Eaton v. James Walker Memorial Hospital Board of Managers Deposition of Doctors - Volume I

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Eaton v. James Walker Memorial Hospital Board of Managers Deposition of Doctors - Volume I, 1965. cc5a407a-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5b0e7375-0e7d-40cb-b585-3ba95416b68f/eaton-v-james-walker-memorial-hospital-board-of-managers-deposition-of-doctors-volume-i. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

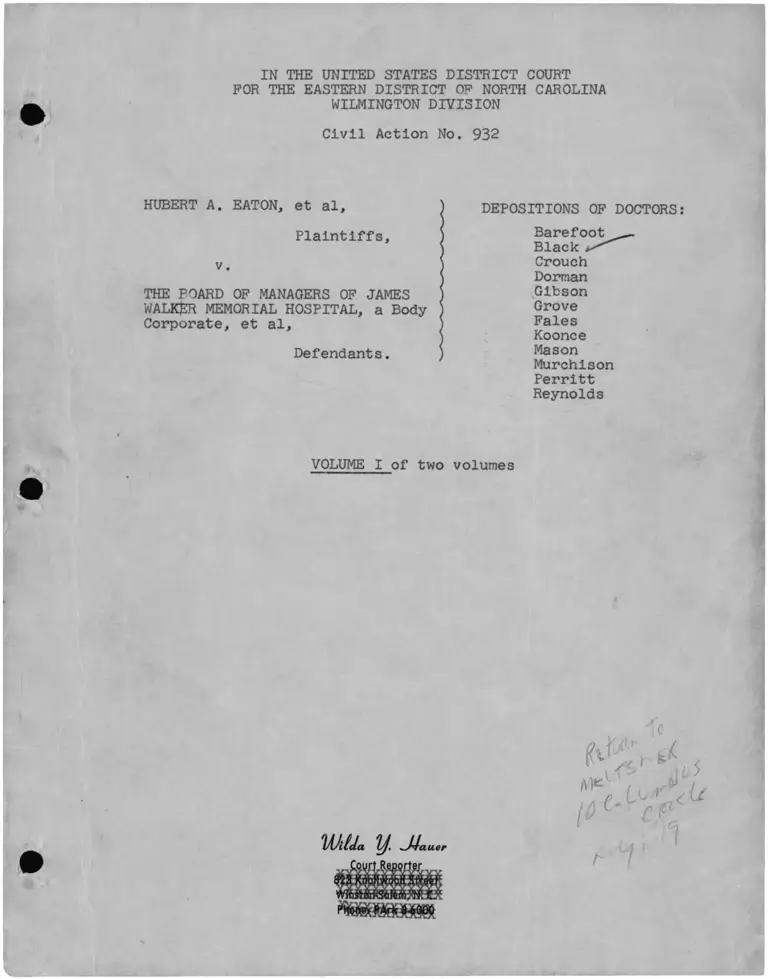

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

WILMINGTON DIVISION

Civil Action No. 932

HUBERT A. EATON, et al,

Plaintiffs,

v.

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF JAMES

WALKER MEMORIAL HOSPITAL, a Body

Corporate, et al,

Defendants.

DEPOSITIONS OF DOCTORS:

Barefoot

Black

Crouch

Dorman

Gibson

Grove

Fales

Koonce

Mason

Murchison

Perritt

Reynolds

VOLUME I of two volumes

auerWitia y. JJ,

A)^

[0

\ < v > /

p c > JCj

h

La

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

WILMINGTON DIVISION

Civil Action No. 932

HUBERT A. EATON, et. al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF JAMES WALKER

MEMORIAL HOSPITAL, a Body Corporate,

et. al.,

Defendants.

Depositions of the above-named witnesses were

taken by plaintiffs before the undersigned Wilda Y. Hauer,

Official Court Reporter and Notary Public, on Tuesday,

July 20, 1965, beginning at 9:15 a.m. in the courtroom

of the United States Customhouse, Wilmington, North

Carolina, and continuing through Wednesday, July 21, 1965.

APPEARANCES

For Plaintiffs:

Michael Melesner, Esq.,

10 Columbus Circle, New York City 10019

Julius LeVonne Chambers, Esq.,

405^ East Trade Street, Charlotte, N. C.

For Defendants;

Cyrus D. Hogue Jr., Esq., and William S. Hill, E

Post Office Box 1268, Wilmington, N. C.

Depositions of

Twenty-two

Witnesses Listed

in Index to

Volumes I and II.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

I N D E X

Direct Cross Redirect Recross

Dr. Graham Ballard Barefoot 3 7 9 —

Dr. Paul A. L. Black 12 18 19 22

23 27

Dr. Walter Lee Crouch 28 36 37 —

Dr. Bruce Hugh Dorman 41 49 5g58 56

Dr. James F. Gibson 59 69 71 —

Dr. Raymond S. Grove 73 74 75 mm mm

Dr. Robert Martin Fales 78 — — mmmt

Dr. Donald B. Koonce 81 97 98 —

Dr. L. B. Mason 102 116 120134 133

Dr. David Murchison 140 155 156 mm mm

Dr. John 0. Perritt, Jr. 158 l6o — —

Dr. Frank R. Reynolds 162 166 167

REPORTER'S NOTE; Mr. Meltsner's name l6

incorrectly spelled M-e-l-e-s-n-e-r in most of the

depositions.

Corrections and/or changes made by doctors

at time of signing noted in longhand and red ink, with

le exception of one note on page 247 typewritten by reporter

1th reference to note made by Dr. Wells at time of signing his

“position.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

D R. G R A H A M B A L L A R D B A R E F O O T , having

been duly sworn, testified as follows:

DIRECT-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q Will you state your full name, please.

A Graham Ballard Barefoot.

Q You are a physician?

A Physician; radiologist.

Q Your specialty is---

A Radiology.

Q How long have you been practicing, Dr. Barefoot?

A I graduated on June 1, 1923.

0 Have you been practicing in Wilmington since

that time?

A I have been practicing in Wilmington since

January 1, 1930.

Q Are you a member of the staff of the James

Walker Memorial Hospital?

A I am a member of the staff of James Walker

Hospital.

Q Is a significant portion of your practice

carried out at that hospital?

A It's all carried out there at the present

4

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

time.

Q It's Important to your practice to use the

hospital?

A Well, my office Is in the hospital and I don't

have any other office except in the hospital. All of

my practice is in the James Walker Hospital.

Q Do you attend meetings of the medical staff

of the hospital?

A I do.

Q To your knowledge are minutes kept of those

meetings?

A They are.

Q Are the qualifications of physicians who

apply for medical staff privileges at the hospital

discussed at those meetings?

A They have committees who are appointed to

inspect the qualifications of the applicants and they

are reported back to the staff.

Q And then the staff votes?

A And then the staff votes by a letter.

Q It doesn't vote at a meeting?

A It doesn't vote at a meeting.

Q So these qualifications aren't discussed at

the meetings?

A They are not discussed. They tell whether

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

the man is qualified or whether he Isn't qualified, and

then he Is voted by letter.

Q The reports tell?

A The reports tell.

Q Did you receive In December of 1964 and again

in February of 1965 a letter concerning the application

of Dr. Eaton to the hospital?

A I did.

Q Ylhat did you do with those letters?

A Threw them in the wastebasket.

Q And under the hospital by-laws what does that

mean?

A That means that I voted for him. If they

don't get it within ten days - I don't know whether it

is a week or ten days - then you voted affirmatively

for the applicant. Unless you mark a negative vote on

there and mail it in - if you don't return the letter -

it's voted affirmatively.

Q And so you voted for Dr. Eaton's application?

A I voted for Dr. Eaton.

Q Do you know of anything that would reflect

negatively on Dr. Eaton's competence as a physician?

A I do not.

Q Do you know of anything which would reflect

negatively on his qualifications for a staff membership

at the hospital?

A I do not.

Q Do you have any idea why he was denied staff

membership?

A I do not. Ihe only reason that I would know

why he wasn't accepted, if a certain number of the staff

vote against him - I don't recall Just what that number

is - then they are not passed.

Q But you don't know the reason?

A I wouldn't know the reason. If it's three or

four - I have forgotten how many it is - I don't

remember. Although I have been there all this number

of years, I don't remember how many it takes to turn a

fellow down.

0 You are in the hospital most of the time?

A Spend most of my time right in the hospital.

Q Wouldn't you know about a reason if one

existed?

A It's never been discussed. I have heard no

body mention it except a lot of them were disappointed

when they said Dr. Eaton was turned down, and nobody

knew why. But it was never discussed. And I see many

of the staff members every day.

Q Was the report of the committee which in

vestigated Dr. Eaton's qualifications important to you

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

li

in deciding to vote for him? Did you vote for him in

part because the committee passed his qualifications?

A I voted for Dr. Eaton because I have known

him all through the years and he has been a very nice

gentleman, and I voted for him because I thought he

deserved to be on the staff.

MR. MELESNER: I have no further questions.

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. HOGUE:

q Doctor, you say you have been on the staff of

the hospital 3ince 1923?

A Well, I graduated in 1923.

Q How long have you been on the 3taff of the

hospital?

A Since January --no, February 1, 1930, when

I came back as a radiologist.

Q So you have been on the staff there for some

35 years?

A 35 years, yes, sir.

q Was the procedure with respect to Dr. Eaton's

application handled in any way different, to your

knowledge, from any other doctor who has applied for

that staff?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

A Ab far as I know it was handled Just like

anybody else's.

0 Isn't it true, Doctor, there are presently

two Negro doctors on the staff of Janies Walker Hospital?

A Yes, sir.

Q Dr. J. W. Wheeler?

A Yes, sir.

Q And Dr. Daniel Roane?

A That's right.

Q And I believe Dr. S. J. Gray was also accepted

on the staff?

A I believe so.

Q Would you state whether or not the procedures

used with respect to Dr. Eaton's application were used

with respect to the applications of Drs. Wheeler and

Roane and Gray?

A So far as I know they were identical - I mean

the way it was handled.

Q Now, Doctor, do you of your own knowledge know

of any white doctor whose application has been voted down

by the staff?

A Well, through the years I have known several.

q You have known several?

A Yes, sir. They would make reapplication and

eventually were accepted by the Board of Managers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

13

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q Dr, Barefoot, did you ever know Dr. Kennon

Walden?

A Uie surgeon of the Coast Line?

Q Yes, sir.

A Yes, sir, I knew him very well.

Q Was he ever on the staff of the hospital?

A Not that I recall.

Q Doctor, do you know when the applications

of Dr. Wheeler and Dr. Roane and Dr. Gray were approved

by the medical staff?

A No, sir, I don't recall.

MR. HOGUEs I have no further questions.

REDIRE C T-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q You mentioned Dr. Walden was the surgeon

or the doctor for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad?

A Yes, sir; chief surgeon for the Atlantic

Coast Line Railroad.

Q Do you know anything about a controversy

between Dr. Walden and other physicians in Wilmington?

A I recall that there was some controversy,

but what it was - it's been too long - I don't recall

Just what it was.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

13

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

23

Q Let*s see if I can refresh your recollection.

Dr. Walden was the medical director and chief surgeon for

the railroad; is that correct?

A Ihat’s right.

Q And the railroad had its home office here in

Wilmington at that time?

A That1s right.

Q Wasn’t there a fear in the medical community

that if Dr. Walden were placed on the staff of the James

Walker Hospital, he would then treat all of the Coast

Line employees?

MR. HOOUE: I want to put an objection

in the record to that. I don't know whether--

A I don't think there was any fear of that type

as far as I know.

Q What was the fear?

A As I say, I don't recall. It has been so long,

and it just didn't register with me. I don't recall Just

what the situation was.

Q Did Dr. Walden leave Wilmington?

A He left, but I don't know what became of him.

Q Do you know when he left?

A No, sir, I don't.

Q Do you know anything about the railroad's

arrangement with another hospital in the Wilmington area

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

for the treatment of its employees?

A I don't recall just exactly what there was.

I remember something to that effect, but what it was I

don't recall.

Q You remember that there was such an arrange

ment?

A I remember that there was something said about

it. But now, whether there was such an arrangement, I

don't know; I wouldn't be qualified to state whether

there was or there wasn't. It didn't register with me.

Q Did the railroad subsequently leave Wilmington,

remove its home office from Wilmington?

A Ihey finally moved to Jacksonville, Florida,

moved the home office down there.

HR. MELESNER: I have no further questions.

MR. HOGUE; No further questions.

Signature of Witness:

L A W Y E R ’ S NOTES

P a g e L in e

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

ll

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

p R . P A U L A. L. B L A C K , having been duly sworn,

testified as follows:

DIRECT-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q Will you state your full name, please •

A Paul A. L. Black.

Q You are a physician?

A Right.

Q What is your medical specialty, 3ir?

A Eye, ear, nose and throat.

Q How long have you practiced in this community?

A Since 1938*

Q Are you a member of the staff of the James

Walker Memorial Hospital?

A Yes, sir.

Q Are you a member of the staff of the Community

Hospital?

A Yes, sir.

Q As a member of the staff of the Community

Hospital have you had occasion to know and observe Dr.

Hubert Eaton?

A Yes, sir.

Q For how many years, approximately?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

A Probably fifteen.

Q Did you In December of 1964 and again in

February of 1965 receive a letter from the medical staff

president of the James Walker Memorial Hospital with

respect to Dr, Eaton's application for courtesy staff

privileges at the hospital?

A Yes.

Q What did you do with this letter?

A I didn't return it to the hospital. I don't

recall; it probably stayed on my desk for a little while.

Q What is your understanding of the meaning of

not returning the letter?

A It was a vote in favor of the individual.

I usually don't return them.

Q Do you know why Dr. Eaton was denied staff

membership at the James Walker Memorial Hospital?

A No, sir.

© Was his application ever discussed in a meeting

of the staff of the James Walker Hospital?

A Not to my knowledge.

Q Did you attend staff meetings regularly?

A Yes, sir.

Q And you recall no discussions?

A Nc, sir.

Q Do you think you would have heard it if there

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

had been discussion?

A Well, I don’t attend all staff meetings; I

attend most of them, the majority of them. I would have

if I had attended. I didn't know that it was discussed

at the time.

Q Were you aware that Dr. Eaton's application

had been passed by the credentials committee of the

hospital?

A I recall that there was something said about

his credentials had been passed.

Q Did that carry weight with you?

A Well, a3 I told you, I did not return the

letter, and I wouldn't see where that would have any

weight with me one way or the other.

Q That was an affirmative vote - not returning

the letter?

A Right.

Q Let me ask you this: If nothing was said

at a staff meeting aside from the report of the credentials

committee, can you think of any way in which a staff

member like yourself receives information concerning a

particular applicant?

A Might from private discussion.

Q Private discussion?

A Right.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q And when you voted for Dr. Eaton, was this

on the basis of your experience and observation of him?

A Yes.

Q Did you perform surgery at the Community

Hospital?

A

Q

A

Q

should be

Hospital?

Yes, sir.

Do you still do so?

Yes, sir.

Can you think of any reason why Dr. Eaton

denied staff membership at the James Walker

A I have no reason to deny it.

Q Can you think why anyone else would?

A Well, a person can think a lot of things and

discard their thoughts.

Q You’ve discarded any thoughts that you have?

A I presume.

Q Let me ask you this, Doctor: Generally every

white physician in the Wilmington area or in the City of

Wilmington is a member of the courtesy staff of the James

Walker Memorial Hospital; is that correct?

A Either that or the attending staff.

Q Are you a member of the North Carolina Medical

Society and its county affiliate here in Wilmington?

A Yes, sir.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

q Are most of the physicians on the courtesy

and attending staff at the hospital members of that

society?

A I believe so.

Q What is your understanding of the role of a

staff member voting on an application for staff member

ship?

A State that question again, please.

Q What is your understanding of the role of a

physician who is voting, passing on the application of

another physician?

A I think it's up to him to decide whether he

wants to vote or whether he doesn't want to vote.

Q For any reason he sees fit?

A Right.

Q I believe you said it's up to him whether

or not he votes. Do you mean votes for or against an

applicant ?

A It's up to him, yes, sir.

q And he should be free to do so as he wishes?

A Right.

q wouldn't that permit physicians on the staff

to reject people for any subjective reason they have -

say, if they had heard some rumor about him?

A I think they could be swayed by it or have an

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

opinion.

Q Isn't that a fault In the procedure; isn't

that a risk in this procedure, this voting procedure?

A I think it's a risk in any vote.

Q To your knowledge has the hospital or the

staff ever set out in writing any guidelines, standards,

which should govern the vote?

A Well, there are standards which I believe are

in the by-laws.

Q Aside from those.

A You mean whether a person should vote one way

or the other just on an opinion basis or hearsay basis

or something like that? I don't quite get what you are

fishing for.

Q My question is: are there any written

standards which the medical staff or the Board of

Managers has written down to guide physicians in con

sidering other physicians - any criteria?

A I don't think there are any more guidelines

than there is for voting for the President of the United

States. People vote as they wish.

Q You think it's about the same?

A I think it's the same, yes, sir.

MR. MELESNER: I have no further ques

tions.

i

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

13

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. HOGUE:

Q Dr. Black, you have been on the staff of the

hospital since 1938} Is that correct?

A Yes, sir.

Q Has this procedure been used with respect

to applicants of the staff ever since you have been on

It?

A Yes, sir.

Q The procedure for voting?

A Yes, sir.

Q Was Dr. Eaton's application handled the same

way yours was?

A Yes, sir. I was blackballed one time.

Q You say you were turned down one time?

A Yes, sir.

Q

correct?

And then later your reapplied; is that

A Yes, sir.

Q And were taken on the staff?

A Yes, sir.

Q Isn't it true that Dr, William J. Wheeler,

a Negro doctor, Is on the staff at the present time?

A Yes, sir.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Q And Dr. Daniel C. Roane?

A Yes, sir.

MR. HOGUE: No further questions.

REDIRECT-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q Did you use the word "blackball”?

A Well, you can call it anything you want - re

jected - voted against you.

Q But you used the word "blackball,” didn't you?

A Yes, sir. I think that is pretty plain when

a person is rejected.

Q Right. Only here a man's living is at stake,

isn't it?

A I presume. Pretty much in voting anything

something is at stake.

Q If you didn't have possible affiliation,

Doctor, as a man who does surgery your income would be

cut, wouldn't it?

A Hiere are other hospitals,

Q Well, if you didn't have any hospital

affiliation.

A I presume it would affect it.

Q Well, where could you do your operating?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

A If this was the only hospital; is that what you

mean?

Q That is my question, yes.

A I don’t know. I operate in five different

hospitals. I don’t have that problem. I don’t have any

opinion about it.

Q Well, it is true, is it not, that to a surgeon

a hospital and staff affiliation in a hospital is ex

tremely important?

A Yes.

Q When your application was rejected, when you

were "blackballed”, was your application to the courtesy

staff?

A It was to the attending staff.

Q Kie attending staff?

A Right.

Q When you were later placed on the staff, was

it the medical staff which placed you there, or was it

the Board of Managers?

A The recommendation comes from the doctors to

the Board of Managers and they appoint, as I understand

it.

Q So you were blackballed for the attending

staff?

A Right.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q But you had courtesy privileges at that tine?

A Right.

Q So you were on the hospital staff when this

occurred?

A That *s right.

Q That's correct?

A Eiat's correct.

Q You could have used the facilities of the

hospital?

A Oh, yes.

Q Well, what is the difference between the

courtesy and the attending staff?

A There isn't hardly any difference any more;

there used to be.

Q Was there a difference when you applied?

A Ye3, sir.

Q What was it?

A Well, there were teaohing privileges, and the

right to vote, and so on. Part of that still exists,

but the courtesy and the attending staff is practically

the same thing now as far as patients are concerned.

Q But not as far as the voting on applications

is concerned; is that true?

A The voting is only by the attending staff,

I understand

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q So Dr. Wheeler Is not on the attending staff?

A Well, it's practically the 3ame thing except

for voting,

Q He did not vote, as far as you know, on Dr.

Eaton's application?

A I don't believe he can. I don't believe he

is on the attending staff. I really don't know about that;

I don't know whether he Is on the attending staff or

not, I haven't kept up with it.

Q Would you expect the same thing that is true

for Dr. Wheeler would be true for the other Negro

physician on the staff?

A I don't think It has anything to do with

race,

Q I'm asking you whether or not Dr. Roane is

on the attending staff now or the courtesy staff?

A I have no knowledge, because I don't know

whether he has applied. I would say that there is

essentially no difference as far as the care of patients

is concerned.

MR. MELESNER: I have no further questions.

RECROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. HOGUE:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

q Do you know whether or not any other white

doctors have been voted down upon application to this

staff, either attending or courtesy?

A I think there are lots of them that were voted

down, yes, sir.

MR. HOGUE: No further questions.

RE DIRE C T-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q Would you name any physicians you know of who

have been rejected for the courtesy staff who were not

on the staff?

A I don't know any names at the present time.

Q Have you ever been acquainted with Dr. Kennon

C. Walden?

A Yes, sir; not well, but I knew him. He was

the Coast Line physician and surgeon.

q Do you know that Dr. Walden was denied member

ship at the hospital?

A I think he was denied some privileges; it

was probably surgical. Whether he was denied courtesy

privileges, I do not know.

Q Isn't that strange - a man who was chief

surgeon for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and he is

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

denied staff or surgical privileges at the James Walker

Hospital?

A I don't know the reason why he wa3 denied.

Q Do you think it had to do with his medical

competence?

A I would think not, but I don't know. His

practice of medicine didn't have anything, really, to

do with mine; he was the Coast Line surgeon.

Q Is the Coast Line a large business in Wilmlng

ton?

A Used to be,

Q It moved out?

A Most of it.

Q Do you know anything about the arrangements

which the railroad, the Coast Line, made with a small,

private hospital in the community to take care of the

medical needs of its employees?

A I have no knowledge. I have heard that they

had an arrangement, ye3, sir; but as far as that is

concerned, I have no knowledge or opinion about it. It

did not concern me.

Q Did Dr. Walden leave Wilmington after he was

denied full privileges at the hospital?

A I ’d say yes, but it didn't have anything to

do with his being denied privileges.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q Do you know why he left?

A No.

Q Do you know why the railroad left?

A You tell me.

Q You don't know; that's the answer?

A Right.

Q Now, were you acquainted with a Dr. William

J. Wilson who practiced in Wilmington?

A Yes, sir.

q Was he denied courtesy staff privileges at

the hospital?

A I don't know. I don't remember whether he

was ever denied it or not.

Q He was on the staff of the hospital at one time,

wasn't he?

A Yes, sir.

Q Would you say that there may have been a

legitimate reason for the denial of the privileges of

Dr. Wilson which had nothing to do with his medical

competence?

A Hearsay; and I wouldn't give an opinion on it.

Q On the basis of hearsay, would there have

been such a reason?

A I think so if there was enough of a problem.

q Doctor, I don't think any of us here want to

1

2

3

4

3

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

l6

17

18

get into this in any detail—

A I must be the first one.

Q Pardon me ?

A I say I must be the first one this morning.

Q You are the second. Ttoere was a condition,

was there not, of general knowledge, shall we say,

suffered by Dr. Wilson which might have interfered with

his competence at the hospital.?

A State that again.

MR. MELESNSR: Strike the question. You

are perfectly correct.

q Dr. Wilson suffered from a disability which

might have interfered with his practice at the James

Walker Hospital; is that not correct?

A I guess you are telling me.

Q I»m asking you.

A I don*t know anything about his personal life.

He practiced a different segment of medicine, and very

infrequently he crossed my field of medicine. In other

words, I attend to my own business.

Q You mean you have never heard that Dr. Wilson

appeared at the hospital on numerous occasions apparently

under the Influence of alcohol?

A I have heard things like that. I have heard

things about lots of people.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Q But you have heard it about Dr. Wilson?

A I presume so, yes, sir.

MR. MELESNER: I have no further questions.

RECROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. HOGUE:

Q Doctor, the failure of a doctor to be elected

to the medical staff could be based on ethical and moral

grounds as well as medical competency] isn't that

correct?

A Correct.

MR, HOGUE: I have no further questions.

Signature of Witness:

L A W Y E R ’ S NOTES

Page Line

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

D R. W A L T E R L E E C R O U C H * h a v in g been d u ly

sworn, testified as follows:

DIRECT-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q Will you state your full name, please.

A Walter Lee Crouch.

Q You are a physician?

A I am a physician, a pediatrician.

Q How long have you practiced medicine?

A Nineteen years,

Q How many of those years in Wilmington?

A Thirteen.

q Are you on the staff of the James Walker Memorial

Hospital?

A I think so, the last time I heard.

Q Did you in December of 1964 and again in

February of 1965 receive a letter from the medical

staff president with respect to the application for

courtesy staff privileges of Dr. Eaton?

A Yes, sir.

Q Do you recall how you voted at those times?

A Yes. As well as I remember, I didn't reply,

which is an affirmative.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Q Do you attend meetings of the staff of the

James Walker Hospital?

A I do, but mainly the pediatric staff. You

see, we have the staff subdivided. We have quarterly

general staff meetings, and we have pediatric staff

meetings monthly except for the quarter in which we have

general staff meetings.

q With respect to the general staff meetings

do you recall the application of Dr. Eaton being dis

cussed?

A Yes, a little bit.

q What was the nature of the discussion?

A That this would happen if he wasn't put on

the staff. We were told that we had better see if we

couldn't get him on the staff, otherwise we would all

be subpoenaed.

q Who told you that?

A I have forgotten, I don't know whether it

came from the committee. But it was pretty obvious.

Q It came from someone on the staff?

A Oh, yesj they are the only people who attend

the staff meetings.

Q And they said — would you repeat what they

said?

A I'm not sure of the exact words.

30

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

1 Q Well, the general Idea.

A Ifcat we should vote for Dr. Eaton and get him

on the staff, otherwise it would go to court.

Q Is that why you voted for Dr, Eaton?

A No.

Q Why did you vote for him?

A Well, there's a great deal of consternation.

I have known Dr. Eaton ever since I have been practicing

here; and as far as I personally knew, everything that

I had heard against him you might consider hearsay.

Q You knew of nothing against him?

A Nothing of a concrete nature. Letters and

things like that that I had heard about him, written

by him, I hadn't seen. So rather than, you know, hold

a man guilty because of hearsay, it's a pretty bad

thing.

Q You have, in fact, referred patients to Dr.

Eaton, haven't you?

A Well, I used to do a great deal of work at

Community Hospital; and when he was on surgical call,

I'm sure some of those patients were seen by him.

Q Do you have a brother who is a physician here

in town?

A Yes, I do.

q Do you know that he referred patients to Dr.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Eaton a l s o ?

A I ’m sure so.

Q Well, you mentioned this matter of hearsay.

Isn’t it true that in a vote of this nature some of the

physicians can decide on the basi3 of hearsay whether

they want to support a man or reject him?

A I think that is always true.

Q There are no guidelines that you know of

which tell a man what to consider when he is voting?

A Not except for the statement we heard at the

staff meeting.

Q Which was: if you don’t vote for Dr. Eaton,

there will be more business in court.

A That’s right.

Q There was no talk about his ability?

A Well, I think so,

Q Who talked about his ability?

A As well as I remember, there was a presentation

of the credentials committee.

Q And that was favorable, wasn't it?

A As well as I remember.

q Does the credentials committee Investigate

a man’s qualifications?

A That is the purpose of the credentials committee,

it Is my understanding. It is very impersonal, supposedly.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

ll

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Q Is it your understanding that they would screen

out an incompetent man?

A That, theoretically, is the purpose of the

credentials committee.

Q Do you know of any immoral or unethical conduct

on the part of Dr. Eaton?

A None proven.

Q You say "proven") what do you mean by that?

A Well, you probably know of the recent case

of an abortion or something like that, penicillin reaction

or something, whatever it was.

Q Do you know what the disposition of that case

was?

A That*s what I say, "none proven." He was

found innocent.

Q So you don*t know of any actual Immoral or

unethical conduct on the part of Dr. Eaton?

A That*s right.

q Were you acquainted with a Dr. William J.

Wilson when he practiced in Wilmington?

A Vaguely. He left Just about the time I came

here.

q Do you know that Dr. Wilson was denied

courtesy staff privileges at the hospital at one time?

A Where - at James Walker?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

IS

2C

21

22

2;

2i-

2‘

Q Right.

A I wouldn’t be surprised.

Q Isn’t it true that it was common knowledge

around the community that Dr, ’ 'ilson appeared at the

hospital on numerous occasions apparently under the in

fluence of alcohol?

A I never saw him that viay, but that’s what I

heard.

Q Have you ever been acquainted with Dr. Kennon

C. Walden?

A No, not personally. I Just know of him.

Q Do you know what position he held?

A I think he used to work for the Coast Line.

q d o you know if Dr. Walden was denied courtesy

staff privileges at the hospital?

A TSiat was before I had a vote, I think. I was

on the courtesy staff for four or five years, ttiey re

wrote the constitution during that period, and I had to

wait until they got the constitution rewritten before

I could apply for attending staff. The courtesy staff

has no votes, so I didn’t vote on that.

Q But you do know that he was denied privileges?

A I remember something about It, yes, sir.

Q Wasn’t he denied privileges because of a

controversy between the railroad and the hospital?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

A I didn't realize such a controversy existed.

Of course, they could run all over the hospital.

Q Pardon me?

A They could run all over the hospital.

Q Do you know of any medical reason, any reason

having to do with his competence?

A I know nothing of Dr. Walden's competence.

Q Do you know anything of any immoral or un

ethical conduct on his part?

A I have heard of none.

Q Were you acquainted with Dr. George D. Lumb?

A Yes, sir,

Q What vias his specialty?

A Pathology.

Q Was he on the staff of the James Walker Hos

pital?

A Yes.

q Has he left the community?

A Yes; a3 far as I know, yes, sir.

Q Do you know where he has gone?

A New Jersey.

Q At these general staff meetings did Dr. Lumb

participate in the discussion about Dr. Eaton's applica

tion?

A I don't believe so. I don't believe he was

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

13

16

17

18

19

20

21

attending the meetings at that time, because I think he

already knew he was leaving* X can't swear to that* but

I don't recall having heard him discuss it. Let's see,

when did Dr, Lumb leave?

Q My information is that he resigned from the

staff the 31st of December 1964. Would that be in

accord with your memory?

A X would think it would be about that time. He

left shortly after the holidays, I believe; and I doubt

that he bothered to attend that meeting in December

because he was leaving, and he traveled a lot; and the

last meeting before that would have been the one three

months before, 30 I don't believe I heard him discuss

Dr. Eaton.

Q Are minutes of these general staff meetings

kept?

A I think so, yes, sir.

Q Do you think the discussion about Dr. Eaton's

application would have been recorded in the minutes?

A X would assume so.

MR. MELESNER; I have no further questions,

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. HOGUE;

Q Doctor, the procedure of the staff voting on

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

new applicants has been in existence ever 3ince you have

been on the staff, hasn't it?

A Yes, sir.

Q And this procedure has been used vrith respect

to both white and Negro applicants to the staff; is that

correot?

A Yes, sir.

Q Isn't it true that there are presently two

Negro doctors on the staff of the hospital?

A Yes, sir.

Q Dr, Wheeler and Dr. Roane; is that correct?

A Yes, sir.

MR. HOGUE: No further questions.

REDIRECT-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MELESNER:

q I Just have one question, Doctor. Isn't it

more or less routine for the medical 3taff to ratify

the report of the credentials committee on granting

courtesy staff privileges?

A I think they are accepted, and then they are

voted upon.

Q Can you think of a white physician in the

City of Wilmington who is not on the courtesy staff?

. •

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q Yes, sir.

A (No answer.)

Q It's pretty hard to think of one, isn’t

it?

A Well, no. I can name several, but I ’m not

sure whether they are on the staff now or not; Dr,

Mebane is, but I don't think Dr. Sinclair is.

Q But Dr. Sinclair was on the staff, wasn't

he?

A Yes, 3ir.

Q What I would like for you to name for me is

a white physician in the City of Wilmington who is not

on the staff now, who has not been on the staff.

A You mean other than retired?

Q, That's correct.

A You mean actively practicing medicine?

Q That's correct,

A Who lias never been on the staff at James

Walker?

Q That's correct.

A Dr, Andrews?

Q Pardon me ?

A You mean p r a c t i c in g in the C ity o f W ilm ington

p r a c t i c in g m e d ic in e?

A D r. Andrews?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q Yes, sir.

A (No answer.)

Q It's pretty hard to think of one, isn’t

it?

A Well, no. I can name several, but I ’m not

sure whether they are on the staff now or not; Dr.

Mebane is, but I don't think Dr. Sinclair is,

Q But Dr. Sinclair was on the staff, wasn't

he?

A Yes, sir.

Q What I would like for you to name for me is

a white physician in the City of Wilmington who is not

on the staff now, who has not been on the staff.

A You mean other than retired?

Q That's correct.

A You mean actively practicing medicine?

Q That's correct,

A Who lias never been on the staff at James

Walker?

Q That's correct.

A Dr. Andrews?

Q Pardon me ?

A You mean p r a c t i c in g in the C ity o f W ilm ington -

p r a c t i c in g m e d ic in e?

A Dr. Andrews?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Q Is it your answer that it's Dr. Andrews?

A No, I say Dr. — you have the list there; I

don't have the list.

Q My list reveals that every white physician

in the City of Wilmington---

MR. HOQUE: I want to object to that ques

tion as a statement of counsel which is going

to go into some details which should not go in

the record this way. I want to object to the

form of the question, if it is a question.

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q Doctor, you appear to be having some trouble

in naming a physician who you are reasonably certain is

not on the staff or was not on the staff; is that not

correct?

A Yes, sir.

Q You are having some trouble?

A Yes, because I don't have a list.

Q So most of the white physicians are on the

staff?

A Oh, yes, sir; and now most of the colored,

except for Dr. Upperman; I don't believe he applied. So

that's 50# of the colored physicians.

Q Did you make some reference earlier in your

testimony to sane letters written by Dr. Eaton?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

A When I first came here to practice, I had

heard somebody make the statement that there were some

letters in existence as to something to do with usual

referral fee3 or something like that, but I have never

seen the letter, and I am not sure who possesses the

letter. It has been several years — it's been thirteen

years or so. It wa3 back when I first came here to

practice, and a3 well as I remember all of the parties

concerned are dead; so I don’t know this and I haven't

seen it, so I tried not to let it influence my opinion.

MR. MELE3NER: No further questions.

MR. HOGUEs I have no further questions.

Signature of Witness:

L A W Y E R ’ S NOTES

P a g e L in e

41

1 D R . B R U C S H U G H D O R M A N , having been duly

2 sworn, testified as follows:

DIRECT-EXAMINATION

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

BY MR. MELE3NER:

Q State your full name and occupation, please.

A Bruce Hugh Dorman. I am a physician.

Q What is your specialty?

A Orthopedic surgery.

q Aire you on the attending staff of the James

Walker Memorial Hospital?

A Yes, I am.

Are you also on the staff of the Community

y

I'm on the consulting 3taff, yes, sir.

Have you performed surgery at both of these

Q

Hospital?

A

hospitals ?

A Yes, I have.

Q Do you know Dr. Hubert Eaton?

A Yes, I do.

Q Did you in December of 1964 and again in

February of 1965 receive a letter about Dr. Eaton's

application for courtesy privileges at the James Walker

Hospital?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A Ye3, I did.

Q What did you do with these letters?

A I voted and passed them in.

q You voted for Dr. Eaton; iB that correct, sir?

A X didn't say that, sir.

Q I thought you said "and passed him in"?

A No, sir. I voted and passed them in.

Q And "passed them in." In other words, you

returned the letter to the secretary or the president

of the medical staff with your ballot?

A Yes, I did.

Q On both occasions?

A I'm not sure; I think so, though.

Q How did you vote?

A I'm not going to divulge that information,

because I think this is prying into ray affairs as an

honest elector.

Q Would you repeat the answer? I'm sorry, I

didn't hear it.

A I say I consider myself an honest eleotor;

I voted by secret ballot, and I believe that I should

be protected under law to keep this information to my

self.

MR. MSLESNSR* Mr. Hogue, It is, of course,

my opinion that the witness has no privilege

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

13

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

to refuse to answer, and I will consider bring

ing this to the attention of the Judge so that

he can be ordered to answer the question.

MR. HOGUE: Well, as I understand it, he

says he doesn't want to divulge how he voted,

and that would appear to me to be an answer to

your question. I don't know. He's not my

witness; I can't make him answer or agree that

he should answer, because I don't think that

is within my power.

MR. MELESNER: I merely want to permit you

to advise the witness if you desire.

MR. HOGUE: Well, he is not my witness,

and I can't advise the witness one way or the

other. I don't think that that is my pre

rogative or position - to advise him. I haven't

looked into this matter but, of course, a

secret ballot should have oo?ne---

BY MR. MELESNER:

q For the record, Doctor, I'm going to ask you

the question again. How did you vote on the application

of Dr. Hubert Eaton for courtesy staff privileges in

December of 1964?

A With due respect to you, sir, it is none of

your business.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

13

16

17

q Again for the record, Doctor, how did you vote

on Dr. Eaton*s application in February of 1 9 6 5 ?

A I repeat the answer.

Q Doctor, are you a surgeon?

A An orthopedic surgeon, yes.

Q Is most of your surgery performed at a

hospital?

A Yes, it is, almost entirely.

Q Then I presume that a large portion of your

income is earned from this surgery?

A Yes, sir.

q So your income would be severely reduced if

you did not have the use of the operating facilities of

a hospital?

A That's correct, sir.

q And you think that you can deny another physician

the use of operating facilities and not tell him why?

A You are completely misinterpreting my answer,

sir. I didn’t say I voted against Dr. Eatonj I didn't

say that at all. I said that I'm not going to divulge to

you my answer, because I considered when I voted that

this was a secret ballot, and I just wish to stand on

my rights In preserving this secrecy.

q Well, now, some doctors voted against Dr.

Eaton, isn't that correct?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

li

A I don’t know how other people voted, 3ir,

and that’s the truth.

Q Do you know that Dr. Eaton Is not now on the

staff?

A That I know.

Q So would you conclude that some of them voted

against him?

A I would make that conclusion, yes.

q So you feel that the physicians who voted

against him have this right not to reveal how they voted?

A I think that the physicians who voted against

him have the absolute right to divulge this information

as much as they have if they voted against Lyndon Johnsoni

and I don't think they---

q This is like a fraternity, isn’t it? Anybody

can blackball someone without giving a reason?

A Goldwater was blackballed, sir.

Q Pardon me?

A Goldwater was blackballed.

Q It is your position that a nan can be refused

staff privileges and not given a reason?

A No, sir, I didn't say that.

Q Well, it’s your position that you don’t have

to give a reason?

A I didn't say that either, sir.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

Q Well, now, let me go over this again. You are

refusing to answer and tell me how you voted?

A I'm refusing to divulge Information to you

that I consider secret ballot, sirj that's all I'm re

fusing to do.

Q Doe3 that information include how you voted?

A Yes, It does.

Q And the reason for your vote?

A I didn't know I had to give a reason how I

voted.

Q You don't think you have to have a reason?

A Yes, I do.

Q You do have to have a reason?

A Ye3, sir.

Q But you are unwilling to state what that reason

was?

A If I gave you the reason why or how I voted,

you would know how I voted.

q So you are unwilling to tell us what the reason

is?

A I'm unwilling to tell you how I voted.

q Would you tell us what factual material you

used in coming to a decision?

A The case of Boyd and Teague, an old North

Carolina case, that stated: "An honest elector who has

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

observed the law enjoys the privilege, which is entirely

a personal one, of refusing to disclose, even under oath

as a witness, for whom he voted,”

Q, Who brought that case to your attention?

A My attorney,

Q May I have his name?

A It would be Lonnie Williams,

Q Pardon me?

A Lonnie Williams,

Q Does he have an office here in Wilmington?

A Yes, he does,

Q Now I am asking you, sir, what factual material

or data you used to base your decision on, and the decision

I am referring to is your vote on Dr, Eaton, I'm not

asking you how you voted, now, or your reason, I'm

asking you what factual material you used in reaching a

decision,

A I think I relied solely on Dr, Eaton's

caliber as a physician.

q Did you study his charts as a surgeon before

you voted?

A No, I didn't.

Q Have you ever observed Dr. Eaton in surgery?

A No, I haven't sir.

Q Doctor, I want to ask you to be as candid as you

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

ll

12

13

14

13

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

possibly can with me. Isn*t It true that If physicians

on the staff do not have to tell how they voted and

did not have to give a reason for their vote, that they

could reject a physician for any reason whatsoever?

A That*8 true, sir, yes.

Q It*s purely subjective?

A Truly.

Q Didn*t like the way he looks?

A That1s right.

Q Or the color of his hair?

A That *s right.

Q Race?

A That*s right.

MR. HOGUEi I want to object to the form

of those questions as being in the form of a

speech, and I don*t think it is proper in a

deposition of this kind for counsel for either

side to make a speech to the witness as to his

own thoughts and/or conclusions about the

matter.

BY MR. MEISSNER*

Q At the James Walker Memorial Hospital, then,

if more than 20# of the staff decide to keep a man off,

they can do so?

A Yes, sir.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

Q For any reason whatsoever?

A Yes, sir.

MR. MELESNER; I have no further questions.

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. H00UE:

Q Doctor, the procedure used with respect to

voting on Dr. Eaton, was that the procedure used when

you were first admitted to the staff?

A Yes, sir, it was.

q Is that the procedure that has been used with

respect to all applicants to the staff, whether white or

Negro, since you have been here?

A With one exception. At one time they asked us

to sign our ballots before they were counted, and I re

fused to do that. But this was not this particular case.

Q Now, I believe there are presently two

Negro physicians on the staff at James Walker Hospital,

is that correct?

A I believe there were three, but one of them

died.

Q There were three?

A I think so.

Q But one of them died?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

A Yes, sir.

Q That was Dr. Gray that died?

A Yes, sir.

Q And I believe Dr. William Wheeler and Dr.

Daniel Roane are presently on the staff?

A That's right, they are.

Q Do you know other white doctors have been re

jected from the staff since you have been here?

A I do.

Q You do know that?

A Yes.

Q What is it?

A They have been rejected, yes, several times.

Q They have been?

A Yes.

MR. HOGUEi That's all.

REDIRECT-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q Was Dr. Eaton's application discussed at a

staff meeting?

A I don't know if it was. If it was discussed

at a staff meeting, it was at one that I did not attend.

Q Do you know of any reason why Dr. Eaton was

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

li

denied staff privileges?

A No, I don't.

Q Do you know that since 19^5 only two white

physicians have been rejected for courtesy staff

privileges?

A I did not know that.

Q Are you aware that none of the Negro physicians

presently on the staff at James Walker were on the staff

before the lawsuit which Dr. Eaton brought was resolved?

A I wa3 aware of that, yes.

Q Are you aware of the fact that Dr. Eaton has

brought a suit on behalf of himself and his child to de

segregate the schools in Wilmington?

A I'm not aware of that, no,

Q When did you come to Wilmington, sir?

A I came to Wilmington in 1955.

Q Have you ever been acquainted with Dr, Kennon

C. Walden?

A What is the last name, sir?

Q, Walden, W-a-l-d-e-n.

A I don't think so.

q I am going to read you a paragraph which is

from a letter dated February 3# 1965* to Members of the

Attending Medical Staff of the James Walker Memorial

Hospital from Dr. Warshauer. I'm quoting now:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

"The secretary of the governing body, Mr,

Martin, has left it up to the medical members of the

Board of Managers, namely, Dr. Knox and Dr. Warshauer

to make the necessary explanations, and any member

wishing details in this regard may discuss the matter

with the medical members of the board."

Do you recall this paragraph?

A No, sir, I don't.

Q Do you have any idea what is meant by it?

A No, I don't know what they are talking about.

Q What are "the necessary explanations"?

A I don't know what they are talking about.

Q Would your recollection be helped if I told

you this appeared in a letter transmitting the second

ballot on Dr. Eaton's application?

A Yes, it would be.

Q Now what do you think is meant by this para

graph?

A Well, apparently they want to discuss the

matter further among themselves.

Q Do you have any idea what is meant by "the

necessary explanations"?

A Yes, I do.

Q What?

A They knew that they were going to have to

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

answer to people like you coming down here, and that they

felt they had better have some answers ready.

Q So that the staff would get together and

have some answers ready?

A Apparently so. I had no part of it.

Q Does that strike you as the usual practice -

to get together and make some explanations?

A No, sir. It Isn't the usual practice.

Q Does it suggest to you that perhaps there

was something very different about Dr. Eaton's application?

A Yes, sir, it does.

q Do you have any idea what that something

different was?

A Yes, sir, I do.

Q You think it might have something to do with

this lawsuit?

A Yes.

q What do you think it was?

A I believe the way I would interpret it is that

they felt that if Dr. Eaton's privileges were denied

that there was going to have to be an awful lot of

answering, because they figured that there would be a

deposition of this sort.

Q In other words, their real reasons weren't

enough?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

li

A No, the r e a l rea son s a p p a re n tly had to be e x

plained.

Q But you are unwilling to explain your3?

A I am unwilling to tell you how I voted.

Q You are now willing to tell me how you voted?

A I'm not willing to tell you my rationale, be

cause if I told you my rationale that would tell you how

I voted. I consider this a sacred right as I always

have. May I interject something, please, sir?

Q If you will excuse me, sir, not right at this

moment.

MR. MELESNER: I have no further questions.

THE WITNESS: May I interject something

now, sir?

MR. HOGUE: You can certainly explain any

answer that you have made.

MR. MELESNER: I don't—

MR. HOGUE: I would think that he would

have the right to explain any answer he has

made.

THE WITNESS: During this whole inquest

with me - I believe if this case is reviewed -

my entire answering system is going to be mis

interpreted, I'm certain of that.

Now, I never said I voted against Dr.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Eaton; I never said I voted for him either.

I am from New Jersey - I'm not from the South -

I lived there all ay life. The only thing that

I resent is having to divulge what I consider

a sacred right; and that is all I have said

during this entire inquest. I did not say I

am against Dr. Eaton; I did not say I am for

him.

MR. HOGUE: I have no further questions.

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q, Let me Just go over one or two more matters,

sir. Do you know basically what the purpose of this

deposition is?

A Yes, I do.

Q Do you know that we are alleging that Dr.

Eaton was wrongfully denied staff privileges?

A I believe that is my interpretation of it,

yes.

MR. HOGUE: Now I object to that and wish

to put this in the record: I say that the pur

pose of this deposition is to 3how that Dr.

Eaton was denied this application on the basis

of his race, and that that is all that Is before

the hearing; not that he was wrongfully denied,

but the motion for contempt states that he was

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

13

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

denied staff privileges by reason of his race.

Consequently, I feel that I must make that

statement to the record for clarification.

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q Are you aware, also, that it has been alleged

that Dr. Eaton was denied staff privileges because of his

race?

A Yes, sir.

Q To your knowledge, Doctor, was there any group

or clique of doctors at the hospital who were especially

interested in denying staff membership to Dr. Eaton?

A To my knowledge I would say that's correct.

Q There was such a group?

A I would say that's correctj I don't know what

the group was.

Q Do you think race played a part?

A I think yes. I think it did play a part.

MR. MELESNER: I have no further ques

tions.

RECROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. HOGUE:

Q Now, Doctor, you have no knowledge as to whether

race played a part in his denial or not, do you?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

A I don't have any direct knowledge. I don't

know if I was supposed to answer when my opinion was

asked, because that would be hearsay.

Q Anything you are basing that on is pure

hearsay?

A Yes, it is.

Q Do you know how any other doctors voted in

this matter? r

y ' _ i t y d g Z 'A No, I do not. 6

Q Do you know the names of any -other doctors

who voted against Dr. Eaton?

A I do not.

q, So you don't know what their votes were based

on at all, do you?

A No, I don't.

Q And that application was handled Just like

any other application, whether the physician was a

Negro or a white person; is that correct?

MR. MELESNER: We object to that.

BY MR. HOGUE:

Q The voting on that application was handled

Just like any other applicant to the staff, isn't that

true. Doctor?

A Yes, it was.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

REDIRECT-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MELE3NER:

q This hearsay you talked about, Doctor - did

you hear it talked about among other physicians?

MR. HOGUE: Objection.

A Yes.

q Was the president of the medical staff one of

these physicians?

A I don't believe so.

Q Was the secretary of the medical staff, Dr.

Singletary, one of these physicians?

A No.

MR. MELESNER: That is all.

MR. HOGUE: I have no further questions.

Signature of Witness:

L A W Y E R ’ S N O T E S

P a g e L in e 0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

13

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

p r . J A M E S F. G I B S O N , having been duly sworn,

testified as follows:

DIRECT-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q Will you state your full name and profession,

please.

A James Franklin Gibson, M.D., surgeon.

Q Surgery is your specialty?

A Yes.

Q Are you on the staff of the James Walker Memorial

Hospital?

A Yes.

Q How long have you been on the staff?

A Approximately three years.

Q Are you on the staff of the Community Hospital?

A Yes.

Q How long have you been on the staff of the

Community Hospital?

A Approximately the same length of time.

Q Have you held any positions on the staff of

the Community Hospital?

A Yes.

Q Y.Toat position?

60

1 A Chief of Staff.

2 Q As Chief of Staff would you he Dr. Eaton's

3 superior?

4 A Would be the central coordinator of the medical

5 services, yes.

6 Q Would you have knowledge of his performance

7 as a physician at that hospital?

8 A Yes. i

9 Q What is your knowledge of Dr. Eaton?

10 A I feel that he i3 a competent practicing

li physician in the hospital - physician and surgeon.

12 Q Have you ever known him to do anything immoral

13 or unethical?

14 A No.

15 Q Do you know of any defect in training or

l6 competence which he might have which would serve to ex

17 plain why he has been denied staff membership at the

18 James Walker Hospital?

19 A No, sir.

20 Q As far as you know his reputation and competence

21 are good?

22 A Yes.

23 Q Do you have any idea why he was denied staff

24 membership?

25 A None specifically.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Q Is there any legitimate explanation in your

view for his denial of staff membership?

A From facts or opinion or both?

Q what I am aBking is what your opinion is.

A No, I see no reason why he should not be

accepted on the hospital staff.

Q Did you vote for him?

A Yes.

Q On both occasions?

A Yes,

Q Did you attend meetings of the general medical

staff of James Walker about the time these applications

were pending?

A The credentials board presented the applicants

only in passing at the meeting which I attended. I was

absent from meetings which may have delved into discussions

regarding this.

Q Was there any discussion at the meeting which

you did attend?

A Only Just colored doctors in general when

all the applications, the initial applications came in.

I believe Dr. Gray's came in first.

Q Are you aware of certain lawsuits brought by

Dr. Saton which relate to civil rights?

A Only the one relative to this.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

A Yes, the one I was subpoeaned for*

Q Do you think Dr. Eaton's race played a part

in the denial of staff membership?

A I would think by deduction, no.

Q Sir?

A I would think by deducting, no. There are

other colored physicians on the staff.

Q How would you explain it?

A I have no explanation.

Q There isn't any valid reason that you know of

which relates to medical competence, is there?

A No.

Q Is there any which relates to his ethics or

morals?

A The form of it would be only conjecture. I

know of no specific instances that I could document right

off-hand.

Q Do you know of any at all, whether you can

document them or not - instances of immoral or unethical

conduct on the part of Dr. Eaton?

A No.

Q Describe for me how you understand the pro

cedure whereby the staff acts on an application for

membership at James VJalker,

Q You mean the s u i t a g a in s t the h o s p i t a l?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

ll

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A The applicant files a form with the medical

staff which in turn is reviewed by the credentials

committee and then presented for approval by the general

medical staff. Prom this point a recommendation of

acceptance or rejection is made to the Board of Governors

who have the final voice or say-so or approval in

running the hospital matters. Though they usually take

the medical staff's recommendations, they may refuse

them.

Q And I believe that a successful applicant must

get 80# of the vote?

A I'm not familiar exactly with the figure,

but I believe that's correct; that's what stands in my

mind.

Q Veil, assuming that it i3 80^, doesn't that

mean that a small number of doctors could keep another

doctor from staff membership?

A Well, ten out of forty, certainly.

Q As you understand the bylaws of the hospital,

could they do this without giving any reason for their

action?

A I have heard pros and cons. I have always

been under the impression, though, that a reason was

given; I have heard to the effect of the opposite

though.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q You a re unsure w hether o r n ot a rea son f o r

rejection is given?

A Correct,

Q Have you spoken with any physician who voted

against Dr. Eaton?

A No, I don't know how anybody voted.

Q Are you familiar with the existence of a group

or clique of physicians on the staff of James Walker Hospital

who wanted to keep Dr, Eaton off the staff?

A I am not familiar with a clique, no.

Q Are you familiar with the existence of such a

clique or group?

A Only through rumors.

Q You have heard rumors to that effect?

A I have only heard it alluded to.

Q Will you tell me the nature of the allusion?

A Just that when the discussion of whether or

not Dr, Eaton was accepted on the staff, an incidental

comment by a person discussing it who said/^ ^eJriy x

there's a group out that would like to keep Dr, Eaton

Off."^

Q Was the reason alluded to - the reason they

wanted to keep him off?

A This would be information which is strictly

hearsay.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

MR. H0QUE: If the doctor wants to object,

I will put a formal objection in the record

now. 1*11 put a more formal one in later.

BY MR. MELESNER:

Q Doctor, you understand it's this decision

we are talking about, and the only way we can ask you

about it is in this manner. An objection has been noted

for the record. I wish you would answer the question as

best you can.

A At the time an event - at which time I was

not present and practicing in the City of Wilmington,

North Carolina - took place which seems to be relative

to the rumors or the word3 that I have heard by conversa

tion to the extent of a hospital bond issue - the

controversy -as toeing Dr. Eaton’s stand as compared to

other peoples’ stands.

Q What was Dr. Eaton's stand?

A I believe Dr. Eaton was against the bond

issue.

Q And these other people were for it?

A Yes.

Q And what was the bond issue for?

A A new hospital.

Q What is the name of the hospital?

Q We’ l l l e t the judge d e c id e t h a t .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

li

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A New Hanover Memorial Hospital.

Q Is this the new hospital that is going up right

now?

A Yes.

Q I believe that Community and James Walker

will eventually be closed and merge into one hospital!

is that oorrect?

A They will be closed and become the one

hospital. Now, the Board of Governors will be an entirely

new board) it has already been appointed and ia functioning.

The James Walker Board of Governors will not be the

Board of Governors of the New Hanover Memorial Hospital,

and neither will the Board of Governors of the Community

Hospital, though there will be common membership, I

believe. I know of one named that will be common.

Q Do you know why Dr. Eaton opposed this bond

issue ?

A I think, possibly as a physician, he felt

there were enough beds.

Q Pardon?

A He, possibly as a physician, felt that there

were enough beds to satisfy the medical needs.

Q Do you think it might have had something to

do with the fear of Negro physicians that they wouldn*t

get fair treatment at this new hospital0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

n

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25