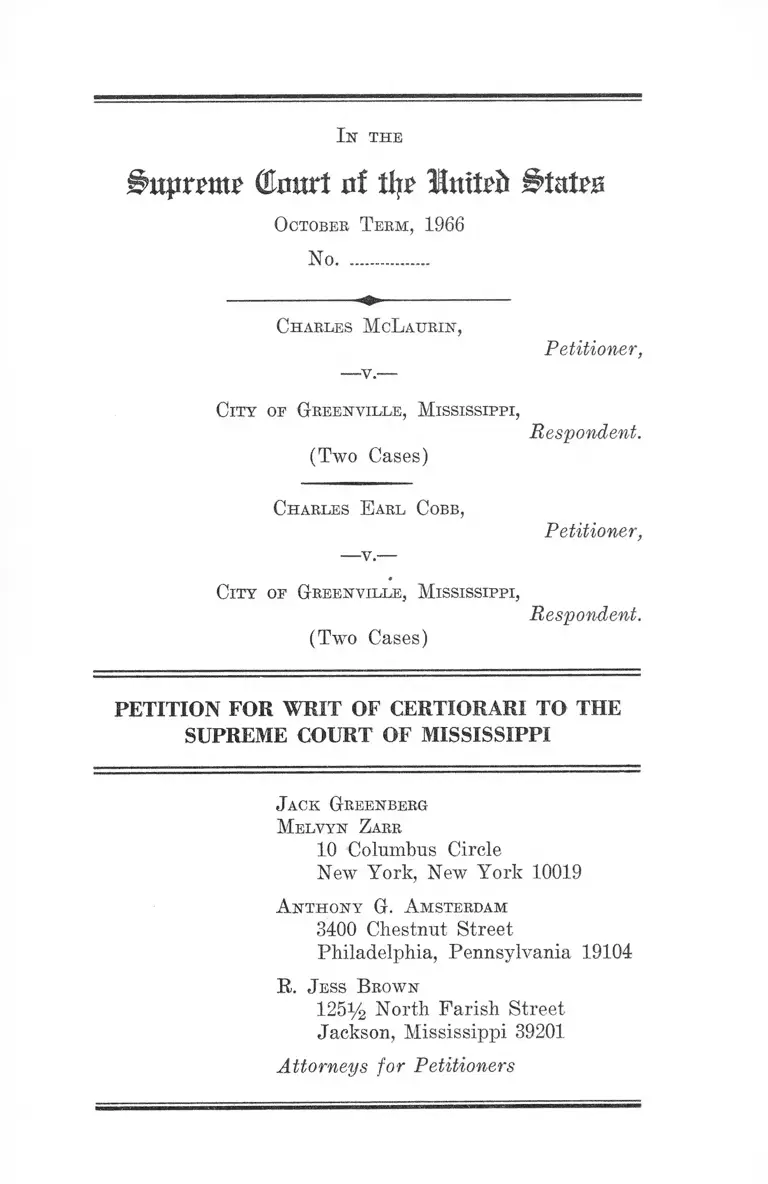

McLaurin v. City of Greenville, Mississippi Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McLaurin v. City of Greenville, Mississippi Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1966. 1a887eba-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5d0a341e-af05-435b-95c0-8b057bc80b09/mclaurin-v-city-of-greenville-mississippi-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(Enurt of tip lotted #tat?js

October Teem, 1966

No..................

Charles McLahrin,

Petitioner,

— v.—

City op Greenville, Mississippi,

(Two Cases)

Charles E arl Cobb,

Respondent.

Petitioner,

City op Greenville, Mississippi,

(Two Cases)

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

Jack Greenberg

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

R. Jess B rown

125% North Parish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below .................................................................. 2

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 2

Questions Presented............................................................ 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 4

Statement ...................... 5

Summary of the Evidence ........................................ 7

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and De

cided Below .............................................................. 14

R easons foe Granting the W rit

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Review and

Reverse Petitioners’ State Criminal Convic

tions, Which Punish Them for the Exercise

of Their Federal Constitutional Rights of

Free Speech, Assembly and Petition and Con

flict With Decisions of This Court .............- 15

II. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Review and

Reverse Petitioners’ State Criminal Convic

tions, Which Deprive Them of Their Liberty

Without Due Process of Law Because

Founded Upon No Evidence of Guilt ........... 20

III. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Review and

Reverse Petitioners’ State Criminal Convic

tions Under a Statute Indistinguishable From

That Declared Facially Unconstitutional by

This Court in Cox v. Louisiana....................... 21

11

IV. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Review and

Reverse Petitioner Cobb’s Conviction for

Resisting Arrest Because His Right to Equal

Protection of the Laws Was Violated by the

Trial Court’s Refusal to Permit Him to Show

Systematic Exclusion of Negroes Prom the

Petit Jury Through Prosecutorial Abuse of

Peremptory Challenges.....................-.............. 24

Conclusion.................................................................................. 26

A ppendix

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case ......................... la

Judgment of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case........................... 14a

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Resisting Arrest Case ......................... 15a

Judgment of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Resisting Arrest Case .......................... 16a

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

Cobb Breach of Peace C ase.................................... 17a

Judgment of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

Cobb Breach of Peace Case .................................. 18a

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

Cobb Resisting Arrest C ase.................................... 19a

Judgment of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

Cobb Resisting Arrest Case.................................... 20a

PAGE

Ashton v. Kentucky, 384 U. S. 195 (1966) ..... ......... 20,23

Bolton v. City of Greenville, 253 Miss. 656, 178 So. 2d

667 (1965) .....................................................................- 8

Bynum v. City of Greenville, 253 Miss. 667, 178 So. 2d

672 (1965) ........................................................................ 8

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 (1940) ........... 22

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 (1942) .... 18

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965) ....4,16,17,18,19, 22

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965) .... .......... 23

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963) ....16,17,

18,19, 22

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315 (1951) ................... 18

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 (1961) ................... 20

Henry v. City of Bock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964) ....22,24

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ....................... 23

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U. S. 87 (1965) ..21, 22

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 (1931) ........— 22

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 202 (1965) ....................... 25

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 (1962) ................— 20

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 (1949) ...............16, 22

Thomas v. Collins, 332 U. S. 516 (1945) ........... ........... 22

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 TJ. S. 199 (1959) ...... ........ 20

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940) ------- -------- 22

I l l

PAGE

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 287 (1942) ....... 22

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) .......................3, 21

Statutes and Ordinances

28 U. S. C. §1257(3) ........................................................ 2

Miss. Code Ann. §2089.5 (Supp. 1964) ...................3,4,5,21

Other A uthorities

Chafee, Free Speech in the United States (1954) ....... 20

i v

PAGE

Isr th e

Supreme (tort ni tljr llmtrft States

October T erm, 1966

No..................

Charles McL aurin,

Petitioner,

—v.—

City of Greenville, Mississippi,

Respondent.

(Two Cases)

C harles E arl Cobb,

Petitioner,

— v .—

City of Greenville, Mississippi,

Respondent.

(Two Cases)

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Mississippi entered

in the above-entitled cases on June 13, 1966. Rehearing

was denied on July 8, 1966.

b. Petitioners were convicted upon no evidence of guilt?

c. Petitioners were convicted under a statute indis

tinguishable from that declared facially unconstitutional in

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536, 551-52 (1965)?

2. Does petitioner Cobb’s conviction for resisting ar

rest offend the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment because the trial court refused to permit him

to show a pattern or practice of systematic prosecutorial

exercise of peremptory challenges to strike Negroes from

the petit jury?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the First Amendment and Section 1

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

This case also involves the following statute of the State

of Mississippi:

Miss. Code Ann. §2089.5 (Supp. 1964)—Disturbance of

the public peace, or the peace of others.

1. Any person who disturbs the public peace, or the peace

of others, by violent, or loud, or insulting, or profane,

or indecent, or offensive, or boisterous conduct or

language, or by intimidation, or seeking to intimidate

any other person or persons, or by conduct either

calculated to provoke a breach of the peace, or by

conduct which may lead to a breach of the peace, or by

any other act, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and

upon conviction thereof, shall be punished by a fine of

not more than five hundred dollars ($500.00), or by

imprisonment in the county jail not more than six

(6) months, or both.

,4

5

Code of Ordinances of the City of Greenville, Section

252—Resisting Arrest.

Any person who knowingly and wilfully opposes or re

sists any officer of the city in executing, or attempting

to make any lawful arrest, or in the discharge of any

legal duty, or who in any way interferes with, hinders

or prevents, or offers or endeavors to interfere with,

hinder or prevent, such officer from discharging his

duty, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.

Statement

Petitioners Charles McLaurin and Charles Earl Cobb,

Negro civil rights workers, were arrested on July 1, 1963

in the City of Greenville, Mississippi and charged with

breach of the peace, in violation of Miss. Code Ann. §2089.5

(Supp. 1964), set forth p. 4, supra, and with resisting

arrest, in violation of a Greenville City ordinance, set forth

p. 5, supra (RA 3; RB 8; RC 5; RI) 6).

On July 3, 1963, petitioners were tried and convicted on

these charges in the Municipal Court of the City of Green

ville (187 So. 2d at 855; RA 206).

Petitioners appealed to the County Court of Washington

County for trials de novo on their four charges. There, in

four separate jury trials,3 petitioners were again convicted

3 Petitioner McLaurin was tried and convicted of breach of the

peace on September 16, 1963 (RA 13) ; he was tried and convicted

of resisting arrest on September 20, 1963 (RB 16). Petitioner Cobb

was tried and convicted of breach of the peace on September 17,

1963 (RC 13-14); he was tried and convicted of resisting arrest

on September 20, 1963 (RD 16).

This case also involves the following ordinance of the

City of Greenville, Mississippi:

6

Petitioners appealed their convictions to the Circuit

Court of Washington County, which affirmed.4 Appeals

were allowed to the Supreme Court of Mississippi, where

the four cases were consolidated for argument.5

On June 13, 1966, the Supreme Court of Mississippi af

firmed petitioners’ convictions in four separate orders, with

an extensive opinion in the McLaurin breach of the peace

case (187 So. 2d at 855-60; EA 206-19; EB 161-62; EC

173; ED 168). Petitioners’ suggestions of error were over

ruled on July 8, 1966 (EA 222; EB 165; EC 176; ED 171).

In each of the four cases covered by this petition and

others tried in the same court during the same week, coun

sel for petitioners attempted to show a pattern or practice

of systematic prosecutorial exercise of peremptory chal

lenges to strike Negroes from the petit juries. In the cases

first tried—petitioners’ breach of the peace prosecutions—

counsel was permitted to state for the record the number

of Negroes peremptorily excused by the prosecutor. In the

Cobb resisting-arrest case, counsel tried to introduce the

figures on Negro peremptory challenges which he had

compiled “ in these cases all during the week” (ED 24).

and sentenced to pay a fine of $100.00 and serve a term of

90 days in the city jail on each charge.

4 Petitioners’ breach of the peace convictions were affirmed on

February 27, 1964 (RA 106-07; RC 82-83) ; petitioners’ resisting

arrest convictions were affirmed on July 24, 1964 (RB 80; RD 87).

5 After submission of the eases to the Supreme Court of Mis

sissippi, it was discovered that the affidavits upon which the charges

were based were not included in the records, although they had

been designated by petitioners in their notice of designation of the

record. Respondent City of Greeenville suggested a diminution

of the record, which was sustained by the court, thereby correcting

the omission. (------ Miss. —— , 180 So. 2d 927 (1965); 187 So. 2d

at 855.)

7

The trial court disallowed this proffer on the stated ground

that “ This is a separate ease altogether” (Ibid.). Counsel

explained that “ only [to] show what happened in one case

would not be enough to prove systematic exclusion, but if

we can show a pattern of what happened in enough cases,

then we are in a better position to argue [the] contention”

(KD 25). The court adhered to its ruling, stating:

. . . Your motion is well in the record and your mo

tion specifically states what you are seeking to do and

the Court understands that and the record shows that,

and if this Court is in error by not permitting you to

show that pattern, then you don’t have to show that

pattern to the Supreme Court at all, the Supreme

Court will reverse it because it didn’t let you do it.

Your record is all right for that purpose (RD 25-26).

Summary of the Evidence

The arrest of petitioners was precipitated by the trial

of two Negro girls in the Municipal Court of the City of

Greenville on July 1, 1963, on charges of disorderly con

duct (App. p. 3a; 187 So. 2d at 856; RA 208). Petitioners

attended the trial, along with about 150 other Negroes and

an approximately equal number of whites. During the

trial petitioner McLaurin attempted to sit on the side of

the courtroom customarily reserved for whites, but he was

ordered out of that section (RA 24, 30-33, 64, 75-76; RB

55-56, 65-66). Petitioner McLaurin left the courtroom and

protested the segregated seating pattern to police chief

W. C. Burnley (RA 208). His protest was futile, and he

was then denied readmission to the courtroom (RA 208).

Petitioners then left the Municipal Building, which housed

the Municipal Court and the police station, and stood out

8

side on the sidewalk waiting for the trial to end and for

the spectators to emerge (RA 75-76). About 50 Negroes

were standing outside the building, having been denied ad

mission to the courtroom because the Negro side was com

pletely filled (although there was some space on the white

side) (RA 76).

The girls were convicted by the Municipal Court.6 As

the spectators left the municipal building, petitioner Mc-

Laurin began to address them in a loud voice, protesting

the conviction of the girls and the evils of segregation and

calling for mass Negro voter registration to achieve

equality (RA 78-79, 90, 92). Police officer Carson then

arrested petitioner McLaurin (RA 209). Next, petitioner

Cobb began to address the crowd in much the same vein

as petitioner McLaurin, and he was arrested by police

officer Martin (RC 30, 59-60).

Because the nature and content of petitioners’ speeches

and the context in which they were delivered are of crucial

importance to decision of this case, the evidence adduced

in these four cases will be summarized separately, as fol

lows :

McLaurin Breach of the Peace Case

Arresting officer Carson testified that petitioner Mc

Laurin loudly protested the Court’s decision, saying that

6 At their trial police officers testified that they were arrested

and charged with disorderly conduct because they refused to leave

a public park when the police ordered them to do so because police

feared that, if they stayed, the white crowd that was gathering

around them would become violent. Their convictions were sub

sequently reversed by the Mississippi Supreme Court in Bolton v.

City of Greenville, 253 Miss. 656, 178 So. 2d 667 (1965) and

Bynum v. City of Greenville, 253 Miss. 667, 178 So. 2d 672 (1965).

9

it was wrong, that segregation was wrong and that some

thing should be done to right these wrongs (RA 25, 28,

36, 209). Apprehending that the crowd was becoming

“ tense” (RA 27, 209), Carson told McLaurin that he could

not continue speaking without a permit (RA 28) and, when

McLaurin continued, arrested him (RA 28). Police captain

Harvey Tackett and police chief W. C. Burnley also testi

fied for the City of Greenville. Captain Tackett was un

clear as to the exact content of petitioner McLaurin’s

speech, but he recognized it as a speech of protest against

segregation and a general query to the crowd as to what

they were going to do about it (RA 45, 210). Chief Burnley

was also near the scene and testified that McLaurin’s

speech included queries to the crowd: “What are you

going to do? Are you going to let this happen! Statements

of that type” (RA 54, 211).

None of the prosecution witnesses heard any profane

language on the part of petitioner McLaurin (RA 36-37,

51-52), nor any call for violence (RA 37-38), nor was there

any testimony that McLaurin’s speech disturbed a court

in session.

Petitioner McLaurin testified on his own behalf. He de

scribed the content of his speech as follows:

I was saying different things like, this wouldn’t have

happened if Negroes were registered to vote, that in

Washington County Negroes are in the majority of

the population—50% of the population is Negro and

that they could have used the park or any other thing

had they been registered voters (RA 77, 213).

. . . [T]he words that I was using wouldn’t have caused

them to jump—to go in there and try to beat up the

10

Judge. Negroes know they can’t go beat up the Judge

and be justified, and tear down the building and be

justified, or jump on a policeman in the State of Mis

sissippi and be justified (RA 79, 213-14).

Petitioner McLaurin also testified as to what he intended

by his speech:

I meant that if they were registered—if the people

would register to vote, were to get in line and exer

cise their duties and responsibilities as citizens, as

Negro citizens, and as citizens of the United States,

they could change some of these things. They could

change the policy of being arrested in a park that they

paid for as well [sic] any other people and that there

wouldn’t be such parks that was designated for whites

and for Negroes. . . . And, the only thing that I had

in mind was to get [the crowd] to register to vote and

to realize what was happening, and I felt that I had

a right to do this under the 1st Amendment (RA 78-

79).

* # # # *

I was going to tell them what had taken place with

respect to the park and with my being asked to leave

the courtroom. That’s what I was speaking of, I was

speaking of the fact that the kids had been arrested

because they used the public park that had been set

aside for whites and the fact that I was thrown out

of the courtroom because I had used the side that had

been set aside for the whites on the right side of the

building, you know (RA 92).

All three prosecution witnesses agreed that the predomi

nantly Negro crowd of ajjproximately 200 was “mumbling”

11

(EA 27, 42, 45-46, 57) and appeared upset, but no threat

of violence, either directed at the speaker or at city authori

ties, was heard nor did anyone in the crowd appear to be

armed (EA 42, 68). After the arrest of petitioners, the

crowd was easily dispersed (EA 48; ED 47).

McLaurin Resisting Arrest Case

Officer Carson testified that, after he told petitioner Mc

Laurin that he was under arrest, McLaurin kept address

ing the crowd. Carson testified that he took McLaurin by

the arm and then pushed him from behind into the police

station (EB 33-34). McLaurin tried to brace his feet and

“began to pull back” (EB 33), but offered no greater re

sistance to Carson, who outweighed him by 60 pounds (EB

38, 59). Once inside the police station, McLaurin fell to

the floor and lay motionless there (EB 34). He was then

picked up and carried to the sergeant’s desk for booking,

after which he voluntarily got up (EB 35).

McLaurin testified that after he had begun to speak,

Carson came up to him and told him that he could not

speak without a permit (EB 60). McLaurin continued to

speak, and Carson took him by the arm and told him that

he was under arrest (EB 60). Carson then pushed him

from behind into the police station. While McLaurin did

not struggle, he concededly made Carson supply the energy

needed to propel him into the police station (EB 60-61).

McLaurin admitted that, once inside the police station, he

went limp (EB 61). His action, he testified, was equivalent

to saying: “ [H]ere’s my body, it is you that wants me in

jail, then, carry me to jail” (EB 68).

12

Cobb Breach of the Peace Case

Arresting officer James Martin testified that petitioner

Cobb asked the crowd: “ [A ]re we going to stand for this,

and watch my partner go to jail, what are you going to do

about it !” (EC 30). Captain Tackett also testified as to

what Cobb said:

He said, you see what they are doing to him, are you

going to stand here and let them do it? He said this

is everybody’s fight and so on (EC 43).

And police chief Burnley testified that Cobb said:

Are you going to take this, they are taking him away

to jail, let’s all go to jail (EC 51).

But Martin and Burnley both admitted that Cobb did not

encourage the crowd to commit any act of violence (EC

37, 55).

Petitioner Cobb testified that, after McLaurin had been

arrested, he stood on the steps of the Municipal Building,

“and I was telling them that the two girls had been arrested

for using a public park paid for with your tax money. I

said McLaurin has been taken to jail for trying to tell you

about it, and that I think we all ought to be in jail with

McLaurin” (EC 59). Cobb was told by Martin that he was

under arrest for speaking without a permit (EC 59).

Cobb explained what he meant when he said, “ I think

we all ought to be in jail with McLaurin” :

[T]he point that I was trying to bring out to the

people was that the two girls had not only been ar

rested illegally, but unjustly and that McLaurin had

been arrested not only illegally but unjustly, and that

13

if this was the kind of society and the kind of system

that arrested people unjustly and illegally and called

it legal and just, then I felt all the legal and just people

should be in jail because I feel that in an illegal and

unjust system and society, the real just people will

wind up in jail simply because the unjust and illegal

people will not tolerate any kind of honest or just

thinking or actions (EC 60).

Petitioner Cobb did not intend his listeners to go to

jail by committing violence, but intended that the crowd

“ just go on in voluntarily into the cells” (EC 62).

The prosecution witnesses testified that the crowd of

about 200 was “angry” (EC 30) and “ muttering” (EC 43,

52), but that no threat of violence emanated from the crowd

(EC 52-53). There was no evidence that Cobb’s speech dis

turbed a court in session. The crowd did nothing to hinder

the arrest of petitioners, nor did the arresting officers

fear such hindrance (ED 36).

Cobb Resisting Arrest Case

After Officer Martin told petitioner Cobb that he was

under arrest for speaking without a permit (ED 32), he

grabbed Cobb by the arm and dragged him into the police

station (ED 33, 68). Officer Martin, outweighing peti

tioner Cobb by 100 pounds (ED 37), testified that Cobb

“ just put all his weight on me” (ED 33). Captain Tackett

also testified as to what Cobb had done: “ He was trying

to back up, pushing back, and looking back over his

shoulder, hollering, still shouting” (ED 46). After Cobb

was pushed into the police station he went limp and was

carried to the sergeant’s desk for booking (ED 33). After

14

booking, Cobb voluntarily got up and walked to his cell

(ED 34).

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

In the County Court of Washington County, petitioners

preserved each of the issues presented here by a motion

for directed verdict (RA 62-63; RB 52-53; RC 56-57; RD

64-65) and by a motion for new trial (RA 96-97; RB 16a-

16b; RC 15-16; RD 17-18); these motions were denied

(RA 63, 97; RB 53, 16b; RC 57, 16; RD 66, 18).

In the Circuit Court of Washington County, petitioners

preserved each of the issues presented here in their assign

ments of errors (RA 104; RC 80).7

In the Supreme Court of Mississippi, petitioners pre

served each of the issues presented here (RB 93; RC 101;

RD 100).8 The Supreme Court of Mississippi considered

and determined on the merits each of the issues raised in

this petition (App. pp. 2a-3a; 187 So. 2d at 855, 860-61;

RA 207).

7 The assignments of errors in petitioners’ resisting arrest cases

were omitted from these records.

8 The assignment of errors in MeLaurin’s breach of the peace

case was mistakenly omitted from that record.

15

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Review and Reverse

Petitioners’ State Criminal Convictions, Which Punish

Them for the Exercise of Their Federal Constitutional

Rights of Free Speech, Assembly and Petition and Con

flict With Decisions of This Court.

Petitioners were charged with “ disturb [ing] the public

peace by loud or offensive language, or by conduct either

calculated to provoke a breach of the peace, or by conduct

which might reasonably have led to a breach of the peace”

(RA 3; RC 5). Petitioners submit that Mississippi may

not constitutionally punish them pursuant to these charges

for engaging in the type of conduct which this record

reveals.

This record reveals that petitioners’ conduct consisted

solely of speech—speech, to be sure, of a vigorous and stir

ring nature—but constitutionally protected speech nonethe

less. The speeches which petitioners gave were to a crowd

of about 200 Negroes on the public sidewalk, most of whom

had just left a segregated courtroom after witnessing the

trial and conviction of two Negro girls for having sought to

enjoy a white-only municipal park. They were speeches of

protest designed to draw public attention to the evils of

racial discrimination and segregation as practiced in the

community. Petitioners intended to stir persons in the

crowd to action, viz., assertion of their federal rights.

The fact that petitioners were arrested before they could

fully make their point about the necessity of Negroes regis

tering to vote and exercising other federal rights does not

16

deprive them of federal protection. What petitioners did

succeed in saying merely amounted to a call to action;

but nowhere in the record is there any indication that it

was a call to unlawful action. What petitioners said may

have “brought about a condition of unrest” , but it has

long since been settled by this Court that a conviction

resting on that ground may not stand. Termmiello v.

Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, 5 (1949).

Petitioners could constitutionally be punished only if

they intended to incite their listeners to riot or used lan

guage whose natural and foreseeable effect under the cir

cumstances would provoke their listeners to acts of vio

lence.9 Thus, the central issue presented here is whether

the design or content of petitioners’ speech (analyzed in

the context of the composition and mood of the crowd)

exceeded the boundaries of protected free speech. Petition

ers submit it did not.

The constitutional guidelines for decision here are pro

vided by Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963)

and Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965). Analysis of

these cases reveals that petitioners’ speeches merit no less

federal protection than that afforded the speeches delivered

in Edwards and Cox.

In Edwards,

the petitioners engaged in what the City Manager

described as ‘boisterous’, ‘loud’, and ‘flamboyant’ con

duct, which, as his later testimony made clear, con

sisted of listening to a ‘religious harangue’ by one of

9 The record makes clear that no profane language was used by

the petitioners. Nor is there any evidence in the record that peti

tioners disturbed a court in session.

17

their leaders, and loudly singing ‘The Star Spangled

Banner’ and other patriotic and religious songs, while

stamping their feet and clapping their hands (372

U. S. at 233).

The speaker in Edwards had “ harangued” approximately

200 of his followers and at least an equal number of by

standers on the State House grounds in Columbia, South

Carolina. His and his followers’ breach of the peace con

victions were reversed by this Court, holding that their

constitutionally protected rights of free speech, assembly

and petition had been exercised “ in their most pristine and

classic form” (372 U. S. at 235).

Cox had addressed a group of about 2,000 young Negro

students on the sidewalks between the State Capitol and the

courthouse in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. His was a speech of

protest (379 U. S. at 542-43):

[Cox] gave a speech, described by a State’s witness

as follows:

He said that in effect it was a protest against the

illegal arrest of some of their members and that other

people were allowed to picket . . . and he said that

they were not going to commit any violence, that

if anyone spit on them, they would not spit back on

the person that did it.

Cox then said:

All right. It’s lunch time. Let’s go eat. There are

twelve stores we are protesting. A number of these

stores have twenty counters; they accept your money

from nineteen. They won’t accept it from the twenti

eth counter. This is an act of racial discrimination.

18

These stores are open to the public. Yon are members

of the public. We pay taxes to the Federal Govern

ment and you who live here pay taxes to the State.

The Sheriff testified that, in his opinion, constitutional

protection for the speech ceased “ when Cox, concluding his

speech, urged the students to go uptown and sit in at lunch

counters” (379 U. S. at 546), but this Court disagreed:

The Sheriff testified that the sole aspect of the pro

gram to which he objected was ‘ [t]he inflammatory

manner in which he [Cox] addressed that crowd and

told them to go on uptown, go to four places on the

protest list, sit down and if they don’t feed you, sit

there for one hour.’ Yet this part of Cox’s speech obvi

ously did not deprive the demonstration of its protected

character under the Constitution as free speech and

assembly (379 U. S. at 546).

The court below relied upon Feiner v. New York, 340

U. S. 315 (1951) (App. pp. 12a-13a; 187 So. 2d at 859-60;

BA 218), but that case is no more applicable to this than it

was to Edwards and Cox. Both Edwards10 and Cox11 distin

guished Feiner, involving as it did a case where “ the speaker

passes the bounds of argument or persuasion and under

takes incitement to riot” (340 U. S. at 321).12

Analysis of the record reveals that the decision of the

court below affirming petitioners’ convictions conflicts with

10 372 U. S. at 236.

11 379 U. S. at 551.

12 Both Edwards and Cox also distinguished Chaplinsky v. New

Hampshire, 315 TJ. S. 568 (1942), which involved “ fighting words”

on the part of the speaker.

19

Edivards and Cox. Here, petitioners neither intended to

incite their listeners to riot, nor used language creating,

under the circumstances, a clear and present danger of

riot. Like the speakers in Edwards and Cox, petitioners

intended to encourage their listeners to assert their federal

rights. They intended to tell the crowd that if they regis

tered to vote they could eradicate racial discrimination and

segregation in the community. As in Edwards and Cox,

the content of the speeches here was stirring and vigorous,

but not suggestive of violence. Nor were the speeches dis

guised invitations to riot, subtly concocted to exploit an

explosive situation.

Petitioners’ listeners were far fewer in number than in

Edwards and Cox—about 200 Negroes and a few whites—-

most of whom had just witnessed, in a segregated court

room, the trial and conviction of two Negro girls for using

a white-only, municipal park.13 No one in the crowd was

armed and no one gave any indication of committing an act

of violence. More pointedly, following the arrest of peti

tioners, their listeners quietly went home. It is true that

the crowd was “ muttering” and appeared tense and upset.

Such was also the case with a larger number of onlookers

in Cox (379 U. S. at 543, 550). But here, as in Cox, that fact

cannot justify suppression of petitioners’ speech. Nor can

this Court accept at face value the unsupported assertions

of police witnesses that an imminent danger of breach of

the peace existed. This Court must go behind that conclu

sionary testimony and “make an independent examination

of the whole record” (Edwards, supra, 2>12 IT. S. at 235,

and cases cited). To fail to do so would increase the danger

13 There is no evidence in the record that an appreciable number

of persons hostile to petitioners’ cause had been attracted to the

scene.

20

of police officers suppressing speech according to their

“ calculations as to the boiling point of a particular per

son or a particular group, not an appraisal of the nature

of the comments per se” (Ashton v. Kentucky, 384 U. S. 195,

200 (1966) ).14

II.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Review and Reverse

Petitioners’ State Criminal Convictions, Which Deprive

Them of Their Liberty Without Due Process of Law

Because Founded Upon No Evidence of Guilt.

Since in Part I, supra, it was shown that the record re

veals no conduct of petitioners which the State of Missis

sippi has a right to prohibit as a breach of the peace, peti

tioners’ breach of the peace convictions offend the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because there

is a total absence of evidence in the record that petitioners

“ disturb[ed] the public peace by loud or offensive language,

or by conduct either calculated to provoke a breach of the

peace, or by conduct which might reasonably have led to

a breach of the peace” (RA 3; RC 5). Thompson v. Louis

ville, 362 U. S. 199 (1959); Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S.

157 (1961); Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 (1962).

14 Even if the crowd had been disorderly, petitioners would still

maintain that they could not be punished, since they had neither

intended to provoke violence nor used language creating, under the

circumstances, a clear and present danger of violence. At the

very least, they could not be arrested until the police had first

attempted to control or disperse the crowd. Cf. petitioners’ re

fused instructions (RA 12; RC 12). Otherwise, petitioners’ conduct

could be declared “ criminal simply because [their] neighbors have

no self-control and cannot refrain from violence” (Chafee, Free

Speech in the United, States, 151 (1954), quoted in Ashton v.

Kentucky, 384 U. S. 195, 200 (1966)). The court below appears to

have taken a contrary view (App. p. 12a; 187 So. 2d at 859; RA

217-18).

21

Moreover, when petitioners’ breach of the peace convic

tions fall, for reasons tainting petitioners’ arrests, there is

similarly no evidence to support the charge that petitioners,

by attempting to brace their feet and later by going limp,

resisted a police officer “ in executing or attempting to make

a lawful arrest” (EB 8; ED 6).15 16

III.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Review and Reverse

Petitioners’ State Criminal Convictions Under a Statute

Indistinguishable From That Declared Facially Uncon

stitutional by This Court in Cox v. Louisiana.

Petitioners stand convicted of violating Miss. Code Ann.

§2089.5 (Supp. 1964), which punishes any person who dis

turbs the public peace or the peace of others by, inter alia,

“ conduct either calculated to provoke a breach of the peace,

or by conduct which may lead to a breach of the peace.”

Other sorts of disturbances of the peace denounced by the

statute are not implicated by petitioners’ conduct,1'6 and, in

15 The juries which convicted petitioners of resisting- lawful

arrest were correctly charged by the trial judge that petitioners

could not be convicted unless they were found to have committed

a breach of the peace in the arresting officer’s presence (KB 9, 15;

RD 7,12, 13). See Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284, 291-92 (1963);

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U. S. 87 (1965).

16 Section 2089.5 punishes disturbance of the peace by any of the

following acts: (a.) violent or loud or insulting or profane or

indecent or offensive or boisterous conduct or language; (b) intimi

dation; (c) conduct calculated to provoke a breach of the peace or

which may lead to a breach of the peace, or (d) “any other act.”

(a) The police testimony below establishes that petitioners’ con

duct was not violent, insulting, indecent or profane. Their speech

was loud, but there is no showing that it was louder than necessary

in order to reach a large outdoor audience. Nor is there any show

ing that it was offensive or boisterous under any test that could

22

any event, the trial court’s charge permitted their convic

tion on a finding that they violated the quoted language

without more.17 For these reasons the convictions must be

reversed under settled principles if the quoted language

is unconstitutional.18

In Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536, 551 (1965), this Court

held virtually identical language “ unconstitutionally vague

in its overly broad scope.” That decision made clear that

earlier holdings of the Court, Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310

U. S. 296 (1940); Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229

(1963); Henry v. City of Rock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964),

upsetting breach of the peace convictions had rested not

merely on the ground that the defendants’ conduct in each

case was within the scope of free expression protected by

the First and Fourteenth Amendments, but also on the

independent ground that, where invoked to punish acts of

escape condemnation under this Court’s decision in Terminiello v.

Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 (1949).

(b) There is not the slightest suggestion of intimidation in the

record.

(c) The incipient-breach-of-the-peace portions of the statute

are those discussed in the text. Although the opinion of the Mis

sissippi Supreme Court is not altogether clear on the point, it

appears that these were the portions which that court believed

petitioners had violated. See RA 215-216, 218-219.

(d) The provision relating to “ any other act” is so patently

vague and overbroad within the principles of Thornhill v. Ala

bama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940), as not to require further discussion

here.

17 See RA 6; RB 9; EC 7; ED 7.

18 Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359, 367-368 (1931); Wil

liams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 287, 291-293 (1942); Thomas

v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516, 529 (1945). Cf. Shuttlesworth v. Bir

mingham, 382 U. S. 87, 92 (1965).

23

public protest and demonstration, such vague conceptions

as “ calculated to provoke a breach of the peace” failed to

meet those “ [strict] standards of permissible statutory

vagueness” which the Amendments demand when a State

undertakes to regulate speech activity. NAACP v. Button,

371 U. S. 415, 432 (1963), and authorities cited; see also

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479, 486-487 (1965). And

in Ashton v. Kentucky, 384 U. S. 195, 200-201 (1966), the

Court reaffirmed the principle of Cox that these vague in-

cipient-breach-of-the-peace regulations are facially imper

missible.

The court below distinguished Cox on the ground that

“ The factual situation involved in this case is entirely dif

ferent . . . ” (App. p. 13a; 187 So. 2d at 860 ; RA 218-219.)

Petitioners have shown in the preceding sections of this

petition that the “ factual situation” here is not materially

different than that in Cox. But even if it were, the ratio

decidendi below ignores the vital point that Cox did not

turn solely on the facts there presented but upon the con

sidered declaration by this Court that the statutory lan

guage challenged in Cox and substantially identical with

that challenged here was unconstitutional on its face.19

Obviously, then, the decision below is inconsistent with an

applicable decision of this Court within the meaning of

Rule 19(1) (a) governing the granting of certiorari. It is

an important and dangerous decision because it frontally

undercuts the protection of free expression which this Court

19 Perhaps petitioners might be punished even under a facially

unconstitutional statute if their conduct were the sort of “hard

core” activity described in Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479,

491-492 (1965). But on this record it is impossible to so characterize

their conduct.

24

has recently and explicitly announced, and for this reason

alone it imperatively requires review by this 'Court lest

the reception of Cox by the state courts render this Court’s

opinion there a futile exercise. Cf. Henry v. City of Rock

Hill, supra.

IV.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Review and Reverse

Petitioner Cobb’s Conviction for Resisting Arrest Be

cause His Right to Equal Protection of the Laws Was

Violated by the Trial Court’s Refusal to Permit Him to

Show Systematic Exclusion of Negroes From the Petit

Jury Through Prosecutorial Abuse of Peremptory Chal

lenges.

In McLaurin’s appeal, the Mississippi Supreme Court

correctly found that counsel had been permitted to present

such evidence as he had on the prosecutor’s discriminatory

use of peremptories (App. pp. 9a-10a; 187 So. 2d at 858; BA

21, 214). And it properly held that the evidence available

at that time was inadequate to sustain the contention (App.

pp. 9a-10a; 187 So. 2d at 858; BA 214-15). But in affirm

ing Cobb’s resisting-arrest conviction on authority of Mc-

Laurin, that court ignored the circumstance, plainly shown

by the Cobb record as quoted below, that in this case coun

sel had for the first time sought to demonstrate the ac

cumulated experience of the prosecutor’s peremptory prac

tice during the week’s trials and had been refused the op

portunity to do so :

. . . Your motion is well in the record and your mo

tion specifically states what you are seeking to do

and the Court understands that and the record shows

25

that, and if this Court is in error by not permitting you

to show that pattern, then you don’t have to show

that pattern to the Supreme Court at all, the Supreme

Court will reverse it because it didn’t let you do it.

Your record is all right for that purpose (ED 25-26).

Petitioner Cobb contends that under Swain v. Alabama,

380 U. S. 202, 224 (1965), he was entitled to “ show the

prosecutor’s systematic use of peremptory challenges

against Negroes over a period of time.” Assuredly, the

period here was short, but it covered a series of related

cases involving civil rights matters tried by the same

prosecutor in the same court. The question raised is

whether, in view of the difficulty of recording and pre

serving evidence with regard to the volatile practice of

exercising peremptory challenges, the proffer made here

was sufficient within Swain. This Court should grant cer

tiorari to determine that question.

26

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

R. J ess B rown

125% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

la

A P P E N D I X

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

In the

SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

No. 43,429

Charles McL aurin,

City of Greenville.

I nzer, Justice:

Appellant, Charles McLaurin, was convicted on a

charge of disturbance of the public peace in violation of

Mississippi Code Annotated section 2089.5 (Supp. 1964)

in the Municipal Court of the City of Greenville. He ap

pealed to the County Court of Washington County, where

he was tried de novo before a jury. This trial resulted in

a conviction, and he was sentenced to pay a fine of $100

and serve a term of ninety days in the city jail. From this

conviction, he appealed to the circuit court, wherein the

conviction was affirmed. The circuit judge allowed an

appeal to this Court because of the constitutional question

involved.

When this case reached this Court, it was consolidated

with three other cases for the purposes of argument

and submission to the Court. They are Cause No. 43,436,

2a

which is a similar charge against Charles Cobh; Cause No.

43.497, which is a charge against this same appellant,

Charles McLaurin, for resisting arrest; and Cause No.

43.498, which is a similar charge against Charles Cobb.

The cases will be disposed of by separate orders. After

the cases were submitted, it was discovered that the affi

davits upon which these charges were based were not a

part of the record; although they had been so designated

by appellants in their notice of designation of record. The

attention of counsel for the City and appellants was

directed to this defect. The City suggested a diminution

of the record, which suggestion was sustained. The affi

davits are now a part of the records in all four cases.

The appellant’s assignment of errors is as follows:

I. The court below erred in affirming a judgment

of conviction which punishes conduct in the exercise

of the right of free speech guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

II. The court below erred in approving the refusal

of the trial court to give appellant’s instruction that

the jury could not find appellant guilty of breach of

the peace if the police officers had made no reasonable

effort to calm or disperse appellant’s audience.

III. The court below erred in affirming a judgment

of conviction based upon no evidence of guilt.

IV. The court below erred in affirming a judgment

of conviction under a statute so vague and indefinite

as to permit the punishment of the exercise of the right

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

3a

of free speech guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

V. The court below erred in approving the denial

by the trial court of appellant’s motion to quash the

jury panel on the ground of systematic exclusion of

Negroes therefrom through prosecutorial abuse of

peremptory challenges.

The proof on behalf of the City is sufficient to show

that on July 1, 1963, a large crowd of people were

present at the Municipal Court in the City of Greenville

where two Negro girls were being tried on a charge of

disorderly conduct. The courtroom which is in the munic

ipal building seats about 300 people, and it was filled

to capacity. About one-half of the people in the court

room were Negroes, and one-half were white. There was

also a large crowd, consisting of mostly Negroes, on the

outside of the courtroom. Appellant was present at the

trial, but was not in the courtroom. He had gone into

the courtroom prior to the trial and was directed to a seat

by Officer Willie Carson; however, he did not sit where

Officer Carson directed him to sit, and when Carson spoke

to him about it, McLaurin protested that the courtroom

was segregated. He then went out of the courtroom and

protested to the chief of police about the courtroom being

segregated. When he returned to enter the courtroom,

it was filled to capacity, and he was not allowed to enter

again.

The trial resulted in the conviction of the two girls

being tried, and most of the people then departed from

the courtroom. Thereafter, although court was still in

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

4a

session, McLaurin went outside the building and after

talking with some of the people who were present at the

trial, he began to shout in a loud voice, attracting the

attention of the people who were leaving, and many turned

and came back. He backed up on the steps of the building,

and in a loud voice began exhorting the crowd of about 200

people, mostly Negroes, which had gathered around him in

front of the building. The crowd blocked the sidewalk all

the way to the street and the entrances to the build

ing. Officer Carson was on the outside of the building

after the trial, and he testified that the crowd around

McLaurin appeared to be upset over the outcome of the

trial. Officer Carson is a Negro and had been employed

on the police force in the City of Greenville for over

thirteen years prior to the trial. He holds the rank of

detective and has had experience as a military police

man in the armed forces. He said that McLaurin said in

a loud voice, “What you people going to do about this;

this is wrong, the White Caucasian, this law is wrong;

you going to take i t ; you going to let them get away with

it.” The crowd began to mutter and say that it wasn’t

right. It appeared to Officer Carson that the situation

was very tense and anything could happen. It was his

opinion that McLaurin was exciting the crowd in order

to get them to do something about the court’s decision.

Carson made his way through the crowd to where McLaurin

was standing and told him he would have to stop, and that

he could not block the sidewalk. McLaurin continued to

talk, and once again Carson told him to stop. McLaurin

refused, and Carson placed him under arrest. After he

was arrested, McLaurin kept pulling back and talking over

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

5a

Carson’s shoulder to the crowd, saying, “ He’s arresting

me, what are you going to do about it.” In order for Car-

son to get McLaurin into the building and out of the crowd,

it was necessary for him to use all of his strength.

Captain Harvey Tackett, also a member of the City Police

Force, was in front of the police station after the trial.

He said that the first time he saw McLaurin, he was in

the middle of the sidewalk in front of the station, and Mc

Laurin started waving his arms and shouting in a loud

voice to the people that were leaving. Most of the people

immediately came back and gathered around McLaurin who

then “ jumped” upon the steps of the building and contin

ued to shout and holler, asking the people what they were

going to do about what had happened. The crowd started

mumbling and saying something that he could not under

stand, but they appeared to be agreeing with McLaurin. It

was his opinion that the crowd was about to take the situa

tion into their own hands, and he. thought that a breach of

peace was imminent. He had had long experience in police

work, and it was his opinion that McLaurin would have

to be removed or there would likely be a riot. He started

over to where McLaurin was standing, but before he reached

him, Officer Carson reached McLaurin and said something

to him, which Captain Tackett could not hear. McLaurin

kept shouting and hollering and waving his arms, and Car-

son said something else to him; however, McLaurin con

tinued shouting. Then he saw Carson take McLaurin by

the arm and forcibly carry him inside the building. Dur

ing this time McLaurin was still shouting to the crowd.

Chief of Police W. C. Burnley was also present at the

scene and saw and heard what transpired. He had been

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

6a

on the police force in Greenville for seventeen years and

was a graduate of the FBI National Academy. He had re

ceived special training in methods relative to dealing with

crowds. It was his opinion that the situation on the outside

of the building was very tense. He saw McLaurin “ jump”

to the steps of the building and begin to shout and wave

his arms in an emotional manner. He saw the people gather

around him and many that were leaving turned and came

back. He heard McLaurin shout, “ Are you going to take

this; what are you going to do about it,” repeating these

words over and over and other statements that he could

not remember. It was his opinion that the speech of Mc

Laurin was having an emotional effect upon the already

tense crowd, and that any moment a riot or some other

violence could take pace.

Charles Cobb who was a Field Secretary employed by

the Student Non-violent Co-ordinating Committee testified

in behalf of appellant. It was his testimony that he saw

McLaurin when he entered the courtroom and saw Officer

Carson go up to him and say something. McLaurin then

left, and Cobb went out to ascertain why McLaurin had

left. He went with McLaurin to protest to Chief Burnley

relative to segregation in the courtroom, and when they re

turned, they were not allowed to enter the courtroom. When

the trial was over, he left McLaurin and went outside.

When he next saw McLaurin he was standing on the side

walk saying something to the people gathered there. He

estimated that there were about 100 Negroes on the side

walk in front of the municipal building. As McLaurin was

talking he backed up the steps of the building, and although

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

7a

he was only twenty to thirty feet from McLaurin, he said

he could not hear what McLaurin was saying. He saw one

of two police officers say something to McLaurin, who con

tinued talking. The officers then carried McLaurin into

the municipal building. It was his opinion that the crowd

did not appear to be so upset that they would do anything

violent; he thought that they were mostly curious.

Appellant testified in his own behalf and said that he

had been in Greenville off and on for about nine and one-

half months. He was a Field Secretary for the Student

Non-violent Co-ordinating Committee, and had been en

gaged in voter registration work during the time he had

been in Greenville. He was also affiliated with other groups

engaged in civil rights work, including a group of which

the two Negro girls being tried were members. When he

first went into the courtroom, he was directed to take a

seat on the right side of the room, but he saw a vacant

seat on the left side and sat there. He assumed that since

he was directed to the right side where the Negroes were

sitting that the left side was reserved for whites. After he

sat down, Officer Carson told him he could not sit there. He

asked Carson whether the courtroom was segregated, and

Carson told him to come to the back of the room with him.

He followed Carson out of the courtroom, but Carson didn’t

say anything else to him. He and Charles Cobb went to

talk with Chief Burnley about the courtroom being segre

gated, and Burnley told them that they were in the room

once, and turned and walked away from them. He was not

allowed to re-enter the courtroom, and stayed outside dur

ing the trial. After the trial, he then walked outside of the

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

8a

municipal building and began talking with some of the

people who were present at the trial. He moved to the

front of the building, and it appeared to him that the people

coming out were shocked by the conviction of the girls.

He said he started trying to get the attention of the crowd

to tell them about registering and voting so that this kind

of thing could not happen. Officer Carson then came up

and told him that he could not make a speech without a

permit, and when he continued to talk, Carson arrested him

and carried him inside the building. He said, “ I was saying-

different things like, this wouldn’t have happened if Ne

groes were registered to vote, that in Washington County

Negroes are in the majority of the population—50 per cent

of the population is Negro and that they could have used

the park or anyother (sic) thing had they been registered

voters.” He was asked whether the crowd appeared angry

and in a tense and angry mood, and he replied, “I feel that

the crowd was sorta upset as to the out come (sic) of the

trial, but certainly the words that I was using wouldn’t

have caused them to jump—to go in there and try to beat

up the Judge. Negroes know they can’t go beat up the

Judge and be justified, and tear down the building and be

justified, or jump on a policeman in the State of Mississippi

and be justified.” On cross-examination, he admitted that

during the entire time he had been in Greenville he had

not been interfered with in any way in his voter registra

tion work. He said Negroes were allowed to register with

out interference, although some did not pass the test. Most

of his work had been with groups under the voting age, and

he had not been interfered with in any way in this work.

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

9a

We will first address ourselves to the question of whether

the circuit court was in error in affirming the action of the

trial court, in overruling a motion of appellant to quash

the jury panel on the ground of systematic exclusion of

Negroes therefrom through prosecutorial abuse of peremp

tory challenges. Appellant contends that the trial court

refused to allow him to show a pattern or practice of sys

tematic exclusion by peremptory challenges by the City.

This contention is not supported by the record in this case.

The record reflects that the trial judge did at first deny

appellant’s motion to be allowed to show that the City had

peremptorily challenged two Negroes, but immediately

thereafter, she rescinded that ruling and granted appellant’s

motion. Appellant offered no further evidence in support

of the motion to show that the City had followed the prac

tice of systematically excluding Negroes by means of per

emptory challenges. After the jury was selected, appellant

made a motion to quash the panel because of systematic

exclusion of Negroes therefrom because of race and color.

He does not contend that the evidence in the record is suffi

cient to show a prosecutorial abuse of the peremptory chal

lenges, but contends that this case should be remanded to

give the appellant an opportunity to explore this matter

further. There is no merit in this contention. In this con

nection, it is interesting to note that in Cause No. 43,498,

which involves an appeal from McLaurin from a conviction

on a charge of resisting arrest, wherein the City did not

exercise its peremptory challenges to excuse Negroes from

the jury panel, appellant made a motion to quash the panel

because of systematic inclusion of Negroes. This position

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

taken by appellant is without merit and deserves no further

discussion. Swain v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 202, 85 Sup. Ct.

824,13 L. Ed. 2d 759 (1965).

The question of whether appellant’s conduct in this case

is protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States presents the impor

tant question. It is appellant’s contention that his speech

was merely a protest against segregated conditions in

Greenville and the fact that it made the crowd restive and

angry does not support a conviction for a breach of public

peace. In support of this condition, he cites and relies upon

the case of Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, 69 Sup. Ct.

894, 93 L. Ed. 1131 (1949). Terminiello was convicted of a

violation of a city ordinance forbidding any breach of

peace. The decision turned on the construction placed upon

the ordinance by the trial court as reflected by the instruc

tions to the jury. The court held that the construction was

as binding upon it as though the precise words had been

written into the ordinance. The conviction was reversed

because the ordinance as construed by the Illinois court was

at least partly unconstitutional. Appellant contends that

he has been convicted of expressing unpopular views, and

the construction of Mississippi Code Annotated section

2089.5 (Supp. 1964) by the trial court comes within the rule

announced in Terminiello, supra. This directs our atten

tion to the construction placed upon the statute by the

trial court. This is reflected by the instructions to the jury

as requested by the City and by the appellant. The court

instructed the jury that if appellant was arrested for public

protest against racial segregation, then they could not find

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

11a

the defendant guilty. The trial court recognized that sec

tion 2089.5 could not be applied to restrict appellant’s con

stitutional right to protest against racial segregation, and

that this statute could not be used to infringe upon the

constitutional right of appellant or any other person to

speak freely within the framework of the law. This Court

is fully cognizant of our duty to construe our statutes in

such a manner to be sure that they will not infringe upon

the constitutional rights of any person. The statute as con

strued by the trial court is not unconstitutional.

Appellant also urges that section 2089.5 is so vague and

indefinite as to permit the punishment of the exercise of

the right of free speech guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. His

argument is based upon the contention that as applied

here the term “breach of peace” reaches federally pro

tected activities that create unrest in others. The stat

ute as drawn is in broad terms, but it is not unconstitu

tional upon its face. It is true that it could be construed

in such a manner that it would reach federally protected

activities, but we are well aware of the fact that neither

this statute nor any other statute may be constructed

so as to infringe upon the state or federally protected

constitutional rights of appellant or any other person.

This is evidenced by many decisions of this Court, includ

ing our decision in the case relative to the two girls whose

conviction resulted in this action. Bolton v. City of Green

ville, 253 Miss. 656, 178 So. 2d 667 (1965); Bynum v. City

of Greenville, 253 Miss. 667, 178 So. 2d 672 (1965).

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

We find no merit in the assignment of error relative

to the refusal of the trial court to grant appellant an in

struction to the effect that the jury could not find appellant

guilty of a breach of peace if the police officer made no

reasonable effort to calm or disperse the crowd. We do not

understand the law to be that when an officer is faced

with a situation such as Officer Carson was confronted with

in this case, where there was a clear and present danger

of a riot or disturbance of court then in session, that such

officer must, before arresting the person who is creating the

danger, attempt to disperse the crowd. Such an attempt

might well trigger the imminent, danger, and in such cases,

the officer must use his best judgment in determining the

means or manner in which to prevent the threatened dan

ger. The arrest of appellant and the subsequent arrest of

Charles Cobb enabled the officers to control the situation

that otherwise might have created a riot beyond control.

The factual situation in this ease is somewhat similar to

the facts in the ease of Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315,

71 Sup. Ct. 303, 95 L. Ed. 295 (1951), wherein the court

quoted from Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 60 Sup.

Ct. 900, 84 L. Ed. 1213 (1940), where it is said:

The language of Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S.

296 (1940), is appropriate here. ‘The offense known as

breach of the peace embraces a great variety of con

duct destroying or menacing public order and tran

quility. It includes not only violent acts but acts and

words likely to produce violence in others. No one

would have hardihood to suggest that the principle of

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

13a

freedom of speech sanctions incitement to riot or that

religious liberty connotes the privilege to exhort

others to physical attack upon those belonging to an

other sect. When clear and present danger of riot,

disorder, interference with traffic upon the public

streets, or other immediate threat to public safety,

peace, or order, appears, the power of the State to

prevent or punish is obvious.’ 310 U. S. at 308. . . .

(340 U. S. at 320, 71 Sup. Ct. at 306, 95 L. Ed. at 300.)

The factual situation involved in this case is entirely

different from the situation involved in the cases of Cox

v. Louisiana, 379 TJ. S. 85 Sup. Ct. 453, 13 L. Ed. 2d 471

(1965), and Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284, 83 Sup. Ct.

1240, 10 L. Ed. 2d 349 (1963), and these cases do not

control.

Appellant’s contention that there was no evidence of

appellant’s guilt of the charge is without merit. This con

tention is based solely upon the proposition that appellant’s

acts were constitutionally protected, and we hold that they

were not for the reasons heretofore stated.

We have carefully considered all the questions raised by

the appellant in this case, and we are of the opinion that

there was ample evidence from which the jury could find

that appellant was guilty of the offense charged. The con

stitutional rights of the appellant were fully protected,

and this conviction must be affirmed.

Affirmed.

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

A ll justices concur.

14a

Monday, June 13, 1966, Court Sitting

43,429

Judgment of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Breach of Peace Case

Charles McL aurin,

vs.

City of Greenville.

This cause having been submitted at a former day of

this Term on the record herein from the Circuit Court of

Washington County and this Court having sufficiently ex

amined and considered the same and being of the opinion

that there is no error therein doth order and adjudge that

the judgment of said Circuit Court rendered in this cause

on the 16th day of September 1963—a conviction of dis

turbance of the peace violation of Section 2089.5 Missis

sippi Code Annotated—and a sentence to pay a fine of

$100.00 and to serve 90 days in jail be and the same is

hereby affirmed. It is further ordered and adjudged that

the appellant, Charles McLaurin, do pay the costs of this

appeal to be taxed.

Minute Book “BN” Page 597

In the

SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

No. 43,498

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Resisting Arrest Case

Charles McL aurin,

v.

City op Greenville.

Inzer, Justice:

Appellant, Charles McLaurin, was convicted in the

Municipal Court of the City of Greenville on a charge of

resisting arrest in violation of a city ordinance. Upon

appeal to the County Court of Washington County, he was

tried de novo by a jury and this trial resulted in a convic

tion, and he was sentenced to pay a fine of $100 and serve

ninety days in the city jail. He appealed to the circuit

court, wherein the conviction was affirmed. The circuit

judge allowed an appeal to this Court because of the con

stitutional question involved.

Appellant does not contend that he did not resist arrest,

but does contend that his arrest was unlawful. He urges

that he was arrested for exercising his constitutional right

of free speech guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States. We held in.

Charles McLaurin v. City of Greenville, Cause No. 43,429,

this day decided, that his arrest was not unlawful and

was not in violation of his constitutional right.

We also settled the other question raised on this appeal

in that decision; therefore, this cause must be affirmed.

Affirmed.

A ll justices concur.

16a

Monday, June 13, 1966 Court Sitting

No. 43,498

Judgment of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

McLaurin Resisting Arrest Case

Charles McLaurin,

vs.

City of Greenville.

This cause having been submitted at a former day of this

Term on the record herein from the Circuit Court of Wash

ington County and this Court having sufficiently examined

and considered the same and being of the opinion that there

is no error therein doth order and adjudge that the judg

ment of said Circuit Court rendered in this cause on the

24th day of July 1964— a conviction of resisting arrest

and a sentence to pay a fine of $100.00 and to serve a

term of 90 days in jail—be and the same is hereby affirmed.

It is further ordered and adjudged that the appellant,

Charles McLaurin do pay the costs of this appeal to be

taxed.

Minute Book “BN” Page 598

17a

In the

SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

No. 43,436

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

Cobb Breach of Peace Case

Charles Cobb,

v*

City of Greenville.

Inzer, Justice:

This case is controlled by our decision in the case of

MeLaurin v. City of Greenville, Cause No. 43,429, this day

decided. For the reasons stated therein, this case must be

affirmed.

Affirmed.

A ll justices concur.

18a

Monday, June 13, 1966, Court Sitting

43,436

Judgment of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

Cobb Breach of Peace Case

Charles E arl Cobb,

vs.

C ity op Greenville.

This cause having been submitted at a former day of

this Term on the record herein from the Circuit Court of

Washington County and this Court having sufficiently ex

amined and considered the same and being of the opinion

that there is no error therein doth order and adjudge that

the judgment of said Circuit Court rendered in this cause

on the 18th day of September 1963—a conviction of breach

of the peace and a sentence to pay a fine of $100.00 and to

serve a term of 90 days in jail—be and the same is hereby

affirmed. It is further ordered and adjudged that the

appellant, Charles Earl Cobb, do pay the costs of this

appeal to be taxed.

Minute Book “BN” Page 398

19a

I n the

SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

No. 43,497

Charles Cobb,

y.

City of Greenville.

Opinion of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

Cobb Resisting Arrest Case

Inzer, Justice:

This case is controlled by onr decisions in the cases of

Charles McLaurin v. City of Greenville, Cause Nos. 43,429

and 43,498. For the reasons stated therein, this case is

affirmed.

Affirmed.

A ll justices concur.

20a

Monday, June 13th, 1966, Court Sitting

43,497

Charles E arl Cobb,

Judgment of Supreme Court of Mississippi in

Cobb Resisting Arrest Case

vs.

City of Greenville.

This cause having been submitted at a former day of

this Term on the record herein from the Circuit Court of

Washington County and this Court having sufficiently ex

amined and considered the same and being of the opinion

that there is no error therein doth order and adjudge

that the judgment of said Circuit Court rendered in this

cause on the 24th day of July 1964—a conviction of re

sisting arrest and a sentence to pay a fine of $100.00 and

to serve a term of 90 days in jail—be and the same is

hereby affirmed. It is further ordered and adjudged that

the appellant, Charles Earl Cobb, do pay the costs of this

appeal to be taxed.

Minute Book “BN” Page 598

38