Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

July 23, 1972

56 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Furman v. Georgia Hardbacks. Petition for Rehearing, 1972. d6d6ab28-b225-f011-8c4e-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c9ca8ed-e114-4cb4-adb4-9f4bebbdb761/petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

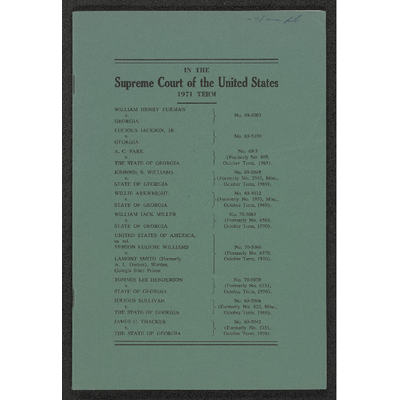

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

1971 TERM

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN

V.

GEORGIA

LUCIOUS JACKSON, JR.

Vv.

GEORGIA

A. C. PARK

V.

THE STATE OF GEORGIA

JOHNNIE B. WILLIAMS

V.

STATE OF GEORGIA

WILLIE ARKWRIGHT,

V.

STATE OF GEORGIA

WILLIAM JACK MILLER

V.

STATE OF GEORGIA

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

ex rel.

VENSON EUGENE WILLIAMS

Vv.

LAMONT SMITH (Formerly

A. L. Dutton), Warden,

Georgia State Prison

TOMMIE LEE HENDERSON

Vv.

STATE OF GEORGIA

JULIOUS SULLIVAN

V.

THE STATE OF GEORGIA

JAMES C. THACKER

V.

THE STATE OF GEORGIA

| No. 69-5003

No. 69-5030

Nec. 69-3

(Formerly No. 809,

October Term, 1969).

No. 69-5049

(Formerly No. 2383, Misc.,

October Term, 1969).

No. 69-5032

(Formerly No. 1953, Misc,

October Term, 1969).

No. 70-5065

(Formerly No. 6569,

October Term, 1970).

No. 70-5066

(Formerly No. 6570,

October Term, 1970).

(Formerly No. 6733,

No. 70-5079

} October Term, 1970).

(Formerly No. 825, Misc.,

! No. 69-5006

October Term, 1969).

(Formerly No. 5331,

No. 69-5045

} October Term, 1970).

GEORGE CUMMINGS

Vv.

STAd’E OF GEORGIA

JAMES C. LEE, alias

MOSES KING, JR.

Vv.

THE STATE OF GEORGIA

JAMES HENRY WALKER

Vv.

THE STATE OF GEORGIA

No. 69-5027

(Formerly No. 683, Misc.,

October Term, 1969).

No. 69-5039

(Formerly No. 5256,

October Term, 1970).

No. 70-3

i (Formerly No. 429,

October Term, 1970).

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

PETITION FOR REHEARING

P. O. Address:

132 State Judicial Bldg.

40 Capitol Square, S.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

P. O. Address:

Chatham County Courthouse

Savannah, Georgia

ARTHUR K. BOLTON

Attorney General

HaroLp N. HiLr, Jr.

Executive Assistant Attorney General

COURTNEY WILDER STANTON

Assistant Attorney Generzl

DoroTHY T. BEASLEY

Assistant Attorney General

ANDREW J. RYAN, JR.

District Attorney

Eastern Judicial Circuit

ANDREW J. Ryan, III

Assistant District Attorney

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. CONTEXT OF THE CASES

II. REASONS FOR GRANTING

REHEARING

A. THE DECISION OVERREACHES THE

SCOPE OF THE QUESTION ..

B. THE FINDING UNDERLYING THE

COURT'S BASES ARE DEVOID OF

COGNIZABLE PROOF

.. THE JURY'S ROLE INTERCEPTS

LEGISLATIVE EXCESSES

. THE END HAS BEEN CONFUSED

WITH THE MEANS AND THE

DECISION IS THUS OVER-

REACHING IN ITS EFFECT

E. THE DECISION IS BASED ON THE

MISAPPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES. ..

CONCLUSION

TABLE OF CASES

Aero Mayflower Transit Co. v. Board of

R.R. Comm'rs.;, 332.1).8. 495 (1947)

Arkwright v. Smith, 224 Ga. 764 (1968)

Arkwright v. State, 223 Ga. 768 (1967)

Arkwright v. State, 226 Ga. 192 (1970)

cert. No. 69-5032, Supreme Court of the

United States

Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority,

297 U.S, 288 (1936)

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968)

Ferguson v. Balkcom, 222 Ga. 676 (1966)

i

TABLE OF CASES (Continued)

Page

Ferguson v. Dutton, United States District Court

Northern District of Georgia, Atlanta Division,

Case No. 11339, habeas corpus denied February

26, 1972, appeal pending, U. S. Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, No. 71-1827... .. 19

Ferguson v. State, 215 Ga. 117 (1959) rev’d.

365 U.S. 57001001)... on ns re 19

Ferguson v. State, 218 Ga. 173 (1962)......%..... 19

Ferguson v. State, 219 Ga. 33 (1963), cert. den.

3S5US. 9. rr. a on 19

Ferguson v. State, 220 Ga. 364 (1964), cert. den.

BLUSHONS, i Bra 19

Henderson v. State, 227 Ga. 68 (1970) Cert. No.

70-5079, Supreme Court of United States. ..... 10

In Re Kemmmnler, 136. U.S, 436. (1890)... ......... 40

Lake Carriers Association v. MacMullan,

TRE 1 ,928.Ct. 1749, 32 |. Ed.2d

SIS en sas 23

Massey v. Smith, 224 Ga. 721 (1968), cert. den.

AOS US 01) it nse Seas 18

Massey v. State, 220 Ga. 333 (1965).......0....... 18

Massey v. State, 222 Ga. 143 (1966), cert. den.

$3888. 30. En. ae a 18

Massey v. State, appeal pending Supreme Court

of Georgia, Case NO, 27185 civ nin ons ines 18

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964)... ..31, 32

Miller v. State, 224 Ga. 627 (1968)... .......... 6

Miller v. State, 226 Ga. 730 (1970) Cert. No.

70-5065, Supreme Court of the United States... 6

il

TABLE OF CASES (Continued)

Page

Park v. State, 224 Ga. 467 (1968), cert. den.

Park v: Georgia, 395 11.8. 930°(196%Y. 7... .... 4

Park v. State, 225°Ga. 618 (1969), Cert: No.

69-3, Supreme Court of the United States. ..... 4

Peters v. Kiff, U.S. (1972) [slip opinion

Pp. 10, Na. 71-5078, June 22, 197 =~ AY. con 26

Reetz y. Bozanich;, 397 U.S. 32 (1970) ..... cvs ee 14

Reidy, Covert, 334 US. 11957). ............... 11

Salsburg v. Maryland, 346 U.S. 545 (1954) ...... 30

Weems v. United States,

7 US. Modo) >... .. i... 22, 29, 38, 31

Wilkerson v. Utals, 9S U.S. 130 (1870). .......... 34

Williams v. Illinois, 399 U.S. 235 (1970)... ....;... 26

Willioms v. New York, 3372 U.S. 241 (1949). ...... 26

Williams (Johnnie) v. Smith, 224 Ga. 800 (1968)... 6

Williams (Johnnie) v. State, 223 Ga. 773 (1967)... 6

Williams (Johnnie) v. State, 226 Ga. 140 (1970),

Cert. No. 69-5049, Supreme Court of the

Unifed States... ... 70 il riers 6

Williams (Venson) v. Dutton, 431 F.2d 70

{5th Cir. 1970), Cert. No. 70-5060,

Supreme Court of the United States........... 8

Williams (Venson) v. Dutton, 400 F.2d 797

(3th Cir. 1963), cert. den. 393 U.S. 1103 (1969)... 3

Williams (Venson) v. State, 222 Ga. 208 (1966),

cert, den. 335 U.S. 837(1966). . ....... cone.

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968). ..6, 19, 27

iil

OTHER

Page

Criminal Code of Georgia 326-1601 ....... .0.. . «i... 34

Ga. Laws 1970, pp. 949, 950, as amended 1971,

P- 902 (Ga. Code Ann. 827-2530)... ..... os. 25

Quarles, An Introduction to Georgia’s Criminal

Code, 5 Ga. St. Bar J. 18351968)... .+.... -. i... 12

1v

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

1971 TERM

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN, i

Petitioner,

Vv. s No. 69-5003

GEORGIA,

Respondent. |

LUCIOUS JACKSON, JR., i

Petitioner,

Y. > No. 69-5030

GEORGIA,

Respondent. |

A. C. PARK, D No. 69-3

Petitioner, (Formerly

Vv. 7 No. 809,

THE STATE OF GEORGIA, October Term,

Respondent. | 1969).

JOHNNIE B. WILLIAMS, 1 No. 69-5049

Petitioner, (Formerly)

Vv. . No. 2333,

Misc.,

STATE OF GEORGIA, October Term,

Respondent. | 1969).

WILLIE ARKWRIGHT,

Petitioner,

V.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

WILLIAM JACK MILLER,

Petitioner,

Vv

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

i

J

J

w

r

\.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, )

ex rel.

VENSON EUGENE WILLIAMS,

Petitioner,

V.

LAMONT SMITH (Formerly

A. L. Dutton), Warden,

Georgia State Prison,

Respondent.

TOMMIE LEE HENDERSON,

Petitioner,

V

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

JULIOUS SULLIVAN,

Petitioner,

VY.

THE STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

7)

\_

a

\-

\

~

\

No. 69-5032

(Formerly

No. 19353,

Misc.,

October Term,

1969).

No. 70-5065

(Formerly

No. 6569,

October Term,

1970).

No. 70-5066

(Formerly

No. 6570,

October Term,

1970).

No. 70-5079

(Formerly

No. 6733,

October Term,

1970).

No. 69-5006

(Formerly

No. 825,

Misc.

October Term,

1969).

JAMES C. THACKER, Y\ No. 69-5045

Petitioner, (Formerly

Y, = OND. 3331,

THE STATE OF GEORGIA, October Term,

Respondent. | 1970).

GEORGE CUMMINGS, 1 No. 69-5027

Petitioner, (Formerly

v No. 683, ; > :

Misc.,

STATE OF GEORGIA, October Term,

Respondent. 1969).

JAMES C. LEE, alias

MOSES KING, JR., Re

Petitioner, (Formerly

Y No. 35256

THE STATE OF GEORGIA, October. Term,

1970).

Respondent. |

JAMES HENRY WALKER, ) No. 70-3

Petitioner, (Formerly

Vv. > No. 429,

THE STATE OF GEORGIA, October Term,

Respondent. 1970).

PETITION FOR REHEARING

Comes now the State of Georgia, Respondent herein,

and petitions this Honorable Court for a rehearing in

those cases above-styled which were heard and for a

hearing in those cases which were reversed and re-

manded without a hearing. The reasons therefor are

given below.

4

I. CONTEXT OF THE CASES

William Henry Furman was convicted of murder by

a jury in Savannah, Georgia, in September, 1968. He

admitted on the stand his shooting of the householder

during the course of his attempt to burglarize the home

where the young family was sleeping. The twelve-man

jury of his peers unanimously determined that his sen-

tence should be death.

Lucious Jackson, Jr. was convicted of forcible rape

by a jury in Savannah, Georgia, in December 1968. He

offered no defense to the evidence that he broke into

the home of a young mother early one morning, hid in

a closet with a weapon made by dismantling her scis-

sors, and attacked and raped her after beating down her

desperate struggles and demonstrably threatening her

life. The twelve-man jury determined that the sentence

for the crime established should be death.

A. C. (Cliff) Park has twice been convicted and sen-

tenced to death by juries in Jackson County, Georgia. See

Park v. State, 224 Ga. 467 (1968), cert. den. Park v.

Georgia, 393 U.S. 980 (1968); Park v. State, 225 Ga.

618 (1969), cert. No. 69-3, Supreme Court of the Unit-

ed States. Park was a purported millionaire and was en-

gaged in a large scale illegal traffic in beer, wine, and

whiskey. The local solicitor general, chief prosecuting offi-

cer of the judicial circuit in which Park resided, who had

begun an investigation into Park’s operations, was blown

up when dynamite attached to his car exploded upon

his starting the ignition. Park was convicted of murder.

Johnnie B. Williams and Willie Arkwright were joint-

ly indicted but tried separately for rape in Screven Coun-

ty, Georgia. The reported account tells the story:

5

“[ Arkwright] and Williams went to the home of

the victim, which was in the country with no other

home nearby, entered the home, robbed her of the

money she had, then choked her, threatened to

kill her, and dragged her into the woods, where she

was held by Williams while, according to [Ark-

wright], he attempted to have sexual relations with

her but was unable to do so. The victim testified

that [ Arkwright] did accomplish his purpose, that

he then held her while Williams raped her, and

then [ Arkwright] again raped her. The doctor who

examined her shortly afterwards at the hospital,

where she was brought by a neighbor, testified that

there was male sperm in her vagina and that she was

in a state of shock or hysteria. After raping the vic-

tim, Williams stripped her wedding ring and band

from her finger, and [ Arkwright] and Williams tied

her to a tree and left her in the woods. She released

herself and went looking for her four-year old child,

who was alone at home with her when [ Arkwright]

and Williams had entered the house. She was picked

up on the road by a friend, as was her child, who

had been seen walking down the road. The evidence

shows the cruel, inhumane, wholly unprovoked, das-

tardly crime of rape committed upon this helpless

young woman by [ Arkwright] and his companion.”

Arkwright v. State, 223 Ga. 768, 770 (1967).

® ® *

“The victim testified [in Williams’ trial] that after

Arkwright had demanded her money and had choked

her to the floor twice there in the house, she said to

him, ‘I know you, you’ve been here before and I was

nice to you,” and then he said to [Williams], ‘yes,

she knows me, we've got to bump her off.” Ths wife

of Arkwright testified that she and her husband

stopped at the victim’s house a short time before the

date of the alleged rape and her husband talked with

the victim, who told him that her husband was not

6

at home and her baby was sick and she could not

help him get a tire fixed, which he said was flat.”

Williams v. State, 223 Ga. 773, 774 (1967).

Williams was sentenced to death by two separate

juries, the second following a reversal of sentence based

on Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968). See

Williams v. State, 223 Ga. 773 (1968); Williams v.

Smith, 224 Ga. 800 (1968); Williams v. State, 226 Ga.

140 (1970), cert. No. 69-5049, Supreme Court of the

United States.

Arkwright was also sentenced to death by two sep-

arate juries, the second subsequent to Witherspoon,

supra. See Arkwright v. State, 223 Ga. 768 (1967);

Arkwright v. Smith, 224 Ga. 764 (1968); Arkwright

v. State, 226 Ga. 192 (1970), cert. No. 69-5032, Su-

preme Court of the United States.

William Jack Miller was convicted of rape and sen-

tenced to death in Jones County, Georgia, in February,

1967. His first sentence was set aside due to its failure

to comport with the rule announced in Witherspoon,

supra, and he was sentenced to death again, by a differ-

ent jury. See Miller v. State, 224 Ga, 627 (1968); Mil

ler v. State, 226 Ga. 730 (1970), cert. No. 70-5065,

Supreme Court of the United States. His victim was a

50-year-old woman. The rape was witnessed by her 81-

year-old mother. Miller threatened his victim in her

home with a knife and then both were cut with the knife

before he tore off her clothes, saying, “This is what I

want.” He held the knife during the whole ordeal and

when he left he promised to return and kill his victim

if she rose from the floor within five minutes. He gained

access to her home when, after questioning her out in

7

the yard, he stole into the house before she, being frigh-

i tened, had time to run in and secure the doors.

Venson Williams was convicted and sentenced to

. death in Gwinnett County, Georgia, in October, 1965,

for the murder of a police officer. The stark facts are

summarized as reported:

[3

‘. . . Williams and one Truett owned a garage in

Hartsville, South Carolina, where they were en-

gaged in the business of rebuilding wrecked auto-

mobiles. Early in 1964, they purchased a maroon-

colored 1963 Oldsmobile which had been damaged

on the left side and rear. They concluded that the

car could not be resold at a profit if they had to

purchase the repair parts. Therefore, with the help

of one Evans, they located and stole a substantially

identical Oldsmobile in Atlanta, Georgia. Return-

ing to Hartsville, the three men stopped on a back

road in Gwinnett County in order to put new regis-

tration plates and a new ignition switch on the

stolen car. Responding to a police call reporting

suspicious activity, three Gwinnett County police

officers accosted the car thieves. While being ques-

tioned by the officers, Evans grabbed the gun from

one of the officers, the other two were then dis-

armed, and all three of them were bound together

with their own handcuffs. Williams and Evans then

took the officers into a little wooded area off the

road and shot each officer a number of times, mostly

in the back of the head. The stolen Oldsmobile was

driven off the road and set afire and the three car-

- thieves-turned-murderers slinked away in the night,

leaving the lifeless bodies and the burning car.

Although Williams, Evans, and Truett had been

prime suspects very early in the investigation, more

than a year went by before charges were filed against

them. The difficulty encountered by the investigating

officers was in discovering more than circumstantial

8

evidence connecting the suspects with the crime. The

breakthrough came when Truett, on a promise of

immunity from prosecution, agreed to confess par-

ticipation in the crime and to testify on behalf of

the prosecution.” Williams v. Dutton, 400 F.2d

797,799 (5th Cir, 1963),

The history of his case is reported at: Williams v. State,

222 Ga. 208 (1966), cert. den. 385 U.S. 887 (1966);

Williams v. Dutton, 400 F.2d 797 (5th Cir. 1958), cert.

den. 393 U.S. 1105 (1969); Williams v. Dutton, 431

F.2d 70 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, No. 70-3066, Supreme

Court of the United States.’

Tommie Lee Henderson was tried in DeKalb County,

Georgia, in 1969 for the crimes of kidnapping and mur-

der. The circumstances, as reported, are as follows:

“The kidnap victim, a young girl, seventeen years

of age, a high school senior, was employed on a

part-time basis at the Southern Bell Telephone Ex-

change located on East Lake Drive, Decatur, De-

Kalb County, Georgia. On August 18, 1969, at

approximately 3:15, she drove her red Volkswagen

automobile into the parking lot adjacent to the said

telephone exchange and was preparing to alight

therefrom to go to work when she was approached

by two Negro men, one of whom, [Henderson],

placed a knife against her stomach and ordered her

to “slide over,” telling her that if she would keep

her mouth shut she wouldn’t get hurt. The two men

entered her car and [Henderson] drove the auto-

mobile from the aforesaid parking lot while the

Williams’ death sentence has previously been set aside below due

to Witherspoon, Willicms v. Dutton, 400 F.2d 797. (5th Cir.

1968). Thus he is still subject to a sentencing-only trial. Does

the Court’s action in his case, together with the broad-scoped

underlying decision, foreclose consideration of the death penalty

in Williams’ future trial?

9

other, identified as Benjamin Franklin Edwards,

rode in the back seat with the girl in the front. At

one point, the automobile was stopped and the girl

was forced to get into the back seat. She was driven

to a secluded spot located in DeKalb County where

she was forced to disrobe and forceably raped by

Benjamin Franklin Edwards. She was then per-

mitted to put her clothes back on and taken by the

two men to another spot in DeKalb County after

making several intermediate stops where she was

again raped by Edwards and forced by him to sub-

mit to an unnatural sex act. Following that, the

accused and Edwards resumed a previous argu-

ment in which they had been engaged which was

culminated by the accused stabbing Edwards twice

in the abdomen with a pocket knife. Edwards stag-

gered from the immediate scene and his body was

later found by police officers a short distance there-

from. Thereafter, the kidnap victim, who was, of

course, the chief witness for the State, was taken

by the defendant under continuous threat in the

form of a constantly exhibited knife to different

places in DeKalb and Rockdale Counties. She was

taken to the residence of people known to [Hender-

son| where she was compelled to spend the night

under the explanation by [Henderson] to them that

she and [he] were husband and wife. That resi-

dence was located in Rockdale County, and while

there [Henderson] forced her to submit to sexual

relations on at least three separate occasions, all

the while constantly holding a knife on her and

threatening to kill her if she made an outcry or

complaint. The next morning, she was carried to a

number of other places located in Rockdale Coun-

ty, still under the same threat. returned to the same

house where she had spent the night, and there held

until she was finally rescued by the Sheriff of Rock-

dale County bursting into the house as [Henderson]

exited from the rear thereof and fled the scene. The

10

testimony of a man who observed a struggle be-

tween the girl and Edwards in the rear seat of her

car as it was being driven along an expressway,

followed the car, noted its tag number and reported

what he had seen to the police, of police officers,

the sheriff and of medical witnesses was introduced

by the State in corroboration of the testimony of

the principal witness. [Henderson] testified under

oath, his defense being in substance that it was

Edwards who perpetrated the kidnapping, if there

was a kidnapping at all, that he did not know that

Edwards and the girl were not friends, and that he

thought that the girl voluntarily and willingly ac-

companied Edwards. [Henderson] denied that he

had sexual relations with the girl at any time, or

that he ever exercised any force or made any threats

to compel her to accompany him or Edwards. The

jury found [Henderson] guilty. . . . The court

passed a sentence of death by electrocution as to

each of [the] counts... .”

Henderson v. State, 227 Ga. 63, 71-72 (1970), cert.

No. 70-5079, Supreme Court of the United States.

(In the interest of what brevity may be achieved in

this lengthy Petition, the remaining five cases are not

here summarized).

The Court granted certiorari in Furman and Jackson

and fashioned a common question for consideration in

the two cases:

“Does the imposition and carrying out of the death

penalty in this case constitute cruel and unusual

punishment in violation of the Eighth and Four-

teenth Amendments?”

The Court has declared these two sentences, and those

in the eleven unbriefed and unargued cases, invalid be-

cause studies and statements, those advanced by Petition-

3

ers in argument and those unearthed by the Court sua

sponte and both considered for the first time in this re-

view, are said to demonstrate that the death penalty is

“unevenly” imposed by judges and juries in this country

and is so “infrequently” imposed that it must be imposed

for the wrong reasons so that its impositions constitute

prohibited cruel and unusual punishment. Little attention

has been paid to the cases before the Court, or to whether

the juries in these cases acted arbitrarily, or to whether

the penalties in these cases were excessive, or even, for

that matter, to whether the death penalty is being applied

constitutionally now or is even capable of constitutional

application in Georgia presently or in the future.

In reaching its ultimate conclusion, the Court has un-

necessarily mortgaged the future by its broad pronounce-

ment. See Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1, 67 (1957), con-

curring opinion of Mr. Justice Harlan.

II. REASONS FOR GRANTING REHEARING.

A. THE DECISION OVERREACHES THE SCOPE

OF THE QUESTION.

The constitutional question framed by the Court is

limited to these cases and therefore necessarily to the

circumstances and statutes involved in them. This is a

fundamental parameter of judicial review, which is con-

fined to particular and concrete cases or controversies.

The Court has here set aside its own rules in dealing

with constitutional questions. Although Mr. Justice

Stewart calls attention to the rule that the Court will

not “formulate a rule of constitutional law further than

is required by the precise facts to which it is to be ap-

plied,” the Court does not in fact limit consideration

12

to the murder and rape penalty statutes of Georgia nor

more narrowly to their application in the circumstances

of Furman and Jackson. The sentences in these cases are

instead viewed in the context of the whole nation’s “legal

system” (Stewart, J., slip opinion, p. 4). The context is

exploded to country-wide proportions and the objections

to the sentences imposed in these cases are based on sta-

tistics and studies and statements drawn nationally. The

opinions are replete with matter outside the facts of

“these cases,” and there is no apparent justification for

the necessity of such a sweeping rule in the decision of

these cases.

The yardstick for determining whether the sentences

are excessive is what “the state legislatures” have enacted

(Stewart, J., slip opinion, p. 4). If the examination had

been confined to the context of these cases, the Court

would have to consider whether the Georgia legislature

deemed the death penalty necessary, assuming this to

be a proper inquiry in determining the constitutionality

of a state penalty, and the opinions are devoid of inquiry

into the rationale which prompted the Georgia Assembly

to authorize the imposition of the death penalty in 1968.

Such a consideration would require remand for further

factual development. The invidiousness of abandoning

the proper context is heightened by the fact that Geor-

gia legislative study committees substantially studied the

question of retention of the death penalty prior to its

inclusion in the new Criminal Code of Georgia, which

became effective July 1, 1969. The Court fails to take

2See references to the House and Senate Reports in Respondent’s

Brief in Furman v. Georgia, at pp. 58-59. See also Quarles, An

Introduction to Georgia's Criminal Code, 5 Ga. St. Bar J. 185

(1968).

13

into account that the decision in these pre-1969 cases

steps over the results of interim legislative action. The

Court rules in effect that the legislative action was not

justified but it has omitted looking into the justifications.

The consideration given reached far beyond the ques-

tion before the Court. Even if it had found that Furman

and Jackson were the victims of capricious punishment

determination and wanton jury action, the same infirmity

does not logically extend to A. C. Park, Johnnie B. Wil-

liams, William Jack Miller, Willie Arkwright, Venson

Eugene Williams, Tommie Lee Henderson, or others so

sentenced simply because they, too, received the death

penalty from Georgia juries.

The question was not whether the death penalty in

America constituted cruel and unusual punishment.

Other states had no notice that their own statutes were

being challenged in these specific cases, nor had they

any real opportunity to present evidence and argument

on the validity of their statutes and the death penalties

imposed pursuant thereto. And yet the decision in these

cases apparently overruled all existing non-mandatory

death penalty statutes and all extant sentences. This is

even more extraordinary in that the factual basis for

reaching the conclusion was not evidence but was in-

stead selected studies, statistics, lay opinions, and other

“evidence” which did not meet the most elementary rules

of admissibility. The basis for the opinions is clearly

broader than the context of the question posed, and

broader than the three cases before the Court in which

it considered argument and ruled.

Other traditional rules of judicial restraint have also

seemingly been discarded. The following rules listed by

14

Mr. Justice Brandeis in his concurring opinion in Ash-

wander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U.S. 288,

341-348 (1936), call for reconsideration in the proper

context, the Court having departed to the farthest reaches

from its own concept of appropriate judicial review:

“2. The Court will not ‘anticipate a question of

constitutional law in advance of the necessity of

deciding it.’ . . . ‘it is not the habit of the Court to

decide questions of a constitutional nature unless

it is absolutely necessary to a decision of the case.” ”

Id. at 347.

If the Court has determined, as it apparently has, that

the application of the Georgia statutes was unconstitu-

tional, then for what reasons were the statutes struck

down, and further, for what reason were all death penalty

statutes in the country on both the federal and state

levels, stricken?

“7. ‘When the validity of an act of the Congress

is drawn in question, and even if a serious doubt

of constitutionality is raised, it is a cardinal prin-

ciple that this Court will first ascertain whether a

construction of the statutes is fairly possible by

which the question may be avoided.” ” Id. at 348.

This applies also to state statutes. See, e.g., Reetz v.

Bozanich, 397 U.S. 82 (1970) .Noneof reasons given by

the majority writers preclude constitutional application

and foreclose the operation of discretionary death penalty

statutes that can pass constitutional muster. If the ob-

jections were eliminated, the Court’s bases for finding

the statutes unconstitutional would be abrogated. But

15

Georgia, as well as every other state, is deprived by the

decision of the opportunity to correct its application of

the statutes in those cases where the objections are ger-

mane and to defend those cases where the objections are

without merit.

Even if the three petitioners are the victims of an

unconstitutional procedure for determining sentence

(and it is this process rather than the penalty itself which

the Court objects to), so that their sentences should be

set aside for lack of due process or want of equal pro-

tection, it strains ordinary logic to comprehend what

poison it is, found in their cases, which fatally affects

every other death sentence now in existence in the United

States and which might hereafter be imposed.

The decision apparently strikes down death penalty

statutes for other crimes in Georgia as well as death-

penalty statutes throughout the country. Since no evi-

dence of infection in the application of the Georgia

statutes to the instant Petitioners was found necessary,

an inquiry into other states’ statutes and their applica-

tion would be superfluous. However, this overlooks the

right of Georgia, as well as other states which were not

even represented in these cases, to defend the applica-

tion of their statutes by proof.

The question considered by the majority was sought

to be raised by Petitioners but was rejected by the Court

in its framing of the query in the grant of certiorari. The

stract question and implicitly import into its domain every

stract question and implicitly import into its domain every

other death penalty case and statute. Rather, it focuses

on concrete controversies with respect to discretionary

penalties. The expansion of the question is like taxation

16

without representation. The result is a decision which

affects all fifty states and the Federal Government with-

out giving them a hearing. It transcends the scope of

the cases and lays aside, as well, the traditional restraints

on deciding constitutional questions. Such a free-wheel-

ing approach has led to a multiplicity of conflicts and

confusing advisory opinions. Its vice is even more acute

because it is heterogeneous although its cursory import

is to reverse only the sentences of death in three cases.

These cases ought thus to be reheard in their proper

context and limited to the Court-fashioned question and

the rules of judicial review, and if necessary, remanded

for factual development.

The context of the cases has been overlooked in yet

another area. Petitioners challenge their sentences, not

the statutes on which they were based. Mr. Justice White,

for one, overlooks the distinction between the applica-

tion of the statute in the cases sub judice on the one

hand and the facial constitutionality of the sentencing

statutes on the other hand. He does not consider the

question of unconstitutional application, and yet that

was the question before the Court. The focus is solely

on the facial constitutionality of the statutes authorizing

the death penalty. However, the certiorari-charted course

was necessarily abandoned because facial unconstitu-

tionality is reached only by adverting to the utilization

of the statute. That is, the opinion depends upon a find-

ing of infrequency of application.

B. THE FINDING UNDERLYING THE COURT’S

BASES ARE DEVOID OF COGNIZABLE JUDI-

CIAL PROOF.

The majority has devised various tests and standards

17

by which the sentences in these cases are to be measured

against the Eighth Amendment. In applying these tests

and standards, the Court goes completely outside of the

record and beyond the scope of the cases for “proof”

upon which to base the findings. It consists of data from

other jurisdictions having other laws, studies from other

times having other impediments which contributed to

infrequency and perhaps arbitrariness. There is no proof

based on Georgia's experience.

In concluding that the three death sentences are un-

constitutionally “unusual,” for example, Mr. Justice

Stewart’s factual base is the number of persons reported

to have been received in the prisons of the United States

from 1961 to 1970, according to the National Prisoner

Statistics; this does not reflect the number of persons on

whom the penalty was imposed. Reliance is given to the

estimate that fifteen percent to twenty percent of those

convicted of murder are sentenced to death in states

where authorized.? Florida's, Virginia’s, New Jersey’s,

and national statistics are also depended on.

On the other hand, the frequency of the imposition

of the death penalty in Georgia as a sentence, whether

set aside, commuted or otherwise not carried out for

various reasons, is not taken into account and in fact

would require additional evidence and compilation of

records. However, it is obvious that such factors are in-

dispensible in a consideration of whether Furman’s pen-

altv was “infrequently imposed” in Georgia during the

period in which he was sentenced, and that Jackson's

penalty was an “extraordinarily rare imposition.”

3Is this such an infrequent incidence that it is unconstitutionally

“unusual”?

18

Mr. Justice Stewart’s third reason is that Petitioners

were part of a capriciously selected random handful. The

base number is apparently drawn from the whole coun-

try, for he refers to “all the people convicted” and to a

former United States Attorney General’s nation-encom-

passing statement to a congressional subcommittee. The

conclusion is devoid of any inquiry into the statistics

for Respondent, or to the reasons upon which the juries

here made the somber election of death. The attack of

capricious selection and wanton imposition is mounted

upon the juries’ motives in these cases and assumes with-

out evidence and without even focusing upon the juries

at all, that they acted recklessly and upon mere whim.

The conclusion does not rise to permit a judicial find-

ing of illegality, particularly in view of the admission

that the basis for the juries’ selection has not been dis-

cerned. :

Further, blanket “capriciousness” is reached without

a consideration of other Georgia cases. A. C. Park’s

lurid story, for example, briefly described above, supra,

p. 4, is not separately examined in this regard. Nor

are the juries’ sentences in the illustrative cases of De-

Wayne Massey and Billy Homer Ferguson. Massey has

been sentenced to death three times in consecutive trials

beginning in 1965; he, a white man, committed rape.

Billy Homer Ferguson, a white man, was sentenced to

death by three separate juries in three separate trials in

4The history of the case may be followed in the reports: Massey

v.. State: 220 Gna. : 883 (1963); Massey v, Staite, 222 Ga. 143

(1966), cert. den. . 385 U.S. 36; Massey v. Smith, 224 Ga. 721

(1968), cert. den. 395 U.S. 912. His third sentence is currently

being challenged on direct appeal to the Supreme Court of Georgia,

Case No. 27185, argument heard May 8, 1972, Massey is listed in

Respondent’s Brief in Furman v. Georgia, No. 69-5003, page 3c.

19

1958, 1961 and 1962. He would not even be counted

among the “handful” because his sentence was changed

to life imprisonment due to a Witherspoon v. Illinois im-

pediment in the selection of the third jury. And yet his

three death sentences would be germane to a study of

whether juries imposed it wantonly.

The factual base which forms the foundation of Mr.

Justice White’s primary objection of “infrequent imposi-

tion” is likewise not taken from any study of Georgia

crimes and sentencing during the period surrounding the

1968 convictions in these cases, but rather draws instead

on personal notions of its effectiveness in serving any

punishment purpose and upon personal exposure to a

random parade of cases coming before him, not from

Georgia, but from all over the country.

The conclusion is that the administration of the stat-

ues is “now” unconstitutional. But when is “now?” If

it is taken to mean 1968 to present, then where is the

evidence of the number, percentage, degree of serious-

ness, or reason for jury imposition (if jury motive is

relevant as it appears to be from Mr. Justice Stewart’s

objection of caprice)? Only the trial records were before

the Court to demonstrate how the statutes are now being

administered. To reach the conclusion that rare invoca-

The history of the case is traced in the reports: Ferguson v.

State, 215: Ga. 117 (1959), reversed, 365 U.S. 570 (1961):

Ferguson v. State, 218 Ga. 173 (1962); Ferguson v. State, 219

Ga. 33 (1963), cert. den., 375 U.S. 913; Ferguson v. State, 220

Ga. 364 (1964), cert. den., 381 U.S. 905; Ferguson v. Balkcom,

222 Ga. 676 (1966); Ferguson v. Dutton, United States District

Court for the Northern District of Georgia, Atlanta Division,

Case No. 11,339, habeas corpus denied February 26, 1972,

appeal pending, United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit, No. 71-1827.

20

tion renders the penalty cruel and unusual punishment

should require at least a factual underpinning which can

only be provided in an evidentiary hearing.

Although these cases are seen as “no different in kind

from many others” involving a conflict between judicial

and legislative judgment as to what the Constitution

means or requires, the cases are treated differently in

that, although confined to Georgia and Texas statutes

and their utilization in three cases, the conclusions are

based on “evidence” composed of studies and reports

and statements concerning not solely those states, but

rather previous periods of history as well as the in-

exact evidence of “common sense and experience’ and

a decade of exposure to capital felony cases.

This puts in bold relief the magnified parameters of

the Court’s inquiry. Although nodding reference is made

to the question of sentences in these three cases and to

the conclusion that “what was done in these cases vio-

lated the Eighth Amendment,”® the context is departed

from and the Court wanders far afield in gathering the

“evidence.” Not only is the “evidence” an overextension

of the judicial notice rule, it is ofttimes irrelevant to the

context of the cases, in terms of time and place. What

is completely missing is any real evidence at all, and

more, any real and pertinent evidence of the situation

in Georgia currently. There is no evidence of what the

degree of infrequency is in Georgia, and there is no

evidence that whatever the degree, the purposes of pun-

ishment acceptable to the Court are not “measurably”

accomplished.

White, J., slip opinion, p. 5.

"White, J., slip opinion, p. 3.

8White, J., slip opinion, p. 5.

21

The Court has traditionally required a substantial

degree of evidence of discrimination before it strikes

down a statute because it operates discriminatorily. It

is said that the discretionary death penalty statutes for

murder and rape in Georgia are applied unequally to

the black and the poor and that therefore the State is

prohibited from allowing a discretionary death penalty.

The evidence upon which a finding of discrimation rests

for Mr. Justice Douglas again does not include any study

of Georgia’s experience at all. Instead, it consists in stud-

ies and statements made prior to 1968 and not even of

Georgia: a pre-1962 study in Pennsylvania which in-

cluded only people on death row and went back as far as

1914; a Texas study that went back as far as 1924; a

warden’s statement from 1928; a former United States

Attorney General’s statement (Douglas, J., slip opinion,

pp. 10-12). Mr. Justice Marshall admits that it is a

judicial assemblage of information which, forms the basis

for the decision, rather than any evidence on the record.

He says: “The amount of information which we have

assembled and sorted is enormous” (Marshall, J. slip

opinion, pp. 57-58). Whether the death penalty was

arbitrarily imposed on Furman and Jackson in Georgia

in 1968, and whether the death penalty is arbitrarily im-

posed in 1972, is not known and is not taken into ac-

count, and herein lies the bed of sand.

If the test for Eighth Amendment “unusualness” in

punishment is to embrace non-discriminatory application,

then the cases should be remanded for a development of

those facts, and the penalty should be viable so long as it

is devoid of arbitrary application.

The decision composes no more than an unproved

accusation. The discretionary death penalty per se was

22

not before the Court in these cases, and the effect of

the decision is to circumvent the context as well as the

record in the absence of a full development of facts with

respect to the factors found pertinent by the Court.

It cannot be overlooked that the process has been

vastly changed in the last decade so that the possibilities

of discrimination in sentencing are materially reduced,

and so that current studies need to be made in order to

make stick the indictment which this decision finds

against the penalty. Substantial revisions of the jury se-

lection methods, the development of public defender sys-

tems, the provision for appointed attorneys at earlier

and earlier stages of the proceedings, the elimination of

the scrupled juror infection, and the advent of bifurcated

trial all serve to illustrate that the obstacles envisioned

by the Court are not necessarily insurmountable and

what is more, that they may have been surmounted al-

ready. The effect of these palpable and relevant innova-

tions must be given due weight in a current examination

of facts before the penalty is removed as an option for jur-

ies in murder and rape cases now and in the future.

What was said in Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349

(1910), is applicable here: “Time works changes, brings

into existence new conditions and purposes.” Id. at 373.

The new conditions affecting the sentencing process

should not be overlooked.

The importance of the absence of relevant factual in-

formation is highlighted by Mr. Justice Marshall’s recog-

nition that facts must be considered:

“All relevant material must be marshalled and

sorted and forthrightly examined. We must . . . be

. . . exacting in examining the relevant mate-

rial. . . .” (Marshall, J., slip opinion, p. 3).

23

Even the finding of moral unacceptability of the penalty

to the people of the United States is found not on the

basis of fact, but on the substitution of the Court’s judg-

ment for that of the citizenry. (Marshall, J., slip opin-

ion, p. 51). Is it appropriate judicial policy to substitute

the opinion of the Court for the opinion of citizens or for

the Court to surmise and then act on what it believes the

people would conclude if they were asked? Such conject-

ure finds no place in the application of constitutional

principles here any more than it would were the Court

faced with a state statute not yet construed by the state

courts and open to various interpretation. See Lake Cai-

riers’ Association v. MacMullan, 11.8. ol. ,:92.8.C¢,

1749, 32 1.. Ed. 237 (1972). The hypothetical conclu-

sion is not enhanced by pointing to unproved and gen-

eralized accusations which would “convince” the people

if they were to consider them.

The decision does not square with some fundamental

principles of judicial review. Even if the Court’s reasons

were ultimately proved right, they are not based on em-

pirical evidence adduced in a judicial proceeding. The

laws of Georgia and the imposition of sentences in

these cases are invalidated without examining Georgia’s

performance. The decision is premature; the business is

unfinished.

C. THE JURY’S ROLE INTERCEPTS LEGISLATIVE

EXCESSES.

The Framers sought to curb the Federal Congress

by inserting the cruel and unusual punishment clause

in the Bill of Rights. It was to “guard against ‘the abuse

of power’ ” by the legislative branch. (Brennan, J., slip

opinion, p. 10). The Supreme Court has in the interim

declared that the States are likewise curbed. The mean-

24

ing should be the same for the States as for the fed-

eral government, i.e. it curbs state legislatures from

enacting cruel and unusual punishment provisions.

The decision with respect to appropriate penalty was

the legislature’s, when the Bill of Rights was written, not

the jury’s. The advent of the practice of jury discretion

in sentencing inserted a new and very direct and im-

mediate safeguard against governmental excesses in crim-

inal punishments.

Since the Framers intended to limit the Congress, and

thereby protect the people from legislatively-imposed

cruel and unusual punishments, the delegation of punish-

ment selection by the legislature back to the people them-

selves, to be exercised by their juries, itself achieved the

protection envisioned by inclusion of the Clause in the

Bill of Rights. In other words, the very action of statu-

torily giving juries discretion removes the categorical

setting of punishment by the legislature and thus sub-

stantially guarantees the inability of the legislature to

abuse its power in this regard.

The interposition of jury discretion injected an element

which changes the complexion which would have existed

if the penalty had been mandatorily set by the legislature.

The jury is not the State. It is a body selected coopera-

tively by the State and the defendant. Thus, to say that

the State arbitrarily subjects a defendant to an unusually

severe punishment in these cases disregards the jury’s

discretion. “Arbitrarily” cannot describe the action of

the State when a jury intervenes and exercises its judg-

ment in choosing one of several alternative punishments.

The jury’s role is even more extended in Georgia cur-

rently because the sentencing phase of the trial separately

follows the finding of guilt and the jury thus becomes

25

more knowledgeable about all that is relevant to setting

an appropriate sentence.’

The infrequency and rarity which is found objection-

able by the Court is not in the legislature’s enactment

(i.e., an “unusual” punishment conjured up by the state

legislature to be imposed for a particular crime), but in

the application by juries representing the people in im-

plementing the law. As said, the jury is a unique micro-

cosm of the people themselves; it is not a governmental

body. So, absent any discrimination, its discretionary

selection of a statutory penalty which would not other-

wise be cruel and unusual punishment (i.e., the penalty

as enacted is per se cruel and unusual punishment, so

the jury could not impose it), should not be subject to

Eighth Amendment consideration because the intent of

the Clause was not to curtail juries acting in their dis-

cretion and performing faithfully to their oaths.

The Court has overlooked the distinction. Considera-

tion is instead directed to the death penalty as a legisla-

tively-proscribed punishment and does not meet the ques-

tion posed by these cases, whether the jury-selected

penalty, a product of the “common-sense judgment of a

jury”,'® derived as appropriate after an exercise of duty-

bound discretion, is cruel and unusual punishment.

In each of these cases, the death penalty was imposed

by a jury fairly drawn from the community. The jurors

were a random selection of those differing attitudes which

exist in different combinations throughout each com-

munity. A particular jury of twelve persons in Savannah

%Ga. Laws 1970, pp. 949, 950, as amended 1971, p. 902 (Ga.

Code Ann. $27-2534).

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 156 (1968).

26

will have represented on it at most only twelve occu-

pations, twelve age levels, twelve educational back-

grounds, twelve family situations, twelve economic cir-

cumstances, etc.’ The jurors do not represent the com-

munity in the sense that they are elected to convey the

community’s collective sentiments and to be its spokes-

men. The jurors instead represent the community in the

sense that they come from it and therefore sit as a parcel

of it, though partitioned from it. They are a representative

group; they do not represent that broader body from

which they come. They bring to the jury room their own

individual views and not the collective view of their

neighbors. The queries are, “Do 1 believe this man is

guilty?” and “What punishment do I believe should be

imposed?” It is not, “What would my neighbors have

me do in this case?”

As a result, it is inevitable that harsher penalties will

be imposed upon some the nature of whose offense is no

worse than that of another who receives a lesser penalty.

This Court has ruled that characteristic of our criminal

justice system acceptable. Williams v. Illinois, 399 U.S.

235, 243 (1970), citing Williams v. New York, 337 U.S.

241, 247 (1949).

Thus, the fact that less atrocious crimes in some in-

stances receive a greater penalty than the most terrible

crimes cannot be a contributing factor in a finding of un-

constitutionality. If it is, the earlier decisions are in error,

and uniformity of punishment is mandated. But automatic

The jury room is imbued with “qualities of human nature and

varieties of human experience, the range of which is unknown and

perhaps unknowable.”Peters v. Kiff, U.S. £1972) "ISUHD

opinion p. 10, No. 71-5078, June 22, 1972].

27

death penalties would remove individuality in sentencing,

which has become a hallmark of modern sentencing pro-

cedures. We are going in circles.

D. THE END HAS BEEN CONFUSED WITH THE

MEANS AND THE DECISION IS THUS OVER-

REACHING IN ITS EFFECTS.

The insertion of jury discretion acts as a safeguard

against legislative imposition of unusual punishment. If

the juries infrequently impose it, it is not constitutionally

“unusual” punishment. If the cause for infrequency is

discriminatory or arbitrary action in some cases, then the

process by which such result is reached is of course wrong

and voidable as a lack of due process or equal protection.

But jury misbehavior in some cases should not invalidate

the penalty itself in all cases and disallow its use here-

after. It confuses constitutional error in the procedure

in particular cases with constitutional error in end result

in all cases. Finding constitutional error in procedure

should not invalidate the result per se for this and every

other case and all time.

If the result of the procedure in sentencing is rational

imposition (not “rational selectivity”, as a given jury

does not select one defendant for a death sentence and

another defendant for life imprisonment), what voids the

sentence? The Court has overlooked the paradox that it

hangs its holding of unconstitutionality on a blanket

finding of discrimination and then restricts the flexibility

which the State should have in implementing procedures

which would avoid discrimination.

In Witherspoon v. Illinois, supra, the procedure re-

sulted in a death-prone jury and therefore the defendant

was entitled to a more impartial jury penalty-wise. The

28

same result should be the parameter of these cases and

any others in which it appears that the procedure resulted

in an arbitrary sentence in a specific case. The core of

the objection is what happens in the jury room, for it is

the arbitrariness of the jury which is found intolerable

here. Given the finding of actual arbitrariness on which

the Court’s decision is based, the sentences which are so

infected should be reset by other juries. This requires a

case-by-case analysis of facts, not an obliteration of the

end result when properly achieved even in the exercise

of discretion.

If it is the possibility of arbitrariness which the Court

here concludes is objectionable, then the procedure by

which juries determine sentence should be revised by

whatever means and methods the State may devise to

avert arbitrary selection of a penalty by a jury. The vice

seems to lie in the discretionary role of juries (see Doug-

las, J., slip opinion, pp. 8-9). Thus, juries might be given

more cautionary instruction, or be required to state the

reasons for their imposition of the death penalty. The

separation of trials into two stages, penalty being ad-

dressed independently of guilt, contributes greatly to

this end. But reaching the same goal by striking the

penalty is not only unwarranted judicially since it is not

the only possible way to avoid discrimination, it foments

chaotic results by calling for the elimination of every

maximum penalty which is not frequently used.

E. THE DECISION IS BASED ON THE MISAPPLI-

CATION OF PRINCIPLES.

(1) Only a “necessary” punishment is constitutional.

Mr. Justice White's analysis means that every statutory-

provided maximum punishment is constitutionally im-

29

permissible if it is imposed infrequently, because the in-

frequency factor is taken to show a lack of necessity.

Mr. Justice Stewart reasons that death is cruel because

it exceeds in kind rather than degree, punishments legis-

latively determined to be necessary. The yardstick is

what state legislatures have spoken. Where a particular

penalty is only a maximum which may be discarded by a

jury in favor of a statutorily provided minimum, then any

maximum must similarly fail in an alternative-sen-

tencing statute. It does not stand to reason that legislative

authorization of lesser penalties, resulting in the maxi-

mum not being mandatory, thereby renders the maximum

“cruel.” (See Stewart, J., citing White, J., slip opinion,

p. 4). Moreover, the rationale results in the subjugation of

sovereign states to each other, in terms of penalty for

criminal offense: each state may not impose a greater

sentence “in kind rather than degree” than its sister

states have determined necessary, i.e., mandatory. It

would then follow that a state could not impose a prison

term where other states impose only a fine.

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910), is relied

upon for this test of necessity, but the Court there did

not couch the question of constitutionality in terms of

whether or not the State could show that the punishment

was necessary. The Court was cognizant of quite a dif-

ferent frame. In speaking of the powers of the legislature

to define crimes and their punishment, it said:

“We concede the power in most of its exercises. We

disclaim the right to assert a judgment against that

of the legislature of the expedience of the laws, or

the right to oppose the judicial power to the legis-

lative power to define crimes and fix their punish-

ment, unless that power encounters in its exercise

30

a constitutional prohibition. In such case not our

discretion but our legal duty, strictly defined and im-

perative in its direction, is invoked. Then the legisla-

tive power is brought to the judgment of a power

superior to it for the instant. And for the proper

exercise of such power, there must be a comprehen-

sion of all that the legislature did or could take into

account,—that is, a consideration of the mischief

and the remedy. However, there is a certain subordi-

nation of the judiciary to the legislature. The func-

tion of the legislature is primary, its exercise forti-

fied by the presumptions of right and legality, and

is not to be interfered with lightly, nor by any judi-

cial conception of its wisdom or propriety. They

have no limitation, we repeat, but constitutional

ones, and what those are the judiciary must judge.

We have expressed these elementary truths to avoid

the misapprehension that we do not recognize to the

fullest the wide range of power that the legislature

possesses to adapt its penal laws to conditions as

they may exist, and punish the crimes of men ac-

cording to their forms and frequency.” Id. at 378-

379.

It is thus clear that a state is not required to show

the “necessity” of a particular punishment in order for

it to be constitutional. This is in conformance with the

principle that one who attacks a state statute has the

burden of proving that it does not serve a legitimate state

purpose.’

The point is not merely one of who has the burden,

but also highlights the higher degree of showing which

124ero Mavflower Tronsit Co. v. Boord of R. R. Comm’rs., 332

U.S. 495, 506 (1947) (burden on challenger is to show statute

had “no reasonable relation” to permissible end). “The presump-

tion of reasonebleness is with the State.” Salsburg v. Maryland,

346 11.5. 545..553 (1954).

31

must be made in order to overturn a legislative enact-

ment. In other words, it is not voidable simply because

it is not shown that it is “necessary” but rather, it is

voidable only if it is shown that it does not serve a valid

purpose. Expediency and wisdom are not relevant to a

consideration of constitutionality. A statutory prohibi-

tion may indeed not be absolutely necessary in the ser-

vice of a legitimate state purpose, but absent any other

impediment its service of that purpose to a recognizable

degree passes constitutional muster.

In Weems, the Court said of the punishment there

being considered:

“It has no fellow in American legislation. Let us

remember that it has come to us from a govern-

ment of a different form and genius from ours.

[Spain] It is cruel in its excess of imprisonment and

that which accompanies and follows imprisonment.

It is unusual in its character. Its punishments come

under the condemnation of the Bill of Rights, both

on account of their degree and kind. And they

would have those bad attributes even if they were

found in a Federal enactment, and not taken from

an alien source.” Id. at 377.

In the instant case, the Court not only failed to take

into consideration a comprehension of all that the Geor-

gia legislature did or could take into account in au-

thorizing the imposition of the death penalty in 1968,

but it went further and extended its ruling to the post-

1969 statute and failed to comprehend all that the leg-

islature did or could have taken into account in its leg-

islative studies prior to the enactment of the new Crim-

inal Code of Georgia.

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964), is cited

32

to illustrate a case in which the statute was declared im-

permissible because based on race. McLaughlin illus-

trates also, however, that the test of necessity of legis-

lation is applied only in the examination of statutes with

a racial classification, and where the equal protection

clause is invoked to challenge it:

“There is involved here an exercise of the state

police power which trenches upon the constitution-

ally protected freedom from invidious official dis-

crimination based on race. Such a law, even though

enacted pursuant to a valid state interest, bears a

heavy burden of justification, as we have said, and

will be upheld only if it is necessary, and not merely

rationally related, to the accomplishment of a per-

missible state policy.” Id. at 196.

Mr. Justice Brennan also gives undue regard to the

test of “necessity.” A part of his test provides for a find-

ing of unconstitutionality if the death penalty “cannot be

shown to serve any penal purpose more effectively than

a significantly less drastic punishment.” This neglects the

principle that legislative expediency and the wisdom of

its actions is not a judicial question. It has not been the

job of the courts to determine which punishment best

meets penal purposes. That is the legislature’s domain,

as is the weighing of alternatives. Such a division should

be adhered to because of the facilities for research and

study and gathering of facts and testimony and the

opinion of experts which the legislature is particularly

equipped to assemble and the courts are not. The ap-

propriate judicial consideration is whether the penalty

authorized by the legislature meets penal purposes, not

whether a different penalty could better meet such pur-

poses without exacting the higher price from the pen-

alized. Absent any other afflictions (such as excessive-

33

ness), the legislatively-authorized penalty should be re-

garded as meeting constitutional muster unless it is shown

that it does not serve a valid penal purpose.

The inappropriateness of the inquiry forced by the

standard of necessity is demonstrated by the suggestion

that specific deterrence does not depend on the death

penalty for achievement but rather that “effective ad-

ministration of the State’s pardon and parole laws can

delay or deny his release from prison, and techniques of

isolation can eliminate or minimize the danger while he

remains confined.” Brennan, J., slip opinion, pp. 44-45).

The alternative suggestions of life sentence without

possibility of parole or life sentence in isolation or with

threat of isolation are matters which must be considered

in the context of practicality and reality, in the first place,

and cannot be said to comport with concepts of human

dignity to such a greater degree, that death is consti-

tutionally disallowed. Aside from whether the death

penalty is “fatally offensive to human dignity” being

basically a value judgment rather than a legal judgment,

which requires great deference to legislative and jury

will, the close association between what is condemned

as being offensive to human dignity (swiftly-executed

death penalty) and the suggested replacement (long-

term prison sentence; life imprisonment with threat of

isolation; life imprisonment with little hope of parole),

is overlooked. Can it be said, judicially, that the death

penalty so offends human dignity that it is constitutionally

prohibited when the far more enduring physical, mental,

and emotional pain inherent in the suggested alterna-

tives constitutes “significantly less drastic punishment”

which does not offend judicial concepts of human dignity?

34

There appears no authority for the proposition that a

penalty must be “necessary” as opposed to a different

penalty, for the protection of society, in order to be

constitutional (Brennan, J., slip opinion, p. 48). If this

were a proper standard, then a State would be put to the

task of proving that any maximum penalty is “neces-

sary”. But how, for example, can it be proved that 20

years is a necessary maximum for burglary,” that it is a

better deterrent than a five-year term, and that it better

serves penal purposes?

As Mr. Justice Marshall pointed out, this Court in

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1870), construed the

Clause to prohibit “unnecessary cruelty”. (Marshall, J.,

slip opinion, pp. 9-10). This does not mean that a pun-

ishment to be constitutional must be more “necessary”

than a lesser punishment. But the penalty is considered

unconstitutional if a less severe penalty would as well

serve the legitimate legislative wants. The question is not

whether less will do, but whether the legislative enact-

ment serves a valid state purpose.

(2) Infrequency of administration renders a penalty

unconstitutionally “unusual”.

Contained in the decision is the proposition that it is

the infrequency of application of the death penalty

which in great part contributes to its unconstitutionality

as a discretionary punishment. Infrequency is equated

with “unusualness”, but what is overlooked is that the

Clause prohibits legislative or judicial pronouncement of

unusual punishments. As pointed out earlier, the intro-

duction of the discretionary jury, long after the enactment

13Criminal Code of Georgia §26-1601.

33

of the Bill of Rights, guards against governmental ex-

cess. The non-governmental jury was not the object of

the Framers’ curtailment, and therefore, the inquiry of

whether it frequently or infrequently imposes a punish-

ment is unrelated to the prohibition against unusual pun-

ishments cor.tained in the Constitution.

Secondly, what the fatal degree of infrequency is, is

subject to conjecture and debate. It is not defined in

any utilizable way what degree of frequency is consti-

tutionally required. If only twenty per cent of those con-

victed of burglary received the maximum punishment,

does this render it unconstitutional as a permissible pun-

ishment per se for burglary? If only twenty per cent of

those convicted for income tax evasion receive a prison

term, whereas the other eighty per cent receive a fine,

is the imprisonment unconstitutionally impermissible?

Apparently, twenty per cent is too infrequent (See Mr.

Justice Burger’s dissent, slip opinion, p. 13, footnote 11).

Even assuming that the degree of unconstitutional in-

frequency is agreed upon, and assuming further that

imposition in Georgia fell below this line, why does

infrequency per se render a particular punishment for-

ever unimposable on a discretionary basis? Since that

degree of frequency may rise, it is over-zealous and un-

necessary to ban the discretionary penalty for all time

and even for those cases of “most atrocious crimes” in

present times “that deserve exactly” the death penalty?

Although it seems to be said that infrequency per se

renders the death penalty unconstitutional, this is con-

tradicted in Mr. Justice White’s conclusion, which states

that infrequency merely creates a prima facie case of

constitutionally forbidden cruel and unusual punishment,

36

which may be rebutted by an explanation distinguishing

the cases on a meaningful basis. No opportunity has

been given to present factually the reasons for the im-

position in certain cases as opposed to others. No com-

parative study of those cases in which it is imposed are

examined along with those cases in which it was not im-

posed in Georgia to see whether it was constitutionally

authorized in the death cases. Infrequency may render

the penalty invalid for lack of equal protection, but this

comparative approach does not logically lead to voidance

of all such penalties now extant or hereafter to be im-

posed.

In addition to the inappropriateness of using infre-

quency as a test in these cases, the conclusions reached

upon a consideration of it are not supported. On the

basis of logic, infrequent imposition does not necessarily

destroy a penalty’s efficacy as a “credible threat.” Ob-

viously, if a particular penalty is never imposed and this

fact becomes common knowledge, then that particular

penalty ceases to be a brake on behavior. But where it

stands not only as a beacon of warning but more, a bea-

con tested by the unheeding whose recently broken craft

is visible to those who would otherwise disregard it, then

it cannot be said that it is not a credible threat. Capital

felons were undeniably being sentenced to death during

Furman’s and Jackson’s day, and continue to receive the

ultimate penalty. Thus, in order for the conclusion to

be reached that the death penalty is no longer a credible

threat in Georgia because of its infrequent application,

consideration of the facts cannot be avoided. In other

words, a broad constitutional line is drawn between pun-

ishments “so seldom” imposed and those not so cate-

gorized, without examining the incidence of infrequency,

37

the reasons therefor, or whether in fact infrequency de-

stroys the credible threat aspect of punishment which is

served at least to some degree by the greater and more

widespread public knowledge which a death case as op-

posed to a prison term case, receives.

To summarize, if infrequency itself renders the pun-

ishment unconstitutional, then the degree of infrequency

must be set and the facts as to Georgia’s utilization of

the penalty must be examined. If, on the other hand,

infrequency constitutes only a prima facie case so that

a rational basis for the degree would outweigh its fatal

effect, then the opportunity for refuting the evidence

of infrequency must be given. In any event, the decision

goes too far on too little. The demise of such a tradi-

tional ingredient in the makeup of our criminal justice

system should not be so easily or fuzzily achieved.

The standard, moreover, falls in on itself. The argu-

ment is that a penalty is cruel and unusual for the per-

son who draws it because others in like circumstances are

given lesser punishments by other juries or judges. But

if the penalty is appropriate in the case where it is im-

posed, what makes it cruel and unusual punishment just

because others have not received it? Does the fact that

few burglars get the maximum of 20 years imprison-

ment render that maximum unconstitutional? It can-

not be that the mere fact of unequal sentencing renders

the maximum unconstitutional, because uniform sen-

tencing is not required by our Constitution. It cannot be

because the sentence was excessive, because as recog-

nized by a great part of the Court, if not the entire Court,

the crimes here involved were atrocious and called for

proportionate punishment.

The Court concludes that the penalty, since not regu-

38

larly given, must therefore be based on discrimination and

arbitrariness and consequently is cruel and unusual pun-

ishment. It is not infrequency per se which renders it

“cruel and unusual”, but rather the poison of discrim-

ination which is presumed to account for the infrequency

which makes the latter a measure of unconstitutionality.

The fallacy is in presuming that discrimination exists

simply because the penalty is infrequently imposed. It

is admittedly only an inference, unsupported by any

finding of current arbitrariness by death-deciding juries,

and yet the whole decision pivots around it. At the least,

this overlooks the presumption that the jury acts fairly

and discharges the duties undertaken in its oath. Dis-

carding the presumption is antithetical to our cornerstone

reliance on the jury system in its present and even more

expansive role under the bifurcated system. Hinging the

decision to overturn discretionary death penalty on an

assumption that juries act capriciously when they impose

it, simply because it is infrequently imposed, is an un-

founded legal conclusion and should be reconsidered all

the more because of the far-reaching effect it has, not

only on the death penalty but also on other discretionary

sentences. The modern role of the jury has itself been

undermined.

Moreover, the conclusion that “infrequent” imposition

of a penalty ceases to serve a legitimate State purpose to

that degree required by the Constitution is devoid of pre-

vailing support in these cases. Neither the incidence of

infrequency in Georgia in present time nor the underlying

reasons for whatever infrequency exists have been exam-

ined. Further, there is no evidence that the factor of in-

frequency per se leaves unaccomplished to a constitution-

ally acceptable degree any of the purposes for imposing

39

penalties for criminal conduct. Mr. Justice White reasons

that a particular punishment must be regularly imposed if

it is to meet the proscription against cruel and unusual

punishment. But this seems to be confused with the con-

cept that statutory prohibition of conduct which is not

prohibited in fact, becomes unenforceable against one vio-

lator. Obviously, a person cannot be punished for doing

something which the rest of the community does without

sanction. But whether that same individual may be

punished more stringently than one who commits the

same crime, fact-for-fact, has been permitted to exist as

a by-product of our system of granting heterogenous and

unrelated juries a wide-degree of discretion in sentencing.

Mr. Justice Brennan’s opinion also exhibits reliance

on this erroneous standard. He challenges that “no one

has yet suggested a rational basis that could differentiate

in those terms the few who die from the many who go