Griffith v. Kentucky Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Griffith v. Kentucky Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners, 1985. 6138f1b8-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5add60c9-bc1f-4587-a672-220afd4cf176/griffith-v-kentucky-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-petitioners. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

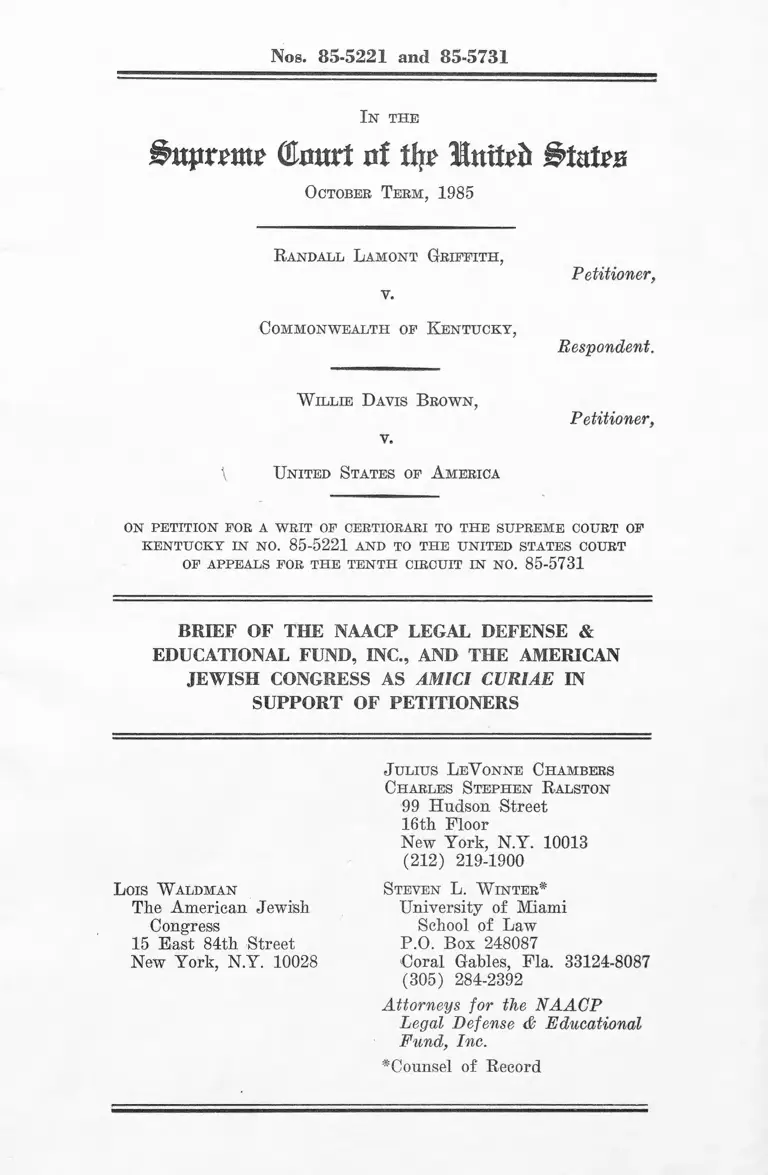

Nos. 85-5221 and 85-5731

I n t h e

i ’upmtu' (ftmart of % llnxtih i&tntvB

October Term, 1985

R andall Lamont Griffith ,

v.

Commonwealth of Kentucky,

W illie Davis Brown,

v.

United States of A merica

Petitioner,

Respondent.

Petitioner,

on petition for a writ of certiorari to the supreme court of

KENTUCKY IN NO. 85-5221 AND TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR TPIE TENTH CIRCUIT IN NO. 85-5731

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AND THE AMERICAN

JEWISH CONGRESS AS AMICI CURIAE IN

SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

L ois W aldman

The American Jewish

Congress

15 East 84th Street

New York, N.Y. 10028

J ulius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Steven L. W inter*

University of Miami

School of Law

P.O. Box 248087

Coral Gables, Fla. 33124-8087

(305) 284-2392

Attorneys for the NAACP

Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc.

^Counsel of Record

QUESTION PRESENTED

What should be the extent of the

retroactive application given the decision

in Batson v. Kentucky. 476 U.S. ___, 90

L.Ed.2d 69 (1986)?

Cases: Page

Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38

(1980) 18-19,21

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S.

625 (1972) 2,29

Allen v. Hardy, ___ U.S. ___,

No. 85-6593 (1986) 10

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp.,

429 U.S. 252 (1977) 28-29

Arsenault v. Massachusetts,

393 U.S. 5 (1968) 12

Barclay v. Florida, 463 U.S. 939

(1983) 34

Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S.

187 (1946) 24

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. ___,

90 L.Ed.2d 69 (1986) passim

Blackburn v. Alabama,361 U.S. 199 (1960) ..... 12

Bob Jones University v. UnitedStates, 461 U.S 574 (1983) ... 27

Brown v. Louisiana, 447 U.S. 323

(1980).......... 7,8,22,24-25,26

Caldwell v. Mississippi, 472 U.S.

___, 86 L.Ed.2d 231 (1985) ... 33

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S.

482 (1977) .................. 29

iv

Cases: Pacro

Davis v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 122(1976) 36

Desist v. United States, 394 U.S.244 (1969) 10

DeStefano v. Woods, 392 U.S. 631

(1968) 25,26

Engle v. Isaac, 456 U.S. 107

(1982) 32

Esquivel v. McCotter, 791 F.2d

350 (5th Cir. 1986) ......... 32

Evans v. Mississippi,

No. 85-6932, cert, denied.

54 U.S.L.W. 3810 (June 9,

1986) 3,30

Gordon v. United States, No. 85-7726 (11th cir.) ............ 2

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S 153(1976) 35

Hankerson v. North Carolina,

432 U.S. 233 (1977) 21,31,32

Ivan V. v. City of New York,

407 U.S. 203 (1972) ........ 21

Johnson v. New Jersey, 384 U.S.719 (1966) 11

Jones v. Barnes, 463 U.S. 745(1983) g

Keeble v. United States,

412 U.S. 205 (1973) 15

v

Linkletter v. Walker,

381U.S. 618 (1965).........7,10,11,12,37

Mackey v. United States,

401 U.S. 667 (1971) 8,9

McCray v. New York, 463 U.S.

961 (1983) 27

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973) 29

Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore,

439 U.S. 322 (1979) 14

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493

(1972) 18

Shea v. Louisiana, 470 U.S. ,

84 L.Ed.2d 38 (1985) 4,7,11

Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293

(1967) 10

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202

(1965) ...................... 2,5,26,28

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522

(1975) 13-14

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86

(1958) 35-36

Turner v. Murray, 476 U.S. ___,

90 L.Ed.2d (1986) 33,34-35

United States v. Johnson,

457 U.S. 537 (1982) 4,8,12

United States v. The Schooner

Peggy, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 103 4,10(1801) ......................

Cases; Page

vi

Cases: Page

Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U.S. ,

88 L. Ed. 2d 598 (1986) ........ 14,18

Wainwright v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72(1977) 31

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S.

229 (1976) ................ 29

Witherspoon v. Illinois,

391 U.S. 510 (1968) 36,37

Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862

(1983) 33-34

Other Authorities;

G. Allport & L. Postman,

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF RUMOR(1965) 17

Damaska, Presentation of Evidence

and Fact-finding Precision.

123 U.Pa.L.Rev. 1083 (1975)..15-16,19-20

H. R.Rep. No. 1076, 90th Cong.,

2d Sess., reprinted in 1968U.S. CODE CONG. AND AD. NEWS1792 ........................ 14

0. Holmes, COLLECTED LEGAL PAPERS(1920) 14

Johnson, Black Innocence and

the,White Jury. 83 Mich.L. Rev. 1611 (1985) ......... 17

H. Kalven, Jr., & H. Zeisel,

THE AMERICAN JURY (1966).... 19-22,23-24

vii

Authorities: Page

Deposition of Edward J. Peters

(April 12, 1985), in Edwards v.

Thiaoen, Civil Action No.

J83“0566(B)(S.D. Miss.) ..... 12-13

Priest & Klein, The Selection

gI_Pispa.tfig_£QjL. Litigation,13 J. Legal Stud. 1 (1984) ... 9

Priest, The common _Law.Process

and the Selection of EfficientRules. 6 J. Legal Stud. 65

(1977) 9

viii

Nos. 85-5221 and 85-5731

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

RANDALL LAMONT GRIFFITH, PETITIONER

v.

COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY, RESPONDENT

WILLIE DAVIS BROWN, PETITIONER

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF KENTUCKY IN No. 85-5221 AND TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

IN NO. 85-5731

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCA

TIONAL FUND, INC., AND THE AMERICAN JEWISH

CONGRESS AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF

PETITIONERS

INTEREST OF AMICI*

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation

Letters from the parties consenting to

the filing of this brief have been lodged with the Clerk of the Court.

organized under the laws of the State of

New York in 1939. It was formed to assist

blacks to secure their constitutional

rights through the prosecution of lawsuits.

Under its charter, the Fund renders legal

aid to impoverished blacks suffering

injustice by reason of race. For many

years, its attorneys have represented

parties and participated as amicus curiae

before this Court and in the lower state

and federal courts.

The Fund has a long-standing concern

with the exclusion of blacks from jury

service and the impact of that practice on

the criminal justice system. It has raised

jury discrimination claims in appeals from

criminal convictions, see, e.q.. Swain v.

Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965); Alexander v.

Louisiana. 405 U.S. 625 (1972), and

currently represents clients who have been

affected by this practice. See. e.q. .

Gordon v. United States, No. 85-7726 (ilth

2

Cir.) (pending) ; M M . _v, Mississippi, No.

85-6932, cert, denied. 54 U.S.L.W. 3810

(June 9, 1986).

The American Jewish Congress is a

national organization of American Jews

founded in 1918. It is concerned with the

preservation of the security and

constitutional rights of all Americans.

Since its creation, it has vigorously

opposed racial and religious discrimination

in all areas of American life, including

the administration of justice.

3

SHMMAB3L-QE ARGUMENT

At the least, decision in the two cases

before the Court should follow from the

Court's recent retroactivity decisions,

see, e,g,, Shea v. Louisiana, 470 U.S. ___,

84 L.Ed.2d 38 (1985); United States V.

Johnson, 457 u.s. 537 (1982), which apply

new constitutional decisions to all

similarly situated cases still pending on

direct appeal. This approach is strongly

recommended by three considerations: (1) it

promotes predictability in constitutional

adjudication; (2) it strikes a reasonable

balance between the concerns of equity and

stability; and (3) it is rooted in

judicial practice with a pedigree nearly as

old as the Republic itself. See United

States vt The— Schooner Peggy. 5 u.s. (l

Cranch) 103 (1801).

Amici write separately, however, to put

before the Court their views concerning the

broader reach of the decision last Term in

4

Batgojo_v_,__Kentucky. 476 u.s. ___, 90 l .

Ed.2d 69 (1986). The inclusion of blacks

and other minorities on criminal juries is

important not merely for the social values

of participation, legitimacy, and

nondiscrimination. A proper understanding

of what juries do and how they do it leads

inevitably to the conclusion that the

exclusion of blacks has a direct and

demonstrable impact on the actual outcomes

of jury verdicts — that is, on the truth

finding process. Thus, full retrospective

application is called for.

The rule announced in Batson is not, in

its own terms, a "clear break" with past

law. The exclusion of potential jurors

solely on the basis of their race is and

was a grave constitutional wrong in which

no conscientious prosecutor should have

indulged — Swain V. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202

(1965), notwithstanding. Accordingly, the

good faith reliance by prosecutors on past

5

precedent does not weigh in favor of

limited application of the decision in

Batson.

Because of the nature of the sentencing

decision in capital cases, involving as it

does the application of value judgments to

a highly discretionary decision, the

exclusion of blacks and other minorities

has a heightened impact on the decision

making process in those cases. Accordingly,

Batson should be fully retroactive to all

challenges to death sentences imposed or

recommended by juries from which blacks

were improperly excluded.

6

ARGUMENT

I. BECAUSE THE EXCLUSION OF BLACKS AND

OTHER MINORITIES HAS A DIRECT

IMPACT ON A JURY'S DECISION-MAKING THAT RAISES SERIOUS QUESTIONS ABOUT

THE ACCURACY OF THE RESULTING

VERDICT, AND BECAUSE PROSECUTORS'

INVOCATION OF THE PRACTICE WAS NOT IN GOOD FAITH, THE RULE OF BATSON

v, KENTUCKY SHOULD BE RETROACTIVE

" [Resolution of the question of

retroactivity [i]s not automatic[]...."

Brown__v,__ Louisiana, 447 u.s. 323, 327

(1980)(plurality opinion). "Each

constitutional rule of criminal procedure

has its own distinct functions, its own

background of precedent, and its own impact

on the administration of justice...."

Linkletter V, Walker, 381 U.S. 618, 728

(1965). Nevertheless, amici respectfully

submit that the Court should at least

follow its recent practice of holding new

constitutional decisions retroactive to

cases not yet final. See. e.a. . Shea v.

Louisiana. 470 U.S. __ , 84 L.Ed.2d 38

7

(1985); unitsfl...Stakes...v J..._.ijohnsgn, 457 u.s.

537 (1982); supra.

Adherence to this practice serves

several important values. First, it

provides predictability in constitutional

adjudication, avoiding the appearance of

inconsistency and unfairness that results

from the changing contours of retroactivity

doctrine. See United States v. Johnson. 457

U.S. at 547; Mackey v. United States. 401

U.S. 667, 677 (1971) (Harlan, J.,

dissenting). Second, it strikes a

reasonable balance between the concerns of

stability in the law, on one hand, and

equity, on the other. See United States v.

Johnson. 457 U.S. at 555-56.

Third, it promotes the legitimacy of

the constitutional decision-making

process;1 full prospectivity creates the

1 A contrary approach would undermine

constitutional adjudication in another way

not explored in the text. Without some

incentive for litigants to raise an issue

that previously had been rejected by the

8

appearance of the judiciary "fishing one

case out of the stream of appellate review,

using it as a vehicle for pronouncing new

constitutional standards, and then

permitting a stream of similar cases

subsequently to flow by unaffected by that

new rule...." Mackev, 401 U.S. at 678-79

(Harlan, J., dissenting). Finally, it is

consonant with "basic judicial

courts, outmoded, incorrect, or inefficient

rules never would be challenged. Without

some incentive, it would always be too

"costly," — the issue would be displaced

in the litigant8s brief by other issues

more likely to succeed or, at least, more likely to command the attention of an

appellate court. See Jones v. Barnes. 463 U.S. 745 (1983).

Obviously, the incentive that motivates litigants to challenge such rules is the

possibility of victory on appeal. A pure

prospectivity rule diminishes severely that

incentive by limiting to a universe of one

the number of litigants who possibly may

benefit from a rule change. The predictable

result is a dearth of necessary challenges

to outmoded doctrines and the potential

ossification of the law. See Priest &

Klein, Tjje__Selection__of__ Disputes__forLitigation. 13 J. Legal Stud. 1 (1984)?

Priest, The Common_____ Process and the

Selection of Efficient Rules. 6 J . Legal Stud. 65 (1977).

9

tradition....n Desist v. United States. 394

U.S. 244, 258 (1969) (Harlan, J.,

dissenting); see United States v. ThP

sc,ho<?ner Peggy, 5 u.s. (i cranch) 103,

110 (1801).

It is our position, however, that the

decision in Batson should be accorded full

retroactive effect under the standards

developed in Mukletter and its progeny.2

In the sections that follow, we discuss the

tripartite standard governing retroactivity

articulated in Stovall v. Denno. 388 U.S.

293, 297 (1967),3 as interpreted in

subsequent cases.

2 Because the Court now has thebenefit of full briefing and argument on

this issue, it would be appropriate to

reconsider its contrary decision in Allen

— HSZdy, ___ U.S. ___, No. 85-6593 (June30, 1986).

3 The Stovall Court expressed theconsiderations as follows: "(a) the

purpose to be served by the new standard?

(b) the extent of reliance by law

enforcement authorities on the old

standards, and (c) the effect on the

administration of justice of a retroactive application of the new standards." J&. at 297.

10

a . The Exclusion.__fif__BlasKa__fmscriminal...-Juxies___&&fes&g___ inFundamental Wavs the, Accuracy andReliability of the Decision-making

Process

The use of peremptory challenges to

remove potential jurors on the basis of

their race violates core constitutional

values concerning equal protection and

public participation in the criminal

justice system; it undermines as well

public confidence in the legitimacy and

fairness of that system. But it does not

follow that these are the primary values

implicated by this unconstitutional

practice.

Common sense suggests that the rule of

Batson is neither a mere prophylactic—

like those at issue in Johnson v. New

Jersey. 384 U.S. 719 (1966), and Shea v.

Louisiana — nor a product solely of

policy concerns extrinsic to the accuracy

and reliability of the trial process—

like those at issue in Linkletter and

11

United States V .Johnson. Rather, like the

rule against coerced confessions, it

serves "a complex of values," Blackburn v.

Alabama, 361 U.S. 199, 207 (1960), some of

which bear heavily on the truth-finding

process and, therefore, mandate retroactive

effect. L.ljLkletteg, 381 U.S. at 638? s^e,

Arsegaiilt v. Massachusetts, 393 U.S.

5 (1968).

This is clear when one considers the

nature of the practice that Batson

condemned. Prosecutors who used their

peremptory challenges to strike black

potential jurors did so not primarily out

of blind racial animus; they did so because

they believed that it affected the outcomes

of their cases. Thus, one prosecutor

testified about his former practice and the

reasons for his change:

So we made a determination that we were

not going to in any way discriminate against blacks; we were going to try to

keep black jurors,.., and the longer we tried that, the more discouraged we got about it.... We just had to abandon

12

that philosophy. * * * And the defense

attorneys can tell you very well when

that happened, because it's when they

started losing more cases.

Edwards v. Thigpen. Civil Action No. J 83-

0566(B)(S.D. Miss.), Deposition of Edward

J. Peters at 31, 34 (April 12, 1985).

All jurors are not fungible; the

deliberate exclusion of minorities from

criminal juries has a direct and

demonstrable effect on the actual outcomes

of criminal cases. The reasons are readily

apparent when one considers both what a

jury does and how it does it.

It is simplistic to view the jury

solely as the finder of "facts” subject to

measurement by some objective standard of

"truth" or "falsity." Hardly any criminal

case is so one-dimensional. Nor is the

jury's judgment limited to the binary

alternatives of "guilt" or "innocence."

"[T]he jury plays a political function in

the administration of the law...." Tavlor

v. Louisiana. 419 U.S. 522, 529 (1975). "It

13

must be remembered that the jury is

designed not only to understand the case,

but also to reflect the community's sense

of justice in deciding it.” Id. at 26 n. 37

(quoting H.R. Rep. No. 1076, 90th Cong., 2d

Sess., reprinted in 1968 U.S. CODE CONG.

AND AD. NEWS 1792, 1797, the House Report

on the Federal Jury Selection and Service

Act of 1968, 28 U.S.C. §§ 1861 et seq.).4

The jury functions in part by invoking

its values to express the community's judg

ment of the severity of the offense and the

moral culpability of the offender. Cf.

Vasqqeg__v_.__Hillerv. 474 U.S. ___, 88

L.Ed.2d 598, 608-09 (1986)(grand jury). It

4 As Justice Rehnquist has observed: "Trial by a jury of laymen rather than by the sovereign's judges was important to the

founders because juries represent the

layman's common sense, the 'passionate elements in our nature,' and thus keep the

administration of law in accord with the wishes and feelings of the community."

v, shore. 439 u.s. 322, 341-42 (1979) (Rehnquist, J. , dissenting) (quoting 0. Holmes, COLLECTED LEGAL PAPERS 237 (1920)).

14

may do so in obvious ways, as when it

chooses between guilt of the crime charged

or of a lesser included offense. See Keeble

v. United States. 412 U.S. 205 (1973) . Or

it may do so in less obvious ways when it

treats the variety of factual and mixed

factual-legal decisions with which it is

regularly confronted.

This becomes clear when one considers

the multi-dimensional nature of even a

simple criminal case. For example,

[i]magine a manslaughter charge arising

out of reckless driving. The decision

maker must determine the truth of a

certain number of propositions

regarding "external facts," such as the

speed of the automobile, the condition

of the road, the traffic signals, the

driver's identity, and so on. ... The

inquiry here appears to be relatively

objective, and the truth about such

facts does not seem to be too elusive.

But many "internal facts" will

also have to be established. . . . They

regard aspects of the defendant's

knowledge and volition.... The

ascertainment of such facts is already

a far less objective undertaking than

the ascertainment of facts derived by

the senses....

15

The situation changes, however,

when the facts ascertained must be

assessed in the light of the legal

standard. Whether a driver has deviated from certain standards of care -- and

if so to what degree — are problems

calling for a different type of mental

operation than that used in dealing

with external facts.

Damaska, Presentation of Evidence and Fact

finding Precision, 123 U.Pa.L.Rev. 1083,

1085-86 (1975). The impact on the decision

making process of the exclusion of

minorities must be understood at each level

of the truth-finding process.

The exclusion of minority jurors will

inevitably result in the exclusion of

perspectives and values not otherwise

represented. This will have obvious impact

on the qualitative decisions regarding

intent and the application of legal

standards to the facts of the case. But

even at the first, most objective level —

that of "external facts" — the exclusion

of minorities will have a skewing effect on

16

the accuracy of factfinding in several

distinct ways.5

A jury is often called upon to

ascertain facts on the basis of the

credibility of the witnesses. In a case

involving a black defendant — ■ or, as in

Griffith. a black defendant and white

victims — the array of witnesses will

often divide on racial lines. In assessing

their credibility on the basis of their

demeanor, for example, it matters a great

deal if there are blacks on the jury who

are accustomed to the habits of speech and

mode of presentation exhibited by the

5 One study found that, when showed a

picture of a white person armed with a

razor apparently arguing with a black man,

over half of the subjects reported that it

was the black man who held the razor. G.

Allport & L. Postman, THE PSYCHOLOGY OF

RUMOR 111 (1965), discussed in Johnson,Black Innocence and_tfa.S.... Wh l.fce _ Ju ry, 8 3

Mich. L. Rev. 1611, 1645 (1985).

17

defendant that might be unfamiliar or even

threatening to white jurors.6

The perception of primary, "external

facts" is also affected by the values

brought to the jury room. The Court

recognized as much in Adams v. Texas. 448

U.S. 38 (1980) — where the value at issue

was the jurors' scruples against the death

penalty. There, the Court acknowledged that

the jurors' values "may affect what their

honest judgment of the facts will be or

what they may deem to be a reasonable

6 See Peters v. Klff, 407 U.S. 493(1972)(plurality opinion):

When any large and identifiable segment

of the community is excluded from jury

service, the effect is to remove from

the jury room qualities of human nature

and varieties of human experience, the

range of which is unknown and perhaps

unknowable. It is not necessary to

assume that the excluded group will

consistently vote as a class in order

to conclude ... that its exclusion deprives the jury of a perspective on human events that may have unsuspected importance in any case that may be presented.

Id. at 503-04.

18

doubt. Such assessments and judgments by

jurors are inherent in the jury system.

..." Id. at 50.

This conclusion, of course, has strong

empirical foundations in the work of

Professors Kalven and Zeisel, H. Kalven,

Jr., & H. Zeisel, THE AMERICAN JURY (1966).

In their study of judge-jury disagreements,

they found that

to a considerable extent, or in exactly

45 per cent of the cases, the jury in

disagreeing with the judge is neither

simply deciding a question of fact nor

simply yielding to a sentiment or

values; it is doing both. It is giving

expression to values and sentiments

under the guise of answering questions

of facts.

Kalven & Zeisel, supra. at 116.7

7 Thus, what may look apparent to a

reviewing court may have seemed very

different to the jurors who heard all the

testimony and wrestled with the facts in

light of community values. H[T]he more one

is removed from the fullness of life, the

more limited but also the more precise is

our knowledge; there is one fixed

perspective. On the other hand, the closer

one remains to the complexity of real life

processes, the more encompassing but also

the less certain is one's understanding; as

in cubism, our sensations come from

19

Moreover, the very nature of the

reasonable doubt standard means not only

that the jury will necessarily call upon

its values, but also that an individual

juror will make a difference, Kalven and

Zeisel found that juries by and large have

a higher threshhold of reasonable doubt

than do judges, but they did not ascribe

that difference to any "distinctive

value[s] held by laymen." Kalven & Zeisel,

suora, at 189 n. 5. Rather, they concluded

that if a jury "decides close cases with a

higher cut-off point than does a single

judge, the explanation may reside in the

unanimity requirement. The jury, to avoid

disagreement, would tend in the direction

of its most stringent member." Id. Thus,

the exclusion of a single minority juror

who holds a more stringent view of "what

[he] may deem to be a reasonable doubt...,"

multiple viewpoints and there is more than

one side to every story." Damaska, supra,

at 1104.

20

Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. at 50, will have a

profound impact on the jury's decision

making process. This affects the truth

finding process in a manner so vital as to

command retroactive application. See

HanKf£.gon_y« North Carolina, 432 U.S. 233

(1977); XyaiL-V.. V,. CjtY of_K£W_XQ£k, 407

U.S. 203 (1972).

The improper exclusion of even a single

minority juror will have an actual impact

on the outcome of the jury verdict in other

empirically demonstrable ways. For example,

Kalven and Zeisel found that the incidence

of hung juries depends on the number of

dissenting jurors: "for one or two jurors

to hold out to the end, it would appear

necessary that they had companionship at

the beginning of the deliberations. ... To

maintain his original position, not only

before others but even before himself, it

is necessary for him to have at least one

ally." Kalven & Zeisel, supra, at 463.

21

Thus, the use of peremptory challenges to

exclude a single minority juror could

literally spell the difference between

conviction, on one hand, or a hung jury

resulting ultimately in acquittal, on the

other. §&& Brown v, Louisiana, 447 u.s. at

332 & n. 10.

The Court need not speculate on this

matter, for the records in each of the

cases before it provide eloquent

demonstrations of the impact of this

practice on actual juries. In Brown. the

Assistant United States Attorney testified

that the reason he used his peremptories to

strike blacks was that a previous case in

which he did not do so ended in a hung

jury. Appendix D to the Petition for

Certiorari in No. 85-5731, at 20.

Griffith provides an even more

compelling example. There, the key issue

was a questionable cross-racial

22

identification.8 Mr. Griffith was tried

twice. He was convicted by a jury from

which blacks were purged by the

prosecutor's use of peremptory challenges.

But the first trial, at which the

prosecutor struck only three of the four

blacks on the venire, ended in a hung jury.

The exclusion of a single minority

juror can have an actual impact on the

ultimate verdict in another way. Kalven and

Zeisel found "that with very few exceptions

outcome of the

verdict-" Kalven Ss Zeisel, supra. at 488

(emphasis in original). The effect of the

initial vote was quite precise, and

revealing: an initial vote of 7-5 to

convict resulted in a verdict of "guilty"

86% of the time; an initial vote of 7-5 to

acquit resulted in a verdict of "innocent"

8 Mr. Griffith testified and denied

guilt. One of the white victims, who

positively identified him as the assailant,

also testified that she saw him on the

street two weeks after the crime ■— at a

time when Mr. Griffith was in jail awaiting

trial.

23

91% of the time; and an initial vote of 6-6

made the ultimata result a toss-up; "the

final verdict falls half the time (it so

happens, exactly half the time) in one

direction and half in the other." X£. The

impermissible purging of a single minority

juror can shift the balance on the initial

vote in a way that in fact determines the

outcome.

"Thus, it makes a good deal of

difference in this decision-making who the

personnel are." Kalven & Zeisel, supra. at

496; ggg_jUpQ SaUard v, United States. 329

U.S. 187, 194-95 (1946). Indeed, the

identity of the jurors is more important to

the outcome than the deliberation process.

Kalven & Zeisel, at 496. Thus, the

fact that the remaining jurors may

themselves be fair and impartial "does

nothing to allay our concern about the

reliability and accuracy of the jury's

verdict." Brown y f_Louisiana. 447 u.s. at

24

333. "Any practice that threatens the

jury's ability to perform that function

poses a similar threat to the truth

determining process itself. The rule in

[Mtson] was directed toward elimination of

just such a practice. Its purpose,

therefore, clearly requires retroactive

application." £d. at 334.9

B- 3Zhe— Reliance_by Prosecutors on Swain

Does____ Not__ Support Prospective

Application of the Standards Enunciated in Batson

Batson was not the kind of "clear

break" with past precedent that would

warrant prospective application. First,

Batson did not purport to change the

substantive standard governing the use of

peremptory challenges by prosecutors. To

9 DeStefano v. Woods. 392 U.S. 631

(1968), is not to the contrary. It is one

thing to say that a judge's determinations

are no less accurate and reliable than a

jury's. But it is quite another to provide

a jury and then ignore the fact that it has

been tampered with in ways affecting

directly its decision-making function. See

fi£2wn, 447 U.S. at 334 n. 13.

25

the contrary, it began its analysis with

the observation that "Swain ... recognized

that a 'State's purposeful or deliberate

denial to Negroes on account of race of

participation as jurors in the

administration of justice violates the

Equal Protection Clause.1" Batson. 90

L.Ed. 2d at 79 (quoting Swain.v.__AlSkSlS.,

380 U.S. at 203-04).

Although Batson did of course overrule

Swain in part, it did so only with regard

to the mode of proof to be employed in

proving discriminatory use of the

peremptory challenge. If prosecutors relied

on the Swain standards, they relied on

those standards not to justify their

conduct but merely to insulate their

knowingly impermissible conduct from

effective review. This is not the kind of

"good-faith reliance," Brown v. Louisiana.

447 U.S. at 335; DeStefano v. Woods. 392

U.S. 631, 634 (1968), that justifies

26

prospectivity rule.10

No prosecutor could have been unaware

that racial discrimination ... violates

deeply and widely accepted views of

elementary justice.... Over the past

quarter of a century, every

pronouncement of this Court and myriad

Acts of Congress and Executive Orders

attest a firm national policy to

prohibit racial segregation and

discrimination....

Bob. Jones University v. United States. 461

U.S. 574, 592-93 (1983) . Thus, in every

case in which the defendant, pursuant to

Batson, makes a prima facie case that the

prosecutor used peremptory challenges to

eliminate blacks for impermissible motives,

it is necessarily true that there is reason

to believe that the prosecutor knowingly

eternal insulation by means of a

10 Certainly, no prosecutor who tried

a case subsequent to the decisions

respecting the denial of certiorari in

McCray_v. New York, 461 U.S. 961, 963

(1983)(Marshall and Brennan, JJ.,

dissenting from the denial of certiorari);

id. at 961 (Stevens, Blackmun, and Powell,

JJ., opinion respecting the denial of

certiorari), could fail to be on notice

that the practice was constitutionally

suspect.

27

committed "a grave constitutional

trespass." Vasouez v, Hillery. 88 L.Ed.2d

at 608.

Second, even Batson's change in the

evidentiary standard was not a "clear

break" with past law. The Court's review in

Batson of its intervening decisions

regarding proof of impermissible racial

motive conclusively demonstrates that

Batson was foreshadowed in a host of cases.

Where Swain had indicated that "an

inference of purposeful discrimination

would be raised on evidence that a

prosecutor, 'in case after case, whatever

the crime and whoever the defendant or the

victim may be, is responsible for the

removal of Negroes...,'" Batson. 90 L.Ed.2d

at 84 (quoting Swain. 380 U.S. at 223),

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Coro.. 429 U.S. 252 (1977), had

made clear

28

that "a consistent pattern of official

racial discrimination" is not "a

necessary predicate to a violation of

the _ Equal Protection Clause. A single

invidiously discriminatory governmental

act" is not "immunized by the absence

of such discrimination in the making of other comparable decisions."

Batson, 90 L.Ed.2d at 87 (quoting Arlington

Heights, 429 U.S. at 266, n. 14); see also

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. at 629-31.

Moreover, »[t]he standards for

assessing a prima facie case in the context

of discriminatory selection of the venire

have been fully articulated since Swain."

Batson, 90 L.Ed.2d at 87. It was " [t]hese

principles" — spelled out in the Court’s

cases from 1972 onward11 — which

supported the "conclusion that a defendant

may establish a prima facie case of

11 The Court cited and discussed Alexander v. Louisiana. 405 U.S. 625, 629-

31 (1972); McDonnell Douglas Coro. v,

Gregn, 411 U.S. 792 (1973)(Title VII);

Washington v. Davis. 426 U.S. 229, 241-42 (1976); and Castaneda v. Partida. 430 U.S.

482, 494-95 (1977), as articulating the

evidentiary standards to be applied. Batson, 90 L.Ed.2d at 87-88.

29

purposeful discrimination in selection of

the petit jury solely on the evidence

concerning the prosecutor's exercise of

peremptory challenges at the defendant's

trial." M-

c. The potential____Effigt____on----the

Admin i st r a t ion._ of . Is _Dofc__s3overwhelming as to___Override___the

Foregoing Factors

The balance of considerations raised by

the concern for the effect of Batson on the

administration of justice is not so

overwhelming as to override the concern for

accuracy in the jury's decision-making

process.

First, it is not clear that this factor

points only in the direction of

prospectivity. There are cases that raise

the issue of discriminatory use of

peremptories on records that meet the

standards of either Batson or Swain. See,

e,g, , Evans v,_ Mississippi, No. 85-6932,

cert, denied, 54 U.S.L.W. 3810 (June 9,

1986). Indeed, Brown may well be just such

30

a case.12 It would be not only anamolous

but wasteful to require the lower courts to

hear such petitioners present the "case

after case" evidence required by Swain when

their claims might be proved more

efficiently under the Batson standards.

Second, it is not at all clear that the

number of Batson claims that properly were

preserved in the state courts is so high

that a general jail delivery is to be

feared. Sge Walawrlght v. Svkes. 433 U.S.

72 (1977)* Hankgrson_v_.„_North Carolina. 432

U.S. at 244 n. 8. For those who did not

perserve the claim, it is unlikely that

12 In his concurring opinion in Batson, Justice White explained that even

under Swain it would be proper for a trial

judge to invalidate the prosecutor's use of peremptories in a case in which he or she

admitted to doing so on the basis of race,

especially if the defendant is black.

Batson, 90 L.Ed.2d at 90 n. *. In Brown.

the Assistant United States Attorney ultimately admitted to the trial judge

that: "I said 'We would like to have as few

black jurors as possible,' which is exactly either I'm sure what I said or close to

it...." Appendix D to the Petition for Certiorari in No. 85-5731, at 70.

31

they will be able to show cause; the very

cases that warned prosecutors of the

illegality of the practice also provided

the tools for competent counsel to raise

and preserve the claim. See Encfle v ._Isaac,

456 U.S. 107 (1982). Moreover, the lower

courts may properly limit consideration to

only those cases in which there is an

adequate proffer of evidence to suggest a

prima facie case. See.. e. gt., EsquivgJL— v_jl

McCotter. 791 F.2d 350, 351 (5th Cir. 1986)

(state court found that no Spanish-surnamed

jurors were struck).

In any event, the Court has never held

that a practice which strongly implicates

the truth-finding process will nevertheless

be given retroactive condonation simply

because of the the widespread nature of the

violation. &£§ Hanker son v̂ _iio£yi-CamLlna,

432 U.S. at 243.

32

II. THE NATURE OF THE SENTENCING DECISION IN CAPITAL CASES IS SUCH THAT THE

EXCLUSION OF MINORITIES FROM THE JURY

NECESSARILY DIMINISHES ITS RELIABILITY,

REQUIRING RETROACTIVE APPLICATION OF

BATSON TO CAPITAL SENTENCING PROCEEDINGS ___________________ ______

The nature of the capital sentencing

decision made by a jury calls for the

retroactive application of Batson because

of the "unacceptable risk ... infecting the

capital sentencing proceeding---" Turner

v. Murrrav, 476 U.S. __ , 90 L.Ed.2d 27, 37

(1986) (emphasis in original), that results

from the exclusion of minorities from

sentencing juries. This unacceptable risk

arises in two separate ways.

"In a capital sentencing proceeding

before a jury, the jury is called upon to

make a 'highly subjective, "unique,

individualized judgment regarding the

punishment that a particular person

deserves.'"" Turner. 90 L.Ed.2d at 35

(quoting Caldwell v, Mississippi. 472 u.s.

__ , 86 L.Ed.2d 231, 247 n. 7 (1985), and

33

zant v, S t e p h e n s , 462 u . s . 862 , 900

(1983)(Rehnquiat, J., concurring)). Because

"[i]t is entirely fitting for the moral,

factual, and legal judgment of judges and

juries to play a meaningful role in

sentencing..., sentencers will exercise

their discretion in their own way and to

the best of their ability.” Barclay v.

Florida. 463 U.S. 939, 950(1983)(plurality

opinion). "The sentencing process assumes

that the trier of fact will exercise

judgment in light of his or her background,

experiences, and values." Id. at 970

(Stevens and Powell, JJ., concurring).

Given the inherently subjective, value

laden nature of the capital sentencing

determination, there is risk of substantial

inaccuracy and unreliability in the death

verdict imposed or recommended by a jury

from which minorities were purged. This

risk arises in two ways. First, "[bjecause

of the range of discretion entrusted to a

34

jury in a capital sentencing hearing, there

is a unique opportunity for racial

prejudice to operate but remain

undetected." Turner. 90 L.Ed.2d at 35. The

impermissible removal of black potential

jurors from the jury room removes one of

the best — if not the best — means of

curbing such abuse: The presence of a black

juror provides both a means to unmask

prejudice should it creep into the jury

room and a powerful deterrent against its

entry.

Second, the very function of a jury in

a capital case is to serve as a "link

between contemporary community values and

the penal system — a link without which

the determination of punishment could

hardly reflect the 'evolving standards of

decency that mark the progress of a

maturing society.'" Gregg v. Georgia. 428

U.S. 153, 190 (1976) (plurality

opinion)(quoting Trop v. Dulles. 356 U.S.

35

86, 101 (1958)). That link is destroyed

when important segments of the community

are deliberately and impermissibly

excluded. All the reasons that demonstrate

that the exclusion of blacks from the

guilt/innocence stage of the trial affects

the decision-making process apply with

greater force to the sentencing decision,

which more openly calls for the exercise of

discretion and the interpolation of values

in the application of the law.

The Court recognized as much in

Witherspoon v. Illinois. 391 U.S. 510

(1968) concerning the exclusion of

individual jurors because of their values

regarding capital punishment — where it

held that decision entirely retroactive.

Id* at 523 n. 22. See also Davis v.

Georgia. 429 U.S. 122 (1976) (improper

exclusion of single Witherspoon juror

requires reversal). So too, in capital

cases in which the prosecution used its

36

perexnptories impermissibly to remove blacks

— and to a much greater degree — "the jury

selection standards employed

necessarily undermined 'the very integrity

of the ... process' that decided the

petitioner's fate ... requiring the fully

retroactive application of..."13 Batson to

capital sentencing proceedings.

13 Witherspoon. 391 U.S. at 523 n. 22

(quoting Linkletter, 381 U.S. at 639).

37

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the

j udgments of the courts below should be

reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON 99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013 (212) 219-1900

STEVEN L. WINTER*

University of Miami School of Law

P.0. BOX 248087

Coral Gables, Fla.

33124-8087

(305) 284-2392

Attorneys for the NAACP

Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

LOIS WALDMAN

The American Jewish Congress

15 East 84th Street

New York, N.Y. 10028

♦Counsel of Record

38

Hamilton Graphics, Inc.— 200 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y.— (212) 966-4177