Correspondence from Pamela Karlan to Neil Bradley (ACLU)

Correspondence

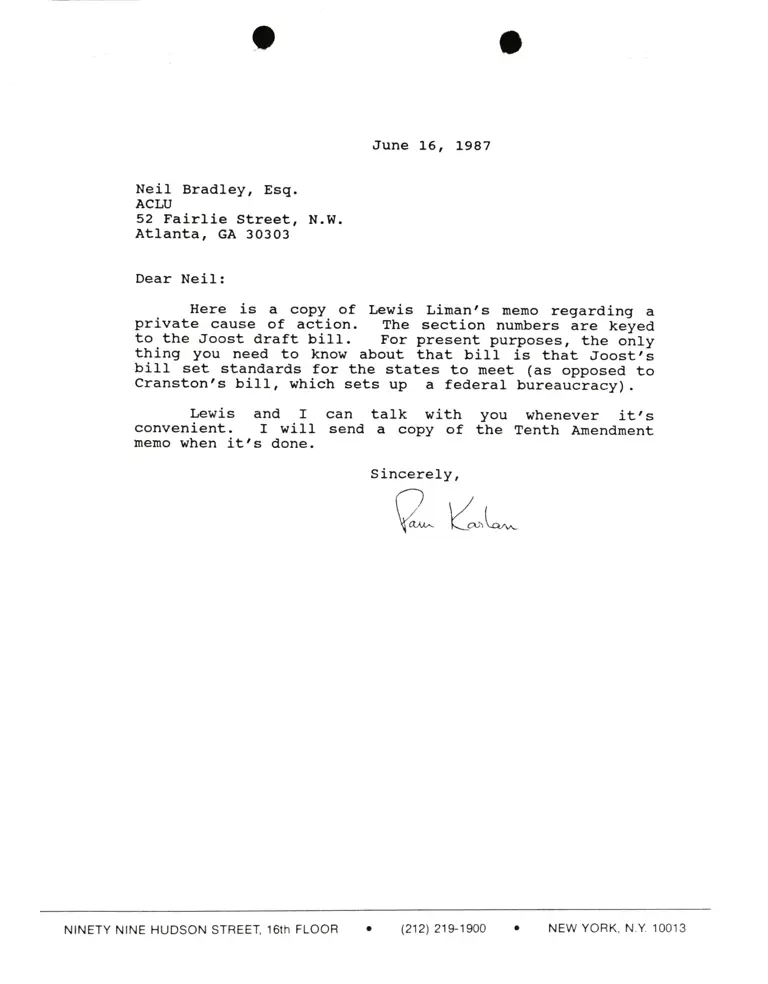

June 16, 1987

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Pamela Karlan to Neil Bradley (ACLU), 1987. 1e6144e7-eb92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c75c36c-d7d5-4ea3-a471-f9a11ee49f98/correspondence-from-pamela-karlan-to-neil-bradley-aclu. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

June L6, L987

NeiI Brad1ey, Esq.

ACLU

52 Fairlle Street, N.W.

Atlanta, GA 30303

Dear Neil:

Here is a copy of Lewis Limanrs memo regarding aprivate cause of action. The section numbers lre keyed

to the Joost draft bill. For present purposes, the onty

thing you need to know about that bilt is that Joostrs

birl set standards for the states to meet (as opposed to

Cranston,s bill, which sets up a federal bureauciacy).

Lewis and f can

convenient. I will send

memo when it,s done.

talk with you whenever itrs

a copy of the Tenth Amendment

Sincerely,

Wa;

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET, 16th FLOOR (212) 21$1900 NEW YORK, N.Y. 10013