Landgraf v. USI Film Products Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1992

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Landgraf v. USI Film Products Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1992. 8116864e-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c3cd69b-cd24-4e6e-8ea8-c83ff10a2f2f/landgraf-v-usi-film-products-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

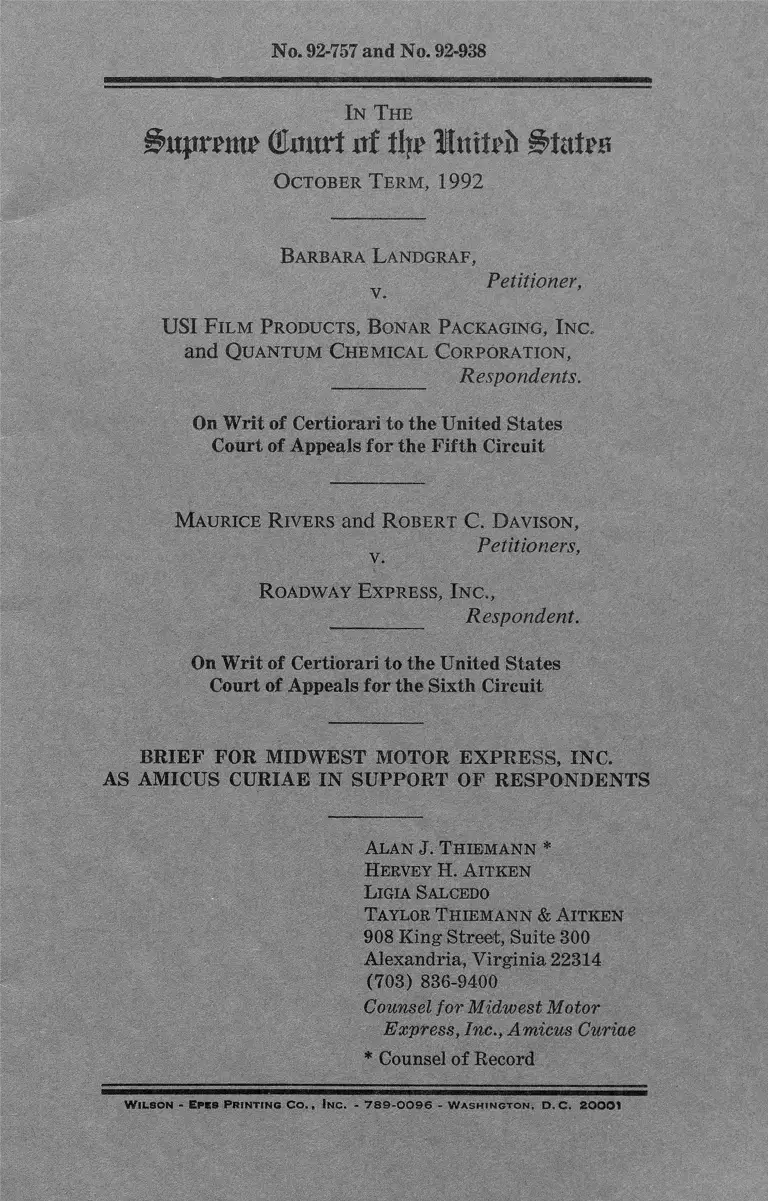

No. 92-757 and No. 92-938

In The

^upmttP ( ta r t at tlp> Intt?b g>ti\tw

October T erm , 1992

Barbara Landgraf,

Petitioner,

USI F ilm P roducts, Bonar Packaging, I nc,

and Quantum Chemical Corporation,

________ Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

M aurice R ivers and R obert C. Davison,

Petitioners,

R oadway Express, In c .,

________ Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF FOR MIDWEST MOTOR EXPRESS, INC.

AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Alan J. Thiemann *

Hervey H. Aitken

Ligia Salcedo

Taylor Thiemann & Aitken

908 King Street, Suite 300

Alexandria, Virginia 22314

(703) 836-9400

Counsel for Midwest Motor

Express, Inc., Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record

W il s o n - Ep e s P r in t in g Co . , In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h in g t o n , D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES........ ................-... ............ i

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE .......... . .......... 2

STATEMENT__________________ __ —... ............ ........ 3

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT............ ......................... ............. ............. 5

ARGUMENT.................................... ............ ................... - - 7

I. THE PRINCIPLE UPHELD IN BOWEN

REPRESENTS THE CARDINAL RULE OF

STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION GOVERNING

THE RETROACTIVE APPLICATION OF

FEDERAL CIVIL LEGISLATION............ ........ 7

II. BOWEN PRECLUDES THE RETROACTIVE

APPLICATION OF NEW FEDERAL CIVIL

LEGISLATION, SUCH AS THE CIVIL

RIGHTS ACT OF 1991, WHERE NO CON

GRESSIONAL INTENT IS CLEAR.............. . 10

III. THE RETROACTIVE APPLICATION OF

LEGISLATION, SUCH AS THE CIVIL

RIGHTS ACT OF 1991, WHICH CREATES

NEW LIABILITIES AND DUTIES BEYOND

RESTORATIVE LAW, RESULTS IN STAG

GERING REAL WORLD CONSEQUENCES.. 13

CONCLUSION ................. ............................ .................... . 17

APPENDIX

Excerpt of Section 1 from H.R. 5 and S. 5 5 ------- la

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Alpo Pet Foods, Inc. v. Ralston Purina Co., 913

F.2d 918 (Fed. Cir. 1990) ......................... ............ 13

Baynes v. AT&T Technologies, Inc., 976 F.2d 1370

(1992)........................................ ................ ................ 13

Belknap, Inc. v. Hale, 463 U.S. 491 (1983) .......... 16

Bowen v. Georgetown University Hospital, 488

U.S. 204 (1988) ___________ ________ _______passim

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

416 U.S. 696 (1974) _____________________ passim

Crown Cork & Seal Co., 255 NLRB 14, 107 LRRM

1195 (1981) ............. 15

Davis v. Omitowoju, 833 F.2d 1155 (3rd Cir.

1989) ................. ............ ..................... .................... . 12

DeVargas v. Mason and Hanger-Silas Mason Co.

Inc., 911 F.2d 1377 (10th Cir. 1990), cert, de

nied, 111 S. Ct. 799 (1991) ______ ___________ 12,14

Fray v. Omaha World Herald Co., 960 F.2d 1370

(8th Cir. 1992) ................................ ....................... 7, 8

Gersman v. Group Health A ss’n, 975 F.2d 886

(D.G. Cir. 1992) ............. 12

Gilberton Coal Co., 291 NLRB 344, 131 LRRM

1329 (1988), enforced, 888 F.2d 1381 (3rd Cir.

1989) ....................... 16

Johnson v. Uncle Ben’s, Inc., 965 F'.2d 1363 (5th

Cir. 1992) ________ _______ _____________ _ 11,13

Kaiser Aluminum & Chem. Corp. v. Bonjorno, 494

U.S. 827, 110 S. Ct. 1570 (1990) ........................ .passim

Lambott v. United Tribes Educational Technical

Center, 361 N.W.2d 590 (1985)________ _____ 16

Lehigh Metal Fabricators, 267 NLRB 568, 114

LRRM 1064 (1983) .......... ............................. .......... 15

Lehman v. Burnley, 866 F.2d 33 (2nd Cir. 1989).. 12

Leland v. Federal Ins. Adm ’n., 934 F.2d 524 (4th

Cir.), cert, denied, 112 S. Ct. 417 (1991) ........ 12

Luddington v. Indian Bell Telephone, 966 F.2d 225

(7th Cir. 1992), petition for cert, pending, No.

92-977.................... ............ ................................ ........ 10,13

Mojica v. Gannett Co., 779 F. Supp, 94 (N.D. 111.

1991) 14

I l l

Mozee v. American Commercial Marine Serv. Co.,

963 F.2d 929 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 113 S. Ct.

207 (1992) .................. ......................................... . 12

National Woodwork Manufacturers A ss’n v.

NLRB, 386 U.S, 612 (1967)................................... 11

N LRB v. Burkhart Foam, 848 F.2d 825 (7th Cir.

1988)................. ........ ................ ................................. 16

N LRB v. Charles D. Bonanno Linen Serv., 782

F.2d 7 (1st Cir. 1986) .................... ............ ............ 16

N LRB v. Elco Manufacturing Co., 227 F.2d 675

(1st Cir. 1955), cert, denied, 350 U.S. 1007

(1956) ....... ................................................................. 16

NLRB v. Jarm Enters, 785 F.2d 195 (7th Cir.

1986) ................. ............ ............ ........................ ........ 16

NLRB v. Mackay Radio and Telegraph Co., 304

U.S. 333 (1938) ................... ................ ................14-15,16

N LRB v. Remington Rand, Inc., 130 F.2d 919 (2nd

Cir. 1942) ................. ............ ..................................... 16

Pecheur Lozenge Co., 98 NLRB 496, 29 LRRM

1367 (1952), enforced as modified, 209 F.2d 393,

33 LRRM 2324 (2nd Cir. 1953) ............................. 16

Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. v. R.A. Gray &

Co., 467 U.S. 717 (1984) ........................... ............ 8

Plymouth Locomotive Works, 261 NLRB 595, 110

LRRM 1155 (1982) ................................................. 15

Simmons v. A.L. Lockhart, 931 F.2d 1226 (8th

Cir. 1991) ............ ............ ............... ............. ............ 12

Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in For

eign Parts v. Wheeler, (1814) 2 Gall. O.C.

105 .................. .......................................................... 8

Storey v. Shearson-American Exp., 928 F.2d 159

(5th Cir. 1991) ....................................... .................. 12

Trans World Airlines v. Independent Federation

of Flight Attendants, 109 S. Ct. 1225 (1989).... 15

United States v. Northeastern Pharmaceutical &

Chem. Co., Inc., 810 F.2d 726 (8th Cir. 1986),

cert, denied, 484 U.S. 848 (1987) _____________ 12

U.S. v. Magnolia Petroleum Co., 276 U.S. 160

(1928) ........................................................ ................ 9-10

TABLE OF AU THO RITIES—Continued

Page

IV

TABLE OF AU THO RITIES— Continued

Page

TJsery v. Turner Elkhorn Mining Co., 428 U.S. 1

(1976) ........... ........ .......................... ......... .................... 7, 8

Vogel v. City of Cincinnati, 959 F.2d 594 (6th

Cir.), cert, denied, 113 S. Ct. 86 (1992) ............. 12

Vulcan-TIart Corp. v. NLRB, 718 F.2d 269 (8th

Cir. 1983) ............. ........ ........... .................... ........ ..... 16

Wagner Seed Co. v. Bush, 946 F.2d 918 (D.C. Cir.

1991), cert, denied, 112 S. Ct. 1584 (1992)____ 12,13

Welch v. Henry, 305 U.S. 134 (1938) ........... ............ 8

CONSTITUTION

Fifth Amendment__________ 8

STATUTES

29 U.S.C. § 111 (c) ... ............ ..................................... . 2

29 U.S.C. § 152(9) ................... ............ ......................... 2

29 U.S.C. § 160 ( b ) ............... ......................................... 15

29 U.S.C1. § 1398................ 2

42 U.S.C. § 1981... ................ ........ .................... ............ 13

Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-166, 105

Stat. 1071................. passim

§ 402 (a ), 105 Stat,. 1099 .................. ........................ . 11

MISCELLANEOUS

136 Cong. Rec. S16,457 (daily ed. Oct. 22, 1990).... 10

136 Cong. Rec. S16,589 (daily ed. Oct. 22, 1990).... 10

137 Cong. Rec. S15,483, S15,485 (daily ed. Oct. 30,

1991) .............. ........ ..................................... ...........— 11

137 Cong. Rec. S15,472, S15,478 (daily ed. Oct. 30,

1991) ..................... ...................................... —........ ............. 11

137 Cong. Rec. S15,485 (daily ed. Oct. 30, 1991).... 11

Civil Rights Act of 1990: Hearing Before the

Senate Comm, on Labor and Human Resources

on S. 210b, 101st Cong., 1st Sess. (1989) ....... . 10

Coil and Weinstein, Past Sins or Future Trans

gressions: The Debate Over Retroactive A p

plication of the 1991 Civil Rights Act, 18 Em

ployee Relations Law Journal 5 (1992) ...—....... 13

V

DeMars, Retrospectivity and Retroactivity of Civil

Legislation Reconsidered, 10 Ohio Northern L.

Rev. 253 (1983)......................................... ............... 7, 9

Fairness in the Workplace: Restoring the Right

to Strike: Hearing on S. 55 Before the

Subcomm. on Labor of the Senate Comm, on

Labor and Human Resources, 103rd Cong., 1st

Sess. (March 30, 1993) ........................................... 3

H.R. 5, 103d Cong., 1st Sess., § 1, 139 Cong. Rec.

H82 (daily ed. Jan. 5, 1993) __.....____________passim

H.R. 4000, The Civil Rights Act of 1990: Joint

Hearing: Before the Comm, on Education and

Labor and the Subcomm. on Civil and Constitu

tional Rights of the Comm, on the J u d ic ia l,

101st Cong., 2d Sess. (1990)________ ______..... 10

Kahn, Completed Acts, Pending Cases, and Con

flicting Presumptions: The Retroactive Appli

cation of Legislation A fter Bradley, 13 George

Mason Univ. L. Rev. 231 (Winter 1990)............ 5

Marcus, A Percolating Legal Dispute on Civil

Rights, The Washington Post, April 17, 1992,

at A21 ...... ............. ...................,.... ............... .......... 4

S. 55, 103d Cong., 1st Sess,, § 1, 139 Cong. Rec.

S191 (daily ed. Jan. 21, 1993) ___________ __ passim

Senate Comm, on Education and Labor, Compari

son of S. 2926 and S. 1958, 74th Cong., 1st Sess.,

21-22 (1935), reprinted in A Legislative History

of the National Labor Reltaions Act, 1935, pp.

1319, 1346 (1985 Reprint, U.S. Government

TABLE OF AU THO RITIES—Continued

Page

Printing Office) .................................... ............ ...... 15

Smead, The Rule Against Retroactive Legislation:

A Basic Principle of Jurisprudence, 20 Minn. L,

Rev. 775 (1936) ....... ........................ ................ ..... passim

In The

d m t r t n f lift' l i t !tvh S ta te s

October T erm , 1992

No. 92-757

Barbara Landgraf,

Petitioner,v.

USX F ilm Products, Bonar Packaging, Inc .

and Quantum Chemical Corporation,

________ Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

No. 92-938

Maurice R ivers and R obert C. Davison,

Petitioners,v.

R oadway Express, In c .,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF FOR MIDWEST MOTOR EXPRESS, INC.

AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

2

Midwest Motor Express, Inc. (“Midwest”) is an inter

state motor carrier of freight located in Bismarck, ND,

operating in nine states. Midwest’s interest stems from

likely legislation pending in Congress that would create

another retroactive application problem identical to the

one under the Civil Rights Act of 1991 now before this

Court. Enactment of such legislation without a clear-cut

prospective effective date would expose Midwest to serious

threat of injury. Therefore, amicus seeks resolution by

this Court of the apparently conflicting precedents on

retroactive application of federal civil legislation.

Since August 12, 1991, Midwest has been engaged in a

labor dispute with the International Brotherhood of Team

sters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of Amer

ica (“Teamsters”), within the meaning of the Norris-

LaGuardia Act (29 U.S.C. § 111(c)), and the National

Labor Relations Act (“NLRA”) (29 U.S.C. § 152(9)),

as applied to the Multiemployer Pension Plan Amend

ments Act of 1980 (“MPPAA”) (29 U.S.C. § 1398).1

Nevertheless, not unlike the instant appeals under the

Civil Rights Act of 1991, a proposed amendment to the

NLRA threatens to turn Midwest’s past legal actions into

illegal ones—by retroactive application of a new law.

Legislation has been introduced in Congress to amend

the NLRA (H.R. 5 and S. 55) which contains no effective

date concerning when an employer may be prohibited

from hiring permanent replacement workers during eco

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE

1 The Teamsters struck Midwest on August 12, 1991, after

negotiations over a new contract reached an impasse. Following

commencement of the strike, the parties resumed bargaining

with the assistance of a federal mediator, which bargaining has

continued to the date of this brief without settlement. During

the course of this labor dispute, Midwest has continued to oper

ate only by hiring permanent replacements as it is permitted to

do under current federal law.

3

nomic (wage and benefit) strikes. The relevant identical

language of H.R. 5 and S. 55 is excerpted and attached

as Appendix A. Consequently, if that legislation passes

as currently drafted,2 and if this Court now fails to

resolve the apparent conflict between Bradley v. School

Board of the City of Richmond, 416 U.S. 696 (1974)

and Bowen v. Georgetown University Hospital, 48B U.S.

204 (1988), Midwest expects that controversy and con

fusion similar to that engendered by the retroactive appli

cation of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 will occur. Such

confusion is likely to result in serious adverse harm to

Midwest’s business and could subject it to unfair labor

practice charges and/or costly state litigation. See infra

at 13-17. The mere prospect of these occurrences is

jeopardizing Midwest’s ability to remain in business.

Accordingly, amicus has a vital interest in the resolu

tion of the issues raised in this case. Amicus believes it

will bring insights and information beyond what is pre

sented by Petitioners and Respondents, which will be

useful to the Court in deciding the issues presented.3

STATEMENT

These cases involve contradictory principles governing

the prospective application of civil laws, which conflict

this Court so far has been reluctant to resolve. Although

the principle of prospectivity dates to the Greeks and

Romans,4 it has not always been followed by this Court.

2 H.R. 5 ad S. 55 were introduced in the Senate and the House

of Representatives in January 1993. H.R. 5, 1.03rd Cong., 1st

Sess., § 1, 139 Cong. Rec. H82, (daily ed. Jan. 5, 1993); S. 55,

103rd Cong., 1st Sess., § 1, 139 Cong. Rec. S191, (daily ed. Jan.

21, 1993). House and Senate floor action is eminent, and the

Clinton Administration has endorsed the legislation as drafted.

Fairness in the Workplace: Restoring the Right to Strike: Hear

ing on S. 55 Before the Subcomm. on Labor of the Senate Comm,

on Labor and Human Resources, 103rd Cong., 1st Sess. (March 30,

1993) (statement of Robert B. Reich, Secretary of Labor).

3 This brief is filed with the written consent of the parties.

The letters of consent have been filed with the Clerk of Court.

4 As begins the seminal work on the rule against retroactivity:

“The bias against retroactive laws is an ancient one.” Sinead,

4

At the heart of the dispute is this Court’s holding that

a court is to apply the law in effect at the time it makes

its decision, unless doing so would result in “manifest

injustice” or there is statutory direction (or legislative

history) to the contrary. Bradley, 416 U.S. at 711. On

the other hand, this Court more recently reaffirmed that

“ [Rjetroactivity is not favored in the law. Thus, con

gressional enactments and administrative rules will not be

construed to have effect unless their language requires

this result.” Bowen, 488 U.S. at 208.

There is a compelling reason for this Court to clarify

its position and to adopt a bright-line, common-sense rul

ing based on Bowen. As Justice Scalia urged in Kaiser

Aluminum & Chem. Corp. v. Bonjorno, 494 U.S. 827,

110 S. Ct. 1570, 1579 (1990) (Scalia, J., concurring),

this Court should overrule Bradley and reaffirm the clear

intent rule, since retroactive application is “never sought

(or defended against) except as a means of ‘affecting

substantial rights and liabilities,’ ” and even procedural

changes applied retroactively alter such rights. Id. at

1585. Thus, this Court should heed Justice Scalia’s warn

ing that “manifest injustice” is “just a surrogate for policy

preferences” and that justice can mean “whatever other

policy motivation might make one favor a particular

result.” Id. at 1587.

Failure to resolve this conflict will lead to continued

examples of congressional recklessness, as demonstrated

by the instant cases under the Civil Rights Act of 1991.5

Midwest contends that the same result will occur in

The Rule Against Retroactive Legislation: A Basic Principle of

Jurisprudence, 20 Minn. L. Rev. 775, 776-85 (1936).

5 Only controversy, confusion, and expensive and protracted

litigation has resulted when Congress deliberately leaves the ef

fective date issue unresolved, as it did in the Civil Rights Act

of 1991. As of mid-1992, 49 federal courts had ruled against retro

activity and 35 had ruled in favor of it. See Marcus, A Percolating

Legal Dispute on Civil Rights, The Washington Post, April 17,

1992, at A21,

5

federal striker replacement and other legislation, unless

the cardinal rule upheld in Bowen is reaffirmed.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Respondents ask this Court to affirm the decisions by

the Fifth and Sixth Circuits that the Civil Rights Act of

1991 does not apply retroactively. In support, Midwest

submits that the judicial chaos surrounding the retro

active application of legislation is the result of a dramatic

departure from the historical rale against retroactivity.

Whether Bradley and Bowen can co-exist on a highly

theoretical basis is, at best, debatable. See infra note 10

and accompanying text. In practice, however, clarifying

the existing confusion necessarily depends on rejecting the

irreconcilable precept which Bradley has been held to

support that it is not unjust, in most cases, to apply new

civil legislation retroactively.

The Supreme Court must find Bradley is applied

wrongly as a “presumption” in favor of retroactivity when

ever a new liability altering the position of private liti

gants and parties is involved, whether substantive or pro

cedural rights are implicated. See Kahn, Completed

Acts, Pending Cases, and Conflicting Presumptions: The

Retroactive Application of Legislation After Bradley, 13

George Mason Univ. L. Rev. 231, 239-40 (Winter 1990).

To this extent, the Supreme Court should overrule Brad

ley and reaffirm the long-standing rule of statutory con

struction that federal civil legislation only applies pros

pectively, unless there is a clear legislative intent to the

contrary. Ambiguity-—either intentional or unintentional

—must be resolved in favor of the prospective application

of legislation.

Moreover, Petitioners’ interpretation of Bradley repre

sents a blatant departure from the fundamental principles

of fairness inherent in the clear intent rule upheld in

Bowen. Accordingly, Petitioners’ analysis stands wholly

outside of the implicit constitutional and relevant policy

factors which this Court must weigh in deciding these

6

cases. Under Petitioners’ view, judicial review, Congress’

role, and fairness each is undermined.

First, Petitioners erroneously assume that Respondents

have acted wrongly in order to argue that Respondents

have no “vested right to do wrong.” Rivers v. Roadway,

Pet. Brf. at 29; Landgraf v. USI Film Products, Pet. Brf.

at 31. Second, Petitioners unpersuasively argue that the

plain meaning of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 demon

strates a clear congressional intent to apply the law retro

actively. Third, Petitioners move beyond the pale and

assert that, under Bradley, any law (whether procedural

or substantive) must be presumed retroactive based upon

whatever label, political spin or policy preference the pre

vailing members of Congress place on the law, regard

less of its effect on private parties or “what the original

statute actually meant.” Rivers v. Roadway, Pet. Brf. at

38. In Petitioners’ view, if Congress labels a statute re

medial or restorative, there is no room for judicial scru

tiny.6 * 8 Landgraf v. USI Film Products, Pet. Brf. at 29-33;

Rivers v. Roadway, Pet. Brf. at 35-39. This Court must

reject each of these specious arguments.

Rather than merely a judicial premption useful in in

terpreting ambiguous legislation, Bowen moreover, repre

sents the cardinal rule of statutory construction in de

termining the retroactive application of legislation. By

clarifying Bowen as such, this Court will preserve the

appropriate burdens and roles of the legislature and the

judiciary, including the historical and proper role of judi

cial review as a check on the power of the legislature

unfairly to render laws retroactive.

6 Ironically, the one type of law historically not forbidden by

the American principle of prospectivity was the “curative” law

validating past acts that otherwise would have been void. But

even curative laws that impaired vested rights or otherwise

worked an injustice to parties were condemned by the American

principle. See Smead at 786, n.36.

7

ARGUMENT

L THE PRINCIPLE UPHELD IN BOWEN REPRE

SENTS THE CARDINAL RULE OF STATUTORY

CONSTRUCTION GOVERNING THE RETROAC

TIVE APPLICATION OF FEDERAL CIVIL LEG

ISLATION

As Justice Scalia’s concurring opinion in Bonjorno re

veals, the principle that laws and customs should apply

only to future transactions unless expressly stated that

they apply either to past conduct or to pending trans

actions dates to the Greeks and Roman law. Bon-

jorno, 110 S. Ct. at 1586; Fray v. Omaha World Herald

Co., 960 F.2d 1370, 1374 (8th Cir. 1992). The prin

ciple, originally one of “natural law” which became a

legal maxim under English law, was applied as a rule of

statutory construction, and so found its way into Ameri

can law.7 In the United States, however, largely as a

result of judicial review, this rule of statutory construc

tion was combined with the concept of “vested rights”

and “justice” to become a part of the concept of justice

and a limitation on legislative power.8 See Smead at

776-85.

Thus, the American principle of prospectivity has

operated to protect vested rights by invalidating or nar

rowing the application of statutes that might have applied

retrospectively. These included statutes that expressly

7 As in England, retroactive American laws were held to be

oppressive and unjust, and it was maintained that the essence of

law was that it be a rule for the future. Smead at 780, n. 21.

8 In addition to being a rule of statutory construction in Amer

ican law, the American courts added a judicial limitation on the

constitutional ability of a legislative body to alter pre-enactment

rights and conduct. Judicial scrutiny is an important component

of the American constitutional system which controls legislative

behavior. See, e.g., Usery v. Turner Elkhorn Mining Co., 428

U.S. 1, 14-20 (1976). See also DeMars, Retrospectivity and Retro-

acitvity of Civil Legislation Reconsidered, 10 Ohio Northern L.

Rev. 253 (1983).

8

were enacted to take effect from a time prior to their

passage, as well as statutes that were to operate from

the time of their passage, but affected vested rights and

past transactions.9 See Smead at 781-787, n.35. The

fundamental notion has been and should be that, in most

cases, it is unjust to apply new civil legislation retro

spectively.

The rule against retroactivity thus embodies American

constitutional notions of fairness and due process. Today,

these factors must be considered by Congress and the

courts in determining the validity of civil legislation which

Congress explicitly makes retroactive. See, e.g., Pension

Benefit Guaranty Corp. v. R. A. Gray & Co., 467 U.S.

717 (1984) (rejecting a Fifth Amendment due process

challenge to a federal statute that retroactively imposed

liability on employers who withdrew from multiemployer

pension plans); Turner Elkhorn, 428 U.S. I.10 There

9 The prohibition included retrospective laws as defined by

Mr. Justice Story in Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in

Foreign Parts v. Wheeler, (1814) 2 Gall. C.C. 105:

. . . . Upon principle, every statute, which takes away or im

pairs vested rights acquired under existing law, or creates a

new obligation, imposes a new duty, or attaches a new dis

ability in respect to transactions or considerations already

past, must be deemed retrospective. . . .

10 The Supreme Court has found the rational basis standard to

be equivalent to the standard applied in Welch v. Henry, 305 U.S.

134, 147 (1938), where the Court held that a retroactive tax was

constitutional unless its application was so “harsh and oppressive”

as to violate due process. R.A. Gray, 467 U.S. at 733. This standard

requires that there be a rational connection between the legisla

tion’s purpose and its retroactive effect. It is consistent with the

rule against the retroactive application of legislation where Con

gressional intent is not explicit or clear. In the latter case, a

statute need not be invalidated, but simply applied prospectively.

Arguably, the Bradley presumption in favor of retroactivity ab

sent “manifest injustice” arose from cases in which retroactivity

was explicit or clearly intended but “injustice” resulted. See

Bonjorno, 110 S. Ct. at 1584. Theoretically, in this very limited

context, Bradley remains viable. See also Fray, 960 F.2d at 1374

(Bradley did not “silently sweep away the traditional principle”).

9

fore, when Congress makes a statute expressly retroac

tive, presumably it has reviewed these considerations and

has resolved the inherent tensions involving fundamental

fairness.

Accordingly, it is incongruous to suggest that legisla

tion not explicitly made retroactive should be presumed

to be retroactive, and then reviewed perfunctorily based

upon a standard (such as Petitioners’ conclusory reme

dial scheme), that ignores the fundamental issue of fair

ness which is the cornerstone of the historical rule of

statutory construction against retroactivity. See DeMars

at 264-272 (because the vested rights—remedial scheme

approach utilizes analytically conclusive terms, it does not

lead a court to consider the question of fairness which is

also basic to the issue of statutory retrospectivity).

In particular, as with the Civil Rights Act of 1991,

where Congress considered and rejected explicit retroac

tive application and failed to reach a consensus on its in

tent, after reviewing the requisite constitutional considera

tions, no finding of retroactivity is justified or should be

compelled. See infra at 10-12.

Therefore, Midwest submits that the rule reiterated

in Bowen is not only that prospectively must be up

held in the absence of clear intent, but further, that

prospectivity must govern in determining clear intent when

retroactivity is not explicit. Thus, to the extent that

Bradley establishes a presumption in favor of retroactiv

ity in the absence of clear intent or in determining clear

intent, Bradley is wrong and should be overruled.

Accordingly, Midwest urges this Court to find that the

cardinal rule of statutory construction in determining the

retroactive application of federal civil legislation is the

principle (and not merely the “presumption”) that leg

islation must be applied prospectively, unless Congress

specifically provides to the contrary. See Smead at 781

n.22; U.S. v. Magnolia Petroleum Co., 276 U.S. 160,

162 (1928) (“statutes are not to be given retroactive

1 0

effect or construed to change the status of claims fixed

in accordance with earlier provisions unless the legisla

tive purpose to do so plainly appears”). But see Lud-

dington v. Indiana Bell Telephone, 966 F.2d 225, 228

(7th Cir. 1992), petition for cert, pending, No. 92-977

(dictum) (prospectivity “is resolved, but not all the way”

because we are “speaking only of a presumption” against

retroactivity). Only in concert with this paramount rule,

can ancilliary rules of construction utilized by the courts

to determine statutory meaning and legislative intent (i.e.,

plain meaning) effectively operate without injury to the

historical notions of fairness and justice upon which the

principle is based.

II. BOWEN PRECLUDES THE RETROACTIVE AP

PLICATION OF NEW FEDERAL CIVIL LEGISLA

TION, SUCH AS THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1991,

WHERE NO CONGRESSIONAL INTENT IS CLEAR

The express retroactive provisions of the Civil Rights

Act of 1990 stirred much debate and disagreement as

Congress grappled with concerns of fairness and consti

tutionality.11 President Bush vetoed the 1990 act,11 12 and

Congress failed to override the veto. 136 Cong. Rec.

816,589 (daily ed. Oct. 22, 1990). In 1991, the bill’s

sponsors dropped the express retroactive provisions in

order to gain acceptance and, instead, inserted language

providing that “the amendments made by this Act shall

11 See, e.g., H.R. 4000, The Civil Rights Act of 1990; Joint Hear

ing: Before the Comm, on Education and Labor and the Sub-

comm. on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the Comm, on the

Judiciary, 101st Cong., 2d Sess. (1990) ; Civil Rights Act of

1990: Hearing Before the Senate Comm, on Labor and Human

Resources on S. 2104, 101st Cong., 1st Sess. (1989).

12 President’s Message to the Senate Returning Without Ap

proval the Civil Rights Act of 1990, 26 Weekly Comp. Pres. Doc.

1632-34 (Oct. 22, 1990), reprinted in 136 Cong. Rec. S16,457,

S16,458 (daily ed. Oct. 24, 1990).

11

take effect upon enactment.” 13 §402 (a), 105 Stat.

1099. Arguably, this language explicitly states that the

Act applies prospectively. Alternatively, the inference of

Congress’ action is that prospectivity is intended. See

e.g., National Woodwork Manufacturers Ass’n v. NLRB,

386 U.S. 612, 640 (1967).

Because of its contradictory legislative history, how

ever, the 1991 provision leaves open whether the law

applies retroactively to cases pending on the date of enact

ment or whether the law applies only prospectively to

future cases.14 Clearly, the Act was passed without

agreement on the issue, and apparently various mem

bers of Congress hoped this Court would resolve the

known conflicting legal authorities in Bradley and Bowen

in their favor. Congress thereby intentionally left its

meaning unresolved. Thus, Petitioners’ argument that the

plain meaning of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 compels

retroactivity fails. See Johnson v. Uncle Ben’s, Inc,, 965

F.2d 1363, 1372-1373 (5th Cir. 1992).

In Bonjorno, the Supreme Court simply reaffirmed that

“where the congressional intent is clear, it governs.”

Bonjorno, 110 S. Ct. at 1577. But enactment of an

ambiguous statute such as the Civil Rights Act of 1991,

13 On November 21, 1991, President Bush signed the Civil Rights

Act of 1991. Pub. L. No. 102-166, 105 Stat. 1071 (1991). In

addition to reversing several Supreme Court decisions, the Act

made substantial substantive and procedural changes including

changes in adjudicator (jury) and damages (compensatory and

punitive damages).

14 See 137 Cong. Rec. S15,483, S15,485 (daily ed. Oct. 30, 1991)

(interpretive memorandum submitted by Sen. Danforth, the bill’s

Republican sponsor, arguing against retroactivity) ; 137 Cong.

Rec. S15,472, S15.478 (daily ed. Oct. 30, 1991) (interpretive

memorandum submitted by Sen. Dole arguing against retroac

tivity) ; 137 Cong. Rec. S15.485 (daily ed. October 30, 1991) (in

terpretive memorandum by Sen. Kennedy, the bill’s Democratic

sponsor, arguing for retroactivity by characterizing the law as a

“restoration of a prior rule”). Notably, no sponsor characterized

the legislation as merely procedural or remedial.

1 2

or a silent statute such as the proposed federal striker

replacement legislation, can defy any meaningful attempt

to discern congressional intent. Under these circum

stances, the historical constitutional underpinnings of

American law require that Bowen prevail as the cardinal

rule of statutory construction, not merely as “presump

tion” to be utilized in deciding among competing policy

considerations. In effect, reaffirming the Bowen clear

intent rule would ensure that, in the future, Congress will

deliberate and provide clear intent on the retroactive appli

cation of any legislation that contains potential constitu

tional and fairness concerns.15 Therefore, because noth

ing in the Civil Rights Act of 1991, or its legislative his

tory, expresses a clear congressional mandate requiring

retoractive application, the statute must not apply to pend

ing cases.16

15 While the clear intent rule does not require that Congress

make explicit its intent to apply a statute retroactively, it does

require that Congress make its intent clear. Bonjorno, 110 S. Ct.

at 1577. Hence, the cardinal rule against retroactivity may be

superseded only by express statutory language or by implication

when the statute “requires” it, i.e., when limiting the statute to

prospective application would render it completely ineffective by

defeating its entire purpose. See e.g., United States v. Northeastern

Pharmaceutical & Chem. Co., Inc., 810 F.2d 726, 733 (8th Cir.

1986), cert, denied, 484 U.S. 848 (1987) (in order to be effective,

CERCLA had to reach past conduct).

16 Not surprisingly, the large majority of circuit courts have

applied the Bowen “presumption” against retroactivity finding no

clear expression of legislative intent to the contrary. See Lehman

v. Burnley, 866 F.2d 33, 37 (2nd Cir. 1989) ; Davis v. Omitowoju,

833 F.2d 1155, 1170-1171 (3rd Cir. 1989) ; Leland v. Federal Ins.

Adm’n., 934 F.2d 524, 528-529 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 112 S. Ct.

417 (1991) ; Storey v. Shears on-American Exp., 928 F.2d 159, 161-

162 (5th Cir. 1991) ; Vogel v. City of Cincinnati, 959 F.2d 594,

597-598 (6th Cir. 1992) ; Mozee v. American Commercial Marine

Serv. Co., 963 F.2d 929, 936 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 113 S. Ct. 207

(1992) ; Simmons v. A.L. Lockhart, 931 F.2d 1226, 1230 (8th Cir.

1991) ; DeVargas v. Mason and Hanger-Silas Mason Co. Inc., 911

F.2d 1377, 1392 (10th Cir. 1989), cert, denied, 111 S. Ct. 799

(1991) ; Gersman v. Group Health Ass’n, 975 F.2d 886, 900 (D.C.

Cir. 1992) ; Wagner Seed Co. v. Bush, 946 F.2d 918, 924 (D.C.

13

III. THE RETROACTIVE APPLICATION OF LEGISLA

TION, SUCH AS THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1991,

WHICH CREATES NEW LIABILITIES AND DU

TIES BEYOND RESTORATIVE LAW, RESULTS

IN STAGGERING REAL WORLD CONSEQUENCES

The Civil Rights Act of 1991 significantly expands

both 42 U.S.C. Section 1981 and Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 to include new causes of action as

well as new classes of plaintiffs. The enhanced remedies

for intentional discrimination under Title VII in effect

create new liabilities for sexual harassment in situations

that do not involve tangible job detriments, such as “hos

tile environment” cases in which the plaintiff suffered no

specific adverse employment action that resulted in eco

nomic harm. Monetary damages were never available be

fore in such cases under Section 1981 or Title VII.

Rights under Section 1981 are extended to post-formation

contractual relationships. In effect, conduct insufficient

to impose liability on employers before the Act was

passed, may now be enough to result in a finding of dis

crimination against those same employers. Coil and

Weinstein, Past Sins or Future Transgressions: The De

bate Over Retroactive Application of the 1991 Civil

Rights Act, 18 Employee Relations Law Journal 5, 6

(1992); see e.g., Baynes v. AT&T Technologies, Inc.,

976 F.2d 1370, 1374-1375 (1922); Luddington, 966

F.2d at 229.

Nevertheless, Petitioners argue that the Civil Rights

Act of 1991 affects only procedure or remedies, and thus

should be applied retroactively.17 In addition to preclud

ing a meaningful analysis of fairness, a key problem with

this approach is that the label applied to a particular

Cir. 1991), cert, denied, 112 S. Ct. 1584 (1992) ; Alpo Pet Foods,

Inc. v. Ralston Purina Co., 913 F.2d 918, 922-923 (Fed. Cir. 1990).

17 If Congress had, in fact, intended only to restore prior law

or to provide remedial rights that did not create new liabilities,

Midwest submits it could have written language to achieve that

limited result, See Johnson, 965 F.2d 1363,

14

change may not reflect whether the change alters sub

stantive rights or conduct. The label becomes a “pol

icy” tool for proponents of retroactive legislation. See

Bonjorno, 110 S. Ct. at 1585.

Petitioners also argue that, because one purpose of

the Civil Rights Act of 1991 was Congress’ intent to

overturn recent Supreme Court decisions on discreet em

ployment law issues, retroactivity must be presumed. See

Rivers v. Roadway, Pet. Brf. at 35-39. While a few

courts, grappling with the conflict between Bradley and

Bowen, have held that retroactive application of a new

law is appropriate where Congress clearly intended to

overrule recent case law and restore the law to its former

state, other courts reject this approach as too speculative.

See Mojica v. Gannett Co., 779 F. Supp. 94, 97 (N.D.

111. 1991) (retroactive application of the Civil Rights

Act of 1991 upheld in part on the basis that the Act was

meant to “restore” prior law); but see DeVargas, 911

F.2d at 1387. By reaffirming Bowen as the cardinal rule

of statutory construction against reoractivity, this Court

would eliminate the expansive dangers inherent in Peti

tioners’ approach. Only prospective application of a new

law would be appropriate, absent a clear congressional

intent to apply a statute retroactively in order to restore

recent prior law.

The potential unfair application of likely federal striker

replactment legislation to Midwest’s ongoing labor dis

pute starkly demonstrates the absurdity of Petitioners’

position. Under Petitioners’ interpretation of Bradley,

the mere conclusory characterization (albeit erroneous)

of federal striker replacement legislation as “restorative”

would result in the retroactive application of legislation

to Midwest.18

18 Proponents of H.R. 5 and S. 55 are characterizing the legis

lation as “restorative law” designed to overturn the Supreme

Court’s decisions in NLRB v. Maekay Radio and Telegraph Co.,

15

This result could require the National Labor Relations

Board (“NLRB” ) to find that Midwest retroactively com

mitted an unfair labor practice by hiring some permanent

replacements after August 12, 1991 under the newly

amended law.19 See Attachment A for proposed language

of H.R. 5 and S. 55 adding 29 U.S.C. § 158(a)(6).

Moreover, such a result could turn the current labor

dispute on its head by converting the Teamsters strike

against Midwest from an economic strike into an unfair

304 U.S. 333 (1938), and Trans World Airlines v. Independent

Federation of Flight Attendants, 109 S. Ct. 1225 (1989). See

note 2 supra, at 3. The legislative history of the NLRA conclu

sively refutes this position and demonstrates that the changes

sought by H.R. 5 and S. 55 would alter the long-standing legal

right of an employer to permanently replace economic strikers af

firmed under the NLRA. The legislative history of the Wagner

Act of 1935 (the original NLRA) preserved the right of an

employer to hire replacements, whether permanent or temporary.

Although the Wagner Act did not address the issue directly, a U.S.

Senate Education and Labor Committee memorandum regarding

the Wagner bill states:

[The bill] provides that the labor dispute shall be “current,”

and the employer is free to hasten its end by hiring a new

permanent crew of workers and running the plant on a normal

basis . . . . The broader definition of “employee” in [the bill]

does not lead to the conclusion that no strike may be lost or

that an employer may not hire new workers, temporary or

permanent, at will.

See Senate Comm, on Education and Labor, Comparison of S. 2926

and S. 1958, 74th Cong., 1st Sess. 21-22 (1935), reprinted in A

Legislative History of the National Labor Relations Act, 1935, pp.

1319, 1346 (1985 Reprint, U.S. Government Printing Office).

19 Ironically, while the Board may not issue a complaint based

upon conduct occurring more than six months before filing and

service of the charge (29 U.S.C. § 160 (b)), the six month limita

tions period does not begin to run until the party adversely af

fected receives actual or constructive notice of the unfair labor

practice. See Lehigh Metal Fabricators, 267 NLRB 568, 114

LRRM 1064 (1983) ; Plymouth Locomative Works, 261 NLRB

595, 110 LRRM 1155 (1982) ; Crown Cork & Seal Co., 255 NLRB

14, 107 LRRM 1195 (1981).

16

labor practice strike. See NLRB v. Burkart Foam, 848

F.2d 825 (7th Cir. 1988); NLRB v. Jarm Enters, 785

F.2d 195 (7th Cir. 1986); NLRB v. Charles D. Bonanno

Linen Serv., 782 F.2d 7 (1st Cir. 1986); Vulcan-Hart

Corp. v. NLRB, 718 F.2d 269 (8th Cir. 1983). The

most significant aspect of an unfair labor practice strike

is that strikers are entitled to reinstatement to their for

mer positions upon an unconditional offer to return to

work. Pecheur Lozenge Co., 98 NLRB 496, 29 LRRM

1367 (1952), enforced as modified, 209 F.2d 393, 33

LRRM 2324 (2nd Cir. 1953). In effect, the economic

strikers would be entitled to reinstatement if the NLRB

were to find that Midwest comniited an unfair labor prac

tice which had the effect of prolonging the economic

strike (i.e., that hiring permanent replactments presump

tively prolonged Midwest’s strike). See Vulcan-Hart

Corp., 718 F.2d 269; Gilberton Coal Co., 291 NLRB

344, 131 LRRM 1329 (1988), enforced, 888 F.2d 1381

(3rd Cir. 1989). These strikers would have to be re

instated even though Midwest hired permanent replace

ments. See Mackay, 304 U.S. 333.

Moreover, Midwest would be required to terminate its

current permanent replacements, even though they were

legally hired. See NLRB v. Elco Manufacturing Co.,

227 F.2d 675 (1st Cir. 1955), cert, denied, 350 U.S.

1007 (1956); NLRB v. Remington Rand, Inc., 130 F.2d

919 (2nd Cir. 1942). Midwest’s picture could become

even more oppressive because the terminated permanent

replacement workers could sue Midwest for breach of

contract and misrepresentation in North Dakota state

court upon their discharge to make room for reinstate

ment of the economic strikers. See Belknap, Inc. v. Hale,

463 U.S. 491 (1983).20 The weight of such multiple

20 The Supreme Court of North Dakota has upheld similar breach

of contract suits. See Lambott v. United Tribes Educational Tech

nical Center, 361 N.W.2d 590 (1985).

17

litigation alone could force Midwest out of business. In

deed, the real world consequences to Midwest of apply

ing federal striker replacement legislatino retroactively

under Bradley based upon mere labels could be staggering.

Therefore, it is in determining a clear congressional

intent that judicial review and the principle of fairness

embodied in the rule of statutory construction against

retroactivity become imperative. Petitioners segregate

this critical analysis entirely from the determination of

the “plain meaning” and “clear intent” of the statute by

misinterpreting Bradley to require the retroactive appli

cation of any new federal civil legislation which is labeled

“procedural” or “restorative”. As Midwest has shown,

this argument is untenable.

CONCLUSION

Because of the conflicting principle in Bradley that

retroactivity is not unjust and is presumed, the door is

open for Congress to pass federal civil legislation (such

as the Civil Rights Act of 1991 and the proposed federal

striker replacement legislation), without resolving its ap

plicability to current disputes. While such a state of

confusion may enable Congress to pass controversial leg

islation, it improperly allows Congress to shift the burden

of deciding the issue of retroactivity onto private litigants

and the courts at an exorbitant cost.

Therefore, this Court should guide the lower courts

and restore judicial order and economy, should encourage

Congress to provide clear intent, and should preserve the

important, long-standing origins and purpose of the cardi

nal rule of statutory construction against retroactivity.

The Court would accomplish all of these objectives by

reaffirming Bowen and overruling Bradley. Absent ex

plicit retroactive language or clear congressional intent,

legislation must apply only prospectively. This is the

bright-line, common-sense rule needed to restore funda

mental fairness to the concept of retroactivity.

18

Based upon the foregoing, Midwest submits that the

decisions of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in

Landgraf v. USI Film Products, and of the Court

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in Rivers and Davison

v. Roadway, are correct in finding that the Civil Rights

Act of 1991 applies prospectively, and should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Alan J. Thiemann *

Hekvey H. Aitken

Ligia Salcedo

Taylor Thiemann & Aitken

908 King Street, Suite 300

Alexandria, Virginia 22314

(703) 836-9400

Counsel for Midwest Motor

Express, Inc., Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record

APPENDIX

l a

APPENDIX

EXCERPT OF SECTION 1 FROM H.R. 5 AND S. 55

̂ &

January 5, 1993

❖

A BILL

To amend the National Labor Relations Act and the

Railway Labor Act to prevent discrimination based

on participation in labor disputes.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representa

tives of the United States of America in Congress assem

bled,

SECTION 1. PREVENTION OF DISCRIMINATION

DURING AND AT THE CONCLUSION

OF LABOR DSPUTES.

Section 8(a) of the National Labor Relations Act (29

U.S.C. 158(a)) is amended—

(1) by striking the period at the end of paragraph

(5) and inserting or”, and

(2) by adding at the end thereof the following

new paragraph:

“(6) to promise, to threaten, or to take other

action—

“(i) to hire a permanent replacement for an

employee who—

“(A) at the commencement of a labor

dispute was an employee of the employer

2 a

in a bargaining unit in which a labor or

ganization—

“(I) was the certified or recognized

exclusive representative, or

“ (II) at least 30 days prior to the

commencement of the dispute had

filed a petition pursuant to section

9(c)(1 ) on the basis of written au

thorizations by a majority of the unit

employees, and the Board has not

completed the representation proceed

ing; and

“(B) in connection with that dispute

has engaged in concerted activities for the

purpose of collective bargaining or other

mutual aid or protection through that labor

organization; or

“ (ii) to withhold or deny any other employ

ment right or privilege to an employee, who

meets the criteria of subparagraphs (A) and

(B) of clause (i) and who is working for or

has unconditionally offered to return to work

for the employer, out of a preference for any

other individual that is based on the fact that

the individual is performing, has performed, or

has indicated a willingness to perform bargain

ing unit work for the employer during the labor

dispute.”

* * * *