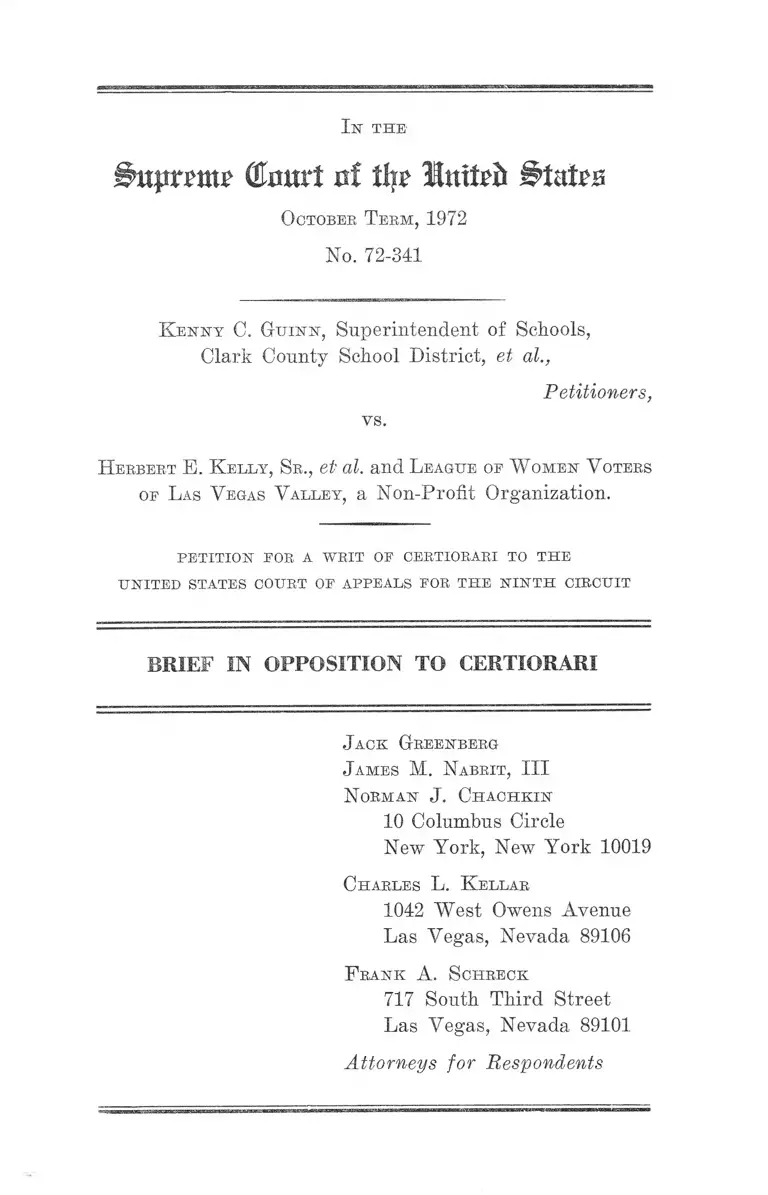

Guinn v. Kelly Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Guinn v. Kelly Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1972. 62bcdfef-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5d5cdad5-7908-4fbc-a26b-8565318c888b/guinn-v-kelly-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

1st th e

Bxtpxmx (Umtrt nl % Wmtxb States

O ctober T erm , 1972

No. 72-341

K e n n y C. Gu in n , Superintendent of Schools,

Clark County School District, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

H erbert E. K elly , Sr., et al. and L eague of W om en V oters

of L as V egas V alley , a Non-Profit Organization.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman J . Ch a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

C harles L. K ellar

1042 West Owens Avenue

Las Vegas, Nevada 89106

P rank A. S chreck

717 South Third Street

Las Vegas, Nevada 89101

Attorneys for Respondents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PA G E

Opinions Below......................................... ..................... 1

Jurisdiction ................................................... - ..........-.... 1

Questions Presented ...................-............ -................... 2

Statement ........................................... -.........................—- 2

Statement of Facts ................. ......................... - --------- 3

R easons. W h y t h e W rit S hould B e D enied ...... -........— 6

Conclusion ......... ...................-................... -.................... U

Appendix A .............................................-...................... la

T able of A u tho rities

Cases:

Brewer v. Scliool Bd. of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir.

1968) ..........................-....................-..................-....... - 10

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ...........- 8

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Ind. School Disk, 5th Cir.

No. 71-2397 (August 2, 1972) ------- ------ ------ ------- 10

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 426 F.2d 1035

(8th Cir. 1970) ............. - 10

Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs of Mobile County,

430 F.2d 883 (5th Cir. 1970), rev’d in part, 402

U.S. 33 (1971) _______- ..........................................- 9

Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp. 734

(E.D. Mich. 1970), aff’d 443 F.2d 573 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971) ...... —-................ 10

11

PAGE

Deal v. Cincinnati Bel. of Educ., 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir.

1966), cert, denied, 389 TJ.S. 846 (1967), 419 F.2d 1387

(6th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 962 (1971) .... 9

Ellis y. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County,

465 F.2d 878 (5th Cir. 1972) ................ ....................... 10

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.,

409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied.-, 396 U.S. 940

(1969) ..................................................... .................... 10

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) .... 4

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, No. 71-507 (argued

October 11, 1972) ..................... .................................. 8

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsbor

ough County, Civ. No. 3554-T (M.D. Fla., May 11,

1971) ........................................................... ................ 10

Sloan v. Tenth School Dist. of Wilson County, 433 F.2d

587 (6th Cir. 1970) ...................................................... 10

Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (D.N.J. 1971),

aff’d 404 U.S. 1027 (1972) .............................. ......... 9

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S.

1 (1971) - ....— .....— .............................................passim

United States v. Board of Educ., 429 F.2d 1253 (10th

Cir. 1970) .................... ............................................ . 10

United States v. School Dist. No. 151, 286 F. Supp. 786

(N.D. 111. 1966), aff’d 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968),

301 F. Supp. 201 (N.D. 111. 1969), aff’d 432 F.2d 1147

(7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 943 (1971) ..... 10

1st t h e

j ^ u j i r m ? C o u r t o f % I m t r f o S t a t e s

October T erm, 1972

No. 72-341

K enny C. Guin n , Superintendent of Schools,

Clark County School District, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

H erbert E. K elly, Sr., et al. and L eague oe W omen V oters

oe L as Vegas Valley, a Non-Profit Organization.

PETITION EOB A WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS EOB THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Ninth Circuit which affirmed the district court’s deseg

regation order is now reported at 456 F.2d 100. The dis

trict court opinions and orders herein are unreported and

are reprinted in the Appendix to the Petition.

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of the Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1254(1). The judgment of the Court of Appeals

denying rehearing was entered on April 3, 1972. On June

3, 1972, Mr. Justice Douglas extended the time for filing

the Petition to and including August 31, 1972.

2

Questions Presented

1. When school authorities by conscious choice make

decisions affecting the location, grade structure and ca

pacity of school buildings, the size and perimeters of

attendance zones by which students are assigned to these

schools, and the assignment of faculties and staffs to those

schools, all of which result in the maintenance and in

crease of racially identifiable and segregated schools, does

the absence of an explicit state-wide mandate compelling

such segregation render the school authorities’ actions

lawful ?

2. May a federal district court devising a remedy for

Fourteenth Amendment violations in accord with the prin

ciples of Swann v. Gharlotte-Mecklenhurg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971), require—where there are no practical

difficulties of the sort envisaged in Swann—that the plan

be designed so as to avoid assignment of more than 50%

black students to any school in a system wherein black

students make up only a small proportion of the total

student population?

Statement

This school desegregation action was commenced against

the Clark County School District, Nevada, in 1968. Fol

lowing a hearing and finding of illegal segregation, the

district court retained jurisdiction and permitted the school

board to attempt to comply with its responsibility to elim

inate that segregation by implementing an open enroll

ment or free choice plan. In 1970 the court reviewed

progress under the plan at an evidentiary hearing and

ordered adoption of new measures incorporating manda

tory assignment of pupils to the end that no Clark County

3

district school should be more than 50% black. (With re

spect to faculty, the court held that injunctive relief was

not required because the board had adopted policies which

promised effectively to redress the previous disproportion

ate assignment of black teachers to black schools in the

district).

Following' this Court’s decision in Swann, supra, the dis

trict court reconsidered its decision in light thereof pur

suant to a remand from the Court of Appeals for that

purpose, and reaffirmed its holding that the Clark County

School District was constitutionally obligated to desegre

gate its schools. The Court of Appeals affirmed, holding

that the guidelines in Swann had been properly applied.

Statement of Facts

At the time this lawsuit was filed, some 4,978 black stu

dents attended six westside Las Vegas elementary schools,

each of which was over 95% black in student enrollment

(10/68 Tr. 199, 388, 412; DX 17)1 and each of which had

a faculty disproportionately black in comparison to other

schools in the system DX 16). The students attending

these schools vTere, on the average, a year behind the

students attending predominantly white Las Vegas schools

in achievement test scores (10/68 Tr. 413; 5/69 Tr. 48).

At the secondary level there was no school in which

similar numbers of black students were concentrated. A

predominantly black westside junior high school had been

closed in 1956 (10/68 Tr. 200) and its students dispersed

to other schools in the system (10/68 Tr. 150-51). At that

time as well, some of the now-black westside elementary

1 Citations are to the original record before the Court of Appeals,

which respondents have requested be transmitted to this Court.

Transcript citations are identified by page and date of hearing.

4

schools had significantly larger white enrollments (e.g.,

10/68 Tr. 200). However, although the white and black

school population of the district subsequently grew about

the same rate, black students at the elementary level were

increasingly isolated in heavily black westside elementary

schools.

There were, of course, a variety of factors which brought

about this result. Housing in the Las Vegas area was

tightly segregated and Negroes were generally confined to

the west side,2 a fact known to the school authorities (10/68

Tr. 73, 220, 258, 451; 8/70 Tr. 83). Yet the district closed

schools on the fringe areas of the westside Negro com

munity (6/71 Tr. 100-01) and replaced them with new ele

mentary schools built in the heart of black areas (10/68

Tr. 201; 5/69 Tr. 302). At the same time, federally as

sisted low-income housing projects on the west side swelled

the impaction of black residents {e.g., 10/68 Tr. 251, 314-

15; 8/70 Tr. 1601; cf. 8/70 Tr. 50); it has been only very

recently that such projects have begun to be located out

side the traditionally black westside area (6/71 Tr. 70-71).

The school district claims to have been following a

“neighborhood school policy” in these matters, merely re

sponding to the demands of local growth in determining

both its site locations and its school attendance policies.

However, it is significant that at the time of the hearings

there were only six “neighborhood” schools in the Las

Vegas area to which no students were bused; five of these

were black, westside elementary schools (6/71 Tr. 237, 239).

Under the district’s attendance plan, considerable numbers

of white students were transported to school buildings

2 Nevada passed an open housing statute in 1970 (6/71 Tr. 48),

two years after the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968 went into

effect. See also Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968).

But the effects of racially discriminatory housing practices are

longstanding. See 10/68 Tr. 221.

5

other than those closest to them (5/69 Tr. 121; 8/70 Tr.

221; 6/71 Tr. 237), including white students being trans

ported to white schools and by-passing one of the black

west side schools (5/69 Tr. 96, 122-23; 6/71 Tr. 301; see

10/68 Tr. 428-29).

The school district says it did not take the racial effect

of its school construction policies into account until 1966

when it determined to build no more black schools on the

west side3 (10/68 Tr. 330, 354); however, its new facilities

have generally not been filled to capacity when they open

(10/68 Tr. 163; 8/70 Tr. 394) and school construction

generates increased settlement in the immediate area (10/68

Tr. 372, 379; 5/69 Tr. 258). In the context of residential

segregation in Las Vegas, therefore, the district’s con

struction policies made the situation worse. As recently

as 1969, the district was building a new school in a white

suburb to relieve overcrowding at nearby white schools

(5/69 Tr. 107-08) although black schools were underutilized

(10/68 Tr. 143, 168-69).

The school district also helped to create and maintain

the pattern of racially identifiable schools by restricting

the transfer right of black students at the westside schools

(10/68 Tr. 80, 254) and by failing to utilize yearly attend

ance zone changes to increase desegregation (compare

10/68 Tr. 163, 8/70 Tr. 367 with 6/71 Tr. 301). Tradition

ally it has assigned its few black elementary teachers to

the westside schools (e.g., R. 115); the district had never

assigned a black teacher to a white school before 1969

(after this action was filed) (10/68 Tr. 438). The school

district recently has undertaken an extensive renovation

program at the westside schools in order to “make them

8 Jo Mackey Elementary opened in 1965 and C.V.T. Gilbert in

1966 (10/68 Tr. 142, 151).

6

equal to other schools in the District . . . ” (10/68 Tr. 354;

8/70 Tr. 229).

Reasons Why the Writ Should Be Denied

The School Board’s primary contentions in support of

its request for review of this matter seem to he that the

courts below wrongly decided factual issues concerning the

responsibility of school authorities for segregation in Clark

County and that the decision is in conflict with rulings of

other Courts of Appeals.

In its Statement of the Case and in general throughout

the Petition, the District attempts to characterize its opera

tions as merely following a neutral, neighborhood school

doctrine. The courts below explicitly held that this was not

the case in Las Vegas:

This is a clear finding that the school board furthered

racial segregation by official conduct beyond the mere

adoption and administration of a neutral, neighborhood

school policy, [footnote omitted] This finding is sup

ported by the record, and establishes a constitutional

violation.

456 F.2d at 106 (Appendix to Petition at p. 10). The Court

of Appeals reviewed the findings of the district court which

justified the conclusion that Clark County school authori

ties knowingly took actions which resulted in the establish

ment, maintenance, or aggravation of segregated schools

on the westside of Las Vegas. See 456 F.2d at 106-08

(Appendix to Petition at pp. 10-13). Additional evidence

relied upon by the plaintiffs was not directly used by the

Court of Appeals to buttress its conclusion because the

district court had not made findings thereon, but examina

tion of the record will make apparent the solid basis upon

7

which the district court made its finding of constitutional

violation. See 456 F.2d at 105, n.4 (Appendix to Petition

at p. 7).4

There is some language in the opinions of the district

court which is ambiguous because it employs the “de facto”

school segregation terminology. The Court of Appeals

properly viewed the lower court’s order as being grounded

upon a correct interpretation of the law as enunciated by

this Court in Swann, supra, irrespective of the terminology

employed. See 456 F.2d at 106, n.6 (Appendix to Petition

at p. 9).

The arguments in the Petition can be reduced to the

simple assertion—which the District in fact made below—

that the Constitution applies only to States which com

pelled segregation by statute. But such statutes merely

make the proof of state-created segregation relatively sim

ple; they do not delimit the reach of the equal protection

clause. “De jure” segregation can still be proved—as in

this case—by showing official action resulting in segrega

4 Attached to this Brief as Appendix A we have reproduced a

Supplemental Brief filed following oral argument below, which

describes some of the evidence demonstrating how this school dis

trict

since Brown, closed schools which appeared likely to become

racially mixed through changes in neighborhood residential

patterns . . . [and built] new schools in the areas of white

suburban expansion farthest from Negro population centers

in order to maintain the separation of the races with a mini

mum departure from the formal principles of “neighborhood

zoning.”

Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 21. The Supplemental Brief also dis

cussed the construction of new black schools in areas of black con

centration and the drawing of attendance boundaries so that the

new schools continued to serve only that part of the school district

formerly served by the older black schools, and the school system’s

failure, while it “continually adjust [ed] attendance boundaries of

schools” (Petition, p. 11) to ameliorate racial segregation in Las

Vegas schools.

8

tion or discrimination in the absence of statute, as such

discrimination can be proved in, for example, jury dis

crimination cases. Thus, Swann cannot be read in the

narrow way that the District suggests. This Court was, of

course, dealing with segregation originally imposed pur

suant to statute. But the lengthy discussion of issues such

as school placement, attendance zones, and faculty ratios

makes it clear that constitutional violations arise by school

board actions that create or perpetuate segregation even in

the absence of a statute.

This case involves a school district in which segregation

has been brought about and maintained by regular, sys

tematic and deliberate choice of the school authorities.

While the district court may have labelled the school

system’s stubborn adherence to a “neighborhood school

policy” in the black westside schools (R. 513), or its delib

erate construction of new “neighborhood” (and conse

quently black) schools in that area (R. 514), “de facto”

segregation (10/68 Tr. 501) because neither had Nevada

law ever required segregation nor had the school district

ever openly advocated it as formal policy, the lower court’s

order was specifically grounded upon the official action of

the school district in maintaining and aggravating segre

gation long after Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483

(1954) (R. 514; Appendix to Petition at p. 26).

Not only are Petitioners seeking to controvert factual

findings clearly supported by the record, but they have

conjured up non-existent conflicts with the decisions of

other Courts of Appeals in an effort to create issues merit

ing the review of this Court. For example, in Keyes v.

School District, No. 1, Denver, No. 71-501 (argued October

11, 1972), the Denver school system made the same argu

ment advanced by the Petitioners below respecting segre

gation of its Park Hill area schools: that it followed a

9

neighborhood school policy which required it to construct

new schools in this region of increasing black population

despite the availability of classroom space elsewhere in the

system. The Denver district court held that the reasonably

foreseeable result of the policies knowingly adopted by the

school board—segregation—imposed upon the Board the

constitutional obligation to eliminate that segregation. The

Court of Appeals affirmed on this issue and this Court has

not acted upon the school board’s cross petition for cer

tiorari as to this matter, No. 71-572. The standard applied

by the district court and the Tenth Circuit in Denver is

precisely the standard applied by the courts below in mea

suring the constitutionality of the Clark County School

District’s policies and practices resulting in segregation.

As we noted above, the courts below specifically found

that the Clark County School District authorities were not

innocently pursuing a neutral, neighborhood school policy

which resulted in racial imbalance in existing schools solely

because of population changes. That distinguishes this

case from Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Educ., 369 F.2d 55 (6th

Cir. 1966), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 846 (1967), 419 F.2d 1387

(6th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 962 (1971) and Spen

cer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (D.N.J. 1971), aff’d 404

U.S. 1027 (1972), in each of which there was no finding that

segregation resulted from the actions of school authorities.

The Fifth Circuit cases cited at pages 21 and 22 of the

Petition, as purportedly giving rise to a conflict among the

Circuits, were all decided prior to this Court’s ruling in

Swann, supra, and their limited remedies are insufficient

under the principles of Swann. Indeed, these decisions

were relied upon in Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs of

Mobile County, 430 F.2d 883, 889 (5th Cir. 1970), rev’d in

part, 402 U.S. 33 (1971), and the limited desegregation

plans they approved have been altered since Swann, Com,-

10

pare Ellis v. Board, of Public. Instruction of Orange County,

465 F.2d 878 (5tli Cir. 1972); Mannings v. Board of Public

Instruction of Hillsborough County, Civ. No. 3554-T (M.D.

Fla., May 11, 1971).

The Courts of Appeals are in agreement that actions

such as those of the Clark County School District which

perpetuate or result in school segregation violate the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution. Davis v. School

Dist. of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp. 734 (E.D.Mich. 1970), aff’d

443 F.2d 573 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971);

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Ind. School Dist., 5th Cir., No.

71-2397 (August 2, 1972); United States v. School Dist. No.

151, 286 F. Supp. 786 (N.D. 111. 1966), aff’d 404 F.2d 1125

(7th Cir. 1968), 301 F. Supp. 201 (N.D. 111. 1969), aff’d 432

F.2d 1147 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 943 (1971);

cf. Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir.

1968); Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School

Dist., 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied 396 U.S. 940

(1969); Sloan v. Tenth School Dist. of Wilson County, 433

F.2d 587, 589 (6th Cir. 1970); Clark v. Board of Educ. of

Little Rock, 426 F.2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970), 449 F.2d 493

(8th Cir. 1971); United States v. Board of Educ., 429 F.2d

1253 (10th Cir. 1970).

There is no singular issue in this case which merits the

attention of this Court.

11

CONCLUSION

W h erefo re , for the foregoing reasons, Respondents pray

that the Writ be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N a b r ii, III

N orman J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

C harles L. K ellar

1042 West Owens Avenue

Las Yegas, Nevada 89106

P rank A. S ohreck

717 South Third Street

Las Yegas, Nevada 89101

Attorneys for Respondents

APPENDIX

l a

APPENDIX A

I n the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob the N inth Cibcuit

No. 71-2332

HERBERT E. KELLY, SR., et al.,

v.

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

KENNETH GUINN, Supt. of Schools,

Clark County School District, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

No. 71-2340

HERBERT E. KELLY, SR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

KENNETH GUINN, Supt. of Schools,

Clark County School District, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

No. 71-2422

HERBERT E. KELLY, SR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

KENNETH GUINN, Supt. of Schools,

Clark County School District, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

[Cross-Appeals]

APPEAL FEOM TH E UNITED STATES DISTBICT COUET

POE TH E DISTBICT OP NEVADA

2a

S u pplem en ta l B rief for P la in tiffs

Pursuant to leave granted by the panel at the oral argu

ment in this matter on November 11, 1971, plaintiffs file

this Supplemental Brief explaining in detail the use made

of the various maps in the record by plaintiffs’ counsel at

the oral argument. We are also taking’ the opportunity in

this format to provide the Court with the citations to the

two cases mentioned by counsel for plaintiffs at oral argu

ment which were not contained in the brief.

I

With respect to a possible theory that black faculty mem

bers were assigned to black schools because the district

felt black students should be provided with role models

whom they could emulate, counsel for plaintiffs mentioned

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960).

Counsel for plaintiffs also mentioned this Court’s deci

sion holding segregation imposed by administrative action

without the sanction of state law unconstitutional in West

minster School District of Orange County v. Mendez, 161

F.2d 774 (9th Cir. 1947).

II

The following comments about the maps in the record

relate to subjects discussed at the oral argument and are

elaborated in detail for the convenience of the Court.

One of the subjects at issue in this case is the construc

tion by the school district in 1965 and 1966 of the black

Gilbert and Mackey Elementary Schools. It is instructive

in considering this matter to examine the 1964-65 zoning

map for the Highland Elementary School found at page

61 of the record, the 1965-66 zoning maps for the Highland

and Mackey Elementary Schools found at page 113 of the

record, and the 1966-67 map of the zones for Highland,

3a

Gilbert and Mackey found at page 116 of the record.

Enrollment statistics by race for each school are avail

able only for the 1964-65 (record at p. 50) and 1966-67

(record at p. 114) school years. Although the comparison

is made more difficult because the 1964-65 zoning maps are

photocopies of street maps with individual zones deline

ated by cross-hatching, while the 1965-66 and 1966-67 maps

are schematic, it is apparent from a comparison of the

three maps mentioned above that the area presently served

by Highland (subsequently renamed Booker), Gilbert and

Mackey is essentially the same area served by Highland

Elementary alone in 1964-65. During’ that year the record

shows that Highland had an enrollment of 1,014 black

students at 46 “other” (white) students. The map at page

61 of the record very clearly shows the northern boundary

of the Highland zone to have run along Cheyenne xivenue

from the railroad tracks on the east to Simmons Street on

the west (the Xerox copy of the map in the record does

not show the entire street name, but an arrow pointing

to the western boundary of Highland running south from

its intersection with Cheyenne can be seen and part of

the words Simmons Street are visible). The zone runs

south to Smoke Ranch Road (again the entire street name

is not visible, but the last e of Smoke and the word Ranch

can be made out) over to Tuning and south to Lake Mead

Boulevard. The zone then takes in the entire area north

of Lake Mead Boulevard and east to the railroad tracks

except for a small area at the eastern edge which is

marked “Valley View Estates.” Examination of the rec

ord at page 73, showing the zone for Matt Kelly Elemen

tary shows the disposition of that small area north of

Lake Mead Boulevard and south of Miller Avenue, west

of the railroad tracks and east of Revere.

Comparing the original Highland zone with the maps at

pages 113 and 116 of the record, the first striking fact

4a

revealed is that the northern boundary line for Highland,

Gilbert or Mackey has consistently been drawn along Chey

enne Avenue. At the same time, Gilbert, Mackey and High

land have remained black schools while Lois Craig, the ele

mentary school serving the area north of Cheyenne, has

been predominantly white. In 1964-65 when Lois Craig

served a large area north of Cheyenne as well as a small

area between Simmons and the Thunderbird Air Field,

south to Cartier (record at p. 71), it enrolled 725 white

students and 32 black students (record at p. 50). In 1965-

66, it served essentially the same area. In 1966-67, it served

virtually the same area but lost to C.Y.T. Gilbert the small

space between Simmons and the Air Field; it actually lost

a few black students in the process, enrolling 389 white

students and 44 black students. Thus, the comment in the

Reply Brief of the school board that Mackey was so located

as to provide for future growth north of Cheyenne Avenue

(page 6 of Reply Brief) is belied by the school district’s

practice of drawing a rigid boundary between the black

area south of Cheyenne and the predominantly white area

north of Cheyenne.

In 1966-67 Lois Craig was considerably below its capac

ity, enrolling 433 students compared to its 1964-65 enroll

ment of 757. Yet no black students residing south of Chey

enne Avenue between the railroad tracks and the air field

were assigned to Lois Craig nor were white students north

of Cheyenne assigned to either Gilbert or Mackey. Instead,

whites living north of Cheyenne near the air field, who are

obviously much closer to Gilbert or Mackey, travelled all

the way east to Lois Craig. In 1966-67 Gilbert enrolled 516

blacks and only 5 whites, Mackey 761 blacks and no whites,

and Lois Craig 389 whites and 44 blacks.

Except for the addition of the area between Simmons and

the air field to Gilbert, all of the zone changes necessitated

by the construction of Gilbert and Mackey took place within

5a

the original Highland zone which was overwhelmingly

black. Not surprisingly, three schools which now served

that area, instead of one, became racially identifiable as

black schools. There was no extension of the Lois Craig

zone south or vice versa. There was no adjustment in the

zones for other black schools, Kelly, Carson, Madison and

Westside, despite the construction of Gilbert and Mackey

to relieve the pressure on Highland.

The effect of closing Washington and Jefferson Elemen

tary Schools was also discussed at the oral argument. We

refer the Court in this connection to the 1964-65 zoning

maps for Washington (record at p. 92), Jefferson (record

at p. 62), Kit Carson (record at p. 68), and McCall (rec

ord at p. 88) Schools as well as to the 1966-67 zoning maps

(record at p. 116).

In 1964-65, the Kit Carson zone extended from Lake

Mead Boulevard to West Owens between the railroad

tracks and Holmes Street (record at p. 68) just as it did

in 1966-67 (record at p. 116). In 1964-65 Carson enrolled

719 blacks and 14 whites. The McCall School in 1964-65

served an area south of Evans and Cartier between the

railroad tracks on the west and the Las  egas Boulevard

on the east but extending only south to Lake Mead Boule

vard (record at p. 80). At that time it enrolled 514 whites

and no black students. The area between the railroad tracks

and Las Vegas Boulevard south of Lake Mead Boulevard

was served in 1964-65 by the AVashington School (record at

p. 92). It enrolled 185 whites and 9 blacks (record at p. 50).

The Jefferson Elementary School had a zone just east of

AVashington and east of Las Vegas Boulevard (record at

p. 62) enrolling 196 whites and no blacks (record at p. 50).

After Washington and Jefferson were closed at the same

time as new capacity was made available west of the rail

road tracks by the construction of the Gilbert and Mackey

6a,

Schools, the zone for Kit Carson or Westside, black schools,

was not extended to the east across the railroad tracks to

integrate either facility. Instead the McCall zone was ex

tended southward below Lake Mead Boulevard (record at

p. 116). In 1966-67 McCall enrolled 512 whites and 42

blacks. Had Washington or Jefferson been retained, the

Superintendent testified that in 1968 they would have been

about 50% black (October, 1968 transcript, p. 201). It is

further clear that opportunities for desegregation at Car-

son and Westside presented by the closing of Washington

and Jefferson were not taken.

The maps also assisted in visualizing one of the examples

mentioned in oral argument of the way in which white

students have been assigned to white schools even if closer

to black schools. The 1964-65 map for Highland Elemen

tary (record at p. 61) shows an area south of Smoke Ranch

Road, north of Lake Mead Boulevard and west of Turning

which is much closer to the Highland School than most of

the northeast portion of the zone. However, it is excluded

from the zone. The zoning map for the McWilliams Ele

mentary School for the same year (record at p. 67) shows

that the area referred to next to the Highland School has

been obviously gerrymandered into McWilliams; in 1964-

65, McWilliams enrolled 989 white students and no blacks

while Highland enrolled 1,014 blacks and 46 whites (record

at p. 50). The 1966-67 map (record at p. 116) shows the

same area cut out of the Gilbert zone and the map on page

119 of the record shows that that area is zoned to McWil

liams, a school located so far west that it cannot be shown

on the map. Obviously students from that area are bused at

the school district’s expense to McWilliams, which in 1966-

67 enrolled 843 whites and 19 blacks while Gilbert enrolled

516 whites and 5 blacks (record at p. 114). Hr. Lawrence

confirmed that this white area has historically been zoned

away from the closest black school, either Highland or

7a

Gilbert, and transported to McWilliams or Ronzone (June,

1971 transcript, p. 301-02).

Plaintiffs greatly appreciate the opportunity to elucidate

for the Court what the inspection of the maps in the record

showTs. We regret that because of the short time available

to work with the maps we were unable to include these

detailed verbal descriptions in our main brief.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219