City of New Orleans v. Barthe Record on Appeal

Public Court Documents

December 2, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of New Orleans v. Barthe Record on Appeal, 1963. 910ae16a-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5a769686-3b65-4e14-aa6f-5f410352d44b/city-of-new-orleans-v-barthe-record-on-appeal. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

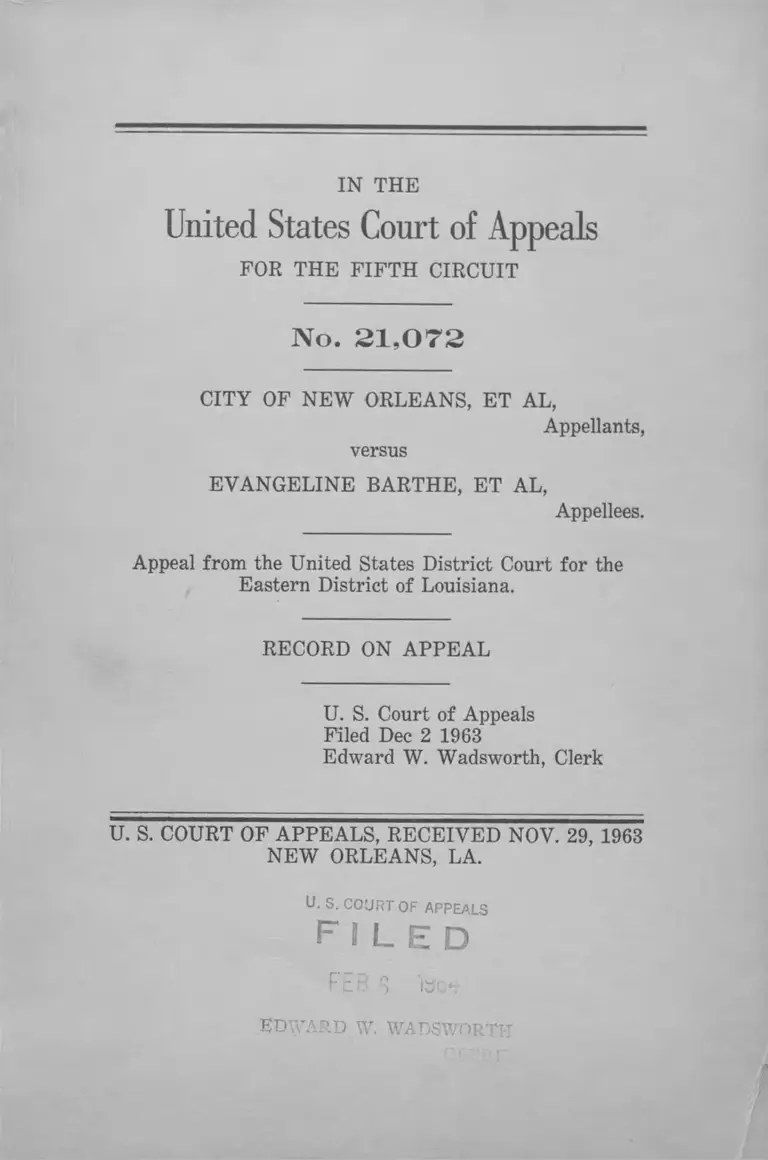

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 21,072

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET AL,

Appellants,

versus

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET AL,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana.

RECORD ON APPEAL

U. S. Court of Appeals

Filed Dec 2 1963

Edward W. Wadsworth, Clerk

U. S. COURT OF APPEALS, RECEIVED NOV. 29, 1963

NEW ORLEANS, LA.

U. S. COURT OF APPEALS

f i l e d

FEB 3 Wcl-

Edward w. wabsworth

INDEX

PAGE

Request that Designated Portions of the Record be

Printed_______________________________________ 2

Complaint_________________________________________ 6

Order to Convoke Three Judge District Court_______ 22

Answer with Defenses_____________________________ 24

Answer to Request for Admission of Facts__________ 29

Answer to Interrogatories__________________________ 32

Objections to Interrogatories_______________________ 34

Request for Admission of Facts____________________ 37

Request for Admission_____________________________ 39

Request for Admission_____________________________ 41

Interrogatories_______________________________________43

Interrogatories____________________________________ 45

Answers to Interrogatories_________________________ 50

Motion for Preliminary Injunction_________________ 79

Plaintiffs’ Memorandum in Support of Motion for

Preliminary Injunction________________________ 82

Notice of Motion___________________________________ 87

Answers to Interrogatories_________________________ 88

Motion to Dismiss Parties Defendant_______________ 93

Opposition to Plaintiff’s Motion for a Preliminary

Injunction_____________________________________ 95

Affidavit.______________________ ______ ______ _____ 97

Opinion of the Court_______________________________ 103

Injunction Bond___________________________________ 107

Judgment__________________________________________ 109

Motion to Fix Bond________________________________ 112

IN DEX— ( Continued)

ii

PAGE

Notice of Appeal to the Supreme Court of the

United States_________________________________ 115

Notice of Appeal to the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit__________________ 121

Cost Bond on Appeal______________________________ 123

Cost Bond on Appeal______________________________ 131

Transcript of Testimony___________________________ 136

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

IN THE

No. 21,072

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET AL,

Appellants,

versus

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET AL,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana.

RECORD ON APPEAL

U. S. Court of Appeals

Filed Dec 2 1963

Edward W. Wadsworth, Clerk

U. S. COURT OF APPEALS, RECEIVED NOV. 29, 1963

NEW ORLEANS, LA.

2

U. S. Court of Appeals

Filed Dec 2 1963

Edward W. Wadsworth, Clerk

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 21,072

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET ALS.,

Appellants

VS.

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET ALS.,

Appellees

REQUEST THAT DESIGNATED PORTIONS

OF RECORD BE PRINTED

Appellants, the City of New Orleans; Victor H.

Schiro, Mayor of the City of New Orleans; Lester J.

Lautenschlaeger, Director, Department of Recreation of

the City of New Orleans; Joseph Giarrusso, Superintend

ent of Police of the City of New Orleans; New Orleans

Parkway and Park Commission; Felix Seeger, Superin

tendent of the New Orleans Parkway and Park Commis

sion; Herman E. Farley, Wilson S. Callender, A. L. Nor

ris, Max Scheinuk, Herbert Jahncke, Lester J. Lauten

schlaeger, L. A. Malony, Sr., J. P. Gentilich, M. E. Poi

son, Mrs. Joe W. Brown and Mrs. S. M. Blackshear, as

members of the New Orleans Park and Parkway Com

mission, believing that the whole of the record herein is

not necessary to be considered by the Court, request that

only the following designated portions of the record be

printed.

(1) The petition of Evangeline Barthe, et als., for a

declaratory judgment and an injunction to enjoin the en

forcement of L.S.A.-R.S. 33:4558.1 as same is contrary

to the due process and equal protection clauses of the

3

Constitution of the United States, filed on 20 December,

1962.

(2) Answer with defenses of the City of New Orleans,

Victor H. Schiro, individually and as Mayor of the City

of New Orleans; James E. Fitzmorris, Jr., Joseph V. Di-

Rosa, Henry B. Curtis, Walter F. Marcus, Clarence 0.

Dupuy, John J. Petre, Daniel L. Kelly, individually and

as Councilmen of the City of New Orleans; Lester J.

Lautenschlaeger, individually and as Director, Depart

ment of Recreation of the City of New Orleans; Joseph

Giarrusso, Individually and as Superintendent of Police

of the City of New Orleans, New Orleans Parkway and

Park Commission; Felix Seeger, Superintendent; Herman

E. Farley, Wilson S. Callender, A. L. Norris, Max Schei-

nuk, Herbert Jahncke, Lester J. Lautenschlaeger, L. A.

Malony, Sr., J. P. Gentilich, M. E. Poison, Mrs. Joe W.

Brown and Mrs. S. M. Blackshear, individually and as

members of the New Orleans Park and Parkway Commis

sion, filed on March 4, 1963.

(3) Interrogatories propounded by the plaintiffs to the

defendants filed on 6 May, 1963.

(4) Request for admissions propounded by the plaintiffs

to the defendants and filed on 6 May, 1963.

(5) (6) Request for admission propounded by the

plaintiffs to the defendants and filed on 6 May, 1963.

(7) Request for Admission of Facts propounded by the

plaintiffs to the defendants and filed on 6 May, 1963.

(8) Answer to request for Admission of Facts filed by

defendants on 30 April, 1963.

(9) Objections to Interrogatories filed by defendants on

30 April, 1963.

(10) Answer to Interrogatories filed by defendants on

30 April, 1963.

(11) Interrogatories propounded by the plaintiffs to the

defendants and filed on 17 May 1963.

(12) Plaintiffs’ Memorandum in Support of Motion for

4

Preliminary Injunction filed on 31 May, 1963.

(13) Motion for Preliminary Injunction filed by plain

tiffs on 31 May, 1963.

(14) Notice of Motion for preliminary injunction filed

on 31 May, 1963.

(15) Answers to Interrogatories by defendants filed on

5 June, 1963.

(16) Answers to Interrogatories by defendants filed on

10 June, 1963.

(17) Order appointing three judge Court to hear this

matter signed by Chief Judge Elbert P. Tuttle on 14

January, 1963.

(18) Affidavit of Mr. Anthony Ciaccio dated 21st day of

June, 1963, and filed on 24 June, 1963.

(19) Exhibit “A” , Exhibit “B” , Exhibit “ C” , and, Ex

hibit “D” each dated June 17, 1963, prepared by the

Louisiana State Board of Health, Division of Public

Health Statistics, Tabulation and Analysis Section, and,

annexed to the foregoing affidavit.

(20) Opposition to Plaintiff’s Motion for a Preliminary

Injunction filed by the defendants on 24 June, 1963.

(21) Motion to Dismiss Parties Defendant filed on 24

June, 1963.

(22) Opinion of the Court dated July 31, 1963 and filed

on 1 August, 1963.

(23) Declaratory judgment and injunction dated Sep

tember 27, 1963, filed on 27 September, 1963.

(24) Transcript of testimony taken in this matter at

hearing on June 26, 1963.

(25) Notice of appeal filed by the various defendants

to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit and, the Supreme Court of the United States with

designation of record on appeal, filed on the 25th day of

October, 1963.

5

(26) Bond of Edwin J. Barthe, as principal, in the sum

of $500.00 filed on 14 August, 1963.

(27) Cost bond on appeal by the various defendants-

appellants in the sum of $250.00 filed on the 25th of

October, 1963.

(28) Motion and order to fix the cost bond on appeal

of Mrs. Joe W. Brown in the sum of $250.00 filed on the

4th of November, 1963.

(29) Cost bond on appeal by the defendant-appellant

Mrs. Joe. W. Brown in the sum of $250,000 filed on the

27th November, 1963.

ALVIN J. LISKA,

City Attorney

ERNEST L. SALATICH,

Assistant City Attorney

Room 2W23— City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

CERTIFICATE

I certify that a copy of the above and foregoing Re

quest that Designated Portions of the Record be Printed

has been sent to opposing counsel-of-record by mailing

same in the United States mail, postage prepaid.

ERNEST L. SALATICH

New Orleans, Louisiana

----------------------------- , 1963.

6

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed Dec. 20 1962

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

DHF

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, a minor,

by EDWIN BARTHE, her father and

next friend; DEBRA E. BURNS,

GARY M. BURNS, LENETTE P.

BURNS, minors, by LEONARD L.

BURNS, their father and next friend;

WILLIAM S. BRADLEY, III, a minor,

by WILLIAM S. BRADLEY, JR., his

father and next friend; WILLARD

W. CASTLE, JR., MYRON CASTLE,

JERRY CASTLE, ERIC CASTLE,

KEITH CASTLE, VALLERY CAS

TLE, ROBIN CASTLE and PATSY

ANN CASTLE, minors, by WILLARD

W. CASTLE, SR., their father and

next friend; SONJA P. COOK, MARY

C. COOK, OLGA C. COOK and JAN

ICE M. COOK, minors, by HOWARD

B. COOK, their father and next

friend; MONICA DE ROUEN and

GLENN DE ROUEN, minors, by

HORACE DE ROUEN, their father

and next friend; YVONNE ELLIS,

LINDER MARIE ELLIS, GWENDO

LYN ELLIS and CLARDIE L. EL

LIS, JR., minors, by CLARDIE L.

ELLIS, SR., their father and next

friend; BARBARA J. FLETCHER,

SHARON A. FLETCHER, MICHA

EL E. FLETCHER and RICKY S.

FLETCHER, minors, by ARTHUR T. ”

FLETCHER, SR., their father and

7

next friend; ISAIAH L. HARRIS,

JR., LINDA M. HARRIS, MICHAEL

W. HARRIS, GREGORY L. HARRIS,

GARY L. HARRIS, GAIL L. HAR

RIS and VAL D. HARRIS, minors,

by ISAIAH L. HARRIS, their father

and next friend; CHESTER C.

HORN, III, DOLORES C. HORN,

JERALD M. HORN, ADRIAN C.

HORN, CHERYL M. HORN, minors,

by CHESTER C. HORN, JR., their

father and next friend; JOSEPH L.

JAMES JR., BOBBIE J. JAMES,

BEVERLY M. JAMES, CONNIE 0.

JAMES, RHONDA F. JAMES and

IONE M. JAMES, minors, by JO

SEPH L. JAMES, SR., their father

and next friend; WILLIE A. MASON,

YVONNE A. MASON, HIRAM L.

MASON, DEBRA Y. MASON, PAUL

A. MASON and PHILIP C. MASON,

minors, by WILLIE L. MASON, their

father and next friend; JUDITH G.

NELSON, MORRIS J. NELSON, JR.,

minors, by MORRIS J. NELSON,

their father and next friend; RU

DOLPH J. ROUSSEAU, III and MI

CHELLE ROUSSEAU, minors, by

RUDOLPH J. ROUSSEAU, JR., their

father and next friend; LOIS M.

SMITH, MONROE W. SMITH, JAN

ICE M. SMITH and JUDY A.

SMITH, minors, by ARTHUR L.

SMITH, their father and next friend;

DONALD SONIAT and CYNTHIA

SONIAT, minors, by LLEWELYN J.

SONIAT, their father and next

friend; ALPHONSE J. SONIAT, III,

CLAUDE T. SONIAT, GLENN A.

SONIAT, DOUGLAS P. SONIAT and

WAYNE M. SONIAT, minors, by AL-

8

PHONSE J. SONIAT, JR., their

father and next friend; JEANNIE

E. SPENCER and LESLIE V. SPEN

CER, minors, by HENRY V. SPEN

CER, their father and next friend;

KEITH TAPLETTE and PATRICIA

TAPLETTE, minors by PETER TAP

LETTE, their father and next friend;

ARNESTA C. TAYLOR, GREGORY

J. TAYLOR, KATHY L. TAYLOR

and BOBBY B. TAYLOR, minors, by

ARNESTA W. TAYLOR, JR., their

father and next friend; JUDITH

THOMAS, a minor, by GERALD H.

THOMAS, her father and next friend;

WESTLEY W. THOMPSON, a mi

nor, by WILLIE W. THOMPSON, his

father and next friend; CLAUDIA

VONTOURE, VANESSA VON-

TOURE, LUCIEN VONTOURE, JR.,

and TRINA VONTOURE, minors, by

LUCIEN VONTOURE, their father

and next friend; GWENDOLYN

WASHINGTON, KENNETH WASH

INGTON and MAURICE WASHING

TON, minors, by ANDERSON V.

WASHINGTON, their father and

next friend; WANDA N. WEBB, a

minor, by WILLIE C. WEBB, her

father and next friend; CHERYL E.

WEBSTER, CYRIL H. WEBSTER

and DWANE D. WEBSTER, minors,

by ALBERT M. WEBSTER, their

father and next friend; and EDWIN

BARTHE, LEONARD L. BURNS,

WILLIAM S. BRADLEY, JR., WIL

LARD W. CASTLE, SR., HOWARD

B. COOK, HORACE DE ROUEN,

CLARDIE L. ELLIS, SR., ARTHUR

T. FLETCHER, SR., ISAIAH L.

HARRIS, CHESTER C. HORN, JR.,

9

JOSEPH L. JAMES, SR., WILLIE

L. MASON, MORRIS J. NELSON,

RUDOLPH J. ROUSSEAU, JR., AR

THUR L. SMITH, LLEWELYN J.

SONIAT, ALPHONSE J. SONIAT,

JR., HENRY V. SPENCER, PETER

TAPLETTE, ARNESTA W. TAY

LOR, JR., GERALD H. THOMAS,

WILLIE W. THOMPSON, LUCIEN

VONTOURE, ANDERSON V.

WASHINGTON, WILLIE C. WEBB

and ALBERT M. WEBSTER,

Plaintiffs,

v.

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, a Muni

cipal Corporation of the State of Lou

isiana; VICTOR H. SCHIRO, indi

vidually and as Mayor of the City of

New Orleans; JAMES E. FITZMOR-

RIS, JR., JOSEPH V. DI ROSA,

HENRY B. CURTIS, WALTER F.

MARCUS, CLARENCE 0. DUPUY,

JOHN J. PETRE, DANIEL L. KEL

LY, individually and as Councilmen

of the City of New Orleans; LESTER

J. LAUTENSCHLAEGER, individu

ally and as Director, Department of

Recreation of the City of New Or

leans; JOSEPH GIARRUSSO, indi

vidually and as Superintendent of Po

lice of the City of New Orleans; NEW

ORLEANS PARKWAY AND PARK

COMMISSION; FELIX SEEGEI^ Su

perintendent; HERMAN E. FAR

LEY, WILSON S. CALLENDER, A.

L. NORRIS, MAX SCHEINUK, HER

BERT JAHNCKE, LESTER J. LAU

TENSCHLAEGER, L. A. MALONY,

SR., J. P. GENTILICH, M. E. POL-

SON, MRS. JOE W. BROWN and

MRS. S. M. BLACKSHEAR, individu-

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 12,968

DIVISION D

10

ally and as members of the New Or

leans Park and Parkway Commission,

Defendants.

......FEE $15.00 Pd. DJ

......PROCESS....................

X CHARGE HAM

......INDEX N

......ORDER.........................

...... HEARING...................

DOCUMENT NO. 1

COMPLAINT

1.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title

28, United States Code, Section 1331, this being a civil

action arising under the Constitution and laws of the

United States, to wit, the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States, Section 1, and Title

42, United States Code, Section 1981, wherein the matter

in controversy exceeds the sum of Ten Thousand and

no/100 Dollars ($10,000.00), exclusive of interest and

costs.

2.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title

28, United States Code, Section 1343(3). This action is

authorized by Title 42, United States Code, Section 1983,

to be commenced by any citizen of the United States or

other person within the jurisdiction thereof, to redress

the deprivation under color of a state law, statute, ordi

nance, regulation, custom or usage of rights, privileges

and immunities secured by the Constitution and laws of

the United States, to wit, the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States, Section 1, and

Title 42, United States Code, Section 1981, providing for

the equal rights of citizens and all other persons within

the jurisdiction of the United States.

3.

The jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281. This is an

action for an interlocutory and permanent injunction,

11

restraining, upon the grounds of their unconstitutionality

under the due process and equal protection clauses of the

Constitution of the United States, the enforcement of

LSA-R.S. 33:4558.1, a statute of the State of Louisiana

as more fully appears hereinafter.

4.

This is a proceeding for a permanent injunction en

joining defendants from enforcing any law, ordinance or

regulation, custom or usage prohibiting Negro citizens

and residents of the City of New Orleans, State of Lou

isiana, the use and enjoyment of all of that City’s public

parks, recreation centers, playgrounds, community cen

ters and other recreational facilities and programs and

denying to them solely because of their race and color,

the right to visit, use and enjoy all of the public parks,

recreation centers, playgrounds, community centers and

other recreational facilities and programs on a basis of

equality with other citizens of the City of New Orleans,

State of Louisiana.

5.

This is a proceeding for a declaratory judgment under

Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2201 and 2202, to

declare the rights and legal relations of the parties in the

matter in controversy, to wit:

Whether the enforcement, execution or operation

of LSA-R.S. 33:4558.1 which requires separate

public parks, recreation centers, playgrounds, and

community centers for Negro and white citizens,

denies to plaintiffs and all other Negro citizens

their rights, privileges and immunities as citizens

of the United States, due process of law and equal

protection of the laws as secured by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States, and rights and privileges secured

to them by Title 42, United States Code, Sections

1981 and 1983, and whether the enforcement, exe

cution and operation of the said statute is for the

aforesaid reason unconstitutional and void.

12

6.

This is a class action brought by the plaintiffs on

behalf of themselves and other persons similarly situated

pursuant to Rule 23(a) (3) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure. The class consists of Negro citizens of the

United States and the State of Louisiana who reside in

New Orleans, Louisiana. All members of the class are

similarly affected by the laws, ordinances, regulations,

customs and usages of the defendants which prevent

Negroes from using and enjoying public parks, recrea

tion centers, playgrounds, community centers and ether

recreational facilities and programs without restrictions

based solely upon considerations of race and color; said

persons constitute a class too numerous to be brought

individually before this Court, but there are common

questions of law and fact involved, a common grievance

arising out of a common wrong and a common relief is

sought for each plaintiff and for each member of the

class, as hereinafter more fully appears. The named

plaintiffs fairly and adequately represent the members of

the class on behalf of which they sue.

7.

The minor plaintiffs are Negroes and citizens of the

United States and the State of Louisiana. The adult

plaintiffs are Negroes and citizens of the United States

and the State of Louisiana, and the parents of the minor

plaintiffs. All plaintiffs are presently living and residing

in New Orleans, Louisiana. Plaintiffs, but for their race,

which restriction violates their constitutional rights as set

forth elsewhere herein, are qualified to use all of the

public parks, recreation centers, playgrounds, community

centers and other recreational facilities and programs of

the City of New Orleans, which are under the jurisdic

tion, management and control of the defendants. Plain

tiffs are ready, willing and able to abide by all rules and

regulations of defendants with respect to the use and

enjoyment of such facilities which are applicable alike to

all persons desiring to use and enjoy such facilities.

13

8.

(a) Defendant City of New Orleans is a municipal

corporation in the Parish of Orleans, State of Louisiana

and is organized and exists under the laws of the State

of Louisiana.

(b) The defendant Victor H. Schiro is a resident of

the City of New Orleans, State of Louisiana, and is Mayor

of the City of New Orleans. James E. Fitzmorris, Jr.,

Joseph V. DiRosa, Henry B. Curtis, Walter F. Marcus,

Clarence 0. Dupuy, John J. Petre, and Daniel L. Kelly

are residents of the City of New Orleans, State of Lou

isiana, and are all members of the City Council of New

Orleans. This action is brought against the defendants

named above as individuals and in their official capaci

ties in which they are vested with power to regulate the

use of and/or establish by ordinance, rules and regula

tions to govern the use and enjoyment of public parks,

recreation centers, playgrounds, community centers, other

recreational facilities and programs in the City of New

Orleans.

(c) The defendant Lester J. Lautenschlaeger is a

resident of the City of New Orleans, State of Louisiana,

and is Director of the Department of Recreation of the

City of New Orleans and is vested with the authority

and power to administer, manage, operate, supervise and

direct the activities of the Department of Recreation of

the City of New Orleans, which Department has under its

control recreation facilities, playgrounds, community cen

ters and other recreational facilities and programs.

(d) The defendant Joseph Giarrusso is a resident

of the City of New Orleans, State of Louisiana, and is

Superintendent of Police of the City of New Orleans.

This action is brought against the above named defend

ant, individually and in his official capacity, in which he

is vested with the power to enforce the ordinances of the

City of New Orleans and all laws, and prevent their vio

lation, pursuant to Section 4-501, Home Rule Charter of

the City of New Orleans.

14

(e) The defendant New Orleans Park and Park

way Commission is a board of the City of New Orleans

and has the power to administer, control and manage all

parks and to designate portions of parks and other areas

under its control for activities under the direction of the

Department of Recreation of the City of New Orleans.

(f) The defendants Felix Seeger, Herman E. Far

ley, Nelson S. Callender, A. L. Norris, Max Scheinuk,

Herbert Jahncke, Lester J. Lautenschlaeger, L. A. Ma-

lony, Sr., J. P. Gentilich, M. E. Poison, Mrs. Joe E.

Brown and Mrs. S. M. Blackshear, constitute the superin

tendent and members of the New Orleans Park and Park

way Commission.

9.

LSRA-R.S. 33:4558.1 provides as follows:

“A. All public parks, recreation centers, play

grounds, community centers and other such facili

ties at which swimming, dancing, golfing, skating

or other recreational activities are conducted shall

be operated separately for members of the white

and colored races. This shall not preclude mixed

audiences at such facilities, provided separated

sections and rest room facilities are reserved for

members of white and colored races. This pro

vision is made in the exercise of the state’s police

power and for the purpose of protecting the public

health, morals and peace and good order in the

state and not because of race.

“B. ‘Public’ parks and other recreational fa

cilities as used herein shall mean any and all rec

reational facilities operated by the state of Louisi

ana or any of its parishes, municipalities or other

subdivisions of the state.

“'C. Any person, firm, or corporation violat

ing any of the provisions of this Section shall be

deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and upon convic

tion therefor by a court of competent jurisdiction

for each such violation shall be fined not less than

15

five hundred dollars nor more than one thousand

dollars, or sentenced to imprisonment in the parish

jail not less than ninety days nor more than six

months, or both, fined and imprisoned as above, at

the discretion of the court.”

10.

(a) On or about June 8, 1962, approximately 1,000

Negroes, including the adult plaintiffs, submitted for

themselves and on behalf of their children, the minor

plaintiffs, a formal written petition signed by each of

them to the Mayor, Councilmen of the City of New Or

leans, and the Director, Recreation Department of the

City of New Orleans. The petition referred to facilities

and programs of the Recreation Department of the City

of New Orleans and recited that the said facilities and

programs are presently operated on a racially segregated

basis. The petition prayed that all facilities and pro

grams of the New Orleans Recreation Department be

available to all the citizens of New Orleans without re

gard to race, color or creed.

(b) The defendants Mayor of the City of New Or

leans, City Councilmen of the City of New Orleans, and

the Director, Recreation Department of the City of New

Orleans have not acknowledged nor replied to plaintiffs’

request contained in the said petition.

(c) The failure of defendants Mayor of the City of

New Orleans, City Councilmen of New Orleans, and the

Director, Recreation Department of the City of New Or

leans, to acknowledge or reply to plaintiffs’ request is

tantamount to a denial of plaintiffs’ request and is due

solely to plaintiffs’ race and color and constitutes a denial

of plaintiffs’ right under the Constitution and laws of

the United States to the equal protection of the laws and

of equal treatment before the law.

11.

(a) On or about October 31, 1962, plaintiffs sub

mitted a copy of said petition to the New Orleans Park

way and Park Commission.

16

(b) Defendant, New Orleans Parkway and Park

Commission informed plaintiffs via letter to Arthur J.

Chapital, Sr., that the facilities listed in the said petition

were under the jurisdiction of the New Orleans Recrea

tion Department.

12.

That the public parks, recreation centers, play

grounds, community centers, recreational programs and

facilities of the City of New Orleans are still operated by

defendants on a racially segregated basis, plaintiffs and

all other Negro citizens of the City of New Orleans being

denied their use in the same manner as white residents

of the City of New Orleans. Said operation by defendants

under color of state law, ordinance, custom, policy and

usage constitutes a denial to these plaintiffs and to those

similarly situated of the equal protection of the laws and

of equal treatment before the law guaranteed to them by

the Constitution and laws of the United States.

13.

Plaintiffs and all other Negro residents of the City

of New Orleans have been compelled to use and enjoy

segregated public parks, recreation centers, playgrounds,

community centers, recreational programs and facilities,

and have suffered great injury, inconvenience, and hu

miliation as a result of the denial to them of their con

stitutional rights to use and enjoy the said facilities and

programs on an unsegregated basis without fear or in

timidation, and possible arrest, conviction, fine and/or

imprisonment.

14.

Plaintiffs and all other Negro residents of the City

of New Orleans are threatened with irreparable injury

by reason of the conditions herein complained of. They

have no plain, adequate or complete remedy to redress

these wrongs other than by this suit for an injunction.

Any other remedy would be attended by such uncertain

17

ties and delays as to deny substantial relief and would

involve a multiplicity of suits and cause further irrepara

ble injury, damage and inconvenience to plaintiffs and

all other Negro residents of the City of New Orleans.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs pray that:

(1) The Court advance this complaint on the docket

and order a speedy hearing thereof according to law and

that upon such hearing the Court enter a temporary in

junction to enjoin and restrain the defendants and each

of them from enforcing LSA-R.S. 33:4558.1 of the State

of Louisiana, and any and all customs, ordinances, prac

tices and usages pursuant to which plaintiffs and all

other Negro citizens of the City of New Orleans are com

pelled to use and enjoy segregated public parks, recreation

centers, playgrounds, community centers, recreational fa

cilities and programs, on the ground that such statute is

null and void and in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

(2) The Court enter a temporary injunction to en

join and restrain the defendants, and each of them, from

denying to plaintiffs, and to those similarly situated, the

use and enjoyment of public parks, recreation centers,

playgrounds, community centers, recreational facilities

and programs under the direction and administration of

the defendants or either of them in the same manner and

under the same terms and conditions as white residents of

the City of New Orleans.

(3) The Court, upon a final hearing of this cause,

will:

(a) Enter a final judgment and decree that

will declare and define the legal rights of the parties in

relation to the subject matter of this controversy.

(b) Enter a final judgment and decree that

will declare that LSA-R.S. 33:4558.1 of the State of Lou

isiana is unconstitutional and therefore null and void in

that it denies to plaintiffs, as individuals, and all other

Negro citizens of the City of New Orleans, privileges and

immunities of citizens of the United States, due process

18

of law and equal protection of the laws secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States and the rights and privileges secured to them by

Sections 1981 and 1983 of Title 42, United States Code.

(c) Enter a final judgment and decree enjoin

ing the defendants, and each of them, their agents, serv

ants and employees, from enforcing the aforesaid stat

utes on the ground that they are unconstitutional and

therefore null and void.

(d) Enter a final judgment and decree enjoin

ing the defendants, their agents, servants and employees

from denying to plaintiffs and others similarly situated

the use and enjoyment of public parks, recreation centers,

playgrounds, community centers, recreational facilities

and programs under the direction and administration of

the defendants or either of them in the same manner and

under the same terms and conditions as white residents

of the City of New Orleans.

(4) The Court allow plaintiffs their costs and that

plaintiffs have such other and further relief as may ap

pear just and proper in the premises.

Respectfully submitted,

/ s / ERNEST N. MORIAL

A. P. TUREAUD

ERNEST N. MORIAL

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

JACK GREENBERG

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

A. M. TRUDEAU, JR.

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

19

VERIFICATION

STATE OF LOUISIANA

PARISH OF ORLEANS

BEFORE ME, the undersigned authority, person

ally came and appeared:

LEONARD L. BURNS

who, being first duly sworn, did depose and say:

That he is one of the petitioners in the above and

foregoing petition; that he has read the same and that all

facts and allegations contained therein are true and cor-

!*0ct

/ s / LEONARD L. BURNS

LEONARD L. BURNS

SWORN TO AND SUBSCRIBED BEFORE

ME THIS 20th DAY OF DECEMBER,

1962.

/ s / A. P. TUREAUD

NOTARY PUBLIC

PLEASE SERVE:

(1) CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, through

Hon. Victor H. Schiro, Mayor

City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

(2) HON. VICTOR H. SCHIRO, Mayor

City of New Orleans

City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

(3) HON. JAMES E. FITZMORRIS, JR.

Councilman, City of New Orleans

City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

(4) HON. JOSEPH V. DiROSA

Councilman, City of New Orleans

City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

20

(5) HON. HENRY B. CURTIS

Councilman, City of New Orleans

City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

(6) HON. WALTER F. MARCUS

Councilman, City of New Orleans

City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

(7) HON. CLARENCE 0. DUPUY

Councilman, City of New Orleans

City Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana

(8) HON. JOHN J. PETRE

Councilman, City of New Orleans

City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

(9) HON. DANIEL L. KELLY

Councilman, City of New Orleans

City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

(10) LESTER J. LAUTENSCHLAEGER,

Director

Department of Recreation of the

City of New Orleans

City Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana

(11) JOSEPH GIARRUSSO

Superintendent of Police

City of New Orleans

2700 Tulane Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

(12) NEW ORLEANS PARKWAY and PARK

COMMISSION, through

Felix Seeger, Superintendent

2829 Gentilly Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

(13) FELIX SEEGER

2829 Gentilly Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

21

(14) HERMAN E. FARLEY

3333 Gentilly Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

(15) WILSON S. CALLENDER

Queen & Crescent Bldg.

New Orleans, Louisiana

(16) A. L. NORRIS

1309 Seville Street

New Orleans, Louisiana

(17) MAX SCHEINUK

2600 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

(18) LESTER J. LAUTENSCHLAEGER

Carondelet Building

New Orleans, Louisiana

(19) L. A. MOLONY, SR.

Richards Building

New Orleans, Louisiana

(20) J. P. GENTILICH

720 Lafayette Street

New Orleans, Louisiana

(21) M. E. POLSON

919 Gravier Street

New Orleans, Louisiana

(22) MRS. JOE W. BROWN

5400 Bancroft Srive

New Orleans, Louisiana

(23) MRS. S. M. BLACKSHEAR

623 Bourbon Street

New Orleans, Louisiana

(24) HON. JACK P. F. GREMILLION

Attorney General

State of Louisiana

Louisiana Supreme Court Building

New Orleans, Louisiana

(25) HON. JIMMIE H. DAVIS

Governor, State of Louisiana

State Capitol

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

22

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed Jan 15 1963

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

FCM

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, a minor,

by EDWIN BARTHE, her father and

next friend, et al,

Plaintiffs,

—versus—

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, a Muni

cipal Corporation of the State of Lou

isiana; VICTOR H. SCHIRO, indi

vidually and as Mayor of the City of

New Orleans, et al,

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION

'NO. 12968

The Honorable Robert A. Ainsworth, Jr., United

States District Judge for the Eastern District of Louisi

ana, to whom an application for injunction and other

relief has been presented in the above-styled and num

bered cause, having notified me that the action is one

required by act of Congress to be heard and determined

by a district court of three judges, I, Elbert P. Tuttle,

Chief Judge of the Fifth District, hereby designate the

Honorable John Minor Wisdom, United States Circuit

Judge, and the Honorable Herbert W. Christenberry,

United States District Judge for the Eastern District of

Louisiana, to sit with Judge Ainsworth as members of,

and with him to constitute the said court to hear and

determine the action.

WITNESS my hand this 14th day of January, 1963.

/ s / Elbert P. Tuttle

Elbert P. Tuttle

Chief Judge

Fifth Circuit

23

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed Mar 4 1963

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

FCM

......FEE.......................

......PROCESS.............

X CHARGE HAM

...... INDEX.................. .

V ORDER SMR

......HEARING............

DOCUMENT NO. 6

24

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET ALS

Plaintiffs

VS

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET ALS

Defendants

NO. 12968

- CIVIL ACTION

DIVISION “ D”

ANSWER WITH DEFENSES

Now into Court, through undersigned Counsel, comes

the City of New Orleans, Victor H. Schiro, individually

and as Mayor of the City of New Orleans; James E.

Fitzmorris, Jr., Joseph V. Di Rosa, Henry B. Curtis,

Walter F. Marcus, Clarence 0. Dupuy, John J. Petre,

Daniel L. Kelly, individually and as Councilmen of the

City of New Orleans; Lester J. Lautenschlaeger, individ

ually and as Director, Department of Recreation of the

City of New Orleans; Joseph Giarrusso, individually and

as Superintendent of Police of the City of New Orleans,

New Orleans Parkway and Park Commission; Felix

Seeger, Superintendent; Herman E. Farley, Wilson S.

Callender, A. L. Norris, Max Scheinuk, Herbert Jahncke,

Lester J. Lautenschlaeger, L. A. Malony, Sr., J. P. Gen-

tilich, M. E. Poison, Mrs. Joe W. Brown and Mrs. S. M.

Blackshear, individually and as members of the New Or

leans Park and Parkway Commission, sought to be made

defendants herein and with full reservation and without

waiving in any manner whatsoever any and all motions

and defenses of every nature, heretofore filed by them

and which may be available to them, who in answer to

the complaint filed herein make the following defenses

and answers thereto said answer in no way to be con

strued as a waiver of defenses:

......f e e .................................. .

......PROCESS........................

X CHARGE HAM

...... INDEX.............................

......ORDER.............................

......HEARING.......................

DOCUMENT NO. 9

25

DEFENSES

I.

That this Honorable Court lacks jurisdiction over the

subject matter.

II.

That the complaint filed by the complainants herein

fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

III.

Defendants deny the allegations contained in Article

1 of the complaint.

IV.

Defendants deny the allegations contained in Article

2 of the complaint.

V.

Defendants deny the allegations contained in Article

3 of the complaint.

VI.

Defendants deny the allegations contained in Article

4 of the complaint.

VII.

Defendants deny the allegations contained in Article

5 of the complaint.

VIII.

Defendants deny the allegations contained in Article

6 of the complaint.

IX.

Defendants deny the allegations contained in Article

7 of the complaint.

26

IX.

Defendants deny the allegations contained in Article

7 of the complaint.

X.

Defendants admit the allegations contained in Article

8(a) of the complaint; defendants admit that Victor H.

Schiro is Mayor of the City of New Orleans and that

James E. Fitzmorris, Jr., Joseph V. DiRosa, Henry B.

Curtis, Walter F. Marcus, Clarence 0. Dupuy, John J.

Petre, and, Daniel L. Kelly are members of the City Coun

cil of New Orleans, but deny that the members of the

City Council of New Orleans can give the petitioners

the relief they seek in this matter; defendants admit that

Lester J. Lautenschlaeger is Director of the Department

of Recreation of the City of New Orleans; defendants

admit that Joseph I. Giarrusso is Superintendent of the

New Orleans Police Department; defendants admit that

the New Orleans Park and Parkway Commission is a

board of the City of New Orleans; the defendants admit

that Felix Seeger, Herman E. Farley, Nelson S. Callen

der, A. L. Norris, Max Scheinuk, Herbert Jahncke, Lester

J. Lautenschlaeger, L. A. Malony, Sr., J. P. Gentilich,

M. E. Poison, Mrs. Joe W. Brown and Mrs. S. M. Black-

shear, constitute the superintendent and members of the

New Orleans Park and Parkway Commission.

XI.

Defendants admit that L.S.A.-R.S. 33:4558.1 reads

as set out in the complaint at Article 9.

XII.

Defendants the Mayor, Councilmen of the City of

New Orleans and the Director, Recreation Department

of the City of New Orleans, and the Director, Recreation

Department of the City of New Orleans, admit that a

petition was submitted to them to de-segregate the facili

ties mentioned herein, but deny the remaining allegations

of Article 10 of the complaint.

27

Defendant the New Orleans Parkway and Park Com

mission admit the allegations of Article 11 of the com

plaint.

XIII.

XIV.

The defendants admit that the public parks, recrea

tion centers, playgrounds, community centers, recreation

al program and facilities of the City of New Orleans are

operated on a racially segregated basis, but deny the re

maining allegations of Article 12 of the Complaint.

XV.

The defendants deny the allegations of Article 13 of

the complaint.

XVI.

The Defendants deny the allegations of Article 14 of

the complaint.

WHEREFORE, your respondents herein respectfully

urge that this Honorable Court dismiss these proceedings

at plaintiffs’ cost.

And for all general and equitable relief.

/ s / ALVIN J. LISKA

ALVIN J. LISKA

City Attorney

/ s / ERNEST L. SALATICH

ERNEST L. SALATICH

Assistant City Attorney

Room 2W23— City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

28

CERTIFICATE

I hereby certify that a copy of the above and fore

going answer has this date been served on the plaintiff

herein by sending the same to their attorneys through

the United States mail, postage prepaid.

/ s / ERNEST L. SALATICH

ERNEST L. SALATICH

Assistant City Attorney

New Orleans, Louisiana

March 4, 1963.

29

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed Apr 30 1963

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

HAM

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET ALS, 1

Plaintiff

VS.

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET ALS.

NO. 12,968

- CIVIL ACTION

DIVISION “ D”

Defendants

ANSWER TO REQUEST FOR ADMISSION OF FACTS

Defendants, City of New Orleans, Victor H. Schiro,

individually and as Mayor of the City of New Orleans;

James E. Fitzmorris, Jr., Joseph V. DiRosa, Henry B.

Curtis, Walter F. Marcus, Clarence 0. Dupuy, John J.

Petre, Daniel L. Kelly, individually and as Councilmen of

the City of New Orleans; Lester J. Lautenschlaeger, in

dividually and as Director, Department of Recreation of

the City of New Orleans; Joseph Giarrusso, individually

and as Superintendent of Police of the City of New Or

leans, New Orleans Parkway and Park Commission; Fe

lix Seeger, Superintendent; Herman E. Farley, Wilson S.

Callender, A. L. Norris, Max Scheinuk, Herbert Jahncke,

Lester J. Lautenschlaeger, L. A. Malony, Sr., J. P. Gen-

tilich, M. E. Poison, Mrs. Joe W. Brown and Mrs. S. M.

Blackshear, individually and as members of the New

Orleans Park and Parkway Commission, make the follow

ing statement in response to the request for admission of

facts served upon them by the plaintiffs on April 19,

1963, as follows:

1) Defendants admit that no answer, other than

the letter sent to Arthur J. Chapital, Sr., and re

ferred to in paragraph 11 of the complaint, has

been given to the petition submitted to the defend

ants Mayor, Councilmen of the City of New Or

leans, and the Director, Recreation Department of

the City of New Orleans on or about June 8, 1962,

30

and submitted to the defendant New Orleans Park

way and Park Commission on or about Octoner 31,

1962.

2) Defendants admit that no action has been tak

en to grant the request in the petition that all rec

reational facilities of the New Orleans Recreation

Department in the City of New Orleans be made

available to all persons without regard to race,

creed or color.

3) Defendants admit the genuineness of the let

ter, attached to the request for admission, to Ar

thur J. Chapital, Sr., in answer to a petition sent

on or about October 31, 1962, which letter stated

that the facilities listed in said petition were under

the jurisdiction of the New Orleans Recreation De

partment.

4) Defendants admit the genuineness of the pe

tition, attched to the request for admission, pray

ing that all facilities and programs of the New

Orleans Recreation Department be available to all

the citizens of New Orleans without regard to race,

color, or creed a copy of which was received by

the New Orleans Parkway and Park Commission

on or about October 31, 1962.

5) Defendants admit the genuineness of the pub

lication entitled NORD Facilities, attached to the

request for admission, which lists the recreational

facilities of the New Orleans Recreation Depart

ment, available to white and Negro persons, for

the year 1962.

/ s /

N

......FEE..................................

......PROCESS........................

X CHARGE HAM

...... INDEX............................

......ORDER............................

......HEARING.......................

DOCUMENT NO. 10

HAM

ALVIN J. LISKA

ALVIN J. LISKA

City Attorney

ERNEST L. SALATICH

ERNEST L. SALATICH

Assistant City Attorney

Room 2W23— City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

31

VERIFICATION

STATE OF LOUISIANA

PARISH OF ORLEANS

BEFORE ME, the undersigned authority, personally

came and appeared:

ERNEST L. SALATICH

who, after being by me duly sworn did declare: That he

is one of the attorneys for the defendants named in the

above and foregoing matter; that he has prepared the

above and foregoing answer to request for admission of

facts and that the facts therein set out are true and cor

rect to the best of his information and belief.

/ s / ERNEST L. SALATICH

ERNEST L. SALATICH

Assistant City Attorney

Sworn to and subscribed

before me this 29th day

of April, 1963.

/ s / ALVIN J. LISKA

NOTARY PUBLIC

CERTIFICATE

I certify that a copy of the above and foregoing an

swer to request for admission of facts has been served

upon Attorneys for Complainants, Ernest N. Morial and

A. P. Tureaud, by mailing same to their office, 1821 Or

leans Avenue, New Orleans, Louisiana, and, on Jack

Greenberg, James M. Nabrit, III, and, George B. Smith,

by mailing same to their office, 10 Columbus Circle, New

York 19, New York, on this 29th day of April, 1963.

/ s / ERNEST L. SALATICH

ERNEST L. SALATICH

Assistant City Attorney

32

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed Apr 30 1963

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

NBJ

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET ALS,

Plaintiffs

VS.

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET ALS

Defendants

NO. 12,968

- CIVIL ACTION

DIVISION “ D”

ANSWER TO INTERROGATORIES

Defendants, City of New Orleans, Victor H. Schiro,

individually and as Mayor of the City of New Orleans;

James E. Fitzmorris, Jr., Joseph V. Di Rosa, Henry B.

Curtis, Walter F. Marcus, Clarence 0. Dupury, John J.

Petre, Daniel L. Kelly, individually and as Councilman

of the City of New Orleans; Lester J. Lautenschlaeger,

individually and as Director, Department of Recreation

of the City of New Orleans, Joseph Giarrusso, individu

ally and as Superintendent of Police of the City of New

Orleans, New Orleans Parkway and Park Commission;

Felix Seeger. Superintendent; Herman E. Farley, Wilson

S. Callender, A. L. Norris, Max Scheinuk, Herbert Jahn-

cke, Lester J. Lautenschlaeger, L. A. Malony, Sr., J. P.

Gentilich, M. E. Poison, Mrs. Joe W. Brown and Mrs.

S. M. Blackshear, individually and as members of the

New Orleans Park and Parkway Commission, answers

the Interrogatories served upon them by Plaintiffs here

in on April 19, 1963, as follows:

1) In answer to Interrogatory No. 4, defendants

state that there is no publication similar to that

entitled NORD Facilities, a copy of which is at

33

tached to the Interrogatories, for the year 1963,

nor, is there any similar or later publication.

/ s / ERNEST H. GOULD

ERNEST H. GOULD

New Orleans Recreation Department

Executive Assistant Director

Sworn to and subscribed

before me, Notary, this

30th day of April, 1963.

/ s / ERNEST L. SALATICH

ERNEST L. SALATICH,

Notary Public

CERTIFICATE

I certify that a copy of the foregoing Answer to In

terrogatories was this date served on counsel for plain

tiffs, Ernest N. Morial and A. P. Tureaud, by mailing

same to their offices at 1821 Orleans Avenue, New Or

leans, Louisiana, and, on Jack Greenberg, James N.

Nabrit, III, and, George B. Smith, by mailing same to

their offices at 10 Columbus Circle, New York 19, New

York, through the U. S. Mails, postage prepaid.

New Orleans, Louisiana

30 April, 1963

/ s / ERNEST L. SALATICH

ERNEST L. SALATICH

......FEE..........................

......PROCESS........... ....

X CHARGE HAM

......INDEX....................

......ORDER...................

......HEARING..............

DOCUMENT NO. 11

WBJ

34

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed Apr 30 1963

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

NBJ

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET ALS,

Plaintiffs

VS.

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET ALS,

Defendants

NO. 12,968

> CIVIL ACTION

DIVISION “ D”

OBJECTIONS TO INTERROGATORIES

Defendants, City of New Orleans, Victor H. Schiro,

individually and as Mayor of the City of New Orleans;

James E. Fitzmorris, Jr., Joseph V. Di Rosa, Henry B.

Curtis, Walter F. Marcus, Clarence 0. Dupuy, John J.

Petre, Daniel L. Kelly, individually and as Councilmen

of the City of New Orleans; Lester J. Lautenschlaeger,

individually and as Director, Department of Recreation

of the City of New Orleans, Joseph Giarrusso, individu

ally and as Superintendent of Police of the City of New

Orleans, New Orleans Parkway and Park Commission;

Felix Seeger, Superintendent; Herman E. Farley, Wilson

S. Callender, A. L. Norris, Max Scheinuk, Herbert Jahn-

cke, Lester J. Lautenschlaeger, L. A. Malony, Sr., J. P.

Gentilich, M. E. Poison, Mrs. Joe W. Brown and Mrs.

S. M. Blackshear, individually and as members of the

New Orleans Park and Parkway Commission, object to

Interrogatories served upon them by plaintiffs herein as

follows:

1) Defendants object to Interrogatory No. 1 on the

ground that as propounded, it calls for a list of all of the

public parks, recreation centers, playgrounds, community

35

centers, and other recreational facilities in the City of

New Orleans, many of which parks, etc., are not under

the control of the defendants herein and the plaintiffs

thereby seeks information which is not the subject of this

suit and is therefore irrelevant to the issues.

2) Defendants object to Interrogatory No. 2 on the

ground that as propounded, it calls for a list of all of the

public parks, recreation centers, playgrounds, community

centers, and other recreational facilities in the City of

New Orleans and which of these are used by whites and

which by negroes, whereas many of these parks, etc., are

not under the control of the defendants herein and the

plaintiffs thereby seek information which is not the sub

ject of this suit and is therefore irrelevant to the issues.

3) Defendants object to Interrogatory No. 3 on the

ground that, as propounded it calls for the manner in

which all of the public parks, recreation centers, play

grounds, community centers, and other recreational facili

ties in the City of New Orleans are identified for use by

the white and negro races, whereas many of these parks,

etc; are not under the control of the defendants herein

and the plaintiffs thereby seek information which is not

the subject of this suit and is therefore irrelevant to the

issues.

WHEREFORE, your defendants, move the Court

that they be relieved of the duty of responding to the

aforementioned interrogatories.

/ s / ALVIN J. LISKA

ALVIN J. LISKA E.L.S.

City Attorney

/ s / ERNEST L. SALATICH

ERNEST L. SALATICH

Assistant City Attorney

Attorneys for Defendants

Room 2W23— City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

36

......FEE..........................

......PROCESS...............

X CHARGE HAM

...... INDEX....................

......ORDER...................

V HEARING M

DOCUMENT NO. 12

WBJ

NOTICE

Please take notice that at 10:00 o’clock on the 8th

day of May, 19,63, or as soon thereafter as counsel can

be heard, the defendants set out in the hereinabove ob

jections to interrogatories will present to this Court at its

Court Room, 400 Royal Street, New Orleans, Louisiana,

the aforesaid objections to Interrogatories served upon

them by plaintiffs herein.

/ s / ERNEST L. SALATICH

ERNEST L. SALATICH

Assistant City Attorney

CERTIFICATE

I certify that a copy of the foregoing objections to

Interrogatories have been served upon Attorneys for Com

plainants, Ernest N. Morial and A. P. Tureaud, by mail

ing same to their office, 1821 Orleans Avenue, New Or

leans, Louisiana, and on Jack Greenberg, James M.

Nabrit, III, and, George B. Smith, by mailing same to

their office, 10 Columbus Circle, New York 19, New York,

on this 30th day of April, 1963.

/ s / ERNEST L. SALATICH

ERNEST L. SALATICH

Assistant City Attorney

37

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed May 6 1963

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

NBJ

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET AL.,

Defendants.

No. 12968

Civil Action

Division rrD”

REQUEST FOR ADMISSION OF FACTS

TO: Alvin J. Liska, City Attorney

Ernest L. Salatich, Assistant City Attorney

Room 2W23, City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for Defendants

Please take notice that the plaintiffs hereby request

the defendants, pursuant to Rule 36 of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure, to admit within 10 days after service

of this request, for the purposes of the above-entitled

action only, and subject to all pertinent objections to ad

missibility which may be interposed at the trial, the truth

of the following facts:

1. That no answer, other than the letter sent to

Arthur J. Chapital, Sr. and referred to in paragraph 11

of facilities listed in said petition were under the juris

diction of the New Orleans Recreation Department.

/ s / ERNEST N. MORIAL

ERNEST N. MORIAL

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

38

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

GEORGE B. SMITH

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that the undersigned, counsel for

the plaintiffs, has this day served each of the attorneys

of the defendants in this action, Alvin J. Liska and

Ernest L. Salatich, a copy of the foregoing request for

admission by placing in the United States Mail, postage

prepaid, and directing that they be sent to Room 2W23,

City Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana.

April 18, 1963

/ s / ERNEST N. MORIAL

Attorney for Plaintiffs

......FEE..........................

-...PROCESS..............

X CHARGE HAM

...... INDEX....................

......ORDER...................

......HEARING..............

DOCUMENT NO. 13

39

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed May 6 1963

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

NBJ

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET AL.,

Defendants.

No. 12968

Civil Action

Division “ D”

REQUEST FOR ADMISSION

TO: Alvin J. Liska, City Attorney

Ernest L. Salatich, Assistant City Attorney

Room 2W23, City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

Please take notice that the plaintiffs hereby request

that defendant New Orleans Parkway and Park Commis

sion, pursuant to the provisions of Rule 36 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, within 10 days after service of

this request, admit for the purpose of this action only

and subject to all pertinent objections to admissibility

which may be interposed at the trial, the genuineness of

the letter, attached hereto, to Arthur J. Chapital, Sr. in

answer to a petition sent on or about October 31, 1962,

which letter stated that the complaint, has been given to

the petition submitted to the defendants Mayor, Council-

men of the City of New Orleans, and the Director, Recre

ation Department of the City of New Orleans on or about

June 8, 1962, and submitted to the defendant New Or

leans Parkway and Park Commission on or about October

31, 1962.

2. That no action has been taken to grant the re

quest in the petition that all recreational facilities in the

40

City of New Orleans be made available to all persons

without regard to race, creed or color.

/ s / ERNEST N. MORIAL

ERNEST N. MORIAL

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

GEORGE B. SMITH

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OP SERVICE

This is to certify that the undersigned counsel for

the plaintiffs has this day; served each of the attorneys

of the defendants in this action, Alvin J. Liska and

Ernest L. Salatich, a copy of the foregoing Request for

Admission of Facts by placing same in the United States

Mail, postage prepaid, and directing that they be sent to

Room 2W23, City Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana.

/ s / ERNEST N. MORIAL__________

Attorney for Plaintiffs

April 18, 1963

......FEE...................................

......PROCESS........................

X CHARGE HAM

...... INDEX.............................

......ORDER.............................

......HEARING.......................

DOCUMENT NO. 14

WBJ

41

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed May 6 1963

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

NBJ

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET AL.,

Defendants.

REQUEST FOR ADMISSION

TO: Alvin J. Liska, City Attorney

Ernest L. Salatich, Assistant City Attorney

Room 2W23, City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for Defendants

Please take notice that the plaintiffs hereby request

that defendants, pursuant to the provisions of Rule 36 of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, within 10 days

after service of this request admit, for the purpose of

this action only and subject to all pertinent objections to

admissibility which may be interposed at the trial, that

the following documents, exhibited with this request, are

genuine:

1. A petition praying that all facilities and pro

grams of the New Orleans Recreation Department be

available to all the citizens of New Orleans without re

gard to race, color, or creed and submitted to and received

by the Mayor, Councilmen of the City of New Orleans,

and the Director, Recreation Department of the City of

New Orleans on or about June 8, 1962, a copy of which

was submitted to and received by the New Orleans Park

way and Park Commission on or about October 31, 1962.

No. 12968

- Civil Action

Division “ D”

42

2. A publication entitled NORD Facilities which

lists the recreational facilities available to both white and

Negro persons in New Orleans.

/ s / ERNEST N. MORIAL

ERNEST N. MORIAL

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

GEORGE B. SMITH

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that the undersigned, counsel for

the plaintiffs, has this day served each of the attorneys

of the defendants in this action, Alvin J. Liska and

Ernest L. Salatich, a copy of the foregoing request for

admission by placing same in the United States Mail,

postage prepaid and directing that they be sent to Room

2W23, City Hall, New Orleans, Louisiana.

/ s / ERNEST N. MORIAL

Attorney for Plaintiffs

April 18, 1963

......FEE.................................. .

......PROCESS........................

X CHARGE HAM

...... INDEX.............................

......ORDER............................

......HEARING.......................

DOCUMENT NO. 15

WBJ

43

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed May 6 1963

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

NBJ

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET AL.,

Defendants.

No. 12968

Civil Action

Division “ D”

INTERROGATORIES

TO: Alvin J. Liska, City Attorney

Ernest L. Salatich, Assistant City Attorney

Room 2W23, City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

The plaintiffs request that the above named defend

ants answer under oath in accordance with Rule 33 of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure the following inter

rogatories :

1. List all public parks, recreation centers, play

grounds, community centers, and other recreational fa

cilities in the City of New Orleans.

2. State which of these facilities are for use by

whites and which of these facilities are for use by Ne

groes.

3. State how these facilities are identified by race—

by sign at the facility, rule or resolution of the Recrea

tion Department or Park Commission, by publication of

any document, or any other means.

4. State whether a publication similar to that en

titled NORD Facilities, a copy of which is attached here

to, has been made for the year 1963 or whether any simi

44

lar and later publication has been made by the defend

ants.

/ s / ERNEST N. MORIAL

ERNEST N. MORIAL

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

GEORGE B. SMITH

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that the undersigned, counsel for

plaintiffs, has this day served each of the attorneys of

the defendants in this action, Alvin J. Liska and Ernest

L. Salatich, a copy of the foregoing interrogatories by

placing same in the United States Mail, postage prepaid,

and directing that they be sent to Room 2W23, City Hall,

New Orleans, Louisiana.

/ s / ERNEST N. MORIAL

Attorney for Plaintiffs

April 18, 1963

......FEE...................................

......PROCESS-.....................

X CHARGE HAM

......INDEX.............................

......ORDER.............................

......HEARING.......................

DOCUMENT NO. 16

WBJ

45

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed May 17 1963

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

FCM

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, et al.,

Defendants.

INTERROGATORIES

TO: ALVIN J. LISKA, City Attorney

ERNEST L. SALATICH, Assistant City Attorney

Room 2W23

City Hall

New Orleans, Louisiana

The plaintiffs request that the above named defend

ants answer under oath in accordance with Rule 33 of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure the following inter

rogatories :

1. List all public parks, recreation centers, play

grounds, community centers, and other recrea

tional facilities in the City of New Orleans under

the control, management, or administration of

the defendants.

2. State which of the recreational facilities in the

City of New Orleans under the control, manage

ment, or administration of the defendants are for

use by whites and which facilities are for use by

Negroes.

3. State how the recreational facilities in the City

CIVIL ACTION

-NO. 12,968

DIVISION “ D”

46

of New Orleans which are under the control,

management, or administration of the defendants,

are identified by race—by sign at the facility,

rule or resolution of the Recreation Department

or Park Commission, by publication of any docu

ment, or by any other means.

4. List all special recreational activities and events

sponsored, administered, managed, or controlled

by the defendants, said special activities and

events being in operation now, and/or planned

for the year 1963, such as Soap Box Derbies, fish

ing rodeos, archery competitions, bowling compe

titions, tennis tournaments, presentation of plays,

etc., and designate those special activities avail

able to Negroes.

(a) In the absence of such information, list

all such special activities carried on for the year

1962 and designate those available to Negroes.

5. List any special classes, workshops or the like

carried on, sponsored, administered, managed, or

controlled by the defendants in addition to regu

lar recreational programs, such classes being in

struction in art, ballet, ceramics, other crafts,

fencing, opera, piano instruction, tap dancing,

tumbling, etc., which are being carried on now

or planned for the year 1963 and designate those

classes, workshops, etc., available to Negroes.

(a) In the absence of such information, list

all such special classes for the year 1962 and des

ignate those available to Negroes.

6. List any tours or field trips undertaken or spon

sored by the defendants during the year 1962

and/or planned for the year 1963. Such trips

would include trips to public buildings, museums,

etc.

(a) Designate those in which Negroes could or

can participate.

47

7. List all recreational facilities owned by the City

of New Orleans and located in the City of New

Orleans.

8. List all of the recreational facilities under the

control, management, or administration of the de

fendants which are leased or loaned to the City

of New Orleans or any other defendant for recre

ational purposes, such leases being formal leases

which have been signed, or written or oral agree

ments.

9. State whether any Negro employees, other than

maintenance employees, are employed at any of

the white recreational facilities under the control,

management, or administration of the defendants.

(a) If so state in what positions— supervisor,

park teacher, etc.

10. State whether any white employees, other than

maintenance employees are employed at any of

the Negro recreational facilities under the con

trol, management, or administration of the de

fendants.

(a) If so state in what positions— supervisor,

park teacher, etc.

11. List all recreational facilities under the control,

administration, or management of the defend

ants used or operated on a seasonal basis, and

designate them by race.

12. List all white recreational facilities under the

management, control or administration of the

defendants known as complete community centers

and otherwise designated as AA type facilities.

13. List all Negro recreational facilities under the

management, control or administration of the

defendants and known as complete community

48

centers and otherwise designated as AA type

facilities.

Respectfully submitted,

/ s / ERNEST N. MORIAL

ERNEST N. MORIAL

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

GEORGE B. SMITH

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

49

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, et al.,

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION

-NO. 12,968

DIVISION “D”

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that I served a copy of the plain

tiffs’ Interrogatories upon Alvin J. Liska, Esq., and

Ernest L. Salatich, Esq., Room 2W23, City Hall, New

Orleans, Louisiana, by depositing copies addressed to

them as indicated, in the United States Mail, postage pre

paid, this 16th day of May, 1963.

/ s / ERNEST N. MORIAL

Attorney for Plaintiffs

......FEE..........................

......PROCESS................

X CHARGE HAM

...... INDEX.....................

......ORDER....................

......HEARING...............

DOCUMENT NO. 18

M

50

U. S. District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Filed Jun 5' 1963

A. Dallam O’Brien, Jr., Clerk

FCM

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

EVANGELINE BARTHE, ET ALS, '

Plaintiffs

VS.

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, ET ALS

NO. 12,968

- CIVIL ACTION

DIVISION “ D”

Defendants

ANSWERS TO INTERROGATORIES

Defendants, City of New Orleans, Victor H. Schiro,

individually and as Mayor of the City of New Orleans;

James E. Fitzmorris, Jr., Joseph V. Di Rosa, Henry B.

Curtis, Walter F. Marcus, Clarence 0. Dupuy, John J.

Petre, Daniel L. Kelly, individually and as Councilmen

of the City of New Orleans, Lester J. Lautenschlaeger,

individually and as Director, Department of Recreation

of the City of New Orleans, Joseph Giarrusso, individu

ally and as Superintendent of Police of the City of New

Orleans, answers the Interrogatories served upon them

by Plaintiffs herein on May 20, 1963, as follows:

NORD FACILITIES

ANSWER TO INTERROGATORY #1

1. ALVAR CENTER

2601 Alvar St.

2. ANNUNCIATION PLAYGROUND

Race, Annunciation, Chippewa & Orange Sts.

51

3. ART DEPARTMENT

2711 Dauphine St.

4. AUDUBON PARK BALL DIAMOND &

TENNIS COURTS

River Road & Zoo Drive

5. BEHRMAN HEIGHTS

Square 22, McArthur, Mercedes &

Halsey Sts.

6. BEHRMAN MEMORIAL CENTER

2529 Gen. Meyer Ave. (Algiers)

7. BODENGER PLAYGROUND

Hudson, Memorial Park Dr.,

Nevada & Kansas Sts. (Algiers)

8. BOE PLAYGROUND

Hibernia St. & St. Roch Ave.

9. BONART PLAYGROUND

Forstall, Marais, Lizardi & Urquhart Sts.

10. BROADMOOR PLAYSPOT

Gen. Pershing & Broad Sts.

11. BUNNY FRIEND PLAYGROUND

Desire, Gallier, N. & S. Bunny Friend Sts.

12. CABRINI PLAYGROUND

Barracks, Dauphine & Burgundy Sts.

13. KERRY CURLEY PLAYGROUND

Dwyer Rd., Camelot & Knight Sts.

14. CARVER PLAYGROUND

Lowerline & Prytania Sts.

15. CHILDREN’S MUSEUM

1218 Burgundy St.

16. CITY PARK BALL DIAMONDS

Harrison & Marconi Sts.

17. CLAY PLAYGROUND

Chippewa, Second & Annunciation Sts.

52

18. COLISEUM PLAYGROUND

Camp, Coliseum, Race Sts. & Melpomene Ave.

19. CONRAD PLAYGROUND

Hamilton, Edinburgh, Mistletoe & Olive Sts.

20. COSTUME DEPARTMENT

907 Terpsichore St.

21. CUCCIA-BYRNES PLAYGROUND

Waldo Burton Memorial Home, Olive &

Forshey Sts.

22. CURTIS PLAYGROUND

Lake Ave. & Yacht Harbor

23. DANNELL PLAYGROUND

St. Charles, Octavia & Dannell

24. DELCAZEL PLAYGROUND

Opelousas, Verret & Seguin Sts. (Algiers)

25. DELGADO CENTER

Navarre & Gen. Diaz Sts.

26. DESIRE PROJECT GROUND

Alvar & Florida Sts.

27. DESMARE PLAYGROUND

Esplanade Ave. & Moss St.

28. DEVORE PLAYGROUND

Newton, Brooklyn & Diana Sts.

29. DiBENEDETTO PLAYGROUND

Chef Menteur Hwy., Prentiss, Pressburg &

Papania Sts.

30. DIGBY PLAYGROUND

Dwyer, E. Hermes & Virginia Sts.

31. DONNELLY PLAYGROUND

Wildair Dr., Burbank & Wingate Sts.

32. DREYFUS PLAYSPOT

Stroelitz & Mistletoe Sts.

33. DUBLIN PLAYGROUND

Dublin, Hampson & Maple Sts.

53

34. DULCICH PLAYSPOT

Rear of Behrman Memorial Stadium

(Algiers)

35. EASTON PARK

Toulouse, N. Lopez, St. Peter &

N. Rendon Sts.

36. ELEONORE PLAYGROUND

Eleonore, Annunciation & Alonzo Sts.

37. EQUIPMENT WAREHOUSE

2540 N. Prieur St.

38. ESPENAN PLAYGROUND

Trafalgar & Beauvoir Sts.

39. EVANS PLAYGROUND

Soniat, LaSalle, Dufossat & S. Liberty Sts.

40. FILMORE PLAYGROUND