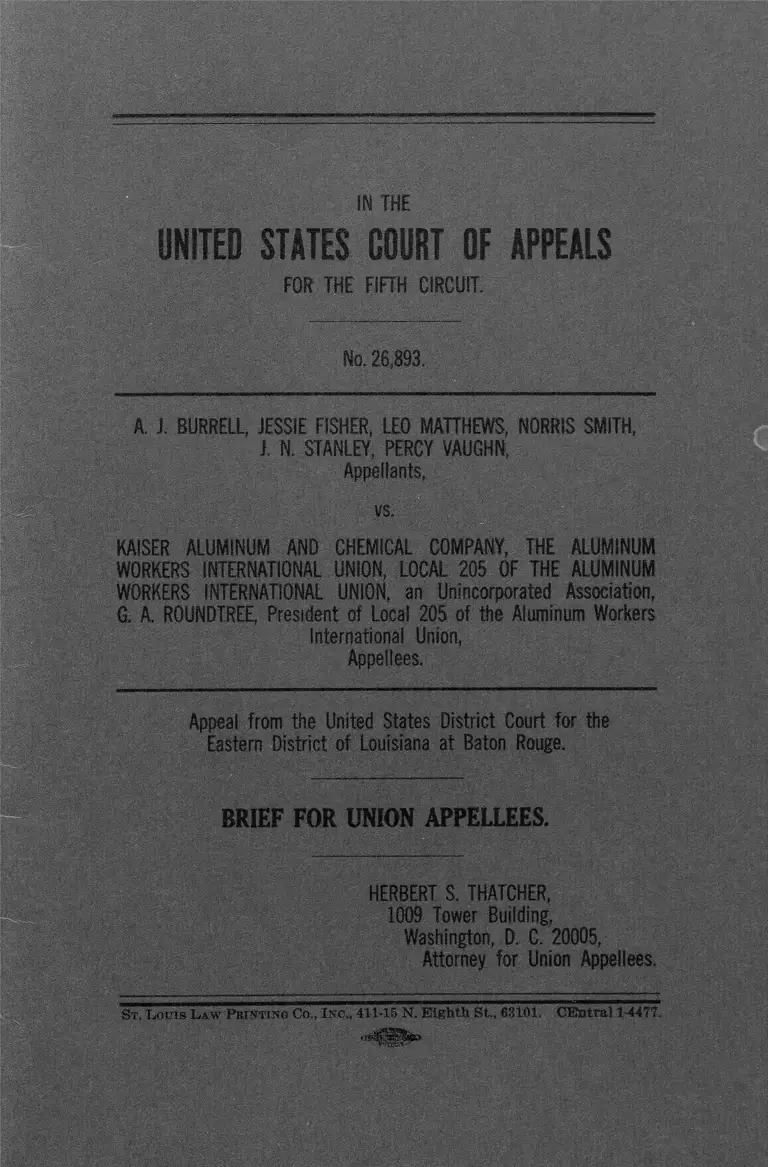

Burrell v Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Company Brief for Union Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

32 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Burrell v Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Company Brief for Union Appellees, 1968. 934b0f25-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5bd98a42-9010-4909-ad15-99eb3ec20e88/burrell-v-kaiser-aluminum-and-chemical-company-brief-for-union-appellees. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR TH E FIFTH CIRCUIT.

IN THE

No. 26,893,

A, J. B URRELL, JESSIE FISHER, LEO MATTHEWS, NORRIS SMITH,

J. N. STANLEY, PERCY VAUGHN,

Appellants,

vs.

KAISER ALUMINUM AND CHEMICAL COMPANY, THE ALUMINUM

WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION, LOCAL 205 O F TH E ALUMINUM

WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION, an Unincorporated Association,

G. A. ROUNDTREE, President of Local 205 of the Aluminum Workers

International Union,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana at Baton Rouge.

BRIEF FOR UNION APPELLEES.

HERBERT S. THATCHER,

1009 Tower Building,

Washington, D. C. 20005,

Attorney for Union Appellees.

St, L ou is L a w Pr in tin g Co ., I n c ., 411-15 N. Eighth St., 63101. CEntral 14477.

INDEX.

Page

Issues ..................................................................................... 1

Statement of Case ............................................................... 2

Argument ............................................................................. 5

I. Under the circumstances of this case and in par

ticular because appellants had entered into the

conciliation agreement, notification by the Com

mission that it has been unable to obtain com

pliance is a jurisdictional prerequisite to the

institution of a civil action under Section 706

(e) of the A c t ............................................................. 5

II. Appellants are required to exhaust the adminis

trative remedies which they themselves have

established and made exclusive .......................... 11

Conclusion ........................................................................... 15

Attachment A—Dissenting opinion ..................................A -l

Table of Cases.

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railroad, 265 F. Supp.

56 (N. D. Ala. 1967)....................................................7,8,13

Drake Bakeries, Inc. v. Local 50 Bakery Workers, 370

U. S. 254 ........................................................................... 13

Glover v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railroad, . . . F.

2d ....................................................................................... 13

Johnson v. Seaboard Railroad Co., . . . F. 2 d ............... 7, 8

Local 721, United Packing House Workers v. Need

ham Packing, 376 U. S. 247 ......................................... 13

11

Mickel v. S. Carolina State Employment Service, 377

F. 2d 239 ........................................................................... 7

Myers v. Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation, 303

U. S. 41 ..................................................................... 12

Republic Steel Corp. v. Maddox, 379 U. S. 650 ............ 13

Russell-Newman Manufacturing Co. v. NLRB, . . . F.

2d .. ., 64 LRRM 4927 ................................................... 8

Stebbins v. Nationwide Mutual Insurance Co., 382 F.

2d 267 ............................................................................... 7

Statutes.

29 U. S. C. 2151 et seq........................................................ 13

42 U. S. C. 2000 e, et seq.:

Sec. 705 (g) (4) ............................................................. 6

Sec. 706 (a) ..................................................................... 6,7

Sec. 706 (e) .............................................................. 5,6,7,11

Sec. 713 (b) ..................................................................... 10

Miscellaneous.

3 Davis Administrative L a w ........................................... 12

Jaffee Judicial Control of Administrative A ction ........ 12

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT.

No. 26,893.

A. J. BURRELL, JESSIE FISHER, LEO MATTHEWS, NORRIS SMITH,

j. N. STANLEY, PERCY VAUGHN,

Appellants,

vs.

KAISER ALUMINUM AND CHEMICAL COMPANY, THE ALUMINUM

WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION, LOCAL 205 OF TH E ALUMINUM

WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION, an Unincorporated Association,

G. A. ROUNDTREE, President of Local 205 of the Aluminum Workers

International Union,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana at Baton Rouge.

BRIEF FOR UNION APPELLEES.

ISSUES.

I. Under tie circumstances of this case is a finding by

the Commission that it has been unable to obtain volun

tary compliance with the Act a jurisdictional prerequisite

to the institution of court action?

II. Apart from the statute, are parties charging a viola

tion of the Act required to exhaust administrative remedy

before the Commission which they themselves have agreed

to before institution of court action?

— 2 —

STATEMENT OF CASE.

Appellants’ Statement of the Case refers only inci

dentally to the fact that the Equal Employment Oppor

tunities Commission (Commission) has fully explored the

charges which are the subject matter of appellants’ com

plaint in the District Court and by use of its powers of

persuasion and conciliation has induced the parties to

enter into a conciliation agreement intended to resolve all

the issues of discrimination between the parties. The con

ciliation agreement (17a) was the result of strenuous ef

forts by the charged employer, the charged union (appel

lees here), and the Commission acting on behalf of the

charging parties, to resolve the original charges and to

settle all differences between the parties. The agreement

was expressly approved by the Commission. Under the

agreement, the parties made the Commission the sole arbi

trator of questions arising under the agreement and com

pliance therewith, and in addition the charging parties

agreed not to bring civil suit but instead to rely upon the

Commission as the arbitrator.

Section 1 of the Agreement reads as follows:

“ 1. The respondents agree that the Commission, on

request of any charging party or on its own motion,

may review compliance with this agreement. As a

part of such review, the Commission may require

written reports concerning compliance, may inspect

the premises, examine witnesses, and examine and

copy documents.”

Section 3 of the Agreement reads as follows:

“ 3. The Charging Party hereby waives, releases

and covenants not to sue any respondent with respect

to any matters which were or might have been al

leged as charges filed with the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, subject to performance by

the respondents of the promises and representations

contained herein. The Commission shall determine

whether the respondents have complied with the terms

of this agreement.” [Emphasis supplied.]

The conciliation agreement undertook to correct the

very complaints of discrimination which are the subject

matter of appellants’ complaint in the District Court. Thus

the agreement required that “ all hiring, promotion prac

tices and other conditions of employment shall be main

tained and conducted in the manner which does not dis

criminate . . . ” (18a); required that all facilities on the

premises of the employer shall be available for the use of

any employee without discrimination (18a); and amended

the collective bargaining agreement to establish a new

nondiscriminatory seniority provision setting up an equi

table pattern of promotion from within. It called for use

of plant wide seniority for promotions into operating de

partments from the utility man classifications. The utility

man classification is the one through which a person moves

into higher paid positions in the department so that this

new arrangement greatly benefited senior Negro employ

ees who had been unable to advance in the past.

Appellants’ complaint in the District Court below

charged discrimination in respect to these same subject

matters and alleged specifically a violation of “ each and

every point in the conciliation agreement” (10a). Thus

the complaint alleged discrimination in promotion and

seniority (7a), job classifications, lay-offs, apprenticeship

training, and use of plant facilities (7a-12a). In substance,

all of the charges and complaints brought before the

court below revolve around the seniority system and its

application—the very matter which the conciliation agree

ment went to great lengths to correct (Bee 19a, 34a and

52a).

— 4 —

When after execution of the agreement a disagreement

arose as to whether violations continued to exist, both the

charging parties (33a) and the company (39a) requested

the Commission to resolve the dispute under the agree

ment. The conciliation agreement was in full effect when

the complaint was filed in the district court. The Com

mission had made no determination respecting compliance

with the conciliation agreement as the parties had required

it to do under Section 3 thereof.

In spite of the existence of the conciliation agreement,

and before the Commission made any determination with

respect to the issues of non-compliance therewith, the

appellants requested the Commission to issue a statutory

notice pursuant to Commission rules under which civil

suit could be brought. Such notice was issued (53a).

The Commission, however, carefully refrained from any

statement that it had been unable to obtain voluntary

compliance with either the Act or the Agreement or

whether the Commission had reasonable cause to believe

appellants’ charges were valid. On the contrary, the

Commission made it clear that it had made no such de

termination. The statutory notice (50a) reads as follows:

“ . . . Although the Commission had not made a

determination as to whether or not there is reasonable

cause to believe your charge is valid, your counsel

the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund Inc.

has demanded, pursuant to Commission’s rules, 20

C. F. R., Section 1601.25 (a), that this statutory

notice issue.”

The bringing of the suit apparently ended all efforts

to resolve the issues of compliance with either the Act

or the Agreement. Although several meetings were con

ducted by the Commission the Union was not invited to

attend these meetings and did not attend.

— a —

ARGUMENT.

I.

Under the Circumstances of This Case and in Particular

Because Appellants Had Entered Into the Conciliation

Agreement, Notification by the Commission That It Has

Been Unable to Obtain Compliance Is a Jurisdictional

Prerequisite to the Institution of a Civil Action Under

Section 706 (e) of the Act.

The judicial requirements of Section 706 (e) are plainly

set forth. Subsection (e) reads:

“ (e) If within thirty days after a charge is filed with

the Commission or within thirty days after expira

tion of any period of reference under subsection (c)

(except that in either case such period may be ex

tended to not more than sixty days upon a deter

mination by the Commission that further efforts to

secure voluntary compliance are warranted), the Com

mission has been unable to obtain voluntary compli

ance with this title, the Commission shall so notify

the person aggrieved and a civil action may within

thirty days thereafter, be brought against the re

spondent named in the charge. . . . ”

Congress has plainly made it the absolute duty to notify

of inability to obtain voluntary compliance mandatory—the

Commission “ shall so notify.” Admittedly there has

been no such notification in the present case, nor even

of just cause. Failure to make such a finding must pre

clude court action. Only an orderly and efficient appli

cation of the enforcement provisions of the Act can

achieve its purposes. The use of conciliation and volun

tary compliance is emphasized throughout the Act as the

principal means relied on by Congress for enforcement.

6

Section 705 (g) (4) expressly confers full conciliation

powers upon the Commission. Section 705 (g) (5) re

quires the Commission to furnish whatever technical as

sistance might be necessary to insure compliance. Most

importantly Section 706 (a) makes it mandatory upon

the Commission to endeavor to eliminate violations by

“ informal methods” . The fact that criminal penalties

are imposed on agents of the Commission for improper

disclosures under Section 706 (a) emphasizes the weight

which Congress has attached to informal conciliation.

Finally, 706 (e) in addition to the requirement of notifi

cation of inability to obtain compliance, speaks in terms

of “ further efforts” , connoting continued conciliation by

the Commission and even authorizes the Commission to

request a stay of court proceedings pending a “ termina

tion” of its efforts. It is difficult to conceive of plainer

language of a Congressional command to exhaust attempts

at voluntary compliance through conciliation. Because

the Act did not bestow enforcement power upon the

Commission, Congress made it quite evident that the

long-term goal of the Act—the elimination of discrimina

tion—to to be achieved by conciliation, persuasion and

voluntary compliance. Reading the Act as a whole, as

it must be, it is entirely clear that full, not partial or

desultory efforts to obtain compliance is enjoined on the

Commission. The courts can be called upon only as a last

resort.

Here the Commission did fully exercise its functions

of conciliation and did in fact prevail upon the employer

and the union involved to enter into a written agreement

which all parties and the Commission regarded as dis

positive of the original charges. Moreover, the parties to

the Agreement bound themselves to refrain from court

action but, instead to look to the Commission for any

dispute concerning violation of the Act under the agree

ment. The matters at issue under appellants’ complaint

7

in the court below have been submitted to the Commis

sion for its interpretation and resolution pursuant to the

conciliation agreement.

Although fully familiar with the issue, the Commission

has not notified of any inability to obtain voluntary com

pliance as required under Section 706 ( e ) ; indeed, it has

not even determined that there is reasonable cause to be

lieve that any violation of the Act exists as required

under Section 706 (a) thereof.

The courts that have considered the question of the

necessity of the Commission’s finding of reasonable cause

and inability to obtain compliance as a judicial prerequi

site to institution of court proceedings are in disagree

ment. The arguments and reasoning which require such

a finding as a prerequisite to court jurisdiction are before

this Court in the Dent case,1 as is the lengthy decision of

Chief Judge Lynne therein. There is no need to repeat

them here and appellees respectfully refer this Court to

the Lynne opinion as well as the exhaustive discussion of

the issues by Judge Boreman dissenting in the decision

of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Johnson v.

Seaboard Railroad Co., . . . F. 2d . . . , October 20, 1968,

particularly for the discussion of the legislative history

contained in Judge Boreman’s dissent, (For the con

venience of the Court a copy of this dissent is attached

hereto as attachment “ A ” .)

Those opinions make clear the intent of Congress to

require the Commission to exhaust completely all efforts

at conciliation before civil litigation can commence.

1 Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railroad, 265 F. Supp. 56

(N. D. Ala. 1967), awaiting decision in this Court (No. 24,810).

See also Stebbins v. Nationwide Mutual Insurance Co., 382 F.

2d 267; Mickel v. S. Carolina State Employment Service, 377

F. 2d 239.

While it is true that the majority of the Fourth Circuit

in the Johnson case has held that the requirement of

notice of exhaustion of conciliation in the Act means only

that the Commission he given an opportunity to persuade

before court action can be brought, that case does not

involve the situation here where the Commission has not

only attempted to persuade but has succeeded in per

suading to the extent of inducing the parties to enter

into a conciliation agreement which purports to eliminate

all alleged grievances and to which all the parties sub

scribed. Under such circumstances the need for a Com

mission finding prior to litigation either that there is

cause to believe a violation exists or that it has been un

able to obtain voluntary compliance becomes particularly

necessary because the Commission has already performed

its conciliation function and the only question at issue is

whether the results of its efforts—the conciliation agree

ment—had been complied with, and the parties have

designated the Commission as only the arbitrator of any

differences under the settlement. Thus, the reasoning and

policy considerations set forth in Dent, supra, and by

Judge Boreman are doubly compelling. Surely the doors

of the courts should not be opened and the courts sub

jected to the burden of resolving issues when the Com

mission has already taken them fully in hand.

In the present case the Commission has not even pleaded

an overworked case load as the reason for failing to per

form the functions which the parties have delegated to

it. Surely by simply saying nothing while at the same

time pursuant to its own regulations permitting appel

lants to bring suit the Commission can not bypass the

clear provisions of the statute. “ Administratively con

venience cannot override” the requirement of statutory

notice. See Russell-Newman Manufacturing Co. v. NLRB,

371 F. 2d 980, 64 LRRM 4927. The remarks of Judge

Boreman in discussing the necessity of the Commission

— 8 —

performing the duty imposed on it by Congress and point

ing out that even a plea of heavy case load is not sufficient

to eliminate that duty are particularly cogent in the cir

cumstances of this case. He said:

“ In each of these cases the Commission admittedly

made no effort whatsoever to eliminate the alleged

unlawful employment practice by the informal meth

ods prescribed by statute. The only reason assigned

by the Commission for such failure was its ‘ heavy

work load.’ By this simple expedient the Commis

sion sought to bypass the clear provisions of the stat

ute, to render them meaningless and thereby open the

floodgates to the judiciary when the obvious intent

of the lawmakers, as indicated by the language of the

statute and the legislative history, was to place the

primary burden on the Commission, to protect em

ployers and the other persons subject to the provi

sions of the statute from subjection to the burden of

frivolous claims and demands, and to protect the

courts from the anticipated deluge of civil actions to

enforce the newly-created statutory civil rights.

“ If inability to undertake conciliatory procedures

be attributable solely to a ‘ heavy case load,’ as as

serted by the Commission, this would not be the first

instance where statutes could not be followed or en

forced because of lack of necessary implementation.

If sufficient funds were not appropriated to permit the

Commission to function as intended this situation can

and should be corrected, but this is a problem which

cannot be solved by the courts. Claims of resulting

unfairness to allegedly aggrieved persons have been

made in this and other courts if conciliation effort,

though unsuccessful, is held to be a prerequisite to

resort to the courts. It is clear that Congress in

tended to protect aggrieved persons against viola

— 9 —-

— l o

tions of their civil rights but it is clear also that

Congress did not lose sight of the unfairness which

would result to parties against whom charges are

filed if they could be brought into court without the

conciliation step.”

A final factor which demonstrates the importance which

Congress has attached to any agreement authorized by

the Commission is provided by the provisions of Section

713 (b) of the Act, which expressly provides for a defense

where the accused can plead or prove an act of omission

in good faith reliance “ on any written interpretation or

opinion of the Commission.” There has been such a

written interpretation in the concluded conciliation agree

ment ascribed to by the Commission. The Commission has

never withdrawn its imprimatur from the conciliation

agreement nor has its original sanction which has been

relied upon by the parties been found invalid either by

the Commission or any judicial authority. In making the

agreement the parties relied upon the expertise of the

Commission and that expertise informed them that the

charges of violation had been cured. Now this same gov

ernmental agency when asked to explain a creature of its

own making apparently avoids its obligation. This agree

ment was not entered into without some sacrifice by the

unions, but was a good faith effort by them to rectify any

alleged discriminatory conduct in employment opportuni

ties. The conciliation agreement was the Commission’s an

swer as to how these alleged acts could be corrected. It

was evident that everyone would not be satisfied with the

implementation of the new system required by the concili

ation agreement but it was hoped by all parties that the

Commission would attempt to conciliate or arbitrate any

problems arising thereafter. Yet when a problem arose and

the parties looked to the Commission for guidance and

assistance that assistance has not been forthcoming. It

is submitted that the courts are obliged to decline to

— 11 —

assert jurisdiction in this case until all administrative

remedies are exhausted, particularly in view of the fact

that prior conciliation efforts have met with success as

evidenced by the conciliation agreement.

In summary then, the existence of a conciliation agree

ment purporting to settle the very violations which are

the subject of attempted civil litigation differentiates this

case from all others where the issues of the necessity of

a finding of reasonable cause as a jurisdictional prerequi

site has been decided or raised. Where, as here, the Com

mission has already exercised its conciliation powers to

produce an end result of compliance by conciliation agree

ment and the parties have designated the Commission as

sole arbitrator of any differences concerning the applica

tion or interpretation of the terms of the conciliation

agreement, the notice requirements of 706 (e) must be

strictly observed, and the charging parties must be noti

fied by the Commission that it cannot remedy their com

plaints before the courts can be drawn into the contro

versy.

II.

Appellants Are Required to Exhaust the Administra

tive Remedies Which They Themselves Have Established

and Made Exclusive.

Statutory considerations aside, it would appear that the

common law principle of denying access to the courts

until administrative remedies are exhausted is applicable

in this case. This principle is particularly relevant here

in view of the fact that appellants have already invoked

the Commission’s conciliation powers to the extent of

obtaining, through the Commission, an agreement de

signed to settle their complaints, and in that agreement

have expressly agreed not to litigate their complaints in

the courts but instead give the Commission jurisdiction

— 12

and authority to resolve any dispute concerning appli

cation of the agreement disposing of their charges and

the Commission’s jurisdiction to this end has been in

voked. Unless and until the Commission certifies that

the agreement has not been complied with and that

appellees continue to violate the Act, appellants should be

required to pursue the remedy they themselves have

selected.

The general rule, of course, is that the court will not

step in until available administrative relief has been ex

hausted. Myers v. Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation,

303 U. S. 41. In determining whether or not to apply the

rule in any given case the courts balance the variables.

See 3 Davis Administrative Law, Para. 20.03, and Jaffee

Judicial Control of Administrative Action, 436, 432 (1965).

Here the parties, pursuant to their agreement, have ex

pressly designated the Commission as the forum to settle

differences under the agreement to the exclusion of the

courts. That body, not the courts, has the expertise—an

expertise heightened by its participation in the settlement.

Continuation of the proceedings before it should not be

bypassed or abandoned to allow an excursion into the fed

eral courts with accompanying prolonged evidentiary hear

ings. For the courts to intervene when the conciliation ef

forts of the Commission have reached settlement stage can

lead only to a breakdown in the administration of the stat

ute and a contravention of its basic purpose to remedy

violations by conciliation through the machinery of the

Commission. To render the Commission’s considerable ef

forts a nullity after settlement has been reached would

dissuade parties from resorting to the Commission in the

future. This case is not ripe for judicial determination

until the Commission has acted one way or the other upon

the pending dispute over application of the conciliation

agreement. I f ever the rule of exhaustion of administrative

remedies is applicable, it is applicable here.

— 13

This Circuit in the case of Glover v. St. Louis San Fran

cisco Railroad Company, 386 F. 2d 452, has affirmed the

rule in a case similar to the present. There an issue of

racial discrimination was also involved and court relief

was sought before the complainant had utilized remedies

available to them under the Railway Labor Act and under

their collective bargaining agreement. This Court held

that these administrative remedies must first be exhausted

and cannot be bypassed by court action.

A persuasive analogy exists in Republic Steel Corp. v.

Maddox, 379 U. S. 650. There the U. S. Supreme Court

held that where employees covered by a collective bargain

ing agreement charge a breach of that agreement adversely

affecting them and the agreement contains a clause pro

viding for settlement of their complaint through the griev

ance and arbitration processes, this remedy must first be

exhausted before the remedy which Congress has given

under Section 301 of the Taft-Hartley Act in the federal

courts can be invoked. See also Drake Bakeries, Inc. v.

Local 50 Bakery Workers, 370 U. S. 254; Local 721, United

Packing House Workers v. Needham Packing, 376 U. S.

247.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act must be read in the

context in which it was written and should be considered

in conjunction and in the light of other acts of Congress

which regulate labor-management relations such as the

Taft-Hartley Act, at least by analogy. Although the con

ciliation agreement in the present case had been made

part of the existing collective bargaining agreement be

tween the union and the company and that contract con

tains grievances and arbitration machinery which could be

resorted to by appellants, it is not necessarily urged that

appellants are obliged to exhaust that remedy under the

principle of the Maddox case, supra. See Opinion of Judge

Lynne in Dent v. St. Louis San Francisco Railroad, supra,

in which he held that remedies under a collective bargain

14 —

ing agreement need not be first pursued by persons al

leging a violation of tbe Civil Eights Act. This case is dif

ferent, and at tbe very least the remedies the parties have

agreed to under a Commission sponsored conciliation

agreement must be exhausted. While it may not be con

sistent with the policies of the Civil Eights Act to require

complaining parties to pursue remedies under applicable

collective agreements when violations of the Act are

charged before resorting to court, it would be entirely con

sistent with the purposes of the Act to require complain

ing parties to exhaust remedies before the Commission

which they themselves have established. In so doing, the

Act would not be bypassed but rather the concept under

lying the entire Act—resolution of alleged violations by

the Commission through the conciliation processes—would

be furthered. The Congress could not have intended and

the courts should not countenance branding conciliation

efforts and the execution of conciliation agreements as im

material or superfluous. If the efforts of the Commission

are to mean anything then the terms of the conciliation

agreement reached under the auspices of and approval by

Commission must establish the rule between the parties

thereto.

Here the Commission has been requested to review the

compliance with the conciliation agreement and to apply

the agreement according to its terms. For the courts to

intervene at this stage absent a pronouncement by the

Commission that it is unable to make a determination

would nullify and disregard the accomplishment of the

A ct’s principal purpose— settlement by voluntary means.

If the Commission has been diliatory in completing its

function under the settlement agreement, that is not the

fault of the union or the company, and the Commission

should not be permitted to abandon its extended efforts to

this juncture without substantial showing of reason there

for.

— 15

CONCLUSION.

For the reasons set forth above it is respectfully sub

mitted that the judgment below should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

HERBERT S. THATCHER,

1009 Tower Building,

Washington, D. C. 20005,

Attorney for Union Appellees.

APPENDIX.

A -l —

ATTACHMENT A.

Boreman, Circuit Judge, dissenting:

With due respect for the opinions of my brothers I find

myself in disagreement with them in these cases. Accord

ingly, I record my views in this separate statement.

The statutes here principally involved (Title VII, § 706,

42 U. S. C., § 2000e-5, subsections (a) and (e), are set out

in footnotes numbered 4 and 5 of the majority opinion.

There is no need to reproduce them here. The majority

view is that the “ statute, on its face, does not establish

an attempt by the Commission to achieve voluntary com

pliance as a jurisdictional prerequiste” to the bringing

of a civil action by a person allegedly aggrieved.

In each of these cases the Commission admittedly made

no effort whatsoever to eliminate the alleged unlawful em

ployment practice by the informal methods prescribed by

statute. The only reason assigned by the Commission for

such failure was its “ heavy work load.” By this simple

expedient the Commission sought to bypass the clear pro

visions of the statute, to render them meaningless and

thereby open the floodgates to the judiciary when the ob

vious intent of the lawmakers, as indicated by the lan

guage of the statute and the legislative history, was to

place the primary burden on the Commission, to protect

employers and other persons subject to the provisions of

the statute from subjection to the burden of frivolous

claims and demands, and to protect the courts from the

anticipated deluge of civil actions to enforce the newly-

created statutory civil rights.

It is elementary that the fundamental purpose of con

ciliation is to avoid litigation. In these cases appellants

— A-2 —

(hereafter plaintiffs) would have the court adopt the un

natural view that conciliation may follow litigation at the

election of a litigant. Undeniably, if conciliation is to

follow litigation then its whole purpose is defeated and

the effort of Congress to require it prior to litigation is

reduced to an idle gesture. This point is clearly mani

fested in the wording of the statute and it was recited

again and again in the legislative history as will be later

noted. Plaintiffs seek to persuade the court to read and

construe subsection (e) standing alone and not in con

junction with subsection (a). That argument entirely

overlooks subsection (a) as well as other pertinent lan-

gauge in subsection (e). The language of subsection (a) of

section 706 is clear that if the Commission finds reasonable

cause to believe the charge is true it shall endeavor to

eliminate the practice by “ informal methods.” The lan

guage of subsection (e) of section 706 further establishes,

as the court below stated, that after this effort is made by

the Commission it then becomes its duty to report its fail

ure to the aggrieved party who may then institute action

in court. Subsection (e) gives the Commission power to

extend conciliation beyond thirty days if further efforts

to secure voluntary compliance are warranted. The words

“ further efforts” clearly connote that Congress contem

plated that initial efforts to conciliate had already gone

before. Furthermore, after an action has been commenced

in the district court, subsection (e) authorizes the Com

mission to request the court to stay proceedings pending

the termination of the efforts of the Commission ‘ ‘ to obtain

voluntary compliance.” This language is further proof

that conciliation efforts must have begun before suit is

filed.

Applying elementary rules of statutory construction,

section 706 must be read as a whole in order to ascertain

its true meaning. Each part or section should be con

strued in connection with every other part or section to

A-3 —-

produce a harmonious whole.19 Reading subsections (a)

and (e) together, I reach the conclusion that conciliation

efforts must precede suit. This conclusion was reached by

Professor Sovern of the Columbia Law School and Legal

Consultant to the NAACP Legal Defense and Education

Fund. As he stated in a treatise on this subject:

“ That the structure of §706, with its linkage of

the individual suit to Commission conciliation, leads

naturally to the conclusion that the complainant can

not sue until the Commission takes the steps specified,

could not have been lost on Congress * * V ’20

In analyzing the language of the statute the court in

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 265 F. Supp.

56, 62 (N. D. Ala. 1967), stated:

“ * * * j f not only speaks of ‘ the termination’ of

conciliation but was likewise explained in Congress as

authorizing a stay pending ‘ further efforts at con

ciliation by the Commission’ [110 Cong. Rec. 15866

(July 2, 1964)], and it therefore is to authorize a stay

for the termination or continuation of conciliation

efforts, not for their initiation.”

In referring to subsection (e) and noting that the Com

mission has up to sixty days to attempt to secure volun

tary compliance the following statement appears in the

Harvard Law Review:

‘ ‘ Only after this effort has failed may the aggrieved

person bring an action for relief, and even then the

court may, upon request, stay proceedings for up to

19 2 Sutherland, Statutory Construction, § 4703; Mastro Plas

ties Corp. v. National Labor Relations Board, 350 U. S. 270, 285

(1956); National Labor Relations Board v. Lion Oil Co., 352

U. S. 282, 288 (1957).

20 Sovern, Legal Restraints on Racial Discrimination in Em

ployment, 82 (1966).

A -4 —

60 additional days pending # * * the further efforts

of the Commission to obtain compliance.” (Emphasis

added.)21

The passage of this civil rights legislation and the stat

utory provisions pertinent here was accomplished only

after much debate, after amendments were proposed and

material changes made which differed from the original

proposals. “ Seldom has similar legislation been debated

with greater consciousness of the need for ‘ legislative his

tory’ or with greater care in the making thereof, to guide

the courts in interpreting and applying the law.” 22

In both the House and Senate, it was explained that a

civil action could not be brought without efforts to achieve

voluntary compliance by conciliation. The House Labor

Committee Report explained that “ maximum efforts be

concentrated on informal and voluntary methods of elim

inating unlawful employment practices before commencing

formal procedures.” Representative Lindsay, then a mem

ber of the House Judiciary Committee, explained that

“ the procedures are carefully spelled out * * * Those pro

cedures are designed to give due protection to everyone.

They command that there first be voluntary procedures.” 23

He added that “ unless this voluntary procedure is com

plied with, nothing further can happen.” 24

On at least two occasions Congress thoroughly con

sidered and then rejected proposals that litigants be per

mitted to proceed with court action before conciliation

21 The Civil Eights Act of 1964, 78 Harv. L. Rev. 684, 693

(1965).

22 Yaas, Title V II; Legislative History, 7 Boston College L.

Rev. 431, 444 (1966).

23 110 Cong. Rec. 1638, 2565 (Feb. 1, 8, 1964).

24 110 Cong. Rec. 2565 (Feb. 8, 1964).

-— A-5 —-

was attemped. Thus, the original bill expressly provided

that a civil action could be brought “ in advance” of con

ciliation efforts “ if circumstances warrant,” hut these

clauses were eliminated “ to make certain” that there be

resort “ to conciliatory efforts” before court action.25

The bill was passed by the House as amended and the

amendment, eliminating the “ in advance” clause, was ex

plained by Representative O ’Hara:

“ There were some who believed that perhaps the

language, as it stood, would authorize bringing the

action in court before any attempt had been made to

conciliate. We thought that striking the language

would make it clear that an attempt would have to

be made to conciliate in accordance with the lan

guage * # * before an action could be brought in the

district court.” 26

Further evidence of intent is found in the fact that in

1965 Congress again was urged to enact a law which

would permit litigation “ in advance” of conciliation.27

Again Congress rejected this proposal. It seems to me

perfectly clear that the plaintiffs are here seeking by

court decree to acquire precisely that which legislative

proponents sought and failed to get from the Congress.

The plaintiffs concede in their brief that conciliation

efforts were a prerequisite to a civil action under the bill

as passed by the House. But they argue that the concilia

tion prerequisite was eliminated by the Dirksen compro

25 110 Cong. Rec. 2566, 2576 (Feb. 8, 1964) (Rep. Celler,

Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee).

20 110 Cong. Rec. 2566 (Feb. 8, 1964).

27 House Rep. No. 718 on H. R. 10065, 89th Cong., 1st Sess.,

1965.

— A-6 —

mise in the Senate. To support this argument they point

to the fact that the compromise substituted the “ person

aggrieved” for the Commission as the party authorized

in the original proposal to bring the civil action. This

argument is in “ patent disregard for the fact that the

procedure under the compromise was explained [in the

Senate], just as was the House Bill, as authorizing the

institution of a civil action only after conciliatory efforts

by the Commission.28 As to the conciliation step, it was

explained in the Senate:

“ [W ]e have leaned over backwards in seeking to

protect the possible defendants by means of all the

procedures referred to—those of conciliation, arbitra

tion, and negotiation.” 29

“ If efforts to secure voluntary compliance fail, the

person complaining of discrimination may seek relief

in a federal district court.” 30

Senator Saltonstall explained his support of the pro

posed legislation as follows:

“ [A ]n aggrieved party may initiate action under the

provisions of the bill on a federal level. In such cases,

provision is made for Federal conciliation in an effort

to secure voluntary compliance with the law prior to

court action.

“ The point of view of this section is to permit one

who believes he has a valid complaint to have it

studied by the Commission and settled through con

ciliation if possible. The Court procedure can follow.

“ In Massachusetts, we have had experience with

an arrangement of this sort for 17 years and as I re

28 Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 265 F. Supp. 56,

59-60 (N. D. Ala. 1967).

29 110 Cong. Rec. 14190 (June 17, 1964) (Senator Morse).

30 110 Cong. Rec. 12617 (June 3, 1964) (Senator Muskie).

A-7 —

call, approximately 4,700 unfair practice complaints

have been brought before our Massachusetts Commis

sion Against Discrimination. Only two of them have

been taken to court for adjudication. That procedure

is the basis and theory of this part of the bill and

that is why I support it.” 31 (Emphasis above sup

plied.)

Senator (now Vice President) Humphrey made the fol

lowing statements:

“ Those of us who have worked upon the substi

tute package have sought to simplify the administra

tion of the bill * * * in terms of seeking a solution by

mediation of disputes, rather than forcing every case

before the Commission or into a court of law.

“ We have placed emphasis on voluntary concilia

tion—not coercion.

“ The amendment of our substitute leaves the in

vestigation and conciliation functions of the Commis

sion substantially intact.

“ Section 706 (e) provides for suit by the person

aggrieved after conciliation has failed.” (Emphasis

supplied.)32

The plaintiffs ignore the legislative history relating to

the compromise between the Senate and the House and the

adoption of the legislation in its present form. All of this

history was relied upon by Chief Judge Lynne in the

Dent case,33 and I cannot overlook the fact that this court

heretofore indicated approval of Dent in Mickel v. South

Carolina State Employment Service, 377 F. 2d 239, 242 (4

31 110 Cong. Rec. 12690, 14190 (June 4, 17, 1964).

32 110 Cong. Rec. 13088, 14443, 12722-12723 (June 4, 9, 1964).

33 Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 265 F. Supp. 56

(N. D. Ala. 1967).

— A-8—-

Cir. 1967), in which decision two of the judges in the

instant cases joined. We there stated:

“ The decision in Dent, -supra, * * * painstakingly

discusses the legislative history of this portion of the

Civil Eights Act. The opinion presents overwhelming

authority culled from Congressional committee reports

and the statements of key legislators to support the

conclusion that Congress intended that persons claim

ing discrimination in employment should first exhaust

their remedies within the Commission created for

that purpose. Furthermore, the original bill contained

a clause permitting the bringing of civil actions prior

to seeking conciliation but this provision was elim

inated by a House amendment in order to insure that

conciliatory efforts would be made.”

I again express my approval of the decision in Dent

and its analysis of the legislative history. That decision

was relied upon heavily by the court below. Now, the

plaintiffs incorrectly assert that most of the items of

legislative history relied upon by the district court and

by the court in the Dent case were from the House “ at a

time when the bill still provided for judicial enforcement

only at the suit of the Commission,” a provision in the

bill as originally drafted. It would appear that the

statements from the Senate as hereinabove set forth dem

onstrate that the arguments advanced by plaintiffs are

without merit. It cannot be doubted that the Dirksen

compromise was “ a further softening of the enforcement

provisions of Title V II,” 34 and placed “ greater emphasis

* * * on arbitration and voluntary compliance than there

was in the House bill.” 35 Senator Case, a co-manager of

the bill in the Senate, stated:

34 110 Cong. Rec. 12595 (June 3, 1965) (Senator Clark).

35 110 Cong. Ree. 15876 (July 2, 1964) (Rep. Lindsay).

“ There could he no claim of harassment in as much

as the enforcement procedure has been whittled down

to the minimum.” 36 37

Therefore, it would be illogical to construe the compro

mise as placing less emphasis on voluntary compliance

than did the House bill.

The plaintiff’s argument that the Dirksen compromise

in the Senate was intended to permit suit prior to con

ciliation efforts, thereby reversing the procedure admit

tedly spelled out in the House bill, is illogical in two more

respects. First, the compromise grew out of the need

of the supporters of the hill in the Senate to invoke the

cloture procedure. In order to obtain the required num

ber of votes the House bill had to be softened. “ The

necessity for and difficulties in obtaining the two-thirds

vote for cloture must be borne in mind in any attempt to

understand the amendments to the bill adopted in the

Senate and particularly the amendments to Title VII.87

Second, if it had been the intent of the Senate to allow

resort to court action prior to conciliation efforts, this

could easily have been accomplished by reinserting the

“ in advance thereof” clause which was deleted in the

House. The Senate, however, made no such insertion and,

even more to the point, there are no statements from the

Senators to indicate that the Senate bill was to be con

strued as if the “ in advance thereof” clause had been in

serted. It having been the recognized intent of the House

to insure conciliation efforts before resort to court action

36 110 Cong. Rec. 13081 (June 9, 1964); and Senator Hum

phrey stated that the Senate changes “ gave increased emphasis

to methods of securing voluntary compliance.” 110 Cong. Rec.

12707 (June 4, 1964) ; and “We have placed emphasis upon vol

untary conciliation—not coercion.” 110 Cong. Rec. 14443 (June

19, 1964).

37 Berg, Equal Employment Opportunity Under the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 31 Brooklyn L. Rev. 62, 66 (1964).

it would be contrary to logic to imagine that this intended

procedure was eliminated in the Senate by inference and

without one word of explanation. Thus, when the Sen

ate bill went back to the House for approval, it was ex

plained by members of the House Judiciary Committee

that:

“ There is greater emphasis in the Senate amend

ments on arbitration and voluntary compliance than

there was in the House bill.” 38

The bill comes back to the House tempered and

softened.” 39

Adverting to the Senate proceedings, it was pointed out

that the compromise proposal was based upon the ac

cumulated experience of twenty-five states which have fair

employment practices laws. Senator Javits assured the

Senate that fears about the procedure of the compromise

were not warranted because “ in the 13 industrial states

of the north, since the first law of this kind was passed

there have been 19,439 cases” and “ only 18 have actually

gone to court” (110 Cong. Rec. 13089-13090, June 9, 1964).

As hereinbefore shown, Senator Saltonstall referred to the

experience in Massachusetts as gratifying, indeed. The

Senate obviously relied heavily upon such assurance's that

employers would not be harassed with frivolous litigation

and that the federal courts would not be flooded.

The experience of the states, showing that conciliation

is a successful means of obtaining voluntary settlement of

complaints of discrimination in employment, is not to be

lightly regarded. This court has already recognized that

conciliation provides a means for the Commission to settle

the matter “ in an atmosphere of secrecy without resorting

to the extreme measure of bringing a civil action in the

— A-10 —

38 110 Cong. Rec. 15876 (July 2, 1964) (Rep. Lindsay).

39 110 Cong. Rec. 15893 (July 2, 1964) (Rep. McCulloch).

A 11

congested federal courts,” Mickel, supra, 377 F. 2d 239,

241. The statute, §706 (a), 42 U. S. C., § 2000e-5 (a), di

rects that nothing said or done and as a part of “ such

endeavors” may he made public by the Commission with

out the written consent of the parties or used as evidence

in a subsequent proceeding. This section also makes it a

misdemeanor for any employee of the Commission to

divulge such information. If voluntary compliance with

these statutes is the first objective, and I think it is, the

prospect of willing cooperation is greatly diminished by

a suit instituted prior to conciliation efforts on the part

of the Commission. Publicity with respect to complaints

of discrimination might involve substantial dangers to

industrial peace. The pressures, publicity and adversary

attitudes which naturally follow the institution of a law

suit can make willing cooperation difficult, if not im

possible. Congress intended, in my view, that the Commis

sion should make the effort to eliminate alleged imlawful

employment practices by conferences with the employer,

by persuasion and by conciliation. Such is the sensible

approach before authorizing the aggrieved person to

plunge into litigation. I am persuaded that it is this

approach which Congress intended and for which it made

provision.

It is true that the courts are not in accord in their inter

pretation of these statutes, as pointed out in the majority

opinion. As these disagreements began to appear the

Commission may have been impelled to review and recon

sider the procedures which it had undertaken to follow.

In the instant cases the notification was sent to each plain

tiff that he could resort to court action prior to any con

ciliation effort by the Commission. Up to that time the

Commission had issued no formal or official interpretation

of the requirements of the statute with regard to whether

an effort to conciliate must precede the issuance of such

notice. But in November 1966 the Commission, perhaps

entertaining some doubt as to the legality of its procedure

employed in these and other cases, issued a Regulation

stating that it “ shall not issue a notice * * * where rea

sonable cause has been found, prior to efforts at concilia

tion with respondent,” except that, after sixty days from

the filing of the charge, the Commission will issue a notice

upon demand of either the charging party or the respond

ent (29 C. F. R., § 1601.25a).

If inability to undertake conciliatory procedures be at

tributable solely to a “ heavy case load,” as asserted by

the Commission, this would not be the first instance where

statutes could not be followed or enforced because of lack

of necessary implementation. If sufficient funds were not

appropriated to permit the Commission to function as in

tended this situation can and should be corrected, but this

is a problem which cannot be solved by the courts. Claims

of resulting unfairness to allegedly aggrieved persons have

been made in this and other courts if conciliation effort,

though unsuccessful, is held to be a prerequisite to resort

to the courts. It is clear that Congress intended to protect

aggrieved persons against violations of their civil rights

but it is clear also that Congress did not lose sight of

the unfairness which would result to parties against whom

charges are filed if they could be brought into court with

out the conciliation step.40

— A-12 —

40 See Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 265 F. Supp.

56, 62 (N. D. Ala. 1967).