King v. Georgia Power Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 11, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. King v. Georgia Power Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1972. b2c28e0b-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c8b3170-892b-4e03-bc41-c9f683c2cd18/king-v-georgia-power-company-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

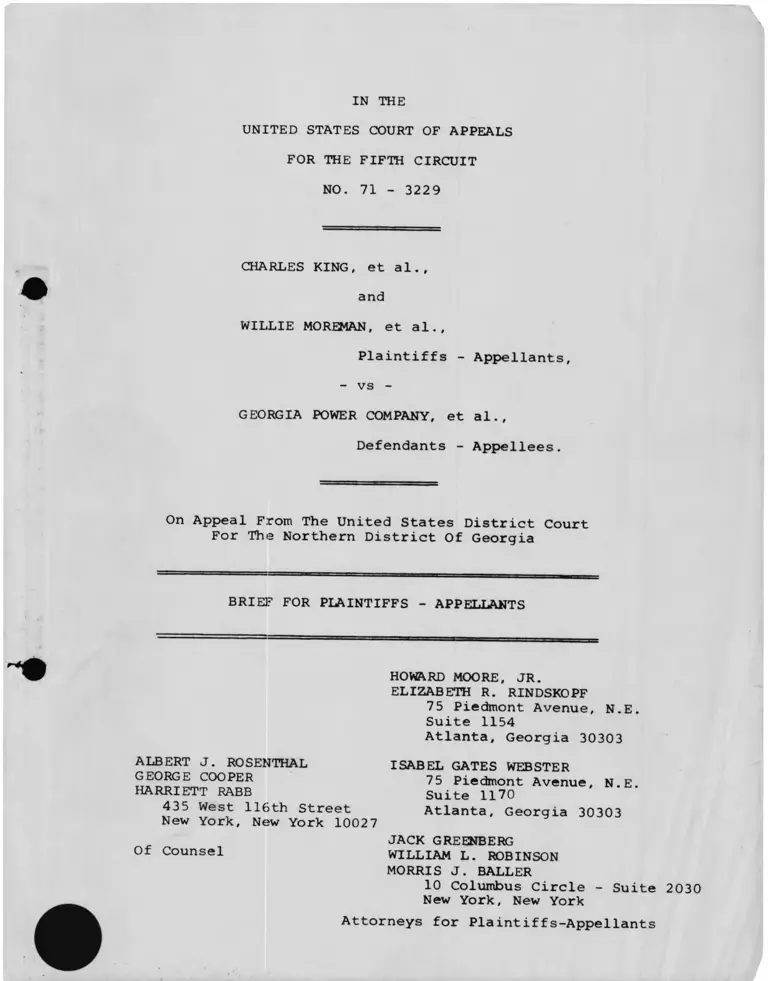

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71 - 3229

CHARLES KING, et al.,

and

WILLIE MOREMAN, et al.,

Plaintiffs - Appellants,

- vs -

GEORGIA POWER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants - Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Northern District Of Georgia

BRIE]?’ FOR PLAINTIFFS - APPELLANTS

HOWARD MOORE, JR.

ELIZABETH R. RINDSKOPF

75 Piedmont Avenue, N.E. Suite 1154

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

ALBERT J. ROSENTHAL GEORGE COOPER

HARRIETT RABB

435 West 116th Street New York, New York 10027

ISABEL GATES WEBSTER

75 Piedmont Avenue, N.E. Suite 1170

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Of Counsel JACK GREENBERG

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

MORRIS J. BALLER

10 Columbus Circle - Suite 2030 New York, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71 - 3229

CHARLES KING, et al.,

and

WILLIE C. MOREMAN, et al.,

Plaintiffs - Appellants,

- vs -

GEORGIA POWER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants - Appellees.

CERTIFICATE

The undersigned counsel for plaintiffs-appellants King, Moreman,

et al. in conformance with Local Rule 13(a) certifies that the follow

ing listed parties have an interest in the outcome of this case.

These representations are made in order that Judges of this Court

may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal:

1. Charles King, Paul Brown, Ed Dulaney, Sammie L. Davenport,

Rufus Mitchell, and Willie C. Moreman, all plaintiffs.

2. The class of black employees of Georgia Power Company whom

plaintiffs represent.

3. Georgia Power Company, defendant.

4. International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers and Local

84 thereof, defendant.

I N D E X

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................................... i

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW................ x

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E .................................. 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS .................................. 4

A. Background information ...................... 4

B. Continuing patterns of discrimination . . . . 9

C. Testing practices............................ 14

D. Assignment practices ........................ 20

E. Recruitment practices ...................... 22

ARGUMENT

I. GEORGIA POWER COMPANY'S USE OF EMPLOYMENT TESTS

VIOLATES TITLE VII SINCE THOSE TESTS EXCLUDE

BLACKS FROM HIRING OR PROMOTION INTO BETTER

JOBS AND SINCE THE TESTS' JOB RELATEDNESS HAS

NOT BEEN ADEQUATELY DEMONSTRATED................ 24

A . The Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures Define the Appropriate Standards

of Test Use. Since Georgia Power's Testing

Practices Do Not Conform To These Standards,They Should Be Declared Unlawful ............ 26

B. Even If This Court Chooses To Develop Its Own Standard For Review Of Validity Data,

It Should Enjoin The Georgia Power Testing

Program. The Hite Study Fails To Demon

strate Job Relatedness Or Business Necessity

As Measured By Any Reasonable Standard . . . . 34

II. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN FAILING TO FIND THAT

GEORGIA POWER COMPANY HAS CONTINUED TO ASSIGN

BLACK HIREES TO MENIAL JOBS ON THE BASIS OF RACE,

DESPITE PLAINTIFFS' UNREBUTTED STATISTICAL

EVIDENCE SHOWING THESE PRACTICES ................ 45

Page

III. GEORGIA POWER COMPANY VIOLATES TITLE VII

BY PLACING PRIMARY RELIANCE ON WORD-OF

MOUTH RECRUITMENT AND WALK-IN APPLI

CATIONS TO FILL JOB VACANCIES, IN LIGHT

OF ITS SUBSTANTIALLY SEGREGATED WORK FORCE ........

IV. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN FAILING TO GRANT

FULL AND EFFECTIVE SENIORITY RELIEF, OR IN

SOME INSTANCES ANY RELIEF, TO BLACKS WHOSE

SENIORITY RIGHTS AND STATUS WERE ADVERSELY

AFFECTED BY DEFENDANTS' DISCRIMINATION ............

A. The Relief Granted By The District

Court Pertaining To Seniority Was

Inadequate And Ineffectual In ManyRespects ..............................

B. This Court Should Correct The Defi

ciencies Of The District Court's

Seniority Remedy In Keeping With Its Duty To Provide Full And Effective

Affirmative Relief From Racial

Discrimination..............................

V. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN FAILING TO GRANT

ADEQUATE TITLE VII RELIEF IN THE NATURE OF BACK PAY........................................

A. The District Court Improperly Limited

The Amount Of Back Pay It Awarded To

The Named Plaintiffs In Allowing Them

Far Less Than Their Actual Loss Due

To Defendants' Discrimination ..............

B. The District Court Erred In Denying

Back Pay To Members Of Plaintiffs'

Class, Even Though The Court Found

That Class Members Had Suffered Severe

Economic Loss Resulting From Defendants' Discrimination..............................

VI. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN LIMITING THE PERIOD

FOR ANY CLASS BACK PAY AWARD BY APPLICATION

OF AN INAPPROPRIATE AND UNDULY RESTRICTIVE STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS ............................

VII. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN LIMITING ITS AWARD

OF ATTORNEYS' FEES TO PLAINTIFFS' COUNSEL BY

APPARENTLY FAILING TO COMPENSATE THEM FOR TIME SPENT AT AND AFTER TRIAL AND BY BASING THE AWARD

ON A SUGGESTED MINIMUM FEE SCHEDULE THAT WAS INAPPROPRIATE FOR THIS CASE..................

48

56

56

65

68

68

71

83

91

CONCLUSION 97

Page

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

?

: Note on Form of Citations..........A-l

: Materials on the Technical

Defects of the Georgia Power

Testing Program and Validity

Study.............................. B-l

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Allen v. Lockheed Corp. 61 LC

H 9333 (N.D. Ga. 1968).................... 95

Baker v. F & F Investment, 420 F.2d

1191 (7th Cir. 1970) .................... 90

Bankers Fidelity Life Insurance Co. v. Oliver,

106 Ga. App. 305, 126 S.E. 2d 887

(Ga. 1962) .............................. 89

Banks v. Lockheed-Georgia Corp., 46 FRD

442 (N.D. Ga. 1968)...................... 95

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp. 46

F.R.D. 56 (S.D. Ga. 1969)................ 77

Beard v. Stephens, 372 F.2d 685

(5th Cir. 1967).......................... 86

Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc. 444 F.2d

687 (5th Cir. 1971)...................... 46,54,65

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting

Corp., 437 F .2d 1011 (5th Cir. 1971). . . . 84

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Company 416

F .2d 711 (7th Cir. 1969).................. 70,75,78

Brazier v. Cherry, 293 F.2d 401

(5th Cir. 1961).......................... 88

Brown v. City of Meridian, 356 F.2d 602

(5th Cir. 1966).......................... 85

Cape Cod Food Products, Inc. v. National

Cranberry Ass'n. 119 F.Supp.

242 (D. Mass. 1952)...................... 95

Carter v. Gallagher, ___ F.Supp. ___, 3 EPD

1(8205 (D. Minn. 1971), aff'd in

pertinent part, ___ F.2d ___, 3 EPDH8335 (8th Cir. 1971).................... 30

Clark v. American Marine Corp. 320 F.Supp.

709 (E.D. La. 1970), aff'd per curiam

437 F . 2d 959 (5th Cir. 1971).............. 82,90,94,95

CONT'D

Clark v. American Marine Corp., 304 F.Supp.

603 (E.D. La. 1969) .................... 51,52,84

Colbert v. H-K Corp., 3 EPD f8248 (5th

Cir. 1971).............................. 95

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co. 421

F . 2 d 888 (5th Cir. 1970)................ 76,88,95

Dobbins v. Local 212, IBEW, 292 F.Supp.

413 (S.D. Ohio, 1968) .................. 93

Dobbins v. Local 212, IBEW, F.Supp. , 61

LC f 9327 (S.D. Ohio 1969)............... 94

EEOC Decisions

Decision 70 - 630 29

Decision 71 - 1418 29

Decision 71 - 1471 29

Decision 71 - 1525 29

Unnumbered Decision (Dec. 6 , 1966) . . . . 29

Evans v. I-T-E Corp., 313 F.Supp.

1354 (N.D. Ga. 1970)................... 95

Franklin v. City of Marks, 439 F.2d

665 (5th Cir. 1971)................... 86,90

Freeman v. Ryan, 408 F.2d 1204 (D.C. Cir. 1968). . 95

Glascoe v. Howell, 431 F.2d 863 (8th Cir. 1970). . 90

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424

(1971).................................. 16,25,29,32,34,

44,51,53,55,62,

63,77,80

Hardin v. Kentucky Utilities Co., 390 U.S.

1 (1968)................................ 33

Hicks v. Crowa-Zellerbach Corp., 319 F.Supp.

314 (E.D. La. 1971)................... 16,30

Hodgson v. American Can Co., Dixie Products,

___ F . 2d ___, 3 EPD f 8171 (8thCir. 1971).............................. 91

Holliday v. REA Express, 306 F.Supp. 898

(N.D. Ga. 1969)........................ 95

Page

- ii -

CONT'D

Huson v. Oatis Engineering Corp., 430 F.2d

37 (5th Cir. 1970)........................ 88

In re Osofsky, 50 F.2d 925 (S.D.N.Y. 1931) ........ 96

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28

(5th Cir. 1968).......................... 77

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express Co., 417

F.2d 1122 (5th Cir. 1969)................ 70,75,77,87,94

Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight Co., 431 F.2d

245 (10th Cir. 1970), cert, denied 401U.S. 954 (1971).......................... 46

Jones v. Montag, 3 EPD H8243 (N.D. Ga. 1969) . . . . 95

Lazard v. Boeing Co., ___F.Supp. , 3 FEP

Cases 643 (E.D. La. 1971)................. 85,90

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 301 F.Supp. 97

(M.D.N.C. 1969) aff'd in pertinent part,

438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971).............. 52,55

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir.1971).................................... 82

Lefton v. City of Hattiesburg, 333 F.2d 280

(5th Cir. 1964).......................... 85

Local 53, International Ass'n. of Heat & Frost

Insulators & Asbestos Workers v. Vogler,

407 F . 2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969)............ 51,53,55,65,

67,79,84

Local 53, International Ass'n. of Heat & Frost

Insulators & Asbestos Workers v. Vogler,294 F.Supp. 368 (E. D. La. 1968)............ 54

Local 186 v. Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing

Co., 304 F.Supp. 1284 (N.D. Ind. 1969). . . 77

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir.

1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970) . . 7,53,64,65,80

Long v. Georgia Kraft Co., F.2d ,4

EPD H7556 (5th Cir. 1971) .

Page

- iii -

95

CONT ' D

Long v. International Brotherhood, 60

LC f9306 (N.D. Ga. 1969)................ 95

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145

(1965).................................. 67,79

Mclver v. Russell, 264 F.Supp. 22

(D. Md. 1967).......................... 90

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc.,

426 F .2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970)............ 82

Miller v. International Paper Co., 408

F . 2d 283 (5th Cir. 1969)................ 67,78,82

Morrow v. Crisler, ___ F.Supp. ___, 4 EPD

H7541 (S.D. Miss. 1971)................ 54

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963)............. 96

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc.

390 U.S. 400 (1968).................... 82,96

NLRB v. Mooney Aircraft, 366 F.2d 809

(5th Cir. 1966)........................ 81

NLRB v. Rutter - Rex Manufacturing Co.,

396 U.S. 258 (1969).................... 80

NLRB v. United Marine Division, Local 333,

417 F. 2d 865 (2nd Cir. 1969) .......... 81

Oatis v. Crown-Zellerbach Corporation, 398

F . 2d 496 (5th Cir. 1968)................ 78

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co.,

433 F.2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970)............ 50,52

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.

411 F.2d 998 (5th Cir. 1969)............ 82

Potts v. Flax, 313 F.2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963). . . . 79

Power Reactor Co. v. Electricians, 367

U.S. 396 (1961)........................ 33

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc. 279

F.Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968)............ 80

Page

IV

CONT'D

Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. F.C.C. 395 U.S. 367(1969).................................... 32

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d

791 (4th Cir. 1971)...................... 75,76,82

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d

1097 (5th Cir. 1970), cert.denied,

3 EPD 18127 (1970)........................ 94,95

S.E.C. v. New England Electric System, 384

U.S. 176 (1966).......................... 33

Shultz v. Wheaton Glass Co., ___F.Supp. ___, 3

EPD 18270 (D.N.J. 1970), aff'd in pert

inent part, ___ F . 2d ___, 3 EPD 182 96

(3rd Cir. 1971).......................... 90

Simler v. Conner, 352 F.2d 138 (10th Cir. 1965). . . 95

Smith v. Cremins, 308 F.2d 187 (9th Cir. 1962). . . . 90

Sprogis v. United Air Lines, Inc., 444 F.2d

1194 (1971) cert, denied ___ U.S. ___,

4 EPD 17588 (1971)........................ 77

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S.

429 (1969)................................ 88

Trinity Valley Iron & Steel Co. v. NLRB

410 F.2d 1161 (5th Cir. 1969)............. 81

Udall v. Taliman, 380 U.S. 1 (1965)................ 32

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446

F . 2d 652 (2nd Cir. 1971).................. 48,64,65,66

United States v. Hayes International Corp., 415

F . 2d 1038 (5th Cir. 1969)................ 46,65,82

United States v. Ironworkers Local 8 6, 315 F.Supp.

1201 (W.D. Wash. 1971), aff'd 433 F.2d 544

(9th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 4 EPD 57526

(1971).................................... 55

United States v. Ironworkers Local 392, 3 EPD 58063

(E.D. 111. 1970).......................... 54

Page

v

C O N T 'D

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Company,

___, F .2d ___, 3 EPD f8324 (5th Cir.

1971).................................... 30,46,47,65

United States v. Plumbers Local 73, 314

F.Supp. 160 (S.D. Ind. 1969).............. 52,54

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36,

416 F . 2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969)............ 46,52,54,65

United States v. Virginia Electric & Power Co.

4 EPD f7502 (E.D. Va. 1971)............... 54

United States v. West Peachtree Tenth Corp.,

437 F. 2d 221 (5th Cir. 1971).............. 45

United States v. Wood, Wire, and Metal Lathers,

Int. U., Local 46, ___ F.Supp. ___, 3

EPD 18204 (S.D.N.Y. 1971)............ .. . 77

Vogler v. McCarty, Inc., ___F.2d ___, 4 EPD

17581 (5th Cir. 1971)..................... 64

Wakat v. Harlib, 253 F.2d 29 (7th Cir. 1958) . . . . 90

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Co., 427 F.2d 476

(7th Cir. 1970).......................... 85

Statutes and Regulations

28 U.S.C. §1291..................................... 1

28 U.S.C. §1652 .................................... 85

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 8 1 ..................................... 85

42 U.S.C. §1982 85,90

42 U.S.C. §1983 85,90

42 U.S.C. §1985 .................................... 90

42 U.S.C. §1988

Page

. 84,85,86

C O N T 'D

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title I I ................ 82

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII,

42 U.S.C. §§2OOOe et seq.................. passim

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2 (a)..................... 52

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2 (a) ( 1)................ 50,52,55

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2 (a) (2) 51,52

42 U.S.C. §e000e-4(f) .................... 32

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5, - 8 .................. 31

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5 (d) .................. 83

42 U.S.C. §2000-5 (g) .................... 54,73,74,75,86

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5 (k).................... 91,92

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-6...................... 3

42 U.S.C. §2000e-6(a)(3).................. 73

42 U.S.C. §2000e-12 (b).................... 32

Equal Employment Opportunities Commission

Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures ,

29 C.F.R. §§1607 et seq. (1970).......... 28

29 C.F.R. §1607.1(c)..................... 28

29 C.F.R. §1607.4 (c) ( 2)................. 34

29 C.F.R. §1607.5 (a) , (b) , (c) ............ 28,33,34,40

29 C.F.R. §1607.5(b) (3)-(4).............. B-9

29 C.F.R. §1607.5 (b) (5)................. B-ll

Page

- vii -

CONT'D

Paae_

Equal Pay Act,

29 U.S.C. §206 .......................... 90

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure,

Rule 30(c)................................ 2

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 23 ........ 5

Georgia Code Annotated

§3-704.................................... 83,85,86,89

§3-706 .................................. 83,85,89

National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C.

§§151 et seq.............................. 79

29 U.S.C. §160 (c) (Section 10(c)..........

Office of Federal Contract Compliance (OFCC)

Regulations

79

Regulation implementing Executive Order

No. 11,246, 41 C.F.R.

Section 5-12.805-51 (b) (5)................ 50

Employee Testing and Other Selection

Procedures,

36 Fed. Reg. 19307 (1971) ................ 30

Pennsylvania Guidelines on Employee

Selection Procedures, a Pa. Bull.

2005 (1971) .............................. 30

Other Authorities

American Bar Association (A.B.A.) Code of

Professional Responsibility,

Disciplinary Rule 2-106 ................ 92

Disciplinary Rule 2-106 (B)(7)............ 94

Disciplinary Rule 2-106 (B) (8)............ 95

Annotation, 56 A.L.R. 2d 13 (1957)................ 92

Blumrosen, The Duty of Fair Recruitment Under the

Civil Riqhts Act of 1964, 22 Rutgers L.

Rev. 465 (1968) ..........................

I.D.J. Bross, Desiqn for Decision (1953)..........

49,50,51

40

- viii-

40

CONT'D

Page

Clark - Case Interpretative Memorandum on Title VII,

Congressional Record (Senate) April 8, 1964)... 80

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598 (1969) . . 7

W.J. Dixon and F.J. Massey, Jr., Introduction to Stat

istical Analysis (2d ed. 1957).................. 42

A .L. Edwards, Statistical Methods (2d ed. 1967)........ 40

J.P. Guilford, Fundamental Statistics in Psychol

ogy and Education,4th ed. McGraw-Hill,

1965 App. B, p. 508, Table D.................... B-4

W. Hays, Statistics for Psychologists (1963)............ 40

McNemar, Quinn, Psychological Statistics. 4th ed.

John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (New York, 1969)........ B-5

C.C. Peters and W.B. Van Voorhis, Statistical Pro

cedures and Their Mathematical Bases (1940) . . . 40

M.H. Walker, Elementary Statistical Methods (1945) . . . . 40

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Whether Georgia Power Company's use of employment

aptitude tests as a screening device for hiring and promotion

violates Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act where such

tests had a substantially disproportionate impact on black

employees and applicants, and where the Company's purported

proof of the tests' job-relatedness does not comply with the

EEOC Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures or any pro

fessionally accepted standards of test validation?

2. Whether the court below erred in refusing to find that

Georgia Power Company has continued to assign black hirees to

menial positions on the basis of race and without regard to

their qualifications as shown by plaintiffs' unrebutted

statistical evidence ?

3. Whether in light of its racially stratified work force

the Georgia Power Company's exclusive reliance on a word-of-

mouth employee referral system and walk-in-hiring violates

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act?

4. Whether the partial seniority relief granted by the district

court was inadequate as a matter of law in that it fails to pro

vide a full and effective remedy to plaintiffs and the members

of their class, with respect to both the necessary modification of

defendants' discriminatory seniority system and the adjustment of

the seniority positions of black employees whose seniority status

was adversely affected by defendants' discrimination?

x

5. Whether the district court erred in limiting its award of

compensatory back pay:

A. by limiting the back pay awards to named plaintiffs

to a minimal amount which was far less than these plaintiffs

would have earned absent defendants' racial discrimination.

B. by refusing to award any back pay at all to members

of plaintiffs' class, even though the court found that

class members had suffered a severe economic loss as a

result of defendants' discrimination?

6 . Whether the district court erred in its limitation of the

period of any class back pay award by applying an inappropriate

and unduly restrictive statute of limitations on back pay relief.

7. Whether the district court erred in its award of counsel

fees to plaintiffs' attorneys where the award did not give those

attorneys any compensation for participation in trial and post

trial proceedings, and where the award was calculated on the

basis of a suggested minimum fee schedule which fails to allow

for the special experience and skill required to litigate these

actions?

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71 - 3229

CHARLES KING, et al. ,

and

WILLIE MOREMAN, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

- vs -

GEORGIA POWER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This appeal involves two cases, each a broad class action

attacking across-the-board practices of employment discrimination

under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e

et seq., which were consolidated for trial and decision below.

The appeal is from the final judgment in these actions of the

United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia,

Smith C.J. This Court has jurisdiction of the appeal pursuant

to 28 U.S.C. §1291.

This complex litigation was instituted by complaints filed

on April 12, 1968 in No. 11723 and on October 28, 1968 in No. 1218b

1/(King complaint, Moreman complaint). Plaintiffs in both actions,

the appellants here, are six black employees of defendant Georgia

Power Company who at the time of filing suit all held laborer jobs.

(King complaint at 2; Moreman complaint at 3.) Defendants in both

actions were the Georgia Power Company, a privately owned utility

providing electrical power and ancillary services throughout Georgia

(Ic[.) , and Local Union No. 84, an affiliate of the International

Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, which represents all the unionized

employees of the Georgia Power Company in its Atlanta power-pro

duction facility (Id.).

The two complaints made essentially identical allegations

concerning the defendants' across-the-board policies and practices

of racial discrimination in employment. The defendants' answers

denied all the substantive allegations of the complaint (King

answers; Moreman answers). The court below on August 18, 1969 con

solidated the two private actions, and defined the class in both

actions to include "All presently employed Negro laborers at the

Atkinson-McDonough Plant of the Georgia Power Company in Atlanta,

Georgia" (Pre-trial Order at 1).

1/ Appellants have elected to proceed under the deferred appendix

system pursuant to Rule 30(c), Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure;

therefore appendix page citations are not available as this brief is filed. All citations are therefore to the original record on

appeal as compiled by the clerk of the district court. The forms

of citation used in this brief are explained in the Note on Form

of Citations, Appendix A hereto.

2

Subsequent to the filing of these private actions, the

United States on January 10, 1969 filed a pattern and practice suit

against the same defendants under §707 of Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

2/§§2000e-6 (U.S. complaint). The district court on June 23, 1970

ordered the United States suit consolidated with both private actions

for trial. From that date onward, many class aspects of the private

actions were litigated as part of the pattern-and-practice action.

On July 13, 1970 the United States filed a motion for pre

liminary injunction requesting relief for certain classes of black

employees (Motion for Preliminary Injunction). After an evidentiary

hearing, the court on September 22,1970 entered findings of fact,

conclusions of law, and an order on the United States' motion

(Preliminary Injunction). As modified by the court's order of

October 5, 1970 this preliminary order granted part of the relief

sought by that motion (Amended Preliminary Injunction).

On November 30, 1970 a third private individual action,

George Jones v, Georgia Power Company, C.A. No. 14182, was con-

2/solidated for trial. All the consolidated cases came on for

hearing on January 18, 1971; the trial lasted seven days.

2/ While the United States suit presented many essentially identi

cal questions of fact and law, it was broader in scope than the plaintiffs' private actions. United States v. Georgia Power Company,

et al., C.A. No. 12355, challenged defendants' practices statewide,

and joined as defendants seven local unions of the IBEW which represent Georgia Power Employees at various locations throughout

the state.

3/ No appeal has been taken from the court's final judgment

in No. 14182, and that matter is not before this Court on appeal

3

Following trial on the merits and the filing of various post

trial pleadings, the district court proceeded to enter its opinion

4/on the merits on June 30, 1971 (Opinion). This decision incorp

orated and modified the court's previous order on the motion for

preliminary injunction, and added additional findings and con

clusions. In general, the court held some but not all of defendants'

contested practices in violation of Title VII; and granted some but

not all of the relief plaintiffs requested from those practices

which it found discriminatory. The final decree in the private

actions was filed on October 22, 1971 (Private decree). This decree

incorporated by reference many aspects of the decree filed pre

viously in the United States case on September 27, 1971 (US decree).

On November 9, 1971 plaintiffs King, Moreman, et al. timely

filed their Notice of Appeal from the final judgment entered in the

private actions (Notice of Appeal). On this appeal plaintiffs

seek reversal both of the district court's findings that certain

of defendants' practices do not violate Title VII, and of its

failure to grant adequate relief from those practices which it did

find discriminatory.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A . Background Information

These actions were instituted by complaints filed on April

12, 1968 and October 28, 1968 (King complaint, Moreman complaint).

Each complaint broadly alleged that defendants were engaged in a

4/ The decision is not as of this date officially reported; how

ever it appears in the labor law reports at 3 EPD f8318 (CCH

Reporter) and 3 FEP Cases 767 (BNA Reporter).

4

comprehensive policy and practice of racial discrimination with

respect to the terms, conditions, and benefits of employment (Id..) .

Each of the six named plaintiffs is a black man who worked

for Georgia Power in the job classifications of laborer and was a

member of one of the defendant unions at the time these actions

5/were instituted. Each plaintiff sought promotion or advancement

into a better and higher-paying job than laborer, but had been

denied such advancement pursuant to defendants' policies and

practices (King complaint at 2, Moreman complaint at 3). The

plaintiffs brought these actions as class actiorfeunder Rule 23,

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, on behalf of all other similarly

situated black persons (King complaint at 3, Moreman complaint at 2)

Defendant Georgia Power Company (hereafter "Georgia Power"

or the "Company") is engaged in the business of production, dis

tribution and sale of electric power and related services through

out the state of Georgia, with its principal office at Atlanta

(Opinion at 6-7). The court found that Georgia Power employed

7,515 persons as of December 25, 1970, of whom 6,891 were white

and 524 were black [sic.] (Opinion at 7). Defendant Local Unions

are affiliated with the International Brotherhood of Electrical

Workers (hereafter "IBEW") and each represent workers in a separate

5/ Plaintiffs Charles King, Ed Dulaney, Sammie L. Davenport,Paul Brown, Rufus Mitchell, and Willie C. Moreman were all laborers

at Plant McDonough-Atkinson in Atlanta from the time these actions

were instituted until 1969 or later; all were members of defendant

Local 84.

5

geographical division of the Company. These unions together re

present 3,853 employees as their exclusive collective bargaining

agent with respect to rates of pay, wages, hours of employment,

working conditions, and other terms of employment (Opinion at 7).

All of these unions have entered into a single collective bar

gaining agreement with the Company (Id̂ .) The current bargaining

agreement became effective on April 29, 1969. It replaced the

prior agreement of July 1, 1965, and was to continue in effect

until June 30, 1971 and from year to year thereafter subject to

amendment by the parties (Opinion at 9).

All Georgia Power employees in bargaining unit jobs held

jobs in one of four organizational parts of the Company, each

vincluding one or more administrative units. Each of these * 2 3 4

6/

6/ Local 882 represents employees at Athens; Local 84, at Atlanta;

Local 923, at Augusta; Local 780, at Columbus; Local 876, at Macon;

Local 847, at Rome; and Local 511, at Valdosta (Opinion at 7). There

are no other unions which represent Georgia Power employees. Only

Local 84 was a defendant in the private actions. See n.2, supra.

7/ (1) The Production Department is a statewide administrative

unit for purposes of promotion, transfers, demotion and layoffs;

its function is the production of electrical energy at the Company's steam and hydroelectric generating plants.

(2) Seven geographic operating divisions with headquarters

at Athens, Atlanta, Augusta, Columbus, Macon, Rome and Valdosta

form separate administrative units for purposes of promotion,

transfer, demotion and layoffs; their function is the transmission,

distribution, and sale of electrical energy and appliances.

(3) The Construction Department is divided into three parts,

Plant Construction, Line Construction and Substation Construction,

each of which is a separate statewide administrative unit for pur

poses of promotion, transfer, demotion and layoffs.

(4) The General Sex-vices Department is a statewide admin

istrative unit whose functions include maintenance of many Company

vehicles and, at Atlanta, a variety of special services.

The majority of non-bargaining unit employees work in the Atlanta general headquarters. There is no seniority system with respect to these employees (Opinion at 7-8).

- 6 -

administrative units is a separate "seniority division" for pur

poses of determining employees 1 seniority rights under the collect

ive bargaining agreement (Opinion at 8).

The collective bargaining agreement sets forth each job

classification covered by the agreement and its rate of pay, and

sets forth the "sections" in which each job classification is con

tained (Opinion at 9). There are currently 19 such sections in the

Company, each containing one or more lines of progression comprised

of (usually) functionally related jobs through which employees pro

gress from entry level jobs to successively higher paying jobs

(Id.). The collective bargaining agreement also sets forth the

principles of seniority which govern employees' rights with respect

to promotion, transfer, demotion, and layoff. Employees may ex

ercise seniority only in the seniority division and section where

they work (Opinion at 9-10). The seniority system is generally of

8/

a rigid "job-seniority" type. Promotions are awarded (compe

tency being sufficient), and demotions due to lack of work are

allocated, on the basis of classification (job) seniority within

9/the employees 's seniority division and section (Iĵ .) .

8/ See Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598, 1602-1604 (1969), and Local

189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v. United States, 416

F .2d 980, 983 (5th Cir. 1969).

9/ The court found: "First preference in filling a job vacancy

is given to the senior employee, competency being sufficient, in

the same classification in the same section and division where the

vacancy exists, requesting such transfer. If no such employee re

quests a lateral transfer, the vacancy is filled by the promotion

of the most senior employee, competency being sufficient, in the

next lower classification in the section and seniority division

requesting such promotion . . . The classification to which an

employee is demoted depends upon his combined seniority in his

classification and lower classifications at the time of demotion

as compared to the combined seniority of the employees in the lower classification" (Opinion at 10).

7

Cross-section transfer is permitted, but the transferring employee

is treated as a new employee in his new section, without carry-

over seniority or return rights to his former job (Opinion at 10).

The effect of this rigid job seniority system has been to dis

courage employee movement between classifications except within and

along the established lines of progression, as an inspection of

data in the record amply demonstrates (Gov. Ex. 7, 15, 17

[suppl.]).

This system of seniority is the route to promotion, and the

means by which employees of Georgia Power Company seek and obtain

successively higher paying jobs. Its significance in that regard

is self-evident. In the context of this case, however, the

seniority system has been used by Georgia Power Company in con

junction with a wide range of other devices, some subtle, and

others overt, to maintain a strict racial stratification of its em

ployees throughout the Company. While these devices are discussed

separately below, their cumulative impact has been to relegate the

Company's black employees to the lowest paying, most menial jobs

in the Company, while depriving them of all hope of advancement.

10/

10/ The court found: "Employees may transfer from one section

to another, but they may not transfer seniority gained in the

former section to the new section. While seniority retained in

a former section may not be used in his new section for any purpose,

in a case of layoff due to lack of work in his present section such

retained seniority may be used in the former section as his pro

tection against layoff, [citation omitted] If an employee has

made a cross-section transfer and is deemed to be incompetent in

his new classification he cannot exercise his seniority rights

for the purpose of regaining his former classification, but is

subject to possible discharge". (Opinion at 10).

8

B.

Prior to July 29, 1963, Georgia Power followed an open and

unvarying policy of limiting black employees to the most menial

jobs. Blacks in jobs covered by the collective bargaining agree

ment were relegated to the classifications of laborer, janitor,

porter and maid, the four lowest paying jobs in the bargaining

unit. These jobs were completely dead-end; they were in separate

lines of progression, and at least until that date transfer out

was absolutely prohibited. All of the other jobs, available only

to whites, paid more at the start and offered continued oppor

tunities for further advancement (Opinion at 12).

On July 29, 1963, three black laborers were for the first

time permitted to transfer to other jobs. The court below seems

to have treated this date as a watershed event, when discrimina

tion against blacks came to a halt (Opinion at 45). The court be

low made no specific finding of fact to this effect, however —

as indeed, on this record, it could not. Not only does the record

contain no evidence that opportunities to transfer were thence

forth made available to black employees on any significant scale;

now, over seven years later, the percentage of company employees

who are black has actually dropped, and the overwhelming majority

of black employees are still locked into the lowest paying, least

attractive jobs (Gov. Ex. 14).

We show below that Georgia Power continued to discriminate

against black employees after July 29, 1963 by its use of unlawful

employment tests and its practices of job assignment and recruit

ment. Each of these contentions was rejected by the district court

Continuing Patterns of Discrimination

9

and is in issue here. But, apart from these contested issues, the

record is replete with facts which were either found as true by the

district court or are not open to serious dispute by the parties,

and which clearly constitute examples of continued discrimination.

1. Until April 29, 1969, months after the institution

of these lawsuits, Georgia Power's black employees had no seniority

rights whatever which could be exercised for purposes of promotion,

advancement, or transfer. This situation was assured by the

singular status, under the 1965 and earlier collective bargaining

agreements, of Sections 17, 18, and 19. These sections consisted

of the job classifications of Laborers, Janitors, and Porters, and

Maids, respectively (Opinion at 11). These jobs, the lowest-pay-

11/ing in the Company (Opinion at 12), were and are black jobs.

Until April 29, 1969, all four jobs continued to be in separate

dead-end lines of progression, and employees in those job class

ifications had no seniority applicable to any other jobs in the

Company (Opinion at 11).

2. The collective bargaining agreement effective April

29, 1969 gave laborers, for the first time, limited seniority

rights for promotion and advancement in other lines of progression.

However, these black laborers were placed at the bottom of their

respective lines of progression and granted only job seniority in

11/ No whites have ever held the jobs of Porters, Janitors, and

Maids (Opinion at 13). Prior to July 29, 1963 all black employees

were in one of those job classifications or that of Laborer

(Opinion at 12). Prior to July 2, 1965, a great majority of white

employees were immediately assigned to higher-paying and more

responsible jobs than the four black jobs (Opinion at 12).

10

their entry-level jobs. They remained, therefore, not only

behind all their white contemporaries, but also behind all later-

hired whites who were assigned to entry level jobs in the non

laborers lines of progression at any time prior to April 29, 1969.

Defendants maintained this system until its modification was ordered

by the district court's decree of September 27, 1970 (US decree).

3. Even after July 29, 1963, defendants continued to

assign all newly-hired black employees to the job classifications

of Laborers, Janitors, Porters, and Maids. All 156 blacks hired by

Georgia Power in the period July 29, 1963 to June 9, 1969 were so

assigned, irrespective of their qualifications (Gov. Ex. 7,

Gov. Ex. 15 [suppl.]).

4. Janitors, porters and maids -- all of whom still are

black -- are still in separate "lines of progression". The ex-

12/

12/ The court found: "Under the terms of the current collect

ive bargaining agreement between the Defendant Company and

Defendant Unions, the Laborer's job classification (formerly

separate) has now been made the entry level job classification in

the lines of progression in 15 of 19 sections as that term is used

in the collective bargaining agreement, [citation omitted] The

term "entry level job" as used in this paragraph means simply the

job that pays lowest in a particular line of progression.

"As a result of the current collective bargaining agreement,

"Section XVII, Laborers in Any Department of the Company, in the

1965 Collective Bargaining Agreement" was abolished and persons

assigned to that section in which they were working as of April 29,

1969. The persons affected in this instance retained the section

seniority which they had accumulated in Section XVII and it became

their section seniority in the section to which they were assigned. . . " (Opinion at 10-11)

The former laborers' exercise of their Section XVII seniority

remained, of course, subject to defendants' other requirements

for promotion or transfer, most notably the tests.

11

pression is deceptive, since there is nowhere to progress to in

those lines.

5. The collective bargaining agreement effective April

29, 1969 created the new job classifications of "switchmen" and

"coal samplers" as purportedly nDn-laborer jobs. No whites have

ever held these jobs (Opinion at 14). In fact, they are laborers’

jobs, paying considerably less than the lowest paying white job13/(Gov. Ex. 2 ) .

6 . Earnings of black employees have been substantially

lower, when matched against those of their white contemporaries

and even against some later hired whites (Opinion at 41). Of the

Company's employees covered by the collective bargaining Agree

ment, hired between July 2, 1965 and September 6 , 1968 (after these

suits were instituted), 788 were white and 89 black. Their monthly

salaries as of September 6, 1968 break down, by race, as follows

(Opinion at 16) :

Monthly Salary White Black Percent Black

Over - $800 0 0 0$700 - $800 0 0 0$b00 - $700 15 0 0$500 - $600 517 0 0$400 - $500 236 1 0.4Under- $400 20 88 81.0

TOTAL 788 89 1 0 . 1

13/ Those two jobs were referred to in the proceedings below

by all parties and the court as "laborers" jobs. The reason is that

prior to April 29, 1969 the duties performed by switchmen and coal samplers were performed by laborers. On that date, the newly

agreed upon contract "reclassified" those laborers performing that work as switchmen and coal samplers, and provided for a token wage increase of $20 per month (Gov. Ex. 2).

12

7. Although some whites--albeit only a few— were

initially employed as laborers, the longest any such white who was

hired between July 29, 1963 and January 9, 1970 remained a laborer

was thirteen months, and the average time spent by whites as

laborers before promotion to a better job was three months and one

week (Gov. Exhs. 6 , 7, 15, 17 [suppL]). During the same period, how

ever, all of the blacks started as laborers, only 13 out of 95 have

been promoted since, and even they remained laborers an average

of two years and nine months (Id.).

8 . Apart from the forms of discrimination relating direct

ly to opportunities for transfer and promotion, the Company dis

criminated in other respects in its treatment of black applicants

and employees, causing the court below to enjoin continuation or

resumption of such practices. These include discrimination in re

imbursing employees for expenses incurred in working away from

home (Opinion at 23-24), and in treatment of applicants (Opinion

at 24-25) . As to hiring, the court noted that some of the Company's

"supervisory personnel have unilaterally engaged in acts to dis

courage, confuse, and by-pass blacks in favor of whites" (Opinion

at 46). Examples cited by the court include informing an apparent

ly qualified black that there were no openings and then hiring a

white shortly after; receiving a black's application when there is

no opening but not referring to it when one develops; the company's

"frequent practice of hiring white employees, when the applications

of equally or better qualified blacks are on file";its "practices

of informing black applicants that no openings are available when

in fact vacancies are available", "of informing blacks that

13

vacancies rarely occur when in fact they occur often", "of inform

ing blacks that they must begin as laborers when in fact a large

number of white employees begin at a higher classification", "of

telling black applicants that they will be called if a vacancy

occurs and failing to call them", and "of failing to inform black

applicants that they should apply at a different location for cer

tain jobs in which they express interest" (Opinion at 46-47).

The cumulative effect of so many types of discrimination in

so many parts of the company's operations serves, as a very minimum,

to dispel once and for all any notion that Georgia Power stopped

discrimination against blacks on July 29, 1963.

C. Testing Practices

On July 29, 1963, Georgia Power Company, for the first time

in its history, ostensibly ceased using race as a basis for restrict

ing all blacks to laborer category jobs and announced that black

employees would be allowed to advance into jobs above the laborer

classification (Opinion at 12). However, less than a month later,

on August 19, 1963, the Company imposed a new hiring and pro

motion requirement which had the effect of substantially rein

stituting the policy of excluding blacks from better jobs. This

new requirement required all incumbent employees seeking transfer

from formerly all-black job classifications (laborer, janitor,

porter, and maid), and all persons seeking new employment in job

classifications other than these classifications to take and

achieve a pre-determined passing score on each of one or more

aptitude tests. Incumbent employees in all other job classifica

tions -- the formerly all-white classificatinns -- had never been

and were not now required to take or pass any aptitude test

14

in order either to be promoted in their present lines of progression

or to be transferred to new lines of progression (Opinion at 13).

These new tests have effectively blocked any substantial upward

movement by blacks.

The Georgia Power Company's test requirement includes nine

different employment tests. Persons assigned to any job in the

"manual and hourly classifications" must pass both the verbal and

numerical components of the Personnel Tests for Industry (PTI-V

and PTI-N). In addition, assignment to several of these class

ifications also requires passing the Bennett Mechanical Compre

hension Test (Bennett). Jobs in the "office and clerical class

ifications" require passing of the Short Employment Tests (SET),

and applicants for several of these classifications must also pass

the General Clerical Test (GCT). All persons assigned to jobs in

the "technical classifications" must pass the PTI-V and the PTI-N.

In addition, several jobs within the "technical classifications"

also require the Bennett, and for several other jobs in technical

classifications persons must pass the Revised Minnesota Paper

Form Board Test along with the PTI. Finally, persons seeking jobs

in "miscellaneous classifications" — home economist and mer-

14/chandise salesmen -- must pass the Wonderlic Personnel Test

(Co. Ex. 1-B).

In every case the employee must pass every test required for

the job. Once an employee passes the entire test battery he be-

14/ The tests required for each position and the required scores

are set forth in Appendix B to this brief, p. B-3 .

15

comes eligible for promotion into all jobs in the line of pro

gression without ever being retested. If he fails to achieve the

passing score on any one of the tests required, he is denied the

job, regardless of his other qualifications or scores on the other

tests (Opinion at 29). This inflexible requirement applies to any

job outside the laborers' category, including the entry level

helper jobs in traditionally white lines of progression. Thus,

plaintiff Charles King, who successfully passed two of the tests

and failed the third by only one point, was ineligible to become

a helper (Co. Ex. 83) .

The Supreme Court has already acknowledged that two of the

tests used by Georgia Power, the Bennett and the Wonderlic, have a

grossly discriminatory impact on blacks. Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., 401 u.S. 424, 430 (1971); see also Hicks v. Crown-Zellerbach

Corp., 319 F.Supp. 314, 319 (E.D. La. 1971). The other tests have

similar discriminatory effects. The district court below found

that "as a general rule, black people score significantly lower

than do white people on aptitude and intelligence teste of the

type used by Georgia Power Company" (Opinion at 30). The full

extent of this discriminatory impact is not clear from the record,

since the only data available consisted of test scores of present

employees tested and hired since 1968. This group included very

few blacks. Blacks had until recently been discriminatorily

excluded from testing through the company practice of assigning

most blacks to laborer positions without testing and having them

16

sign "waiver of promotion" forms. Within this post-1968 group,

which is in no sense a random sample, blacks generally do far less well

16,than whites on the tests used by Georgia Power Company (Gov. Ex. 12).

Approximately one year after the adoption of these tests by

Georgia Power Company, John Hawkins revised the passing score re

quirements for the test. Hawkins, a political science major and

admittedly not a professional psychologist, worked alone. These

revised scores were based on a visual, and acknowledgedly non-

statistical, study of how test scores related to job performance

(6 Tr. at 203-213). Georgia Power undertook no further study until

the institution of this action. The test and passing score re

quirements as fixed by Hawkins have remained in effect to date,

15/

15/ These "waiver of promotion" forms were regularly required even

of high school graduate blacks, and were often requested without any

explanation of the implications, or opportunity to take the tests.

Prior to the filing of this suit, only one white had signed a similar

waiver. During the period from January 1, 1968 to March 20, 1970, for which complete data are available, 62 blacks and only 9 whites

executed waiver forms. (1 Tr. 45, 102, 127, 129, 179, 186, 189, 223,

231; 2 Tr. 43, 45, 121-122, 130, 221, 231; Gov. Ex. 6 , Co. Ex. C,Co. Ex. 6 , Gov. Ex. 12).

16/ The following shows the comparative rates of failure for blacks and whites within this sample group.

Test Blacks Whites

PTI-V 30.0% . 94%PTI-N 43.0% 1.25%Bennett 37.5% .85%SET 18.0% .003%GCT 56.0% .00%Minnesota no blacks tested 4.00%

Source: Gov. Ex. 12.

The district court also found, for this group, that blacks scored 9-12 points lower than whites on the Georgia Power tests

(Opinion at 30-31).

17

except fot minor modifications ordered by the district court

(6 Tr. 165, Co. Ex. 1-B, US decree at 3).

In December 1968, Georgia Power Company began a study of its

testing program under the direction of Dr. Lorain Hite, an indus

trial psychologist, which was completed just shortly before the trial

commenced (Opinion at 33; 6 Tr. 35). This study is reported as

"Validation Data and Procedures for the Employment Testing Program

of Georgia Power Company" (Co. Ex. 75). At trial Dr. Hite also

testified concerning a summary sheet of data derived during the

preparation of this study (Gov. Ex. 41) .

Dr. Hite's study is limited to validation data for only

thirteen of the company's over fifty job classifications. He did not

even attempt validation for the Minnesota test and the Wonderlic

test. The PTI tests, the Bennett test, the SET tests, the GCT tests

were studied, where appropriate, for only these thirteen job class

ifications. For at least one line of progression at the Company -

the serviceman line - no job within the line was included under the

study (Co.Ex. 75; Co. Ex. E).

Dr. Hite in the course of this study tried at least three

different statistical procedures (discriminant function analysis,

multiple regression analysis, and a statistical comparison of the

performance of tested versus non-tested personnel), in an attempt to

find some basis for justifying test use. However, he placed primary

reliance on discriminant function analysis (Co. Ex. 75, p. 1), in

implementing this analysis, as reported in the study, Dr. Hite used

statistical techniques to produce an optimal weighting of test scores,

which differed for each job. His study reports data only as to the

use of tests in accordance with that optimal weighting. In every

18

instance this weighting is inconsistent with the company's existing

use of the tests, and in many cases grossly inconsistent. Thus,

for the lineman classification, the optimal test weighting called

for elimination of the PTI-V score, contrary to the company's

practice. For seven of the twelve reported classifications, under

the discriminant function analysis — appliance servicemen, store

keepers, helpers, coal equipment operators, meter readers, switch

board operators, and garage mechanics — the optimum formulae

assigned negative weights to at least one test, thus suggesting that

persons scoring lower on the test should be given preference over

higher scorers, contrary to the company's present practice (Co. Ex. 75)

Even if the tests had been used according to Dr. Hite's op

timal weighting, his own summary data sheet (Gov. Ex. 41) reveals

that under the discriminant function analysis the results reported

satisfy standard measures of statistical significance only as to two

17/of thirteen job classifications reported upon. The multiple re

gression results are statistically significant for no job class-18/ —lfication (Gov. Ex. 41).

The District Court agreed that Dr. Hite's results indicated

that the tests were not of "significant help to the Company in pre

dicting job performance of applicants" for at least four jobs --

switchboard operator, garage mechanics, coal equipment operators,

and helpers (Opinion at 34). Based on this finding, the court en-

17/ See pp.40 - 43, infra, and Appendix B, pp. 4-5 , infra, for dis

cussion of the concept of significance and its application here.

18/ See p . 41 n,39, infra, and Appendix B, pp. 4- 5 , infra.

19

joined further use of the tests as to three of these four jobs

(US decree at 3). However, the tests remain in use, without any

change or modification from the company's longstanding practice, for

the fourth job (helper), and for all other jobs at the company. As

a practical matter this means that passage of the test battery is

a prerequisite to any significant promotional opportunity in the

Georgia Power Company.

D. Assignment Practices

As shown above, until July 29, 1963 Georgia Power Company

restricted all black employees to laborer category jobs as a matter

of policy (Opinion at 12, 41). On that date, the Company announced

a policy change with respect to allowing blacks to compete for pro

motion, but remained silent as to its policy with respect to the

initial assignment of blacks. The record in this latter regard

clearly demonstrates that no change in the Company's policy of

assigning black hirees to laborer jobs exclusively was contem

plated; or if such a change were contemplated, it was certainly

not implemented. Georgia Power continued to exclude virtually all

blacks, regardless of their qualifications, from assignment to jobs

higher than laborer until at least 1969, long after these actions

had all been filed.

In the period July 29, 1963 to June 9, 1969, all 156 blacks

hired by Georgia Power were intially assigned to laborer jobs, irre

spective of their qualifications (Gov. Ex. 15 {suppl.], Gov. Ex. 7).

Although most of these black hirees admittedly did not meet Company

20

standards for non-laborer jobs, this fact cannot explain the assign

ment of all these blacks to laborer positions. In most cases,

Georgia Power did not allow blacks an opportunity to qualify: 41

of these 156 persons had high school degrees (Gov. Ex. 17 [suppl.],

Gov. Ex. 6 , 7), but only seven of them were tested prior to hiring

(Gov. Ex. 15 [suppl.], Gov. Ex. 6 ). Two of those tested before hir

ing passed the tests, but both were nevertheless assigned to laborer

jobs (Gov. Ex. 15 [suppl.], Gov. Ex. 6 , Gov. Ex. 7). A total of 28

black post-July 29, 1963 hirees were fully qualified under the

Company's standards by January 16, 1970 (Opinion at 18, 44). Of

these 28 black employees, 23 were initially assigned to laborer

jobs and only five were initially assigned to higher jobs (Id.).

Even the latter finding of the trial court insufficiently sets

forth the facts, in that it fails to indicate that all five blacks

assigned to non-laborer jobs were employed after June 9, 1969, as

the record shows (Gov. Ex. 15 [suppl]. Gov. Ex. 14 [suppl.],

Gov. Ex. 7).

Georgia Power accorded white employees hired after July 29,

1963 markedly different treatment. The court below found that of

627 whites hired between July 29, 1963 and January 10, 1969 in the

Steam Plants, General Repair Shop, and Atlanta and Macon Operating

Divisions, 534 were assigned to jobs other than laborer

19/

19/ We argue elsewhere that these standards were unlawful, and

the Court so found with respect to the high school education requirement.

21

(Opinion at 19). The court further found that 542 of the 600 whites

hired between July 2, 1965 and January 16, 1970 in the Steam Plants

were assigned to non-laborer jobs (Opinion at 15). Moreover, white

hirees were given every opportunity to qualify for higher level

jobs. For example, of 624 whites hired into the Steam Plants and

Atlanta and Macon operating divisions between July 29, 1963 and

June 9, 1969, 594 were tested piror to their hiring; and of the 30

not tested and therefore not qualified for non-laborer jobs, 25

were initially assigned to higher level jobs anyway (Gov. Ex. 17

[suppl.], Gov. Ex. 14 [suppl.]).

21/E. Recruitment Practices

22/

As set forth above, virtually all Georgia Power's black em

ployees have been relegated to the lowest-paying jobs in the Company,

in the laborers category, while white employees monopolize jobs in

in the higher classifications. The court below found that Georgia

20/

2_0/ The court also found that the other 93 white employees re

mained as laborers for an average of only three months and one

week prior to being promoted into a higher job (Opinion at 19)

By way of contrast, education- and test - qualified blacks remained

as laborers for an average of two years and nine months before being

promoted (Gov. Ex. 4, 5, 12; Co. Ex. 7). The court below obscured this glaring contrast, but admitted that "black employees in the

laborer classification average a longer period of time than whites prior to promotion" (Opinion at 16).

21/ The court below stated that "'[r]ecruiting' relates to affirmative efforts by the company to attract applicants, while 'hiring'

relates to the processing of applicants regardless of their source."

(Opinion at 45-46). Appellants adopt this distinction in this part of the brief.

22/ See pp. 9-13, supra.

22

Power relies to a substantial extent on word-of-mouth recruitment

by incumbent employees as a method of informing persons of job

vacancies and of finding persons to fill those vacancies (Opinion

at 28). It also found that "many" employees of both races had

learned of job vacancies through incumbent employees; approx

imately 30 percent of the persons employed by the Company as of

January 16, 1970, had friends or relatives working for the Company

at the time of their employment (Ic3.) . The Company also places

substantial reliance on walk-in application as a method of obtaining

applicants for vacant positions (1 Tr. 167; 2 Tr. 8, 170; 4 Tr. 213).

The court found that most of the engineering colleges at

which the Company maintains recruitment programs have predominantly

white student bodies (Opinion at 29). The Company relies primarily

on these institutions, which are located throughout the South, as

sources of executive personnel (Id.).

The court below found no evidence of any affirmative program

of recruitment, other than that summarized immediately above. And

indeed, the entire record contains no evidence of any such program,

of whatever sort. Georgia Power's recruitment "policy" consists

of acceptance of the consequences of the situation it occupies as a

major employer throughout Georgia.

23

ARGUMENT

Introduction

The facts in this case show that the date of July 29, 1963

marked merely a transition from an open and declared rule that

blacks were to be confined to menial work without exception, to a

covert policy to permit a few token blacks to rise a notch or two

and employ a few token whites for a while in the lowest positions,

but nevertheless to adhere to the old rules to the greatest ex

tent that the defendants thought they could get away with. The

court below failed to recognize or correct several of the most

egregious practices maintained by Georgia Power pursuant to this

policy. In this argument, we show that the court below erred and

must be reversed with respect to those policies relating to test

ing, job assignment, and employee recruitment. Next, we urge

that the relief accorded by the court below was wholly inadequate,

and that this "relief" itself perpetuates the effects of race dis

crimination. In particular, we argue that the district court's

remedy was legally deficient with respect to the adequacy and

scope of compensatory seniority, and adequacy of back pay awards

to the named plaintiffs, the availability of class-wide back pay, the

applicable statute of limitations, and the adequacy of attorney's fees.

I. GEORGIA POWER COMPANY'S USE OF EMPLOYMENT

TESTS VIOLATES TITLE VII SINCE THOSE TESTS EXCLUDE BLACKS FROM HIRING OR PROMOTION

INTO BETTER JOBS AND SINCE THE TESTS' JOB

RSLATEDNESS HAS NOT BEEN ADEQUATELY

DEMONSTRATED.

In confronting the issue raised by Georgia Power's employ

ment testing program, this Court must reach questions not presented

24

or decided in the landmark case of Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401

U.S. 424 (1971). Nevertheless, we submit, application of the

principles established by Griggs must lead this Court to hold

Georgia Power's tests unlawful under Title VII.

The Griggs decision laid down the courts' basic approach for

Title VII review of employment tests. Under Griggs, the employer's

"good intent or absence of discriminatory intent" is unimportant.

401 U.S. at 432.

Rather, in fhe words of the Supreme Court:

The touchstone is business necessity. If

an employment practice which operates to

exclude Negroes cannot be shown to be

related to job performance, the practice is prohibited.

401 U.S. at 431. And, the Court has made it clear that the employer

has the burden of proof in establishing this business necessity.

Congress has placed on the employer the

burden of showing that any given require

ment must have a manifest relationship

to the employment in question.

401 U.S. at 432. There can be no question that the tests used by

Georgia Power operate to exclude Negroes in the sense referred to23/

in the Griggs case, and the district court so found (Opinion at

30-31). Thus, on this appeal the only issue is whether Georgia

Power has satisfied its burden of proving business necessity

sufficient to justify its use of discriminatory tests.

Realizing its affirmative burden, the Company introduced a

"validity study", conducted by one Dr. Lorain Hite, which the

2 3/ See pp. 16-17 , supra .

25

Company claimed satisfied the requirements of Griggs. The dis

trict court concurred with the Company's position (Opinion at

51-52). This ruling was in error. The Hite study does not prove

business necessity under any reasonable standard, as our analysis

24/

shows. If the courts permit employers to satisfy their burden

of justification with a study such as the Hite document, the rule

of Griggs will be wholly frustrated. Employers will then merely

be required to go through a hollow statistical exercise to pro

duce a few meaningless numbers for cursory judicial inspection.

The Griggs decision means more than this. The courts must es

tablish standards which assure that the employer's proof of test

validity is meaningful. The present case presents this Court

with the task of determining those standards.

A. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures

Define the Appropriate Standards of Test Use.

Since Georgia Power's Testing Practices do

Not Conform to These Standards, They Should Be Declared Unlawful.

Full evaluation of Dr. Hite's validity study and assess

ment of its adequacy is a necessarily technical and difficult

job, because the study itself is highly technical. Although we

present this technical analysis below, we first urge that it was

inappropriate for the district court to attempt its own analysis

24/ Because of its numerous serious deficiencies, the Hite study

proves little or nothing. To the extent it proves anything, it

proves that Georgia Power's use of the tests is wholly unjustified

and irrelevant to job performance. See. pp. 35-44 , infra.

26

of the adequacy of the Company validity study. The degree of

confusion which the district court not surprisingly evidenced

shows why the courts are ill-equipped to undertake such technical

26/analyses. Indeed it is impossible to read the transcript of

the trial below without sympathizing with the district judge as

he struggled with psychological statistics to master the study's

technical details and establish standards for assessing its

2 7/

adequacy.

25/

25/ The district judge himself expressed his dissatisfaction at

being placed in a position which he did not have the technical ex

pertise to fill:...this has happened a lot in this EEOC business, that

everybody passes the buck around at the administrative

level and says we don't know the answer, let it go to

court and let the judge figure it out. We don't have

the expertise to do these things. That's what bothers

me, so now I have had about a seven hour course in

psychological testing and yet I may have to rule its

applicability to 8,000 people. (6 Tr. 142).

As we argue in the text, the court below erred in ignoring the

alternatives to his plight.

26/ The opinion and decree bear witness to the district court’s per plexity. Their remedial provisions are in many ways inexplicable in

terms of the court's findings of fact and what the Hite study showed

Thus, for example, the court permitted continued use of the tests for helper positions even though the court found the tests to be of

no "significant help to the company in predicting job performance

of applicants" for those positions (Opinion at 34). The court also

allowed continued use of the Wonderlic test— which was barred in

Griggs— even though the study did not even include that test and no

other evidence was introduced which would support its use.

27/ See 3 Tr. 20, 23-24, 25, 27-28, 40, 47, 51, 6 6, 70, 73, 139,

142, 144, 147, 184, and 6 Tr. 63, 64, 81, 91, 98, 101, 111, 124-125,

14 2, 143, 144, 157.

Perhaps the most poignant comment by the judge was the

following:

"I might be disqualified in this case. My daughter flunked

statistics in college and I am beginning to see why she did. Would

you all accept my disqualification at this point?" [not accepted]

(6 Tr. 157).

27

It was unnecessary for the district judge to become so en

meshed in the technical details of establishing a standard for

review of validity studies. The Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission (EEOC), the agency charged with enforcement of Title

VII, has published extensive Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures, 2 9 C.F.R. §L607 (1970), in CCH Empl. Prac. Guide f 16,904,

which provide a complete set of standards for reviewing test use.

The court below, however, refused to follow the Guidelines.

It rejected the Guidelines despite their stated purpose of pro

viding

a workable set of standards for employers,

unions, and employment agencies in deter

mining whether their selection procedures

conform with the obligations contained in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (29 C.F.R. §1607.1 (c) ) .

The court also declined to recognize that the Guidelines impose no

extraordinary requirements, but rather permit "any appropriate

validation strategy" in conformity with established professional

standards set forth in the Standards for Educational and Psycho

logical Tests and Manuals of the American Psychological Association

29 C.F.R. §1607.5 (a) - (b) . The court thought that the Guidelines

established an unnecessarily strict standard. Indeed, the district

judge appears to have mistakenly believed that no available test

could meet the EEOC Standard; he noted at one point that

the rather startling evidence offered by the

government was to the effect that there was no

test known to exist or yet devised which could meet such standards.

(Opinion at 33, 51 n.8) This finding was clearly erroneous and

wholly unsupported in the record. The government made no such claim

28

and if it had, the claim would have been false. The EEOC, acting

pursuant to its Guidelines, has frequently approved test use both

28/in published and unpublished decisions.

The district court erred in failing to follow the EEOC Guide

lines. The value of these Guidelines has been emphasized by a

number of courts. They formed the basis of the Griggs decision,

where the Supreme Court said.

Since the Act and its legislative history

support the Commission's construction, this

affords good reason to treat the Guidelines

as expressing the will of Congress.

401 U.S. at 435. This Court has also stressed the Guidelines'

28/ See e.g., unnumbered decision, Dec. 6 , 1966; Decision 71-

1471, March 19, 1971 (CCH Empl. Prac. Guide f6220); Decision 71-

1525, March 26, 1971 (CCH f6224); Decision 71-1418, March 17, 1971

(CCH f6223) ; Decision 70-630, March 17, 1970 (CCH 16136).

The district judge's mistaken belief is evidently the result

of an erroneous inference drawn from testimony of the government's

expert witness, Dr. James J. Kirkpatrick. Dr. Kirkpatrick testified

that a test having a discriminatory impact on blacks would meet Guide

lines standards only if "it was shown that Negroes really were poor on the job to the same degree they were poorer, lower on the tests"(3 Tr. 197) or if an adjustment were made in test scores to eliminate

the discriminatory impact (3 Tr. 196). This colloquy then ensued:

The Court: Do you know of any tests that the

Power Company could come by that would meet

this standard you have set? I don't believe

there is one?

The Witness: I don't think so either; it'sa question that has to be answered by re

search and not by pulling a test off the

shelf or trying it from the publisher's

catalogue (3 Tr. 197-198).

The court may have understood Dr. Kirkpatrick to mean that he knew

of no test which met his standards. But the witness's remark must

be interpreted in context. The same witness testified earlier that

other companies had testing programs which met his standards (3 Tr.

179-181). His later comment thus plainly meant only that no test

which is used by a company without studying its racial impact and

job relatedness meets his standards. That is hardly an extraordinary

thought in light of the Griggs decision.

29

importance in United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Company, F . 2d

___ , 3 EPD 18324 (5th Cir. 1971). In holding that the defendant

employer had not adequately validated these tests, the Court there

observed:

Certainly the safest validation method is that

which conforms with the EEOC Guidelines

'expressing the will of Congress.'

3 EPD 18324 at 6993-149. At least two district courts have re

cognized the reasonableness and persuasive authority of the EEOC

Guidelines and have formally adopted them as the appropriate standard

for validation. In Hicks v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp.. 321 F.Supp.

1241 (E.D. La. 1971), Judge Heebe enjoined the use of any test un

less it had been

validated and proven valid in accordance with

the requirements of the 'Guidelines of Employee

Selection Procedures' published by the United

States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

321 F.Supp. at 1244. The court imposed a similar requirement in its

decree in Carter v. Gallagher, ___ F.Supp. ___ , 3 EPD 18205 at

6682-83 (D- Minn, 1971), aff'd in pertinent part, F.2d , 3 EPD2 9/

18 3 3 5 (8th Cir. 1971) .

2_9/ Other governmental agencies have also approved the Guidelines as standards for employment testing. The Office of Federal Contract

Compliance (OFCC) of the United States Department of Labor - the

agency charged with supervision of the fair employment program for

government contractors emanating from Executive Order 11246 - after

extensive study and consultation with a board of expert advisors including representatives of major businesses, promulgated its order

on employee testing and other selection procedures, which is virtually

identical to the EEOC Guidelines. See 36 Fed. Reg. 19307 (Oct. 2,

1971), in CCH Emp. Guide f 17,589 revising 41 C.F.R. §60-3. The

Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission has also recently published

new testing guidelines which are virtually identical to the EEOC

Guidelines. See Pennsylvania Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures, 1 Pa. Bull. 2005 (Oct. 16, 1971), in CCH Emp. Prac.Guide f5194.

30

The conflict between the adoption of the Guidelines by the

district courts in Hicks and Carter and the rejection of the Guide