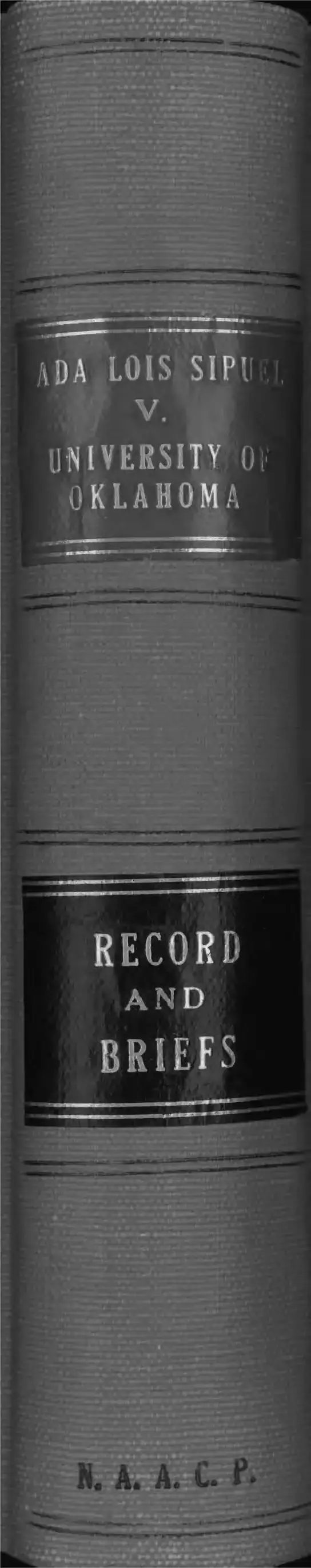

Sipuel v. University of Oklahoma Brief for the Plaintiff-In-Error

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sipuel v. University of Oklahoma Brief for the Plaintiff-In-Error, 1948. 785a11d4-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c2ad67d-de93-46f0-919d-76a4006fa302/sipuel-v-university-of-oklahoma-brief-for-the-plaintiff-in-error. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

ADA L O I S S I P l

V.

U N I V E R S I T Y Oi'

O K L A H O M A

RECORD

A N D

B R I E F S

x >

N o . 3 2 7 5 6

In the

Supreme GInurt nf tty >̂tate of GDklaltnma

ADA LOIS SIPUEL, Plaintiff-in-error,

vs.

BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLA

HOMA, GEORGE L. CROSS, MAURICE H. MERRILL,

GEORGE WADSACK and ROY GITTINGER,

Defendants-in-error.

Appeal from the District Court of Cleveland County,

Oklahoma; Honorable Ben T. Williams, Judge.

BRIEF FOR THE PLAINTIFF-IN-ERROR

AMOS T. HALL

107 */2 N. G reenw ood Avenue

Tulsa, O klahom a

THURGOOD MARSHALL

ROBERT L. CARTER

20 West 40th Street

New York, N. Y.

Attorneys for Plaintiff-in-error

FRANKLIN H. WILLIAMS

New York, New York

Of Counsel

(Action in Mandamus)

I N D E X .

Statem ent, n f C a se

PAGE

______ _________________ 1

S ta te m e n t o f F a c ts 2

Argument:

I. The refusal to admit plaintiff-in-error to the

School of Law of the University of Oklahoma consti

tutes a denial of rights secured under the Fourteenth

Am endm ent________________________________________ 4

A. Distinctions on the Basis of Race and Color

Are Forbidden Under Our Laws___________________ 4

Alston v. Norfolk School Board, 112 F. (2d)

992 (C. C. A. 4th, 1940), cert. den. 311 U. S. 693

(1940)________________________________________ 7

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917)____ 7

Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 (1944)________ 7

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 (1879)______ 6, 7

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400 (1942)___________ 7

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81

(1943) ...... __ 7

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214

(1944) _______________________________________ 7

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S.

337 (1938) _______________________________

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354 (1939)

Slaughter House Cases, 16 Wall (U. S.) 394..

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944)____

Steele v. Louisville and Nashville R. Co., 323

U. S. 192 (1944)_______________________________ 7

Strauder v. Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1879)___ 5

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Fire

men, 323 U. S. 210 (1944)______________________ 7

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886)___ 7

c- t-

c-

11

B. Rational Basis for the Equal But Separate

Doctrine Is That Although a State May Require

Segregation, Equality Must Be Afforded Under the

Segregation S ystem --------------------------------------------- 7

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917)------ 8

• Gong Lum v. Bice, 275 U. S. 78 (1928)--------- 7, 8

Johnson v. School Board, 166 N. C. 468, 82

S. E. 832 (1914)_____________________________ 8

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941).. 7, 8

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S.

337 (1938)_____________________________________7, 8

Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 540

(1936) ________________________________________ 7

People v. Gallagher, 93 N. Y. 438, 45 Am. Rep.

232 (1883)____________________________________ 8

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896)____ 7, 8

Roberts v. City of Boston, 5 Cush (Mass.)

198 (1849) ____________________________________ 8

Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36 (1874)____________ 7, 8

C. Equality Under a Segregated System is a

Legal Fiction and a Judicial Myth________________ 9

1. The General Inequities in Public Educa

tion Systems Where Segregation is Required___ 9

2. On the Professional School Level the In

equities are Even More Glaring_______________ 12

D. The Requirements of the 14th Amendment

Can Be Met Only Under an Unsegregated Public

Educational System ____ 17

E. Even Under “ Equal But Separate” Doc

trine, the Action of Defendants-in-Error Violated

the Fourteenth Amendment_______________________ 18

II. The application for a writ of mandamus to com

pel the defendant-in-error to admit plaintiff-in-error

to the Law School of the University of Oklahoma was

proper and should have been granted by the court below 19

A. Mandamus Should Issue as Prayed For___ 19

Blodgett v. Holden, 275 U. S. 142 (1928)____ 23

Comley ex rel. Rowell v. Boyle, 115 Conn.

406, 162 Atl. 26 (1932)_________________________ 20

PAGE

I ll

Federal Trade Commission v. American

Tobacco Co., 264 U. S. 298 (1924)______________ 23

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S.

337 (1938)_________________________ 19,21,22,23,24

Missouri P. R. Co. v. Boone, 270 U. S. 466

(1926)________________________________________ 23

National Labor Relations Bd. v. Jones &

Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U. S. 1 (1936)------------ 23

Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590

(1936)________________________________ 19, 21,23,24

Panama R. Co. v. Johnson, 264 U. S. 375

(1924) _______________ ________________________ 23

Richmond Screw Anchor Co. v. United States,

275 U. S. 331 (1928)___________________________ 23

Sharpless v. Buckles, et al., 65 Kan. 838,

70 Pac. 886 (1902)___________________________ 19,20

State ex rel. Hunter v. Winterrowd, 174 Ind.

592, 92 N. E. 650 (1910)_______________________19, 21

Welch v. Swasey, 193 Mass. 364, 79 N. E.

745 (1907) ____________________________________ 21

B. Prior Demand on Board of Higher Educa

tion to Establish a Law School at Langston Uni

versity Is Not a Prerequisite to This Action_______ 24

Board of County Commrs. v. New Mexico

ex rel. Coler, 215 U. S. 296, 303 (1909)__________ 26

City of Port Townsend v. First Natl. Bank,

241 Fed. 32 (C. C. A. 9th, 1917)______________ 27

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co., 235

U. S. 151, 160 (1914)___________ 25

McGillvray Const. Co. v. Hoskins, 54 Cal.

App. 636, 202 Pac. 677 (1921)__________________ 27

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80, 96

(1941)________________________________________ 25

Northern Pacific R. R. Co. v. Washington,

142 U. S. 492, 508 (1891)______________________ 26

Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590

(1936) ________________________________________

Peo. ex rel. John Pear v. Bd. of Education,

PAGE

25

PAGE

127 111. 613, 625 (1889)________________________ 26

Pugsley v. Sellmeyer, 150 Ark. 247, 250 S. W.

538 (1923) 27

United States v. Saunders, 124 Fed. 124 (C.

C. A. 8th, 1903)_____________________________ 26, 27

United States ex rel. Aetna Ins. Co. v. Bd.

etc. of Town of Brooklyn, 8 Fed. 473, 475 (N. D.

111. 1881) ____________________________________ 27

Statutes.

Oklahoma Constitution, Art. 13, Sec. 3------------------------ 22

Oklahoma Constitution, Art. 13a, Secs. 1 and 2------------ 26

Oklahoma Statutes (1941) 70, Secs. 363, 451-470, 1591-

1593 ______________ :______________________________ 22

Oklahoma Statutes (1941 as amended 1945), Secs. 1451-

1509 ____________________________________ ________ 24

Other A uthorities.

American Teachers’ Association, The Black and White

of Rejections for Military Service (1944)-------------- 11,12

Blose, David T. and Ambrose Caliver, Statistics of the

Education of Negroes {A Decade of Progress)

(1943) __________________________________________ 10,11

Biennial Surveys of Education in the United States.

Statistics of State School Systems, 1939-40 and

1941-42 (1944) ___________________________________ 11

Dodson, Dan W. The American Mercury (July, 1946)- 16

Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment

(1908) ___________________________________________ 5

Lawyer’s Edition, Annotations, Yol. 27, p. 836________ 8

Lawyer’s Edition, Annotations, Vol. 44, p. 262______ 8

Merrill, Law of Mandamus (1892)__________________ 26, 27

National Survey of Higher Education for Negroes

(1943) ___________________________________________ 15

Sixteenth Census of the United States: Population,

Yol. I ll , Part 4 (1940)___________________________ 13

Thompson, Charles T., Negro Journal of Education,

Vol. 14 (1945)____________________________________ 13

In the

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA

No. 32756

ADA LOIS SIPUEL, Plaintiff-in-error,

vs.

BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLA

HOMA, GEORGE L. CROSS, MAURICE H. MERRILL,

GEORGE WADSACK and ROY GITTINGER,

Defendants-in-error.

BRIEF FOR THE PLAINTIFF-IN-ERROR.

Statement of the Case.

This is an appeal from the judgment of the District

Court of Cleveland County denying application of plaintiff-

in-error for writ of mandamus entered upon a hearing held

on July 9, 1946 to show cause why defendants-in-error

should not be compelled to admit plaintiff-in-error to the

first-year class of the School of Law of the University of

Oklahoma. In its opinion, the Court below adopted the

view that mandamus will not lie to compel state officers

to disregard the specific commands of state statutes at the

behest of a plaintiff who considers such statutes unconsti

tutional (R. 36-37). Plaintiff-in-error interposed a timely

motion for a new trial on July 9, 1946 (R. 45), which motion

was duly overruled on July 12, 1946 (R. 47); whereupon

this appeal was instituted.

2

Statement of Facts.

The facts in issue are uncontroverted and have been

agreed to by both plaintiff and defendants-in-error (R. 38-

40). The following are the stipulated facts:

That the plaintiff-in-error is a resident and citizen of

the United States and of the State of Oklahoma, County of

Grady and City of Chickasha, and desires to study law in

the School of Law in the University of Oklahoma for the

purpose of preparing herself to practice law in the State

of Oklahoma (R. 38).

That the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma

is the only law school in the State maintained by the State

and under its control (R. 38).

That the Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa is an administrative agency of the State and exer

cises over-all authority with reference to the regulation of

instruction and admission of students in the University of

Oklahoma; that the University is a part of the educational

system of the State and is maintained by appropriations

from public funds raised by taxation from the citizens

and taxpayers of the State of Oklahoma; that the School

of Law of the Oklahoma University specializes in law and

procedure which regulates the government and courts of

justice in Oklahoma; that there is no other law school main

tained by public funds of the State where the plaintiff-in

error can study Oklahoma law and procedure to the same

extent and on an equal level of scholarship and intensity as

in the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma; that

the plaintiff-in-error will be placed at a distinct disad

vantage at the bar of Oklahoma and in the public service

of the aforesaid State with respect to persons who have had

the benefit of the unique preparation in Oklahoma law and

3

procedure offered at the School of Law of the University of

Oklahoma, unless she is permitted to attend the aforesaid

institution (R. 38-39).

That the plaintiff-in-error has completed the full college

course at Langston University, a college maintained and

operated by the State of Oklahoma for the higher educa

tion of its Negro citizens (R. 39).

That the plaintiff-in-error made due and timely appli

cation for admission to the first year class of the School of

Law of the University of Oklahoma on January 14, 1946,

for the semester beginning January 15, 1946, and that she

then possessed and still possesses all the scholastic and

moral qualifications required for such admission (R. 39).

That on January 14, 1946, when plaintiff-in-error ap

plied for admission to the said School of Law, she complied

with all of the rules and regulations entitling her to admis

sion by filing with the proper officials of the University, an

official transcript of her scholastic record; that said tran

script was duly examined and inspected by the President,

Dean of Admission and Registrar of the University (all

defendants-in-error herein) and was found to be an official

transcript entitling her to admission to the School of Law

of the said University (R. 39-40).

That under the public policy of the State of Oklahoma,

as evidenced by the constitutional and statutory provisions

referred to in the answer of defendants-in-error herein,

plaintiff-in-error was denied admission to the School of

Law of the University of Oklahoma solely because of her

race and color (R. 40).

That the plaintiff-in-error, at the time she applied for

admission to the said school of the University of Okla

homa, was and is now ready and willing to pay all of the

4

lawful charges, fees and tuitions required by the rules and

regulations of the said University (R. 40).

That plaintiff-in-error has not applied to the Board of

Regents of Higher Education to prescribe a school of law

similar to the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma

as a part of the standards of higher education of Langston

University, and as one of the courses of study thereof

(R. 40).

It was further stipulated between the parties that after

the filing of this case, the Board of Regents of Higher

Education had notice that this case was pending and met

and considered the questions involved herein and had no

unallocated funds on hand or under its control at the time

with which to open up and operate a law school and has

since made no allocation for such a purpose (R. 43).

A R G U M E N T .

I.

The refusal to admit plaintiff-in-error to the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma constitutes a

denial of rights secured under the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

A. Distinctions on the Basis of Race and Color Are

Forbidden Under Our Laws.

One of the most firmly entrenched principles of Ameri

can constitutional law is that discrimination by a state based

on race and color contravenes the federal constitution. The

13th, 14th and 15th Amendments were specifically added to

the Constitution to give Negroes full citizenship rights and

5

to bar any future efforts to alter their status in that re

gard.1 The Court stated in Strauder v. Virginia:

“ This is one of a series of constitutional pro

visions having a common purpose, namely: securing

to a race recently emancipated, a race that through

many generations had been held in slavery, all the

civil rights that the superior race enjoy. The true

spirit and meaning of the Amendments * * * can

not be understood without keeping in view the his

tory of the times when they were adopted, and the

general objects they plainly sought to accomplish.

At the time when they were incorporated into the

Constitution, it required little knowledge of human

nature to anticipate that those who had long been

regarded as an inferior and subject race would, when

suddenly raised to the rank of citizenship, be looked

upon with jealousy and positive dislike, and that

state laws might be enacted or enforced to perpetu

ate the distinctions that had before existed. Dis

criminations against them had been habitual. It was

well known that, in some States, laws making such

discriminations then existed, and others might well

be expected.”

* * # * ' * • * *

“ . . . [the 14th Amendment] was designed to

assure to the colored race the enjoyment of all the

civil rights that under the law are enjoyed by white

persons, and to give to that race the protection of

the General Government, in that enjoyment, when

ever it should be denied by the States. It not only

gave citizenship and the privileges of citizenship to

persons of color, but it denied to any State the power

to withhold from them the equal protection of the

laws, and authorized Congress to enforce its provi

sions by appropriate legislation.”

* * * * * * * * 1

1 Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment (1908).

6

“ If this is the spirit and meaning of the Amend

ment, whether it means more or not, it is to be con

strued liberally, to carry out the purposes of its

framers. It ordains that no State shall make or

enforce any laws which shall abridge the privileges

or immunities of citizens of the United States * * *.

It ordains that no State shall deprive any person

of life, liberty or property, without due process of

law, or deny to any person within its jurisdiction the

equal protection of the laws. What is this but declar

ing that the law in the States shall be the same for

the black as for the white; that all persons whether

colored or white, shall stand equal before the laws

of the States and, in regard to the colored race, for

whose protection the Amendment was primarily de

signed, that no discrimination shall be made against

them by law because of their color? The words of

the Amendment, it is true, are prohibitory, but they

contain a necessary implication of a positive immun

ity, or right, most valuable to the colored race—the

right to exemption from unfriendly legislation

against them distinctively as colored; exemption

from legal discriminations, implying inferiority in

civil society, lessening the security of their enjoy

ment of the rights which others enjoy, and discrim

inations which are steps towards reducing them to

the condition of a subject race.” 2

The express guarantees against discrimination on the

basis of race and color run only against the states, hut

these guarantees are considered so fundamental to our

political and social health that even in the absence of

express constitutional prohibitions, the federal govern

ment is prohibited from making any classifications and dis

tinctions on the basis of race and color. They are regarded

2 100 U. S. 303, 306, 307 (1879); see to same effect The Slaughter

House Cases, 16 Wall. (U . S.) 36 (1873); E x parte Virginia, 100

U. S. 339 (1879).

7

as arbitrary, unreasonable, constitutionality irrelevant and,

therefore, violative of the 5th Amendment.8

The United States Supreme Court, and American courts

in general, in giving life and substance to these abstract

constitutional guarantees have been required to strike down

statutes and governmental action in derogation thereof

without regard to local racial customs and practices requir

ing such color classifications.4

B. The Rational Basis for the Equal But Separate

Doctrine Is That Although a State May Require

Segregation, Equality Must Be Afforded Under

the Segregation System.

History has proved that democracy can flourish only

when its citizens are enlightened and intelligent. For this

reason, the states, even though under no obligation to do so,

have almost uniformly undertaken the task of providing free

education through the elementary and high school level,

and education through the college and professional level at

minimum cost to the individual. Having voluntarily under

taken to provide such opportunities, our Constitution and

laws require that such opportunities be afforded to all per

sons without regard to racial distinctions.5

3 Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81 (1943); Korematsu

v. United States, 323 U. S. 214 (1944); E x parte Endo, 323 U. S.

283 (1944) ; see also Steele v. Louisville and Nashville R. Co., 323

U. S. 192 (1944); Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen,

323 U. S. 210 (1944).

4 E x parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 (1879); Yick W o v. Hopkins,

118 U. S. 356 (1886); Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) ;

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) ; Pierre v.

Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354 (1939); Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400

(1942) ; Alston v. Norfolk School Board, 112 F. (2d) 992 (C. C.

A. 4th, 1940); cert. den. 311 U. S. 693 (1940) ; Smith v. Allwriqht,

321 U. S. 649 (1944).

5 Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590 (1936) ; Missouri

ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938); see also Gong Lum v.

Rice, 275 U. S. 78 (1927); Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36, 17 Am. Rep.

405 (1874); People v. Gallagher, 93 N. Y. 438, 45 Am. Rep. 232

(1883); see also Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941);

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896).

8

Oklahoma along with sixteen other states and the Dis

trict of Columbia has established an educational system on

a segregated basis, with schools set aside for the exclusive

attendance of Negroes.6 This enforced segregation has

been regarded by some American courts as not in conflict

with the requirements of the 14th Amendment as long as

the facilities afforded are equal to those afforded whites.7

The United States Supreme Court has never directly de

cided whether this view constituted a proper interpreta

tion of the Constitution but has given some indication that

it is in agreement with this statement of the law.8

6 Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky,

Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Okla

homa, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and West Virginia.

7 Johnson v. School Board, 166 N. C. 468, 82 S. E. 832 (1914) ;

and cases cited in note 5, supra. Annotations on the question, 27 L.

Ed. 836 and 44 L. Ed. 262.

8 In Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896) in sustaining the

constitutionality of a Louisiana statute requiring intrastate railroads

to furnish separate but equal coach accommodations for whites and

Negroes, the United States Supreme Court cited with approval Ward

v. Flood, People v. Gallagher, supra note 5 and Roberts v. City of

Boston, 5 Cush (Mass.) 198 (1849) which held that a state could

require segregation of the races in its educational system as long as

equal facilities for Negroes were provided. In Gong Lum v. Rice,

275 U. S. 78, 85 (1927) in passing upon the right of a state to clas

sify Chinese as colored and force them to attend schools set aside for

Negroes the Court assumed that the question of the right of a state to

segregate the races in its educational system had been settled in favor

of the state by previous Supreme Court decisions. In Missouri ex rel.

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 344 (1938) the Court said obiter

dicta that right of a state to provide Negroes with educational advan

tages in separate schools equal to that provided whites had been sus

tained by previous Supreme Court decisions. In Mitchell v. United

States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941) the Court continued to uphold the

validity of the equal but separate doctrine as applied to transpor

tation facilities. But in Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) a

city ordinance which attempted to enforce residential segregation was

struck down as violating the 14th Amendment, and, in general the

Supreme Court has invalidated state action where it found that race

or color was used as a criteria as evidenced by cases cited in note 4.

The key to the difference in approach would seem to lay in Plessy v.

Ferguson, supra, which involved transportation and used state cases

upholding segregation in the state’s educational system to support

argument that segregation in transportation was valid.

9

The apparent rationalization for this rule is that the

states will provide equal educational opportunities for

Negroes under a segregated system and that therefore such

segregation does not amount to discrimination or a denial

of equal protection within the meaning of the 14th Amend

ment. PlaintifT-in-error contends that this “ equal but

separate” doctrine defeats the ends which the 14th Amend

ment was intended to achieve. If the guarantees of this

amendment are to be given life, substance and vitality,

American courts will have to recognize that segregation

itself amounts to an unlawful discrimination within the

meaning of the 14th Amendment.

C. Equality U nder a Segregated System Is a Legal

Fiction and a Judicial Myth.

There is of course a dictionary difference between the

terms segregation and discrimination. In actual practice,

however, this difference disappears. Those states which

segregate by statute in the educational system have been

primarily concerned with keeping the two races apart and

have uniformly disregarded even their own interpretation

of their requirements under the 14th Amendment to main

tain the separate facilities on an equal basis. 1

1. The General Inequities in Public Educational

Systems Where Segregation Is Required.

Racial segregation in education originated as a device

to “ keep the Negro in his place” , i. e., in a constantly in

ferior position. The continuance of segregation has been

synonymous with unfair discrimination. The perpetuation

of the principle of segregation, even under the euphemistic

theory of “ separate but equal” ,, has been tantamount to

the perpetuation of discriminatory practices. The terms

10

“ separate” and “ equal” can not be used conjunctively

in a situation of this kind; there can he no separate equality.

Nor can segregation of white and Negro .in the matter

of education facilities be justified by the glib statement

that it is required by social custom and usage and generally

accepted by the “ society” of certain geographical areas.

Of course there are some types of physical separation

which do not amount to discrimination. No one would

question the separation of certain facilities for men and

women, for old and young, for healthy and sick. Yet in

these cases no one group has any reason to feel aggrieved

even if the other group receives separate and even pref

erential treatment. There is no enforcement of an inferior

status.

This is decidedly not the case when Negroes are segre

gated in separate schools. Negroes are aggrieved; they are

discriminated against; they are relegated to an inferior

position because the entire device of educational segrega

tion has been used historically and is being used at present

to deny equality of educational opportunity to Negroes.

This is clearly demonstrated by the statistical evidence

which follows.

The taxpayers’ dollar for public education in the 17

states and the District of Columbia which practice com

pulsory racial segregation was so appropriated as to de

prive the Negro schools of an equitable share of federal,

state, county and municipal funds. The average expense

per white pupil in nine Southern states reporting to the

U. S. Office of Education in 1939-1940 was almost 212%

greater than the average expense per Negro pupil.9 Only

9 Statistics o f the Education of Negroes (A Decade of Progress)

by David T. Blose and Ambrose Caliver (Federal Security Agency,

U. S. Office of Education, 1943). Part I, Table 6, p. 6.

11

$18.82 was spent per Negro pupil, while the same average

per white pupil was $58.69.10 11

Proportionate allocation of tax monies is only one cri

terion of equal citizenship rights, although an important

one. By every other index of the quality and quantity of

educational facilities, the record of those states where seg

regation is a part of public educational policy clearly dem

onstrates the inequities and second class citizenship such

a policy creates. For example, these states in 1939-1940

gave whites an average of 171 days of schooling per school

term. Negroes received an average of only 156 days.11 The

average salary for a white teacher was $1,046 a year. The

average Negro teacher’s salary was only $601.12 13

The experience of the Selective Service administration

during the war provides evidence that the educational in

equities created by a policy of segregation not only deprive

the individual Negro citizens of the skills necessary to a

civilized existence and the Negro community of the leader

ship and professional services it so urgently needs, but also

deprive the state and nation of the full potential embodied

in the intellectual and physical resources of its Negro citi

zens. In the most critical period of June-July 1943, when

the nation was desperately short of manpower, 34.5% of

the rejections of Negroes from the armed forces were for

educational deficiencies. Only 8% of the white selectees

rejected for military service failed to meet the educational

standards measured by the Selective Service tests.18

10 Ibid, Table 8.

11 Biennial Surveys of Education in the United States. Statistics

of State School Systems, 1939-40 and 1941-42 (1944), p. 36.

12 Blose and Caliver, op. cit., supra note 9, Part I, p. 6, Table 7.

13 The Black and White of Rejections for Military Service. Mont

gomery, Ala., American Teachers Association (1944), p. 5.

12

Lest there be any doubt that this generalization applies

to Oklahoma as well, let us look at the same data for the

same period with respect to this state. We find that 16.1%

of the Negro rejections were for educational deficiency,

while only 3% of the white rejections were for this reason.14

This demonstration of the effects of inequitable segre

gation in education dramatizes one of the key issues which

this Court must decide. Failure to provide Negroes with

equal educational facilities has resulted in deprivations to

the state and nation as well as to the Negro population. The

Constitution establishes a set of principles to guide human

conduct to higher levels. If the courts reject the theory of

accepting the lowest common denominator of behavior be

cause this standard is so blatantly detrimental to the indi

vidual citizen, to the state, and to the nation as a w h o le -

then they will be exercising the power which the Constitu

tion has vested in them for the protection of the basic values

of our society.

2. On the Professional School Level the Inequi

ties Are Even More Glaring.

As gross as is the discrimination in elementary educa

tion, the failure to provide equal educational opportunities

on the professional levels is proportionately far greater.

Failure to admit Negroes into professional schools has

created a dearth of professional talent among the Negro

population. It has also deprived the Negro population of

urgently needed professional services. It has resulted in

a denial of equal access to such services to the Negro popu

lation even on a “ separate” basis.

14 Ibid.

13

In Oklahoma, the results of the legal as well as the extra-

legal policies of educational discrimination have deprived

the Negro population of professional services in the fields

of medicine, dentistry and law. The extent of this depriva

tion can best be judged by the following data, in which the

figures represent one lawyer, doctor and dentist, respec

tively, to the following number of white and Negro popula

tion : 15 16

Profession White Negro

Law _____________ ______ 643 6,494

Medicine _____ ___ ______ 976 2,165

Dentistry ______________ 2,646 7,675

That this critical situation is not peculiar to Oklahoma

alone but is an inevitable result of the policy of racial seg

regation and discrimination in education is demonstrated

by an analysis made by Dr. Charles H. Thompson.10 He

states that:

“ In 1940 there were 160,845 white and 3,524 Negro

physicians and surgeons in the United States. In

proportion to population these represented one phy

sician to the following number of the white and Negro

population, respecitvely:

Section White Negro

U. S.................... 735 3,651

North ________ ... . 695 1,800

South _______ ____ 859 5,300:

W est_________ _ _ 717 2,000

Mississippi ___ ...... 4,294 20,000

15 Based on data in Sixteenth Census of the United States: Popu

lation, Vol. I ll , Part 4, Reports by States (1940).

16 Charles H. Thompson, “ Some Critical Aspects of the Problem

of the Higher and Professional Education for Negroes,” Journal o f

Negro Education (Fall 1945), pp. 511-512.

* To the nearest hundred.

14

“ A similar situation existed in the field of den

tistry, as far as the 67,470 white and 1,463 Negro

dentists were concerned:

Section White Negro

U. S_________ _____ 1,752 8,800f

North ____________ 1,555 3,900f

South _______ 2,790 14,000f

W est_____________ 1,475 3,900f

M iss._____________ 14,190 37,000t

“ In proportion to population there are five times

as many doctors and dentists in the country as a

whole as there are Negro doctors and dentists; and

in the South, six times as many. Even in the North

and West where we find more Negro doctors and

dentists in the large urban centers, there are two

and one-half times as many white dentists and doc

tors as Negro.

“ Law—In 1940 there were 176,475 white and

1,052 Negro lawyers in the U. S. distributed in pro

portion to population as follows:

Section White Negro

U. S___ _______ ...... 670 12,230

North ________ ...... 649 4,000

South ________ ...... 711 30,000

West _________ ...... 699 4,000

Miss. _________ ...... 4,234 358,000

“ There are 18 times as many white lawyers as

Negro lawyers in the country as a whole; 45 times

as many in the South; and 90 times as many in Mis

sissippi. Even in the North and West there are six

times as many white lawyers as Negro. With the

exception of engineering, the greatest disparity is

found in law.” (Italics ours.) * *

f To the nearest hundred or thousand.

* To the nearest hundred or thousand.

15

The professional skills developed through graduate

training are among the most important elements of our

society. Their importance is so great as to be almost self-

evident. Doctors and dentists guard the health of their

people. Lawyers guide their relationships in a complicated

society. Engineers create and service the technology that

has been bringing more and more good to more and more

people. Teachers pass on skills and knowledge from one

generation to another. Social service workers minister to

the needs of the less fortunate groups in society and reduce

the amount of personal hardship, deprivation, and social

friction.

Yet the action of the lower Court in this case, quite

aside from any legal considerations, lends the sanction of

that Court to a series of extra-legal actions by which the

various states have carried on a policy of discrimination in

education. In Oklahoma, the 16 other states and the Dis

trict of Columbia where separate educational facilities for

whites and Negroes are mandatory, the provisions for

higher education for Negroes are so inadequate as to de

prive the Negro population of vital professional services.

The record of this policy of educational segregation and

denial of professional education to Negroes is clear. In

the 17 states and the District of Columbia in 1939-1940 the

following number of states made provisions for the public

professional education of Negro and white students: 17

Profession White Negro

Medicine ______________ ......... . 15 0

Dentistry______________ _______ 4 0

T jaw 16 1

Engineering __________ _______ 17 0

Social service_________ ________ 9 0

Library science _______ ________ 13 1

Pharmacy ___________ _______ 14 0

17 Based on data in National Survey of Higher Education for

Negroes, Vol. II, p. 15.

16

The result has been that the qualified Negro student is

unable to obtain the professional education for which he

may be fitted by aptitude and training.

Other sections of the country, too, practice discrimina

tion against Negroes in professional schools by means of

“ quotas” and other devices.18 But only in the South is

legal discrimination practiced and it is thus in the South

that the Negro population suffers the greatest deprivation

of professional services.

The record is quite clear, and the implications of the

above data are obvious. There is another implication, how

ever, which is not as obvious but is of almost equal impor

tance in the long-range development of the Negro people.

From the ranks of the educated professionals come the

leaders of a minority people. In the course of their daily

duties they transmit their skills and knowledge to the

people they serve. They create by their daily activities

18 “ Wherever young Americans of ‘minority’ races and religions

are denied, by the open or secret application of a quota system, the

opportunity to obtain a medical, law or engineering education, apolo

gists for the system have a standardized justification.

“ In their racial-religious composition, the apologists contend, the

professions must maintain ratios which correspond to those found in

the composition of the whole population. Were the institution of

higher learning left wide open to ambition and sheer merit, they

argue, the professions would be ‘unbalanced’ by a disproportionate

influx of Catholics, Negroes and Jews.

“ Such racial arithmetic hardly accords with our vaunted prin

ciples of democratic equality. In effect it establishes categories of

citizenship. It discriminates against tens of millions of citizens by

denying their sons and daughters a free and equal choice of profes

sion. If a ratio must be imposed on the basis of race, why not on the

pigmentation? Forcing a potentially great surgeon to take up some

other trade makes sense only on the voodoo level of murky prejudice.

It not only deprives the citizen of his legal and human rights but, no

less important, it deprives the country of his potentially valuable ser

vices.”— from “ Religious Prejudices in Colleges,’ ’ by Dan W . Dodson.

The American Mercury (July 1946), p. 5.

17

a better, more enlightened citizenship because they trans

mit knowledge about health, personal care, social relation

ships and respect for and confidence in the law.

The average Negro in the South looks up to the Negro

professional with a respect that sometimes verges on awe.

It is frequently the Negro professional w7ho is able to artic

ulate the hopes and aspirations of his people. The defen-

dants-in-error, in denying to the plaintiff-in-error access to

equal educational facilities on the professional level within

the State, also deny to the Negro population of Oklahoma

equal access to professional services and deprive it of one

of the most important sources of guidance in citizenship.

This denial is not only injurious to plaintiff-in-error, and

to other Negro citizens of the State, but adverse to the

interests of all the citizens of the State by denying to them

the full resources of more than 168,849 Negro citizens.

D. The Requirements of the 14th Amendment Can

Be Met Only Under an Unsegregated Public Edu

cational System.

The above recited data show that equal educational facil

ities are not maintained in those states, including Okla

homa, where segregation is required. More than that it is

impossible for equal facilities to be maintained under a

segregated system. The theory that segregation is consti

tutional as long as the facilities provided for Negroes are

equal to those provided for whites is a proper interpreta

tion of the federal constitution only if the rationale on

which the rule is based is correct. In those areas where

segregation is enforced in education, the states concerned

are least able economically to afford the establishment of

equal facilities in all respects that are required if this

theory is to be complied with. The facts demonstrate that

they could not provide such equal facilities even if they

18

were so disposed to do so. It is clear, therefore, that the

rationale for this “ equal but separate rule” of law is fal

lacious. A fortiori, the theory is erroneous and should be

discarded in light of the actualities of the situation.

Segregation constitutes a denial of the equal protection

of the laws and is violative of the Constitution and the laws

of the United States. Despite the line of cases in support

of the “ separate but equal” theory, this Court is under an

obligation to re-examine the rule and the reasons on which

it is based in the light of present day circumstances and to

adopt and apply a rule which conforms with the require

ments of our fundamental law.

E. Even Under “ Equal But Separate” Doctrine, the

Action of Defendants-in-Error Violated the Four

teenth Amendment.

No provision for the legal education of Negroes has

been made or is being made in the State of Oklahoma.

Plaintiff-in-error, possessing all the scholastic, moral and

legal qualifications therefor, applied for admission to the

only law school maintained by the State for the legal edu

cation of its citizens. Defendants-in-error refused her ad

mission on the grounds that the state policy requires the

separation of white and Negroes in the educational sys

tem in the State of Oklahoma. Plaintiff-in-error contends

that however free Oklahoma may be in adopting and main

taining a policy locally designed to meet its “ racial prob

lems” , this policy must conform to the requirements of the

federal constitution. Since the University of Oklahoma

Law School is the only law school maintained by the State,

plaintiff-in-error must be admitted to said school if the State

is to fulfill its obligation to plaintiff-in-error under the 14th

Amendment and under its own Constitution.

19

This is true under either theory discussed above. Under

the theory of plaintiff-in-error that segregation in Okla

homa’s educational system violates the federal constitu

tion, the maintenance of a school of law for the exclusive

attendance of white persons is unconstitutional. Plaintiff-

in-error and other Negro applicants must be admitted to

such school if they are to enjoy the rights and benefits guar

anteed under the Fourteenth Amendment. Under the

theory of defendants-in-error that segregation does not vio

late our fundamental law, as long as the facilities set aside

for Negroes are equal to those set aside for whites, it is

clear that the State cannot set up a law school exclusively

for whites without at the same time making similar provi

sions for Negroes.19 Since this has not been done in Okla

homa, the right of plaintiff-in-error to be admitted to the

law school of the state university is undenied. The refusal

of defendants-in-error to admit her to the school solely on

the basis of race and color violates her rights under the

Fourteenth Amendment.

II.

The application for a writ of mandamus to compel

the defendant-in-error to admit plaintiff-in-error to the

Law School of the University of Oklahoma was proper

and should have been granted by the court below.

A. Mandamus Should Issue as Prayed For.

The Court below in denying application of plaintiff-in

error for a writ of mandamus relied upon Sharpless v.

Buckles et al., 65 Kan. 838, 70 Pac. 886 (1902); State ex rel.

Hunter v. Winterrowd, 174 Ind. 592, 92 N. E. 650 (1910);

19 Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590 (1936); Mis

souri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938); see also other

cases cited in note 5, supra.

20

Comley ex rel. Rowell v. Boyle, 115 Conn. 406, 162 Atl.

(Conn.) 26 (1932), where the courts in question refused to

make a preliminary determination of the constitutionality

of state statutes before deciding whether a writ of man

damus should issue. The Court in these instances held that

a mandamus action was not proper unless the applicant had

a clear legal right to the thing demanded, and a duty on the

part of the defendant existed to do the acts required in the

absence of any other adequate remedy.

In Sharpless v. Buckles, supra, a state statute permitted

persons engaged in the railway express service who were

outside the district at the time an election took place to

vote in said election and to have their ballots counted along

with those cast in the district. An election was held. Votes

outside the district were cast in accordance with the statute

and counted by the Board of Commissioners along with

other ballots cast. Application was made for a peremptory

writ of mandamus to compel the Board of Commissioners

to reconvene, recount the vote and to exclude the ballots

cast outside the election district. The Court denied the

writ on the grounds that the Board of Commissioners were

merely under a duty to open the returns, determine the

genuineness of the ballots cast and certify the results. The

Court held that the Commissioners had no duty or authority

to determine the constitutionality of the statute permitting

absentee voting by persons engaged in the railway service

and that the Court could not by mandamus action impose

upon officials a duty beyond that which the law established.

In Comley ex rel. Rotvell v. Boyle, supra, zoning regu

lations in the City of Stamford required a person to obtain

a permit to erect any structure within the city limits and

provided that no permit should issue unless the proposed

building complied with the law, ordinances and regulations

21

applicable thereto. The Building Commission was given

authority to vary or modify any provision or regulation of

the Building Code where it was found that it was impossible

to comply with the strict letter of those provisions. Appli

cation was made to build a structure with material ad

mittedly prohibited under the Building Code. Relator

sought to have the Building Commission permit a variation

in the provisions of the Code in order to permit him to

erect the proposed building. This being refused, relator

petitioned for a writ of mandamus to compel the Building

Commission to permit him to erect the building proposed.

The court refused the writ on the grounds that the court

could not disturb the proper exercise of discretion on the

part of public officials, and it was held that mandamus

would not lie except to force a public official to exercise a

mandatory duty and where the party seeking the writ had

a clear legal right to the thing demand and no sufficient

or adequate remedy.20

These cases do not bar the right to writ of mandamus

in this case. Plaintiff-in-error has a clear legal right to

obtain a legal education in the State of Oklahoma as long

as provisions for such education is made for white persons.

Once the state undertakes to provide educational facilities

for white persons, it is under a legal duty to make pro

vision at the same time for the education of Negroes.21 The

constitution and statutes of Oklahoma which require the

20 In State ex rel. Hunter v. Winterrowd, supra, the Court said:

“ The writ will issue . . . as a matter of right, in favor of

a petitioner who shows a clear legal right to the thing de

manded and an imperative duty on the part of respondent to

do the acts required in the absence of any other adequate

remedy.” But compare Welch v. Swasey, 193 Mass. 364,

79 N. E. 745 (1907).

21 Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590 (1936); Mis

souri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) and cases cited

in notes 5 and 8, supra.

separation of the races in the public school system must be

read and interpreted in the light of constitutional require

ments.22 Under any view of the law, as pointed out in the

first part of this brief, the state must admit plaintiff-in

error to the law school of University of Oklahoma if it has

made no other provision for the legal education of Negroes.

Segregation statutes can only be constitutional if equal

facilities are provided. Even under the “ equal but sepa

rate” theory, the state would be under an obligation either

to afford Negroes equal educational facilities in a school

set aside exclusively for them or to admit them to the school

set aside for whites. A state cannot use a segregation

statute as a means of avoiding its mandatory obligation

that Negroes be afforded the equal protection of the laws.

The only adequate remedy herein available for plaintiff-

in-error is the remedy available by the writ of mandamus.

The right of all Negroes in Oklahoma, to a legal education,

accrued and vested when the State established and main

tained the School of Law at University of Oklahoma for

the legal education of whites. Plaintiff-in-error asserted

this right upon her application for admission to School of

Law, University of Oklahoma, and the obligation of the

State to make provision for her legal education became an

immediate obligation which could not be postponed. Plain

tiff-in-error now has a right to a legal education as long as

the State is making provisions for the legal education of

22 Sec. 3, Art. 13 of Oklahoma Constitution provides for impar

tial maintenance of separate schools ; 70 Okla. Stat. 1941, Sec. 363

provides for separate schools for training of teachers; 70 Okla. Stat.

1941, §§451-470 contain penal provisions; 70 Okla. Stat. 1941,

§§ 1591, 1592, 1593 provide for out of state scholarships for Negroes

who desire instruction on any subject taught only in a state insti

tution maintained exclusively for whites. That this type of provision

does not satisfy the constitutional requirements was settled in Mis

souri ex rel. Gaines, supra.

22

23

whites. Having the requisite lawful qualifications, and

there being no law school provided for Negroes, defendants-

in-error were without constitutional or statutory authority

to refuse to admit her to the Law School of the University

of Oklahoma. Whatever doubts might have existed on this

question were resolved by the United States Supreme

Court in 1938 in the case of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v.

Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938).

Oklahoma Statutes, requiring the segregation of the

races in the public school system, at the very least, can

only satisfy the Fourteenth Amendment if implicit in

such statutes is the requirement that the equal facilities be

afforded Negroes in separate schools.23 Barring this, Ne

groes must be admitted to the school set aside for exclusive

attendance of whites. Statutes must be read and inter

preted by the courts in a manner which will save their

constitutionality wherever possible.24 These statutes, there

fore, cannot be regarded as rigid and inflexible prohibitions

against Negroes and whites attending the same schools but

only necessitating separation where Negroes are specifi

cally afforded equal facilities. Public officers of the state,

therefore, are under a duty to admit Negroes to schools set

aside for whites if no school is maintained for Negroes.25

If the statutes in question impose the inflexible duty on

the defendants-in-error not to permit a qualified Negro

applicant to avail himself of the opportunities for educa

23 Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra. Pearson v. Murray,

supra; Ward v. Flood, supra,

24 National Labor Relations Bd. v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp.,

301 U. S. 1 (1936); Blodgett v. Holden, 275 U. S. 142 (1928);

Federal Trade Commission v. American Tobacco Co., 264 U. S. 298

(1924); Panama R. Co. v. Johnson, 264 U. S. 375 (1924); Mis

souri P. R. Co. v. Boone, 270 U. S. 466 (1926) ; Richmond Screw

Anchor Co. v. United States, 275 U. S. 331 (1928).

25 Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra; Pearson v. Murray,

supra.

24

tion afforded by the State in the same institution with

whites, wdiere no such facilities are provided for Negroes,

the statutes clearly fail to meet the minimum requirements

of the Fourteenth Amendment and are unconstitutional.26

Either the defendants-in-error are obligated to admit plain

tiff-in-error to the school of law of Oklahoma University

or the statutes, under which they rely to keep plaintiff-in

error from attending said school, are unconstitutional. No

other conclusion is possible. If the constitutionality of

Oklahoma segregation law are to be sustained, their pro

visions can only apply where equal facilities are afforded

Negroes in separate schools.

B. Prior Demand on Board of Higher Education to

Establish a Law School at Langston University

Is Not a Prerequisite to This Action.

It is contended by defendants-in-error that no applica

tion was made to the Board of Higher Education of the

State for the establishment of a school of law at Langston

University, a college maintained by the State for the educa

tion of Negroes (R. 30).27 That no such application had

been made is one of the agreed statements of fact (R. 43).

26 Pearson v. Murray, supra; Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

supra, and other cases cited in note 5.

27 70 Okla. Stat. 1941 §§ 1451 to 1509, as amended in 1945,

relate to Langston University. § 1451, supra, as amended by

implication in 1945, is as follows: “ The Colored Agricultural and

Normal University of the State of Oklahoma at Langston in Logan

County, Oklahoma. The exclusive purpose of such school shall be

the instruction of both male and female colored persons in the art of

teaching, and the various branches which pertain to a common school

education; and in such higher education as may be deemed advisable

by such board and in the fundamental laws of this state and of the

United States, in the rights and duties of citizens, and in the agri

cultural mechanical and industrial arts.”

25

Such a demand upon this Board did not constitute a pre

requisite to the maintenance of this action.

In the instant case there is no dispute as to the avail

ability of provisions for the legal education of white citizens

of the State desiring same as of the date plaintifif-in-error

duly applied and was denied admission to the first year

class of the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma.

The State, once having established a law school for one

portion of its citizenry, is under a constitutional mandate

to make equal provision for all, Negro as well as white.28

When plaintiff-in-error asserted her right, to a legal edu

cation by seeking admission to the University of Oklahoma,

no greater burdens or duties could be placed upon or re

quired of her than of white persons seeking to afford them

selves of the facilities provided by the State.29 Nor can

it be asserted here that failure of plaintiff-in-error to per

form this additional burden enabled the State to avoid its

plain duty to provide her with legal education on equal

footing with that provided for whites.

28 Cases cited in note 5, supra.

29 “ It is no answer to say that the colored passenger, if sufficiently

diligent and forehanded, can make their reservations so far in advance

as to be assured of first-class accommodations. So long as white

passengers can secure first-class accommodations on the day of travel

and the colored passengers cannot, the latter are subjected to inequali

ties and discrimination because of their race” Mitchell v. United

States, 313 U. S. 80 at 96 (1941).

As stated by the U. S. Supreme Court in a case involving dis

crimination in transportation if he is denied . . . , under

the authority of a state law, a facility or convenience . . . which, under

substantially the same circumstances, is furnished to another . . . ,

he may properly complain that his constitutional privilege has been

invaded” McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 151, 160

(1914).

“ Whatever system it adopts for legal education now must fur

nish equality of treatment now. . . . If those students are to be

offered equal treatment in the performance of the function, they

must, at present, be admitted to the one school provided.” Pearson

v. Murray, supra.

26

The Constitution and laws of the United States and

State of Oklahoma require that equal facilities be afforded

all citizens of the State The duty of making such equal

provisions was delegated to the Board of Regents of Higher

Education. This duty is incumbent upon the Board by

virtue of their office.30 It was not necessary, therefore, that

the plaintiff-in-error make a prior demand upon this Board

to perform its lawful duty before she may request man

damus to obtain her lawful right to a legal education.31

30 Art. 13a, Secs. 1 & 2, Okla. Constitution.

31 “ The argument in support of the proposition that a formal de

mand and refusal must be shown, is based upon the assumption that

the duty here sought to be enforced is of a private nature, affecting

only the right of realtor, the law being, that in such a case a demand

is necessary to lay the foundation for relief by mandamus. If, on

the contrary, the duty . . . is a public duty, resting upon respondent

by virtue of their office, it is equally well settled that no such demand

and refusal are necessary. . . . The duty here sought to be enforced

is not of a private nature, nor is the right demanded by relator

merely an individual right, within the meaning of the rule announced.

By the statutes of this State, the duty of providing schools for the-

education of all children between the ages of six and twenty-one in

their district, is imposed upon respondents. . . . The duty thus im

posed upon respondents is incumbent upon them by virtue of their

office. In such case it has been well said, ‘the law itself stands in

the place of a demand, and the neglect and omission to perform the

duty stands in the place of a refusal, or in other words, the duty

makes the demand, and the omission is the refusal.’ ” Peo. ex rel.

John Pear v. Bd. of Education, 127 111. 613, 625 (1889).

“ Decisions that there must be an express and distinct demand or

request to perform must be confined to such cases (o f a private

nature) where, however, the duty is of a purely public nature . . . ,

and where there is no one person upon whom either a right or duty

devolves to make a demand or performance and express demand or

refusal is not necessary.” Merrill, “ Law of Mandamus” (1892) pp.

277 and 278.

“ Whatever public officers are empowered to do for the benefit of

private citizens the law makes it their duty to perform whenever

public interest or individual rights call for the performance of that

duty.” United States v. Saunders, 124 Fed. 124, 126 (C. C. A. 8th,

1903); see also Bd. of County Commrs. v. New Mexico ex rel. Coler,

215 U. S. 296, 303 (1909); Northern Pacific RR Co. v. Washing

ton, 142 U. S. 492, 508 (1891).

27

It is axiomatic that the law will not require an individual

to do a vain and fruitless act before relief from a wrong

will be granted.32 This general rule applies in the instant

case as the demand alleged to be prerequisite to the grant

ing of relief would have been unavailing, fruitless and

vain 33 as after the filing of this cause the Board of Regents

of Higher Education, having knowledge thereof, met and

32 “ The law does not require a useless thing . . . the law never

demands a vain thing, and when conduct and action of the officer is

equivalent to a refusal to perform the duty desired, it is not neces

sary to go through the useless formality of demanding its perform

ance.” Merrill, “ Law of Mandamus” (supra) at 279.

“Equity does not insist on purposeless conduct and disregards

mere formalities,” 49 Am. Jur. 167.

“ Demand is not, of course, necessary where it is manifest it would

be but an idle ceremony.” Ferries, “ Law of Extraordinary Rem

edies” (1926), p. 228. City o f Port Townsend v. First Natl. Bank,

241 Fed. 32 (C. C. A. 9th, 1917) ; McGUlvray Const. Co. v. Hos-

kins, 54 Cal. App. 636, 202 Pac. 677 (1921); Pugsley v. Sellmeyer,

150 Ark. 247, 250 S. W . 538 (1923); United States v. Saunders, 124

Fed. 124 (C. C. A. 8th, 1903).

“ . . . if the defendant has shown by his conduct that he does not

intend to perform the act . . . , it would be a work of supererogation

to require that a demand should be made for its performance. Here

the only effect of issuing the writ of mandamus is to require the

authorities of the town to do what by law they are obliged to do . . .

it seems . . . to be proper and reasonable and nothing more than the

Relator has a right to claim of the court, that an order should be

issued requiring them to do what the law says, in such a case as this,

they must do.” United States ex rel. Aetna Ins. Co. v. Bd. etc. o f

Town of Brooklyn, 8 Fed. 473, 475 (N. D. 111. 1881).

33 Plaintiff’s Exhibit “ 2”— the Board empowered to make sepa

rate provision for Relator or other colored citizens had no funds

available for this purpose. Even if they had available funds it would

have been many months before such a school could have been estab

lished (R. 43).

The fruitlessness of such a demand receives support from the

failure of this Board to take any such action subsequent to having

notice of Relator’s desire for a legal education had they intended to

fulfill their legal obligation to make provisions for Negro students

desiring legal education by establishing a separate school. Such

should have been done immediately upon having notice thereof

brought to their attention (R. 43).

28

considered the questions involved therein; had no unallo

cated funds in its hands or under its control at that time

with which to open up and operate a law school and has

since made no allocation for that purpose; that in order to

open up and operate a law school for Negroes in this State,

it will be necessary for the Board to either withdraw exist

ing allocation, procure moneys, if the law permits, from the

Governor’s contingent fund, or make an application to the

next Oklahoma legislature for funds sufficient not only to

support the present institutions of higher education but to

open up and operate said law school; and that the Board

has never included in the budget which it submits to the

Legislature an item covering the opening up and operation

of a law school in the State for Negroes and has never been

requested to do so (R. 43).

Conclusion.

For the reasons hereinbefore discussed plaintiff-in-error

asserts that her constitutional right to equal protection of

the laws can only be protected by her admission to the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma and that under any

view of the constitutional principles involved, this conclu

sion is inescapable. Her rights to a legal education now,

and not at some future time, is the only issue before this

Court. That right can only be enforced by the issuance of

the writ prayed for in her petition to compel defendants-in-

error to admit her to the School of Law of Oklahoma

University.

29

W herefore it is respectfully submitted that the judg

ment of the Court below is in error and should be reversed.

A mos T. Hall

107 V2 N . Greenwood Avenue

Tulsa, Oklahoma

T hurgood Marshall

Robert L. Carter

20 West 40th Street

New York, N. Y.

Attorneys for Plaintiff-in-error

F ranklin H. W illiams

New York, N. Y.

Of Counsel

«3 g g t o 212 [5471]

Lawyers Press, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C .; ’Phone: BEekraan 3-2300

S U P R E M E CO URT OF T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 369

ADA LOIS SIPUEL,

vs.

Petitioner,

BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

OKLAHOMA, GEORGE L. CROSS, MAURICE H.

MERRILL, GEORGE WADSACK and ROY GIT-

TINGER,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI AND BRIEF

IN SUPPORT THEREOF, TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA

R obert L. Carter,

Of Counsel.

A mos T. H all,

T htjrgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

' r ’ I.

.

. v ' ■ ; : / •' -

S , " W f ‘ ' ;• ■

k ̂

INDEX

S ubject I ndex

Page

Petition for writ of certiorari..................................... 1

Statement of the constitutional problem pre

sented ................................................................. 2

The salient fa c t s .................................................... 3

Question presented................................................ 5

Reason relied on for allowance of the writ.......... 6

Conclusion .............................................................. 6

Brief in support of petition ......................................... 7

Opinion of court below........................................... 7

Jurisdiction ............................................................ 7

Statement of the case................... •........................ 8

Error below relied upon here............................... 8

Argument .............................................................. 8

The decision of the Supreme Court of Okla

homa is inconsistent with and directly con

trary to the decision of this Court in

Gaines v. Canada ....................................... 8

Conclusion .............................................................. 19

Cases Cited

Canty v. Alabama, 309 U. S. 629................................. 6

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337................................. 6

White v. Texas, 309 U. S. 631......................................... 6

Statutes Cited

Constitution of Oklahoma, Art. 13A ......................... 15,18

Federal Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment.......... 3

Judicial Code, Sec. 237(b) as amended....................... 1, 7

Missouri Revised Statutes— 1929, Section 9618 .... 22

Missouri Revised Stat. of 1939, Chapter 72, Art. 2,

Section 10349 (R, S. 1929, Sec. 9216, Rev. Stat.

Mo. 1939) ................................................................... 11,22

Oklahoma Stat. 1941, Title 70, Section 1451.............. 14, 21

Oklahoma Stat. 1945, Title 70, Section 1451b.............. 15, 21

—2585

t

S U P R E M E EDURT DF T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 369

ADA LOIS SIPUEL,

vs.

Petitioner,

BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

OKLAHOMA, GEORGE L. CROSS, MAURICE H.

MERRILL, GEORGE WADSACK and ROY GIT-

TINGER,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

Petitioner, Ada Lois Sipuel, invokes the jurisdiction of

this Court under Section 237b of the Judicial Code (28

U. S. C. 344b) as amended February 13, 1925, and respect

fully prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review the judg

ment of the Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma (R.

61), affirming the judgment of the District Court of Cleve

land County denying petitioner’s application for a writ of

lc

2

mandamus to compel respondents to admit her to the first

year class of the law school of the University of Oklahoma.

Statement of the Constitutional Problem Presented

Petitioner is a citizen and resident of the State of Okla

homa. She desires to study law and to prepare herself for

the practice of the legal profession. Pursuant to this aim

she applied for admission to the first year class of the

School of Law of the University of Oklahoma, a public in

stitution maintained and supported out of public funds and

the only public institution in the State offering facilities for

a legal education. Her qualifications for admission to this

institution are undenied, and it is admitted that petitioner,

except for the fact that she is a Negro, would have been ac

cepted as a first year student in the law school of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma, which is the only institution of its

kind petitioner is eligible to attend.

Petitioner applied to the District Court of Cleveland

County for a writ of mandamus against the Board of

Regents, George L. Cross, President, Maurice R. Merrill,

Dean of the Law School, Roy Gittinger, Dean of Admissions

and Roy Wadsack, Registrar to compel her admission to the

first year class of the school of law on the same terms and

conditions afforded white applicants seeking to matriculate

therein (R. 2). The writ was denied (R. 21), and on appeal

this judgment was affirmed by the Supreme Court of the

State of Oklahoma on April 29, 1947 (R. 35). Petitioner

duly entered a motion for rehearing (R. 54), which was

denied on June 24, 1947 (R. 61). Whereupon petitioner

now seeks from this Court a review and reversal of the

judgment below.

The action of respondents in refusing to admit petitioner

to the school of law was predicated on the ground (1) that

such admission was contrary to the constitution, laws and

3

public policy of the State; (2) that scholarship aid was

offered by the State to Negroes to study law outside the

State, and; (3) that no demand had been made on the

Board of Kegents of Higher Education to provide such legal

training at Langston University, the State institution af

fording college and agricultural training to Negroes in the

State.

In this Court petitioner reasserts her claim that the re

fusal to admit her to the University of Oklahoma solely

because of race and color amounts to a denial of the equal

protection of the laws guaranteed under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution in that the State

is affording legal facilities for whites while denying such

facilities to Negroes.

The Salient Facts

The facts in issue are uncontroverted and have been

agreed to by both petitioner and respondents (R. 22-25).

The following are the stipulated facts:

The petitioner is a resident and citizen of the United

States and of the State of Oklahoma, County of Grady and

City of Chicakasha, and desires to study law in the School

of Law in the University of Oklahoma for the purpose of

preparing herself to practice law in the State of Oklahoma

(R. 22).

The School of Law of the University of Oklahoma is the

only law school in the State maintained by the State and

under its control (R. 22).

The Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma is

an administrative agency of the State and exercises over-all

authority with reference to the regulation of instruction and

admission of students in the University of Oklahoma. The

University is a part of the educational system of the State

and is maintained by appropriations from public funds

4

raised by taxation from the citizens and taxpayers of the

State of Oklahoma (E. 22-23).

The School of Law of the Oklahoma University specializes

in law and procedure which regulates the government and

courts of justice in Oklahoma, and there is no other law

school maintained by public funds of the State where the

petitioner can study Oklahoma law and procedure to the

same extent and on an equal level of scholarship and in

tensity as in the School of Law of the University of Okla

homa. The petitioner will be placed at a distinct disad

vantage at the bar of Oklahoma and in the public service

of the aforesaid State with respect to persons who have had

the benefit of the unique preparation in Oklahoma law and

procedure offered at the School of Law of the University

of Oklahoma, unless she is permitted to attend the afore

said institution (E. 23).

The petitioner has completed the full college course at

Langston University, a college maintained and operated by

the State of Oklahoma for the higher education of its Negro

citizens (E. 23).

The petitioner made due and timely application for ad

mission to the first year class of the School of Law of the

University of Oklahoma on January 14, 1946, for the semes

ter beginning January 15, 1946, and then possessed and still

possesses all the scholastic and moral qualifications required

for such admission (E. 23).

On January 14, 1946, when petitioner applied for admis

sion to the said School of Law she complied with all of the

rules and regulations entitling her to admission by filing

with the proper officials of the University an official tran

script of her scholastic record. The transcript was duly

examined and inspected by the President, Dean of Admis

sion and Eegistrar of the University (all respondents

herein) and was found to be an official transcript entitling

5

her to admission to the School of Law of the said University

(R. 23).

Under the public policy of the State of Oklahoma, as

evidenced by the constitutional and statutory provisions

referred to in the answer of respondents herein, petitioner

was denied admission to the School of Law of the University

of Oklahoma solely because of her race and color (R. 23-24).

The petitioner, at the time she applied for admission to

the said school of the University of Oklahoma, was and is

now ready and willing to pay all of the lawful charges, fees

and tuitions required by the rules and regulations of the said

University (R. 24).

Petitioner has not applied to the Board of Regents of

Higher Education to prescribe a school of law similar to

the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma as a part

of the standards of higher education of Langston University

and as one of the courses of study thereof (R. 24).

It was further stipulated between the parties that after

the filing of this case, the Board of Regents of Higher

Education had notice that this case was pending and met and