Plaintiffs' Response and Motion for Order Allowing Plaintiffs to Present Desegregation Plan at the Board's Expense

Public Court Documents

December 9, 1971

21 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Response and Motion for Order Allowing Plaintiffs to Present Desegregation Plan at the Board's Expense, 1971. 87e7868c-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5bbfee77-b666-40ae-9bad-142dfa461d63/plaintiffs-response-and-motion-for-order-allowing-plaintiffs-to-present-desegregation-plan-at-the-boards-expense. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

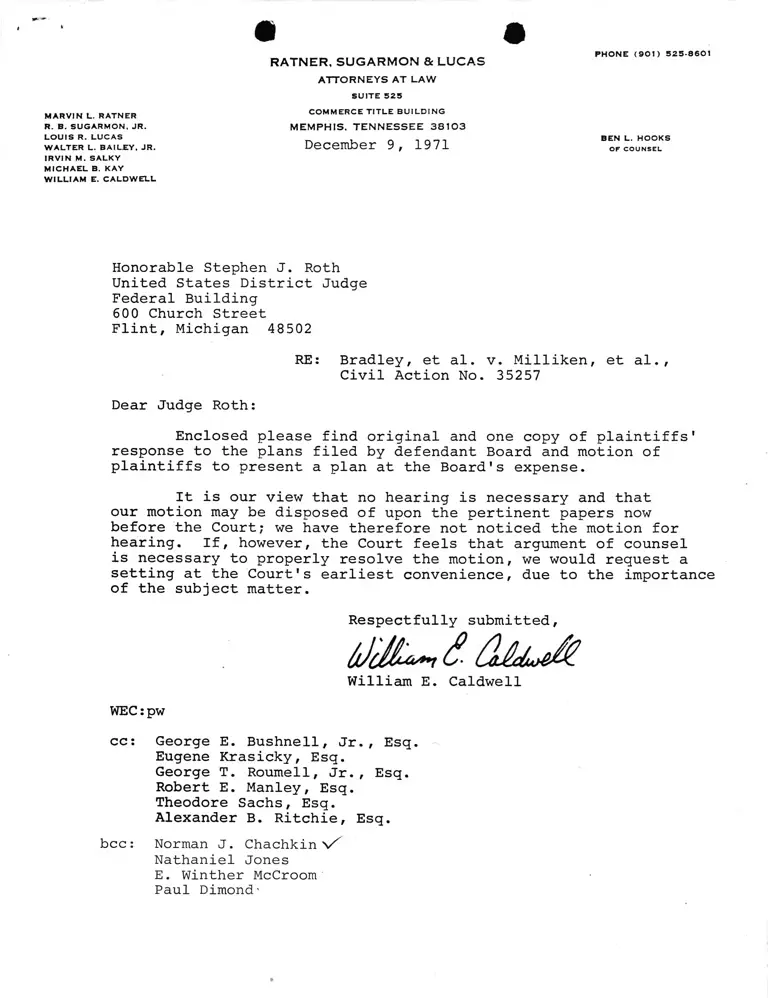

RATNER, SUGARMON & LUCAS

A T T O R N E Y S A T L A W

P H O N E ( 9 0 1 ) 5 2 5 - 8 6 0 1

S U I T E 5 2 5

M A R V I N L . R A T N E R

R . B . S U G A R M O N , J R .

L O U I S R . L U C A S

W A L T E R L . B A I L E Y . J R .

I R V I N M . S A L K Y

M I C H A E L B. K A Y

W I L L I A M E. C A L D W E L L

C O M M E R C E T I T L E B U I L D I N G

M E M P H IS , T E N N E S S E E 3 8 1 0 3

December 9, 1971 B E N L . H O O K S

OF C O U N S E L

Honorable Stephen J. Roth

United States District Judge

Federal Building

600 Church Street

Flint, Michigan 48502

Enclosed please find original and one copy of plaintiffs'

response to the plans filed by defendant Board and motion of

plaintiffs to present a plan at the Board's expense.

It is our view that no hearing is necessary and that

our motion may be disposed of upon the pertinent papers now

before the Court; we have therefore not noticed the motion for

hearing. If, however, the Court feels that argument of counsel

is necessary to properly resolve the motion, we would request a

setting at the Court's earliest convenience, due to the importance of the subject matter.

WECrpw

cc: George E. Bushnell, Jr., Esq.

Eugene Krasicky, Esq.

George T. Roumell, Jr., Esq.

Robert E. Manley, Esq.

Theodore Sachs, Esq.

Alexander B. Ritchie, Esq.

bcc: Norman J. Chachkin n/

Nathaniel Jones

E. Winther McCroom

Paul Dimond'

RE: Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al.,

Civil Action No. 35257

Dear Judge Roth

Respectfully submitted,

William E. Caldwell

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al., )

Plaintiffs, )

vs. )

WILLIAM J. MILLIKEN, et al. , )

Defendants, )

and ) CIVIL ACTION

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, ) No. 35257LOCAL No. 231, AMERICAN FED

ERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO, )

Defendant-Intervenor, )

and )

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al., )

Defendants-Intervenor. )

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO BOARD'S "PLANS" AND MOTION FOR ORDER

ALLOWING PLAINTIFFS TO PRESENT DESEGREGATION PLAN AT THE

BOARD'S EXPENSE

On December 3, 1971, the defendant, Board of Education of

the City of Detroit, filed a document with attachments entitled

"Compliance With Court Order of November 5, 1971 And Request For

Hearing." Despite the self-serving title, plaintiffs respectfully

submit that the submission of the Board does not even approach com

pliance with the Court's order of November 5, 1971. For reasons

more fully set forth below, plaintiffs object to the plans submitted

by the Board and move the Court for an order permitting plaintiffs

to present a plan of desegregation for the Detroit school system at

the expense of defendant Board.

On October 4, 1971, the Court allowed the defendant, Detroit

Board of Education, sixty (60) days within which to submit a plan for

the desegregation of the Detroit school system— i.e., a plan which

would "achieve the greatest possible degree of actual desegregation,

taking into account the practicalities of the situation," Oct. 4,

1971 Tr. at 6 (quoting from Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs, 91

S. Ct. 1279, 1292 (1971)). The Board's submissions of December 3,

1971 constitute a patent disregard for the Court's order; the sub

missions reflect that the Board has devoted the entire sixty days,

not to development of a plan of desegregation, but to devising new

terminology for "freedom of choice" (now "Improved Incentives").

In support of our objection to the plans submitted by the

Board, we adopt and incorporate herein by reference "Plaintiffs'

Response to Defendant Detroit Board's Report on the Magnet School

Program" [hereafter, "Response"], previously filed in response to

the Board's November 3 submission on the Magnet School Program.

At page 12 of our Response we alleged "that the Board is rejecting

consideration of desegregation plans proposed by its staff which

place the burden of school desegregation where it belongs, on school

authorities not the children and parents." The most recent sub

mission by the Board verifies that allegation, and we reiterate what

we said in our Response: "we respectfully submit that any presen

tation to this Court by the Board...of a desegregation plan which

is based on a magnet-type principle constitutes bad faith." (Response

at 12) .

Although our previous response to the Magnet report applies

to Plans A and C with equal force and relevancy, we add here a few

brief comments about these new efforts to circumvent plaintiffs'

constitutional rights.

Plan A Perpetuates The Ineffective Magnet School Program, Is Based

On White Racism, and Does Not Desegregate The Detroit Public Schools

Plan A contemplates an expansion of the Magnet High School

and Magnet Middle School programs. For the reasons stated in our

previous response to the magnet school report this plan is uncon

stitutional on its face. Even the self-serving projections contained

at page 12 of the plan purport to affect only 42,000 pupils out of

2

Detroit's total public school population of over 275,000 pupils.—^

And even these meager projections will not be effectuated for at

least four years.

Plan A would continue the Magnet High School and Magnet

Middle School programs, with the following additions:

(1) One "academic high school" would be established in

each of the four paired regions with each such high school to have

a maximum capacity of 1,500 students. It is not clear whether this

part of the plan contemplates the construction of four new high

schools (a process which previous testimony in this case indicates

would take at least two years), or whether existing high schools

would be converted to "academic high schools." At any rate, "site

selection by regional boards and procedures for applications will

be developed later." (Plan A at 3). The "academic high schools"

would operate in a manner similar to the present middle school pro

gram with its demonstrated inadequacies. (See Response at 6-8).

(2) The existing Magnet High School program would be

modified so that "each high school will become more specialized

and will not compete with other high schools in the paired regions."

(Plan A at 3). The plan also contemplates expansion of the areas

of specialization and emphasis, as well as refinement and restruc

turing thereof. (Plan A at 3-4). In any event (and contrary to

Alexander v. Holmes County Board, 396 U.S. 19 (1969)), this aspect

of Plan A will not become fully effective until the beginning of

the 1975-76 school year. (Plan A at 3).

(3) Another high school level aspect of Plan A has to do

with the equalization of grade levels "so that all students attending

a given school will have an equal experience in that school, and so

that the ninth grade will not be racially skewed in comparison with

other grades in the same school" (Plan A at 5). Whatever this

aspect of Plan A means, it does not appear to advance the cause of

1/ By saying that 42,000 pupils will be affected by Plan A does

not, of course, mean that 42,000 additional pupils will have

an integrated education. As pointed out in our Response,the magnet

school approach serves to perpetuate and create segregation more

than it does to alleviate it.

3

integration in the Detroit school system nor does it purport to

be a device for increasing desegregation. The ambiguous state

ment just quoted from the plan is preceded by a statement which

is even less comprehensible: "Students will attend their present

elementary and junior high school, but may be advanced into a

senior high school with a larger service area at a lower grade

level." From the prior testimony in this cause regarding over

crowding at most white high schools and at some black high schools,

plaintiffs do not comprehend how a Detroit high school service

area can be expanded and at the same time additional grade levels

be added (other than at the undercrowded black high schools which

are located in black regions where expansion of the service area

will not futher desegregation). Nevertheless, nothing contained

in the section of Plan A entitled "Equalized Grade Entrance" has

anything to do with increasing the degree of integration in Detroit

high schools.

(4) The fourth aspect of Plan A has to do with an expansion

of the Magnet Middle School concept. In our previous Response to

the Magnet School Program report we noted (p. 6) the Board's failure

to admit "the absolute bankruptcy of the concept of the Magnet

Middle School as a plan of desegregation" and stated our "fear that

we may hear all too much about the concept in the future." Again

our fears have been borne out in the Board's submission of Plan A.

Once again the Board proposes to make some schools in Detroit better

than other schools and to give some students (in projected integrated

schools) a better education than other students (in continued

segregated schools). Plan A comprehends that the present eight

middle schools would remain; that each of the eight regions would

establish at least two new magnet middle schools for grades 6-8;

and that each region would establish at least two new magnet ele

mentary schools for grades 3-5. Thus, the plan comprehends rather

than just one projected!/ integrated school in each region there

V We use "projected" in a light favorable to the Board, notwith

standing the fact that prior experience with the magnet middle

school concept demonstrates (1) that the Board's projections will

not come to pass and (2) that whatever integration does occur will be

to the detriment of existing integration in other Detroit schools.

(See Response at 6-8). Our point is that taking Plan A and the

Board's projections at face value, the plan is patently inadequate to

remedy the existing segregation,even by 1975.

4

would be five projected integrated schools in each region, three

serving grades 6-8 and two serving grades 3-5. The segregated

attendance pattern in grades one and two would continue through

out the system as would most of the other grade levels in the

Detroit schools. Once again, however, whatever integration occurs

depends upon the choice of parents and pupils. The Board again

refuses to assign pupils to integrated schools, perhaps because of

its desire to have "a wholesome, safe, non-coerced integrated

experience for school children" (Plan A at 10). The Board does

offer "additional funds in the amount of $30-$150 per student"

(Plan A at 8) for those middle schools which do attain integration,

but this offer will obviously not attract many white students from

white schools since, as previous proof shows, white schools already

receive more Board dollars per pupil than do black schools.

(Plaintiffs' Trial Exhibits 163 A-C, 164 A-C, 163 AA-CC; Defendants'

Trial Exhibit NNN; 41 Tr. 4665-66). In any event, the fact that the

Board has offered to pay black and white children to attend school

together hardly constitutes compliance with the constitutional

obligation imposed by this Court that the Board operate integrated

schools.

(5) The fifth general aspect of Plan A has to do with

allowing majority-to-minority transfers and providing transportation

therefor. Swann does require such a transfer provision, but only

after "every effort" has been made to "achieve the greatest possible

degree of actual desegregation, taking into account the practicalities

of the situation." Majority-to-minority transfers are not substitutes

for this primary obligation; only after the Board has complied with

its main responsibility need we concern ourselves with whether or

not a transfer provision is required.

Some additional comments are in order regarding Plan A.

One concerns the Board's attempt to insulate itself from the Court

by interjection of the regional boards. At page 9 of Plan A the

Board says:

5

• ' ......~ “ ... • ................

Decision making with regard to site

selection and other items relating to

implementation of this proposal shall

reside with the respective regions,

subject only to the present decentral

ization guidelines and the provisions

of this proposal as may be embodied in

a Federal Court order.

We emphasize that the constitutional obligations declared by the

Court's ruling of September 27, 1971, are imposed upon the Detroit

Board of Education, and it, like the State, may not constitutionally

pass the buck to sub-units such as regional boards.2/

Secondly, we perceive another evasion in Plan A's expressed

concern regarding space availability in Detroit schools. At page 11,

Plan A speaks of various alternatives such as renting parochial

buildings, redesignating existing buildings, new construction and

double sessions. This expressed concern, though false, reflects the

Board's continued refusal to utilize the 22,961 vacant seats in schools

90% or more black. (See Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 12).

Finally, we note the true reason for the Board's continued

refusal (by the submission of Plans A and C) to offer meaningful

desegregation plans for Detroit — i.e., that portion of the December 3

resolution which states that "continuing decreases in the percentages

of both white pupils and middle income families in Detroit have made

effective integration within the city limits impossible." As was

made clear at the trial on the merits, the Board equates "middle

income" with "white" and "low income" with "black." The Board's

position now, as it was then, is that integration will not succeed

unless a majority of the pupils are white. The racism inherent in

this "white majority thesis" was pointed out in our previous Response

to the Magnet School Program report, at pages 10-12. For the reasons

there stated, such justifications for continued segregation may not be

allowed. We are constrained to add, however, that Plan A embodies

more than a mere unwillingness to desegregate because the system is

V That this is what the Central Board is attempting to do appears

clearly on page 11 of Plan A: "In order to provide dollar

incentives to Regional Boards for optimum racial balances, special

funds will be sought from the State Board of Education." {emphasis added).

6

majority black. We are confident that Plan A would be submitted to

the Court by the driving (predominantly white) forces of this Board

of Education even if the Detroit system were 65% white. For the

true thesis of Plan A is "free choice," and "free choice" plans have

been and are proposed only by those who are opposed to desegregation;

they are proposed by Boards of Education which seek to accomodate

the hostility of the white community to sending their children to

school with black students.£/ This we submit is the motivation behind

Plan A and, as such, it constitutes an insult to black Detroiters

equalled only by the past policies and practices of segregation as

found by the Court in its ruling of September 27, 1971.

Plan C is not a Plan of Desegregation

Plan C proposes part-time (equivalent of 1 day a week)

desegregation for grades 3-6 in schools over 80% black or 80% white

"for special programs in humanities." (Plan C at 2). Plan C does

nothing to alleviate segregation in other racially identifiable

schools, nor does it even speak to the problem of segregation in

grades 1-2 and 7-12. But even more critical, Plan C is not sufficient

to meet defendants' affirmative duty to disestablish segregation in

grades 3-6 in the schools which are affected by the plan. Plans of

part-time desegregation have been consistently rejected as remedies

for full-time segregation. See, e.g., United States v. Board of

Education of Webster County, 431 F.2d 59, 61 (5th Cir. 1970); United

States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County, 423 F.2d 1013 (5th Cir.

1970). The Board is required to accomplish integration within the

regular school program; proposals for extracurricular cross-racial

contact are not only inadequate, they are demeaning.

£/ The record in this cause is replete with evidence of white

Detroit's hostility to racial integration. This hostility

was most notably manifested in the recall movement spawned by the

April 7, 1970 plan of partial desegregation. (See Hearinq Trans

cript of 11/18/70 at p. 160 (Board Member Dr. Golightly)).

7

Neither Plan A Nor Plan C Presents Any Question Which Calls For A

Hearing -- A Hearing Would Serve Only To Delay Vindication of

Plaintiffs' Constitutional Rights "

Plaintiffs submit that no hearing need be held at this time

on the submissions of Plans A and C by the defendant Board. First,

neither of the plans contain the specifics necessary for approval

by the Court. The plans do not designate schools or school sites;

grade organizations and methods of pupil assignment are left to the

future; attendance area boundaries are absent, as are specific school-

by-school projections as to the plans' effects on segregation. Further

more, the critical statistics which we urged as necessary in our

Response (at 8-9) are not contained in either plan. In short, there

is nothing to have a hearing on; no meaningful decree could possibly

be formulated on the basis of the so-called "plans," as submitted.

4

For the reasons just noted, a hearing on the Board's plans

would not be beneficial to the Court or the parties; there is no

meaningful factual controversy to be resolved. The only issue which

requires resolution does not require an evidentiary hearing — i.e.,

may Detroit operate a freedom—of-choice plan as a remedy for the

system-wide segregation it has created, fostered, and perpetuated,

or will it be required to implement a plan of school desegregation

as required by Swann and Davis and this Court? 1/ The answer to this

issue is, of course, found in the law, and no matter how much defendant

Board and some of its individual members prefer freedom of choice, the

law does not permit it. We find our position nowhere better expressed

than in the attached Detroit Free Press editorial of November 27, 1971:

The Detroit Board of Education's proposal

to meet a court order requiring an accep

table plan for desegregating the city's

schools are more than an effort to maintain

things as they are. They are cynical attempts

to dodge the issue and force the courts to

take the burden of unpopular decisions.

* * * *

[M]ostly the plans are a rehash of the magnet

and middle school programs already in operation

which have proved almost totally ineffective in equalizing educational opportunity.

5/ See also Bradley v\_ Milliken, 438 F.2d 945, 947 n.l (6th Cir.

^1971)i (citing Supreme Court decisions which rejict "free

choice" plans because of their demonstrated failures to achieve desegregation) .

8

Basically, they all involve freedom of

choice, a concept which has perpetuated

school segregation around the nation and

has been rejected repeatedly by the courts.

* * * *

The Board of Education is not even close

to meeting the requirements of the law of

the land. The longer its members resist

that, the more expensive and painful it is

going to be to pick up the pieces later.

The Court Should Permit Plaintiffs To Present A Plan of Desegregation

For Detroit At The Expense of Defendant Board

Clearly, the Board has defaulted in its constitutional

obligations and has failed to comply with the Court's directives.

This default is apparently premised on the Board's preference for a

metropolitan solution, and the Board appears to take considerable

comfort from that portion of the order requiring the State Board to

submit a metropolitan plan sixty days hence. The fact that the State

Board also has an obligation does not, however, relieve the Detroit

Board of its responsibilities. Furthermore, the Court has not decided

the issue of metropolitan relief, and until that issue is ultimately

resolved the Detroit Board is constitutionally bound to eliminate

the segregation that exists within its present boundaries. §/

-/ },n i^S Memorandum Brief (at p. 4) defendant Board properly"defines desegregation as a situation in which black and

white pupils go to the same schools and the same classrooms...,"

and it is true, as defendants say (ibid.), that "one must have

an appreciable number of white as well as of black pupils in order

to desegregate." But Detroit is hardly an all-black school system;

as defendants also note in their brief, Detroit is 36.2% white.

Such a large percentage of whites is certainly not de minimis non

curat lex. We but state the obvious to anyone who follows school

desegregation matters when we point out that almost daily in this

country school systems which are 36% black (or less) are being

ordered to desegregate, and are desegregating. And this is being

done without inquiry or concern about the "socioeconomic status"

of the majority white pupils in these many systems. What then makes

Detroit different? The answer is, nothing, except that Detroit is

majority black, not white. That this excuse is born of racism is

demonstrated by the fact that the Detroit Board made absolutely no

efforts in 1950 or 1960 (when the system was majority white) to

advance^integration. (On the contrary, at those times the Board

was actively pursuing a practice of segregation!) The present

majority black status of the system cannot justify segregation any

more than did its 1960 majority white status. Nor do belated labels

such as "socioeconomic status" and "middle income families" alter these truisms.

9

S S a s g ^ i- -- «*«;■ -sarSt̂sSjgSsjfc-' i

The law requires that effective, though imperfect, interim plans

be implemented while broader plans are being prepared, or broader

issues resolved. Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd. , 396

U.S. 226 (1969), 396 U.S. 290 (1970); United States v. Board of

Educ. of Baldwin County, supra, 423 F.2d at 1014.

One of the more damaging aspects of the Board's default

is that the Court and the parties will be without a model for

comparison with the plan to be filed by the State Board (assuming

that the State Board responds in better faith than has the Detroit

Board). On the one hand, Detroit claims that a desegregation plan

confined to the city' s political boundaries is not sufficient and

that, therefore, metropolitan relief is necessary; on the other

hand, the Board merely rests on this assumption and refuses to

submit a plan achieving the greatest possible degree of actual

desegregation, as required by the Court's order. The Court and the

parties are thus left to evaluate the Board's contention and,

ultimately, the State Board's plan without the benefit of some

very crucial information — namely, what desegregation can be

accomplished(and with what effort) within the City of Detroit?

Ordinarily, the Court's contempt power would provide an

adequate remedy for the disregard or default of court-imposed duties.

But contempt is a rather empty remedy for defaults, such as the one

here, which affect the constitutional rights of thousands of school

children. Furthermore, plaintiffs did not institute this litigation

to have defendants fined or jailed, but to secure for themselves

constitutionally guaranteed equal educational opportunities. What

this means, translated into the present posture of the case, is a

plan of desegregation for Detroit.

Plaintiffs would exercise their option under the November 5

order and present an alternate (actually, it would be the only) plan

of desegregation for Detroit, save for one factor: the substantial

(for plaintiffs) expense of preparing a detailed plan of desegregation

for the city. Dr. Gordon Foster, Director of the Title IV Desegre

gation Center at the University of Miami (who was qualified as a

desegregation expert at the trial on the merits in this case) has,

provided plaintiffs an estimate that he and another expert in

10 -

desegregation planning (Dr. Michael Stoley, Associate Dean, School

of Education, University of Miami, formerly Director of the Title

IV Center), along with two full-time staff members and a secretary,

could prepare a detailed, desegregated pupil assignment plan (with

attendance boundaries, grade structures and transportation estimates)

for Detroit within 20 days, at a maximum estimated cost of $20,000.

The estimate breaks down like this:

2 full-time experts at $200 each per day......... $8,000

2 full-time support staff at $75 each per day.... 3,000

Living expenses for 4 ............................ 2,800

Car rental ....................................... 1,250

Air travel for 4 (4 trips) ...................... 3,520

Secretary ........................................ 500

Architectural draftsman and maps and overlays.... 1,0 00

Because of Dr. Foster's familarity with the system, and

because of the existence of already-prepared maps and documents

(trial exhibits) reflecting school boundaries, capacities, etc., the

time, and thereby the expense, for preparing a plan may well be less

than the above estimate. In addition, considerable savings would

result from the provision by the Board of the two full-time support

personnel and the secretary. Further additional savings will result,

of course, from full cooperation by the Board and its staff. (We

do not mean to intimate, however, that we think the maximum estimate

of $20,000 is unreasonable for preparation of a plan which would at

least result in partial vindication of plaintiffs' constitutional

rights. Indeed, a mere $20,000 price tag is a gift compared to the

more than $300,000 spent on preparation of the ineffective Magnet

School Program.)

Although the projected cost of a meaningful desegregation

plan is more than reasonable when compared to the Board's expendi

tures for plans which even a majority of the Board and its staff

believed would fail (see Reponse at 5), it is a burden which

plaintiffs find difficult to bear. The Board has demanded from the

outset that plaintiffs dot every "i" and cross every "t" in proving

our allegations of unlawful discrimination. And plaintiffs have

painstakingly, at great cost in money and time of Court and counsel,

spelled 'segregation." Plaintiffs, who are Detroit taxpayers,

therefore move the Court to require the Board to bear the reasonable

11

costs for preparation of a plan to disestablish the system-wide

segregation which the Board in large part created. We base this

request, however, not upon plaintiffs lack of financial resources,

but upon (1) the primary obligation of the Board to desegregate

the system, and (2) the Board's patent default in the submission

of a true plan of desegregation.

We urge here the result reached in less compelling circum

stances in Jackson v. School Board of Lynchburg, Civ. No. 534 (W.D.

Va. April 28, 1970) (order and opinion attached hereto), wherein the

court authorized plaintiffs, because of the system's apparent default,

to prepare a plan of desegregation at the system's expense. Only by

granting plaintiffs the relief prayed for herein will a meaningful

start toward alleviating segregation and segregation effects in

Detroit be made. Furthermore, only by permitting plaintiffs to present

a plan for Detroit will the Court and the parties be in a position to

(1) determine the need for metropolitan relief and (2) make a complete

evaluation of the metropolitan plan to be submitted by the State Board.

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, plaintiffs respectfully

pray the Court to enter an order authorizing plaintiffs to obtain the

services of an educational expert (and necessary staff) to prepare a

constitutional plan for the Detroit school system with the reasonable

costs of any such prepared plan to be assessed against the defendants.

Plaintiffs further pray the Court to direct defendants to cooperate

with plaintiffs' expert (and his staff), including, but not limited

to, providing work space at the school administration building, and

granting unto him full access to all information concerning all phases

of the school system which he may deem necessary, and supplying him

with any studies and plans and partial plans for desegregation of

the schools which the Board and its staff have already considered,

as well as any other plans they may have.

Respectfully submitted,

L C d d u r t / /

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

NATHANIEL R. JONES

General Counsel, N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

12

OF COUNSEL:

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

PAUL R. DIMOND

ROBERT PRESSMAN

Center for Law and Education

38 Kirkland Street

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

E. WINTHER MCCROOM

3245 Woodburn

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing Response

and Motion has been served upon each of the attorneys for defendants

this 9th day of December, by United States Mail, postage prepaid,

addressed as follows:

George T. Roumell, Jr., Esq.

720 Ford Bldg.

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Robert E. Manley, Esq.

3312 Carew Tower

Cincinnati, Ohio 45202

Alexander B. Ritchie, Esq.

2555 Guardian Bldg.

Detroit, Michigan 48226

William E. Caldwell

George E. Bushnell, Jr., Esq.

2500 Detroit Bank & Trust Bldg.

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Eugene Krasicky, Esq.

Assistant Attorney General

Seven Story Office Bldg.

525 West Ottawa St.

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Theodore Sachs, Esq.

1000 Farmer

Detroit, Michigan 48226

13

a /] w v /^y i w ^ v

AN INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER

JOHN S. KNIGHT, Editor,al Chairman

LEE HILLS, President and Publisher JOHN B. OLSON, V. P. and General Manager

OERICK DANIELS, Executive Editor FRANK ANGELO, Assoc. Exec. Editor MARK ETHRIDGE JR.. Editor

Published every morning by Detroit Free Press, Inc., 321 W. Lafayette, Detroit, Michigan 48231

^ 4 ♦ 4

S-A SATURDAY. NOVEMBER 27, 1971

As We See It

School Board Is Doctein

The Issue on Integration

THE DETROIT Board of Education's

proposal to meet a court order requiring

an acceptable plan for desegregating the

city’s schools are more than an effort to

maintain things as they are. They are

cynical attempts to dodge the issue and

force the courts to take the burden of un

popular decisions.

There is a small amount of desegrega

tion offered in one of the plans, involving

the busing of 39,000 of the city's 285,000

public school pupils.

But mostly the plans are a rehash of the

magnet and middle school programs al

ready in operation which have proved al

most totally ineffective in equalizing

educational opportunity.

Basically, they all involve freedom of

choice, a concept which has perpetuated

school segregation around the nation and

has been rejected repeatedly by the courts.

None of them can possibly be accepted by

U.S. District Judge Steven J. Roth, who

ruled in October that Detroit schools are

segregated and must come up with a plan

to correct the situation.

The school board has admitted that the !

magnet and middle school plans put into l

effect in September have been almost to- j

tally ineffective. A net total of 592 black j

students transferred from majority black

to majority white high schools. A net

total of 511 white students transferred

from majority black to majority white

high schools.

The middle schools, grades five through

eight, is a similar plan to make schools ]

so educationally attractive that white and ■

black parents will send their children to

school together. It has clearly worked out

to be a flight device used by white parents

to get their children into schools where

there was a greater proportion of whites.

In its opposition to the magnet plan, the

Detroit NAACP gets to the real concern

of the black community in a citing of a

1970 court decision:

“The central proposition of the middle

class majority thesis is that the value of

a school depends on the characteristics of

a majority of its students, and superiority

is related to whiteness . . .

"The inventors of this theory grossly !

misapprehend the philosophical basis for

desegregation. School segregation is for-

' bidden -simply because its perpetuation is

a living insult to the black children and

immeasurably taints the education they

receive.”

i Judge Roth’s hint that he might consider

cross-district busing is new and controver

sial. But in his consideration of the situa-

• tion within the city limits he is obligated

to enforce a clear set of rules.

The Board of Education is not even

close to meeting the requirements of the i

* law of the land. The longer its members I

resist that, the more expensive and painful J

it is going to be to pick up the pieces later. J

LYNCHBURG DIVISION

CECELIA JACRSON, ct el

V. CIVIL ACTION

NO.____

THE SCHOOL EOARD OF THE CITY OF :

LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA, efc al :

O R D E R

For th© reasons stated In the memorandum of tha Court thia

day filed, it is ADJUDGED find ORDERED:

That plaintiffs be, and they hereby are, authorised to

prepare such plan for the operation of the public schools of the City

of Lynchburg for the grados below Grade 7 as they docs appropriate

and consistent with constitutional requirements.

considered by the Court as assessable costs against the defendant, and

defendants are herewith granted leave to file within threa days from

this date any argument and exception they wish to make to the Ccurc’e

ruling in this regard, to the end that <his Court my, if doamad proper,

vacate this portion of its order.

3. The defendants be, and they era hereby, directed to cooper**

ate with any consultant retained by plaintiffs in connection with their

proposed plan, including but not limited to providing space for him at

the headquarters of the Superintendent of Schools, and granting unto him

ten which he may deem necessary.

4. Plaintiffs are directed to file within seven days a state**

ment concerning the anticipated time any such study will require.

l*et the Clork send copies of this order to all counsel of record.

2* The reasonable costs of any cuch prepared plan will b®

full access to all information concerning all phases of the school sys

United States District Judge

April 7 if 1970

LYdCiLTIAG Dlv'ICXOr?

CYCTLIA JACuCOII, c t fll :

«

' ** 1 CT7IL ACTION

m s ecitool Ea\rj> of roj city of j — — —

LYKCHLUZIC, VmCIULT, c t a l j

I-rCI'OAATOTH

Xfeo defendants heroin hsva filed with cha Ccort en eic&mcta

propo^l to thair esandal p3.cn in regard to tha dsKssrcgntica of the

Lynchburg schcol systaa. Plaint if fa have filed to c— epeion to certain

portions of tha eugsasted proposal having primarily to do with tha epara*

tion of ths cchoolc carving gredea 7 through 12. They hova, however,

filed exceptions to tha defendants* proposed plan having to do with tha

•Mifpmeat of students below grade 7.

Tha lntua imadlotoly ponding bolero tha Court ta plaintiffs*

■wttoo that tha Court direct tha dafonianta to devita and eutalt a

thar plan for organising and conducting onroltaant la tha . 1 ^ . . ^,

Khoola. or, ta an alternate tharoto, that they, tha plaintiffs, ha

aueheriaad to prepare, at tba eapanaa of the dafondentc. a plan la rafar-

• « . to th. elemontary cchoat. which would provide for tha csotguMut of

.pprozlrataly tha cent parcentcgo of black condense end appraaiaataly tha

**"* p°rcaa“ S« of "Mto atudento ca represented by tha'school papulatloa,

to each of tha clcaantery achoola. In acaooca, they Cnolra to propara a

Plan which would aacura a achool population of epprenisotoly 65 to 75X

’*!'* a“I 25-33* atudonta la aach of tha achoola.

Tha dofoodnnte have reproeonted ta the Ccart, both In tholr

Ptapa^d plan and through ehalr counMlf that In davtetng th. plan aub-

altted they gave conaidcration ta cany factcro Including toning, pairing.

v < th'V havo represented further taut they hew. been

wftble( to develop a ay plea which they consider appropriate to sufcaic

to tLi Court a5 ca cltcmstiva to the plea which they have submitted.

Rsfcrulcss of the coed faith of the cchool authorities, the

fK3 t̂ y tot in any tenner cercuro u failure to afford each end every

ctwdsnt, regardless of iacc, their constitutional ri&hts. See v.

Tr** ?>'■'■£ County, 391 U.S. 430 (126o).

Tna Court 1ms found that the dafondanta* in opita of thoir

pood filth efforts, have been unable to develop a plea which will, os

to the aloaoctary cchoolo* result in ft cchcol cyetca vicltcuv & va*.t».

school1 cad ft ‘Negro echcal*, but juct ecUoolo." New heat, ruarn. It

eey be, of course, that no ouch plan can ba daviccd. This Court, hew-

ever, ift net yet reedy to agree that the task is irrpoteiblo.

In view cf the defendant a’ seed faith representations, it dcaa

r>*r» cppoftT that any ucofal purpose would bo carved in oixccti&c ®t thi#

tiao that they eubtiit an additional £las, at least until they have had

the t&smfit of the views cop re a red in the plan vhich tho Court to S©in3

# to porsdLt tho plaintiffs to file.

Tho defendant# in their proposed plan ca to tho olecsatcry

cchoolo *aftirp little rofarsneo to tho traueporting of such students except

to cvggect that ’'because of tho wldo dieparcrvl of eleractary cchoolo in

ell a?&aa of tho city, tha ccbsol board has never eperated any typo of

school transportation eye ten and has no porscvnsl, fee ill tic a or etfuip**

cent to <lo co,M and further, o mforcoco is sscco to tho board having

determined that “tho aeolsrsxmt of pupils at tt*o olesentary crada level

to schools outo ice of tbsir gccaml raoidccoo arcs which ail cush pupils

#ra in end could feasibly bo «o eastcoed, cons plan of gcc-'yrnphis

would havo to bo forssuletnd, corbiaad with tha pairing ©f certain c-ohoolft

whom feaoilila , end with tho right of majority transfer - -

’2‘

o o

sV

u

I t i s a p p a ren t th a t under th e p rep a red p la n ac c u b u ittc d

by th e d e fa n ia n to , c e r t a i n o f th e c le fro n ta ry sch o o ls would )xs r e a d i ly

I d e n t i f i a b le as ’'w h ite” cchoolo and c e r t a in o f th e n would be r e a d i ly

i d e n t i f i a b le as ’'b la c k ” s c h o o ls . I t has a lre a d y been j u d i c i a l l y d e t e r

mined th a t eicgrcgaticm o f w h ite and c o lo re d c h i ld r e n In p u b lic s c h o o ls

has A d a tr irv s n tn l ©f f a c t upon th o c o lo re d c h i ld r e n . See Brewa v . Board

of Edgestton. 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

All .parties cast recognize that drawing school zon a lines, or

utilising freedea of choica, or pairing, or clustering, or any other

technique,. la not cu and la Itself any cars than busing is.

Vbat tha Court Kust be satisfied of la that It receives all

poaslbla &ud faaslblo plans toward tho ultixeate geel.

Obviously, practical aspects nact fca considered. While tha

high cost of daxegregating cchoolo, if cash vara tho situation, would ^

hi a valid legal ergussent against desegregation, eoa Griffin v.

County School Board of Prince Edward County. 377 U.S. 218 (1964); U.8.

v* -^221 District #151 of Cork County. 111.. 404 P. 2d 1125 (7th Cir.

1968) , eeca recsonahlo degree of practicality cast ba considered. Ca-

«joestii3anbly, oca trcssmdcuoly large cchaol for the uca of ail olerantary

pwpUa la tha Lynchburg school -syctesa would result ia there tains no

"bUck* or "v^ite” schools, hut one trould hardly anticipate that cay

arranstecont wsxild bo constitutionally dssaendsd. Ubore pupils reside

*a«t act ncccacarlly control where they are cssigend to cchcols if coco

«har cpprcach ia necessary la order to eliminate racial segregation.

*** ~ ~ £ 3 F ^ 3 l *>-ys y. gonrar, 303 P. £cp?. 2-39 (1969) ;

Butoycr County Forth Carr-llsa P-nnrfjt of (E.D. 1J.C.

Ju ly U# l5 ^ * clAO S>y-n V. Chftr3otto-?':nklrahorg E rrai o f K-Veatica,

^ ̂U.D, n.C. Uov, 7, 1939). Whom rcaidiutloi eogrwgztics; emicta

J-tcctly osvioua that the neighborhood ochsol coaeept if accepted

**** ce a practical natter, would resale in die calnleiolcg of the

r,c.f m co f.?c f3 the r-V. "V;?? o- ctd: .*3 .d c ' "vt-.". .«

Indtcsl, the Cedurt Is catisfie2 eh si th?.rcs r:r-v irc'-fja uat-sU

Jjsva ca yot cos bswa cforjsnscd that raise ha c^cs-T-nv^. to th is e l l

t©$ vssdr<5 prcblca. Considsratlcctfj of Ccyyyrc;vhy tt-y to e £-stew

to to coasi&ared; tra ffic patterns; both blighted cocoa, £* cny, ecu

fif fluent croc© end their effect, if any, vr.ca the chile ran ro^uored

to attend Cwtools In any cuch crcao. Un^cubccdly the fee tore to to

cc-ssidazed ere, aa previously etc ted, cony ecu d iverts.

Tho Court is net prepared to cud dees vest c ooi—2 feet the

constituCioaal requirements for tho operation of public tchoolo

require tho assignment of eppxcirimato ly tha csoa parccstcga of “ otUCt-**

students end cpprcjdLoataly tha coca parcentcca of 'Hdiito*1 otto, ante ca

represented by tha school pope le t ion, in ouch of tea c- i cccu tc ry cchcolo.

Any each proposal, however, is unc^ucetioua11 y v ice Is cud i t vrcsiid is ^

feet elim inate ,rb-l£«k" and/or "white" schools.

Are now ponding in tho cypellets courts license in

echcol cults the determination of which cay v e i l ho blueing upon th is

Cou r t and w i l l , i f enunciated by e ith e r tho United States Court of

Appeals fo r tha Fourth C irc u it or the United States Cuprersa Court bo

binding. Kowovar, tho constitutional right3 of all stwi-uiE ©f tho

Lynchburg ochcol eyetcm cast not he withhold tha Court cimply ©a

tha basis of awaiting *ppol?.ete rulingo. If, unhappily, no ouch rulings

sro available by the time tha Court secures all of tho information that

it hopes to secure, a ruling will bo forthcoming.

In the interim, it is entirely appropriate that on order be

entered that the plaintiffo be authorised to prepare a cugyostcd plan

for tho operation of tho public echoolfi of tha City of Lynchburg for

the grades below Grade 7 aa ehay deem appropriate and consiotont with

constitutional requirement);. They are reminded, however, of tho Court's

prior statements in this ojiaoraadua that it be considered

-4

iu cclcticnslift? to all rector c~.l cot* r.e c;

cotlon, ccloly o plea which eculd rigidly r,ri

oil ctuemsta os tu vnna, although* of ccurcs*

ercii appropriate ratiots-Tithin too dojrcsa of

C».S.tut*oiinx rocpiice~3at5 would ba desirable.

Toa Court will withhold any ruling

f-— t!r.oj t:.sir

sly a particular ratio

the fitto.icnesnt of 007

practicalities and eta-

on the Lalccea of dafan-

doato1 proposed p ita , c l though the Court dccisa i t epprepriato to ie d i-

caCo* 6c^ dcoa co iuuicata, that the plea for cha Optratica of gredoa

Sbova Credo 7 appcarc to coaforn to ccmotitut focal rsSquirossnto.

Aa appropriate order w i l l bo entered in accord with th is

Bjeaaaraadum.

t' ” * V tK.•/s/ WOSSR? h.

United States District Judjta

April l 1 # 1970.

1