Graham v. Florida Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

July 23, 2009

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Graham v. Florida Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners, 2009. f992ac08-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5d40f374-266a-44b3-a17c-61138c1cf166/graham-v-florida-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-petitioners. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

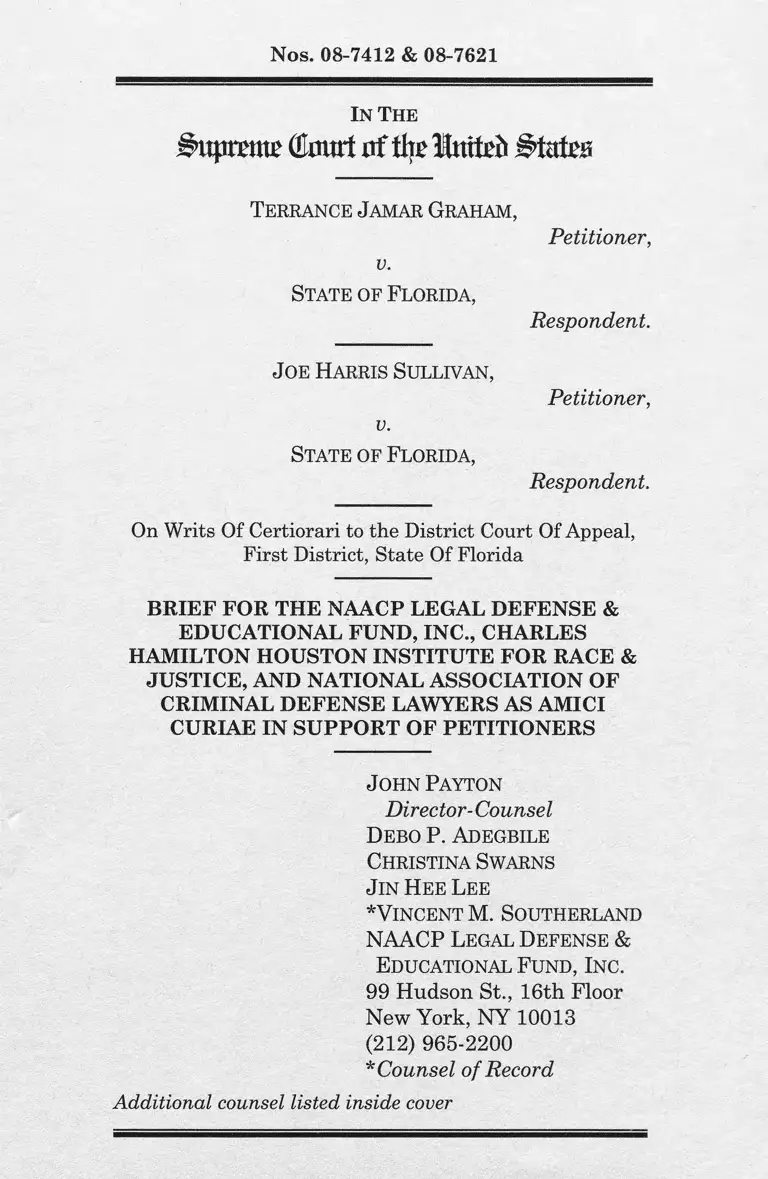

Nos. 08-7412 & 08-7621

In The

#uprimt£ (Lrnii iif % Uniizh M te

T errance J amar Graham ,

Petitioner,

v.

State o f F lorida ,

J oe H arris Sullivan ,

v.

State o f F lorida ,

Respondent.

Petitioner,

Respondent.

On Writs Of Certiorari to the District Court Of Appeal,

First District, State Of Florida

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., CHARLES

HAMILTON HOUSTON INSTITUTE FOR RACE &

JUSTICE, AND NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF

CRIMINAL DEFENSE LAWYERS AS AMICI

CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

J o h n P ayton

Director- Counsel

D ebo P. A degbile

Ch ristin a Swarns

J in H ee L ee

*Vin c e n t M. Southerland

NAACP L egal D e fe n s e &

Educational F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

* Counsel o f Record

Additional counsel listed inside cover

Charles J . O g l et r e e , J r .

R obert J . Sm ith

Charles H am ilton H ouston

In stitu te fo r Race & J u stic e

125 Mt. Auburn St., 3rd Floor

Cambridge, MA 02138

J effr ey L. F ish er

N ational A ssociation of

Crim inal D e fe n s e Lawyers

1660 L St., NW, 12th Floor

W ashington, DC 20036

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

P ursuant to Supreme Court Rule 29.6, amici

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

Charles Hamilton Houston Institu te for Race and

Justice, and National Association of Criminal De

fense Lawyers certify th a t each are non-profit corpo

rations with no parent companies, subsidiaries, or

affiliates th a t have issued shares to the public.

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS...............................................ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES......................... ...... . iv

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE........... .................1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT...................................... 2

ARGUM ENT................................................................... 3

I. The Challenges of Developing an Effective

Attorney-Client Relationship with a Teen

a g e r............................................ 4

A. A Child’s Tendency to M istrust Adults

Impedes the Development of a Proper

Attorney-Client R elationship.......................7

B. Adolescents’ Limited Comprehension

of Core Legal Concepts, Institutional

Actors, and the Adjudicatory Process

Complicates the Development of an

Effective Attorney-Client Relationship... 11

C. Adolescent Deficits in Judgm ent,

Temporal Perspective and Susceptibil

ity to Peer Influence Ham per Effective

Representation of a Child C lient...............12

II. Compromised Attorney/Child-Client Rela

tionships Hinder Defense Counsel’s Ability

To Conduct A Constitutionally Appropriate

Factual Investigation......................................... 15

III. Compromised Attorney/Child-Client Rela

tionships Can Yield Flawed Decisions to

Accept or Reject Plea B arg a in s............. ......... 19

Ill

IV. Compromised Attorney/Child-Client Rela

tionships Can Contribute to Children Fac

ing Inappropriately H arsh Prison Condi

tions ....................................................................... 25

CONCLUSION............................................................ 27

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

A tkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002)....................3

Florida v. Nixon, 543 U.S. 175 (2004).................... 20

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963)............ 5

H unt v. Blackburn, 128 U.S. 464 (1888) .............. 16

Illinois v. Wardlow, 528 U.S. 119 (2000)............... 10

In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967)................................. 3,5

In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358 (1970)............................3

Kennedy v. Louisiana, 554 U .S .____, 128 S.

Ct. 2641 (2008)......................................................... 17

Kent v. United States, 383 U.S. 541 (1966)............. 3

McCarthy v. United States, 394 U.S. 459

(1969)........................................................................ 21

Morris v. Slappy, 461 U.S. 1 (1983)............................ 5

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932)......................5

Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 563 (2005)....... 3,4,5,12

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668

(1984)......................................................... 5,15,16, 18

Thompson v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. 833 (1988).......... 4

United States v. Leviner, 31 F. Supp. 2d 23

(D. Mass. 1998)........................................................ 10

Upjohn Co. v. United States, 449 U.S. 383

(1981).......................................................................... 16

Wiggins v. Sm ith, 539 U.S. 510 (2003)................... 15

Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362 (2000)................ 15

U.S. C o n stitu tio n a n d S ta tu te s

U.S. Const, amend. VIII 3,4,6,27

Other Authorities

A.B.A. Standards for Criminal Justice:

Prosecution & Def. Function, Standard 4-

3 .2(a)...................................................................15, 16

A.B.A. Standards for Criminal Justice:

Prosecution & Def. Function, Standard 4-

6.1(b)..................................................................... 19-20

Paolo G. Annino, Children in Florida A dult

Prisons: A Call for a Moratorium, 28 Fla.

St. U. L. Rev. 471 (2001)....................................... 25

Paolo G. Annino et al., Juvenile Life Without

Parole for Non-Homicide Offenses: Florida

Compared to the Nation (July 2009).......................8

Annette Ruth Appell, Representing Children

Representing What?: Critical Reflections on

Lawyering for Children, 39 Colum. Hum.

Rts. L. Rev. 573 (2008)............. ......... ................. . 8

Douglas A. Berman, From Lawlessness To

Too Much Law?: Exploring the Risk of

Disparity from Differences in Defense

Counsel Under Guidelines Sentencing, 87

Iowa L. Rev. 435 (2002)............ ............................ 20

Donna M. Bishop, Juvenile Offenders in the

A dult Criminal Justice System, 27 Crime

& Just. 81 (2000)................................. 10, 11, 25, 26

Donna M. Bishop & Hillary Farber, Joining

the Legal Significance of Adolescent Devel

opmental Capacities with the Legal Rights

VI

Provided by In Re Gault, 60 Rutgers L.

Rev. 125 (2007).................................................. 13-14

C. Antoinette Clarke, The Baby and the

Bathwater: Adolescent Offending and P u

nitive Juvenile Justice Reform, 53 U. Kan.

L. Rev. 659 (2005)......................................... 2,6,7,21

Laura Cohen & Randi Mandelbaum, Kids

Will Be Kids: Creating a Framework for In

terviewing and Counseling Adolescent Cli

ents, 79 Temp. L. Rev. 357 (2006)......12, 13, 14,17

Douglas L. Colbert et al., Do Attorneys Really

M atter?: The Empirical and Legal Case for

the R ight o f Counsel at Bail, 23 Cardozo L.

Rev. 1719 (2002)..................................................... 18

Steven Drizin & Greg Luloff, Are Juvenile

Courts a Breeding Ground for Wrongful

Convictions'?, 34 N. Ky. L. Rev. 257 (2007)......... 4

Jeffrey Fagan, This Will Hurt Me More Than

It Hurts You, 16 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics &

Pub. Pol’y 1 (2002).................................................. 25

Lisa M. Farabee, Disparate Departures Un

der the Federal Sentencing Guidelines: A

Tale of Two Districts, 30 Conn. L. Rev. 569

(1998)..........................................................................20

Barry Feld, A Century of Juvenile Justice: A

Work in Progress or a Revolution that

Failed, 34 N. Ky. L. Rev. 189 (2007)............... 9,12

Barry Feld, Unmitigated Punishment: Ado

lescent Criminal Responsibility and LWOP

Sentences, 10 J. L. & Fam. Stud. 11 (2007)....... 13

Thomas Grisso, The Competence of Adoles

cents as Trial Defendants, 3 Psychol. Pub.

Pol’y & L. 3, 16 (1997).............. ................... 7,11,23

Thomas Grisso et al., Juveniles’ Competence

to S tand Trial: A comparison of Adoles

cents’ and A du lts’ Capacities as Trial De

fendants, 27 Law and Hum. Behav. No. 4,

333 (2005)..................................................... ........... 24

Samuel Gross, Exonerations in the United

States 1989 Through 2003, 95 J. Crim. L.

& Criminology 523 (2005)..................................... 4

Jan e t C. Hoeffel, Toward a More Robust

Right to Counsel of Choice, 44 San Diego L.

Rev. 525 (2007).......................................... 10, 17, 22

Kristin Henning, Loyalty, Paternalism, and

Rights: Client Counseling Theory and the

Role of Child’s Counsel in Delinquency

Cases, 81 Notre Dame L. Rev. 245

(2006)........................................................... 12, 13, 14

Theresa Hughes, A Paradigm of Youth Client

Satisfaction: Heightening Professional Re

sponsibility for Children’s Advocates, 40

Colum. J.L. & Soc. Probs. 551 (2007)............ 7, 13

Hum an Rights Watch, The Rest of Their

Lives: Life Without Parole for Youth Of

fenders in the United States in 2008 (2008)........9

Michelle Jacobs, People from the Footnotes:

The Missing Element in Client-Centered

Counseling, 27 Golden Gate U. L. Rev. 345

(1997)......................................................................... 10

Amanda M. Kellar, They Ye Just Kids: Does

Incarcerating Juveniles With Adults Vio

late the Eighth Am endm ent?, 40 Suffolk U.

L. Rev. 155 (2006)

vii

25

vm

Sheldon Krantz et al., The Right to Counsel

in Criminal Cases: The M andate of

Argersinger v. Ham lin (1976).............................. 18

Michael Lindsay, The Impact of Gault on the

Representation of Minority Youth, 44 No. 3

Crim. Law Bulletin 4 (2008)....................................9

N at’l Council on Crime and Delinquency,

A nd Justice for Some: Differential Treat

ment of Youth of Color in the Justice Sys

tem, (Jan. 2007).......................................................... 9

Kenneth Nunn, The Child as Other: Race

and Differential Treatment in the Juvenile

Justice System, 51 DePaul L. Rev. 679

(2002)............................................................................ 9

Michael Pinard, The Logistical and Ethnical

Difficulties o f Informing Juveniles About

the Collateral Consequences of Adjudica

tions, 6 Nev. L. J. 1111 (2006)....................... 13, 24

Patricia Puritz & Katayoon Majd, Ensuring

Authentic Youth Participation in Delin

quency Cases: Creating a Paradigm for

Specialized Juvenile Defense Practice, 45

Fam. Ct. Rev. 466 (2007)............................ 6, 10, 21

Melinda Schmidt et al., Effectiveness of Par

ticipation as a Defendant: The Attorney-

Juvenile Client Relationship, 21 Behav.

Sci. Law 175, 179 (2003)....................................... 22

Elizabeth S. Scott & Thomas Grisso, Devel

opmental Incompetence, Due Process, and

Juvenile Justice Policy, 83 N.C. L. Rev.

793, 816 (2005).... ............................................. 14, 23

Elizabeth S. Scott & Thomas Grisso, The

Evolution o f Adolescence: A Developmental

IX

Perspective on Juvenile Justice Reform, 88

J. Crim. L. & Criminology 137 (1997)........... 7, 13

Elizabeth S. Scott & Laurence Steinberg,

Blam ing Youth, 81 Tex. L. Rev. 799 (2003).........6

Abbe Smith, “I A in ’t Takin No Plea”: The

Challenges in Counseling Young People

Facing Serious Time, 60 Rutgers L. Rev.

11 (2007)................................................... ............... 19

Laurence Steinberg, Adolescent Development

and Juvenile Justice, 5 Ann. Rev. Clin.

Psych. 459 (2009)......... ........ 2, 6, 11, 13, 14, 17, 26

U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Office of Juvenile Ju s

tice and Delinquency Prevention, Dispro

portionate Minority Confinement 2002 Up

date (Sept. 2004).................... 9

U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Office of Juvenile Ju s

tice and Delinquency Prevention, Minori

ties in the Juvenile Justice System (Dec.

1999)................. ...8

U.S. Dep’t of Justice, OJJDP Statistical

Briefing Book (2008)............................................... 10

U.S. Dept, of Justice, Office of Juvenile Ju s

tice and Delinquency Prevention, Juveniles

in Corrections (June 2004)...................... 8

Julie W hitman & Robert Davis, Snitches Get

Stitches: Youth Gangs, and Witness In

timidation in Massachusetts, The National

Center for Victims of Crime (2007)..................... 18

1

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE1

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund,

Inc. (LDF), is a non-profit corporation formed to as

sist African Americans and others who are unable,

on account of poverty, to employ legal counsel to se

cure their rights by the prosecution of lawsuits. LDF

has a long-standing concern with the impact of racial

discrimination on the criminal justice system. It has

served as counsel of record and/or as amicus curiae

in th is Court in, inter alia, Furman v. Georgia, 408

U.S. 238 (1972), McClesky v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279

(1987), Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965),

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972) and

Ham v. South Carolina, 409 U.S. 524 (1973) and ap

peared as amicus curiae in Roper v. Simmons, 543

U.S. 551 (2005), Kimbrough v. United States, 552

U.S. 85 (2007), Miller-El v. Cockrell, 537 U.S. 322

(2003), and Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986).

The Charles Hamilton Houston Institu te for Race

and Justice a t Harvard Law School (CHHIRJ) con

tinues the unfinished work of Charles Hamilton

Houston, one of the Twentieth Century’s most ta l

ented legal scholars and litigators. The CHHIRJ

m arshals resources to advance Houston’s dreams for

a more equitable and just society. It brings together

students, faculty, practitioners, civil rights and

business leaders, community advocates, litigators,

1 Letters of consent by the parties to the filing of this brief

have been lodged with the Clerk of this Court. Pursuant to S.

Ct. Rule 37.6, counsel for the amici states that no counsel for a

party authored this brief in whole or in part, and that no per

son other than the amici, their members, or their counsel made

a monetary contribution to the preparation or submission of

this brief.

2

and policymakers to focus on, among other things,

reforming criminal justice policies.

The National Association of Criminal Defense

Lawyers (NACDL) is a non-profit corporation with

more th an 10,000 members nationwide and 28,000

affiliate members in 50 states, including private

crim inal defense lawyers, public defenders and law

professors. The American Bar Association recog

nizes NACDL as an affiliate organization and

awards it full representation in its House of Dele

gates. NACDL was founded in 1958 to promote

study and research in the field of criminal law, to

dissem inate and advance knowledge of the law in

the area of criminal practice, and to encourage the

integrity, independence, and expertise of defense

lawyers in criminal cases. NACDL seeks to defend

individual liberties guaranteed by the Bill of Rights

and has a keen in terest in ensuring th a t legal pro

ceedings are handled in a proper and fair manner.

Among NACDL’s objectives is the promotion of the

proper adm inistration of justice.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Experience, science and this Court’s precedents

all recognize th a t children are fundam entally differ

ent th an adults.2 One of the most significant aspects

2 Since its inception, the juvenile justice system has coun

tered the stark differences between youth and adults through

“individual assessment and treatment” of children in an effort

to reintegrate young offenders into society. C. Antoinette

Clarke, The Baby and the Bathwater: Adolescent Offending and

Punitive Juvenile Justice Reform, 53 U. Kan. L. Rev. 659, 667

(2005); see also Laurence Steinberg, Adolescent Development

and Juvenile Justice, 5 Ann. Rev. Clin. Psych. 459, 462 (2009)

(“[I]t is clear that the founders of the juvenile justice system

3

of this difference is th a t children who commit crimi

nal offenses are less culpable than adults. Roper v.

Simmons, 543 US. 563, 569-70 (2005). These princi

ples bear directly on the constitutionality of juvenile

life without parole sentences. Such sentences fail to

comport with the requirem ents of the Eighth

Amendment for the reasons raised by the Petitioners

and supporting amici and because the unique char

acteristics of youth can critically underm ine defense

counsel’s ability to effectively assist their teenaged

clients, and the compromised attorney-client re la

tionship contributes to an increased likelihood of u n

reliable sentencing outcomes th a t fail to reflect cul

pability and guilt. A tkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304,

320 (2002). For these reasons, individuals younger

than age 18 at the time of the offense should not be

subject to life without parole sentences.

ARGUMENT

This brief explains how the characteristics of

youth can interfere with the development of an effec

tive attorney-client relationship and how the im

paired relationship with counsel, in combination

with the concerns raised by Petitioners and their

began from the premise that adolescents are developmentally

different from adults in ways that should affect our interpreta

tion and assessment of their criminal acts.”). This Court has

appropriately addressed the developmental concerns of youth

by affording children the rehabilitative benefits of the juvenile

justice system and such procedural and substantive safeguards

rooted in due process as the rights to counsel, confrontation,

cross examination, proof beyond a reasonable doubt and free

dom from compelled self-incrimination. See In re Winship, 397

U.S. 358 (1970); In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967); Kent v. United

States, 383 U.S. 541 (1966).

4

supporting amici, so underm ine the reliability of life

without parole sentences th a t such punishm ents are

unconstitutionally disproportionate for children

younger than age 18 a t the time of the offense.

This Court has acknowledged th a t a child’s im

m ature judgment, impulsive decision-making and

vulnerability to peer pressure reduce culpability

such th a t the capital sentencing of offenders younger

th an age 18 violates the Eighth Amendment. See

Roper, 543 U.S. a t 569-70; Thompson v. Oklahoma,

487 U.S. 833, 834-35 (1988). These attributes, in

addition to the dynamics of race, class and the n a

ture of indigent defense, can also disadvantage a

child’s relationship with counsel and contribute to a

significant risk of an unreliable sentencing outcome

th a t fails to reflect actual culpability.3 Given the se

verity and finality of a death-in-prison sentence, this

Court should categorically exempt children from life

without parole sentences.

I. The C hallenges o f D evelop ing an Effective

A ttorney-C lient R elationship w ith a T een

ager.

A criminal defense attorney’s ability to effectively

represent her client and fairly subject the prosecu

3 See Samuel Gross, Exonerations in the United States 1989

Through 2003, 95 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 523, 545, 548-51

and Table 6 (2005) (describing unreliable outcomes for children

and adolescents in the criminal justice system and noting

higher concentration of false confessions among adolescent as

compared to adult exonerees); see also Steven Drizin & Greg

Luloff, Are Juvenile Courts a Breeding Ground for Wrongful

Convictions?, 34 N. Ky. L. Rev. 257 (2007) (discussing charac

teristics of children, juvenile, and criminal justice system that

lead to wrongful convictions).

5

tion’s case to “a reliable adversarial testing process,”

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 688 (1984)

(citations omitted), is critically dependent on the ex

istence of a trusting attorney-client relationship and

the client’s ability to assist counsel, guided by a

meaningful understanding of the legal proceedings.

See Powell u. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45, 69 (1932) (sta t

ing th a t defendants need “the guiding hand of coun

sel a t every step in the proceedings against

[them]”).4

This Court has acknowledged th a t children, as a

class, “lack [ ] m aturity and [possess] an underdevel

oped sense of responsibility [that] often result[s] in

impetuous and ill-considered actions and decisions,”

are “vulnerable and susceptible to negative influ

ences and outside pressures,” and have a “transitory,

less fixed” personality. Roper, 543 U.S. a t 569 (cita

tions omitted). Experts consistently concur with this

Court’s assessm ent and note th a t each of these

youthful qualities, which are rooted in the neurologi

cal differences between adults and children,5 can

4 See also Morris v. Slappy, 461 U.S. 1, 21 n.4 (1983) (citing

A.B.A. Standards for Criminal Justice, commentary to § 4.29

(2d ed. 1980)) (“Nothing is more fundamental to the lawyer-

client relationship than the establishment of trust and confi

dence.”); Gault, 387 U.S. at 36 (1967) (determining that a child

“needs the assistance of counsel to cope with problems of law, to

make skilled inquiry into the facts, to insist upon regularity of

the proceedings, and to ascertain whether he has a defense and

to prepare and submit it”); Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335,

344-45 (1963) (describing the right to counsel as “fundamental

and essential to fair trials”).

5 These unique characteristics of adolescent children are a

direct product of the neurological development of the brains

prior to adulthood. The frontal lobe of the brain, which “man

6

and often do impede a child’s judgment, decision

making, and ability to develop the trust, confidence

and open communication necessary for an effective

attorney-client relationship. See Steinberg, supra

note 2, a t 468-71; Patricia Puritz & Katayoon Majd,

Ensuring Authentic Youth Participation in Delin

quency Cases: Creating a Paradigm for Specialized

Juvenile Defense Practice, 45 Fam. Ct. Rev. 466, 474

(2007).

Many characteristics of youth complicate the de

velopment of a proper attorney-client relationship.

As detailed below, a teenager’s tendency to d istrust

adults, lim ited understanding of the criminal justice

system and the role of the defense lawyer within it,

deficits in judgment, and considerations of race and

class combine to inhibit the development of an effec

tive attorney/child-client relationship and further

dem onstrate how juvenile life without parole sen

tences cannot be reconciled with the Eighth

Amendment.

ages impulse control, long-term planning, priority setting, cali

bration of risk and reward and insight [,] is still growing and

changing during adolescence and beyond . . . .” Abbe Smith, “I

Ain’t Takin No Plea”: The Challenges in Counseling Young Peo

ple Facing Serious Time, 60 Rutgers L. Rev. 11, 20 (2007); see

also Elizabeth S. Scott & Laurence Steinberg, Blaming Youth,

81 Tex. L. Rev. 799, 816 (2003) (discussing the connection be

tween brain development, judgment, and decision-making).

“[Tjasks involving planning, self control, inhibiting impulsive

actions, learning from experience, social judgment, and weigh

ing rewards and risks in decision-making situations” may not

reach full development “until adolescents reach their twenties.”

Clarke, supra note 2, at 710.

7

A. A Child’s T endency to M istrust A dults

Im pedes the D evelopm ent o f a Proper At

torney-C lient R elationship .

The well-known failure of adolescents to relate to

and tru s t adults and authority figures presents a

fundam ental impediment to the candid communica

tion necessary for an effective attorney-client re la

tionship. See Thomas Grisso, The Competence of

Adolescents as Trial Defendants, 3 Psychol. Pub.

Pol’y & L. 3, 16 (1997) (explaining th a t th is m istrust

may be the product of the natu ra l adolescent stage of

a child working through “developmental issues of in

dependence and identity” or from previous experi

ences with adult authority figures). A child’s process

of “establishing autonomy from . . . parents” can

m anifest itself in a “rebellion against parental values

. . . until late adolescence or early adulthood.”

Clarke, supra note 2, a t 697 (footnotes omitted); see

also Elizabeth S. Scott & Thomas Grisso, The Evolu

tion of Adolescence: A Developmental Perspective on

Juvenile Justice Reform, 88 J. Crim. L. & Criminol

ogy 137, 156 (1997) ((citing Terrie Moffitt, Adoles

cent-Limited and Life Course Persistent Antisocial

Behavior: A Developmental Taxonomy, 100 Psychol.

Rev. 674 (1993)) noting th a t “adolescents are striving

for elusive autonomy from parental and adult au

thority in a context in which most privileges of adult

status are withheld”). As a result of th is process,

adolescents are notoriously “reluctant to participate

in conversation with adults or answer their ques

tions . . . .” Theresa Hughes, A Paradigm of Youth

Client Satisfaction: Heightening Professional Re

sponsibility for Children’s Advocates, 40 Colum. J. L.

& Soc. Probs. 551, 566 (2007).

8

This adolescent aversion is likely to affect the a t

torney-client relationship because “lawyers are not

fam iliar figures in children’s lives, unlike teachers,

doctors, and nurses. . . . [YJouth are more likely

than adults to refuse to speak with their attorney,

thereby inhibiting the effectiveness of the represen

tation.” Id. a t 566-67 (footnotes omitted). As a re

sult, children are more likely to d istrust counsel and

are less likely to engage in the type of communica

tion required for an effective relationship with an

attorney.

T rust barriers may also be exacerbated by the

cross-racial nature of m any attorney/child-client re

lationships.6 African-American children are over-

represented7 among those subjected to life-without- -

6 See Annette Ruth Appell, Representing Children Repre

senting What?: Critical Reflections on Lawyering for Children,

39 Colum. Hum. Rts. L. Rev. 573, 596 (2008) (describing cross

racial nature of representation for children).

7 The overrepresentation of African-American children in

the criminal justice system is a well documented subject of nu

merous respected studies. The United States Department of

Justice, Office of Justice Programs noted that in 2004, minority

youth comprised 70% of juveniles held in custody for violent

offenses, and that black youth were twice as likely as white

youth to be sentenced to prison. See U.S. Dept, of Justice, Of

fice of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Juveniles

in Corrections, 9, 21 (June 2004). In 1999, DOJ found that

“[mjore than three-quarters of youth newly admitted to State

prison were minorities.” U.S. Dept, of Justice, Office of Juve

nile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Minorities in the Ju

venile Justice System, 15 (Dec. 1999); see also Paolo G. Annino

et al., Juvenile Life Without Parole for Non-Homicide Offenses:

Florida Compared to the Nation, 3 (July 2009) (finding that in

Florida, the state from which the two cases before this Court

arise, 84% of the total population of children serving life with

out parole for non-homicide offenses are African American);

9

parole sentences,* 3 * * * * 8 and many factors—including the

phenomenon of racial profiling and the negative im

pression of the criminal justice system th a t it n a tu

rally produces—are likely to breed significant m is

tru s t of the criminal justice system and its actors,

including defense attorneys, among African-

Barry Feld, A Century of Juvenile Justice: A Work in Progress

or a Revolution that Failed, 34 N. Ky. L. Rev. 189, 252 (2007)

(“[F]orty-one of forty-two states found minority youths overrep

resented in secure detention facilities and all thirteen states

that analyzed institutional commitment decisions reported dis

proportionate minority confinement.”); Michael Lindsay, The

Impact of Gault on the Representation of Minority Youth, 44 No.

3 Crim. Law Bulletin 4 (2008) (African-American youth are in

the juvenile justice system are “most consistently, and perva

sively overrepresented across the United States.”); Nat’l Coun

cil on Crime and Delinquency, And Justice for Some: Differen

tial Treatment of Youth of Color in the Justice System, 3, 34

(Jan. 2007) (finding that in 2002, three out of four adolescents

who were newly admitted into adult prisons were youth of

color, and “African American youth accounted for 58% of total

admissions to adult prisons”); Kenneth Nunn, The Child as

Other: Race and Differential Treatment in the Juvenile Justice

System, 51 DePaul L. Rev. 679, 686-87 (2002) (discussing the

racial disparities present in the juvenile justice system and

disproportionate number of African-American youth arrested,

detained, charged and sentenced); U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Office

of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Dispropor

tionate Minority Confinement 2002 Update, 2 (Sept. 2004) (ex

amining data from 1990-1997 and describing African-American

youth as overrepresented at all stages of the juvenile justice

system compared with their proportion in the U.S. population).

8 See Human Rights Watch, The Rest of Their Lives: Life

Without Parole for Youth Offenders in the United States in

2008, 39 (2008) (stating that nationwide, black teenagers are

ten times more likely to receive life-without-parole sentences

than their white counterparts and African Americans consti

tute 60% of youth serving life without parole sentences).

10

American youth.9 See, e.g., Illinois v. Wardlow, 528

U.S. 119, 133-34 nn.9-10 (2000) (Stevens, J., concur

ring in part and dissenting in part) (noting the

prevalence of racial profiling by law enforcement

against citizens of color); U.S. v. Leviner, 31 F. Supp.

2d 23, 33 & n.26 (D. Mass. 1998) (describing the

criminal history score of an African-American defen

dant as reflective of racial disparities th a t have

grown out of racial profiling). This problem of dis

tru s t may also be enhanced among poor children

who m ust rely on appointed counsel whose commit

m ent to zealous advocacy the child may doubt. See

Donna M. Bishop, Juvenile Offenders in the A dult

Criminal Justice System, 27 Crime & Just. 81, 136-

37 (2000) (footnote omitted) (finding several respon

dents in the study to be “especially critical of public

defenders, whom they believed feigned advocacy in

an effort to m anipulate them to accept pleas tha t

were not in their best in terests”); Puritz, supra, a t

474 (citing studies “suggesting] th a t children are

less likely to tru s t or communicate with attorneys

whom they know are court-appointed”).10

9 See Michelle Jacobs, People from the Footnotes: The Miss

ing Element in Client-Centered Counseling, 27 Golden Gate U.

L. Rev. 345, 377 (1997) (discussing influence of cultural dynam

ics on attorney-client relationship); Puritz, supra at 472 (“Re

search indicates that African American children . . . are consis

tently less likely than their White counterparts to trust their

defense attorneys.”).

10 As of 2007, African-American and Hispanic youth were

nearly three times as likely to live in poverty as white youth.

U.S. Dept, of Justice, OJJDP Statistical Briefing Book (2008),

available at http://ojjdp.ncjrs.gov/ojstatbb/population/

qa0140.asp.qaDate-2007.

http://ojjdp.ncjrs.gov/ojstatbb/population/

11

Thus the tru s t necessary for an effective and col

laborative relationship between attorney and client

is often underm ined by an adolescent defendant’s

age-based likelihood to d istrust counsel.

B. A dolescen ts’ L im ited C om prehension o f

Core Legal Concepts, In stitu tion a l Ac

tors, and the A djudicatory P rocess Com

p lica tes the D evelopm ent o f an E ffective

A ttorney-C lient R elationship .

The attorney-client relationship and its critical

requirem ent of confidentiality are difficult concepts

th a t few children can fully understand. Children of

ten assum e th a t their lawyers are required to report

the substance of their communications to the court

or other authority figures, such as police officers or

parents. Youth under age 19 often “incorrectly be

lieve [ ] th a t [a defense] attorney was authorized to

tell judges or police officers what was discussed in

confidential attorney-defendant conversations.”

Grisso, supra, a t 15 (citations omitted). Moreover,

children “may develop a belief th a t all adults in

volved in the proceedings are allied against [them],

perhaps after seeing defense attorneys and prosecu

tors chatting together outside the courtroom.”

Steinberg, supra note 2, a t 475. Accordingly,

“[m]any youths fail[ ] to differentiate the roles and

functions of judges, prosecutors, and defense counsel,

whom they perceived as one, and as adversarial.”

Bishop, supra, a t 136.

These m istaken beliefs can have devastating con

sequences. “[A] child who is unpersuaded by his a t

torney’s loyalty may simply withhold information

from the attorney, depriving both the attorney and

12

the child of an opportunity to exchange im portant

insights in the case.” Kristin Henning, Loyalty, Pa

ternalism, and Rights: Client Counseling Theory and

the Role of C hild’s Counsel in Delinquency Cases, 81

Notre Dame L. Rev. 245, 273 (2006).

C. A dolescen t D efic its in Judgm ent, Tem po

ral P ersp ective and Su scep tib ility to

P eer In fluence Hamper E ffective R epre

sen ta tion o f a Child Client.

A young client’s im m aturity in judgm ent and lim

ited tem poral perspective may frustrate the devel

opment of a viable relationship between counsel and

client. See Feld, supra note 7, a t 225 (“[Gjeneric de

velopmental lim itations im pair juveniles’ ability to

understand legal proceedings, make rational deci

sions, and assist counsel.”); Henning, supra, a t 272-

73 (discussing influence of peers, temporal perspec

tive and deficits in judgm ent on decision-making and

relationship with counsel). “It has been noted tha t

‘adolescents are overrepresented statistically in v ir

tually every category of reckless behavior.’” Roper,

543 U.S. a t 569 (quoting Jeffrey Arnett, Reckless Be

havior in Adolescence: A Developmental Perspective,

12 Developmental Rev. 339 (1992)). It is therefore

not surprising th a t deficiencies in judgm ent can also

prevent a child from fully considering all available

adjudicative options and lim it his or her ability to

“assess or integrate long-term consequences into

their analysis.” Laura Cohen & Randi Mandelbaum,

Kids Will Be Kids: Creating a Framework for Inter

viewing and Counseling Adolescent Clients, 79 Temp.

L. Rev. 357, 367 (2006). For example, an adolescent

“engaging in a cost-benefit analysis [may] ‘weigh the

particular cost or benefit [s]”’ of certain choices dif

13

ferently from an adult who possesses the experience

and tem poral perspective to make well-reasoned

choices. Id. a t 368 (quoting Elizabeth S. Scott, et al.

Evaluating Adolescent Decision M aking in Legal

Contexts, 19 L. & Hum. Behav. 221, 233 (1995)).

Similarly, an adolescent may “withhold information

from his attorney in order to feel the immediate

benefit of not fully incriminating himself, but fail to

recognize the long-term costs of compromising his

own defense . . . .” Henning, supra, a t 273; see also

Hughes, supra, a t 565 (noting the difficulty children

have in comprehending the role of a lawyer and the

influence on information sharing caused by differ

ences between children and adults in future orienta

tion, cost-benefit analytical processes, and the child’s

focus on immediate gains).11

11 See also Barry Feld, Unmitigated Punishment: Adolescent

Criminal Responsibility and LWOP Sentences, 10 J. L. & Fam.

Stud. 11, 53 (2007) (noting that adolescents “undersestimate

the magnitude or probability of risks, use a shorter time-frame,

and focus more on potential gains rather than losses” as com

pared to adults); Michael Pinard, The Logistical and Ethical

Difficulties, 6 Nev. L. J. 1111, 1121 (2006) (“[S]tudies have

found both that [children] do not understand the various

phases of the criminal process and that they cannot fully com

prehend long-term consequences (or tend to ignore these conse

quences in favor or immediate consequences) . . . .”); Scott, Evo

lution, supra, at 171 (noting that a youth’s narrow temporal

perspective, which leads to a focus on short-term rather than

long-term consequences, limited concept of time and tendency

to take risks can “influence judgments about the value of ac

cepting plea bargains”); Steinberg, supra note 2, at 475 (“Im

mature youths may lack capacities to process information and

exercise reason adequately in making trial decisions, especially

when the options are complex and their consequences are far

reaching.”); Donna M. Bishop & Hillary Farber, Joining the

Legal Significance of Adolescent Developmental Capacities with

14

The influential role th a t a teenager’s peers may

play in the decision-making process also has the po

ten tial to impede the development of a proper rela

tionship between counsel and client. “Peer influence

affects adolescent judgm ent both directly and indi

rectly.” Steinberg, supra note 2, a t 469. Adolescents

may “make choices in response to direct peer pres

sure” or act in ways th a t relate to their “desire for

peer approval and consequent fear of rejection

Id. As a result, judgm ents about collaboration and

cooperation with authorities and counsel are some

tim es made through the often illegitimate filter of a

child’s feelings about how decisions will inform and

define their role among peers. See Cohen, supra, at

363-64 (discussing the influence of peers on adoles

cent decision-making); Henning, supra, a t 273

(same); Elizabeth S. Scott & Thomas Grisso, Devel

opmental Incompetence, Due Process, and Juvenile

Justice Policy, 83 N.C. L. Rev. 793, 816 (2005)

(“[S ubstan tia l evidence supports th a t adolescents

are more susceptible to peer influence than adults. .

. At least during the period of early- and mid- ado

lescence, decisions often are driven by acquiescence

or opposition to authority or by efforts to gain peer

approval (or avoid peer rejection).”); Cohen, supra, at

363 (“Susceptibility to peer influence appears to in

crease between childhood and early adolescence,

peaks at about age fourteen, and then . . . decreases

into early adulthood.”).

the Legal Rights Provided by In Re Gault, 60 Rutgers L. Rev.

125, 158-59 (2007) (explaining that “perceived difference be

tween a sentence of five years and ten years is a lot less mean

ingful to a teen than to an adult”).

15

Thus, an attorney’s ability to develop a constitu

tionally effective relationship with a child client is

often impaired by the characteristics of youth.

II. Com prom ised A ttorney/C hild-C lient R ela

tion sh ip s H inder D efense C ounsel’s A bility

To Conduct a C onstitutionally A ppropriate

F actual Investigation .

As detailed above, the characteristics of youth

can significantly complicate the development of a

proper attorney-client relationship. An attorney’s

capacity to adequately investigate his child-client’s

case is directly affected by this compromised re la

tionship.

The duty to investigate is a vital component of

every defense attorney’s constitutional obligation to

his or her client. Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362,

395-96 (2000); Wiggins v. Sm ith, 539 U.S. 510, 522-

27 (2003); Strickland, 466 U.S. a t 690-91; see also

A.B.A. Standards for Criminal Justice: Prosecution

& Def. Function, Standard 4-3.2(a) (“[D]efense coun

sel should seek to determine all relevant facts known

to the accused . . . [a]s soon as practicable.”). A law

yer’s ability to conduct an adequate defense investi

gation is, in turn, dependent upon her ability to

communicate with the client.

Counsel’s actions are usually based, quite

properly, on informed strategic choices made

by the defendant and on information sup

plied by the defendant. . . . For example,

when the facts th a t support a certain poten

tial line of defense are generally known to

counsel because of what the defendant has

said, the need for further investigation may

16

be considerably diminished or elim inated al

together. . . . In short, inquiry into counsel’s

conversations with the defendant may be

critical to a proper assessm ent of counsel’s

investigation decisions, just as it may be

critical to a proper assessm ent of counsel’s

other litigation decisions.

Strickland, 466 U.S. a t 691 (citation omitted); see

also A.B.A. Standard for Criminal Justice: Prosecu

tion & Def. Function, Standard 4-3.2, cmt. (“The cli

ent is usually the lawyer’s prim ary source of infor

mation for an effective defense.”).12

“A trusting client is far more likely to reveal facts

and details th a t not only help in formulating the de

fense, but, in the absence of broad discovery rules,

help the attorney learn more about the prosecution’s

case.” Jan e t C. Hoeffel, Toward a More Robust

Right to Counsel of Choice, 44 San Diego L. Rev. 525,

541-42 (2007) (citing Morris, 461 U.S. a t 20-21). A

lawyer-client relationship characterized by suspicion

and m istrust will leave an attorney less likely to

learn critical facts and less able to provide effective

12 See also Upjohn Co. v. United States, 449 U.S. 383, 389

(1981) (the attorney-client privilege was developed “to encour

age full and frank communication between attorneys and their

clients” in recognition of the fact “that sound legal advice or

advocacy serves public ends and that such advice or advocacy

depends upon the lawyer’s being fully informed by the client.”);

Hunt v. Blackburn, 128 U.S. 464, 470 (1888) (“The rule which

places the seal of secrecy upon communications between client

and attorney is founded upon the necessity . . . of the aid of per

sons having knowledge of the law and skilled in its practice,

which assistance can only be safely and readily availed of when

free from the consequences or the apprehension of disclosure.”).

17

representation. Thus open communication is a nec

essary precursor to an adequate factual investigation

and “is well recognized by the courts and ethical

rules as ‘the cornerstone of the adversary system.’”

Hoeffel, supra, a t 541-42 (quoting Linton v. Perini,

656 F.2d 207, 212 (6th Cir. 1981)).

As described in Section I.A, supra, the communi

cation needed to shape counsel’s investigation can be

significantly precluded by a teenager’s na tu ra l m is

tru s t of adults. A child may be unwilling to share

relevant factual information regarding her case or

refuse to speak with her attorney at all, thereby n a r

rowing the scope and adequacy of counsel’s investi

gation.

Additionally, a child’s “ability to receive and

communicate information adequately . . . may be

compromised by im pairm ents in attention, memory,

and concentration,” and this can and often does im

pede an attorney’s capacity to elicit the information

necessary for a constitutionally adequate investiga

tion. Steinberg, supra note 2, a t 475. Specifically,

children may experience difficulty “responding] to

instructions or . . . providing] im portant information

to [counsel], such as a coherent account of the events

surrounding the offense.” Id.-, see also Kennedy v.

Louisiana, 554 U .S .___, 128 S. Ct. 2641, 2663 (2008)

(“The problem of unreliable, induced, and even imag

ined child testimony means there is a ‘special risk of

wrongful execution’ in some child rape cases.” (quot

ing Atkins, 536 U.S. a t 321)); Cohen, supra, a t 360

(explaining th a t youth inhibits counsel’s ability to

gather information from a child client).

18

Furtherm ore, as discussed in Section I.C, supra,

a child may, to her own detriment, place greater

value in protecting her peers or winning their ap

proval th an providing counsel with the factual in

formation necessary for appropriate investigative

efforts. See Julie W hitm an & Robert Davis, Snitches

Get Stitches: Youth Gangs and Witness Intim idation

in Massachusetts, The National Center for Victims of

Crime, 47 (2007) (detailing results of a study show

ing th a t “the idea of being viewed as a snitch was a

huge deterrent to reporting crime for youth” and

th a t “youth do not want to be labeled and rejected by

their neighbors or peers for snitching”).

A child’s failure to relate all necessary and rele

vant information to defense counsel can have devas

ta ting consequences for the outcome of her case.

When defense counsel is not provided with all of the

information necessary for an adequate investigation,

“the defendant can be harm ed by the inevitable n a r

rowing of vision when the full flexibility of disposi

tion is not considered.” Sheldon Krantz et ah, The

Right to Counsel in Criminal Cases: The M andate of

Argersinger v. Ham lin 184 (1976); see also Strick

land, 466 U.S. a t 691 (“[Cjounsel has a duty to make

a reasonable investigation or to make a reasonable

decision th a t makes particular investigations unnec

essary.”); Douglas L. Colbert et al., Do Attorneys

Really M atter?: The Empirical and Legal Case for

the R ight of Counsel at Bail, 23 Cardozo L. Rev.

1719, 1763, 1776 (2002) (explaining th a t those who

are held in pretrial detention “are more likely to be

convicted and to receive a harsher sentence than

people freed pending tria l,” largely because “the de

fense’s ability to locate witnesses is greatly en

19

hanced” when a client gains pretrial release since

“[m]any potential witnesses are more likely to coop

erate and provide information when the lawyer, an

unfam iliar face and frequently from a different race

and class background, is accompanied by someone

they know.”). Determ inative evidence may go undis

covered. Strategic decisions regarding the represen

tation will be lim ited by the disadvantage suffered

by counsel who is not privy to all the facts at issue.

Potentially viable defense theories may be discarded

because counsel lacks the factual clarity th a t a client

who was willing to communicate could provide. Ac

cordingly, for child defendants who have not fully

communicated all relevant information to counsel,

the chances of suffering an extremely harsh and po

tentially inappropriate sentencing outcome are sub

stantially increased.

III. Com prom ised Attorney/C hild-C lient Re

la tion sh ip s Can Yield F law ed D ecisions

to A ccept or Reject P lea Bargains.

Defense counsel’s diminished ability to obtain vi

ta l information from an adolescent client can also

have a profound impact on plea negotiations. In or

der to evaluate the appropriateness of a plea bar

gain, counsel m ust have a clear command of all rele

vant facts. Indeed, the American Bar Association

cautions th a t “[u]nder no circumstances should de

fense counsel recommend to a defendant acceptance

of a plea unless appropriate investigation . . . has

been completed . . . .” A.B.A. Standards for Criminal

Justice: Prosecution & Def. Function, S tandard 4-

20

6.1(b).13 As previously discussed, and for a variety of

reasons, children often struggle to convey informa

tion to counsel and may be unable or unwilling to

provide their attorney with all necessary facts and

information about their case. As a result, the ability

of both the attorney and client to effectively analyze

the appropriateness of a plea bargain is critically re

duced.

Additionally, a child client m ust fully understand

the conditions and obligations of a plea bargain as

well as the rights th a t will be waived. “A guilty plea

. . . is an event of signal significance in a criminal

proceeding. . . . [A]nd the high stakes for the defen

dant require ‘the utm ost solicitude.’” Florida v.

Nixon, 543 U.S. 175, 187-88 (2004) (quoting Boykin

v. Alabama, 395 U.S. 238, 243 (1969)). Criminal pro

ceedings th a t expose children to the possibility of a

life-without-parole sentence require the child defen

dant to take stock of a wide range of possible sen

tencing alternatives and consider the long-term con

sequences of decisions made during the adjudicatory

process:

13 See also Douglas A. Berman, From Lawlessness To Too

Much Law?: Exploring the Risk of Disparity from Differences in

Defense Counsel Under Guidelines Sentencing, 87 Iowa L. Rev.

435, 446 (2002) (“From the very outset of representation, a de

fense attorney needs to assess the range of possible trial and

sentencing outcomes for his client in order to properly craft an

effective defense strategy and evaluate the prospects for strik

ing a beneficial plea bargain.”); Lisa M. Farabee, Disparate De

partures Under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines: A Tale of

Two Districts, 30 Conn. L. Rev. 569, 576 (1998) (noting that a

“defense attorney is more likely to favorably affect his client's

sentence if he possesses,” inter alia, “good lines of communica

tion with his client”).

21

A defendant who enters . . . a [guilty] plea

simultaneously waives several constitutional

rights, including his privilege against com

pulsory self-incrimination, his right to tria l

by jury, and his right to confront his accus

ers. . . . [BJecause a guilty plea is an adm is

sion of all the elements of a formal criminal

charge, it cannot be tru ly voluntary unless

the defendant possesses an understanding of

the law in relation to the facts.

McCarthy v. United States, 394 U.S. 459, 466 (1969)

(citation and footnotes omitted). Thus, a child m ust

weigh costs and benefits, understand the quantum of

proof and caliber of evidence associated with particu

lar charges and evaluate the long and short-term re

percussions of all available options before deciding

w hether to go to tria l or enter a guilty plea.

As discussed in Section I.C, supra, a child’s ca

pacity to fully engage in this critical evaluative proc

ess is greatly reduced, relative to th a t of an adult,

because adolescents’ ability to conduct reasoned de

liberation regarding a plea offer may be diminished

by their impulsive and reckless nature and limited

tem poral perspective th a t often focuses on immedi

ate, ra ther than long-term, consequences.

A child’s ability to thoroughly consider a plea

bargain is also reduced by the simple fact th a t chil

dren possess significantly less practical knowledge

and experience to inform their choices and under

stand the consequences of a guilty plea or trial than

adults. Puritz, supra, at 474; Clarke, supra note 2,

a t 694 (“As a class, adolescents are likely to have less

knowledge and experience to draw on in making de-

22

cisions than adults.”). The values and experiences

th a t drive a teenager’s choices are grounded upon

characteristics th a t are not as established or static

as those of adults. Melinda Schmidt et al., Effective

ness of Participation as a Defendant: The Attorney-

Juvenile Client Relationship, 21 Behav. Sci. Law

175, 179 (2003). Unlike an adult, the experiences,

values, and priorities th a t a child will rely on in

evaluating the desirability of a plea bargain are

likely to change because teenagers are still in the

process of m aturation. Thus their decision-making is

likely to be very different from th a t of an adult.

Schmidt, supra, a t 179-80.

The barriers of tru s t described in Section I.A, su

pra, also affect the attorney’s ability to properly

counsel a child about a plea offer. “A good lawyer

tries to persuade his client to plead guilty when, in

his or her professional opinion, a plea will produce a

better outcome. . . . If the [child] client does not tru st

his lawyer, the client’s instincts will tell him to fight

the lawyer at every step. Representation, and likely

the outcome, will suffer.” Hoeffel, supra, a t 542

(footnotes omitted); see also Scott, Evolution, supra,

a t 171 (footnotes omitted) (explaining th a t “[h]ow de

fendants respond to attorneys’ advice and weigh the

consequences of their choices in the tria l process

may be affected by psychosocial factors such as peer

and adult influence, tem poral perspective, and risk

preference and perception,” and these factors “might

influence youths’ judgm ents about the value of ac

cepting plea bargains and of waiving im portant

rights in the legal process”).

23

Even in those instances when children heed their

attorney’s advice, the questionable reasoning and

judgm ent a child may employ in reaching a decision

to accept or reject a plea bargain is also a source for

concern. The potential problem can m anifest itself

in one of two ways: (1) as discussed in Section I.A,

supra, a child may reject, out of hand, an attorney’s

recommendation regarding a plea bargain because

she is inclined to reject any advice offered by an

adult or authority figure; or (2) the child may fail to

take on the requisite directive role in the attorney-

client relationship due to her socialization to let

adults make decisions for her. See Scott, Develop

mental Incompetence, supra, a t 824 (noting th a t in a

recent study of psychosocial influences on adolescent

decision-making regarding plea offers, “75% of the

eleven- to thirteen-year-olds, 65% of the fourteen- to

fifteen-year-olds, and 60% of the sixteen- to seven-

teen-year-olds recommended accepting the plea of

fer,” compared to the “evenly divided” responses of

young adults, thus suggesting “a much stronger ten

dency for adolescents than for young adults to make

choices in compliance with the perceived desires of

authority figures”); see also Grisso, supra, a t 19

(“[T]he process of achieving autonomy and a sense of

identity often takes the adolescent through phases in

which others’ values play a strong role in his or her

choices. At times this will be manifested in extreme

deference to others’ judgments . . . , while at other

times choices may be made primarily in opposition to

others’ preferences.”). W hether a youth rebels

against the judgment of adult actors, exercises a

strict fidelity to the views of others, or acts in a way

th a t combines or contradicts both of these methods

of decision-making, children are forced to find an ap

24

propriate balance between their own feelings of dis

tru s t in the system and reliance on counsel. In

reaching th is balance a young person often acts to

her own detrim ent, ensuring th a t the ultim ate result

is an exceedingly complicated and often deficient re

lationship w ith counsel. See generally Thomas

Grisso et al., Juveniles’ Competence to S tand Trial: A

Comparison of Adolescents’ and A du lts’ Capacities as

Trial Defendants, 27 L. and Hum. Behav. No. 4, 333,

357-361 (2003) (discussing influence of authority fig

ures on adolescent decision-making).

At bottom, children facing the possibility of a life

without parole sentence m ust engage in the daunt

ing task of weighing a m ultitude of complex factors

in order to reach a decision about a plea bargain tha t

may have perm anent and lifelong consequences.

The compromised attorney/child-client relationship

combined with the characteristics of youth and other

factors yield a strong likelihood of error in th is criti

cal decision-making process. See Pinard, supra, note

11 at 1121 (“[Gjiven the studies th a t have found both

th a t juveniles do not understand the various phases

of the criminal process and they cannot fully com

prehend long-term consequences (or tend to ignore

these consequences in favor of immediate conse

quences), serious questions should arise as to

whether juveniles can adequately consider, weigh

and understand these consequences when analyzing

the m erits of entering a guilty plea.”).

For children subject to life without parole sen

tences, a faulty plea decision can result in a veritable

death sentence with no hope for a life outside of

prison.

25

IV. Com prom ised A ttorney/C hild-C lient Re

lation sh ip s Can Contribute to C hildren

F acing Inappropriately Harsh Prison

C onditions.

For the reasons detailed above, a reduced capac

ity to develop and sustain a meaningful attor-

ney/client relationship can play a critical role in in

appropriate sentence outcomes. This concern is p a r

ticularly salient in the context of extreme sentences

where children may not only receive severe and

perm anent sentences th a t fail to accurately reflect

culpability, but also where children, once sentenced,

are likely face unique suffering in adult prison.14

This circumstance further demonstrates the inap

propriateness of juvenile life without parole sentenc

ing.

“Adolescents in adult institutions have a rela

tively low and weak position in the social hierarchy

of prison, and physical vulnerability to attack ac

companies their low status.” Jeffrey Fagan, This

Will Hurt Me More Than It Hurts You, 16 Notre

Dame J. L. Ethics & Pub. Pol’y 1, 22 (2002). Conse

quently, when compared to adults, children in the

adult institutions are “eight times more likely to

commit suicide, 500 times more likely to be sexually

assaulted and 200 times more likely to be beaten by

staff than adults.” Amanda M. Kellar, They’re Just

14 A majority of states (31) house transferred youth offend

ers in adult correctional facilities. Bishop, Juvenile Offenders,

supra, at 138. “Florida leads the nation in incarcerating chil

dren between the ages of thirteen and seventeen in adult pris

ons.” Paolo G. Annino, Children in Florida Adult Prisons: A

Call for a Moratorium, 28 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 471, 471 (2001).

26

Kids: Does Incarcerating Juveniles With Adults Vio

late the Eighth A m endm ent?, 40 Suffolk U, L. Rev.

155, 171 (2006) (citing Jeffrey Fagan, Juvenile Ju s

tice Policy and Law: Applying Recent Social Science

Findings to Policy and Legislative Advocacy, 183

PLI/Crim. 395, 407-08 (1999) (citing an American

Bar Association study comparing violence juveniles

face to violence adults face)). Unfortunately, trad i

tional attem pts to protect children in adult prison

often fail because isolation in protective custody ex

cludes the child from educational and other pro

gramming activities. Bishop, Juvenile Offenders,

supra, a t 146.

Thus, the adult “correctional setting becomes the

environm ent for social development” during an ado

lescents’ most “formative period of development,”

thereby “stun t [ing] the development of cognitive

growth and psychosocial m aturity . . . [and] likely

exacerbating] ra ther than am eliorating] many of

the very factors th a t lead juveniles to commit crimes

in the first place (mental illness, difficulties in school

or work and . . . psychological im m aturity).”

Steinberg, supra note 2, a t 478, 480.

While these problems affect children in adult

prison regardless of their sentence, they take on a

qualitative difference for those young people who

have no hope of ever escaping the violence of their

surroundings.

27

CONCLUSION

The characteristics of youth may always present

a potential barrier to effective representation by

counsel and contribute to unfair criminal justice out

comes. Given the severity and finality of juvenile life

without parole sentencing, the ways in which com

promised attorney/child-client relationships can con

tribute to unreliable sentencing outcomes supports

the significant constitutional concerns raised by Pe

titioners and their other supporting amici. This

Court should therefore conclude th a t life without pa

role sentences for offenders under age 18 at the time

of their offense violates the Eighth Amendment.

Respectfully submitted,

J ohn Payton

Director-Counsel

Debo P. Adegbile

Christina Swarns

J in Hee Lee

*Vincent Southerland

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

* Counsel of Record

Charles J. Ogletree, J r .

Robert J. Smith

Charles Hamilton Houston

28

Institute for Race &

J ustice

125 Mt. Auburn St., 3rd Floor

Cambridge, MA 02138

J effrey L. F isher

National Association of

Criminal Defense Lawyers

1660 L St., NW, 12th Floor

W ashington, DC 20036

J uly 23,2009