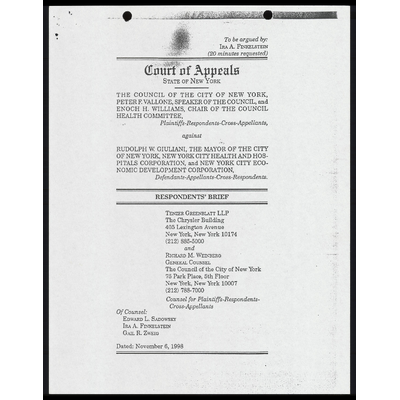

Respondents' Brief

Public Court Documents

November 9, 1998

24 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Campaign to Save our Public Hospitals v. Giuliani Hardbacks. Respondents' Brief, 1998. ff5dde50-6835-f011-8c4e-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5d6a266f-6965-495b-885d-5ea05903458c/respondents-brief. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

To be argued by:

IrRA A. FINKELSTEIN

(20 minutes requested)

@ourt of Appeals

STATE OF NEW YORK

THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK,

PETER F. VALLONE, SPEAKER OF THE COUNCIL, and

ENOCH H. WILLIAMS, CHAIR OF THE COUNCIL

HEALTH COMMITTEE,

: Plaintiffs-Respondents-Cross-Appellants,

against

RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI, THE MAYOR OF THE CITY

OF NEWYORK, NEWYORK CITY HEALTH AND HOS-

PITALS CORPORATION, and NEW YORK CITY ECO-

NOMIC DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION,

Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Respondents.

RESPONDENTS’ BRIEF

TENZER GREENBLATT LLP

The Chrysler Building

405 Lexington Avenue

New York, New York 10174

(212) 885-5000

and

Ricuarp M. WEINBERG

GENERAL COUNSEL

The Council of the City of New York

75 Park Place, 5th Floor

New York, New York 10007

(212) 788-7000

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Respondents-

Cross-Appellants

Of Counsel: ii

Epwarp L. Sapowsky

IrA A. FINKELSTEIN

Ga R. Zweic

Dated: November 6, 1998

TABLE OF CONTENTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE «Bin aida le Fa hie dB vain wins

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF QUESTIONS PRESENTED .... .. . . cue iunivan sane

ADDITIONAL BACTS as. ov os iminiainis 1 ah aie vm Fa wae a

GENESIS: AND STATUARY PURPOSE OF THE HHC . ..... 0 svi uv

THE MAYOR'S PRIVATIZATIONPLAN .. .. 0 i lh a dmdis ss

ARGUMENT i Py EIN bw a

POINT I: THE HHC ACT DOES NOT AUTHORIZE THE DIVESTITURE OF THE

HHC'S STATUTORY OBLIGATIONS . ... i ani vin viva ate + date,

POINT II: ASSUMING THE SUBLEASE IS AUTHORIZED UNDER STATE LAW

THE CONSENT OF THE CITY. COUNCIL ISREQUIBED .'...... cc...

POINT III: ASSUMING THE SUBLEASE IS AUTHORIZED BY STATE LAW, THE

PROPOSED SUBLEASE IS SUBJECT TO NEW YORK CITY'S UNIFORM

LAND USE REVIEW. PROCEDURE ("ULURP"Y . . uv vis inion vain slain aia

CONCLUSION = cetera ai ia, oo Es a be nails

- i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Conner v. Cuomo, :161 Misc. 2nd 389 (Sup. C1. Kings Co. 1998) . . . ........ ovis 18

Ferres v. City of New Rochelle, 68 N.Y.2d 446 (1084) .... .. . o.oo viii vo wwii ida 8

Giuliani v.Hevest, SONNY 2A 27 (1097). cvs vi A i al iim nn Ss 3. 11

Murer of Gallagherv. Regan, 42 NXY.20: 377 Q977) 7... os hile a iif wi dais vw inieivi a 12

Matter of Long v. Adirondack Park Agency, 76 N.Y.2d 416

(1900). i a a, i Te BI, 10

ro EMO RAE ET SG LOT lie WB 17,18

New York City Health and Hospital Corp. Goldwater Mem. Hosp.

v. Gorman 113 Misc. 2nd 33, 488 N.Y.S. 2nd 623

(Sup. Ct.NY Co. 1082) om ea ow a RII Cn da EO 7

NYC Board of Estimate v. Morris, 4859 1).8. 688 (1989)... ... 0 ihe im, 7

People. Ryan, 274 NX, 1491937) i. i. aad ERT OS 8

Tribeca Community Ass’n v. N.Y.S. Urban Development Corp

200 AD. 2nd 336,607 N.Y.S. 2nd 18 (Ist Dept. 1994) vo voi vw od vain ints 18

STATUTES

New York City Charter

Bi at Th ae LE Ts 7.13, 16

YL Eee li Ti I Ce eon IES at lea SRE ON 4,16

ae CRE 0 RE TR SS Se ee SE 14

nk SORE EL OE Gey CR et 3 Vee SO Te WO Se (La See i 15

$3040 i eS aa RT ee ET 15

0 TT BI Cl PUB aE ES A 17

|

|

NL RYU ORS ST ee mat pig MR dT ET 2

B38) i TE ee a Te a eile ae + ea Ea a 7, 8,9

CRRA EC ED 2 OW 0 ERS i ELT SP rel BRE ns Se CE 6

§ 7385

JO) vi ee i a I RT 9.11,12..13, 14. 15

[BO oi. vo, a EE i aa ee ae 20

§ 7386

[la ar a i EE LE ee a 5

[LY i. eo tie ps die ee, ne BT Te i Le SE Be o

§ 7387

Dna eile ETE Ll We I ES TEN ORT A, OE ERE 9

[1] on ar rt Ns te Re Le Ln 10, 19

McKinney's Session Laws of New York

S ASOT ER BR BE ale Th SE RL GS Sh 5

COURT OF APPEALS

STATE OF NEW YORK

Case No. 97-01337

THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK,

PETER F. VALLONE, SPEAKER OF THE

COUNCIL, and ENOCH H. WILLIAMS, CHAIR

OF THE COUNCIL HEALTH COMMITTEE,

Plaintiffs-Respondents-Cross-Appellants,

-against-

RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI, THE MAYOR OF THE

CITY OF NEW YORK, NEW YORK CITY HEALTH

AND HOSPITALS CORPORATION, and NEW YORK

CITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION

Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Respondents.

RESPONDENTS' BRIEF

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The principal issue in this appeal is whether state law or the New York City Charter

authorize the Mayor of the City of New York to privatize the municipal hospitals by executive fiat--

without a fundamental amendment of the governing law by the State Legislature, or approval by the

New York City Council.

i

27350 1

The issue is not, as the appellants contend, whether privatization of the City’s hospitals

i a more desirable way of providing health care to the City's residents, and particularly it’s poor, but

whether such a radical change in the provision of health services may be accomplished without

legislative action either at the state or local level.

The New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation (“HHC”), a public benefit

corporation formed at the request of the City with the express mandate to operate and manage the

municipal hospitals, is dominated and controlled by the Mayor through his appointive powers. When

the Mayor proposed to surrender the operation of Coney Island Hospital for a minimum of 99 years by

leasing it to a private, for-profit company, the HHC quickly acceded to his request.

The HHC was created by the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation Act,

McKinney's Unconsolidated Laws of New York (“U.L.”) §7381 ef seq.(the “Act”). The appellants are

incorrect in arguing that the State Legislature, when it created the HHC in 1969, anticipated that at some

future time that the HHC would conclude that the public would be better served by the transfer by sale

or lease of operating control of the hospitals from the HHC to private companies and expressly provided

for that possibility. The courts below correctly held that the Mayor's “privatization” proposal is ultra

vires. because it is directly contrary to the declarations of purpose and intent as set forth in the Act, as

well as the statements of intent contained in its legislative history. The provision of the Act that the

appellants contend authorizes the privatization of the municipal hospitals does no such thing, and

nothing in the Act authorizes the HHC to abdicate its statutory obligation to operate the hospitals for

the public benefit.

“Privatization” is the word used by the appellants to describe the transactions. See Affidavit of Dr. Luis

Marcos, President and CEO of the HHC. (R. 37-50 at 42)

—

—

—

—

—

A —

——

——

-

S

—

—

—

—

The portion of the Act upon which the appellants mistakenly rely requires the consent

of the Board of Estimate of any determination by the HHC to dispose of real property under its terms.

Such consent acts as a legislative check upon the power of the Mayor. The Board of Estimate no longer

exists, because it was a legislative body whose voting structure was declared unconstitutional. The City

Council has succeeded the Board of Estimate as the sole legislative body of the City. However, the

Mayor, having proposed the privatization plan and negotiated the sublease, now presumes that he

succeeded to the powers of the Board of Estimate under the Act and hence that he alone is the

appropriate party to sit in review of his own proposal. The Mayor assures the Court in his brief that he

will “review the sublease and make an independent determination ...regarding whether to approve its

terms.” (Appellants Br. pp.35-36)

Finally, the appellants engage in a form of double speak when they argue that the Mayor

has the sole power to approve a decision to dispose of City property, and at the same time urge that it

isnot City property at all for purposes of legislative review by the City Council under the City Charter’s

Uniform Land Use Procedure.

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF QUESTIONS PRESENTED

BY THE APPEAL AND BY THE CROSS-APPEAL

1. The Health and Hospitals Corporation was created with the express statutory

mandate to provide health and medical services and health facilities under the direction and control of

New York City. The Governor's memorandum approving the bill stated that the purpose of for the

creation of the HHC was to operate and maintain the City's municipal hospitals. The HHC was

proposed by the then Mayor of the City with a statement, on the legislative record, that in proposing the

HHC. the City was “not getting out the hospital business.” May it now be argued that the HHC Act

Qnsg

authorizes the HHC., a public benefit corporation, to divest itself of the hospitals, defease the HHC's

bonds issued in connection therewith, and transfer the operation of the hospitals to private entities?

Both the trial court (R. 616-640) and the Appellate Division (R. 646-651) decided that

such an action would violate the express statutory and legislative intent, and thus would be ultra vires.

2 Assuming that such privatization of the City hospitals is not ultra vires, did the

State Legislature intend that the New York City hospitals could not be privatized without local

legislative review?

The trial court decided this question in the affirmative. The Appellate Division stated

that it was not necessary to reach the issue because of its conclusion that the privatization plan was not

authorized under the HHC Act.

3. Assuming that the privatization plan is not ultra vires, are the City hospitals

property of the City whose disposition requires review under the City Charter's Uniform Land Use

Review Procedure (New York City Charter, Section 197-c)?

The trial court decided this question in the affirmative. The Appellate Division stated

that it was not necessary to reach the issue because of its conclusion that the HHC Act did not authorize

the privatization plan.

ADDITIONAL FACTS

Appellants omit from their statement of facts matters that are material to the disposition

of this appeal.

GENESIS AND STATUTORY PURPOSE OF THE HHC

The HHC, created in 1970, was proposed in 1969 by the then Mayor of the New York

City, John V. Lindsay, as a corporate mechanism to aid the City in better operating and managing the

City hospitals. The Mayor. in his message to the Governor (which is included in the Bill Jacket as a

statement of the legislative intent for passage of the HHC Act), stated that under the proposed

legislation “The municipal and health care system will continue to be the City's responsibility governed

by policies determined by the City Council, the Board of Estimate, the Mayor, and the Health Services

Administration on behalf of and in consultation with the citizens of New York City.” (R, 131)

Specifically, the then-Mayor wrote:

In establishing a public benefit corporation. the City is not getting out of

the hospital business. Rather it is establishing a mechanism to aid it in

better managing that business for the benefit not only of the public

served by the hospitals but the entire City health service system.

(emphasis supplied) (R.131)

The State Legislature declared that the operation of the hospitals was an essential public

and governmental function (McKinney's Uncons. Laws of NY § 7382). It specifically mandated that

the HHC and the City enter into an agreement whereby the HHC “shall operate” the hospitals for the

benefit of the City and its residents who can least afford medical services. (U.L. § 7386[1](a)) The City

and the HHC ultimately entered into such an agreement (R. 133-156).

Governor Rockefeller's memorandum approving the legislation stated that the provision

of adequate health facilities was a major responsibility of government (Governor's mem. approving

L 1969, Ch. 1016, (1969 McKinney's Session Laws of N.Y, at 2569).

THE MAYOR'S PRIVATIZATION PLAN

New York's present Mayor has publicly stated that he intends to overturn the statutory

scheme not merely for Coney Island Hospital, but for all of New York City's acute care hospitals

(R.638). He intends, therefore, to take the City and the HHC out of the business of operating hospitals.

Kanisy 5

27350.

The Mayor plan calls for the privatization of the City-owned municipal hospital system

by means of a long-term “transfer of the management and operation” of the hospitals (R. 528) from the

HHC to private operators by means of a “sublease.” (See Form of Sublease for Coney Island Hospital,

R. 401- 470Z The HHC, therefore, would no longer be the primary mechanism by which the City

provides health care services to its residents. The sublease of Coney Island Hospital to a private

operator for 99 years (renewable by the operator for an additional 99 years), coupled with defeasing that

portion of the HHC’s bonds relating to the facility, was the first such transfer, with the ultimate goal

being that the HHC (and thus the City) would get out of any responsibility for operating the City

hospitals.

To implement his proposal, the Mayor, acting on his own initiative through defendant

EDC retained J.P. Morgan Securities Co. (“J.P. Morgan”) to put the first three City hospitals on the sale

block (R. 167-171) by means of an offering memorandum. (R. 187-252) The Mayor then stated

publicly:

Twenty years from now the mayor of New York City will not be

standing here with New York City owning 11 acute-care hospitals. That

will not be the case. (National Public Radio, Interview with Mayor

Giuliani, Morning Edition September 5, 1995.) (R. 638)

The appellants concede, as they must, that privatization of the hospitals is the Mayor's

mitiative. that the marketing of the hospitals through elaborate private offering memoranda by J.P.

Morgan was undertaken at the Mayor's initiative, that the proposed transaction and sublease were the

Mayor's creations, and that the Mayor negotiated the sublease for Coney Island Hospital.

27380 1

The Mayor. therefore, not only proposed the privatization of the hospitals, but because

he dominates and controls the HHC Board by appointment,” effectively brought about the HHC’s rapid

approval.

The provision of the Act upon which the appellants rely for the proposition that the

sublease 1s authorized by the statute requires approval of the disposal by the HHC of any of its real

property. That provision expressly requires legislative consent by the Board of Estimate. The Board

of Estimate was abolished by local referendum after the Supreme Court declared its voting structure

unconstitutional. NYC Board of Estimate v. Morris, 489 U.S. 688 (1989). The City Charter now

provides that the City Council is the City’s sole legislative body:

In addition to the other powers vested in it by this charter and

other law, the council shall be vested with the legislative power of the

City.

(City Charter § 21)

ARGUMENT

POINT I.

THE HHC ACT DOES NOT AUTHORIZE THE DIVESTITURE OF

OF THE HHC'S STATUTORY OBLIGATIONS TO PRIVATE COMPANIES

The HHC s express corporate purpose is to operate, manage, superintend and control the

City's public hospitals, and to provide such services in its health and hospital facilities. (U.L. § 7382

and § 7385(8]); New York City Health and Hospitals Corp. Goldwater Mem. Hosp. v. Gorman, 113

In effect, eleven of sixteen members of the Board are appointees of the Mayor. The Chair of the HHC is

designated by the Mayor. Four other members, serving ex officio, are heads of City agencies appointed by

the Mayor and five are designated by the City Council. The remaining director is the chief executive officer

of the HHC chosen by the other 15 directors (U.L. § 7384).

Misc.2d 33, 448 N.Y.S.2d 623 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1982). This purpose 1s declared to be “the

performance of an essential public and governmental function.” (U.L. § 7382)

In creating the HHC the State Legislature, in the Act’s “Declaration of policy and

statement of purposes’ provided:

It is further found, declared and determined that hospitals and

other health facilities of the City are of vital and paramount concern and

essential in providing comprehensive care and treatment for the ill and

infirm, both physical and mental, and are thus vital to the protection and

the promotion of the health, welfare and safety of the people of the state

of New York and the city of New York.

(U.L. §7382.)

The same section of the Act further provides:

It is found, declared and determined that in order to accomplish the

purposes herein recited, to provide the needed health and medical

services and health facilities, a public benefit corporation, to be known

as the New York City health and hospitals corporation, should be created

to provide such health and medical services and health facilities and to

otherwise carry out such purposes; that the creation and operation of the

New York City health and hospitals corporation, as hereinafter provided,

is in all respects for the benefit of the people of the state of New York

and of the city of New York, and is a state. city and public purpose; and

that the exercise by such corporation of the functions. powers and duties

as hereinafter provided constitutes the performance of an essential public

and governmental function.

(Id: emphasis supplied)

Since Mayor Lindsay, Governor Rockefeller and the State Legislature in proposing the

creation of the HHC specifically reaffirmed the City’s role in operating the hospitals, it requires nothing

less than a violent distortion of the legislative framework and intent to reach the conclusion that the

right to privatize may be somehow wrung out of the legislative language and intent. In reaching the

conclusion that HHC has no authority to effectuate the Coney Island Hospital transaction, the courts

below simply applied the guidelines of statutory interpretation recognized by this Court, the foremost

smong them being that the determination of whether any such authority exists begins with the language

of the enabling statute. Giuliani v. Hevesi, 90 N.Y.2d 27 (1997). Further, the courts followed the

principle, as defined by this Court, that in interpreting a statute “the spirit and purpose of the act and

the objects to be accomplished must be considered [and] the legislative intent is the great and

controlling principle.” Ferres v. City of New Rochelle, 68 N.Y.2d 446, 451 (1984), quoting People v.

Ryan, 274 N.Y. 149, 152 (1937).

The appellants, passing over the clear statements of intent both in the Act an in the

accompanying statements of legislative intent, incorrectly rely upon only one provision, § 7385[6],

which authorizes the HHC to

dispose of by sale, lease or sublease, real or personal property, including

but not limited to a health facility, or any interest therein for its corporate

purposes. . . .

(emphasis supplied).

Since the HHC s corporate purpose is to operate hospitals and provide medical services,

it would appear self-evident that casting off that obligation is not a corporate purpose.

Whether or not the purpose or effect of the instant sublease is to “dispose” of Coney Island Hospital,

nothing in § 7385[6] authorizes the delegation by the HHC of its corporate obligation to operate the

hospitals. The appellants” position would eviscerate the HHC's essential corporate purpose, as set forth

mn its “Declaration of Policy and Statement of Purposes” (U.L. § 7382) and elscwhere in the statute,

which is to operate and maintain the hospitals. See, e.g., § 7386[1][a] (“Relationship to the City”):

The city shall . . . enter into an agreement or agreements with the

corporation, pursuant to this section and section [7387], whereby the

corporation shall operate the hospitals then being operated by the city .

(emphasis supplied). See, also, U.L. § 7386[1](b).

Qrsg y 9

{7350 1

The appellants attempt to overcome this impediment by arguing that since § 7387[4] of

the Act authorizes the HHC to sell or lease a hospital when it is no longer required for its corporate

purposes, this must mean that a long-term operating lease to a private company is a corporate purpose

within the meaning of § 7385[6].

This argument misconstrues both the statute and the statements of legislative intent. The

HHC Act authorized the City to lease all of its hospitals to the HHC “for its corporate purposes, for so

long as [the HHC] shall be in existence.” (U.L. § 7387[1]). From this and other statements of intent

within the HHC Act. the Appellate Division opined that “[t]he Legislature clearly contemplated that

the municipal hospitals would remain a governmental responsibility and would be operated by HHC

as long as HHC remained in existence.” (App. Div. Op., p. 4; R. 649).

The true purpose of § 7385[6] is explained by another subdivision of the same section.

Section 7386[20](a) authorizes the HHC

to exercise and perform all or part of its purposes, powers, duties,

functions or activities through one or more wholly-owned subsidiary

public benefit corporations. . . .

This provision further provides that any such subsidiary corporations may be “established for the

purpose of operating a health facility or the delivery of direct patient care. . . .”

The legislature thus anticipated that each of the hospitals might better be operated as a

free-standing public hospital instead of being under one umbrella. It therefore follows that

notwithstanding the provisions of subsection [6] of the same section authorizing the HHC to “dispose”

of real property, under subsection [20](a) the HHC may not delegate to a private corporation, by

sublease or otherwise, its statutory obligations to operate the hospitals. This provision makes sense

in terms of the overall purposes of the statute, because it ensures that even if an operating health facility

10

ARE LIIS

i subleased, the HHC will continue to exercise full control of the operation of the facility by reason of

the fact that the lessee is a wholly-owned subsidiary public benefit corporation.

As the Appellate Division recognized below, courts may not read particular words of

astatute in isolation to reach a construction that is contrary to the overall statutory purpose and scheme,

but should construe the statute as a whole and read all parts together to determine the legislative intent.

Matter of Long v. Adirondack Park Agency, 76 N.Y.2d 416,420 (1990). Thus the courts below correctly

held that given the prominent and specific provisions of the HHC Act, including its declarations of

legislative intent and purpose, the appellants cannot find authority from § 7385[6] for the transaction

in issue here.

The Hevesi case, supra, involved the authority of the Mayor to sell the New York City

water system to the City Water Board and to finance the transaction through bonds to be issued by the

Water Finance Authority. After a careful review of the statute authorizing the issuance of bonds by the

Finance Authority, this Court concluded that the statutory authority to issue bonds to pay for water

projects did not contemplate a situation where such bonds would be used as a device to transfer

ownership of the entire water system. Id. 90 N.Y.2d at 39-40.

Similarly here, a statutory provision generally authorizing the HHC to "dispose" of real

property by lease or sublease “for its corporate purposes” cannot provide a basis for the appellants’

position that the HH(' has the power to divest itself of those very same corporate purposes.

It could not have been the intent of the legislature that among the corporate purposes and

powers of the HHC is the sale of its birthright.

As the Appellate Division observed below:

The purpose and intent of the [HHC Act] was to establish one entity

accountable to the public to operate the municipal hospitals for the

benefit of the public. A construction of section 7385[6] of the [Act]

11

ABKE 3 4

which would permit the defendants to turn over the operation of an entire

hospital to a private entity by means of a 99-year sublease would be

inconsistent with that intent and purpose.

(App. Div. Op.. p. 4; R. 649; emphasis in the original)

The appellants argue that the HHC will continue to have “regulatory oversight” of the

privately owned hospitals. This, however, is contrary to the provisions of § 7386[20](a), which require

full control by HHC of an operating hospital through a subsidiary public benefit corporation.

Regulatory oversight is not the same as operating authority and responsibility. The City also regulates

plumbers, electricians and home improvement contractors. This can hardly be construed as meaning

that the City is in the plumbing, electrical or the home improvement business. Moreover, the HHC Act

specifically requires more than regulatory oversight; it requires that the hospitals act in accordance with

policies and plans adopted by the City. If the policies or plans of the City were to change, however, the

HHC would be unable to rescind or modify the sublease between the HHC and the private company for

either the 99-year initial term, or the 99-year renewal term (a period of time coterminous with 49

mayoral administrations).

The appellants’ description of the Coney Island transaction as a routine sublease under

§ 7385[6] 1s beyond credulity. This transaction, transferring the operation of a hospital until the year

2196. cannot be for the HHC's “corporate purposes’ under this Section, because the HHC's corporate

purpose 1s to operate the hospital, either by itself or through a wholly owned public benefit subsidiary.

The term of the proposed sublease far exceeds any possible useful life of the buildings and

improvements currently existing. That this is no mere sublease is further established by the reality that

the HHC must defease or tender for the corresponding portion (approximately $43,500,000) of the

bonds that were issued in connection with the HHC's assumption of operating responsibility for the

hospitals, such amount to be paid by the private company. (R.. 114)

12

I

RELI 3

The courts below properly held that the sublease at issue in this case, which transfers

tom the HHC to a private operator the responsibility for the operation of the hospital for a term

potentially equal to one-fifth of the next millennium, exceeded the HHC's powers under the Act. In so

holding. they correctly concluded that such a transaction cannot be accomplished absent an amendment

ofthe Act, inasmuch as only the Legislature has the authority to create, modify, dissolve or increase the

powers of a public benefit corporation. See Matter of Gallagher v. Regan, 42 NY2d 230 (1977) (“[A]

legislative act of equal dignity and import” is required to modify a statute, and “nothing less than

another statute will suffice.”)

The appellants’ assertion that they should be permitted to “adapt” the method of delivery

of health care services to the people of the City, in order to respond to changes in the field of health care

delivery misses the point. The HHC Act was enacted in response to the City's request for legislative

assistance in dealing with a fiscal and operational crisis facing the City-owned hospitals. If the

appellants are correct that a new and different crisis now presents itself that was not foreseen at the time

the Act was passed into law, then the obvious remedy is, as the Appellate Division held, to “apply to

the Legislature to amend the statute to confer such authority upon HHC, as only the Legislature has the

authority to create, modify, or dissolve a public benefit corporation.” (App. Div. Op., R. 650)

POINT II

ASSUMING THE SUBLEASE IS AUTHORIZED UNDER STATE

LAW THE CONSENT OF THE CITY COUNCIL IS REQUIRED

Under the HHC Act, disposals of real property by the HHC require the consent of the

now extinct Board of Estimate and the mayor (U.L. § 7385[6]; § 7387). Since the City Council has

succeeded to the legislative powers of the Board of Estimate, any such sublease requires its approval.

13

i850.

ne State Legislature intended to subject any plan for the disposal of City-owned hospitals -- a matter

;o vital to the public -- to local legislative review and consent. Nonetheless the appellants argue that

aly the Mayor's approval is required for the sweeping privatization program — and the fundamental

sunge in the way health care is provided — that he himself proposed. This assertion, if accepted,

would frustrate the clear intent of the Legislature.

The City Council, not the Mayor, has succeeded to the legislative powers of the Board

of Estimate. The present City Charter provides that the Council is the sole legislative body of the City

(City Charter § 21). The Charter further provides that

The powers and responsibilities of the board of estimate, set forth

in any state or local law, that are not otherwise devolved by the terms of

such law, upon another body. agency or officer shall devolve upon the

body, agency or officer of the city charged with comparable and related

powers and responsibilities...

(City Charter § 1152(e)). Thus any disposal of real property pursuant to § 7385[6] requires City

Council approval. Any vestige of doubt on this issue is dispelled by § 197-d of the City Charter which,

when read with § 1152(e), expressly confers on the City council the final land use review powers

formerly vested in the Board of Estimate.

The Mayor asserts. however. that he now stands in the shoes of the Board of Estimate

with respect to the provisions of the HHC Act that require Board of Estimate consent to an HHC

decision to disnose of a hospital. (U.L. § 7385[6]) The appellar.ts argue that when the State Legislature

provided that any sale or lease of a City hospital would be subject to legislative consent by the Board

of Estimate, it had the prescience to anticipate that one day such consent could be frustrated by a

judicial finding of unconstitutionality, resulting in the abolition of the Board of Estimate and the

redistribution of its powers. Appellants thus argue that only the Mayor's approval is required for the

sweeping privatization program -- and the fundamental change in the way health care is provided -- that

he himself proposed.

Itis undisputed that the proposed sublease was negotiated and crafted by the Mayor. The

appellants. passing over this fact, blithely assert that the Mayor will “review the sublease and make an

independent determination pursuant to Unconsolidated Laws §7385[6] regarding whether to approve

isterms.” (Appellants' Brief, pp. 35-36)

The Legislature expressly provided, in the same section 7385[6] of the Act upon which

the appellants’ rely, for review and consent by an independent legislative body of any proposal by the

HHC to dispose of real property. Whether or not “the State Legislature gave the Mayor the

responsibility in setting hospital health care policy” or “recognize[d] the primacy of the Mayor in the

oversight of HHC [through] Mayoral appointees” (Appellants' Brief, pp. 34-36), the State Legislature,

in giving review power to the Board of Estimate, could not have intended that the Mayor be empowered

toreview and consent to his own proposals to dispose of the municipal hospitals. Such an interpretation

would make a mockery of the legislative intent.

Appellants’ convoluted argument begins with the City Charter provision in effect at the

time the HHC Act was adopted which provided for the approval by the Board of Estimate of any

disposition of City property (Charter § 384). Appellants next urge that when the Charter was revised

to eliminate the Board of Estimate, the same language was used in the Charter, except that the Mayor

was substituted for the Board of Estimate.

Appellants conclude that when the State Legislature created the HHC it simply tracked

the language of the City Charter as it then provided. This, of course, is not strictly the case. The

Charter provides for “approval,” while the HHC Act § 7385[6] uses the word “consent.” The different

usage. although not great, at least indicates that the drafters of the HHC Act were not writing with a

15

| copy of Charter § 384(a) by their side. Furthermore, the revision of the Charter was not made by the

| sate Legislature, but rather by a local referendum. It may not be presumed, therefore, that the State

Legislature, when it created the public benefit corporation, intended to be bound by a vote in the City

of New York relating to a general redistribution of City's governmental powers.

Finally, Charter § 384 applies only to the disposition of property which the City no

longer requires. This is clear from its mandate that the property may be sold or leased only for the

highest marketable price or rental at public auction or by sealed bids. Charter § 384[b]. The sublease

of Coney Island Hospital in issue here was a negotiated transaction and, since the hospital is going to

continue to operate as a health facility, it obviously is not property which the City no longer requires.

The approval of this privatization plan, and the long-term disposition of City hospitals

to a private corporation pursuant to such plan, involves a major shift in public policy. Such approval

is prototypical legislative action, formerly within the power of the Board of Estimate. Even if the

Mayor 1s correct in asserting that the HHC Act authorizes the HHC and the City to get out of the

hospital business, the law requires, and sound public policy demands, that such a decision be subject

to truly independent legislative review and approval by the City Council, which is the City's sole

legislative body. (New York City Charter, §21).

POINT III

ASSUMING THE SUBLEASE IS AUTHORIZED BY STATE LAW,

THE PROPOSED SUBLEASE IS SUBJECT TO NEW YORK CITY'S

UNIFORM LAND USE REVIEW PROCEDURE

The appellants argue that the Mayor now has the sole power to approve this disposition

of City property, and at the same time urge that it is not City property at all for the purposes of the New

York City Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (“ULURP”).

16

30.1

All dispositions of City property are subject to ULURP, which applies to the use,

development or improvement of any real property subject to city regulation and applies specifically to

the lease or other disposition of any of the City's real property (City Charter § 197-c[10]).

ULURP ensures community, borough and, ultimately, City Council involvement in land

use decisions.

Appellants argue, however, that while Coney Island Hospital "was once the real property

of the City" (Appellants' Brief p. 25), it is no longer because the City has leased it to the HHC. They

assert that a “leasehold interest is real property in and of itself” (Appellants' Brief p.27). The

appellants’ argument is both a bad reading of the law of real property and inconsistent with the argument

they make with respect to § 386 of the City Charter. In the first place, a leasehold is not real property,

but only an interest in real property, i.e., in the classical language of Anglo-American law, an estate in

land subject to defeasance. Ifthe State Legislature were to abolish the HHC, the City's lease to HHC

would terminate (R. 135-136, §1.1) and the land and City hospitals on them, as they always have been,

would continue to be the property of the City.

Furthermore, under ULURP there is no difference between disposition of a fee interest

by the City and a leasehold interest by the HHC. Nothing in Section 197-c of the City Charter limits

the ambit of ULURP to dispositions by the City of its real property; rather, it is applicable to any

dispos’.ons of the real property of the City.

The fallacy in appellants’ argument is underscored by the fact that on the one hand they

argue that under the HHC Act the source of the Mayor's power to consent to the proposed sublease is

§384 of the City Charter, which relates only to the disposition of City property, and on the other hand,

they argue that the property is not City property for the purposes of the ULURP sections of the very

same City Charter. The appellants cannot have it both ways.

17

50.1

Apparently appreciating the weakness of the argument, appellants therefore claim that

“[e]venifthe literal terms of ULURP were applicable to the sublease,” the State Legislature, by creating

the HHC. indicated an “overriding State interest” requiring “ignoring its strictures.” (Appellants' Brief

p. 27). In this connection, the appellants rely on Matter of Waybro Corp. v. Board of Estimate, 67

NY2d 349 (1986). That reliance is misplaced. As the trial court found, a reading of Waybro leads to

a result directly contrary to the appellants’ argument, and in fact supports the respondents’ position.

The issue in Waybro was the application of ULURP to a redevelopment project under

the auspices of the Urban Development Corporation (“UDC”). The UDC, like the HHC, had been

formed prior to the advent of ULURP. This Court ruled that in order to determine whether ULURP

applied. it was necessary to examine the legislative intent in forming the UDC. This Court found that

despite the “salutary and important purpose” of ULURP, its provisions would not apply if the State

Legislature expressly intended otherwise. This Court examined the UDC Act and noted that the UDC

had been given specific authority to override any city policy or procedure, such as ULURP It

concluded. therefore, that, because of this express language, ULURP did not apply to the UDC.

No such statutory override language appears in the HHC Act. Quite to the contrary, the

HHC's actions are expressly made subject to the City's policy and plans (§ 7386[7]). There is nothing

tn the HHC Act which even remotely suggests that the HHC is empowered to override any City policy.

18

a

~

Cal -

5q.

Accordingly, under this Court's analysis in Waybro, ULURP applies to the proposed transaction,’ as

lower courts have held with respect to other statutes that do not contain the UDC language’.

Finally, contrary to appellants’ assertion that the proposed sublease implicates only the

HHC leasehold interest and not the City's fee interest, the proposed sublease would affect the City's fee

interest. With an initial lease term of at least 99 years, renewable for another 99 years, it is no mere

sublease. because it involves a disposition by HHC of greater rights than it has under either its lease

from the City or under the HHC Act, both of which authorize the lease of the hospitals by the City to

the HHC for a term “co-existent with the life of the HHC.” (R. 135) (§ 7387[1)]) This 198 year

conveyance, disguised as an mere sublease, not only substantially affects the City's property interest;

it also affects the use of the property within the jurisdiction of ULURP.

Such a hospital “sublease” (going far beyond any realistic lease term for operating a

hospital facility, going far beyond any possible useful life for the existing buildings and improvements

on the property, and extending potentially for a period nearly as long as this Country has been in

existence) clearly affects the City's fee interest, and thus constitutes a disposition of real property of and

by the City. subject to ULURP.

Decisions relied upon by appellants involving dispositions of property by the UDC, e.g., Tribeca

Community Ass'n., Inc. v. N.Y.S. Urban Dev. Corp., 200 A.D.2d 536, 607 N.Y.S.2D 18 (1st Dep't), app.

dism., 83 N.Y.2d 905, 614 N.Y.S.2d 387, Iv. to app. Denies the allegations of paragraph., 84 N.Y .2d 805,

618 N.Y.S.2d 7 (1994), are, therefore, sui generis and inapplicable to statutes such as the HHC Act that

contain no similar override provisions.

See, Connor v. Cuomo, 161 Misc.2d 889 (Sup. Ct. Kings Co. 1998) (ULURP applies because the

FDC was not empowered to override ULURP.)

19

CONCLUSION

The order of the Appellate Division should be affirmed. In the alternative, the trial

court's alternative findings that City Council consent and/or ULURP are required should be reinstated.

Dated: New York, New York

November 9, 1998

Respectfully submitted,

TENZER GREENBLATT LLP

0

Ira A. Finkelstein

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Respondents

The Chrysler Building

405 Lexington Avenue

New York, New York 10174

(212) 885-5000

- and-

RICHARD M. WEINBERG, ESQ.

General Counsel

The Council of the City of New York

75 Park Place, 5th Floor

New York, New York 10007

(212) 788-7000

Of Counsel:

Edward L. Sadowsky

Ira A. Finkelstein

Gail R. Zweig

£onsg.p 20