order denied

motions filed by both parties to modify or amend an earlier

order of the court entered December 18, 1973, directed imple-

' For previous decisions of this court in this litigation see Mapp v.

Board of Education of Chattanooga, 295 F . 2d 617 (6th Cir 1961)

319 F. 2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963 ), 373 F . 2d 75 (6th Cir. 1967). 477

F. 2d 851 (6th Cir. 1973), cert, denied 414 U.S. 1022,

la

2a

mentation of the final school desegregation plan previously ap

proved by the court with certain modifications. The December

18, 1973 order provided as well that “[To] the extent the

Court has previously given only tentative approval to the High

School Zoning Plan, the same is now approved finally.”

Both appeals in effect seek to relitigate all of those same

issues which we decided in an en banc decision in this court,

reported in Mapp v. Board of Education o f Chattanooga, 477

F. 2d 851 (6th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1022 (1973).

We there affirmed a final plan of desegregation in all respects

except as to the high schools in Chattanooga.

While the district judge had at that time approved the plan

as to Kirkman Technical High School, and our affirmance made

the same final, District Judge Frank W. Wilson had given only

tentative approval to the plan for desegregation for other high

schools in the City of Chattanooga, see Mapp v. Board of

Education of Chattanooga, 341 F. Supp. 193 (E.D. Tenn.

1972), being uncertain particularly whether three rather than

four general purpose high schools would be feasible or desir

able in Chattanooga.

With respect to Judge Wilson’s refusal to modify the previ

ous final plan of desegregation, we find that he did not abuse

his discretion in so doing, particularly since this court has given

its approval of that plan.

Accordingly, we see as the sole issue remaining on this

appeal the question of whether the district judge erred in or

dering final approval of the tentative plan of desegregation for

the Chattanooga high schools.

At the time the tentative plan was proposed, it was an

ticipated that the zoning for the four high schools would

produce a racial balance approximately as follows:

Black Students White Students

Brainerd High School 32% 68%

Chattanooga High School 44% 56%

Howard High School 75% 25%

Riverside High School 75% 25%

3a

When, however, the plan was placed into effect in the fall

of 1971 rather than having the attendance anticipated, the four

high schools experienced the following racial balance:

Black Students White Students

Brainerd High School 39% 61%

Chattanooga High School 43% 57%

Howard High School 99% 1%

Riverside High School 99% 1%

While an actual head count had showed that as late

July 1971 there were 393 (29%) white high school students

in the Howard High School zone and 311 (29%) white students

in the Riverside zone, only ten reported that September to

Howard and three to Riverside.

It is the contention of the plaintiffs that a school board’s

duty in a previously dual and segregated school system cannot

be said to have been performed where, after implementation

of a plan of desegregation, such an imbalance in the racial mix

of the students yet remains. After taking extensive testimony

on this issue and on the other issues raised by the parties’ mo

tions to amend the earlier judgment, Judge Wilson, in his

Memorandum Opinion of November 16, 1973, made the follow

ing findings of fact:

To the extent that the Court has previously given only

tentative approval to the high school zoning plan, final

approval will now be given that plan. Two high schools,

Howard High School and Riverside High School, have not

acquired an enrollment of white students as projected by

the Board when the plan was proposed in 1971, but rather

have remained substantially all black. It was a concern

for the accuracy of these projections that caused the

Court to initially give only tentative approval to the high

school zoning plan. However, subsequent evidence has

now demonstrated that changing demographic conditions

within the City and other de facto conditions beyond the

control and responsibility of the School Board, including

4a

the voluntary withdrawal of white students from the sys

tem, have become the causative factors for the present

racial composition of the student body in those schools

and not the original action of the Board in creating seg

regated schools at these locations. It should be recalled in

this connection that the plan previously approved in

cluded provision for students to elect to transfer from a

school in which they were in a majority to a school in

which they would be in a minority.

While the cause of the departure of white students was

disputed, there can be little doubt upon the record that the

difference between the anticipated mix and the actual atten

dance of the high schools when the plan was put into effect

was due to a substantial departure of white students from the

public schools in Chattanooga, a circumstance which the dis

trict judge found to have occurred beyond the control and

responsibility of the School Board.

No one who firmly believes in the social and educational

value of racial balance in a desegregated school system can

help being seriously concerned when such a plan for achieving

racial balance does not achieve its objectives on implementa

tion. That such a concern was shared by the district judge is

manifest throughout the entire record upon appeal. Neverthe

less, the district judge concluded that the demographic changes

in the city itself were the cause of the remaining imbalance, a

finding which finds support in the record and which we hold

is not clearly erroneous.

We are satisfied that, in giving final approval to the high

school desegregation plan, Judge Wilson was by no means

yielding to irrational concerns over white flight which merely

masked inherent Board resistance to integration. To the con

trary, he carried out the plan in spite of the apprehended re

sult, and beyond that resisted the defendant board s further

efforts to modify the earlier approved plan for the remainder

of the system with this language in his November 27, 1973

opinion:

5a

“The Court is not unsympathetic to the concern expressed

by the Board for minimizing the voluntary departure of

white students from the system. It must be apparent,

however, that this objective cannot serve as a limiting

factor on the constitutional requirement of equal protec

tion of the laws, nor as a justification for retaining cle jure

segregation. Concern over ‘white flight’, as the phenom

enon was often referred to in the record, cannot become

the higher value at the expense of rendering equal pro

tection of the laws the lower value. As stated by the

United States Supreme Court in the case of Monroe v.

Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 . . . :

“We are frankly told in the Brief that without the

transfer option it is apprehended that white students

will flee the school system altogether. ‘But it should

go without saying that the vitality of these constitu

tional principles cannot be allowed to yield simply

because of the disagreement with them.’ ” Brown 11

at 300, . . .

“Moreover, it is the ‘effective disestablishment of a dual

racially segregated school system’ that is required, Wright

v. Council o f City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 . . . not, as

seems to be contended by the defendants, the most ‘effec

tive’ level of voluntarily acceptable ‘mixing’ of the races.”

(Footnote omitted)

Having implemented the plan for desegregating the high

schools by establishing zones for attendances which were de

signed to achieve a high degree of racial balance throughout

the system, and having provided further for continuance of a

majority-to-minority transfer policy, the district judge con

ceived that he had obeyed the mandate of Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka II, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown II) and

more particularly of Swann v. Charlotte-M ecklinburg of Edu

cation, 402 U.S. "l (1971). So do we. Presumably, the district

judge might have ordered a further realignment when the

first plan did not achieve the proper balance ratio, and yet

6a

another if that did not hold. Indeed if such were found to have

been required to carry out the constitutional mandate to elim

inate the vestiges of a dual system, it would simply have to be

done, and we have no doubt the district judge would faithfully

have carried out that duty. What he was finally faced with

here, however, was rather a more subtle and lingering malaise

of fear and bias in the private sector which persisted after

curative action had been taken to eliminate the dual system

itself. Swann v. Board of Education recognizes that this latter

may be beyond the effective reach of the Equal Protection

Clause:

Our objective in dealing with the issues presented by

these cases is to see that school authorities exclude no

pupil of a racial minority from any school, directly or in

directly, on account of race; it does not and cannot em

brace all the problems of racial prejudice, even when

those problems contribute to disproportionate racial con

centrations in some schools.”

Swann v. Board o f Education, supra, 402 U.S. at 23

Affirmed.

E dwards, Circuit Judge, dissenting. This appeal presents

just one significant question: Should we now, under applicable

Supreme Court precedent, affirm the District Judge’s final

order of December 18, 1973, approving a final desegregation

order applicable to the Chattanooga high schools?

With all respect for the sincerity of my colleagues, I can

not join the majority opinion, or approve its result. If the

majority opinion prevails in this court and in the Supreme

Court, it will establish as law the proposition that approxi

mately 60% of the black children in the high schools of the

Chattanooga public school system may be continued forever

in complete racial segregation in all black schools which were

built as such under state law which required a racially dual

school system and which have been continuously segregated

as such down to this very moment. I cannot square this propo

sition with the great command of the Fourteenth Amendment

to provide all American citizens “the equal protection of the

laws.”

The rule of this case is all the more significant because the

smaller numbers, the maturity, and the greater mobility of

high school students tend to make practical accomplishment

of high school desegregation the least difficult part of the task

mandated by Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka , 347

U.S. 483 (1954); Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) and Sivann v. Charlotte-M eck-

lenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971).

The en banc per curiam opinion of the Sixth Circuit ( Mapp

v. Board of Education of the City o f Chattanooga, Tennessee,

477 F.2d 851 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1022 (1973))

constituted unqualified approval of two previously entered

opinions and judgments of Judge Wilson, Mapp v. Board of

Education of the City of Chattanooga, 329 F. Supp. 1374 ( E.D.

Tenn. 1971); Mapp. v. Board of Education of the City of Chat

tanooga, 341 F. Supp. 193 (E.D. Tenn. 1972). In these two

cases Judge Wilson had approved final desegregation orders

concerning the grade schools and junior high schools. Equally

7a

8a

clearly, he had not approved any final desegregation plan for

the high schools. As to the high schools, in his first opinion

he said:

High Schools

During the school year 1970-71, the Chattanooga School

System operated five high schools. These included four

general curricula high schools and one technical high

school. Kirkman Technical High School offers a special

ized curricula in the technical and vocational field and is

the only school of its kind in the system. It draws its stu

dents from all areas of the City and is open to all students

in the City on a wholly non-discriminatory basis pursuant

to prior orders of this Court. Last year Kirkman Technical

High School had an enrollment of 1218 students, of which

129 were black and 1089 were white. The relatively low

enrollment of black students was due in part to the fact

that Howard High School and Riverside High School,

both of which were all black high schools last year,

offered many of the same technical and vocational courses

as were offered at Kirkman. Under the defendants’ plan

these programs will be concentrated at Kirkman with the

result that the enrollment at Kirkman is expected to rise

to 1646 students, with a racial composition of 45% black

students and 55% white students. No issue exists in the

case but that Kirkman Technical High School is a special

ized school, that it is fully desegregated, and that it is a

unitary school.

While some variation in the curricula exists, the remain

ing four high schools, City High School, Brainerd High

School, Howard High School, and Riverside High School,

each offer a similar general high school curriculum. At the

time when a dual school system was operated by the

School Board, City High School and Brainerd High School

were operated as white schools and Howard High School

and Riverside High School were operated as black schools.

At that time the black high schools were zoned, but the

white high schools were not. When the dual school sys-

9a

tem was abolished by order of the Court in 1962, the

defendants proposed and the Court approved a free

dom of choice plan with regard to the high schools.

The plan accomplished some desegregation of the

former white high schools, with City having 141 black

students out of an enrollment of 1435 and Brainerd

having 184 black students out of an enrollment of

1344 during the 1970-71 school year. However, both

Howard, with an enrollment of 1313, and Riverside, with

an enrollment of 1057, remained all black. The freedom

of choice plan “having failed to undo segregation * * *

freedom of choice must be held unacceptable.” Green v.

County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430,

88 S.Ct. 1689, 20 L.Ed.2d 716 (1968).

The School Board proposes to accomplish a unitary

school system within the high schools by zoning the four

general curricula high schools with the following results

in terms of student ratios:

Black Students White Students

Brainerd High School 32% 68%

Chattanooga High School 44% 56%

Howard High School 75% 25%

Riverside High School 75% 25%

The plaintiffs have interposed objections to the defen

dants’ high school plan upon the ground that it does not

achieve a racial balance in each school. To some extent

these objections are based upon matters of educational

policy rather than legal requirements. It is of course ap

parent that the former white high schools, particularly

Brainerd High School, remain predominantly white and

that the former black high schools remain predominant

ly black. However, the defendants offer some evidence

in support of the burden cast upon them to justify the

remaining imbalance. The need for tying the high school

zones to feeder junior high schools is part of the defen

dants’ explanation. Residential patterns, natural geograph

ical features, arterial highways, and other factors are also

part of the defendants’ explanation.

10a

A matter that has given concern to the Court, however,

and which the Court feels is not adequately covered in the

present record, is the extent to which the statistical data

upon which the defendants’ plan is based will correspond

with actual experience. Among other matters there ap

pears to be substantial unused capacity in one or more of

the city high schools. Before the Court can properly

evaluate the reliability of the statistical data regarding the

high schools, the Court needs to know whether the un

used capacity does in fact exist and, if so, where it exists,

whether it will be used and, if so, how it will be used.

It would be unfortunate indeed if experience shortly

proved the statistical data inadequate and inaccurate and

this Court was deprived of the opportunity of considering

those matters until on some appellate remand, as occurred

in the recent case of Davis v. Board of School Commis

sioners of Mobile, 402 U.S. 33, 91 S.Ct. 1289, 28 L.Ed.2d

577.

The plaintiff has submitted a high school plan with high

school zones which the plaintiff’s witness has testified will

achieve a racial balance in each high school. However,

this plan is not tied into the junior high school plan here

inabove approved and the Court is unable to say whether

it could be so tied it. Furthermore, the same statistical

problem discussed above would appear to exist with re

gard to the plaintiff’s plan.

The Court accordingly is unable to give final approval

to a high school desegregation plan at this time. Time,

however, is a pressing factor. Pre-school activities will

commence at each high school within less than a week,

if in fact they have not already commenced. Full com

mencement of the fall term is only one month away. It

is clear that the high schools must move at least as far as

is proposed in the defendants high school plan. Accord

ingly, the Court will give tentative approval only at this

time to the defendants’ high school plan in order that at

least as much as is therein proposed may be placed into

operation at the commencement of the September 1971

term of school. Further prompt but orderly judicial pro

11a

ceedings must ensue before the Court can decide upon a

final plan for desegregation of the high schools.

In the meanwhile, the defendants will be required to

promptly provide the Court with information upon the

student capacity of each of the four high schools under

discussion, upon the amount of unused space in each of

the four high schools, the suitability of such space for

use in high school programs, and the proposed use to be

made of such space, if any. In this connection the de

fendants should likewise advise the Court regarding its

plan as to tuition students. Last year almost one-third of

the total student body at City High School were non

resident tuition paying students. There is no information

in the present record as to the extent the Board proposes

to admit tuition students nor the effect this might have on

the racial composition of the student body. The Court

has no disapproval of the admission of tuition students

nor to the giving of preference to senior students in this

regard, provided that the same does not materially and

unfavorably distort the student racial ratios in the respec

tive schools. Otherwise, the matter of admitting tuition

students addresses itself solely to the discretion of the

Board. No later than the 10th day of enrollment the de

fendants will provide the Court with actual enrollment

data upon each of the four high schools here under dis

cussion.

Mapp v. Board of Education of the Citu of Chattanooga,

supra at 1384-86.

In his second opinion he said:

Tentative approval only having heretofore been given

to the School Board plan for desegregation of the Chatta

nooga high schools other than Kirkman Technical High

School (to which final approval has been given). Further

consideration must be given to this phase of the plan. At

the time that the Court gave its tentative approval to the

high school desegregation plan, the Court desired addi

tional information from the Board of Education as to

12a

whether three, rather than four, general purpose high

schools would be feasible or desirable in Chattanooga. It

now appears, and in this both parties are in agreement,

that three general purpose high schools rather than four

is not feasible or desirable, at least for the present school

year. Having resolved this matter to the satisfaction of

the Court, the defendant Board of Education will accord

ingly submit a further report on or before June 15, 1972,

in which they either demonstrate that any racial imbal

ance remaining in the four general purpose high schools is

not the result of “present or past discriminatory action on

their part” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. at 26, 91 S.Ct. at 1281, 28 L.Ed.2d

554 at 572, or otherwise, and to the extent that the Board

is unable to demonstrate that such racial imbalance which

remains is not the result of past or present discriminatory

action, they should submit a further plan for removal of all

such remaining racial discrimination, the further plan

likewise to be submitted on or before June 15, 1972.

Mapp v. Board of Education of the City o f Chattanooga,

supra at 200,

The opinion and order we now review are quite different,

and if approved by this Court and the Supreme Court, would

represent both a final approval of the school boards current

“plan” for operation of the high schools and holding that the

present operation represents desegregation of the previously

legally segregated dual high school system.

In the opinion we now review Judge Wilson said:

The Court is accordingly of the opinion that the de

fendants have failed to establish either such changed con

ditions as would render its formerly court-approved plan

of school desegregation inadequate or improper to remove

“all remaining vestiges of state imposed segregation or

that its newly proposed plan would accomplish that result.

To the extent that the Court has previously given only

tentative approval to the high school zoning plan, final

13a

approval will now be given that plan. Two high schools,

Howard High School and Riverside High School, have not

acquired an enrollment of white students as projected by

the Board when the plan was proposed in 1971, but

rather have remained substantially all black. It was a

concern for the accuracy of these projections that caused

the Court to initially give only tentative approval to the

high school zoning plan. However, subsequent evidence

has now demonstrated that changing demographic con

ditions within the City and other de facto conditions

beyond the control and responsibility of the School Board,

including the voluntary withdrawal of white students

from the system, have become the causative factors for the

present racial composition of the student body in those

schools and not the original action of the Board in creating

segregated schools at these locations. It should be re

called in this connection that the plan previously ap

proved included provision for students to elect to transfer

from a school in which they were in a majority to a

school in which they would be in a minority.

Mapp v. Board of Education of the City o f Chattanooga,

366 F. Supp. 1257, 1260-61 (E.D. Tenn. 1973).

Thus, clearly, we now have before us the issue as to whether

or not in the Chattanooga high schools previous unconstitu

tional segregation has been eliminated root and branch.

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968).

Defendant-appellees accept (as they must) the responsi

bility of meeting the standard of Green v. County School

Board of Kent County, supra-.

It is against this background that 13 years after Brown

II commanded the abolition of dual systems we must

measure the effectiveness of respondent School Board s

“freedom-of-choice” plan to achieve that end. The School

Board contends that it has fully discharged its obligation

by adopting a plan by which every student, regardless of

race, may ^freely” choose the school he will attend. The

14a

Board attempts to cast the issue in its broadest form by

arguing that its “freedom-of-choice” plan may be faulted

only by reading the Fourteenth Amendment as universally

requiring “compulsory integration,” a reading it insists the

wording of the Amendment will not support. But that

argument ignores the thrust of Brown II. In the light of

the command of that case, what is involved here is the

question whether the Board has achieved the “racially

nondiscriminatory school system” Brown II held must be

effectuated in order to remedy the established unconsti

tutional deficiencies of its segregated system. In the

context of the state-imposed segregated pattern of long

standing, the fact that in 1965 the Board opened the doors

of the former “white” school to Negro children and of the

Negro ’ school to white children merely begins, not

ends, our inquiry whether the Board has taken steps ade

quate to abolish its dual, segregated system. Brown II

was a call for the dismantling of well-entrenched dual

systems tempered by an awareness that complex and

multifaceted problems would arise which would require

time and flexibility for a successful resolution. School

boards such as the respondent then operating state-com

pelled dual systems were nevertheless clearly charged

with the affirmative duty to take whatever steps might be

necessary to convert to a unitary system in which racial

discrimination would be eliminated root and branch. See

Cooper v. Aaron, supra, at 7; Bradley v. School Board,

382 U.S. 103; cf. W atson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S.

526. The constitutional rights of Negro school children

articulated in Brown I permit no less than this; and it was

to this end that Brown I I commanded school boards to

bend their efforts.4

4 “W e bear in mind that the court has not merely the power

but the duty to render a decree which will so far as possible elimin-

nate the discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like

discrimination in the future.” Louisiana v. United States, 380 U. S.

145, 154. Compare the remedies discussed in, e. g., NLRB v.

Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co., 308 U. S. 241;

15a

In determining whether respondent School Board met

that command by adopting its “freedom-of-choice” plan,

it is relevant that this first step did not come until some

11 years after Brown I was decided and 10 years after

Brown I I directed the making of a “prompt and reason

able start.” This delibei-ate perpetuation of the unconsti

tutional dual system can only have compounded the harm

of such a system. Such delays are no longer tolerable,

for “the governing constitutional principles no longer bear

the imprint of newly enunciated doctrine.” Watson v.

City of Memphis, supra, at 529; see Bradley v. School

Board , supra; Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198. Moreover, a

plan that at this late date fails to provide meaningful as

surance of prompt and effective disestablishment of a

dual system is also intolerable. “The time for mere ‘de

liberate speed’ has run out,” Griffin v. County School

Board, 377 U.S. 218, 234; “the context in which we must

interpret and apply this language [of Brown II] to plans

for desegregation has been significantly altered.” Goss

v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683, 689. See Calhoun

v. Latimer, 377 U.S. 263. The burden on a school board

today is to come forward with a plan that promises real

istically to work, and promises realistically to work now.

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

supra at 437-39.

At the outset we note that we deal with a school district

which at the time of the beginning of this litigation was

clearly and concededly a dual school system segregated by

race according to state statute. We therefore are required to

determine whether or not a public school system (racially

constituted during the 1973-74 school year as follows) can be

held by this court to have been desegregated “root and

branch”:

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S. 173; Standard

Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U. S. 1. See also Griffin v. County

School Board, 377 U. S. 218, 232-234.

16a

White Black % White % Black

Howard 10 999 1 99

Riverside 3 721 1 99

Chattanooga 439 330 57 43

Brainerd 646 404 61 39

There can, of course, be no doubt that Howard and River

side High Schools are “racially separate public schools estab

lished and maintained by state action.” Swann v. Charlotte-

M ecklenburg Board of Education , 402 U.S. 1, 5 (1971). Both

were built as Negro schools under state law which required a

dual school system. T.C.A. §§2377, 2393.9 (Williams 1934).

Twenty-one years after decision of Brown v. Board of Educa

tion o f Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), both high schools (en

compassing 60% of the black high school population of Chatta

nooga) are still (and always have been) essentially 100%

black. As to these schools and students, there has been no

desegregation at all.

Defendants-Appellees contend that two measures which they

took should be accepted as the equivalent of desegregation.

They are: 1) the inauguration of a freedom of choice plan, and

2) a change in zone boundaries which was calculated (it is

claimed) to introduce 25% of white students into both high

schools. Defendants-appellees freely admit that neither mea

sure was effective in changing the segregated character of the

Howard and Riverside High Schools.

At to the freedom of choice plans, the Supreme Court has

repeatedly held that ineffective freedom of choice plans

are not a substitute for desegregation in fact. See Green v.

County School Board of New Kent County, supra; Monroe v.

Board o f Commissioners o f the City o f Jackson, 391 U.S. 450

(1968).

Defendants-appellees’ strongest reliance is upon the second

contention that they “zoned” 25% white students into Howard

and Riverside but that the white students thus assigned avoided

the assignment by “white-flight.” As to this measure, we have

17a

no findings of fact concerning defendants-appellees’ conten

tion. But if we assumed their truth, we clearly would not have

exhausted the possibilities for successful desegregation nor

satisfied the constitutional command. Many possibilities for

desegregation remain, including pairing of white and black

schools and high school construction which would make de

segregated zones more feasible. In any instance, the defen

dant school board should be required to propose a new and

realistic plan to meet its constitutional duty. See Swann v.

Charlotte-M ecklenbiirg Board of Education , supra, at 15-21;

Brinkman v. G illigan ,---- F .2 d ------(6th Cir. 1975) ( Decided

June 24, 1975, No. 75-1410).

In my judgment the case should be affirmed as to the grade

schools and junior high schools. The judgment should be

vacated and remanded as to the high schools. All other issues

presented by either party should be summarily denied.

18a

UNITED ST A T E S C O U R T O F A PPEA LS

F O R T H E S IX T H C IR C U IT

No. 74-2100

JA M ES JONATH AN MAPP, et a!.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

T H E BO A R D O F E D U C A T IO N O F TPIE C IT Y

O F CHATTAN OOGA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

O R D E R

(Filed January 27, 1976)

Before: WEICK, EDWARDS and ENGEL, Circuit Judges.

This cause came on for hearing on the petition for re

hearing with a suggestion that it be reheard en banc.

Judges Edwards and McCree having requested en banc

rehearing for the reasons set forth in Judge Edwards’ dis

senting opinion, but it appearing to the court that less than

a majority of the court has voted in favor thereof, the petition

for rehearing was referred to the panel which originally heard

the appeal and was determined not to be well taken, Judge

Edwards dissenting.

It is therefore ordered that the petition for rehearing be

denied.

ENTERED BY ORDER OF THE COURT

/s/ JOHN P. HERMAN

Clerk

19a

Re: James Jonathan Mapp v.

The Board of Education of the City

of Chattanooga, Tennessee

No. 74-2100

EDWARDS, Circuit Judge, dissenting. Although the Board

of Education of the City of Chattanooga has at long last, un

der orders of the Supreme Court of the United States, this

court, and the United States District Court, proceeded to

bring both its grade schools and junior high schools into com

pliance with the Constitution of the United States, as to two

of its high schools it has signally failed to do so. The ma

jority opinion of this court would establish as law the propo

sition that approximately 60% of the black children of the

Chattanooga high school system may be continued forever

in complete segregation in ail black high schools. The two

black high schools at issue were built as such under state law

that required a racially dual school system and have been con

tinuously segregated as such down to this very moment.

There can be no doubt that the two black high schools

are racially separate public schools established and main

tained by state action and that as to these schools there has

been no desegregation at all. In my judgment it simply can

not be said with any accuracy that the possibilities for success

ful desegregation have been exhausted. As to these schools the

School Board should be required to propose a new and realistic

and effective plan to meet its constitutional duty.

Report #5-A Elementary Schools chattahooga p u b l i c schools

C h a t t a n o o g a , T e n n e s s e e

COMPARISON OF TENTH DAY PUPIL ENROLLMENT FOR EACH SCHOOL BY YEAR AND BY RACE

FROM 1 9 6 2 - 6 3 TO PRESENT

E l e m e n t a r y S c h o o l s

1 0 t h Day E n r o l l m e n t ( R e s i d e n t and N o n r e s i d e n t P u n i l s )

Ainnicol

( 1 - 6 )

Avondale

( 1 - 6 )

B a r g e r

( 1 - 6 )

B e l l

( 1 - 6 )

Brown

( 1 - 6 )

C a r p e n t e r

( 1 - 6 )

C h a t t a . Avenue

_______ O z S ) _________

Ce da r H i l l

_______ ________________

Y ea r B W T B W T B W T B W T B W T B W T B W T B W T

*

1 9 6 2 - 6 3 0 317 317 0 561 561 62 2 0 622 0 368 361 501 0 501 524 0 524 0 171 171

* *

1 9 6 3 - 6 4 . . . 31 8 1 70 4 88 0 543 5 43 5 9 2 0 592 0 332 332

Cloi

F i f t

ed - I

h S t r i

a s t

e t 481 0 481 0 148 148

)V**

1 9 6 4 - 6 5 . . . . . . 6 39 6 57 0 569 5 69 5 7 3 0 5 7 3 1 319 32C . . . - - - 372 0 372 0 139 139

* * * *

1 9 6 5 - 6 6 . . . . . . 6 2 9 27 6 56 0 547 547 5 6 4 0 564 • 2 3 06 308 ___ ___

Close

R a i l r c

d - He

ad Rel

ward

o c a t i ( n 0 1 96 196

■ k k k k k

1 9 6 6 - 6 7 _ _ _ . . . _ 64 1 18 6 59 0 5 1 8 5 1 8 54 5 0 545 114 2 88 4 0 2

C

Midi

pened

l e Sc\ o o l ___ ___ ___ 0 210 2 10

1 9 6 7 - 6 8 _ _ _ 6 4 8 17 6 65 0 4 7 8 4 7 8 57 6 0 5 76 112. 2 64 37 6 373

( 1 - 4 )

19 392 . . . ___ ___ 0 187 187

1 9 6 8 - 6 9

Am cjied i

Count}

rom

6 83 7 6 9 0 0 4 9 4 49 4 574 0 574 125 243 368 331 26 357 ___ ___ ___ 0 162 162

1 9 6 9 - 7 0 69 63 132 6 72 5 6 77 2 4 3 2 43 4 561 6 567 122 2 36 3 58 344 10 354 _ _ _ 0 176 176

1 9 7 0 - 7 1 75 35 110 6 4 0 1 641 2 4 5 3 4 5 5 5 14 9 5 23 121 2 16 337 301 8 3 09 _ _ _ 0 174 174

1 9 7 1 - 7 2

C lo s e

and

d-C arp

R i ve nr

e n t e r

ont 669 0 66 9 71

( 4 - 6 )

258 3 29 4 1 6 2 4 1 8 106 205 311 4 0 6

( 1 - 6 )

46 4 52 _ _ __ E

Cl ose d

a s t La ke

1 9 7 2 - 7 3 ... _ _ 6 6 0 0 6 60 9 0

( 4 - 6 )

222 312 421 2 4 2 3 108 2 10 3 18 337 27 364 _ _ _ _ _ _

1 5 7 3 - 7 4 _ ... _ 6 2 9 0 629 93 20 8 301 3 80 2 382 101 199 3 0 0 3 10 13 323 _ _ ... ...

1 9 7 4 - 7 5

1 9 7 5 - 7 6

1 9 7 6 - 7 7

1 5 7 7 - 7 8

1 9 7 8 - 7 9

1 9 7 9 - 8 0

Desegregation Schedule: *16 Schools (1-3) **A11 Schools (1-4) ***A11 Schools (1-6) ****A11 Schools (1-7) *****A11-Schools (1.-12)

APPEN

DIX B

Elementary Schools (Continued)

1 0 t h Day E n r o l l m e n t ( R e s i d e n t and N o n r e s i d e n t P u p i l s )

S c h oo l

C l i f t o n H i l l s

( 1 - 6 )

Davenport

( 1 - 6 )

Donaldson

( 1 - 6 )

E a s t C h a t t a .

_ _ ( 1 - 6 ) ________

E a s t F i f t h

( 1 - 6 )

E a s t Lake

( 1 - 6 1

Ea s t d a l e

1 - 6 )

F o r t Che at

( 1 - 6 )

lam

Y e a r B . W T B W 1 T B W T B W T B W T B W xr B w T B w T

*

1 9 6 2 - 6 3 0 49C 4 9 6 394 J 394 562 0 5 6 : 0 4 84 484 71C 0 71C 0 6 96 6 96 1 48 4 4 8 5 155 0 155

* *

1 9 6 3 - 6 4 0 513 5 1 3 397 3 4 0 0 5 4 3 0 5 43 3 5 40 543 862

( 1 - 6 )

1 862 0 744 744 20 506 52 6 87 0 87

* * *

1 9 6 4 - 6 5 0 514 51 4 355 7 362 5 33 0 5 33 20 5 23 5 4 3 609 41 650 0 6 99 6 99 37 4 5 3 4 9 0

d o s t

{

d Nov.

Freewa

19 63

y)

* * * *

1 9 6 5 - 6 6 0 5 16 5 16 354 14 3 68 5 36 0 536 21 4 7 7 4 9 8 6 0 3 32 6 35 0 6 23 6 23 51 4 4 0 4 91 ___ ___ _

* * * * *

1 9 6 6 - 6 7 11 5 18 529 30 8 16 3 24 5 19 0 5 19 23 4 6 5 4 8 8 6 10 24 634 0 601 601 50 44 4 4 94 ___ ___

1 9 6 7 - 6 8 19 4 6 5 4 8 4 284 19 3 0 3 5 02 0 502 16 4 4 8 4 64 2 0 8

( 5 - 6 )

3 211 1 5 62 5 63 71 3 60 4 31 ___ ___ ___

1 9 6 8 - 6 9 17 4 4 7 4 64 275 18 293 541 0 541 8 4 22 4 3 0 2 0 0 10 210 1 5 4 0 541 1 08 315 4 2 3 ___ ___ ___

1 9 6 9 - 7 0 18 4 4 6 4 64 255 9 264 5 12 0 5 12 7 4 1 0 4 1 7 152 4 156 1 4 7 0 471 1 50 261 4 11 ...... ___ ___

1 9 7 0 - 7 1 17 4 1 1 4 2 8 2 34 9 243 471 0 47 1 12 382 394 146 7 153 3 4 3 9 4 42 234 1 80 4 14 ___ - - -

1 9 7 1 - 7 2 27 311 338

C l os e

H

i - Ho

jmlock

vard

4 6 2 • 0 4 6 2 41 381 4 2 2

Clos ec

3 5 30 5 33 169

( 4 - 6 )

170 339 ___ ___ ___

1 9 7 2 - 7 3 39 3 59 3 98 . . . . . . 4 37 0 4 37 91 37 4 4 6 5 ___ ___ 2 512 514 244 142 3 86 ___ ___ ___

1 9 7 3 - 7 4 31 3 49 3 8 0 ___ ___ ___ 4 1 9 0 4 1 9 1 06 2 80 3 86 ___ ___ ___ 4 4 5 5 ' 4 5 9 3 36 111 4 4 7 _ . . .

1 9 7 4 - 7 5

1 9 7 5 - 7 6

1 9 7 6 - 7 7

1 9 7 7 - 7 8

1 9 7 8 - 7 9

1 9 7 9 - 8 0

Desegregation Schedule: *16 Schools (1-3) **A11 Schools (1-4) ***A11 Schools (1-6) ****A11 Schools (1-7) *****A11-Schools (hl2)

_________________ pay Enrollment; (Resident and Nonresident Pupil s)

Elementary Schools (Continued) ... . ..... . --

Ga rbe r

( 1 - 6 )

Glenwood

( 1 - 6 )

Henry

( 1 - 6 )

O '•O

H i gh l an d P a r k

U - 6 )

Howard

( 1 - 6 )

Long

( 1 - 6 )

M i s s i o n a r y

( 1 - 6 )

U d g e

Y ea r B W T B W T B W T B W T B W T B W T B W T B W T

*