Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae Out of Time and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae Out of Time and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1974. 20dc2e59-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c46b350-bc51-49d4-ac4e-e550d3ecf0dc/franks-v-bowman-transportation-company-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae-out-of-time-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

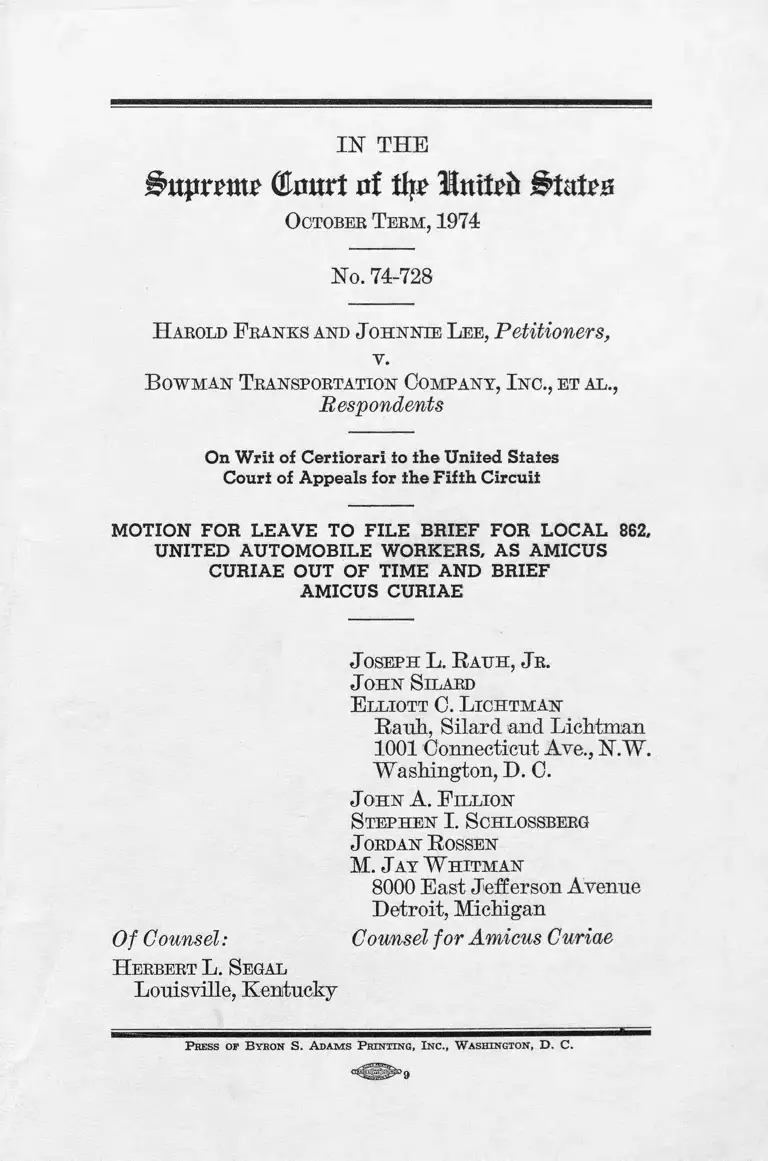

IN THE

Supreme (tart nf % Imtrft Stairs

O cto ber T e r m , 1974

No. 74-728

H arold F r a n k s a n d J o h n n ie L e e , Petitioners,

y.

B o w m a n T r a n sp o r t a t io n C o m p a n y , I n c ., e t a l .,

Respondents

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF FOR LOCAL 862.

UNITED AUTOMOBILE WORKERS, AS AMICUS

CURIAE OUT OF TIME AND BRIEF

AMICUS CURIAE

J o s e p h L. R a u h , J r .

J o h n S ila r d

E l l io t t C . L ic h t m a n

Ranh, Silard and Lichtman

1001 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D. C.

J o h n A. B il l io n

S t e p h e n I . S c h l o ssb e r g

J o rd a n R o ssen

M . J a y W h it m a n

8000 East Jefferson Avenue

Detroit, Michigan

Of Counsel: Counsel for Amicus Curiae

H e r b e r t L. S eg a l

Louisville, Kentucky

P ress of B yron S . A dam s P rinting , I nc ., W ashington, D . C.

1

IN THE

Bupxmx (£mvt ni % l&nxtxb g>tatxz

O cto ber T e e m , 1974

Ho. 74-728

H arold F r a n k s a n d J o h n n ie L e e , Petitioners,

v.

B o w m a n T r a n s p o r t a t io n C o m p a n y , I n c ., e t a l .,

Respondents

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF FOR LOCAL 862,

UNITED AUTOMOBILE WORKERS, AS AMICUS

CURIAE OUT OF TIME

Local 862, United Automobile W orkers (herein

“ U A W ” ) respectfully moves for leave to file the at

tached brief amicus curiae out of time in this case.

All parties have furnished written consent to the filing

of this amicus curiae brief. For the reasons set forth

below, UAW could not file this brief before this time.

11

The interest of UAW in this case arises from the

fact that it is petitioner in No. 74-1349, Local 862,

U A W v. Ford Motor Company and Dolores Marie

Meadows, presently pending before this Court on peti

tion for w rit of certiorari. In that ease, a class action

involving discriminatory refusals to hire on the basis

of sex, the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

found no statutory prohibition of retroactive senior

ity for the discriminatees. Unlike the F ifth Circuit’s

ruling in Franks, the Sixth Circuit declined to con

clude that “ reconciliation is impossible” between the

seniority-layoff protection of the incumbent workers

and the rights of a class of discriminatees hired under

a district court’s Title Y II decree, Meadows, 510 F.2d

939, 949 (1975). But the Sixth Circuit then returned

the issue to the District Court essentially without

guidance for the task of reconciling the interests of

these two groups of employees. UAW Local 862 filed

a petition for w rit of certiorari in No. 74-1349 request

ing that concurrent review be granted with Franks for

consideration of a viable alternative to the seniority-

layoff impasse which the F ifth Circuit resolved against

the discriminatees and which the Sixth Circuit was

unable to resolve. This Court, however, did not rule

upon U A W ’s petition during the 1974 term ; when the

term concluded without any ruling,1 the filing of this

brief amicus curiae became necessary, since the deci

sion in Franks may well dispose of the issue raised by

UAW in No. 74-1349. Moreover, none of the parties

in Franks having discussed the remedial alternative 1

1 By the time of the C ourt’s conclusion of its 1974 term, the

brief of petitioners, which we generally support, and concurrent

with which Rule 42(2) requires the filing of an amicus brief,

had long since been filed.

I l l

proffered by UAW in No. 74-1349, we request permis

sion to present that alternative in the attached brief

amicus curiae.

Respectfully submitted,

Of Counsel:

J o s e p h L . R a it h , J r .

J o h n S ila r d

E l l io t t C. L io h t m a n

Rauli, Silard and Lichtman

1001 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D . C.

J o h n A. E il l io n

S t e p h e n I. S ch l o ssb e r g

J ordan R o ssen

M. J a t W h it m a n

8000 East Jefferson Avenue

Detroit, Michigan

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

H e r b er t L. S eg a l

Louisville, Kentucky

INDEX

Page

Introduction ................................................................... 1

Argument ....................... ........................... . 3

I. TMs lOourt Should Reverse the Court of Appeals

and Approve the Front-Pay Save-Harmless Rem

edy which Preserves the Fair Seniority Claims of

Both the Title YII Discriminatee and the Incum

bent Employee........................................................ 3

II. The Proposed Front-Pay Save-IIarmless Remedy

is Simple in Operation and Economically Feasible. 5

Conclusion ..................................................................... 11

CITATIONS

Cases :

Bigelow v. RKO, 327 ILS. 251...................................... 5

California Department of Human Resources & Devel

op. v. Java, 402 U.S. 121........................................ 11

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312 ............................. 3

Local 862, UAW v. Ford Motor Company and Dolores

Marie Meadows, 510 F.2d 939 (6th Cir. 1975), pet.

for cert, pending (No. 74-1349) ............................... 6,8

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717................................ 4

Plumbers, Local 638 v. NLRB, F. 2d , 89

LRRM 2769 (D.C. Cir. 1975) ............................... 5

Story Parchment Co. v. Paterson Parchment Paper

Co., 282 U.S. 555 .................................................... 4

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 ............................................................. 4

Watkins v. United Steelworkers of America, 369 F.

Snpp. 1221 (E.D. La. 1974), reversed F.2d

, 10 FEP Cases 1297 (5th Cir., 1975) ............. 2

11 Index Continued

Page

S tatutes :

Title YII of Civil Eights Act of 1964 § 706(g)............. 3

Ky. Rev. Stat. § 341.530 ............................................... 11

M iscellaneous :

Cooper and Sobol “ Seniority and Testing Under Pair

Employments Laws,” 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598 ....... 3

Blumrosen, ‘ ‘ Seniority and Equal Employment Oppor

tunity,” 23 Rutgers L. Rev. 268 (1969)................ 3

Note, “ Last Hired, First Fired Layoffs and Title YII,”

88 Harv. L. Rev. 1544 (1975) ........................... 3

Prosser Law of Torts, 4th ed., p. 3 3 ........................... 5

118 Cong. Rec. 7168...................................................... 3

11ST TH E

(£mxtt Bi % Itttteii

O cto ber T e r m , 1974

Ho. 74-728

H arold F r a n k s a n d J o h n n ie L e e , Petitioners,

y.

B o w m a n T r a n sp o r t a t io n C o m p a n y , I n c ., e t a l .,

Respondents

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR LOCAL 862, UNITED AUTOMOBILE

WORKERS, AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTRODUCTION

This case presents this Court’s first major look at

remedial problems arising under Title V II when courts

seek to restore to discriminatees the job rights they

2

were denied by an employer’s discriminatory hiring

practices. Even in the best of circumstances, resolu

tion of the competing equities between the discrimina

t e s and the faultless incumbent workers, who have

been earning their seniority rights on the job, presents

challenging and novel problems. But they become the

more difficult when they arise at a time of widespread

unemployment and layoff.

The lower court opinion at bar, which denies retro

active seniority to the discriminatees, assumes that

either the discriminatees or the incumbent employee

group must bear the burden, by suffering layoff in

favor of the other group. I t assumes that normal

seniority rules will apply and the only question is

which group is to be placed on the lower rung of the

ladder. However, there is an alternative which does

not threaten the layoff either of incumbent workers

or newly-hired discriminatees. That is the TTAW-

proposed “ front pay” remedy which requires the

wrongdoing employer to hold both groups harmless

from layoff losses in work reduction situations. We

urge in the Argument this Court’s approval of that

remedy.1

1 The narrow question presented here is whether the employees

(discriminatees or incumbents) alone must suffer the burden of

the present recession or whether a court may impose th a t burden

upon a wrongdoing employer. Not before the Court is the entirely

distinct question raised by W atkins v. United Steelworkers of

America, 369 F. Supp. 1221 (B.D. La. 1974), reversed, — F.2d —,

10 F E P Cases 1297 (5th Cir., decided Ju ly 16, 1975) of whether a

court may remedy an employer’s past discrimination by providing

layoff protection to employees who are members of a m inority or

class discriminated against but who have not specially and in

dividually suffered such discrimination.

3

A R G U M E N T

I

THIS COURT SHOULD REVERSE THE COURT OF A P

PEALS AND APPROVE THE FRONT-PAY SAVE-

HARMLESS REMEDY WHICH PRESERVES THE FAIR

SENIORITY CLAIMS OF BOTH THE TITLE VII DIS

CRIMINATES AND THE INCUMBENT EMPLOYEE

For the apparent seniority rights impasse perceived

by the Court of Appeals there is a solution which that

court does not seem to have recognized: a remedy

which requires the wrongdoing employer to protect

from layoff losses both those against whom he dis

criminated and his incumbent work force.2 Approval

of that remedy is much to be desired, for this Court

doubtless perceived last term during its consideration

of DeFunis (416 TT.S. 312) the difficult character of

remedies for past discrimination which throw the bur

den either upon the wronged minority or upon other

blameless citizens. I f in the employment area there

is a better solution, surely it should be preferred over

one which is unjust either to the discriminate® or the

incumbent worker.

Thus, if the discriminatees are hired without the

same protection against losses in work reduction situa

tions which they would have had but for their em

ployment rejection, the key Congressional purpose to

provide full Title Y II remediation is frustrated. As

the Conference Committee emphasized (see 118 Cong.

Rec. 7168), section 706(g) is intended to assure “ that

persons aggrieved by the consequences and effects of

2 See Cooper and Sobol, ‘ ‘ Seniority and Testing Under F a ir Em

ployment Laws,” 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598, 1678-1679 (1969) ; Blum-

rosen, “ Seniority and Equal Employment O pportunity,” 23 R ut

gers L. Rev. 268, 305-07, 311-12 (1969); Note, “ Last Hired,

F irs t F ired Layoffs and Title V II ,” 88 Harv. L. Rev. 1544, 1560

n. 68 (1975).

4

the unlawful employment practice be, so fa r as pos

sible, restored to a position where they would have been

were it not for the unlawful discrimination.” Given

this Court’s definitive ruling in Swann (402 U.S. 1, 26)

that to remedy school segregation there must be deseg

regation in actuality rather than mere theory, we

cannot believe that in the employment area this Court

would affirm the ruling below which may leave the

employment discriminatee in actuality without job and

pay.

On tbe other hand it would also be unjust if, after

years spent in earning seniority on the job, the faultless

incumbent employees were subjected to layoff in favor

of discriminatees hired with seniority retroactive to

the time when they were denied hiring. Only a year

ago a m ajority of this Court declined to put the deseg

regation burden upon suburban school districts “ not

shown to have committed any constitutional violation.”

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 745. Considering

that the incumbent employees are in no way at fault

for the employer’s Title Y II violation, a remedy which

corrects the employer’s wrongdoing at the expense of

those employees is unjust and unwise.

Accordingly, we urge for the Court’s consideration

a th ird and better option, which requires that following

reinstatement of discriminatees the offending employer

hold harmless against layoff losses both the discrimi

natees and his incumbent employees hired between the

discriminatees’ original rejection and their ultimate

hiring. That remedy properly puts the full burden

upon the wrongdoer rather than his victims or other

unoffending employees. I t is a familiar rule of law that

the full remedial burden shall be on the offending party.

Such seminal decisions as Story Parchment (282 U.S.

5

555) and Bigelow (327 II. S. 251) apply the rule as

between the wrongdoer and his victim.3 The ride

equally applies as between the wrongdoer and third

parties; where the wrongdoer has done intentional

harm he is liable to third parties as much as to the

immediately injured party, because “ having departed

from the social standard of conduct, he is liable for the

harm which follows from his act” (Prosser, Law of

Torts, 4th ed., p. 33). Thus there is every reason of

equity and justice for placing the full burden upon

the employer who violated Title V II, requiring him

to protect both the discriminatees and his incumbent

work force against layoff losses in periods of work

reduction.

II

THE PROPOSED FRONT-PAY SAVE-HARMLESS REMEDY

IS SIMPLE IN OPERATION AND ECONOMICALLY

FEASIBLE

The suggested remedy is simple in operation. To

the extent that discriminatees are hired with retro

active seniority protection against layoff losses, the in

cumbent work force (without a save-harmless remedy)

would be prejudiced by becoming vulnerable to earlier

layoffs. To prevent that prejudice, under the “ front-

pay” proposal the employer would be required to hold

harmless against layoff losses that number of employees

which is equivalent to the number of discriminatees

8 A similar policy applies to labor contracts. Where, for example,

an employer agrees in its labor contract to have certain work done

at the construction site by its bargaining unit employees and then

agrees with another contractor to install pieces on which the

promised work has already been performed elsewhere, the em

ployer, if it honors the second contract must pay his unit workers

for the work promised them but later given away. Cf. Plumbers,

Local 638 v. N LRB , — F.2d —, 89 LRRM 2769, 2777-78 (D.C Cir.,

1975).

6

hired with retroactive seniority. I f the employees to

be held harmless are the discriminatees themselves,

then it is only they to whom the obligation would run.

On the other hand, if through collective bargaining,

self-selection, or otherwise, the protection is provided

to the incumbent employees, or to a mix of discrimina

tees and incumbents, then the number of positions

protected would remain equivalent to the number of

discriminatees hired.

The facts of Meadows illustrate the operation of the

remedy.4 Some 35 or fewer discriminatees were hired

in 1974 at the Ford Truck P lant in Kentucky under

the District Court’s decree. (Retroactive seniority

would yield those employees protective dates on and

after November of 1969, when Ms. MeadowTs and other

discriminatees were originally rejected for hiring. On

that basis the following save-harmless conditions would

apply :

(1) In a layoff situation reaching only the em

ployees hired in recent months—after the 35 dis

criminatees were hired—there would be no save-

harmless obligation, since none of those employees

4 We illustrate the remedy with the facts in Meadows because

the recoi’d in Franks is unclear on this point. In Franks, the Dis

tric t Court ordered that members of the relevant class be granted

the right to reapply for Over the Road (OTR) jobs, and if found

qualified, to be hired or given priority over other applicants

(5 EPD If 8497, p. 7371, see 495 F.2d 398, 413). The record does

not show the number of applicants in the class who meet the

Company’s formal qualifications of age, fitness and experience.

While petitioners believe that 127 members of the class meet these

qualifications (Supreme Court Brief, p. 9, n. 9), counsel for peti

tioners informs us tha t the Company claims tha t not more than

four or five of the applicants are qualified and are thus eligible to

benefit from the D istrict C ourt’s order. Discovery is proceeding

and the D istrict Court has not yet resolved these conflicting claims.

7

were affected by the employer’s discrimination or the

grant of retroactive seniority to discriminatees;

(2) Similarly, in a layoff situation so severe as to

reach further up the seniority ladder than 1969, when

the discriminatees were wrongfully rejected, once

again there would be no save-harmless obligation since

no discriminatee or incumbent employee would have

avoided layoff regardless of whether retroactive

seniority is granted to the discriminatees ;

(3) In a layoff situation of, for example, 35 persons

which reaches into but not beyond the ranks of em

ployees with seniority dates between the discrimina

tees’ rejection of 1969 and their hiring in 1974, the

first 35 persons (excluding persons hired more recently

than the discriminatees) affected would be held harm

less.5 I f the remedy should go to the 35 discriminatees,

they are in effect given the wTage and fringe benefit

protection they would have had if they had not been

wrongfully rejected when they applied in 1969. I f it

goes to 35 incumbents, they in tu rn are protected

against any loss caused by the grant of retroactive

seniority to the discriminatees. In other wTords, in any

contingency the discriminatees are restored fully to

the job protection they would have had but for the

employer’s violation of their rights, without prejudic

ing or diminishing the earned layoff seniority of the

incumbent work force.

8 The 1 ‘ front-pay ’ ’ proposal here is concerned with wage and

fringe benefits and not the work itself. As to the latter, we show

below tha t employers generally find work for employees whom

they must pay. However, if reduction in the work force may

actually become necessary, then many employees from either the

“ discriminatee” group or the “ incumbent work force” group

may opt for layoff with pay. I f fu rther employees must be selected

for layoff, other equitable arrangements can be made.

8

Moreover, for three separate reasons, the economic

consequences are modest for the employer required to

provide a hold harmless remedy. F irst, because the

number of discriminatees hired in Title Y II cases is

small; second, because employers have generally proved

able to find productive work for employees whom they

must p ay ; and third, because under the unemployment

compensation system and corporate tax principles, only

a small portion of save harmless pay represents a

profit loss for the employer.

1. Small numbers. In Franks the number of

affected discriminatees may be as low as four in a

company with about 500 over the road drivers.6 In

Meadows the number of discriminatees hired under

the Title Y II decree is fewer than 35 in a plant of one

thousand production workers. Statistics compiled by

the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion show that EEOC has found reasonable cause to

believe that hiring discrimination has been proven

against only an infinitesimal proportion of the black

and female work force in each of the last six years.7

National and auto industry statistics compiled by

EEOC show the very small proportion of the total

work force filled by blacks or women hired in recent

years, and thus make clear the small probable impact

on the employers of a save harmless remedy in dis-

criminatee situations. The EEOC nationwide tables

{infra, Appendix B) show that only 2.8 percent of

the 1974 work force is composed of blacks hired since

1969, and only 8.1 percent represents women hired

6 See p. 6, n. 4, supra.

7 In 1974, for example, such, findings were made with respect to

the charges of hiring discrimination of only 47 blacks and 54

women, 0.00127% and 0.00043% respectively of the blacks and

women in the workforce (see Appendix A in fra).

9

since that year.8 The data for employment in motor

vehicle production (Appendix C) show that only 5.9

percent and 6.1 percent of the 1974 work force are

blacks and women respectively hired since 1969.9 I t is

clear that a save harmless obligation arising from and

in proportion to an employer’s recent hiring of minority

group employees, ordinarily would represent only a

small additional obligation for the employer who vio-

8 Proportion of new black and women hires (between 1969 and

1974) to total 1974 employment in all industries (computed from

Appendix B ) :

Job Category Blacks Women

Total Employment 2.8% 8.1%

W hite Collar 2.4 9.9

Office Managers 1.8 5.6

Professional 1.1 6.6

Technical 2.7 10.2

Sales Workers 2.5 15.4

Office and Clerical 3.3 10.7

Blue-Collar 3.1 4.7

Craft 2.6 1.7

Operatives 4.0 5.7

Laborers 1.4 6.8

Service Workers 4.1 16.8

9 Proportion, of new black and women 'hires (between 1969 and

1974) to total 1974 employment in motor vehicle industry (com-

puled from Appendix C) :

Job Category Blacks Women

Total Employment 5.9% 6.1%

White-Collar 3.9 5.0

Office Managers 3.9 1.5

Professionals 2.8 4.8

Technical 2.7 3.2

Sales Workers 1.0 0.6

Office and Clerical 5.5 11.0

Blue-Collar 6.3 6.5

Craft 3.3 0.2

Operatives 7.5 8.0

Laborers 3.1 7.9

Service Workers 7.5 3.8

10

lated Title Y II since lie would be providing the protec

tion only for the number of persons equal to the recent

ly hired blacks and women against whom he had dis

criminated.

2. W ork opportunities. I t is also clear that an

employer required to save employees harmless from

layoff loss will often not have to provide them any front-

pay but will be able to produce productive work for

them. The common observation that employers will find

work for those whom they must pay is confirmed by ex

perience. For instance, employers faced with the possi

bility of layoffs, have often retrained or reassigned

their employees for other positions. W ork previously

contracted out or “ shunned” has been done by the em

ployer ’s own employees.10 11 Substantial overtime work—

which has persisted even during the current reces

sion 11—can be reassigned to the employees who would

otherwise be laid off. Moreover, where under UAW

contracts12 employers have been required to pay a

maximum of four hours to an employee called in from

home, the experience has been that the employee is

given a full four hours work by the assignment of work

which might otherwise be deferred. I t seems clear,

therefore, that even for the small number of workers

whom the wrongdoing employer has to save harmless,

he can minimize the necessity of paying wages without

receiving labor.

3. Small profits impact. Finally, even if some front-

pay to employees on layoff results, i t is significant that

10 See articles in Appendices D, E and P infra.

11 Appendix G infra contains Bureau of Labor statistics which

show th a t substantial overtime has continued despite the recession

economy of 1974-1975.

12 p or exampie; 1973 ILAW-General Motors National Agreement,

II80.

11

the employer bears only a small portion of each wage

dollar he must pay. In the absence of that front-pay

obligation, the worker would be drawing unemployment

compensation borne in part by the employer. In times

of heavy unemployment, the employer must pay sub

stantially increased amounts to the state unemploy

ment compensation fund, which makes the employer’s

“ experience ra te” a significant factor in his payment

obligation.13 Moreover, any hold harmless wages are

also deductible by the employer from his corporate

income taxes, so that only about one-half of such pay

ments may represent any loss of profits. Thus the

monetary consequences of a save harmless remedy are

not severe. The wrongdoing employer’s actual burden

is less than one-half of what he must pay and society

at large pays a portion in loss of tax revenues due to

increased employer wage deductions. The employer,

of course, can also raise his prices. While we do not

welcome lower tax revenues or higher prices, that is

surely a more just result, for instead of putting the

onus of legal redress and social reform on innocent

individual workers and their families, the burden is

shared between the wrongdoing employers and the so

ciety which has so long practiced and tolerated employ

ment discrimination.

13 While the formulas vary, all states have systems of levying

unemployment insurance tax in relation to an individual employ

e r ’s experience with unemployment. The most popular system is

the “ reserve-ratio system” where the employer’s account is cred

ited for contributions and against which benefits paid to former

employees are charged. The reserve-ratio, which is the resulting

balance to the employer’s payroll, then determines the employer’s

tax rate. The lower the ratio (i.e. high unemployment experience),

the higher tax ra te and vice-versa. (e.gr., Ky. Rev. Stat.

§ 341.530; see also California Department of Human Resources

Develop, v. Java, 402 U.S. 121, 126 (1971) concerning California’s

unemployment insurance system).

12

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, it is submitted that the lower

court was in error in assuming that either Title V II

discriminatees or the incumbent employee group must

bear the burden of layoffs. The Court should affirm the

propriety of a front-pay remedy which places the bur

den on the wrongdoing employer and which holds harm

less from economic prejudice and layoff loss both the

wronged discriminatees and the incumbent workers who

have been earning their seniority protection on the job.

Respectfully submitted,

J o s e p h L . R a t jh , J e .

J o h n S il a e d

E l l io t t C. L ic h t m a n

Ranh, Silard and Lichtman

1001 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D. C.

J o h n A. F il l io n

S t e p h e n I. S c h lo ssb er g

J ord a n R o ssen

M . J a y W h it m a n

8000 East Jefferson Avenue

Detroit, Michigan

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

Of Counsel:

H e r b er t L . S eg a l

Louisville, Kentucky

APPENDIX

APPENDIX B

2a

1969

PAGE 58 SEN SITIV E INFORM ATION—UNAUTHORIZED DISCLOSURE PRO H IB ITED

STATE NO. UNITS # 52,424

TOT WHITE OFFS SALES OFFS BLUE SERV

EMPL COLL MGES PROF TECH WRKS CLER COLL CRAFT OPER LABOR WRKS

ALL T 28,598,713 13,532,255 2,545,601 2,338,821 1,240,602 2,472,974 4,934,257 13,205,154 3,886,454 6,713,650 2,685,050 1,861,304

ALL M 18,912.707 7,695,354 2,286,971 1,798,192 930,493 1,472,356 1,207,342 10,266,390 3,622,217 4,762,856 1,881,317 953,906

ALL F 9,686,006 5,836,901 258,630 540,629 310,109 1,000,618 3,726,915 2,938,764 264,237 1,950,794 723,733 910,341

ANG T 24,700,001 12,606,795 2,471,921 2,220,723 1,130,567 2,310,713 4,472,871 10.853,037 3.558,323 5,481,095 1,813,619 1,240.169

ANG M 16,390,253 7,297,815 2,227,372 1,723,007 870,073 1,388,382 1,088,981 8,480,085 3,333,877 3,874,119 1,272,089 612,353

ANG F 8,309,748 5,308,980 244,549 497,716 260,494 922,331 3,383,890 2,372,952 224,446 1,606,976 541,530 627,816

NEG T 2,720,503 555,902 38,090 49,652 69,432 98,868 299,860 1,664,015 194,636 902,533 566.846 500,586

NEG M 1,740,426 206,141 29,027 25,299 31,490 49,288 71,037 1,272,266 170.350 658,920 442,996 262,019

NEG F 980,077 349,761 9,063 24,353 37,942 49,580 228,823 391,749 24,206 243,613 123,850 238,567

SSA T 912,298 229,828 21,358 23,608 24,659 45,269 114,934 586,065 103,466 285,250 197,349 96,405

SSA M 613,769 113,175 18,407 17,282 17,602 25,102 34,782 437,935 90,588 200,530 146,817 62,659

SSA F 298,529 116,653 2,951 6,326 7,057 20,167 80,152 148,130 12,878 84,720 50,532 33,746

ORI T 185,118 113,890 9,741 42,101 13,311 11,408 37,329 53,084 17,667 21,571 13,846 18,144

ORI M 115,693 65,485 8,391 30,753 9,389 6,769 10,183 39,153 16,246 13,833 9,074 11,055

ORI F 69,425 48,405 1,350 11,348 3,922 4,639 27,146 13,931 1,421 7,738 4,772 7,089

AMI T 80,793 25,840 4,491 2,737 2,633 6,716 9,263 48,953 12,362 23,201 13,390 6.000

AMI M 52,566 12,738 3,774 1,851 1,939 2,815 2,359 36,951 11,156 15,454 10,341 2,877

AMI F 28,227 13,102 717 886 694 3,901 6,904 12,002 1,206 7,747 3,049 3,123

PAGE 1 SEN SITIV E INFORM ATION--UNAUTHORIZED DISCLOSURE PRO H IB ITED

1974 EEO 1 REPORT NATIONW IDE SUMMARY

35,796 COMPANIES

ALL T 33,865,626 16,139,519 3,450,041 2,502,069 1,513,454 3.259,063 5,414,892 15,141.662 4,419,692 7,715,092 3,006,878 2,584,445

ALL M 21,435,818 8,710,166 2,998,273 1,796,543 1,048,231 1,757,138 1,109,981 11,484,559 4,080,980 5,325)884 2,077,695 1,241,093

ALL F 12,429,808 7,429,353 451,768 705,526 465,223 1,501,925 4,304,911 3,657,103 338,712 2,389,208 929,183 1,343,352

W H ITE T 28,343,506 14,571,346 3,272,384 2,321,508 1,337,385 2,958,069 4,682,000 11,996.947 3,910,465 6,011,289 2,075,193 1,775,213

W H ITE M 18,123,927 8,065,782 2,858,908 1,688,268 954,728 1,613,373 950,505 9,232,234 3,637,703 4,185,088 1,409,443 825,911

W H IT E F 10,219,579 6,505,564 413,476 633,240 382,657 1,344,696 3,731,495 2,764,713 272,762 1,826,201 665,750 949,302

MIN T 5,522,120 1,568,173 177,657 180,561 176,069 300,994 732,892 3,144,715 509,227 1,703,803 931,685 809,232

MIN M 3,311,891 644,384 139,365 108,275 93,503 143,765 159,476 2,252,325 443,277 1,140,796 668,252 415,182

MIN F 2,210,229 923,789 38,292 72,286 82,566 157,229 573,416 892,390 65,950 563,007 263,433 394,050

BLACK T 3,684,768 946,196 99,106 77,980 110,123 180,155 470,832 2,131,171 308,541 1,212,599 610,031 607,401

BLACK M 2,163,147 340,831 74,069 40,278 49,200 81,972 95,312 1,527,550 266,634 818,292 442,624 294,766

BLACK F 1,521,621 605,365 25,037 37,702 60,923 98,183 303,520 603,621 41,907 394,307 167,407 312,635

SSA T 1,450,378 402,745 52,038 37,159 41,144 89,546 182,058 883.306 167,261 426,601 289,444 164,327

SSA M 931,373 190,716 44,252 25,989 27,613 46,244 46,618 639,766 147,828 286,645 205,293 100,891

SSA F 519,005 212,029 8,586 11,170 13,531 43,302 135,440 243,540 19,433 139,956 84,151 63,436

ASIAN T 262,606 172,509 15,751 60,015 20,130 19,939 56,674 63,256 16,352 31,835 15,069 26,841

ASIAN M 141,023 90,099 12.691 38,330 13,494 10,981 14,603 36,398 13,085 15,010 8,303 14,526

ASIAN F 121,583 82,410 3,060 21,685 6,636 8,958 42,071 26,858 3,267 16,825 6,766 12,315

AMIND T 124.368 46,723 9,962 5,407 4,672 11,354 15,328 66,982 17,073 32,768 17,141 10.663

AMIND M 76,348 22,738 8,353 3,678 3,196 4,560 2,943 48,611 15,730 20,849 12,032 4,999

AMIND F 48,020 23,985 1,609 1,729 1,476 6,786 12,385 18,371 1,343 11,919 5,109 5,664

APPENDIX C

3a

1969

PAGE 223 SENSITIVE INFORMATION—UNAUTHORIZED DISCLOSURE PROHIBITED

EEOC EEO-1 NATIONWIDE SIC 3 DIGIT

NO. UNITS # 752 SIC — 371 MOTOR VEHICLES & EQUIPMENT

TOT

EMPL

WHITE

COLL

OFES

MGRS PROP TECH

SALES

WBKS

OEES

GLEE

BLUE

COLL CRAET OPES LABOR

SERV

WBKS

ATiTi T 720,244 159,729 53,974 26,635 21,234 4,338 53,548 543,046 94,881 403,755 48,410 17,409

ALL M 644,603 129,265 53,573 25,916 20,283 4,150 25,343 498,965 94,111 366,123 38,731 16,373

ALL F 75,641 30,464 401 719 951 188 28,205 44,081 770 37,632 5,679 1,096

ANG T 599,008 154,557 52,638 26,121 20,677 4,316 50,805 431,940 89,857 307,718 34,365 12,511

ANG M 532,581 125,336 52,244 25,444 19,767 4,129 23,752 395,477 89,155 276,828 29,494 11.768

ANG F 66,427 29,221 394 677 910 187 27,053 36,463 702 30,890 4,871 743

NEG T 104,392 3,981 1,089 263 392 6 2,231 95,844 3,788 83.702 8,354 4,567

NEG M 96,725 2,970 1,084 228 356 5 1,297 89,529 3,745 77,902 7,802 4.226

NEG F 7,667 1,011 5 35 36 1 934 6,315 43 5,720 552 341

SSA T 14,892 714 174 62 83 13 302 13,824 1,006 11,253 1,565 354

SSA M 13,472 544 172 59 80 13 220 12,583 982 10,282 1.319 345

SSA F 1,420 170 2 3 3 162 1,241 24 971 246 9

ORI T 935 358 27 177 62 3 89 566 65 463 38 11

ORI M 865 316 27 174 60 3 52 539 64 438 37 10

ORI F 70 42 3 2 37 27 1 25 1 1

AMT T 1,017 119 46 12 20 41 872 165 619 88 26

AMI M 960 99 46 11 20 22 837 165 593 79 24

AMI F 57 20 1 19 35 26 9 2

PAGE 182 SENSITIVE INFORMATION—UNAUTHORIZED DISCLOSURE PROHIBITED

1974 EEO-1 REPORT SUMMARY OF NATIONWIDE INDUSTRIES

1153—UNITS 317—EMPLOYERS SIC—371 MOTOR VEHICLES AND EQUIPMENT

ALL T 1,075,894 243,251 92,892 50,308

ALL M 935,084 200,737 91,101 47,258

ALL F 140,810 42,514 1,791 3,130

W HITE T 876,129 226,098 87,134 47,880

W HITE M 766,392 187,945 85,597 45,078

W HITE F 109,737 38,153 1,537 2,802

MIN T 199,765 17,153 5,758 2,508

MIN M 168,692 12,792 5,504 2,180

MIN F 31,073 4,361 254 328

BLACK T 167,429 13,535 4,741 1,672

BLACK M .140,622 9,927 4,514 1,392

BLACK F 26,807 3,608 227 280

SSA T 28,169 2,232 669 311

SSA M 24,622 1,766 659 298

SSA F 3,547 466 10 13

ASIAN T 2,255 913 115 465

ASIAN M 1,771 734 109 437

ASIAN F 484 179 6 28

AMIND T 1,912 473 233 60

AMIND M 1,677 365 222 53

AMIND F 235 108 11 7

25,983 6,681 67,307 806,397 157,022 599,118

24,204 6,454 31,720 710,201 155,994 513,592

1,779 227 35,587 96,196 1,028 85,526

24,469 6,526 60,089 631,133 145,061 448,986

22,866 6,305 28,099 560,966 144,208 387,041

1,603 221 31,990 70,167 853 61,945

1,514 155 7,218 175,264 11,961 150,132

1,338 149 3,621 149,235 11,786 126,551

176 6 3,597 26,029 175 23,581

1,093 74 5,955 142,353 9,012 128,448

958 70 2,993 124,803 8,906 107,305

135 4 2,962 22,550 106 21,143

242 60 950 25,196 2,376 19,740

226 58 525 22,144 2,322 17.654

16 2 425 3,052 54 2,086

130 11 192 1,318 206 1,003

114 11 63 1,016 196 758

16 0 129 302 10 245

49 10 121 1,397 367 941

40 10 40 1,272 362 834

9 0 81 125 5 107

50,257 26,246

40,615 24.146

9,642 2,100

37,086 18.898

29,717 17.481

7,369 1,417

13,171 7,348

10,898 6,665

2,273 683

9,893 6,541

8,592 5,892

1,301 649

3,080 741

2,168 712

912 29

109 24

62 21

47 3

89 42

76 40

13 2

4a

Business Week, June 9, 1975, pp. 25-26

U N IO N S

WHEN WORKERS HIT THE STREET—TO SELL

During a recession, the traditional ways to cut inventories

and prevent layoffs include such, devices as shortening the

work week or cutting pay. Last week, Wisconsin-based

Kimberly-Clark Corp. tried a different approach: It took

75 workers off production lines and sent them out into the

street to sell the consumer paper goods, such as Kleenex

tissues and towels and Kimbies diapers, that they produce.

For production workers, it was a chance to

discover a new talent

The move, made with the approval of Local 482 of the

United Paperworkers—and done only with volunteers—re

sulted in additional sales of some $250,000. But, says the

company’s general sales manager, W. M. Bray, who coor

dinated the effort, “ On the numbers alone, we probably

wouldn’t have done it.” An innovator in employee relations,

Kimberly-Clark tried the idea for several reasons:

0 It allowed a blitz attack on 1,461 stores in northern Wis

consin and upper Michigan that are not covered by Kimber

ly-Clark’s usual sales routes. Hitting these seasonal stores

just before the start of their peak tourist season resulted

in purchases of a broader range of products by store man

agers.

■ It gave mill workers a greater appreciation for the sales

job and for the value of producing quality goods. For ex

ample, Sherald Laabs, secretary of the Paper-workers local,

who participated in the program, says: “ When we pack

boxes, we don’t necessarily put all the labels the same

way.” After several days of repacking cases, box by box,

for better display effect, Laabs promises: “ Now, I ’ll try

to get them loaded the same way in the plant.”

APPENDIX D

5a

0 It saved Kimberly-Clark the cost of hiring temporary

helpers to staff a big promotional campaign already sched

uled for late May.

■ For production workers, it was a chance to discover a

new talent. Some workers who showed skill and interest in

sales will be groomed for permanent sales jobs, says John

F. Gillen, regional sales manager.

Though Kimberly-Clark developed this program on its

own, it is not an entirely new idea. International Business

Machines Corp. has for years retrained production and ad

ministrative employees for sales and engineering jobs. Un

der the lifetime employment system in Japan, many major

companies use such schemes as converting factory workers

to salesmen to avoid layoffs. For example, Toyo Kogyo Co.,

which has put 2,500 office and factory workers on eight-

month selling assignments, has seen sales jump some 30%

or 40% since January. The company builds the Mazda car.

In Kimberly-Clark’s case, the program was spurred by

a need to cut inventories rather than the fear of immi

nent, layoffs. Adds President Harry J. Sheerin, “ It fit in

with our philosophy that the best motivated people are in

volved, aware people.”

Once the idea was approved, it took about three weeks to

implement. Union officials, finding no conflict with provi

sions in labor contracts, backed the plan. “ We think we’re

making a good product, and so we’re out helping* push our

product,” says Jack Callaway, the local union president.

Eye contact. After a cram course in salesmanship, the 75

workers who volunteered for sales went to their assigned

areas on Monday, May 19. Forty-six workers called on re

tail stores in Michigan and Wisconsin. The new salesmen

received promises of orders from all stores visited and

commitments from about 75% of them.

Another 29 volunteers helped conduct truckload sales and

set up in-store promotional displays at Chicago-area Mont

6a

gomery Ward stores. Even before advertising began, some

stores were selling ont their truckloads and ordering more.

“ It was just amazing,” says Sherald Laabs, who helped

set up a display. “ As fast as we could set up the boxes,

they were being taken away. ’ ’

Kimberly-Clark says it will repeat the one-week program

in the future “ if conditions are right.” Says Sheerin:

“ This was meant to take care of a short-term challenge.

We don’t know if this will turn out to be a financial bo

nanza, but it has caused a very positive reaction among all

our employees.”

7a

APPENDIX E

The Wall Street Journal, February 6, 1969, p. 1

Keeping Busy

FIRMS TRY A VARIETY OF TACTICS TO

AVOID LAYOFFS IN SLOW TIMES

L ockheed L ends E ngineers T o Ot h e r E mployers ;

S ome M a ch inists T urn P ainter

Furloughed Men May Vanish

By R a lph E. W in ter

Staff Reporter of T h e W all S treet J ournal

What does a company do with, employes it has no work

for?

It may retrain them for different jobs or transfer them

to another office, factory or production line. It may take on

business it wouldn’t ordinarily handle just to give the em

ployes something to do. It may even invent tasks to keep

the workers busy or lend them to another company, until

business picks up enough for them to resume their old jobs.

Indeed, say executives, about the only thing a savvy com

pany won’t do with temporarily unneeded employes these

days is lay them off. Main reason: In today’s tight labor

market, men laid off are almost sure to find other jobs

rather than sit around waiting for recall.

At best, companies say, this means the firm that lays

men off will lose whatever it has spent to train them—•

which, in the case of skilled workers, is likely to be quite

a lot. “ We figure we’d be throwing $25,000 out the window

if we laid off a tool-and-die maker,” says John Bohannon,

industrial relations director of Stanley Works, a New

Britain, Conn., machinery maker.

8a

Buying Repair Work

At worst, executives add, a company may be unable to

find replacements for men it lays off wben time comes to

expand production again. “ Good thing we didn’t lay off

anyone last summer, because we’d never have gotten the

men we’re using now,” says Jacob Kamm, executive vice

president of American Ship Building Co., Lorain, Ohio.

Prior to 1968, his firm had laid off half its repair crews

during the spring and summer ore-shipping season, when

repair work is scarce. Last year it managed to avoid lay

offs—by buying a damaged 11,500-ton ore vessel and set

ting its crew to work overhauling the ship ’s ripped bottom.

American Ship plans to operate the vessel when the ore-

shipping season on the Great Lakes reopens.

Such attitudes are reflected in the national layoff rate,

which last year dropped to a monthly average of 1.2 fur

loughs for each 100 U.S. manufacturing employes. That

was down 14% from the 1967 monthly average and 33%

below the layoff rate five years earlier.

Layoffs, of course, are likely to rise again if a nation

wide economic slowdown or recession erodes employers’

confidence that any workers not needed at the moment will

be needed again soon. But many companies vow they will

continue to try to avoid layoffs as much as possible even

during a recession and predict that the layoff rate will not

climb as much in any future downturn as in past downturns

of comparable severity.

The reluctance to write off costs of training skilled em

ployes who might vanish if they were laid off is one rea

son. Another is a spreading conviction that frequent heavy

layoffs damage a company’s reputation—in its plant com

munities and among workers it might want to hire in the

future.

9a

Loans From Lockheed

Lockheed Aircraft Co., for one, "believes that “ if we don’t

do a better job of offering continuous employment, engi

neers just aren’t going to be interested in coming to work

for us,” says Kay Kiddoo. He recently was named to the

new job of manpower coordinator, in which his chief task

is helping Lockheed divisions find ways to avoid layoffs.

To that end, Lockheed last year set up a plan called

LEND (Lockheed Engineers for National Deployment).

Under it, Lockheed has lent 125 engineers to employers

ranging from the Philco-Ford subsidiary of Ford Motor Co.

to Stanford University until there was work for them at

Lockheed again. The company last year also lent several

hundred tool-and-die makers to Avco Corp. and Nor air

division of Northrop Corp., calling them back later to work

on Lockheed’s program to build the giant “ air bus” jet

liner. Lockheed charges companies that borrow its em

ployes only enough to pay their wages and fringe benefits

while they are out on loan and keeps the employes on its

own payroll.

Whatever comes of such plans in the future, employers’

current attitude contrasts sharply with the recent past.

Periodic layoffs—during seasonably slack times or the in

tervals between completion of a contract and the start of

work on a new one—were an accepted part of life in fac

tory towns even during generally prosperous times. (So

much so that one joke had a worker’s son remarking: “ I

go to school five days, then I ’m laid off for the weekend.” )

The Makework Strategy

The change is measured most dramatically by the will

ingness of many companies to dig up minor assignments

if they can’t think of any other way to keep valued em

ployes on the payroll. Most companies hate to admit this

practice publicly for fear of arousing shareholders’ wrath,

but there ’s no doubt it is growing.

10a

Danly Machine Specialties Inc. of Chicago, for instance,

last summer put eight men to work for two months as

sembling a catalog—at the full pay they normally draw

for the highly skilled task of wiring control panels for

forming presses. A Midwest transportation-equipment

maker similarly assigned a group of highly paid machinists

to paint their machines during a slack period, and an aero

space company told 40 of its engineers to pass their time

“ updating manuals” until the company could put them to

work on a new contract.

A more productive—but still expensive—way to avert

layoffs is to take on work a company has shunned in the

past, for the specific purpose of keeping employes busy at

their normal jobs during what otherwise would be slow

periods. This method is particularly favored by companies

in highly seasonal or cyclical businesses.

Perini Corp., a Framingham, Mass., construction com

pany, for instance, says it bids nowadays with “ sharpened

pencil” for jobs involving considerable inside work that

can be done during the winter, when it used to lay off many

of its crews. It adds that it has spent a good deal of money

to buy wood framing and polyethylene sheets to shield

some construction sites from winter storms so that its

crews can continue working during the cold months. The

work could be done more cheaply in the busy spring and

summer seasons. Perini says—but it might not be able to

find workers then if it let its experienced men go during

the winter.

The steel industry used similar tactics to keep many of

its skilled employes busy last summer and fall during a

production slump brought on by customer inventory-cut

ting (the customers had built up heavy stockpiles as a

hedge against a strike that had been threatened for mid

summer but never came off). A Eepublic Steel Corp. dis

trict manager says he held layoffs to half the number ex

perienced in comparable downturns in the past, largely by

having his own crews perform maintenance work the com

pany usually farms out to independent contractors.

11a

Arguments Inside the Industry

Such policies “ caused some pretty heated arguments last

fall” within the industry, says an administrator for an

other steel company. “ The cost-control people,” he says,

“ wanted more men laid off,” hut “ the operating people

said if we laid off skilled men we wouldn’t be able to get

them back.” At most companies, the operating men won,

but in some cases it was a costly victory. Republic indicated

fourth-quarter profits dropped 48% from the 1967 period—

partly, the company said, because of the cost of “ retaining

on the payroll many skilled employes temporarily not

needed” in normal operations.

Putting temporarily idle workers into training programs

to upgrade their skills or teach them new ones is a par

ticularly popular way to avoid layoffs. Such programs are

not confined to workers who already have reached the

skilled category when layoffs threaten. Marathon Oil Co.

has kept half a dozen roustabouts no longer needed in its

Yates Field in Texas by retraining them to be computer

operators.

Arthur G. McKee & Co., Cleveland-based engineering

firm, has developed several training programs specifically

so that “ in slack times we can keep good people on and

have them studying through seminars and technical read

ing to further their skills,” says E. W. Moerhart, vice pres

ident. At one point last year, when several expected orders

were postponed McKee had 10% of its Cleveland staff in

such training programs, he says.

Engineers as Planners

Aerojet-General Corp. of El Monte, Calif., has developed

a variation of this strategy. Temporarily idle engineers de

velop new business for the company while they also pre

pare themselves to work on that new business if it devel

ops. Aerojet assigns especially talented engineers whose

12a

production projects are being wound up to an Operations

Systems Analysis Group that draws up long-range plans

and does preliminary work on new projects that may

eventually develop into paying programs. Engineers in the

group also function as a ‘ ‘ skills bank” that other Aerojet

divisions can call on for help in tackling special problems.

Intracompany transfers of workers no longer needed in

their present locations are one of the most expensive ways

of avoiding layoffs or dismissals. But companies neverthe

less are trying this strategy, too—and not only for espe

cially skilled people. When Avco Delta Corp., financial sub

sidiary of Avco Corp., moved its headquarters from Lon

don, Ontario, to Cleveland a few months ago, it transferred

at company expense 175 employes, including some 100 sec

retaries and clerical workers.

Hiring new secretaries and clerks in Cleveland would

have been cheaper, but an Avco Delta official indicates the

company was afraid it wouldn’t have been able to get as

many as it needed. “ Good secretaries are extremely diffi

cult to find now, and even competent clerical help familiar

with office routine isn’t easy to get,” he says.

Diversification Helps

Shifting employes from one operation to another is

easiest for companies that have diversified widely—and

some companies say they have diversified at least partly

to avoid mass layoffs. Raytheon Co., Lexington, Mass.,

had to make extremely heavy layoffs five years ago when

its defense work was heavily concentrated in two missile

systems. Since then the company has worked hard to land

many different types of projects from different Govern

ment agencies, and it now works on radar and sonar gear,

space technology, data-handling and communications-sys-

tems projects, among others. One result: It recently ab

sorbed in other projects all employes displaced when one

13a

of its Boston-area plants completed a major contract, a

spokesman reports.

Some of the companies most eager to avoid layoffs say

the chief reason is restrictive nnion rnles that would force

them to lay off employes they wanted to keep, while keep

ing workers they would prefer to lay off, if they did re

sort to furloughs. “ Because of union agreements that rigid

ly enforce seniority, we have to lay off the younger, engi

neering-trained men and retain the older guys who have

experience hut often lack versatility for new types of

work,” grumbles an official of a Midwestern railroad. The

result, he says, is that “ all of us in the railroad industry

are trying to avoid layoffs.”

Much as such union rules may displease companies, the

new management stress on avoiding layoffs naturally

pleases unions. “ I t ’s a very healthy thing,” says P. L. Sie-

miller, president of the million-member International As

sociation of Machinists.

14a

APPENDIX F

The Wall Street Journal, July 31, 1975, p. 1

M a n n in g t h e P a in t B uckets

Dow Chemical Co. in Midland, Mich., early this year

guaranteed employes at major plants that they wouldn’t

be laid off if they agreed to reassignment to construction

and maintenance projects when they weren’t needed at

their regular jobs. The unions agreed to that arrangement,

and Dow employes picked up hammers, wrenches and paint

buckets to handle expansion, modernization and repair

work that is normally contracted out to other companies.

Even some white-collar workers participated. “ It worked

like a charm,” a Dow spokesman says. As demand picked

up, employes went back to their regular jobs.

15a

A PPEN D IX G

Production W orker Em ploym ent and A verage O vertim e Hours

in M anufacturing and M otor Vehicle

Jan u a ry 1974-June 1975

Manufacturing Auto

Average

Production Worker Overtime

Employment Hours

Production Worker

Employment

Average

Overtime

Hours

(000) (000)

1974

January 14,691 3.3 681.9 3.2

February 14,598 3.3 623.5 3.1

March 14,582 3.4 603.3 3.2

April 14,629 2.7 661.3 1.5

May 14,665 3.3 661.9 3.4

June 14,903 3.5 679.1 3.4

July 14,605 3.3 636.3 4.2

August 14,826 3.5 636.8 4.0

September 14,913 3.6 706.9 4.3

October 14,702 3.3 702.0 4.8

November 14,351 2.9 683.3 2.9

December 13,814 2.8 630.0 2.3

Average 14,607 3.2 658.6 3.4

1975

January 13,225 2.2 566.2 1.0

February 12,851 2.2 508.5 1.2

March 12,747 2.2 539.9 1.2

April 12,732 2.2 554.1 1.6

May 12,796 2.2

June 12,996 2.4

N ote : Data not seasonally adjusted.

S ource : Bureau of Labor Statistics.

12307.8.75