Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Brief of Respondents

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1947

25 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Brief of Respondents, 1947. a4c6139d-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/59f613eb-3d4e-41c5-876b-1cc33c8fe3a9/sipuel-v-board-of-regents-of-uok-brief-of-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

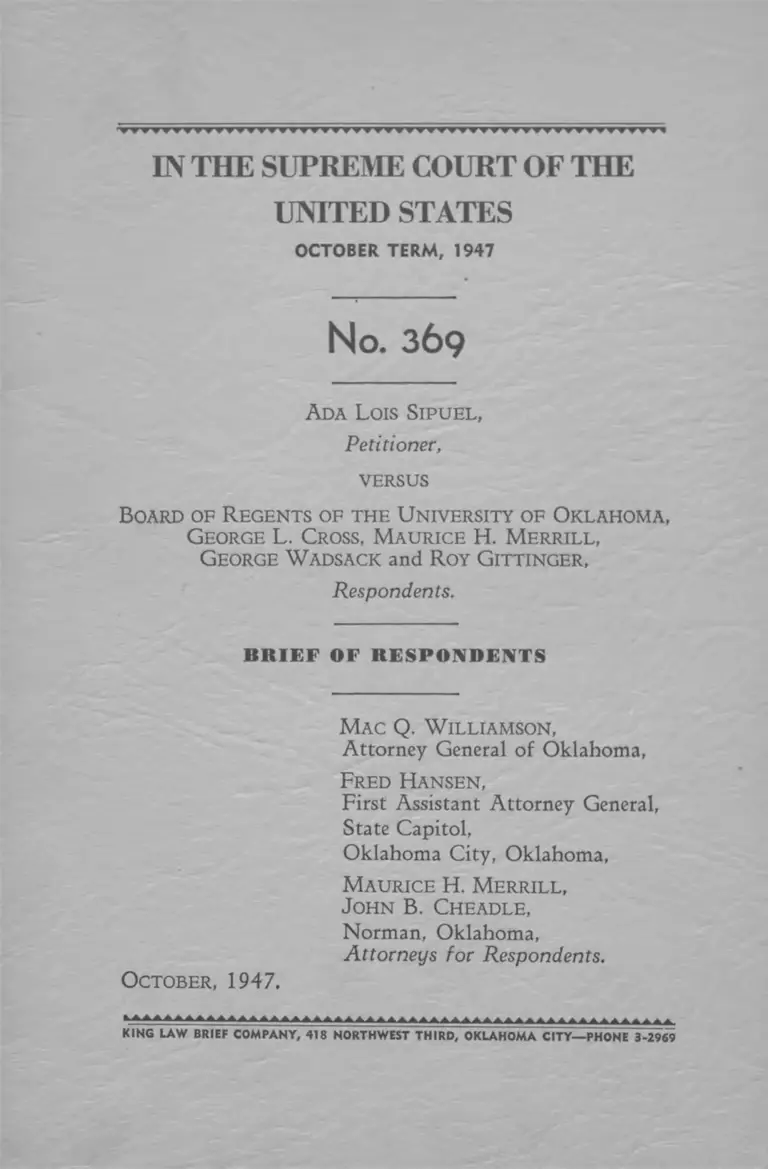

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 369

Ada Lois Sipuel ,

Petitioner,

VERSUS

Board of Regents of the U niversity of Oklahoma,

George L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill,

George W adsack and Roy Gittinger,

Respondents.

B R I E F OF R E S P O N D E N T S

Mac Q. W illiamson,

Attorney General of Oklahoma,

Fred Hansen ,

First Assistant Attorney General,

State Capitol,

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma,

Maurice H. Merrill,

John B. Cheadle,

Norman, Oklahoma,

Attorneys for Respondents.

October, 1947.

K IN G LAW BRIEF C O M PAN Y, 418 NORTHW EST TH IRD , O K LA H O M A C IT Y — PHONE 3-2969

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case------------------------------------- 1

Argum ent__________________________________ 3

Authority:—

Payne, Co. Treas. et al. v. Smith, Judge,

107 Okla. 165, 231 Pac. 469 _____________ 3

Stone v. Miracle, Judge, 196 Okla. 42,

162 Pac. (2d) 534 ______________________ 3

12 O.S. 1941, Section 1451-------------------------- 3

First Proposition: The decision of the Supreme Court

of Oklahoma appealed from herein accords full

recognition to the asserted constitutional right of

the petitioner to have provision made for her legal

education within the State and establishes that the

State of Oklahoma has provided the institutional

basis on which the petitioner may secure such edu

cation.

(a) The decision of the Supreme Court of

Oklahoma fully accepts the proposition that the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment requires a state which provides edu

cation in law to white students at an institution

within its borders to likewise provide such edu

cation within the state to students belonging to

other races, and that this right is available to

any applicant of one of said other races who in

dicates an intention to accept such training.___ 5

Authority:—

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U.S. 337 __________________________6, 11

(b) The decision of the Supreme Court of

Oklahoma establishes that the law thereof vests

PAGE

in the petitioner a right to education in law

within the State, at a public educational institu

tion of higher education, on a basis of equality

with white students admitted to law courses at

the University of Oklahoma._______________ 6

Authority:—

Allen-Bradley Local v. Wisconsin etc. Board,

315 U.S. 740 ___________________________ 10

American Power & Light Co. v. Sec. S3 Exch.

Comm., 329 U.S. 9 0 ____________________ 10

A. T. S3 S. F. Ry. Co. v. R. R. Comm, of Cal.,

283 U.S. 380 ___________________________ 10

Board of Regents v. Childers, State Auditor,

197 Okla. 350, 170 Pac.(2d) 1018________ 8

Douglas v. N.Y., N.H. etc. Ry. Co., 279 U.S. 377 10

Ex parte Tindall, 102 Okla. 192, 229 Pac. 125_9

In re: Assessment of K. C. S. Ry. Co.,

168 Okla. 495, 33 Pac. (2d) 772 __________ 9

Overton v. State, 7 Okla. Cr. 203, 114 Pac. 1132 9

Quong Ham Wah Co. v. Ind. Acc. Comm.,

235 U.S. 445 __________________________ 11

Senn v. Tile Layers etc., 301 U.S. 468 ________ 10

State ex rel. Bluford v. Canada, 348 Mo. 298,

153 S.W. (2d) 1 2 _______________________ 9

Tampa Water Works Co. v. Tampa,

199 U.S. 2 4 1 __________________________ 10

U. S. v. Texas, 314 U.S. 480 ________________ 10

Article 1, Section 1, Oklahoma Constitution____ 8

Article 13, Section 3, Oklahoma Constitution___ 7

Article 13-A, Section 2, Oklahoma Constitution 8

Article 15, Section 1, Oklahoma Constitution___ 8

70 O.S. 1941, Sections 455, 456, 457 ________ 7

70 O.S. 1941, Section 1451_________________ 7

(c) The Oklahoma law, thus interpreted, ac

cords with the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, as interpreted by this

C ourt._________________________________ 2 |

11

PAGE

Authority:—

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 4 5 ----------- 11

Bluford v. Canada, 32 Fed. Supp. 707 ------------ 15

Cumming v. County Board etc., 175 U.S. 528---- 11

Gilchrist v. Interborough etc. Co., 279 U.S. 159 15

Long Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 7 8 --------------------- 11

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U.S. 337 _________________12, 13, 14, 15

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 -------------------- 11

State ex rel. Bluford v. Canada, 348 Mo. 298,

153 S.W.(2d) 1 2 _______________________ 15

State ex rel. Michael v. Witham, 179 Tenn. 250,

165 S.W.(2d) 378 ______________________ 15

Second Proposition: The petitioner has failed to seek

relief from or against the officials who may provide

it under the law of Oklahoma._______________ 16

Authority:—

Copperweld Steel Co. v. Ind. Comm.,

324 U.S. 780 ___________________________ 16

Lawrence v. S. L. & S. F. Ry. Co., 274 U.S. 588 17

Prentis v. Atlantic etc. Co., 211 U.S. 2 1 0 --------- 17

S. L. & S. F. Ry. Co. v. Alabama etc. Comm.,

270 U.S. 560 ___________________________ 17

Conclusion_________________________________ 19

I l l

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 369

Ada Lois Sipuel ,

Petitioner,

VERSUS

Board of Regents of the U niversity of Oklahoma,

George L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill,

George W adsack and Roy Gittinger,

Respondents.

B R I E F OF R E S P O N D E N T S

STATEM ENT OF THE CASE

The “Statement of the Case” set forth on Page 8 of

f

petitioner’s brief, in which is incorporated by reference her

petition for writ of certiorari, is substantially correct with

the exception that respondents did not, as stated in said

2 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

petition (R. 2 and 3), refuse petitioner admission to the

Law School of the University of Oklahoma on the ground:

“ (2) That scholarship aid was offered by the State

to Negroes to study law outside the State, * * *.”

While certain allegations of fact set forth in said state

ment and incorporated petition are not, in all respects,

accurate, and certain conclusions of law set forth therein

not, in our opinion, sound, respondents will fully clarify

their position in relation to said allegations and conclusions

in our “Argument” herein.

However, before concluding this “Statement of the

Case,” respondents desire to call attention to the “Order

Correcting Opinion—June 5, 1947,” which appears on

Pages 51 and 52 of the record, and to the fact that said

correction was not made in the pertinent language of the

decision of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma, which opin

ion appears on Pages 35 to 51 of the record. In this con

nection it will be noted that said correction should have

been made in the first line of the fourth paragraph of said

opinion, which paragraph appears on Page 41 of the record,

so that said line would read:

As we view the matter the State itself could not

place complete * * *

By an examination of said decision, as it appears in

180 Pac. (2d) 135-138, it will be noted that said correc

tion was likewise not made therein.

Brief of Respondents 3

ARG U M EN T

There is but one real issue involved in this case and

that is whether or not the trial court, that is, the District

Court of Cleveland County, Oklahoma, erred in declining

to issue a writ of mandamus, as prayed for by petitioner,

to require the respondents, Board of Regents of the Univer

sity of Oklahoma, George L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill,

George Wadsack and Roy Gittinger, to admit the petitioner,

Ada Lois Sipuel, to the School of Law of the University

of Oklahoma.

Before discussing the above issue respondents deem it

advisable to call attention to 12 O.S. 1941, Sec. 1451,

relating to the right of issuance of a writ of mandamus

in Oklahoma, the material part of which is as follows:

“The writ of mandamus may be issued by the Su

preme Court or the district court, or any justice or

judge thereof, during term, or at chambers, to any in

ferior tribunal, corporation, board or person, to compel

the performance of any act which the law specially

enjoins as a duty, resulting from an office, trust or

station; * * *.”

The Oklahoma Supreme Court, in construing the

above language, held in the second paragraph of the sylla

bus of Payne, County Treasurer et al. V. Smith, Judge,

107 Okla. 165, 231 Pac. 469, as follows:

“To sustain a petition for mandamus petitioner

must show a legal right to have the act done sought

by the writ, and also that it is plain legal duty of the

defendant to perform the act.’’

In the case of Stone V. Miracle, Dist. Judge, 196 Okla.

42, 162 Pac. (2d) 534, the syllabus is as follows:

4 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

“Mandamus is a writ awarded to correct an abuse

of power or an unlawful exercise thereof by an inferior

court, officer, tribunal or board by which a litigant is

denied a clear legal right, especially where the remedy

by appeal is inadequate or would result in inexcusable

delay in the enforcement of a clear legal right.”

In the case at Bar petitioner evidently recognized the

principles of law announced in the above decision. In this

connection it will be noted that petitioner, as a basis for

this action in mandamus, alleged in her petition (R. 2 to 6)

that although she was duly qualified to attend the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma when she, on Jan

uary 14, 1946, “duly applied for admission to the first

year class” of said school for the term beginning January

15, 1946, she was by respondents:

“* * * arbitrarily refused admission” (Para. 1 of

petitioner’s pet.).

“* * * arbitrarily and illegally rejected” (Para. 2

of petitioner’s pet.).

And that said refusal or rejection was:

“* * * arbitrary and illegal” (Para. 5 of petitioner’s

pet.).

Therefore, the real issue involved in this case is whether

or not respondents, on January 14, 1946, arbitrarily and

illegally rejected the application of petitioner for admission

to the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma.

Said issue is summarized herein as follows:

Mandamus will not lie to require respondents to

violate the public policy and criminal statutes of Okla

homa by directing respondents to admit petitioner,

a colored person, to the School of Law of the Univer

Brief of Respondents 5

sity of Oklahoma, same being attended only by white

persons, since petitioner has not:

(1) Applied, directly or indirectly to the Okla

homa State Regents for Higher Education for them,

under authority of Article 13-A of the Constitution

of Oklahoma, to prescribe a school of law equal or

“substantially equal” to that of the University of

Oklahoma as a, part of the “standards of higher

education” and/or “functions and courses of study”

of Langston University, same being a State institu

tion of higher education attended only by colored

persons, or

(2) Indicated, directly or indirectly, to said State

regents or to the governing board of Langston Uni

versity, that she would attend such a school in the

event it was established.

Respondents will present their argument in support

of the above summarized issue under the following propo

sitions.

FIRST PROPOSITION

THE DECISION OF THE SUPREME COURT OF

O K LA H O M A APPEALED FROM HEREIN ACCORDS

FULL RECOGNITION TO THE ASSERTED C O N ST I

TU T IO N A L RIGHT OF THE PETITIONER TO HAVE

PROVISION M ADE FOR HER LEGAL EDUCATION

W IT H IN THE STATE A N D ESTABLISHES TH AT THE

STATE OF O KLA H O M A HAS PROVIDED THE IN ST I

TU T IO N A L BASIS ON W H IC H THE PETITIONER M A Y

SECURE SUCH EDUCATION.

(a) The decision of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma

fully accepts the proposition that the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment requires a state

which provides education in law to white students ot

at institution within its borders to likewise provide

such education within the state to students belonging

to ether races, end that this right is available to any

6 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

applicant of one of said other races who indicates an

intention to accept such training.

The decision of the Oklahoma Supreme Court, as

above outlined, is in accord with the basis upon which the

decision in Missouri ex tel. Gaines V. Canada, 305 U.S.

337, rests. The decision of the Supreme Court of Okla

homa recognizes this fully and repeatedly. “That it is the

State’s duty to furnish equal facilities to the races goes

without saying” (R. 38). “Negro citizens have an equal

right to receive their law school training within the State

if they prefer it” (R. 42). Said court expressly stated

that it is the duty of the proper state authorities, upon

proper notice or information “to provide for her [peti

tioner] an opportunity for education in law at Langston

or elsewhere in Oklahoma” (R. 45). “The reasoning and

spirit of that decision [the Gaines case], of course, is appli

cable here, that is, that the State must provide either a

proper legal training for petitioner in the State, or admit

petitioner to the University Law School” (R. 47). The

opinion specifically holds that “petitioner is fully entitled

to education in law with facilities equal to those for white

students, * *

(b) The decision of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma

establishes that the law thereof vests in the petitioner

a right to education in law within the State, at a pub

lic educational institution of higher education, on a

basis of equality with white students admitted to law

courses at the University of Oklahoma.

It is expressly stated in said decision that “the State

Regents for Higher Education has undoubted authority

Brief of Respondents 7

to institute a law school for Negroes at Langston. It would

be the duty of that board to so act, not only upon formal

demand, but on any definite information that a member

of that race was available for such instruction and desired

the same” (R. 42). Said duty is summed up in the con

cluding portion of the' opinion in the statement ‘‘we are

convinced that it is the mandatory duty of the State Regents

for Higher Education to provide equal educational facilities

for the races to the full extent that the same is necessary

for the patronage thereof. That board has full power,

and as we construe the law, the mandatory duty to provide

a separate law school for Negroes upon demand or sub

stantial notice as to patronage therefor” (R. 50).

This determination rests upon a substantial basis (as

is shown by Paragraphs 1 to 5, below), in the constitu

tional and statutory law of Oklahoma:

1. The constitution and laws of said State pre

scribe the policy of segregated education of the white

and the colored races, but with equal facilities, from

the common schools, Oklahoma Constitution, Article

13, Section 3 (R. 16, Par. 14), on through the col

leges and other institutions, 70 O.S. 1941, Sections

455, 456 and 457 (printed in full in the appendix

to petitioner’s brief, P. 21).

2. In pursuance of this policy, the State has estab

lished, among other institutions of higher education,

the University of Oklahoma, to which white students

are admitted. Likewise the State has established Lang-

ton University, to which colored students are admitted.

70 O.S. 1941, Section 1451 (plaintiff’s appendix,

P. 21).

3. The Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Edu

cation is established as “a co-ordinating board of con-

8 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

trol” for all institutions of higher education. As such,

it is empowered and directed to “prescribe standards

of higher education applicable to each institution,” to

“determine the functions and courses of study in each

of the institutions to conform to the standards pre

scribed,” and to “recommend to the State Legislature

the budget allocations to each institution.” Okla

homa Constitution, Article 13-A, Section 2 (printed

in full in appendix to petitioner’s brief, P. 20). This

last function of recommending budget allocations is

merely for the information of the Legislature, since

Section 3 of said article is as follows:

“The appropriations made by the Legislature for

all such institutions shall be made in consolidated

form without reference to any particular institution

and the Board of Regents herein created shall allo

cate to each institution according to its needs and

functions”

The mandatory character of this constitutional pro

vision was given effect by the Supreme Court of Okla

homa in the case of Board of Regents V. Childers, State

Auditor (July 9, 1946), 197 Okla. 350, 170 Pac.

(2d) 1018, approximately one year prior to its de

cision in the case at Bar. From these constitutional

provisions it is clear that the State Regents for Higher

Education, and not the governing board of each edu

cational institution, have the power to prescribe the

functions and courses of study of each institution, and

that said State Regents have under their control all the

financial resources which the State has appropriated for

higher education. Hence, it is clear that the State

Regents have full power to provide a legal education

for the petitioner within the State and to prescribe the

institution at which it shall be given, and that no other

authority of the State possesses such power.

4. The Constitution of Oklahoma, Article 1, Sec

tion 1, provides that “the State of Oklahoma is an

inseparable part of the Federal Union, and the Con

stitution of the United States is the supreme law of

the land.” The same constitution, in Article 15, Sec-

Brief of Respondents 9

tion 1, prescribes an official oath to be taken by all

State officers, including, of course, the State Regents

for Higher Education, that they will “support, obey

and defend the Constitution of the United States, and

the Constitution of the State of Oklahoma.” It is the

established practice of the courts of Oklahoma to con

strue grants of power in such a way as to comply with

constitutional requirements. Ex parte Tindall, 102

Okla. 192, 200, 229 Pac. 125, 132; In re: Assess

ment of Kansas City Southern Railway Company,

168 Okla. 495, 33 Pac. (2d) 772. “The statutes of

Oklahoma are construed in connection with and in

subordination to the Constitution of the United States

* * *.” Overton v. State, 7 Okla. Cr. 203, 205, 114

Pac. 1132.

5. Fitting these constitutional and statutory pro

visions and established practice together, recognizing

the unquestionable fact that the State Regents for

Higher Education can give effect to the State’s policy

of segregation, consistently with obedience to the Con

stitution of the United States, only by providing edu

cation in law within the State to such Negroes as re

quested it, so long as such instruction is afforded to

whites, it is neither a “strange construction” (Pet. B.

16), a “stretch of the imagination” (Pet. B. 17) nor

“sophistical and circuitous reasoning” (Pet. B. 18),

for the Oklahoma Supreme Court to hold that the

State Regents are under a mandatory duty to provide

for that training, consistently with the policy of segre

gated education, whenever it is clear that there are

Negroes who are willing to receive it. It is merely

compliance with the command of the State’s highest

law that the Constitution of the United States shall

be obeyed. It is adherence to the sound doctrine ex

pressed by the Supreme Court of Missouri in State

ex rel. Bluford V. Canada (1941), 348 Mo. 298 309

153 S.W. (2d) 12, 17:

“It is the duty of this court to maintain Mis

souri s policy of segregation so long as it does not

come in conflict with the Federal Constitution. It

10 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

is also our duty to follow the interpretation placed

on the Federal Constitution by the Supreme Court

of the United States.”

It is but giving effect to the principle enunciated by

this Court in American Power and Light Company V.

Securities and Exchange Commission, 329 U.S. 90:

‘‘Wherever possible statutes must be interpreted

in accordance with constitutional provisions.”

Counsel for the petitioner are hardly in a position to

criticize a statement of the law with which they con

curred, when they said in their brief in the Supreme

Court of Oklahoma:

‘‘The Constitution and laws of the United States

and State of Oklahoma require that equal facilities

be afforded all citizens of the State. The duty of

making such equal provisions was delegated to the

Board of Regents of Higher Education. This duty

is incumbent upon the Board by virtue of their

office” (R. 49, 50).

This reasonable and tenable declaration of the law

of Oklahoma, by its highest court, will be accepted

by this Court as an authoritative definition of the

mandatory duty of the State Regents for Higher Edu

cation under the State law. Tampa Water Works

Company V. Tampa, 199 U.S. 241, 244; Douglas V.

New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad Com

pany, 279 U.S. 377, 386; Atchison, Topeka and

Santa Fe Railroad Company V. Rail Commission of

California, 283 U.S. 380, 390; Senn V. Tile Layers

Protective Union, 301 U.S. 468, 477; United States

V. Texas, 314 U.S. 480, 487; Allen-Bradley Local V.

Wisconsin Employment Relations Board, 315 U.S.

740, 746. This Court will not accept an argument

which “but disputes the correctness of the construc

tion affixed by the court below to the State statute

and assumes that that construction is here susceptible

of being disregarded upon the theory of the existence

of the discrimination contended for when, if the mean

ing affixed to the statute by the court below be ac-

Brief of Respondents 11

copied, every basis for such contended discrimination

disappears.” Quong Ham Wah Co. V. Industrial

Accident Commission, 235 U.S. 445, 449.

(c) The Oklahoma law, thus interpreted, accords

with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, as interpreted by this Court.

The decisions of this Court consistently have recog

nized the validity of racial segregation in education under

the Fourteenth Amendment, provided that all races are

accorded equal, or substantially equal, facilities. Plessy V.

Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 544; Gumming V. County Board

of Education of Richmond County, 175 U.S. 528; Berea

College V. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45, 55; Long Lum V. Rice,

275 U.S. 78.

In Missouri ex rel. Gaines V. Canada, 305 U.S. 337,

344, this Court reaffirmed this principle, stating it as “the

obligation of the state to provide Negroes with advantages

for higher education substantially equal to the advantages

afforded to white students,” and that the fulfillment of

said obligation, ‘‘by furnishing equal facilities in separate

schools, * * * has been sustained by our decisions.” The

petitioner’s counsel accept this view repeatedly in their brief

(Pp. 8, 10, 13), and take their stand upon the proposition

that ‘‘The decision of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma is

inconsistent with and directly contrary to the decision of

this Court in Gaines V. Canada” (Pet. B. 8). But the

distinctions between the legal and factual situation pre

sented in the Gaines case and that presented in this case

are significant and controlling under the very doctrine to

which the petitioner appeals.

12 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

Said distinctions, as will hereinafter be shown, have

been accurately apprehended and correctly applied by the

Supreme Court of Oklahoma.

1. The basic ground of the decision in the Gaines

case is stated thus by Mr. Chief Justice Hughes:

“By the operation of the laws of Missouri a privi

lege has been created for white law students which

is denied to Negroes by reason of their race. The

white resident is afforded legal education within

the State; the Negro resident having the same quali

fications is refused it there and must go outside the

State to obtain it” 305 U.S. at 349.

2. Subsidiary to this main proposition, the opin

ion in the Gaines case points out that under the de

cision of the Missouri court the curators of the Lincoln

University were not under a duty to provide the peti

tioner therein with training in law, but merely had an

option to do so or to remit him to the procuring of

a legal education outside Missouri at state expense.

305 U.S. at 346 and 347. The decision herein of

the Supreme Court of Oklahoma expressly declares

(R. 42) that:

“The State Regents for Higher Education has

undoubted authority to institute a law school for

Negroes at Langston. It would be the duty of that

board to so act, not only upon formal demand, but

on any definite information that a member of that

race was available for such instruction and desired

the same.”

3. Inasmuch as the first decision of the Supreme

Court of Missouri in the Gaines case maintained that

the constitutional rights of the petitioner therein were

provided for adequately by the opportunity to have

his tuition paid in an out-of-state law school, this

Court declared that:

“We must regard the question whether the pro

vision for the legal education in other states of Neg

roes resident in Missouri is sufficient to satisfy the

Brief of Respondents 13

constitutional requirement of equal protection, as

the pivot upon which this case turns” 305 U.S.

at 348.

The decision of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma

expressly recognizes that the provision in the Okla

homa law for the payment of tuition in out-of-state

schools “does not necessarily discharge the State's duty

to its Negro citizen” (R. 42).

4. In the Gaines case, the decision did not rest upon

the point that no law school presently existed for

Negroes, but upon the ground that the discrimination

arising from its absence “may nevertheless continue for

an indefinite period by reason of the discretion given

to the curators of Lincoln University and the alterna

tive of arranging for tuition in’ other states, as per

mitted by the state law as construed by the state court,

so long as the curators find it unnecessary and impratic-

able to provide facilities for the legal instruction of

Negroes within the state.” This Court continued “In

that view, we cannot regard the discrimination as ex

cused by what is called its temporary character” 305

U.S. at 351, 352. This language implies that a state

is not required to maintain in its institution for Neg

roes a duplication of all departments existing in its

institution for whites, regardless of whether students

present themselves for training therein.

The decision of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma

specifically points out that “authority already exists”

(R. 44) for the establishment of a separate law school

within the State, and that, contrary to the situation in

the Gaines case, ‘‘it is the mandatory duty” of the State

Regents for Higher Education “to provide a separate

hw school for Negroes upon demand or substantial

notice as to patronage therefor” (R. 50). Hence, the

possibility of indefinite continuance of discrimination,

upon which the Gaines decision turned, does not exist

in Oklahoma.

5. The petitioner’s counsel make much of an alleged

misconception by the Supreme Court of Oklahoma

14 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

that the petitioner in the Gaines case had unsuccessfully

demanded from Lincoln University an education in

law. This alleged misconception vanishes if the opin

ion of the Oklahoma court is read with attention. The

opinion in the Gaines case (305 U.S. 342) states that

the petitioner, on applying for admission to the Uni

versity of Missouri, was advised:

“To communicate with the president of Lincoln

University and the latter directed petitioner’s atten-

. • t ition

to the Missouri statute providing for the payment of

tuition in out-of-state schools.

From this it is evident that the petitioner in the

Gaines case did communicate with the Lincoln Univer

sity authorities and that this communication must have

revealed his desire for training in law at the hands of

the Missouri authorities. The Supreme Court of Okla

homa, recognizing that said opinion did not reveal the

exact nature of the communication to Lincoln Univer

sity, stated that “we assume he applied to Lincoln

University for instruction there in the law” (R. 45),

but its stress upon the effect of this communication

was that after it “the authorities in charge of the school

for higher education of Negroes [in Missouri] had

specific notice that petitioner, Gaines, was prepared and

available and therefore there existed a need and at least

one patron for a law school for Negroes” (R. 46).

So treated, there is clearly no misconception.

The Oklahoma court found, with support in the

record, that the petitioner in this case had not brought

home to the proper state authorities a desire for, and

willingness to accept, legal education in a separate

school in accordance with State policy. When it was

suggested that this conduct justified the inference that

a law course in a separate school would not be accept

able to her, no disclaimer was made on her behalf

(R. 39). The Oklahoma court was thus justified in

finding that neither by express demand nor conduct

had the petitioner brought home to the proper authori

ties her availability as a student in a separate law school

Brief of Respondents 15

for Negroes. In the absence thereof, said Court held

that the failure to maintain a school of law for Neg

roes, in readiness for some possible future Negro appli

cant, was not a violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Until a reasonable notice is given that a Negro

student desires local instruction and will accept it on

the terms which the State constitutionally may pre

scribe, there is no need for the State to maintain un

used facilities. This rule finds support in numerous

well-reasoned authorities. Bluford V. Canada, 32 Fed.

Supp. 707; State ex rel. Bluford V. Canada, 348 Mo.

298, 153 S.W. (2d) 12; State ex rel. Michael V. Wit-

ham, 179 Tenn. 250, 165 S.W. (2d) 378.

6. The petitioner’s counsel make much of the agreed

stipulation of fact concerning the special facilities for

training in the Oklahoma law and procedure afforded

by the University of Oklahoma School of Law (Pet.

B. 19). This stipulation covers matters which this

Court in the Gaines case held to be “beside the point”

305 U.S. at 349. These special advantages can be fur

nished petitioner as well in a separate school for Neg

roes as in the University of Oklahoma, if she will but

indicate effectively to the proper authorities her will

ingness to accept training therein.

7. The petitioner’s counsel calls attention to a stipu

lation concerning the action of the State Regents for

Higher Education subsequent to the filing of this ac

tion (Pet. B. 12, 13). The opinion of the Supreme

Court of Oklahoma adequately demonstrates the im

materiality of this (R. 50), and, since counsel makes

no effort to rebut the same in their brief, we assume

that they do not make any point of it in this Court.

Compare Gilchrist V. Interborough Rapid Transit

Company, 279 U.S. 159, 208.

16 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

SECOND PROPOSITION

THE PETITIONER HAS FAILED TO SEEK RELIEF

FROM OR A G A IN ST THE OFFICIALS W H O M A Y PRO

V IDE IT UNDER THE LAW OF OKLAHOMA.

As the analysis herein of the local law already has

demonstrated, the State Regents for Higher Education have

full control over the functions, the courses of study and

the budgets of the several Oklahoma institutions of higher

education. The Board of Regents of the University of

Oklahoma and its administrative authorities have no power

to alter its functions from those of an institution for the

education of white students to those of an institution for

the education of white and colored students. The authority

to prescribe functions rests in the State Regents. They

have complete control over the purse strings of the State’s

higher educational institutions. It is they who must make

the decision whether the resources available will enable them

to provide separate education in law for the two races in

accordance with the State’s policy, and what budgetary

adjustments must be made for that purpose. If they find

this to be impossible, they might elect to comply with the

Constitution of the United States by discontinuing all

State provision for instruction in law, or by opening up

the single State law school to students of all races. Hence,

it is they, and not the authorities of the University of Okla

homa, from whom and against whom the petitioner should

seek relief. This case, therefore, comes under the rule enun

ciated and applied in Copperweld Steel Company V. Indus

Brief of Respondents 17

trial Commission of Ohio, 324 U.S. 780, 785, wherein this

Court held:

“The question of the propriety of taking the appeal

need not be decided, in the view we take of the basis

of the state court’s judgment. Inasmuch as we con

clude that decision was grounded upon the view that

the appellant had not pursued the remedy afforded by

State law for the vindication of any constitutional

right it claimed was violated, we must dismiss the ap

peal and deny certiorari.”

See also, as to the need for pursuing State administrative

remedies before resorting to judicial action, Prentis V. At-

lantic Coast Line Company, 211 U.S. 210, 230; Lawrence

V. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Company, 274 U.S.

588, 592; St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Company V.

Alabama Public Service Commission, 270 U.S. 560, 563.

The decision of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma ex

pressly holds and determines:

(1) That the petitioner, a Negro, is entitled to edu

cation in law within the State so long as the State

maintains facilities for such education available to

white students;

(2) That such education must be furnished on a

basis of equality of facilities, but, under the established

law and policy of the State, in a separate institution;

(3) That only the State Regents for Higher Edu

cation have the authority to provide such education,

since they constitute the only official body of the State

having authority to prescribe the standards and the

functions and courses of study of the several State in

stitutions of higher education;

18 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

(4) That the duty of the State Regents to provide

the petitioner with legal training on a basis of equality

with that afforded to white students is mandatory and

not discretionary;

(5) That this duty attaches whenever, either by

formal demand or through information arising in some

other way, the State Regents properly are chargeable

with notice that a Negro student desires the provision

of training in law at a separate law school;

(6) That the State Regents are the only State offi

cers that have at their command the State’s revenue

provided for purposes of higher education.

On the basis of this analysis of the pertinent law, the

petitioner’s road to secure a legal education within Okla

homa, if she is willing to accept the State’s valid policy of

segregated education, is clear. If she applies to the State

Regents for Higher Education to provide her facilities for

a legal education, it is inconceivable that, with the instant

opinion of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma before them,

they will refuse to do so. Should they, the remedy through

judicial recourse is clear.

The petitioner could have set this machinery in mo

tion on April 29, 1947, when the opinion of the Supreme

Court of Oklahoma was filed. The constitutional and

statutory provisions upon which the decision rests were in

existence at all times, and certainly her attention was called

to the respondent’s contention respecting their interpreta

tion as early as the filing of respondents’ answer in the

District Court of Cleveland County, Oklahoma, on May

14, 1946. Thus, at any time since then, she might have

Brief of Respondents 19

evinced her willingness and desire to accept an education

in law furnished according to the valid policy of the State.

Instead, she insisted at all times, and still insists, on her

alleged right to attend the Law School of the University

of Oklahoma regardless of that policy.

Her disregard of the State Regents for Higher Educa

tion, as aforesaid, and her failure to make them parties to

this action, combine to indicate that her interest was in

breaking down the State’s policy of segregated education,

not in securing provision for legal training in accordance

therewith. It fully justifies the comment of the Supreme

Court of Oklahoma: “The effect of her actions was to

withhold or refrain from giving to the proper officials, the

right or option or opportunity to provide separate educa

tion in law for her * * *” (R. 47). This attitude, so

manifested and continued, gives no assurance that she

would accept legal training in a separate law school, and

justifies the State Regents in taking no action, in so far

as she is concerned, until she indicates a willingness to do

so. For all delay resulting from this conduct, the petitioner

alone is responsible.

CO NCLUSION

We respectfully submit that the petition for certiorari

herein should be denied for want of a substantial Federal

question in that:

(1) The judgment of the Supreme Court of Okla

homa herein correctly applies the Constitution of the

20

United States in holding that petitioner has not been

denied the equal protection of the law by operation

of the constitution and statutes, and the administra

tive action, of the State of Oklahoma herein brought

in question, and

(2) The judgment of the Supreme Court of Okla

homa is based upon the non-Federal ground that the

petitioner has failed to seek relief from the only admin

istrative officers authorized to provide her the facilities

for legal education which she desires.

Respectfully submitted,

Mac Q. W illiamson,

Attorney General of Oklahoma,

Fred Hansen ,

First Assistant Attorney General,

State Capitol,

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma,

Maurice H. Merrill,

John B. Cheadle,

Norman, Oklahoma,

Attorneys for Respondents.

Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al._______

October, 1947.

c >

-Ta

CD*-

• •>

C'?r-