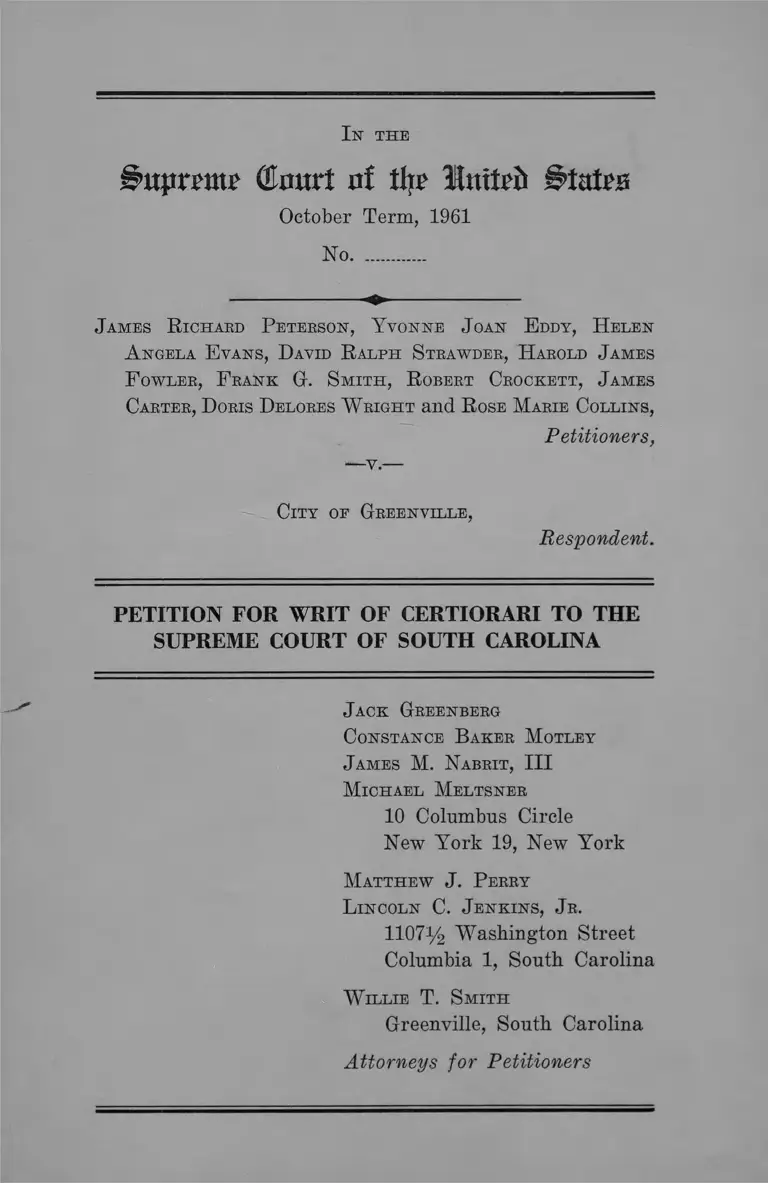

Peterson v. City of Greenville, South Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Peterson v. City of Greenville, South Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1961. 02322514-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5941bfa1-4655-4f55-a45c-1874008d4f20/peterson-v-city-of-greenville-south-carolina-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n THE

i>ttpriw OInurt of % Ilnxttb States

October Term, 1961

No..............

J ames E ichaed P etebson, Y vonne J oan E ddy, H elen

A ngela E vans, D avid R alph S tbawdeb, H akold J ames

P owlee, F eank G. S m ith , R obebt Ceockett, J ames

Caetee, D oeis D eloees W eight and R ose M aeie Collins,

Petitioners,

- v -

C lT Y OE G b EEN VILLE,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

J ack Geeenbeeg

Constance B akee M otley

J ames M. N abeit, III

M ichael M eltsnee

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

M atthew J. P eeey

L incoln C. J en k in s , J e .

1107% Washington Street

Columbia 1, South Carolina

W illie T. S m ith

Greenville, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Citation to Opinions B elow ......................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................,....................................... 2

Questions Presented ..................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved .... 3

Statement ........................................................................ 4

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and De

cided Below .............................................................. 9

Reasons for Granting the Writ .................................. 14

I. Petitioners were denied due process of law

and equal protection of the laws by conviction

of trespass in refusing to leave white lunch

counter where their exclusion was required by

City Ordinance ................................................... 14

II. The decision below conflicts with decisions of

this Court securing the right of freedom of

expression under the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States....... 19

A. The enforcement of the State and City

segregation policy and the interference of

the police violated petitioners’ right to free

dom of expression ....................................... 19

B. The convictions deny petitioners’ right to

freedom of expression in that they rest on

a statute which fails to require proof that

petitioners were requested to leave by a

person who had established authority to

issue such request at the time given......... 23

Conclusion ...................................................................... 26

PAGE

T able oe Cases

page

Abrams v. United States, 250 U. S. 616............. -..... 19

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) .... 18

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Company, 280 F. 2d

531 (5th Cir. 1960) ................................................... 18

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622 .......................... 20

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .............. 18

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 .............................. 18

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 .................................. 25

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 ............................................................................... 17,18

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 ........... 25

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 .. 25

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ..................................... 22

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S. D. Ala. 1949)

aff’d 336 U. S. 933 ..................................................... 17

Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union, Washington Su

perior Court, 45 Lab. Rel. Ref. Man. 2334 (1959) 22

Garner v. Louisiana, 7 L. ed. 2d 207 .................. 19, 20, 24, 26

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903, aff’g 142 F. Supp.

707,712 (M.D. Ala. 1956) ........................................ 18

Guinn v. U. S., 238 U. S. 347 ..................................... 17

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 .................. 18

Lambert v. California, 355 U. S. 225 .......................... 25

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 ..................................... 17

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451...................... 25

Louisiana State University and A & M College v.

Ludley, 252 F. 2d 372 (5th Cir. 1958), cert, denied

358 U. S. 819.............................................................. 17

11

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501...................... ......... 21

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141.............................. 20

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson,

350 U. S. 877 ........................ ...................................... 18

Morrissette v. U. S., 342 U. S. 246 ............................ 25, 26

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 ...................... 20

N.L.R.B. v. American Pearl Button Co., 149 F. 2d 258

(8th Cir. 1945) .......................................................... 21

N.L.R.B. v. Fansteel Metal Corp., 306 U. S. 240......... 21

People v. Barisi, 193 Misc. 934, 86 N. Y. S. 2d 277

(1948) .......................................................................... 21

Republic Aviation Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 324 U. S. 793 .... 21

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 .................................. 25

San Diego Bldg. Trades Council v. Garmon, 349 U. S.

236 ............................................................................... 21

Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 4 7 ...................... 22

Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877 (8th Cir. 1947),

cert, denied 332 U. S. 851.......................................... 22

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147.............................. 23

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U. S. 533 18

State of Maryland v. Williams, Baltimore City Court,

44 Lab. Rel. Ref. Man. 2357 (1959) ........................ 22

State of North Carolina v. Nelson, 118 S. E. 2 d ....... 11

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ...................... 19

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 .............................. 22

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199......... 26

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 .............................. 19, 21

United Steelworkers v. N.L.R.B., 243 F. 2d 593 (D. C.

Cir. 1956), reversed on other grounds, 357 U. S. 357 21

Ill

PAGE

IV

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U. S. 624 .............................................................. 19

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183.......................... 23

Williams v. Hot Shoppes, Inc., 293 F. 2d 835 (D. C.

Cir. 1961) ...................- .............................................. 18

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F.

2d 845 (4th Cir. 1959) ............................................. 11,18

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 .......................... 23, 25

S tatutes and Ordinances

A. & J. R. 1955 (49) 85 ............................................. 16

Code of Greenville, 1953, as amended 1958 Cumula

tive Supplement, §31-8 ..................................3,4, 7,11,14

S. C. A. & J. R. 1956 No. 917..................................... 16

S. C. A. & J. R. 1952 (47) 2223, A. & J. R. 1954 (48)

1695 repealing S. C. Const. Art. 11, §5 (1895) ....... 16

South Carolina Code Ann. Tit. 58, §§714-720 (1952) 16

South Carolina Code, 1952, §16-388, as amended 1960

(A. & J. R., 1960, R. 896, H. 2135) ............................3,4,13

South Carolina Code

§§21-761 to 779 ....................................................... 16

§21-2.......................................................................... 16

§21-230(7) .............................................................. 16

§21-238 (1957 Supp.) ........................................... 16

§40-452 (1952) ....................................................... 16

§§51-1, 2.1-2.4 (1957 Supp.) .................................. 16

§51-181 .................................................................... 16

§5-19 .......... 16

United States Code, §1257(3), Title 2 8 ........................ 2

Other A uthorities

Public Welfare Offenses, 33 Columbia L. Rev. 55

(1933)

PAGE

25

V

INDEX TO APPENDIX

PAGE

Opinion of the Greenville County Court ................. la

Opinion and Judgment of the Supreme Court of

South Carolina ........................................................ 5a

Denial of Rehearing by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina ...................................................................... 11a

I n t h e

irtpmnp (Emtrt of tlu> HttilTfr ^tate#

October Term, 1961

No.............

J ames E ichaed P eterson, Y vonne J oan E ddy, H elen

A ngela E vans, D avid R alph S trawdbr, H arold J ames

F owlee, F rank G. S m it h , E obeet Crockett, J ames

Carter, D oris D elores W right and R ose M arie Collins,

Petitioners,

City of Greenville,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

entered in the above entitled case on November 10, 1961,

rehearing of which was denied November 30, 1961.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

which opinion is the final judgment of that Court, is re

ported at 122 S. E. 2d 826 (1961) and is set forth in the

appendix hereto, infra pp. 5a-10a. The opinion of the Green

ville County Court is unreported and is set forth in the

appendix hereto, infra pp. la-4a.

2

Jurisdiction

The Judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

was entered November 10, 1961, infra pp. 5a-10a. Petition

for rehearing was denied by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina on November 30, 1961, infra p. 11a.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code Section 1257(3), petitioners

having asserted below, and asserting here, deprivation of

rights, privileges and immunities secured by the Constitu

tion of the United States.

Questions Presented

Whether Negro petitioners were denied due process of

law and equal protection of the laws as secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment:

1. When arrested and convicted of trespass for refus

ing to leave a department store lunch counter where the

store’s policy of excluding Negroes was made pursuant to

local custom and a segregation Ordinance of the City of

Greenville.

2. Whether petitioner sit-in demonstrators were denied

freedom of expression secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment when convicted of trespass upon refusal to move from

a white-only lunch counter when (a) the manager did not

request arrest or prosecution and was apparently willing

to endure the controversy without recourse to the criminal

process and exclusion from the counter was required by a

City Ordinance commanding segregation in eating facilities,

and (b) the convictions rest on a statute which fails to re

3

quire proof that petitioners were requested to leave by a

person who had established authority to issue such request

at the time given.

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case involves Section 16-388, Code of Laws of

South Carolina, 1952, as amended 1960:

Any person:

(1) Who without legal cause or good excuse enters

into the dwelling house, place of business or on the

premises of another person, after having been warned

within six months preceding, not to do so or

(2) who, having entered into the dwelling house, place

of business or on the premises of another person with

out having been warned within six months not to do so,

and fails and refuses, without good cause or excuse,

to leave immediately upon being ordered or requested

to do so by the person in possession, or his agent or

representative,

Shall, on conviction, be fined not more than one hun

dred dollars, or be imprisoned for not more than thirty

days.

3. This case involves Section 31-8, Code of Greenville,

1953, as amended by 1958 Cumulative Supplement (R. 56,

57):

It shall be unlawful for any person owning, manag

ing or controlling any hotel, restaurant, cafe, eating

4

house, hoarding house or similar establishment to fur

nish meals to white persons and colored persons in the

same room, or at the same table, or at the same counter;

provided, however, that meals may be served to white

persons and colored persons in the same room where

separate facilities are furnished. Separate facilities

shall be interpreted to mean:

a) Separate eating utensils and separate dishes

for the serving of food, all of which shall be distinctly

marked by some appropriate color scheme or other

wise;

b) Separate tables, counters or booths;

c) A distance of at least thirty-five feet shall be

maintained between the area where white and colored

persons are served;

d) The area referred to in subsection (c) above

shall not he vacant hut shall be occupied by the usual

display counters and merchandise found in a business

concern of a similar nature;

e) A separate facility shall be maintained and used

for the cleaning of eating utensils and dishes fur

nished the two races.

Statement

Petitioners, ten Negro students, were arrested for staging

a sit-in demonstration at the lunch counter of the S. H.

Kress and Company department store on August 9, 1960

(R. 3), in Greenville, South Carolina, a City which by

Ordinance requires segregation in eating facilities (R. 56,

57) and were convicted of trespass in violation of Section

16-388, Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952, as amended

5

1960 and sentenced to pay a fine of one hundred dollars

($100.00) or serve thirty (30) days in jail (R. 54).

After informing the S. H. Kress and Company depart

ment store in Greenville of their desire to be served at the

store’s lunch counter and learning that the manager would

not press charges against them if they sought service (R.

43), petitioners, at about eleven A.M., seated themselves

at the lunch counter and requested service (R. 40, 41).

White persons were seated at the counter -at the time (R.

19, 20, 41). Petitioners were told, “ I ’m sorry, we don’t

serve Negroes” (R. 41).

Also at about eleven A.M., Captain Bramlette of the

Greenville Police Department received a call to go to the

Kress store (R. 5). He did not know where the call came

from (R. 5). He was told that there were colored young

boys and girls at the lunch counter (R. 9) and he knew that

the City of Greenville had an Ordinance prohibiting col

ored and white persons being seated at the same lunch

counter (R. 9). He arrived at the store with several city

policemen and found two agents of the South Carolina Law

Enforcement Department already present at the lunch

counter (R. 6). He noticed the ten petitioners seated at

the lunch counter (R. 6) which could accommodate almost

fifty-nine persons (R. 27). The petitioners were orderly

and inoffensive in demeanor (R. 12, 25, 26).

In the presence of the police officers the counter lights

were turned out (R. 19) and G. W. West, manager of

the store requested “ . . . everybody to leave, that the lunch

counter was closed” (R. 19). At the trial, petitioners’ coun

sel was denied permission to ascertain whether this re

quest followed arrangement or agreement with the Police

(R. 23, 24, 26). Neither Mr. West, the manager, nor the

police officers, testified that West identified himself or his

authority to the petitioners either before or after making

6

this announcement.1 When petitioners made no attempt to

leave the lunch counter, Captain Bramlette placed them

under arrest (R. 20).2

Store manager West at no time requested that defen

dants be arrested (R. 26):

Q. And you at no time requested Captain Bramlette

and the other officers to place these defendants under

arrest, did you? A. No, I did not.

Q. That was a matter, I believe, entirely up to the

law enforcement officers? A. Yes, sir.

White persons were seated at the counter when the an

nouncement to close was made (R. 20, 33, 34) but no white

person was arrested (R. 34). As soon as petitioners were

removed by the police, the lunch counter was reopened

(R. 24, 34).

West testified that one of the store’s employees called

the police (R. 23) but when petitioners’ counsel attempted

to bring out any arrangements or agreements between the

store and the police, the Court denied permission to pro

ceed (R. 23-24, 26). But West testified that he closed the

lunch counter because of the Greenville City Ordinance

requiring racial segregation in eating facilities and local

custom:

1 There is evidence that one of the petitioners, Doris Wright, had

spoken with the store manager prior to the demonstration (R. 43),

but the record is without evidence that any of the other petitioners

were informed or had reason to know that the person who re

quested them to leave had authority to do so. Doris Wright, more

over, testified that the request to leave was made by the Police and

not by manager West who “ . . . was coming from the back at the

time . . . the arrests were being made” (R. 42, 47).

2 Four other Negro demonstrators were arrested but their cases

were disposed of by the juvenile authorities (R. 6).

7

Q. Mr. West, why did you order your lunch counter

closed? A. It’s contrary to local custom and it’s also

the Ordinance that has been discussed (R. 25).

On cross examination, Captain Bramlette, the arresting

officer, evidenced confusion as to whether defendants were

arrested because they violated Greenville’s Ordinance re

quiring segregation in eating facilities or the State of South

Carolina’s trespass statute (R. 16, 17):

Q. Did the manager of Kress’, did he ask you to

place these defendants under arrest, Captain Bram

lette? A. He did not.

Q. He did not? A. No.

Q. Then why did you place them under arrest? A.

Because we have an Ordinance against it.

Q. An Ordinance? A. That’s right.

Q. But you just now testified that you did not have

the Ordinance in mind when you went over there?

A. State law in mind when I went up there.

Q. And that isn’t the Ordinance of the City of Green

ville, is it? A. This supersedes the order for the City

of Greenville.

Q. In other words, you believe you referred to an

ordinance, but I believe you had the State statute in

mind? A. You asked me have I, did I have knowledge

of the City Ordinance in mind when I went up there

and I answered I did not have it particularly in my

mind, I said I had the State Ordinance in my mind.

Q. I see and so far this City Ordinance which re

quires segregation of the races in restaurants, you at

no time had it in mind, as you went about answering

the call to Kress’ and placing these people under ar

rest? A. In my opinion the state law was passed re

cently supersedes our City Ordinance.

8

This “ State Law” is the trespass statute petitioners were

charged with violating. Previously, Captain Bramlette had

testified that he thought the State’s trespass statute pro

hibited “ sit-ins.” He later admitted that the statute did

not mention “ sit-ins” (E. 14).

Kress and Company is a large nationwide chain (E. 21)

which operates junior department stores (E. 21). The

Greenville branch has fifteen to twenty departments, sells

over 10,000 items and is open to the general public (E. 21,

22). Negroes and whites are invited to purchase and are

served alike with the exception that Negroes are not served

at the lunch counter which is reserved for whites (E. 22).

Kress’s national policy is “ to follow local customs” with

regard to serving Negroes and whites at its lunch counters

(E. 22, 23).

Petitioners were tried and convicted in the Eecorder’s

Court of Greenville before the City Eecorder, sitting with

out a jury, and sentenced to pay a fine of one hundred

dollars ($100.00) or serve thirty (30) days in the City jail

(E. 2, 54).

Petitioners appealed the judgment of Eecorder’s Court

to the Greenville County Court, which Court dismissed the

appeal on March 17,1961 (E. 57-60).

The Supreme Court of South Carolina entered its judg

ment, affirming the judgment and sentences below on No

vember 10, 1961, infra pp. 5a-10a, and denied rehearing on

November 30, 1961, infra p. 11a.

9

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

At the commencement of the trial in the Recorder’s Court

of the City of Greenville, petitioners moved to quash the

informations and dismiss the warrants on the ground that

the charge was too uncertain and indefinite to apprise peti

tioners of the charge against them, in violation of the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States (R. 2, 3). The motion was

denied by the Court (R. 3).

At the close of the prosecution’s case, petitioners moved

to dismiss the warrants against them:

“ The evidence presented on the charge shows conclu

sively that by arresting the defendants the officers were

aiding and assisting the owners and managers of

Kress’ Five and Ten Cent Store, in maintaining their

policies of segregating or excluding service to Negroes

at its lunch counter . . . in violation of defendants’

rights to due process of law, and equal protection of

the laws, under the 14th Amendment to the United

States Constitution” (R. 28, 29);

“ that the warrant which charges them with trespass

after warning, the designation of the act being set

forth as invalid, in that the evidence establishes merely

that defendants were peacefully upon the premises of

S. H. Kress & Company, which establishment is per

forming an economic function invested with the public

interest as customers, visitors, business guests or in

vitees and there is no basis for the charge recited by

the warrants other than an effort to exclude these de

fendants from the lunch counters of Kress’ Five and

Ten Cent Store, because of their race and color . . .

thereby depriving them of liberty without due process

10

of law and equal protection of the laws secured to them

by the 14th Amendment to the United States Consti

tution” (E. 29, 30);

“ The designation of the act being set forth in the war

rant under which all these defendants, who are

Negroes, were arrested and charged is on the evidence

unconstitutional as applied to the defendants, in that

it makes it a crime to be on property open to the public

after being asked to leave because of race and color

in violation of the defendants’ rights under the due

process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amend

ment to the United States Constitution” (E. 30).

These motions were denied by the Court (E. 29, 30).

Petitioners further moved for a dismissal on the ground

that the City had not established a prima facie case (E. 30).

This motion was denied (E. 30).

At the close of the trial, petitioners renewed all motions

for dismissal made at the conclusion of the City’s case

(E. 52). These motions were again denied (E. 52). Fur

ther, petitioners moved for dismissal of the cases on the

ground that:

“ . . . the Negro defendants, were arrested and charged

under a statute which is itself unconstitutional on

its face, by making it a crime to be on public property

after being asked to leave by an individual, at such

individual’s whim. In that, such statute does not re

quire that the person making the demand to leave, pre

sent documents or other evidence of possessing a right

sufficient to apprise the defendants of the validity of

the demand to leave. All of which renders the statute

so vague and uncertain, as applied to the defendants,

as to violate their rights under the due process clause

11

of the 14th Amendment to the United States Consti

tution . . . ”

This motion was denied by the Court (R. 53).

At the close of petitioners’ trial, but before judgment,

petitioners’ counsel moved to place Greenville’s segrega

tion in eating facilities Ordinance in evidence for considera

tion in regard to the judgment (R. 53). The Court denied

this motion (R. 54) but the Ordinance was placed in record

on appeal (R. 56).

Subsequent to judgment, petitioners renewed all motions

made prior thereto by moving for arrest of judgment or,

in the alternative, a new trial (R. 54). The motion was not

granted (R. 54, 55).

After considering petitioners’ exceptions (R. 60), the

Greenville County Court, on appeal held:

“ . . . the appeal should be dismissed because the prose

cution was conducted under a valid constitutional stat

ute and in addition the appeal should be dismissed upon

the ground that S. H. Kress and Company has a right

to control its own business. We think this position is

fully sustained under the recent case of Williams v.

Johnson, Res. 344, 268 Fed. (2d) 845 and the North

Carolina case of State v. Nelson decided January 20,

1961 and reported in 118 S. E. (2d) at page 47” (R. 60).

In appealing to the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

petitioners set forth the following exceptions to the judg

ment below (R. 61-63):

“1. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the

warrant is vague, indefinite and uncertain and does

not plainly and substantially set forth the offense

charged, thus failing to provide appellants with suffi

12

cient information to meet the charges against them as

is required by the laws of the State of South Carolina,

in violation of appellants’ rights to due process of law,

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution.

2. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the

State failed to establish the corpus delicti.

3. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the

State failed to prove a prima facie case.

4. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the evi

dence of the State shows conclusively that by arresting-

appellants the officers were aiding and assisting the

owners and managers of S. H. Kress and Company in

maintaining their policies of segregating or excluding

service to Negroes at their lunch counters on the ground

of race or color, in violation of appellants’ right to due

process of law and equal protection of the laws, se

cured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the United

States Constitution.

5. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the evi

dence establishes merely that the appellants were

peacefully upon the premises of S. H. Kress and Com

pany, an establishment performing an economic func

tion invested with the public interest as customers,

visitors, business guests or invitees, and that there is

no basis for the charge recited by the warrants other

than an effort to exclude appellants from the lunch

counter of said business establishment because of their

race and color, thereby depriving appellants of liberty

without due process of law and equal protection of

the laws, secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution.

13

6. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the stat

ute appellants are alleged to have violated, to wit, Act

No. 743 of the Acts and Joint Resolutions of the Gen

eral Assembly of South Carolina for 1960 (R. 896,

H. 2135), is unconstitutional on its face by making it

a crime to be on public property after being asked to

leave by an individual at such individual’s whim and

does not require that the person making the demand to

leave present documents or other evidence of pos

sessory right sufficient to apprise appellants of the

validity of the demand to leave, all of which renders

the statute so vague and uncertain as applied to ap

pellants as to violate their rights under the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution.

7. The Court erred in refusing to permit defendants’

counsel to elicit relevant testimony concerning coopera

tion of Store Managers and Police in the City of Green

ville, South Carolina in pursuing the store managers’

policies, customs and practices of segregating or ex

cluding Negroes from their lunch counters.”

In disposing of petitioners’ constitutional objections, the

Supreme Court of South Carolina held that the charge in

the warrant was “ definite, clear and unambiguous” infra

p. 7a; that “ the act makes no reference to race or color

and is clearly for the purposes of protecting the rights of

the owners or those in control of private property. Irrespec

tive of the reason for closing the counter, the evidence is

conclusive that defendants were arrested because they chose

to remain upon the premises after being requested to leave

by the manager . . . and their constitutional rights were

not violated when they were arrested for trespass,” infra

pp. 8a, 9a.

14

The Court disposed of Greenville’s Ordinance requiring

segregation in eating facilities as follows:

“Upon cross-examination of Capt. G. 0. Bramlette

of the Greenville City Police Department, it was

brought out that the City of Greenville has an ordi

nance making it unlawful for any person owning, man

aging, or controlling any hotel, restaurant, cafe, etc.,

to furnish meals to white persons and colored persons

except under certain conditions; and Defendants con

tend that they were prosecuted under this ordinance;

however, the warrant does not so charge and there is

nothing in the record to substantiate this contention.

The ordinance was made a part of the record upon

request of defendants’ counsel hut defendants were

not charged with having violated any of its provisions.

The question of the validity of this ordinance was not

before the trial Court and therefore not before this

Court on appeal.”

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The Court below decided this case in conflict with prin

ciples declared by this Court as is further set forth below:

I.

Petitioners were denied due process of law and equal

protection of the laws by conviction of trespass in re

fusing to leave white lunch counter where their exclu

sion was required by City Ordinance.

Although formally charged with violation of South Caro

lina’s trespass statute, petitioners were actually convicted

of having violated the segregation policy of the City of

Greenville. This policy is expressed in Section 31-8, Code

15

of Greenville, 1953, as amended 1958 Cumulative Supple

ment, see supra p. 3, making it unlawful “ . . . to furnish

meals to white persons and colored persons in the same

room, or the same table, or at the same counter . . . ”

(E. 56-57).

G. W. West, the Manager of the department store, and

a Kress employee for fifteen years3 (E. 20) testified ex

plicitly that exclusion of Negroes from the lunch counter

and the closing of the counter when petitioners sought

service, was caused by the City Ordinance requiring seg

regation in eating facilities (E. 25).

Confirmation that the police were enforcing segregation

is indicated by the fact that some whites seated at the

lunch counter during the demonstration remained seated

and were not arrested (E. 34) although the announcement

to leave was made in general terms (E. 19) and at least

five policemen were present (E. 5, 6). Moreover, the coun

ter was reopened as soon as petitioners were removed by

the police (E. 25).

Further confirmation that the policy of enforcing segre

gation was the City’s appears from how the arrests were

made. The police proceeded to Department Store without

requests to arrest by the management (E. 5), and arrested

petitioners without a request from the management (E. 26).

The manager of the store testified that arrest was entirely

the decision of the police (E. 26) and it does not appear

that the management signed any complaint against peti

tioners.

Prior to the demonstration, a representative of peti-

tioers had discussed the question of service with the man

3 West came to live in Greenville on February 3, 1960, the day

he became Manager of the Kress Store. Prior to this he worked

for Kress in other Cities (K. 20, 21).

16

ager and had been told that the criminal process would

not be invoked by the store (R. 43). This was not the first

demonstration petitioners had held in Kress’s (R. 44).

When petitioners’ counsel attempted to question the man

ager as to any agreement or arrangement he had made with

the police prior to the closing of the lunch counter, the

Court denied permission to proceed (R. 23, 24, 26).

On this record it is clear that Kress and Company would

have been willing to cope with the controversy within the

realm of social and economic give and take absent the Ordi

nance of the City of Greenville requiring segregation and

the force of local customs supported by the City and the

State of South Carolina.4 If, as the manager testified,

Kress & Company maintained the policy of segregation

because of the Ordinance, then there can be no other con

clusion than that the City, by the Ordinance and by arrest

and criminal conviction, has “ place [d] its authority behind

discriminatory treatment based solely on color . . . ” Mr. * S.

4 There can be little doubt that segregation of the races had

been and is the official policy of the State of South Carolina. Cf.

S. C. A. & J. R. 1952 (47) 2223, A. & J. R. 1954 (48) 1695 re

pealing S. C. Const. Art. 11, §5 (1895) (which required legislature

to maintain free public schools). S. C. Code §§21-761 to 779 (regu

lar school attendance), repealed by A. & J. R. 1955 (49) 85; §21-2

(appropriations cut off to any school from which or to which any

pupil transferred because of court order; §21-230(7) (local trustees

may or may not operate schools); §21-238 (1957 Supp.) (school

officials may sell or lease school property whenever they deem it

expedient) ; S. C. Code §40-452 (1952) (unlawful for cotton textile

manufacturer to permit different races to work together in same

room, use same exits, bathrooms, etc., $100 penalty and/or im

prisonment at hard labor up to 30 days; S. C. A. & J. R. 1956

No. 917 (closing park involved in desegregation su it); S. C. Code

§§51-1, 2.1-2.4 (1957 Supp.) (providing for separate State Parks)

§51-181 (separate recreational facilities in cities with population

in excess of 60,000); §5-19 (separate entrances at circus); S. C.

Code Ann. Tit. 58, §§714-720 (1952) (segregation in travel

facilities).

17

Justice Frankfurter dissenting in Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, 727. The City Ordinance

is no abstract exhortation but obligatory by its terms, to

which were attached criminal sanctions, and it is uncon

tradicted that one of the reasons Kress & Company chose

a policy of racial segregation was because of the Ordinance.

The discriminatory practice of Kress, the request that

petitioners leave and their arrest and conviction, result,

therefore, directly from the formally enacted policy of the

City of Greenville, South Carolina, and not (so far as

this record indicates) from any individual or corporate

business decision or preference of the management of the

store to exclude Negroes from the lunch counter. Whatever

the choice of the property owner may have been, here the

City made the choice to exclude petitioners from the prop

erty through its segregation Ordinance. This City segrega

tion policy was enforced by petitioners’ arrests, convictions

and sentences in the South Carolina courts.

The Supreme Court of South Carolina dismisses ref

erence to the City segregation Ordinance by stating “ The

Ordinance was made a part of the record upon request of

defendants’ counsel but defendants were not charged with

having violated any of its provisions.” But the Constitu

tion forbids “ sophisticated as well as simple-minded modes

of discrimination.” Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 275.5

By enacting, first, that persons who remain in a restau

rant when the owner demands that they leave are “ tres

passers,” and then enacting that restaurateurs may not 5

5 Racial segregation imposed under another name often has been

condemned by this Court. Guinn v. U. S., 238 U. S. 347; Lane v.

Wilson, supra; Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S. D. Ala. 1949)

aff’d 336 U. S. 933; and see Louisiana State University and A. &

M. College v. Dudley, 252 F. 2d (5th Cir. 1958) cert, denied 358

U. S. 819.

18

permit Negroes to remain in white restaurants, South

Carolina has very clearly made it a crime (a trespass) for

a Negro to remain in a white restaurant. The manager

of Kress’s admits as much when he testified that the lunch

counter was closed and petitioners asked to leave because

of the Ordinance (R. 25).

This case thus presents a plain conflict with numerous

prior decisions of this Court invalidating state efforts to

require racial segregation. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S.

60; Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Gayle v.

Browder, 352 U. S. 903 aff’g 142 F. Supp. 707, 712 (M. D.

Ala. 1956); Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879; Mayor

and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877;

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U. S. 533; cf.

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715.

Note the dissenting opinion of Judges Bazelon and Edger-

ton in Williams v. Hot Shoppes, Inc., 293 F. 2d 835, 843

(D. C. Cir. 1961) (dealing primarily with the related issue

of whether a proprietor excluding a Negro under an er

roneous belief that this was required by state statute was

liable for damages under the Civil Rights Act; the majority

applied the equitable abstention doctrine). Indeed, Williams

v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d 845, 847 (4th

Cir. 1959) relied upon by the Supreme Court of South Caro

lina below, indicated that racial segregation in a restau

rant “ in obedience to some positive provision of State law”

would be a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. See

also Boman v. Birmingham Transit Company, 280 F. 2d

531 (5th Cir. 1960); Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750

(5th Cir. 1961).

19

II.

The decision below conflicts with decisions of this

Court securing the right of freedom of expression under

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

A. The Enforcement of the State and City Segregation

Policy and the Interference of the Police Violated

Petitioners’ Right to Freedom of Expression.

Petitioners were engaged in the exercise of free ex

pression, by verbal and nonverbal requests to the manage

ment for service, and nonverbal requests for nondiscrimina-

tory lunch counter service, implicit in their continued

remaining in the dining area when refused service. As Mr.

Justice Harlan wrote in Garner v. Louisiana-. “We would

surely have to be blind not to recognize that petitioners

were sitting at these counters, when they knew they would

not be served, in order to demonstrate that their race was

being segregated in dining facilities in this part of the

country.” 7 L. ed. 2d at 235-36. Petitioners’ expression

(asking for service) was entirely appropriate to the time

and place at which it occurred. They did not shout or

obstruct the conduct of business. There were no speeches,

picket signs, handbills or other forms of expression in the

store possibly inappropriate to the time and place. Rather

they offered to purchase in a place and at a time set aside

for such transactions. Their protest demonstration was a

part of the “ free trade in ideas” (Abrams v. United States,

250 U. S. 616, 630, Holmes, J dissenting), within the range

of liberties protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, even

though nonverbal. Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359

(display of red flag); Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88

(picketing); West Virginia State Board of Education v.

20

Barnette, 319 IT. S. 624, 633-634 (flag salute); N.A.A.C.P.

v. Alabama, 357 IT. S. 449 (freedom of association).

Questions concerning freedom of expression are not re

solved merely by reference to the fact that private property

is involved. The Fourteenth Amendment right to free ex

pression on private property takes contour from the cir

cumstances, in part determined by the owner’s privacy,

his use and arrangement of his property. In Breard v.

Alexandria, 341 IT. S. 622, the Court balanced the “house

holder’s desire for privacy and the publisher’s right to

distribute publications” in the particular manner involved,

upholding a law limiting the publisher’s right to solicit on

a door-to-door basis. But cf. Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S.

141 where different kinds of interests led to a correspond

ing difference in result. Moreover, the manner of asser

tion and the action of the State, through its officers, its

customs and its creation of the property interest are to be

taken into account.

In this constitutional context it is crucial, therefore,

that the stores implicitly consented to the protest and did

not seek intervention of the criminal law. For this case

is like Garner v. Louisiana, supra, where Mr. Justice Har

lan, concurring, found a protected area of free expression

on private property on facts regarded as involving “ the

implied consent of the management” for the sit-in demon

strators to remain on the property. Petitioners informed

the management that there would be a protest and received

assurance that the management would not resort to the

criminal process. Petitioners were not asked to leave the

counter until the police arrived and the manager talked

with the police. It does not appear that anyone connected

with the store signed an affidavit or complaint against

petitioners. The police officer proceeded immediately to

21

arrest the petitioners without any request to do so on

the part of anyone connected with the store.

In such circumstances, petitioners’ arrest must he seen

as state interference in a dispute over segregation at this

lunch counter, a dispute being resolved by persuasion and

pressure in a context of economic and social struggle be

tween contending private interests. The Court has ruled

that judicial sanctions may not be interposed to discrim

inate against a party to such a conflict. Thornhill v. Ala

bama, supra; San Diego Bldg. Trades Council v. Garmon,

349 U. S. 236.

But even to the extent that the store may have acquiesced

in the police action a determination of free expression

rights still requires considering the totality of circum

stances respecting the owner’s use of the property and the

specific interest which state judicial action supports. Marsh

v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501.

In Marsh, this Court reversed trespass convictions of

Jehovah’s Witnesses who went upon the privately owned

streets of a company town to proselytize, holding that the

conviction violated the Fourteenth Amendment. In Re

public Aviation Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 324 U. S. 793, the Court

upheld a labor board ruling that lacking special circum

stances employer regulations forbidding all union solicita

tion on company property constituted unfair labor prac

tices. See Thornhill v. Alabama, supra, involving picketing

on company-owned property; see also N.L.R.B. v. American

Pearl Button Co., 149 F. 2d 258 (8th Cir. 1945); United

Steelworkers v. N.L.R.B., 243 F. 2d 593, 598 (D. C. Cir.

1956), reversed on other grounds, 357 U. S. 357, and com

pare the cases mentioned above with N.L.R.B. v. Fansteel

Metal Corp., 306 U. S. 240, 252, condemning an employee

seizure of a plant. In People v. Barisi, 193 Mi sc. 934, 86

22

N. Y. S. 2d 277, 279 (1948) the Court held that picketing

within Pennsylvania Railroad Station was not a trespass;

the owners opened it to the public and their property rights

were “ circumscribed by the constitutional rights of those

who use it.” See also Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union,

Washington Superior Court, 45 Lab. Eel. Ref. Man. 2334

(1959); and State of Maryland v. Williams, Baltimore City

Court, 44 Lab. Rel. Ref. Man. 2357, 2361 (1959).

In the circumstances of this case the only apparent state

interest being subserved by these trespass prosecutions is

support of the property owner’s discrimination, a policy

which the manager testified was caused by the State’s seg

regation custom and policy and the express terms of the

City Ordinance. This is the most that the property owner

can he found to have sought.

Where free expression rights are involved, the question

for decision is whether the relevant expressions are “ in

such circumstances and . . . of such a nature as to create

a clear and present danger that will bring about the sub

stantive evil” which the State has the right to prevent.

ScJienck v. United States, 249 U. S. 47, 62. The only “ sub

stantive evil” sought to be prevented by these trespass

prosecutions is the stifling of protest against the elimina

tion of racial discrimination, but this is not an “ evil” within

the State’s power to suppress because the Fourteenth

Amendment prohibits state support of racial discrimina

tion. See Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1; Terminiello v.

Chicago, 337 U. S. 1; Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877

(8th Circuit, 1957), cert, denied 332 U. S. 851.

23

B. The Convictions Deny Petitioners’ Right to Freedom

of Expression in That They Rest on a Statute Which

Fails to Require Proof That Petitioners Were Re

quested to Leave by a Person Who Had Established

Authority to Issue Such Request at the Time Given.

In the courts below petitioners asserted that the statute

in question denied due process of law secured by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

in that it did not require that the person requesting them

to leave the lunch counter establish his authority to make

the demand. Although raised and pressed below by peti

tioners, the Supreme Court of South Carolina failed to

construe the statute to require proof that the person who

requested them to leave establish his authority.

If in the circumstances of this case free speech is to be

curtailed, the least one has a right to expect is reasonable

notice in the statute under which convictions are obtained,

to that effect. Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507. Here,

absent a statutory provision that the person making the

request to leave be required to communicate that authority

to the person asked to leave, petitioners, in effect, have

been convicted of crime for refusing to cease their pro

tests at the request of a person who could have been a

stranger. The stifling effect of such a rule on free speech

is obvious. See Wieman v. JJpdegraff, 344 U. S. 183; Smith

v. California, 361 U. S. 147.

The vice of lack of fair notice was compounded where,

as here, petitioners were convicted under a statute which

designated two separate crimes, see supra p. 3, and a

warrant which failed to specify under which section the

prosecution proceeded (R. 2). Moreover, the warrant and

the trial court stated that petitioners were charged with

“trespass after warning” (R. 2) (Section (1) of the Stat

ute speaks of being “warned” ; Section (2) “ without having

been warned” ), but the prosecution offered no proof that

24

petitioners had been “warned” within six months as re

quired by Section (1) and apparently proceeded on the

theory that Section (2) of the statute was involved.

This record is barren of any attempt by the City of

Greenville to prove that the person who requested peti

tioners to leave identified his authority to do so to petition

ers, and the courts of South Carolina, although urged by

petitioners, failed to require such proof. While one of the

petitioners brought out, when questioned by her own coun

sel, that she had spoken to the manager previously,6 there

is no evidence that the other petitioners knew the authority

of the person who gave the order to leave. With rights

to freedom of expression at stake, the City should be re

quired to provide clear and unambiguous proof of all the

elements of the crime. Identification of authority to make

the request to leave is all the more important because of

the active role played by the police in this case, for if the

police were enforcing segregation clearly petitioners had

a right to remain at the counter. Garner v. Louisiana,

supra.

No one ordinarily may be expected to assume that one

who tells him to leave a public place, into which the pro

prietor invited him and in which he has traded, is authorized

to utter an order to leave when no claim of such authority

is made. This is especially true in the case of a Negro seat

ing himself in a white dining area in Greenville, South

Carolina—obviously a matter of controversy and one which

any stranger, or the police of a city with a segregation

ordinance, might be expected to volunteer strong views. If

the statute in question is interpreted to mean that one must

leave a public place under penalty of being held a criminal

when so ordered to do so by a person who later turns

6 She also testified that the police, not the manager, gave the

order for petitioners to leave. See Note 1, supra.

25

out to have been in authority without a claim of authority

at the time, it means as a practical matter, that one must

depart from public places whenever told to do so by any

one; the alternative is to risk tine or imprisonment. Such

a rule might be held a denial of due process. Cf. Lambert v.

California, 335 U. S. 225. But if such is the rule the statute

gives no fair warning, Winters v. New York, supra; Burstyn

v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495; Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558;

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568. Absent such

notice, petitioners surely were entitled to assume that one

may go about a public place under necessity to observe

orders only from those who claim with some definiteness

the right to give them.

Indeed, as a matter of due process of law, if it is the

rule one must obey all orders of strangers to leave public

places under penalty of criminal conviction if one uttering

the order later turns out to have had authority, petitioners

are entitled to more warning of its harshness than the stat

ute’s text affirmed. Cf. Connolly v. General Construction

Co., 269 U. S. 385; Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451.

Otherwise many persons—like these petitioners—may be

held guilty of crime without having intended to do wrong.

This Court has said, however, that:

The contention that an injury can amount to a crime

only when inflicted by intention is no provincial or

transient notion. It is as universal and persistent in

mature systems of law as belief in freedom of the

human will and a consequent ability and duty of the

normal individual to choose between good and evil.

Morrissette v. U. S., 342 U. S. 246, 250.

Morrissette, of course, involved a federal statute as treated

in the federal courts. But it expresses the fundamental view

that scienter ought generally to be an element in criminality.

See Sayre, Public Welfare Offenses, 33 Columbia L. Bev.

26

55, 55-6 (1933). The pervasive character of scienter as an

element of crime makes it clear that a general statute like

the ordinance now in question, in failing to lay down a

scienter requirement, gives no adequate warning of an

absolute liability. Trespass statutes like the one at bar

are quite different from “public welfare statutes” in which

an absolute liability rule is not unusual. See Morrissette

v. United States, supra, 342 U. S. at 252-260.

On the other hand, however, if South Carolina were to

read a scienter provision into this ordinance for the first

time—which it has failed to do although the issue was

squarely presented in this case—the lack of the necessary

element of guilt, notice of authority, would require reversal

under authority of Garner v. Louisiana, supra; Thompson

v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199.

Wherefore, for the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully

submitted that the petition for writ of certiorari should

be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Constance B aker M otley

J ames M. N abrit, III

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

M atthew J. P erry

L incoln C. J en k in s , J r.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia 1, South Carolina

W illie T. S m ith

Greenville, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

la

APPENDIX

Order

I n THE

GREENVILLE COUNTY COURT

J ames R ichaed P eterson, et al .,

—v.—

City of Greenville.

APPEAL FROM TH E RECORDER’S COURT

OF T H E C ITY OF GREENVILLE

This is an appeal to this Court from the Recorder’s

Court of the City of Greenville.

The Defendants were tried on August 11, 1960, in the

Greenville City Recorder’s Court before the Recorder,

John V. Jester, upon a charge of violating the Act of

May 20, 1960, which in substance makes any person a tres

passer who refuses to leave the premises of another im

mediately upon being requested to leave.

The Act is very simple and plain in its language.

It appears that on August 9, 1960, the ten Defendants,

who are making this appeal, with four other young Negro

youths went to the store of S. H. Kress and Company and

seated themselves at the lunch counter at the store. At the

trial there seemed to be some attempt to minimize the evi

dence of the officers involved as to whether or not the

Defendants, now Appellants, refused to leave the premises

immediately upon the request of the store manager that

2a

they should leave. However, in the argument of the chief

counsel for the Appellants, all question of doubt in this

respect is resolved in favor of the City. According to the

written Brief of the Defendants, the Defendants now

“ seated themselves at the lunch counter where they sought

to be served. They were not served and, in fact, were

told by the management that they could not be served and

would have to leave. The Defendants refused to leave and

remained seated at the lunch counter.”

The act clearly makes it a criminal offense for any

person situated as the Defendants were to refuse or fail

to “ immediately” depart upon request or demand.

Therefore, the main question before this Court is whether

or not the Appellants were lawfully tried on a charge of

violating this Act by refusing to leave the lunch counter

immedately when requested to do so.

In the oral argument counsel for the Appellants seemed

to reply in a vague manner upon an “unconstitutional ap

plication” of the Statute.

As the Court views the statute it was merely a statutory

enlargement and re-enactment of the common law in South

Carolina which has been recognized for more than a half

century to the effect that when a property owner, whether

it be a dwelling house or place of business, has the right

to order any person from the premises whether they be an

invitee or an uninvited person. This principle of law was

fully and clearly reaffirmed by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina in the recent case of State v. Starner, et al., 49

S. E. (2d) 209.

For scores of years South Carolina has had a number

of Statutes with reference to the law of trespass. They

are now embodied as Article 5, Code of 1952, embracing

Sections 16-381 to 16-394. Section 17-286 particularly refers

to trespasses after notice.

O rd er o f G reen v ille C o m ity C ou rt

3a

Therefore, the Act of May 20, 1960, now designated in

the 1952 Code as Sec. 17-388 is the controlling factor here.

There can be no doubt that the field into which the Legisla

ture entered by the enactment of this particular law was

a well recognized portion of the law of the State of South

Carolina. The Constitutionality of the Act cannot be ques

tioned.

Every presumption will be made in favor of the Con

stitutionality of a statute. There are more than fifty de

cisions by the Supreme Court of South Carolina to this

effect. The United States Supreme Court in many cases

has recognized that there is a presumption in favor of the

constitutionality of an Act of Congress or of a State or

Municipal legislative body. In the case of Davis v. Depart

ment of Labor, 317 U. S. 255, 87 Law Ed. 250, the United

States Supreme Court held that there is a presumption

of constitutionality in favor of State statutes. Time and

time again the Supreme Court of South Carolina has held

“ the law is well settled that the burden is on the person

claiming the Act to be unconstitutional to prove and show

that it is unconstitutional beyond a reasonable doubt” .

McCollum v. Snipes, 49 S. E. 12, 213 S. C. 254.

In 16 C. J. S. 388, we find this language, “ Statutes are

presumed to be valid and a party attacking a statute as

unconstitutional has the burden of proof” . Over five hun

dred decisions from all over the United States are cited

to support this statement of the law.

The argument of counsel for the Appellants failed to

raise a single serious question as to the constitutionality

of the statute.

Counsel for Appellants insisted upon the right of the

Defendants to adduce evidence of some alleged conspiracy

or plan on the part of the officers of the law and store

O rd er o f G reen v ille C oirn ty C ou rt

4a

management to bring about this prosecution. We think

the sole issue in the Recorder’s Court was whether or not

the Defendants were guilty of violating the Act in ques

tion. They now boldly admit through counsel that they

defied the management of the store and refused to leave

when requested. Had they departed from the store im

mediately, as the law requires they should have, there

would have been no arrest, but apparently in accordance

with a preconceived plan they all kept their seats and

defied the management and refused to leave the premises.

Evidence of any other motive on the part of the manage

ment would have thrown no light on this case.

In my opinion the appeal should be dismissed because

the prosecution was conducted under a valid constitu

tional statute and in addition the appeal should be dis

missed upon the ground that S. H. Kress and Company

had a right to control its own business. We think this

position is fully sustained under the recent case of Wil

liam v. Johnson, Res. 344, 268 Fed. (2d) 845, and the North

Carolina case of State v. Nelson, decided January 20, 1961,

and reported in 118 S. E. (2d) at page 47.

I carefully considered all the exceptions made by the

Appellants and I am unable to sustain any of them. It is,

therefore,

Ordered, adjudged and decreed that the Appeal be dis

missed.

J ames H. P rice,

Special Judge,

Greenville County Court.

O rd er o f G reen v ille C o u n ty C ou rt

March 17, 1961.

5a

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAEOLINA

I n the S itpbeme Court

Opinion

City of Greenville,

— v.—

Respondent,

J ames E ichard P eterson, Y vonne J oan E ddy, H elen

A ngela E vans, D avid E alph S trawder, H arold J ames

F owler, F rank G. S m it h , E obert Crockett, J ames

Carter, D oris D elores W right and E ose M arie Collins,

Appellants.

Appeal From Greenville County

James H. Price, Special County Judge

Case No. 4761

Opinion No. 17845

Filed November 10, 1961

T aylor, C.J. : Defendants were convicted of the charge

of trespass after notice in violation of Section 16-388,

Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952, as amended, and

appeal. By agreement of counsel, all hail bonds were con

tinued in effect pending disposition of this appeal.

On August 9, 1960, in response to a call, law enforce

ment officers were dispatched to the S. H. Kress Store in

Greenville, South Carolina, a member of a large chain of

6a

stores operated throughout the United States and described

as a junior department store. Upon arrival they found

the ten defendants and four others who were under six

teen years of age, all Negroes, seated at the lunch counter.

There is testimony to the effect that because of the local

custom to serve white persons only at the lunch counter

the manager of the store announced that the lunch counter

was closed, the lights were extinguished, and all persons

were requested to leave. The white persons present left,

hut all Negroes refused to leave; and those above the age

of sixteen were thereupon charged with trespass after

notice as provided in the aforementioned section of the

Code, which provides:

“Any person:

“ (1) Who without legal cause or good excuse enters

into the dwelling house, place of business or on the

premises of another person, after having been warned

within six months preceding, not to do so or

“ (2) Who, having entered into the dwelling house,

place of business or on the premises of another person

without having been warned within six months not

to do so, and fails and refuses, without good cause or

excuse, to leave immediately upon being ordered or

requested to do so by the person in possession, or his

agent or representative,

“ Shall, on conviction, be fined not more than one

hundred dollars or he imprisoned for not more than

thirty days.”

Defendants contend, first, error in refusing to dismiss

the warrant upon the ground that the charge contained

therein was too indefinite and uncertain as to apprise the

O pin ion , S ou th C a rolin a S u p rem e C ou rt

7a

defendants as to what they were actually being charged

with.

Defendants were arrested in the act of committing the

offense charged, they refused the manager’s request to

leave after the lunch counter had been closed and the lights

extinguished, and there could have been no question in

defendants’ minds as to what they were charged with.

Further, there was at that time no claim of lack of suffi

cient information, and upon trial there was no motion to

require the prosecution to make the charge more definite

and certain. Defendants rely upon State v. Randolph,

et al.,------S. C. ——, 121 S. E. (2d) 349, where this Court

held that it was error to refuse defendants’ motion to

make the charge more definite and certain in a warrant

charging breach of the peace. It was pointed out in that

case that breach of the peace embraces a variety of con

duct and defendants were entitled to be given such in

formation as would enable them to understand the nature

of the offense. This is not true in instant case where the

charges were definite, clear and unambiguous; further, no

motion was made to require the prosecution to make the

charge more definite and certain. There is no merit in this

contention.

Defendants next contend that their arrest and convic

tion was in furtherance of a custom of racial segregation

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States.

Defendants entered the place of business of the S. H.

Kress Store and seated themselves at the lunch counter,

they contend, for the purpose of being served, although

four of them had no money and there is no testimony

that such service was to be paid for by others.

The testimony reveals that the lunch counter was closed

because it was the custom of the S. H. Kress Store in

O pin ion , S o u th C arolin a S u p rem e C ou rt

8a

Greenville, South Carolina, to serve whites only and after

all persons had left or been removed the lunch counter

was reopened for business. The statute with no reference

to segregation of the races applies to “Any person: * * *

Who fails and refuses without cause or good excuse # * *

to leave immediately upon being ordered or requested to

do so by the person in possession or his agent or repre

sentative, * * # ” The act makes no reference to race or

color and is clearly for the purpose of protecting the rights

of the owners or those in control of private property. Ir

respective of the reason for closing the counter, the evi

dence is conclusive that defendants were arrested because

they chose to remain upon the premises after being re

quested to leave by the manager.

Defendants do not attack the statute as being uncon

stitutional but contend that their constitutional rights were

abridged in its application in that they were invitees and

had been refused service because of their race. The cases

cited do not support this contention while there are a

number of cases holding to the contrary. See Hall v. Com

monwealth, 188 Va. 72, 49 S. E. (2d) 369, 335 U. S. 875,

69 S. Ct. 240, 93 L. Ed. 418; Henderson v. Trailway Bus

Company, D. C. Va., 194 F. Supp. 423; State v. Clyburn,

247 N. C. 455, 101 S. E. (2d) 295; State v. Avent, 253 N. C.

580, 118 S. E. (2d) 47; Williams v. Howard Johnson

Restaurant, 4 Cir., 268 F. (2d) 845; Slack v. Atlantic White

Tower System, Inc., D. C. Md., 181 F. Supp. 124, 4 Cir.,

284 F. (2d) 746; Griffin v. Collins, D. C. Md., 187 F. Supp.

149; Wilmington Parking Authority v. Burton, Del., 157

A. (2d) 894; Randolph v. Commonwealth, ——- Va. ------ ,

119 S. E. (2d) 817. The Fourteenth Amendment erects

no shield against merely private conduct, however dis

criminatory or wrongful, Shelley v. Ivraemer, 334 U. S. 1,

O pin ion , S ou th C arolin a S u p rem e C ou rt

9a

68 S. Ct. 836, 92 L. Ed. 1161, 3 A. L. E. (2d) 441; and the

operator of a privately owned business may accept some

customers and reject others on purely personal grounds

in the absence of a statute to the contrary, Alpaugh v.

Wolverton, 184 Va. 943, 136 S. E. (2d) 906. In the absence

of a statute forbidding discrimination based on race or

color, the operator of a privately owned place of business

has the right to select the clientele he will serve irrespec

tive of color, State v. Avent, 253 N. C. 580, 118 S. E. (2d)

47. Although the general public has an implied license to

enter any retail store the proprietor or his agent is at

liberty to revoke this license at any time and to eject

such individual if he refuses to leave when requested to

do so, Annotation 9 A. L. E. 379; Annotation 33 A. L. E.

421; Brookshide-Pratt Mining Co. v. Booth, 211 Ala. 268,

100 So. 240, 33 A. L. E. 417; and may lawfully forbid any

and all persons, regardless of reason, race or religion, to

enter or remain upon any part of his premises which are

not devoted to public use, Henderson v. Trailway Bus

Company, 194 F. Supp. 426.

The lunch counter was closed, the lights extinguished,

and all persons requested to quit the premises. Defen

dants refused and their constitutional rights were not

violated when they were arrested for trespass.

Upon cross-examination of Capt. G. O. Bramlette of

the Greenville City Police Department, it was brought out

that the City of Greenville has an ordinance making it

unlawful for any person owning, managing, or controlling

any hotel, restaurant, cafe, etc., to furnish meals to white

persons and colored person except under certain condi

tions; and Defendants contend that they were prosecuted

under this ordinance; however, the warrant does not so

charge and there is nothing in the record to substantiate

O pin ion , S ou th C arolin a S u p rem e C ou rt

10a

this contention. The ordinance was made a part of the

record upon request of defendants’ counsel but defendants

were not charged with having violated any of its provi

sions. The question of the validity of this ordinance was

not before the trial Court and therefore not before this

Court on appeal.

Defendants further contention that the prosecution failed

to establish the corpus delicti is disposed of by what has

already been said.

We are of opinion that the judgment and sentences ap

pealed from should he affirmed; and I t I s So Ordered.

A ffirmed.

Oxner, L egge, Moss and L ewis, JJ., concur.

O pin ion , S ou th C a ro lin a S u p rem e C ou rt

11a

Certificate

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

1st the Supreme Court

Case No. 6032

City oe Greenville,

—against—

Respondent,

J ames R ichard P eterson, Y vonne J oan E ddy, H elen

A ngela E vans, D avid R alph S trawder, H arold J ames

F owler, F rank G. S m it h , R obert Crockett, J ames

Carter, D oris D elores W right and R ose M arie Collins,

Appellants.

I, Harold R. Boulware, hereby certify that I am a

practicing attorney of this Court and am in no way con

nected with the within case. I further certify that I am

familiar with the record of this case and have read the

opinion of this Court which was filed November 10, 1961,

and in my opinion there is merit in the Petition for

Rehearing.

/ s / H arold R. B oulware

The Court neither overlooked nor misapprehended any

of the facts set forth herein. Therefore the Petition is

denied.

/ s / C. A. T aylor, C.J.

/ s / G. D ewey O xner, A.J.

/ s / L ionel K. L egge, A.J.

/ s / J oseph R. M oss, A.J.

/ s / J. W oodrow L ewis, A.J.

Columbia, South Carolina

November 16, 1961.

3 0