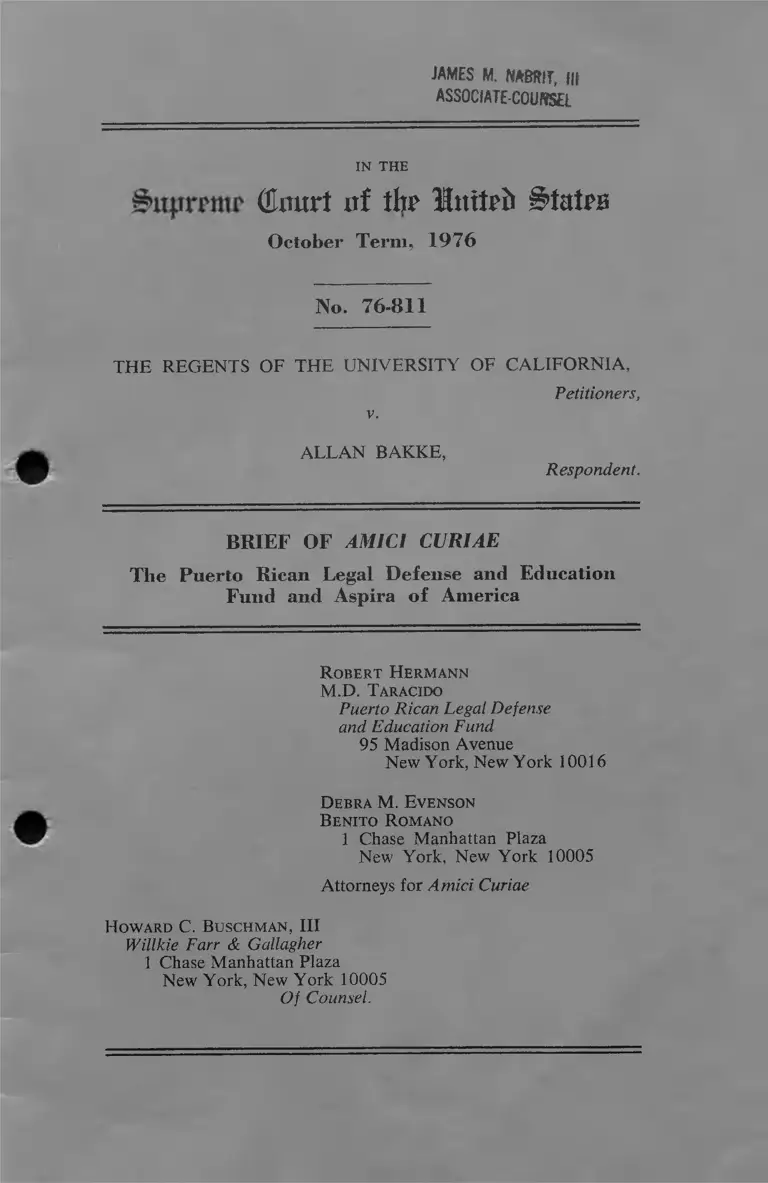

Bakke v. Regents Brief of Amici Curiae of the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund and Aspira of America

Public Court Documents

June 7, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief of Amici Curiae of the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund and Aspira of America, 1977. 9e8eb83b-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5a97017f-fe04-41b0-8b88-997806c12ec5/bakke-v-regents-brief-of-amici-curiae-of-the-puerto-rican-legal-defense-and-education-fund-and-aspira-of-america. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

JAMES M. N m i r , III

ASSOCIATE-COUWSa

IN THE

(tart nf thr Httitrb §tatrB

October Term, 1976

No. 76-811

THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA,

Petitioners,

v.

ALLAN BAKKE,

Respondent.

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

The Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education

Fund and Aspira of America

Robert H ermann

M.D. Taracido

Puerto Rican Legal Defense

and Education Fund

95 Madison Avenue

New York, New York 10016

Debra M. Evenson

Benito Romano

1 Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

Howard C. Buschman, III

Willkie Farr & Gallagher

1 Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

Of Counsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Interest of the A m ic i.................................................... 1

Introductory Statement .............................................. 4

A rgument :

The Special Admissions Program of the Davis

Medical School is Constitutional............................. 6

A. I t Is Permissible For The University To Con

sider Ethnic And Racial Background As One

Of The Many Factors In Selecting Among

Qualified Applicants For A dm ission............... 8

B. The University’s Special Admissions Program

Furthers Compelling State Interests In Rem

edying the Consequences Of Discrimination

And Serving The Unmet Health Needs Of

Minority Communities......................................... 15

Conclusion ............................................................................... 23

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Albemarle v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) ................. 9

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Development Cor

poration, 45 U.S.L.W. 4073 (January 11, 1977) . . . 12

Arnold v. Ballard, 12 Empl. Dec. (CCH) If 11,000

(6th Cir. 1976) .......................................................... 9

Brown v. Board- of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) . . 10

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971), cert,

denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972) ..................................... 9

Civil Rights Cases, 190 U.S. 3 (1883) ......................... 10

1 1

PAGE

Cases (C ont.)

Clarke v. Redeker, 406 F.2d 883 (8th Cir.), cert,

denied, 396 U.S. 862 (1969) ..................................... 20

Examining Board of Engineers, Architects and Sur

veyors v. Flores de Otero, 426 U.S. 572 (1976) . . . 11

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976) 8,9

Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677 (1973) .......... H

Graham v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365 (1971) .............. 10

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430

(1968) ...........'........................................................... 9,17,23

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954) ................. 10

Hills v. Gciutreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976) ..................... 17

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) . . 10

Kahn v. Shevin, 416 U.S. 351 (1974) ......................... 15

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ............. 13

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973) 9,11

Lau y. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) ........................... 17

Local 53, International A ss’n of Meat db Frost In

sulators & Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d

1047 (5th Cir. 1969) .................................................. 9

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co., 427

U.S. 273 (1976) .................................................... 12

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) ............. 10

Memorial Hospital v. Maricopa County, 415 U.S. 250

(1974) ................................................ 17

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) ................... 8

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948) ................. 10

Ill

PAGE

Cases (Cont.)

Patterson v. American Tobacco Go., 535 F.2d 257

(4th Cir. 1976) .......................................................... 9

Rios v. Enterprise Association Steamfitters Local

638, 501 F.2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974) ............................. 9

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodri

guez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973) ............................................ 11, 22

Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873) ............... 10

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............................ ' ..............8,9,14

Sw ift & Co. v. Hocking Valley Ry. Co., 243 U.S. 281

(1917) .......................................................................... 6

United Jewish Organisations of Williamsburgh, Inc.

v. Carey, 45 U.S.L.W. 4221 (March 1, 1977) . .8,12,13,14

United States v. Felin & Co., 334 U.S. 624 (1948) . . . 6

United States v. International Union of Elevator

Constructors, Local 5, 538 F.2d 1012 (3rd Cir.

1976) ........................................................................... 9

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d 544

(9th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971).......... 9

United States v. Montgomery County School of Edu

cation, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) ......................................... 8

United States v. United Brotherhood of Carpenters

& Joiners, Local 169, 457 F.2d 210 (7th Cir.), cert,

denied, 409 U.S. 851 (1972) ....................................... 9

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ................. 7,12

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ................. 10

Legislative Materials

S. Rep. No. 93-1133, 93d Cong., 2d Sess. 62 (1974) . . 17

48 U.S.C. § 731 .............................................................. 2

IV

PAGE

Commentaries

Applewhite, A New Design for Recruitment of

Blacks into Health Careers, 61 A.J.P.H. 202 (1971) 21

Association of American Medical Colleges, The Med

ical School Admissions Process—A Revietv of the

Literature 1055-76 (1976) ......................................... 3,18

Bartlett, Medical School and Career Performances of

Medical Students with Low MCAT Test Scores, 42

J. Med. Ed. 231 (1967) ........................................ 19

Blaxall, Minority Students in Health Professional

Schools: Progress is Being Made, 3 The Black Bag

81 (1974) ...................................................................... 8

Caress and Kossy, The Myth of Reverse Discrimina

tion: Declining Minority Enrollment in New York

City’s Medical Schools (Health Policy Advisory

Center 1977) ................................................................ 3

Ceithaml, Appraising Non-intellectual Characteris

tics, 3 J. Med. Ed. 47 (1957) ................................... 20

Comment, Developments in the Law—Equal Protec

tion, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1065 (1969) ......................... l i

Cooper, The Government Concern Regarding Post-

Graduate Training and Health Care Delivery, 36

Am. J. Cardiology 555 (1975) ................................. 21

Gough, Evaluation of Performance in Medical Train

ing, 39 J. Med. Eel. 679 (1964) ................................. 19

Hammonds, Blacks in the Urban Health Crisis, 66 J.

N at’l Med. A ss’n 226 (1974) ................................... 18

Herrera, Chicago Health Professionals, Agenda

(Winter, 1974) .......................................... 21

Jackson, The Effectiveness of a Special Program for

Minority Group Students. 47 J. Med. Ed. 620

(1972) ' ............. 21

Lurie and Lawrence, Communication Problems Be

tween Rural Mexican Patients and their Physi

cians: Description of a Solution, 42 Am. J. Ortho-

Psychiatry 77 (1972) ................................................ 18

V

PAGE

Commentaries (Cont.)

Madsen, “ Society and Health in the Lower Rio

Grande Valley,” in J . PI. Burma, ed., Mexican-

Americans in the U.S.: A Reader (1970) ............. 18

Marshall, Margolis, and Joseph, Impact of a Reten

tion Program for Disadvantaged Medical Students

upon the Medical School, 50 J. Med. Ed. 805 (1975) 7

Marshall, Minority Students for Medicine and Haz

ards of High School, 48 J. Med. Ed. 134 (1973) . . 19

National Board on Graduate Education, Minority

Group Participation in Graduate Education, 152

(1976) ................................................................. 3,19

Nelson, Bird and Rogers, Educational Pathway

Analysis for the Study of Minority Representation

in Medical School, 46 J. Med. Ed. 745 (1971) . . . . 19

New York State Department of Labor, Labor Re

search Report No. 1, Occupational Trends of Ne

groes and Puerto Ricans in New ¥ ork State 1960-

1970 (1975) .................................................................. 17

C. E. Odegaard, Minorities in Medicine 1966-76

(1977) .......................................................................... 2,3

Price, et al., Measurement and, Predictors of Physi

cian Performance, (University of Utah Press

1971) ....................... ................... ' ............................... 19

Rhoades, et al., Motivation, Medical School Admis

sions and Student Performance, 49 J. Med. Ed.

1119 (1974) ................................................................ 19

Simon, and Covell, Performance of Medical Students

Admitted Via Regular Admission-Variance Routes,

50 J. Med. Ed. 237 (1975)........................................... 7

Smith, Foreign Physicians in the United States, 66 J.

N at’l Med.' A ss’n 77 (1974) ....................................... 17

Turner, Helper and Kriska, Predictors of Clinical

Performance, 49 J. Med. Ed. 338 (1974) ............. 19

VI

PAGE

Commentaries (Cont.)

United States Commission on Civil Rights, Puerto

Ricans in the Continental United States: An Un

certain Future (1976) .............................................. 2, 21

H. Wechsler, Principles, Politics and Fundamental

Law (1961) .................................................................. 11

Weymouth and Weigin, Pilot Programs for Minority

Students: One School’s Experience, 51 J. Med.

Ed. 668 (1976) .......................................................... 19

Whittico, The Medical School Dilemma, 61 A.M.A.J.

185 (1969) .................................................................. 19

Other

United States Bureau of the Census, Population

Characteristics, “Persons of Spanish Origin in the

United States: March 1975,” Series P-20, No. 290

(Feb. 1976) ................................................................ 2

United States Department of Labor, Bureau of

Labor Statistics, A Socio-Economic Profile of

Puerto Rican Neiv Yorkers (1975) ......................... 3

IN THE

diqjnmu' (tart nf ftp? Inttrft Stairs

October Term, 1976

No. 76-811

--------------------o-------------- ------

T h e R egents of the U niversity of California,

Petitioners,

v.

A llan B akke,

----------o--------

Respondent.

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

The Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education

Fund and Aspira of America

Interest of the Amici'

Tlie Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund,

Inc. exists to secure the civil rights of Puerto Ricans

through litigation and education. Aspira of America, Inc. is

a national organization of Puerto Rican educators and

students which was established for the purpose of insuring

equal educational opportunity for Puerto Ricans and other

Hispanic persons. Both organizations, with headquarters

in New York City, have worked to foster affirmative action

programs for Puerto Ricans interested in pursuing pro

fessional education.

1 Letters of the petitioners and respondent giving their consent to

file this brief have been filed with the Clerk of this Court.

2

Hispanic persons constitute the second largest minority

in this country. As of 1975, about one of every twenty per

sons in the continental United States was of Spanish origin.

Among this Hispanic population, nearly 1.7 million persons

were Puerto Ricans residing on the mainland.2

Puerto Rican college graduates, who will be directly

affected by this Court’s ruling on the merits, have long

been the victims of educational deprivation. They have been

aptly described as survivors—the “ few who have survived

the public schools, who have overcome the language barrier,

who have somehow found the money, or who have convinced

their families to forego the income they could produce. . . . ” 3

However, educational deprivation has taken its toll.

Puerto Rican college graduates who are intent on attending

professional school often do not have scholastic grade-point

averages on a par with those of non-minority students.4

The failures of the educational system to which Puerto

Ricans have particularly been victim often have had an im

pact as well on their performance on standardized admis

sions examinations for professional schools.5

In the last few years, factors other than the numerical

measures traditionally so heavily relied on have come to

be considered in the admission process. In part because

1 ‘ the applicant pool of today includes an abundant number

2 United States Bureau of the Census, Population Characteristics,

“Persons of Spanish Origin in the United States: March 1975,” Series

P-20, No. 290 (Feb. 1976), at 3. United States citizenship was con

ferred upon all Puerto Ricans in 1917 by the Jones Act, 48 U.S.C.

§ 731 et seq.

8 United States Commission on Civil Rights, Puerto Ricans in the

Continental United States: An Uncertain Future 123 (1976),

quoting from Hearings before the Senate Committee on Equal Edu

cational Opportunity of the United States Senate, 91st Cor.g., 2d Sess.,

Part 8, “Equal Educational Opportunity for Puerto Rican Children”

(November 1970), at 3797.

4 C.E. Odegaard, Minorities in Medicine, 1966-1976, 112 (1977).

■’ Id. at 112; cf. also, United States Commission on Civil Rights,

Puerto Ricans in the Continental United States: An Uncertain future,

at 127.

3

of students with acceptable MCAT scores and GPA’s, ad

missions committees can now give more attention to lion-

cognitive criteria.” 0 Increasingly, due recognition has been

given to the importance of noncognitive measures in recruit

ing and selecting qualified applicants, especially with re

spect to disadvantaged minority students :

Admissions decisions focus on assessment of in

tellectual potential and academic qualifications.

While the two are closely related, they are not iden

tical, especially in the situation of minority students,

many of whom have experienced socioeconomic and

educational disadvantage.7

Even with recent changes in admissions programs there

has been no enormous influx of minority persons into pro

fessional schools. Indeed, minority enrollment in medical

schools m New York City has declined in recent years,” and

there is today but a handful of mainland Puerto Rican doc

tors.!> The increased numbers of persons admitted to med

ical schools in recent years have overwhelmingly been

non-minority.10

Nonetheless, small but important gains have been made

of late in the numbers of Puerto Rican medical students.11

8 Association of American Medical Colleges, The Medical School

Admissions Process: A Review of the Literature 1955-76 134

(1976).

7 National Board on Graduate Education, Washington, D.C.

Minority Group Participation in Graduate Education 152-153

(1976).

s Caress, B., with Kossy, J., The Myth of Reverse Discrimination:

Declining Minority Enrollment in New York City’s Medical Schools

(Health Policy Advisory Center 1977).

9 See note 24, infra.

luOdegaard, op. cit., at 30.

11 Id; cf. also, United States Department of Labor, Bureau of

Labor Statistics, A Socio-Economic Profile of Puerto Rican New

Yorkers 55 (1975).

4

The 71 admitted in 1975-1976 are not many, but they are a

great many more than the three admitted in 1968-1969, who

represented a scant three one-hundredths of one percent

(.03%) of the total first year medical school population that

year. I t is imperative that what little affirmative action

voluntarily has taken place at the professional school level

to remedy the consequences of discrimination should be un

equivocally approved by this Court.

Introductory Statement

Past discrimination against discrete and insular minori

ties in this country has had a par ticularly devastating impact

on minority access to our system of professional education.

Minority persons have been in large part excluded from

the professions; not coincidentally, minority communities

are critically underserved by those professions. Seeking to

remedy these problems, institutions charged with further

ing the public interest have in recent years adopted policies

in such areas as admissions and employment which are ex

plicitly aimed at neutralizing the effect of past discrimina

tion now. The crucial issue before the Court is whether

these “ affirmative action” efforts, which have begun to pro

duce small but measurable gains toward equal opportunity,

are at odds with the constitutional commands they were

created to implement.

The University of California Medical School at Davis

established a special admissions program in order to open

up professional education to those victimized by past dis

crimination. The University gave some consideration, in

selecting among qualified applicants, to racial and ethnic

background. That much seems beyond doubt, and amici’s

defense of the program has assumed as much. No more

than that, however, can be gleaned from the present record.

Insofar as an assessment of the program may turn

5

on analysis of the extent to which racial and ethnic factors

were considered, this record will not permit so refined a

judgment.

Indeed, rarely has so important a case—one in which

an attempt is made to delimit a state’s right voluntarily

to remedy the consequences of discrimination—come before

the Court on such an incomplete, ambiguous record. It is

uncertain precisely how the program operated. The court

proceeding's below did not touch upon the program ’s justi

fication in prior racial discrimination.12 No evidence was

offered on the demonstrable need today for the program

or as to the inefficacy of alternatives.

The deficiencies in this record were not due to a failed

attempt at proof or the unavailability of evidence. Rather,

they were due to the singular nature of this proceeding:

an applicant to a professional school challenged as “ reverse

discrimination” on racial grounds a program for which he

was ineligible in any event, and the school, anxious to have

an advisory ruling on the validity of the program, joined

in the effort to obtain a prompt ruling on the merits. This

was not a lawsuit marked by the clash of adverse interests

at trial which normally could be relied upon to produce a

complete, well-developed record.13

A decision by this Court as to the validity of the special

admissions program may have wide impact on the civil

rights of minorities for years to come. For the Court to

12 The complete lack of evidence of past discrimination should not

be surprising. There was no party to this litigation in whose interest

it would have been to present such evidence. It would clearly have

been embarrassing if not detrimental to the University to produce

evidence or even concede that it had discriminated against minorities

in the past. Certainly, Bakke would not have presented such evidence.

12 Telling evidence of the lack of adversariness is the “stipu

lation” in the California Supreme Court. On appeal from the Superior

Court, the California Supreme Court ruled that the University had

the burden of establishing that Bakke would not have been admitted

to the Davis Medical School in the absence of the special admissions

6

reach the merits on this scant record will preclude a fully

informed decision. I t should therefore decline to do so.

Nonetheless, this amicus curiae brief is addressed pri

marily to the merits of the underlying issues, for these are

the concerns which prompted its filing.

A R G U M E N T

THE SPECIAL ADMISSIONS PROGRAM OF THE

DAVIS MEDICAL SCHOOL IS CONSTITUTIONAL.

Increasingly in recent years, institutions affected with

the public interest have come to consider, in connection

with decisions such as whom to admit or employ, the race

and ethnic background of applicants. They have done so

in order to remedy the effects of past discrimination which

either was practiced by or affected those institutions. The

Davis Medical School is among the institutions which have

taken voluntary steps to neutralize the consequences of such

discrimination. Like many other medical schools, it has rec

ognized the need to increase minority participation in the

medical profession and to improve the quality of medical

services provided to minority communities. In utilizing

admissions criteria that are sufficiently flexible to permit

some consideration to be given to applicants from disadvan-

program. Accordingly, in its September 16, 1976 order the Supreme

Court remanded the issue to the trial court. However, it did not

intimate that the evidence presented by the University at trial was

insufficient; it merely stated that the evidence must be evaluated

in light of the different burden (18 Cal. 3d at 64, 553 P.2d at

1172, 132 Cal. Reptr. at 700). In an attempt to confer jurisdic

tion, the University attached to its petition for rehearing in the Cali

fornia Supreme Court a “stipulation” which, contrary to the evidence

and the prior position pressed by the University at trial, purports to

concede that the University could not meet this burden. On the basis

of this “stipulation,” the California Supreme Court then ordered

Bakke’s admission. Regardless of the University’s motivation for

signing the “stipulation” and the effect given to it by the California

Supreme Court, it must be treated as a nullity by this Court. United

States v. Felin & Co., 334 U.S. 624 (1948); Swift & Co. V. Hocking

Valley Ry. Co., 243 U.S. 281 (1917).

7

taged and minority backgrounds,11 the University has

adopted the position taken by the Association of American

Medical Colleges (AAMC) that minority students “ bring to

the profession special talents and views which are unique

and needed.” AAMC, Statement on Medical Education of

Minority Group Students, December 16, 1970.

There is no indication that in taking these additional

factors into account the University planned to admit or

ever did admit a fixed number of minority persons regard

less of their qualifications. Rather, there is every indication

that all of those admitted to the special admissions program

were fully qualified.15 This program did not effect discrimi-

1 * The validity of traditional academic criteria is an issue not be

fore this Court. The majority below reasoned, on the basis of the

rule enunciated in Washington V. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), that

a discriminatory purpose could not be inferred solely from the fact

that traditional academic criteria may have a disproportionate impact

on minority group applicants. 18 Cal. 3d at 60, 553 P.2d at 1169,

132 Cal. Rptr. at 697. The majority, however, recognized that

neither party before it had an interest in raising such a claim. Id. at

n.29. Plainly, it would be arbitrary for the University to rely solely

on objective criteria which substantial research has shown to have

limited predictive value. Washington cannot be read as preventing

the University from adjusting its admissions procedures to compen

sate for the bias in a test instrument which for administrative and

other reasons the University has decided not to abandon altogether.

15 The limited amount of evidence available indicates that minority

persons admitted to medical schools via affirmative action programs

were rated as performing at approximately the same levels of com

petence as those admitted under regular admissions programs. See

Marshall, Margolis, and Joseph, Impact of a Retention Program for

Disadvantaged Medical Students upon the Medical School Com

munity, 50 J. Med, Ed. 805 (1975); Simon, and Covell, Perform

ance of Medical Students Admitted via Regular Admission-Variance

Routes, 50 J. Med. Ed. 237 (1975). Physicians are possessed of

many qualities that traditional testing techniques cannot and perhaps

will never be able to measure. Exclusive reliance on paper creden

tials would almost certainly exclude some of the most talented

majority as well as minority applicants. To avoid this result, educa

tional institutions have traditionally been accorded wide latitude in

considering academic and non-academic criteria for all applicants.

Given the lack of precision of the traditional academic measurements

as predictors of performance in medical school, and the likelihood

8

nation, in reverse or otherwise; rather, it neutralized the

effects of past discrimination. The University’s considera

tion of race and ethnic origin in selecting among otherwise

qualified applicants thus amounted not to giving a “ pref

erence” to certain applicants but to expanding the criteria

considered in making an admissions decision because the

ones formerly employed were deficient—deficient as to all

students, but especially as to minority students.18

A. I t Is P e rm is s ib le F o r th e U n iv e rs ity to C o n s id e r

E th n ic a n d R a c ia l B a c k g ro u n d As O n e o f th e

M any F a c to rs in S e lec tin g A m o n g Q u a lified A p p li

ca n ts F o r A d m iss io n .

This Court has never declared that under the Constitu

tion all classifications based partially upon race or ethnic

status are presumptively “ suspect.” Indeed, on several

occasions this Court has upheld the benign use of race-con

scious remedial techniques, Franks v. Bowman Tramp. Co.,

424 U.S. 747, 774-5 (1976) ; Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 25 (1971) ; United States v.

Montgomery County Board of Education, 395 U.S. 225

(1969), even where these were part of a policy administered

by nonjudicial government agencies. United Jewish Or

ganizations of Williamshurgh, Inc. v. Carey, 45 U.S.L.W.

4221 (March 1, 1977); Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 554

(1974). In the employment discrimination context, for ex-

that such criteria have a built-in cultural bias, see Blaxall, Minority

Students in Health Professional Schools: Progress is Being Made, 3

The Black Bag 81 (1974), adjustments in the admissions process

and resort to additional criteria which reflect an applicant’s qualifica

tions are entirely justified, if not required.

18 In the strictly logical sense, expanding the criteria considered

could be regarded, all other things being equal, as the giving of a

preference by comparison with the procedures formerly used. But

that view, of course, begs two critical questions: whether the cri

teria formerly employed were constitutionally exclusive or exhaustive

of all others, and whether in practice all other things were equal.

9

ample, considerations of race, ethnicity or sex in hiring

have been approved as necessary to fulfill a national policy

of eradicating the effects of previous discrimination.17

Assignments by race have likewise become a well-estab

lished device for desegregating the nation’s school sys

tems.18 In these and other areas in which there has his

torically been discrimination, the power of courts to employ

racially, ethnically and sexually based remedies has come

to be well established.19

17 Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976); Albe

marle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975); Arnold v. Ballard,

12 Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH) f 11,000 (6th Cir. 1976); Patterson v.

American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257 (4th Cir. 1976); United

States v. International Union of Elevator Constructors, Local 5, 538

F.2d 1012 (3rd Cir. 1976); Rios v. Enterprise Association Steam-

fitters Local 638, 501 F.2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974); United States v.

United Brotherhood of Carpenters & Joiners, Local 69, 457 F.2d

210 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 851 (1972); United States v.

Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir.), cert, denied, 404

U.S. 984 (1971); Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971),

cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972); Local 53, International Ass’n of

Meat & Frost Insulators & Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d

1047 (5th Cir. 1969).

18E.g„ Keyes v. School District No. I, 413 U.S. 189 (1973);

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971); Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

10 The Court has been keenly aware that the impact of the same

remedial devices it has sanctioned for minorities has been both sub

stantial and very often difficult for majority persons to accept. See,

e.g., Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. at 775-78; Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. at 26-27. The

courts have by no means been insensitive to these concerns, but have

uniformly resolved that

a sharing of the burden of the past discrimination is presump

tively necessary [and] is entirely consistent with any fair char

acterization of equity jurisdiction, particularly when considered

in light of our traditional view that “[ajttainment of a great

national policy . . . must not be confined within narrow canons

for equitable relief deemed suitable by chancellors in ordinary

private controversies.” Phelps Dodge Corp. v. NLRB, 313 U.S.

at 188. . . .

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. at 777-78.

10

Decisions of this Court establish a fundamental, consti

tutional distinction between racial classifications which in

vidiously discriminate and those which have the benign

remedial effect, grounded in the language and purpose of

the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments,20 of promo

ting “ those fundamental rights which are the essence of

civil freedom.” Civil Rights Cases. 109 U.S. 3, 22 (1883).

The Equal Protection Clause does not compel the applica

tion of an “ exacting” standard of review merely because

the special admissions program employed a classification

based on race and ethnic origin.

The central purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was

to preclude the states from treating recently freed blacks

in a discriminatory manner. The Court initially took the

position that the Amendment’s only purpose was to protect

the constitutionally emancipated slaves, Slaughter-House

Cases, 83 U.S. 36, 81 (1873), and termed as “ suspect”

classifications based upon “ race” which discriminated

against blacks. See, e.g., McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S.

184 (1964) ; Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954). As equal protection doctrine has evolved, this

special protection of the Fourteenth Amendment has been

extended to other victimized minorities in positions com

parable to that of blacks. See, e.g., Graham v. Richardson,

403 U.S. 365 (1971); Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475

(1954) ; Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948) ; Yick Wo

v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

The Court has applied the “ strict scrutiny” standard in

reviewing racially based classifications only on behalf of

individuals or groups that historically have suffered from

pervasive discrimination and thus are particularly vulner

able to the damaging effects of a racial classification. In

20 The history of these amendments is thoroughly analyzed in

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968). See also,

Brief of The Board of Governors of Rutgers, the State University of

New Jersey, et al., submitted as amici curiae.

11

determining whether application of such a stringent stand

ard is appropriate, this Court has looked at whether

11Jlie system of alleged discrimination and the class

it defines have . . . the traditional indicia of suspect

ness : the class is . . . saddled with such disabilities,

or subjected to such a history of purposeful unequal

treatment, or relegated to such a position of political

powerlessness as to command extraordinary protec

tion from the majoritarian political process.

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411

U.S. 1, 28 (1973). See also, Examining Board of Engineers,

Architects and Surveyors v. Flores de Otero, 426 U.S. 572

(1976); Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 TJ.S. 677 (1973).21

The persons or groups on whose behalf the “ strict

scrutiny” standard has been applied share three significant

characteristics. First, they labor under the continuing

effects of previous discrimination and deprivation. Second,

they share immutable characteristics, those of race or na

tional origin, which have been used to stigmatize and set

them apart from members of the majority group. See e.g.,

Comment, Developments in the Laiv—Equal Protection, 82

Harv. L. Rev. 1065, 1173-74 (1969). Finally, they histori

cally have been powerless within the political arena. Wechs-

ler, “ Toward Neutral Principles of Constitutional Law,” in

H. Weehsler, Principles, Politics and Fundamental Law

3, 45 (1961).

None of the factors which have led the Court to treat

certain classifications as constitutionally “ suspect” is pres-

21 For example, the Court has found that “. . . Hispanos con

stitute an identifiable class for purposes of the Fourteenth Amend

ment,” and that “ ‘[ojne of the things which the Hispano has in

common with the Negro is economic and cultural deprivation and

discrimination,’ ” thus calling for stricter judicial scrutiny of state

action. Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S 189 197-98

(1973).

12

ent here. Majority applicants not admitted to the medical

school were not part of a class suffering from the continu

ing effects of discrimination and deprivation. Nor could it

be said they were politically powerless, or that the actions

of the University which affected them were motivated by a

discriminatory intent. The obvious remedial nature of the

admissions policy, and the fact that it was designed and

implemented by governmental bodies not dominated by

minorities, further negate any possibility that the Uni

versity was motivated by racial animus toward majority

group applicants. Compare United Jewish Organisa

tions of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, 45 U.S.L.W. at 4230

(Brennan, J., concurring) with McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail

Transp. Co., 427 U.S. 273 (1976).22

Moreover, the majority below conceded the special ad

missions program did not cast a stigma on non-minority

applicants on account of their race. 18 Cal.3d at 51-52, 553

P.2d at 1163, 132 Cal. Rptr. at 691. There is no evidence to

suggest that it had the purpose or effect of dislodging any

recognizable subgroup of non-minorities or that the pro

gram had a disproportionate impact on any such subgroup.

The special admissions program did not bring about under

representation of the white race generally, nor did it have

22 Increasingly in recent years this Court has determined that in

order to render a racial classification suspect there must be some

finding that the classification was motivated by an “invidious dis

criminatory purpose.” Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corporation, 45 U.S.L.W. 4073, 4077 (January 11,

1977); Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 242 (1976). Although

designed to give some consideration to race, the special admissions

program did not create a racially “invidious” procedure because

there was no purpose systematically to exclude or segregate; the

program rather was intended to neutralize the discriminatory impact

of traditional selection criteria. Unlike the complainant in McDon

ald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co., 427 U.S. 273 (1976), Bakke did

not allege and could not prove that the University’s action which

affected him reflected a racial animus.

13

the effect of “ fencing out” the white population from a

professional education. At best, the evidence suggests that

any burdens imposed by the special admissions program

have been shared by those who have not been disadvantaged,

both minority and non-minority alike. United Jewish Or

ganizations of Williamshurgh, Inc. v. Carey, 45 U.S.L.W.

at 4227. In sum, the special admissions program “ repre

sented no racial slur or stigma with respect to whites or any

other race.” Id.

The program certainly did not stigmatize its intended

beneficiaries. It grew out of an acute awareness among edu

cators and administrators that existing selection criteria

were inadequate for all applicants. In expanding those cri

teria, the University, as have others, has recognized that its

previous ability to make comparisons among applicants was

imprecise at best. Thus, any perception that minority stu

dents, as judged by the standards previously relied on, are

“ less qualified” has and always has had little basis in real

ity. If anything, it is the failure to institute a program which

considers the effects of past discrimination that has a stig

matizing effect on minorities, because underrepresentation

of minorities in a professional school may be perceived by

them and others as reflective of lesser ability. Further, the

voluntary, affirmative character of the University’s pro

gram in any event makes it less likely that minorities will

be stigmatized than would a judicial decree granting race

conscious remedial relief, perhaps after a lengthy, strenu

ously contested controversy.

Such voluntary undertakings deserve constitutional

sanction. The Court has recognized that nonjudicial gov

ernmental bodies have an authority to remedy constitutional

violations which is broader than the power conferred on the

judiciary. See, Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 653

(1966). Indeed, this authority includes the power to take

14

remedial action reaching beyond the immediate effects of

prior discriminatory practices. United Jewish Organiza

tions of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, 45 U.S.L.W. at 4226.

In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U.S. at 16, for example, this Court noted:

School authorities are traditionally charged with

broad power to formulate and implement educational

policy and might well conclude, for example, that in

order to prepare students to live in a pluralistic

society each school should have a prescribed ratio of

Negro to white students reflecting the proportion for

the district as a whole. To do this as an educational

policy is within the broad discretionary powers of

school authorities; absent a finding of a constitu

tional violation, however, that would not be within

the authority of a federal court.

Thus, as a matter of precedent and of policy it would be

error to hold that the limitations of equity jurisdiction are

applicable to nonjudicial governmental bodies. A contrary

rule would vest the power to remedy discrimination exclu

sively in courts and usurp the authority of legislatures and

executive agencies. Clearly such a result would work coun

ter to the purposes of the Reconstruction Amendments,

the civil rights statutes, and the decisions of this Court.

In conclusion, the considerations employed in the Uni

versity’s admissions process did not create suspect clas

sifications and were not in any sense invidiously discrim

inatory. This Court in evaluating the special admissions

program should therefore apply the traditional standard of

review under the Equal Protection Clause. It need only

consider whether the University’s program and the classifi

cations employed are rationally related to achieving a

15

legitimate governmental purpose. See, e.g., Kahn v. Shevin,

416 U.S. 351 (1974).

Amici will argue in the following point that even if the

Court does apply the “ strict scrutiny” standard, it is

clear that the program was necessary to achieve a com

pelling state interest. Because that argument necessarily

involves the same issues as are involved in showing that the

program passes muster under the lesser burden of constitu

tional justification argued for here, amici defer more ex

tended discussion of that matter until the next point.

B. T h e U n iv e rs ity ’s S p ec ia l A d m iss io n s P ro g r a m (Fur

th e rs C o m p e llin g S ta te In te re s ts in R e m e d y in g th e

C o n seq u en c es o f D isc r im in a tio n a n d S e rv in g th e

th e U n m et H e a lth N eeds o f M in o rity C o m m u n itie s .

California’s special admissions program withstands

constitutional examination even under the “ strict scrutiny”

standard. The program embodies and seeks to satisfy two

basic compelling state interests: increasing minority par

ticipation in the medical profession in order to remedy the

consequences of past discrimination, and training doctors

likely to serve the needs of critically underserved minority

communities.23 The failure to acknowledge either the legiti-

23 There were other interests served by the program as well. The

dissent below noted one important interest:

fl]n Swann v. Board of Education, supra, 402 U.S. 1, 16, 91

S.Ct. 1267, 1276, the Supreme Court explicitly confirmed that

school authorities are constitutionally empowered to utilize

benign racial classifications to achieve racially balanced schools

“in order to prepare students to live in a pluralistic society.”

The special admission process at issue here, of course, was in

fact implemented for fust such an educational purpose, to pro

vide a diverse, integrated student body in which all medical

students might learn to interact with and appreciate the problems

of all races as to adequately prepare them for medical practice

in a pluralistic society. This educational interest in a diverse

student body is no mere “makeweight”; undergraduate schools

and professional institutions of the highest caliber have long

16

macy of those interests or the appropriateness of attempt

ing to further them through the medical school admissions

process leads some observers mistakenly to characterize

this as a “ reverse discrimination” case. This narrow posi

tion fails to acknowledge the multiplicity of legitimate

interests the state has in the medical school admissions

process at governmentally supported institutions. If, how

ever, these interests are accorded due recognition, even

under the most stringent test applied under the Equal

Protection Clause, the program must be seen as constitu

tionally valid.

The most fundamental interest California has sought to

further through this affirmative action program is remedi

ating the consequences that past discrimination has wrought

on a profession affected with the public interest. Other

groups participating in this litigation have amply demon

strated the extent to which previous discrimination in

education, employment and other areas has lessened the

opportunities for and thus the numbers of minority doctors.

Such discrimination has affected Puerto Ricans particularly

acutely, and the result has been that the numbers of Puerto

Rican doctors on the mainland United States, though not

recognized that the quality of one’s educational experience is

“affected as importantly by a wide variety of interests, talents,

backgrounds and career goals [in the student body] as it is by

a fine faculty and . . . libraries [and] laboratories . . .” (65

Official Register of Harvard U. No. 25 (1968), pages 104-105)

Thus, given the race and ethnic background of the great majority

of students admitted by the medical school, minority applicants

possess a distinct qualification for medical school simply by

virtue of their ability to enhance the diversity of the student

body.

18 Cal. 3d. at 85, 553 P.2d at 1157, 132 Cal. Rptr. at 715 (emphasis

added).

17

known precisely, is by all accounts exceedingly small.24

This Court lias repeatedly recognized that remedying the

consequences of past discrimination is a governmental

concern of the highest order. See, e.g., Hills v. Gautreaux,

425 U.S. 284 (1976) ; Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) ;

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968). Plainly

the most certain way—indeed the only way—to satisfy that

interest is to determine to admit greater numbers of quali

fied minority persons to medical schools.

The other, equally compelling governmental interest

which the program has sought to further is increasing the

number of doctors who will dedicate some or all of their

professional efforts to improving the delivery of medical

help to the chronically underserviced communities of the

poor. Provision of adequate health services is beyond

doubt a governmental concern of the highest order. See,

e.g., Memorial Hospital v. Maricopa County, 415 U.S. 250,

259-261 & n.15 (1974).

The inadequacy of medical services generally available

to minority persons in disadvantaged communities, as well

as the failure of efforts to involve licensed physicians to a

greater extent in serving those communities, is well known.

As a Senate Report recently stated, “ [pjrivate physicians

are as hard to find in some neighborhoods of New York as

in backward rural counties of the South.” S. Rep. No. 93-

1133, 93d Cong., 2d Sess. 62 (1974). This problem is par-

24 Data compiled from federal government agencies by the Bureau

of the Census are inadequate to determine the number of Puerto

Rican doctors. The classification category used by these agencies is

“Spanish-surnamed” and includes not only a predominant number of

Mexican-Americans but also more than seven thousand Filipinos.

See Smith, Foreign Physicians in the United States, 66 J. Natl. Med.

Ass’n 77 (1974). In New York, as of 1970 there were 146 Puerto

Rican physicians (M.D.’s and osteopaths) out of a total of 38,269

physicians in the state—approximately one-third of one percent.

New York State Department of Labor, Labor Research Report No.

1. Occupational Trends of Negroes and Puerto Ricans in New York

State 1960-1970, 13 (1975).

18

ticularly acute for language-minority persons. A high per

centage of Puerto Ricans speak only or largely Spanish,

and thus not even all of the limited medical resources avail

able to other minorities are available to them.26

These compelling governmental interests—enhancing

educational opportunities for disadvantaged minorities in

order to remedy the consequences of previous discrimina

tion, and providing for the currently unmet health needs of

impoverished minority communities'—have been inade

quately if at all furthered by existing school admissions

policies.20 Those who would deny the University the ability

to adopt admissions policies designed to advance these social

25 It is fairly evident that language or other barriers may be in

jurious to the patient’s receiving the best advice and assistance from

a doctor. See Hammonds, Blacks in the Urban Health Crisis, 66 J.

Nat’l. Med. Ass’n 226 (1974); Lurie and Lawrence, Communi

cation Problems Between Rural Mexican Patients and their Physi

cians: Description of a Solution, 42 Am. J. Ortho-Psychiatry 77

(1972). Diagnostic ability, among other things, may suffer. See

Letter to the Editor, 295 N.E.J. Med. 293 (July 29, 1976). Ex

plaining a medical problem is a complex task that requires greater

linguistic facility (e.g., ability to describe symptoms precisely, and

perhaps even to understand some technical terminology) than do

most other personal contacts. Furthermore, speaking to a profes

sional person in other than one’s native language about a physical

or mental problem is a stressful, anxiety-producing interaction that

may even impair further a person’s normal ability to speak in English.

See Madsen, “Society and Health in the Lower Rio Grande Valley,”

in J.H. Burma, ed., Mexican-Americans in the U.S.: A Reader

(1970).

20 There has been an extraordinary increase in the number of

applicants to medical school. In 1965, the number of applicants and

the number of applications submitted to medical schools totaled

18,703 and 87,111, respectively. In 1975, the number of applicants

increased by 126% to 42,303 and the number of applications in

creased by 320% to 366,040. Association of American Medical

Colleges, The Medical School Admissions Process— A Review of the

Literature 1955-76, 12. If existing admissions criteria were relied

on exclusively there would be few if any minority admissions because

relatively few minority persons apply. Of the 42,303 applications

submitted in 1975, 2288 were submitted by Black-Americans, 132 by

American Indians, 427 by Mexican Americans and 202 by mainland

Puerto Ricans. Id. at 144.

19

concerns have sought to focus on the narrower, emotionally

laden issue of whether applicants were admitted according

to strict rank order of grades and test scores. Judging

applications exclusively by these measures, which have been

so heavily relied upon for so long, has in the view of some

come to be equated with so fundamental an American con

cept as the merit system. The equation is spurious.

I t has increasingly been recognized that the conventional

academic credentials, the Medical College Aptitude Test

(MOAT) and the Grade Point Average (GPA), reveal rela

tively little about the abilities of most if not all applicants.

These traditional criteria may measure certain skills that

are important for the study of medicine—and even that

point is far from certain. Their correlation with and ability

to predict competence in professional practices is yet more

dubious.27

27 There is substantial doubt about whether traditional criteria

yield measurements that are predictive. See, e.g., National Board on

Graduate Education, Minority Group Participation in Graduate

Education 152-153 (1976). Numerous scholarly studies have ques

tioned whether objective criteria accurately predict academic and

professional performance of minority applicants and whether paper

academic credentials provide an equitable basis for comparison. See

Weymouth and Weigin, Pilot Programs for Minority Students: One

School’s Experience, 51 J. Med. Ed. 668 (1976); Marshall, Minority

Students for Medicine and the Hazards of High School, 48 J. Med.

Ed. 134 (1973); Nelson, Bird, and Rogers, Educational Pathway

Analysis for the Study of Minority Representation in Medical School,

46 J. Med. Ed. 745 (1971); Whittico, The Medical School Dilemma,

61 A.M.A.J. 185 (1969). In addition, research has suggested that

objective criteria are of doubtful utility as predictors of majority

student performance as well. See, e.g., Turner, et al., Predictors of

Clinical Performance, 49 J. Med. Ed. 338 (1974) (low correlation

between MCAT scores and clinical medical school performance);

Bartlett, Medical School and Career Performances of Medical Stu

dents with Low MCAT Test Scores, 42 J. Med. Ed. 231 (1967) (low

MCAT not significantly related to class rankings, academic warnings,

academic honors, internship appointments, faculty appointments and

later careers). See also, Price, et al., Measurement and Predictors

of Physician Performance (University of Utah Press 1971); Rhoades,

et al., Motivation, Medical School Admissions and Student Per

formance, 49 J. Med. Ed. 1119 (1974); Gough, Evaluation of Per

formance in Medical Training, 39 J. Med. Ed. 679 (1964).

20

The attempt to equate reliance on grades and test scores

with the use of the merit system in admissions policies also

does not comport with historical realities. Medical schools

have never based their admissions decisions solely on aca

demic criteria.28 Professional institutions entrusted with

the responsibility for making decisions that greatly affect

the public interest have always reserved to themselves the

right to use admissions decisions to further legitimate poli

cies of the institution and the profession. For example,

some medical schools have sought to admit applicants who

will bring diversity and distinction because of special inter

ests or sensitivities; if an applicant expresses an interest in

becoming a family physician, the University, like many

institutions, will weigh this heavily because it recognizes

serious, unmet needs in this area.

Similarly, many medical schools’ admissions criteria

have, because of statutory law or state policy, traditionally

accorded some significance to the residence or background

of applicants in order to further legitimate social goals.29

California residents who express an interest in returning

to areas of the state which currently are not adequately

served by the profession, especially in Northern California,

are given special consideration. Many medical schools have

determined that this type of practical approach enhances

the possibility that underserved areas will be adequately

staffed by doctors.80

28 Ceithaml, Appraising Non-intellectual Characteristics, 3 J. Med.

Ed. 47, 53 (1957).

29 See Transcript of Superior Court proceedings, at 65. Fre

quently these preferences for state residents are expressed in terms

of a quota. See, e.g., Clark v. Redeker, 406 F.2d 883 (8th Cir,),

cert, denied, 396 U.S. 862 (1969).

80 Other examples include consideration of whether the applicant

is a relative of an alumnus or alumna of the institution (presumably

to encourage and solidify support for the institution among its gradu

ates) or is the spouse of a current student (a policy the University

followed, presumably to encourage practice as a family or to avoid

dividing professional families during the training of the spouses, see

Transcript of Superior Court proceedings, at 183).

21

A similar assumption for similar reasons is made in

recruiting minority persons for the special admissions pro

grams. The consideration of the minority status of some

applicants is a measure reasonably calculated to increase

medical services to poorly served minority communities.

It is sensible to assume, as the University did in the absence

of contrary evidence, that minority doctors from disadvan

taged backgrounds are more likely than others to be em-

pathetic to the needs and problems of these communities

and thus to want to serve them.31 This assumption is par

ticularly valid in the case of Spanish-speaking minorities.

Regardless of where he or she chooses to practice medicine,

a doctor from the Spanish-speaking minority community is

an important asset to the large numbers of Spanish-domi

nant persons in this country.32

By correcting the deficiencies in its admissions pro

cedures, which had perpetuated the effects of discrimination

at earlier educational levels and had restricted access of

racial minorities to the profession, and by developing* new

procedures for selecting qualified minority applicants, the

University has chosen a precise, direct means of achieving

the state’s compelling goals. Indeed, in light of the urgent

need for swift remedies, the special admissions program is

the least restrictive method of accomplishing the desired

31 See e.g., Cooper, The Government Concern Regarding Post-

Graduate Training and Health Care Delivery, 36 Am. J. Cardiology

555 (1975); Herrera, Chicano Health Professionals, Agenda (Win

ter, 1974), at 10-11; Jackson, The Effectiveness of a Special Pro

gram for Minority Group Students, 47 J. Med. Ed. 620 (1972);

Applewhite, A New Design for Recruitment of Blacks into Health

Careers, 61 A.J.P.H. 202 (1971).

32 Spanish is the mother tongue of 83% of mainland Puerto

Ricans. 72% usually speak in Spanish at home. The United States

Commission on Civil Rights, Puerto Ricans in the Continental United

States: An Uncertain Future 32 (1976).

22

objectives.33 Alternatives for attaining the same objectives

that were suggested by the California Supreme Court, such

as expanding recruitment programs and focusing remedial

efforts on the primary and secondary school levels, are de

sirable of themselves but do not insure effective and prompt

solutions. Expanded recruitment has been a central element

of affirmative action programs in recent years, but recruit

ment by itself is not a remedy for the effects of past educa

tional discrimination below the professional school level.

Concentrating attention solely on discrimination at these

lower levels of education, though again desirable on its own

merits, will postpone meaningful progress for years.

Measured against alternatives, then, or considered by

themselves, the admissions procedures utilized by the

special admissions program are reasonable and rational

means of attaining the compelling interests implicated here.

In the process of perfecting admissions techniques, other

procedures for accomplishing the desired ends may well

become available. For the present time, however, the pro

gram established by the University is the most realistic

and practical approach. It does not impose an undue burden

on the majority as a whole; majority applicants continue

to receive the vast majority of acceptances. No majority

applicant has been deprived of careful consideration, and

no unqualified minority applicant has been admitted.

33 The California Supreme Court assumed arguendo that the

program served a compelling state interest. It then found that the

University failed to demonstrate “that the basic goals of the program

cannot be substantially achieved by means less detrimental to the

rights of the majority.” 18 Cal. 3d at 53, 553 P.2d at 1165, 132

Cal. Rptr. at 693. The imposition of so heavy a burden of justifica

tion on the University was improper. Such a burden is only appli

cable in the presence of “invidious” discrimination or a denial of a

fundamental interest. San Antonio Independent School District v.

Rodriguez, 411 U.S. at 40.

23

Most importantly, the special admissions program has

been demonstrated to be necessary and effective and

“ promises realistically to work now.'’’ Green v. County

School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 439 (1968). The achievement

of so compelling a goal as the eradication of the continuing

effects of past discrimination cannot be delayed on the

speculation that other means to accomplish that goal may

be found tomorrow.

CONCLUSION

The Court should not entertain this case on the

merits. If it does so, the judgment of the California

Supreme Court should be reversed.

Dated: June 7, 1977

R obert H ermann

M.D. T aracido

Puerto Bican Legal Defense

and Education Fund

95 Madison Avenue

New York, New York 1001.6

D ebra M. E venson

B enito R omano

1 Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

H oward C. B tjschman, III

Willkie Farr & Gallagher

1 Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

Of Counsel.

-