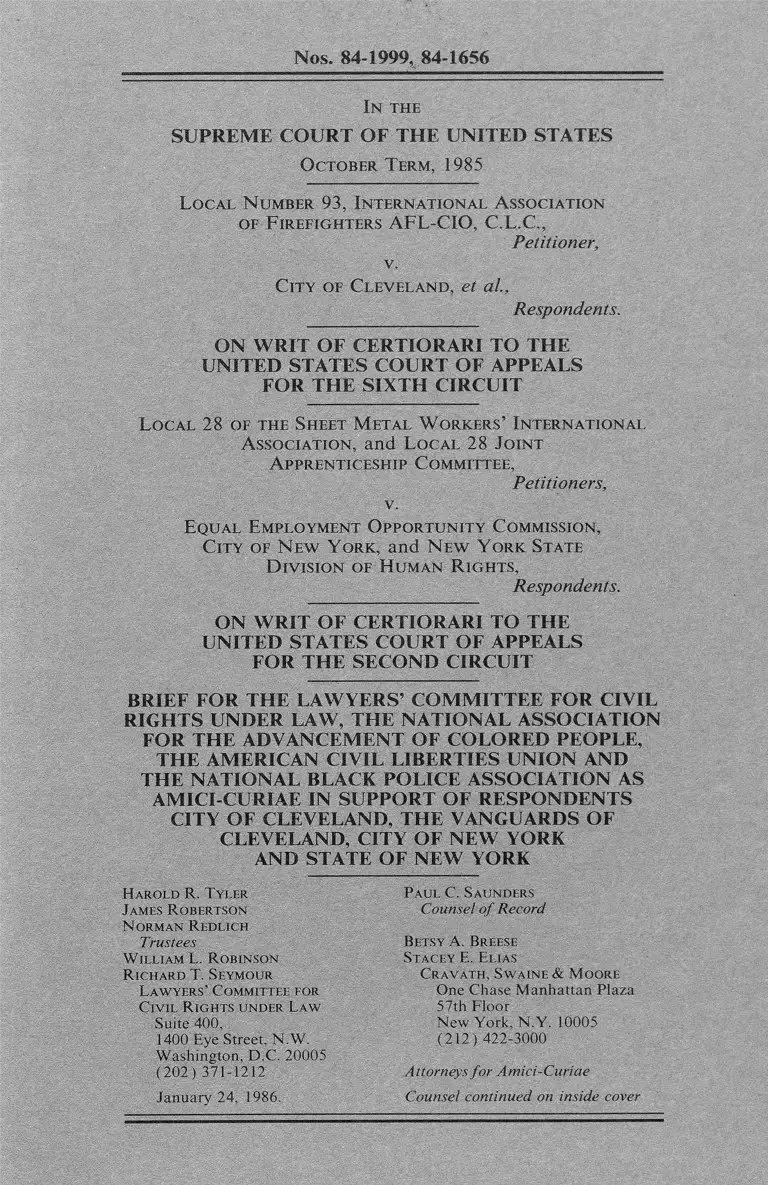

Local Nuber 93, International Association of Firefighters AFL-CIO, C.L.C. v City of Cleveland Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 24, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Local Nuber 93, International Association of Firefighters AFL-CIO, C.L.C. v City of Cleveland Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1986. a9994161-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5ccf5c97-ebd7-477f-ae9d-ea675ac845e8/local-nuber-93-international-association-of-firefighters-afl-cio-clc-v-city-of-cleveland-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 84-1999, 84-1656

In the

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

O ctober T erm, 1985

L ocal N umber 93, International A ssociation

of F irefighters AFL-CIO, C.L.C.,

Petitioner,

v.

C ity of C leveland , et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

L ocal 28 of the Sheet M etal W orkers’ I nternational

A ssociation , and L ocal 28 J oint

A pprenticeship C ommittee,

Petitioners,

v.

E qual E mployment O ppo rtu n ity C ommission,

C ity of N ew Y ork, and N ew Y ork State

D ivision of H uman R ig h ts ,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE,

THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION AND

THE NATIONAL BLACK POLICE ASSOCIATION AS

AMICI-CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

CITY OF CLEVELAND, THE VANGUARDS OF

CLEVELAND, CITY OF NEW YORK

AND STATE OF NEW YORK

H arold R. Tyler

James R obertson

N orman R edlich

Trustees

W illiam L. R obinson

R ichard T. Seymour

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil R ights under Law

Suite 400,

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

January 24, 1986.

P aul C. Saunders

Counsel o f Record

Betsy A. Breese

Stacey E. Elias

Cravath, Swaine & Moore

One Chase Manhattan Plaza

57th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10005

(212) 422-3000

Attorneys for Amici-Curiae

Counsel continued on inside cover

E. R ichard Larson

Burt N euborne

American C ivil L iberties

Union F oundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, N.Y. 10036

(212) 944-9800

G rover G. Hankins

Charles E. Carter

N ational Association for

T he Advancement of

Colored People

186 Remsen Street

Brooklyn, N.Y. 11201

(718) 858-0800

Attorneys for Amici-Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES........................................... iii

CONSENT OF PARTIES................................................ 1

INTEREST OF AMICI.................................................... I

STATEMENT OF THE CASES............................... 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT...................................... 5

ARGUMENT................................................................... 7

I. CLASSWIDE RACE-CONSCIOUS NUMER

ICAL RELIEF IS A PRACTICAL NECES

SITY; IT IS SOMETIMES THE ONLY REM

EDY THAT CAN EFFECTUATE THE CRITI

CAL POLICY UNDERLYING TITLE V II...... 7

A. It Would Be Impossible Effectively To

Enforce Title VII Without Classwide Nu

merical Relief In Appropriate Cases......... 7

B. Victim-Specific Relief Is Often Too Nar

row To Achieve The Goals Of Title VII..... 13

C. Effective Eradication Of Past Dis

crimination Requires Integration In The

Workplace.................................................. 15

II. COURTS ARE INVESTED WITH WIDE DIS

CRETION UNDER SECTION 706(g) TO OR

DER CLASSWIDE RACE-CONSCIOUS NU

MERICAL RELIEF WHERE SUCH RELIEF

IS NECESSARY TO EFFECTUATE THE

PURPOSES OF TITLE VII............ 16

A. Section 706(g) of Title VII Permits

Many Forms of Relief Including Prospec

tive Classwide Affirmative Relief And

Make-Whole Relief As Remedies For

Employment Discrimination...................... 16

B. Congress Intended To Invest District

Courts With Wide Authority To Remedy

Discrimination And Endorsed The Courts’

Use Of Affirmative Classwide Race-

Conscious Numerical Remedies In Appro

priate Cases................................................ 19

Page

11

Page

III. FEDERAL COURTS HAVE AWARDED OR

APPROVED NUMERICAL RELIEF ONLY

AFTER A CAREFUL EXAMINATION OF

THE NEED FOR THE RELIEF AND THE

EFFECT SUCH RELIEF WOULD HAVE ON

NONMINORITIES......................... 25

IV. STOTTS DOES NOT PROHIBIT PROSPEC

TIVE RACE- AND GENDER-CONSCIOUS

RELIEF UNDER TITLE VII............................. 28

CONCLUSION............................................ 29

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

C ases

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975).. 7, 15, 16

Berkman v. City of New York. 536 F. Supp. 177

(E.D.N.Y. 1982), ajf’d, 705 F.2d 584 (2d Cir.

1983).......................................................................... 13,16

Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc. v. Beecher, 504 F.2d

1017 (1st Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 910

( 1975)....... ................................................................ 17

Britton v. South Bend Community’ School Corpo

ration, 775 F.2d 794 ( 7th Cir. 1985)....................... 28

Buckner v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., 339 F.

Supp. 1108 (N.D. Ala. 1972), ajf’d, 476 F.2d 1287

(5th Cir. 1973)......................................................... 24

California Hospital Association v. Henning, 770 F.2d

856 (9th Cir. 1985).................................................. 25

Chisholm v. United States Postal Service, 665 F.2d

482 (4th Cir. 1981).................................................. 16

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Local 542, Oper

ating Engineers, 38 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. ( BNA)

673 (3d Cir. 1985).................................................... 28

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Rizzo, 13 Fair

Empl. Prac. Cas. ( BNA) 1475 ( E.D. Pa. 1975) 13

Contractors Association v. Secretary o f Labor, 442

F.2d 159 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854

(1971)....................................................................... 22

Diaz v. American Telephone & Telegraph Co., 752

F.2d 1356 (9th Cir. 1985)....................................... 28

Deveraux v. Geary, 765 F.2d 268 ( 1st Cir. 1985)....... 28

EEOC v. American Telephone & Telegraph Co., 419

F. Supp. 1022 (E.D. Pa. 1976), ajf’d, 556 F.2d 167

(3rd Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 438 U.S. 915 (1978) . 17, 18, 24

EEOC v. Local 638.. . Local 28 of the Sheet Metal

Workers’ International Association, 421 F. Supp.

603 (S.D.N.Y. 1975), ajf’d and modified in part,

532 F.2d 821 (2d Cir. 1976), laterproc., 565 F.2d

31 (2d Cir. 1977)...................................................... 4,18

iii

IV

EEOC v. Local 638.. . Local 28 of Sheet Metal

Workers, 753 F.2d 1172 (2d Cir.), cert, granted,

106 S. Ct. 58 ( 1985).................................................. 3,5,10,

27, 28, 29

Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality v. City of St.

Louis, 616 F.2d 350 (8th Cir. 1980), cert, denied,

452 U.S. 938 (1981 )................................................. 16

Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, 104 S. Ct.

2576 ( 1984)............................................................... 5,28

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980 ) ................ 17

General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125 ( 1976)... 25

Grann v. City of Madison, 738 F.2d 786 (7th Cir.

1983), cert, denied, 105 S. Ct. 296 ( 1984).............. 28

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)......... 16

Guardians Association of the New York City Police

Department, Inc. v. Civil Service Commission of the

City o f New York, 630 F.2d 79 (2d Cir. 1980), cert.

denied, 452 U.S. 940 (1981).............................. ...... 27

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 ( 1977)..................................... 14,15

Kromnick v. School District o f Philadelphia, 739 F.2d

894 (3d Cir. 1984), cert, denied. 105 S. Ct. 782

(1985)......................................................... .............. 28

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 ( 1965)....... 7

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 ( 1971).................... 17

Morrow v. Crisler, 3 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA)

1162 (S.D. Miss. 1971), afif’d, 479 F.2d 960 (5th

Cir. 1973), rev’d, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.) (en

banc), cert, denied, 419 U.S. 895 ( 1974)................ 8, 9, 15

NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703 (M.D. Ala.

1972), aff’d, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974)............. 9, 17, 18, 27

North Haven Board of Education v. Bell 456 U.S. 512

( 1982)................................................. ...................... 24

Paradise v. Prescott, 767 F.2d 1514(11th Cir. 1985),

petition for cert, filed, 54 U.S.L.W. 3424 (U.S. Dec.

10, 1985) (No. 85-999)........................................... 17,28

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265 ( 1978)........... .'........................................... 17

Rios v. Enterprise Association Steamfitters Local 638,

501 F.2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974).................................... 17

Page

V

Segar v. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249 (D.C. Cir. 1984), cert.

denied, 105 S. Ct. 2357 ( 1985)................................ 27

Sims v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 65, 353 F. Supp.

22 (N.D. Ohio 1972), ajf’d, 489 F.2d 1023 (6th

Cir. 1973).................................................................. 24

State Commission for Human Rights v. Farrell, 43

Misc. 2d 958, 252 N.Y.S.2d 649 (Sup. Ct. New

York Co. 1964)......................................................... 3

State Commission for Human Rights v. Farrell, 47

Misc. 2d 244, 262 N.Y.S.2d 526 (Sup. Ct. New

York Co.), aff’d, 24 A.D.2d 128, 264 N.Y.S.2d 489

(1st Dep’t 1965)....................................................... 3

State Commission for Human Rights v. Farrell, 52

Misc. 2d 936, 277 N.Y.S.2d 287 (Sup. Ct. New

York Co.), ajf’d, 27 A.D.2d 327, 278 N.Y.2d 982

(1st Dep’t 1967)....................................................... 3

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971)..................................................... 17

Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257 (D.C. Cir. 1982).. 16, 27

Thorn v. Richardson, 4 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. ( BNA)

299 (W.D. Wash. 1971).......................................... 24

Turner v. Orr, 759 F.2d 817 ( 11th Cir. 1985),petition

for cert, filed, 54 U.S.L.W. 3086 (U.S. July 31,

1985) (No, 85-177)................................................. 17,28

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977).................................... 17

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652

(2d Cir. 1971).......................................................... 13

United States v. Bricklayers, Local 1, 5 Fair Empl.

Prac. Cas. (BNA) 863 (W.D. Tenn. 1973)............ 24

United States v. Central Motor Lines, Inc., 325 F.

Supp. 478 ( W.D.N.C. 1970)................................... 24

United States v. City o f Alexandria, 16 Fair Empl.

Prac. Cas. (BNA) 930 ( E.D. La. 1977), rev’d, 614

F.2d 1358 (5th Cir. 1980)....................................... 17,25,26

United States v. City of Buffalo, 457 F. Supp. 612

(W.D.N.Y. 1978), modified and ajf’d, 633 F.2d

643 (2d Cir. 1980).................................................... 11,12,18,27

Page

VI

United States v. City of Buffalo, 609 F. Supp. 1252

( W.D.N.Y.), aff’d, No. 85-6212, (2d Cir. Dec. 19,

1985), petition for cert, filed sub nom. Afro-

American Police Association, Inc. v. United States,

—U.S.L.W.— (U.S. Dec. 24, 1985) (No. 85-

1085).......................................................................... 12,14,18

19,28

United States v. City o f Chicago, 411 F. Supp. 218

(N.D. 111. 1976), aff’d in part, rev’d in part, 549

F.2d 415 (7th Cir. 1977).......................................... 18,27

United States v. City of Chicago, 663 F.2d 1354 (7th

Cir. 1981) (en banc)................................................ 16,17

United States v. Dothard, 373 F. Supp. 504 (M.D.

Ala. 1974).................................................................... 10,15

United States v. Enterprise Association Local 638,

337 F. Supp. 217 (S.D.N.Y. 1972) ..... ................... 22

United States v. Frazer, 317 F. Supp. 1079 (M.D.

Ala. 1970)................................................................. 9

United States v. IBEW, Local 212, 5 Fair Empl. Prac.

Cas. (BNA) 469 (S.D. Ohio 1972), aff’d, 472 F.2d

634 (6th Cir. 1973)...... ............................................. 24

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 315 F. Supp.

1202 ( W.D. Wash. 1970), aff’d, 443 F.2d 544 (9th

Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971).................. 17, 18,20

22, 24

United States v. International Union of Elevator

Constructors, Local 5, 538 F.2d 1012 (3d Cir.

1976).......................................................................... 24

United States v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 625

F.2d 918 (10th Cir. 1979).......................................... 17

United States v. Masonry Contractors Association of

Memphis, Inc., 497 F.2d 871 (6th Cir. 1974).......... 17

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, 395 U.S. 225 ( 1969).......... ",............. '.............. 17

United States v. Wood, Wire & Metal Lathers Inter

national Union, Local 46, 341 F. Supp. 694

(S.D.N.Y. 1972), aff’d, 471 F.2d 408 (2d Cir.),

cert, denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973).............................. 24

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443 U.S.

193 (1979)............ .................................................... 19,20,25,26

Page

Van Aken v. Young, 750 F.2d 43 (6th Cir. 1984)....... 28

Vanguards of Cleveland v. City’ of Cleveland, 753 F.2d

479 (6th Cir.), cert, granted sub nom. Local Num

ber 93 v. City of Cleveland, 106 S. Ct. 59 ( 1985).... 2, 12, 27,

28, 29

Vogler v. McCarty, Inc., 1 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas.

(BNA) 197 (E.D. La. 1967), ajf’d sub nom. Heat

and Frost Insulators v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th

Cir. 1969)........................................................... .'..... 24

Williams v. City of New Orleans, 543 F. Supp. 662

(E.D. La.), rev’d, 694 F.2d 987 (5th Cir. 1982),

rev’d, 729 F.2d 1554 (5th Cir. 1984) (enbanc).... . 18,26,27

Wygant v. Jackson Bd. o f Education, 146 F.2d 1152

(6th Cir. 1984), cert, granted, 105 S. Ct. 2015

( 1985)....................................................................... 28

Statutes

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No.

88-352, 78 Stat. 241, (July 2, 1964), codified as

amended at 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et. seq. ( 1982):

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h)........................................ passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)........................................ passim

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L.

No. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103........................................... 20

M iscellaneous

118 Cong. Rec. ( 1972):

1662....................................................................... 21

1664 .................................................................... 21

1665 .................................................................... 22

1665-71.................................................................. 22

1671-75.................................................................. 22

1675 ..................................................................... 22

1676 .................................................................... 21,23

4918....................................................................... 23

vii

Page

Page

viii

Legislative History 1972: Subcommittee on Labor of

the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Wel

fare, Legislative History o f the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act o f 1972:

1017........................................................................ 21

1046........................................................................ 21

1047-63........................................................ 22

1048........................................................................ 22

1063-70................................................ 22

1071 ...................................................................... 22

1072 ..................................................................... 21

1074-75................................................................... 23

1715........................................................................ 23

1716-17................................................................... 23

1844........................................................................ 23

1848........................ 23

1902........................................................................ 23

CONSENT OF PARTIES

Petitioners and Respondents have consented to the filing of

this brief and their letters of consent have been filed with the

Clerk of the Court.

INTEREST OF AMICI

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

(“Lawyers’ Committee” ) is a nationwide civil rights organiza

tion that was formed in 1963 by leaders of the American Bar, at

the request of President Kennedy, to provide legal representa

tion to blacks who were being deprived of their civil rights. The

national office of the Lawyers’ Committee and its local offices

have represented the interests of blacks, Hispanics and women

in hundreds of class actions relating to employment dis

crimination, voting rights, equalization of municipal services

and school desegregation. Over a thousand members of the

private bar, including former Attorneys General, former presi

dents of the American Bar Association and other leading

lawyers, have assisted it in such efforts.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People is a New York nonprofit membership corporation. Its

principal aims and objectives include promoting equality of

rights and eradicating caste or race prejudice among the citizens

of the United States and securing for them increased opportu

nities for employment according to their ability.

The American Civil Liberties Union is a nationwide,

nonpartisan organization of over 250,000 members dedicated

to protecting the fundamental rights of the people of the United

States.

The National Black Police Association (“NBPA” ) is a

nationwide organization comprised of nearly 100 local black

police associations representing 720,000 black police officers

throughout the United States. Among the purposes of the

NBPA is the elimination of discrimination in public safety

2

departments, particularly in employment with its concomitant

effect of improving the delivery of public safety services to all

members of the community.

Amici have a direct interest in the long-established prin

ciple that Federal courts have wide discretion in fashioning

remedies for violations of Title VII and may impose classwide

numerical relief where necessary. Without such relief in

appropriate cases, we and our clients will be impeded—perhaps

totally precluded—in our efforts to vindicate the civil rights of

minority groups that have historically been victimized by

unlawful discrimination.

STATEMENT OF THE CASES

1. Local 93

On October 23, 1980, the Vanguards of Cleveland (“the

Vanguards” ), minority firefighters employed by the City of

Cleveland, filed a class action complaint in the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Ohio alleging

discrimination by the City in the hiring, promotion and assign

ment of minority firefighters in violation of the Thirteenth and

Fourteenth Amendments, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983.

The parties then entered into settlement negotiations, and

during the negotiations, Local 93 of the International Associ

ation of Firefighters (“Local 93” ) intervened.

The Vanguards and the City filed a proposed consent

decree on November 2, 1981. The court held evidentiary

hearings on January 7-8 and April 27-28, 1982, to consider

Local 93’s objections to the proposed decree.

On November 12, 1982, the magistrate reported that a

tentative agreement had been reached by the three parties. The

agreement, which contained promotional goals for minority

firefighters, was later rejected by the membership of Local 93.

The Vanguards and the City then submitted another

proposed consent decree that was substantially the same as the

3

plan negotiated by the leaders of Local 93 but rejected by the

Local 93 membership. Local 93 opposed court approval of the

decree.

The district court adopted the proposed consent decree on

January 31, 1983. The court found that the evidence “revealed

a historical pattern and practice of racial discrimination in

promotions in the City of Cleveland’s Fire Department”. The

court concluded that the affirmative action plan incorporated in

the proposed consent decree was a reasonable remedy in light

of that discrimination and adopted the consent decree as a fair,

reasonable and adequate resolution of the claims.

The Sixth Circuit, after reviewing the district court’s find

ings, held that the district court did not abuse its discretion in

approving the consent decree, affirmed the district court’s order

and denied Local 93’s request for a rehearing en banc.

2. Local 28

The Department of Justice instituted this action in the

United States District Court for the Southern District of New

York in 1971 against Local 28 and its Joint Apprenticeship

Committee (“JAC”) under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 to enjoin a pattern and practice of discrimination against

nonwhites.1 Shortly thereafter the EEOC was substituted as

plaintiff, the City of New York intervened as a plaintiff and the

New York State Division of Human Rights (“State” ), initially

named a third-party defendant, realigned itself with the EEOC

and the City.

After a three week trial in 1975, Judge Henry F. Werker

found that Local 28 and the JAC had purposely discriminated

against nonwhites in violation of Title VII.

1 Local 28 and its JAC had a long history of involvement in employment

discrimination litigation prior to the commencement of this action in 1971.

See State Commission for Human Rights v. Farrell, 43 Misc. 2d 958, 252

N.Y.S.2d 649 (Sup. Ct. New York Co. 1964); State Commission for Human

Rights v. Farrell, 47 Misc. 2d 244, 262 N.Y.S.2d 526 (Sup. Ct. New York

Co.), aff’d, 24 A.D.2d 128, 264 N.Y.S.2d 489 ( 1st Dept. 1965); State

Commission for Human Rights v. Farrell, 52 Misc.2d 936, 277 N.Y.S.2d 287

(Sup. Ct. New York Co.), aff’d, 27 A.D.2d 327, 278 N.Y.2d 982 ( 1st Dept.

1967).

4

In July 1975, the court entered an order and judgment

(“O&J” ) and appointed an administrator to propose and

implement an affirmative action plan (“AAP” ). The Second

Circuit affirmed Judge Werker’s finding that Local 28 and the

JAC intentionally violated Title VII, but reversed two provi

sions of the O&J and the AAP. 532 F.2d 821, 829-33 (2d Cir.

1976).

Judge Werker then adopted, and the Second Circuit

affirmed, a revised AAP and Order (“RAAPO”) that estab

lished a nonwhite membership goal of 29% to be achieved by

July 1, 1982, and ordered Local 28 and the JAC to develop the

apprenticeship program, to increase and maintain nonwhite

enrollment, to maintain detailed records regarding union em

ployment practices and to submit periodic reports summarizing

those records. 565 F.2d 31, 33-36 (2d Cir. 1977).

A. First Contempt Proceeding

On April 16, 1982, the City and State moved to hold Local

28 and the JAC in contempt for violating the district court’s

orders by failing to take the required steps to meet the 29%

membership goal by July 1, 1982.

In August 1982, Judge Werker, after studying voluminous

evidence, concluded that Local 28 and the JAC had “failed to

comply with RAAPO . . . almost from its date of entry” and

held Local 28 and the JAC in civil contempt. Local 28’s

contravention of court orders included: underutilization of the

apprenticeship program, refusal to conduct a general publicity

campaign, adoption of an older workers’ job protection provi

sion, issuance of unauthorized work permits to white workers

from sister locals and failure to maintain and submit records as

required by RAAPO and the EEOC. The court concluded: “I

am convinced that the collective effect of these violations has

been to thwart the achievement of the 29% goal of nonwhite

membership in Local 28 established by the court in 1975. . . . I

have no other recourse but to hold the defendants in civil

contempt of court.” Judge Werker imposed a $150,000 fine to

be placed in a training fund.

5

B. Second Contempt Proceeding

On April 11, 1983, the City brought a second contempt

proceeding, this time before the administrator, charging Local

28 and the JAC with further violations of the O&J, RAAPO and

orders of the administrator. The administrator, after a hearing,

found that Local 28 failed to provide records required by

RAAPO in a timely fashion, that Local 28 and the JAC failed to

provide accurate data and that Local 28 failed to serve RAAPO

on the contractors who hired Local 28’s members. He recom

mended that defendants again be held in civil contempt.

Judge Werker adopted the administrator’s recommenda

tion that Local 28 and the JAC be held in civil contempt and in

September 1983 Judge Werker adopted an amended AAP and

Order (“AAAPO”), that made six important changes in

RAAPO. Among other changes, AAAPO required that one

nonwhite apprentice be indentured for every white apprentice

and that contractors employ one apprentice for every four

journeymen employed; it also established a 29.32% nonwhite

membership goal to be reached by July 31,1987.

The Second Circuit affirmed all contempt relief ordered

against Local 28 and the JAC and rejected defendants’ argu

ments that the affirmative race-conscious relief contained in

AAAPO was prohibited by Title VII, the Constitution or this

Court’s decision in Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts,

104 S.Ct. 2576 (1984). However, the court carefully reviewed

AAAPO to ensure that the relief granted was warranted by the

factual findings of the district court. The Court affirmed

AAAPO but eliminated the intermediate one-to-one appren

ticeship ratio. 753 F.2d 1172, 1 183-89 (2d Cir. 1985).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Title VII was enacted to halt discriminatory employment

practices and to eradicate the present and future effects of past

discrimination. To achieve those goals, the courts were given

wide discretion and authority under section 706(g), 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5(g), to order effective relief.

6

Since the enactment of Title VII the Federal courts have

adjudicated thousands of employment discrimination cases. In

a small number of those cases the courts, after carefully

reviewing the evidence presented, determined that a classwide

numerical remedy was the only effective and practical remedy

sufficient to achieve the goals of Title VII. Every circuit has

reviewed the award of such relief in either a litigated decree or

a consent decree and every circuit has approved it.

In awarding or reviewing the imposition of numerical

remedies, the courts have taken great care to evaluate the

remedy awarded in light of the purpose and duration of the

goal and its effect on nonminorities. Numerical goals counter

balance deeply entrenched favoritism toward nonminorities

and foster inclusion of minorities in workforces from which they

had been excluded. When properly utilized and carefully

tailored, numerical goals do not result in invidious “reverse

discrimination” but simply and fairly bring nonminority ex

pectations into line with what would obtain had there been no

historical unlawful discrimination against minorities.

Nothing in the plain language of the statute or in the

legislative history of Title VII limits a court’s choice of remedies

to correct a violation of Title VII to “make-whole” relief for

identifiable victims of discrimination. As the courts that dealt

with employment discrimination cases for over two decades

recognized, racial discrimination is by its nature a class wrong

and though it is often impossible to identify individual victims,

many actual victims exist.

The elimination of classwide numerical relief as a possible

remedy would prevent the courts from effectuating the goals of

Title VII in the most egregious cases of racial discrimination.

Such a result would emasculate Title VII and effectively erase

more than twenty years of civil rights progress through the legal

system.

7

ARGUMENT

I. CLASSWIDE RACE-CONSCIOUS NUMERICAL RE

LIEF IS A PRACTICAL NECESSITY; IT IS SOME

TIMES THE ONLY REMEDY THAT CAN EFFEC

TUATE THE CRITICAL POLICY UNDERLYING

TITLE VII.

The central objective of Title VII is to “eliminate the

discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like dis

crimination in the future.” Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S.

145, 154 ( 1965). The courts, in a continuing effort effectively to

promote that policy, have come to the realization that section

706(g) cannot be interpreted, consistent with that objective, to

eliminate a court’s discretion under Title VII to order numerical

relief as the remedy in cases where such relief is necessary.

The failure of other remedies to achieve elimination of

“the last vestiges” of discrimination, Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 418 ( 1975), illustrates the direct conflict

between the position of petitioners and the Solicitor General on

the one hand, and the policies underlying Title VII on the other.

A. It Would Be Impossible Effectively To Enforce Title

VII Without Classwide Numerical Relief In Appropri

ate Cases.

Numerical relief is not required, nor should it be, in every

case in which violations of Title VII are found. There have

been thousands of employment discrimination cases litigated

since the enactment of Title VII; yet courts have found it

necessary to impose numerical goals in fewer than 100 of those

cases.2 Nevertheless, courts in every circuit have encountered

cases where the purpose of Title VII simply could not be

effectuated without the affirmance or imposition of classwide

numerical relief. In those cases an injunction reiterating Title

VII’s prohibition against discrimination or individual make-

whole relief would be useless and would result in endless

enforcement litigation. A Federal court must have the dis

2 That number is derived from reported litigated decrees.

8

cretion to tailor relief that it determines is necessary and that

will be effective in the specific situation before it.

1. Ingrained Patterns o f Racial Discrimination

Courts have justified the imposition of numerical relief in

several types of situations. In many of the cases where

numerical relief has been imposed, discriminatory practices

were particularly long-standing or egregious and resulted in

total or near total exclusion of minorities. In many instances

numerical relief was ordered only after injunctive or other relief

failed to eradicate the unlawful discrimination.

In 1974, the Fifth Circuit acknowledged the shortcomings

of relief that allowed the actor who committed the dis

criminatory practices to “self-correct” its own unlawful behav

ior. Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053, 1056 (5th Cir.) (en

banc), cert, denied, 419 U.S. 895 ( 1974).

In Morrow, the district court found that the Mississippi

Highway Patrol had engaged in unlawful discrimination in the

employment of patrol officers. Specifically, the court found that

while 36.7% of the population of the State of Mississippi was

black, the Mississippi Highway Patrol had never employed a

black officer. Of the 27 bureaus within the Department of

Public Safety, only two had any black employees and these

were low level jobs. Of the Department’s 743 employees, only

17 were black. The court declined to order affirmative numer

ical hiring goals or preferences and instead entered a decree

enjoining the Mississippi Highway Patrol from future unlawful

discrimination and requiring the Patrol actively to recruit black

patrol officers. 3 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1162 (S.D.

Miss. 1971). A Fifth Circuit panel affirmed:

“Time may prove that the district court was wrong,

i.e., that the relief ordered was not sufficient to

achieve a nondiscriminatory system and eliminate the

effects of past discrimination. But until the affirma

tive relief ordered has been given a chance to work,

we cannot tell.” 479 F.2d 960, 964 (5th Cir. 1973).

However, the Court en banc reversed and ordered the district

court to “fashion an appropriate decree which will have the

certain result of increasing the number of blacks on the

9

Highway Patrol”. 491 F.2d at 1055. The Court did so because

there was already strong evidence that lesser measures would

be ineffective: sixteen months after the entry of the decree, there

had been only six black patrol officers hired during a period

when 90 patrol officers were added to a total force of approxi

mately 500 troopers. The en banc court instructed the district

court to order, among other things, some form of affirmative

hiring relief such as temporary one-to-one or one-to-two hiring

ratios until the patrol was effectively integrated. Id. at 1056.

The Morrow court recognized that discrimination against a

class cannot be eliminated by a mere promise to hire more

minorities in the future. The court has an obligation to develop

a plan that “works and works now.” Id.

The need for race-conscious numerical relief is similarly

highlighted by a comparison of two cases arising in the Middle

District of Alabama, NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703

(M.D.Ala. 1972), tiff'd, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974), and

United States v. Frazer, 317 F. Supp. 1079 (M.D.Ala. 1970).

Allen was a private action brought to challenge the exclusion of

blacks from employment in the Alabama Department of Public

Safety. Frazer was an action brought by the Attorney General

to challenge racial discrimination against blacks in the employ

ment of persons engaged in the administration of federally

financed grant-in-aid programs in several Alabama agencies.

In both cases, the district court, Chief Judge Johnson,

made detailed findings of widespread discrimination against

blacks in recruitment and hiring highlighted by defendants’

nearly total exclusion of blacks from employment. Allen, 340

F. Supp. at 705; Frazer, 317 F. Supp. at 1087. Judge Johnson

ordered relief for specific black victims and prophylactic in

junctive relief in Frazer, 317 F. Supp. at 1090-93, and interim

and long term numerical hiring goals in Allen, 340 F. Supp. at

706.

Comparing progress under the Allen decree imposing

numerical goals on the Department of Public Safety and the

10

Frazer decree simply enjoining discrimination at a number of

Alabama agencies, Chief Judge Johnson stated:

“The Frazer decree has a much wider scope than

the Allen order, which focuses on only one

agency—the Alabama Department of Public Safe

ty—but the decree in Frazer lacks the precision

achieved in Allen through the use of hiring goals.

The contrast in results achieved to this point in the

Allen case and the Frazer case under the two orders

entered in those cases is striking indeed. Even

though the agencies affected by the Frazer order and

the Department of Public Safety draw upon the same

pool of black applicants—that is, those who have

been processed through the Department of Person

nel—Allen has seen a substantial black hiring, while

the progress under Frazer has been slow and, in

many instances, nonexistent. . . . Today the Alabama

Department of Public Safety has nearly one hundred

(100) blacks employed in nonmenial jobs in both

trooper and support positions. With its eighty (80)

black support personnel, the Alabama Department of

Public Safety has nearly as many black clerical

employees as all seventy-five (75) other Alabama

state agencies combined!

“Thus in a radical discrimination in employment

type case, when the parties are entitled to relief by

reason of the fact that their constitutional rights have

been violated, this Court’s experience reflects that the

decrees that are entered must contain hiring goals;

otherwise effective relief will not be achieved.”

NAACP v. Allen, sub nom. United States v. Dothard, 373 F.

Supp. 504, 506-07 (M.D. Ala. 1974) (footnotes omitted).

The facts in Local 28 also demonstrate that the mere

recalcitrance of some employers in complying with Title VII

could defeat the purpose of the Act if courts did not have the

power to order the discriminating employers to seek to achieve

numerical goals by a time certain.

11

Some employers and organizations have dug in their heels

and refused to comply with the mandates of Title VII, even

after a judicial finding of violation. In those cases, and in cases

in which numerical relief is necessary as a practical matter,

courts must have the power to order effective relief.

2. Removal of Disparate Impact o f Discriminatory Proce

dures

Courts have also determined that interim numerical goals

are a most effective and efficient method of removing the

discriminatory impact of an invalid hiring or promotional test.

Interim hiring or promotional goals eliminate the disparate

impact of the invalid selection practice, allow employers to

begin hiring and promoting immediately and prevent a further

violation of Title VII.

For example, affirmative interim hiring goals were proper

ly imposed in United States v. City of Buffalo, 457 F. Supp. 612

( W.D.N.Y. 1978), modified and aff’d, 633 F.2d 643 (2d Cir.

1980). In Buffalo, the district court, after a lengthy trial, found

that the City had engaged in a pattern and practice of

discrimination against blacks, Spanish-surnamed Americans

and women in police and firefighter hiring. The court found,

for example, that while 20.4% of the City’s population and

17.5% of its labor force were black, only 2.7% of the uniformed

police officers and 1.2% of the firefighters were black. 457 F.

Supp. at 621. The various tests for police and firefighter hiring

were found not to be demonstrably related to job performance.

Id. at 622-29. At the urging of the Department of Justice, the

court entered a final decree which included, among other

things, interim hiring goals providing that 50% of new police

appointments must be minorities and 25% must be women,

such goals to remain in effect until the city developed valid

selection procedures or until the percentage of minorities and

women in the police department equalled the percentage of

minorities and women in the City’s labor force. The Second

Circuit slightly modified the decree by eliminating its long term

aspects and affirmed the rest of the district court’s decree

including the interim goals:

“ [T]he ratio chosen was appropriate in light of ‘the

resentment of non-minority individuals against quotas

of any sort and of the need of getting started to redress

12

past wrongs.’ . . . The figures chosen here were not

unreasonably high in light of the finding of serious

discrimination and lack of previous progress, the slow

rate of hiring projected in the police department, and

the likelihood that prior discrimination had dis

couraged minorities and women from applying for

jobs.” 633 F.2d 643, 647 (2d Cir. 1980).

Thus while all police officer candidates must still take and

pass the non-valid test, the City’s selection of minorities, out of

rank order if need be, to satisfy the hiring goal eliminates the

discriminatory impact of the test. The interim hiring goals were

particularly effective since, after almost six years, the City has

still not developed a valid selection procedure. An order

requiring the City to develop valid selection procedures without

an interim hiring goal would plainly have been ineffective; it

also would have turned the district judge into a personnel

director, monitoring all new hiring to prevent further Title VII

violations.3

The promotional goals contained in the consent decree in

Local 93 are similar to the interim hiring goals ordered in

Buffalo. The promotional goals seek to remove the dis

proportionate impact of the City of Cleveland’s admittedly

discriminatory promotion procedures and to begin to eradicate

the effects of the past discrimination.

The use of interim hiring or promotional goals is particu

larly important in public sector cases like Buffalo and Local 93.

Without the use of some form of affirmative action there could

be no hiring or promoting (until valid selection procedures

could be developed). Such freezing of all appointments or

promotions in a city’s police or fire department could present a

hazardous situation to the citizens of the community. See, e.g.,

3 In 1985 the Department of Justice sought to modify the final decree,

arguing that after this Court’s decision in Stotts, the interim hiring goals were

unlawful. The district court denied the Department’s motion, rejecting the

Department’s interpretation of Stotts and holding that Stotts was in

applicable. 609 F. Supp. 1252 (W.D.N.Y. 1985). The Second Circuit

affirmed. No. 85-6212, slip op. (Dec. 19, 1985), and a petition for certiorari

was filed on December 24, 1985, sub nom. Afro-American Police Ass’n. Inc. r.

United States.

13

Berkman v. City o f New York, 536 F. Supp. 177, 216 (E.D.N.Y.

1982), aff’d, 705 F.2d 584 (2d Cir. 1983).

Interim hiring and promotional goals have occasioned very

little dispute because they merely end the discriminatory impact

of an otherwise unlawful test and are not unfair to nonmino

rities. They do not discriminate against “better qualified”

whites because the selection procedures they correct are not job

related; thus “better qualified” applicants cannot be identified.

See Commonwealth o f Pennsylvania v. Rizzo, 13 Fair Empl.

Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1475, 1481 (E.D. Pa. 1975).

B. Victim-Specific Relief Is Often Too Narrow To Achieve

The Goals Of Title VII.

The consensus among the courts on the appropriateness of

classwide numerical relief is premised in large part upon

practical considerations. It is easier to structure complete and

fair relief in cases where identifiable individuals have been

injured by unlawful discriminatory' employment practices. In

such cases courts award limited relief that will make those

specific, individual victims whole. However, many cases are not

limited to findings of individual discrete wrongs against a few

identifiable victims but involve long-standing and blatant dis

crimination against all class members.

In many of the most egregious cases, it is impossible to

point to a single individual as the victim. For example, given

Local 28’s long history of intentional discrimination and its

reluctance to change its discriminatory practices even after a

Court Order, it is certain that the Union rejected many, if not

all, black applicants for racial reasons. Further, it failed to keep

detailed employment records as required by EEOC regulations,

making it virtually impossible to find and identify actual victims

of petitioners’ discrimination. The only effective remedy in such

cases is one benefiting the class as a whole, see United States v.

Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652, 660 (2d Cir. 1971), and it

would be unfair to preclude such relief simply because a few

(or, indeed, many) class members may benefit even though

they were not identifiable victims of discrimination. Petitioners

and the Solicitor General contend that even in such a situation,

each applicant is required to show that had his or her appli-

14

cation been considered, without regard to race, he or she would

have been hired. That is inconsistent with the fundamental

purpose of Title VII.

The Second Circuit in reaffirming the interim hiring goals

ordered in Buffalo, supra, slip op. at 739, 742, stated:

“The hiring inequities were serious and were

clearly the product of discrimination. The harmful

effects were equally serious and broad in scope. The

victims were not simply a small number of identi

fiable persons who might be made whole by a

narrowly-drawn ‘make-whole’ decree but a large

group, most of whom could not be individually

identified. . . . Such broad discriminatory conduct

demands equally broad prospective equitable relief.

Otherwise the wrong will not be remedied. ‘Make-

whole’ relief, absent ability to identify the individual

victims, would be pointless and ineffective.”

This Court, in International Brotherhood o f Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324 ( 1977), addressed the danger of

limiting relief to an overly narrow group of plaintiffs. While

Teamsters did not pose the exact issue now before this Court,

the relief structured by the Court in that case illustrates a basic

point: denying affirmative relief to non-applicants and other

victims of discrimination who cannot readily be identified

“could exclude from the Act’s coverage the victims of the most

entrenched forms of discrimination. Victims of gross and

pervasive discrimination could be denied relief precisely be

cause the unlawful practices had been so successful as totally to

deter job applications from members of minority groups.” Id. at

365A 4

4 Justice Stewart, writing for this Court, cited decisions where courts have

granted affirmative relief under the National Labor Relations Act, the model

for Title VII’s remedial provisions, even though identification of specific

victims was impossible. Id. at 366-67. Justice Stewart also cited several Title

VII cases where courts of appeals had held that nonapplicants can be victims

of unlawful discrimination entitled to make-whole relief. Id.

15

Such a limitation on the equitable powers granted to courts by

Title VII

“would be manifestly inconsistent with the ‘historic

purpose of equity to secure complete justice’ and with

the duty of courts in Title VII cases ‘to render a decree

which will so far as possible eliminate the dis

criminatory effects of the past.’ ”

Id., citing Albemarle, 422 U.S. at 418.

C. Effective Eradication Of Past Discrimination Requires

Integration In The Workplace.

There is more to eliminating the “last vestiges” of employ

ment discrimination than simply enjoining discriminatory prac

tices. The lingering reputation of the employer as a dis

criminatory entity continues to pose a formidable obstacle to

minorities seeking entry into the workforce. As the en banc

Fifth Circuit pointed out a decade ago in Morrow, supra, 491

F.2d at 1056:

“ [W]e are not sanguine enough to be of the view

that benign recruitment programs can purge in two

years a reputation which discriminatory practices of

approximately 30 years have entrenched in the minds

of [minorities] . . . .”

On the other hand, if an employer is under an obligation to

hire or promote minorities, whether imposed by court-

structured relief or agreed to in a consent decree, the certain

result will be an increase in minority participation in that

employer’s institution. As awareness of that participation

spreads by word of mouth minorities will no longer perceive as

futile efforts to obtain jobs in the same employment sector. See

generally id.

Injunctions without numerical goals require tremendous

faith in the very same employer who felt no obligation to obey

Federal statutes outlawing employment discrimination in the

first place. The reality is that such faith is often misplaced. See,

e.g., Morrow, supra, 491 F.2d 1053; Dothard, supra, 373 F.

Supp. 504.

16

II. COURTS ARE INVESTED WITH WIDE DIS

CRETION UNDER SECTION 706(g) TO ORDER

CLASSWIDE RACE-CONSCIOUS NUMERICAL RE

LIEF WHERE SUCH RELIEF IS NECESSARY TO

EFFECTUATE THE PURPOSES OF TITLE VII.

A. Section 706(g) o f Title VII Permits Many Forms of

Relief Including Prospective Classwide Affirmative Re

lief And Make-Whole Relief As Remedies For Employ

ment Discrimination.

In enacting Title VII, Congress sought to eliminate em

ployment discrimination and eradicate the evils of its existence.

To do so, Congress took care to arm the courts with full

equitable powers and therefore section 706(g) explicitly au

thorizes courts “ to order such affirmative action . . . as the

court deems appropriate”. Pursuant to that broad equitable

power courts have ordered a wide range of relief for injuries

occasioned by discriminatory and unlawful employment prac

tices. See, e.g., Berkman, supra, 705 F.2d at 595-96.

“Make-whole” relief is intended “to make persons whole

for injuries suffered on account of unlawful employment dis

crimination”. Albemarle, supra, 422 U.S. at 418. Petitioners

and the Solicitor General concede that much.

Prospective race-conscious classwide relief, including nu

merical remedies, on the other hand, is directed to the achieve

ment of equality of employment opportunities and the removal

of barriers that have operated in the past to favor an identi

fiable group of white employees over other employees. See

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 429-30 (1971).

Eleven circuits have held that prospective affirmative race

conscious relief including numerical remedies is permissible

under Title VII5 and is sometimes the only effective and

practical remedy.

$ E.g., Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257, 294 (D.C. Cir. 1982);

Chisholm v. United States Postal Service, 665 F.2d 482, 499 (4th Cir. 1981);

Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality v. City o f St. Louis, 616 F.2d 350, 364

(8th Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 452 U.S. 938 ( 1981 ); United States v. City of

17

In addition this Court has steadfastly held in other contexts

that prospective affirmative classwide race-conscious relief is

not only constitutional but a most appropriate means of

remedying the effects of past discrimination.* 6

Until recently the government consistently sought the

imposition of classwide prospective numerical relief in cases

where such relief was necessary to effect complete relief. See

briefs filed by the United States at both the district and

appellate levels in: United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443

F.2d 544 ( 9th Cir.), cert denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971); NAACP

Chicago, 663 F.2d 1354, 1362 (7th Cir. 1981) (en banc); United States v.

City of Alexandria, 614 F.2d 1358, 1363-66 (5th Cir. 1980); United States v.

Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 625 F.2d 918, 943-44 ( 10th Cir. 1979); EEOC v.

American Telephone & Telegraph Co., 556 F.2d 167, 174-177 (3d Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 438 U.S. 915 (1978); Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc. v. Beecher,

504 F.2d 1017. 1027-28 (1st Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 910 ( 1975);

Rios v. Enterprise Association Steamfitters Local 638, 501 F.2d 622, 629 (2d

Cir. 1974); United States v. Masonry Contractors Association of Memphis,

Inc., 497 F.2d 871, 877 (6th Cir. 1974); United States v. Ironworkers Local

86, 443 F.2d 544, 553-54 (9th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971). The

Eleventh Circuit has approved consent decrees containing numerical rem

edies. Paradise v. Prescott, 767 F.2d 1514 (11th Cir. 1985), petition for cert,

filed, 54 U.S.L.W. 3424 (U.S. Dec. 10, 1985) (No. 85-999); Turner v. Orr,

759 F.2d 817 (1 1th Cir.), petition for cert, filed, 54 U.S.L.W. 3086 (U.S. July

31, 1985) (No. 85-177), but has not yet been directly confronted with the

validity of such relief under Title VII in a court ordered decree.

6 E.g., Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980) (“ 10% set aside” of

federal funds for minority businesses under provision of the Public Works

Employment Act of 1977 does not violate the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or the

Constitution); Regents o f the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265,

320 ( 1978) (Powell, J., joined by White, J .) and at 355-79 (Brennan, White,

Marshall and Blackmun, JJ., concurring) (State University may permissibly

use race as a factor in admissions); United Jewish Organizations of Williams-

burgh v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 ( 1977) (Reapportionment of voting districts in

accordance with specific numerical racial goals is permissible under of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965); McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) (To

insure integrated school system, School Board properly took racial figures into

account in redrawing school districts); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) (To insure integrated school system, court

may properly use racial ratios in both districting and faculty assignment and

order busing); United States v. Montgomery County Board of Education, 395

U.S. 225 (1969) (district court may properly order faculty and staff desegre

gation pursuant to flexible racial ratios in order to insure an integrated school

system).

18

v. Allen, supra, 493 F.2d 614; United States v. City o f Chicago,

549 F.2d 415 (7th Cir. 1977); Local 638, supra, 532 F.2d 821;

EEOC v. AT&T, supra, 556 F.2d 167; Buffalo, supra, 633 F.2d

643; United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 315 F. Supp. 1202

(W.D. Wash. 1970); NAACP v. Allen, supra, 340 F. Supp. 703;

United States v. City o f Chicago, 411 F. Supp. 218 (N.D. 111.

1976); Local638, supra, 421 F. Supp. 603, EEOC v. AT&T, 419

F. Supp. 1022 (E.D. Pa. 1976); Buffalo, supra, 457 F. Supp.

612.

Although prospective race-conscious numerical relief is still

necessary in certain cases, the Solicitor General now asserts that

such relief is unlawful. Petitioners and the Solicitor General

assert that the last sentence of section 706(g) prohibits class-

wide prospective relief and limits a court’s power to awarding

make-whole relief to identifiable victims of discrimination.

The Third Circuit rejected that argument in EEOC v.

AT&T, supra, 556 F.2d 167. That court carefully analyzed the

“make-whole” language and the legislative history of the last

sentence of section 706(g) and held that that sentence was

intended to strike an equitable balance between class members

seeking relief under Title VII and employers who are subject to

the mandates of Title VII. “ [T]he sentence does not speak at

all to the showing that must be made by individual suitors, or

class representatives on behalf of class members, or the EEOC

on behalf of class members. The sentence merely preserves the

employer’s defense that the non-hire, discharge, or non

promotion was for cause other than discrimination.” Id. at 176.

See also Williams v. City o f New Orleans, 729 F.2d 1554, 1558

n.4 (5th Cir. 1984) (en banc).

By its plain language section 706(g) establishes both

make-whole and classwide prospective relief as appropriate

remedies for Title VII violations. As recognized by the Second

Circuit last month:

“The source of the court’s power to issue broader

prospective relief is found in its powers as a court of

equity and in the broad language of § 706(g), which

authorizes the court to ‘enjoin the respondent from

engaging in such unlawful practice, and order such

19

affirmative action as may be appropriate, which may

include but is not limited to, reinstatement or hiring of

employees . . . or any other equitable relief as the

court deemed appropriate

Buffalo, supra, slip op. at 742 (emphasis in original).

The court in Buffalo noted that section 706(g) sets out a

nonexclusive list of possible remedies for Title VII violations

including “reinstatement or hiring of employees.” The

nonexclusivity of the listed remedies is apparent from Con

gress’s insertion of the language “which may include but is not

limited to” and the closing phrase “or any other equitable relief

as the court deems appropriate.” Id.

The last sentence of section 706(g) does not refer to or

affect in any way the discretionary power given to courts in the

language of the first sentence of section 706(g). The last

sentence addresses itself only to make-whole remedies and

means exactly what it says—no employer will be required to

hire, promote, reinstate or award back pay to any specified

individual unless that individual was an actual proven victim of

discrimination.

B. Congress Intended To Invest District Courts With Wide

Authority To Remedy Discrimination And Endorsed The Courts’

Use Of Affirmative Classwide Race-Conscious Numerical Re

medies In Appropriate Cases.

During the floor debates in both houses a common objec

tion vigorously pressed by opponents of Title VII was that it

would take autonomy away from employers and unions and

force them to hire unqualified minorities in order immediately

to integrate their work force and to maintain racial balances

without any showing or finding that the employer or union had

engaged in unlawful discrimination in violation of Title VII.

Of course, the bill proposed no such thing. Representative

Celler and Senator Humphrey emphasized the fact that nothing

in Title VII required an employer to maintain a racial balance

among employees through the use of a quota or to hire

unqualified minorities. As this Court noted in United Steel

workers o f America v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193, 206 (1979), section

20

703(j) was incorporated in the Dirksen-Mansfield substitute

bill to silence the opposition’s fears, and to make clear that Title

VII did not require the maintenance of a racial balance through

use of quotas.

In Weber this court recognized that 703 (j ) provides that

nothing in Title VII requires an employer to grant preferential

treatment to any group on account of a de facto racial

imbalance in the employer’s work force. Weber, supra, 443

U.S. at 206-07. The Department of Justice similarly interpreted

703(j), drawing the following distinction:

“ [W]here there has been an intentional policy of

unlawful racial discrimination resulting in the exclusion of

blacks from employment opportunities, as the lower court

found here, the limitation on preferential treatment [in

703(j) ] has no application.” Brief of Appellee United

States, at 49-50, filed Feb. 10, 1971, in United States v.

Ironworkers Local 86 (No. 26048 9th Cir.) (emphasis in

original).

The passage of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972, which amended Title VII, emphatically establishes the

proposition ( if it were unclear before) that classwide numerical

relief is a lawful remedy under section 706(g) and does not

violate section 703(j). The views of the 1972 Congress

expressed during the debates on the amending act are of

considerable significance.7 During the Senate’s consideration of

the amending act, Senator Ervin, one of the original opponents

of the Civil Rights Act, proposed two amendments to S. 2515,

the Senate equivalent of H.R. 1746 (the amending bill). The

7 The EEOC and Department of Justice now disavow their earlier

position that the statements of the 1972 Congress should be awarded great

weight in interpreting section 706(g).

“The ruling in Teamsters, supra n.39, that views of a later Congress

should be given little weight in interpreting a provision enacted in

1964, does not pertain here, since in 1972 the remedial provision of

Section 706(g) . . . was amended and expanded . . . .” Opp. Cert.

Brief of the Federal Respondents (Department of Justice and the

EEOC) filed in Communications Workers of America v. EEOC, Nos.

77-241, 242, 243 (Nov. 1977).

21

first amendment proposed to add a new section to the bill that

would read:

“No department, agency or officer of the United

States shall require any employer to practice dis

crimination in the reverse by employing persons of a

particular race, or a particular religion, or a particular

national origin, or a particular sex in either fixed or

variable numbers, proportions, percentages, quotas,

goals or ranges. . . . ”

118 Cong. Rec. 1662 (1972), Legislative History o f the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act o f 1972, reprinted in Subcomm. on

Labor of the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare

at 1017 (hereinafter “1972 Leg. Hist.” ).

Senator Javits, speaking against the amendment, noted

that the amendment would not only restrain a department,

agency or officer of the United States but would also affect a

court’s power to remedy discrimination under Title VII.8 Cong.

Rec. at 1664, 1972 Leg. Hist, at 1046. Accord id. at 1676, 1972

Leg. Hist, at 1072 ( remarks of Sen. Williams) (“I am desper

ately afraid—that this amendment would strip Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 of all its basic fiber. It can be read to

deprive even the courts of any power to remedy clearly proven

cases of discrimination. ” ).

There can be no doubt that at the time of the debates on

the Ervin Amendment Congress was fully aware that courts had

ordered classwide race-conscious numerical relief pursuant to

their powers under Title VII, and that the Philadelphia Plan, a

plan developed under Executive Order 11246 requiring govern

ment contractors to meet race-conscious numerical goals, had

been sustained by the Third Circuit. Senator Javits during the

floor debates described the facts and holdings of two cases and

caused the entire text of each case to be printed in the

8“ [T]he depth of this amendment is much greater than is apparent on

the surface because it would purport not only to inhibit in given respects the

officers of the United States but also the courts of the United States through

whom, once they make a finding or a judgment, the officers of the United

States are moved.” Id. at 1664, 1972 Leg. Hist, at 1046 (Remarks of Senator

Javits).

22

Congressional Record. Ironworkers Local 86, supra, 315 F.

Supp. 1202, reprinted at 118 Cong. Rec. 1665-71, 1972 Leg.

Hist, at 1063-1070, upheld the award of classwide, race

conscious numerical relief under Title VII, and Contractors

Association v. Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3d Cir.), cert,

denied, 404 U.S. 854 ( 1971), reprinted at 118 Cong. Rec. 1671-

75, 1972 Leg. Hist, at 1047-63, upheld the Philadelphia Plan as

being consistent with Title VII.9 Senator Javits then summa

rized his objections to the amendment:

“So, there I believe that the amendment does

two things, both of which should be equally rejected.

“First, it would undercut the whole concept of

affirmative action as developed under Executive Or

der 11246 and thus preclude Philadelphia type plans.

“Second, the amendment, in addition to dis

mantling the Executive order program, would de

prive the courts of the opportunity to order affirma

tive action under Title VII of the type which they

have sustained in order to correct a history of unjust

and illegal discrimination in employment and there

by further dismantle the effort to correct these in

justices.” Id. at 1665, 1972 Leg. Hist, at 1048.

9 Senator Javits also referred to United States v. Enterprise Association

Steamfitters Local 638, 337 F. Supp. 217 (S.D.N.Y. 1972 ), “ I am told, and 1

believe the information to be reliable, that under the decision made last week

by Judge Bonsai in New York, in the Steamfitters case, an affirmative order

was actually entered requiring a union local to take in a given number of

minority group apprentices.” Id. at 1665, 1972 Leg. Hist, at 1048. Senator

Javits also described two cases involving consent decrees negotiated by the

Justice Department:

“In one case, part of the decree required that 166 Negroes and

Puerto Ricans be given preference—in filling future vacancies for which they

were qualified.

“ In the other case in Kansas, the company agreed to make a good faith

effort to hire from three minority groups for 20 percent of the clerical positions

to be filled in the next three years.

“This amendment would make it impossible for the Justice Department

to obtain such decrees in the future.” Id. at 1675, 1972 Leg. Hist, at 1071.

23

The second amendment proposed by Senator Ervin sought

to apply section 703(j) to the executive, thus, as Senator Javits

noted, “ [making] unlawful any affirmative action plan like the

so-called Philadelphia Plan”. Id. at 4918, 1972 Leg. Hist, at

1715.

The Senate rejected both amendments by two-to-one

margins. Id. at 1676, 4918, 1972 Leg. Hist, at 1074-75, 1716-

17.

A section-by-section analysis of the final version of H R.

1746, the amending bill, submitted by the Conference Com

mittee of the House and Senate, provides:

“In any area where the new law does not address

itself, or in any areas where a specific contrary

intention is not indicated, it was assumed that the

present case law as developed by the courts would

continue to govern the applicability and construction

of Title VII.”

1972 Leg. Hist, at 1844. While the 1964 legislative history was

somewhat cloudy, the 1972 amendments to Title VII and

section 706(g)10 emphasize Congress’s intention to allow the

courts wide discretion in fashioning effective remedies, in

cluding numerical goals, for employment discrimination.

“The provisions of this subsection [706(g)] are

intended to give the courts wide discretion in ex

ercising their equitable powers to fashion the most

complete relief possible.” 1972 Leg. Hist, at 1848.

10 Title VII was extended to cover public employers and section 706(g)

was amended to include the italicized words:

“ If the court finds that the respondent has intentionally

engaged in or is intentionally engaging in an unlawful employ

ment practice charged in the complaint, the court may enjoin the

respondent from engaging in such unlawful employment practice,

and order such affirmative action as may be appropriate, which

may include, but is not limited to, reinstatement or hiring of

employees, with or without back pay . . ., or any other equitable

relief as the Court deems appropriate. Back pay liability shall not

accrue from a date more than two years prior to the filing of a

charge with the Commission . . . . ”

1972 Leg. Hist, at 1902.

2 4

Prior to the enactment of the 1972 amendments, numerical

goals or other group relief had been ordered in at least nine

Title VII cases,11 including Ironworkers Local 86, supra, printed

in the Congressional Record by Senator Javits. The courts had

clearly decided that Title VII did not prohibit classwide numer

ical remedies. Thus, Congress’s rejection of the Ervin amend

ment was an unambiguous endorsement of the judicial inter

pretation of the broad scope of section 706(g) remedial powers

conferred by the 1964 Act, including the power to order

classwide numerical relief. See, e.g., United States v. Inter

national Union of Elevator Constructors, Local 5, 538 F.2d

1012, 1019-20 (3d Cir. 1976); EEOC v. AT&T, supra, 556 F.2d

at 177 (“ [T]he solid rejection of the Ervin Amendment

confirmed the prior understanding by Congress that an affirma

tive action quota remedy in favor of a class is permissible.” ).

The Department of Justice and the EEOC, initially and

throughout the 1970s, consistently interpreted section 706(g) as

providing the Federal courts wide discretion in formulating

relief, including numerical remedies, for Title VII violations.

See, e.g., briefs submitted by the United States in United States

v. International Union of Elevator Constructors, Local Union

No. 5, supra; EEOC v. AT&T, supra. That interpretation

should be accorded deference. North Haven Board of Educa

tion v. Bell, 456 U.S. 512, 522 n. 12 (1982).

The Solicitor General’s new “interpretation” is not entitled

to any deference, however, because it is not contemporaneous

11 Vogler v. McCarty, Inc., 1 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 197, 200

(E.D. La. 1967), a ff’d sub. nom. Heat and Frost Insulators v. Vogler, 407 F.2d

1047, 1054 ( 5th Cir. 1969); United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, supra, 315

F. Supp. at 1247-52; United States v. Central Motor Lines, Inc., 325 F. Supp.

478, 479 (W.D. N.C. 1970); Thorn v. Richardson, 4 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas.

(BNA) 299, 303 (W.D. Wash. 1971); Buckner v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber

Co., 339 F. Supp. 1108, 1124 (N.D. Ala. 1972), aff’d, 476 F.2d 1287 (5thCir.

1973); United States v. Wood, Wire & Metal Lathers International Union,

Local 46, 341 F. Supp. 694, 698 (S.D.N.Y. 1972), aff’d, 471 F.2d 408 (2d

Cir.), cert denied, 412 U.S. 939 ( 1973); United. States v. IBEW, Local 212, 5

Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 469, 470, 478 (S.D. Ohio 1972), aff’d, 472 F.2d

634 (6th Cir. 1973); United States v. Bricklayers, Local I, 5 Fair Empl. Prac.

Cas. (BNA) 863, 881-82 (W.D. Term. 1973); Sims v. Sheet Metal Workers,

Local 65, 353 F. Supp. 22 (N.D. Ohio 1972), a ff’d, 489 F.2d 1023 (6th Cir.

1973).

25

with the enactment of the statute or its amendment. Cf

General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125, 140-43 ( 1976);

California Hospital Association v. Henning, 770 F.2d 856, 859

(9th Cir. 1985).

III. FEDERAL COL RTS HAVE AWARDED OR AP

PROVED NUMERICAL RELIEF ONLY AFTER A

CAREFUL EXAMINATION OF THE NEED FOR THE

RELIEF AND THE EFFECT SUCH RELIEF WOULD

HAVE ON NONMINORITIES.

The Federal courts have taken great care in shaping relief

to fit the specific situation presented. The courts have not

lightly and freely imposed or approved affirmative numerical

relief. Rather, the courts have limited and tailored affirmative

relief to meet the specific needs of each case while taking care to

limit and reduce the effects of such relief on nonminorities.

There is no specific standard governing the imposition of

numerical relief because the relief ordered in any particular

Title VII case must be unique and individual to the specific facts

of that case. Nevertheless, certain factors useful in assessing the

advisability of affirmative relief have been developed.

The factors most commonly considered by courts were

articulated by this Court in Weber, supra, 443 U.S. 193. This

Court, while declining to “define in detail the line of demarca

tion between permissible and impermissible affirmative action

plans”, nevertheless examined the purpose and duration of

Kaiser’s affirmative action plan and its effect on third parties

before determining that the “plan falls on the permissible side

of the line.” Id. at 208.

The courts’ responsible use of discretion and careful adher

ence to this Court’s guidance in Weber is exemplified by two

cases in the Fifth Circuit. In United States v. City o f Alexan

dria, 614 F.2d 1358 (5th Cir. 1980), the Fifth Circuit used the

same factors that were discussed in Weber to review de novo

the proposed settlement between the Department of Justice and

the City of Alexandria, which the district court had declined to

approve, because it contained affirmative hiring relief for

women and blacks in the police and fire departments. Id. at

2 6

1361. The Fifth Circuit determined that the proposed consent

decree was appropriate given the presence of severe statistical

imbalances. The court noted that the goals were temporary,

did not bar the advancement of white males and did not require

defendants to consider unqualified women and blacks for

vacancies. The court concluded that “the goals will thus serve

to prevent those responsible for personnel decisions from

automatically choosing a white male when there is a qualified

black or female. This attempt to break down traditional

patterns which foreclose opportunities to blacks and women

was the motivation behind Title VII.” Id. at 1366 (citations

omitted).

Accordingly, the court reversed the district court’s refusal

to enter the consent decree and remanded, instructing the

district court to enter the decree. Id. at 1367.

In Williams v. City o f New Orleans, 543 F. Supp. 662 (E.D.

La. 1982), the district court, after a four day fairness hearing,

declined to approve the proposed consent decree unless the

one-to-one promotion goal was deleted. The trial court deter

mined that the goal exceeded the court’s remedial objectives

and seriously jeopardized the career interests of nonminorities.

A three-judge panel of the court of appeals concluded that the

trial court had abused its discretion in conditioning its approval

of the proposed consent decree on the deletion of the promotion

goal and remanded the case instructing the court to sign the

decree. 694 F.2d 987 (5th Cir. 1982).

On rehearing en banc, the Fifth Circuit found that the

district court, properly following the Weber guidelines, did not

abuse its discretion in finding that the “one-to-one promotion

ratio was overbroad and unreasonable in light of the severe and

longlasting effect on the rights of women, Hispanics and non-

Hispanic whites.” 729 F.2d 1554, 1561 (5th Cir. 1984) {en

banc). The panel emphasized:

“The ideal goal in this type case is to provide a

suitable remedy for the group who has suffered, but

at the least expense to others. . . . [W]e do not

modify our previously expressed view that temporary

hiring goals are ordinarily reasonable. . . . ‘Title VII

27