University of Tennessee v. Elliott Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. University of Tennessee v. Elliott Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1985. c9cbb6df-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5d94d787-f363-4b84-9b6d-0e4ab9c5968f/university-of-tennessee-v-elliott-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

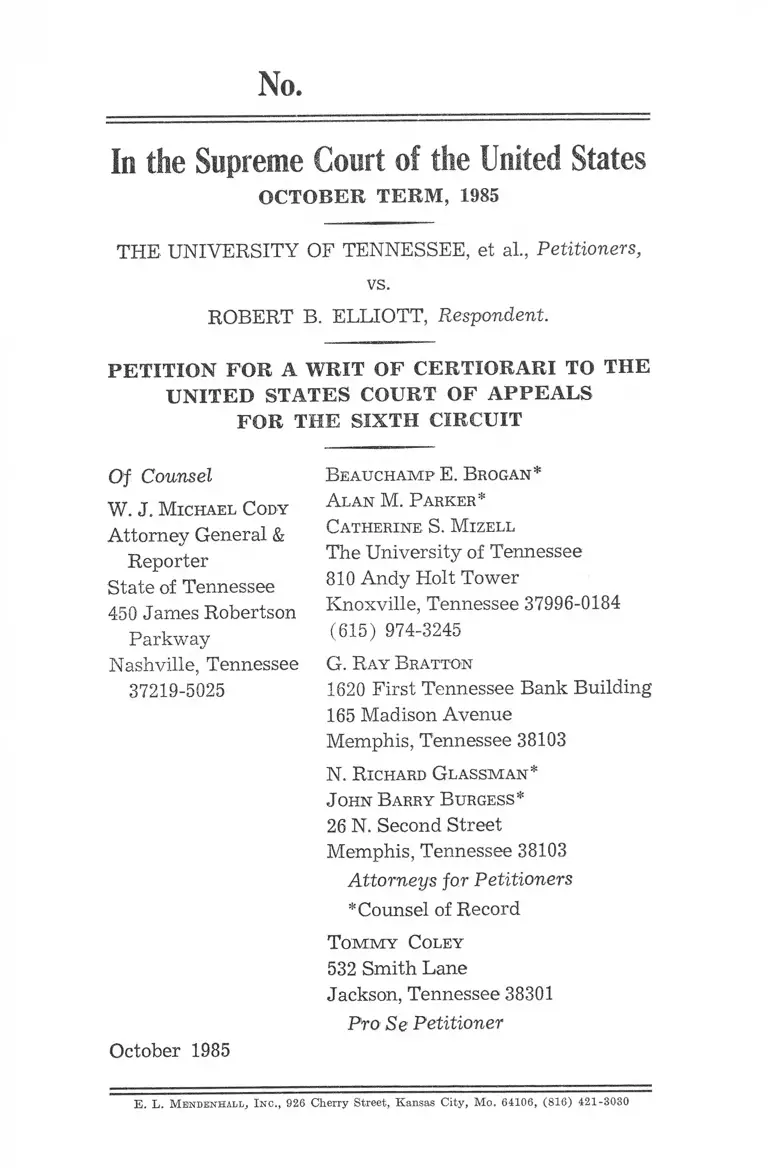

No.

In the Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, et al., Petitioners,

vs.

ROBERT B. ELLIOTT, Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Of Counsel

W. J. M ichael C ody

Attorney General &

Reporter

State of Tennessee

450 James Robertson

Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee

37219-5025

B eauchamp E. B rogan*

A lan M. P arker*

Catherine S. M izell

The University of Tennessee

810 Andy Holt Tower

Knoxville, Tennessee 37996-0184

(615) 974-3245

G. R ay B ratton

1620 First Tennessee Bank Building

165 Madison Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

N. R ichard G lassm an *

J ohn B arry B urgess*

26 N. Second Street

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Attorneys for Petitioners

* Counsel of Record

T o m m y Coley

532 Smith Lane

Jackson, Tennessee 38301

Pro Se Petitioner

October 1985

E. L. M endenhall, I n c ., 926 Cherry Street, Kansas City, M o. 64106, (816) 421-3030

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether traditional principles of preclusion apply

in an action under Title VII, section 1983, and other civil

rights statutes to preclude issues fully and fairly litigated

before a state administrative agency acting in a judicial

capacity.

II

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTION PRESENTED .......... I

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...... ......... ............... ............ m

OPINIONS BELOW .... 1

JURISDICTION ..................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE C A SE...... ............. ...................... 2

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT ................... 4

1. THE DECISION BELOW CONFLICTS WITH

DECISIONS OF THIS COURT CONCERNING

THE PRECLUSIVE EFFECT OF ADMINIS

TRATIVE ADJUDICATIONS AND THE AP

PLICATION OF TRADITIONAL PRINCIPLES

OF PRECLUSION IN SUBSEQUENT SECTION

1983 ACTIONS ....... .............. -........... - ........... -..... - 4

2. THE DECISION BELOW CONFLICTS WITH

DECISIONS OF OTHER COURTS OF AP

PEALS CONCERNING THE PRECLUSIVE

EFFECT OF STATE ADMINISTRATIVE AD

JUDICATIONS IN SUBSEQUENT FEDERAL

CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIONS ....... ................- ........ 7

3. THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE DECISION

BELOW AND THE DECISIONS OF THIS

COURT AND OTHER COURTS OF APPEALS

CONCERNS A MATTER OF NATIONAL IM

PORTANCE .................................................. 11

CONCLUSION ................................................................... 12

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Allen v. McCurry, 449 U.S. 90 (1980) ........ ................. - 6

Bottini v. Sadore Management Corp., 764 F.2d 116 (2d

Cir. 1985) ....................... ....... ................ - ---- ----------------- 10

Buckhalter v. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers, Inc., 768

F.2d 842 (7th Cir. 1985) ................... ......... ........ ..... . 7, 8

Elliott v. University of Tennessee, 766 F.2d 982 (6th

Cir. 1985) ............ ............................................................ 1

Fourakre v. Perry, 667 S.W.2d 483 (Tenn. App. 1983) 7

Heath v. John Morrell & Co., 768 F.2d 245 (8th Cir.

1985) ........ ............................... - - - ................................--- 10

Kremer v. Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S. 461

(1982) ................................... -............... ....... 5,6,7,8,9,10,11

Migra v. Warren City School District, ------ U.S..........,

104 S. Ct. 892 (1984) ...............................- ........ ....... 6

Moore v. Bonner, 695 F.2d 799 (4th Cir. 1982) ........... 10

O’Hara v. Board of Education, 590 F. Supp. 696 (D.N.J.

1984), affd mem., 760 F.2d 259 (3d Cir. 1985) ....... 7,9

Polsky v. Atkins, 197 Tenn. 201, 270 S.W.2d 497 (1954) 7

Purcell Enterprises, Inc. v. State, 631 S.W.2d 401

(Tenn. App. 1981) ........................................................... 7

Ross v. Communications Satellite Corp., 759 F.2d 355

(4th Cir. 1985) ..................................................... .... -..... 10

Steffan v. Housewright, 665 F.2d 245 (8th Cir. 1981) .... 10

United States v. Utah Construction & Mining Co., 384

U.S. 394 (1966) ........ ........... .............-......................................-............ 4,5

Zanghi v. Incorporated Village of Old Brookville, 752

F.2d 42 (2d Cir. 1985) 10

IV

Federal Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) (1964) .............................................. 2

28 U.S.C. § 1738 (1964) ..................................................9, 10

State Statutes:

Tenn. Code Ann. §§ 4-5-301 through -323 (Supp. 1984) 2

Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-322 (Supp. 1984) ...................... 3, 4

Miscellaneous:

18 C. Wright, A. Miller & E. Cooper, Federal Practice

and Procedure § 4403 (1981) ...................................... 11

1 K. Davis, Administrative Law Treatise § 1:10 (1983) 11

No.

In the Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, et al., Petitioners,

vs.

ROBERT B. ELLIOTT, Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners1 respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment and opinion of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit entered

in this proceeding on July 9, 1985.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported in

766 F.2d 982 (6th Cir. 1985), and a copy of the slip opin

ion appears in the Appendix hereto. The memorandum

1. Petitioners are the defendants below—The University of

Tennessee, The University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture,

The University of Tennessee Agricultural Extension Service,

University officials (M. Lloyd Downen, Willis W. Armistead,

Edward J. Boling, Haywood W. Luck, and Curtis Shearon), mem

bers of the Madison County Agricultural Extension Service

Committee (Billy Donnell, Arthur Johnson, Jr., Mrs. Neil Smith,

Jimmy Hopper, and Mrs. Robert Cathey), Murray Truck Lines,

Inc., Tom Korwin, and Tommy Coley. Petitioner Coley is appear

ing pro se.

2

decision of the United States District Court for the West

ern District of Tennessee and the final agency order in

the contested case hearing under the Tennessee Uniform

Administrative Procedures Act also appear in the Ap

pendix hereto.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit was entered on July 9, 1985, and this petition for

certiorari was filed within ninety days of that date. This

Court’s jurisdiction is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1)

(1964).

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The University of Tennessee is an agency of the State

of Tennessee, and respondent is a black employee of the

University’s Agricultural Extension Service. The Uni

versity proposed to terminate respondent’s employment

for disciplinary reasons. Respondent elected to contest the

proposed termination in a hearing under the Tennessee

Uniform Administrative Procedures Act, Tenn. Code Ann.

§§ 4-5-301 through -323 (Supp. 1984). Before the hear

ing was held, however, respondent filed this action under

Title VII and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983, 1985, 1986, and 1988,

seeking an injunction against any action with respect to

his employment, one million dollars in damages, and certifi

cation of a class action. The district court did not certify

a class. After entry and dissolution of a temporary re

straining order, the district court ruled that respondent

had failed to meet the prerequisites for preliminary in

junctive relief and removed any restraint regarding em

ployment action against respondent. Respondent elected

3

to proceed with the administrative hearing and did not

seek further action in federal court.

In compliance with the Administrative Procedures

Act, respondent’s hearing was conducted with complete trial

rights including discovery, subpoenas, representation by

counsel, examination and cross-examination of witnesses,

and filing of pleadings, briefs, and proposed findings of

fact. The administrative record consists of 55 volumes with

over 5,000 pages of testimony from over 100 witnesses and

159 exhibits. Respondent insisted that evidence of alleged

racial discrimination be admitted in the administrative

hearing. The University objected that this evidence

should be introduced instead in respondent’s Title VII

action. Despite this objection, the Administrative Law

Judge admitted voluminous evidence of alleged racial dis

crimination against respondent. Nonetheless, the Admin

istrative Law Judge found that the proposed termination

was not racially motivated. Finding further, however, that

the University’s proof was insufficient to warrant respon

dent’s termination, the Administrative Law Judge or

dered that respondent be transferred to another county

under new supervisors. The findings of the Administrative

Law Judge were affirmed on appeal to the Agency Head.

Tenn. Code. Ann. § 4-5-322 (Supp. 1984) provides for

judicial review of a final agency order upon the filing

of a petition within sixty days of the order. Respondent

failed to file a petition for judicial review within sixty

days. Instead, after his transfer had been accomplished

and eighty-four days after the final agency order, respon

dent filed a motion in the district court for a temporary

restraining order, preliminary injunction, and stay of the

final agency order. The University defendants opposed

the motion and amended their earlier motion for summary

judgment. In granting summary judgment for the de

4

fendants, the district court held that it lacked subject

matter jurisdiction under Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-322 (Supp.

1984) to review the merits of the final agency order and

that it was otherwise precluded by res judicata principles

from reviewing the issues fully litigated in the administra

tive hearing. The Sixth Circuit reversed, holding that a

final state administrative judgment is never entitled to

preclusive effect in a subsequent federal court action under

either Title VII or section 1983.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

1. THE DECISION BELOW CONFLICTS WITH

DECISIONS OF THIS COURT CONCERNING

THE PRECLUSIVE EFFECT OF ADMINISTRA

TIVE ADJUDICATIONS AND THE APPLICA

TION OF TRADITIONAL PRINCIPLES OF PRE

CLUSION IN SUBSEQUENT SECTION 1983

ACTIONS.

In United States v. Utah Construction & Mining Co.,

384 U.S. 394 (1966), this Court held that traditional prin

ciples of res judicata are applicable to administrative pro

ceedings “ [wjhen an administrative agency is acting in

a judicial capacity and resolves disputed issues of fact

properly before it which the parties have had an adequate

opportunity to litigate.. . .” Id. at 422. Applying this prin

ciple to the facts in Utah, this Court concluded as follows:

[T]he Board was acting in a judicial capacity . . .

the factual disputes were clearly relevant to issues

properly before it, and both parties had a full and

fair opportunity to argue their version of the facts

and an opportunity to seek court review of any ad

5

verse findings. There is, therefore, neither need nor

justification for a second evidentiary hearing on these

matters already resolved as between these two parties.

Id, By holding that traditional principles of res judicata

are applicable to administrative proceedings, this Court

recognized the modem model of administrative procedure

which often closely approximates judicial procedure and

thus merits the same finality.

In the decision below, the Sixth Circuit acknowledge^

the holding in Utah but refused to apply it to the question

of whether a final state administrative judgment precludes

relitigation of issues in a federal civil rights action. The

court treated the holding as limited to the res judicata

effect of federal administrative decisions in subsequent

federal court proceedings. Appendix at A14-15, A18.

There is nothing in this Court’s opinion in Utah, however,

to suggest that the holding is so limited. This Court

expressly invoked general principles of res judicata and

described their application to “an administrative agency

acting in a judicial capacity” without use of the delimiting

term “ federal agency.” Id. at 421-422. Moreover, in

Kremer v. Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S. 461

(1982), this Court cited the Utah holding approvingly in

considering the adequacy of state proceedings to be given

preclusive effect in a subsequent Title VII action:

Certainly, the administrative nature of the fact

finding process is not dispositive. In United States

v. Utah Construction & Mining Co. [citation omitted],

we held that, so long as opposing parties had an ade

quate opportunity to litigate disputed issues of fact,

res judicata is properly applied to decisions of an ad

ministrative agency acting in a “ judicial capacity”

[citation omitted].

6

Id. at 484-485 n.26. The Sixth Circuit clearly erred,

therefore, in failing to follow this Court’s opinion in Utah

and to apply traditional principles of res judicata to the

final administrative judgment in this case.

Furthermore, the failure of the Sixth Circuit to follow

the Utah holding leads to a conflict between the decision

below and the opinion of this Court in Allen v. McCurry,

449 U.S. 90 (1980). In Allen, this Court held that nothing

in the language or legislative history of section 1983 sug

gests a congressional intention to contravene traditional

doctrines of preclusion. Id. at 97-98. In so holding, this

Court rejected the suggestion “that every person asserting

a federal right is entitled to one unencumbered opportu

nity to litigate that right in a federal district court, re

gardless of the legal posture in which the federal claim

arises.” Id. at 103. This Court reaffirmed Allen in Migra

v. Warren City School District, ....... U.S........, 104 S. Ct.

892 (1984), extending application of res judicata principles

in section 1983 actions from the issue preclusion rule of

Allen to preclusion of the claim itself. The Sixth Circuit’s

refusal to give preclusive effect to the final administrative

judgment in this case rests, however, on the assumption

that “ Congress provided a civil rights claimant with a

federal remedy in a federal court, with federal process,

federal factfinding, and a life-tenured judge.” Appendix

at A20. This assumption cannot be reconciled with this

Court’s holding in Allen and Migra that section 1983 cre

ates no exception to traditional rules of preclusion, which

are applicable, according to the Utah holding, to admin

istrative adjudications as well as judicial proceedings.2

2. The decision below also conflicts in principle with the

holding in Allen and Migra that the preclusive effect of state

court proceedings in subsequent section 1983 actions is governed

(Continued on following page)

7

2. THE DECISION BELOW CONFLICTS WITH

DECISIONS OF OTHER COURTS OF APPEALS

CONCERNING THE PRECLUSIVE EFFECT

OF STATE ADMINISTRATIVE ADJUDICA

TIONS IN SUBSEQUENT FEDERAL CIVIL

RIGHTS ACTIONS.

In refusing to give preclusive effect to the final ad

ministrative judgment of the state agency in this case,

the Sixth Circuit conceded that its decision conflicts with

that of other circuits. Appendix at A24-25. Although

the court conceded conflict only with respect to the ap

plication of preclusion principles in civil rights actions

under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, the decision also conflicts with

decisions of the Third and Seventh Circuits in Title VII

actions. See Buckhalter v. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers,

Inc., 768 F.2d 842 (7th Cir. 1985) (slip op. in Appendix

at A185); O’Hara v. Board of Education, 590 F. Supp. 696

(D.N.J. 1984), affd mem., 760 F.2d 259 (3d Cir. 1985).

In refusing to apply principles of res judicata to pre

clude respondent’s Title VII action, the Sixth Circuit held

that the issue was controlled by the following general

principle stated by this Court in footnote 7 of Kremer v.

Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S. 461, 470 (1982):

“ [Ujnreviewed administrative determinations by state

agencies . . . should not preclude . . . [de novo] review

Footnote continued—

by the state’s own law of res judicata. The Sixth Circuit failed

even to consider whether the state administrative adjudication in

this case would have been afforded preclusive effect in the

courts of the State of Tennessee. If the Sixth Circuit had looked

to the law of res judicata in Tennessee, it would have found

that an administrative adjudication by a state agency acting in

a judicial capacity is entitled to preclusive effect in Tennessee

courts. See Polsky v. Atkins, 197 Tenn. 201, 270 S.W.2d 497

(1954); Fourakre v. Perry, 667 S.W.2d 483 (Tenn. App. 1983);

Purcell Enterprises, Inc. v. State, 631 S.W.2d 401 (Tenn. App.

1981) .

8

[in federal court] even if such a decision were to be af

forded preclusive effect in a State’s own courts.” The

Sixth Circuit rejected petitioner’s argument that this

general principle, considered in the light of this Court’s

citation of the Utah holding with approval in footnote 26,

must be construed to apply only with respect to admin

istrative decisions rendered by agencies possessing in

vestigatory rather than adjudicatory authority. Appen

dix at A12-13. With respect to respondent’s action under

42 U.S.C. § 1983 and the other Reconstruction Civil Rights

Statutes, the Sixth Circuit first concluded that the Utah

holding does not apply in the state-to-federal context and

then refused to create, as it put it, a rule of administrative

preclusion in section 1983 actions. Appendix at A20.

Less than two weeks after the Sixth Circuit’s decision

in this case, the Seventh Circuit decided Buckhalter v.

Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers, Inc., 768 F.2d 842 (7th Cir.

1985) (slip op. in Appendix at A185). The decision below

directly conflicts with the Seventh Circuit’s opinion on the

question presented by this petition. Like the present case,

Buckhalter involved both a Title VII action and an action

under 42 U.S.C. § 1981. Beginning with this Court’s ac

knowledgement of “ administrative res judicata” in foot

note 26 of the Kremer opinion, the Seventh Circuit con

sidered the Utah criteria to determine whether principles

of res judicata should be applied to plaintiff’s Title VII

action. Finding that the state administrative agency had

acted in a judicial capacity and that both parties had had

a full and fair opportunity to litigate their case, the Seventh

Circuit concluded that principles of res judicata should

be applied to determine whether the plaintiff’s Title VII

action was precluded by the prior administrative proceed

ing. Appendix at A200-206. Unlike the Sixth Circuit in

the decision below, the Seventh Circuit expressly rejected

9

a broad interpretation of footnote 7 of the Kremer opin

ion, concluding that it applied only to judicially unre

viewed administrative decisions by agencies exercising

investigatory rather than adjudicatory authority. The

court noted that a narrow interpretation of footnote 7 is

supported by this Court’s approving citation of the Utah

holding in footnote 26 of the same opinion. Appendix at

A208-210. Finally, the Seventh Circuit held that the

principles of “ administrative res judicata” are applicable

to civil rights actions brought under section 1981 as well

as Title YII and thus dismissed the plaintiff’s claims

under both statutes. Appendix at A212. The decision

below is thus squarely and irreconcilably in conflict with

the Seventh Circuit’s decision in Buckhalter.

With respect to respondent’s Title VII action, the de

cision below is also squarely and irreconcilably in con

flict with the Third Circuit’s decision in O’Hara v. Board

of Education, 590 F. Supp. 696 (D.N.J. 1984), affd mem.,

760 F.2d 259 (3d Cir. 1985). In determining whether a

federal court may give collateral estoppel effect to a state

administrative agency decision, the district court in O’Hara

looked not only to the Utah criteria of whether the agency

was acting in a judicial capacity and whether the parties

had an adequate opportunity to litigate the issues but

also to whether a state court would give preclusive effect

to the administrative decision. Id. at 701. The O’Hara

court thus relied in part on the full-faith-and-credit re

quirement of 28 U.S.C. § 1738 (1964). In the decision be

low, however, the Sixth Circuit summarily rejected any ap

plication of traditional principles of full-faith-and-credit

to adjudicatory proceedings before administrative agencies.

Appendix at A ll, A16. Therefore, although the Third

Circuit affirmed the district court decision in O’Hara

without an opinion, its decision must be considered as di

rectly in conflict with the decision below.

10

With respect to respondent’s action under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983 and the other Reconstruction statutes, the decision

below directly conflicts with decisions of the Second and

Eighth Circuits. In Zanghi v. Incorporated Village of Old

Brookville, 752 F.2d 42 (2d Cir. 1985), the Second Circuit

held that a prior finding of probable cause to arrest by

an administrative law judge precluded the plaintiff’s section

1983 action for false arrest, false imprisonment, and malici

ous prosecution. The Second Circuit based its holding on

this Court’s opinion in Utah. Similarly, in Steffan v.

Housewright, 665 F.2d 245 (8th Cir. 1981), the Eighth Cir

cuit relied on the Utah holding to preclude the plaintiff’s

due process claims under section 1983. The Sixth Circuit’s

refusal to apply the Utah holding in a section 1983 action

thus presents a clear conflict with decisions by the Second

and Eighth Circuits.

On the other hand, the Second and Eighth Circuits

have failed to give preclusive effect to state administrative

proceedings in subsequent Title YII actions, relying on

footnote 7 of this Court’s opinion in Kremer. See Heath

v. John Morrell & Co., 768 F.2d 245 (8th Cir. 1985); Bottini

v. Sadore Management Corp., 764 F.2d 116 (2d Cir. 1985).

Similarly, the Fourth Circuit has held in a Title VII action

that “unreviewed administrative determinations by state

agencies do not preclude a trial de novo in federal court.”

Ross v. Communications Satellite Corp., 759 F.2d 355, 361

n.6 (4th Cir. 1985). In an earlier decision, Moore v. Bonner,

695 F,2d 799 (4th Cir. 1982), the Fourth Circuit had failed

to give preclusive effect to a state administrative judg

ment in a subsequent section 1983 action, holding that

preclusion is not required by the full-faith-and-credit re

quirement of 28 U.S.C. § 1738 (1964) and failing to address

this Court’s decision in Utah.

These decisions from the Second, Third, Fourth, Sev

enth and Eighth Circuits, together with the Sixth Circuit’s

11

decision below, demonstrate that a serious and continuing

conflict exists among the courts of appeals on the question

presented by this petition. Moreover, the conflict has

become particularly intense since this Court’s 1982 de

cision in Kremer, with much of the debate centering on

inferences to be drawn from footnotes 7 and 26 of that

opinion. This important question of federal law should

be decided by this Court. The existing conflict will not

abate in the absence of a decision by this Court.

3. THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE DECISION

BELOW AND THE DECISIONS OF THIS COURT

AND OTHER COURTS OF APPEALS CONCERNS

A M ATTER OF NATIONAL IMPORTANCE.

The Sixth Circuit’s decision in this case seriously un

dermines the finality of state administrative proceedings

and encourages repetitious litigation. It thus contravenes

both the public interest in judicial economy and the pri

vate interest in repose underlying the doctrine of res

judicata. See 18 C. Wright, A. Miller & E. Cooper, Federal

Practice and Procedure § 4403 (1981). It produces the

possibility of conflicting results on the same issue and

burdens the federal courts with the necessity of hearing

issues which have already been litigated fully and fairly

between the parties.

Moreover, many states have enacted administrative

procedures acts which are similar to the one in this case.

See 1 K. Davis, Administrative Law Treatise § 1:10 (1983).

The adjudicatory nature of contested case hearings under

these acts may be virtually identical to that of federal

and state courts, as was true in this case. Therefore, the

significance of the Sixth Circuit’s refusal to enforce repose

when respondent elected to pursue his claims under the

formal adjudicative procedure established by state law—-

and then failed to pursue judicial review provided by

12

state law—goes far beyond the particular facts and parties

in this case. It calls into serious question the validity of

the modern model of administrative procedure as a mech

anism for resolution of disputes, especially disputes be

tween employers and employees.

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, a writ of certiorari should issue

to review the judgment and opinion of the Sixth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

Of Counsel

W. J. M ichael C ody

Attorney General &

Reporter

State of Tennessee

450 James Robertson

Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee

37219-5025

B eaucham p E. B rogan*

A lan M. P arker*

Catherine S. M izell

The University of Tennessee

810 Andy Holt Tower

Knoxville, Tennessee 37996-0184

(615) 974-3245

G. R ay B ratton

1620 First Tennessee Bank Building

165 Madison Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

N. R ichard G lassm an *

J ohn B arry B urgess*

26 N. Second Street

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Attorneys for Petitioners

* Counsel of Recor d

T o m m y Coley

532 Smith Lane

Jackson, Tennessee 38301

Pro Se Petitioner

October 1985