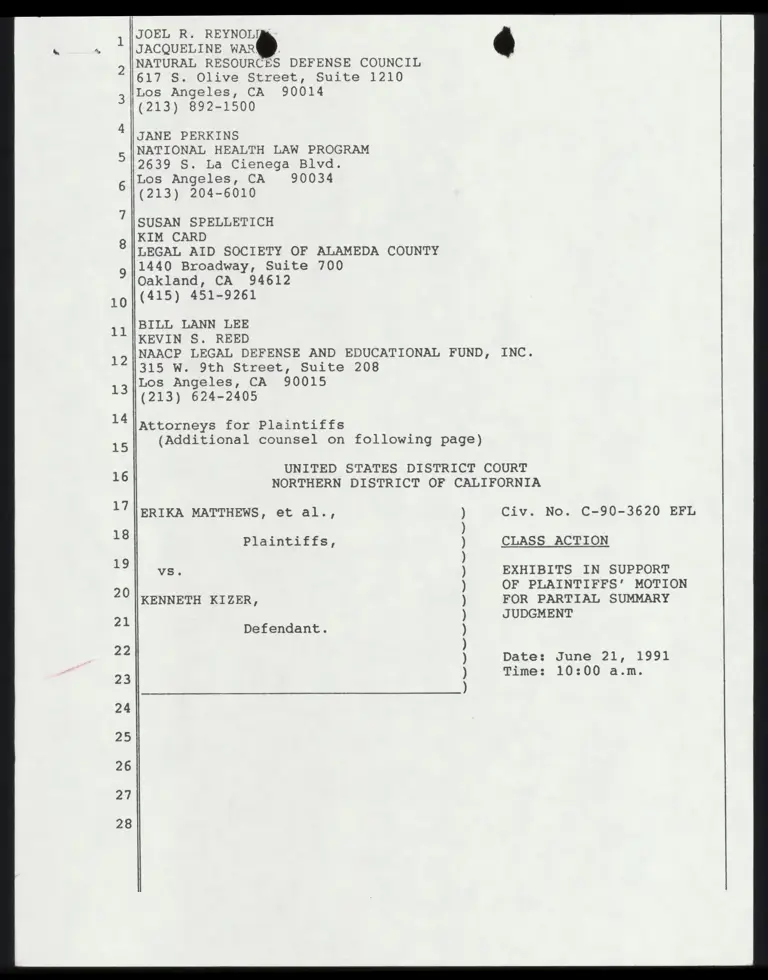

Exhibits in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for Partial Summary Judgement (Redacted)

Working File

June 21, 1991

315 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Matthews v. Kizer Hardbacks. Exhibits in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for Partial Summary Judgement (Redacted), 1991. 06184496-fa4d-f011-8779-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/590b41da-a2a1-4b55-8f4c-153e2490652f/exhibits-in-support-of-plaintiffs-motion-for-partial-summary-judgement-redacted. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

27

28

JOEL R. REYNOLIL

JACQUELINE oe )

NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL

617 S. Olive Street, Suite 1210

Los Angeles, CA 90014

(213) 892-1500

JANE PERKINS

NATIONAL HEALTH LAW PROGRAM

2639 S. La Cienega Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA 90034

(213) 204-6010

SUSAN SPELLETICH

KIM CARD

LEGAL AID SOCIETY OF ALAMEDA COUNTY

1440 Broadway, Suite 700

Oakland, CA 94612

(415) 451-9261

BILL LANN LEE

KEVIN S. REED

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

315 W. 9th Street, Suite 208

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 624-2405

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

(Additional counsel on following page)

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

ERIKA MATTHEWS, et al., Civ. No. C-90-3620 EFL

Plaintiffs, CLASS ACTION

vs. EXHIBITS IN SUPPORT

OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION

FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY

JUDGMENT

KENNETH KIZER,

Defendant.

Date: June 21, 1991

Time: 10:00 a.m.

V

a

t

”

Na

st

”

at

”

Nu

t?

N

a

”

a

t

”

u

l

?

“a

t?

“u

ni

“

v

u

?

“a

d?

“w

et

?

27

28

MARK D. ROSENBZgM

ACLU FOUNDATIO F SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

633 South ShattC Place

Los Angeles, CA 90005

(213) 487-1720

EDWARD M. CHEN

ACLU FOUNDATION OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA

1663 Mission Street, Suite 460

San Francisco, CA 94103

(415) 621-2493

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibits

Declaration of Dr. John F. Rosen

Declaration of Dr. Herbert L. Needleman

CHDP Provider Information Notice #91-6 from

Director Kenneth Kizer to CHDP Providers Re:

Lead Poisoning in Children (March 12, 1991)

S. Roan, "High Number of Lead Poison Cases

Found," L.A. Times, Aug. 30, 1990, A3, col.’1

DHS, Statewide: Fiscal Year 1989-90 Ethnicity

by Age Group by Funding Source by Lead Test

{Feb. 15, 1991)

DHS, Statewide: July 1990 thru January 1991

Ethnicity by Age Group by Funding Source by

Lead Test (Feb. 15, 1991)

DHS Medical Care Statistics Section,

California’s Medical Assistance Program

Annual Statistical Report Calendar Year 1989

Tables 20 and 29)

DHS, Fiscal Year 1989-90 Provider Number by

Age Group by Funding Source by Lead Test:

County of Residence = Santa Clara (Feb. 15,

1931)

DHS, Fiscal Year 1989-90 Ethnicity by Age

Group By Funding Source by Lead Test: County

of Residence = Los Angeles (Feb. 15, 1991)

Deposition of Ruth Range (excerpts)

Deposition of Dr. Maridee A. Gregory

(excerpts)

Health Care Coverage for Children: Hearing

Before the Senate Committee on Finance, 101st

Cong., lst Sess. 24 (statement of Kay A.

Johnson, Director, Children’s Defense Fund

Health Division) (June 20, 1989)

Report of the House Budget Committee on H.R.

3299 (Sept. 20, 1989) reprinted in Medicare &

Medicaid Guide (CCH), Extra Edition No. 596

(Oct. 5, 1989)

HCFA, State Medicaid Manual, § 5123.2(D)

(incorporating revisions contained in HCFA

transmittals of April and July 1990)

llExhibit 0 -- 9: Medical Assistance M@ghal, § 5-70-00 et

2 seq. (June 28, 1972)

3 Exhibit P -~- HCFA, State Medicaid Manual § 5122 (April

1988)

4 Exhibit Q -- HEW, A Guide to Screening-EPSDT Medicaid

5 (Chapter 21) (1974)

6 Exhibit R -- HEW, Information Memorandum, "New Technology

Available in the Screening and Detection of

. Lead Poisoning and EPSDT" (1M-77-32 (MSA))

(June 9, 1977), reprinted in Medicare &

8 Medicaid Guide (CCH) ¥ 28,505

9 Exhibit § =~ HEW, A Guide to Administration, Diagnosis and

Treatment for the EPSDT Program under

10 Medicaid (1977) (excerpts)

11 Exhibit T ~~ 135 Cong. Rec. S 13233 (October 12, 1989)

12 Exhibit U -- Explanation of the Conference Committee

Affecting Medicare - Medicaid Programs Re:

13 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989

(H.R. 3299), reprinted in Medicare & Medicaid

14 Guide (CCH), Extra Edition No. 603 (Dec. 15,

1989)

15 Exhibit V -- Letter from Charles A. Woffinden, Chief HHS

16 Medicaid Operations Branch to Michael Quinn,

CHDP Research Manager (April 11, 1991)

17 Exhibit W -- Letter from Charles A. Woffinden, Chief HHS

18 Medicaid Operations Branch, to Michael Quinn,

CHDP Research Manager (May 7, 1991)

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

2

27

28

é DECLARATION OF JANE PERIES

I, Jane Perkins, declare:

1. I am one of the attorneys of record for plaintiffs

in this case. The matters stated herein are true and correct,

and if called as a witness, I could competently testify thereto.

2. Attached hereto as Exhibit C is a true and correct

copy of a document entitled "CHDP Provider Information Notice

#91-6 from Director Kenneth Kizer to CHDP Providers Re: Lead

Poisoning in Children (March 12, 1991)."

3. Attached hereto as Exhibit E is a true and correct

copy of a document entitled "DHS, Statewide: Fiscal Year 1989-

90 Ethnicity by Age Group by Funding Source by Lead Test (Feb.

15, .19%91)."

4. Attached hereto as Exhibit F is a true and correct

copy of a document entitled "DHS, Statewide: July 1990 thru

January 1091 Ethnicity by Age Group by Funding Source by Lead

Test (Feb. 15, 1991)."

5. Attached hereto as Exhibit G is a true and correct

copy of a document entitled "DHS Medical Care Statistics

Section, California’s Medical Assistance Program Annual

Statistical Report Calendar Year 1989."

6. Attached hereto as Exhibit H is a true and correct

copy of a document entitled "DHS, Fiscal Year 1989-90 Provider

Number by Age Group by Funding Source by Lead Tests: County of

Residence = Santa Clara (Feb. 15, 1991)."

7. Attached hereto as Exhibit I is a true and correct

copy of a document entitled "DHS, Fiscal Year 1989-90 Ethnicity

by Age Seev dl Funding Source by ge ah County of

Residence = Los Angeles (Feb. 15, 1991)."

8. Attached hereto as Exhibit L is a true and correct

copy of a document entitled "Health Care Coverage for Children:

Hearing Before the Senate Committee on Finance, 10lst Cong., lst

Sess. (statement of Kay A. Johnson, Director, Children’s Defense

Fund Health Division) (June 20, 1989)."

9. Attached hereto as Exhibit M is a true and correct

copy of a document entitled "Report of the House Budget

Committee on H.R. 3299 (Sept. 20, 1989), reprinted in Medicare

& Medicaid Guide (CCH), Extra Edition No. 596 (Oct. 5, 1989)."

10. Attached hereto as Exhibit N is a true and

correct copy of a document entitled "HCFA, State Medicaid

Manual, § 5123.2(D) (April and July 1990)."

11. Attached hereto as Exhibit O is a true and

correct copy of a document entitled "HEW, Medical Assistance

Manual, § 5-70-00 (June 29, 1972)."

12. Attached hereto as Exhibit P is a true and

correct copy of a document entitled "HCFA, State Medicaid Manual

$ 5122 (April 1988)."

13. Attached hereto as Exhibit Q is a true and

correct copy of Chapter 21 from a document entitled "HEW, A

Guide to Screening-EPSDT Medicaid (1974)."

14. Attached hereto as Exhibit R is a true and

correct copy of HEW, Information Memorandum, "New Technology

Available in the Screening and Detection of Lead Poisoning and

EPSDT" (IM-77-32 (MSA)) (June 9, 1977).

27

28

15. @ coche hereto as Exhibiy S is a true and

correct copy of an excerpt from a document entitled, "HEW, A

Guide to Administration, Diagnosis and Treatment of the EPSDT

PRogram under Medicaid (1977)."

16. Attached hereto as Exhibit T is a true and

correct copy of a document entitled, "135 Cong. Rec. S 13233

(Oct. 12, 1989).

17. Attached hereto as Exhibit U is a true and

correct copy of a document entitled, "Explanation of the

Conference Committee Affecting Medicare-Medicaid Programs Re;

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989 (H.R. 3299), reprinted

in Medicare & Medicaid Guide (CCH), Extra Edition No. 603 (Dec.

15, 1989).

18. Attached hereto as Exhibit V is a true and

correct copy of a document entitled, "Letter from Charles A.

Wwoffinden, Chief of HHS Region IX Medicaid Operations Branch,

to Michael Quinn, CHDP Research Manager (April 11, 1991).

19. Attached hereto as Exhibit W is a true and

correct copy of a document entitled, "Letter from Charles A.

Wwoffinden, Chief of HHS Region IX Medicaid Operations Branch,

to Michael Quinn, CHDP Research Manager (May 7, 1991).

I declare under the penalty of perjury that the

foregoing is true. Dated this 23rd day of May 1991 in Los

Angeles, California.

Cel

rene Perkins

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibits

Declaration of Dr. John F. Rosen

Declaration of Dr. Herbert L. Needleman

CHDP Provider Information Notice #91-6 from

Director Kenneth Kizer to CHDP Providers Re:

Lead Poisoning in Children (March 12, 1991)

S. Roan, "High Number of Lead Poison Cases

Found," L.A. Times, Aug. 30, 1990, A3, col. 1

DHS, Statewide: Fiscal Year 1989-90 Ethnicity

by Age Group by Funding Source by Lead Test

(Feb. 15, 1991)

DHS, Statewide: July 1990 thru January 1991

Ethnicity by Age Group by Funding Source by

Lead Test (Feb. 15, 1991)

DHS Medical Care Statistics Section,

California’s Medical Assistance Program

Annual Statistical Report Calendar Year 1989

Tables 20 and 29)

DHS, Fiscal Year 1989-90 Provider Number by

Age Group by Funding Source by Lead Test:

County of Residence = Santa Clara (Feb. 15,

1991)

DHS, Fiscal Year 1989-90 Ethnicity by Age

Group By Funding Source by Lead Test: County

of Residence = Los Angeles (Feb. 15, 1991)

Deposition of Ruth Range (excerpts)

Deposition of Dr. Maridee A. Gregory

(excerpts)

Health Care Coverage for Children: Hearing

Before the Senate Committee on Finance, 101lst

Cong., lst Sess. 24 (statement of Kay A.

Johnson, Director, Children’s Defense Fund

Health Division) (June 20, 1989)

Report of the House Budget Committee on H.R.

3299 (Sept. 20, 1989) reprinted in Medicare &

Medicaid Guide (CCH), Extra Edition No. 596

(Oct. 5, 1989)

HCFA, State Medicaid Manual, § 5123.2(D)

(incorporating revisions contained in HCFA

transmittals of April and July 1990)

Exhibit 0 -- 3 HEW, Medical Assistance 9... § 5-70-00 et

5 seq. (June 28, 1972)

3 Exhibit P -- HCFA, State Medicaid Manual § 5122 (April

1988)

4 Exhibit Q -- HEW, A Guide to Screening-EPSDT Medicaid

5 (Chapter 21) (1974)

6 Exhibit R -- HEW, Information Memorandum, "New Technology

Available in the Screening and Detection of

. Lead Poisoning and EPSDT" (1M-77-32 (MSA))

(June 9, 1977), reprinted in Medicare &

a Medicaid Guide (CCH) 9 28,505

9 Exhibit S -- HEW, A Guide to Administration, Diagnosis and

Treatment for the EPSDT Program under

10 Medicaid (1977) (excerpts)

11 Exhibit T -- 135 Cong. Rec. 8 13233 (October 12, 19389)

12 Exhibit U -- Explanation of the Conference Committee

Affecting Medicare - Medicaid Programs Re:

13 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989

(H.R. 3299), reprinted in Medicare & Medicaid

14 Guide (CCH), Extra Edition No. 603 (Dec. 15,

1989)

15 lpxhibit V -- Letter from Charles A. Woffinden, Chief HHS

16 Medicaid Operations Branch to Michael Quinn,

CHDP Research Manager (April 11, 1991)

17 Exhibit W -- Letter from Charles A. Woffinden, Chief HHS

18 Medicaid Operations Branch, to Michael Quinn,

CHDP Research Manager (May 7, 1991)

18

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

EXHIBIT A

Py £

f {

DECLARATION OF DR. JOHN F. ROSEN

I, Dr. John F. Rosen, declare and say:

1. The facts set forth herein are personally known to me

and I have first hand knowledge of them. If called as a witness,

I could and would testify competently thereto under oath.

2. I am currently a Professor of Pediatrics at Albert

Einstein College of Medicine, where I have been on the faculty

since 1969 and Head of the Division of Pediatric Metabolism since

1980. I am the Director of Metabolism Services and Attending

Physician at Montefiore Hospital and Medical Center

("Montefiore"), located in Bronx, New York. During the past 20

years, I have conducted research, written, and consulted

extensively on matters relating to lead poisoning, and I

currently am Chairman of the United States Department of Health

and Human Services ("HHS") Centers for Disease Control’s { CDC?)

Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention, as I

was in 1985. A copy of my Curriculum Vitae is attached.

(Exhibit A hereto.)

3. At Montefiore, I direct the most comprehensive lead

poisoning prevention and research program in the United States,

involving basic research, clinical research, and clinical

service. Our Lead Poisoning Prevention Project, involving a team

of 22 health professionals, provides a bridge between medical and

environmental intervention and management. Under my supervision,

approximately 3,000 lead blood tests are conducted each year, and

i R i

more people are treated for lead poisoning than at any other

facility in the United States.

4. Childhood lead poisoning is the most common and

preventable pediatric health problems in the United States today.

According to the CDC and the Agency for Toxic Substances and

Disease Registry, lead poisoning is the number one environmental

health hazard for children in the United States. No

socioeconomic group, geographic area, or racial or ethnic

population is spared. At least three to four million children -

- one in six -- have lead levels in their blood (from lead paint

exposure alone) high enough to cause significant impairment of

their neurologic development. Experts have estimated that over

67% of black inner-city children and 17% of all children in the

United States under the age of six are at high risk for

developing lead poisoning.

5. These astonishing levels of exposure are due to the

ubiquitous nature of lead in the human environment -- in lead-

based paint and gasoline, drinking-water and pipes, printing inks

and pigments used in toys, fertilizers, lead-soldered food cans,

and soil and dust. And, because of their tendency to hand-to-

mouth activity and because of the vulnerability of the developing

central nervous system, young children are particularly

susceptible both to exposure and to lead’s toxic effects.

Although all children are at risk for lead poisoning, poor and

minority children are disproportionately affected because they

are more likely to (1) live or visit in homes with peeling or

chipping paint; (2) live or visit in homes built before 1959 with

planned or ongoing renovation; or (3) live in homes built before

1978 which may be deteriorating and still contain hazardous

quantities of leaded paint. According to the Agency for Toxic

Substances and Disease Registry’s Report to Congress (Exhibit B

hereto), approximately 52 percent of current housing stock (more

than 40 million household dwellings) still contain some 3 million

tons of leaded paint (or approximately 110 pounds per dwelling).

6. Lead is a poison that affects virtually every system in

the body. Although it is particularly harmful to the developing

brain and nervous system of young children, the adverse effects

of lead exposure on children and adults are wide-ranging. Very

severe lead exposure (70 ug/dL or greater) can cause coma,

convulsions, and even death. Lower levels cause adverse effects

on the central nervous system, kidney, reproductive system

(impotence, sterility, spontaneous abortion), and blood system

(anemia). Blood lead levels as low as 10 ug/dL are associated

with decreased intelligence and slowed neurobehavioral and

cognitive development that are likely to be irreversible. Other

effects of even low lead exposure include decreased stature and

hearing acuity, impaired biosynthesis of the active Vitamin D

metabolite and hemoglobin, and reduced serum total and ionized

calcium levels -- in other words, multiple, cascading normal

physiological systems and pathways, essential to the functioning

of many critical organs.

-” - a ’

* | é

7. Most poisoned children, however, have no symptoms. As a

2

result, the vast majority of lead poisoning cases go undiagnosed

and untreated. Because of this and the fact that early lead

toxicity has the potential to be reversible, monitoring of blood

lead levels of young children through periodic screening is

absolutely essential. Once detected, lead poisoning and related

health effects can often be treated and, in many cases, measures

can be undertaken to detect and eliminate the source of exposure.

Screening programs have had a tremendous impact on reducing the

occurrence of symptomatic lead poisoning in the United States.

Symptomatic lead poisoning almost invariably results in

irreversible, severe, and clinically evident neurological

sequelae.

8. Measuring blood lead content is the most accurate and

reliable method of screening for recent lead exposure. Blood

lead level testing is essential to adequate lead screening

programs, in part because an oral assessment of risk factors is

totally unreliable to identify toxicity in young children. Only

direct measurements of lead in blood can establish the presence

or absence of recent excessive exposure. For all children, I am

not aware of any protocol for lead screening satisfying accepted

professional standards that fails to include periodic blood lead

level tests. In my opinion, periodic screening by blood lead

measurement should be conducted at least once per year for any

child under the age of six because virtually all young children -

- especially those who are poor -- are at risk for lead

poisoning. For children considered to be at high risk for lead

exposure due to positive testing results or environmental or

other factors, blood lead testing should be conducted, at the

very least, every three to six months. To do otherwise would be

unconscionable in light of what we now know of the effects of

lead at relatively low exposure levels.

9. The CDC is currently in the process of drafting a Lead

Statement entitled "Preventing Lead Poisoning in Young Children"

(March 1991 (Draft)). As part of that process, the CDC’s

Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention in

November 1990 voted unanimously that all children be screened for

lead poisoning -- in other words, that lead screening of children

be universal -- and recommended further that screening include a

blood lead test. In my opinion, the requirement that all

Medicaid eligible children ages 1-5 be tested for lead poisoning

is reasonable, medically appropriate, and an essential part of

even a minimally adequate and medically effective lead screening

and prevention program.

Executed at Bronx, New York this ‘22day of May 1991.

I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is

ot ST

true and correct.

DR. JOHN F. ROSEN

: 1

} i

CURRICULUM VITAE

JOHN FRIESNER ROSEN, M.D.

BORN: JUNE 3, 1935, NEW YORK CITY

EDUCATION:

POST

Harvard College, 1953-1957, B.A.

Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

1957-1961, M.D.

GRADUATE TRAINING:

Montefiore Hospital and Medical Center

1961-1962, Internship

Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center

1962-1965, Resident in Pediatrics (Babies Hospital)

Rockefeller University, 1965-1967, Guest Investigator (Post

Doctoral Fellow) (Mineral Metabolism and Peptide Chemistry)

Intern - Montefiore Hospital and Medical Center, 1961-1962

Junior Resident - Babies Hospital, New York City, 1962-1964

Senior Resident - Babies Hospital, New York City, 1964-1965

PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT AND HOSPITAL APPOINTMENTS:

Assistant Physician - The Rockefeller University, 1965-1969

Guest Investigator - The Rockefeller University, 1965-1967

Research Associate - The Rockefeller University, 1967-1969

Research Collaborator - Brookhaven National Laboratory

(Departments of Medicine and Physics), 1975-Present

Chairman, Research Advisory Committee - Tandem = Van de

Graaff Facility, Brookhaven National Laboratory

Department of Physics), 1979-Present

Director, Metabolism Services

Montefiore Medical Center, 1969-Present

Head, Division of Pediatric Metabolism, Albert Einstein

College of Medicine, 1980-Present

Adjunct Attending Physician - Montefiore Hospital and Medical

Center, 1969-1974

Associate Attending Pediatrician - Montefiore Hospital and

Medical Center, 1974-1978

/

Attending Pediatrician - Montefiore Hospital and Medical

Center, 1978-Present

Assistant Professor of Pediatrics - Albert Einstein College of

o Medicine, 1969-1975

Associate Professor of Pediatrics - Albert Einstein College of

Medicine, 1975-1980

Professor of Pediatrics - Albert Einstein College of Medicine,

1980-Present

BOARD CERTIFICATION: Diplomate, American Board of Pediatrics, 1966

PROFESSIONAL SOCIETY MEMBERSHIPS:

American Chemical Society, 1967-Present

Sigma XI, 1967-Present

American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1967-

Present

American Federation for Clinical Research, 1969-Present

Fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics, 1966-Present

Harvey Society, 1966-Present

New York Academy of Sciences, 1971-Present

Society for Pediatric Research, 1972-Present

Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society, 1975-Present

American Pediatric Society, 1979-Present

American Institute of Nutrition, 1979-Present

American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, 1979-Present

Society of Toxicology, 1984-Present

OTHER PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES:

Research Committee - Montefiore Hospital and Medical Center,

1980-Present

Committee on Appointments and Promotions to Rank of Full

Professor - Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1982-1984

Peer Review Panel, Health Effects Chapters, Lead Criteria

Document, EPA - 1982-1984

Consultant and Author, E.P.A. (Washington). Writing of

Air Lead Quality Criteria Document - 1981, 1985.

Ad Hoc Member, Toxicology Study Section, Division of

Research Grants, N.I.H. - 1982-1984

Chairman, Centers for Disease Control Advisory Committee on

Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention. CDC, 1984

Member, Toxicology Study Section, Division of Research Grants,

N.1.H., 1985-1989

Member, National Academy of Science, National Research Council

Committee on Low Level Exposure in Susceptible Populations.

1989-

Chairman, Centers for Disease Control Advisory Committee on

childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention. CDC, 1990-

CURRENT GRANT SUPPORT:

1. The metabolism of lead in bone.

NIH #ES 01060-12-16

Dr. J.F. Rosen - Principal Investigator

12/01/86-11/30/96 (MERIT AWARD)

2. Treatment outcomes in moderately lead toxic children.

NIH #ES 04039-02-06

Dr. J.F. Rosen - Principal Investigator

3/1/86-4/30/92

3. A Nutritional Survey in Homeless Children.

Diamond Foundation

Dr. J.F. Rosen - Principal Investigator

1988-1992

4. Lead Poisoning Prevention Project.

Aron/JC Penney and Robert Wood Johnson Foundations

Dr. John F. Rosen - Principal Investigator

1987-1992

5. MERIT AWARDEE of the National Institute of Environmental

Health Sciences - 1986-1996 (ES 01060)

6. SAFE House (Transition Housing) For Successfully Treated

Lead Poisoned Children and Their Families.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Dr. John F. Rosen - Principal Investigator

1990-1993.

REVIEWER FOR:

American Journal of Physiology

Annals of Internal Medicine

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism

Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine

Journal of Neurochemistry

Journal of Pediatrics

Life Sciences

New England Journal of Medicine

Pediatric Research

Pediatrics

Science

Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology

® i

3 3

ARTICLES: (Selected)

l.

la.

12.

Haymovits, A.H. and Rosen, J.F.: Human thyrocalcitonin.

Endocrinology 81:993-1000, 1967.

Rosen, J.F., and Haymovits, A.H.!: Liver lysosomes in

congenital osteopetrosis: A study of lysosomal function,

calcitonin, parathyroid hormone, and 3',5' AMP. J. Peds.

81:518-527, 1972.

Rosen, J.F. and Finberg, L.: Vitamin D dependent rickets:

Actions of parathyroid hormone and 25-hydroxycholecalciferol.

Ped. Res. 6:552-562, 1972.

Rosen, J.F.: The microdetermination of blood lead in children

by flameless atomic absorption. The carbon rod atomizer. J.

Lab. and Clin. Med. 80:567-576, 1972.

Rosen, J.F. and Finberg, L.: Vitamin D dependent rickets:

Actions of parathyroid hormone and 25-hydroxycholecalciferol.

In, Clinical Aspects of Metabolic Bone Disease. Frame,

Parfitt and Duncan (Eds)., Excerpta Medica Foundation, 1973,

pp. 388-393.

Rosen, J.F.: The microdetermination of blood lead in children

by nonflame atomic absorption spectroscopy. In, Proceedings of

the Institutional Consortium on Endemic Lead Poisoning.

Clinical Toxicology Bulletin 3:111-118, 1973.

Daum, F., Rosen, J.F. and Boley, S.J.: Parathyroid adenoma,

parathyroid crisis, and acute pancreatitis in an adolescent.

J. Peds. 83:275-277, 19173.

Rosen, J.F., Zarate-Salvador, C. and Trinidad, E.E.: Plasma

lead levels in normal and lead-intoxicated children. J. Peds.

84:45-48, 1974.

Lamm, S. and Rosen, J.F.: Lead contamination in milks fed to

infants: 1972-1973. Pediatrics 53:137-141, 1974.

Rosen, J.F., Roginsky, M., Nathenson, G. and Finberg, L.: 25-

hydroxyvitamin D: Plasma levels in mothers and their premature

infants with neonatal hypocalcemia. Amer. J. Dis. Child.

1271:220~-223, 1974.

Rosen, J.F. and Trinidad, E.E.: The significance of plasma

lead levels in normal and lead-intoxicated children. Environ.

Health Perspect. 7:139-144, 1974.

Rosen, J.F. and Lamm, S.H.: Further comments on the lead

content of milks fed to infants. Pediatrics 53:144-145, 1974.

13.

14.

15,

le6.

1%.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

a3.

24.

Sorell, M. and Rosen, J.F.: Ionized calcium: Serum levels

during symptomatic hypocalcemia. J. Peds. 87:67-70, 1975.

Daum, F., Rosen, J.F., Roginsky, M., Cohen, M. and Finberg,

L.: 25-hydroxycholecalciferol in the management of rickets

associated with extrahepatic biliary atresia. J. Peds.

88:1041-1043, 1976.

Rosen, J.F. and Wexler, E.E.: Studies of lead transport in

bone organ culture. Biochem. Pharm. 26:650-652, 1977.

Rosen, J.F. and Sorell, M.: Interactions of lead, calcium,

vitamin D, and nutrition in lead-burdened children. In,

Clinical Chemistry and Chemical Toxicology of Metals. Brown,

8.8. (Ed.), Elsevier, 1977, pp. 27-31.

Rosen, J.F., Fleischman, A.R., Finberg, L., Eisman, J. and

DeLuca, H.F.? 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol: Oral

administration and sterol levels in the long-term management

of idiopathic hypoparathyroidism in children. In, Vitamin D:

Biochemical, Chemical and Clinical Aspects Related to Calcium

Metabolism. Norman, A.W. et al (Eds.) Walter de Gruyter,

Berlin, 1977, pp. 827-830.

Sorell, M., Rosen, J.F., and Roginsky, M.: Interactions of

lead, calcium, vitamin D and nutrition in 1lead-burdened

children. Arch. Environ. Health 32:160-164, 1977.

Rosen, J.F., Fleischman, A.R., Finberg, L., Eisman, J., and

DeLuca, H.F.: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D;: Its use in the long-

term management of idiopathic hypoparathyroidism in children.

J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 45:457-468, 1977.

Rosen, J.F., Wolin, D. and Finberg, L.: Immobilization

hypercalcemia after single limb fractures in children and

adolescents. Amer. J. Dis. Child. 132:560-564, 1978.

Fleischman, A.R., Rosen, J.F., and Nathenson, G.: 25-

hydroxyvitamin D: Serum levels and oral administration in

neonates. Arch. Int. Med. 138:869-873, 1978.

Fleischman, A.R., Rosen, J.F., and Nathenson. G.: Oral 25-

hydroxycholecalciferol for the prevention of early neonatal

hypocalcemia in premature neonates. Amer. J. Dis. Child.

132:973-977, 1978.

Rosen, J.F., Fleischman, A.R., Finberg, L., Hamstra, A., and

DeLuca, H.F.: Rickets with alopecia: An inborn error of

vitamin D metabolism. J. Peds. 94:729-735, 1979.

Fleischman, A.R., Rosen, J.F., Nathenson, G. and Finberg, L.:

Oral 25-OHD in preventing neonatal hypocalcemia. In,

Pediatric Diseases Related to Calcium. Anast, DeLuca

(Eds.) ,Elsevier, 1980, pp. 345-354.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

ny ™

3 3

Chesney, R.W., Rosen, J.F., Hamstra, A. and Deluca, H.F.:

Serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels in normal children and in

vitamin D disorders. Amer. J. Dis. Child. 134:135-139, 1980.

Rosen, J.F., Chesney, R.W., Hamstra, A., Deluca, H.F. and

Mahaffey, K.R.: Reduction in 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in

children with increased lead absorption. New Engl. J. Med.

302:1128-1131, 1980.

Rosen, J.F., and Markowitz, M.: D-Penicillamine: Its actions

on lead transport in bone organ culture. Ped. Res. 14:330-

335, 1980.

Fleischman, A.R., Rosen, J.F., Smith, C.M. and Deluca, H.F.:

Maternal and fetal levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels at

term. J. Peds. 97:640-642, 1980.

Sorell, M., Rosen, J.F., Kapoor, N., Rirkpatrick, D., Raju

S.K., Chaganti, Good, R.A., and O'Reilly, R.J.: Marrow

transplantation for juvenile osteopetrosis. Amer. J. Med.

70:1280-1287, 1981}.

Chesney, R.W., Rosen, J.F., Smith, C.M. and DeLuca, H.F.:

Absence of seasonal variation in serum concentrations of 1,25-

dihydroxyvitamin D despite a rise in 25-hydroxyvitamin D in

summer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 53:139-142, 1981.

Eil, C., Liberman, U.A., Rosen, J.F., and Marx, S.J.: A

cellular defect in hereditary vitamin D-dependent rickets Type

II: Defective nuclear uptake of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in

cultured skin fibroblasts. New Engl. J. Med. 304:1588-1591,

1981. :

Rosen, J.F., Chesney, R.W., Hamstra, A., and DeLuca, H.F.:

Reduction in 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in children with

increased lead absorption. In, Chemical Indices and

Mechanisms of Organ-Directed Toxicity. Brown, S$.8. {£d4.),

Pergamon Press, 1981, pp. 91-95.

Rosen, J.F.: The metabolism of lead-210 in isolated bone

cells. In, Chemical Indices and Mechanisms of Organ-Directed

Toxicity. Brown, S.S. (Ed.), Pergamon Press, 1981, pp. 305-

310.

Saenger, P., and Rosen, J.F.: 68-hydroxycortisol: A non-

invasive probe to evaluate inhibitory effects of lead on drug

metabolism in children. In, Chemical Indices and Mechanisms

of Organ-Directed Toxicity. Brown, S.S. (Ed.), Pergamon

Press, 1981, pp. 297-303.

Markowitz, M.E., Rotkin, L., and Rosen, J.F.: Circadian

rhythms of blood minerals in humans. Science 213:672-674,

1981.

® (1)

Rosen, J.F., Kraner, H.W., and Jones, K.W.: Effects of

CaNa,EDTA on lead and trace metal metabolism in bone organ

culture. Tox. Appl. Pharm. 64:230~-236, 1982.

Saenger, P., Rosen, J.F., and Markowitz, M.E.: The diagnostic

significance of EDTA testing in children with increased lead

absorption. Amer. J. Dis. Child. 136:312-315, 1982.

Wielopolski, L., Rosen, J.F., Slatkin, D., and Cohn, S.: Non-

invasive L-X-ray fluorescence analysis of lead in the human

tibia. Medical Physics 10:248-251, 1983.

Wisniewski, K.E., French, J.H., Rosen, J.F., Kozlowski, P.,

Tenner, M. and Wisniewski, N.H.: Basal ganglia calcification

(BGC) in Down's syndrome (DS)-another manifestation of

premature aging. Annals New York Acad. Sci. 396:179-192,

1982.

Mahaffey, K.R., Rosen, J.F., Chesney, R.W., Peeler, J.R.,

Smith, C.M. and DeLuca, H.F.: Association between age, blood

lead concentration, and serum 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol

levels in children. Am. J. Clin. Nutrition 35:1327-1331,

1981.

Markowitz, M.E., Rosen, J.F., Smith, C.M., and DeLuca, H.F.:

1-25-Dihydroxyvitamin D;-treated hypoparathyroidism: 35

patient years in 10 children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.

55:727-733, 1982.

Rosen, J.F.: The metabolism of lead in isolated bone cell

populations: Interactions between lead and calcium.

Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 71:101-112, 1983.

Liverman, U.A., Ei}, C., Holst, P., Singer, F., Rosen, J.F.,

and Mary, S.J. Hereditary resistance to 1,25~

dihydroxyvitamin D: Defective function of receptors for 1,25-

dihydroxyvitamin D in cells cultured from bone. J.: Clin.

Endocrinol. 57:958-962, 1983.

Rosen, J.F.: Interactions between lead and calcium in

isolated bone cell populations. In, Clinical Chemistry and

Chemical Toxicity of Metals. Bronx, S.S. (Ed.), Academic

Press, 1983, pp. 247-250.

Saenger, P., Markowitz, M.E., and Rosen, J.F.: Depressed

excretion of 6g-hydroxycortisol in lead-toxic children. J.

Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 58:363-367, 1984.

Markowitz, M., Rosen, J.F., and Mizruchi, M.: Circadian and

ultradian rhythms of blood minerals during adolescence.

Pediatr. Res. 18:456-462, 1984.

CB a ;

Markowitz, M.E. and Rosen, J.F.: Assessment of body lead

stores in children: Validation of an 8-hour CaNa,EDTA

provocative test. J. Peds. 104:337-342, 1984.

Gundberg, C., Markowitz, M.E., and Rosen, J.F.: Osteocalcin

in human serum: A circadian rhythm. J. Clin. Endocrinol.

Metab. 60:737-739, 1985.

Markowitz, M.E., Rosen, J.F. and Mizruchi, M.: Circadian

variations in serum zinc concentrations: correlation with

blood ionized calcium serum total calcium and phosphate in

humans. Amer. J. Clin. Nut. 41:689-696. 1985.

Markowitz, M.E., Rosen, J.F. and Mizruchi, M.: Effects of

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; administration on circadian minerals

rhythms in humans. Calcif. Tiss. Internat. 37: 351-356, 1985.

Markowitz, M.E. Rosen, J.F., Holick, M.F., Hannifan N. an

Endres, D.: Time-related variations in serum 1,25-

dihydroxyvitamin D concentrations in humans. In, Vitamin D:

Biochemical Chemical and Clinical Aspects. Normal, A. (Ed.),

W. de Gruyter, Berlin, 1985, pp. 249-251.

Pounds, J.G. and Rosen, J.F.: The cellular metabolism of

lead: A kinetic analysis in cultured osteoclastic bone cells.

Tox. Appl. Pharmacol. 83:531-545, 1986.

Markowitz, M.E., Gundberg, C., and Rosen, J.F.: A rapid rise

in serum osteocalcin following 1,25-(OH),D; administration in

normal adults. Calcif. Tiss. Internat. 40:179-183, 1987.

Rosen, J.F. and Pounds, J.G.: The cellular metabolism of lead

and calcium: A kinetic analysis in cultured osteoclastic bone

cells. Contributions to Nephrology 64:64-71, 1988.

Pounds, J.G. and Rosen, J.F.: Cellular Ca" homeostasis and

Ca™-mediated cell processes as critical targets for toxicant

action; Conceptual and methodological pitfalls. Toxicology and

Applied Pharmacology 94:331-341, 1988.

Morris, V., Markowitz, M.E., and Rosen, J.F.: Serial

measurements of ALA dehydratase in lead toxic children. J.

Pediatrics 112:916-919, 1988.

Markowitz, M.E., Rosen, J.F., Arnaud, S.B., Thorpy, M. and

Laxminarayan, S.: Temporal interrelationships between the

circadian rhythms of serum parathyroid hormone and calcium

concentrations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 67:1068-1073,

1988.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

® @

Rosen, J.F., Markowitz, M.E., Bijur, P.E., Jenks, 85.T.,

Wielopolski, L., Kalef-Ezra, J.A. and Slatkin, D.N.: L-x-ray

fluorescence of cortical bone lead compared with the CaNa,EDTA

test in lead-toxic children: Public health implications.

Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. (USA). 86:685-689, 1989.

Rosen, J.F. and Pounds, J.G.: Quantitative interactions

between lead and calcium in osteoclastic bone cells. Toxicol.

Appl. Pharmacol. 98:530-543, 1989.

Wielopolski, L., Kalef-Ezra, J., Slatkin, D.N. and Rosen,

J.F.: Polarized L-x-ray fluorescence to measure cortical bone

lead. Medical Physics 16:521-529, 1989.

Markowitz, M.E., Fishman, K., Rosen, J.F., and Saenger, P.:

Effects of growth hormone therapy on circadian osteocalcin

rhythms in idiopathic short stature. J. Clin. Endocrinol.

Metab. 69:420-425, 1989.

Schanne, F.A.X., Dowd, T.L., Gupta, R.K. and Rosen, gsFe?

Lead increases free ca? concentration in cultured osteoblastic

bone cells: Simultaneous detection of intracellular free pPb%*

by 9F NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA). 86:5133-5135, 1989.

Long, G.J., Rosen, J.F., and Pounds, J.G.: Cellular lead

toxicity and metabolism in primary and clonal osteoblastic

bone cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 102:346-361, 1990.

Fullmer, C.S. and Rosen, J.F.: Effect of dietary calcium and

lead states on intestinal calcium absorption. Environ. Res.

51:91-99, 1990.

Markowitz, M.E., Rosen, J.F., and Bijur, P.E.: Effects of

iron deficiency on lead metabolism in moderately lead toxic

children. J. Pediatr. 116:360-364, 1990.

Kalef-Ezra, J.A., Slatkin, D.N., Rosen, J.F. and Wielopolski,

L.: Radiation risk to the human conceptus attributable to

measurement of maternal tibial bone lead by L-line x-ray

fluorescence. Health Physics 58:217-219, 1990.

Schanne, F.A.X. Dowd, T.L., Gupta, R.K. and Rosen, J.F.:

Development of 9F NMR for measurements of [Ca?*] and [Pb®] in

cultured osteoblastic bone cells. Environmental Health

Perspectives, 84:99-106, 1990.

Rosen, J.F., Markowitz, M.E., Bijur, P.E., Jenks, S.T.,

Wielopolski, L., Kalef-Ezra, J.A. and Slatkin, D.N.:

Sequential measurements of bone lead content by L-x-ray-

fluorescence in CaNa.EDTA-treated lead-toxic «children.

Environmental Health Perspectives, In press, 1990.

69.

70.

71.

® i i

Long, G.J., Pounds, J.G. and Rosen, J.F.: Lead impairs the

hormonal regulation of osteocalcin in rat osteosarcoma (ROS

17/2.8) cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., In press, 1990.

Schanne, F.A.X., Dowd, T.L., Gupta, R.J., and Rosen, JeF.$

Differential effects of lead on parathyroid hormone-induced

changes in clonal osteoblastic bone cells using '’F NMR.

Biochim. Biophys. Acta., 1054:250-255, 1990.

Dowd, T.L., Rosen, J.F., and Gupta, R.K.: 3p NMR and

saturation transfer studies of the effect of lead on cultured

osteoblastic bone cells. J. Biol. Chem., In press, 1990.

10

® 3

REVIEWS:

1.

10.

11.

12.

Haymovits, A.H. and Rosen, J.F.: Calcitonin: Its nature and

role in man. Pediatrics 45:133-149, 1970.

Haymovits, A.H. and Rosen, J.F.: Calcitonin in metabolic

disorders. In, Advances in Metabolic Disorders. Levine, R.

and Luft. R. (Eds.), 6:177-212, 1972.

Rosen, J.F. and Finberg, L.: The real and potential uses of

new vitamin D; analogues in the management of metabolic bone

disease in intants and children. In, Nutritional Imbalances

in Infant and Adult Disease. Seelig, M. (Ed.), Spectrum,

1977, Pp. 87-102.

Rosen, J.F.: The metabolism and subclinical effects of lead in

children. In, The Biogeochemistry of Lead in the Environment.

Nriagu, J.0. (Ed.), Elsevier/North Holland, 1978, pp. 151-172.

Chesney, R.W., Rosen, J.F., Hamstra, A., Mazess, R.B. and

Deluca, H.F.: The use of serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D

(Calcitriol) concentrations in the clinical assessment of

demineralizing disorders in children. In, Hormonal Control of

Calcium Metabolism. Excerpta, 1981, pp. 252-260.

Markowitz, M.E. and Rosen, J.F.: Mineral interactions in

health and disease. In, Pediatric Update. Moss, A. (Ed.),

Elsevier, 1982, pp. 97-114.

Rosen, J.F. and Chesney, R.W.: Circulating calcitriol

concentrations in health and disease. J. Peds. 103:1-17, 1983

(Medical Progress Article).

Chesney, R.W., Rosen, J.F., and DeLuca, H.F.: Disorders of

calcium metabolism in children. In, Recent Progress in

Pediatric Endocrinology, Raven Press, 1983, pp. 5-24.

Rosen, J.F.: Nuclear analytical methods and heavy metals -

real and potential applications in the biomedical sciences.

Neurotoxicology 4:218-219, 1983.

Piomelli, S., Rosen, J.F., and Chisolm, J.J. Jr.: Treatment

guidelines for the management of childhood lead poisoning. J.

Pediatrics 105:523-532, 1984.

Rosen, J.F.: Lead and the vitamin D-endocrine system. In,

Air Quality Criteria For Lead. Grant, L. and Davis, M.

(Eds.), Volume 4, Chapter 12, 1984, pp. 42-47.

Rosen, J.F.: Metabolic and cellular effects of lead: A guide

to low level lead toxicity in children. In, Dietary and

Environmental Lead Exposure. Mahaffey, K.R. (Ed.), Elsevier,

1985, Pp. 157-185,

11

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

Rosen, J.F.: An overview of metabolic effects of lead in

children. In, Health Effects of Lead. Hotz, M. (Ed.), Royal

Society of Canada, Commission on Lead in the Environment,

1986, pp. 203-224.

Needleman, H.L., Rosen, J.F., Piomelli, S., Landrigan, P. and

Graef, J.: The hazards of benign neglect of elevated blood

lead levels. Amer. J. Dis. Child. 141:941-942, 1987.

Rosen, J.F.: The toxicological importance of lead in bone:

The evolution and potential uses of bone lead measurements by

x-ray fluorescence to evaluate treatment outcomes in

moderately lead toxic children. In, Biological Monitoring of

Toxic Metals. Clarkson, T. (Ed.), Plenum Press, 1988, pp.

603-621.

Rosen, J.F.: Metabolic abnormalities in lead-toxic children:

Public health implications. Bull. New York Acad. 65:1067-1084,

1989.

Rosen, J.F., Novak, R.F. and Galvin, M.J.: The calcium

messenger system: Implications for toxicological research.

Environmental Health Perspectives, 84:3-5, 1990.

Pounds, J.G., Long, G., and Rosen, J.F.: The toxicology of

lead in bone. Environ. Health Perspectives, In press, 1990.

Rosen, J.F., and Pounds, J.G. The metabolism of lead in bone.

CRC Review in Toxicology, In preparation, 1990.

12 A

The Nature and Extent of

Lead Poisoning in Children

in the United States:

A Report to Congress

July 1988

PART 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Exposure to lead continues to be a serious public health problem --

particularly for the young child and the fetus. The primary target organ for

lead toxicity is the brain or central nervous system, especially during early

child development. In children and adults, very severe exposure can cause

coma, convulsions, and even death. Less severe exposure of children can produce

delayed cognitive development, reduced IQ scores, and impaired hearing -- even

at exposure levels once thought to cause no harmful effects. Depending on the

amount of lead absorbed, exposure can also cause toxic effects on the kidney,

impaired regulation of vitamin D, and diminished synthesis of heme in red blood

cells. All of these effects are significant. Furthermore, toxicity can be

persistent, and effects on the central nervous system (CNS) may be irreversible.

In recent years, a growing number of investigators have examined the

effects of exposure to low levels of lead on young children. The history of

research in this field shows a progressive decline in the lowest exposure

levels at which adverse health effects can be reliably detected. Thus, despite

some progress in reducing the average level of lead exposure in this country,

it is increasingly apparent that the scope of the childhood lead poisoning

problem has been, and continues to be, much greater than was previously

realized.

The "Nature and Extent of Lead Poisoning in Children in the United States:

A Report to Congress" was prepared by the Agency for Toxic Substances and

Disease Registry (ATSDR) in compliance with Section 118(f) of the 13986

Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA) (42 U.S.C. 9618(f)). This

Executive Summary is a guide to the structure of the document and, in partic-

ular, to the organization of the responses to the specific directives of

Section 118(f). It also provides an overview of issues and directions to the

U.S. lead problem.

® p

The report comprises three parts: Part 1, consisting of the Executive

Summary; Part 2, consisting of Chapter I. "Report Findings, Conclusions, and

Overview," which provides a more detailed overview of information and conclu-

sions abstracted from the main body of the report; and Part 3, consisting of

Chapters II through XI, which constitute the main body of the report.

Before addressing the specific directives of Section 118(f), it is

important to point out that childhood lead poisoning is recognized as a major

public health problem. In a 1987 statement, for example, the American Academy

of Pediatrics notes that lead poisoning is still a significant toxicological

hazard for young children in the United States. It is also a public health

problem that is preventable.

In recognition of evolving scientific evidence of the harmful effects of

lead exposure, Congress directed ATSDR to examine (1) the long-term health

implications of low-level lead exposure in children; (2) the extent of low-

level lead intoxication in terms of U.S. geographic areas and sources of lead

exposure; and (3) methods and strategies for removing lead from the environment

of U.S. children.

The childhood lead poisoning problem encompasses a wide range of exposure

levels. The health effects vary at different levels of exposure. At low

levels, the effects on children, as stated subsequently in this report, may not

be as severe or obvious, but the number of children adversely affected is

large. Moreover, as adverse health effects are detected at increasingly lower

levels of exposure, the number of children at risk increases. At intermediate

exposure levels, the effects are such that a sizable number of U.S. children

require medical and other forms of attention, but usually they do not need to

be hospitalized, nor do they need conventional medical treatment for lead

poisoning. For these children, the only appropriate solution, at present, is

to eliminate or reduce all significant sources of lead exposure in their

environment. At high levels, the effects are such that children require

immediate medical treatment and follcw-up. Various clinics and hospitals,

particularly in larger cities, continue to report such cases.

Lead exposure may be characterized in terms of either external or internal

concentrations. External exposure levels are the concentrations of lead in

environmental media such as air or water. For internal exposure, the most

widely accepted and commonly used measure is the concentration of lead in

blood, conventionally denoted as micrograms of lead per deciliter (100 ml) of

whole blood -- abbreviated pg/dl. For example, when ATSDR estimated the number

2

@ Q

of children considered to be at risk for adverse health effects, the Agency

used blood lead (Pb-B) levels of 25, 20, and 15 pg/dl to group children by their

degree of exposure.

These levels are not arbitrary. In 1985 the Centers for Disease Control

(CDC) identified a Pb-B level of 25 pg/dl along with an elevated erythrocyte

protoporphyrin level (EP) as evidence of early toxicity. For a number of

practical considerations, CDC selected this level as a cutoff point for medical

referral from screening programs, but it did not mean to imply that Pb-B levels

below 25 pg/dl are without risk. More recently, the World Health Organization

(WHO), in its 1986 draft report on air quality guidelines for the European

Economic Community, identified a Pb-B level of 20 pg/dl as the then-current

upper acceptable limit. In addition, the Clean Air Scientific Advisiory Commit-

tee to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has concluded that a Pb-B

level of 10 to 15 pg/dl in children is associated with the onset of effects that

“may be argued as becoming biomedically adverse". In this connection, the

available evidence for a potential risk of developmental toxicity from lead

exposure of the fetus in pregnant women also points towards a Pb-8 level of 10

to 15 pg/dl, and perhaps even lower. These various levels represent an evolving

understanding of low-level lead toxicity. They provide a reasonable means of

quantifying aspects of the childhood lead poisoning problem as it is currently

understood. With further research, however, these levels could decline even

further.

A. RESPONSE TO DIRECTIVES OF SECTION 118(f) of SARA

Section 118(f) and its five directives give ATSDR the mandate to prepare

this report. These directives are identified in the five subsections below.

1. Section 118(f)(1)(A)

This subsection requires an estimate of the total number of children,

arrayed according to Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA) or other

appropriate geographic unit, who are exposed to environmental sources of lead

at concentrations sufficient to cause adverse health effects. Chapter V,

"Examination of Numbers of Lead-Exposed Children by Areas of the United

States," and Chapter VII, "Examination of Numbers of lLead-Exposed Women of

Childbearing Age and Pregnant Women," respond to this directive.

3

i

w » |

Valid estimates of the total number of lead-exposed children according to

SMSAs or some other appropriate geographic unit smaller than the Nation as a

whole cannot be made, given the available data. The only national data set for

Pb-B levels in children comes from the National Health and Nutrition Examina-

tion Survey II (NHANES II) of CDC's National Center for Health Statistics. The

NHANES II statistical sampling plan, however, does not permit valid estimates

to be made for geographic subsets of the total data base.

In this report, the numbers of white and black children (ages 6 months to

5 years) living in all SMSAs are quantified according to selected blood lead

levels and 30 socioeconomic and demographic strata. Within large SMSAs (those

with over 1 millfon residents each) for 1984, an estimated 1.5 million children

had Pb-B levels above 15 pg/dl. In smaller SMSAs (with fewer than 1 million

residents), an estimated 887,000 children had Pb-B levels above 15 pg/dl.

In short, about 2.4 million white and black metropolitan children, or

about 17X of such children in U.S. SMSAs, are exposed to environmental sources

of lead at concentrations that place them at risk of adverse health effects.

This number approaches 3 million black and white children if extended to the

entire U.S. child population. If the remaining racial categories are included

in these totals, between 3 and 4 million U.S. children may be affected. The

numbers of children in SMSAs with blood lead levels above 20 and 25 pg/d) are

715,000 (5.2) and 200,000 (1.5X), respectively. These figures, however, are

for all strata combined; many strata (e.g., black. inner-city, or low-income)

have much higher percentages of children with elevated Pb-B levels.

Although these projected figures, based on the NHANES II survey, provide

the best estimate that can now be made, they were derived from data collected

in 1976-1980 (the years of NHANES II) and extrapolated to 1984. With respect

to bounds to the above projections, variables in the methods used to generate

these figures contribute to both overestimation and underestimation. The major

source of overestimation is the unavoidable omission of declines in food lead

that may have occurred in the interval 1978-1964 and that would have affected

the results of the projection methodology. On the other hand, two significant

factors contribute to underestimation. One is the restriction of the estimates

to the SMSA fraction of the U.S. child population, some 75% to 80% of the total

population. The other is the unavoidable omission of children of Hispanic,

Asian, and other origins in the U.S. population. In a number of SMSAs in the

West and South west, children in such segments outnumber black children. In

balancing all sources of overestimates and underestimates, including variance

4

® ®

in the projection mode) itself, the projections given are probably close to the

actual values. |

A breakdown of the above estimates according to national socioeconomic and

demographic strata shows that no economic or racial subgrouping of children is

exempt from the risk of having Pb-B levels sufficiently high to cause adverse

health effects. Indeed, sizable numbers of children from families with incomes

above the poverty level have been reported with Pb-B levels above 15 pg/dl.

Nevertheless, the prevalence of elevated Pb-B levels in inner-city, underprivi-

leged children remains the highest among the various strata. Although the

percentage of children with elevated Pb-B levels is not as high in, for example,

the more affluent segment of the U.S. population living outside central cities,

the total number of children with these demographic characteristics is much

greater than the number of poor, inner-city children. Consequently, the

absolute numbers of children with elevated Pb-B levels are roughly equivalent

for some of these rather different strata of the U.S. child population.

In this report, ATSDR has also used data from lead screening programs and

1980 U.S. Census data on age of housing to estimate SMSA-specific numbers of

children exposed to lead-based paint. In December 1986, ATSDR conducted a

survey of lead screening programs. Of 785,285 children screened in 1985,

11,739 (1.5%) had symptoms of lead toxicity by one of two definitions. Because

CDC criteria for lead toxicity changed in 1985, some programs were still using

the 1978 CDC criteria (Pb-B 230 pg/d) and EP 250 pg/dl) in 1985, whereas others

used the new 1985 CDC criteria (Pb-B 225 pg/dl and EP 235 pg/dl).

Differences in the estimates of children with lead toxicity become

apparent when using the NHANES II data and the childhood lead screening program

data. Estimates derived from screening program data very likely underestimate

the actual magnitude of childhood lead exposure by a considerable margin. This

is especially evident when the percentages of positive test results from

screening programs are compared with the much higher NHANES II prevalences of

elevated Pb-B levels in strata corresponding to screening program target

groups, for example, poor, inner-city children in major metropolitan areas.

An analysis of 318 SMSAs, based on 1980 Census data on age of housing,

showed that 35 SMSAs had 50% or more of the children living in housing built

before 1950. A total of 4,374,600 children (from these 318 SMSAs alone) lived

in pre-1950 housing. The percentage of these children with lead exposures

sufficient to cause adverse health effects could not be estimated, but the

older housing in which they live is likely to contain paint with the highest

levels of lead and is, therefore, likely to pose an elevated risk of dangerous

lead exposure. A noteworthy finding concerns the distribution of children in

older housing according to family income. Actual enumerations (not estimates)

show that children above the poverty level constitute the largest proportion of

children who reside in older housing. The implication, consistent with the

conclusion based on projections from NHANES II data that was stated above, is

that children above the poverty level are not exempt from lead exposure at

levels sufficient to place them at risk for adverse health effects. Children

above the poverty level are the most numerous group within the U.S. child

population.

Although Section 118(f)(1)(A) does not explicitly request such information,

an accurate description of the full childhood lead poisoning problem requires

an estimate of the number of fetuses exposed to lead in utero, given the

susceptibility of the fetus to low-level lead-induced disturbances in develop-

ment that first become evident at birth or even some time later during early

childhood. Accordingly, in a given year, an estimated 400,000 fetuses (within

SMSAs alone) are exposed to maternal Pb-B levels of more than 10 pg/dl and are

therefore at risk for adverse health effects. This number pertains to a single

year; the cumulative number of children who have been exposed to undesirable

levels of lead during their fetal development is much greater, particularly in

view of the higher average levels of exposure that prevailed in past years.

2. Section 118(f)(1)(B)

This subsection requires an estimate of the total number of children

exposed to environmental sources of lead arrayed according to source or source

types. Chapters VI ("Examination of Numbers of Lead-Exposed Children in the

United States by Lead Source") and VIII ("The Issue of Low-Level Lead Sources

and Aggregate Lead Exposure of Children in the United States") respond to this

directive.

The six major environmental sources of lead are paint, gasoline, stationary

sources, dust/soil, food, and water. Dust/soil is more properly classified as

a pathway rather than a source of lead, but since it is often referred to as a

source, it is included. (Figure 11-1 in the main report shows how lead from

these sources reaches children.) The complex and interrelated pathways from

® @®

these sources to children severely complicate efforts to determine source-

specific exposures. Consequently, exact counts of children exposed to specific

sources of lead do not exist.

The first step in approximating the number of children exposed to lead

from each of the six major sources is to define what constitutes exposure. For

each lead source, approximate exposure categories are defined and range from

potential exposures through actual exposures known to cause lead toxicity.

Because the type and availability of data for each lead source vary consider-

ably, definitions of exposure categories also differ for each lead source. The

total numbers of children estimated for each source and category are therefore

not comparable and cannot be used to rank the severity of the lead problem by

source of exposure in a precise, quantitative way. Furthermore, because of the

nature of methods used to calculate the numbers of children in these exposure

categories, it is not possible to provide estimate errors. Some numbers are

best estimates, but others may represent upper bounds or lower bounds.

One should not overlook the limitations and caveats for these calculations,

lest the estimates be misinterpreted and misapplied. In addition, source-based

exposure estimates of children have different levels of precision. The

estimated number of children potentially exposed to a given lead source at any

level is necessarily greater than the number actually exposed at a level

sufficient to produce a specified Pb-B value. Source-specific estimates of

potentially and actually exposed children, based on the best available informa-

tion and reasonable assumptions, are summarized as follows:

) For leaded paint, the number of potentially exposed children

under 7 years of age in all housing with some lead paint at

potentially toxic levels is about 12 million. About 5.9 million

children under 6 years of age live in the oldest housing, that

is, housing with the highest lead content of paint. For the

oldest housing that is also deteriorated, as many as 1.8 to

2. 0 million children are at elevated risk for toxic lead expo-

sure.

The number of young children likely to be exposed to enough

paint lead to raise their Pb-B levels above 15 pg/dl is esti-

mated to be about 1.2 million.

0 An estimated 5.6 millfon children under 7 years old are poten-

tially exposed to lead from gasoline at some level.

Actual exposure of children to lead from gasoline, was projec-

ted, for 1987, to affect 1.6 million children up to 13 years of

age at Pb-B levels above 15 pg/dl.

7

The estimated number of children potentially exposed to U.S.

stationary sources (e.g., smelters) is 230,000 children.

The estimated number of children exposed to lead emissions from

primary and secondary smelters sufficient to elevate Pb-B concen-

trations to toxic levels is about 13,000; estimates for other

stationary sources are not available.

The number of children potentially exposed to lead in dust and

soil can only be derived as a range of potential exposures to

the primary contributors to lead in dust and sofl, namely, paint

lead and atmospheric lead fallout. This range is estimated at

5.9 million to 11.7 million children. :

The actual nusber of children exposed to lead in dust and soil

at concentrations adequate to elevate Pb-B levels cannot be

estimated with the data now avajlable.

Because of lead in old residential plumbing, 1.8 million chil-

dren under 5 years old and 3.0 million children 5 to 13 years

old, are potentially exposed to lead; for new residences (less

than 2 years old), the corresponding estimates of children are

0.7 and 1.1 million, respectively.

Some actual exposure to lead occurs for an estimated 3.8 million

children whose drinking water lead level has been estimated at

greater than 20 pg/1.

EPA, in a recent study, estimated that 241,000 children under

6 years old have Pb-B levels above 15 pg/dl because of elevated

concentrations of lead in drinking water. Of this number, 100

have Pb-B levels above 50 pg/dl, 11,000 have Pb-B levels between

30 and S50 pg/dl, and 230,000 have Pb-B levels between 15 and

30 pg/dl.

Most children under 6 years of age in the U.S. child population

are potentially exposed to lead in food at some level.

Actual exposure to enough lead in food to raise Pb-B levels to

an early toxicity risk level has been estimated to impact as

many as 1 million U.S. children.

Despite limitations in the precision of the above estimates, relative

judgments can be made about the impact of different exposure sources. Some key

findings are:

As persisting sources for childhood lead exposure in the United

States, lead in paint and lead in dust and soil will continue as

major problems into the foreseeable future.

po

0 As a significant exposure source, leaded paint is of particular

concern since it continues to be the source associated with the

severest forms of lead poisoning.

0 Lead levels in dust and soil result from past and present inputs

from paint and air lead fallout and can contribute to signifi-

cant elevations in children's body lead burden (i.e., the

accumulation of lead in body tissues).

] In large measure, paint and dust/soil lead problems for children

are problems of poor housing and poor neighborhoods.

0 Lead in drinking water is a significant source of lead exposure

in terms of its pervasiveness and relative toxicity risk. Paint

and dust and soil lead are probably more intense sources of

exposure.

0 Greater attention must be paid to lead exposure sources away

from the home, especially lead in paint, dust, soil, and drink-

ing water in and around schools, kindergartens, and similar

locations.

0 The phasing down of lead in gasoline has markedly reduced the

number of children impacted by this source as well as the rate

at which lead from the atmosphere is deposited in dust and soil.

0 Lead in food has been reduced to a significant degree in recent

years and contributes less to body burdens in the United States

than in the past.

0 Significant exposure of unkown numbers of children can also

occur under special circumstances: renovation of old houses

with lead-painted surfaces, secondary exposure to lead trans-

ported home from work places, lead-glazed pottery, certain folk

medicines, and a variety of others unusual sources.

3. Section 118(f)(1)(C)

This subsection requires a statement of the long-term consequence for

public health of unabated exposure to environmental sources of lead.

Chapters 111 ("Lead Metabolism and Its Relationship to lead Exposure and

Adverse Effects of Lead") and IV ("Adverse Health Effects of Lead") address

this issue.

Infants and young children are the subset of the U.S. population considered

most at risk for excessive exposure to lead and its associated adverse health

effects. In addition, because lead is readily transferred across the placenta,

the developing fetus is at risk for lead exposure and toxicity. For this

reason, women of childbearing age are also an identifiable, albeit surrogate,

9

subset of the population of concern, not because of direct risk to their

health, but because of the vulnerability of the fetus to lead-induced harmful

effects.

Direct, significant impacts of lead on target organs and systems are

evident across a broad range of exposure levels. These toxic effects may range

from subtle to profound. In this report, the primary focus has been on effects

that are chronic and that are induced at levels of lead exposure not uncommon

in the United States. Cases of severe lead poisoning are, however, still being

reported, particularly in clinics in our major cities.

The primary target organ for lead toxicity is the brain or central nervous

system (CNS), especially during early child development. Other key targets

in children are the body heme-forming system, which is critical to the

production of heme and blood, and the vitamin D regulatory system, which

involves the kidneys and plays an important role in calcium metabolism. Some

of the major health effects of lead and the lowest-observed-effect levels (in

terms of Pb-B concentrations) at which they occur can be summarized as follows:

0) Very severe lead poisoning with CNS involvement commonly

includes coma, convulsions, and profound, irreversible mental

retardation and seizures, and even death. Poisoning of this

severity occurs in some persons at Pb-B levels as low as

80 pg/dl. Less severe but still serious effects, such as

peripheral neuropathy and frank anemia, may start at Pb-B levels

between 40 and 80 pg/dl.

0 Numerous epidemiologic studies of children have related lower

levels of lead exposure to a constellation of impairments in CNS

function, including delayed cognitive development, reduced IQ

scores, and impaired hearing. For example, peripheral nerve

dysfunction (reduced nerve conduction velocities) have been

found at Pb-B levels below 40 pg/dl in children. In addition,

deficits in IQ scores have been established at Pb-B levels below

25 pug/dl. Preliminary data suggest that effects on one test of

children's intelligence may be associated with childhood Pb-8

levels below 10 pg/dl.

0 Adverse impacts on the heme biosynthesis pathway and on vitamin

D and calcium metabolism, all of which have far-reaching physio-

logical effects, have been documented at Pb-B levels of 15 to

20 pg/dl in children. At levels around 40 pg/dl, the effects on

heme synthesis increase in number and severity (e.g., reduced

hemoglobin formation).

0 Of particular concern are consistent findings from several

recent. longitudinal cover a period of years epidemiologic

studies showing low-level lead effects on fetal and child

development, including neurobehavioral and growth deficits.

10

® @®

These effects are associated with prenatal exposure levels of 10

to 15 pg/dl.

With regard to the long-term consequences of lead exposure during early

development, the American Academy of Pediatrics (1987) has noted that utmost

concern should be given to the irreversible neurological consequences of

childhood lead poisoning. Recent findings from longitudinal follow-up studies

of infants starting at birth (or even before birth) show persistent deficits in

mental and physical development through at least the first two years of life as

a function of low-level prenatal lead exposure. It {is not yet known, however,

whether deficits fn later childhood development will continue to show a signif-

icant linkage to prenatal exposure or whether, at older ages, postnatal lead

levels will overshadow the effects of earlier exposure. Human development is

quite plastic, with well known catch-up spurts in growth and other aspects of

development. On the other hand, even if early lead-induced deficits are no

longer detected at later ages, this apparent recovery does not necessarily

imply that earlier impairments are without consequence. In view of the complex

interactions that figure into the cognitive, emotional, and social development

of children, compensations in one facet of a child's development may exact a

cost in another area. Very little information is available for evaluating such

interdependencies and trade-offs, but at this point even "temporary" develop-

mental perturbations cannot be viewed as inconsequential.

In addition, given the poor prospects for immediate improvements in the

environments of many children (e.g., deteriorated housing occupied by under-

privileged, inner-city children), lead exposure and toxicity often are, in

practice, irreversible. Thus, the issue of persistence must encompass the

reality of exposure circumstances as well as the potential for biological

recovery.

4. Section 118(f)(1)(D)

This subsection asks for information on the methods and options available

for reducing children's exposure to environmental sources of lead. Chapter IX

("Methods and Alternatives for Reducing Environmental Lead Exposure for Young

Children and Related Risk Groups") addresses this issue. Abatement methods

include primary as well as secondary measures. Primary abatement refers to

reducing or eliminating lead's entrance into pathways by which people are

11

exposed; secondary abatement refers to ways of dealing with lead after it has

already entered the environment or humans. Biological ‘approaches such as

improved nutrition may fall into either of these two categories, depending on

whether they are intended primarily as prophylactic or treatment measures.

Extra-environmental approaches to prevention (e.g., legal actions and stric-

tures) are also discussed.

Here are some key points on the abatement of childhood lead exposure and

poisoning :

0 Efforts in the United States to remove or reduce human lead

exposure have produced notable successes as well as notable

failures.

) Effective primary lead abatement measures have included EPA's

phase-down regulations for gasoline lead, EPA's national ambient

air quality standard for lead, and cooperative actions between

the Food and Drug Administration and the food industry to reduce

lead in food.

0 A number of new initiatives are being implemented by EPA to

reduce lead in the drinking water of children and other popula-

tion segments. Of particular interest is water as it comes from

the tap not only in homes but in public facilities such as

kindergartens and elementary schools. The schools, in partic-

ular, present special exposure characteristics that have not yet

been adequately assessed.

0 Existing leaded paint in U.S. housing and public buildings

remains an untouched and enormously serious problem despite some

regulatory action in the 1970s to limit further input of new

leaded paint to the environment. For this source, corrective

actions have been a clear failure.

0 Lead in dust and soil also remains a potentially serious exposure

source, and remediation attempts have been unsuccessful.

] Secondary prevention measures in the form of U.S. lead screening

programs for children at high risk still appear to require

improved standardization of screening methodology (criteria for

populations, measurement techniques, data collection, data

reporting and statistical analysis) and central coordination.

) The effectiveness of screening children for lead poisoning is

well demonstrated in terms of deferred or averted medical

interventions, and in most settings is quite cost-effective.

0 Extra-environmental measures, such as comprehensive good nutri-

tion programs, have a role in mitigation of lead toxicity, but

they cannot be used as substitutes for initiatives to reduce

lead in the environment.

12

® {2

At present, legal sanctions do not appear to be very effective; to be effective, sanctions have to be both meaningful and rigidly enforced. So long as it is cheaper to pay a fine than to remove lead from the child's environment, little progress is likely to be made on this front.

The "easiest" steps to lead abatement have already been taken or are being taken. These steps, not surprisingly, have involved reducing lead in large-scale sources, such as gasoline and food, With more-or-less centralized distribution mechanisms.

Enormous masses of lead remain in housing along with large amounts of lead in du highly dispersed sources are to be abated, required.

5. Section 118(f)(2)

Chapter X (

Superfund"

Ss ] 1 Protection Agency (EPA)

The National Priorities List (NPL) of September 30, 1987, was reviewed to identify those Sites containing lead. Of the 457 sites, 307 have lead as an identified contaminant and 174 have an observed release of lead to air,

lead-based paint.

(HRS). (The minimu