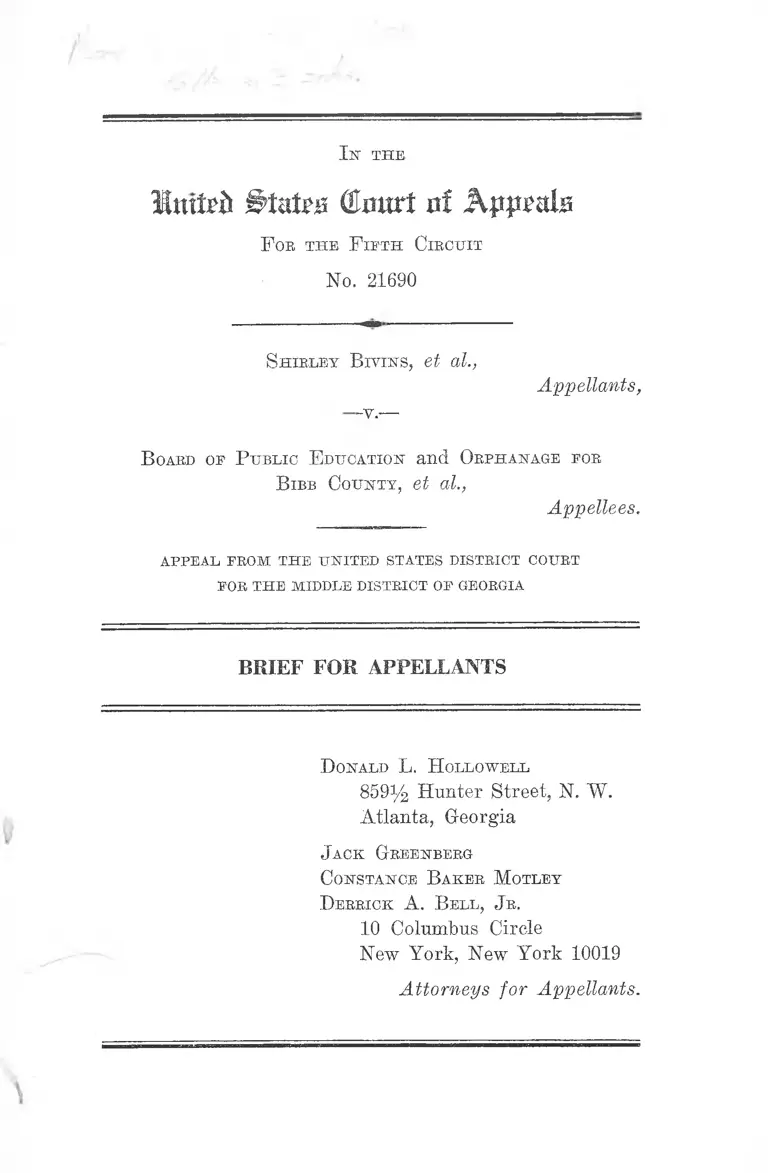

Bivins v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb County Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bivins v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb County Brief for Appellants, 1964. 6d2fa6e6-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c2772d5-4924-472e-898f-99ccd6c9aa42/bivins-v-board-of-public-education-and-orphanage-for-bibb-county-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

I n - t h e ,

Mnxttb U tata Cmtrt of Kppmhx

F oe t h e F if t h C ir c u it

No. 21690

S h ir l e y B iv in s , et al.,

-v.—

Appellants,

B oard of P u b l ic E du ca tio n a n d O r ph a n a g e for

B ibb C o u n t y , et al.,

Appellees.

A P P E A L FR O M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IS T R IC T COU RT

FO R T H E M ID D L E D IS T R IC T O F GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

D onald L. H ollow ell

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

J ack G reen berg

C o n sta n ce B a k e r M otley

D e r r ic k A. B e l l , J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants.

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case .............. .................. ............. . 1

Pre-Litigation Pleas and Petitions ................. . 2

Description of Board’s Plan ............... ............... 4

Appellants’ Objections and Interim Plan ...... . 5

Board Defense of Its Plan .................... ............ . 6

Approval of Plan by Lower Court ................. . 9

Specifications of Error ........... ..................... ............. . 9

A r g u m e n t :

Appellees’ 20 Year Desegregation Plan Fails to

Meet the Minimal Standards Set by This Court

and Countenance Impermissible Delay________ 10

C o n c l u s io n .......... ................................ ........................ . 18

T able op Cases

Armstrong v. Board of Education of Birmingham, 323

F. 2d 333 (1963), F. 2d M l- (5th Cir., June 18,

1964) ...................... ............ .................................11,15,17

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862

(5th Cir., 1962) .................. ........................... ........ 15

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Va., 321

F. 2d 494, 499 (4th Cir. 1963) ___ ______ ___ ____ 14

Belo v. Randolph County Board of Education, Civ. No.

209-G-63 (M. D. N. C.) 16

ii

PAGE

Bennett v. Madison County Board of Education, Civ.

No. 63-613 (N. D. Ala.) --------- ------- ----- ---------- 17

Boyce v. County Board of Education of Humphreys

County, Tenn. Civ. No. 3130 (N. D. Tenn.) ... .......... 17

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, Va., Civ.

No. 3353 (E. D. Va.) (317 F. 2d 429) (4th Cir.) .... 17

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT. S. 483 (1954) ..2, 5,16

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) .... 10

Brown v. School District No. 20, 226 F. Supp. 819

(E. D. S. C. 1963), aff’d 328 F. 2d 618 (4th Cir.

1964) ................. ...............- .....-................ -............... 16

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491

(5th Cir., 1962) ........................................................ 10,15

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U. S. 2&- (1964) ................. 10,13

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education, Civ.

No. 2072-N (M. D. Ala.) ..........-.............-.......-........ 17

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 TJ. S. 1 ....................................... 15

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 322 F. 2d 356 (1963),-----F. 2d — (5th

Cir., June 18, 1964) ................ -.....- ................. H> 15,17

DuBissette, et al. v. Cabarrus County Board of Educa

tion (M. D. N. C.) ....................-................................ 16

Eaton v. New Hanover County, Civ. No. 1022 (E. D.

N. C.) .....................................-..................................

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960) cert,

denied, 364 H. S. 81 (1961) .......................... -...........

Ford v. Cumberland County Board of Education, No.

668 (E. D. N. C.) .................................................. -

Gaines v. Dougherty County Board of Education, No.

20984 (July 31, 1964) ......................................... -U, 17,18

Ill

PAGE

Gill v. Concord City Board of Education, No. C-223-

S-63 (M. D. N. C.) .................. .................................. 16

Gilmore v. High Point Board of Education (M. D.

N. ('.). No. C-51-G-63 ____ ___________ _____ _ 16

Glynn County Board of Education v. Gibson,-----P. 2d

----- , June 18, 1964 .............. ................................... 16

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

373 U. S. 683 (1963) _________ __ ______ ______ 10

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, 301

F. 2d 164 (6th Cir. 1962) rev’d on other grounds,

373 IT. S. 683 ......... ...................................................10,14

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, No. 3984

(E. D. Tenn.) ...... .................. ................................ 17

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U. S. 218 (1964) _____ _____ ____ 10

Griffith v. Board of Education of Yancey County, Civ.

No. 1881 (W. D. N. C.) ................... ..................... . 16

Hall v. Hon. E. Gordon West, ----- P. 2d ----- (5th

Cir., July 9, 1964) .................................................... 17

Hereford v. Huntsville Board of Education, Civ. No.

63-109 (N. D. Ala.) ............... ..................................... 17

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg, Va., 321

F. 2d 230 (4th Cir., 1963) ........ ..................... ......... 10

Jeffers v. Whitley (Caswell County), 309 F. 2d 621,

629 (4th Cir., 1962) ................................................. 16

Miller v. Board of Education of Gadsden, Ala., Civ.

No. 63-574 (N. D. Ala.) ________ _____ ________ 17

Eippy v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690, 693 (5th Cir. 1957) .... 17

IV

PAGE

Sowers v. Lexington City Board of Education, C-20-

S-64 (M. D. X. C.) _______ ______ ____ ______ 16

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 318 F. 2d 425 (1963), F. 2d (5th Cir.

June 18, 1964) ........... ............................. 11,13,15,17,18

Turner v. Warren County Board of Education, 1482

(E. i). N. C.) ......... .................................... .............. 16

Vick v. County Board of Education of Obion County,

Tenn. (Civ. No. 1259) (W. D. Tenn.) .............. ......... 17

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 ............. 10,11

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, Civ.

No. C-54-D-60 (M. D. N. C.) ................................... 16

Whittenberg v. School District of Greenville County,

S. C., Civ. No. 4396 (W. D. S. C.) ...... ................. 16

Zigler v. Beidsville Board of Education, C-226-G-62

(M. D. N. C.) 16

I n t h e

Htttteb States Gkrurt rtf Appeals

F oe t h e F if t h C ir c u it

No. 21690

S h ir l e y B iv in s , et al.,

Appellants,

B oaed of P u b lic E ducation a n d O eph a n a g e foe

B ibb C o u n ty , et al.,

Appellees.

A P P E A L F E O M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D ISTR IC T COURT

F O E T H E M ID D LE D ISTR IC T OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

Preliminary Statement

This suit was brought by Negro parents of school chil

dren attending the public schools of Macon and Bibb

County, Georgia, after the Board of Public Education and

Orphanage for Bibb County publicly announced that, not

withstanding requests and petitions calling for voluntary

school desegregation, they would not alter their traditional

segregated school system unless such action was ordered

by a federal court. Appellants present here for review a

final order and judgment of the district court approving

a desegregation plan which envisions two decades to com-

2

plete what the Board has already taken a full decade to

begin.

The complaint follows what is by now the classic form,

seeking for plaintiffs and their class a preliminary and

permanent injunction against the Board of Public Educa

tion and Orphanage of Bibb County, Georgia, its members

and its Superintendent of Schools, enjoining them from :

continuing their policy and practice of assigning pupils

by means of a dual scheme of school zone lines based on

race and color; assigning teachers, principals and other

professional school personnel to the Bibb County schools

on the basis of race and color; and approving budgets, poli

cies, curricula and programs designed to maintain or sup

port compulsory racially segregated schools (B. 3-12).

In the alternative, plaintiffs prayed that the Court enter

a decree directing defendants to present a complete plan

for the reorganization of the entire school system of Bibb

County into a unitary nonracial system, within a period

of time to be determined by the Court (B. 11).

P re -L itiga tion P leas a n d P e titio n s

This action culminates a lengthy history of vain efforts

by plaintiffs and others to induce the Bibb County Board

to voluntarily implement Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U. S. 483 (1954).

In December 1954, a petition calling on the Board to de

segregate the schools was submitted by Negro citizens of

Bibb County who offered their services to the Board in the

implementation of a desegregation plan (B. 90-92, 322-23).

While petitioners requested notification of the meeting on

this petition, the Board did not respond. Subsequent public

statements indicated that the request was deemed “pre

mature” by the Board (B. 92, 326).

3

In August 1955, a second petition signed by Negro parents

and citizens (R. 92-93, 324-25) was submitted to the Board

again calling for an end to racially segregated schools in

Bibb County, and quoting the Supreme Court’s admonition

that its decision requires “good faith compliance at the

earliest practicable date” (R. 324). The Board, whose mem

bership includes five lawyers and judges (R. 78) referred

this petition to a special committee headed by Board mem

ber Mallory C. Atkinson (R. 89), a law school professor

(R. 77) and former Superior Court judge (R. 87). The

committee in a “preliminary report” indicated that the

problem would require an inestimable amount of “time,

effort and study, . . . ” (R. 327).

In February 1961, the Macon Council on Human Rela

tions, an interracial group, noting the repeal by the Georgia

Legislature of statutes aimed at frustrating any school

desegregation (R. 329), appealed to the Board to study

the school situation for the purpose of initiating desegrega

tion of the public schools (R. 97, 328). The receipt of this

letter seems to have stimulated the Board to form a new

committee to study the problem (R. 97, 122, 332).

In or about March 1963, a group of Negro citizens, in

cluding some of the appellants, once again petitioned the

Board to desegregate the Bibb County public schools (R.

336-37). As a result, the Board, on April 25, 1963, filed a

petition seeking a declaratory judgment in the Bibb County

Superior Court as to whether the Board had the power to

desegregate the schools in view of their charter from the

State which prescribes the operation of a system of distinct

and separate schools for white and colored children (R. 18).

The Superior Court ruled that the Board has the authority,

under its charter, to operate its schools on a desegregated

basis (R. 23).

4

Nevertheless, on July 30, 1963, the Board adopted a

Resolution stating that- any decision to change the present

segregated operation of the Bibb County Public Schools

must be left to the federal courts, and reaffirming the

Board’s conviction that integration of the races in the

public schools of Bibb County would be detrimental to both

the colored and white races, and the entire county (R. 23-

25).

D escrip tio n o f B o a rd ’s P la n

Plaintiffs filed suit in August 1963, and the Board’s

answer admitted the essential allegations of jurisdiction,

the capacity of plaintiffs to sue in behalf of themselves and

as representatives of the class of minor Negro children

similarly situated, and that the Board had in the past and

presently operates separate schools for white and colored

children in Bibb County (R. 16,17,18, 22).

The district court, following a pre-trial hearing, ordered

the Board to make a prompt and reasonable transition to a

racially non-discriminatory school system and to present

to the court within thirty days a complete plan adopted

by the Board for this purpose (R. 29). The plan was

submitted on February 24, 1964 (R. 30-36).

Under the plan, no immediate change was to be made in

the identification of residential areas or in the identification

of the high school to which pupils graduating from the sev

eral grammar schools are assigned. Except for a transfer

provision, the present policies and procedures of the system

are to be continued with respect to the placement of pupils

entering the system and with respect to the transfer of

pupils within the system. The plan permits applications

for transfer only for the 12th grade for the school year

1964-65. Thereafter, the transfer plan is to be similarly

5

applied to all 11th and 10th grades for 1965-66, all 9th

grades for 1966-67, all 8th grades for 1967-68, all 7th grades

for 1968-69, all 6th and 5th grades for 1969-70, all 4th

grades for 1970-71, all 3rd and 2nd grades for 1971-72, and

all 1st grades for 1972-73, becoming at that time an open

admission plan, as to first grade students, which plan will

then progress throughout the system at the speed of a

grade-a-year (R. 35, 36, 66).

A ppellan ts’ O bjections an d In te r im P lan

Appellants, in objections filed with the court on March

16, 1964, objected to the Board plan on the following

grounds (R. 37-39):

That no criteria were enumerated to guide the Super

intendent in the granting or refusal of applications for

transfer and in the designation of public schools to be

attended; nor was there any procedure for appeal pro

vided, in the event of dissatisfaction with the designa

tion;

Dual racial zones are maintained and there is no basic

plan for bringing about a transition to a unitary non-

racial system at any time in the immediate future;

The plan places the burden of initiating any change on

the student seeking transfer;

The provisions establishing an advisory committee are

vague and indefinite; and the plan purports to permit

9 years for the total desegregation of the Publie School

System of Bibb County even though it has been 10 years

since the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 IT. S. 483 (1954).

Appellants submitted their own interim plan of desegre

gation calling for freedom of choice assignments in all

grades, and continuing such policy until the Board began

assigning all students without regard to race (E. 40-41).

6

B o ard D efense o f I ts P la n

Hearing was held on the Board’s plan and the objec

tions thereto on April 13-14, 1964 (R. 42). The testimony

of the Superintendent, Julius L. Gfholson, revealed that

there are recognized geographical areas for white children

and recognized geographical areas for colored children

which are different and which determine school assign

ments; that the prior practice of assigning students on a

racial basis by means of school capacity and the avail

ability of transportation to the schools was not changed,

only limited by the “opportunity” to transfer to a different

school under the proposed plan (R. 60). He further testi

fied that the criteria for transfer included scholastic eli

gibility, availability of space, capacity of the school and

transportation (R. 61-62). Mr. G-holson stated that it would

take nine years for the plan to include all the classes of

the public school system and that the plan was essentially

a transfer plan, dependent upon a student application for

its efficacy (R. 66-67). He also testified that problems of

changing customs and traditions, with their strong psycho

logical impact on the community, were ̂ grounds for the_

Relay inherent'in the plan (R. 71). When questioned as to

the basis of his interpretation, he admitted that his sources

were second-hand, consisting of periodicals that he had

read, in particular, The U. 8. News and World Report, and

talks with other Superintendents at a “professional meet

ing” (R. 74). For similar reasons, the Board refused to

include teacher desegregation as a part of their plan (R.

68-74).

Mr. Miller, a Board member and attorney (R. 117) testi

fied that a committee was formed back in 1955, after the

first decision implementing Brown; that there was a subse

quent committee, and later, still a third committee; and

7

that each of these committees began to do “something”

after a request on the part of those seeking to get the

Board to act (R. 122-23). During the period between 1955

and 1961, the Board’s inactivity was explained in terms of

the barriers set up by the State: the new package laws;

and the laws enforcing segregation which were already on

the books, the violation of which, the Board feared, would

have resulted in a termination of State funds (R. 122).

'When the Georgia legislature repealed statutory pro

visions requiring segregation, the Board thereafter ques

tioned its own authority to implement the Supreme Court

mandate because of the provision requiring segregation in

its own charter (R. 118).

Mr. Miller also testified, both on direct and cross-exami

nation, that it was the opinion of the committee and subse

quently the resolution of the Board that there should be

no recommendation of a voluntary plan of integration (R.

139). Mr. Miller based, his opposition to “mass desegrega

tion” on the grounds of projected difficulties and the need

to limit and forestall friction. He had no first-hand knowl

edge of impending difficulties or friction, relying mainly on

mass media for his opinions (R. 140-41).

Dr. Leon R. Culpepper, a Board official who will admin

ister the plan (R. 146), indicated that the plan had been

under study for a year (R. 171). He explained the Board

procedures that follow filing of an application for transfer.

In summary, transfer application forms, which are obtain

able only at the office of the Board of Education (R. 148),

must be signed by the student, his parent and a witness,

(R. 150), and returned during a 30 day transfer period

(R. 148). The Superintendent then obtains a complete

transcript of the student’s grades, including aptitude and

achievement tests, and additional information on his “atti

tude, cooperation and stability” (R. 152). He then grants

or denies the application based on “eligibility” which means

passing marks (E. 153), “availability” which refers to avail

ability of a school bus or city buses with regard to the

school requested for; and “capacity” pertaining to the

capacity of the school to which the student seeks to transfer

(R. 154).

The plan permits the Superintendent to call in the stu

dent seeking transfer and his parents to clear up discrepan

cies or irregularities in the application or to point out

reasons why the requested transfer is not in the student’s

own best interests (R. 155). Students in “disciplinary diffi

culty” may for that reason be denied transfer (R. 158).

Superintendent Julius L. Gholson testified that the deci

sion was made to start at the upper grades rather than the

lower grades because 1) “at that stage the students were

more mature and that you could appeal to them and reason

with them, and could probably get better cooperation be

cause of their maturity.” 2) “Their parents are not as

emotionally concerned with them at the 11th and 12th

grades in senior high schools as they would be if they were

first entering school; and you would not have as many prob

lems because of emotionalism and concern of parents” (R.

185-86).

Dr. Weaver, Board President, revealed that his opposi-.

tion to mass integration by a speedier plan was based

solely on a ’ subjective evaluation of what he had heard ,

from others and read in the press (R. 201, 203).

9

A p prova l o f P la n by L ow er C o u rt

The court below approved the Board’s plan as submitted

(R. 278-97) and denied ail injunctive relief sought by ap

pellants. Reviewing the record, including the Board’s in

action in the face of several petitions calling for school de

segregation, and its refusal to abandon segregated schools

without a federal court order (R. 291), the court concluded

that the Board plan is “legally sufficient and acceptable”

(R. 296).

Notice of appeal was filed on May 25, 1964 (R. 298-99).

Specifications of Error

The District Court erred in :

1. Refusing to enjoin the operation of a dual system in

Bibb County, Georgia, based wholly upon race and the as

signment of children to schools on the basis of the dual

system.

2. Refusing to rule on the validity of requiring assign

ment of professional school personnel to the schools of Bibb

County on a non-racial basis as part of a desegregation

plan.

3. Approving a “transfer” plan which operates to delay

and to postpone at least nine years even the commencement

of freedom of choice assignments in the public schools of

Bibb County.

10

A R G U M E N T

Appellees’ 20 Year Desegregation Plan Fails to Meet

the Minimal Standards Set by This Court and Coun

tenances Impermissible Delay.

The Board of Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb

County required to produce a desegregation plan under

the compulsion of a court order after years of conscious

delay, has attempted to further evade the mandate of

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) and the

more recent admonitions of Watson v. City of Memphis, 373

U. S. 526, Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knox

ville, 373 U. S. 683 (1963), Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U. S.

263 (1964), Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Ed

ward County, 377 U. S. 218 (1964). Evasion is perpetrated

by a transfer plan which frustrates and postpones mean

ingful desegregation for a period of twenty years.

The plan, commencing at the twelfth grade level, and

operating on a descending basis, will take nine years to

reach grade one. It then becomes a freedom of choice plan

as to students entering the first grade and progresses with

that class through the system until in 1984, all students

will have a choice of attending, either Negro or white

schools.

The plan is more deliberately slothful than those of the

“grade-a-year” variety now rejected by the Third, Fourth,

Fifth and Sixth Circuits in Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385

(3rd Cir. 1960), cert, denied, 364 U. S. 81 (1961); Jackson

v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d 230

(4th Cir. 1963); Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308

F. 2d 491, 500, 501-502 (5th Cir. 1962); Goss v. Board of

Education of City of Knoxville, 301 F. 2d 164 (6th Cir.

1962), rev’d on other grounds, 373 U. S. 683, and falls

seriously short of the timing required by Watson, a time

11

table based on the number of years that have already

elapsed since Brown. The court in Watson said:

Given the extended time which has elapsed, it is far

from clear that the mandate of the second Brown deci

sion requiring that desegregation proceed with “all

deliberate speed” would today be fully satisfied by

types of plans or programs for desegregation of public

educational facilities which eight years ago might have

been deemed sufficient. 373 U. 8. 526, 530.

The plan before the court also falls far short of the mini

mal standards set for desegregation plans on June 18, 1964,

in Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Board of Education; Arm

strong v. Board of Education of Birmingham; and Davis

v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile. In these deci

sions, issued after the lower court’s decision and the filing

of this appeal, this Court again condemned desegregation

at a grade per year pace, and held that plans beginning in

the 12th grade must also end segregation in the first grade

as to students entering the system for the first time so that

the bi-racial system is not perpetuated. Moreover, this

Court said in Stell v. Savannah-Chatham, supra:

. . . a necessary part of any plan is a provision that

the dual or bi-racial school attendance system, i.e.,

separate attendance areas, districts or zones for the

races, shall be abolished contemporaneously with the

application of the plan to the respective grades when

and as reached by it.

More recently this Court in Gaines v. Dougherty County

Board of Education, No. 20984 (July 31, 1964) required a

start in grades one, two and twelve, with at least three addi

tional grades to be added to the plan yearly “ . . . in order

that every Negro child in the Dougherty County School

System have at least an opportunity to enjoy a desegregated

12

education during Ms school career.” As to grades being

desegregated, each child may choose the nearest formerly

Negro or white school. Such choice must be granted unless

the school chosen is already crowded with pupils living

closer to that school, or until the Board submits a plan

assigning all pupils to the schools nearest their residence.

Clearly, the Board’s plan fails to meet this Court’s mini

mal standards as to speed and coverage, but a closer look

at the plan reveals not simply a nine year delay in the

effectuation of the transfer plan but further, a twenty year

delay in the effectuation of desegregation in the system of

public education. The plan, which has been accepted by

the court below, insures no rights, and provides merely for

a grade by grade opportunity to transfer from one school

to the other, beginning with grade 12. Only when the trans

fer program reaches grade one—some nine years later—

does appellee’s “desegregation plan” apply to entering stu

dents automatically and on a nonracial basis. At that point,

however, it would take eleven more years before all grades

were affected by the unitary nonracial admissions.

This spotlights what is perhaps the most glaring defi

ciency of the plan: that it is not a desegregation plan at

all—only a transfer plan with even freedom of choice as

signments effectively postponed for nine more years. As a

nine year transfer plan, the Bibb County plan not only post

pones the commencement of desegregation, but does so by

a method which has been explicitly rejected by the courts.

The burden of getting out of the segregated arrangement is

placed upon the student; if no one applies for transfer,

nothing at all is done: all children are reassigned to the

same schools that they are now attending.

This burden is weighted with variations of the onerous

transfer requirements frequently condemned by this Court.

For example, transfer applications must be made on a form

13

obtainable only at the Board’s office (R. 148). The form

must be signed by the pupil, his parents or guardian and

a witness (R. 150).1 The Board Superintendent studies the

transfer applicant’s grades, including achievement scores,

his personality as indicated by his “attitude”, “cooperation”

and “stability” (R. 152), considers eligibility, availability

and school capacity (R. 153-54). He may call in the student

and parents for a conference to discuss irregularities in

the application, or to point out why the transfer is not in

the pupil’s best interests (R. 155), and may deny applica

tions of pupils deemed in “disciplinary difficulty” (R, 158).2

It will not be surprising that most Negro parents and stu

dents will hesitate to exercise their opportunity to transfer

to white schools after considering the difficulties of nego

tiating these administrative obstacles, none of which are

required of white children assigned to white schools as a

matter of course.3

The inadequacy of the plan becomes more glaring and

more manifestly calculated when placed in the context of

the Board’s inactivity, delay and express opposition to the

desegregation of the Bibb County Public Schools. The

1 “Onerous requirements such as the notarization of applications

for assignment are not to be condoned.” St ell v. Savannah-Chatham

Board of Education, supra.

2 Special criteria, including special standards of scholastic

achievement, personality or conduct applied only to transfer ap

plicants have been condemned in Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Board

of Education, supra; Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F. 2d 302 (5th Cir.

1963).

3 Preliminai’y reports indicate that only 34 Negroes obtained

transfer application forms as provided in ^he Board’s plan.

Twenty-nine forms were returned, and while 28 applications were

approved (one was denied for scholastic reasons), four have

dropped out for reasons which include discouragement by teachers,

and one has moved out of the district. Thus, at this point, with

school opening still a month away, only 25 of the 13,000 Negro

students in the system will be attending desegregated schools.

14

Board repeatedly refused to initiate a clarification of the

state law and its own authority, despite petitions by citi

zens of Bibb County. After the state legislature finally

lifted its own statutory prohibition of desegregation, the

Board again dragged its feet, this time by seeking a declara

tory judgment on the question of its authority under a

Charter provision inconsistent with the newly defined state

law.

Even after the Superior Court cleared the way for affirm

ative action, the Board chose instead to await the com

pulsion of a court order, voting to record a resolution of a

majority of the Board that the latter continue its present

segregated system of operating its schools because of a

conviction that “integration of the races in the public

schools of Bibb County will be detrimental to both the

colored and white races” ; and because they felt “the vast

majority of both our colored and white citizens of Bibb

County are satisfied with the present system of operation

of our schools, . . . ” (B. 25).

The Board’s plan, apparently prepared with these convic

tions and feelings in mind, clearly evidences a desire and

intent to replace total segregation with token integration.

The court below, however, refused to condemn the Board

for their frankness, stating: “Independence of thought is

encouraged, and freedom of speech is guaranteed” (B. 291).4

4 This Court’s opinions have uniformly condemned the failure

of school boards to act because they felt segregation should be

retained, and at least two other circuits have taken a less charitable

view of Board statements of disagreement than did the court below.

In Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, Tennessee, 301 F. 2d

164, 167 (6th Cir. 1962), the Court said: “The position of the

Board that it would continue to operate under these invalid laws,

until compelled by law to do otherwise, does not commend itself

to the Court,. . . ”

In Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia, 321 F. 2d

494, 499 (4th Cir. 1963), the Court, noting the declaration of

15

Appellants submit that while the Board may disapprove of

the Supreme Court’s decision, they have no' right to disobey.

Candor, whatever its virtues, is not compliance.

Compliance in this case requires the Board to produce a

desegregation plan meeting the minimal standards recently

summarized by this Court in Stell v. Savcmwah-Chatham

Board of Education, but clearly set forth in decisions avail

able when this case was acted on below.5 Thus, the pace

of desegregation may not be set at a snail’s pace because

of fear that a faster speed will result in community dis

orders. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958). As stated

in the Savannah decision, it is the lot of district courts to

act:

“ • • • where school boards do not voluntarily follow the

Constitution with relation to school operations, and

once suits are filed in the District Court, to impose the

burden on the school boards of justifying delay in the

required full implementation of the constitutional

rights involved.”

The Bibb County Board has had ample opportunity to

initiate voluntary desegregation and there is no doubt that

if a plan had been offered, it would have received the

Board counsel in oral argument that: “If it is our duty to en

courage integration, then we have violated our duty!,” concluded

sternly, “The School Board has indeed violated its duty.”

5 Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862

(5th Cir. 1962); Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d

491 (5th Cir. 1962). Even in injunctions ordered by this Court

pending appeal, segregated schools were enjoined, and the school

boards required to either completely end segregation with respect

to one grade, Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Edu

cation, 318 F. 2d 425 (5th Cir. 1963), or accept transfer applica

tions in all grades. Armstrong v. Board of Education of Birming

ham, 323 F. 2d 333 (5th Cir. 1963); Davis v. School Commissioners

of Mobile County, 322 F. 2d 356 (5th Cir. 1963).

16

cooperation of the plaintiffs (E. 322-25), local Human

Eelations groups (E. 328), and this Court. See Glynn

County Board of Education v. Gibson, ----- F. 2d -----

(June 18, 1964), where this Court noted the Board’s efforts

to voluntarily begin desegregation and accordingly with

held injunctive relief.

But the Board, with a full complement of legal talent,

has chosen for ten years to answer requests and petitions

for desegregation with silence (E. 322-23), committees (E.

334-35), and frivolous legal action (E. 345-51). It is not

the purpose of this appeal to determine the Board’s good

faith in the past or present, nor may good faith be made an

issue where, as here, the Board submits a desegregation

plan, ten years after Brown, which will require twenty

years before providing the degree of desegregation which

has been obtained this year in many communities;6 and

6 In South Carolina, the Charleston and Greenville Boards have

been ordered to grant free transfers in all grades. Brown v. School

District No. 20, 226 F. Supp. 819 (B. D. S. C. 1963), aff’d 328

F. 2d 618 (4th Cir. 1964); Whittenberg v. School District of Green

ville County, S. C., Civ. No. 4396 (W. D. S. C.).

In North Carolina, the Durham Board has been ordered to per

mit freedom of choice assignments in all grades effective in 1964.

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, Civ. No. C-54-D-60

(M. D. N. C.). Freedom of choice plans have also been placed in

effect in several other North Carolina communities after school

desegregation suits were filed. These include: Jeffers v. Whitley

(Caswell County), 309 F. 2d 621, 629 (4th Cir. 1962); Belo v.

Randolph County Board of Education, Civ. No. 209-G-63 (M. D.

N. C .); DuBissette, et al. v. Cabarrus County Board of Education

(M. D. N. C.) ; Eaton v. New Hanover County, 1022 (E. D. N. C.) ;

Ford v. Cumberland County Board of Education, No. 668 (E. IX

N. C .); Gill v. Concord City Board of Education, No. C-223-S-63

(M. D. N. C.) ; Gilmore v. High Point Board of Education (M. D.

N. C.) No. C-51-G-63; Griffith v. Board of Education of Yancey

County, Civ. No. 1881 (W. D. N. C .); Zigler v. Reidsville Board of

Education, C-226-G-62 (M. D. N. C .); Turner v. Warren County

Board of Education 1482 (B. D. N. C.) ; Sowers v. Lexington City

Board of Education, C-20-S-64 (M. D. N. C.).

17

which will be granted in no more than four years in Albany,

Georgia, Gaines v. Dougherty County Board of Education,

supra, and will be realized in sis years in several Georgia

and Alabama communities even if plans presently in opera

tion are not accelerated.7

Appellants contend that neither the Board nor the district

court have provided them and their class the relief to which,

under applicable decisions, they are presently entitled. In

similar circumstances, this Court has repeatedly stated

the sequence of responsibility now rests with the appellate

courts. Rippy v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690, 693 (5th Cir.

1957) ; Armstrong v. Board of Education of Birmingham,

supra; Hall v. Hon. E. Gordon West, —-— F. 2 d ----- (5th

Cir., July 9, 1964). Counsel for appellees argued below

In Tennessee desegregation now encompasses all grades in Goss

v. Board of Education of Knoxville, No. 3984 (E. D. Tenn.); Boyce

v. County Board of Education of Humphreys County, Tenn., Civ.

No. 3130 (M. D. Tenn.); Vick v. County Board of Education of

Obion County, Tenn. (Civ. No. 1259) (W. D. Tenn.).

In Virginia a free transfer plan has been approved in Richmond.

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, Virginia, Civ. No.

\ 3353 (E. D. Va.).

The above cases are intended to be illustrative rather than ex

haustive.

7 Savannah and Brunswick, Georgia are in the second year of

desegregation according to a transfer plan which will reach all

grades by 1968. See: Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Board of Edu

cation, — F. 2 d ----- - (5th Cir., June 18, 1964).

In Alabama, similar plans are now in effect in Birmingham,

Mobile, Gadsden, Huntsville, Madison County and Montgomery.

Significantly for the present case, in all but Mobile and Birming

ham, initial desegregation plans encompass four grades. See: Arm

strong v. Board of Education of Birmingham, - ---- F. 2d ------

(5th Cir., June 18, 1964); Mobile, Davis v. Board of School

Commissioners of Mobile County,----- F. 2 d ------ • (5th Cir., June

18, 1964) ; Miller v. Board of Education of Gadsden, Alabama,

Civ. No. 63-574 (N. D. A la.); Hereford v. Huntsville Board of

Education, Civ. No. 63-109 (N. D. A la.); Bennett v. Madison

County Board of Education, Civ. No. 63-613 (N. D. A la .); Carr

v. Montgomery County Board of Education, Civ. No. 2072-N (M. D.

Ala.).

18

that the Board is not a litigant in this case but a supplicant

seeking “guidance and direction in a delicate and difficult

field” (R. 309). Experience and precedent indicate that

this Court’s guidance and direction should include instruc

tions to the court below to enter an order directing the

Board to promptly file a similar plan to those recently

required in Stell v. Savannah-Chatham, supra, and Gaines

y. Dougherty County Board of Education, supra-, and that

such relief be made effective in January 1965, so that the

Bibb County Board may at last be placed in step with

those in Savannah, Brunswick, Albany and Atlanta,

Georgia.

CONCLUSION

W h e r e fo r e , for all the foregoing reasons, appellants

request that the order of the court below approving the

appellee Board’s plan be reversed with directions to enter

an order requiring the Board to promptly submit a plan

which meets the minimal standards set for such plans in

the Savannah, Georgia, and Birmingham, Alabama cases

decided by this Court on June 18, 1964, and requiring im

plementation in January 1965 of desegregation according to

the terms of this Court’s opinion in Gaines v. Dougherty

County Board of Education, supra.

Respectfully submitted,

D onald L. H ollow ell

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

J ack G reenberg

C onstance B a ker M otley

D er r ic k A. B e l l , J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants.

19

Certificate of Service

The undersigned, one of counsel for appellants, hereby

certifies that on this day of August, 1964, he served

three copies of the Brief for Appellants upon C. Baxter

Jones, Esq., attorney for appellees, at 1007 Persons Build

ing, Macon, Georgia, by depositing same in the United

States mail, air mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellants

38