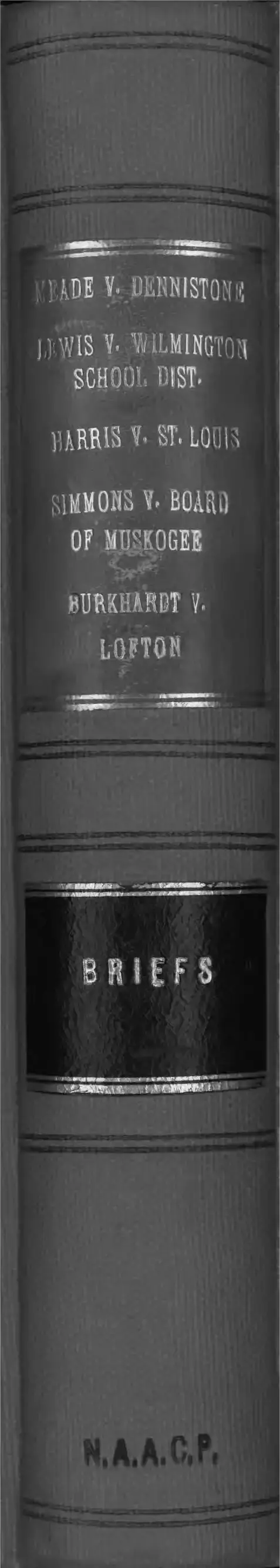

Meade v. Dennistone, Lewis v. Wilmington School District, Harris v St Louis, Simons v. Board of Muskogee, Burkhardt v. Lofton Brief Collection

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1937 - January 1, 1942

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Meade v. Dennistone, Lewis v. Wilmington School District, Harris v St Louis, Simons v. Board of Muskogee, Burkhardt v. Lofton Brief Collection, 1937. ef07c259-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/597b377d-c8ae-4cc1-9390-9b5571e58caa/meade-v-dennistone-lewis-v-wilmington-school-district-harris-v-st-louis-simons-v-board-of-muskogee-burkhardt-v-lofton-brief-collection. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

] ): W I S V. 1 I L M 1 N G T Q M

SCHOOL BIST-

HARRIS V. ST. LOUIS

SIMM O H S V . BOAR D

OF M U SKOGEE

humharbt y.

LOFTON

E dward Meade

vs.

M. E stelle D ennistone and

Mary J. B ecker.

I n T he

Court of Appeals

Of M arylan d .

October T erm, 1937.

General D ocket No. 26.

APPELLANT’S BRIEF.

W. A. C. HUGHES, JR.,

Solicitor for Appellant.

The Daily Record Co. Print, Baltimore.

E dward Meade

vs.

I n T he

Court of Appeals

Of Maryland.

M. E stelle D ennistone and

Mary J. B ecker.

October T erm, 1937.

General D ocket No. 26.

APPELLANT’S BRIEF.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

The record presents an appeal from a final decree

passed by the Circuit Court of Baltimore City, granting

a permanent injunction, restraining the Appellant Meade,

his heirs and assigns, from using or occupying premises

No. 2227 Barclay Street and perpetually enjoining and

restraining him, or any one on his behalf, from procuring,

authorizing or permitting any Negro or persons of Negro

or African descent to use or occupy No. 2227 Barclay

Street.

QUESTIONS IN CONTROVERSY.

Question / .

Does enforcement of a neighborhood covenant forbid

ding the use or occupancy of a house by Negroes or per

sons of African descent violate the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States?

The Court below held it does not.

The Appellant contends that it does.

2

Question II.

Is the covenant contrary to public policy and therefore

unenforceable?

The Court below held that it is not.

The Appellant contends that it is.

Question III.

Does this covenant run with the land so as to bind the

Appellant Meade, or is it merely a personal covenant,

binding only upon the contracting parties?

The Court below held that the covenant runs with the

land.

The Appellant contends it is merely a personal cove

nant.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS.

On November 14, 1927, No. 2227 Barclay Street, a resi

dence property in Baltimore City, was owned, as tenants

in common, by Anna M. Tighe, Francis L. Tighe, Mary V.

Tighe and Anna R. Gugerty, (hereinafter called the

Tighes), all of whom signed the covenant hereinafter re

ferred to. The Tighes conveyed the property to Florus

Barry, who then conveyed it to Mary Y. Tighe and Anna

R. Gugerty, from whom Frank Berman purchased the

property (R. pp. 10, 14, 15). On October 22, 1936,

Frank Berman sold the property in question to the Ap

pellant Meade, a Negro, for a consideration of $1,100.00,

of which $150.00 was paid in cash, balance to be paid

monthly, on conditional sales agreement (R. p. 10).

Meade moved into possession and occupied the property

prior to the filing of the Bill of Complaint.

On January 27, 1928, there was recorded among the

land records of Baltimore City, a covenant signed by

3

eighteen (18) property owners in the twenty-two hun

dred block of Barclay Street. The Tighes were among

these signers. Each of these signers covenanted for

himself, his heirs, successors and assigns, “ That neither

the said respective properties nor any of them nor any

part of them or any of them shall be at any time occupied

or used by any Negro or Negroes or person or persons

either in whole or in part, of Negro descent or African

descent except only that Negro or persons of Negro or

African descent either in whole or in part may be em

ployed as servants * # * nor shall any sale, lease, dis

position or transfer thereof be made or operate otherwise

than subject to the aforesaid restrictions as to and upon

use or occupancy * * * shall run with and bind the land

and each and all of the above mentioned properties and

premises and every part thereof * * * but no owners

or occupant is to be responsible except for his, her or its

acts or defaults while owner or occupant * * *” (R. pp.

11, 12, 13).

There are twenty-nine properties in the block in ques

tion and the owners of 11 properties refused to sign this

restrictive covenant. One colored family owns and lives

in 2238 Barclay Street at the present time.

The agreement dated on November 14, 1927, was pro

posed as a result of a meeting of the property owners in

an area of twenty-four square blocks bounded on the

north and south by Twenty-fifth Street and North Ave

nue and on the east and west by Barclay and Charles

Streets. Some time before the meeting, a colored family

moved into the 2300 block of Guilford Avenue, and at the

time of the meeting there were rumors that a colored

family was to occupy one of the vacant houses on Barclay

Street. Twenty-third Street from Guilford Avenue and

4

G-reenmount Avenue, Twenty-second and a half Street,

and most of Twenty-fourth Street are occupied by col

ored people. All of these are cross streets and Twenty-

second and a half Street is an alley. Twenty-third Street

and Twenty-second and a half Street have been colored

since the War. The twenty-three hundred block of Guil

ford Aveue is occupied by colored people. Brentwood

Avenue, a narrow street, running from North Avenue

to Twenty-fifth Street, between Barclay Street and

Greenmount Avenue, is also occupied by colored people.

There are two (2) colored churches on Twenty-third

Street near Barclay (R. p. 15).

Mary J. Becker, one of the Complainants, testified that

when she signed the restrictive covenant, it was with

the understanding that the whole area, comprising twen

ty-four blocks, was to be restricted and had she known

the whole area would not be restricted, she would not have

signed the agreement (R. pp. 16, 19, 20). She further

testified she did not own the ground her house was built

on and that the owner of the ground did not sign the

agreement (R. p. 17). Mrs. Becker testified that none of

the signatories to this agreement had any financial or

property interest in her house and she had none in theirs

(R. p. 18). The house next door to Mrs. Becker, No. 2236,

has no restrictions on it.

M. Estelle Dennistone, the other Complainant, testified

that she understood all of the property owners would sign

the agreement and she did not know all had not signed,

but that she would have signed the agreement irrespec

tive of this (R. p. 20). Mrs. Dennistone owns No. 2221

Barclay Street. The property next door to her is not

subject to this agreement (R. p. 21).

5

ARGUMENT

QUESTION NO. I.

ENFORCEMENT OF A RESTRICTIVE COVENANT IN WHICH

PEOPLE IN A NEIGHBORHOOD MUTUALLY AGREE THAT

THEIR RESPECTIVE PROPERTIES SHALL NEVER BE USED OR

OCCUPIED BY NEGROES OR PERSONS OF AFRICAN DESCENT,

EXCEPT AS SERVANTS, AND THAT ANY SALE, LEASE OR DIS

POSITION OF THE PROPERTY SHALL BE SUBJECT TO SUCH

RESTRICTIONS, VIOLATES THE 14TH AMENDMENT TO THE

CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES AND THE UNITED

STATES STATUTES.

The decision of the Supreme Court in Buchanan vs.

Warley would seem to have settled the question of segre

gated housing for all time. In a lengthy opinion, the

Court plainly held that the Fourteenth Amendment was

intended to guarantee to white and colored persons alike,

the right to buy, sell and occupy real property without

restriction based exclusively upon color.

Buchanan vs. Warley, 245 U. S. 60.

But that which was determined impossible of accom

plishment by Federal or State action now sought a new

method of evasion. Groups of people entered into mu

tual covenants not to dispose of their property to Ne

groes. A majority of the Courts of this country have

held that restraints upon alienation of property to Ne

groes are unenforceable because they are against public

policy. In the instant case, the restraint is upon occu

pancy, not alienation. The right of Negroes to acquire

property is assured and no longer subject to question.

Section 1978 (8 U. S. C. A. 41, 42) passed pursuant to

the Fourteenth Amendment, reads as follows:

“ All, citizens of the United States shall have the

same right, in every State and Territory, as is en

6

joyed by white citizens thereof, to inherit, purchase,

lease, sell, hold and convey real and personal prop

erty.”

The right to use or occupy property is an inseparable

concomitant of ownership and equally protected.

“ Property is more than the mere thing which a

person owns. It is elementary that it includes the

right to acquire, use and dispose of it. The constitu

tion protects these essential attributes of property.”

Buchanan vs. Warley, supra.

Holden vs. Hardy, 169 U. S. 366, 391.

The Court pointed out that:

‘ ‘ Colored persons are citizens of the United States

and have the right to purchase property and enjoy

and use the same without Laws discriminating

against them on account of color.” (Italics mine.)

Buchanan vs. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 78.

Undoubtedly, the Fourteenth Amendment and the stat

utes passed subsequent thereto, relate only to action by

the State and not to action by individuals. But State

action includes judicial as well as legislative and execu

tive action.

“ They have reference to actions of the political

body denominated a State, by whatever instruments

or in whatever modes that action may be taken. A

State acts by its legislative, its executive or its judi

cial authorities. It can act in no other way. The

constitutional provision, therefore, must mean that

no agency of the States, or of the officers or agents

by whom its powers are exerted, shall deny to any

person within its jurisdiction, the equal protection

of the laws. Whoever, by virtue of public position

under a state government; deprives another of prop

erty, life or liberty, without due process of law, or

7

denies or takes away the equal protection of the

laws, violates the constitutional inhibition; and as he

acts in the name for the State, and is clothed with the

State’s power, his act is that of the State.” (Italics

mine.)

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 34.

See also:

Scott vs. McNeal, 154 V. S. 34.

Chicago, Burlington ancl Quincy R. R. vs. Chi

cago, 166 U. S. 226, 233.

U. S. vs. Harris, 106 U. S. 629, 639.

If the State legislature is powerless to pass-a law re

straining occupancy of certain property by Negroes, then

the State judiciary is likewise powerless to permit what

the Constitution forbids any State department to do. Mr.

Justice W h it e said:

“ # * * how can it be said that the judicial depart

ment, the source and fountain of justice itself, has

yet the authority to render lawful, that which if done

under express legislative sanction would be violative

of the Constitution? If such power obtains, then the

judicial department of the government sitting to up

hold and enforce the Constitution is the only one pos

sessing a power to disregard it. If such authority

exists, then in consequence of their establishment,

to compel obedience to law and to enforce justice,

courts possess the right to inflict the very wrongs

which they were created to protect.”

Hove.y vs. Elliott, 167 U. 8. 409, 417.

In a covenant not to lease to Chinese persons, a case

very similar to the instant case, it was said:

“ It would be a very narrow construction of the

constitutional admendment in question and of the de

cisions based upon it, and a very restricted applica

tion of the broad principles upon which both the

amendment and the decisions proceed, to hold that,

8

while the State and municipal legislatures are for

bidden to discriminate against the Chinese, in their

legislation,, a citizen of the State may lawfully do so

by contract, which the courts may enforce. Such a

view is, I think, entirely inadmissible. And result

inhibited by the Constitution can no more be accom

plished by contract of individual citizens than by

legislation, and the Court should no more enforce

the one than the other. This would seem to be very

clear.”

Gandolfo vs. Hartman, 49 Fed. 181,182.

It is submitted that to lend judicial recognition to the

covenant in this case would violate the Constitutions of

the United States and of Maryland in their entirety, in

cluding the letter and spirit and the fundamental plan

thereof, whereby the legislative, executive and judicial

branches of the government, both State and Federal, were

made and intended to be co-ordinate and of co-equal dig

nity and power, each in its own sphere.

The decision in the case of Corrigan vs. Bulkley, 271

U. S. 323, does not preclude a decision'by this Court con

sonant with the argument heretofore advanced because

the argument that enforcement of the covenant consti

tuted State action in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, was not raised in the petition for appeal or by as

signment of error and hence was not properly before the

Court for decision. Therefore, any discussion of this

point was merely dictum. The case was “ dismissed”

for want of jurisdiction.

It might be added that the District of Columbia is not a

State and the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia

was not acting as a State agency, therefore, the Four

teenth Amendment was not applicable to the Corrigan

case.

9

QUESTION NO. II.

THE COVENANT IS CONTRARY TO PUBLIC POLICY AND

THEREFORE UNENFORCEABLE.

Housing has until recent years been a private problem.

During the past three years there has developed a public

conscience that accepts the obligation of attempting to

house the poor in conformity with a minimum standard

of decency, comfort and convenience. Proper housing

has become a City, State and National problem. The

Home Owners Loan Corporation, the Wagner-Ellenbo-

gen Housing Bill, the housing projects of the Public

Works Administration and the Resettlement Administra

tion, the Federal Housing Administration are all indica

tive of the trend of modern thought upon the question of

housing. In addition to adoption of the aforementioned

projects, the City of Baltimore has undertaken slum

clearance projects and pursuant thereto, razed what was

formerly known as the “ lung block” and erected upon

that site, a beautiful school. These undertakings illus

trate clearly that housing has become a public policy of

this State and Nation.

The Appellant Meade purchased a home compatible

to his means and station in life but after purchasing the

home he found himself in the analamous position of own

ing a home in which he cannot live, unless this Court re

verses the decision of the Circuit Court of Baltimore.

Carried to its logical conclusion, this means, under the

decision of the lower Court, that if white property owners

throughout the City of Baltimore unite in similar cove

nants, probably 90 per cent of the homes are close to oc

cupancy by Rev. Meade. Since it is a well-known fact

that housing conditions among the Negro populations

are the poorest in the City 145,000 Negroes could not hope

10

to improve their housing to any appreciable extent with

in the limits of Baltimore City.

“ It means for them living in one room or even

part of a room, the indecencies and the health men

aces of inadequate or non-existent sanitary conveni

ences, an environment that is depressing and degrad

ing, conducive to immorality, stifling to self-respect

and incentive to crime.

Health Department, Police Department, Fire De

partment, Juvenile Court, social agency records es

tablish that where housing accommodations are sub

standard these conditions are found:

Tuberculosis is most prevalent and most deadly.

Illegitimate children are most numerous.

Syphilis takes its heaviest toll.

Crime recruits the greatest number of its practi

tioners.

Delinquency among children reaches its highest

peak.

Infant mortality is highest.

The death rate for all ages is highest.

Residence fires and fatalities from fires are most-

numerous.

Relief rolls are heaviest.”

The Evening Sun, December 16, 1936.

The State of Maryland has a corrective agency for

each of the above-mentioned ills. It cannot be denied

that a cure for these ills is a public policy of Maryland

and conversely anything tending to increase these evils

is against public policy. Hence, any agreement between

citizens of this State which contributes either directly or

indirectly, towards a continuation of these ills is against

public policy and should not be enforced by a Court of

Equity. The matter affects the social welfare of a large

part, if not all, of the community.

11

“ * * * the Courts have frequently quoted and

often approved of the statement that public policy is

that principal of the law which holds that ‘ no one

can lawfully do that which has a tendency to be in

jurious to the public or against the public good; that

rule of law that declares that no one can lawfully do

that which tends to injure the public, or is detri

mental to the public good; the principles under which

freedom of contract or private dealing is restricted

by law for the good of the community.”

50 Corpus Juris, Sec. 62, p. 858.

Words and Phrases.

If it is illegal for the State of Maryland to pass a law

specifying in what localities Negroes shall live, then it is

at least against public policy for private citizens to com

bine to do that which the State is forbidden to do. It is

essentially a conspiracy to accomplish indirectly that

which is forbidden of accomplishment directly. Chief

Justice Chase said:

“ * * * there can be no doubt but that all con

federacies whatsoever wrongfully to prejudice a

third person, are highly criminal at common law; as

where divers persons confederate together by divers

means to impoverish a third person.”

State vs. Buchanan, 5 H. & J. 317, 366.

It has been held that a conspiracy between two or more

persons to prevent Negro citizens from exercising the

right to lease and cultivate land, because they are Ne

groes, is a conspiracy to deprive them of a right secured

to them by the Constitution and laws of the United States.

U. S. vs. Morris, 125 Fed. 322.

Shelter is, in America, a necessity of life and any com

bination designed to deprive a person of it should be de

12

prived of the protection of a Court of Equity for “ He

who comes into Equity must do so with clean hands.”

Courts of Equity frequently enforce restrictive cove

nants on the use of real property. In such cases, how

ever, the objection is to the use itself. But here the ob

jection is not to the use but to the occupancy of the prop

erty. The restriction is therefore against the person,

and easily distinguished from the cases involving party

walls, saloons, amusement places, and other offensive

nuisances.

QUESTION NO. III.

THIS IS A PERSONAL COVENANT WHICH DOES NOT RUN

WITH THE LAND AND IS NOT BINDING UPON

THE APPELLANT MEADE.

At the time this covenant was executed, all of the signa

tories thereto owned their respective properties. No

one had any interest whatsoever in the property of any

other and no intention to convey or acquire any such in

terest. They entered into an agreement among them

selves, that they would not dispose of their property to

Negroes and though they stipulated that the covenant

was to be binding upon their heirs and assigns and to run

with the land, it, in fact, is incapable of binding any but

the original parties because there has never been any

privity of estate between the Tighes and those seeking to

enforce the covenant. The law upon this point is sum

marized as follows:

“ It is a general rule that a covenant which may

run with the land can do so only when there is a sub

sisting privity of estate between the covenantor and

the covenantee, that is, when the land itself, or some

estate, or interest therein, even though less than the

entire title, to which the covenant may attach as its

13

vehicle of conveyance is transferred; and if there is

no privity of estate between the contracting parties,

the assignee will not be bound by, nor have the benefit

of any covenants between the contracting parties not

withstanding they relate to the land which he takes

by purchase or assignment from one of the parties

to the contract.”

15 C. J. 1242, Sec. 55; also p. 1260, Sec. 85.

Frank on Real Property, p. 100.

Poe, Practice and Pleading (5th Ed.), Vol. 1,

Sec. 330, p. 282.

Summers vs. Beater, 90 Md. 474, 479, 480.

Bartell vs. Senger, 160 Md. 685.

As stated in Best on “ Restrictions and Restrictive

Covenants,” at p. 3:

“ Inasmuch as the covenant must be one that runs

with the land, or with an interest or estate in the

land, there must be land intended to be benefited by

the covenant, and there must be a conveyance or

lease of said land, or an assignment of the leasehold

interest therein, by one of the parties to the covenant,

though not necessarily by the same instrument but

in the same transaction, transferring the said inter

est or estate in the land with the covenant adhering

to it. In other words, there must be privity of estate

between the covenantor and covenantee, such privity

resulting from the said conveyance, lease or assign

ment. ’ ’

Citing:

Glen vs. Canby, 24 Md. 127.

The authorities uniformly hold that there must be priv

ity of estate in order for the covenant to run with the

land. The question of what constitutes privity of estate

has been debated for hundreds of years and there seems

to be no unanimity of opinion. An examination of the

14

better text-books and the cases from which their authors

draw their conclusions discloses a well-established opin

ion that privity of estate can be created only where there

is some actual transfer of a property interest at the time

of the creation of the covenant.

Sims on Covenants, at page 197, says:

“ In modern times it has become settled in Eng

land, as we shall see, that not even the grant of an

easement is sufficient to allow an accompanying cove

nant to run.

“ The American law is generally settled that the

covenant without some sort of a grant is merely a

personal obligation.”

It is submitted that there was no conveyance in this

case to which the covenant could attach in order to run

with the land, and consequently there was no privity of

estate between the Tighes and the other signatories to

this agreement. Since nothing passed and no possession

attended the conveyance, the covenant does not run.

“ With a very few exceptions, the uniform current

of authorities from the time of Webb vs. Russell, 37

T. R. 393, to the present day, requires a privity of es

tate to give one man a right to sue another, upon a

covenant where there is no privity of contract be

tween them; consequently, that, where one who

makes a covenant with another in respect to land

neither parts with, nor receives any title or interest

in the land at the time with and as a part of making

the covenant, it is at best a mere personal one, which

neither binds his assignee, nor inures to the benefit

of the assignee of the covenantee, so as to enable the

latter to maintain an action in his own name for a

breach thereof.” (Italics mine.)

Washburn on Real Property, 4th Ed., Vol. 2,

p. 285.

15

See also:

Tiffany on Beal Property, (3rd Ed.), Sec. 391,

p. 1407.

7 R. C. L., p. 1103.

66 L. R. A., p. 682, note.

Sharp vs. Cheatham, 88 Mo. 498.

Poe, in his Practice and Pleading, 5th Edition, Vol. 1,

p. 282, says:

“ Whether a stranger to the land can enter into a

covenant respecting it which will pass to the as

signees of the land so as to enable them to maintain

an action upon it is very doubtful. Sir Edward Sug-

den maintains that there is no direct authority for

the proposition.”

In arguing that there must be privity of estate in order

for this covenant to run, I am not overlooking the deci

sion of this Court in Clem vs. Valentine, 155 Md. 19, 26,

where it was held that it is not necessary In Equity “ in

order to sustain the action that there should be privity

of estate or contract.” But in Bartell vs. Senger, 160

Md. 685, p. 691, after quoting from Clem vs. Valentine,

supra, the Court remarked, “ nor does it certainly appear

that there is any privity either of estate or contract be

tween the parties to this proceeding,” and held upon this

and other facts “ the appellants have no standing in a

Court of Equity to enforce the restrictions.”

If, however, this Court holds that the covenant in this

case should be binding upon the Appellant Meade irre

spective of privity of estate, there are other grave and

equitable reasons why it should not be enforced in this

case. Mrs. Becker testified that she thought a majority

of signers controlled, and had she known that the entire

area (24 blocks) would not have been restricted she would

16

never have signed the covenant. At the time she signed,

she thought every other owner was going to sign the cove

nant. Mrs. Dennistone testified to substantially the

same thing, except that she would have signed the cove

nant irrespective of whether the other signed, in the

hope that they would sign later. These statements show

clearly that they did not understand the nature and ex

tent of these covenants.

The present situation surrounding these properties is

such that the original purpose can no longer be effected.

Eleven of the 29 properties within the block, including

those next door to the Appellees, are not subject to this

covenant, and Negroes could occupy them tomorrow.

The surrounding streets are largely, if not predominant

ly, occupied by Negroes. When faced with these circum

stances,

‘ ‘ Courts of Equity have uniformly refused to inter

fere for the purpose of enforcing observance of a

restrictive covenant where the evidence shows that

a state of things has arisen in the march of events

which the parties to the agreement did not contem

plate when it was made, and which would render its

enforcement inequitable and unjust, resulting in in

jury to the defendant without permanent benefit to

the complainant.”

Boston Bapt. Social Union vs. Boston Univer

sity, 183 Mass. 202.

Jackson vs. Stevenson, 156 Mass. 426.

Amerman vs. Deane, 132 N. Y. 355.

The Appellant Meade will be irreparably harmed in

the premises should this covenant be enforced. He can

not live in the property and yet he must continue to buy

for if this Court enforces this covenant, Rev. Meade is not

relieved from his obligation to purchase the property.

17

He must hope and depend upon rent to help him finance

this property and he must in turn, rent elsewhere unless

he is one of the few people able to purchase two homes

at the same time. On the other hand, the Appellees will

not be materially benefited because other Negroes may

and can move next door to them. Already, one Negro

owns and occupies one property in the block.

In still another respect, this covenant is of little prac

tical effect. None of these people who signed the cove

nant owned the land upon which his home was built. If

for any reason the property should become vested in the

reversioner, that particular piece of property would be

freed of this covenant and the property could then be

sold to Negroes for occupancy.

In McDowell vs. Biddison, where the facts showed that

to close an old road would do no harm to the complain

ant, but to keep it open would cause great damage and

loss to the defendant, J. Burke held:

“ But if it be conceded that the agreement was

made and established, the case is not one in which

the injunction could have been continued. No real

harm has been done the plaintiff by the closing of

the old road, and very great harm would be done to

the defendant by granting the relief prayed for. It

is said in McCutcheon’s Heirs vs. Rawleigh, 76 8. W.

51, that it is not every plain and certain contract that

will be specifically enforced, whatever may be the

legal rights of the parties in an action of damages

for its breach.” * * * “ If to enforce specifically an

agreement would do one party great injury and the

other but comparatively little good, so that the result

would be,' more spiteful than just, the Chancellor will

not require its execution.”

120 Md. 118, p. 127.

18

If we weigh the equities—the comparative burdens and

benefits—we see that the Court is asked to deprive one

man of the right to occupy a house he owns to satisfy

the prejudice of two women who live some distance from

the house in question. It is now impossible for them to

secure what they originally bargained for, i. e., an ex

clusively white neighborhood.

Respectfully submitted,

W. A. C. HITCHES, JR.,

Solicitor for Appellant.

19

INDEX TO RECORD.

PAGE.

Agreement as to Record................. ...................... ....... 3

Docket Entries .......... .......................................... ......... 3,4

Statement of Case ........ ......................................... ....... 4

Bill of Complaint ....................... ..... ............................ 4

Answer of Frank Berman.......................................... 7

Answer of Edward Meade............. 8

Covenant .................................... 11

Testimony of Mary J. Becker..................... ................ 16

Testimony of M. Estelle Dennistone.... .......... ........... 20

Final Decree ............................................. 22

Order for Appeal ........................................................ 23

Certification by Clerk .....................„.......................... . 24

E dward Meade

vs.

I k T he

Court of Appeals

Of Maryland.

>

M. E stelle D ennistone and

Mary J. B ecker.

October T erm, 1937.

General D ocket No. 26.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE.

J. S. T. WATERS,

WILLIAM L. MARBURY, JR.,

ROBERT R. PORTMESS,

Attorneys for Appellee.

E dward Meade

In The

vs.

M. E stelle D ennistone and

Mary J. B ecker.

Court of Appeals

Of Maryland.

October T erm, 1937.

J General D ocket No. 26.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

This is an appeal from an Order of the Circuit Court

of Baltimore City (S olter, J.) enjoining the appellant,

Edward Meade, a negro, from using or occupying the

premises known as 2227 Barclay street in the City of

Baltimore, and further enjoining and restraining Frank

Berman, his heirs, etc., from permitting the appellant

to use or occupy the premises aforesaid. The injunction

was issued to enforce a neighborhood restrictive agree

ment entered into by the appellees and the predecessors

in title of the appellant. The questions involved in the

appeal depend upon the validity of this agreement, and

its enforceability in equity.

THE QUESTIONS IN CONTROVERSY.

I.

Is the Restrictive Agreement Valid?

The trial court answered this question in the affirma

tive by issuing an injunction. The appellee contends that

the ruling of the trial court is correct for the following

reasons:

2

A. The agreement is not contrary to public policy.

B. The agreement does not place an unreasonable

restraint upon alienation.

C. The agreement is not repugnant to the grant.

D. Enforcement of the agreement does not deprive

the appellant of property without due process of law.

II.

Has Equity Jurisdiction to Enforce the Agreement?

The trial court answered this question in the affirma

tive by issuing the injunction. The appellant contends

this is correct for the following reasons:

A. Equity has jurisdiction to enforce a restrictive

covenant, although it does not run with the land.

B. There need be no privity of estate and contract be

tween the covenantor and the covenantees.

C. There is no adequate remedy at law.

III.

Has the Covenant Failed In Its Purpose?

The trial court answered this question in the negative.

The appellant contends that this ruling is correct for the

following reasons:

A. The record shows no material changes in condi

tions since the execution of the agreement.

B. The record does not show that enforcement of the

agreement will depreciate the value of the property.

3

STATEMENT OF FACTS.

Sometime prior to November 14, 1927 a colored family

moved into the 2300 block of Guilford avenue in the City

of Baltimore. Shortly thereafter it was rumored that a

colored family was to occupy a vacant house nearby on

Barclay street. A meeting was then called of the prop

erty owners in the area of twenty-four square blocks,

bounded on the north and south by Twenty-fifth street

and North avenue, and on the east and west by Barclay

street and Charles street. Following this meeting an

agreement was signed by a number of the property

owners of houses on Barclay street (R. 15).

The agreement is dated the 14th day of November, 1927,

and was recorded among the Land Records of Baltimore

City on January 27, 1928. It was signed by the owners

of eighteen properties in the 2200 block of Barclay street

and provided that the parties thereto—“ jointly and sev

erally for themselves and each of themselves, their and

each of their personal representatives successors and as

signs grant warrant covenant promise and agree amongst

themselves and each and all of them with all and each one

of the others their heirs and each of their heirs personal

representatives successors and assigns that they and each

of them their heirs and each of their heirs personal repre

sentatives successors and assigns shall and will have hold

stand seized and possessed of the said respective prop

erties interest and estate subject to the following restric

tions limitations conditions covenants agreements stipu

lations and provisions to wit THAT neither the said re

spective properties nor any of them nor any part of them

or any of them shall be at any time occupied or used by

any negro or negroes or person or persons either in

whole or in part of negro or African descent except only

4

that negro or persons of negro or African descent either

in whole or in part may be employed as servants by any

of the owners or occupants of said respective properties

and as and whilst so employed may reside on the prem

ises occupied by their respective employers nor shall any

sale lease disposition or transfer thereof be made or oper

ate otherwise than subject to the aforesaid restrictions

as to and upon use or occupancy that neither the said

parties nor any of them their or any of their heirs per

sonal representatives successors and assigns will do or

permit to be done any of the matters or things above-

mentioned excepting only as aforesaid” (R. 12-13). It

further provided that the restrictions set forth should

run with the land and bind the properties and any suc

cessors of all the parties to the agreement and should

inure to the benefit of any successor at any time owning

or occupying any of said properties.

The appellees, M. Estelle Dennistone and Mary J.

Becker, who were respectively the owners of Nos. 2221

and 2234 Barclay street, signed the agreement as did

Annie M. Tighe, Mary Y. Tighe, Francis L. Tighe and

Anna R. G-ugerty, who were then the owners of 2227 Bar

clay street. Thereafter, on May 27, 1935, the aforesaid

owners of 2227 Barclay street conveyed the property to

Florus Barry, who on the same day conveyed it to Mary

V. Tighe and Anna R. Gugerty, who on November 4, 1936

(Mary V. Tighe) conveyed the property to Frank Ber

man (R. 14). On October 22, 1936 Frank Berman,

through his agent, contracted to sell 2227 Barclay street

to the appellant, Edward Meade, a negro, for the sum of

$1,100, of which $150 was paid in cash, the balance to be

paid on conditional contract of sale. Thereafter, and

prior to the 24th day of November, 1936, Edward Meade

5

entered into possession of the premises and with his

family occupied the same as a residence (B . 10).

On November 24, 1936 the appellees filed their bill of

complaint against the appellant and Frank Berman re

citing the aforesaid facts and praying that the appellant

be enjoined and restrained from using or occupying No.

2227 Barclay street, and that the defendant, Frank Ber

man, be enjoined and restrained from procuring and au

thorizing or permitting any negro or negroes or person

or persons either in whole or in part of negro or African

descent to use or occupy the property contrary to the

provisions of the agreement set forth in the bill of com

plaint. On the same date Judge F e a u k signed an order

requiring the defendant to show cause on or before De

cember 1, 1936, why the injunction should not issue as

prayed (B. 6).

The defendant, Frank Berman, filed his answer in

which he asserted that the agreement was null and void

for the reason that it had been executed upon the under

standing that the owners of all the properties in the block

would sign, whereas the owners of eleven of such prop

erties never did sign the agreement; and for the further

reason that the agreement had failed to accomplish its

purpose. Berman also alleged that by reason of the occu

pation of nearby properties by negroes, the value of the

property in question would be greatly increased by recog

nition of the invalidity of the agreement.

Thereafter, the appellant, Edward Meade, answered

the bill alleging that the agreement was invalid and unen

forceable because: (a) it was a personal covenant and did

not run with the land; (b) it was contrary to public pol

icy ; (c) there was no privity of estate or contract between

the covenantor and the covenantee; (d) it was an unrea

6

sonable restraint placed upon the free alienation of the

property in question; (e) the reason for its execution no

longer obtained; (f) enforcement of the agreement would

deprive the appellant of his property without due process

of law. To the answer was appended a demurrer on gen

eral grounds, and on the ground that the appellee had

an adequate remedy at law.

The case came on for hearing and testimony was taken.

It was conclusively shown by the testimony of the appel

lees that they had executed the agreement with full knowl

edge that other owners either failed or refused to sign

(R. 19). No testimony to the contrary was produced on

behalf of the appellant or the defendant, Frank Berman.

The testimony further showed that, at the time the

agreement was entered into, Twenty-third street was in

habited by colored people and there were two colored

churches on that street, an alley known as Twenty-second

and a half street was occupied by colored people, and one

colored family had moved into the 2300 block of Guilford

avenue. It was shown that with the exception of the

Guilford avenue block the streets in question had been

colored for many years (R. 15, 20). The testimony fur

ther showed that, at the time of the trial, Brentwood ave

nue, a narrow street running from North avenue to

Twenty-fifth street between Barclay and Guilford ave

nue, was inhabited by colored people and that a part of

Twenty-fourth street was also inhabited by colored peo

ple, but the record failed to show whether this condition

existed at the time when the agreement was entered into.

The testimony also showed that since the signing and

recording of the agreement there had been no occupancy

of Barclay street by colored people with the single excep

7

tion of 2238 Barclay street, which stands at the southwest

corner of Barclay and Twenty-third street. This prop

erty was a dressmaking shop on the first floor catering

exclusively to white trade, which was entered from Bar

clay street; it had an apartment on the upper floor which

was entered from Twenty-third street and was occupied

by a colored man and his wife who used the Twenty-third

street entrance exclusively. This property had never

been covered by the agreement, and the use made thereof

was not objectionable to the white residents on Barclay

street (R. 15).

The appellees offered in evidence an agreement duly

executed and recorded on December 14, 1936 signed by a

number of property owners in the 2200 block of Barclay

street who were not signatories to the original agree

ment. This agreement was in substance identical with

the agreement signed by the complainants and the prede

cessor in title of the appellant and the defendant Berman.

It was shown that the agreement had been signed and

originally recorded on July 21, 1936, but that by reason

of defective acknowledgment it had been necessary to

record the agreement again subsequent to the institution

of the present suit. The trial court ruled that the agree

ment could not be admitted into evidence, and an excep

tion was duly noted (R. 21).

On January 18, 1937 the trial court entered a decree

in accordance with the prayer of the bill. The appellant,

Edward Meade, duly appealed, but the defendant Frank

Berman took no appeal from the order.

8

ARGUMENT

The undisputed facts in the case and the pleadings

themselves somewhat narrow the issues on this appeal.

There is no dispute as to the signing of the agreement,

as to its recordation, as to appellee’s title or as to the fact

that the appellant derived his right of possession directly

from a signatory to the agreement. The only questions

presented are as to the validity of the agreement, and its

enforceability by a court of equity.

I.

T H E A G R E E M E N T IS V A L ID .

A . The Agreement Is Not Contrary to Public Policy.

It is hardly necessary to argue that an agreement re

stricting the occupancy of land against negroes or per

sons of African descent is consistent with the public pol

icy of this State. That policy was authoritatively ex

pressed by this Court in the case of State v. Gurry, 121

Md. 534, where, an ordinance of Baltimore City requir

ing the segregation of the negro and white races was

considered and the general policy of segregation ap

proved although the ordinance was held invalid on other

grounds. A new ordinance obviating the defects pointed

out in that decision was enacted and went unchallenged

until a similar ordinance of the City of Louisville was

held invalid in the case of Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S.

60, but we do not perceive how that decision can affect the

public policy of the State of Maryland, nor indeed can

Buchanan v. Warley be taken to indicate disapproval of

the policy, the decision turning on the power of the City

to pass the ordinance.

9

In any event, cases arising in other jurisdictions have

unanimously held that a covenant against use or occu

pancy by negroes is valid and enforceable. Some cases

draw a distinction between covenants against occupancy

by negroes and covenants against sale to negroes, holding

the latter invalid as contrary to public policy. Other

cases reject the distinction and hold such contracts

equally valid, but no case has been found holding that a

covenant against occupancy is invalid as against public

policy or for any other reason.

A summary of the decisions follows:

(1) Cases holding covenants againt sale to negroes to

be valid:

Corrigan v. Buckley, 299 F. 899 (Ct. of App.

D. C. 1924) appeal dismissed, 271 U. S.

323

Torrey v. Wolfes, 6 F. (2d) 702 (Ct. of App.

D. C. 1925)

Russell v. Wallace, 30 F. (2d) 981 (Ct. of App.

D. C. 1929) certiorari denied, 279 U. S.

871

Cornish v. O’Donoghue, 30 F. (2d) 983 (Ct. of

App. D. C. 1929) certiorari denied, 279

IT. S. 871

Koehler v. Rowland, 275 Mo. 573, 205 S. W.

217, 9 A. L. E. 107 (1918)

Queensborough Land Co. v. Caseaux, 136

La. 724, 67 So. 641, L. E. A. 1916 B, 1201

(1915)

(2) Cases holding covenants against sale to negroes to

be void:

Title Guarantee & Tr. Co. v. Garrott, 42 Cal.

App. 152, 183 P. 470, (1919)

, Los Angeles Inv. Co. v. Gary, 181 Cal. 680,

186 P. 596, 9 A. L. E. 115, (1919)

10

Janss Inv. Go. v. Walden, 196 Cal. 753, 239 P.

34, (1925)

Wayt v. Patee, 205 Cal. 46, 269 P. 660 (1928)

Mandlebaum v. McDonnell, 29 Mich. 78, 18

Am. Rep. 61, (1874)

Porter v. Barrett, 233 Mich. 373, 206 N. W.

532, 42 A. L. R. 1267 (1925)

White v. White, 108 W. Ya. 128, 150 S. E. 531,

66 A. L. R. 518 (1929)

(3) Cases, such as the one at bar, involving the validity

of a covenant against occupancy by, as distin

guished from sale to negroes. Every case decided

on the question has held such a covenant to be

valid and it has been so held even by jurisdictions

which hold covenants against the sale to negroes

to be void.

Los Angeles Inv. Co. v. Gary, supra

White vs. White, supra

Parmalee v. Morris, 218 Mich. 625, 188 N. W.

330, 38 A. L. R. 1180 (1922)

Porter v. Barrett, supra

Janss Inv. Go. v. Walden, supra

Wayt v. Patee, supra

Schulte v. Starks, 238 Mich. 102, 213 N. W. 102,

(1927)

Covenants against occupancy by negroes are not con

trary to public policy:

In Parmalee v. Morris, supra, the deed to the property

in question provided that “ No building shall be built

within 20 feet of the front line of the lot. Said lot shall

not be occupied by a colored person, nor for the purpose

of doing a liquor business thereon.” The defendants,

colored people, contracted to buy the property and the

plaintiffs, owners of similarly restricted properties in

11

the same subdivision, sought to have the defendants en

joined from violating the restriction. One of the

grounds for the defendants’ contention that the covenant

was void was that it was contrary to public policy.

In upholding the validity of the covenant the court

said (218 Mich. 628):

“ Is the restriction contrary to public policy?

“ It has been said that certain acts are contrary

to public policy so that the law will refuse to recog

nize them when they have a mischievous tendency

so as to be injurious to the interests of the state.

This brings up the question as to what interests of

the state are likely to be injured if an owner of prop

erty, for reasons which are satisfactory to himself,

refuses to sell himself, or permit his assignors to

sell, to certain persons who may be distasteful to

him as neighbors. Are there any interests of the

state which will be promoted or advanced compelling

the creation of such a condition in the community!

The law is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or

to abolish distinctions which some citizens do draw

on account of racial differences in relation to their

matter of purely private concern. For the law to at

tempt to abolish these distinctions in the private

dealings between individuals would only serve to

accentuate the difficulties which the situation pre

sents.

“ One of the purposes of the restriction in the in

stant case was apparently to preserve the subdivi

sion as a district unoccupied by negroes. Whether

this action on the part of the owner was taken to

make the neighborhood more desirable in his estima

tion, or to promote the better welfare of himself and

his grantees, is a consideration which I do not be

lieve enters into a decision of the case. So far as

12

I am able to discover, there is no policy of the state

which this action contravenes. Were defendants’

claim of rights based upon any action taken by the

authority of the state, an entirely different ques

tion would be presented.”

In Corrigan v. Buckley, 299 F. 899, 902, (Ct. App. D.

C., 1924), appeal dismissed 271 U. S. 323, the covenant

in question forbade the sale or leasing to, or occupancy

by, negroes. It was contended that the covenant vio

lated the 14th Amendment of the Constitution and was

contrary to public policy. After holding that the cove

nant did not violate the 14th Amendment the court said

(p. 902):

“ It follows that the segregation of the races,

whether by statute or private agreement, where the

method adopted does not amount to the denial of

fundamental constitutional rights, cannot be held to

be against public policy. Nor can the social equal

ity of the races be attained, either by legislation or

by the forcible assertion of assumed rights. * * *”

Nor have any of the cases involving the validity of

covenants against occupancy by negroes, cited supra,

held such covenants to be contrary to public policy.

B. The Agreement Does Not Place an Unreasonable

Restraint Upon Alienation.

The cases cited in the preceding section of this brief

are unanimous in holding that a covenant against occu

pancy by negroes is not a restraint upon alienation, but

is merely a restraint against the use of real property.

Some cases hold that a covenant against sale to negroes

is invalid as being an unreasonable restraint on aliena

tion, although there are many decisions to the contrary.

13

Not a single case, however, holds that a covenant merely

forbidding occupancy by negroes is invalid as a restraint

on alienation. See especially:

Los Angeles Inv. Co. v. Gary, supra

White v. White, supra

Parmalee v. Morris, supra

Porter v. Barrett, supra

Janss Inv. Co. v. Walden, supra

Wayt v. Patee, supra.

Schulte v. Starks, supra.

C . The Covenant Forbidding Occupancy by Negroes Is Not Void

As Being Repugnant to the Grant.

Although all courts agree that conditions or restric

tions completely destroying the right to alienate prop

erty, even for a limited time, are void, as inconsistent

with complete ownership, and many courts hold even

partial restraints on alienation void as repugnant to the

interest created, the question of the restriction of the

right to alienate, either complete or partial, is not in

volved in this case. The covenant in question is not a

restriction on the right to alienate but on the use of the

property, and such covenants against occupancy by ne

groes have been held to be valid restraints on the use of

the property in every case in which their validity has

been questioned and in no instance to be repugnant to

the grant:

Los Angeles Inv. Co. v. Gary, supra

Wayt v. Patee, supra

White v. White, supra

Parmalee v. Morris, supra

Schulte v. Starks, supra.

14

D . Enforcement of the Agreement Does Not Deprive the Appellant

of His Property Without Due Process of Law.

The question of the validity of restrictive agreements

of this type under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States was closed by the decision

of the Supreme Court in Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U. S.

323, 331 (1926) where the Court dismissed as without

merit an appeal from a decision of the Court of Appeals

of the District of Columbia affirming an injunction ■ en

forcing an agreement among private individuals forbid

ding the sale of the property to negroes. It will be noted

that this injunction upheld an agreement not to sell,

which is far more drastic than an agreement against oc

cupancy. The ground of the decision was that enforce

ment of a covenant against occupancy or sale of property

is not a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, but

merely tolerates discrimination by individuals and in no

wise sanctions such discrimination by the State either

through its legislative or judicial departments.

As it is elementary that the first,Section of the Four

teenth Amendment has exclusive reference to the inva

sion of individual rights by the States and has no appli

cation to the invasion of individual rights by individuals,

it follows that the Fourteenth Amendment is not applic

able.

The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3

Corrigan v. Buckley, 299 F. 899, 901 (Ct. of

App. D. C. 1924), 271 U. S. 323, 330, 331

(1926)

Los Angeles Inv. Co. v. Gary, supra

Parmalee v. Morris, supra.

15

II.

EQUITY HAS JURISDICTION TO ENFORCE

THE AGREEMENT.

A , A Restrictive Covenant May Be Enforced in Equity Against an

Assignee of a Covenantor, Although It Does Not

Run With the Land.

In order to be enforced in equity a restrictive cove

nant as to the use of land need not be one “ running with

the land” in the technical sense of the term:

“ Even in jurisdictions where, as in England, the

burden of a covenant does not run with the land, an

agreement as to the use of land may, under certain

circumstances, affect a subsequent purchaser of the

land who takes with notice of the agreement. As

stated in the leading case on the subject, ‘ the ques

tion is not whether the covenant runs with the land,

but whether a party shall be permitted to use the

land in a manner inconsistent with the contract en

tered into by his vendor, and with notice of which he

purchased’. # * Such an agreement may occur in

connection with a conveyance of land, restricting the

grantor, * * * or restricting the grantee. * * # Or it

may be independent of any conveyance of land, be

ing merely an agreement between adjoining owners

as regards the use of their land.”

2 Tiffany on Real Property (2nd ed.) 1425,

1426 Sec. 394

In Pomeroy’s Equity Jurisprudence (4th ed.) Sects.

688 and 689, the rule is stated as follows:

“ A purchaser with notice of a prior contract to

sell or to lease takes subject to such contract, and is

bound in the same manner as his vendor to carry it

into execution. # # # On the same principle, if the

owner of land enters into a covenant concerning the

land, concerning its uses, subjecting it to easements

or personal servitudes and the like, and the land is

16

afterwards conveyed or sold to one who has notice of

the covenant, the grantee or purchaser will take the

premises bound by the covenant, and will be com

pelled in equity either to specifically execute it, or

will be restrained from violating it ; and it makes no

difference whatever, with respect to this liability in

equity, whether the covenant is or is not one which

in law ‘ runs with the land ’, ’ ’

In Clem v. Valentine, 155 Md. 19, 26, the court quoted

the following from Columbia College v. Lynch, 70 N. Y.

440, 449:

“ Whether it was a covenant running with the

land, or a collateral covenant, or a covenant in gross,

or whether an action at law could be sustained upon

it, is not material as affecting the jurisdiction of a

court of Equity, or the right of the owners of the

dominant tenement to relief upon a disturbance of

the easements.”

After quoting this language, the Court in Clem v. Val

entine, said:

“ It seems to be well settled by the weight of au

thority that any grantee of the land to which such

a right is appurtenant acquires by his grant a right

to have the servitude, or easement, or right of

amenity, protected in equity, notwithstanding that

his right may not rest on the covenant, which simply

runs with the title to his land, and notwithstanding

that it may also be true that he may not be able to

maintain an action at law for the vindication of his

right. ’ ’

In Schmidt v. Hersey, 154 Md. 302, 306, the Court said

that the “ right is one enforced ‘ by virtue of the equit

able doctrine applicable, and does not depend upon the

existence of a covenant running with the land, or

17

upon the existence of any right to relief under the com

mon law. ’ ’ ’

In Newbold v. Peabody Heights Co., 70 Md. 493, 500,

the court said:

“ It may be very true that the covenant is not of

a character to run with the land, in the strict legal

technical sense of those terms; but if it be of a char

acter to create a right and an equity in favor of the

vendor or lessor, and those claiming in his right,

as against those holding and occupying the land, a

Court of Equity will assume jurisdiction and admin

ister relief. This is a well settled principle. * * *”

In order for a covenant, restricting the use of land, to

be enforceable in equity against a subsequent holder of

the land, it must appear that the intention of the cove

nanting parties was that the restriction was to bind not

only the promisor, but subsequent owners of the land as

well.

In Wood v. Stehrer, 119 Md. 143, 149, Chief Judge

Boyd, in speaking of whether a certain restrictive cove

nant was binding on the heirs and assigns of the cove

nantors, said:

“ * * # if it is intended to bind heirs and assigns

by such restrictions, it must be so stated, or at least

there must be enough in the instrument to show that

such was the intention. ’ ’

And, because the covenant involved did not refer to the

heirs and assigns of the covenantors, or provide that

they should “ use or hold the remainder of the property

subject to the same restrictions imposed on the lot con

veyed” , it was held to be a mere personal agreement of

the grantors which was not enforceable against other

proprietors.

18

In Baft ell v. Senger, 160 Md. 685, 690, the Court said

that “ It is apparent,” that in proceedings in equity in

volving restrictions or restrictive covenants, “ all techni

cal considerations, whatever may be their nature, are sub

ordinate to the intention of the parties” to the covenant.

The presumption is that the parties to the covenant in

tended that the restriction was to bind all subsequent

holders of the land and not merely the promisor.

“ What the intention was in this regard is a ques

tion of construction, but since it is ordinarily imma

terial to the promisee who may make any particular

use of the property, the presumption would seem to

be, in the absence of a clear showing to the contrary,

that such a use by any person whomsoever is intend

ed, and an intention to this effect would appear to be

clearly indicated by the fact that the agreement in

terms binds the promisor’s assigns, or that the

agreement is an impersonal form, that the land shall

not be used in a particular way.”

2 Tiffany on Beal Property (2nd ed.) p. 1438,

Sect. 397.

There can be little doubt, upon examining the language

of the agreement between the covenanting parties,

that their intention was that the restriction against oc

cupancy of any of their properties by negroes was to ap

ply to subsequent holders of their properties as well as

to themselves. The language of the instrument is abso

lutely unequivocal to that effect, providing that “ they

and each of them their heirs and each of their heir’s per

sonal representatives successors and assigns shall and

will have hold stand seized and possessed of the said re

spective properties interest and estate subject to the fol

lowing restrictions limitations conditions covenants

agreements stipulations and provisions to wit, That “ etc.

19

After reciting the restrictions the agreement further

provides “ that all and singular the restrictions limita

tions conditions covenants agreements stipulations pro

visions matters and things whatsoever herein contained

or mentioned shall run with and bind the land and each

and all of the above mentioned properties and premises

and every part thereof and the heirs personal representa

tives successors or assigns of each and all of the parties

hereto and shall be kept and performed by and inure to

the benefit of and be enforceable by all and every per

son and persons body and bodies politic or corporate at

any time owning or occupying said land. * * * ” It would

be difficult to imagine a more specific statement by the

covenanting parties that they intended all subsequent

holders of the land, as well as themselves, to be bound

by the covenant and the restriction therein contained.

In order for a covenant, restricting the use of land,

to be enforceable in equity against a subsequent pur

chaser of the land, it must also appear that the subse

quent purchaser took with notice of the restriction—

“ * * * a restrictive agreement is enforced in equity

against a subsequent purchaser only when he takes

with notice thereof. Such notice may be either ac

tual or constructive, and the purchaser is, in accord

ance with the general rule as to notice, charged with

notice of anything showing or imposing such a re

striction which may be contained in a conveyance in

the chain of the title under which he claims. * * *”

2 Tiffany on Real Property (2nd ed.) p. 1439,

Sect. 398.

“ The notice may be actual, as where a convey

ance was made ‘ subject to the restrictions and con

ditions in said deed recited’, referring to an earlier

deed. Ringgold vs. Denhardt, 136 Md. 136, 140. Or,

20

it may be constructive. Thus, the constructive no

tice furnished by the record of an instrument con

taining the restrictions properly recorded among the

land records is sufficient to satisfy the rule requir

ing notice of the restrictions.”

Best on Restrictions and Restrictive Cove

nants, p. 39.

In Lowes v. Carter, 124 Md. 678, the question was

whether the recording of a 'certain restrictive covenant

gave sufficient notice to a purchaser of land subject there

to to warrant the enforcement of the covenant against

him in equity.

The Court held that actual notice by the purchaser of

the existence of the restrictive covenant was not neces

sary to enforce its provisions against him in equity but

that the recording of the instrument, giving the pur

chaser constructive notice thereby, was sufficient.

In the present case, therefore, the appellant, the sub

sequent purchaser of No. 2227 Barclay Street, one of the

lots bound by the covenant against occupancy by negroes,

had sufficient notice of the existence and provisions of

the covenant to warrant his being bound thereby in a

court of equity. The instrument, embodying the cove

nant in question, was recorded among the land records

of Baltimore City in Liber S. C. L. 4841, folio 354, on

January 27, 1928, some time prior to the appellant’s en

tering into the contract to purchase No. 2227 Barclay

street. Being on record at the time of contracting to

purchase said lot, the appellant cannot contend that he

had no notice of the covenant’s existence as the prior re

cording of the covenant served to notify him construc

tively thereof.

21

B. A Restrictive Covenant Is Enforceable in Equity, Although There

Was No Privity of Contract and Estate Between the

Parties Thereto.

Although it may be true that, in order for a covenant

to “ run with the land” in the technical sense of the term,

so as to sustain an action at law, there must be privity

of both estate and contract between the covenantors and

covenantees, such privity is not necessary for the enforce

ment of a restrictive covenant in equity and hence the

presence or absence of such privity in this case is entirely

academic.

In Clem v. Valentine, 155 Md. 19, 26, the court, after

holding that a covenant need not be one running with

the land, in the legal sense, in order to be enforceable in

equity, said:

“ Nor is it necessary, in order to sustain the action,

that there should be privity of estate or contract, but

there must be found somewhere the clear intent to

establish the restriction for the benefit of the party

attempting to restrain its infringement.”

Furthermore, the necessity for privity of estate and

contract in order for a covenant to run with the land at

law is a purely technical requirement and need not neces

sarily be present for the enforcement of a restrictive

covenant in equity:

“ . . . it is apparent that in such a proceeding as

this all technical considerations, whatever may be

their nature, are subordinate to the intention of the

parties. ’ ’

Bartell v. Senger, 160 Md. 685, 690.

Covenants similar to the one in question have been fre

quently enforced in equity even though the parties there

to were adjoining owners and there was no privity of es

tate between them.

22

In 2 Tiffany on Real Property (2nd ed.) p. 1426, Sect.

394, discussing the types of restrictive covenants en

forceable in equity, it is said:

‘ ‘ Such an agreement may occur in connection with

a conveyance of land, restricting the grantor, or the

subsequent transferees of the grantor, as regards the

use of the land retained by him, or restricting the

grantee as regards the use of the land conveyed. Or

it may be independent of any conveyance of land,

being merely an agreement between adjoining own

ers as regards the use of their land.”

In Wayt v. Patee, 205 Cal. 46, 269 P. 660 (1928),

the various lot owners in a sub-division entered into

a covenant restricting the use of their land by for

bidding occupancy “ by any persons other than of the

Caucasian race. ’ ’ One of the owners subsequently nego

tiated the sale of his lot to negroes. Certain of the other

lot owners brought an action in equity to enjoin the con

veyance to the negroes and to enjoin the negroes from

occupying the premises.

The court enforced the covenant and granted the in

junction even though it that case, as in the case at bar,

there was no privity of estate between the covenanting

parties.

In Corrigan v. Buckley, 299 F. 899, (Ct. of App. D. C.

1924), certain adjoining and neighboring property own

ers entered into a covenant against sale or rental to, or

occupancy by, negroes. Although there was no privity

of estate between the covenanting parties the court, nev

ertheless, at the instance of certain of the covenanting

parties, restrained another of the parties to the covenant

from selling to a negro.

In Russell v. Wallace, 30 F. (2d) 981, (Ct. of App. D.

C., 1929), the owners of the lots in Randolph Place, Wash

23

ington, D. C., together bound themselves by a covenant

against a transfer of any of the properties, in any man

ner, to negroes. Although, as here, there was no privity

of estate between the several parties to the covenant, the

court of equity nevertheless enforced the covenant at the

behest of certain of the lot owners and restrained a sale,

by one of the parties to the instrument, to negroes.

C. There Is No Adequate Remedy at Law.

The absence of adequate remedy at law is clear. A suf

ficient ground is that there is no privity of estate, it being

well-settled that “ by the common law no stranger to any

covenant, action or condition had any advantage or bene

fit of the same by any ways in the law, except such as

were parties or privies thereto.” Moale v. Tyson, 2 H.

& McH. 387, 388. It may also be suggested that the rem

edy at law would necessarily depend upon whether the

covenant is one which runs with the land. Glenn v. Can-

by, 24 Md. 127, 130; Whalen v. B. & 0. R. Co., 108 Md.

11, 20.

III.

T H E C O V E N A N T H A S N O T F A IL E D IN IT S P U R P O S E .

A . The Record Shows No Material Change in Conditions Since the

Execution of the Agreement.

The record utterly fails to show a material change in

conditions since the execution of the agreement. It is

true that the record would indicate that negroes live in

the 2300 block of Guilford avenue; that Brentwood ave

nue, a narrow street running from North avenue to Twen

ty-fifth street, between Barclay street and Greenmount

avenue, is inhabited by colored people; that an alley

known as Twenty-second and a half street, and Twenty-

third and part of Twenty-fourth streets are inhabited by

colored people; that there are two negro churches on

24

Twenty-third street; and that 2238 Barclay street is oc

cupied by colored people.

However, the instrument, containing the restrictive

covenant in question, is dated November 14, 1927, and

was recorded January 27,1928. At the time of the agree

ment there was a negro church on Twenty-third street,

Twenty-second and a half was colored and had been so

since the Great War, as also had Twenty-third street.

One colored family had already moved into the 2300 block

of Guilford avenue, which was, in fact, one of the reasons

for the neighborhood meeting out of which grew the cove

nant under consideration. The record fails to show

whether Brentwood avenue, or Twenty-fourth street were

colored when the agreement was signed.

On this record there is no evidence of substantial

change in the character of the neighborhood since the

restrictive agreement was signed. The surrounding

neighborhood was partially colored and was becoming in

creasingly so. Alarmed by a colored family moving into

the 2300 block of Guilford avenue, certain residents of

the nearby 2200 block of Barclay street banded together

and, by virtue of a restrictive covenant, sought to stem

the advancing tide of colored people. The one block in

Guilford avenue has become entirely colored, but the

signers of the covenant foresaw that that would probably

happen and for that very reason entered into the cove

nant in an effort to protect their own homes.

Indeed the only material change, in regard to negroes

occupying property in the entire restricted area of twen

ty-four square blocks was the occupancy of 2238 Barclay

street by colored persons. This has been the sole occu

pancy of Barclay street by a negro family since the sign

ing and recording of the covenant. This single occu

25

pancy by negroes has not so altered things, however, that

the original purpose of the signers in so restricting their

properties can no longer be accomplished. They are

still substantially removed and protected from undesir

able proximity with colored people as 2238 is on a corner,

at the end of the block. Furthermore the dressmaking

establishment on the first floor of 2238 draws no colored

people as it caters exclusively to white patrons, nor are

the upper floors objectionable as the entrance thereto is

on a side street which has always been colored. The 2200

block of Barclay street still is, to all intents and purposes

a white block, and the purpose of the covenant was to

preserve it as such.

This occupancy of 2238 Barclay street by colored peo

ple did not in itself amount to a breach of the covenant

as the owner of the property did not sign it. The lot

was, therefore, not subject to the restriction but was out

side of the restrictive tract both geographically and fig

uratively, and the change may be said to have taken place

outside of the restricted tract. No colored family had

ever occupied a house within the restricted area before

the appellant, Meade, moved into 2227.

B. There Is No Evidence That the Value of the Property Will Be

Diminished by Enforcing the Agreement.

It has also been contended that by reason of the large

number of colored families now occupying properties

close to the 2200 block of Barclay street, the said block

has already depreciated in value for occupancy by white

people, and the value of said properties would be greatly

increased by recognition of the invalidity of the agree

ment referred to and the right of occupancy by negroes.

Even if this were true (and the record fails to disclose

any testimony to support the contention), it would not

26

warrant a refusal by a court of equity to enforce the cove

nant. The mere fact that a property would be more valu

able if used for the purpose forbidden by a restrictive

covenant does not justify the refusal of a court of equity

to enforce the same.

In Allen v. Massachusetts Bonding & Ins. Co., 248

Mass. 378, 143 N. E. 499, 502 (1924), action was brought

in equity to enforce a restriction against digging a cellar

beyond a certain depth. One of the defendant’s reasons

for contending that the restrictions should not be en

forced was that greater value would attach to the prop

erty if free from the restriction. In holding that the

covenant should be enforced, the court said:

4 4 The great increment in the value of the land of

the defendant which will arise from refusal to en

force this restriction is of slight if any consequence.

The restriction was a matter of record in the chain

of the defendant’s title and the defendant was bound

by notice thereof.”

In Reeves v. Comfort, 172 Gfa. 331, 157 S. E. 629

(Ga. 1931), it was held that restrictive covenants run