Knopf Draft of Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus by a Person in State Custody 7

Working File

January 1, 1983 - January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Knopf Draft of Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus by a Person in State Custody 7, 1983. 6e75557a-ee92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c1a3996-a65d-4fe6-9c59-cc272a5c16a2/knopf-draft-of-petition-for-a-writ-of-habeas-corpus-by-a-person-in-state-custody-7. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

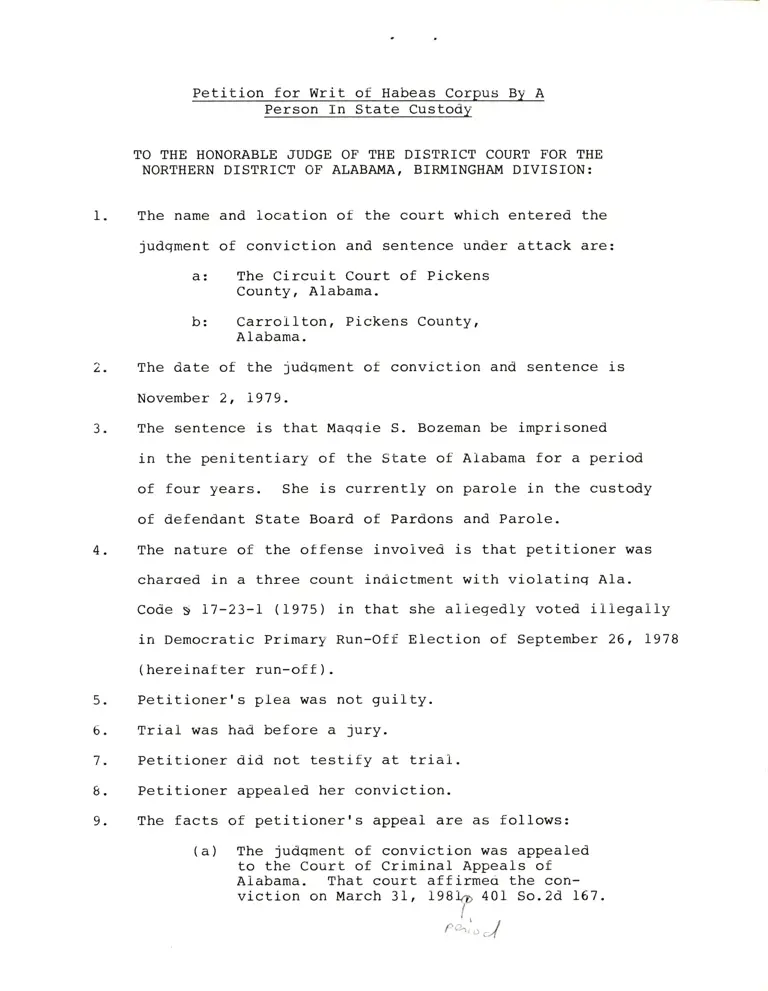

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus By A

Person In State Custody

TO THE HONORABLE JUDGE OF THE DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, BIRII'IINGHAI{ DIVISION:

1. The name and location of the court which entered the

judgment of conviction and sentence under attack are:

a: The Circuit Court of Pickens

County, Alabama.

b: Carrotlton, Pickens Countyr

Alabama.

2. The date of the judoment of conviction and sentence is

November 2, L979.

3. The sentence is that Maqgie S. Bozeman be imprisoned

in the penitentiary of the State of Alabama for a period

of four years. She is currently on parole in the custody

of defendant State Board of Pardons and Parole.

4. The nature of the offense invoiveo is that petitioner was

charqed in a three count inoictment with violatinq AIa.

Code s L7-23-L (1975) in that she aliegedly voted illegally

in Democratic Primary Run-Off Election of September 26, 1978

( hereinafter run-off ) .

5. Petitioner's plea was not guilty.

6. Trial was had before a jury.

7. Petitioner did not testify at triaI.

8. Petitioner appealed her conviction.

9. The facts of petitioner's appeal are as follows:

(a) The judgment of conviction was appealed

to the Court of Criminal Appeals of

Alabama. That court affirmeo the con-

viction on ltlarch 31, 198io 40f So.2d L67.

r..',^' r.,a, .. ,r{

. {1.

(.u'r

(l) Gfr. Court of Criminal Appeals of

Arabama oenied a motion for rehearing

on the appear on APriL 2L, 198I. Io.

(c) The Supreme Court of Alabama denieo a

petition for writ of certiorari to the

Court of Criminal Appeais on July 24,

1981. 401 So.2d L7L.

(d) The Supreme Court of the Uniteo States

<lenieo a petition for writ of certiorari

to the Court of Criminal APPeaIs on

November i6, 1981. 454 U.S. 1058.

10. Other than the appeal-s describeO in paragraphs 8 and 9

above., the other petitions, dPPlications, motions, or

proceeciings filed or maintained by petitioner with

respect to the juoCment of November 2, L979 of Circuit

court of Pickens county are described in paragraph II

beIow.

Ii.

L2.

(") t"*:i:"8i::lit 8:x.i'l?'nl3i"[3u'

County. The motion was denied on

February 27, L979.

Petitioner was convicted in violation of her rights

guaranteed by the F'irst, Fifth, Sixth anci Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States, fot

each of the reasons stated below.

I. Introductory I'acts

13. Petitioner Maqgie S. Bozeman was convicted of

illeqai votins because of her aliegeO participation in an

effort Lo assist eioeriy and iliiterate voters to cast absentee

baliots in the run-off.

2-

.-,#

-..--^

r4. >-Shortly af ter the run-off eiection,rl@n October 'r0,

Rh

Lglg,6" sh";i;; "i pl.L.n" Eo[nty, r,,rr.

"o

-'fi4-r-:^*'^-.*"#t

\2

alonq with the Dislrict Attorney of the County, Mr. Pep

Johnston, an investigator nameci Mr. Charlie Tate, and lvlr.

Johnston's secretary, Ms. Kitty Coope5 opened the county

absentee ballot box to investigate "assumed voting irregularity. "

Tr. 35. They isoiated thirty-nine absentee ballots out

of the many cast. What oistinguished these absentee ballots

from the many others cast in the run-off was that they were

notarized by Mr. Paul Rollins, a black notary public from

Tuscaloosa. Tr.36.

15. Each of the 39 absentee ballots was representeo

to be the vote of a dirferent brack, elderiy, and infirmed

resident of Pickens County. The state claimed that Ms.

Bozeman participated in the casting of these ballots in

vioiation of AIa. Code S L7-23-L (1975).

II. Grounds of Constitutionai Invalidity

A. Insufficiency of th n',i,>^'"'0

;j\

16. Based on the evidence offered at trial no Lational

jury could have found petitioner guilty beyono a reasonabie

doubt ot each of the elements of the offense charged, and

therefore petitioner's conviction violated the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

3-

Facts sup'portinq the claim that

the evidence was constitutionaliy

ion.

L7. Under Jackson v. Virsinia, 443 U.S. 307 (i979),

petitioner must be granted a writ of habeas corpus, if after

. d- +r," I

consioerinq the evidence offered by the st:-q-and viewing

it tl in the iiqht most favorable to the state, it is concluded

that no rational jury coulo have convicted petitioner beyond

a reasonable ooubt of each of the elements of the offense

charged.

18. Petitioner was charged with violating Aia. Code

S L7-23-t (1975) because of her aileged activities in connection

Pa"' 'J'twith the run-off" Section L7-23-L provides:

Any person who votes more than once at

any election held in this stater oE deposits

more than one baliot for the same office as

his vote at such electionr or knowingly

attempts to vote when he is not entitled to

do sor or is guilty of any kind of iliegal

or frauduient voting, mustr on conviction,

be imprisoneo in the penitentiary for not

less than two nor more than five years, dt

the oiscretion of the lury.

19. The Supreme Court of Alabama defined the elements

of S L7-23-L

.o..I"en-I,

a century aso. In Wiison v. State , 52

Aia. 2gg (1875f it heia that "Itjhe offense denounced by

the statute . is voting more than once. " The Court,

in Gorcron v. State , 52 AIa. 308 ( 1875 ) , held that in order

to establish cuipability uncier the statute "wrongful intent"

fx-.9'l-

on the part of petitioner would*arre.to be proven which,

a

at minimum, -wtrrrid requird proof that the accused acted

"recklessly or carelessiy" in vioiating the statute. 52

Ala. at 309-310. But in Wilson the Court held that the

4-

minimum showing of wrongfur intent must incrude proof of

fraud if the manner in which the state investigation 4r.t..raj

conoucted resuLd tr', .n inspection of the contents of the

bailot box. 52 Ata. at 303. Therefore, since an inspection

of the baiiot box was made, (Tr. 35) the elements of the

offense charqed against petitioner are that she voted more

than once throuqh fraud.

,ft20. Each count of the indictment averred ttD6petitioner

vioiated S L7-23-L by castins or depositing ballots. But

there was no evidence presented that petitioner ever oeposited

or cast any ballots, absentee or regular, in the run-off.

There was no evicience as to whether she voteo at ail in

the run-off.

2L. At most, petitioner could have been convicted,

on the evidence presented, as an accomplice. In order to

sustain accomprice iiabirity against the petitioner, however,

the prosecution must tirst have proven that the underiying

offense, S t7-23-L, was committed. Second, it must have

presented evidence that petitioner rendered some sort of

assistance toward the commission of the crime. E1 parte

Ritter, 375 So.2d 27A, 274 (ala. L975). Thiro, evidence

must have been presented that this assistance rendereo by

petitioner was "intended and carculated to incite or encourage,

throuqh the use of fraud, those she was allegediy aiding

to vote more than once. Baker v. State , 290 So. Zd 2L4,

zLG (Ala. Crim. App. t973), cert. den., 290 So.2d ZL7 (ata.

L974). Fourth, 1t must have been shown that petitioner

5

knew those she was aiding were acting with the

defraud. Keller v. State, 389 So.2ci 926, 936

intent to

( aia. Crim.

petitioner

make her

293 So.2d

App. L976).

at the "scene

an accomplice

L976) .

22.

It is clear that mere presence of

of the crime" is insutficient to

to the crime. Radken v. State,

314, 316 (a1a. L974)i Wiison v. State, L22 So. 617 (Ala.

1929)i HoweIl v. State,339 So.2d 138, 139 (Ala. Crim. App.

rn its entire case, the ffi$evidence against

petitioner consisted of only three instances Iinking petitioner

to any activity in the run-off, and no evidence at all was

presented that petitioner's actions were either criminally

culpable or in violation of S L7-23-1, as principal or accomplice.

First, the prosecution evidence showed that petitioner

picked up "Ia]pproximately 25 to 30 applications" for absentee

baliots from the county clerk's office during the week preceding

the run-off. Tr. i8. Second, there was evidence presented

that petitioner aided Mrs. Lou Sommerville in filling out

an application for an absentee barlot. Tr. 16l, 169. This

evidence from Mrs. Sommervilie was inconsistent with the

( d,$^s'

directFe examination 6 testimony of the witnessjand was

presented by the State in violation of petitioner's rights

under the U.S. Constitution, see paragraph , infra.,Tle 3.,,Jr,-cC jlr',r,,.

f.,- ..-.lt,1.Jr.- ,rl,' t -..r.' ;''la;3 -'- , ->-e4- .;tJ!l ." " " "'-ril';irr-JEheTros-eE6-to.'rea&d[o the jury notes, not previousry

shown to defense counset, of an interview conducted without

defense counsel or any other counsel present one year prior

to trial. Mrs. Sommerville, testifyinq on the stand, vehemently

6-

denied the veracity of the prsecutorrs notes and denied any

invorvement whatsoever by petitioner. Ici. Third, there was

evidence presented that petitioner may have been present when

some absentee ballots were notarized by Mr. PauI Roliins. !/

23. Even in the light most favorable to the State, the

testimony of the county cierk that petitioner picked up 25-30

baliot applications and the prosecution notes of an interview

with Lou Sommerviile suggesting petitioner assisted Ms.

Sommerviile in filling out an application for an absentee

ballot do not point to any criminal cuipability of

petitioner. Even taken as true and not contradicted by the

witness' testimony on direct examination by the State, this

evidence at most links petitioner to legitimate voter assis-

tance in the application process and suggests nothing at all

about petitioner's activity, criminai or otherwise, in de-

positing, casting ;5 voting actual ballots knowing them to be

fraudulent. Without question the testimony of Mr. Roilins

L;P./ ($f,ere were two other mentions made of petitioner in

the e-vidence oftered by the state but neither hao to do

with the run-off. F'irst, Mrs. Sophia Spann testifieo that

petitioner had talkeo with her about absentee voting wheni'it wasn' t voting time. " Tr. 164. Secono, according to

the prosecutorrs notes of the out of court statement, peti-

tioner aided l,lrs. Sommervitle to f if l out an absentee ballot

to be cast in the regular primary helo in early September

of L978. Tr. L74. Mrs. Sommerviller orr the stand, stead-

fastly denieo any invoivement by petitioner. Id.

7-

represents the only evicience of even the most attenuated

connection beiween petitioner and the 39 ballots allegedly

voted in violation of S i7-23-i. Without the testimony

of Mr. Rollins there is "no evidence" to convict petitioner.

Thompson v. Louisville, 369 U.S. I99 (1960). with the

testimony of Mr. Roliins the state's case stiil fails under

the Jackson standard-

24. It is clear that mere presence during' the notari-

zinq of the ballots couid not constitute any evidence of

culpabiiity under S L7-23-L. Notarizins, dt the time of

the run-off, was requireo by taw. A1a. Code S 17-10-6 (1975)

(repealeci Acts 1960, No. 80-732, p. 1478, S 3).

25. Furthermore, in view of the lack of any other

evidence against petitioner, in order to sustain her con-

viction her role in the notarizing must, standing aIone,

provide sufficient evioence of each of the elements of accom-

plice liabirity (see para.2L, above) so as to prove petitioner's

quilt under the Jackson standard. Proof beyond a reasonable

(-,_t,a S

doubt oi each of these etements was required by the @ue

n. C-

Qro..== Garse of the Fourteenth dmenoments. rn Re Winship,

397 U. S. 358 ( r970 ) .

26. The oniy possibie theory of criminaiity arising

from the notarizins is that the notarizing took place outside

of the presence of the voters. It is admitted that the

evidence showed that petitioner teiephoneci ltlr. Rollins ano

ieft a messaqe prior to the run-off. Tr. 65-66. But l4r.

RolIins also gave uncontroverted testimony that after petitioner

telephoned he received another telephone call, also pertaining

to bailots, from a second person whose name he coulo not

recali. Tr. 76. There was simply no evidence offered beyond

that related above so that it is impossible to know which

of the carlers arranged that the notarizing woulo take piace

out of the presence of the voters. The state offered no

eviclence on this point lyino at the crux of its case.

28. The evioence also showed that petitioner was

present at the notarizing along with three or four other

women. Tr. 57. But IvIr. Rollins denied that petitioner

personaliy requested him to notarize the ballots. Tr. 59,

60, 62, 64. A11 the state couid eiicit from Mr. Rollins

was that petitioner was present at the notarizing anci that

she and the other women were there "together. " Tr. 60-61,

lt'.t ll

62, 64, 7L. No evicience was presented by theustate to con-

tradict Mr. Rollins' unequivocal and responsive answers

oenyino actual involvement by petitioner or professing lack

of memory.

29. In sum, the evicience of f ered by the state can

provioe only "conjecture and suspicionr " United States v.

Fitzharris, 633 F.2o 4'16, 423 ( 5th Cir. I950 ) ( applying

Jackson), as to whether petitioner aided in causing the

notarizinq to take place outsioe of the presence of the

voters, and as such the evioence is insufficient unoer

See Fitzharris, supra.

30. However, even if it is assumed arguendo that

Jackson.

the state's evidence was sufficient to convince a reasonable

jury beyond a reasonable doubt that petitioner aided in

causing the notarization to occur out of the presence of

the voters, such proof stil1 fails to provide sufficient

9-

ft->

Sr r.1r( T

f r; ".'Tct't", r,1-

,- --- ir (

evidence under Jackson of the mental culpabiiity required

for accomprice liabirity under S 17-23-'1. Applicable here

is the requirement of Jackson that the habeas court "draw

reasonable inferences from basic facts to ultimate facts. "

443 U.S. at 3I9. Therefore, the relevant question is whether

from the fact, assumed herein, that petitioner aioeo in

causinq the notarizing to take place outside of the presence

of the voters, it can be reasonably inferrea that petitioner

was actinq with intent to aio in what she knew to be an

effort to deprive others of their votes through fraud.

The eleventh circuit held recently that the process of in-

ferring uitimate facts from evidentiary facts reaches a

degree of attenuation which falls short of the Jackson rule

"at least when the undisputed facts give equal support to

inconsistent inferences." Cosbv v. Jones, 682 F.2d L373,

!:SPcrtP

^.i383 h' 2L ( ittLlT,;"*3311; ,,lli,l.,llr"^ g:,"=tion is whether

rhe runoisputeci t""!ffnit patltfrnEl-piayea a supportino

role in causing the notarizing to take place outside of

the presence of the voters makes it more iikely than not

that she was actins with the calculated intent to aid others

to commit frauo for the purpose of voting more than once.

It is submitted that a reasonabie trier of fact would perforce

harbor at least a sinqle reasonable doubt as to whether

that {undisputed factl proved petitioner's cuipability.

B. Insutfiency of the Indictment

3I. The inoictment brought aqainst petitioner was

i0

insufficient to inform petitioner of the nature and cause

of the accusatiorr asainst herr &s required under the Sixth

and Fourteenth Amendments.

Facts supporting the claim

that the inloictment taired

onaIE

sufficient notice.

32. The inoictment taii-ed in at leasc three respects

to measure up to the standaro of constitutionally required

notice:

i) It taileo to state ai-l of the

established elements ot tiability

under S 17-23-L.

ii) It faiied to aiiege facts

sufficient. to inform petitioner of

the nature of the accusation

against her.

.,

iii) rtifailed to charse certain

offense{distinct trom 5 L7-23-L

which were charged to the jury as

eiements ot 5 L7-23-L.

33. It is a long established rule that every er-ement

of the offense charqeci must be accurately set forth in the

inoictment. See, e.q., RusselI v. United States, 369 U.S.

749t 763-764 (t962l.. Russell aftirmed that this rule is

one of a number of "basic principles of fundamental fairness,"

(369 U.S. at 765-766), pertainino to the indictment which

7 find constitutional embodi,{ment in the Notice Clause of

the Sixth Amendment. _Is-'-, at 76L. That the indictment

fairiy intorm the accused of what she must be prepared to

meet is "the t'irst essential criterron by which the suffiency

of an inoictment is to be tested. " Id. , at 764 And the

"inciusion of the essential erements of an offense in an

inciictment Iis] . the bare minimum of information necessary

11

to

v.

meet" the Sixth Amendment Notice Clause.

Outler, 659 F.2d i306, 1310 (5th Cir. Unit

United States

<;

!'<' LC

rraud*vas

B 1981), cert.

den. , L02 S.Ct. 1453 (1982).

34. There are two essentiai eiements to S t7-23-I,

(see para. 19, above). First, the accused must have voted

more than once. Second, the accused must have done so,

in a case like petitioner's where inspection of the contents

of the ballot box was had, throuqh fraud.

5' C r'( (:-<>

35. The intent element*Jthe requirement of

omitted from both .ount?6#e ara "orntnfi*J oa the indictment.

Both counts are therefore fatally defective under the Sixth

Amendment. Petitioner was convicted of all three counts

in the indictment.

36. the failure of count one and count two to state

the intent element of the oftense caused the indictment

as a whole to be insufficient unoer the Notice Clause.

The inoictment'SiB the same "rr"filthat petitioner vio-

lated S L7-23-l by her voting activities in the run-off

(11c-..A

-,hn each of its three counts. By doing sor the indictment

presenteo petitioner with three aiternative statements of

the offense charged against her, with conviction under any

one of the three sufficient to subject her to the fuII penal-

ties of S L7-23-L. Therefore count three, even thouqh it

states the intent element of S L7-23-1, cannot correct the

inaccurate and insufficient notice caused by the first two

counts. Count three notwithstanding, the indictment read

as a whole informeo petitioner that she could be convicted

L2

under S L7-23-1 without any showinq of mental culpability.

The crucial intent element of S t7-23-i was not accurately

alleqed and caused the indictment as a whole to fail to

impart the minimum notice required by the constitution.

37. An indictment, in order to provide constitutionally

sufficient notice, must do even more than state the elements

of the offense. It must "identify the subject under inquiry.,'

Russell v. United States , 369 U. S. 749, 766 (L962) . It

must inform "the defendant . of which transaction, or

facts, give rise to the allegeo offense." U.S. v. Outler,

659 F.2d 1306, 13I0, n. 5. (5th Cir. Unit B 1981), cert.

den. , 102 S.Ct. 1453 ( 1982). This rule assumes crucial

importance.

?tr/1l i4^

"where the def inition of an of fense, (-;)f

whether it be at common law or by ./-statute, 'includes generic tedfol/ \c

i. In such a casej, it is not sutfi-

cient that the indictment sha1l charge

the offense in the same general terms

as in the definition; but it must state

the species it must descenQ to the

Particulars. "' td

Uniteo States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542, 558 (1875).

The Cruikshank ruie was incluoed in Russell as one

of the "basic principies of tundamental fairnessr " ( 369

U. S. at 765-766) , to which indictments must adhere. The

very holdinq in Russell rested on this rule and on the necessity

of the indictment to give notice as to those factual allegaions

which 1ie at the "core of criminalityr" (Id., at 764), of

the particuiar statute.

38. Petitioner was chargeri in the disjunctive in

each count of the indictment with riilegal' or 'fraudulent,

votinq. That illeqal is such a "generic term" is plain , - r- t'n/t\t)

i3

specuiating that the castinq of the absentee ballots by

someone other than petitioner constituteci the consumation

of a criminal scheme in which petitioner participated without

necessarily knowing or intending that a crime take place.

40. The activities of several women other than this

petitioner in the weeks prior to the run-off were "the very

core of criminality," (Russeil, sllPE, 369 U.S. at 764'),

under S L7-23-L. Under Russell the state was required to

iliiminate thiJ core by "descendIinA] to the particulars, "

(Ig., at 765), and identifyinq the facts and transactions

which made what would have otherwise been the lawful depositing

of absentee ballots an alleqed felony. Since the indictment

tailed to do so, petitioner was forced to guess at her peril

amonq the many activities she might have participated in

durinq the weeks before the run-off as to which would be

seized on by the state as the basis for proving her culpability

under S L7-23-L. Since the indictment alleged that criminal

liability could be established on strict liability grounds

her suess was made all the more difficult and perilous,

and the absence of pertinent factual allegation was maOe

aii the more criticai. See Van Liew v. United States, 32'L

F.2d 664, 674 (5th Cir. 1963). The inoictment's lack of

factual averements caused it to fail to provide the quantum

of notice required by the constitution.

41. It is clear that each and every statute which

is to be used by the state as a possible partial or total

basis for criminal liabiiity must be alleged in the indictment.

15

First, each such statute is an element of the offense against

the accused. Second, it is assuredly a necessary factual

averement if sufficient notice is to be given. Goodloe

v. Parratt, 605 F.2a 1041, L045-1046 (8th Cir. L979). Third,

it is axiomatic that "Ic]onviction upon a charqe not made

would be a sheer oeniai of due process. " De Jonge v. 9regon,

299 u. S. 353, 3b2 ( 1937 ) .

42. Petitioner was subjected to a denial of constitu-

tionally required notice and due process by virtue of charges

Ievied against her for the first time in the trial judge's

instructions to the jury.

43. The jury was first instructed to the effect that

liability under S L7-23-L coulci be sustained if petitioner

had committeo "an act that is not authorized by law or is

contrary to law." Tr. 20L. That was the oefinition of

"i1leqal" given to the jury, and the instructions permitted

any such "iI1egaI" act committed by petitioner in connection

with her votins activities in they'un-off to sustain a lia-

I

bility under S L7-23-L. Id. '

44. The triai judqe then instructed the jury on three

.vA,c A t

statutes, AIa. code. S l7-io-6 (197ffi "Wted by the

judoe as S L7-L0-7, (Tr. 202-203) , Ala. Code S 17-10-7 (L975)/

(tr. 203-204), and Ala. Code S I3-5-I15 (1975), (tr. 204),

each of which was chargeo against petitioner for the first

time in the instructions.

l6

basis for liability on the part of the accused. The result

is nothinq less than a wholesale deprivation of consti-

tutionally required notice. see, €.9. r watson v. Jingo,

558 F.2d 330, 339 (6th Cir. L977). Such a wholesale depri-

vation was unquestionably visited upon petitioner by the

* instructions given to th{-jury, and the failure of the indict-

I

ment to conform in any way to the proof at trial.

c.

48. The instructions to the jury on liabiiity under

S L7-23'I and S 13-5-1i5 broadened the reach of those statutes

to a deqree that represented an unforeseeabie and retroactive

judicial expansion of the reach of those statutes in violation

of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Also, the fact that both statutes were defined as strict

liability offenses denied petitioner I due process irrespec-

.fu"t o(-

tive of th-e-t6*-pansion of io.ns-

Facts supporting the claim that

the iury instructions on S L7-

23-i and S 13-5-I15 violated

due process.

In the case of Bouie v. City of Columbia, 378

U. S. 347 (1963) , the Cour LraVpti$l tf,e requirement of due

process that a statute give fair warning of the acts forbiooen

by it, to hold that an unforseeabie expansion of a criminal

statute by a court in instructinq the jury as to the law

Oenieo the defendant due process of law. Id., at 354-355.

Such an unconstitutional expansion occurreci in the present

case.

50. The actions prohibited by S L7-23-L had been

ciearly deliniated as voting more than once. It had also

49.

TriaI Courtrs Instructions on the Elements of Culpabilit

18

been lonq established that some sort of wrongful intent

had to be shown in order to convict unoer S L7-23-L. (See

para. 19, above) fhe instructions broadened S L7-23-L to

reach any action "not authorizeo by raw or . contrary

to the law." Tr. 20L. Under this new standarci the failure

to meet the requirements of any raw while in the course

of voting activities is sufficient qrounds for criminal

liability under S I7-23-t even if the accused was actins

in qood faith. Two non-penal statutes (SS 17-10-6, L7-LO-7)

and a penal statute (S 13-5-1f5) were also charged against

petitioner, (See paras. 44-46, above), under this new theory

ot culpabirity.

5r. Section 13-5-r15 was aiso impermrssrbly expancted.

The statute as written requires that the accused act "corruptly"

(r.e. with criminal intent) before liabriity can attack.

The instructions oefineo S r3-5-115 as a strict Iiability

offense. Tr. 204.

52. Both S L7-23-l and S 13-5-iI5 were presented

to the jury as strict Iiability offenses. Thereforer os

applieo in the instructions they cienred petitioner ciue process

irrespective ot the impermissibie expansion of their reach.

D. Vioiation of Petitionerrs First Amendment Rights

53. The only conouct by petitioner proved beyond

a reasonable doubt by the State's evidence amounted to behavior

protected under the First Amenoment to the Constitution,

and theretore her conviction violated both the First ano

I'ourteenth Amenciments .

19

Facts supportinc claim that state

proved onIY constltutionailY

petitioner.

55. Petitioner's participation in an organization

workinq to brinq out the black vote among the elderly in Pickens

County is

20

C (ecr^ \ c\ putrt, r^-Q acltu,tl p.^ ute ,f nn) ltv J 4 tI.,

r-a^JGIitGr'.-, TA. ttf^sTAvnt,uJ

n^ e v-f fr..Jrn^. to

Xoft^.e.- in orrsoc,.^t,or.' -Fr- ile pr,.npote af,,.d.rc,.r.'c,.11

gl-o.r-cJ Le(,t(S ts g,.,oter:to ol b\ tI-, 6rr.r.1n"-tL AueN

& -.^. inG' ui€r+.. -t t1 ^r1 St^te .'., l)e^o cn,.-t,- Po-

t.

-!e * W"rL^st*.,11 EO U.S, t0) 2 ltt

-)h. s f^te p^.ovg J ho-hl'-

t lr.'ore. fl,,.p

I -t-

dfi^,?M I

(/r a r)

J^,VCltv r

go1-,-1, ^?& p & c-.. r) u oi Jn yr,',, u pe 4,fi uuen o( Lr". /, to^-r- LrM"l

h C*-l- Fr\

t

l^,,h u.{use 4x,,r -Jr e ,. uu,.T ...

,J f , c.^ n c,- 1,,'lr;1 o ( #\ [qu b, ,r-, corl/ ^n *b

l^..,', , p"htta>^.c.r ln r-1kt Lr<

lou< ,

.1-

fa fl.. e- J trJ rh e )

bu1 be lr-A^:,*J l":)'# uN c a,.r t,*uft u.,-( ,"sh o ,;t,

W L) fud n.t a L,eo 7 p7 .af ,.^'kt oL ,-,1,.^ne lt o d'

F*:" (. r.^1 Le b({aeJ Cuxce rPtNT L, olteynl-cao ,( +L."

petila cln

r,

'3)'l)nn* . J' p o- t, /-' au.ez, u- l-r,-, t u, J,,r e^r-l / t(,

?.^oCetd,.-, i(rrf

-f

*.,y.e,JT ,,€ r rr/l ar fol ,'\ v"- -r,)

e ,-?.ruT'surL ,,fLt< ttel"r"(; ,,

^,r7" /," .,/f-^,/?( r,,rc.(

"" (,

?. t., t, s. ^ ?n" .1 J

Rur, o .:tf, I [, -fub ),h; t'TeJ r