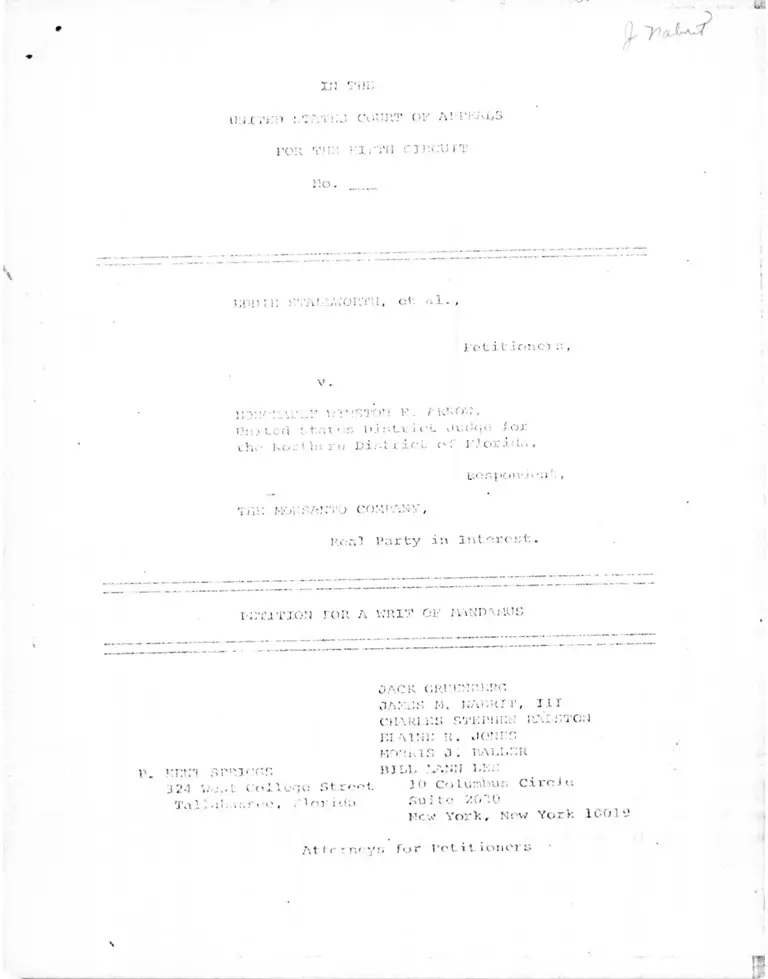

Stallworth v Arnow Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

March 24, 1975

31 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stallworth v Arnow Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1975. eb8c83f2-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/59657b05-eb1d-4272-85b2-5f8127e7b085/stallworth-v-arnow-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN

H t.TATJ

i Till:

; j CM!JUT OF AP I ’

ro l l y m :1 F I J “i'll CJ!’-CU i T

I lo.

I

\

HDD u: ■■ v.roP.i'ii, ci a i . ,

r e t 5 t lone: r.,

v .

l i m s t o n v?. i knov? ,

Led L-tnt';S l'»j ntf i ft OVu ’m o jO X.

thi: D i r . t r l e t o f F lo r ida .#

Dor.povi' !• m

T/ii: Mo n s a n t o c o m p a n y ,

Real P a r t y in t .

K1TJTION FOR A WRIT OF MANDAMUS

p. srpiec.r

S2A t C o i l c q o

j a c k o r f c m p h r c.

DAMNS M. NAHUIT, I H

c u a k i.k s sutipiuiu pa. i n t o ; j

riMHU u. jonnr.

K‘ *' -i -1 J . PjM jI lull

h i l l \a n :i l :;::

S t r e e t 3 0 CoLutnbur. C ir e J u

Suite 201:0

l ’ c,v Y o rk , New Y o rk 1001 v?

T a i l ul-.nsree , V l o r o.ia

,A1 terra v:. f«.>r Pot it. i oner u

H5

l\UJO

Petition 1 or a V.'rit of

Slot or.uut. of the Case

M.andai.us

Proceed i no.'; in the? District. Court

The Order of Re!crenct* of March 24 , ) 07 5

Quo:;t ion:; Presented

P.hASONS FOR CiV.MTJNC Tflb V.’IUT

Intreduction

J. The District Cour t. Had !*o Power to

Dele gate the Trial of All Ihr.v.a i n in< j

Liability Insues to a Special Master

Pursuant to Title Yll.

II. 'flic; District Court Had bo Power to

Delegate the Trial of A .11 Remaining

lr.sues of Liability to a Special Mas

ter Purr.uant; to Rule f>3(b).

Conclusion

Appendi>: A

K>: h i.b its:

1 . Order; elated 9/12/74 granting partial

suniiui ry ^judgment and pro 1 inti nary in —

;i’.inc Li on

2. Pre-trial order dated 12/20/74

3. Letter from Court to counsel dated

12/26/74

4. Order for iniunctive relief^deted

3/7/7 3

5. Order on proceedings dated 3/11/75

6 . Proposed order submitted by plain

tiffs on 3/12/75

7. Order on 1 aches dated 3/20/75

0. Order of reference to Special Mas

ter, dated 3/24/75

0. Motion to revoke order of reference

by plaintiffs dated 3/24/75

10. T: mr.cri pt (nartiu 1 ) of lustring on

March 24, 1075

1

2

2

1 0

16

1 7

17

1 9

2 5

!G

29

t

■i

i

t

l

\

m< «

11. Letters frow counsel to ttpeci

openj fving portiouu 01 rocuid,

3/2C/7 •’>

1 Master

d it ted

Certificate of Service

Ct rl i f i cate

The undersigned, one of the attorney;; for petitioner:;, cert i-

f ier; that the parties lifted below have an interest in the outcome

of this cause. This certification is made in order that Oudr.es of

the Court n;:y evaluate possible disqualification or recusal under

Local Ku1 a 13 of this Court.

1. The named plaintiffs, Eddie Stallworth, Henry Gholst.cn,

donas Fairlie and Jesse lord.

?. The class of black employees, former employees, and

rejected job applicants at Monsanto's Pensacola, Florida facility.

3. The Monsanto Company.

4. The Honorable. V.'inn ton F.. Arnow, United States Dis

trict Judge, northern District of Florida.

5. The Honorable Harold D. Crosby, Special Master.

IN TJ1K DNTTKD STATES COURT OF APPKA1.S

FOR Till: FIFTH CIRCUIT

KDDIII STALLWORTH, et. n].,

Petitioner:;,

v .

n o r o r a r t.k w i n s t o n r:, a rn ov?,

Uni ltd staler, District Judge for

t'nc Northern District of Florida,

Respondent,

THE MONSANTO COMPANY,

Re a 1 Party in Int cro s t..

P • - j T"-: QM FOR A V?RTT OF MANDAMUS

Pursuant to 23 U.3.C. r, 16f>l, Petitioners, by their

undersigned ;it t orncyr., move'this court to issue a writ of

mandamus directing the United Slates District Court for the

Northern District of Florida, Honorable Winston K . Arnow, Judge,

to vacate its order dated March 2*1, 1075 referring petitioners'

claims to a Special Master for trial on the merits, and directing

the court to proceed to a hearing of those claims as expedi

tiously as possible. Because the Special Master proposes to

begin proceedings on March 31, 1075 and to continue intermittent!

thereafter, petitioners pray that this Court expedite consider i-

t i on o f th i s r’ e t i l i on.

VI

petitioners cure compelled Vo nook n writ of mandamus by

the highly mu'ijual recent, proceed j ngs below. They have been

denied an opportunity to introduce any evidence in r.uppert of

the i r clair.* defendant war;, however, allowed to proceed to trial

on it:; defences. The case was then referred generally to a

Special Master for trial without meaningful guidelines, and in

circumstances ensuring substantial present delay. The reference

also raises the sub;st ant ia 1 pos s i b i 1 .i i y V h a t any decision

based on the Specin l Mas ter prooocdiiitj:; in vh .i c h f i ndi ngs of

fact and conclusion:s O f: I aw a.re made would be .i nvalid and WOU 1

require re-trial follow! no isppea 1 . Fill illy, the: refcroncc

prevents pi aintiffs from i nt roducing evidence before the court

that would support and require certain general findings already

made by the court on critical issues; at present those findings

are unsupported by specific findings or any evidence in the

record.

As grounds for issuing the writ, Petitioner's respectfully

show the foil owing reasons:

St. atomont o £ t he- Case

proc< '< _d ings i n the_p i strict; Court

1. This proceeding, Mo. 73-4 5--C.i v-P, N.D. Fla., Pensacola

Division below, is. a class action challenging Monsanto’s across-

the-board practices of employment discrimination, under 42 li.S.C.

<•'; 1901, 2000e-2(a). The four named plaintiffs, all black

employees of Monsanto, represent a class of more than COO present

employees, an unspecified number of retired or otherwise termi-

natcd black employees, and an unspecified number of discriminn-

torily rejected black job applicant:*?.

2. Petitioner.*?, plaintiffs below, filed their complaint:

on April' 13, 197?.. The complaint sought declaratory, injunctive.

and monetary r e 7i c f . There ): ad p r e v i o u s l y been f i l e d j.)) the

same court a r o l a ted c i v . i l a c t i o n .sty led Penial Pmpl oym< MVt

O. '"; o tu! t y Com i * ' ;! Mi Mot? i to ('o'.'.v itiv, No. 73 —31—tl i v-l>.

both cases were ass igned t o t ie Respondent ju d ge . Tin? two eases.?

were t heron ft* - r , on robruary 5, 3 974, eons io l ida ted f o r d i r.co v e r y

and in February, 1 97!> f o r t r i a .

3. 1)5. si co very and pre-tri a 1 inoti or\ procccding s have been

fj.d rns ivo in this case- , re rail ting ;in a ‘voluminous and detailed

record and ill a series of hearings? and confcronccs be fore■ t.he

Respond* ni judge. 3 he parties apptmred be fore the Reopenident

on at leant nix different occasion.*; prior to March 1, 3 97 b.

Among thc-:;c hearings van an evidentiary hearing conducted on

July 30-31, 1974 on plaintiffs' motions for preliminary injunction

and partial, summary judgment. The Respondent heard approximately

eight witnesses? and received voluminous? documentary evidence

including 29 plaintiffs' exhibits at that: time.

4. }-‘ol lowing the hearing described above, the court, on

September 12, 1974, granted plaintiffs?' motions? in part. Specifi

cally, it found that certain of defendant *s testing practices;

and its. high school education requi rumen t for certain jobs wore

unlawful. Tt thereupon enjoined those practices and granted

plaintiffs partial summary judgment with respect to those issuer..

It denied plaintiff*:' motions seeking judgment and relief ns? to

certain othei is. in to those latter issuer the court

1/

■s. At:

made no definitive f i ml i nys nisei reserved the issuer, for trial.

The issues presented at the motion lioarinq v/erc some, but less

2/

than ait, of plaintiffs' class: for injunct,ive relief. A copy

of the court ' ■ orders, granting and denying plnintiffs* notion.';

is attache:! hereto as Kxhibit " 1.".

b. on December 26, 197-1, the court filed a pre-trial order

sctt.i ny the case for trial beginning March 3, 197b and scheduling

further pre-trial procedures. Also on December 26, 197*1, the:

Respondent informed counsel fen* all parties by letter that the

court had set: aside the entire month of March for trial . Copies

of the pre-trial order and letter are attached hereto as

Dxhibits "2" and "3", respectively.

{>. A pre-trial conference was hold oh February 2*1, 197b.

At that conforencc , Respondent <■Xplessed the desire that the

case be concluded within the morit h set a:; i d c for trial but ind

cated, <is in the c:court's letter of Dccomljor 26 to counsel

(exhibit 3), that if additional time were necessary to try the

case the court, vould .seek to make such time available. Further,

the parties agreed lo explore the possibility of settling some

of the issues in the case.

preliminary relief and summary budgment was, denied as to a number of other issues, including various testing practices;,

Mensunto's seniority system, and discrimination in selection of

fore:;m-n. c 1 oricaJ s, and lechnici ans.

2/ i:• M • # in the* pre-tri al orde r filed on Fcbr nary 1 A, b'71.,,

p 1 a in Vi f1 s. list'd 19 d ispnted issues of fact. and 20 disputed

i s s ur *!% O f law (see part s VITi A, 1X A, and TX B of pre-trial

orde r) . Them* V» issue !*. were left open after resolution of about

b i ssues by the court's inter1ocutory orders.

oyuusuow 'jo A^t [Tqtryx .to *Aq uot j u u t.urxou t p jo nhurpiiTj ou opuui

puq la t io o o q j I ' L qoav>H j o .cop.to o q j o j jo x x d 6

•|,) I[;)J( [ t.’np t a t ptt c xoqyo puu Aud

qorjq _ioj A j t [ x q x P ’ f •■> A'[ put .xo A [ p o . t t p

-);>,); j e JtopJto srq.y tit L i iu p c ; ! ( 1C)

•popxtjMt? oq o:; 'Aui? j't ' sosuodxo

no i prh't i T][ put? sooj s , A au.io 4 "4 u » o junoum oq l

put.’ ioVinoiioi: tpjttTttoi jo■’ try > u n vv.in:u! o -4

j qfyi jl t>, OOMM t>t(4 1 Aui! jt 'aotpouox p-nptAipitc pi ipatMq .itt pxnpq:: - icoio qotxs utoq.A Act

.'P JX^T-HIO oq Ai.vi aoqui >ut satqo « tpiH--' °> 'Axtt? j c

'Aui'l qouq jo ^unoim; oq 4 Int t u c.u_t op jo poqjuut

;>q \ x ; J t -jut t> |'d Aq po yuoaO-UXO-l :;.f oquioni

jo) Aud qoi:q xoj A4 r y tqib 1 yo JO (•.;) po caod oq.J

i soqot.’ [ jo osuojop 1: , ;ut;puojop jo sons;: c oqi o.tu

j.mop rryqy jo .top-io ounjnj .xoj poAi.'>:o;l (<-,)

•ojuusuo'd Aq puxuop Aj oso-mio fut 1 oq qons

'ojuurjuoq Aq x o a o o jjeq.n Ajc ptcpi c 1 jo uotrAjupo

Aut.J JtVj’>l"|X.'\ O.JUj! poxc.vpt.') oT _C Op ro !.X I q.f, (t)

: (cl ' l *tid) J-Xt’d dT

' sopxAO.xd xop.xo oqj, ’ j o t i o . x A.tw4ouout pun A . - o i w t q a o p u o j sum? t o

xxxot['V |.ou 4r\ q J ox x ox OAX) ounCux joj s mc uf o ( •, jo. 1.1 l ’• ) > *1 _> J !• J

-u tq .q d p o A t o s o a ' sox 4-tud n q j J ° ju.wioo.tfin Aq qotq.A ' t iu oxstAO xd

oATjouiiCux po y x o y o p s o p n p u x .xop-to oq.T, ' v » 4Tfl ?llxd f' - 0

poqor’jjt; st aopxo qcqj jo Acloo V * <1 /.<■> X 'L qo.xcW *>o pojdopu

pttu poxribxs ]f qoxq.'A qjtnoo oq> 04 -tr>p:;o uu po 4 yriuqnn ApntroL

sotj-xud oqj ' suo c .4 u t .406011 6u o x --(o o m oqj j o -4 (ttso.i a o</ *H

qqoij JO po 4 sonbo.x

OJ .'O u&ux-tuoq AacxquopxAo ou jnq qoo.A 4 aq 4 tdtranp iquowioxoAap

jo j.tnoO nqj poarxcldu [ooutxoo ’puu sxqj 04 P-’Jou-paoo vJne-\

yuoxjuxiofjou oAXouojuX * P-'f-Vj 04 burpoooo.td oaojoq o«i?o oq.4

uc {.onus C oq 4 jo OUIO'J OXJJos 04 p;» idtuo >ju so yj-U'd oqj 's/.bl ' t!

qo.o?w jo v/toA oq 4 Oux.tixp ' tio t so t ut.to-'.(_ s , yxuoo vJ'jj U 4T»A L

with the- ] ini t od < >.c< pti.on of its findings of discrimination

contained in the orders dated September 12, 1974, Exhibit "I"

here to. for had.Monsanto consented or .stipulated t:o any such

f i nd j raj: .

10. The parties appeared for a mooting with the court, on

March 10, 107 5. The Respondent t hereupon announced Unit , in

hir. view, the March 7 order consti luted a f inding of class-wide

discrimination by Monsanto against the: plaintiff class. Purthor,

the: court announced its intention to proceed forthwith, hearings

to begin on March ill, 3 “75, t o hear evidence on two of Monsanto'::

affirmative .defenses s the alleged lac); o f , jurisdiction to enter—

tain the l.'ROC action (Ho. 73-3)) ; and the defense of leches t o

plaintiffs' had; pay claim in (Ho. 73-45). plaintiffs expressed

their objections to this procedure of hearing defendant'&

defenses before plaintiffs’ ease in chief.

13. On March 11, 1975, the court entered an order in light

of its parch 7, 1975 order. The March 11th order, attached

hereto as Exhibit "5", provides in pertinent, part,

2. Pack pay matters will, unless settled by l lie

parties between themselves, be referred at. an

appropriate- time to a master to make findings

and recommenda Lions.

3. Prior to reference the court will determine

the- issue of- lach.-s and the KECXT's rigid to

maintain its act.ion. It will also consider at

request cd part is s d< t ei min.it i on prior to

velerca'-e (oil such other issuer, as the parties, -

or any of them, believe will provide appropriate

guidelines, either for interlocutory appeal

purposes, or lor the master.

12. At the March 10, 1975 conference, the court had directed

plaintiffs to submit proposed findings of liability as to the

-r>-

nreas covered by the March 1, 1975 injunctive order. 1*1 aint i i 1 r>

submit fed such a proposed order on March l-?» 1975. 7\ copy

thereof .is alt celled as Exhibit "6" hereto. To thin date the

court, has entered no order t'iitdi.no liability, based on plain

tiffs 1 submission or otherwise.

13. On March 11, 1075, the court conducted a day-long

evident i v y hearing on issue-: related to the court's jurisdiction

over the hT.CC case (Po. 73-31). Pared on this evidence and the

arguments of counsel, the court on March 12, 1975 dismissed the

EEOC s u i t .

14. on March 3?, 1973, the court began an evidentiary

hearing on Monsanto's defense of laches. Plaintiffs were prepared

to begin their trial presentation; their opening witnesses and

exhibits wore present. The court, however, dec!inod to allow

plaintiffs to introduce any testimonial or documentary evidence

as to discrimination by Monsanto or the Company's liability

vet non for bad; pay or other monetary award. Plaintiffs objected

to this hearing of the affirmative defenses prior to and in the

absence of any opportunity for plaintiffs Lo present their

evidence of discrjminalion and liability.

15. Over these objection:;, Respondent continued to hear

evidence on the laches issues for four days, March 12-14 and

March 17, 1975. During this hearing, plaintiffs attempted to

introduce documentary c-vidence and witness testimony th.it would

ordinarily be part of their case in chief, as relevant to the

laches defense. Respondent refused to allow introduction of any

of plaintiffs' evidence of discrimination or liability. Based

- 7 -

March

1 r i n f ♦ ♦ $ ‘he Court on March 20, 1971.> 1•nter't'd an order

a i n t.iffS' bac): p cl ai rus t. 0 a ]c»r<;e ex11 cat ba 4ir red *by

ec j.>y is a tCache d as Exhibit ••7" lie1 et c» .

On !•1 ‘1 rch 1 7, 1 97 9 in a root.i on cii!tilled "Plaint iff:: '

corn' i n-j Tho sc issue s Still To Re Tr i cd Hy The Court /

mov eel t he 1court to try al 1 iss ue1 . * ref 11 'C ted in the i r

i nri.i’ 1 g s of fact ,and cone 1us ions of 1 aw. In tn0 i r

It; O f i on , pi:1 :i n t Iffs s p e d f ical iy Cel11 ed to the cour L * j

attention Chat. the only liability of record was the Kurm.iry

jndcjn.cnt order regarding two of Mormnnto ’ many tests and it*-.

)).ic;h school requirement . Plaint* £f« also explicitly opposed

t,'° reeferra) of pattern and practice iacuos to a Mauler.

1/. On March 17th, the court .indicated tl.it it had decided

to r < •lex* cm .ns.s-w.ule .issues of clj serin j nation to a fh-.ee j. a 3 Poster,

Llms denying plaint.i ffa '. motion of the same dale. The court,

again, indicated that it in to rpre tod the order of March 7, 1975

as a finding of class-wide liability.

.Id. Respondent had announced his intention to refer the

case t.o a Special Master during the week of March 10, 1979.

All parties submit Led motions and memoranda concerning the

reference; the plaintiffs preserved their objections to the

Special Master procedure.

19. On March 29, 1979, the court entered an order referring

the ca.e to a Special Master, the Honorable Harold c. Crosby,

for further proceedings. 7v copy of that order is attached hereto

ns Exhibit "11". The order of reference is analysed, infra.

20. On Kai*ch 23, 1975, p l a i n t i f f ? ; f i l e d a M ot ion to Revoke

the Ordor Appoi nt ing Kp

mot ion argued iIr.i L r c• fei

(a) tho cot:N- f- J. c. ad n ac; o i

issue, the 11 1ja r' a ui i non

and (b) the crv,irt war; w .i

1 at e sf age, V 1 th lhe i n l

the ] it i ga tio!*l . 'l'he cox

on the same dat e .

21. At an open court hearing immediately foil owing entry

of the order of reference, the Respondent introduced the special

Master to the parties and yielded the bend; to him. The Special

Master thereupon announced his intention to begin to hear the

case in the days open on his .schedule; during coining weeks (Tr.

3/

9~]1). The Special Master stated that nil hearings before April

1-1, 197S would be fox' tho purpose of' explaining the case to him,

dealing with motions and procedures, and hearing "short-range

type evidentiary matters," but not for trial of the main case

(Tr. 10-11).

22. Had the Respondent proceeded to hear plaintiffs' case

as originally scheduled, it is highly probable that trial pro

ceedings would have concluded before April )4, 1075. Under the

order of reference, .it is highly doubtful that the Special Master

proceedings— taking of evidence before the Special Master,

preparation of the Master's report to the court, specification

of objections thereto by the parties, designation and preparation

— The citation "Tr." is to a partial transcript of this March 24

1975 hearing, attached hereto ns Rxhibit "10".

-g-

of relevant- parts of the transcript' for the ’district judge— can

be completed for many months.

23. At. the March 24, 107!i hearing, the Special Master

rocfuoste 1 that the parties dcsi ynnto those port ions of the

massive record v.’hich he.* would need to revi<v jn order "to become

ticq ua i ntcd willi prior activity" in the case (Ti . 3 1). Counsel

for both s id e s have rcisnonded with letters indica t ing the noces-

sity for the Me!is tor tc> rc v} c-w n very ext en sivo amount of material.

see copi es of lottci*s attached ns Exhibit "13 A" and "33 B" hereto

The }t*•spendent judge was a] ready familiar with much of thi s

material.

The Order of_ Reference of Har d ) 24, 197 5

In the order of reference to the special Man ter, t ne dis-

tr i.et. court stated that it had "in effect" found that Monsanto

had discriminated against the class on the basis of its order

of March 7, 1075 (see Ex. "0", p.3). The court thereupon

referred all issuer, related to back pay liability to the Special

VMaster. Ex. "8 ", pp. 1-2.

The March 7 order will not support a finding of back pay

liability. The order was entered by the court on motion of the

plaintiffs. While it was not a "Consent Order" as such, the

under the law of this Circuit and the clear statutory command.

42 U.S.C. If ?t>00e-5 (g) r a findi iif i of diner i mi nv) t or / id f,yiiell t

Prac t i cos i s a j»rccomi i 1i oi i to any back paV i)Wa rd. Jn 1 ms on vt

("oedvear 'Ii r<[ • f, !:lublv'r c o. , A 0 1 J .2d 13 04 (i.th Ci r . 3 074) ;

Be It wav v. A:. or t c (M r. t T ron pit-e Co. , 40A r.2d 2 1 1 (5th C i r .

1 074) ; i’. i>:t < •I V . S d,fdnn '«ii rIlCI.ir i'efining Corp., 4 05 r. 2d 4 37

(i*th Ci r. J VV •*) ; 1<(M(: r lUhit' S. V • \'.i 4 S t. TCXd.h r,ot or i’rr*iqh t, 50i»

E. 2d AO (5th Ci r. id/-;).

p a r t i j - . ee ’ r i c a l 1\ * J L i p u 1 a 4' o d Ol 1

n o t i s S>O •; e i t s o n t r y r. o r w o n 1 il t h e

o a t h< •r i n t h e c!! i s t . »; i c■ 4- c o u r t . o r o n

t h e « n t /" V o : 1 1io o r cJc •r o f M a i . c?h 7

w a s a f i n d i n g 1>V t h a d i s t r i e t c o u r

1 i s t s — t h o Wont1! e r l i c is n d IJMC- a n d

r * • d i j ; c r i m i n s t o r y i . e p f . e m b i 1 2 ,

K x . " 0 " I* • ‘1 , y 10 -

•cl on the record that 1lu y did

seek reviev.' of the* order

ppoal. At the 1-jme of

* only liability of record

that two of Mo»r ento'r

The March 7 "Consent Order" contains only j.n;innc.*t:.i.ve pro-

video;;. 'j L oxpijci tly rec.ll.en that Monsanto admits no liability

and that liability in expressly denied by Monsanto (L*>:. "8 " p. 1

v 1) . It further reciter, tha t nothinq in the order shall

directly or indirectly be deemed to effect back pay or other

individual relief (id., >:■. 12, A 31).

The only class-wide liabilit.y found by the district court

in its Order of Reference bused on the March 7th Consent Order

are its findimjn of discrimination in the selection of tech-G/

nicians, clericals, and foremen (i_d. , p. 5, «j 11). These f indings

are supported by no specific findings, as to historical or

present employment, criteria or selection procedures, racial com

position of jobs, or other evidentiary matters.

The majority of the issues of class-vjdo discri ina1 ion

that plainti fs have sought to raise before the district court

Under thi

1o infer var

would shift

vidual class

s port i on of the Order, .it. is arguably imnermi ss.i hi

ion-, citterns and practice.'} of discrimination wh i ch

the bunion of going forward as to whether an indi-

1T" tr.ber suffered racial discrimination.

e

( > / J.t doe:; not .appear that the order

landing ttiat the s< si Lori t y system is

foe p. , infra. (j_d. , p.li, • C) .

of reference incIndies n

racially discriminatory.

11 -

have been referred to the special Master for fin initial

urination of liability ve 1 non. Of the 15> issues in the

the court lias attempted to resolve 3 issues by entering

deter—

.7/C ■' > s c ,

i ind ins:;

\ yof liability based on the March 7th "Consent Order"; the court

has resolved one issue completely by summary •judnuient for

*>/defendant

do fendnrit s

to the Mas

law on the

this case

a n d t w o i s s l i t r. p a r t . i a 1 l y b y s Ul r. i v . a r y j u d q m o n t s

1 0 /

• A 1 1 o f 1 ) » o 9 p i u s l ' e i t;i a i n i n g i s s u e s w e r e r e

t 0 r " t o m a k Q h i c f i m i l n g s o f f a c t a n d c o n e 1 u s i

i s : ; u e s r c m a i n i m i f o r r 0 s o l i d i o n a n d d e t e r m i i i a

it

for

ferred

ons of

t ion i n

Tc• 1. :i lie '! s . l i e : ;

Of the eiqht different kinds of tests and training programs

11/;it the defendant Comnanv, the court lias referred seven and pert

13/

of the eighth to the Special Master.

Plaintiffs' factual and legal challenge to these tests

based on disparate treatment analyses , illegal impediments to

J/ See Appendix 1\, jn_Tra.

1/ Cleric.il Personnel, Technicians, and Foremen (id., p. 3 , 5; II).

0/ Discharges, layoff and recall (i_cl. , p.2, 13(3)).

10/ Advanced Analytical Method of Training (AAMT) (id., p.2,

*[ B (1) ) ; more difficult work (ijd. , p.2, t 13(2)).

J 1 / All citations are to the March 2*1 th Order of Reference;

" M " ; Mechanic .Vsessmen t (p.-l, « I * ( 7) ) ; T n t erred i a ter. Assc

(p.4, «; 1 > (fl) ) ; hlectrici). .and Instrument.;; (p.*1, c p(0)); Pc

House, ’ .’or;. 1 .and 2 (p.d, « M(lO-ll)); Cere:-: pahr.e 2 (p. 5,

Manpower bevel opnent. (p. 3, <| J> ) ; and Phase in tests for

position (p.4, •; 0 (12)).

Fx.

.esn.ent

v.o r

•: I> (2) ) J. 1 III

12/ Advanced 7\n«a 1 y 1 ica 1 Method of Training

challenged; on 3, summary judgment granted

order of March 11 (p.2, •; 13(1), p.3, 1 D) ,

to Master (p.3, «; 0(3)).

(AAKT) ,

for clef

and 3 tc

Mix tests

emlant s by

sts referred

"ri ght 1 ul place" of rinse MHrbors, nr!>itr;irinrss of cut-off

scores, and in-pact and validation i nnucs h.ivo not been hoard

or determined by the. district court (see Appendix A, also ]>;. 0,

Order of Reference). A determination of the testing

is .sues wi] 1 have a profound effect on the back pay aspect of the

1itiga Li on.

Id ci<1 !KJ * • m

At the very heart of plaint i ff r. * ca.ee is the issue of the

discriminatory effect of tho defendant's "prior request" or

bidding system on tho class of GOO or more black:;. This class-

vide; pattern and practice issue has been referred to the- Master

for a determination of liability (id., p.5, \ p).

J*.eni ori t v by- t r ;.i

It does not appear from the Order of Reference that the

court has made u finding that the open: at ion oi the defendant

Company's seniority system is racially ’discriminatory (jid_. , p. 5,

5! (’) • liven had the court done so, the consent, order of March

7th, absent a record which plaintiffs, have; not been permitted

decided by the court; nor specifically referred to tho Mar.

However, tho general grant of unlimited authority to the

by the court permits the Master to hear these issuer, if Iv

or.

Ins ter

3.V ito nak e, provide• Jj no has is for such '" findings.• 1 S

7 7 ’ ,von w i t h a go tiera 1 finding of d:i scriminat i on on t he

ii

f;t in or i t ’y system » t liero a r<- speci fir unresolvc• d i S sue‘ s of the id i so fra ;nat.ory t. ( c(Ct o f t.kio r.eniru i tV system, such ais the. total *c.vcl n. i i o:a of bl ic: kt * rroir. t !v; initial at a f f .ing of nev.’ly c rt 'a t od •-

jobs n t t.lic ■ del»*n< 1ant Co : . ! > t iin-/. Thes< • issues h;avu nr a been %

chooses (id., p.7 1 )

-1 .1-

Hiring and Tnitiul A nr..inn::̂ 'nt

Both the insuos of c 1 ass—wi d o discriminatory hiring and

the ini tial assignment prnct ices of the defendant Con.pany have

been referred to the Master for findings of liability (id., p.C,

V 1 ) . Any relief lor the largo class of black job applicants

represented by plaintiffs would depend upon his finding.

Other J ssues

The following issues were also referred in tot o to the

Special Master without any prior findings, 1 imitations, guide

lines or instructions for resolution: whether the defendant

Company engages in a policy of firing and payment of salaries

to members of the class who are salaried employees (Kx. ' B" ,

«: J at p.C) ; whether there is a clns.s-wid.o pract ice of di serimi.—

natory appl ication of medical disqualifications in order to

exclude blacks from employment and promotion (Ex. "0" , «: K at p.C)

what general theory or methodology should be applied to back

pay calculation (Ex. "8" , *j; b at p.C); and such questions as

attorney's fees and defendant's liability for adjustments to

pension and retirement programs (Ex. "0"* at pp. 6-7).

Tn addition, the Master has been given the power to delimit

the issues which the district court will certify for interlocu

tory appeal. Although both parties presented their positions

on issues which the district, court should certify in extensive:

written submissions, the entire matter was referred to the

Master (lx. "0" , 3 at p.C).

Further, by the Order of Reference, plaintiffs are precluded

from presenting evidence before the Master which will provide a

-Id-

arcba.«-sis for those findings that: the district court states

supported by the March 7th order. The district court has pre

cluded the Muster iron, inquiry .and plaintiffs will not be

allowed to malic a record on those issues (l'.x. •’o” , y c and II at

P.5).

OP; ViT'J isi 1.1'-'-'jdb'b')

Di.il I he? district court abuse its discretion when, niter

two years of litigation and a week of evidentiary hearings on

defendant1r defenses, it referred the "remaining issue?;" which

included virtually the entire case, to n Special Master for

plenary determinations;

1 . Under § /06(f) ('») of Title. V'.LJ, which provides for use

of must- rn in narrow circumstances where reference will expodj to

resolution of the case?

2. Under Rule .13, pod. )\. civ. lb, which allow:; reference

of cases to n master in exceptional circumstances?

- i r>-

T!IF. V!RT1RJl'J'.Ob'S ! OR *1(1

I nt ;ct ion

Plaintiffs have not boon permitted to try their lawsuit

before the district court . The court lias refused to hoar any

proof of defendant company's liability; the only issue tried

by the court is the company's defense of laches. Nevertheless,

the district court has made goncrul findings of fact on severe.]

liability issues. In support of this determination, the court

cites the consent order of March 7, 1775 dealing with appro

priate .injunctive relief as "in effect" finding that the company

is 3 iable to plaintiffs. The con sen 1 order, however, states;

"This order is entered without any admission of liability what

soever by Monsanto, such being expressly denied by Monsanto."

Moreover, the consent order fails even to address most of the

issues of liability plaintiffs have alleged. in these circum

stance's., reference to a master to hear all unresolved issues,

to recommend findings of fact and conclusions of law, and proposed

judgment means th.it the district court has essentially delegated

the trial of the lawsuit.

The reference is all the more extraordinary because of the

subject matter of the law.suit, racial discrimination in defendant

company's employment practices. ]t would bo difficult to

• . . /imagine a case whoso trial before an experienced federal district

judge is more necessary or important, see Donne 1 1_pougl as

Core, v. Green, 411 U.S. 791, 800-07 (1073); Hutchings v . m i. tod

States industries, 428 P.2d 303, 3)1 (0th Cir. 1070). The

district court's delegation of the greater part of a trial to a

- 1(, -

9

special master i s unpreccdenl ed in Til In VII and civil ri ghtn

1 it i.fjat:ion ijonernlly, iind was bascii on .1 novel construction of

it recently enacted Title VTI provision concerning reference.

This Circuit has hitherto not considered whether this or any

district court can delegate a Title v n trial on such a basis.

issuance of (lie writ of mandamus to review the district

court's reference to n spec! it 1 master is appropriate when the

reference is a clear abuse of discretion that "amounts to

little less than an abdication of the 'judicial function doprivi

the parties of a trial before the court on the basic .issues

involved in the litigation," bn levy v. powes heather Co., 3 52

lb S • 24 9, 256 (1957) and "nullifies the right to an effective

trial before a constitutional, court," In re v.’atl; i nr., 271 p. 2d

271 , 27a cir. 1 9 5 9 ) ,* TPO, Inc, v. Mcy.il Ion, 460 P. 2d 348

(7th Cir. 1972); Trerar.i v. Kiel)a rdson , 4 71 r. 2ii 12 68 (7 th Cir.

1972). Compare peacon Tl cat m s , ■i *, v . V.vStf )VC;jr, 359 U.S. 500

511 (1959). This unpre:ccden fed dole ga t.i.on of a T.i t.l e VII case

is also an "issue of first impression" proper for the exercise

of thin Court's supervisory power, Schl agenhauf v._Hrd dor, 379

U.S. 104, 110-12 (1904), in which "the writ serves a vital

corrective and didactic function," bill v. United states, 389

IhS. 90, 107 (1967). compare Panders v. Kusse 1 1 , 401 p. 2d 241

(3 th Cir. 1908); United r-lnt.es v. Hughes, 413 p. 2d 1241, 1 248-

4 9 (5th Cir. 1969).

Plaintiffs have repeatedly objected to the reference and

sought its revocation below, without success. Absent the writ.,

plaintiffs have no .adequate remedy. "The remedy of an appeal

- 1 7 -

*

from the final judgment would scarcely he adequate, and if

successful in overturning an adverse judgment flowing from the

reference, would, at the price of [another] trial, demon?'tra to,

an presently contended, that only one was permitted." in re

y.'<~» thins, supra , 271 F . 2d at 275; TPO/__JI__nc._v._McM.i lieu, supra,

400 F. 2d at 362; cf. 1~1 ovK-rs v. C^ouch-V.Aal her Corp. , 8 EPD

*39046 (7th Cir. No. 74-1163, December 18, 1974).

T1JE DISTRICT

Ti3S TRIAL OF

TO A SPECIAL

COURT HAD NO POWER TO D3

A LI i REMAINING b lA D IL IT Y

MASTER PURSUANT TO T IT LI

LEGATE

JSSUUS

: vil.

The order of March 24 refers broad issues, including most

of the claims made in this case, nearly two years after the

complaint was filed and after the commencement of trial by a

judge who had become familiar with the issues, to a Special

Master who had no previous exposure to the facts, issues, or

proceedings, and no prior experience as a judge in similar cases.

The inevitable effect of this reference will be to delay resolu

tion of this case by a substantial period. This result is

inconsistent with the statutory provision under which reference

was made.

The Me aning of JL 706(f)(5)

In support of the reference, the district court order cites

§ 706(f) (5) of Title VII of the Civil Rights 7>ct of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000o-5(f) (5) . Section 706(f)(5), added

by the 1972 Amendments, is a narrowly drawn provision:

- 1R -

It shall be the duty of the judge designated

pursuant to this subsection to assign the case

tor hearing at the earliest practicable date

and to cause

exnodi ted.

he case to be in every way

such judge has not scheduled the

case for trial within one hundred and twenty

days after issue has been joined, that judge

may appoint a master pursuant to Rule 53 of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

On its face, the district court's discretionary power to appoint

masters can only be used to discharge the mandatory "duty" "to

assign the case for hearing at the earliest practicable date

and to cause the case to be in every way expedited." Furthermore,

two other conditions must be met: (1) the specific period for

reference is when the "judge has not scheduled the case for

trial within one hundred and twenty days after issue has been

joined"; and (2) the appointment is made "pursuant to Rule 53

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure."

Further light on the meaning of § 706(f)(5) is shed by its

sister provision, § 706(f)(4):

In the event that no judge in the district is

available to hear and determine the case, the

chief judge of the district, or the acting

chief judge, as the case may be, shall certify

this fact to'the chief judge of the circuit

(or in his absence, the acting chief judge) who

shall then designate a district or circuit

judge of the circuit to hear and determine the

case.

This provision plainly expresses a preference for judicial trial.

If the two provisions are to be read consistently, § 706(f)(5)

cannot be construed to permit the unlimited use of masters. To

do so would be to effectively nullify § 706(f)(4).*

Congress intended that reference serve the limited purpose

of expeditious adjudication of litigation at a particular stage.

The House-Senate Conference Committee Report states:

19

Section 706(f)(4) and (5) — Under these para

graph:;, the chief judge in required to designate

a district judge to hear the case. if no juoge is

available, then the chief judge of the circuit

assigns the judge. Cases are to bo heard at the

earliest practicable date and expedited i;i"every

v’av. If the jndco has not scheduled tin: case for

trial within 13 0 days after is.sue has been foTncri

he may appoint a raster to hear the case under

Rule 53 of the Federal Rules of C i. v i 1 Procedure.

The purpose of this provision is to relax the”'"very

strongest requirements of Rule 53 which preclude

appointment of a master except in extremely unusual cases.

Senate Comm, on Labor and Public Welfare, Legisla

tive History of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Act of 1972, 92d Congress, 2d Sens. 1731 (1972)

[emphasis added]

Congress intended only that the purpose of expeditious adjudicatio

of Title VII cases may be considered a presumptive "exceptional

circumstance" within the meaning of Rule 53(b) for this class

of references. This legislative history also confirms that

reference is proper under § 706(f)(5) only during the period

a trial had not been scheduled 120 days after joinder of issue.

This assessment of § 706(f)(5) is consistent with the inter

pretation of the Seventh Circuit in Flowers v . Crouch-Walker

Corp., supra, the only other court known to have considered the

metoning of the statute. The issue in Flowers was whether an

automatic reference pursuant to a local rule of court assigning

all Title VII actions to a full-time magistrate is consistent

with § 706 (f) (4) find (5). The Seventh circuit vacated the refer

ence .

In language that is unmistakably clear, Congress

has imposed upon the judges of the court themselves

the duty to assign cases under the Civil Rights Act

of 1964. It has indicated_a preference to have the

case hoard by a judge, and has authorired the anpoTnla

ment o f a master_to hear such a_case only when a

particular picigc lias determined that ~~t~hat siTocYf ic

20

case cannot be- heard within 120 dnvs after issue

has been -joined. [en.phasis acidedJ 8 EPD at p. 6511.

Inapplicability of <: 706 (f) (5)

Reference to the special master for trial of practically

the entire case clearly docs not serve the express statutory

purpose of expediting the adjudication of this litigation. The

master's lack of experience in adjudicating federal Title VII,

civil rights or labor law matters; the total unfamiliarity of

the master with the facts and prior proceedings; the need for

the parties to acquaint the master with the facts and prior

proceedings before he is able to hold hearings; and the inter

mittent nature of hearings owing to other commitments of the

master all emphasize that such a reference will counter rather

than assure expeditious adjudication. This is true here, see

pp. 8-9 , supra, and generally. It lias long been known that,

"There is no more effective way of putting a case to sleep for

an indefinite period than to permit it to-go to a reference

with a busy lawyer as referee." Vanderbilt, Cases and Materials

On Modern Procedure and Judicial Administration 1240-41 (1952)

quoted in La Duv v. Howes Leather Co., supra, 352 U.S. at 253

14/n . 5.

\a / "it is a matter of common knowledge that references greatly

increase the cost of litigation and delay and postpone the end

of litigation. References Eire expensive and time-consuming.

The delay in some instances is unbelievably long. Likewise, the

increase in cost is licayy. For nearly a century, litigants and

members of the bar have been crying, against this Eivoidable

burden of cost and this inexcusable delay." Adventures_in Good

Katina, Tnc. v . Best Places to Eat, Inc., 131 F.2d 809, 815

(7th Cir. 1942).

See also 9 V.'right & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure

§ 2603 (1971). ---------------------------------

] -— 2

This is not to say that no reference can ever contribute

to speedy adjudication. Quite clearly, adroit reference of

discrete tasks to a master can assist the judge in processing

a case. The guiding principle has always been that: "The use

of masters is 'to eiid judges in the performance of specific

judicial duties, as they may eirisc in the progress of a cause'

Ex p arte Peterson, 253 U.S. 300, 312 ... (1920), and not to

displace the court." I.a Buy v. Howes Leather Co. , supra, 352

"U.S. at 256 (emphasis added). In contrast, the reference order

of March 24, 1975 referring essentially the entire case for

J_C/

trial is completely open-ended.

Section 706(f)(5) is inapplicable on another ground as well.

The reference was made after the district court had begun to

hear and determine the case and had already tried the defense

of laches; it did not occur in the period of a judge not having,

scheduled the case for trial within 120 days after joinder of

issue. it is during this specific period that the services of

a master are most needed to resolve discovery disputes and

otherwise assist the district court to complete trial preparci-

tions so that a trial can shortly be scheduled. To read § 706

(f)(5) to require that a reference may be made at any time is

contrary to the plain and reasonable meaning of this statutory

requirement and would impart an unlikely meaning as well.

IF E.g., specific assignment to resolve

discovery; specific assignment to make a

tion of the admissibility of evidence; s

handle matters of account and of difficu

disputes concerning

preliminary determina-

pecific assignment to

It computation of damages.

16/ See Exhibit " 8 ", p. 7, para. N, and p. 7 , para. 1.

r

22

Reference would depend on a wholly fortuitous circumstance, i.c.,

whether the trial was scheduled before or after 120 days after

17/joinder of issue. Congress cannot be presumed to have chosen

such an artificial ernd unreasonable meaning.

/vvoidance of unconstitutional itv

Even if § 706 (f) (5) could be read to permit, the instant

reference, this court would have to consider the constitutionality

of that, provision. Reference that "amounts to little less than

an abdication of the judicial function" clearly raises questions

of invalidity under Art. Ill and the due process clause of the

Fifth Amendment. Such questions have always lurked behind

decisions such as La Buy, supra, and In re Watkins, supra. in

Flowers v._Crouch-Walker Coro., supra, the Seventh Circuit alluded

to them even while stating that they need not be reached.

Inasmuch as the rule adopted by the Northern

District of Illinois flouts the statute, we find

it unnecessary to consider the broader questions:

whether the principle of the ha Buy case inter

preting Rule 53 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, or the radiations of Article h i of

the United States Constitution, or the restraints

of the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment

to the United States Constitution would also

condemn the local rule. 8 EPD at p.6511.

Therefore, avoidance of unconstitutionality, a traditional canon

of statutory construction, disfavors the expansive interpreta

tion of § 706(f) (5) reference that the district coxirt relied

any time, then two arbitrary

those for which trial had not

joinder of issue which could

be referred at any time; and (2) those for which trial had been

scheduled within 120 days of joinder of issue which could not

be referred under § 706(f)(5).

•— -'If a reference can be made at

classes of cases would exist: (1)

been scheduled within 120 days of

23

I I .

18/on.

THE DISTRICT

THE TRIAL OF

TO A SPECIAL

COURT HAD NO POWER TO DELEGATE

ALL REMAINING ISSUES OF LIABILITY

MASTER PURSUANT TO RULE 53 (b) .

The district court's March 24, 1975 reference order states

that the reference is "permitted ... under the rule," i.e., Rule

53, Fed. R. Civ. Pro. However, the order fails to make a Rule

-53(b) "showing" that some "exceptional circumstance" requires

reference, other than "the court notes for the record that this

case has been pending since April 13, 1973, and that the under

signed is presently serving as the only judge in a two-judge

19/

district." This reason, construed cither as calendar congestion

or unavailability of a judge, is generally not a cognizable

exceptional circumstance under Rule 53 (b) and specifically not

in a Title VII case.

~J—' Avoidance of unconstitutionality has figured prominently in

judicial interpretation of the Federal Magistrates Act, 28 U.S.C.

§ 031 et seq. See, e .g ., 20 U.S.C. § 636(b) (scope of assignment

to magistrates expressly limited to only "such additional duties

as are not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws of the

United States), and V.’i ngo v. Wedding, 41 L.Ed.2d 879 (1974),

affirming 403 F.2d 1131 (6th Cir. 1973) (heldu Act did not change

the requirement of the Habeas Corpus Act that federal judges

personally conduct habeas corpus evidentiary hearings). See

also TPO, Inc, v. MeMil Ion, 460 F.2d 348, 352-54 (7th Cir. 1972).

In construing a similar proviso in $ 706(f)(5) of Title VII,

the experience of other circuits disapproving similar references

pursuant to § 636(b)(1) of the Federal Magistrates Act and Rule

53(b) in order to avoid unconstitutionality in such cases as

Ingram v. Richardson, 471 F.2d 1263, 1270-71 (6th Cir. 1972) and

TPO, Inc, v . McMi11 on, supra, is entitled to great weight.

̂V It should be noted that the district court original ly set aside

the entire month of March and additional time into April, if

required, for the trial of this lawsuit even though Respondent

was then the only judge in the district, supra . That the case has

been pending since April 13, 1973 by itself docs not necessarily

*

Rule 53 (b) and Calendar Conrrestion

Rule 53 (b) clearly states "A reference to a master shall

bo the exception and not the rule." in La Buy v . Howes Leather

Co., supra, the Supreme Court has definitively established that

calendar congestion per so is not an "exceptional circumstance"

justifying the reference of practically an entire trial. More

over, in La_Buy, the district court had tried to show that

calendar congestion in combination with the prospect of a lengthy

trial and the complexity of issues posed an exceptional circum

stance for reference of an antitrust trial.

But, be that iis it may, congestion in itself

is not such an exceptional circumstance as to

warrant a reference to a master. if such were

the test, present congestion would make refer

ences the rule 'rather than the exception.

Petitioner realises this, for in addition to gedti< casescalendar congestion he alleges that the

referred had unusual complexity of issues of

both fact and law. But most litigation in the

antitrust field is complex. it docs; not follow

that antitrust litigants are not entitled to a

trial before a court. On the contrary, we believe

that this is an impelling reason' for trial before

a regular, experienced trial judge rather than

before a temporary substitute appointed on an

ad hoc basis and ordinarily not experienced in

judicial work. Nor does petitioner's claim of

the great length of time those trials will require

offer exceptional grounds. The final ground

asserted by petitioner was with reference to the

voluminous accounting which would be necessary in

the event the plaintiffs prevailed. We agree

that the detailed accounting required in order to

determine the damages suffered by each plaintiff

might be referred to a master after the court has

determined the over-all liability of defendants,

provided the circumstances indicate that the use

of the court's, time is not warranted in receiving

proof and making the tabulation. 352 U.S. at 259.

19 / (cont' d )

indicate that

Respondent has

ceedings over

with the case

reference is desirable or not. However, because the

been in exclusive control of all pre-trial pro-

this period, no Master could hope to bo as familiar as Respondent.

Calendar congestion has, of course, grown worse since La Buy

2 0 /but there has been no change in Rule 53(b) law. This inter

pretation of Rule 53 (b) comports with the duty of courts to

construe the statute in order to avoid unconstitutionality for

violation of Article III and the due process clause of the Fifth

Amendment, supra.

A district court's claim of "exceptional circumstance"

requires a close assessment of the record by a Court of /appeals.

The rule of this Circuit is that the claim must be tested issue

by issue so that reference of an entire case for trial including

"issues of a kind traditionally for judge or jury as fact finder"

is necessarily rare. In re Watkins, supra, 271 F.2d 774-75.

In the instant case, the district court failed to specify which,

if any, of the issues posed problems of calendar congestion

sufficient to offset the necessity for adjudication by an Article

III court. Such a specification serves a prophylactic purpose;

otherwise this or any district court could "turn the tables on

the rule and make trial by reference the visual, and trial by

court or jury the exceptional." In re V.1 atkins, supra, 271 F.2d

-lO-X In Tnqram v . Ri chnrdson, supra, for example, concerning a

local rule of court automatically assigning social security dis

ability insurance case to a magistrate, the Seventh Circuit

recently stated:

Crowded court calendars may be a problem in the

United States District Court for the Eastern Dis

trict of Kentucky. Reference of cases to Magis

trates, however,, is not the proper solution of the

problem. The proper solution of a crowded docket

rests with the Congress. District Courts, of course,

can do much and, ns pointed out in I,a Buy, have done

much, to relieve crowded dockets by sound judicial

administration and enlightened procedural techniques

(352 U.S. at 259, 77 S.Ct. 309); but the problem of

a crowded docket must not bo allowed to close the

25

at 774.

JS 706 (f)(4) of Title VTI and Unavailability of n judge

It is somewhat anomalous that the district court seeks to

justify the reference of a Title VII case to a master pursuant

to Rule 53(b) by citing the fact that he is the only judge in

the district. if it is meant that no judge is available to hear

the case. Title VII provides in § 706(f)(4) a specific procedure

for resolving the problem by certification of unavailability

by the chief judge of the district to the chief judge of the

circuit who "shall then designate a district or circuit judge

of the circuit to hear and determine the case." Thus, Congress

has expressly provided a way for district courts to relieve

problems of congestion resulting from Title VII litigation.

Here, the district court conducted two years of pre-trial pro

ceedings and litigation, and tried defendant's case for a full

week, without seeking to invoke outside assistance.. Only after

dismissing EEOC and severely limiting plaintiffs.' monetary

claims c:id the district court seek the assistance of a non—

Article III judge. it was an abuse of discretion for the district

court to resort instead to "self help" in violation of both

Title VII and Rule 53(b).

(cont'd)

door to a litigant who lias a statutory right of

review by a court. 471 F.2d at 1271.”

See also Flowers v. Crouch-Walker Corn. supra, 8 EPD at p.6511.

27

CONCLUSION

Reference by the district court to a special master for

the trial of this Title VII action has no basis in lav/ or

public policy. In no way would expeditious adjudication be

promoted and no other proper purpose is served. The instant

broad reference- order is in no v/ay comparable to and finds no

support in the specific reference of back pay calculation in

Title VII cases, see, e . q. , Pettway v, American Cast Iron Pine

Co., 494 F.2d 211, 250 (5th Car. 1974), which is valid under

both § 706(f)(5) of Title VII and Rule 53(b). Because the

district court lias clearly abused its discretion, a writ of

mandamus to require a judicial trial should issue.

Respectful ly submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES H. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

ELAINE R. JONES

MORRIS J. BALLER

BILL LANN LEE

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

Now York, New York 10019

P. KENT SPRIGGS

324 West College Street

Tallahassee, Florida

Attorneys for Petitioners

28