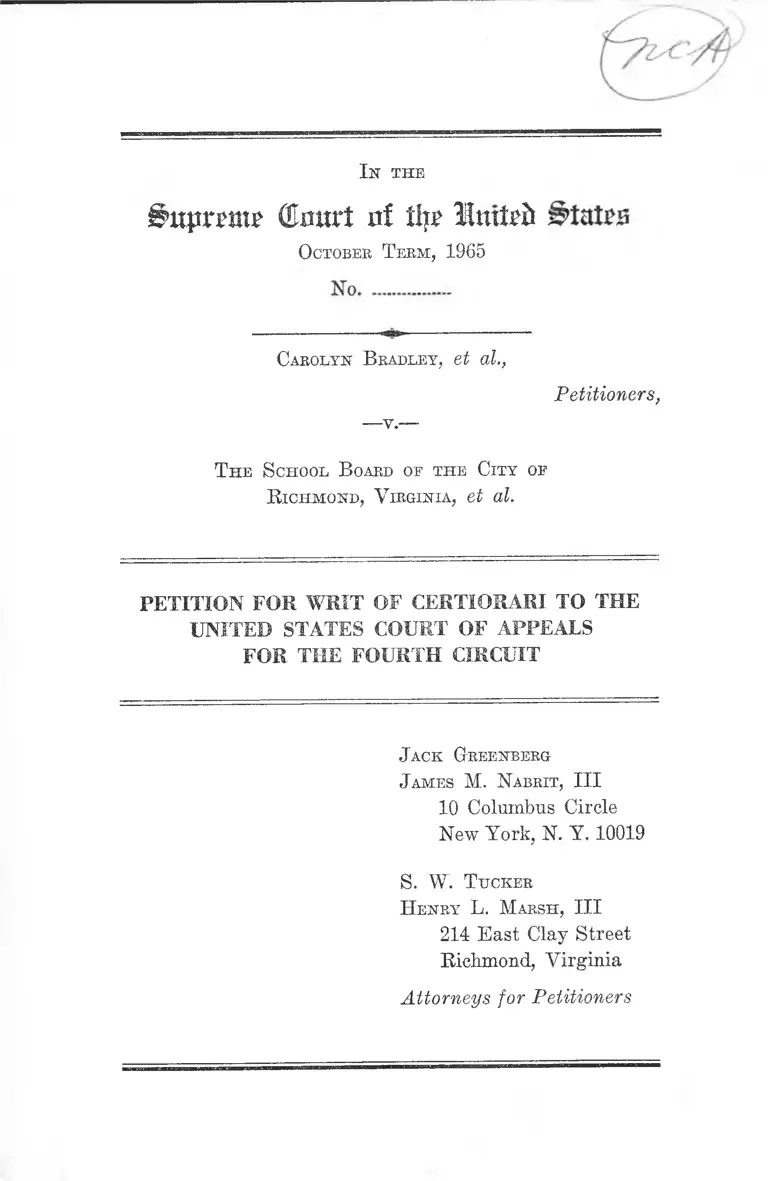

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1965. 5c0c9fa8-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c1554a0-9aa0-48ee-bb8a-617b362b48aa/bradley-v-school-board-of-the-city-of-richmond-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

§5>n$xmw ( ta r t 0! % H&mteb

O ctober T e e m , 1965

C arolyn B radley , et al.,

---y . _

Petitioners,

T h e S chool B oard of t h e C it y of

R ic h m o n d , V ir g in ia , et al.

PETITION FOB WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR. THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

J ack G reen b er g

J am es M . N abrit , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

S. W. T u c k e r

H e n r y L. M a r sh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below ......................................... 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ...................................................... 2

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions Involved........ 3

Statement ....................... 3

Reasons for Granting the W rit...................... 16

I. The Richmond Pupil Assignment Plan, Viewed

in the Context of Continuing Faculty Segre

gation and Other Factors, Is Fundamentally

Inadequate to Disestablish the Segregated

System of Schools ............................... 19

II. Segregation of Public School Teachers Vio

lates the Fourteenth Amendment and Negro

Pupils Are Entitled to Relief Against This

Element of Segregated School Systems ........ 25

Conclusion ...................................................................... 35

Appendix ....... la

Memorandum of July 25, 1962 ............................... la

Opinion of May 10, 1963 ......................................... 9a

Memorandum of March 16, 1964 ............................ 29a

11

PAGE

Order Dated March 16, 1964 .................................. 39a

Opinion of April 7, 1965 ......................................... 40a

Judgment Filed April 7, 1965 ................................ 71a

T able of C ases

American Enka Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 119 F. 2d 60 (4th

Cir. 1941) ..................................... .............................. 25

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 ........................... ...21, 30

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, 306 F. 2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962) ....................... 29

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31 ........................ .......... 25

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v.

Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964), cert, denied,

377 IT. S. 924 ........................................................ 28

Bowditch v. Buncombe County Board of Ed., 345 F. 2d

329 (4th Cir. 1965) ...................................................16, 28

Brooks v. School District of City of Moberly, Mo., 267

F. 2d 733 (8th Cir. 1959), cert, denied, 361 U. S. 894 .. 29

Browder v. Gayle, 352 U. S. 903 ................... ................ 26

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 349 IT. S.

294 ................................................................ 2, 6, 23, 25, 26,

28, 34, 35

Brown v. County School Board of Frederick County,

----- F. 2d — (4th Cir. No. 9825, May 24, 1965) .... 16

Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 (E. D. S. C. 1957),

judgment vacated 354 IT. S. 933 ................................ 32

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491

(5th Cir. 1962) 20

Ill

PAGE

Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F. 2d 302 (5th Cir. 1963), va

cated and remanded 377 U. S. 263 ..................... .....27, 29

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956) ....... . 20

Christmas v. Board of Education of Harford County,

231 F. Supp. 331 (D. Md. 1964) ........ ..................... 29

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission v. Conti

nental Air Lines, 372 U. S. 714.................................. 25

Dawson v. Baltimore City, 350 IT. S. 877 ....................... 26

Dillard v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville,

308 F. 2d 920 (4th Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 374 IT. S.

82 ................................................................................. 12

Dodson v. School Board of City of Charlottesville, 289

F. 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961) ...................................... .... 20

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 219 F. Supp. 427 (N. D. Okla. 1963) .......... 29

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

Civil No. 64-C-73-R, W. D. Va. June 3, 1965 ..........29, 30

Gilliam v. School Board of City of Hopewell, 345 F. 2d

325 (4th Cir. 1965) ............................. ....................... 28

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, 304 F. 2d

118 (4th Cir. 1962) .... .......... ............ ..... .................. 20

Griffin v. Board of Supervisors, 339 F. 2d 486 (4th

Cir. 1964) .............................. ...................................... 28

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, 377

IT. S. 218................................................................. . 26

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 IT. S. 879 26

IV

PAGE

Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg, 321

F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963) ........................................... 28

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61 .................................. 25

Lawrence v. Bowling Green, Ky. Board of Education,

Civil No. 819, 8 Race Bel. L. Rep. 74 (N. D. Ky.

1963) ........................................................................... 29

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U. S. 145..................... 24

Manning v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough

County, Fla., Civil No. 3554, 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 681

(S. D. Fla. 1962) ....................................................... 29

Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga,

319 F. 2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963) ..................................... 29

Mason v. Jessamine County, Ky. Board of Education,

Civil No. 1496, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 75 (E. D. Ky.

1963) ........................................................................... 29

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 .... 34

Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education, 232 F.

Supp. 288 (W. D. N. C. 1964), vacated 345 F. 2d 333

(4th Cir. 1965) ........................................... ............... 29

N. L. R. B. v. Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock

Co., 308 U. S. 241................... 24

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis, 302

F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962) ........................................... 20

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis, 333

F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) ........................................... 29

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 ............................ 25

Price v. The Denison Independent School District,

----- F. 2d------ (5th Cir. No. 21,632, July 2, 1965) .... 17

V

PAGE

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 ................. .................. 32

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, ----- F. 2 d ------ , 5th Cir. No. 22,527, June 22,

1965 .......................... ............ ...... ...... ......................... 19

Sperry Gyroscope Co., Inc. v. N. L. R. B., 129 F. 2d 922

(2nd Cir. 1942) ............... ........................................... 25

Tillman v. Board of Instruction of Volusia County,

Florida, Civil No. 4501, 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 687

(S. D. Fla. 1962) ....................................................... 29

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 .................................. 26

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S.

173 ............................................................................... 24

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, ——-

F. 2d----- (4th Cir. No. 9630, June 1, 1965) .......... 16, 28

S tatu tes

Ala. Acts 40, 41, 1956 1st Sp. Sess................. ................ 32

Ala. Acts 239, 361, 1957 Sess................................... ...... 32

Code of Va., 1950 (1964 Replacement VoL), §22-205 .... 27

Code of Va., 1950 (1964 Replacement Vol.), §22-207 .... 28

F. R. Civ. Proc., Rule 23(a) ....................................... 3

La. Acts 1956, Acts 248, 249, 250, 252 ......................... 32

S. C. Acts 1956, Act 741, repealed by Act 223 of 1957 .... 32

28 U. S. C. §1254(1) ...................................................... 2

vi

PAGE

28 IT. S. C. §1331........ .

28 U. S. C. §1343 .........

42 U. S. C. §§1981, 1983

42 U. S. C. A. §2000d ...

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

1960 Census of Population, Vol. 1, “Characteristics of

the Population,” Part I, U. S. Summary Table 230 .... 32

110 Cong. Eec. 6325 (daily ed. March 30, 1964) .......... 17

General Statement of Policies Under Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation

of Elementary and Secondary Schools, HEW Office

of Education, April 1964 .........................17,18,24,33,34

Lamanna, Richard A. “The Negro Teacher and Deseg

regation”, Sociological Inquiry, Vol. 35, No. 1, Winter

1965 ............................................................................. 32

Research Division—National Education Association,

Teacher Supply and Demand in Public Schools, 1965

(Research Report 1965-R10, June 1965) .................. 32

Southern Education Reporting Service, “Statistical

Summary of School Segregation—Desegregation in

the Southern and Border States”, 14th Rev., Nov.

1964 .................................-.......-...................... 10,23,30,31

............ 3

............ 3

............ 3

16,17, 33, 34

Southern School News, May 1965 17

I n' t h e

Bnpvmt (Emtrt stf tty IntM S>Uti>z

O ctober T e r m , 1965

No................

Carolyn B radley , et al.,

— v .—

Petitioners,

T h e S chool B oard of t h e C ity of

R ic h m o n d , V ir g in ia , et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to re

view the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit entered in the above-entitled cause

on April 7, 1965.

Citations to Opinions Below

The memorandum opinion of the District Court of July

25, 1962 (R. 1-61)1 is unreported and is printed in the ap

pendix hereto, infra p. la. The opinion of the Court of

Appeals issued May 10, 1963 (R. 1-76), printed in the ap-

1 The record contains Volumes I to VI. Each volume begins with

a page numbered 1. Thus record citations herein are to the volume

and page number as above indicating Volume I, page 61.

2

pendix hereto, infra p. 9a, is reported at 317 F. 2d 429.

The District Court’s opinion of March 16, 1964 (E. 1-128),

appears in the appendix below at page 29a. The second

opinion of the Court of Appeals dated April 7, 1965 (E.

V-5), printed in the appendix p. 40a, infra, is reported at

345 F. 2d 310.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

April 7, 1965 (E. V-36); appendix p. 71a, infra. Mr. Jus

tice Goldberg on June 28, 1965, extended the time for fil

ing the petition for certiorari until August 1, 1965. The

jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. Sec

tion 1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Whether the Eichmond, Virginia school board’s “free

dom of choice” policy is adequate under Brown v. Board of

Education to disestablish the system of racial segregation

created by past compulsory pupil assignment policies in the

context of a continuing practice of assigning all school

teachers on the basis of race in a segregated pattern.

2. Whether Negro pupils are entitled to demand a

prompt end to the school authorities’ practice of racially

segregating teachers by assigning them on the basis of

race as a violation of the pupils’ right to attend a non-

discriminatory public school system.

3

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions Involved

This ease involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

This cause was filed in the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia September 5, 1961, by

petitioners, a group of Negro parents and children in Rich

mond, Virginia, who sought injunctive relief against public

school segregation pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §1343 and 42

U. S. C. §§1981 and 1983.2 Petitioners sought an injunc

tion against the Richmond school board and superintendent

and against the Virginia Pupil Placement Board, a state

agency with statutory responsibilities concerning the as

signment of pupils. Petitioners here seek a review of the

adequacy of the school board’s desegregation plan which

was approved by the courts below.

The complaint, brought as a class action under Rule

23(a), F. R. Civ. Proc., alleged, inter alia, that the school

authorities had not devoted efforts toward initiating non

segregation and bringing about the elimination of racial

discrimination in the public school system and that they

had not “made a reasonable start to effectuate a transition

to a racially non-discriminatory system . . . ” (R. 1-11).

2 The complaint also alleged “Federal Question” jurisdiction

under 28 U. S. C. §1331.

4

The complaint as amended3 requested an order requiring

admission of the 11 minor petitioners in specified all-white

schools and also general injunctive relief against the segre

gated system and discriminatory practices. It included a

request that the defendants be required to submit to the

court a desegregation plan as well as periodic reports of

their progress in effectuating a transition to a racially non-

discriminatory school system (R. 1-36-37). Petitioners also

sought attorneys’ fees. The defendants generally denied

that petitioners were entitled to relief; the Richmond offi

cials contended that sole responsibility for placing pupils

was in the hands of the defendant Pupil Placement Board

(R. 1-53, 55).

July 23, 1962, the case was tried before Hon. John D.

Butzner, Jr.,4 and on July 25, 1962, Judge Butzner filed

an opinion (R. 1-61) and entered an injunction (R. 1-71)

against the defendants requiring the admission of ten peti

tioners to white schools,5 but refusing any general injunc

tion against discrimination.

Although all of the petitioners were thereby admitted to

white schools, they appealed the refusal to enter general

injunctive relief and to require a desegregation plan. The

Fourth Circuit (Judge Bryan dissenting) reversed and re

manded, directing entry of an injunction against the dis

criminatory practices and indicating that the school board

3 Following motions to dismiss the original complaint (R. 1-15,

20) the complaint was amended January 4, 1962 (R. 1-26). The

amended complaint alleged facts concerning the applications of the

individual plaintiffs’ admission to specified schools.

4 The transcript of the trial of July 23, 1962, is Yol. II of the

record.

5 The remaining infant petitioner had been admitted by the

school authorities prior to the hearing.

5

should be encouraged to submit a more definite plan for

termination of the discriminatory system (317 F. 2d 429,

May 10, 1963). The majority opinion contains a detailed

factual statement describing the segregated operation of

the Richmond schools, and the limited first steps which had

departed from total segregation. It referred to earlier

school segregation litigation in Richmond from 1958 to

1961 culminating in the admission of 1 Negro to a white

school by an order of District Judge Lewis, refusing any

class relief and dismissing the prior case from the docket/’

The Court of Appeals concluded that it found “nothing to

indicate a desire or intention to use the enrollment or as

signment systems as a vehicle to desegregate the schools”

and that the refusal to enter an injunction left the defen

dants “free to ignore the rights of other applicants” for

nonracial assignments.

When the present case commenced in September 1961

Richmond had 41,568 children (17,777 white and 23,791

Negro)7 attending 61 schools.8 Only 37 Negro children were

6 The Court of Appeals’ description of the prior case is in 317 F.

2d at 432, n. 3, 435. The prior suit. Warden v. School Board of

City of Richmond (E. D. Va„ July 5, 1961), unofficially reported

6 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1025, was filed September 2, 1958, by Negro

pupils who had been denied admission in two white schools. As

the Fourth Circuit observed, the school board converted the white

school which most of the plaintiffs sought to enter to a Negro

school by transferring out its white students and faculty and mov

ing in Negro students and faculty. A single remaining plaintiff

who sought transfer from a Negro school five miles from her home

to a white school in her neighborhood finally obtained admission

by the court order entered July 5, 1961, three years after her

original application. (School Board Minutes pertaining to the 1958

events described are Pi’s Exhibits 16 and 17 in the present record.)

7 Pi’s Exhibit 8, Depositions of Willet, et al. p. 8 (hereinafter

cited as Deposition).

8 (R. 1-43-44.)

6

assigned with whites at three schools (R. 1-45-46). The first

desegregation had begun in the 1960-61 term with 2 Negroes

in white schools. Judge Butzner’s opinion described the

manner in which pupils were initially placed in schools and

promoted from one to another on the basis of race through

use of dual overlapping attendance areas for Negroes and

whites. It also described the discriminatory application

of transfer criteria to those Negro pupils who actively

sought admission to white schools (R. 1-62-64, 66-68). Al

though the local school board professed not to have assign

ment power, it continued to maintain dual attendance areas

adopted before the Brown decision which governed an esti

mated 98% of the children who were placed routinely by

the Pupil Placement Board in accord with the locally estab

lished pattern. The routine placement of Negroes in all-

Negro schools was sought to be justified at the trial by the

authorities on the theory that Negroes preferred segrega

tion. Chairman Oglesby of the Placement Board testified

(R. 11-54-55):

Normally, I would say fully 99 per cent of the Negro

parents who are entering a child in First G-rade prefer

to have that child in the Negro school.

# # # # *

And it is true that in general there will be two schools

that that child could attend in his area, one white and

one Negro, and we assume that the Negro wants to go

to the Negro school unless he says otherwise, but if he

says otherwise, he gets the other school.

Pupils who sought transfers out of the zones were judged

by the Pupil Placement Board’s transfer standards. This

7

involved, the court found, the rejection of Negro transfer

applications on academic and residence standards not ap

plied to white pupils routinely enrolled in the same schools

(R. 1-65-68).

Richmond pupils had been assigned to schools on the

basis of separate overlapping attendance areas for Negroes

and whites for many years.9 Maps indicating the location

of schools and the areas for the high schools (Pi’s Ex. 5),

junior high schools (Pi’s Ex. 6) and elementary schools

(Pi’s Ex. 7) were introduced in evidence. Plaintiffs also

introduced school census data showing that Negroes and

whites lived in the same neighborhoods in many sections

of the City.10

The faculties in the white pupil schools were all white,

and the schools with Negro students had all Negro teachers

(Deposition 13). The school board’s Rules and Regulations

describe the personnel policies and procedures (Pi’s Ex. 1

at p. 28):

# # * # #

2. Assignment of Employees.

Each employee of the school board shall be assigned

to a specific position by and under the direction of the

superintendent of schools and may be transferred to

any other position for which qualified.

9 Testimony at pp. 27-28 illustrates the operation of the over

lapping zones, where white pupils and Negroes in the same areas

attend different schools.

10 See generally R. 11-12-24 explaining Pi’s Exhibits 12-15.

Exhibit 14, a plastic overlay, indicates the number of white and

Negro pupils by age group in each section of the City, and can be

compared with the school attendance areas when placed over Ex

hibits 5, 6 or 7.

3. Transfer of employees.

Transfer may be made by the superintendent on his

own authority or at the request of the employee for

any purpose which in the judgment of the superin

tendent is for the welfare of the employee or the

schools.

A statement of “Richmond Public Schools Administrative

Policies” (attached to Pi’s Ex. 1) indicates that the respon

sibility for personnel selection is shared by the administra

tion, Personnel Department and the school principal or

department head concerned. Teachers in Richmond are

given ten month contracts, serve a two year probation

when first employed, and thereafter usually have continuing

contracts which are renewed unless they are notified to

the contrary by April 15th of each year. (See Pi’s Ex. 1,

Rules and Regulations, Ch. VI, pp. 24-31.)

The evidence showed a pattern of severe overcrowding

in Negro schools and under-utilization of white schools. As

the Court of Appeals observed (317 F. 2d at 435), the

authorities had not dealt with overcrowding by assigning

Negro pupils to schools with white children which had

available space in the same areas (R. 11-32). Instead, they

built new schools for Negroes and converted white schools

to all-Negro schools {ibid.). At the time of the trial 90

Negro children had been granted transfers to white schools

for the 1962-63 term in addition to the 37 enrolled during

the 1961-62 year (R. 11-77-78).

After the Fourth Circuit remanded the case the district

court entered an order June 6, 1963, enjoining the defen

dants from refusing the admission of any pupil to any

9

public school on the basis of race, from assigning pupils

on the basis of dual overlapping zones, from assigning

pupils on the basis of race upon promotion from one school

to another, and from conditioning the grant of transfers

on the applicants’ submission to futile, burdensome or dis

criminatory procedures (R. 1-97-98). The court also invited

the defendants to submit a desegregation plan, and stipu

lated that the injunction would be superseded by an ap

proved plan (R. 1-98).

On July 11, 1963, plaintiffs moved for further injunctive

relief challenging the school board’s action in assigning

pupils for the forthcoming term in accord with a resolution

the board had adopted March 18, 1963 (B. X-100). At the

hearing on this motion on July 29, 1963 (E. Volume III),

the school board filed its March 18, 1963 resolution and

requested that the court approve it as a plan of desegrega

tion (Defendants’ Ex. 1 and la). The full text of the resolu

tion is set out in the margin.11

11 “Whereas, the Richmond School Board has been advised by

special counsel and the City Attorney that in order to comply with

the decision of the Federal District Court in the case of Bradley

v. The School Board of the City of Richmond and the State Pupil

Placement Board, the school attendance areas previously estab

lished for white and Negro schools may no longer he used in the

assignment of pupils.

“Now, Therefore, he it Resolved as follows:

“ (a) Recommendations for assignment of pupils seeking

enrollment in the public school system for the first time or

initial enrollment in the junior or senior high schools shall be

made upon consideration of the distance the pupils live from

such schools; the capacity of such school; availability of space

in other schools; whether the program of the pupil can be

met by such school; the school preference as shown on the

pupil placement application form; and what is deemed to be

in the best interest of such pupil.

“ (b) The school administration shall recommend that pupils

be assigned to the schools which they attended the preceding

10

At the hearing the superintendent testified that for the

then forthcoming 1963-64 term dual attendance zones had

been abolished and no new zones were adopted (R. III-6, 8);

that all pupils entering school were required to apply for a

specific school (R. III-8); that every child finishing the

top grade in elementary school or junior high school was

required to choose a school (ibid. ) ; that no Negro applicant

to a white school was denied admission (ibid.)-, that the

only criteria applied thus far were school capacity (but this

had not resulted in denial of any Negro application to a

white school) (R. III-10) and a May 31st deadline for

transfers (R. 111-12); that pupils enrolled in a school con

tinued in that school unless they requested to move out or

reached the top grade (R. III-17-18); that a total of 239

Negroes applied before the deadline and were admitted at

white schools (148 finishing highest grade in school, 81 in

grades below top grade, 10 beginning school) (R. III-22).12

year, except those eligible for promotion to another school.

However, application may be made by the parent, guardian

or other person having custody of such pupils for their place

ment in another school named in the application in which case

the reason for the requested transfer should be stated. The

school administration may recommend to the Pupil Placement

Board that such application be approved if it be deemed to be

in the best interest of the pupil.

“ (c) Applications for transfers to a particular school must

be made and received by the school administration before

June 1 preceding the school year to which the placement

requested is to be applicable.” (Defendant’s Exhibits 1 and

la.)

12 No current figures on Richmond desegregation are in the rec

ord. A. published report indicates that in November 1964 there

were 846 Negro children attending 13 schools with white children.

This represented about 3% of the Negroes in the system. Southern

Education Reporting Service, “Statistical Summary of School

Segregation—Desegregation in the Southern and Border States”,

14th Rev., Nov. 1964, p. 59.

11

After hearing this testimony the Court set dates for the

petitioners to file exceptions to the plan as it had been

explained and indicated it would schedule a further hearing

on the proposed plan.

On August 22, 1963, plaintiffs filed exceptions to the

plan attacking it as vague and indefinite and conferring

absolute discretion on the school authorities to determine

assignments, and asserting that as the plan had no specific

school zones the plan “affords the Court no basis upon

which to appraise the practical impact of an order approv

ing the plan or any part of it” (R. 1-110-111). The peti

tioners objected to the provision granting transfers if

“deemed to be in the best interest of the pupil” and also

objected that the plan “omits any provision for the assign

ment or reassignment of teachers and staff of the schools

on a nonracial basis” saying they were asserting “their per

sonal rights to attend a school system in which there is no

racial segregation or discrimination” (R. 1-112).

September 9, 1963, plaintiffs filed a motion for a tempo

rary restraining order to require the admission at a white

high school of two Negro pupils who had been denied trans

fers on the ground that their applications were not received

before the deadline. The Court granted the restraining

order on the basis of the prior injunction (R. 1-123), and it

was subsequently made permanent (R. 1-143-144).

On December 20, 1963, there was a further hearing on

the plan and on petitioners’ motion for attorneys’ fees (R.

Volume IV). By agreement prior evidence was considered

part of the evidence on the plan. The application forms

were placed in evidence ;1S the superintendent indicated that

13 Curiously, the statewide Pupil Placement form (Def’s Ex. 3)

has no space designated for pupils to indicate the school they desire

12

pupils other than those completing the last grade in a

school were asked to state the reason they sought a trans

fer. The superintendent stated that in 1963 there was one

instance in which about 40 or 50 white children applied

to a school that was overcrowded and “the parents were

consulted” but no one was “sent to a school against his

will” (R. IY-10). Counsel for the Pupil Placement Board

advised the Court that that board approved the plan (R.

IV-19).

The superintendent testified at the July hearing that the

school board’s purpose was to follow a “freedom of choice”

plan similar to the one in Baltimore, and that the board

had been guided in this by a suggestion made by the Fourth

Circuit in the Charlottesville14 case (R. III-7).

On March 16, 1964, Judge Butzner approved the plan

and dissolved the injunction entered June 6,1963 (R. 1-128).

The Court said that while the plan was framed in broad

language, it was valid as it was being administered and

interpreted; that the “best interest” criterion could not be

used to deny transfers or admission unless made more defi

nite; and that the school capacity criterion presented no

problem at present but that if the situation changed resi

dential requirements must avoid discrimination. The Court

said that the absence of provision for faculty desegregation

did not require rejection of a plan for the assignment of

pupils.

to attend. But the superintendent testified that all parents were

required to indicate the school they chose when the child entered

school or finished the highest grade in a school.

14 Dillard v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, 308 P.

2d 920, 923-924 (4th Cir. 1962), cert, denied 374 U. S. 827.

13

On petitioners’ appeal the Fourth Circuit, en banc, af

firmed, with Judges Sobeloff and Bell dissenting in part

(345 F. 2d 310; appendix 40a). The Court held that the

plan allowing “free transfers is an acceptable device for

achieving a legal desegregation of schools,” noting that

the Court required “the elimination of discrimination from

initial assignments as a condition of approval of a free

transfer plan” and that “discrimination is eliminated as

readily by a plan under which each pupil initially assigns

himself as he pleases as by a plan under which he is in

voluntarily assigned on a geographic system” (345 F. 2d

at 318-319). The court said that the board might have estab

lished a single zone system for initial placements but that

“would have been a major task” and that eliminating zon

ing was the equivalent of rezoning and “easier of accom

plishment” when the board intended to allow pupils to

choose schools in any event (ibid.).

The Court held that the District Court did not abuse its

discretion in declining to order staff desegregation, stating

that there was no inquiry “as to the possible relation, in

fact or in law, of teacher assignments to discrimination

against pupils” or as to the impact of an order upon the

administration of the schools, and thus petitioners had not

“discharged the burden they must shoulder of showing that

such assignments effect a denial of their constitutional

rights” (345 F. 2d at 320). The Court said, in part:

Whether and when such an inquiry is to be had are

matters with respect to which the District Court also

has a large measure of discretion. The Fifth and Sixth

Circuits have so held, and we agree. When direct

measures are employed to eliminate all direct discrimi-

14

nation in the assignment of pupils, a District Court

may defer inquiry as to the appropriateness of sup

plemental measures until the effect and the sufficiency

of the direct ones may be determined. The possible

relation of a reassignment of teachers to protection of

the constitutional rights of pupils need not be deter

mined when it is speculative. When all direct discrimi

nation in the assignment of pupils has been eliminated,

assignment of teachers may be expected to follow the

racial patterns established in the schools (ibid.) (foot

notes omitted).

The Court affirmed the disallowance of counsel fees as

within the trial judge’s discretion saying that an award was

required “only in the extraordinary case” (id. at 321).

Judges Sobeloff and Bell concurred in approval of the

freedom of choice plan but made their “concurrence tenta

tive on the assumption that the Resolution is an interim

measure only and will be subject to a full review and re

appraisal at the end of the present school year, or certainly

not later than this fall after the opening of the 1965-66

school term, when the results of two years of the Resolu

tion’s operation will be known” (345 F. 2d at 321). They

said that they were “not fully persuaded that the plan will

be enough to enable the Negro pupils to extricate them

selves from the segregation which has long been firm ly

established and resolutely maintained in Richmond” (id. at

322), and that much depended upon the board’s attitude,

which in the past had been that it had no duty “to integrate

a particular school or desegregate it” or “to promote inte

gration.” They asserted that “good faith compliance re

quires administrators of schools to proceed actively with

15

their nontransferable duty to undo the segregation which

both by action and inaction has been persistently perpetu

ated” {id. at 323).

Judges Sob el off and Bell dissented from the rulings con

cerning staff desegregation, the dissolution of the 1963 in

junction, and counsel fees. On the teacher issue they wrote

{id. at 324) :

The composition of the faculty as well as the com

position of its student body determines the character

of a school. Indeed, as long as there is a strict sepa

ration of the races in faculties, schools will remain

“white” and “Negro,” making student desegregation

more difficult. The standing of the plaintiffs to raise

the issue of faculty desegregation is conceded. The

question of faculty desegregation was squarely raised

in the District Court and should be heard. It should

not remain in limbo indefinitely. After a hearing there

is a limited discretion as to when and how to enforce

the plaintiffs’ rights in respect to this, as there is in

respect to other issues, since administrative considera

tions are involved; but the matter should be inquired

into promptly. There is no legal reason why desegre

gation of faculties and student bodies may not proceed

simultaneously.

16

Reasons for Granting the Writ

This case involves two of the issues of greatest current

concern in school segregation litigation throughout the

South, the question of the adequacy of so-called freedom

of choice desegregation plans to disestablish patterns of

racial segregation created by governmental compulsion in

the context of continuing faculty segregation, and the right

of Negro pupils to demand a prompt end of the practice of

assigning teachers on the basis of the race of the pupils in

schools. Adoption of the Richmond plan and approval of

it by the Fourth Circuit has been emulated widely by

school districts and courts. At least four cases involving

comparable issues already have been decided by the Fourth

Circuit, and the views expressed in the Richmond case have

been reaffirmed.16 Indeed, the major new phenomenon in

school desegregation litigation is the sudden abandonment

of age-old normal school zoning practices and adoption of

so-called free choice plans.

The issue of faculty desegregation is of transcendent

importance in thousands of school districts where teachers

are still assigned on the basis of race in a segregated pat

tern. The United States Commissioner of Education, as

authorized by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,16

16 See, e.g., Bowditch v. Buncombe County Board of Education,

345 F. 2d 429 (4th Cir. 1965) • Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of

Education, 345 F. 2d 333 (4th Cir. 1965); Brown v. County School

Board of Frederick County, ----- F. 2 d ----- (4th Cir. No. 9825,

May 24, 1965) ; Wheeler v. The Durham City Board of Education,

----- F. 2 d ------ (4th Cir. No. 9630, June 1, 1965).

16 Title VI conditions federal financial assistance on nondiscrimi

nation. Act of July 2, 1964, P. L. 88-352, Title VI, 72 Stat. 252,

42 U. S. C. A. §2000d, et seq.

17

lias adopted a rule requiring that all desegregation plans

submitted by districts receiving federal financial assistance

“shall provide for the desegregation of faculty and staff”

by making “initial assignments” nonracially and by steps

toward the elimination of teacher and staff segregation

resulting from prior assignments based on race.17 It is

important that this Court announce a similar unequivocal

position against faculty segregation practices to establish

a uniform rule for those districts in litigation (and sub

mitting court approved plans as the basis for federal aid)

and those submitting plans to the Commissioner of Edu

cation. The Congressional proponents of the Civil Eights

Act of 1964 proceeded on the express assumption that the

Commissioner could require faculty desegregation. Intro

ducing Title VI, Vice President (then Senator) Humphrey

made express reference to a Fifth Circuit opinion requir

ing faculty desegregation which this Court had declined

to review, saying:

In such cases the Commissioner might also be jus

tified in requiring elimination of racial discrimination

in employment or assignment of teachers at least

where such discrimination affected the educational op

portunities of students. See Board of Education v.

Braxton [326 F. 2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964)].

This does not mean that Title VI would authorize

a federal official to prescribe pupil assignments, or to

17 General Statement of Policies Under Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation of Elementary and

Secondary Schools, HEW, Office of Education, April 1964, Part V.

B (l) (cited hereinafter as General Policy Statement). This State

ment is reprinted in the appendix to Price v. The Denison Indepen

dent School District,----- F. 2 d ----- (5th Cir. No. 21632, July 2,

1965), and also in Southern School News, May 1958, p. 8.

18

select a faculty, as opponents of the bill have sug

gested. The only authority conferred would be au

thority to adopt, with the approval of the President,

a general requirement that the local school authority

refrain from racial discrimination in treatment of

pupils and teachers and authority to achieve compli

ance with that requirement by cutting off funds or by

other means authorized by law. (110 Cong. Rec. 6325

(daily ed. March 30, 1964))

However, the prospect of federal administrative pres

sure for faculty desegregation does not eliminate the

urgent need for a similar expression from this Court.

First, with respect to particular districts in litigation, the

Commissioner of Education has indicated that a “final

order of a court of the United States” will be accepted in

lieu of a plan submitted to the agency (General Policy

Statement, parts II.B and IV). Court orders finally ap

proving plans which fail to contain basic provisions like

faculty desegregation will work to create conflict. As

Judge Wisdom of the Fifth Circuit recently wrote:

The judiciary has of course functions and duties dis

tinct from those of the executive department, but in

carrying out a national policy we have the same ob

jective. There should be a close correlation, therefore,

between the judiciary’s standards in enforcing the na

tional policy requiring desegregation of public schools

and the executive department’s standards in admin

istering this policy. . . . If in some district courts

judicial guides for approval of a school desegregation

plan are more acceptable to the community or sub

stantially less burdensome than H. E. W. guides, school

19

boards may tarn to the federal courts as a means of

circumventing the H. E. W. requirements for financial

aid. (Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District,----- F. 2d------ , 5th Cir. No. 22,527, June 22,

1965.)

Second, with respect to general standards the Commis

sioner obviously will be guided to some substantial degree

by the legal principles emanating from the courts. Judi

cial declarations casting doubt on the necessity for faculty

desegregation might immeasurably impair and stir re

sistance to the effective administration of the Commis

sioner’s existing policy implementing the Act of Congress.

I.

The Richmond Pupil Assignment Plan, Viewed in the

Context of Continuing Faculty Segregation and Other

Factors, Is Fundamentally Inadequate to Disestablish

the Segregated System of Schools.

Richmond’s plan for assigning pupils, or rather, not

assigning them, to schools is basically inadequate to effec

tuate the constitutionally required transition of a racially

segregated school system to one operated without dis

crimination. There is no question here of the right of a

school board in the abstract to allow pupils to choose their

schools. The question is whether adoption of a policy pro

viding for pupils to choose their schools is adequate to

undo the effects of past wrongs, and discharge the duty

to eliminate a segregated system. Petitioners submit that

a school board does not adequately discharge its affirma

tive duty to initiate desegregation when, after years of

actively placing pupils in schools on a segregated basis,

20

it adopts a “hands-off” attitude about pupil placements

while maintaining faculty segregation in the schools.

Richmond traditionally has placed pupils in schools by

the use of geographic attendance areas, allowing pupils

choice in some situations between two schools in the same

vicinity. Separate schools and attendance areas were main

tained for Negroes. The totally segregated situation ex

isting before, and for a number of years after, Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, was entirely the work

of state agents. The authorities’ attempt to evade com

pliance with Brown through grossly discriminatory appli

cation of the Virginia Pupil Placement law is spread on

the record of this case, and recounted in the first opinion

of the court below (317 F. 2d 429). In the era before the

courts finally denounced use of the “pupil placement laws”

to maintain segregation by initial placements based on

race and discriminatory transfer procedures for those who

sought to escape segregation,18 segregationist school boards

widely proclaimed as the utmost wisdom a judicial declara

tion that “ [s]omebody must enroll the pupils in the schools.

They cannot enroll themselves; and we can think of no one

better qualified to undertake the task than the officials of

the schools and the school boards having the schools in

charge” (Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956)).

Faced with judicial condemnation of their pupil place

ment scheme, and the knowledge that assignment of chil-

18 See, for example, Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke,

304 F. 2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962) ; Dodson v. School Board of City of

Charlottesville, 289 F. 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961) ; Bush v. Orleans

Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491, 498 (5th Cir. 1962) ; North-

cross v. Board of Education of Memphis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir.

1962).

21

dren by fairly drawn geographic areas in Richmond would

result in desegregation of a substantial number of schools

and the assignment of white children to Negro schools,19

the authorities have announced the principle of “free

choice.” They have done so fortified by the knowledge

that social pressure will tend to preserve much of the

pattern of segregation, their theory that “99 per cent of

the Negro parents . . . prefer . . . the Negro school” (R.

11-54), and the continued practice of faculty segregation

which proclaims the pattern the state has struggled to

preserve, so that no one can mistake a “Negro school” or

a “wdiite school.”

Faculty segregation is the key factor in the equation.

It racially identifies schools as effectively as a sign over

the door and enables the plan to offer parents a choice

between a Negro-faculty school and a white-faculty school.

Continued faculty segregation obviously discourages whites

from attending Negro schools no matter how accessible or

convenient. The principal implication of segregation prac

tices, that Negroes are considered inferior and unfit to

associate with whites, is surely not lost on white parents

confronted with a school board policy which indicates by

its very existence that the race of teachers makes a dif

ference and is something to be taken into account in organ

izing schools. Cf. Anderson v. Martin, 375 IT. S. 399. Nor

is it lost on Negro parents that the school authorities are

moving only grudgingly under pressure, clinging to ves

tiges of the segregated system to make it clear that at least

as a gross proposition Negro pupils enter white schools

19 See the maps and overlays indicating the number of pupils in

various areas of the city discussed in note 10, supra.

22

as unwelcome aliens, and that the school board will never

take the initiative to put them there. Negroes know that

Negro teachers face a diminishing need for their services

to the extent that Negro pupils choose desegregated schools

if Negroes are excluded from the possibility of assignments

to teach white children. Teachers who are a significant

portion of the Negro leadership group are thus faced with

a cruel dilemma by the school authorities.

A basic effect of the free choice plan—especially when

combined with faculty segregation—is to perpetuate the

all-Negro school. The board knows that there are no ap

plications by whites to attend Negro schools. It also knows

that although initially white schools have the capacity to

absorb some Negro pupils in vacant seats, that capacity

is finite and indeed very limited when compared with the

total number of Negro pupils. The promise to deal with

such an overcrowding by prescribing attendance zones or

some geographic standard if more Negroes apply to a

white school than it can hold, is no complete answer. It

apparently ignores the obligation of the school board to

prevent overcrowding in Negro schools by assigning Negro

pupils to nearby white schools with vacant space in order

to provide an equal educational opportunity in both schools.

The school board’s theory that it will not force Negro

children to go to school with whites and that there is noth

ing wrong with “voluntary” pupil segregation, coupled

with mandatory teacher segregation, runs afoul of its ob

ligation to provide equal educational opportunity without

regard to race.

The so-called freedom of choice—joined with staff seg

regation—plan represents a partial abdication of the school

23

board’s duty to insure equal education by equal utilization

and allocation of available facilities. There is no evidence

to support, and good reason to doubt, the conclusion of the

court below that a free choice plan is “administratively, far

easier of accomplishment” than a plan of initially placing

pupils in schools. It is as reasonable to think that large

numbers of transfers would make planning for the future

infinitely more difficult and complicated, and render useless

the normal type of projections of school enrollments used

in school building plans and the like under the previous

zoning system. (See Pi’s Ex. 2—the school board’s five

year projection of enrollments in each school from the

1962-63 to 1966-67 term.) The projected administrative

feasibility of the freedom of choice plan seems clearly

linked to an expectation that relatively few of the more

than 23,000 Negroes in the system will transfer to white

schools.

None of the above is intended to deny a school board’s

abstract, hypothetical, right to adopt a free choice plan in

other circumstances. The school board relies on the fact

that Baltimore used such a plan. As Judges Sobeloff and

Bell pointed out in their concurring opinion, Baltimore had

an entirely different official response to the Brown decision

than Richmond did. And Baltimore, which had free choice

before Brown, desegregated its faculties.20 The majority

below apparently rejects the suggestion of Judges Sobeloff

and Bell that the free choice plan cannot be properly ap

praised until experience indicates how it works, and seems

20 “Statistical Summary of School Segregation—Desegregation,”

supra, p. 31, indicates Baltimore City had 2,052 Negro teachers in

desegregated positions.

24

to decide that the method of allowing parents to choose

schools is unobjectionable per se and thus it does not matter

to what extent the method actually desegregates the school

system. It should be noted that the Commissioner of Edu

cation, while indicating that freedom of choice plans as

well as other types of plans may be submitted to the Office

of Education, has served advance notice that actual per

formance will be a test in evaluating plans to determine

if they accomplish the purposes of the Civil Rights Act

(General Policy Statement, supra, part V. B.(6)), and that

periodic compliance reports will be required.

Courts of equity have in other circumstances required

wrongdoers to do more than cease their unlawful activities

and compelled them to take further affirmative steps to

undo the effects of their wrongdoing. This Court only re

cently approved such a decree in Louisiana v. United States,

380 U. S. 145, 154, saying:

[T]he court has not merely the power but the duty

to render a decree which will so far as possible elimi

nate the discriminatory effects of the past as well as

bar like discrimination in the future.

Analogies exist under the Sherman Antitrust Act, where

unlawful combinations are commonly dealt with through

dissolution and stock divestiture decrees (see, e.g. United

States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 IJ. S. 173, 189, and

cases cited), and under the National Labor Relations Act

where it was early recognized that disestablishment of an

employer-dominated labor organization “may be the only

effective way of wiping the slate clean and affording the

employees an opportunity to start afresh in organizing

. . . ” (N. L. R. B. v. Newport News Shipbuilding <& Dry

25

Dock Co., 308 U. S. 241, 250).21 Similar equitable princi

ples should be applied here where the school board has

adopted the method of operation least calculated to extend

a desegregated education to large numbers of pupils.

II.

Segregation of Public School Teachers Violates the

Fourteenth Amendment and Negro Pupils Are Entitled

to Relief Against This Element of Segregated School

Systems.

The segregation of public employees by race plainly vio

lates the Fourteenth Amendment under principles settled

in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 II. S. 483, 349 U. S.

294, and the long line of cases applying the Amendment to

prohibit all racial discrimination by the states.22 Diserimi-

21 See also American Enka Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 119 F. 2d 60, 63

(4th Cir. 1941). In Sperry Gyroscope Co. Inc. v. N. L. R. B., 129

F. 2d 922, 931-932 (2nd Cir. 1942), Judge Jerome Frank compared

Labor Board orders requiring disestablishment of company-dom

inated unions to “the doctrine of those cases in which a court of

equity, without relying on any statute, decrees the sale of assets

of a corporation although it is a solvent going concern, because the

past repeated unconscionable conduct of dominating stockholders

makes it highly improbable that the improper use of their power

will ever cease” (citing cases).

22 In a unanimous opinion this Court said:

“ . . . [UJnder our more recent decisions any state or

federal law requiring applicants for any job to be turned away

because of their color would be invalid under the Due Process

Clause of the Fifth Amendment and the Due Process and

Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission v. Continental Air Lines,

372 U. S. 714, 721.

See also, Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61 (courtroom) ; Bailey

v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31 (transportation) ; Peterson v. Greenville,

26

nation in the hiring and assignment of public school

teachers surely violates the teachers’ rights. The defen

dants cannot seriously contend to the contrary. The only

possible justification for withholding relief is that peti

tioners who are public school pupils are not entitled to

invoke the aid of the courts to halt the admittedly unlawful

practice. Petitioners submit that the unlawful practice is

closely linked to their right under Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 349 U. S. 297, to have the district courts supervise

the effectuation of “a racially nondiseriminatory school

system” (349 U. S. at 301, emphasis added). The Court in

deciding the second Brown case, supra, pointed to admin

istrative problems related to “the physical condition of the

school plant, the school transportation system, personnel,

revision of school districts and attendance areas into com

pact units to achieve a system of determining admission

to the public schools on a nonracial basis, and revision of

local laws and regulations . . . ”, as matters to be considered

in appraising the time necessary for good faith compliance

(emphasis added). We believe that the Court plainly re

garded the task as one of ending all discrimination in school

systems, including discrimination in the transportation sys

tem, attendance districts or the other factors mentioned.

The delay countenanced by the “deliberate speed” doctrine

was predicated on the assumption that dual school systems

would be reorganized.

373 U. S. 244 (restaurant) ; Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350

(airport restaurant) ; Browder v. Gayle, 352 U. S. 903 (buses) ;

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U. S. 218

(schools) ; Dawson v. Baltimore City, 350 U. S. 877 (municipal

beaches); Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 (municipal golf

courses).

27

The brief of the United States, as amicus curiae, in

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 'U. S. 263, argued in this Court

that:

Obviously, a public school system cannot be truly non-

discriminatory if the school board assigns school per

sonnel on the basis of race. Full desegregation can

never be achieved if certain schools continue to have

all-Negro faculties while others have all-white faculties.

Schools will continue to be known as “white schools”

or “Negro schools” depending on the racial composi

tion of their faculties. It follows that the school au

thorities must take steps to eliminate segregation of

personnel as well as pupils. (Brief of the United

States, pp. 39-40.)

The Court in Calhoun vacated the judgment without dis

cussion of this issue. We submit that this case presents an

appropriate occasion to consider this question.

The record indicates the complete segregation of school

faculties and the general personnel policies of the school

system (see pp. 7-8, supra). Virginia law, and the personnel

policies of Richmond, authorize the superintendent to as

sign and reassign teachers and other staff serving the

pupils. Code of Va. 1950 (1964 Replacement Vol.), §22-205.23

23 Section 22-205 provides :

Assignment of teachers, including principals, by superinten

dent.—The division superintendent shall have authority to

assign to their respective positions in the school wherein they

have been placed by the school board all teachers, including

principals, and reassign them therein, provided no change or

reassignment shall affect the salary of such teachers; and

provided, further, that he shall make appropriate reports and

explanations on the request of the school board.

Another Virginia law enacted in 1962, Code of Va, 1950

(1964 Replacement Vol.), §22-207, plainly encourages

teacher segregation by expressly authorizing teachers to

terminate their contracts with school boards if pupils or

teachers at their schools are desegregated.24 This law,

plainly enacted in defiance of Brown, shows the link be

tween teacher and pupil segregation in segregationists’

thinking.

But the Fourth Circuit has not stated its disapproval of

faculty segregation in any of the cases in which it has con

sidered the matter26 and apparently has adopted the view

24 §22-207. Written contracts with teachers required; termination

by teachers.—Written contracts shall be made by the school board

with all public school teachers, except those temporarily employed

as substitute teachers, before they enter upon their duties, in a

form to be prescribed by the Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Such contracts shall be signed in duplicate, each party holding a

copy thereof.

Every such contract hereafter entered into, whether or not

expressly provided therein, may be terminated by the teacher, by

notice in writing to the local school board, at any time after loth

white and Negro pupils shall have leen enrolled, or loth white and

Negro teachers shall have leen employed, in the school to which

the contracting teacher is assigned. (Emphasis supplied.)

(The second paragraph was added by a 1962 amendment: Acts of

Va. 1962, chapter 183.)

25 Faculty segregation was first considered by the Fourth Circuit

m Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d

230, 233 (4th Cir. 1963), where it held that a complaint asking

for desegregation of a school system was sufficient to raise the

question. See also, Griffin v. Board of Supervisors, 339 F. 2d

486, 493 (4th Cir. 1964) ; Bowditch v. Buncombe County Board

of Ed., 345 F. 2d 329, 332, 333 (4th Cir. 1965) ; Wheeler v.

Durham City Board of Education, ------ F. 2d ___ (4th Cir.

No. 9630, June 1, 1965), and Gilliam v. School Board of City of

Hopewell, 345 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1965).

In the Fifth Circuit see: Board of Public Instruction of Duval

■County v. Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616, 620 (5th Cir. 1964), cert.

29

that faculty desegregation must depend upon some kind

of evidentiary showing by plaintiff Negro pupils that they

are disadvantaged by the practice in the circumstances of

the particular case. That is the only reasonable explana

tion for the Fourth Circuit’s repeated statements in cases

where the existence of faculty segregation is undisputed,

that there was insufficient showing that faculty segregation

was a denial of plaintiffs’ constitutional rights. The Fourth

Circuit apparently accepts the standing of pupils to litigate

the question but demands that they prove that faculty

segregation is a discrimination against them—as opposed

to a discrimination against the teachers themselves.

denied 377 U. S. 924 (affirming a trial court order requiring a

faculty desegregation plan). See also Augustus v. Board of Public

Instruction of Escambia, County, 306 F. 2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962) ;

Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F. 2d 302 (5th Cir. 1963), vacated and

remanded 377 U. S. 263.

The Sixth Circuit has twice held that it was proper for pupils

and their parents to raise the issue of segregation of teachers.

Ma-pp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga, 319 F. 2d

571, 576 (6th Cir. 1963) ; Northcross v. Board of Education of

City of Memphis, 333 F. 2d 661, 666 (6th Cir. 1964).

Several other courts have discussed the question of segregation

of teachers with a variety of results. Brooks v. School District

of City of Moberly, Mo., 267 F. 2d 733 (8th Cir. 1959), cert,

denied 361 IT. S. 894 (1959) (teacher firing); Franklin v. County

Scool Board of Giles County, Civil No. 64-C-73-B, W. D .Va.,

June 3, 1965 (same) ; Christmas v. Board of Education of Har

ford County, 231 F. Supp. 331 (D. Md. 1964) ; Nesbit v. Statesville

City Board of Education, 232 F. Supp. 288 (W. D. N. C. 1964),

vacated, 345 F. 2d 333 (4th Cir. 1965) ; Tillman v. Board of In

struction of Volusia County, Florida, Civil No. 4501, 7 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 687 (S. D. Fla. 1962) ; Manning v. Board of Public Instruc

tion of Hillsborough County, Fla., Civil No. 3554, 7 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 681 (S. D. Fla. 1962) ; Lawrence v. Bowling Green, Ky. Board

of Education, Civil No. 819, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 74 (N. D. Ky.

1963) ; Mason v. Jessamine County, Ky. Board of Education, Civil

No. 1496, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 75 (E. D. Ky. 1963) ; Dowell v. School

Board of Oklahoma City Public Schools, 219 F. Supp. 427 (N. D.

Okla. 1963).

30

But, as Judges Sobeloff and Bell have said, faculty segre

gation obviously makes student desegregation more diffi

cult. To the extent that students or parents are given a

choice between schools, faculty segregation encourages

them to make their choice on a racial basis. The very exist

ence of faculty segregation reflects the school authorities’

judgment that the race of teachers is significant and makes

a difference. Cf. Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399. This

is obvious in the context of states where school segregation

has been defended vigorously by public officials for a decade

since Brown.

Faculty segregation assures continuance of the prevail

ing trend of one-way desegregation, i.e., movement of Negro

pupils to formerly white schools without any corresponding

movement of white pupils to Negro faculty schools.

Throughout the southeast part of the country there are few

exceptions to this brand of “desegregation” which leaves

the “Negro” school intact with an all-Negro student body

and faculty.26 If the established trend continues it may

have extraordinarily serious implications threatening the

jobs of large numbers of Negro teachers. They are not

assigned to teach white pupils and face the departure of

some Negro pupils to white-faculty schools, with a corre

sponding decrease in demand for their services. A recent

decision by Judge Michie in the Western District of Vir

ginia enjoined school authorities who discharged every

Negro teacher in a small system when the schools desegre

gated (Franklin v. School Board of Giles County, —— F.

26 See the comprehensive statistics published by the Southern

Education Reporting Service in its periodic “Statistical Summary

of School Segregation—Desegregation in the Southern and Border

States,” 14th Revision, November 1964, passim.

31

Supp.----- , W. D. Va., Civ. No. 64-C-73-R, June 3, 1965).

Cases involving Negro teacher discharges coincident with

desegregation are pending in district courts in North Caro

lina, Texas and Oklahoma.

The public importance of the issue is illuminated perhaps

by consideration of some societal factors involved. It is

estimated that there are 419,199 white teachers and 116,028

Negro teachers in 11 southern states, 6 border states (ex

cluding Maryland) and the District of Columbia.27 In 1963-

64, Virginia public schools employed 31,443 white teachers

and 9,051 Negro teachers.28 There were 733,524 white pupils

and 34,176 Negro pupils (total 967,700).29 Of 128 districts

with Negro and white pupils, 81 districts had at least one

Negro pupil in school with whites in November 1964, but

only five of those districts had Negroes teaching in school

with whites.30 There was no faculty desegregation in Ala

bama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Caro

lina.31 One North Carolina district, 2 Florida districts, and

7 Tennessee districts had some faculty desegregation, and

one Arkansas district had a Negro supervisor of elementary

schools but no Negro teachers in desegregated classes.32

27 Southern Education Reporting Service, Statistical Summary

of School Segregation-Desegregation (cited supra, note 12) (Nov.

1964), p. 2.

28 Id. at 59.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid. The summary reports: “Some Negro teachers are teach

ing in schools with whites in Alexandria and Roanoke, and in

Arlington and Fairfax Counties. In Prince Edward County, nine

of the 68 teachers in the county’s one high school and three ele

mentary schools are white.”

31 Id. at 2.

32 Id. at 8,15, 39, 50.

32

There has been a prolonged national shortage of teachers

and the supply of new teachers does not meet the demand.33

This pattern holds true in Virginia.34 The N. E. A. Re

search Division conservatively estimates the national

teacher turnover rate at 8.5 percent of teachers withdraw

ing from teaching annually.35

Within the Negro community Negro teachers generally

are recognized as having a leadership role with a compara

tively high economic position,36 but their potential as

leaders in efforts to promote desegregation of public facili

ties and schools is limited by the vulnerability of their posi

tion as employees of segregationist state agencies.37 Con

tinued faculty segregation, posing the danger of discharge

38 Research Division—National Education Association, Teacher

Supply and Demand in Public Schools, 1965 (Research Report

1965-R10, June 1965), passim.

34 Id. at 57.

35 Id. at 29.

36 According to the 1960 census the median income for the non-

white family was $3,662, but the median for the non-white family

whose head was employed as an elementary or secondary teacher

was $6,409 (1960 Census of Population, Vol. I, “Characteristics

of the Population,” Part I, U. S. Summary, Table 230, pp. 1-611).

37 Lamanna, Richard A., “The Negro Teacher and Desegrega

tion”, Sociological Inquiry, Vol. 35, No. 1, Winter 1965. Alabama

has enacted 7 laws to permit firing of teachers who advocate de

segregation (1956 1st Sp. Sess., Acts 40, 41; 1957 Sess., Act 239,

361; 1961 Sp. Sess., Acts 249, 383, 443). Arkansas laws prohibited

NAACP members from holding public employment and required

teachers to list organization membership until Shelton v. Tucker,

364 U. S. 479. A series of Louisiana laws provided for dismissal

of public employees advocating integration (La. Acts 1956, Acts

248, 249, 250, 252). Until challenged in court South Carolina

barred public employment of NAACP members (S. C. Acts 1956,

Act 741), repealed by Act 223 of 1957. See Bryan v. Austin, 148

F. Supp. 563 (E. D. S. C. 1957), judgment vacated 354 U. S.

933.

33

of Negro teachers as Negro pupils go to white schools

where no Negro teachers are assigned threatens potentially

disastrous social consequences for one of the most impor

tant social and economic groups in Negro communities in

the South.

Petitioners submit that faculty segregation per se vio

lates the constitutional rights of Negro pupils because of

its inevitable tendency to impede desegregation of pupils.

In recognition of this the United States Commissioner of

Education, implementing Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964,38 has announced the following ruling to all school

districts submitting plans for desegregation in order to

qualify for federal financial aid (General Policy Statement,

supra, Part V. B .):

1. Faculty and staff desegregation. All desegrega

tion plans shall provide for the desegregation of fac

ulty and staff in accordance with the following require

ments :

a. Initial assignments. The race, color, or national

origin of pupils shall not be a factor in the assignment

to a particular school or class within a school of

teachers, administrators or other employees who serve

pupils.

b. Segregation resulting from prior discriminatory

assignments. Steps shall also be taken toward the

elimination of segregation of teaching and staff person

nel in the school resulting from prior assignments

based on race, color, or national origin (see also, V. E.

4(b)).

38 42 U. S. C. A. §2()00d.

34

The General Policy Statement also indicates that it will

not accept an “Assurance of Compliance” (HEW Form

441) from any school system in which “teachers or other

staff who serve pupils remain segregated.” We submit that

the determination by the United States Commissioner of

Education that faculty desegregation must be included in

order for a desegregation plan to be “adequate to accom

plish the purposes of the Civil Rights Act” is entitled to

substantial weight. But beyond that the Commissioner’s

determination implements the clear intent of the Congres

sional proponents of Title VI. See Vice President (then

Senator) Humphrey’s interpretation of Title VI quoted

supra, pp. 17-18.

The Fourth Circuit has not indicated that there is any

justification for the policy of assigning teachers on the

basis of the race of the pupils, and the school authorities

have not suggested any. Nor have the school authorities

made any effort to establish that there are administrative

obstacles to faculty desegregation justifying delay under

the doctrine of the second Brown decision (349 U. S. at

300-01).

A policy of assigning teachers to schools on the basis of

the race of the pupils is plainly invidious even without

regard to its effect on what schools various pupils attend.

Pupils admitted to public schools are entitled to be treated

alike without racial differentiations in those schools.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637. The

student’s relationship with teachers is central to the edu

cational experience in public schools. When a state decrees

that those Negro pupils in all-Negro schools be taught only

by Negro teachers and that those Negro pupils in schools

35

with white children be taught only by white teachers, it

significantly perpetuates the segregation of Negro Ameri

cans in their educational experience. This is contrary to

the egalitarian principle of the Fourteenth Amendment and

the teaching of Brown that segregated education is “in

herently unequal.”

The issues presented by the “freedom of choice” plans

and the faculty segregation issue merge into a common

problem of vital importance to the implementation of the

Brown decision, and are worthy of the attention of this

Court.

CONCLUSION

W h e re fo re , f o r th e fo re g o in g rea so n s it is re sp e c t

fu lly su b m itte d th a t th e p e ti t io n f o r c e r t io ra r i sh o u ld be

granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J am es M . N a b eit , III

101 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

S. W. T u c k er

H en r y L. M a r sh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

A P P E N D I X

A P PE N D IX

M e m o ra n d u m o f th e C o u rt

[July 25, 1962]

Eleven Negro students, their parents and guardians in

stituted this action to require the defendants to transfer the

students from Negro public schools to white public schools.

The plaintiffs also pray, on behalf of all persons similarly

situated, that the defendants be enjoined from operating

racially segregated schools and that the defendants be

required to submit to the Court a plan of desegregation.

The Pupil Placement Board answered, admitting that the

plaintiffs had complied with its regulations for transfer

and denying the other allegations of the complaint. The

City School Board and the Superintendent of Schools an

swered and moved to dismiss on the ground that sole

responsibility for the placement of pupils rested with the

Pupil Placement Board pursuant to the Pupil Placement

Act of Virginia, Sections 22-232.1 through 232.17 of the

Code of Virginia, as amended.

The defendants interpreted the bill of complaint as at

tacking the constitutionality of the Pupil Placement Act

and moved to dismiss on the ground that its constitution

ality should first be determined by the Supreme Court of

Appeals of Virginia, or the case should be heard by a dis

trict court of three judges.

The evidence disclosed that the City of Eichmond is

divided into a number of geographically defined attendance

areas for both white and Negro schools. These areas were

established by the School Board prior to 1954 and have not

2a

Memorandum of the Court

been changed in a material way since that time. Several

areas for white and Negro schools overlap. The Pupil

Placement Board enrolls and transfers all students. Neither

the Richmond School Board nor the Superintendent makes

recommendations to the Pupil Placement Board.

During the 1961-1962 school term, thirty-seven Negro

students were assigned to white schools. For the 1962-1963

school term, ninety additional students have been assigned.

At the start of the 1962-1963 school term all of the white

high schools will have Negro students in attendance. Negro