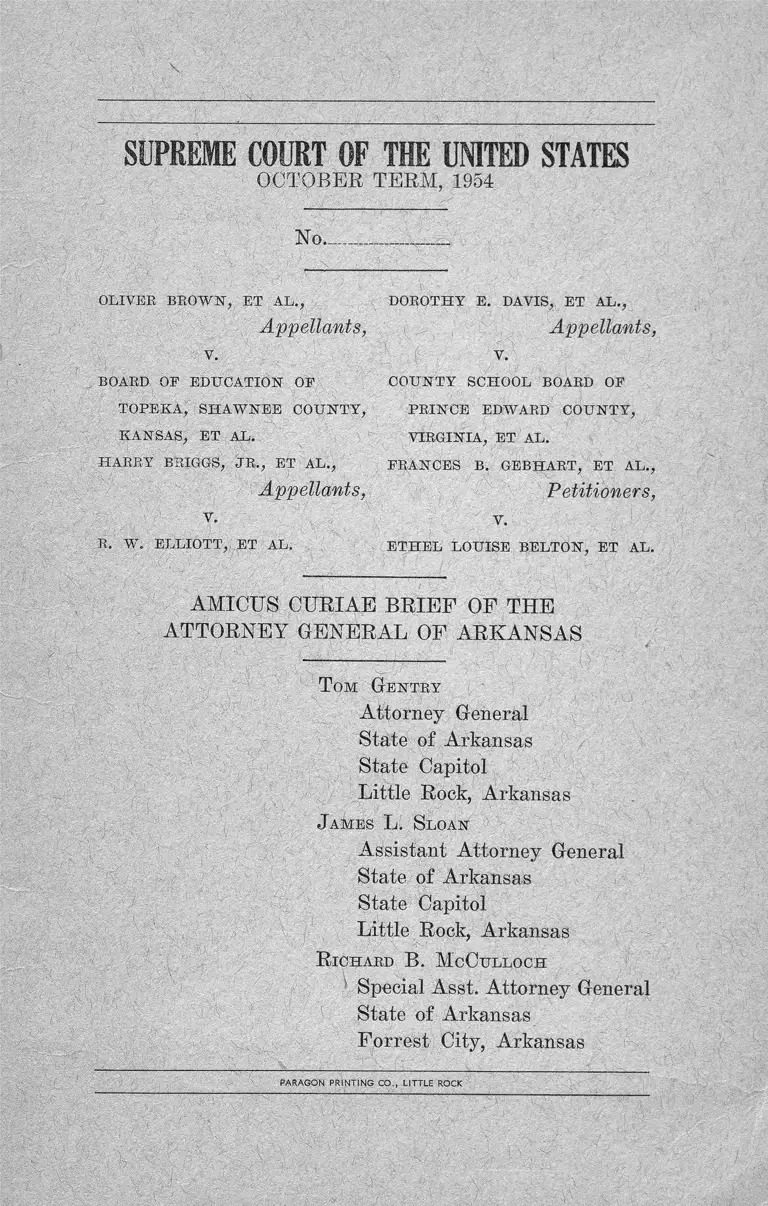

Brown v. Board of Education Amicus Curiae Brief of the Attorney General of Arkansas

Public Court Documents

November 15, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Amicus Curiae Brief of the Attorney General of Arkansas, 1954. 03d4ddd5-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5d0e7727-9f6b-4cfe-b1dc-9b0916e18bfb/brown-v-board-of-education-amicus-curiae-brief-of-the-attorney-general-of-arkansas. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1954

N o .—.

OLIVER -B R O W N , ET A L ., D O RO TH Y E. DAVIS, E T A L .,

Appellants, Appellants,

V. V.

BOARD OF ED U CATIO N OF C O U N T Y SCH OOL BOARD OF

T O P E K A , SH A W N E E C O U N T Y , P R IN C E EDW ARD C O U N T Y ,

K A N SA S, E T A L. V IR G IN IA , E T A L.

H A R R Y BRIGGS, J R ., E T A L ., FR AN C E S B . G E B H A R T , ET A L .,

Appellants, Petitioners,

V. V.

R . W . E L LIO T T ,, E T A L. E T H E L LO U ISE B E L T O N , ET A L.

AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ARKANSAS

T om G entry

Attorney General

State of Arkansas

State Capitol

Little Rock, Arkansas

J am es Li S loan

Assistant Attorney General

State of Arkansas

State Capitol

Little Rock, Arkansas

R ichard B. M cCu lloch

Special Asst, Attorney General

State of Arkansas

Forrest City, Arkansas

PARAGON PRINTING CO., LITTLE ROCK

IN D E X

Page

Preliminary Statement --------------- ------------------------------------- 1

Arkansas Constitutional and

Statutory Provisions ________________________________ 3

Factual Background_____________________________________ 5

Argument:

1. This Court Should Not Order

Immediate Integration ____ 7

2. Cases Should Be Remanded to

Permit Gradual Integration ________________________ 10

3. Congressional Action for

Integration ________________________________________ 13

21Conclusion

INDEX—(Continued)

Cases Cited

Page

Brown et al v. Board of Education of

Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, et al,

347 U. S. 483 _______________________________________ _ 1

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ___ _________________ 14, 16, 17

Colegrove v. Green, 328 U. S. 549 ________________________ 20

Coleman v. Miller, 307 U. S. 433 _________________________ 19

Collins v. Hardyman, 341 U. S. 651 ______________________ 14

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321______________________ 10, 11

International Salt Co. v. United States,

332 U. S. 392 _______ ________________________________ 10

Meredith v. City of Winter Haven,

320 U. S. 228 __________- - - _______________________ 10

Minersville School Dist. v. Gobitis,

310 U. S. 586 _______________________________________ - 18

McCollum v. Board of Education of School

Dist. No. 71, 333 U. S. 203 ____________________________ 17

Parker v. Brown, 317 U. S. 341 __________________________ 20

INDEX—(Continued)

Page

Pitts v. Board of Trustees of DeWitt Special

School Dist. No. 1, 84 F. Supp. 975 ________________11, 18

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 -------------------- --------------- 11, 15

Steward Mach. Co. v. Davis,

301 U. S. 549 _____________________ __________ ________ 20

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461_________ ___ .......................-... 13

United States v. Fisher, 6 U. S. 358 -------------------- --------------- 17

United States v. Gilman, 347 U. S. 507 ----------------- ...------------ 20

Arkansas Constitution and Statutes

Constitution of Arkansas (1874),

Article 14, Section 1 ___ ______________ ______ ___ ____ ~ 3

Constitution of Arkansas (1874),

Article 14, Section 4 — -------- ---- ------------------------------- 3

Act 52, Arkansas Acts of 1868 .—.................. ................ ........ 4

Act 130, Arkansas Acts of 1873, Section 108 ______________ 4

Appendix "A "

Arkansas School Enrollment

1933-1954 Session With Receipts and Disbursements__ 25

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1954

No.

OLIVER B R O W N , E T A L .,

Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF E D U C A TIO N OF

T O P E K A , SH A W N E E C O U N T Y ,

K A N SA S, ET AL.

H A R R Y BRIGGS, J R ., ET A L .,

Appellants,

v.

R. W . E L L IO T T , E T A L.

DOROTH Y E. DAVIS, E T A L .,

Appellants,

v.

C O U N T Y SCH OOL BOARD OF

P R IN C E EDW ARD C O U N T Y ,

V IR G IN IA , ET AL.

FRAN CES B. G E B H A R T, E T A L .,

Petitioners,

v.

E T H E L LOU ISE B E L T O N , ET A L.

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This brief is filed by the Attorney General of the State

of Arkansas as amicus curiae at the invitation of this

Court in the four cases shown in the caption. For brevity

and convenience, the four cases are referred to collectively

as “ the Brown Case” . Brown v. Board of Education of

Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, 347 II. S. 483.

In the Brown Case, the Chief Justice, speaking for the

unanimous Court, stated the issue presented to the Court

in the four cases as follows, 347 U. S. at 493:

“ Does segregation of children in public schools

solely on the basis of race, even though the physical

facilities and other ‘ tangible’ factors may be equal,

deprive the children of the minority group of equal

educational opportunities f ”

2

Tlie Court decided that issue in the following language,

347 IT. S. at 495 :

“ We conclude that in the field of public educa

tion the doctrine of ‘ separate but equal’ has no place.

Separate educational facilities are inherently un

equal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and

others similarly situated for whom the actions have

been brought are, by reason of the segregation com

plained of, deprived of the equal protection of the

laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Let it be said at the outset that nothing contained in

this brief is intended to bring into question the correctness

of the ruling of this Court or its reasons for reaching that

conclusion.

The full force and effect of the decision in the Brown

Case was recognized by a “ policy statement” issued by the

State Board of Education of Arkansas following a meeting

of the Board on June 14, 1954. The policy statement of

the Board is as follows:

“ Under our present law the State Board of

Education acts only in an advisory capacity to local

school boards. The local board itself is the govern

ing body of the school district and its decisions are

final. Therefore, decisions must be made by the

local school board, but within the limitations and

restrictions provided by law. Our present state law

provides for segregation in the public schools and

any decision by a local board providing for integra

tion of the races is premature, as the Supreme Court

in its opinion stated that further arguments would

be heard and a decree entered. We do not know

when the decree will be entered or what it will pro

vide. In the meantime, members of both races at

the community level should continue as they have

in the past in working cooperatively and effectively

in a friendly effort to achieve better and substan

tially equal schools for all children, without regard

to race.

3

“ It is important to keep in mind that policy

decisions are made by local school boards. The

public school system in America calls for local con

trol of schools and the state functions in the area of

leadership only in such vital statewide matters as

the one involving segregation of the races.”

The General Assembly of Arkansas (the constitutional

legislative branch of Arkansas’ government) has not been

in session since March of 1953 and will not convene in reg

ular session until January of 1955. Without anticipating

what action, if any, the General Assembly of Arkansas will

take in its 1955 session, it is probably safe to say at this

time that some further words of advice and direction from

this Court will go a long way toward charting the course

of future action or inaction by the Arkansas General As

sembly. One of the purposes of this brief is to solicit most

earnestly from this Court such words of clarification and

advice as to the course to be pursued by the people of Ar

kansas in carrying out the final mandate of the Court as

may be proper.

P E R T IN E N T A R K A N SAS C O N ST IT U T IO N A L

AN D STATU TO R Y PROVISIONS

Ark. Const. (1874) Art. 14, §1, provides:

“ Intelligence and virtue being the safeguards

of liberty and the bulwark of a free and good gov

ernment, the State shall ever maintain a general,

suitable and efficient system of free schools whereby

all persons in the State between the ages of six and

twenty-one years may receive gratuitous instruc

tion.”

Ark. Const. (1874) Art. 14, §4, provides:

“ The supervision of public schools and the

execution of the laws regulating the same shall be

vested in and confided to such officers as may be

provided for by the General Assembly.”

4

The first general law providing for the separation of

white and negro children in the public schools of Arkansas

was enacted on July 23, 1868 —- the year of adoption of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion. The act provided that school boards in Arkansas

shall “ make the necessary provisions for establishing sep

arate schools for white and colored children and youths

. . . Act 52, Ark. Acts of 1868.

In 1873 the Arkansas school law of 1868 was re-enacted

and Act 130, Ark. Acts of 1873, §108, provided for “ estab

lishing separate schools for white and colored children and

youths.” According to a contemporary newspaper, there

were twenty negro members in the 1873 session of the

Legislature and it was reported that “ that one-fifth part

is a complete master of the two houses, as if the number

that composed the group were three times as great. ’ ’ Edi

torial, “ The Colored Legislators,” Arkansas Gazette, Feb

ruary 1, 1873, p. 2.

It is also interesting to note that on January 6, 1873

(the year during which the Arkansas school laws were be

ing formulated), J. C. Corbin became State Superintendent

of Public Instruction for Arkansas. He was a negro edu

cator who came to Arkansas during the War between the

States. See Weeks, “ School History of Arkansas.” (H.

S. Bureau of Education Bui. No. 27, 1912) pp. 59, 117.

The only statutory law in Arkansas today on the sep

aration of white and negro children in the Arkansas public

school system provides:

“ The board of school directors of each district

in the State shall be charged with the following

powers and perform the following duties . . . (c)

Establish separate schools for white and colored

persons.” Ark. Stats. (1947) §80-509.

5

The existing school segregation law in Arkansas, there

fore, apparently had its origin at a time when the negroes

in Arkansas greatly influenced, if not dominated, legisla

tive action on the school question.

F A C T U A L BACKGROUND

Attached hereto as Appendix “ A ” appears a tabula

tion which shows pertinent information as to the various

school districts of Arkansas. The purpose of this tabula

tion is to demonstrate the proposition that the wide variety

of circumstances which exist in the various counties of

Arkansas requires a wide variety of remedies and plans in

bringing about the ultimate result demanded by the decision

of this Court, that is, the abolition of the dual school system

in Arkansas.

There are 75 counties in Arkansas. The tabulation

shows there are 422 separate school districts in the State

or an average of about five separate districts for each

county. Each school district has its separate board of

directors which is the immediate governing authority of

the district. The members of the board are elected by

the qualified electors of the district and they are directly

responsible to the people for their actions.

It is of interest to note that there are 14 counties out

of the total 75 counties which had no negroes enrolled in

the public schools of the county. Ten of the counties

without negro population are located in the north and

northwest (mountain) section of the State. Two of the

non-negro counties (Polk and Scott) are in the south

western section of the state. The remaining two non

negro counties (Clay and Greene) are contiguous to Mis

sissippi County to the east which had a negro enrollment

of 4,789 or about 20% of the total enrollment for Mississippi

County.

6

By way of contrast, it will be seen from Appendix

“ A ” that in six counties in Arkansas the negro enrollment

exceeded the white enrollment. Five of these predomi

nately negro counties (Lee, St. Francis, Crittenden, Chicot

and Phillips) are in the eastern section of the State and

border the Mississippi River. The other predominately

negro county (Lincoln) is in South-central Arkansas.

The tabulation showTs that the negro enrollment for

the State was about 23% of the total enrollment of the

State.

As further evidence of the variety of conditions and

circumstances in Arkansas, it should be noted that two

districts in Arkansas have already integrated the white

and negro children in the schools.

The Charleston School District in Western Arkansas

(Franklin County) has integrated pupils during the 1954-

1955 session from the first grade through the twelfth grade.

The Fayetteville School District in Northwest Arkansas

(Washington County) has an enrollment of 3,096 white

pupils and 64 negro pupils. This district has integrated

the negro and white pupils at the high school level. Negro

children in the Fayetteville School District attend a seg

regated school from the first grade through the ninth

grade. For the 1954-1955 session, 11 negro high school

pupils are attending the same high school with approxi

mately 500 white children.

It is a matter of general information that integration

has been accomplished so far in the Charleston and Fay

etteville School Districts without any unusual incidents.

However, from a comparison of the factual situations of

the Charleston and Fayetteville School Districts with, for

example, districts in St. Francis and Phillips Counties,

it would certainly seem to follow as a matter of necessity

that the process of integration must be applied as the cir

cumstances in each district may require.

7

ARGUMENT

1. This Court should not order “ forthwith integra

tion” in the public schools.

2. This Court should enter a decree in the pending

cases which will permit gradual adjustments.

3. The Court should leave the problem of integra

tion of the races in public schools to Congress for appro

priate legislation.

P oint 1

This Court Should Not Order Immediate Integration

This Court in its opinion in the Brotvn Case clearly

recognized that the procedure for integration of the races

in the public schools “ presents probllems of considerable

complexity.” Thus the Court has indicated that it is not

unmindful of the possibility of widespread hostility in at

least some school districts if immediate integration of the

races in the public schools is required by this Court. This

hostility is commonly known to exist in varying degrees

in a majority of the school districts of Arkansas although

there have been, so far as is known, no overt acts by any

particular group or groups indicating open defiance of the

law as declared by this Court.

But even unwilling or hostile compliance can, and

probably would, have a most undesirable effect upon the

whole system of public education in Arkansas. It will be

conceded, presumably, that the bulk of the financial sup

port for the public school system of Arkansas flows from

the white population. This fact will continue to be true for

many years to come unless a large portion of those per

sons who now pay taxes in support of public schools man

age, by some means not now forseeable, to withdraw their

8

support as a result of legislative enactments of some kind

or other.

Without the leadership of those who carry the large

portion of the burden of supporting the school system, the

system as a whole is bound to pass through a period of

deterioration which might last for many, many years. If

the public school system is permitted to deteriorate, it

necessarily follows that both the negro children and the

white children will be the unfortunate victims. The negro

children in all probability will suffer to a greater degree

than the white children in such circumstances.

The Arkansas public school system today ranks far

down the list in many respects in comparison with the

systems of other states. There is a long way to go before

Arkansans can point with pride to their school system as a

whole. But no well-informed person will seriously contend

that Arkansas has not made measurable progress during

the past few years. Every well-informed person in Ar

kansas agrees with this Court when it said that “ today,

education is perhaps the most important function of state

and local governments” and education “ is the very foun

dation of good citizenship.” Brown Case, supra.

The executive, legislative and judicial branches of the

State government have for years pointed up the school

problem as the most important problem confronting the

people of this State. It is well within the realm of possi

bility that any decree of this Court at this time which

would have the legal effect of ordering immediate integra

tion of the races in all the school districts of Arkansas

would disrupt the financing, management and control of

the school system for many years.

A recognized authority on the sociological aspects of

school segregation has said:

9

“ Finally, there is the hard fact that integra

tion in a meaningful sense cannot be achieved by the

mere physical presence of children of two races in

a single classroom. No public school is isolated

from the community that supports it, and if the

very composition of its classes is subject to deep-

seated and sustained public disapproval it is hardly

likely to foster the spirit of united effort essential

to learning. Even those who are dedicated to the

proposition that the common good demands the

end of segregation in education cannot be unaware

that if the transition produces martyrs they will be

the young children who must bear the brunt of

spiritual conflict.” Ashmore, “ The Negro and the

Public Schools,” (Chapel Hill 1954) p. 135.

It would unduly extend this discussion to take up the

problems of grade requirements, transportation problems,

revision of school area distribution and the many other

complex management problems which will ultimately have

to be solved in bringing about complete integration in Ar

kansas. This Court has already indicated by the opinion

in the Brown Case and by the study which the Court lias

obviously given to these cases that it is fully aware of the

complexity of the problem. This Court has not asked for

a statement of the problem, but rather for a solution.

What has been said is, of course, addressed to the

discretion of this Court in the exercise of its equity pow

ers in the four cases now pending before it. It is believed

that this complex problem can be solved most effectively

and most satisfactorily in the interest of both the negro

children and the white children by a gradual, rather than

an immediate, adjustment or transition from segregation

to integration of the races in the public schools.

There are, of course, many decisions of this Court

pointing out the peculiar nature of equity practice. In

the interest of brevity, it is appropriate to point to the

10

opinion of Mr. Justice Douglas in Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321

U. S. 321, 329, where the Court said:

‘ ‘We are dealing here with the requirements

of equity practice with a background of several

hundred years of history. Only the other day we

stated that ‘ An appeal to the equity .jurisdiction

conferred on federal district courts is an appeal to

the sound discretion which guides the determina

tion of courts of equity’,- Meredith v. Winter Haven,

320 U. S. 228, 235. The historic injunctive process

was designed to deter, not to punish. The essence

of equity jurisdiction has been the power of the

Chancellor to do equity and to mould each decree of

the necessities of the particular case. Flexibility

rather than rigidity has distinguished it. The quali

ties of mercy and practicality have made equity the

instrument for nice adjustment and reconciliation

between public interest and private needs as well

as between competing private claims.”

This Court also held in International Salt Co. v. United

States, 332 U. S. 392, that district courts are invested with

large discretion in modeling their judgments to fit the

exigencies of the particular case, and the framing of de

crees should take place in the district rather than appel

late courts.

P oint 2

The Court Should Enter a Decree in the Pending

Cases Which Will Permit Gradual Adjustments

The pending cases have been designated as class actions

by the Court. The principal matter about which the peo

ple of Arkansas are concerned is the binding effect of the

impending decrees on prospective or pending litigation of

similar nature in the federal courts of Arkansas.

It is believed that the decree of this Court in the Briggs

Case, for example, would not have the effect of an adjudi

11

cation of pending or prospective similar actions in the

federal courts of Arkansas. That decree would be a pre

cedent to be followed by the federal courts in Arkansas

only to the extent that the Briggs decree would permit the

federal court in Arkansas in equity to follow the proced

ural scheme provided for in the Briggs decree.

The ultimate solution of the complex problem of tran

sition is undoubtedly one which calls for ‘ ‘ flexibility rather

than rigidity.” Hecht Co. v. Bowles, supra.

In framing its decrees in the pending cases, it is

deemed proper for this Court to consider the opinion of

Judge Harry J. Lemley in Pitts v. Board of Trustees of

DeWitt Special School District No. 1, 84 F. Supp. 975

(E. I). Ark.). That case asserted the rights of negro

plaintiffs to equal public school facilities under the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The

Court followed the “ separate but equal doctrine” of

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, and held that the negro

children were entitled under the Amendment to school

facilities substantially equal to the school facilities af

forded white children. Judge Lemley was there con

fronted, as the Court is here, with the terms and the scope

of the decree to be entered under his findings of fact and

conclusions of law. In solving this perplexing problem,

Judge Lemley said, 84 F. Supp. at 983:

“ The instant suit is one in equity, and the bill

is addressed to the court sitting as a court of equity.

Hence the court has a wide discretion in determin

ing what relief is proper and prescribing the time

within which such relief must become effective.

The case at bar is not the only one of this nature

upon the court’s docket and, in connection with our

discussions and holdings herein, it should be borne

in mind that each of these cases stands on its own

peculiar facts; relief which might be proper in one

12

ease miglit not be sufficient in another, and the

length of time allowed to a district within which to

bring about an equalization of educational facili

ties which might be reasonable in one case could be

unreasonable in another.”

In the same opinion, Judge Lemley further said, 84

F. Supp. at 988:

“ We are not going to attempt to say what a

‘ reasonable time’ in this case will be; that is a mat

ter properly left, for the time being, to the good

faith and discretion of the Board. If' the Board is

dilatory, the plaintiffs are not without their rem

edy in the Courts.”

The problem before Judge Lemley was, in effect, the

same as now confronts this Court in the framing of its

decrees. Judge Lemley decided that the negro children

were entitled to separate but equal facilities. This Court

has decided that the negro children in the instant cases are

entitled to identical facilities, subject only to classification

not based on race. Judge Lemley was confronted with a

transition from unequal to equal facilities. This Court is

confronted with a transition from separate to identical

facilities.

It seems obvious that Judge Lemley adopted the logi

cal and equitable solution of the problem before him. It

appears also that this Court could find no better solution

of its problem in the instant cases than remanding the four

cases to the courts of first instance for adoption, in sub

stance, of the language of Judge Lemley in the Pitts Case,

supra.

It is contended, therefore, that the Court should enter

a decree in each of the pending cases which will read sub

stantially as follows:

13

“ The ease is remanded to the court of first in

stance with directions to enter such orders and de

crees as are necessary and proper and not incon

sistent with the opinion of this Court in this case.

In exercising its jurisdiction upon remand, the court

of first instance is left free to hold hearings, through

a Special Master of the court if deemed necessary

or appropriate, to consider and determine what pro

visions are essential, proper and appropriate to af

ford appellants and those similarly situated full pro

tection against segregation of negro children in the

public schools solely on the basis of race in violation

of their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution.” Terry v. Adams,

345 U.S. 461, 470.

P oint 3

The Court Should Leave the Problem of Integration

of the Races in Public Schools to Congress for

Appropriate Legislation

Even if the Court remands the pending cases with di

rections as suggested, there still remains the uncertainty

of the immediate effect which those decrees may have on

prospective cases in the federal courts in Arkansas. The

Court must of necessity make some disposition of the

pending cases by way of appropriate decrees. In this con

nection it is most respectfully urged that the Court take

some action by way of a supplemental opinion, in addition

to the specific decrees, which will have the effect of pre

cluding what might well turn out to be a flood of cases in

the federal courts of Arkansas and other so-called “ seg

regated states.”

The point here is that this Court can and should deal

with the problem by way of supplemental opinion in such

a way that the whole problem of solving the method of

integration should fall squarely where the Fourteenth

14

Amendment says it should fall; that is, on Congress for

appropriate enactment.

In its opinion of May 17, this Court has definitely

and finally decided that the separation of the races in

public schools pursuant to state laws on a basis of race vio

lates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The law having thus been interpreted and

declared by this Court for the first time, it now becomes

the function and the constitutional duty of Congress to

exercise the power granted by Section 5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment is as follows:

“ The congress shall have power to enforce, by

appropriate legislation, the provisions of this

article.”

It might be well to mention at the outset that it is fully

recognized that “ it is not for this Court to compete with

Congress or attempt to replace it as the Nation’s law-

making body,” Collins v. Hardyman, 341 IT. S. 651, 663,

and that “ the judiciary may not, with safety to our insti

tutions, enter the domain of legislative discretion and dic

tate the means which Congress shall employ in the exer

cise of its granted power. That would be sheer usurpation

of the functions of a coordinate department, which, if

often repeated, and permanently acquiesced in, would work

a radical change in our system of government.” Mr.

Justice Harlan dissenting in The Civil Rights Cases, 109

U. S. 3, 51.

Nevertheless, it would certainly not be entirely with

out precedent for this Court to point out to Congress, as

urged here, the necessity for “ appropriate legislation” ;

especially in view of the known fact that the prolonged in

action by Congress has now resulted in a condition which

has some aspects at least of a national emergency.

15

As a matter of pertinent history, it is very significant

that the legislative records of Congress in promulgating

the Fourteenth Amendment and of state legislatures in

ratifying it have very little to say about racial segregation

in public schools. It is, however, a matter of record that

Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts appears to have

strenuously but unsuccessfully advocated implementing

legislation under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment

which would have been a specific and far-reaching pro

scription of racial segregation in the public schools. Cong.

Globe, 42 Cong., 2d Sess. 383-84 (1872).

By way of contrast, it is quite obvious from a reading

of the Court’s opinion in the Brown Case that, in arriving

at its decision, the Court took full cognizance of contem

porary conditions in the field of public education as com

pared with conditions existing at the time of and for many

years subsequent to 1868. This Court said, 347 U. S. 492:

“ In approaching this problem, we cannot turn

the clock back to 1868 when the Amendment was

adopted, or even to 1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson

was written. We must consider public education in

the light of its full development and its present

place in American life throughout the Nation . . . .

“ Today, education is perhaps the most import

ant function of state and local governments . . . .

In these days, it is doubtful that any child may rea

sonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied

the opportunity of education.”

The Court having pointed out so forcibly the evolving

concept of the Fourteenth Amendment, it would seem to

follow as a necessary conclusion that the Court should now

(by way of an additional opinion) not only nudge but

even exhort Congress to enact appropriate legislation un

der the power of Section 5 of the Amendment.

16

This Court could with complete propriety point out

to Congress that legislative action is a necessity and that

such necessity is a result of extending’ inaction by Congress.

If Congress responds to the urgent invitation of the Court

(and there are many reasons for believing that it will),

then it will be performing the mandate of the people which

is incorporated in Section 5 of the Amendment.

This Court in The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 11,

said that, under Section 5 of the Amendment, Congress

is empowered

“ To adopt appropriate legislation for correct

ing the effects of such prohibited State laws and

State acts, and thus to render them effectually null,

void, and innocuous.”

And in the same cases this Court said, 109 IT. S. 14:

“ It is not necessary for us to state, if we could,

what legislation would be proper for Congress to

adopt. It is sufficient for us to examine whether

the law in question is of that character.”

In his very forceful dissenting opinion in The Civil

Rights Cases, Mr. Justice Harlan said,

“ The legislation which Congress may enact, in

execution of its power to enforce the provision of

the amendment, is such as may be appropriate to

protect the right granted. The word appropriate

was undoubtedly used with reference to its meaning,

as established by repeated decisions of this court.

Under given circumstances, that which the court

characterizes as corrective legislation might be

deemed by Congress appropriate and entirely suffi

cient. Under other circumstances, primary direct

legislation may be required. But it is for Congress,

not the judiciary, to say that legislation is appro

priate—that is—best adapted to the end to be at

tained.”

17

The conclusion to be drawn from the decision in The

Civil Bights Cases is that the “ appropriate legislation”

contemplated by Section 5 is co-extensive with and just as

important a part of the Fourteenth Amendment as is Sec

tion 1 which declares the rights of all persons to equal pro

tection under the laws. Therefore, whatever action Con

gress sees fit to take in the light of this Court’s decision

would rest upon the judgment of Congress; provided, of

course, that such legislation is directed against state ac

tion. As Mr. Chief Justice Marshall said in United States

v. Fisher, 6 U.S. 358:

“ Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the

scope of the Constitution, and all means which are

appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end,

which are not prohibited, but consistent with the

letter and spirit of the Constitution, are constitu

tional.”

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, concurring in McCollum v.

Board of Education, 333 U. S. 203, 212, said that the case

“ . . . demonstrates anew that the mere formulation

of a relevant Constitutional principle is the begin

ning of the solution of a problem, not its answer.”

And in the same case, Mr. Justice Jackson, concur

ring, said, 33 U.S. at 237: ‘ It is idle to pretend that

said, 333 U. S. at 237: ‘ It is idle to pretend that

this task is one for which we can find in the Consti

tution one word to help us as judges to decide where

the secular ends and the sectarian begins in educa

tion. Nor can we find guidance in any other legal

source. It is a matter on which we can find no law

but our own prepossessions. If with no surer legal

guidance we are to take up and decide every varia

tion of this controversy, raised by persons not sub

ject to penalty or tax but who are dissatisfied with

the way schools are dealing with the problem, we

are likely . . . to make the legal “ wall of separa

tion between church and state” as winding as the

18

famous serpentine wall designed by Mr. Jefferson

for the University he founded.’ ”

This Court in the Brown Case arrived merely at the

“ formulation of a relevant Constitutional principle.” This

Court should invoke immediate action by Congress to de

clare and solve the variations of the controversy which are

prevalent in the so-called “ segregated states” — parti

cularly in Arkansas.

Again it is appropriate to refer to the opinion of Judge

Lemley in his “ separate but equal” decision, Pitts v. Board

of Trustees, where he said, 84 F. Supp. at 988:

“ In the last analysis, this case and others like

it present problems which are more than judicial

and which involve elements of public finance, school

administration, politics and sociology . . . . The

federal courts are not school boards; they are not

prepared to take over the administration of the pub

lic schools of the several states; nor can they place

themselves in the position of censors over the ad

ministration of the schools by the duly appointed

and qualified officials thereof, to whose judgment

and good faith much must be left.” See also Min-

ersville School Dist. v. Gohitis, 310 U. S. 586.

In the Pitts Case and other “ equal facilities” cases

like it, the Court had before it, insofar as enforcement is

concerned, a much less complicated problem than the pres

ent problem of integration of races. The magnitude and

complexity of the integration problem dictates a legislative

solution.

In the enactment of appropriate legislation under

Section 5 of the Amendment, Congress could, and probably

would, recognize the necessity of allowing school officials

wide latitude of administrative discretion under the su

pervision of a federal agency which would guarantee ulti

mate integration. Congress could make adequate provi

19

sions for variations in such matters as geographical peculi

arities, increasing or decreasing enrollment in particular

districts, ratios of enrollment as between white and negro

children, population shifts and any other factors which

Congress might consider to be relevant.

Under Section 5, Congress would undoubtedly have

power to fix a definite future date for complete integra

tion in the several districts which have heretofore operated

under the segregated system; or Congress might provide

that integration must be completed in all districts within

a reasonable time — such reasonable time to be deter

mined in the manner prescribed by Congress.

As said by Mr. Chief Justice Stone in Coleman v.

Miller, 307 U. S. 433, 453,

“ The question of a reasonable time in many

cases would involve, as in this case it does involve,

an appraisal of a great variety of relevant condi

tions, political, social and economic, which can hardly

be said to be within the appropriate range of evi

dence receivable in a court of justice and as to which

it would be an extravagant extension of judicial au

thority to assert judicial notice as the basis of de

ciding a controversy with respect to the validity

of an amendment actually ratified. On the other

hand, these conditions are appropriate for the con

sideration of the political departments of the Gov

ernment. The questions they involve are essentially

political and not justiciable. They can be decided

by Congress with the full knowledge and apprecia

tion ascribed to the national legislature of the po

litical, social and economic conditions which have

prevailed during the period since the submission of

the amendment.”

It is submitted that so long as Congress confines its

“ corrective” legislation to state action which infringes

the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the

20

Fourteenth Amendment, Congress would be the “ guardian

of its own conscience” as to what legislation on the school

integration subject is more or less “ appropriate.” In fact,

it has been noted that in other fields it has not been un

common for Congress to leave detailed administration to

state control and discretion so long as such control and

discretion are kept within the framework dictated by fed

eral law. Steward Machine Co. v. Davis, 301 U. S. 548,

and Parker v. Brown, 317 II. 8. 341.

The Constitution has conferred upon Congress the

power to secure equal educational opportunities in the

public schools for all children regardless of race. If Con

gress has failed and should continue to fail in exercising

its powers whereby equal educational opportunity is denied

by reason of state laws “ the remedy will ultimately be

with the people.” “ The Constitution has left the perform

ance of many duties in our governmental scheme to depend

on the fidelity of the executive and legislative action and,

ultimately, on the vigilance of the people in exercising their

political rights.” Colegrove v. Green, 328 U. S. 549, 556.

It is a matter of particular interest here that on the

very same day this Court decided the school segregation

cases (May 17, 1954) the Court also decided a very import

ant case arising under the Federal Tort Claims Act, 60

Stat. 842. The case was United States v. Gilman, 347 U. S.

507. In construing the act, the unanimous Court, through

Mr. Justice Douglas said, 347 U. 8. at 511.

“ Here a complex of relations between fed

eral agencies and their staffs is involved. More

over, the claim now asserted, though the product of

a law Congress passed, is a matter on which Congress

has not taken a position. It presents questions of

policy on which Congress has not spoken. The selec

tion of that policy, which is most advantageous to

the whole, involves a host of considerations that must

21

be weighed and appraised. That function is more

appropriately for those who write the laws, rather

than those who interpret them.”

In the instant cases the Court is most certainly deal

ing with ‘ ‘ a complex of relations ’ ’ between the federal gov

ernment on the one hand and the state governments on the

other. The specific problem of implementing Section 1 of

the Fourteenth Amendment as interpreted by this Court is

a matter on which Congress has not taken a position over

a period of eighty-six years and presents serious “ ques

tions of policy.” The selection of policy relating to the

integration of the races in public schools “ involves a host

of considerations that must be weighed and appraised.”

This Court should, in some appropriate manner, leave the

details of the solution of the problem “ to those who write

the laws.”

CONCLUSION'

The point which is urged here with most emphasis is

that a decree of this Court ordering immediate integration

of the white and negro children would have a most dis

astrous effect upon the public school system of Arkansas.

Likewise, it would most seriously disrupt the efforts of

the leaders of both races in solving the racial problem in

Arkansas in all its various aspects. No person or court can

predict at this time what the consequences would ultimately

be. There is no need for immediate integration in the pub

lic schools. It is not required by the Constitution.

The problem of integration of races in the public

schools is of such magnitude that it can be solved effec

tively only by a gradual process which would vary from

locality to locality. It is probably safe to assert at this

time that no person or group of persons — not even any

court — has formulated any definite plan of integration

22

which would operate successfully in the school districts of

Arkansas. As to the four cases now before the Court,

the plan for integration in the districts which would he

directly affected by those cases must, for the time being

at least, be formulated, developed and finally concluded

under the supervision and control of the courts of first

instance. The decrees of this Court should accord to the

lower courts the very widest range of discretion in bring

ing about integration in a manner which will promote,

rather than retard the ultimate solution of the whole

problem.

Finally and most earnestly, it is urged that this Court,

by a supplemental opinion, point out in no uncertain terms

that the integration problem is one which should be solved

by Congress under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. The American system of government being what it

is, this Court cannot compel Congress to act. But cer

tainly this Court can, by some appropriate suggestion,

bring about prompt and appropriate action by that branch

of the government in which the people themselves, by

adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, lodged the power

to adopt, the appropriate plan to correct the conditions

which, so this Court has said, the states have brought

about in violation of the Amendment.

If the powers of this Court were not limited by the

Constitution, the proper decrees of this Court in the pend

ing cases would be to “ remand the cases” to Congress

with directions to take appropriate action. Lacking the

power to command Congress, the next best thing would be

a most urgent invitation to Congress from this Court. It

is such a course which this Court is asked to adopt to the

very limit of its power. If the Court complies with this

request, then the solution of the problem will rest where it

23

was intended by the Constitution that it should rest—

with the Congress.

November 15,1954.

Respectfully submitted,

T om G entry

Attorney General

State of Arkansas

State Capitol

Little Rock, Arkansas

J ames L. S loan

Assistant Attorney General

State of Arkansas

State Capitol

Little Rock, Arkansas

R ichard B. M cCulloch

Special Asst. Attorney General

State of Arkansas

Forrest City, Arkansas

25

APPENDIX

ARKANSAS SCHOOL ENROLLMENT

1953-54 SESSION

C O U N T Y

E n rollm en t

W h ite N egro T ota l

A n n ua l

R eceip ts

A n n u a l

D isb 'm ts

Arkansas . . . 3,630 1,360 4,990 $ 891,277 $ 732,917

Ashley . . . . 3,963 2,367 6,330 1,018,902 895,782

Baxter . . . . 2,148 X X X 2,148 326,545 286,029

Benton . . . . 7,443 1 7,444 1,199,694 1,046,447

Boone .......... 3,516 X X X 3,516 488,271 483,435

Bradley . . . . . 2,064 932 2,996 479,622 454,240

Calhoun . . . . 1,056 592 1,648 286,115 263,004

Carroll........... 2,240 X X X 2,240 330,165 315,957

C hicot.......... 2,461 3,053 5,514 837,044 666,743

Clark . . . . . 3,430 1,569 4,999 719,768 644,724

C la y ............. 5,899 X X X 5,899 712,092 695,944

Cleburne . . . 2,466 X X X 2,466 273,697 257,370

Cleveland . . . 1,546 526 2,072 353,646 333,275

Columbia . . . 3,679 2,807 6,486 1,010,188 927,011

Conway . . . . 2,721 1,211 3,932 535,174 489,141

Craighead . . . 11,264 295 11,559 1,502,603 1,389,577

Crawford . . . 5,147 87 5,234 647,874 635,714

Crittenden . . 4,012 6,909 10,921 1,254,324 1,052,578

C ross............ 4,106 1,985 6,091 797,101 731,553

Dallas . . . . 1,659 1,221 2,880 467,792 430,774

D esha........... 3,426 3,078 6,504 824,451 730,117

D re w ........... 2,237 1,366 , 3,603 544,724 463,941

Faulkner . . . 3,981 612 4,593 633,314 620,258

Franklin . . . 3,033 38 3,071 408,118 376,237

Fulton . . . . 1,728 X X X 1,728 243,406 232,057

Garland . . . . 8,045 910 8,955 1,449,747 1,392,016

G rant........... 2,121 203 2,324 381,496 364,546

Greene . . . . 6,608 X X X 6,608 856,064 781,482

26

ARKANSAS SCHOOL ENROLLMENT

1953-54 SESSION

C O U N T Y

E n rollm en t

W h ite N egro T ota l

A n n ua l

R eceip ts

A n n u a l

D isb 'm ls

Hempstead . . 2,965 2,355 5,320 783,593 707,316

Hot Spring . . 4,860 744 5,604 1,020,340 877,411

Howard . . . . 2,333 809 3,142 511,605 449,967

Ind’p’nd’nce . 4,723 77 4,800 637,999 593,318

Izard ............. 2,093 14 2,107 240,407 224,549

Jackson . . . . 5,005 904 5,909 824,448 766,556

Jefferson . . . 8,869 8,025 16,894 2,353,543 2,038,288

Johnson . . . . 3,159 41 3,200 450,995 434,097

Lafayette . . . 1,629 1,614 3,243 560,538 480,749

Lawrence . . . 4,857 55 4,912 732,762 670,184

L e e ............... 2,316 3,552 5,868 626,368 537,960

Lincoln . . . . 1,744 1,887 3,631 544,104 470,376

Little River . 1,799 964 2,763 438,760 393,134

Logan .......... 3,230 169 3,399 558,614 482,709

Lonoke . . . . 4,518 1,428 5,946 829,476 723,716

Madison . . . . 2,640 X X X 2,640 277,237 266,346

Marion . . . . 1,516 X X X 1,516 254,566 232,608

M iller.......... 5,927 2,106 8,033 1,143,452 1,027,337

Mississippi . . 13,218 4,789 18,007 2,366,353 2,302,446

Monroe . . . . 2,394 2,176 4,570 526,483 483,524

Montgomery 1,416 3 1,419 284,030 232,634

Nevada . . . . 1,893 1,498 3,391 588,702 494,588

Newton . . . . 1,946 X X X 1,946 220,148 212,226

Ouachita . . . 4,781 3,637 8,418 1,336,720 1,095,448

P e rry ........... 1,297 48 1,345 221,272 190,383

Phillips . . . . 4,294 6,409 10,703 1,132,056 1,036,507

P ik e .............. 2,003 74 2,077 348,979 304,222

Poinsett . . . . 8,022 694 8,716 1,035,175 972,903

P o lk ............. 2,931 X X X 2,931 534,865 439,619

P o p e ............. 4,270 123 4,393 608,356 589,653

27

ARKANSAS SCHOOL ENROLLMENT

1953-54 SESSION

E n rollm en t A n n ua l A n n u a l

C O U N T Y W hite N egro T ota l R eceip ts D isb 'm ts

Prairie . . . . 2,296 575 2,871 433,500 413,484

Pulaski . . . . 27,695 9,088 36,783 6,413,057 5,871,522

Randolph . . . 2,808 31 2,839 374,322 337,164

Saline.......... 4,800 88 4,888 791,254 729,381

S co tt ............ 1,564 X X X 1,564 295,193 254,689

Searcy . . . . 2,200 X X X 2,200 278,123 266,129

Sebastian . . . 12,400 903 13,303 2,138,442 2,023,826

S evier.......... 2,264 264 2,528 479,528 376,536

Sharp ........... 2,345 X X X 2,345 328,387 308,232

St. Francis . . 3,740 5,300 9,040 948,998 886,075

Stone ........... 1,590 X X X 1,590 194,428 182,477

U nion .......... 7,524 4,325 11,849 2,264,543 1,892,648

Van Buren . . 1,960 17 1,977 268,505 256,415

Washington . 9,299 64 9,363 1,262,843 1,213,977

W h ite ........... 7,817 302 8,119 1,230,306 1,160,193

Woodruff . . . 2,552 1,946 4,498 553,958 544,544

Y e l l .............. 2,910 90 3,000 539,774 477,755

TOTAL . . . . 314,041 98,310 412,351 $60,261,321 $54,618,690