Williams v. City of New Orleans Brief for Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

November 16, 1995

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Williams v. City of New Orleans Brief for Amici Curiae, 1995. c4243f3c-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c2c827e-a420-414f-9daa-5ea062032c39/williams-v-city-of-new-orleans-brief-for-amici-curiae. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

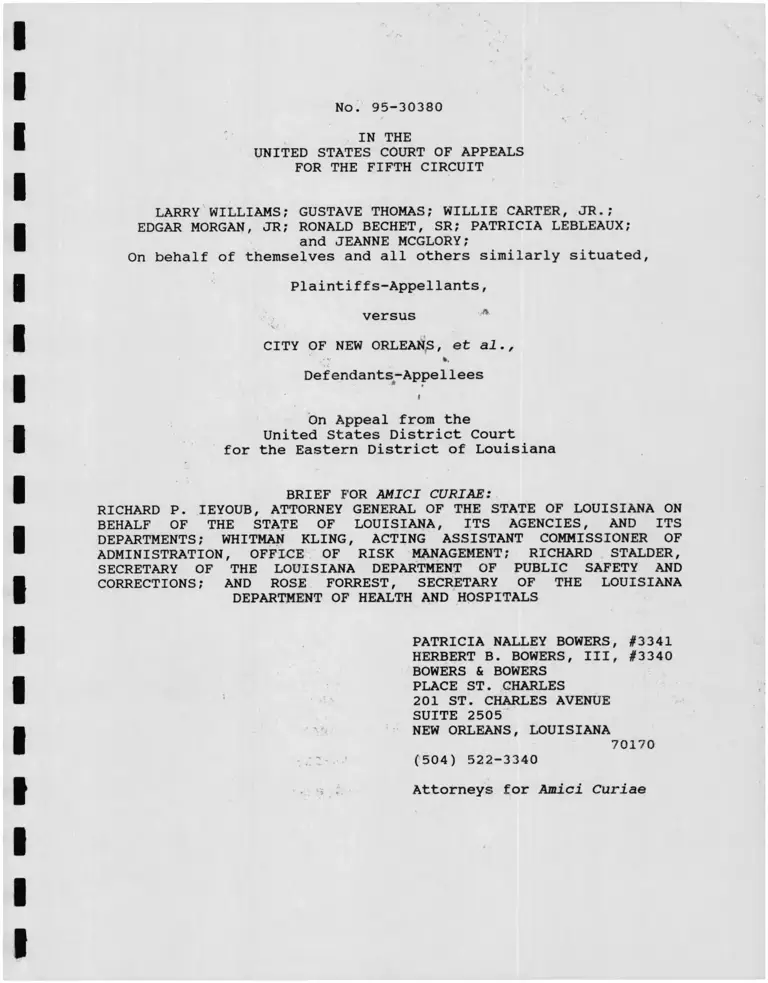

No. 95-30380

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

LARRY WILLIAMS; GUSTAVE THOMAS; WILLIE CARTER, JR.;

EDGAR MORGAN, JR; RONALD BECHET, SR; PATRICIA LEBLEAUX;

and JEANNE MCGLORY;

On behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, et al.,

v fc.

Defendants-Appellees

On Appeal from the

United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE:

RICHARD P. IEYOUB, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE STATE OF LOUISIANA ON

BEHALF OF THE STATE OF LOUISIANA, ITS AGENCIES, AND ITS

DEPARTMENTS; WHITMAN KLING, ACTING ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER OF

ADMINISTRATION, OFFICE OF RISK MANAGEMENT; RICHARD STALDER,

SECRETARY OF THE LOUISIANA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY AND

CORRECTIONS; AND ROSE FORREST, SECRETARY OF THE LOUISIANA

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HOSPITALS

PATRICIA NALLEY BOWERS, #3341

HERBERT B. BOWERS, III, #3340

BOWERS & BOWERS

PLACE ST. CHARLES

201 ST. CHARLES AVENUE

SUITE 2505

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA

70170

(504) 522-3340

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

No. 95-30380

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

LARRY WILLIAMS; GUSTAVE THOMAS? WILLIE CARTER, JR.;

EDGAR MORGAN, JR; RONALD BECHET, SR; PATRICIA LEBLEAUX;

and JEANNE MCGLORY;

On behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

On Appeal from the

United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE:

RICHARD P. IEYOUB, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE STATE OF LOUISIANA ON

BEHALF OF THE STATE OF LOUISIANA, ITS AGENCIES, AND ITS

DEPARTMENTS; WHITMAN KLING, ACTING ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER OF

ADMINISTRATION, OFFICE OF RISK MANAGEMENT; RICHARD STALDER,

SECRETARY OF THE LOUISIANA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY AND

CORRECTIONS; AND ROSE FORREST, SECRETARY OF THE LOUISIANA

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HOSPITALS

PATRICIA NALLEY BOWERS, #3341

HERBERT B. BOWERS, III, #3340

BOWERS & BOWERS

PLACE ST. CHARLES

201 ST. CHARLES AVENUE

SUITE 2505

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA

70170

(504) 522-3340

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

-l-

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned counsel of record for amici curiae certifies

that the following listed persons, amici curiae or their counsel,

have an interest in the outcome of this appeal insofar as it is

anticipated that the Court's opinion on this matter may establish

a standard for the Fifth Circuit and the district courts who must

follow its precedent regarding when it is appropriate to pay out of

town hourly rates as opposed to the hourly rates prevailing in the

community in which the court hearing the matter sits. The

representations are made in order that judges of this Court may

evaluate possible disqualifications or recusal:

Amici Curiae:

Richard P. Ieyoub, Attorney General for the State of Louisiana

appearing on behalf of the State of Louisiana, its agencies, and

its departments; Whitman Kling, Acting Assistant Commissioner for

the Division of Administration of the State of Louisiana, Office of

Risk Management; Richard Stalder, Secretary of the Louisiana

Department of Corrections; and Rose Forrest, Secretary of the

Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals.

Counsel for Amici Curiae:

Patricia Nalley Bowers and Herbert B. Bowers, III1

lPlease note that the same counsel were special counsel to the

defendants-appellees, the City of New Orleans, et al., in the fees

litigation in the district court which is the subject of this

appeal. However, Mr. and Mrs. Bowers withdrew as counsel of record

-ii-

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

INSIDE TITLE PAGE...................................................i

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS................................ ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS..................................................iv

TABLE OF CASES, STATUES, AND OTHER AUTHORITIES................... V

STANDARD OF REVIEW AND BURDEN OF PROOF............................1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT................................................ 2

ARGUMENT............................................................ 3

CONCLUSION......................................................... 19

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE............................................ end

for the City on the fees matter effective September 27, 1994

[Record Document 826 (Sometimes referred to hereinafter as

r .D.___)] prior to Judge Sear issuing the January 27, 1995 Minute

Entry (R.D. 828) which forms the basis of the Judgment (R.D. 833)

and ultimately this appeal. Thus, Mr. and Mrs. Bowers are listed

both on this certificate as counsel for amicus curiae (Attorney

General Richard Ieyoub and related parties) and on the certificate

of interested persons provided by the Plaintiffs-Appellants,

Williams, et al. as special counsel to the City of New Orleans.

Both the current counsel for the City of New Orleans, et al. ,

Annabelle H. Walker, and counsel for the Plaintiffs-Appellants,

Charles Stephen Ralston, were contacted prior to the filing of this

amici curiae Brief and have no objection to Mr. and Mrs. Bowers

acting as counsel for amici curiae in this Court.

-in -

TABLE OF CASES, STATUTES, AND OTHER AUTHORITIES

Aguillard, et al. v. Edwards, et al. , 778 F.2d 225 (5th Cir.

1985)...............................................................18

American Booksellers Ass'n, Inc. v. Hudnut, 650 F.Supp. 324, 328

(S.D. Ind. 1986)................................................... 10

Avalon Cinema Corporation v. Thompson, 689 F.2d 137, 140-41 (1982)

Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886, 895, 104 S.Ct. 1541, 1547, n.ll

(1984)...............................................................7

Brooks v. Georgia State Bd. of Elections, 997 F .2d 857 (1993).. 1,5

Chrapliway v. Uniroyal, Inc., 670 F.2d 760, 767-69 (1982)...... 7

Copper Liquor, Inc. v. Adolph Coors Co., 684 F.2d 1087, 1094 (5th

Cir. 1982).......................................................... 1

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 EPD f9444 at 5048 (C.D. Cal.

1974)................................................................9

Doe, et al. v. Foti, et al. , E.D. La. #93-1227................. 18

Donaldson v. O'Connor, 454 F.Supp. 311, 314 (N.D. Fla. 1978)....5

Gates v. Deukmejian, 987 F.2d 1392, 1405 (1992)................. 7

Goff v. Texas Instruments, Inc., 429 F.Supp. 973, 978 (N.D. Tex

1977).............................................................. 11

Grendel's Den, Inc. v. Larkin, 749 F.2d 945 (1st Cir. 1984)

Hamilton, et al. v. Morial, et al. , E.D. La. # 69-2443..........17

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d 714, 718 (5th Cir.

1974).............................................................5,9

Louisville Black Police Off. v. City of Louisville, 700 F.2d 268,

277-78 (1983)...................................................... 7

-IV-

^/Maceira v. Pagan, 698 F.2d 38,40, (1983)......................... 6

National Wildlife Federation v. Hanson, 859 F.2d 313, 317-18

(1988).............................................................. 6

Polk v. New York State Dept, of Corr. Services, 722 F.2d 23, 25

L (1983).............................................................. 6

'Public Interest Group of N.J. v. Windall, 51 F.3d 1179, 1184 (3rd

Cir. 1995)........................................................ 1/6

̂Ramos v. Lamm, 713 F.2d 546, 555 (1983)........................... 7

Reazin v. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas, 899 F.2d 951, 982-

83 (1990)........................................................... 8

Riddell v. National Democratic Party, 712 F.2d 165 (5th Cir.

1983)................................................................1

Standford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680, 682 (N.D. Cal. 1974)...9

Sojourner, et al. v. Edwards, et al., E.D. La. #91-2447......... 18

Swann v. Charlotte- Mecklenburg Board of Education, 66 F.R.D. 483,

486 (W.D.N.C. 1975)................................................ 9

Todd Shipyards Corp. v. Turbine Service, Inc., 592 F. Supp. 380,

392 (E.D. La. 1984)................................................ 5

Williams, et al. v. City of New Orleans, et al., 543 F.Supp. 662

(E.D. La. 1982)....................................................17

La. R.S. 13:5108.1 et seq..........................................5

-v-

STANDARD OF REVIEW AND BURDEN OF PROOF

Amici curiae agree with appellees, the City of New Orleans, et

al. that the standard of review for an ''award of attorneys' fees is

"abuse of discretion" [Riddell v. National Democratic Party, 712

F .2d 165, 168 (5th Cir. 1983); Copper Liquor, Inc. v. Adolph Coors

Co., 684 F . 2d 1087, 1094 (5th Cir. 1982)], with subsidiary fact

findings being reversible "only if clearly erroneous". Copper

Liquor, supra, at 1094. But see also Public Interest Group of N.J.

v. Windall, 51 F.3d 1179, 1184 (3rd Cir. 1995):

The standards the district court should use in

calculating an attorney fee award are legal guestions

subject to plenary review.

Because it also impacts on the formulation of a rule by this

circuit regarding out of town/local rates, amici curiae also point

out that the Supreme Court has held that the burden of proof

regarding the reasonableness of hourly rates belongs to the fee

seeking attorneys:

In seeking some basis for a standard, courts

properly have reguired prevailing attorneys to justify

the reasonableness of the reguested rate or rates.

Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886, 895,n.11, 104 S.Ct. 1541,

1547,n.11 (1984)

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

There is no test in this Circuit for when, if ever, it is

appropriate to pay out of town (non-forum) rates to fees seeking

counsel. The Supreme Court has told us only that the rates should

be those of the "relevant community" without telling us which

community (location of the court or counsel's office) is relevant.

-1-

The other circuits have generally established rules that allow the

use of out of town rates if it can be demonstrated that local

counsel was not available to do the job, either because they didn't

want to do so, didn't have enough time, didn't have enough

experience, or couldn't fund or staff the case.

However, only the Tenth Circuit has strictly interpreted its

test by holding that, in all but the most unusual cases, competent

local counsel should routinely be available. Amici suggest that

all attorneys should be limited to rates prevalent in the forum

since there is nothing in the fee acts, and particularly the civil

rights act and its congressional history, to suggest otherwise.

In the alternative, amici suggest that this Circuit adopt a

rule somewhat similar to the Tenth Circuit, making it clear that

the use of out of town or out of state rates should be the

exception rather than the rule with such rates being allowed only

if plaintiff can actually show that he approached numerous local

counsel and was turned down over and over, making it impossible for

him to hire "competent" local counsel. Such a rule would negate

the implication of the plaintiffs herein that a plaintiff should be

able to contact out of town counsel he considers to have a special

expertise just because he wants the best, the brightest, and the

most experienced in the country.

Furthermore, the rule eventually formulated by this Circuit

needs to take into account litigation by the national policy

advocacy groups such as the group seeking fees in the instant case.

These groups gravitate to high visibility, controversial class

actions like this one. In addition, in many of the cases handled

-2-

by these national groups, at least in Louisiana, little or no

actual effort is made by plaintiffs to obtain qualified local

counsel and the group tries to meet the tests established by the

other circuits by putting on testimony of the local plaintiff civil

rights bar that seeking local counsel would have been a vain and

useless act. Lastly, many of the cases handled by these national

groups are "targeted" by them to advance their particular agenda,

to gain publicity, to make money, or for any of a variety of

reasons. The facts of this case confirm that analysis.

Amici curiae contend that these groups do not merit special

rules. While they certainly should be welcome to come to Louisiana

and press their agenda if they so desire, they, like any other out

of town counsel, should be held to strict proof that prior to the

plaintiffs' first contact with the advocacy group, he tried on

numerous occasions to retain "competent" local or in state and was

unable to do so.

Accordingly, in order to help protect the public fisc of

Louisiana, amici curiae respectfully request that this Court

establish a "bright line" test along the lines discussed herein for

the awarding of out of town rates, if any, to fees seeking counsel.

ARGUMENT

No standard exists in this Circuit regarding when, if ever, it

is appropriate to pay out of town hourly rates to fees seeking

counsel as opposed to the local hourly rates of the community in

which the district court hearing the matter sits. Amici curiae

(Richard P. Ieyoub, Attorney General for the State of Louisiana

-3-

appearing on behalf of the State of Louisiana, its agencies, and

its departments; Whitman Kling, Acting Assistant Commissioner for

the Division of Administration of the State of Louisiana, Office of

Risk Management; Richard Stalder, Secretary of the Louisiana

Department of Corrections; and Rose Forrest, Secretary of the

Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals) have a substantial

interest in the establishment of such a standard and the content of

same for the following reasons.

As this Court is aware, the State of Louisiana and its various

agencies, departments, subdivisions, etc., generally through the

legal fiction of naming such personages as the Governor or the

secretaries (CEO's) of the various departments, are sued on a daily

basis in the several federal courts situated in Louisiana under a

variety of theories, most of which employ as one form of remedy the

use of attorneys' fees to prevailing plaintiffs. The vast majority

of these suits are brought on behalf of the plaintiff or plaintiffs

by attorneys who reside and practice law in the same locality where

the court hearing the matter sits.

However, in any given year, a certain number of these suits

are initially filed or end up being substantially handled by out of

town counsel. While, of course, there are exceptions, the suits

filed and/or handled by out of town counsel tend to be high profile

class actions which generate substantial amounts of publicity and

revolve around resolution of currently controversial and hotly

contested issues. Examples of such litigation which come readily

to mind, in addition to the case at bar, are abortion regulation,

prayer in school, state aid to non-public schools, scientific

-4-

creationism, conditions of confinement in correctional

institutions, and reapportionment.

In the event that the plaintiffs win such litigation, their

attorneys apply for fees and the Louisiana public fisc is affected

through payment of attorneys' fees judgments by the Division of

Administration, Office of Risk Management, pursuant to Louisiana

statues regarding indemnification. (La. R.S. 13:5108.1 et seg. )

Since the use of out of town rates, particularly for counsel from

such cities as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and

New York, can have the effect of doubling or tripling a fee award,

the impact on the public fisc is significant. Accordingly, amici

curiae present the following arguments in regard to the formulation

in this Circuit of a standard for the imposition of out of town

rates.

The U.S. Supreme Court has limited its guidance in this area

to commenting that hourly rates should be the "prevailing market

rates in the relevant community". Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886,

895, 104 S.Ct. 1541, 1547 (1984). Unfortunately, the Supreme Court

has yet to announce what the "relevant community" is and this Court

has not addressed the problem since Blum.2 Many of the other

2The Northern District of Florida, in an old opinion, did

analyze this Court's position on the local/out of town rate issue,

looking at Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d 714

(5th Cir. 1974) and both pre- and post-Johnson cases. See

Donaldson v. O'Connor, 454 F.Supp. 311, 314 (N.D.Fla. 1978).

Similarly, the Eastern District of Louisiana, relying on precedent

from outside this circuit, stated in dicta that an exception to the

local rate rule may exist when particular counsel is required, but

the issue was not raised on appeal. See Todd Shipyards Corp. v.

Turbine Service, Inc., 592 F.Supp. 380, 392 (E.D.La. 1984), aff'd

in part and remanded on other grounds, 763 F .2d 745 (5th Cir.1985,

reh'g en banc denied, 770 F.2d 164 (5th Cir. 1985). However, no

modern, post-Blum standard appears to exist in this circuit.

-5-

circuits, while holding that rates from the community in which the

district court sits are generally appropriate, have created

exceptions to this rule using a variety of formulations:

First Circuit: Maceira v. Pagan, 698 F.2d 38, 40 (1983)(Local

rates appropriate if an ordinary case requiring no specialized

abilities not amply reflected among local lawyers; out of town

rates appropriate if no evidence that lawyers with same degree of

experience and specialization available in locale.)

Second Circuit: Polk v. New York State Dept, of Corr.

Services, 722 F.2d 23, 25 (1983)(Dicta recognizing that exceptions

to local rates have been made by other circuits when special

expertise of counsel from distant district is required.)

Third Circuit: Public Interest Group of N.J., Inc. v. Windall,

51 F .3d 1179, 1185-88 (1995)(Affirming use of entire state of New

Jersey as relevant market based on 1)evidence that few Southern New

Jersey firms were willing to represent plaintiffs, 2)lack of any

evidence from which the geographic boundaries of a southern New

Jersey Market could be inferred, and 3)evidence that lawyers from

entire state routinely appeared in that district which covered

entire state, while commenting that its Task Force on attorneys'

fees recommended "forum rate rule" with exceptions for special

expertise from distant district or local counsel unwilling to

handle.)

Fourth Circuit: National Wildlife Federation v. Hanson, 859

F . 2d 313, 317-18 (1988) (Use of out of town rates appropriate

because local counsel not available and Washington, D.C. was

closest locality available with appropriate counsel, thereby making

-6-

it reasonable for plaintiffs to choose Washington counsel.)

Sixth Circuit: Louisville Black Police Off. v. City of

Louisville, 700 F.2d 268, 277-78 (1983)(Use of local rates for

Legal Defense Fund out of New York [sometimes referred to

hereinafter as LDF] because attorneys had not been in private

practice in New York so as to establish their New York marketplace

rate while commenting that l)due to district court's discretion it

is free to look to national market, area of specialization market

or any other market appropriate in order to compensate fairly, and

2) organization does not get to choose its rate by choosing its

headquarters city.)

Seventh Circuit: Chrapliwy v. Uniroyal, Inc., 670 F.2d 760,

767-69 (1982)(Court may question out of town billing rate if

similar services available locally at lower rate or if party did

not act reasonably in seeking out of town counsel.)

Eighth Circuit: Avalon Cinema Corporation v. Thompson, 689

F . 2d 137, 140-41 (1982)(While local rate normally correct, out of

town rates may be used if plaintiff can show that he has been

unable through diligent good faith efforts to retain local

counsel.)

Ninth Circuit: Gates v. Deukmejian, 987 F.2d 1392, 1405

(1992)(Recognizing out of town rates as exception to forum rates

when local counsel unwilling or unable to handle case due to lack

of experience, expertise, or specialization to properly handle

case.)

Tenth Circuit: Ramos v. Lamm, 713 F.2d 546,555 (1983)( Local

rates should apply in all but the most unusual circumstances,

-7-

because major cities have substantial number of lawyers to handle

all but most unusual civil rights cases and finding that standard

not met in this comprehensive class action challenge to virtually

all conditions of confinement in a Colorado prison reguiring a five

week trial, appeal, and remand) and Reazin v. Blue Cross and Blue

Shield of Kansas, 899 F.2d 951, 982-83(1990)(wherein for first

time Tenth Circuit upheld unusual circumstances sufficient for out

of town rates up to $40 an hour over local rates where district

court found "not a lawyer or firm in town could have devoted to

this case the timely expertise, experience, and manpower put forth

by" out of town counsel(Ten months filing to trial for case that

reguired 134 page opinion).)

Eleventh Circuit: Brooks v. Georgia State Bd. of Elections,

997 F . 2d 857 (1993)(Recognizing exception to forum rule because

district court's finding that there were no local attorneys

familiar with voting rights litigation was not clearly erroneous)

Thus, it can be seen that the other circuits, when taken

together, have generally found that in order to promote the goal of

private attorneys general enforcing the civil rights legislation,

out of town rates may be used when plaintiff can demonstrate that

local counsel was not available to do the job that needed to be

done, either because local counsel didn't want to handle the case,

didn't have enough time to handle it, didn't have the appropriate

expertise to handle it, or couldn't fund or staff it. However, the

Tenth Circuit has apparently stood alone in mandating that district

courts take into account that civil rights litigation is now

extremely commonplace and, accordingly, that there should be very

-8-

few findings, especially in large cities, that plaintiff, having

made good faith efforts, was unable to find local counsel available

for the case.

Amici curiae would suggest that using the Blum "relevant

community" as anything other than the forum community is not

supported by the Congressional history of the various fee award

statutes and, in particular, of 42 U.S.C. §1988. Out of the four

cases cited by the Senate Report in regard to §1988 as correctly

awarding attorneys' fees, three do not treat the issue of out of

town/local rates at all: Standford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680,

682 (N.D.Cal. 1974); Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 EPD f9444,

at 5048 (C.D.Cal. 1974); and Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 66 F.R.D. 483, 486 (W.D.N.C. 1975). The fourth,

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d 714, 718 (5th Cir.

1974) provides only the admonition that the fee for similar work in

the community should be considered, but does not define what the

relevant "community" is.

However, in the alternative, if this Court chooses to follow

the lead of the other circuits and establish a similar rule, amici

curiae would suggest that the rule of the Tenth Circuit is the most

appropriate in that it makes clear that l)the award of out of town

rates is to be the exception as opposed to the rule, and 2)the

plaintiff must make a substantial showing that there was no capable

local attorney who could have and would have handled the case for

him. Such a rule would discredit the concept implied by the

Legal Defense Fund in its brief on behalf of plaintiffs that a

plaintiff is justified in seeking out of town/national organization

-9-

counsel without making a bona fide effort to find local counsel

simply because the organization has a reputation for handling such

cases. (LDF brief at p. 20, n. 7) The plaintiffs have cited no

support for this proposition and amici are aware of only one case

which treats the issue. In American Booksellers Ass'n, Inc. v.

Hudnut, 650 F.Supp. 324, 328 (S.D.Ind. 1986), the court approved

out of town rates on the basis of the alleged national expertise of

the Finley Kumble firm out of New York and on the basis that Finley

Kumble had been plaintiffs' routine counsel in such matters for

over eight years.

Amici assume for sake of argument herein that such an

"institutional expertise" was established by LDF. But see the

Third Memorandum of City Defendants in Opposition to Plaintiffs'

Motion for Attorneys' Fees, R.D. 823 at pages 35-38 regarding Mr.

Sherwood and Ms. Reed (hereinafter City's 3rd Memo at ___).

Amici contend that plaintiffs should not be entitled to turn

to, and expect the losing defendants to pay for, the best and

brightest lawyers in the country. Rather, the standard should be

that plaintiffs are entitled to competent counsel. The intent of

Congress in establishing the civil rights fee statute was to see

that all persons, regardless of their ability to pay counsel, would

be able to have their constitutional civil rights protected.

Similarly, the principle has been established that those accused of

crime are entitled to counsel so as to protect their precious right

of liberty. In this regard, there have been no holdings that every

criminal defendant is entitled to the best and brightest criminal

attorneys in the country. Accordingly, there can be no rational

-10-

ruling that the protection of a plaintiff's constitutional civil

rights, which while certainly important do not normally reach the

same level of importance as the right to liberty, mandates a higher

level of counsel competence than that provided for the indigent

accused.

The First Circuit has addressed this concept within the

context of highly publicized and controversial lawsuits such as the

one at bar, although in regard to the number of hours, not the

appropriate hourly rate. In Grendel's Den, Inc. v. Larkin, 749

F .2d 945 (1st Cir. 1984), Judge Coffin, writing for the panel,

found that Harvard constitutional scholar and professor, Lawrence

Tribe, had spent a reasonable amount of time on the initial portion

of the case, but thereafter:

...[t]he early economy of effort and careful focus upon

only what was necessary was lost in the heat and

excitement of litigating an interesting First Amendment

case...[t]he basic assumption underlying Grendel's fee

application: [was] that the standard of service to

rendered and compensated is one of perfection, the best

that illimitable expenditures of time can achieve. But

just as a criminal defendant is entitled to a fair trial

and not a perfect one, a litigant is entitled to

attorney's fees under 42 U.S.C. §1988 for an effective

and completely competitive representation but not one of

supererogation.

Grendel's Den, supra, 953-54.

See also Goff v. Texas Instruments, Inc., 429 F.Supp. 973,978

(N.D.Tex. 1977)(No requirement that defendants pay for "the best

and most scrupulous out-of-state counsel that money can buy.")

However, assuming arguendo that this Court will establish a

standard which permits out of town rates on some occasions, amici

submit that even the Tenth Circuit rule does not provide enough

guidance in that it is not broad enough to cover all situations,

-11-

such as the one at bar. The Tenth Circuit rule, and even the

weaker versions of it advocated by the other circuits, all seem to

envision a situation where a plaintiff or a group of plaintiffs

decide to sue, begin seeking an attorney, and are turned down for

the reasons listed by the various circuits by attorney after

attorney in their community, thus presumably forcing the

plaintiff[s] to resort to out of town counsel.

That is not the situation though either in this particular

case or in the general group of high visibility, controversial

class actions like this one. Rather, the vast majority of these

cases are handled by national policy advocacy groups who have

chosen to have their offices in large cities. Furthermore, this

group of cases share one or more of the following characteristics:

1 ) little or no actual effort was made by plaintiffs to obtain

gualified local counsel and the national policy advocacy lawyers

attempt to meet the exception to local rates rule by providing live

or affidavit testimony from members of the local civil rights

plaintiffs7 bar that any attempt to locate qualified local counsel

would have been a vain and useless act since they "know" that no

local attorney would have taken the case; and

2) the case was "targeted" by the national group as one which

it would be advantageous for them to handle or be involved in for

a variety of reasons.

The particulars of this case confirm this analysis. In

1969, Charles Cotton, the attorney who originally filed the

Williams suit, graduated from law school and passed the bar. His

first job was at the Legal Defense Fund (hereinafter LDF) in New

-12-

York, where the general idea was that he would be trained to return

to the southern provinces and file lawsuits to alleviate the racial

discrimination that existed there.

Before Mr. Cotton left LDF in New York, he was urged by LDF

attorneys Mel Zarr and Frank White to return to New Orleans and

concentrate on filing suits against discriminating municipalities

(Deposition of Charles Cotton, R.D. 823 & 824, at pages 85-86,

hereinafter Depo, Cotton,___-___). Later, at a LDF conference, Mr.

Cotton specifically discussed filing a suit against the New Orleans

police department with Mr. Williams and Mr. Thomas, two of the

plaintiffs herein (Depo, Cotton, 25). Additionally, Mr. Cotton

flew to New York to discuss filing the case with LDF officials on

November 6 through November 9, 1972 and conducted numerous

conversations with LDF attorneys both before and after the suit was

filed. In the first years of his practice after leaving New York,

LDF provided substantial financial support to Mr. Cotton related to

this case. (Depo, Cotton, 7,28-30,36).

Despite this continuing relationship with LDF wherein Mr.

Cotton acted, in effect, as an arm of the LDF in New York, it

failed to exert proper oversight over the litigation considering

Mr. Cotton's lack of experience.3 The result was entirely

predictable. Mr. Cotton was in over his head, financial concerns

influenced his decisions, the LDF in New York didn't exercise

enough supervision, Mr. Cotton became "burned out", and the case

was improperly handled resulting in eventual dismissal in August,

3Details regarding Mr. Cotton's lack of experience are

catalogued in the City's 3rd Memo at 12-13.

-13-

1978 .

The dismissal of the case, perhaps not too surprisingly,

caught the attention of the plaintiffs. However, after their

disappointing experience with Mr. Cotton (Deposition of Gustave

Thomas, one of the named plaintiffs, R.D. 823 & 824 at pages 12-18

and 22-23, hereinafter Depo, Thomas, ___-___), the plaintiffs made

absolutely no effort whatsoever to locate local counsel, other than

some apparently fruitless contacts with Mr. Wilson (Depo, Thomas,

23-25). Instead, Mr. Thomas, who had observed the success that it

was having in other suits around the country, turned in

exasperation without further ado to LDF proper out of New York.

(Depo, Thomas, 18-21,23-26).

This scenario is confirmed by Mr. Wilson, who testified at his

deposition that he made no attempt after the initial dismissal in

1978 to seek lead counsel locally before trying to get LDF to take

over the case (Deposition of Ronald Wilson, R.D. 823 & 824 at pages

58-59, hereinafter Depo, Wilson, __-__). Additionally, Mr. Wilson

was aware of no efforts by the plaintiffs themselves to find local

counsel after the initial dismissal in 1978 (Depo, Wilson, 58-59).

Mr. Sherwood of LDF New York confirmed this assessment in a

sort of back-handed way. His first contact with the plaintiffs

themselves after the initial dismissal was on 9/14/79 when he got

a telephone call from Gus Thomas (Deposition of Peter Sherwood,

R.D. 823 & 824, Vol. Ill at page 30, hereinafter Depo, Sherwood,

Vol. ___,__). He testified that his recollection was that the New

“Details regarding these problems are provided in the City's

3rd Memo at 13-14.

-14-

Orleans lawyers which he recalls plaintiffs approaching were Mr.

Cotton, Mr. Bagneris, and Mr. Thibodaux and that Mr. Thomas told

him that he couldn't get a lawyer to handle the case (Depo,

Sherwood, Vol. I, 55-58; Vol. Ill, 31). However, this information

is contradicted by Mr. Thomas' own testimony referred to above

wherein Mr. Thomas made no mention of contacting Mr. Thibodaux and

no mention of contacting any lawyers after the dismissal other than

Mr. Bagneris and Mr. Wilson.

While admitting that a general civil rights counsel in New

Orleans could have handled this case (although he doubts as well as

LDF) (Depo, Sherwood, Vol. II, 15), he made no effort to help the

plaintiff recruit local counsel, because in the past he felt that

LDF had had little success in recruiting large firms for this type

of work (Depo, Sherwood, Vol. I, 60). This testimony, in addition

to be self serving, must be viewed as highly speculative, because

Mr. Sherwood made no attempt to contact any local attorneys in

regard to this case. There is no telling what a New Orleans

practitioner, whether solo, small firm, medium firm, or large firm

might have done if offered this case, particularly since Mr.

Sherwood also testified that LDF in his experience would handle

cases by providing technical assistance to local counsel and

funding the case if they were satisfied with the local attorney's

abilities (Depo, Sherwood, Vol. II, 16). See also long list of

employment discrimination cases handled by private counsel in which

Mr. Sherwood admitted that LDF provided some form of assistance

(Depo, Sherwood, Vol. Ill, 43-55).

Rather, Mr. Thomas and Mr. Wilson called Mr. Sherwood and

-15-

asked LDF proper to take the case. The Court re-opened the case and

LDF then petitioned the Court to re-certify the class. Peter

Sherwood flew to New Orleans to argue the motion.

As with all class certification motions, one of the pivotal

issues was whether the named plaintiffs had counsel who could

adequately represent the proposed class. Upon satisfying himself

that Mr. Sherwood had the appropriate qualifications to represent

the class, Judge Sear agreed to re-certify it.

Plaintiffs' allegation at pp.19-22 of their brief that Judge

Sear's decision that the class would be adequately represented by

Mr. Sherwood and the LDF proper was, in fact, a decision that the

plaintiffs could not be adequately represented by anyone other than

Mr. Sherwood and LDF proper is incorrect. Further, plaintiffs'

position is nonsensical in view of Judge Sear's explicit findings

that LDF acted in an advisory capacity prior to the motion for

recertification; that LDF failed to demonstrate local counsel was

unavailable5; and that, through his own experience, he knew that

5LDF contends, in support of its contention that no local

counsel were available, that it filed the uncontroverted affidavits

of three local lawyers who stated that there was no lawyer in the

area either willing or able to take on such a large piece of

litigation against the City. (Brief of Plaintiffs/Appellants, at

page 21) Aside from the obvious problems of affidavit testimony

about why actions not taken fifteen years before wouldn't have done

any good even if they had tried, the LDF has neglected to mention

that these affidavits were filed on 1/25/95 only one day prior to

the signing of Judge Sear's 34 page opinion when it was obviously

substantially complete and almost 16 and 1/2 months after Judge

Sear's deadline for final submissions of the fee application. (See

R.D.827,828, and 821 respectively.) Accordingly, it seems highly

likely that Judge Sear had signed his opinion well before the

plaintiffs' Motion to Supplement the Record crossed his desk. Amici

leave to the City of New Orleans to argue and the Court to decide

whether such submissions were timely so as to provide

uncontroverted evidence in the record.

-16-

ample expertise was available locally. Memorandum and Order

entered 1/27/95, R.D. 828 at p.2, n.l and p.28-29, n.6.

Thus, it can easily be seen that this case does indeed fit the

profile for highly publicized and controversial cases described

above at page 12 of this brief. First, there can be no question

that the case was highly publicized and controversial. See in

general Williams, et al. v. City of New Orleans, et al., 543

F.Supp. 662 (E.D.La. 1982), rev. 694 F.2d 987 (5th Cir. 1982), d.c.

judgment affm'd 729 F.2d 1554 (5th Cir. 1984)(en banc).

Second, little or no effort was made by plaintiffs before suit

was filed to seek out adequate local counsel. Similarly, after Mr.

Cotton, with the inadequate supervision of LDF, succeeded in having

the case dismissed, little or no effort was made by plaintiffs or

their representatives to find new local counsel. Rather, in both

instances, the lead plaintiffs were familiar with LDF and their

efforts stopped there. In the first instance, they accepted the

LDF protege and long distance LDF assistance and in the second

instance they demanded LDF proper.

Third, affidavit testimony, albeit apparently untimely, was

offered by the local plaintiff civil rights bar that there would

have been no point in the plaintiffs trying to find local counsel

because the plaintiffs' bar "knows" that no one would have taken

the case.6

6Almost identical testimony by the local plaintiffs' civil

rights bar has been offered live, listed on witness lists, and/or

referred to in settlement discussions in four fee applications

since 1990 totalling close to $2,000,000.00 in Hamilton, et al. v.

Morial, et al, E.D.La. #69-2443 (6000 member class action

concerning conditions of confinement at Orleans Parish Prison) and

one recent fee application in a companion case to Hamilton: Doe, et

-17-

Fourth and finally, this case was certainly targeted by the

Legal Defense Fund. It had an entire program devoted to training

young lawyers to bring such cases with its assistance and

supervision. It provided the host conference where the plaintiffs

and Mr. Cotton, its protege, held their first talks about filing

the suit. Its employees allegedly gave up chances to work at high

paying Wall Street firms to work at LDF, because in general, the

LDF caseload was so interesting and exciting, but even within that

universe Williams was especially so, because the discrimination in

the New Orleans police department "was one of the worst cases LDF

had ever encountered". Depo, Sherwood, Vol I, 66-67, 85.7

al. v. Foti, et al, E.D. La. #93-1227 (150-300 member class action

challenging conditions of confinement for juveniles).

’Similar targeting occurs routinely. In the Hamilton and Doe

cases referred to above, the national policy advocacy group

involved is the National Prison Project of the American Civil

Liberties Union. Deposition testimony taken in regard to the fee

applications revealed that the NPP receives tremendous volumes of

mail from prisoners all over the country and targets for suit the

jails and/or prisons in which it considers the conditions to be the

worst and the suits to be the easiest to win.

Likewise this Court will remember the hordes of out of town

counsel who descended upon Louisiana and this Court in regard to

the creation science controversy several years ago, Aguillard, et

al. v. Edwards, et al., 778 F.2d 225 (5th Cir. 1985)(on suggestion

of reh' en banc) and numerous earlier opinions, and the publicity

surrounding the preparation of Sojourner, et al. v. Edwards, et

al.,E.D.La. #91-2447, in regard to Louisiana's abortion law by

counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union (case later handled

by same counsel under auspices of the Center for Reproductive Law

and Policy) before the law had even been passed by the Legislature,

vetoed by then Governor Roemer, and the veto overridden by the

Legislature.

Lastly, the Court is no doubt aware of the recent arrival of

the famous/infamous Johnny Cochran, along with other out of town

counsel, to "help handle" the Bogalusa chemical evacuation matter

despite Mr. Cochran's published comments that local counsel would

be lead (and therefore presumably well capable of handling it

without out of town counsel's involvement).

-18-

CONCLUSION

Given the information presented in this brief, amici want this

Circuit to formulate a hard and fast rule whereby all attorneys who

litigate in a particular forum are paid according to the rates

prevalent in that forum with travel expenses being awarded in

addition only if plaintiff can make a realistic showing that he

actually contacted numerous local attorneys (by name) none of whom

were willing and/or able to take his case. After all, there is no

concrete indication in the history of the fee award acts and, in

particular, §1988, that awards of amounts greater than those

prevalent in the forum district were contemplated by Congress. In

this time of concern for the fiscal integrity of not only this

state, but also this country, there should be no consideration of

expanding on the plain meaning of acts passed by government.

In the alternative, amici curiae reguest that this Circuit

establish a "bright line" rule for the award of out of town hourly

rates. Such a rule, like the first alternative outlined above,

would reguire that the plaintiff make a realistic showing that he

actually contacted numerous local attorneys (by name) who rejected

his pleas for representation. Further, amici ask that this rule be

strictly construed, as does the Tenth Circuit, so as to recognize

that all but the most unusual cases can be handled by in town

counsel and, if not that, certainly by in state counsel, thereby

creating a heavy burden of proof on a plaintiff to show that there

were no local or in state counsel competent to handle the case.

Next amici ask that there be strict interpretation of the

requirement that plaintiff only needs to be able to retain

-19-

"competent" local counsel. Accordingly, recovery should be limited

to local rates with no additional travel expenses, even if

plaintiff chose to hire the best and brightest and most expensive

counsel in the country, as long as competent local or in state

counsel were available. Lastly, there should be no exceptions to

the proposed circuit rule for national policy advocacy groups. It

is the business and calling of such groups to litigate these types

of cases. They need no extra incentive. If an advocacy group

chooses to target for litigation the affairs of the states and

their citizens who form this circuit, it should be welcome to do so

in the spirit of open debate. However, unless the advocacy group

can meet the proposed rule as it applies to all other out of town

counsel, i.e. that plaintiffs can put forward a realistic showing

that, prior to the first contact with the advocacy group, they

actually tried to contact numerous local counsel(by name) and were

refused representation, it should be limited to the appropriate

local rates for competent counsel without additional travel

expenses.

As final note, amici curiae reguest that this Court re

emphasize in formulating this "bright line" rule that the burden of

proof is on the plaintiffs to show that they are entitled to out of

town rates. Thus, only after plaintiffs have presented evidence as

outlined above, would defendants be reguired to attempt to refute

it.

-20-

Respectfully Submitted,

BOWERS & BOWERS

201 St. Charles Avenue

Suite 2505

New Orleans, Louisiana 70170

(504) 522-3340

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I HEREBY CERTIFY that a copy of the foregoing pleading has

been served on all counsel of record by depositing same in the

United States mail, first-class postage prepaid and properly

addressed this 16th day of November, 1995.