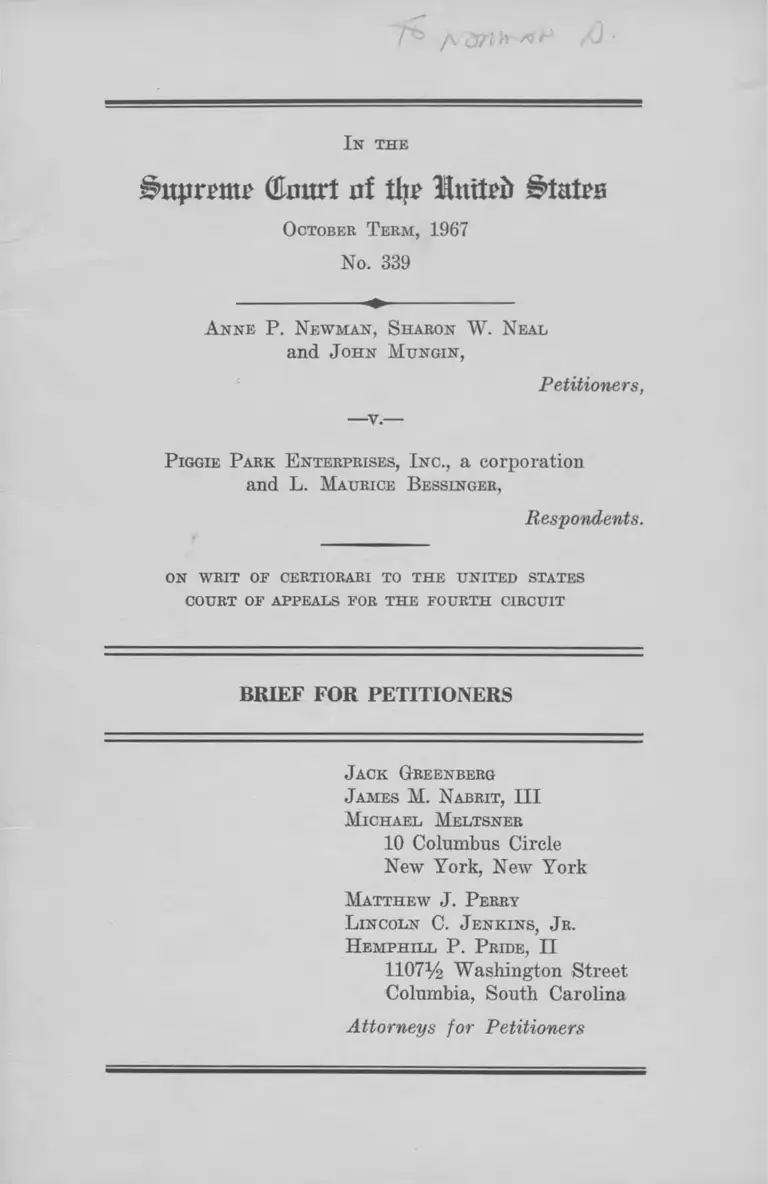

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises Brief for Petitioners, 1967. a4fa5789-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5a32913a-aa4d-4255-bb25-fa3756b9e095/newman-v-piggie-park-enterprises-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

Supreme (Cmtrt iif the Hutted States

October T erm, 1967

No. 339

A nne P. New m an , S haron W. N eal

and John M ungin ,

Petitioners,

P iggie Park E nterprises, Inc., a corporation

and L. Maurice Bessinger,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

M ichael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Matthew J. Perry

L incoln C. Jenkins, Jr.

H emphill P. Pride, II

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below ...................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................................................................ 2

Question Presented .............................................................. 2

Statutory Provisions Involved ........................................... 2

Statement ................................................................................ 2

Summary of Argument ......................................... 6

A rgument ......................................................................................... 7

I. Whether Counsel Pees Are Awarded to a Pre

vailing Plaintiff Under the Public Accommoda

tions Title of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Should

Not Turn on the Subjective Mental State of the

Defendant ................................................................. 7

A. The Fourth Circuit’s standard ................... 9

B. The standard which best effectuates the

ends of Title II .............................................. 11

C. Judge Winter’s standard .............................. 16

II. Under Either the Standard Sought by Peti

tioners or That Urged by Judges Winter and

Sobeloff, the Case Should Be Remanded to the

Courts Below With Instructions to Award Coun

sel Fees to Plaintiff ................................................ 16

Conclusion ............................................................................. 18

u

T able of Cases

p a g e

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, 321 F. 2d

494 (4th Cir. 1963) ....................................................... 10

Fleischman v. Maier Brewing Co., 386 U. S. 714 (1967) 15

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966) ...................... 8

Gilbert v. Hoisting & Portable Engineers, 237 Or. 139,

390 P. 2d 320 (1964) ................................................... 13

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306 (1964) ....... 8

Heart of Atlanta Motel v. U. S., 379 U. S. 241 (1964) .. 8

Katzenbach v. McClung, 371 U. S. 291 (Dec. 1964) .... 17

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Lines R.R., 186 F. 2d 473 (4th

Cir. 1951) ..................................................................... 10,13

Vaughn v. Atkinson, 369 U. S. 527 (1962) ...................... 10

Statutes:

28 U. S. C. §1254(1) ....................................................... 2

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. §2000a...............2, 3, 7

42 U. S. C. §2000a(b) (1-4) .......................................... 8

42 U. S. C. §2000a(c) ........................................................ 8

42 U. S. C. §2000a(c) (2) ................................................... 4

42 U. S. C. §2000a(d) ........................................................ 8

42 U. S. C. §2000a-l .......................................................... 8

42 U. S. C. §2000a-2 .......................................................... 8

PAGE

42 U. S. C. §2000a-3 ....................................................... 8

42 U. S. C. §2000a-3(b) ........................................2,9,11,14

42 U. S. C. §2000a-5(a) ................................................. 8

42 U. S. C. §2000a-5(b) .................................................. 8

42 U. S. C. §2000a-6(a) ................................................. 9

Other Authorities:

110 Cong. Rec. 14214 (June 17, 1964) ...............................9,10

Comment, Private Attorneys-General: Group Action

in the Fight for Civil Liberties, 58 Yale Law Journal

574 (1949) ....................................................................... 13

Ehrenzweig, Reimbursement of Counsel Fees and the

Great Society, 54 Cal. L. Rev. 792 (1966) ................. 14

“ Integration in the South : Erratic Pattern” New York

Times, May 29, 1967 ....................................................... 11

6 Moore’s Federal Practice 1352 .................................... 9

m

I n the

(£mtrt of tljT Ht&nxUb States

October T erm, 1967

No. 339

A nne P. New m an , Sharon W. N eal

and John M ungin ,

Petitioners,

-v-

P iggie Park E nterprises, Inc., a corporation

and L. M aurice Bessinger,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit is reported at 377 F. 2d 433 (A. 159a).

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

District of South Carolina is reported at 256 F. Supp. 941

(A. 135a).

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit was entered on April 24, 1967. The

petition for a writ of certiorari was granted October 9,

1967. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U. S. C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether the Court of Appeals correctly construed Title

II of the Civil Eights Act of 1964 as denying recovery of

counsel fees by Negroes excluded from places of public

accommodation unless a showing is made that a restaura

teur’s patently frivolous defenses and obstructive tactics

were the product of dishonesty and bad faith.

Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves Title II of the Civil Eights Act of

1964, 42 U. S. C. §§2000a et seq., and more particularly,

42 U. S. C. §2000a-3(b):

In any action commenced pursuant to this subchapter,

the court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing

party, other than the United States, a reasonable at

torney’s fee as part of the costs. . . .

Statement

Negro plaintiffs instituted this class action December

18, 1964 against the corporate operator of a chain of six

restaurants and its president and principal stockholder,

3

L. Maurice Bessinger, seeking injunctive relief prohibiting

exclusion of Negroes and recovery of counsel fees pursuant

to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. §§2000a et seq.

The complaint alleged, in summary, that at various loca

tions in South Carolina the corporation operates restau

rants which affect commerce and where Negroes are re

fused service (A. 2a-8a).

Defendants answered by denying Negroes were refused

service; that operation of the restaurants affected com

merce; and that the restaurants were places of “ public ac

commodation” as that term is defined in the Civil Rights

Act of 1964.1 Defendants asserted that Title IT is uncon

stitutional in violation of the Commerce Clause (Art. I,

§8); the Privileges and Immunities Clause (Art. IV, §2);

the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment; and the Thirteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States. In addition, the corpora

tion president alleged that service of food to Negroes, as

required by Title II, violated his freedom of religion as

protected by the First Amendment (A. 9a-21a).

After a two day trial, April 4-5 (A. 22a-134a), the dis

trict court found that the corporation operates six eating

places, five of which are drive-ins located on major high

ways (A. 140a-141a). The sixth, Little Joe’s Sandwich

Shop, is in downtown Columbia, South Carolina, with tables

and chairs for approximately sixty customers (A. 141a-

143a). The district court found “ at least” forty percent of

the food purchased by the restaurants each year moved in

commerce (A. 143a) and that the restaurants served many

1 Defendants filed an answer February 5, 1965, an amended an

swer August 23, 1965, and were permitted by the district court to

file a second amended answer March 19, 1966. All generally denied

the allegations of the complaint.

4

interstate travelers (A. 145a). It concluded for both rea

sons that the operation of the six restaurants affected com

merce within the meaning of Title II, 42 U. S. C. §2000a-

(c)(2 ).

Despite denials of Negro exclusion in the pleadings, the

president of the corporation, a corporation bookkeeper,

and a waitress testified that Negroes were served only on a

kitchen door take-out basis (A. 91a, 98a, 101a, 118a). The

district court found also that two plaintiffs had been denied

service at one of the restaurants because of race (A. 143a-

144a). Attorneys for the plaintiffs were forced to spend

substantial time before the trial amassing evidence to re

but defendants’ denials in the pleadings that a substantial

amount of the food it served moved in commerce. A large

portion of the two day trial was devoted to proving that

the beef, sugar, Coca-cola, vegetables, cheese, salt and

other produce used by defendants came from outside South

Carolina. (These pages of the original record were not

printed by petitioners, in the interests of keeping the Ap

pendix concise.) (E. pp. 20-110).

Although the district court found discrimination, and

that operation of the six restaurants affected commerce, it

excluded the five drive-ins from coverage on the ground

that Congress bad not intended Title II to apply to drive-

ins. It entered an order enjoining racial discrimination at

the Sandwich Shop only, and awarded Negro plaintiffs

their costs, but refused to award counsel fees (A. 158a).

Plaintiffs appealed to the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit; the United States filed a

brief Amicus Curiae which supported plaintiffs’ position

that the drive-in restaurants were covered by the Act and

did not direct itself to the counsel fee issue. The Court of

5

Appeals, sitting en banc, agreed, holding that the district

court should have enjoined racial discrimination at all

restaurants operated by the defendants.

The Court of Appeals further instructed the district

court “ to consider the allowance of counsel fees, whether

in whole or in part,” and set forth the “ subjective” test

which district courts should apply to determine whether

to permit recovery of counsel fees (A. 165a):

In exercising its discretion, the district court may

properly consider whether any of the numerous de

fenses interposed by defendants were presented for

purposes of delay and not in good faith. But the test

should be a subjective one, for no litigant ought to

be punished under the guise of an award of counsel

fees (or in any other manner) from [sic] taking a posi

tion in court in which he honestly believes—however

lacking in merit that position may be.

Judge Winter, with whom Judge Sobeloff joined, dis

agreed with the majority conclusion that “ good faith,

standing alone,” should “ immunize a defendant from an

award against him.” Judge Winter examined the relation

ship of the provision for recovery of counsel fees to en

forcement of Title II, and concluded that a “ subjective”

test would frustrate compliance (A. 166a-167a):

In providing for counsel fees, the manifest purposes

of the Act are to discourage violations, to encourage

complaints by those subjected to discrimination and

to provide a speedy and efficient remedy for those

discriminated against. If counsel fees are withheld or

grudgingly granted, violators feel no sanctions, vie-

6

tims are frustrated and instances of unquestionably

illegal discrimination may well go without effective

remedy. To immunize defendants from an award of

counsel fees, honest beliefs should bear some reason

able relation to reality; never should frivolity go un

recognized.

Petitioners are represented by retained private counsel

of Columbia, South Carolina, who have been assisted by

salaried attorneys of a nonprofit civil rights organization.

The award of counsel fees is sought only by the retained

South Carolina counsel for their services, and not for

others.

Summary of Argument

Congress has left to the courts the determination of

the proper standards for awarding reasonable attorneys’

fees in cases arising under the public accommodations

title of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Petitioners submit

that the subjective bad faith standard formulated by the

court below is improper because it fails utterly to further

the purposes of the Act, and in fact inhibits them. To re

quire proof of an insincere state of mind is unworkable,

inconsistent with the legislative history, and holds Con

gress to have done no more than codify a pre-existing

equity power of the federal courts.

The purpose of the counsel fee provision is to avoid

personal financial loss to private plaintiffs who perform

an essentially public function when they bring injunction

actions to desegregate facilities which have failed to com

ply with the law, and to encourage attorneys to take Title

II cases. The standard which best effectuates this purpose

7

allows counsel fees to prevailing plaintiffs as a matter of

course, absent unusual circumstances. The formulation of

the judges concurring specially below—award of counsel

fees only when defendants raise frivolous defenses or em

ploy dilatory tactics—is also a workable standard. It would

deter vexatious conduct once suit was filed but it would

not materially advance the public policy of Title II by

encouraging initiation of Title II actions against recalci

trant discriminators. Under either the standard urged by

petitioners or that formulated by the concurring judges

below, the judgment below should be vacated and the cause

remanded to the courts below with instructions that coun

sel fees should be awarded to these petitioners.

A R G U M E N T

I.

Whether Counsel Fees Are Awarded to a Prevailing

Plaintiff Under the Public Accommodations Title of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 Should Not Turn on the Sub

jective Mental State of the Defendant.

The counsel fees provision of Title II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. §2000a et seq., is an integral part

of a comprehensive scheme to secure civil rights for all

Americans without regard to race. Enactment of this stat

ute marked a watershed in the history of race relations in

America, and the public accommodations title has become

the most conspicuous symbol of the change. Congress

undertook to write a sweeping law which would bring about

the maximum desegregation of public accommodations in

the shortest possible time. For the Act to be successful,

8

compliance with it had to be universal, for reasons both

psychological and economic. First, not much would be

accomplished if only some restaurants and lodges desegre

gated, for it is scant consolation to the Negro traveler that

many facilities are desegregated if the one he enters con

tinues to discriminate. Second, commerce is burdened by

uncertainty itself when not all eating facilities have de

segregated. And third, individual covered establishments

in some communities might find it profitable to avoid com

pliance if they could avoid being brought to task. Congress

therefore enacted “ most comprehensive” substantive pro

visions, see Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379

U. S. 241, 246 (1964), which extended the coverage of the

Act to the constitutional limits of the Commerce power,

42 U. S. C. §§2000a (b) (1-4), 2000a (c), and the power of

Congress under the Fourteenth Amendment, 42 U. S. C.

§§2000a (d), 2000a-l, and prohibited any attempt to de

prive any person of his rights under the Act, 42 U. S. C.

§2000a-2; see Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306

(1964); Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966). In addi

tion, Title II comprises a series of related provisions,

including the section on counsel fees, which provide for

rapid and effective enforcement of the newly created statu

tory rights and in many ways encourage use of the federal

courts against recalcitrant public accommodations: by

permitting the “ commencement of the civil action without

the payment of fees, costs, or security” where necessary,

42 U. S. C. §2000a-3; by permitting the United States At

torney General to bring civil actions for injunctive relief

when a pattern or practice of discrimination exists, 42

U. S. C. §2000a-5 ( a ) ; by authorizing three-judge courts to

hear suits of general public importance, 42 U. S. C.

§2000a-5 ( b ) ; and by suspending, in Title II suits, the doc

9

trine of exhaustion of administrative remedies, 42 U. S. C.

§2000a-6(a). These sections, like the counsel fee section,

were drafted in response to the desire of Congress to pro

vide Negro plaintiffs with easy access to the courts for

redress of grievances, so that demonstrations like those

preceding passage of the law would not be necessary in the

future.

A. The Fourth Circuit’s standard.

Central to the provisions for enforcement of Title II

is the counsel fee provision, 42 U. S. C. §2000a-3(b). The

legislative history of this section is meager, but by making

the award of counsel fees discretionary, Congress evi

dently left it to the courts to evolve standards for the

implementation of this section which would best advance

the purposes of the Act. What little the legislative history

reveals is inconsistent with the majority opinion below—

awarding attorneys’ fees only where the defendant was in

subjective bad faith. Senator Miller, opposing an amend

ment that would have deleted this section, suggested that

attorneys’ fees would be granted in “meritorious” cases,

110 Cong. Rec. 14214, June 17, 1964, and neither he nor

anyone else suggested that a subjective mental state evinc

ing bad motives was to be a prerequisite for an award of

reasonable fees. Three other factors also demonstrate that

the subjective bad faith standard is not a proper construc

tion of 42 U. S. C. §2000a-3(b). First, such a construction

holds Congress to have done nothing more in the section

than codify existing law, for long before the Civil Rights

Act, federal district courts had inherent power to do what

the Fourth Circuit’s reading of the section authorizes; that

is, to award counsel fees to a successful plaintiff where a

defense is maintained “ in bad faith, vexatiously, wantonly,

or for oppressive reasons.” 6 Moore’s Federal Practice

10

1352. See Vaughn v. Atkinson, 369 U. S. 527 (1962). And

for years federal courts have been imposing such costs in

racial discrimination cases where manifest insincerity and

had faith have been shown. Bell v. School Board of

Powhatan County, 321 F. 2d 494 (4th Cir. 1963); Rolax v.

Atlantic Coast Line R.R., 186 F. 2d 473 (4th Cir. 1951).

Statutes authorizing awards of counsel fees in private

litigation are unusual departures from the general Ameri

can rule of letting the costs of counsel lie with the party

hiring counsel; such statutes should not be read to add

nothing to the power of the federal courts. This conclu

sion is bolstered by the fact that the Senate rejected a move

to delete the counsel fee provision on the ground that to

grant counsel fees conflicted with the prevailing practice,

110 Cong. Rec. 14214 (June 17, 1964).

Second, the court below said that “ the test should be a

subjective one, for no litigant ought to be punished . . .

from (sic) taking a position in court in which he honestly

believes—however lacking in merit that position may be”

(A. 165a). But it will rarely be possible for a plaintiff to

prove the subjective state of mind of a defendant. This

is a fact about which all of the evidence is in the defen

dant’s possession. Occasionally a defendant may make

a statement during trial reflecting on his state of mind

which will be adverse to his position, but the award of rea

sonable counsel fees could not have been intended to turn

upon such a fortuity which bears no rational relationship

to increasing the extent of desegregation.

Finally, it seems impossible to apply a subjective stand

ard at all where, as is often the case and is the case here,

a defendant is a corporation. Just whose intent the district

court is to look to under the Fourth Circuit standard is

11

unclear. The general counsel’s, since he decides which

defenses to interpose? What if the company has more than

one counsel, and each attorney has a different state of

mind? Should the court look to the intent of the directors

on the theory that they directed the work of the counsel and

are generally responsible for what he does? Again, what

if the directors differed in whether they “ honestly believed”

that a defense was a serious one? Of what relevance are

the beliefs on the stockholders, the true owners of the de

fendant corporation? All of these considerations make it

unreasonable to interpret §2000a-3(b) to require a vexa

tious state of mind.

B. The standard which best effectuates the

ends o f Title II.

In order to determine the counsel fee standard which

best effectuates the puiqxoses of Title II it is necessary to

examine the function of the private remedy which Congress

authorized. It was plain when Congress passed the Act

that to the extent universal voluntary compliance was not

achieved, widespread use of the courts would be necessary

to ensure maximum desegregation. In fact although volun

tary compliance was quickly achieved in many major cities,

and large chain restaurants and lodges adhered to the Act

immediately, hundreds of smaller establishments, particu

larly in the small cities and rural areas of the South, have

not yet conformed to the Act.2 Hundreds of suits will be

2 As a recent survey by the New York Times (“ Integration in

South: Erratic Pattern” ) put it :

It is possible to motor through the green valleys of Virginia,

veer through the cotton fields in Alabama and Mississippi, and

12

necessary before equal access to all public accommodations

in the South is a reality. Since the Justice Department

could not be burdened with hundreds of suits of this type,

Congress limited the Department’s role to cases involving

a “ pattern or practice of resistance” , and relied primarily

on private litigants to bring the bulk of the lawsuits neces

sitated by obduracy. The counsel fee provision is crucial

to this enforcement device. Plaintiffs unde]- the Act may

secure only injunctive relief, never damages. Yet the time

and effort which a plaintiff’s attorney must put into pre

paring and arguing a contested case are frequently sub

stantial, as is shown by this record, especially when the

proportion of food the facility purchases in interstate

commerce must be proved. Relatively few Negroes are

likely to bring a suit if they are required to spend signif

icant amounts of their money to integrate each diner at

which they desired to eat, and few attorneys are likely to

waive a fee. Nor should they have to. When a Negro brings

an injunctive suit, he does so not only for himself, but for

all Negroes and whites who wish to eat in integrated facili

ties, and even for hundreds of thousands of Americans who

will never eat at the defendant’s establishment, but who,

through their representatives, chose to make this a country

in which no man was afforded second-class citizenship be

end up in Texas cattle country with the conviction that racial

segregation and discrimination are gone at last.

You could get that impression if you dined at chain restau

rants like Howard Johnson’s, slept in chain motels such as the

Holiday Inns,. . .

A different itinerary might leave you convinced that the

South has not changed at all. Asking for a night’s lodging in

an obscure motel can be risky for a Negro who wants to avoid

embarrassment. And in countless small towns, independent res

taurants cater mainly to an all-white clientele, and Negroes

still watch movies from segregated balconies. (N. Y. Times,

May 29,1967, p. 1, col. 1.)

13

cause of the color of his skin. A Title II suit is a private

action in form only; it is in reality a public suit, and the

plaintiff is in effect a “ private attorney-general” advanc

ing a public policy of the highest priority. Cf-, Comment,

Private Attornevs-General: Group Action on the Fight

for Civil Liberties, 58 Yale L. J. 574 (1949). The many

enforcement provisions of the Act, supra at p. 8 are de

signed to encourage such litigation by individual plain

tiffs, on behalf of this wider public interest. The counsel

fee provision, properly construed, is a key feature in ren

dering this system workable. Negro plaintiffs must have

a certain amount of motivation and perhaps courage, but

Congress has designed the statute so that they need not

be wealthy, and neither they nor their attorneys need sub

sidize a public activity from their own pockets.3 It is be

cause the court below misconstrued the nature of a Title IT

suit that it arrived at too limited a formulation of the con

ditions for an award of counsel fees. Public accommoda

tions do not have a right to maintain segregated facilities

3 The theory that the purpose of counsel fees may be to encourage

“public” litigation by private parties, by saving them whole should

they win, is an accepted device. For example, in Oregon, union

members who succeed in suing union officers guilty of wrongdoing

are entitled to counsel fees both at the trial level and on appeal,

because they are protecting an interest of the general public:

If those who wish to preserve the internal democracy of the

union are required to pay out of their own pockets the cost of

employing counsel, they are not apt to take legal action to

correct the abuse. . . . The allowance of attorneys’ fees both in

the trial court and on appeal will tend to encourage union

members to bring into court their complaints of union mis

management and thus the public interest as well as the interest

of the union will be served.

Gilbert v. Hoisting d* Portable Engineers, 237 Or. 139, 390 P. 2d

320 (1964). See also Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R.R., 186 F. 2d

473 (4th Cir. 1951).

14

until sued. They have a duty to integrate. The purpose of

the counsel fee section is not merely to punish a defendant

who adopts obstructionist tactics during a trial which should

never have been required in the first place; rather, the pur

pose is to encourage the bringing of suits against public

accommodations which fail to perform their basic obliga

tions under the Act.

The construction of §2000a-3(b) which best promotes

these ends is for the lower courts always to presume that

prevailing plaintiffs are entitled to counsel fees unless very

special circumstances render such a disposition unjust,4

Prevailing defendants, on the other hand, need not rou

tinely receive counsel fees. No analogous public policy

encourages restaurants just beyond the coverage of the Act

to resist integration by every means possible. Though the

Act permits district courts to award counsel fees to the

prevailing “party” , it would be sufficient to award such

fees to a prevailing defendant only when the initiation or

conduct of plaintiff’s suit was manifestly frivolous (as, for

example, when another plaintiff had just lost a suit against

the same defendant). Such standards ideally serve the

function of the Act: they promote integration of public

accommodations. They do not render §2000a-3(b) subject

to the objection which has thus far prevented awards of

counsel fees to the prevailing party from becoming a stand

ard feature of American jurisprudence5—that they dis

4 For example, it might arguably have been proper to let attor

neys’ fees rest with the respective parties in the very first case

testing the constitutionality of the Act, since defendants challeng

ing the statute on constitutional grounds would also be performing

a public function.

5 In no other country in the world is the prevailing party in a

civil suit required to bear the expense of enforcing his just claim.

Ehrenzweig, Reimbursement of Counsel Fees and the Great Society,

54 Cal. L. Rev. 792, 793 (1966).

15

courage the poor from bringing lawsuits because they

might have to pay an uncertain amount of defendant’s coun

sel fees. See Fleischman v. Maier Brewing Co., 386 U. S.

714, 718 (1967). Nor are they inconsistent with the Act’s

grant of “ discretion” to the district courts. Such discre

tion is properly applicable to a determination of the “ rea

sonable” amount of fees awarded, rather than whether fees

are to be awarded at all.

The above rules will lead to maximum enforcement, which

must ultimately depend upon the energies of private liti

gants. Neither the Department of Justice nor the civil

rights organizations have the money or the personnel that

would be necessary to bring suits in hundreds of rural

communities in the South. Although the Office of Economic

Opportunity has sponsored the establishment of 292 “ law

offices for the poor” , only 36 communities have such pro

grams in the eleven states of the Confederacy (and Ala

bama has none). Significantly, petitioners’ counsel has been

informed that no neighborhood law office for the poor set

up by the Office of Economic Opportunity has participated

in a public accommodations case. Hopefully, the grant of

counsel fees as a matter of course to plaintiffs successful

in integrating public accommodations will not only further

the purposes of the Act, but may ultimately involve a

much broader segment of the bar in civil rights litigation;

private attorneys will be more likely to accept a public

accommodations case if they are offered a reasonable like

lihood of being able to collect a fee from a solvent business

enterprise.

16

C. Judge Winter’ s standard.

While the standard petitioners recommend will most

soundly effectuate the Civil Rights Act, it is not the only

workable standard. The interpretation given the counsel

fee section by Judges Winter and Sobeloff, concurring

specially below (awarding counsel fees against defendants

who employ the dilatory tactics or raise objectively frivo

lous defenses), would at least deter defendants from im

posing unnecessary burdens on plaintiffs and then claiming

that their defenses, however frivolous, were in good faith.

Such a standard would not encourage the bringing of Title

II injunctive suits and thereby promote elimination of

segregation, but would help significantly to expedite cases

once brought.

II.

Under Either the Standard Sought by Petitioners or

That Urged by Judges Winter and Sobeloff, the Case

Should Be Remanded to the Courts Below With Instruc

tions to Award Counsel Fees to Plaintiff.

The Fourth Circuit, remanding this case, ordered the

district court to consider the allowance of counsel fees

and added that “ the test should be a subjective one” (A.

165a). If this Court agrees either with petitioners or with

the concurring judges of the Fourth Circuit, different in

structions must be given the district court. If petitioners’

standard constitutes the correct construction of the Act,

the court should be directed to award counsel fees because

no extremely unusual reasons justified defendants in post

poning compliance with the Act until after a trial (April

4, 5, 1966), rather than desegregating when the Act was

17

passed (July 2, 1964) or at the latest when this Court

upheld the constitutionality of the law (December 14, 1964).

On the other hand, if the interpretation given the coun

sel fee section by Judges Winter and Sobeloff is the proper

one, the district court should also be directed to award

counsel fees, because it is plain that all or nearly all of

defendants’ defenses were frivolous and only served to in

crease the difficulty of proving plaintiff’s case and put off

the date of compliance. Defendants in this case pursued

various theories that Title II was unconstitutional years

after the question had been definitively resolved by this

Court in Katsenbadi v. McClung, 371 U. S. 291, in Decem

ber, 1964. A second amended answer raising such defenses

was filed March 30, 1966, after “ carefully reviewing the

pleadings heretofore filed” (A. 17a). Defendants also denied

their activities affected commerce, forcing petitioners to

offer hours of testimony to prove their case. After trial,

the district court (which erroneously excluded the drive-in

facilities on another ground) had no trouble determining

that all six facilities were clearly covered by the Act both

because a substantial portion of the corporation’s food

moved in commerce and because it served or offered to

serve interstate travelers. Likewise, “ the fact that the de

fendants had discriminated both at Piggie Park’s drive-ins

and at Little Joe’s Sandwich Shop was of course known

to them, yet they denied the fact and made it necessary for

the plaintiffs to offer proof, and the defendants could not

and did not undertake at the trial to support their denials”

(A. 167a). In addition, defendants interposed a series of

utterly frivolous defenses, including claims that the Act

was invalid because it “ contravenes the will of God” , that

18

it interfered with the “ free exercise of Defendant’s re

ligion” , that it constituted a taking without just compensa

tion, that it denied defendants equal protection of the laws,

that it abridged the defendants’ privileges and immunities

under Article 4, Section 2, and that it imposed on defen

dants an involuntary servitude. To permit defendants to

require plaintiffs or their attorneys to bear the costs of

presenting opposition to these defenses would severely re

strict the effect of Title II and frustrate the design of

Congress.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully requested

that the judgment below be vacated and the cause be

remanded to the courts below with directions to award

counsel fees to petitioners.

Kespectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Matthew J. Perry

L incoln C. Jenkins, Jr.

H emphill P. Pride, II

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

RECORJP/m

B NORTON STREET

HEW YORK M, K. Y.

38