Vulcan Society of Westchester County, Inc. v. Fire Dept. of the City of White Plains Plaintiffs Joint Memo of Law in Support of Approval

Public Court Documents

May 28, 1980

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Vulcan Society of Westchester County, Inc. v. Fire Dept. of the City of White Plains Plaintiffs Joint Memo of Law in Support of Approval, 1980. 9aec9b22-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5d771325-1dfe-4232-be24-533518bfaad8/vulcan-society-of-westchester-county-inc-v-fire-dept-of-the-city-of-white-plains-plaintiffs-joint-memo-of-law-in-support-of-approval. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

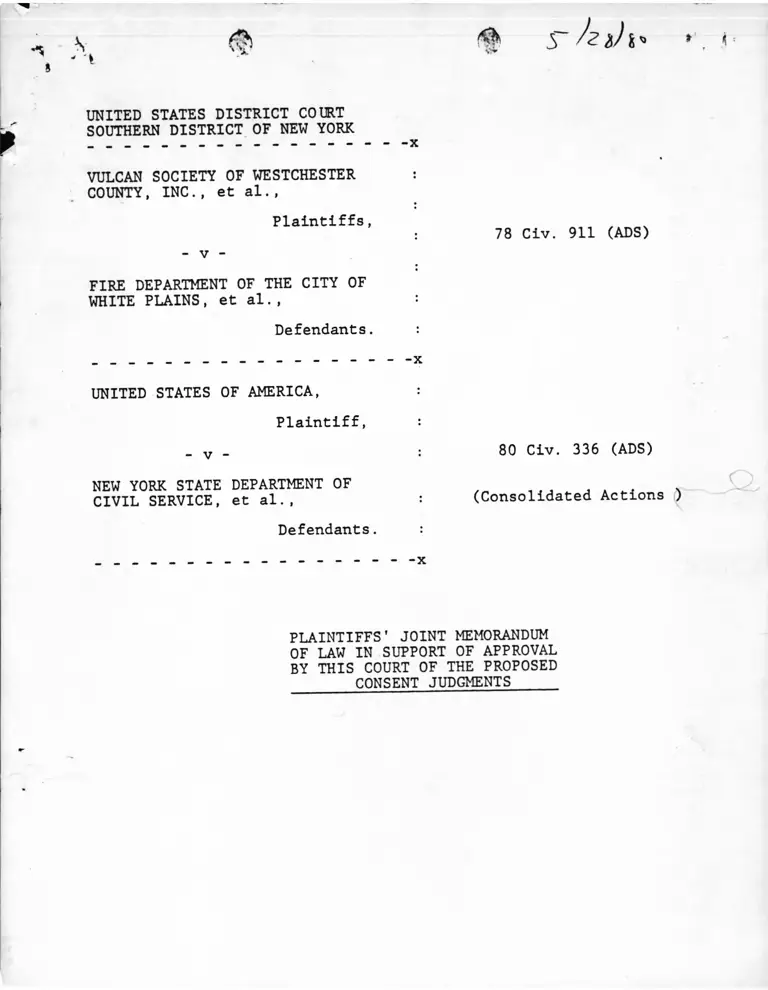

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

VULCAN SOCIETY OF WESTCHESTER

COUNTY, INC., et al.,

Plaintiffs, 78 Civ. 911 (ADS)

- v -

FIRE DEPARTMENT OF THE CITY OF

WHITE PLAINS, et al.,

Defendants.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, :

Plaintiff, :

- v - :

NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF

CIVIL SERVICE, et al., :

Defendants. :

-x

80 Civ. 336 (ADS)

(Consolidated Actions )

PLAINTIFFS' JOINT MEMORANDUM

OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF APPROVAL

BY THIS COURT OF THE PROPOSED

CONSENT JUDGMENTS_____

1 y »

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Preliminary Statement ........................... 1

Statement of Facts ........................... 3

A. Prior Proceedings ........................ 3

1. The Vulcan Action ...................... 3

2. The Government Action .................. 5

B. Background Facts 7

C. The Consent Judgments ..................... 18

Argument 22

The Consent Judgments Are Fair, Reasonable

And In Furtherance of Public Policy,

And Therefore Should Be Approved In Their

Entirety ..............'...................... 22

Standard of Judicial Review of Consent

Judgments ..................................... 22

The Reasonableness of the Terms of the

Consent Judgments ....................... 34

A. Prohibitions Against Future

Discrimination ....................... 34

B. Hiring Goals ....................... 35

C. Recruitment and Training ............ 39

D. Selection Procedures ................. 42

1. Language Improvement of

r Written Tests ..................... 42

2. Interim Relief Concerning

Written Tests .................... 47

3. Physical Strength/Agility Tests and

Elimination of Height and Reach

Requirements ..................... 55

4. Applicants With Conviction Records or

History of Drug Abuse ............ 58

Other Requirements for Firefighters,

i

4

5. 65

« TABLE OF CONTENTS

(continued)

6. Promotion to Fire Officer .........

E. Reporting Requirements ....................

F. General Injunctive Relief and Compliance ...

G. Back Pay for Class Members and

Individual Plaintiffs in Vulcan ...........

Page

66

68

69

70

Conclusion 74

'J -v ■V"

>

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -x

VULCAN SOCIETY OF WESTCHESTER

COUNTY, INC., et al. ,

Plaintiffs,

- v -

78 Civ. 911 (ADS)

FIRE DEPARTMENT OF THE CITY OF

WHITE PLAINS, et al.,

Defendants.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - — — x

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff,

- v - 80 Civ. 336 (ADS)

NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF ’ (Consolidated Actions)

CIVIL SERVICE, et al., :

Defendants.

x

PLAINTIFFS' JOINT MEMORANDUM

OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF APPROVAL

BY THIS COURT OF THE PROPOSED

CONSENT JUDGMENTS

The respective plaintiffs in these two consolidated

actions respectfully submit this joint memorandum of law urging

approval by this Court, pursuant to Rule 23 of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure and section 707 of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-6, of the

proposed Consent Judgments* submitted to the Court. These

^ The proposed Consent Judgment in 78 Civ. 911 (ADS) will be

referred to for convenience as the "Vulcan Consent Judgment." The

proposed Consent Judgment in 80 Civ. 336 (ADS) will be referred to

herein as the "Government Consent Judgment."

• o

Consent Judgments, representing the culmination of approxi

mately a year of intensive negotiations among the plaintiffs

and the state and municipal defendants representing the

New York State Department of Civil Service (the "State

defendants") and the Cities of White Plains, Mount Vernon and

New Rochelle (the "City defendants"), resolve all outstanding

issues among the plaintiffs and the State defendants and the

City defendants (collectively, the "settling defendants"),* '

with certain minor exceptions.**

For the reasons hereinafter set out in detail, the

plaintiffs submit that the terms of these proposed Consent

Judgments represent fair, reasonable and equitable methods of

resolving the claims made by the plaintiffs, preserving the

ability of the City defendants to select among qualified appli

cants for positions in the respective fire departments, and

generally assuring that the employment practices of the defen

dants will not serve as engines of discrimination against

Blacks, Hispanics and women.

The City of Yonkers and those of its officers and agencies

made parties to these actions have declined to settle either

action. Accordingly, this memorandum does not discuss these

actions as they apply to the Yonkers defendants.

** In the Vulcan Society case, 78 Civ. 911 (ADS), issues

relating to attorneys' fees, costs and disbursements for

plaintiffs' counsel and certain cross-claims among the settling

defendants are reserved for future determination. In addition,

the issue of the job-relatedness is being tried separately to

this Court and will control the retention or not of a high school

diploma or its equivalence as an entry level requirement.

2

«

/ v ' ' \

Statement of Facts

For the convenience of the Court, the plaintiffs

t will summarize briefly the relevant facts of these cases.

The prior proceedings in these actions, relevant factual

material regarding the employment practices of the settling ,

defendants and the history of hiring and promotion of minorities

in the defendant Cities, and a brief outline of the terms of the

Consent Judgments will be discussed separately.

A. Prior Proceedings

1. The Vulcan action

Following the investigation of complaints filed by the

Vulcan plaintiffs with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

("EEOC"), the EEOC determined, in a report dated February 11, 1977,

that discrimination existed with respect to the employment practices

of the settling defendants. Following the failure of efforts at

conciliation and the issuance of so-called "right to sue" letters,

see 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(1), the complaint in the Vulcan action

was timely filed on March 1, 1978, and amended as of right on

April 17 and April 24, 1978. In addition, the plaintiffs moved

on July 28, 1978, to amend the complaint further to add parties

plaintiff and defendant and to allege additional factual matters.

In an opinion of this Court dated April 10, 1979, the plaintiff's

motion, insofar as described above, was granted.* Vulcan Society

* The Court denied plaintiffs' motion to add allegations of a

conspiracy. In addition, this Court, in the April 10, 1979 opinion,

(i) granted class certification, (ii) granted plaintiffs' motion

to compel discovery, (iii) denied motions of the defendants to

dismiss the amended complaint or for summary judgment on various

grounds, and (iv) denied the motion of the White Plains defendants

to sever the action as to them.

3

of Westchester County, Inc, v. Fire Department of the City of

White Plains, 82 F.R.D. 379 (S.D.N.Y. 1979).

The complaint in the Vulcan case, as amended, alleges

that the settling defendants were engaged and are engaging in

acts and practices of discrimination in employment against

Blacks with respect to the hiring, assignment and promotion

practices within the fire departments of the cities of White

Plains, New Rochelle and Mount Vernon. In particular, the com

plaint, as amended, alleged that the settling defendants unlawfully

discriminated against Blacks in hiring and promotions and deprived

them of equal employment opportunities by the use of tests and

other selection standards and devices, which have a disparate

impact on Blacks and which are neither demonstrably valid nor

job-related. Such other selection standards and devices included

(i) requiring a high school diploma for employment; (ii) barring

employment based upon a prior conviction; (iii) word-of-mouth

recruitment; (iv) discouraging Blacks from seeking employment

with or promotion within the fire departments of the defendant

Cities; and (v) discriminatory assignments and allocation of job

benefits.

Jurisdiction was asserted on the basis of Titles VI and

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000d

et seq. and 2000e et seq., as well as 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983

and the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. The relief

4

t

f a f a“ l

sought included an injunction against the continued use by

the defendants of any employment practices which unlawfully

discriminate on the basis of race, together with affirmative *

relief, including back pay for affected individuals. The

defendants timely answered the amended complaints, denying

the material allegations thereof.*

Finally, during the pendency of this action, a

number of orders were entered enjoining or otherwise regulating

proposed hiring and promotions of the defendant Cities.

2. The Government action.

The complaint in the Government action was filed on

January 17, 1980, following by nearly a year the initial

notification to the defendants that, after an investigation by

the Department of Justice, the Attorney General had authorized

the commencement of this action and, in the intervening period,

intensive negotiations among the parties. The complaint in the

Government action alleges, inter alia, that the defendants were

engaged and are engaging in acts and practices which discriminate

on the basis of race, color, sex and national origin with respect

to employment opportunities within the fire departments of the

defendant Cities, which acts and practices constituted a pattern

and practice of resistance to the full enjoyment of the rights

of Blacks, Hispanics and women. In addition, the complaint

alleges that certain acts of the defendants discriminated against

Blacks, Hispanics and women in hiring and promotions by the use

In addition, certain cross-claims by the City defendants

against the State defendants were also made and denied.

5

■O

of tests and other selection standards and devices which

have a disparate impact on Blacks, Hispanics and women

and which are neither demonstrably job-related nor valid.

Jurisdiction is based upon Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, supra, the State and Local Fiscal Assistance

Act of 1972, as amended, 31 U.S.C. §§ 1221 et: seq. , and the

Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, as amended, 29 U.S.C.

§§ 801 et: seq. The relief sought in the Government action

included an injunction against the continued use by the defen

dants of employment practices which discriminate on the basis

of race, color, sex or national origin as well as those which

operate to continue the effects of past discriminatory employ

ment practices, as well as affirmative relief, including back

pay.

By reason of the fact that the Government and the

settling defendants have agreed to the provisions of and signed

the proposed Consent Judgment, none of the settling defendants

has submitted an answer in the Government action.*

* As set forth in the Consent Judgment, the settling defen

dants have not conceded the truth of the material allegations

of the complaint and, specifically, have denied that they have

engaged in any act or practice of unlawful discrimination

against Blacks, Hispanics or women. In addition, the State

defendants have specifically refused to concede that they are

an employer or an agent of an employer within the meaning of

section 701(b) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(b) or that the

Court has subject matter jurisdiction over the State defendants

pursuant to Title VII.

6

B. Background Facts

As indicated in the Argument portion of this memo

randum, infra, this Court is not called upon to try the

claims raised in the complaints in these actions, particularly

since the Consent Judgments are entitled to a ’’presumption of

validity.” United States v. City of Miami, 22 EPD 1 30,822

(5th Cir. Apr. 10, 1980). However, in carrying out its function

of determining whether the Consent Judgments are lawful, reasonable

and equitable, see United States v. City of Jackson, 519 F.2d 1147,

1151 (5th Cir. 1975), this Court may find the following brief

outline of facts already developed in this action to be of

assistance.*

The cities of White Plains, Mount Vernon, and New

Rochelle are three of the principal population centers in Westchester

County. During the past three decades, the minority population of

each has grown dramatically. To take the most extreme example, the

Black population of the City of Mount Vernon increased more than

three-fold between 1950 and 1970, to 35.6 percent of the

I l %

* It should be borne in mind that the United States, which

filed its complaint in January, 1980, never engaged in formal

discovery, except with respect to the high school diploma issue,

due to the fact that substantial settlement negotiations preceded

the filing of the complaint and the Consent Judgments were agreed

to in principle among counsel at the time of the filing of the

Government's complaint.

Similarly, although the Vulcan action was filed initially in

March 1978, a stay of discovery was in effect for much of that

time and intensive negotiations among the parties endeavoring to

settle lasted approximately ten months.

7

total population of the city. Even more dramatic growth has

been recorded by the Hispanic population of each city.* There

is no reason to doubt that this trend will continue.

The employment of minorities by these fire departments

has at all times been at a level which might appropriately be

called minimal. Mount Vernon's fire department, for example,

employees had only 2.170 minority personnel as of 1976, although

the city's minority population is 38%.** The relative figures

for the other cities are not markedly different.***

* Population figures for the three municipalities drawn from

the 1950, 1960 and 1970 Censuses were tabulated by the EEOC in

its 1975 determination and are set forth in Table I. In addition,

1960 and 1970 Census figures for the population between the ages

of sixteen and sixty-four for each of the municipalities, as well

as Westchester County, are set forth in Tables II and III. All

tables appear at the end of this brief.

** The four fire departments have in recent years required

residency in Westchester County for applicants. However, beginning

with the May, 1978 firefighter examinations, the respective

municipalities, in addition to the requirement of Westchester

County residency, gave preference to residents of the respective

municipalities.

*** Comparative fire department employment figures and population

ratios are set forth in Table IV. Detailed employment figures

from the 1976 EEO-4 reports filed with the EEOC are summarized

in Tables V, VI, and VII. The hiring statistics for all position

in the three fire departments, drawn from EEO-4 reports from 1974

through 1976, is contained in Table VIII.

8

The figures set forth in Tables IV through VIII

are substantially confirmed by data produced by the defendant

cities themselves during discovery in the Vulcan action.

Thus, for example, Mount Vernon and New Rochelle produced

data indicating men* in the fire department work force, by

job title and race, for the period 1972 through 1978.** For

New Rochelle, the figures show that during the seven years

reported, New Rochelle never had a Black fire lieutenant,

fire captain, deputy chief or chief. In 1978, when the fire

department force was comprised of 180 men, only seven, or 3.9%,

were Black. Similarly, in Mount Vernon, during the period from

1972 to 1978, no Black was ever a fire officer. As of June 29,

1978, out of a total force of 133 fire fighters and fire officers,

only three, or 2.3%, were Black. In White Plains, a September 1975

report of the Commission on Human Rights of the City of White Plains,

reported generally, "Many of the departments and bureaus of the

City government are exclusively or predominantly staffed, and most

of the higher-echelon positions throughout the City government are

held by white male employees."*** In addition, the Commission

reported that, out of 173 persons in the categories of "protective

* None of the fire departments of the defendant cities has ever

employed a woman as a fire fighter or fire officer.

** This data is set forth, with respect to New Rochelle, in Table

IX and, with respect to Mount Vernon, in Table X.

*** Commission on Human Rights, City of White Plains, Report on the

Work Force of the City of White Plains Employment of Ethnic Minorities

and of Women, September 1975, at p. 14.

9

services," "professionals," and "administrators" in the White

Plains Fire Department, only four (2.3%) were Black and two (1.2%)

were Hispanic.*

The figures in these tables showing exceedingly low

employment of minorities and women in the fire departments are

but a reflection of the historical practices of these fire

departments. At a trial of this action, the plaintiffs would

have shown, based on testimony of the individual plaintiffs in

the Vulcan suit, that, as of 1976, Mount Vernon had employed

five Blacks in its fire department since 1953, White Plains had

employed eight Blacks since 1949, and New Rochelle had employed

approximately ten Blacks in its history.

The plaintiffs have alleged that a number of the employ

ment practices used by the settling defendants have contributed

to the alleged discrimination. Paramount among these practices

is the use of a written examination for both hiring and promotion

purposes. In both these contexts, the written examination has

been the principal selection device. With respect to the hiring

of firefighters, the test was used to rank applicants, sometimes

exclusively, as was formerly the case in White Plains and Mount

Vernon, and sometimes in a weighted ranking procedure involving

also the physical agility test score. The emphasis on the written

test as a ranking device means that minorities must not only pass

Id., at Table VI-b

10

the test but attain a high score as well.* Since the duration

of a state-certified eligibility list is limited to between one

and four years, N. Y. Civil Service Law §56, the likelihood

that more than a small percentage of the applicants appearing

on an eligibility list will actually be selected for appointment

is slight.

Section 23, subsection 2, of the New York Civil Service

Law provides that, upon the request of any municipal civil service

commission, the state civil service department "shall render service

relative to the announcement, review of applications, preparations,

construction, and rating of examinations, and establishment and

certification of eligible lists for positions in the classified

service under the jurisdiction of such municipal commission."

Because of the high cost of developing, preparing and rating

entrance examinations, each of the three cities involved here has

consistently requested the state to develop and administer the

firefighter and fire officer exams.

The EEOC had little difficulty concluding from its investigation that

these examinations result in an adverse impact on minorities. Aside

from the figures showing gross under-representation of minorities

on the respective fire department rosters, New Rochelle collected

data regarding the racial makeup of the applicant pool on a

recent examination. The data from New Rochelle is unfortunately

* The actual selection for a firefighter vacancy is governed by

the so-called "rule of three," which limits selection to one of the

three highest ranked persons on the then-current eligibility list.

See N.Y. Civil Service Law §61.

- 11 -

limited and not entirely reliable since it involves voluntary

racial identification. Only twenty-nine applicants who filed

for the exam, twenty-four Whites and five Blacks, listed their

race on the application forms, and two Blacks and eight Whites

failed to appear for the exams. Thus, of the three Black and

sixteen White applicants who identified their race and appeared

for the exam, 81.2% of the Whites passed and 66.77° of the Blacks

passed. Overall, the average exam score for Whites was 77.8,

while that for Blacks was 68.3. Although it is difficult to

generalize from such a small sample, the data permit an inference

that a statistically adequate sample on this test would support

a conclusion of disparate racial impact.*

This evidence of adverse impact is buttressed by the

results of a written firefighter examination administered in

May 1978 in Mount Vernon, White Plains and New Rochelle. The

results of this test, which are set forth in Table XI for Whites

* More complete data was available for a 1975 firefighters

exam given in Yonkers. Although Yonkers is not a settling

defendant, the data from that test is nevertheless instructive

regarding the racial impact of the tests administered by the

state. In Yonkers, which had the rather complete data for its

1975 examination, the results showed that 60% of the Blacks,

and 50% of the Hispanic applicants who appeared for the exam

passed. The pass rate for Blacks and Hispanics taken together

was 57.1%. This is to be compared to a pass rate of 76.5% for

the Whites who appeared for the exam. Among those minorities

who passed the written exam and the subsequent medical exam, the

highest scoring minority applicant only ranked 128th out of a

total eligibility list of 166 persons and thus had little practical

chance of being selected for appointment as a firefighter.

The pass rate differentials exhibited by the data in the

1975 Yonkers firefighter exam constitute a substantial difference,

and evidence of an adverse impact from the state-prepared test,

under the "four-fifths" rule of thumb of the Uniform Guidelines

on Employee Selection Procedures, 43 Fed. Reg. 38290 (1978).

12

and Blacks,* show that the pass rate for Whites was between

twenty and thirty percentage points higher than for Blacks

in each City. Each of the pass-rate differentials in these •

three cities shows evidence of adverse impact under the "four-

fifths" test of the Uniform Guidelines. More significant,

however, was the fact that each of these three pass-rate

differentials was statistically significant. Using a statistical

procedure known as testing the difference between independent

proportions,** it was found that the Black pass rates were uniformly

more than three standard deviations lower than the White pass

rates and, in one case, more than six standard deviations lower.***

Statistically, the odds of obtaining such differential pass rates

randomly are greater than ninety-nine to one. As stated by the

Supreme Court in an analogous context, "Because a fluctuation of

more than two or three standard deviations would undercut the hypo

thesis that decisions were being made randomly with respect to

race, [Castaneda v. Partida,] 430 U.S. [482] at 497 n.17 [1977],

each of these statistical comparisons would reinforce . . . the

Government's other proof.” Hazelwood School District v. United States,

* There is evidently some uncertainty in these figures due to

"cross-overs," that is applicants who took the exam in one city and

were considered for employment in another. Separate results for

the five Hispanics and five women who took the exam are not shown.

Of these, however, nine passed the exam.

** This procedure is described in a discrimination context in

Shoben, Differential Pass-Fail Rates in Employment Testing: Statis

tical Proof Under Title VII, 91 Harv. L. Rev. 793 (1978).

*** xhe precise standard deviation differentials , the "Z score"

as defined by Shoben, supra, were: New Rochelle - 6.17; White

Plains - 4.67; Mount Vernon - 3.27.

13

433 U.S. 299, 311 n.17 (1977).

There is little evidence that the entrance examinations

are valid within the meaning of the Uniform Guidelines, supra, or

indeed that any but somewhat perfunctory validation efforts have

been made by the New York State Department of Civil Service, which

is solely responsible for their content. The report of the EEOC

in this case succinctly summarized the Civil Service Department's

evidence before the Commission on this point:

The New York State Civil Service Commission

was asked to provide the professional credentials

of the persons who prepare the test. From their

answer it does not appear that any have advanced

degrees in psychology (though some have taken

graduate courses in the area) or any experience

in test preparation outside of the New York State

Civil Service Commission.

The New York State Civil Service Commission

says it has "confidence in the test" but beyond

arguing that it is good, as most people who pass

it do not drop out on probation, concedes that

there is no study to link performances on the

test with performances on the job. The New York

State Civil Service Commission argues that the

test is "content" valid, and that that is

sufficient. There is no evidence even of its "con

tent" validity beyond the fact that the questions

relate generally to the areas of employment.

EEOC Determination at pp. 17-18 (Feb. 11, 1977). The evidence

produced by the state in the Vulcan suit did little to alter

the appropriateness of the findings of the EEOC regarding the

lack of validity of the firefighters tests or to show that any

validity studies had been conducted in accordance with the

Uniform Guidelines.

14

Like the process of becoming a firefighter, the promotion

of firefighters to fire lieutenants is governed principally by an

examination devised and administered by the New York State Depart

ment of Civil Service. The three fire departments also add points

to the test score to take into consideration seniority with the

municipality, and a certain minimum requirement of seniority as a

firefighter is a pre-requisite to applying for a fire officer

position.*

The disparate racial impact of the promotional examina

tion can be shown in several ways. To begin with, as of the

commencement of the Vulcan Society action, not a single one of the

fire officers in the fire departments of the three cities involved

in the Consent Judgments is either a Black, Hispanic or woman.**

In addition, while Black firefighters are relatively more likely

to take the fire lieutenant's exam than their White counterparts,***

Blacks fail the exams at nearly twice the rate of White firefighters.

In five recent fire lieutenant exams, two each in White Plains and

New Rochelle, and one in Mount Vernon, given during the period fron

November 1972 to June 1975, 242 Whites took the exam, of which 135

* In White Plains and Mt. Vernon, for example, one must have been

a firefighter for five years to be considered for promotion to fire

lieutenant.

** Since that time, one Black has been appointed a fire lieutenant

in New Rochelle.

*** For five recent fire lieutenant exams given among the three fire

departments, two exams each in New Rochelle and White Plains, and one

exam in Mt. Vernon, 86.7% of the Black firefighters applied for

promotion, as opposed to 63.3%, of the White firefighters.

15

(55.8%) passed, and thirteen Blacks took the exam, of which only

four (30.8%) passed.* Among those who passed, the Whites had an

average score of 79.88, while the Blacks had an average score of

73.20.

As with the entrance-level examinations, the New York State

Department of Civil Service failed to adequately document the validity

of the tests, offering only the most general claims of "content"

validity. However, there is available evidence to suggest the

invalidity of these tests.

Until relatively recently, White Plains gave each firefighter

a performance rating, based upon supervisory evaluations of such

qualities as "ability," "cooperation," "leadership," "records,"

"mental alertness," "observance of safety principals [sic],"

"proficiency in drills and housework," etc. Each quality was rated

on a 100-point scale,and a weighted "special fitness rating," also

on a 100-point scale, was derived from these supervisory evaluations.

The fitness ratings of forty-one White firefighters were examined

by the EEOC** in connection with their performance on the written

fire lieutenants exam and the twenty-four firefighters who passed

the written exam averaged 89.32 on the fitness ratings, while the

seventeen firefighters who failed the written exam actually had a

higher average performance rating, 89.59. In addition, the top four

scorers on the written exam had the following rank on the fitness

ratings:

* This pass-rate differential constitutes evidence of adverse

impact under the "four-fifths" test of the Uniform Guidelines, supra.

** See EEOC Determination, supra, at 23-24.

- 16 -

Rank on

Written Exam

Rank on

Fitness Rating

1 4

2 17

3 5

4 10

Similarly, comparing the ranking in the written test for the

highest fitness rankings:

Rank on Rank on

Fitness Rating Written Exam

1 5 (tie)

2 5 (tie)

3 18

4 1

Taken together, these figures, though incomplete, never

theless indicate that the validity of these promotional examinations

is subject to serious challenge.

Aside from the written tests the plaintiffs in these actions

were also challenging other employment practices, such as recruiting

methods, height and reach requirements, variable age restrictions,

a bar against employment of a person convicted of a crime, and, in

New Rochelle, a requirement of possession of a Class III chauffeur's

license.* Because of the restrictions with respect to age, criminal

convictions and possession of a high school diploma, it has been estimated

* Each city also required possession of a high school diploma,

which requirement was challenged in both suits. However, since

that issue is being tried separately to the Court, it will not be

discussed in this memorandum

that the number of Blacks in Mount Vernon who were discouraged

from applying to the fire department from 1970 to 1978 was Min

the several hundreds." (Affidavit of Percy Somerville, dated •

June 29, 1978, at 11 11-13). A comparable estimate was made for

New Rochelle. (Affidavit of Napoleon Holmes, dated June 14, 1978,

at 1 10). Moreover, it was estimated that, in New Rochelle from

1964 to 1978, out of over two hundred Blacks who completed appli

cations for the written firefighter examination, roughly half

did not sit for the examination. (Id. at 1 11). Finally, the

EEOC found, as a result of its investigation, that reasonable

cause existed to believe that the fire departments of the settling

defendants violated Title VII with respect to recruitment,

eligibility and selection standards and promotion. (EEOC Deter

mination, supra, at 28.).

In sum, the available evidence, generated without the benefit

of full discovery, is nevertheless more than sufficient to show

that the claims of the plaintiffs were substantially supported and

presented a number of litigable issues with respect to the

settling defendants.

C. The Consent Judgments

The settling parties, after lengthy negotiations, have

agreed upon proposed Consent Judgments which have been submitted

to this Court for approval. In agreeing to the provisions of the

Consent Judgments, the settling defendants specifically deny that

they have engaged in any practice of unlawful discrimination against

the plaintiffs or the classes represented by them, and the Consent

v V

ft*

Judgments so state. In addition, the Consent Judgments recite

that the consent of the parties to the Consent Judgment shall

not constitute nor be construed as an admission by the settling

defendants of any statute which forms the basis for these actions.

Rather, the parties have entered into these arguments to settle

the issues raised by the complaints without the need for a pro

tracted course of litigation and to assure that Blacks, under the

terms of the Vulcan Consent Judgment, together with Hispanics and

women, under the terms of the Government Consent Judgment, are

not disadvantaged by reason of their race, national origin or sex

in the hiring, assignment and promotion policies and practices of

the fire departments of the settling defendants.

The parties have endeavored to make these two Consent

Judgments consistent with one another and, indeed, the Consent

Judgments recite that each "shall be construed and applied in a

manner not inconsistent with" the other.

To the greatest extent possible, the terms of the two

Consent Judgments are worded in a parallel manner, with whatever

variations are necessary to reflect that, while the Vulcan action

seeks to remedy discrimination on the basis of race only, the

Government action seeks relief for discrimination on the basis

of race, national origin, and sex. The substantive provisions which

are parallel and common to the two Consent Judgments are as follows:*

* To avoid unnecessary repetition, the specifics of the

Consent Judgment are discussed in detail in the argument, infra.

19

Section No.

Title of Vulcan Society United States

Section Consent Judgment Consent Judgment

Procedures for Selection

of Firefighters II II

Procedures for Promotions III V

Improvement of Future

Written Tests IV III

Interim Appointment

of Firefighters V IV

Hirings Goals and

Interim Hiring Goals VI VI

Recruitment and Training X VII

Reporting XI VIII

General Injunctive

Relief and Compliance XII IX

Jurisdiction XV X

In addition, the sections which are peculiar to the Vulcan Consent

Judgment are:

Title of

Section Section Number

Damages to the Classes

of Black Entry Level

Applicants VII

Relief to Individually-

Named Plaintiffs VIII

Relief to the Vulcan

Society of Westchester

County, Inc. IX

Attorneys' Fees, Costs,

and Disbursements; City

Defendants' Cross-Claims XIII

Class Certification XIV

20

As can be seen, these two Consent Judgments form a

comprehensive and consistent resolution of the issues raised

by these two actions involving the employment practices in the

fire departments of the settling defendant cities. As noted,

the specific provisions of the Consent Judgments are discussed

in detail in the argument portion of this memorandum and, as we

argue below, are a lawful, reasonable and equitable means of

settling these actions.

21

NEFtbmj

05-8586

1ft

ARGUMENT

THE CONSENT JUDGMENTS ARE FAIR, REASONABLE

AND IN FURTHERANCE OF PUBLIC POLICY, AND

THEREFORE SHOULD BE APPROVED IN THEIR ENTIRETY

As described above, the original parties to

Government's action and the private action (with the

exception of the Yonkers defendants) agreed to settlements

on the terms embodied in the Consent Judgments.* These

agreements were obtained after extensive negotiations and

consideration of the competing interests to be promoted by

Title VII and the other civil rights laws, on the one hand,

and the need to select expeditiously qualified individuals

to become firefighters and officers without expenditure of

large sums in litigation, on the other hand.

Standard of Judicial Review of Consent Judgments

The law is clear that the Court's role in

considering whether or not to approve a consent judgment in

an action brought by the Government or in a private class

action is to make a determination that "there has been valid

consent by the concerned parties and that the terms of the

decree are not unlawful, unreasonable, or inequitable."

E.g, United States v. City of Jackson, 519 F.2d 1147, 1151

* The Consent Judgments, as presently filed, contain a

provision for the elimination of the high school diploma

requirement. This term however, remains in issue and is

presently being tried to the Court.

-22-

NEFrbmj .4*

05-8586

(5th Cir. 1975). Basically, approval is dependent upon the

issue of "overall fairness." United States v. Trucking

Employers, Inc., 561 F.2d 313, 317 (D.C. Cir. 1977).

Accord, United States v. City of Miami, 22 EPD 1f 30,822 (5th

Cir. Apr. 10, 1980); United States v. City of Alexandria, 22

EPD H 30,829, (5 th Cir. Apr. 10, 1980) ; Grunin v.

International House of Pancakes, 513 F.2d 114 (8th Cir.) ,

cert, denied, 423 U.S. 864 (1975); State of Vest Virginia v.

Chas. Pfizer & Co., 440 F.2d 1079, 1086 (2d Cir.), cert.

denied, 404 U.S. 871 (1971); City of Detroit v. Grinnell

Corp. , 356 F. Supp. 1380 (S.D.N.Y.), aff1d in part, rev1d in

part on other grounds, 495 F.2d 448 (2d Cir. 1972).*

The Consent Judgments are entitled to a "presump

tion of validity." United States v. City of Miami, supra,

22 EPD 1130,822, at 15,246. This is particularly true where

the United States is a party to a settlement and finds the

terms of compromise to serve the ends of the statutes the

Government is designated to enforce, such as Title VII.

Id.** The Court must have a "principled reason for refusing

* The same standards apply to the Government's case

brought under § 707 of Title VII and the private plaintiffs'

case, which was brought under § 706. See cases cited,

supra. In addition, the standards under the Revenue Sharing

Act and CETA are identical to Title VII.

** It should be noted that if the United States had

elected to negotiate with defendants through the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission ("EEOC") instead of in the

context of a suit prosecuted by the Department of Justice,

and a conciliation agreement with exactly the same terms as in

the proposed Consent Judgment was reached with the EEOC,

"the district court's scrutiny of the terms of the agreement

would be minimal." Id. at 15,246; see EEOC v. Contour Chair

Lounge Co., 596 F ^ d -809 (8th Cir. 1979J~-

-23-

NEF:bmj

05-8586

to sign a consent judgment in this context [and a] refusal

to sign . . . based on generalized notions of unfairness is

unacceptable." Id. There must be showing that the decree

unduly burdens one class or another. Id. If the Court

finds that more information is necessary than that already

in the record, then a hearing is appropriate; however, prior

to the hearing, the parties are entitled to the Court's

explanation of its precise concerns. Id.

This standard is the result of the congressional

and judicial policies favoring settlement generally, and in

Title VII cases in particular, since conciliation is the

preferred means of eliminating discrimination. Airline

Stewards and Stewardesses Association, Local 550 v. American

Airlines, Inc. , 573 F.2d 960 (7th Cir. 1978) ("Stewards") ;

United States v. Trucking Employers, Inc., supra, 561 F.2d

at 317; Patterson v. Newspaper & Mail Deliverers Union, 514

F.2d 767, 771 (2d Cir. 1975) ("Patterson") ; United States v.

Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc., 517 F.2d 826, 849-50 (5th

-24-

EF:bmj

5-3586

ir. 1975); United States v. City of Jackson, supra, 519

. .2d at 1151. See Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co. , 415

S. 36, 44 (1974) *

The rationale for courts' endorsements of settlements

as explained in the seminal case of Florida Trailer and

guipment Co. v. Deal, 284 F.2d 567, 57T"(5thTir. 19FUT:

Of course, the approval of a proposed

settlement does not depend on establishing

as a matter of legal certainty that the

subject claim or counterclaim is or is

not worthless or valuable. The probable

outcome in the event of litigation, the

relative advantages and disadvantages are,

of course, relevant factors for evaluation.

But the very uncertainty of the outcome in

litigation, as well as the avoidance of

wasteful litigation and expense, lay

behind the Congressional infusion of a

power to compromise. This is a recogni

tion of the policy of the law generally to

encourage settlements. This could hardly

be achieved if the test on hearing for

approval meant establishing success or

failure to a certainty. Parties would be

hesitant to explore the likelihood of

settlement apprehensive as they would be

that the application for approval would

necessarily result in a judicial determina

tion that there was no escape from liability

or no hope of recovery and hence no basis

for a compromise.

ccord, Stewards, supra, 573 F.2d at 963; United States v.

xllegheny-Ludlum, Industries, Inc., supra, 517 F.2d at 849;

at_terson, supra, 514 F. 2d at 771; State of Vest Virginia v.

HasT! Pfizer & Co., supra, 440 F.2d at 10815; Teachers Insurance

rul-Annuity Ass FT v. Beame, 67 F.R.D. 30, 33 (S.D.N.Y. 19/5).

-25-

«-» ■ m m r c

NEF:bmj ^

05-8586

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

explained the relevant principles:

. . . to the extent that the settlement may

in occasional respects arguably fall short of

immediately achieving for each affected

discriminatee his or her "rightful place," we

must balance the affirmative action objec

tives of Title VII . . . against the equally

strong congressional policy favoring voluntary

compliance. The appropriateness of such

balancing is especially clear, as here, "in

an area where voluntary compliance by the

parties over an extended period will contribute

significantly toward ultimate achievement of

statutory goals." [Patterson v. Newspaper &

Mail Deliverers Union, supra,] 514 F. 2d at

7717----------------

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc. , supra,

517 F.2d at 850.

Furthermore, courts have recognized that a consent

judgment is essentially a contract between the parties.

United States v. City of Jackson, supra, 519 F.2d at 1151;

Regalado v. Johnson, 79 F.R.D. 447, 450 (D. 111. 1978).

Therefore the issues raised by objectors or intervenors in

opposition to a consent judgment's terras "should not be

decided on the basis of Title VII law, but rather must be

decided on the basis of legal principles regulating judicial

review of settlement agreements," Metropolitan Housing

Development Corporation v. Village of Arlington Heights, 469

F. Supp. 836, 846 (N.D. 111. 1979). Accord, State of Vest

Virginia v. Chas. Pfizer & Co., supra, 440 F.2d at 1086;

-26-

NEF:bmj

05-8586

City of Detroit v. Grinnell Corp. , supra, 356 F. Supp. at;

with the recognition that "the agreement reached . . . embodies

a compromise; in exchange for the saving of cost and elimina

tion of risk, the parties each give up something they might

have won had they proceeded with the litigation." United

States v. Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673, 68 (1971). See

Grunis v. International House of Pancakes, supra, 513 F.2d

at 124. "(T]he inherent nature of a compromise is to give

up certain rights or benefits in return for others."

MacDonald v. Chicago Milwaukee Corp. , 565 F.2d 416, 429 (7th

Cir. 1977); United States v. American Institute of Real

Estate Appraisers of the National Association of Realtors,

442 F. Supp. 1072, 1084 (N.D. 111. 1977). There should be

no attempt to precisely delineate the parties' legal rights.

United States v. City of Jackson, supra, 519 F .2d at 1152.

Where, as here, the Court retains the power to modify or

vacate the decree if it later appears necessary, there is no

justification to withhold approval in the absence of a clear

showing that a group is unduly burdened by certain terms of

that decress. United States v. City of Miami, supra, 22 EPD

1130,822, at 15,246-47.

-27-

NEF:bmj

05-8586

/**\* <

Finally, it should be noted that the burden is on

the objectors to convince the Court to disapprove the

proposed settlement. Id. at 15,247. Absent evidence in the

record to demonstrate that the settlement is "unreasonable,

illegal, unconstitutional or against public policy, [the

Court] should grant [its] approval." Id. Accord, United

States v. City of Alexandria, supra.

Applicable Standards as to Employment Discrimination

The legal framework in which the Consent Judgments

are proposed by the parties is relevant, although not

entirely dispositive, as discussed above. As the Court is

well aware, the legal standards under Title VII* have been

firmly established by the Supreme Court.

An employer violates Title VII if it bases its

selection decisions on an examination or other procedure

("selection procedure") that has an adverse impact on the

employment opportunities of minorities, unless the employer

can show that use of the examination validly predicts

successful job performance. Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401

U.S. 424 (1971) ("Griggs"); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975) ("Albemarle") ; see 42 U.S.C. §

2000e-2(h).

* The same standards apply to the other statutes under

which this action was brought. See, e.g., United States v.

State of New York, 82 F.R.D. 2 (FHT.NTYT 19/8) , a 21 EPD

If 393l4~(N.D.N.Y. 1979).

-28-

NEF:bmj

05-8586

A plaintiff makes a prima facie case of

discrimination if he shows that a minority group has a

disproportionately lower passing rate on the examination

than whites and are, consequently, selected for employment

at a rate lower than their rate of application. Albemarle,

supra, 422 U.S. at 425. There is no need to show a discrimina

tory purpose; a prima facie case of employment discrimination

may be established by evidence of statistical disparities

alone. Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321, 329 (1977);

Scott v. City of Anniston, 597 F.2d 897, 899 (5th Cir.

1979) , cert, denied, 48 U.S.L.W. 3698 (U.S. Apr. 29, 1980);

Blake v. City of Los Angeles, 595 F.2d 1367, 1374-75 (9th

Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 48 U.S.L.W. 3698 (U.S. Apr. 29,

1980) ; United States v. City of Chicago, 573 F.2d 416,

420-22 (7th Cir. 1978) ; Firefighters Institute for Racial

Equality v. City of St. Louis, 549 F.2d 506, 510 (8th Cir.

1977).

Both the burden of production and the burden of

persuasion shift to the defendant once the plaintiff shows

that the selection procedure has an adverse impact on

minorities. E.g., Guardians Association v. Civil Service

Commission, 431 F. Supp. 526, 538 (S.D.N.Y.), vacated and

remanded on other grounds , 562 F .2d 38 (2d Cir. 1977), on

remand, 466 F. Supp. 1273 (S.D.N.Y. 1979), app. pending No.

-29-

NEF:bmj

05-8586

/fw>— t 'i

79-7377 (2d Cir.); Vulcan Society of the New York Fire

Department v. Civil Service Commission, 360 F. Supp. 1265,

1268 (S.D.N.Y.), aff'd, 490 F.2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973). To

prevail, the defendant must prove that the challenged

selection procedure, has a "manifest relationship to the

employment in question." Griggs, supra, 401 U.S. at 432;

Dothard v. Rawlinson, supra, 430 U.S. at 329.

Proof that a selection procedure is job-related

must be based on a study which meets "professionally

acceptable" standards and procedures. Albemarle, supra, 422

U.S. at 431. The federal agencies authorized to enforce

federal fair employment laws have issued Uniform Guidelines

on Employee Selection Procedures, 43 Fed. Reg. 38290 (1978)

("Uniform Guidelines"),* which set standards the Government

considers to be consistent with standards of the

psychological profession for assessing the job-relatedness * * * §

* The Uniform Guidelines, promulgated by the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission, the Department of

Justice, the Department of Labor, and the Civil Service

Commission, took effect September 25, 1978. They are

codified at each of the following places: 28 C.F.R. §

50.14; 41 C.F.R. § 60-3.1; 29 C.F.R. § 1607; and 5 C.F.R.

§ 300.103(c).

-30-

NEF:bmj

05-8586

or "validity" of employee selection procedures. Uniform

Guidelines, Hf 1C, 5C. These Guidelines are "entitled to

great deference," and should be followed, unless the

employer demonstrates some cogent reason to the contrary.

Griggs, supra, 401 U.S. at 433-34; Albemarle, supra, 422

U.S. at 431; United States v. City of Chicago, 549 F.2d 415,

430 (7th Cir.), cert, denied sub nom.Arado v. United States,

434 U.S. 875 (1977).

Proof that the challenged selection procedure has

been validated does not end the inquiry. Even if the

employer, through a professionally acceptable study,

convincingly demonstrates that the discriminatory procedure

is job-related, the employer may still be liable for

violating Title VII. If the plaintiff shows that there were

available alternative selection procedures which serve the

employer's legitimate interests and have less adverse impact

on Blacks and Hispanics, then the defendants' use of the

challenged examination is not justified by "business

necessity." Albemarle , supra, 422 U.S. at 425; see, e.g.,

Allen v. City of Mobile, 464 F. Supp. 433 (S.D. Ala. 1978).

-31-

NEF:bmj

05-8586

Furthermore, it is generally recognized that once

a violation of the federal equal employment opportunity laws

is proven the district court has the power and, indeed, the

duty to enjoin future discrimination and as far as possible

to require the elimination of continuing effects of past

discrimination. E.g., Albemarle, supra, 422 U.S. at

418; Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965);

Rios v. Enterprise Association of Steamfitters, Local 638,

501 F.2d 622, 629 (2d Cir. 1974). Since the district court

possesses broad power and discretion as a court of equity,

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co. , 424 U.S. 747, 763-64,

770 (1976); Rios v. Enterprise Association of Steamfitters,

Local 638, supra, 501 F.2d at 629, the parties recognize

that numerical goals as well as immediately imposed interim

hiring procedures designed to eradicate the adverse impact

of past discrimination are often appropriate. See, e.g.,

Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality v. City of St.

Louis, 22 EPD H 30,571 (8th Cir. Jan. 17, 1980),

("Firefighters Institute"); United States v . City of

Chicago, supra; NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir.

1974); Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.) (en

banc), cert. denied, 417 U.S. 969 (1974); Bridgeport

Guardians, Inc. v. Members of the Bridgeport Civil Service

-32-

NEF:bmj

05-8586

Commission, 482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir. 1973), cert. denied, 421

U.S. 991 (1975); United States v. State of New York, supra,

21 EPD‘, at 12,712-14; United States v. City of Buffalo, 20

EPD 11 30,112 (W.D.N.Y. Dec. 11, 1978). Cf. Regents of the

University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978).

This summary of the applicable law demonstrates

that the burdens of proof on each party in Title VII actions

are great, and discovery and trial of the issues therein

involve significant expenditures of time and money. There

fore, the settling parties in the cases before the Court

have chosen to obviate the need for such proof, and instead

have agreed to the Consent Judgments. See preamble to

Consent Judgments, at pages 1-6.

The parties submit that the Consent Judgments are

legal, reasonable, fair, and in furtherance of the goals of

the statutes plaintiffs seek to enforce. They also further

the public interest sought to be vindicated by all parties

that firefighters in the defendant Cities be selected in the

future on the most equitable and effective basis. The

Consent Judgments' terms enable the defendant Cities to

select firefighters in the near future to fill immediate

needs without violating Title VII's anti-discrimination

provisions, while also providing for long-term improvement

of the selection process utilized by defendants. A summary

of the terms of the Consent Judgments follows.

-33-

NEF:bmj

05-8586

The Reasonableness of the

Terms of the Consent Judgments

A. Prohibition Against Future Discrimination.

The Consent Judgments contain an injunctions against

defendants' consideration of race, national origin or sex in

the review of applications or "appointment to any position"

in the defendant Cities fire departments (5f 11(A))*. Such

provisions are standard and expressly authorized by Title

VII. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5( f) (3). E. g., Albemarle, supra,

422 U.S. at 418; Louisiana v. United States, supra, 380 U.S.

at 154; Rios v. Enterprise Association of Steamfitters, Local

638, supra, 501 F.2d at 629. Accordingly, they should be

approved by the Court.

* References to paragraphs numbers in parentheses are

to the applicable provisions in the Government's Consent

Judgment. The analogous provisions in the Vulcan Consent

Judgment appear at paragraphs with the same numbers unless

otherwise noted.

-34-

* NEF:bmj

' , 05-8586

p

B. Hiring Goals

The Consent Judgments provide for a long term goal

that the defendant Cities "undertake in good faith to hire

firefighters so as to achieve the goal of firefighter force

in each City which reflects no less than the proportion of

Blacks and Hispanics between the ages of eighteen (18) and

forty-four (44) in the civilian labor force of that City as

reported by the U.S. Census Bureau of the most recently

published decennial census then available." (11 VI(A)). The

defendant Cities also each are to seek, as interim goals, to

make promotions so as to have the ranks of officers reflect

the proportion of Black, Hispanic and women firefighters in

each City's force (11 VI(B)). The Cities are to seek to hire

firefighters in proportions to reflect the Black and

Hispanic representation in the group of persons between the

ages of eighteen and thirty in the civilian labor force in

the respective Cities in the then most recent U.S. Census

Bureau decennial census (U VI(C)). Finally, women are to be

hired, if possible, so as to constitute at least 10% of the

new firefighters until the number of women on each City's

force equals at least 10% (Iff VI(D) , (E)). These

percentages are goals, i.e■, "hiring targets", and not

"quotas" (11 VI(F)).

-35-

NEF:bmj

05-8586

It is fully appropriate to include such goals in

the Consent Judgments. Besides the fact that they require

the hiring and promotion of only qualified candidates (See,e.g., •

United States v. State of New York supra, 21 EPD H 30,314,

at 12,712 ), they are consistent with the mandates of Title

VII when there is shown to be a history of race, national

origin or sex discrimination. United States v. City of

Miami, supra, 22 EPD H 30,822, at 15,248, and cases cited

therein; United States v. City of Alexandria, supra, 22 EPD

1f 30,829, at 15,297-98. The goals are reasonable in light

of the defendant Cities' past hiring practices. See and

Compare Firefighters Institute, supra, 22 EPD 11 30,571;

United States v. City of Chicago, supra; Kirkland v. New

York State Department of Correctional Services , 520 F.2d

420, 429-30 (2d Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 823

(1976); NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974); Morrow

v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.) (en banc), cert.

denied, 417 U.S. 969 (1974); Vulcan Society of New York City

Fire Department, Inc. v. Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d

387 (2d Cir. 1973); Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Members

of the Bridgeport Civil Service Commission, 482 F.2d 1333

(2d Cir. 1973), cert. denied, 421 U.S. 991 (1975); United

States v. State of New York, supra, 21 EPD H 30,314, at

12,712-14; United States v. City of Buffalo, 20 EPD 11 30,111 * *

[FOOTNOTE FOR NEXT PAGE] 7~* The term "minorities" is intended to refer to

Blacks, Hispanics, and women jointly.

-36-

17

NEF.cbmj

• 05-8586

(W.D.N.Y. Dec. 11, 1978). Cf. United Steelworkers of

America v. Weber, 99 S. Ct. 2721 (1979); Regents of the

University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978)

("Bakke'').

Absent discriminatory recruitment and/or selection

procedures minorities* would be expected to comprise

approximately the same percentage of the defendant Cities'

firefighting forces as they constitute of the relevant labor

force in those Cities. See International Brotherhood of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 340 n. 20 (1977).

Since they do not, affirmative relief is required to ensure

that the effects of past discrimination are eliminated.

E.g., United States v. City of Miami, supra, EPD U 30,822,

at 15,248. The Constitution does not require that relief

from discrimination be color or sex blind, Id.; see Bakke,

supra, 438 U.S. at 336, and indeed, race has been considered

in numerous contexts. See, e.g., United Jewish

Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) ; McDaniel v.

Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971).

[FOOTNOTE APPEARS ON PREVIOUS PAGE.]

-37-

- NEF:bmj

• * 05-8586

I*

In this case, there have been no women hired by

the defendant Cities in their firefighting forces and the

number of Blacks and Hispanics is well below the proportion

of these groups in the relevant labor market of each City

according to the 1970 Census. A3 a result, the Department

of Justice made a determination that this and other evidence

demonstrated a pattern and practice of employment discrimina

tion by the defendant Cities. (Complaint, 1W 7-9, 14-16).

By signing its Consent Judgment, the Department of Justice

states its approval of remedial hiring goals to alleviate

the past practices. In this context, the Court's approval

of the goals is warranted. See United States v. City of

Miami, supra, 22 EPD 1f 30,822, at 15,249; compare e. g. ,

Dennison v. City of Los Angeles Department of Water & Power,

22 EPD 11 30,575 (C.D. Cal. Dec. 20, 1979), at 14,096.*'

* The plaintiffs in the Vulcan case similarly reached

the conclusion that the hiring goals were appropriate and

the provision in their Consent Judgment should be approved

as fair, lawful and in furtherance of public policy.

-38-

N£F: bmj

05-8586

C . Recruitment and Training

The Consent Judgments provide for the development

and implementation of "an active and continuing recruitment

program to attract and increase Black, Hispanic and women

applicants for the position of firefighter" (H VII ).*

Various provisions are included with the purpose of enabling

as many minorities to apply for the position of firefighter

as possible. Among these provisions are establishment of a

substantial period for filing of applications for taking the

next written test (scheduled to be given in September, 1980)

Of VII(A)(1)); wide availability of application forms

(H VII(A)(2)); easily accessible places for the filing of

application forms (fl VII(A)(3)); and easy access to

information for prospective applicants (1f VII(A)(4)). In

addition, efforts to stimulate minorities' interest in the

job of firefighting are to be made by means of a media

campaign and a grass roots appeal through educational

institutions and civic and religious organizations with

large minority enrollment or membership (1I1F VII(B)(1), (2)).

Moreover, to assist in the retention of minorities on the

eligible list during the appointment process, notices are to

be sent to plaintiffs of the offer of appointment to any

* In the Vulcan Consent Judgment, these matters are

set forth in Paragraph X, which refers only to Blacks.

All citations hereinafter in this section of the memorandum

are to the relevant paragraphs in the Government's Consent

Judgment.

-39-

NEFrbmj

05-8586

minority person 10 days before the appointment is to be

made. This will enable plaintiffs to advise and encourage

such candidates to accept the offered appointments.

Finally, there are to be initiated various training programs

in each of the defendant Cities to assist applicants in

familiarizing themselves with the procedures and forms for

taking the qualifying examinations given by the defendant

Cities (1T VII(B) (4)) .*

These recruitment provisions are fully appropriate

and reasonable means of assisting in the eradication of past

discrimination. They seek to increase the number of

minorities that apply for positions with defendant Cities.

Moreover, they have been drafted by the parties to permit

the Cities maximum flexibility in using their own resources

as well as available outside assistance.

These procedures are in no way exclusionary; they

do not prevent anyone of any race, national origin or sex

from applying for appointment. Moreover, the recruitment

program is not limited to minorities, but rather is directed

at places where minorities are likely to learn of the

* As part of the training and recruitment, defendant

Cities are to include, if possible, a Black, Hispanic or

woman firefighter or officer in its recruitment program

(1T VII(B) (5)).

-40-

N£F:bmj

05-8586

r^.

message, namely, that defendant Cities are interested and

willing to hire qualified minorities. They do not change

the standards of selection and to not adversely affect any

groups of people. Recruitment devices such as these are

well known and eminently fair means to combat the effects of

prior discrimination. See, e.g., United States v. Georgia

Power Co., 474 F.2d 906, 925-26 (5th Cir. 1973); United

States v. City of Miami, supra, 22 EPD H 30,822, at

15,253-54; United States v. City of Alexandria, supra, 22

EPD U 30,829, at 15,302; United States v. State of New York,

supra, 21 EPD 11 30,314, at 12,714-15; United States v. City

of Buffalo, 20 EPD 1f 30,112 (W.D.N.Y. Dec. 11, 1978).

The training provisions similarly are appropriate

to assist in the achievement of the policies underlying

Title VII. The training will simply familiarize applicants

with the testing procedures and thus eliminate certain of

the unwanted side-effects derived from of applicants' lack

of knowledge of the scope of the material being tested or

lack of understanding of the test procedures. The training

sessions are open to all applicants and thus obviously can

not unduly adversely affect any one group more than another.

Accordingly, these provisions are fair and reasonable.

-41-

m

V NEF:bmj C* ^

. 05-8586

D . Selection Procedures

1. Longrange Improvement

of Written Tests_____

The defendant Cities historically have utilized

witten examinations developed by the State for the purpose

of initial screening of applicants for the positions of

firefighter, fire lieutenant and fire captain. The statis

tical evidence is that these examinations have extreme

adverse impact on Blacks and Hispanics. However, there is

little evidence in the record that demonstrates the

job-relatedness (i.e., "validity") of these examinations,

under Title VII and the Uniform Guidelines. 43 Fed. Reg.

38290 (1978). To overcome this deficiency in defendants'

procedure, to enable plaintiff to evaluate the examinations'

validity, and to improve the defendant Citied abilities to

screen applicants, the parties included in the Consent

Judgments extensive provisions for the conduct of (i) job

analyses of each position for which they intend to

administer a written test and (ii) performance rating

surveys for those jobs (11 III).*

* These provisions are contained in Paragraph IV of

the Vulcan Consent Judgment. References herein are to

the Government's Consent Judgment.

-42-

NEF: bmj

. . 05-8586

The job analyses, which may be performed by the

defendant Cities individually or in cooperation with one

another and the State, shall "review the existing job

descriptions for each title to assure that the descriptions

reflect job content for test purposes" (H 111(A)(1)). The

State is required to provide assistance through appropriate

personnel for up to 40 hours for each job description being

analyzed (1ffl 111(A)(1)(a), (b)), and the analyses shall be

completed within the relatively short period of one year for

firefighters and 1 1/2 years for fire lieutenant and fire

captain jobs (H 111(A)(1)(c)). The State thereafter shall

correlate the information from the job analyses and create a

single job description, which may also be based upon

information from other municipalities within New York State

(11 111(A)(1)(d)).

The job analyses are the fundamental prerequisite

to development of a test for selection among applicants and

to consideration of the issue of actual validity of any test

that is created to measure candidates’ aptitudes or abilities

to perform the jobs they seek. Uniform Guidelines, §§

14A,(2), C(2), D(2); e.g■, Kirkland v. New York State

Department of Correctional Services, supra, 520 F.2d at

-43-

NEF:jcj

05-8586

m.'

426; Vulcan Society of New York City Fire Department v.

Civil Service Commission, supra, 490 F.2d at 396. Moreover,

no one will suffer any conceivable detriment from the crea

tion of the new job descriptions.*

The Consent Judgments also require that the defen

dant Cities and State cooperatively conduct task performance

rating surveys. These surveys consist of completion by fire

officers of written questionnaires regarding job performance

by firefighters and fire officers. The information is to be

compiled in a manner that will permit comparison with test

scores on current written tests for those jobs (H 111(A)(2)).

The task performance rating surveys are to be completed

within 1 1/2 years for both firefighters and fire officers.**

* The fact that a job analysis by Dr. Marvin Dunnette may

have been performed will of course by relevant to the new job

analysis, but it is not dispositive.

** Surveys about firefighters are to be completed within

one year (11 111(A)(2)(a) (i)).

NEF:jcj

05-8586

■ f t a t 'M

The questionnaires are to be analyzed by the State and

correlated with written test results for the firefighters

and fire officers who are evaluated by the surveys. The

resulting findings are to be the basis of further improve

ment of the written tests for each job. The State is also

permitted to utilize in its evaluation of the performance

surveys information from other New York municipalities.*

These surveys, as with improvements to the job

descriptions described above, can only assist in the effec

tive functioning of defendants' fire departments and do not

adversely affect any groups of people. Thus, there can be

no reason for the Court to withhold approval of this provi

sion of the Consent Judgments.

* The information gleaned from these surveys will be

confidential and exempt from disclosure under any freedom of

information laws (1T 111(A)(2)(e)).

-45-

y

NEF:jcj

05-8586

If defendants fail to comply with the foregoing

provisions or the studies performed under those provisions

fail to result in development of written tests without

adverse impact, the Consent Judgments provide that the

parties shall negotiate to reach a solution to the problem

(H 111(B)). If negotiations are unsuccessful, then plaintiffs

may petition the Court for appropriate relief regarding future

written tests (Id.). This provision is included in the

Consent Judgments as a safety valve, and permits the parties

to incorporate new concepts of industrial psychology and

testing theory into their solutions. It also permits access

to the Court, as a last resort, after a specific and narrow

is

issue/identified.

Accordingly, these provisions are lawful and fair,

and should be approved as a valid terms in the Consent

Judgments.

-46-

NEF:jcj

05-8586

'F'< /C--

2. Interim Relief Concerning Written Tests

The Consent Judgments provide for the use in

September, 1980 of a written test created by the State for

the selection of firefighters, and for written tests periodi

cally thereafter for both firefighters and fire officers.

The parties all acknowledge a need for defendant Cities to

select new firefighters within the next few years. However,

the written tests previously used were unlawful under Title

VII since those tests had an adverse impact and defendant

Cities' selection of applicants on the basis of the test

results discriminated against Blacks and Hispanics.* See

Uniform Guidelines § 4C. Nevertheless, because test valida

tion is extremely complicated, it was deemed infeasible to

* The terms "adverse impact" and "validate" have technical

meanings that must be kept in mind in this discussion. The

Uniform Guidelines define "adverse impact" as

A substantially different rate of

selection in hiring, promotion,

or other employment decision

which works to the disadvantage

of members of a race, sex, or

ethnic group.

It is evidence of adverse impact if the "four-fifths rule"

(also known as the "eighty percent [80%] rule") is violated.

This rule is that

[FOOTNOTE CONTINUED ON FOLLOWING PAGE]

-47-

NEF:jcj

05-8586 'a

validate any written examination within the available time

before the September, 1980 test.* Since defendants consider

a written test to be a requirement of the selection process,

the parties determined that modified use of the written test

would be appropriate. See Uniform Guidelines §§ 6A (use of

alternative selection procedures to eliminate adverse impact),

[FOOTNOTE CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS PAGE]

A selection rate for any race, sex,

or ethnic group which is less than

four-fifths ... of the rate for the

group with the highest rate will

generally be regarded by the Federal

enforcement agencies as evidence of

adverse impact ...

Id. § 4D. Once adverse impact is shown to result from use

oT a selection procedure, the defendant must produce evidence

of the "validity" (i.e, , job-relatedness) of the procedure.

Validity is shown if the selection procedure has been "validated."

The Uniform Guidelines define "validate" in this context to

be

A demonstration that one or more

validity study or studies meeting

the standards of these guidelines

has been conducted, including

investigation and, where appropriate,

use of suitable alternative selection

procedures ... and has produced

evidence of validity sufficient to

warrant use of the procedure for the

intended purpose under the standards

of those guidelines.

* Indeed, it is unknown precisely when a validated examina

tion will be available.

-48-

NEF:jcj

05-8586 SS* ' »J

6B(2) (modification of selection procedure to eliminate

adverse impact if validation techniques not feasible)). This

consensus among the parties as to the September, 1980 test and

written tests thereafter until the hiring goals are met is

embodied in the Consent Judgments in paragraph 11(B).*

In essence, the parties have agreed that a

written test similar to those previously administered by

defendants may be given for selection of firefighters

(11 11(B)(1)(g); See 1111 11(B)(1)(h), (i)) ;** See N.Y. Civil

Service Law, Regulations, Part 67). The parties have sought

to eliminate any adverse impact the future tests may have by

modifying the scoring procedure. Each question on the test

will be analyzed individually. If the success rate on a

given question for all applicants in the State of New York

who specify their racial/ethnic group as Black or Hispanic

(and who complete the test and who answer the test question)

is less than 80% of the rate of success on that question for

* See terms of the Consent Judgments as to Promotions,

discussed at Section D(6) of this Memorandum, infra.

** The defendant Cities may elect under the Consent Judg

ments and state law (N.Y. Civil Service Law §§ 17(A), 23) to

prepare (or have prepared by third parties) a written test

without the aid of the State.

-4 9-

. NEF:jcj

05*8586

the group of applicants in the State who identify themselves

as being other than Black or Hispanic (and who complete the

test and answer the question), then that question shall not

be counted in scoring the test for the purpose of determining

who passed.* The passing score on the written tests shall

be 70%, as provided by New York State Department of Civil

Service Regulations, Part 67 (1f 11(B)(1)(e)).

The Consent Judgment in Paragraph 11(B)(1)(f)

contains a further safeguard against adverse impact. If the

overall proportion of Blacks and Hispanics who score over

* In the unlikely event that the number of applicants who

specify their racial/ethnic group as Black or Hispanic is