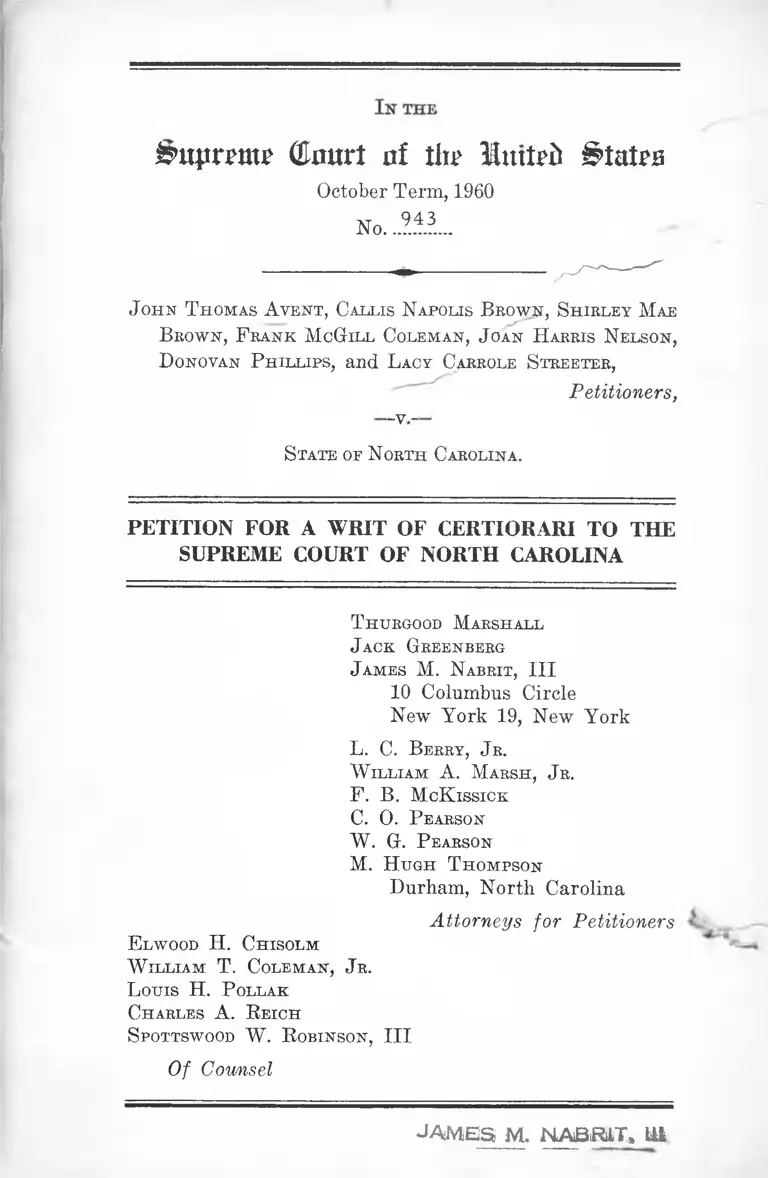

Avent v. North Carolina Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of North Carolina

Public Court Documents

March 6, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Avent v. North Carolina Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of North Carolina, 1961. 11dd2d7f-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/59c06a03-f55b-4641-ad29-6917e25c71f6/avent-v-north-carolina-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-north-carolina. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

jsatjm w (Hour! nf tln> Matted States

October Term, 1960

No. 943

J o h n T hom as A v e n t , C allis N apolis B ro w n , S h ir l e y M ae

B row n , F rank M cG il l C olem an , J oan H arris N elso n ,

D onovan P h il l ip s , a n d L acy Carrole S treeter ,

Petitioners,

- v -

S tate of N orth Carolina .

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

T hurgood M arshall

J ack Greenberg

J am es M. N abrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

L. C. B erry , J r .

W illia m A. M a rsh , J r.

F. B. M cK issic k

C. 0. P earson

W. G. P earson

M. H u g h T h o m pso n

Durham, North Carolina

E lwood H . C h iso lm

W illia m T. C olem an , J r.

L ouis H . P ollak

C harles A. R e ic h

S pottswood W. R obinson , III

Of Counsel

Attorneys for Petitioners

JA M ES M. NABJRilT, UI

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below.......................................... 1

Jurisdiction ..... ,....................................... .................... 1

Questions Presented ........................................... 2

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved .... 3

Statement ...................................................................... 3

How the Federal Questions Were Eaised and Decided 6

Reasons for Granting the Writ ........................ 11

I—The State of North Carolina has enforced racial

discrimination contrary to the equal protection

and due process clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States................................................................ . 12

II—The criminal statute applied to convict peti

tioners gave no fair and effective warning that

their actions were prohibited; petitioners’ con

duct violated no standard required by the plain

language of the law; thereby their conviction

offends the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment and conflicts with principles

announced by this Court.............................. 20

III—The decision below conflicts with decisions of

this Court securing the Fourteenth Amend

ment right to freedom of expression .... 26

Co n c l u s io n ................................................................... 30

A p p e n d ix ................................................................................................ l a

11

PAGE

T able, of C ases

Baldwin v. Morgan, —— F. 2d ----- (5th Cir, No.

18280, decided Feb. 17, 1961) ................................... 13

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ............................... 13

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28 ...... 18

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ................................... 13

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531___ 13

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622 ............................ 28

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .............. 13

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 ................. .......... 13,18

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 II. S. 495 ............................. . 29

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 29 U. S. L.

Week 4317 (April 17, 1961) ........................ 14,16,18,19

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 ...... ....... 26

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ...................................14,18

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1 ....................................... 13

District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., 346

U. S. 100...................................................................18,22

Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union, Washington Superior

Court, 45 Lab. Rel. Ref. Man. 2334 (1959) .............. 29

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 ................................... 13

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565 ........................ 14,19

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ............................... 24, 26

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 .................22, 24, 25

Lochner v. New York, 198 U. S. 45............................... 18

e-

McBoyle v. United States, 283 U. S. 25 ____ _____ 23, 25

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 ....................... ........15,18

Ill

PAGE

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141 ................................ 29

Maryland v. Williams, 44 Lab. Eel. Eef. Man. 2357

(1959) ............... ....................................................... . 28

Monroe v. Pape,-----U. S. —— , 5 L. ed. 2d 492 (1961) 13

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S. 113...................................... 18

N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 .................... 13, 29

N. L. E. B. v. American Pearl Button Co., 149 F. 2d

258 (8th Cir. 1945) .......... ................................. ......... 27

N. L. E. B. v. Fansteel Metal Corp., 306 U. S. 240 ....... 27

Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 U. S. 393 .......... 18

People v. Barisi, 193 Misc. 934, 86 N. Y. S. 2d 277 (1948) 28

Pierce v. United States, 314 U. S. 306 ........................ 22

Eailway Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88 ...... .......... 18

Eepublic Aviation Corp. v. National Labor Eelations

Board, 324 U. S. 793 ................................... ............. 27

Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 47 ............ ..... ...... 29

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 911............... ........ 13

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ........ ..........................13,15

State v. Clyburn, 247 N. C. 455, 101 S. E. 2d 295

(1958) ...................................................................... 20,21

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 __ _______ 14

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ........................ 29

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 .......... 22

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ........ .......... ......... 29

United States v. Cardiff, 344 U. S. 174....................... 23

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81 .... 24

United States v. Weitzel, 246 U. S. 533 .................... 23, 24

United States v. Willow Eiver Power Co., 324 U. S. 499 18

United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U. S. (5 Wheat.) 76 .... 23

United Steelworkers v. N. L. E. B., 243 F. 2d 593 (D. C.

Cir. 1956) ................................................................... 27

IV

PAGE

Valle v. Stengel, 176 F. 2d 697 (3rd Cir. 1949) .......... 13

Western Turf Asso. v. Greenberg, 204 U. S. 359 ...... 18

S tatutes

Code of Ala., Tit. 14, §426 ............................................... 25

Compiled Laws of Alaska Ann. 1958, Cum. Supp. Vol.

Ill, §65-5-112 ..... 25

Arkansas Code, §71-1803 ........................... ................... 25

Connecticut Gen. Stat. (1958 Rev.) §53-103 ................. 25

D. C. Code §22-3102 (Supp. VII, 1956) ........................ 25

Florida Code, §821.01 .................................................... 25

Hawaii Rev. Code, §312-1......... 25

Illinois Code, §38-565 ..................................................... 25

Indiana Code, §10-4506 ................................................. 25

Mass. Code Ann. C. 266, §120 ....................................... 25

Michigan Statutes Ann. 1954, Vol. 25, §28.820(1) ...... 25.

Minnesota Statutes Ann. 1947, Vol. 40, §621.57 .......... 25

Mississippi Code, §2411 .......... 25

Nevada Code, §207.200 ............ 25

N. C. Gen. Stat. §14-126.................................................. 21

N. C. Gen. Stat. §14-134 ................................... 3, 6, 7, 8, 21

Oregon Code, §164.460 .................................................. 25

Ohio Code, §2909.21 ..................................................... 25

V

PAGE

Code of Virginia, 1950, §18.1-173 ......................... ...... 25

Wyoming Code, §6-226 ............................. .................. 25

28 IT. S. C. §1257(3) ..................................... ................ 2

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

Ballantine, “Law Dictionary” (2d Ed. 1948) 436 ...... 26

“Black’s Law Dictionary” (4th Ed. 1951) 625 .......... 26

Pollitt, “Dime Store Demonstrations: Events and

Legal Problems of the First Sixty Days,” 1960 Duke

Law Journal 315.......................................... 20

5 Powell on Beal Property 493 (1956) ..................... 18

I n t h e

Olmtrt of tlu> I n M Stairs

October Term, 1960

No............

J o h n T h o m a s A v e n t , Ca llis N apolis B r o w n , S h ir l e y M ae

B r o w n , F r a n k McGtll C o lem a n , J oan H arris N el so n ,

D onovan P h il l ip s , a n d L acy C arrole S tr e e t e r ,

—v.—

Petitioners,

S tate of N o rth Carolina .

P E T IT IO N FO R A W R IT O F C E R T IO R A R I T O T H E

SU PR EM E CO U R T O F N O R T H CAROLINA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issne to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

entered in the above-entitled cause on January 20, 1961.

C itations to O p in io n s Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina is

reported at 118 S. E. 2d 47 and is set forth in the appendix

attached hereto, infra, p. la.

J u r is d ic tio n

The judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

was entered January 20, 1961 (Clerk's certificate attached

hereto, infra, App., p. 22a).1 On April 4, 1961, time for

1 The Clerk’s certificate recites that final judgment was entered

on January 20, 1961. The record, however, contains no actual form

2

filing a petition for writ of certiorari was extended by the

Chief Justice to and including May 4, 1961. Jurisdiction

of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §1257(3),

petitioners having asserted below and claiming here, denial

of rights, privileges and immunities secured by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment suffer the state to use its

executive and judiciary to enforce racial discrimination in

a business that has for profit opened its property’ to the

general public while using the state criminal trespass stat

ute to enforce racial discrimination within the same prop

erty.

2. Whether, where the criminal statute applied to con

vict petitioners gave no fair and effective warning that

their actions were prohibited, and their conduct violated no

standard required by the plain language of the law, the

conviction offends the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

3. Whether the decision below conflicts with decisions

of this Court securing the Fourteenth Amendment right

to liberty of expression.

of judgment. Upon inquiry to the Clerk, he informed counsel for

petitioners that the judgment is a paper prepared by the Clerk.

Because stay of execution was obtained before he prepared this

paper, he did not actually complete it and place it in the record.

3

S ta tu to ry a n d C o n s titu tio n a l

P ro v is io n s Invo lved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This ease also involves North Carolina General Stat

utes, §14-134:

Trespass on land after being forbidden. “If any

person after being forbidden to do so, shall go or enter

upon the lands of another, without a license therefor,

he shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and on conviction,

shall be lined not exceeding fifty dollars or imprisoned

not more than thirty days.”

S ta te m e n t

This is one of 2 eases filed here today (the other is State

v. Fox, No. 442, Supreme Court of North Carolina, Fall

Term, 1960 reported at 118 S. E. 2d 58) involving whether

a state may use its criminal trespass statute to enforce

racial segregation according to the customs of the com

munity in one portion of a commercial establishment other

wise open to the public without segregation. The issues

are similar to those presented by Garner, Briscoe and

Boston v. State of Louisiana, Nos. 617, 618 and 619, re

spectively, certiorari granted March 20, 1961, in which a

state employed a statute forbidding disturbing the peace

for this purpose.

May 6, 1960, petitioners, five Negro students from North

Carolina College, Durham, North Carolina (R. 35, 40, 44-

45, 48, 49) and two white students from Duke University,

Durham (R. 42, 47) were customers of Kress’s Department

Store, Durham. The store, in a five story building (R. 20)

4

has approximately fifty counters (including a “stand-up”

lunch counter) which serve Negroes and whites without

racial distinction (R. 22). No sign at the store’s entrance

barred or conditioned Negro patronage (R. 22). Petitioners

made various purchases (R. 36, 40, 43, 47, 48, 49), as some

of them had in the past as regular customers (R. 36, 41,

43, 45, 48), and in time went to the basement lunch counter.

Here a sign stated “Invited Guests and Employees Only”

(R. 21, 23). No writing further elucidated this sign’s mean

ing, but the manager testified that although no invitations

as such were sent out, white persons automatically were

considered guests; Negroes and whites accompanied by

Negroes were not (R. 22-23). The counter was bordered by

an iron railing (R. 21) and petitioners entered through the

normal passageway (R. 38).

Some of the petitioners had requested and had been

denied service on previous occasions at this counter (R.

38). However, they “continued to try” and at this time

again “went there for service” (R. 38). They expected to

be served at the basement lunch counter because they had

been served upstairs (R. 50). They had not been arrested

previously for trespassing and were not arrested for tres

passing upon entering the store through its main doors.

Nor did they expect to be arrested for trespassing on this

occasion (R. 38, 44, 50).

Petitioners were participants in an informal student or

ganization which opposed racial segregation (R. 40), and

felt they had a right to service at Kress’s basement lunch

counter after having been customers in other departments

(R. 40, 42, 50; and see R. 46 (objection to question sus

tained)). Some had picketed the store to protest its policy

of welcoming Negroes’ business while refusing them lunch

counter service (R. 37, 42, 50).

5

The manager again declined to serve them. He stated

that if Negroes wanted service they might obtain it at the

back of the store (R. 24), or at a stand-up counter upstairs

(R. 22), and asked them to leave (R. 21).

“It is the policy of our store to wait on customers depen

dent upon the custom of the community” (R. 22), he testi

fied. “It is not the custom of the community to serve

Negroes in the basement luncheonette, and that is why

we put up the signs ‘Invited Guests and Employees Only’ ”

(R. 23).

When petitioners remained seated awaiting service, the

manager called the police to enforce his demand (R. 21).

An officer promptly arrived and asked petitioners to leave

(R. 21). Upon refusal the officer arrested them for tres

passing (R. 21, 4). Petitioners were indicted in the Su

perior Court of Durham County, the indictments stating

that each petitioner

‘■with force and arms, . . . did unlawfully, willfully

and intentionally after being forbidden to do so, enter

upon the land and tenement of S. H. Kress and Co.

store . . . said S. H. Kress and Co., owner, being then

and there in actual and peaceable possession of said

premises, under the control of its manager and agent,

W. K. Boger, who had, as agent and manager, the

authority to exercise his control over said premises,

and said defendant after being ordered by said W. K.

Boger, agent and manager of said owner, S. II. Kress

and Co., to leave that part of the said store reserved

for employees and invited guests, willfully and unlaw

fully refused to do so knowing or having reason to

know that . . . [petitioner] had no license therefor,

against the form of the statute in such case made and

provided and against the peace and dignity of the

state.” (R. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6,7,8.)

6

Each indictment identified each petitioner as “CM”

(colored male) (E. 3, 4, 7, 8), “WM” (white male) (E. 5),

“CF” (colored female) (E. 6), or “WF” (white female)

(E. 9). Defendants made motions to quash the indictment

(see infra, pp. 6-7), which raised defenses under the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

These were denied (E. 10-12).

Petitioners were tried June 30 and July 1, 1960 (E. 20).

They pleaded not guilty (E. 15) and were found guilty (E.

15). Various federal constitutional defenses (see infra,

pp. 7-9), were made throughout and at the close of the

trial, but were overruled. Petitioners Coleman, Phillips

and Callis Napolis Brown were sentenced to thirty days

imprisonment in the common jail of Durham County to

work under the supervision of the State Prison Depart

ment (E. 16, 17, 18). Petitioner Streeter was sentenced

similarly to twenty days (E. 19). Petitioner Avent was

sentenced to fifteen days in the Durham County jail (E.

15). Prayer for judgment was continued in the cases of

petitioners Shirley Mae Brown and Joan Harris Nelson

(E. 16-17).

Error was assigned, again raising and preserving fed

eral constitutional defenses (see, infra, pp. 9-11), and the

case was heard by the Supreme Court of North Carolina

which affirmed on January 20, 1961 (Clerk’s certificate fol

lowing court’s opinion).

H ow th e F e d e ra l Q uestions

W ere R aised a n d D ecided

Prior to trial petitioners filed motions to quash the in

dictment.

The Negro petitioners alleged that G. S. 14-134 was un

constitutionally applied to them in that while using facili-

7

ties of S. H. Kress and Company, which was licensed by

the City and County of Durham to carry on business open

to the general public, they were charged with trespass on

account of race and color contrary to the equal protection

and due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment;

that G. S. 14-134 denied due process of law secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment in that it was unconstitutionally

vague; that G. S. 14-134 was unconstitutional under the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment because the arrest was made to aid S. H.

Kress and Company, which was open to the public, in en

forcing its whims and caprices against serving members

of the Negro race on the same basis as members of other

races, all of whom had been invited to use said establish

ment; that the defendants who were on the premises of

S. H. Kress and Company pursuant to an invitation to the

general public, were denied the use of said establishment

solely because of race and color, and were arrested for at

tempting to exercise the right of invitees to equal treatment,

contrary to the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment (R. 10-12).

The white petitioners made identical allegations except

that instead of stating that they were denied constitutional

rights because of race, they charged that they were indicted

because of association with the Negro petitioners (R 12-

14).

The motions to quash were denied and exception was

taken thereto (R. 12,14).

Following the State’s evidence the Negro petitioners

made Motions for Dismissal as of Nonsuit (R. 26-35).

These alleged that petitioners entered S. H. Kress’s store

to shop and use its facilities; that they had purchased other

articles in the store; had been trading there for a long

time prior to arrest; had entered the store in orderly fash-

8

ion; and were arrested when they took seats and requested

service at the lunch counter. The motions prayed for non

suit pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment in that en

forcement of G. S. 14-134 in these circumstances was state

action forbidden by the equal protection and due process

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment; that defendants

were denied rights secured by the Civil Eights Act of 1866

which assures to all citizens the same right in every state

and county as is enjoyed by white citizens to purchase

personal property; that S. H, Kress and Company was

operating under a license of the City of Durham and,

therefore, petitioners’ arrest at the owner’s behest violated

the rights secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States; that G. S. 14-134 denied

due process of law secured by the Fourteenth Amendment

in that it was vague; that G. S. 14-134 denied due process

of law and the equal protection of the laws in that it was

applied to carry out the whims and caprices of the pro

prietor against members of the Negro race; and that peti

tioners were denied rights secured by the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment by

being arrested for attempting to exercise rights to equal

treatment as invitees of S. H. Kress and Company. These

motions were denied and exception was taken thereto (E.

30).

Similar motions filed on behalf of the white petitioners

alleged that they had been denied these rights because of

association with Negroes (E. 30-33). These motions were

denied and exception was taken thereto (E. 33).

Additional Motions for Dismissal as of Nonsuit alleged

that S. H. Kress was performing an economic function in

vested with the public interest; that petitioners were peace

fully upon the premises; that there was no basis for the

charge other than an effort to exclude petitioners from

9

the store solely because of race; that petitioners were at

the same time excluded from equal service at the prepon

derant number of other eating establishments in the City

of Durham, and that the charge recited by the indictment

denied to petitioners due process of law and the equal

protection of the laws secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

The motion also alleged that petitioners were at all times

upon an area essentially public; at no time were they defi

ant or in breach of the peace; that they were peacefully

exercising rights of assembly and speech to protest racial

segregation; that the prosecution was procured for the

purpose of preventing petitioners from speaking and other

wise peacefully protesting the refusal of the preponderant

number of stores open to the public in the City of Durham

to permit Negroes to enjoy certain facilities and that the

arrests were in aid of this policy all contrary to the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

These motions were denied and exceptions were taken

thereto (R. 34-35).

Following the close of petitioners’ case they renewed

their written motions to quash the indictments and for dis

missal as of nonsuit. This motion was denied and exception

was taken thereto (R. 51).

Assignments of Error were filed against the action of

the Court in overruling the Motion to Quash (Assignments

1 and 2, R. 70), in overruling the motion for judgment as

of nonsuit (Assignments 4, 5, 6 and 7, R. 71), and to the

action of the Court in overruling defendants’ motions to

quash the indictments and for dismissal as of nonsuit made

at the close of all the evidence (Assignment 10, R. 71).

10

The Supreme Court of North Carolina disposed ad

versely of these constitutional claims. It concluded its

opinion by stating:

“All of the assignments of error by the defendants

have been considered, and all are overruled. Defen

dants have not shown the violation of any of their

rights, or of the rights of any one of them, as guar

anteed by the 14th Amendment to the Federal Con

stitution, and by Article I, §17, of the North Carolina

Constitution.” (App. p. 21a.)

In explication it held that:

“In the absence of a statute forbidding discrimina

tion based on race or color in restaurants, thg rule is

well established that an operator of a privately owned

restaurant privately operated in a privately owned

building has the right to select the clientele he will

serve, and to make such selection based on color, race,

or White people in company with Negroes or vice

versa, if he so desires. He is not an innkeeper. This

is the common law.” (App. p. 7a.)

Moreover, the opinion held tha t:

“ ‘The right of property is a fundamental, natural,

inherent, and inalienable right. It is not ex gratia from

the legislature, but ex debito from the Constitution.

In fact, it does not owe its origin to the Constitutions

which protect it, for it existed before them. It is some

times characterized judicially as a sacred right, the

protection of which is one of the most important ob

jects of government. The right of property is very

broad and embraces practically all incidents which

property may manifest. Within this right are included

11

the right to acquire, hold, enjoy, possess, use, man

age, . . . property.’ 11 Am. Jur., Constitutional Law,

§335.” (App. p. 11a.)

To the argument that the action taken below constitutes

state action contrary to the due process and equal protec

tion clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Court held:

“Defendants misconceive the purpose of the judi

cial process here. It is to punish defendants for unlaw

fully and intentionally trespassing upon the lands of

S. H. Kress and Company, and for an unlawful entry

thereon, even though it enforces the clear legal right of

racial discrimination of the owner.” (Emphasis sup

plied.) (App. p. 12a.)

Moreover, no freedom of speech and assembly were de

nied, the Court held:

“No one questions the exercise of these rights by the

defendants, if exercised at a proper place and hour.

However, it is not an absolute right.” (App. p. 16a.)

R easons f o r G ra n tin g th e W rit

This case involves substantial questions affecting im

portant constitutional rights, resolved by the court below

in conflict with principles expressed by this Court.

12

I.

T h e S ta te o f N o rth C a ro lin a h a s e n fo rc e d ra c ia l d is

c r im in a tio n c o n tra ry to th e e q u a l p ro te c tio n a n d d u e

p ro ce ss c lauses o f th e F o u r te e n th A m e n d m e n t to th e

C o n s titu tio n o f th e U n ited S tates.

Petitioners seek certiorari to the Supreme Court of North

Carolina, having unsuccessfully contended below that their

conviction constitutes state enforcement of racial discrimi

nation contrary to the equal protection and due process

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. In rejecting peti

tioners’ claim, the court below held that “ . . . the purpose

of the judicial process” was “ . . . to punish defendants

for unlawfully and intentionally trespassing upon the lands

of S. II. Kress and Company, and for an unlawful entry

thereon, even though it enforces the clear legal right of

racial discrimination of the owner” (App. p. 12a). An

swering the claim that this was state action prohibited by

the Fourteenth Amendment, the court below replied that

the right of property is “fundamental, natural, inherent

and inalienable,” being “not ex gratia from the legislature,

but ex debito from the Constitution” (App. p. 11a); that

the right could be characterized as “sacred” ; and that the

North Carolina trespass laws were “color blind,” their sole

purpose being to protect property from trespassers (Id.).

The Court held that the police and judicial action in arrest

ing and convicting petitioners “cannot fairly be said to be

state action enforcing racial segregation in violation of the

14th Amendment to the Federal Constitution” (App. p.

13a).

But from the officer’s orders to depart to the final judg

ment of the highest state court, this has been the state’s

cause. Judicial acts of state courts are “state action” un-

13

der the Fourteenth Amendment. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. I.2 Equally clear, the Amendment reaches conduct of

the police. Cf. Monroe v. Pape, —-— U. S. ----- , 5 L. ed.

2d 492 (1961); Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91. See

also Baldwin v. Morgan,-----F. 2d------(5th Cir. No. 18280,

decided Feb. 17, 1961); Bonian v. Birmingham Transit Co.,

280 F. 2d 531, 533, note 1 (5th Cir. 1960); Valle v. Stengel,

176 F. 2d 697 (3rd Cir. 1949), all of which condemn police

enforcement of racial segregation in public places.

State action which enforces racial discrimination and

segregation is condemned by the Fourteenth Amendment’s

equal protection clause. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S.

60; Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Shelley

y. Kraemer, supra; Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903. More

over, state inflicted racial discriminations, bearing no ra

tional relation to a permissible governmental purpose,

offend the concept of due process. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347

IT. S. 497; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1.

For the state to infect the administration of its criminal

laws by using them to support lunch counter segregation

2 The subject of judicial action as “state action” is treated ex

haustively in Part II of Chief Justice Vinson’s opinion which

concludes:

“The short of the matter is that from the time of the adop

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment until the present, it has

been the consistent ruling of this Court that the action of the

States to which the Amendment has reference, includes action

of state courts and state judicial officials. Although in con

struing the terms of the Fourteenth Amendment, differences

have from time to time been expressed as to whether particular

types of state action may be said to offend the Amendment’s

prohibitory provisions, it has never been suggested that state

court action is immunized from the operation of those pro

visions simply because the act is that of the judicial branch

of the state government.” (Id. at 18.)

In addition to the many cases cited in Shelley, supra, at 14-18,

see also: Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249; N.A.A.G.P. v. Alabama,

357 U. S. 449, 463.

14

as an aspect of the “customs” of a segregated society,

offends the salutary principle that criminal justice must

be administered “without reference to consideration based

upon race.” Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565, 591.

Indeed, when the Supreme Court of North Carolina held

that the state judicial process “enforces the clear, legal

right of racial discrimination of the owner” (App. p. 12a),

it “construed this legislative enactment as authorizing dis

criminatory classification based exclusively on color.” Cf.

Mr. Justice Stewart, concurring in Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 29 U. S. Law Wk. 4317, 4320. And, as

Mr. Justice Frankfurter wrote, dissenting in the Burton

case, “for a State to place its authority behind discrimina

tory treatment based solely on color is indubitably a denial

by a State of the equal protection of the laws, in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment.” (Ibid.)

The Fourteenth Amendment from the beginning has

reached and prohibited all racial discrimination save that

“unsupported by State authority in the shape of laws, cus

toms, or judicial or executive proceedings,” and that which

is “not sanctioned in some way by the State,” Civil

Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 17. “State action of every kind

. . . which denies . . . the equal protection of the laws”

is prohibited by the Amendment. Id. at 11; cf. Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority; supra. The Fourteenth

Amendment was “primarily designed” to protect Negroes

against racial discrimination. Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U. ,S. 303, 307. “The words of the Amendment, it is

true, are prohibitory, but they contain a necessary implica

tion of a positive immunity, or right, most valuable to the

colored race—the right to exemption from . . . legal dis

criminations, implying inferiority in civil society, lessening

the security of their enjoyment of the rights which others

enjoy.. . . ” (Ibid.)

15

The fact that a property interest is involved does not

imply a contrary result. It is the state’s power to enforce

such interests that is in issue. For, as the Court said in

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22:

“ • • - It would appear beyond question that the power

of the State to create and enforce property interests

must be exercised within the boundaries defined by the

Fourteenth Amendment. Cf. Marsh v. Alabama, 326

U. S. 501.”

Indeed, as the Court said in Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S.

501, 505-506:

“We do not agree that the corporation’s property

interests settle the question. The State urges in effect

that the corporation’s right to control the inhabitants

of Chickasaw is coextensive with the right of a home-

owner to regulate the conduct of his guests. We can

not accept that contention. Ownership does not always

mean absolute dominion. The more an owner, for his

advantage, opens up his property for use by the public

in general, the more do his rights become circumscribed

by the statutory and constitutional rights of those who

use it.”

Here, certainly, is the case of “an owner, [who] for his

advantage, opens up his property for use by the public in

general.”

Petitioners contend that the states may not, under the

Fourteenth Amendment, use their police3 and judiciary

3 The arresting officer took full responsibility for the arrest:

“After Mr. Boger asked these defendants to leave, in my

presence, and they refused to leave, that constituted trespass

ing. He did not sign the warrants after the arrest. I did not

have a warrant with ine when we made the arrest. Mr. Boger

did not sign the warrant before we arrested them” (R. 25).

16

to enforce racial discrimination for a business open to the

general public. Analyzing the totality of circumstances,

with regard for the nature of the property interests as

serted, and the state’s participation in their creation and

enforcement no property interest of such an enterprise

warrants departing from the Fourteenth Amendment’s

clear stricture against racial discrimination. As this Court

said recently in Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

29 U. S. Law Week 4317, 4318 (April 17, 1961):

“Because the virtue of the right to equal protection of

the laws could lie only in the breadth of its applica

tion, its constitutional assurance was reserved in terms

whose imprecision was necessary if the right were to

be enjoyed in the variety of individual-state relation

ships which the Amendment was designed to embrace.

For the same reason, to fashion and apply a precise

formula for recognition of state responsibility under

the Equal Protection Clause is ‘an impossible task’

which ‘this Court has never attempted.’ Kotch v. Pilot

Comm’rs, 330 U. S. 552, 556. Only by sifting facts and

weighing circumstances can the nonobvious involve

ment of the State in private conduct be attributed its

true significance.”

©

What is the “property right” involved here! S. H. Kress

and Company did business in a commercial building opened

to the public as a whole for the business advantage of the

owner© There was no practice of selecting customers or

limiting the classes of persons who may enter. The store

was not, as some may be, limited to men, women, adults,

white persons or Negroes. Negroes were accommodated

throughout the building except the basement lunch counter

(R. 22p No claim or interest in privacy was exercised by

the owner in the customary use of this building.

17

6s-

The specific area in dispute, the lunch counter, was an

integral part of this single commercial establishment, and

like the entire premises was open to the public to do busi

ness for profit. It was not severed for the owner’s private

use; nor was it like a stockroom, employees’ working area,

or a living space connected to a store.

(j? There is no issue concerning protection of property from

use alien to its normal intended function. Petitioners

sought only to purchase food. Whatever their motives (a

frankly acknowledged desire to seek an end to racial dis

crimination), their actions conformed to those of ordinary

purchasers of food. Petitioners were not disorderly or

offensive. The manager’s sole objection was that some of

them were Negroes and the others accompanied Negroes.

The sole basis of exclusion, ejection, arrest and conviction

was race. The “crime” was being Negroes, or being with

Negroes, at a “white only” lunch counter.

Moreover, the manager testified that the lunch counter

was segregated “in the interest of public safety” (R. 22),

and that company policy throughout the country was “de

pendent upon the customs of the community” (R. 22). Ob

viously then, the asserted right here is related to participa

tion in, or conformity with, a community custom of segrega

tion, the maintenance of a segregated society.

Therefore, the asserted “property” right was simply the

right to discriminate solely on the basis of race, and accord

ing to the customs of the community, in one integral part

of a single commercial building open to the general public

against persons otherwise welcome in all other parts of

the premises. This, indeed, may be called a “property

right” but as thus revealed, it is far from the “sacred, nat

ural, inherent and inalienable” property right (App. p.

11a) which the generalized language of the court below

18

held to be at stake. For as Mr. Justice Holmes wrote, dis

senting in Lochner v. New York, 198 U. S. 45, 76, “ [g en

eral propositions do not decide concrete cases.”

The arbitrary quality of the “property right” supported

by the state’s trespass law here is emphasized by the fact

that the Kress Company required segregation only for

customers who sit to eat; those standing to eat in the same

store were served without any racial discrimination (R. 22).

Cf. Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, supra, term

ing exclusion of a Negro as offensive in a restaurant and

his acceptance in other parts of the same building “irony

amounting to grave injustice.” 29 U. S. L. Week 4317.

This “property interest” hardly need be protected in

order for our form of constitutional government to survive

(see App. pp. 13a, 15a). Obviously, for example, this type

of “property interest” may be taken away by the states with

out denying due process of law.4 Indeed, mere reference

to the common law duty of common carriers and innkeepers

demonstrates that an owner’s use of his property affects

the nature of his dominion over it. Cf. Civil Rights Cases,

109 U. S. 3, 25. This Court has said on several occasions,

“that dominion over property springing from ownership is

not absolute and unqualified.” Buchanan v. Warley, 245

U. S. 60, 74; United States v. Willow River Power Co., 324

U. S. 499, 510; Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 506;

Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 U. S. 393, 417 (Jus

tice Brandeis’s dissenting opinion). See Munn v. Illinois,

94 U. S. 113; 5 Powell on Real Property 493 et seq. (1956).

4 See for example, Western Turf Asso. v. Greenberg, 204 U. S.

359; cf. Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.'S. 28; Railway

Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88; District of Columbia v. John R.

Thompson Co., 346 U. S. 100.

19

This case does not involve a claim that the state must

affirmatively provide a legal remedy against “private”

racial discrimination. (Cf. Burton v. Wilmington Parking,.

Authority, 29 U. S. Law Week 4317, April 17, 1961).

Rather, petitioners assert only their immunity from

criminal prosecution. Nor is there involved judicial en

forcement of racial discrimination by trespass laws to

protect an owner’s interest in maintaining privacy in the

use of his property, such as a home or private club. Coun

tervailing considerations that may be involved when a state

acts to protect its citizens’ interest in their privacy, are not

present. There is no issue as to whether state trespass laws

may be used to enforce an exclusion for no reason. Finally,

there is no claim that the Fourteenth Amendment bars

enforcement of trespass laws generally.

Consequently, the case involves only this highly, im

portant issue: Whether the state may use its executive

and judicial machinery (particularly its criminal laws) to

enforce 'racial discrimination for a business company that

by its own choice and for its own advantage has opened

its commercial property to the public. Petitioners submit

that prior decisions of this Court demonstrate this ques

tion should be answered No.

This case merits plenary review in this Court because of

the substantial public importance of the questions relating

to the extent to which a state may use its criminal laws to

enforce racial segregation. As indicated to the Court in

petitions for-certiorari filed and granted in Garner, Bris

coe, and Hoston v. State of Louisiana, Nos. 617, 618 and

619, October Term 1960, this problem is one which has

arisen in many different communities and many state courts

since the spring of 1960. See, Pollitt, “Dime Store Demon-

20

strations: Events and Legal Problems of the First Sixty

Days,” 1960 Duke Law Journal 315. Beview of this ease

will facilitate the proper disposition of many similar crim

inal prosecutions.

II.

T h e c rim in a l s ta tu te a p p lie d to conv ic t p e ti tio n e rs

gave n o f a i r a n d effective w a rn in g th a t th e i r ac tio n s

w ere p ro h ib i te d ; p e ti t io n e rs ’ c o n d u c t v io la ted n o

s ta n d a rd re q u ire d by th e p la in language o f th e law ;

th e re b y th e ir co n v ic tio n o ffends th e d u e p ro cess c lau se

o f th e F o u r te e n th A m e n d m e n t a n d con flic ts w ith p r in

c ip les a n n o u n c e d by th is C ou rt.

Petitioners were convicted under North Carolina Gen

eral Statute, §14-134, which provides:

If any person after being forbidden to do so, shall

go or enter upon the lands of another without a license

therefor, he shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and on

conviction, shall be fined not exceeding fifty dollars,

or imprisoned not more than thirty days.

Although the statute in terms prohibits only going on

the land of another after being forbidden to do so, the

Supreme Court of North Carolina has now construed the

statute to prohibit also remaining on property when

directed to leave following lawful entry. (See Opinion

below, App. p. 12a). Stated another way, the statute

now is applied as if “remain” were substituted for “enter.”

Expansive judicial interpretation of the statute began by

a statement in State v. Clyburn, 247 N. C. 455, 101 S. E. 2d

295 (1958) (a case in which defendants deliberately ig-

21

nored racial signs posted outside an ice cream parlor and

also refused to leave upon demand),5 92 years after en

actment of the law.6

The instant case is the first unambiguous holding under

§14-134 which convicts defendants who went upon property

with permission and merely refused to leave when directed.

Without a doubt petitioners and all Negroes were wel

come within the. store—apart from the basement lunch

counter. The arresting officer stated that “The only crime

committed in my presence, as I saw, it was their failure

and refusal to leave when they were ordered to do so by

the Manager” (R. 26). There were no discriminatory signs

outside the store (R. 23). No sign forbade Negroes and

white persons who accompany Negroes to sit at the lunch

counter; the sign said merely “Employees and Invited

Guests Only” (R. 21). Whatever petitioners’ knowledge

of the store’s racial policy as it had been practiced, there

was no suggestion that they had ever been forbidden to

go to the lunch counter and request service. The Court’s

conclusory statement that defendants “entered” (tres

passed) “after having been forbidden to do so” (App.

19a), was simply a holding that' defendants’ acts in fail

ing to leave when directed violated the statute.

5 In the Clyburn opinion, and here, the State court explained

construction of §14-134 by reference to analogous construction of

a statute prohibiting forcible entry and detainer (N. C. Gen. Stat.

§14-126), which had been construed to apply to peaceful entry

followed by forcible opposition to a later demand to leave. The

Court held that “entry” was synonymous with “trespass” in both

statutes (14-126 and 14-234). (14-134 does not use the word

“entry” ; it states “go or enter upon”.)

The facts of the Clyburn case are summarized in the opinion

below in this case (App. pp. 8a-9a).

6 The Statute was first enacted in 1866. North Carolina Laws

Special Session, Jan., 1866, C. 60.

22

Absent the special expansive interpretation given §14-

134 by the North Carolina Supreme Court the case would

plainly fall within the principle of Thompson v. City of

Louisville, 362 U. S. 199, and would be a denial of due

process of law as a conviction resting upon no evidence

of guilt. There was obviously no evidence that petitioners

entered the premises “after having been forbidden to do

so,” and the conclusion that they did rests solely upon the

special construction of the law.

Under familiar principles the construction given a state’s

statute by its highest court determines its meaning. How

ever, petitioners submit that this statute has been so

judicially expanded that it does not give a fair and ef

fective warning of the acts it now prohibits. Rather, by

expansive interpretation the statute now reaches more than

its words fairly and effectively define, and as applied it

therefore offends the principle that criminal laws must

give fair and effective notice of the acts they prohibit.

The due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

requires that criminal statutes be sufficiently explicit to

inform those who are subject to them what conduct on

their part will render them criminally liable. “All are

entitled to be informed as to what the State commands or

forbids”, Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451, 453, and

cases cited therein in note 2.

Construing and applying federal statutes this Court has

long adhered to the principle expressed in Pierce v. United

States, 314 U. S. 306, 311:

. . . judicial enlargement of a criminal act by inter

pretation is at war with a fundamental concept of

the common law that crimes must be defined with ap

propriate definiteness. Cf. Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306

U. S. 451, and cases cited.

23

In Pierce, supra, the Court held a statute forbidding false

personation of an officer or employee of the United States

inapplicable to one who had impersonated an officer of the

T. V. A. Similarly in United States v. Cardiff, 344 U. S.

174, this Court held too vague for judicial enforcement a

criminal provision of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cos

metic Act which made criminal a refusal to permit entry

or inspection of business premises “as authorized by” an

other provision which, in turn, authorized certain officers

to enter and inspect “after first making request and ob

taining permission of the owner.” The Court said in Car

diff, at 344 U. S. 174, 176-177:

The vice of vagueness in criminal statutes is the

treachery they conceal either in determining what per

sons are included or what acts are prohibited. Words

which are vague and fluid (cf. United States v. L.

Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81) may be as much of

a trap for the innocent as the ancient laws of Caligula.

We cannot sanction taking a man by the heels for

refusing to grant the permission which this Act on

its face apparently gave him the right to withhold.

That would be making an act criminal without fair

and effective notice. Cf. Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S.

242.

The Court applied similar principles in McBoyle v. United

States, 283 U. S. 25, 27; United States v. Weitzel, 246 U. S.

533, 543, and United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U. S. (5

Wheat.) 76, 96. Through these cases runs a uniform ap

plication of the rule expressed by Chief Justice Marshall:

It would be dangerous, indeed, to carry the prin

ciple, that a case which is within the reason or mis

chief of a statute, is within its provisions, so far as

to punish a crime not enumerated in the statute, be-

24

cause it is of equal atrocity, or of kindred character,

with those which are enumerated (Id. 18 (J. S. (5

Wheat.) at 96.)

The cases discussed above involved federal statutes con

cerning which this Court applied a rule of construction

closely akin to the constitutionally required rule of fair

and effective notice. This close relationship is indicated

by the references to cases decided on constitutional grounds.

The Pierce opinion cited for comparison Lametta v. New

Jersey, supra, and “cases cited therein,” while Cardiff

mentions United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., supra,

and Herndon v. Lowry, supra.

On its face the North Carolina trespass statute warns

against a single act, i.e., going or entering upon the land

of another “after” being forbidden to do so. “After” con

notes a sequence of events which by definition excludes

going on or entering property “before” being forbidden.

The sense of the statute in normal usage negates its ap

plicability to petitioners’ act of going on the premises with

permission and later failing to leave when directed.

But by judicial interpretation “enter” was held syn

onymous with “trespass,” and, in effect, also with “remain.”

Here a legislative casus omissus was corrected by the

court. But as Mr. Justice Brandeis observed in United

States v. Weitzel, supra at 543, a casus omissus while not

unusual, and often undiscovered until much time has

elapsed, does not justify extension of criminal laws by

reference to legislative intent.

Moreover, that the indictments specified both that peti

tioners had entered after having been forbidden and also

that they refused to leave after being ordered to do so,

does not correct the unfairness inherent in the statute’s

25

failure specifically to define a refusal to leave as an of

fense. As this Court said in Lametta v. New Jersey,

swpra:

It is the statute, not the accusation under it, that

prescribes the rule to govern conduct and warns

against transgression. See Stromberg v. California,

283 U. S. 359, 368; Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444.

Petitioners do not contend for an unreasonable degree

of specificity in legislative drafting. Some state trespass

laws have specifically recognized as distinct prohibited

acts the act of going upon property after being forbidden

and the act of remaining when directed to leave.7

Converting by judicial construction the common English

word “enter” into a word of art meaning “trespass” or

“remain,” has transformed the statute from one which

fairly warns against one act into a law which fails to

apprise those subject to it “in language that the common

word will understand, of what the law intends to do if a

certain line is passed” (McBoyle v. United States, 283 U. S.

27). Nor does common law usage of the word “enter”

7 See for example the following state statutes which do effectively

differentiate between “entry” after being forbidden and “remain

ing” after being forbidden. The wordings of the statutes vary but

all of them effectively distinguish the situation where a person has

gone on property after being forbidden to do so, and the situation

where a person is already on property and refuses to depart after

being directed to do so, and provide separately for both situations:

Code of Ala., Title 14, §426; Compiled Laws of Alaska Ann. 1958,

Cum. Supp. Yol. Ill, §65-5-112; Arkansas Code, §71-1803; Gen.

Stat. of Conn. (1958 Rev.), §53-103; D. C. Code §22-3102 (Supp.

VII, 1956); Florida Code, §821.01; Rev. Code of Hawaii, §312-1;

Illinois Code, §38-565; Indiana Code, §10-4506; Mass. Code Ann.

C. 266, §120; Michigan Statutes Ann. 1954, Vol. 25, §28.820(1);

Minnesota Statutes Ann. 1947, Vol. 40, §621.57; Mississippi Code

§2411; Nevada Code, §207.200; Ohio Code, §2909.21; Oregon Code,

§164.460; Code of Virginia, 1960 Replacement Volume, §18.1-173;

Wyoming Code, §6-226.

26

support the proposition that it is synonymous with “tres

pass” or “remaining.” While “enter” in the sense of going

on and taking possession of land is familiar (Ballantine,

“Law Dictionary”, (2d Ed. 1948), 436; “Black’s Law

Dictionary” (4th Ed. 1951), 625), its use to mean “re

maining on land and refusing to leave it when ordered

off” is novel.

Judicial construction often has cured criminal statutes

of the vice of vagueness, but this has been construction

which confines, not expands, statutory language. Compare

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568, with Herndon

v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242.

As construed and applied, the law in question no longer

informs one what is forbidden in fair terms, and no longer

warns against transgression. This failure offends the

standard of fairness expressed by the rule against ex

pansive construction of criminal laws and embodied in the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

III.

The decision below conflicts with decisions of this

Court securing the Fourteenth Amendment right to

freedom of expression.

Petitioners were engaged ip the exercise of free ex

pression by means of verbal requests to the management

and the requests implicit in seating themselves at the

counter for nonsegregated lunch counter service. Their

expression (asking for service) was entirely appropriate

to the time and place in which it occurred. Certainly the

invitation to enter an establishment carries with it the

right to discuss and even argue with the proprietor con

cerning terms and conditions of service so long as no

disorder or obstruction of business occurs.

27

Petitioners did not shout, obstruct business, carry picket

ing signs, give out handbills, or engage in any conduct

inappropriate to the time, place and circumstances. And,

as is fully elaborated above in Part I of this petition, there

was no invasion of privacy involved in this case, since

the lunch counter was an integral part of commercial prop

erty open up to the public.

This Court and other courts on numerous occasions have

held that the right of free speech is not circumscribed by

the mere fact that it occurs on private property. The ex

istence of a property interest is but one circumstance to

be considered among many. In Marsh v. Alabama, supra,

for example, this Court overturned the trespass conviction

of Jehovah’s Witnesses who went upon the premises of a

company town to proselytize holding that such arrest and

conviction violated the Fourteenth Amendment. In Re

public Aviqtion Corp. v. National Labor Relations Board,

324 U. S. 793, the Court upheld the validity of the National

Labor Relations Board’s ruling that lacking special cir

cumstances that might make such rules necessary, employer

regulations forbidding all union solicitation on company

property regardless of whether the workers were on their

own or company time, constituted unfair labor practices.8

8 See also N. L. R. B. v. American Pearl Button Co., 149 F. 2d 258

(8th Cir., 1945) ; United Steelworkers v. N. L. R. B., 243 F. 2d 593,

598 (D. C. Cir., 1956) (reversed on other grounds) 357 U. S. 357.

(“Our attention has not been called to any case under the Wagner

Act or its successor in which it has been held that an employer can

prohibit either solicitation or distribution of literature by em

ployees simply because the premises are company property.

Employees are lawfully within the plant, and nonworking time

is their own time. If Section 7 activities are to be prohibited,

something more than mere ownership and control must be shown.”)

Compare N. L. R. B. v. Pansteel Metal Corp., 306 U.S. 240, 252

(employees seized plant; discharge held valid: “high-handed pro

ceeding without shadow of legal right”).

28

In Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141, this Court held

unconstitutional an ordinance which made unlawful ringing

doorbells of residence for the purpose of distributing hand

bills, upon considering the free speech values involved—

“[djoor to door distribution of circulars is essential to

the poorly financed causes of little people,” at p. 146—

and that the ordinance precluded individual private house

holders from deciding whether they desired to receive the

message. But effecting “an adjustment of constitutional

rights in the light of the particular living conditions of the

time and place”, Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622, 626,

the Court, assessing a conviction for door-to-door commer

cial solicitation of magazines, contrary to a “Green River”

ordinance, concluded that the community “speak[ing] for

the citizens,” 341 IT. S. 644, might convict for crime in the

nature of trespass after balancing the “conveniences be

tween some householders’ desire for privacy and the pub

lisher’s right to distribute publications in the precise way

that those soliciting for him think brings the best results.”

341 U. S. at 644. Because, among other things, “ [subscrip

tion may be made by anyone interested in receiving the

magazines without the annoyances of house to house can

vassing,” ibid., the judgment was affirmed.

Similarly, following an appraisal of the speech and

property considerations involved, a Baltimore City Court,

State of Maryland v. Williams, 44 Lab. Eel. Ref. Man.

2357, 2361 (1959), has on Fourteenth Amendment and

Labor Management Relations Act grounds, decided that

pickets may patrol property within a privately owned shop

ping center. See also People v. Barisi, 193 Misc. 934, 86

N. Y. S. 2d 277, 279 (1948), which held that picketing within

Pennsylvania Station was not trespass; the owners opened

it to the public and their property rights were “circum

scribed by the constitutional rights of those who use it” ;

29

Freeman v, Retail Clerks Union, Washington Superior

Court, 45 Lab. Eel. Ref. Man. 2334 (1959), which denied

relief to a shopping center owner against picketers on his

property, relying on the Fourteenth Amendment.

The liberty secured by the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment insofar as it protects free expression

is not limited to verbal utterances, though petitioners here

expressed themselves by speech. The right comprehends

picketing, Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88; free distri

bution of handbills, Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141;

display of motion pictures, Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S.

495; joining of associations, N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357

U. S. 449; the display of a flag or symbol, Stromberg v.

California, 283 U. S. 359. What has become known as a

“sit in” is a different but obviously well understood symbol,

a meaningful method of communication and protest.

In the circumstances of this case, the only apparent state

interest being preserved was that of maintaining the man

agement’s rights to exclude Negroes from the lunch counter.

The management itself sought nothing more. But as Justice

Holmes held in Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 47, 52,

the question is “whether the words used are used in such

circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear

and present danger that they will bring about the sub

stantive evil” that the state has a right to prevent.

The state has no interest in preserving such discrimina

tion and certainly has no valid interest in suppressing

speech which is entirely appropriate to the time and place

and does not interfere with privacy, when the speech urges

an end to racial discrimination imposed in accordance with

the customs of the community.

30

CONCLUSION

W h e re fo re , f o r th e fo re g o in g rea so n s , i t is re sp e c t

fu lly su b m itte d th a t th e p e ti t io n f o r a w rit o f c e r t io ra r i

sh o u ld be g ra n te d .

Respectfully submitted,

T hurgood M arshall

J ack G r e e n b e r g

J a m es M . N abrit , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

L. C. B erry , J r .

W il l ia m A. M a r sh , J r .

F. B. M cK issic k

C. 0. P earson

W . G. P earson

M . H u g h T h o m pso n

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

E lwood H. C h iso l m

W il l ia m T. C o lem a n , J r.

L ouis H. P ollak

Ch a r les A. R e ic h

S pottswood W . R o b in so n , III

Of Counsel

Opinion by Mr. Justice Mallard

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Fall Term 1960

No. 654—Durham

S tate

.Jo h n T hom as A v e n t

S tate

L acy Carrole S tr eeter

S tate

F r a n k M cG il l C olem an

S tate

—v.—

S h ir l e y M ae B row n

S tate

D onovan P h il l ip s

S tate

C a llis N apolis B row n

S tate

—v.—

J oan H arris N elson

2a

Appeal by defendants from Mallard, J 30 June 1960

Criminal Term of Durham.

Seven criminal actions, based on seven separate indict

ments, which were consolidated and tried together.

The indictment in the case of defendant John Thomas

Avent is as follows: “The Jurors for the State upon their

oath present, That John Thomas Avent, late of the County

of Durham, on the 6th day of May, in the year of our Lord

one thousand nine hundred and sixty, with force and arms,

at and in the county aforesaid, did unlawfully, willfully

and intentionally after being forbidden to do so, enter upon

the land and tenement of S. H. Kress and .Company store

located at 101-103 W. Main Street in Durham, N. C., said

S. H. Kress and Company, owner, being then and there in

actual and peaceable possession of said premises, under

the control of its manager and agent, W. K. Boger, who

had, as agent and manager, the authority to exercise his

control over said premises, and said defendant after being

ordered by said W. K. Boger, agent and manager of said

owner, S. H. Kress and Company, to leave that part of the

said store reserved for employees and invited guests, will

fully and unlawfully refused to do so knowing or having

reason to know that he the said John Thomas Avent,

defendant, had no license therefor, against the form of the

statute in such case made and provided and against the

peace and dignity of the State.”

The other six indictments are identical, except that each

indictment names a different defendant.

The State’s evidence tends to show the following facts:

On 6 May 1960 S. H. Kress and Company was operating

a general variety store on Main Street in the city of Dur

ham. Its manager, W. K. Boger, had complete control and

authority over this store. The store has two selling floors

3a

and three stockroom floors, and is operated to make a

profit. On the first floor the store has a stand-up counter,

where it serves food and drinks to Negroes and White

people. The luncheonette department serving food is in

the rear of the basement on the basement floor. On 6 May

1960 S. H. Kress and Company had iron railings, with

chained entrances, separating the luncheonette department

from other departments in the store, and had signs posted

over that department stating the luncheonette department

was operated for employees and invited guests only. Cus

tomers on that date in the luncheonette department were

invited guests and employees.

On 6 May 1960 these seven defendants, five of whom are

Negroes and two of whom (Joan Harris Nelson and Frank

McGill Coleman) are members of the White race, were in

the store. Before the seven defendants seated themselves

in the luncheonette department, and after they seated them

selves there, W. K. Boger had a conversation with each one

of them. He told them that the luncheonette department

was open for employees and invited guests only, and asked

them not to take seats there. When they seated themselves

there, he asked them to leave. They refused to leave until

after they were served. He called an officer of the city

police department. The officer asked them to leave. They

did not do so, and he arrested them, and charged them with

trespassing. The seven defendants were not employees of

the store. They had no authority or permission to be in the

luncheonette department.

On cross-examination W. K. Boger testified in substance:

S. H. Kress and Company has 50 counters in the store,

and it accepts patronage of Negroes at those 50 counters.

White people are considered guests. Had the two White

defendants come into the store on 4 May 1960, I would not

have served them in the luncheonette department for the

4a

reason they had made every effort to boycott the store.

He would have served the White woman defendant, but he

asked her to leave when she gave her food to a Negro. The

object of operating our store in Durham is definitely to

make a profit. It is the policy of our store to operate all

counters dependent upon the customs of the community. It

is our policy in Durham to refuse to serve Negroes at the

luncheonette department downstairs in our seating arrange

ment. It is also our policy there to refuse to serve White

people in the company of Negroes. We had signs all over

the luncheonette department to the effect that it was open

for employees and invited guests.

Captain Cannady of the Durham Police Department tes

tified in substance: As a result of a call to the department

he went to S. H. Kress and Company’s store. He saw on

6 May 1960 all the defendants, except Coleman, seated at

the counter in the luncheonette department. He heard

W. K. Boger ask each one of them to leave, and all refused.

He asked them to leave, and told them they could either

leave or be arrested for trespassing. They refused to

leave, and he charged them with trespassing. He knew

W. K. Boger was manager of the store. He makes an

arrest when an offense is committed in his presence, and

the defendants were trespassing in his presence.

When the State rested its case, all seven defendants tes

tified. The five Negro defendants testified in substance:

All are students at North Carolina College for Negroes in

Durham. Prior to 6 May 1960, Negroes, including some

of the Negro defendants, had been refused service by S. H.

Kress and Company in its luncheonette department. All

are members of a student organization, which met on the

night of 5 May 1960, and planned to go the following day

to Kress’ store, make a purchase, and then to go to the

luncheonette department, take seats, and request service.

5a

The following day the five Negro defendants did what they

planned.

The White woman defendant, Joan Harris Nelson, is a

student at Duke University. Prior to 6 May 1960 she had

not attended the meetings at the North Carolina College

for Negroes for the purpose of securing service at the

luncheonette department of the Kress store, though she

has attended some of the meetings since then. She had

been on the picket lines in front of the store. On 6 May

1960 she went into the Kress store, bought a bail-point pen,

went to the luncheonette department, and took a seat. She

was served, and while eating she offered to buy some food

for Negroes from the North Carolina College, who were

sitting on each side of her. When she was served food,

no Negroes were in the luncheonette department. Mr.

W. K. Boger asked her to leave because she was not in

vited, and was antagonizing customers. She did not leave,

and was arrested.

The White male defendant, Prank McGill Coleman, is a

student at Duke University. On 6 May 1960 he went into

the Kress store, bought a mother’s day card, joined his

friend, Bob Markham, a Negro, and they went to the lunch

eonette department, and seated themselves. He asked for

service, and was refused. Mr. W. K. Boger asked them to

leave, telling them they were not invited guests, and he

refused to do so, and was arrested. Prior to this date he

had carried signs in front of the Kress store and other

stores discouraging people to trade with them.

Some, if not all, of the defendants had been engaged

previously in picketing the Kress store, and in urging a

boycott of it, unless their demands for service in the lunch

eonette department were acceded to.

Jury Verdict: All the defendants, and each one of them,

are guilty as charged.

6a

From judgments against each defendant, each defendant

appeals.

T. W. B ruton, Attorney General, and R a l p h

M oody, Assistant Attorney General, for the

State.

W il l ia m A. M a r sh , J r., M . H u g h T h o m p s o n ,

C. 0. P earson , W. G. P earson , F. B . Mc-

K is s ic k and L. C. B erry , J r., for Defen

dants-Appellants.

Parker, J. Each defendant—five of whom are Negroes

and two members of the White race—before pleading to

the indictment against him or her made a motion to quash

the indictment. The court overruled each motion, and each

defendant excepted. The motions were made in apt time.

S. v. Perry, 248 N. C. 334, 103 S. E. 2d 404; Carter v Texas,

177 IT. S. 442, 44 L. Ed. 839; 27 Am. Jur., Indictments and

Information, §141.

At the close of all the evidence each defendant made a

motion for judgment of compulsory nonsuit. Each motion

was overruled, and each defendant excepted.

S. H. Kress and Company is a privately owned corpora

tion, and in the conduct of its store in Durham is acting

in a purely private capacity to make a profit for its share

holders. There is nothing in the evidence before us, or in

the briefs of counsel to suggest that the store building in

which it operates is not privately owned. In its basement

in the luncheonette department it operates a restaurant.

“While the word ‘ restaurant’ has no strictly defined mean

ing, it seems to be used indiscriminately as a name for all

places where refreshments can be had, from a mere eating-

house and cook-shop, to any other place where eatables

are furnished to be consumed on the premises. Citing

authority. It has been defined as a place to which a person

7a

resorts for the temporary purpose of obtaining a meal or

something to eat.” S. v. Shoaf, 179 N. C. 744. 102 S. E. 705.

To the same effect see, 29 Am, Jur., (1960), Innkeepers,

§9, p. 12. In Richards v. Washington F. $ M. Ins. Co., 60

Mich. 420, 27 N. W. 586, the Court said: “A ‘restaurant’

has no more defined meaning, (than the English word

shop), and is used indiscriminately for all places where

refreshments can be had, from the mere eating-house or

cookshop to the more common shops or stores, where the

chief business is vending articles of consumption and con

fectionery, and the furnishing of eatables to be consumed

on the premises is subordinate.” Quoted with approval in

Michigan Packing Co. v. Messaris, 257 Mich. 422, 241 N. W.

236, and restated in substance in 43 C. J. S., Innkeepers,

§1, subsection b, p. 1132.

No statute of North Carolina requires the exclusion of

Negroes and of White people in company with Negroes

from restaurants, and no statute in this State forbids

discrimination by the owner of a restaurant of people on

account of race or color, or of White people in company

with Negroes. In the absence of a statute forbidding dis

crimination based on race or color in restaurants, the rule

is well established that an operator of a privately owned

restaurant privately operated in a privately owned build

ing has the right to select the clientele he will serve, and

to make such selection based on color, race, or White

people in company with Negroes or vice versa, if he so

desires. He is not an innkeeper. This is the common law.

8. v. Clyhurn, 247 N. C. 455, 101 S. E. 2d 295; Williams v.

Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d 845; Slack v.

Atlantic White Tower System, Inc., 181 F. Supp. 124, af

firmed by the U. S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit

27 December 1960,-----F. 2d------ ; Alpaugh v. Wolverton,

184 Va. 943, 36 S. E. 2d 906; Wilmington Parking Author

ity v. Burton (Del.), 157 A. 2d 894; Nance v. Mayflower

8a

Restaurant, 106 Utah 517, 150 P. 2d 773. See 10 Am. Jur.,

Civil Rights, §21; Powell v. Uts, 87 F. Supp. 811; and An

notation 9 Am. & Eng. Ann. Cas. 69—statutes securing

equal rights in places of public accommodation. We have

found no case to the contrary after diligent search, and

counsel for defendants have referred us to none.

In Alpaugh v. Wolverton, supra, the Court said: “The

proprietor of a restaurant is not subject to the same duties

and responsibilities as those of an innkeeper, nor is he

entitled to the privileges of the latter. Citing authority.

His rights and responsibilities are more like those of a

shopkeeper. Citing authority. He is under no common-law