Berger v. Iron Workers Reinforced Rodmen, Local 201 Motion of NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund for Leave to File a Brief Amicus Curiae, and Brief Amicus Curiae, in Support of Appellees Berger, et al.

Public Court Documents

July 10, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Berger v. Iron Workers Reinforced Rodmen, Local 201 Motion of NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund for Leave to File a Brief Amicus Curiae, and Brief Amicus Curiae, in Support of Appellees Berger, et al., 1987. d0c877af-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5d971751-694e-4207-9c25-881324565527/berger-v-iron-workers-reinforced-rodmen-local-201-motion-of-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-for-leave-to-file-a-brief-amicus-curiae-and-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-appellees-berger-et-al. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

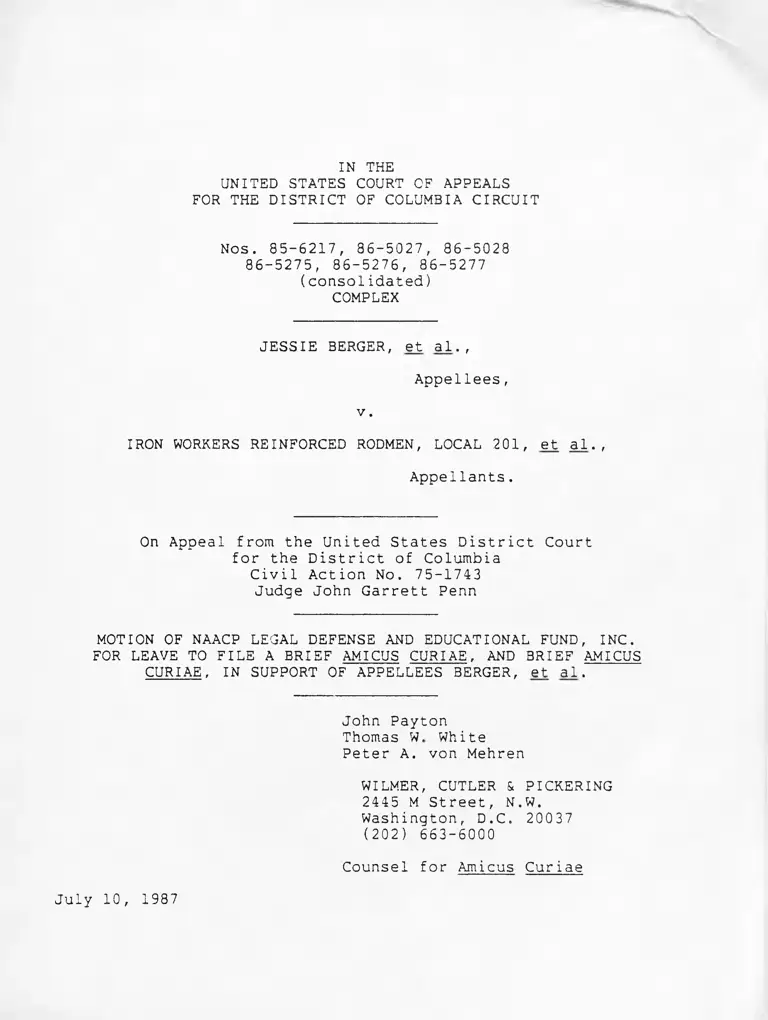

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

Nos. 85-6217, 86-5027, 86-5028

86-5275, 86-5276, 86-5277

(consolidated)

COMPLEX

JESSIE BERGER, et a1.,

Appellees,

v.

IRON WORKERS REINFORCED RODMEN, LOCAL 201, et al. ,

Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

Civil Action No. 75-1743

Judge John Garrett Penn

MOTION OF NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE, AND BRIEF AMICUS

CURIAE, IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES BERGER, et al.

John Payton

Thomas W. White

Peter A. von Mehren

WILMER, CUTLER & PICKERING

2445 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037

(202) 663-6000

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

July 10, 1987

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

Nos. 85-6217, 86-5027, 86-5028

86-5275, 86-5276, 86-5277

(consolidated)

COMPLEX

JESSIE BERGER, et al. ,

Appellees,

v .

IRON WORKERS REINFORCED RODMEN, LOCAL 201, et al.,

Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

Civil Action No. 75-1743

Judge John Garrett Penn

MOTION OF NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE,

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES BERGER, et al.

Pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 28,

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. moves for leave to

file the attached Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Plaintiffs-

Appellees in the above-entitled case.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. is a

non-profit corporation formed to assist Blacks to secure their

constitutional and civil rights by means of litigation. Since

1965 the Fund's attorneys have represented plaintif

hundred employment discrimination actions under Tit

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seg.

§ 1981, and the Fourteenth Amendment. The Fund has

interest in ensuring strict enforcement of the civi

and in securing effective relief for victims of rac

nation.

fs in several

le VII of the

, 42 U.S.C.

a strong

1 rights laws

ial discrimi-

This case is an appeal from a decision of the District

Court in favor of a class of black rodmen, holding that local and

international ironworkers unions, a contractors association with

which the local bargained, and the Apprenticeship and Training

Committees operated jointly by them, discriminated against those

black workers by erecting barriers to their entry into the union.

The Fund believes that the accompanying Brief Amicus Curiae will

be of assistance to the Court by placing this complex case in

perspective. First, the Brief shows that this case is but one

more step in a successful campaign by black construction workers

in this area to eradicate a pervasive pattern of racial discrimi

nation in the construction trades, which has been largely imple

mented through the union hiring hall and referral system devised

and carried out by the unions and the contractors associations

pursuant to collective bargaining agreements. Second, the Brief

demonstrates that the decision of the Court below involves noth

ing more than the straightforward application of well-settled

principles of civil rights law to a set of facts supported by

2

substantial evidence. Thus, while the Brief of Appellees

responds in detail to the various arguments of Appellants,

amicus' purpose in submitting this Brief is to emphasize briefly

that affirmance f the decision below involves no novel questions

or extensions of the law.

WHEREFORE, the Fund respectfully requests that its

Motion for Leave to File Brief amicus curiae be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

j jw u v a j 0^ /

John Payton

Thomas W. White

Peter A. von Mehren

WILMER, CUTLER & PICKERING

2445 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037

(202) 663-6000

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

3

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

Nos. 35-6217, 36-5027, 86-5028

86-5275, 86-5276, 86-5277

• (consolidated)

COMPLEX

JESSIE BERGER, et al.

Appellees,

v.

IRON WORKERS REINFORCED RODMEN, LOCAL 201, et al.

Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

Civil Action No. 75-1743

Judge John Garrett Penn

BRIEF OF NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

AS AMICUS CURIAE, IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES BERGER, et al

John Payton

Thomas W. White

Peter A. von Mehren

WILMER, CUTLER & PICKERING

2445 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037

(202) 663-6000

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

Nos. 85-6217, 86-5027, 86-2028

86-5275, 86-5276, 86-5277

(consolidated)

COMPLEX

JESSIE BERGER, et al. ,

Appellees,

v .

IRON WORKERS REINFORCED RODMEN, LOCAL 201, et al.

Appellants.

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY RULE 8(0 OF

THE GENERAL RULES OF THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

The undersigned, counsel of record for amicus curiae

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, certifies that the fo

lowing listed parties appeared below:

1. Ernest Bellamy, Jessie Berger, Randolph Jackson,

Tommy Kirkland, Van Edward Lewis, Willie Lee McMillan, Ronald

Tucker, and Garrett Simmons.

2. A class including: (1) all black persons who have

applied for or sought, from representatives of Local 201 or the

International, membership in Local 201 and, in connection there

with, the International or who have applied for or sought, from

representatives of Local 201, the Apprenticeship Program and/or

the Training Program and who have been or might be excluded from

Local 201 and, in connection therewith, the International or the

Apprenticeship Program or the Training Program or any of the

above by the alleged discriminatory practices of the defendants

and who could have filed timely charges with the EEOC when their

class representatives filed such charges or who could have filed

timely lawsuits when their class representatives filed the

instant lawsuit; and (2) all black persons who have, been referred

for employment by any means, including filling out a referral

slip, causing Local 201 to fill out a referral slip, or pres

enting themselves at Local 201 and requesting representatives of

Local 201 to refer them for work, and who have been or might be

discouraged from applying for membership in Local 201 and, in

connection therewith, the International and/or the Apprenticeship

Program and/or the Training Program by the alleged racially

discriminatory practices of the defendants and who could have

filed timely charges with the EEOC when their class representa

tives filed such charges or who could have filed lawsuits when

their class representatives filed the instant lawsuit.

2

3. Iron Workers Reinforced Rodmen Local 201 (herein

after, "Local 201").

4. International Association of Bridge, Structural

and Ornamental Iron Workers (hereinafter, "International").

5. Apprenticeship Committee for Iron Workers Rein

forced Rodmen, Local 201 (hereinafter, "Apprenticeship Commit

tee" ) .

6. Local 201 Committee of the National Iron Workers

and Employers Training Program (hereinafter, "Training Program").

7. Construction Contractors Council, AGC Labor Divi

sion, Inc. (hereinafter, "CCC").

The party designated as No. 1 appeared as plaintiffs in

the proceedings below and on behalf of the class described in

No. 2 and are appellees here. The parties designated as Nos. 3

through 7 appeared as defendants below and are appellants here.

Party No. 1, on its own behalf and on behalf of the class

described in No. 2, takes the position that the District Court's

Trial Findings and Amended Order should be affirmed. Parties

Nos. 3 through 7 take the position that the District Court's

Trial Findings and Amended Order should be reversed.

The Associated General Contractors of America, Inc. has

been granted leave to file, and have filed, an amicus curiae

brief supporting the position taken by party No. 7.

3

These representations are made in order that the judges

of this Court, inter alia, may evaluate possible disqualification

or recusal.

Respectfully submitted,

Thomas W. White

WILMER, CUTLER & PICKERING

2445 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037

(202) 663-6000

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW........................................1

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE...... ••3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.............................................. 3

OVERVIEW AND STATEMENT OF FACTS................................... 3

A. The History of Discrimination Against Black

Workers in the Washington, D.C. Construction

Industry..................................................... * 3

B. The Suit by Black Rodmen....................................9

1. The Collective Bargaining Agreement................... 10

2. Discriminatory Barriers to Union

Membership........................................ 43

3. The District Court's Findings..........................13

ARGUMENT.................... 19

I. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ERR WHEN IT FOUND THAT

THE PLAINTIFFS' STATISTICAL EVIDENCE ESTABLISHED

A PRIMA FACIE CASE OF DISCRIMINATION...................... 21

II. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ABUSE ITS DISCRETION

IN CERTIFYING THE CLASSES......................... 24

III. THE DEFENDANTS' VIOLATION OF TITLE VII AND

SECTION 1981 OCCURRED WITHIN THE APPLICABLE

STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS..................................... 28

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY FOUND THE

INTERNATIONAL AND CCC LIABLE FOR THE DISCRIMINATORY

BARRIERS TO UNION MEMBERSHIP............................... 30

A. Under Applicable Case Law, The International

is Liable for Discriminatory Barriers to

Union Membership........................................3-

Page

B. The Court Below Properly Imposed Liability

on CCC..........’....................................... 3 3

V. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER PROVIDED THE PLAINTIFFS

WITH APPROPRIATE REMEDIES FOR PAST DISCRIMINATION........36

CONCLUSION........................................................39

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Pg.g.g

Abercrombie v, Bi-Lo. Inc., 21 FEP Cas 1252 (D.S.C. 1979) .... 25

Anderson v. Group Hospitalization, No. 85-601 slip. op.

(D.C. Cir. June 12 , 1987 ) ..................................... 23

Banks v. Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone, 802 F.2d 1416,

256 U.S. App. D.C. 22 (D.C. Cir. 1985 ) .................... 32,36

Bazemore v, Friday, 106 S. Ct. 3000 (1986) .............. 22,23,24

Byrd v. Local Union No. 24, International Brotherhood of

Electric Workers, 37 5 F. Supp. 54 5 (D. Md. 1974) ............ 34

Carbon Fuel Company v. United States Mine Workers, 444 U.S.

212 (1979) ..................................................... 32

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982) ......................... 15

Craik v. Minnesota State University 3d., 731 F.2d 465 (8th

Cir. 1984) ..................................................... 22

De La Fuente v. Stokely-Van Camp, Inc., 713 F.2a 225 (7th

Cir. 1983) ..................................................... 27

East Texas Motor Freight Systems, Inc, v. Rodriquez, 431

U.S. 395 (1977) ................................................ 25

Fink v. National Savinas & Trust Co., 772 F.2d 951, 249 U.S.

App. D.C. 33 (D.C. Cir. 198 5) .................................. 26

*General Building Contractors Association, Inc, v.

Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 375 ( 1982 ) ...................... 18,34,35

General Telephone Co. v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 147 (1982 ) .......... 25

^Goodman v. Lukens S~.eel Co., No. 85-1628 ; 85-210, slip op.

(U.S. June 24, 196.') .................................... 18,32,36

Griqas v. Duke Power Co. , 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ................. 15

*Cases or authorities chiefly relied upon are marked by asterisks

Griffin v. Carlin, 775 F.2d 1516 (11th Cir. 1985 ) ............. 25

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433 U.S. 299

(1977 ) ......................................................... 21

Howard v. International Molders & Allied Workers Union, 779

F .2d 1546 (11th Cir. 1986), cert, denied, 106 S. Ct. 2902

(1986) .......................................................... 31

Kaplan v. IATSE, 525 F.2d 1354 ( 9th Cir. 1975 ) ................ 31

Laffey v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 567 F.2d 429, 185 U.S.

Ad d . D.C. 322 (D.C. Cir 1976), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 1086

(1978), aff'd in part and remanded in part, 746 F.2d 4 241

U.S. App. D.C. 11 (D.C. Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 472

U.S. 1021 (1985) ............................................... 29

*Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers International Association

v, EEOC, 106 S.Ct. 3019 ( 1986) ............................ 37,38

Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d 979, 156

U.S. App. D.C. 69 (D.C. Cir. 1973), aff'd mem, 547 F.2d

706 , 178 U.S. App. D.C. 409 (D.C. Cir. 1977 ) ................ 34

McKenzie v. Sawyer, 684 F.2d 62, 221 U.S. App. D.C. 288

(D.C. Cir 1982 ) ............................................... 28

Milton v. Weinberger, 645 F.2d 1070, 207 U.S. Apo. D.C. 145

(D.C. Cir. 1981 ) ............................... 28,29

*Mvers v. Gilman Paper Corp., 544 F.2d 837 (5th Cir.)

modified on other grounds, 556 F.2d 758, cert. dismissed,

434 U.S. 801 (1977 ) .......................................... 31,33

Moten v. Bricklayers Masons and Plasterers International

Union, 543 F.2d 224, 177 U.S. App. D.C. 77 (D.C. Cir.

1976) ............................................................ 4

*Palmer y, Schultz, 815 F.2d 84 (D.C. Cir. 1987 ) ....... 22,23,24

Postow y. QBA Federal Savings & Loan Association, 627 F.2d

1370 , 201 U.S. App. D.C. 384 (D.C. Cir. 1980 ) ............... 26

^Reynolds v. Sheet Metal Workers, 498 F. Supp. 952 (D.D.C.

1980), aff'd, 702 F.2d 221, 226 U.S. App.'b.C. 242 (D.C.

Cir. 1981 ) ...................................... 7,8,16,21,22,25

Seqar v. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249, 238 U.S. App. D.C. 103 (D.C.

Cir. 1984), cert. den i ed, 471 U.S. 1115 (1985) ...........21,23

*Cases or authorities chiefly relied upon are marked by asterisks

iv

*Snehadeh v. Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Co., 59o F .2d

711, 193 U.S. App. D.C. 326 (D.C. Cir. 1978 ) ............. 28,29

Teamsters v. United States, 41 U.S. 324 (1977) ............. 18,22

Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257, 219 U.S. app. D.C. 393

(D.C. Cir. 1982), aff'd sub, nom. Thompson v. Kennichell,

797 F .2d 1015, 254 U.S. App. D.C. 348 (D.C. Cir. 1986),

cert, denied, 107 S. Ct. 1347 ( 1987) ......................... 29

United States v. United Association of Journeymen and

Apprent ices, 364 F. Supp. 808 (D. N.J. 1973 ) ................ 34

Valentino v. U. S. Postal Service, 16 FEP Cas 242 (D.D.C.

1977) 25

Valentino v. U. S. Postal Services, 674 F.2d 56 (D.C. Cir.

1982) 23

Wheeler v. American Home Products Corp., 19 FEP Cas 143

(N.D. Ga. 1979) ............................... ................ 31

STATUTES, RULES AND REGULATIONS

Fed. R. Civ. Pro. 23 ..............................................2

41 CFR 60-5 (1974) .................................................4

41 CFR 60-5.10 (1974) .................. ......... ................ 4

42 U.S.C. § 1981 (1982) ...................................... passim

42 U.S.C. §S 2000e, et seg_.................................... passim

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Prosser and Keeton on Torts, 501-502, 505-506 (5th ed. 1984)

..............................................................33,35

Payton, Redressing the Exclusion of and Discrimination

Against Black Workers in the Skilled Construction Trades;

the Approach of the Washington Lawyers' Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law, yearbook of Construction Articles,

*Cases or authorities chiefly relied upon are marked by asterisks

v

69, 88-90 (1984 ) ......................................... 6,7,8,9

*Schlei & Grossman, Employment Discrimination Lav, 1368 (2d

ed. 1983 ) ................................................ 23,25,28

*Cases or authorities chiefly relied upon are marked by asterisks

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

Nos. 85-6217, 86-5027, 86-5028

86-5275, 86-5276, 86-5277

(consolidated)

COMPLEX

JESSIE BERGER, et al.,

Appellees,v .

IRON WORKERS REINFORCED RODMEN, LOCAL 201, et al.,

Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

Civil Action No. 75-1743

Judge John Garrett Penn

BRIEF OF NAACP

AMICUS CURIAE,

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES BERGER, et al.

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

After a 23 day t

extensive factual findings

violated 42 U.S.C. § 1981

of the Civil Rights Act of

( 198 2) et, seq. ("Title VII

rial, the District Court entered

and legal conclusions that defendants

("Section 1981") (1982) and Title VII

1964, 42 U.S.C. SS 2000e, et seq.

") by erecting barriers to the entry of

I

blacks into the rodmen's union for the Washington D.C. area.

The ultimate issue presented in this case is whether the District

Court's decision was clearly erroneous or contrary to law. This

brief will address five principal issues:

(1) Whether the District Court correctly

relied on the plaintiff's unrebutted statis

tical evidence when finding the defendants

liable for racial discrimination under

Title VII and Section 1981.

(2) Whether, under the standards set forth in

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23, the District Court

properly certified classes of black rodmen

who had been excluded from, and/or discour

aged from, seeking union membership;

(3) Whether the District Court correctly

found that this suit was brought within the

applicable statute of limitations;

(4) Whether the District Court correctly

found the International Association of

Bridge, Structural and Ornamental Iron

Workers ("International"), the Construction

Contractor's Council ("CCC"), and Iron

Workers Reinforced Rodmen Local 201 ("Local

201") liable for the discriminatory practices

of the Apprentice Committee and Training Pro

gram; and

(5) Whether the District Court's remedial

order was an appropriate exercise of its

broad discretion to formulate remedies in

discrimination cases.!/

1/ This case has not previously been before this Court.

Counsel is unaware of any related case pending in this Court or

any other court.

2

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The interest of Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc. is set forth in its Motion For Leave To

File Brief Amicus Curiae, which is attached to this brief.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Amicus adopts the Statement of The Case contained in

the Brief of the Appellees.

OVERVIEW AND STATEMENT OF FACTS

This case presents a clear cut example of discrimina

tion against black workers in the construction industry. It

involves well settled principles of law applied to straightfor

ward factual circumstances, and is but one of a series of cases

brought by black workers to end the pervasive pattern of racial

discrimination in the construction industry in the Washington

area. The decision here is in line with the result in these

other cases.

A. The History of Discrimination Against

Black Workers in the Washington D.C.

Construction Industry_________________

The construction industry in Washington, D.C., has a

long history of discrimination. As late as the 1960s, black

3

workers were forced to work in segregated unions and, as a

result, were relegated to jobs in the residential construction

industry. See, e.a., Moten v. Bricklayers Masons and Plasters

International Union, 543 F.2d 224, 226 (D.C. Cir. 1976). Few, if

any, blacks were employed at larger commercial construction proj

ects. In the mid-1960's , blacks demanded that they be provided

with equal access to these larger, better-paying projects. In

response, on June 1, 1970, the Department of Labor issued the

Washington P l a n . I n adopting the Plan, the Department j.ound

that:

[I ]t is apparent that minority workers . . .

have been prevented from fully participating

in the construction trades. This exclusion

is due in great measure to the special nature

of the employment practices in the construc

tion industry where contractors and subcon

tractors rely on construction craft unionsas

their prime or sole labor source. Collective

bargaining agreements and/or established cus

tom between construction contractors and sub

contractors and unions frequently provide

for, or result in, exclusive hiring

halls . . . . As a result of these hiring_

arrangements, referral by the union is a vir

tual necessity for obtaining employment in

the union construction projects. Minorities

often have not gained admittance into member

ship of certain unions and apprenticeship

programs, and, thus, have not been referred

for employment. 41 C.F.R. § 60-5.10 (1974).

To remedy the persistent exclusion of black workers

from commercial construction projects, the Washington Plan sec

2/ 41 C.F.R. 60-5 ( 1974 ) .

4

forth target goals for minority participation at federal con

struction sites. It required contractors to employ certain num

bers of black workers in each of the construction trades. These

hiring goals were set forth in terms of ranges. For instance,

for 1973-74, a year before the filing of this lawsuit, the Plan

set the following targets for the employment of minorities at

federal construction sites: 35-43 percent of the ironworkers;

35-42 percent of the painters and paperhangers; 25-31 percent of

the sheet metal workers; 34-40 percent of the lathers; 24-30 per

cent of the boilermakers; and 28-34 percent of the electricians.

As a means of ending pervasive discrimination in the

construction trade, the Washington Plan suffered from two

deficiencies. First, it did not apply to non-federal work sites,

Second, despite the Plan's recognition of the discriminatory

effect of the union hiring hall system, it did not require the

lowering of barriers that had prevented black workers from

entering into apprenticeship programs and obtaining union member-

3 /ship.— Instead, it placed the onus on contractors to hire

minority workers. Thus, while the Plan acknowledged the history

3/ Appellant International states that the Washington Plan

exempted rodmen from its hiring goals because a sufficient per

centage (39.5 percent) of blacks were employed in this trade.

(International's Brief, at 19.) This argument fails to note that

this case involves discrimination in the admittance of blacks to

union membership, not discrimination in the hiring of blacks by

contractors. Indeed, the substantially larger number of blacks

among the non-union rodmen indicates that discrimination has

occurred with respect to the granting of union membership.

5

of discrimination in the construction trade and enabled blacks to

obtain employment at federal construction projects, it did not

attack the root cause of the continued exclusion of blacks from

better, higher-paying jobs in the industry: exclusive union hir

ing halls.

The problem of the union hiring hall system was

addressed by a number of class action suits, including this case,

which were brought by black construction workers in the mid-

1970s. These suits charged that discriminatory barriers to union

membership, in combination with exclusive union hiring halls

established pursuant to collective bargaining agreements, ren

dered the unions and contractor associations jointly liable for

violations of Section 1981 and Title VII. In all the other

cases, the black workers obtained most, if not all, the relief

they sought. For instance, by bringing class action lawsuits,

black bricklayers, electricians, carpenters, and sheet metal

workers were all able to remove arbitrary barriers to their entry

into white-dominated unions and, thereby, to obtain access for

4 /the first time to higher-paying construction jobs.-

4/ See Payton, Redressing the Exclusion of and

Discrimination Against Black Workers in the Skilled Construction

Trades: The Approach of the Washington Lawyers' Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law," 4 Yearbook of Construction Articles,

1397, 1416-1418 (1985) (hereinafter cited as Discrimination

Against Black Workers).

6

In one of those cases, which presented facts very simi

lar to those presented here, black sheet metal workers charged

several defendants, including the local and international unions,

a contractors' organization, and joint apprenticeship committee,

5/with discriminating against blacks in union membership.— During

the course of that suit, the black workers sought a preliminary

injunction to prevent the use of discriminatory criteria to

select new apprentices. In particular, the black workers chal

lenged three aspects of the program's selection process: (1) high

school diploma requirement; (2) an arrest record inquiry; and

(3) subjective personal interview. Reynolds v. Sheet Metal

Workers, Local 102, 498 F. Supp. 952, 960-61 (D.D.C. 1980),

aff’d , 702 F.2d 221 (D.C. Cir. 1981). They claimed these selec

tion criteria were not job-related and served as knock-out provi

sions that had a disproportionate impact on black applicants to

the program. Id.

Even though the percentage of blacks in the apprentice

ship program (26 percent) was identical to the percentage of

blacks in the population as a whole, the District Court ruled

that, based on statistical evidence offered by the plaintiffs

showing that blacks constituted approximately 40-45 percent of

the relevant labor pool for sheet metal workers, the plaintiffs

had a good chance of winning on the merits with respect to the

5/ See id., at 1426-1429.

7

issue of whether the selection criteria for the apprenticeship

orograra violated Title VII and Section 1981. Id.* r at 970. ihe

District Court, therefore, granted the preliminary injunction,

id., at 974, and this Court affirmed. Reynolds v. Sheet. Me t_al

Workers, Local 102, 702 F. 2d 221 (D.C. Cir. 1981).

Subsequently, the parties settled the underlying class

action suit by entering into a consent decree. In that decree,

the union agreed that apprentice vacancies were to be advertised

in a manner likely to reach eligible blacks and that blacks would

constitute at least 42 percent of those accepted into the appren

ticeship program. Discrimination against blacks during the

apprenticeship program was addressed by a provision that required

at least 42 percent of the program's graduates to be black.

Finally, in response to the union's discrimination in the direct

admission of journeymen, the sheet metal union agreed that at

least 42 percent of the individuals admitted, who did not go

through the apprenticeship program, should be black.

Other settlements entered into between black workers

and unions contained provisions similar to those included in the

sheet metal workers settlement. For instance, when b±ack workers

challenged the selection criteria for the electricians union's

apprenticeship program, they were able to reach a settlement that

6/ Discrimination Against Black Workers, at 142/ 1428.

8

not only removed discriminatory selection criteria like those

involved in Reynolds, but also established goals for the partici

pation of blacks in the union.— ̂ A similar settlement was also

reached between a class of black workers and the carpenters'

8/union.-

The present case therefore must be seen as simply

another example of black construction workers seeking to end a

long history of discrimination by challenging barriers to member

ship in a construction union. As shown below, the District Court

found the same type of discrimination here as was found in the

other cases and adopted analogous forms of relief to remedy that

discr imi nat ion.

B . The Suit by Black Hodmen

Six black rodmen brought this suit under Section 1981

and Title VII on October 21, 1975. They sued on their own behalf

and on behalf of a class of similarly situated plaintiffs. In

particular, the plaintiffs charged that the defendants violated

the law by: (1) denying blacks equal employment opportunities in

the rodmen trade; (2) preventing blacks from obtaining membership

in the rodmen union; and (3) restricting black participation in

the Apprenticeship Program for Hodmen's Local 201 on the basis of

7/ Id. at 1422-1424.

8/ Id. at 1424-26.

9

race. (Findings, If 7.) The plaintiffs sought injunctive relief,

9 /back pay and attorney's fees.— (Findings, Iflf 1 and 7.)

1. The Collective Bargaining Agreement

The rodmen trade involves the handling and placement of

the steel rods used to reinforce concrete and other building

materials. (Findings, 1! 26.) In Washington, D.C., a rodman

obtains work by referrals from the Local 201 union hall in accor

dance with the provisions of a collective bargaining agreement

entered into between the union and the contractor's association

(CCC). As the District Court found, Local 201 acts as an

"employment agency" for contractors who need rodmen. (Findings,

If 46. )

The collective bargaining agreement established a pref

erential system for the hiring of rodmen. This preference for

union members was provided by giving first choice as to jobs and

overtime to class A or B journeymen workers. To obtain Class A

status, a worker must be a member of Local 201. Class B workers

are "travelling members" of associated rodmens' unions located in

other geographical areas of this country. Non-union workers were

placed in a class D ("permit workers").— ̂ (Findings, 48-49.)

9/ In March of 1978, an amended complaint was filed adding

two additional plaintiffs.

10/ Although the collective bargaining agreement refers to

Class C worker, as a practical matter, this classification has

never been used. (Findings, 52.)

10

These permit workers were always the last to be hired and the

first to be fired. Thus, under the collective bargaining agree

ment, union membership constituted an economically valuable sta

tus. (Findings, 1HI 57, 58, 59 and 109.)

Local 201 has been historically a "white's only" union

For instance, in 1967, only four of the union's more than two

hundred active members were black. (Findings, 11 63.) By 1971,

only six percent of the union's active membership was black.

(Findings, 11 64.) During 1970 to 1975, however, blacks always

constituted between 44 to 60 percent of the permit workers.

Clearly, at all relevant times prior to the filing of this law

suit, a disproportionate number of blacks were forced to work in

the inferior status of permit worker, and were thus denied the

security and higher pay provided their white counterparts that

were members of- the union.

2. Discriminatory Barriers to Union Membership

Despite the large number of blacks seeking employment

in the rodman trade during the late 1960s and early 1970s, Local

201 remained white by erecting a series of barriers to black mem

bership. The nature of the discriminatory barriers to union mem

bership differed depending on the time period involved.

Before February 1, 1971, the right to take the journey

man examination, which was and is a prerequisite to union

membership, could be obtained in only two ways. First, an appli

cant between the ages of 18 and 30 who had a high school diploma

could complete the apprenticeship program. Second, a rodman

could take the journeyman examination by amassing an unspecified

amount of experience and obtaining the discretionary approval of

the union's executive committee. (Findings, It 34.)

From February 1, 1971 to June 1971, there occurred what

has been called the "open period." During this four-month

period, although the apprenticeship program remained in place,

any rodman with two years experience could take the journeyman

exam. (Findings, 11 34.) Blacks, however, failed the exam at

twice the rate of whites. (Findings, It 76.)

After June 1971, the Union imposed new barriers to tak

ing the exam. Workers between 18 and 30 years old with a high

school diploma could obtain union membership by successfully

completing the apprenticeship program. (Findings, U 37.)

Workers over thirty years of age (with or without a high school

diploma) were required to take a two-year training course no mat

ter how long they had worked as a rodman. (Findings, II 42.) The

requirement that older permit workers seeking union membership

participate in the two year training program resulted in the

absurd situation that some rodmen, who worked as foremen,

subforeman or supervisor, were required to attend classes on how

to do the very jobs in which they were supervising others.

(Findings, Hit 13, 14 and 17.)

12

3. The District Court's Findings

Barriers to the Examination. The trial court found

that at all relevant times prior to the filing of this lawsuit,

the barriers to taking the journeyman exam excluded a dispropor

tionate number of blacks from obtaining union membership. (Find

ings, 11 82.) In reaching this conclusion, the trial court

accepted the expert testimony of plaintiffs' expert witness with

respect to the number of blacks that would have been "likely

examinees" absent these barriers.

The Court determined that the pool of "li

examinees" included rodmen with at least two years

(Findings, HH 67-70.) The court then found that, p

February 1, 1971, 55.8 percent of the eligible whit

examined, while only 15.9 percent of the qualified

allowed to take the membership exam. (Findings, U

even during the "open period," when any rodman with

experience was eligible to take the exam, blacks fa

at a rate twice the rate of whites. Specifically,

white examinees passed, while only 35.3 percent of

passed the exam. (Findings, U 76.)

kely

experience.

r ior to

es were

blacks were

72. ) Further

two years

i led the exam

70.6 percent

the blacks

The trial court bifurcated its findings with respect to

the period from June 13, 1971 to October 21, 1975. From June 13,

1971 to October 21, 1972, approximately 33 percent of the quali

fied whites, but only 9 percent of blacks were selected to take

13

the journeyman examination. (Findings, U 79.) From October 22,

1972 to October 21, 1975 (the date

percent of the whites, but only 17

applied were permitted to take the

( Findings , 11 80 . )

this lawsuit was filed), 33

percent of the blacks that

journeyman examination.

The District Court found that, for each of these time

periods, there was a very small probability that the large dis

parity in the percentage of black and white rodmen selected to

take the exam was due to chance. For the period prior to

February 1, 1971, the District Court found that the probabilities

were one in a million that non-discriminatory factors led to the

different rates in the selection of whites and blacks to take the

exam. (Findings, II 73.) This translates into a standard devia

tion of 5.62, a figure well in excess of the level of statistical

significance generally required in disparate impact cases.

(Findings, 1111 73-74 .)

With respect to the open period (February to June

1971), the probability that chance caused the different pass

rates was found to be slightly less than one in forty, or 2.25

standard deviations. (Findings, H 77.) Finally, for the period

from June 13, 1971 to October 21, 1975, the Court found that the

difference between the percentage of qualified blacks and whites

selected to take the exam ranged from 2.96 to 3.4 standard devia

tions. (Findings, UU 79-80.)

14

Thus, the trial court found that the plaintiffs had

established their prima facie case that, at all times during the

four-and-one-half years prior to the filing of this suit, the

union's criteria for selecting individuals to take the journeyman

exam, and the exam itself, violated Title VII owing to the dis

proportionate impact on black applicants for union membership.— '

(Findings, U1f 81 and 82.) This pr ima facie case was not rebutted

by the defendant. As the trial court found, "no examination

given by Local 201 has even been shown to be a valid predictor of

job performance." (Findings, 1! 31.)

The Apprenticeship Program. The trial court also ruled

that the selection criteria for the Apprenticeship Program were

discriminatory. In this regard, on the basis of a "new entrant"

1 0 /statistical model developed by the plaintiffs' expert,— the

11/ Under Title VII, plaintiffs are entitled to relief when

they demonstrate that selection criteria, although facially neu

tral, have a "disproportionate impact" on minority workers. See,

e .q ., Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 447 (1982), citing

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.. 401 U.S. 424, 431 (1971) (Congress

enacted Title VII so as to require "the removal of artificial,

abitrary, and unnecessary barriers" to employment and profes

sional advancement that have been historically encountered by

women and blacks).

12/ Plainti

tistical model be

cants to the appr

tistical approach

conclusion with r

for the Apprentic

stituted 42.2 per

Fact, 11 93 . )

ffs' expert was required t

cause the union did not ke

enticeship program. He al

, the "commuter model", to

espect to the number of bl

eship Program. This model

cent of the relevant labor

o construct this sta-

ep records of appli-

so used another sta-

corroborate his

acks likely to apply

showed the black con-

pool. (Findings of

15

District Court determined that the relevant labor pool for appli

cants to the Apprenticeship Program was 45.1 percent black, from

1970 to 1979. (Findings, H 93.) Blacks, however, only consti

tuted 25.1 percent of the apprentices during this same period.

(Findings, II 93.) The Court found, therefore, that the differ

ence between the expected rates of black participation and the

actual rate of selection to the Apprenticeship Program ranged

from 6.27 to 7.28 standard deviations from the norm.

The defendants did not rebut this prima facie case.

The Court found that a high school diploma is not necessary in

order to perform the work of a journeyman rodman. (Findings,

11 95.) It also ruled that the defendant had failed to demon

strate that any error in the plaintiff's statistical method

caused the "new entrant” approach not to be statistically valid.

(Findings, II 96.) Just as in Reynolds v. Sheet Metal Workers

Local 102, 498 F. Supp. at 970, the Court concluded that the high

school diploma requirement was not job-related and had a dispro

portionate impact on blacks.

The Training Program. Finally, the Court found that

the Training Program served as "an illegal detour" to union mem

bership. (Findings, H 103.) The Court stated, "[i]n short, the

defendants have created two racially distinct 'tracts' leading to

the journeyman examination: a predominately white apprenticeship

'tract' and a predominately black trainee 'tract.'" The trainee

- 16 -

"tract" was found to be a signifcantly less effective means of

qualifying to take the examination. The Court concluded: "the

bifurcation of the pool of experienced workers according to age,

and the creation of two parallel 'preexamination' [sic] programs,

has prima facie discriminated against black rodmen, and has

unlawfully denied them journeyman membership in the union and

placement in the top referral group under the collective bargain

ing agreement." (Findings, U 108.)

Liability of the International and CCC. The District

Court ruled that the Local 201, the Apprenticeship Committee, and

the Training Program had violated Title VII by establishing

selection criteria that, although facially neutral, had a dispro

portionate impact on blacks. The Court found the International

liable on the ground that it had the right to control the Local

under its constitution and had in fact exercised significant con

trol over Local's actions with respect to the collective bargain

ing agreement that established the discriminatory referral sys

tem, as well as the administration of the Apprenticeship Program,

the Training Programs, and the Union exam. (Findings, HH 121,

130, 133, and 134.) With regard to the liability of CCC, the

Court ruled that CCC was liable because it appointed representa

tives to serve on the Apprenticeship Committee (Findings, U 141)

and because CCC: "(1) was aware that the referral clause had a

discriminatory impact; (2) took notice of such discrimination in

its collective bargaining; (3) ultimately agreed to retention of

17

the clause; and (4) thus, knowingly participated in continuation

of racial discrimination." (Findings, U 144.)

Discriminatory Treatment. Besides finding that all the

defendants had participated in practices that had a

"discriminatory impact" on the plaintiffs, the District Court

also ruled that all the defendants had subjected the plaintiffs

to "disparate treatment." (Conclusions of Law, If 17.) The Court

held that the statistical disparities -- in and of themselves --

established both the fact of disparate treatment and racial ani

mus. (Conclusions of Law, 11 17.) The Court found further sup

port for its finding of racial animus in specific instances of

discrimination against the named plaintiffs, such as:

(1) refusal of admittance to the Apprenticeship Program and

Training Program; (2) discrimination in job referrals, lay-offs

and overtime; and (3) acts of retaliation for bringing the law

suit in question. (Conclusions of Law, HH 19-21.) Thus, it

found that the defendants had violated both Title VII and Section

1981.— 7

13/ This finding that the defendants' actions were

motivated by racial animus satisfies the requirement under

Section 1981, and in "disparate treatment' cases under Title VII,

that a plaintiff prove "purposeful discrimination. See General

Building Contractors Association v. Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 375,

391 (1982) (Section 1981 requires proof of "purposeful discrimi

nation"); Goodman v. Lucas Steel Co., No. 85-1628; 85-210, slip

op. at 7 (June 19, 1987) (although no proof for discriminatory

intent is necessary under Title VII when "disparate impart" is

alleged, intentional racial discrimination is an element of the

offense in "disparate treatment" cases). See also Teamsters v.

United States. 431 U.S. 324, 335 n.15 (1977).

- 18

Remedial Order. On the basis of these findings, the

Court issued an order which (1) enjoined further discrimination

by the defendants; (2) directed that the named plaintiffs who had

been excluded from union membership be admitted forthwith;

(3) established procedures for testing and admission of class

members to the Union; and (4) prescribed job referral procedures

and statistical reporting requirements regarding referrals.

(District Court's Amended Order, HH I, II and III.)

ARGUMENT

The District Court's findings that all the defendants

jointly engaged in a pattern of behavior that discriminated

against black rodmen seeking entry into the rodmen's union was

based on substantial evidence in the record and a straightforward

application of well-settled legal principles. The Appellants'

briefs in this case basically seek to relitigate the District

Court's factual findings. As the Appellees' Brief shows, the

detailed findings of the Court below are not clearly erroneous,

and, indeed, are amply supported by the evidence in the record.

Amicus does not propose to repeat that showing here. Instead,

the purpose of this Brief is to emphasize that, as to the princi

pal claims of error advanced by appellant, this case falls

squarely within the mainstream of applicable precedents under

Title VII and Section 1981. Affirmance does not require this

Court to address novel questions or extend existing law.

19

Moreover, as shown above, the District Court's findings

are consistent with the conclusions reached by the Department of

Labor and courts in this Circuit when addressing discrimination

claims by blacks against trade unions in the Washington, D.C.

construction industry. The District Court's remedial order is

also consistent with the remedies provided to black workers in

these analogous situations. Indeed, the appropriateness of the

remedies provided is highlighted by the fact that its terms are

similar to the provisions of the consent decrees agreed to by the

sheet metal workers' union, the electricians' union and the car

penters' unions. See pages 5-7, supra.

Every other construction union in the Washington, D.C.

area has voluntarily agreed to open its doors to blacks on terms

similar to those imposed by the District Court in this case.

Nevertheless, the rodmens' union still refuses to admit the

discriminatory nature of their past practices and make amends.

Thus, twelve years after the filing of this suit, black rodmen

are still unsure whether they will receive relief from the dis

crimination they suffered. The time has come for black rodmen to

be granted equal access to union membership. There is no reason

to overturn the District Court's careful application of the rele

vant law to the discriminatory practices engaged in by all the

defendants.

20

I. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ERR WHEN IT FOUND THAT

THE PLAINTIFFS' STATISTICAL EVIDENCE ESTABLISHED

A PRIMA FACIE CASE OF DISCRIMINATION._____________

All the appellants argue that the District Court erred

in accepting the plaintiffs' statistical evidence. (Local's

Brief, at 61-87; International's Brief, at 33-35.) In effect,

appellants ask this Court to re-evaluate de novo the evidence

presented to the District Court. This approach ignores recent

precendents that require an appellate court to apply the clearly

erroneous standard of review when determining the appropriateness

of the admission of statistical evidence into the evidence.

It is well-established that when an action is brought

under Title VII or Section 1981, a plaintiff may make a prima

facie case of racial discrimination by presenting statistical

evidence showing that facially neutral selection criteria never

theless have a disparate impact on minority groups.— ̂ Indeed,

the Supreme Court has consistently upheld the appropriateness of

14/ See, e .q ., Hazelwood School District v. United States,

433 U .S . 299, 307-308 (1977) ("Where gross statis

disparities can be shown, they alone in a proper

pr ima facie proof of a pattern or practice of dis

Seqar v. Smith. 738 F.2d 1249, 1278-79 (D.C. Cir.

denied, 471 U.S. 1115 (1985) ("[wjhen a plaintiff

focuses on the appropriate labor pool and generat

[a disparity] at a statistically significant leve

evidence alone will be sufficent to support an in

crimination); Reynolds v. Sheet Metal Workers Loc

221, 225 (D.C. Cir. 1981) (plaintiff's statistics

mitted them to "establish a pr ima facie case that

tice selection procedures had [a] racially dispar

t ical

case constitute

crimination");

1984), cert.

's methodology

es evidence of

1," this

ference of dis-

al 102, 702 F .2d

1 evidence per-

. . . appren-

ate impact).

21

using of statistical evidence to prove discrimination in Title

VII cases. See, e.q ., Bazemore v. Friday, 106 S. Ct. 3000, 3009

(1986); Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 339 (1977). In

order to establish a prima facie case of discrimination using

statistical evidence, a plaintiff must show a disparity in selec

tion rate of at least 1.96 standard deviations. Palmer v.

Schultz, 815 F .2d 84, 99 (D.C. Cir. 1987). However, if the dis

parity falls within 1.65 and 1.96 standard deviations, the trial

courts may consider it in conjunction with other evidence to

determine whether unlawful discrimination occurred. Id. at 97

n.10, citing Craik v. Minnesota State University Board., 731 F.2d

465, 476 n .13 (8th Cir. 1984).

The District Court's decision in this case comports

completely with these well-established principles. Plaintiffs'

introduced valid and probative statistical evidence showing that,

at all relevant times, the disparity between the selection of

eligible blacks and whites exceeded a standard deviation of 2.25

-- a figure well in excess of Palmer's 1.96 figure. Indeed, the

plaintiffs' statistical findings are almost identical to those

upheld by this Court in Reynolds v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local

102, 702 F.2d at 225. The District Court, moreover, also relied

on specific instances of discriminatory treatment to bolster its

finding of purposeful racial discrimination by the defendants.

There is no doubt that District Court correctly found that the

plainiffs had established their pr ima facie case of

discr imination.

2 2

e case,Once a plaintiff has established a prima faci

the burden then shifts to the defendant to rebut the plaintiffs

statistical evidence. The defendant might rebut the statistical

evidence by demonstrating that the statistical disparity nad a

legitimate, non-discriminatory explanation. Palmer v. Shultz,

815 F.2d 84, 91 n.6 (D.C. Cir. 1987), citing Segar, 738 F.2d at

j_27g Alternatively, the derendant might rebut the piain

tiff's statistical case by demonstrating analytical flaws and/or

errors or omissions in the data. Anderson v.— Group

Hospitalization. Inc., No. 85-6107, slip op. at 4 (D.C. Cir.,

June 12, 1987), quoting Schlei & Grossman, Employment

Discrimination Law 1368 (2d Ed. 1983).

The District Court's determination of whether the

defendant has adequately rebutted the plaintiff's statistical

case is subject to the clearly erroneous standard of review.

Palmer v. Schultz, 815 F.2d, at 100, citing Bazempre_y . Frida_y,

106 S. Ct. at 3009 (1986). Thus, the defendant does not carry

its burden simply by pointing out "imperfections in the data on

which the plaintiffs' analysis depends, or the omission of possi

ble explanatory factors from the plaintiffs' statistical study.

1 5/ The District Court's findings that school diploma

"requirement, the Training Program, and the^union exam did not

have a legitimate non-discriminatory function are undoubtedly

correct. Several of the named plaintiffs, who had put m over

10 thousand hours on the job, served as supervisors without

having any of these supposed qualifications. (Findings, Ini

and 17.)

23

Palmer v. Schultz, 815 F.2d, at 100. As the Supreme Court

stated: "While the omission of variables from a regression analy

sis may render the analysis less probative than it otherwise

might be, . . . as long as the court may fairly conclude that, in

light of all the evidence, that it is more likely than not that

impermissable discrimination exists, the plaintiff is entitled to

prevail." Brazemore v. Friday, 106 S. Ct., at 3009. Here,

appellants did not attempt to show any nondiscriminatory

explanations for the disparity. Appellants' quarrels with plain

tiffs' statistical methodology do not satisfy the clearly

erroneous standard. The lower court's findings must be upheld.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ABUSE ITS DISCRETION

IN CERTIFYING THE CLASSES________________________

Appellants argue that the District Court improperly

certified the named plaintiffs as representatives of the class of

black rodmen that had been excluded from membership in the union

or discouraged from seeking membership because of their race.

For the most part, Local 201 seeks to challenge the District

Court's class certification on the ground that it is not sup

ported by the record. (Local's Brief, at 39-58.) At bottom,

this argument is based on the premise that the named plaintiffs

have not suffered injuries that are typical of the class. This

contention is without support in the case law or the record.

In East Texas Motor Freight Systems, Inc, v. Rodriquez,

431 U.S. 395, 405-405 (1977), the Supreme Court stated that,

"suits alleging racial or ethnic discrimination are often by

their very nature class suits, involving classwide wrongs." In

determining the appropriateness of a class suit under Title VII

and/or Section 1981, the courts have focused on whether the class

suit challenges "rules or policies of general application" or

"individual employment decisions."— 7 Where, as here, the prac

tices under attack involve a generalized testing requirement and

training programs, there is simply no doubt that class treatment

is appropriate. See Schlei and Grossman, Employment

Discrimination Law, 1232, n.34 (1983) (Rodriguez court was refer

ring to adverse impact cases attacking general practices, such as

tests). Thus, certification of a class in cases, like the one at

bar, where a union's generally applied selection criteria are

16/ In many cases, courts have approved class actions when

workers challenged discriminatory policies and general practices

as violations of Title VII and Section 1981. See, e■a ,, Griff in

v . Carl in, 755 F.2d 1516 (11th Cir. 1985); Reynolds v. Sheet

Metal Workers, Local 102, 702 F.2d 221 (D.C. Cir. 1981). Cf.

Abercrombie v. Bi-Lo, Inc., 21 FEP Cas 1252, 1262-63 (D.S.C.

1979) (class action is appropriate when it challenges general

policies, rather than individual employment decisions); Valentino

v. United States^Postal Service, 16 FEP Cas 242, 244 (D.D.C.

1977) (if plaintiff was attacking Postal Service's employment

practices, class action would be appropriate). See also General

Telephone Co. v. Falcon. 457 U.S. 147, 159 n.15 (1982) ("Signifi

cant proof that an employer operated under a general policy of

discrimination. . . could justify a class of both applicants and

employees if the discrimination manifested itself in hiring and

promotion practices in the same general fashion") (emphasis

added).

25

being challenged by injured black workers falls squarely within

the ambit of well-established case law.

The District Court has broad discretion in determining

whether a suit should proceed as a class action. The review of

the appellate court is limited to determining whether the Dis

trict Court abused that discretion. Fink v. National Savings &

Trust Co., 772 F .2d 951, 960 (D.C. Cir. 1985). The issue is sim

ply whether the facts in the record provide some support for the

district court's conclusion. See Postow v. OBA Federal Savings &

Loan Association, 627 F.2d 1370, 1380 n.24 (D.C. Cir. 1980).

Here, the record contains ample support for the District Court's

class certification.

The appellants' principal argument that the named

plaintiffs' claims of discrimination are not typical of the class

utterly fails to recognize the character of the District Court's

ruling. The Court found that the Apprenticeship Program, the

Training Program, and the exam requirement discriminated against

actual and potential black applicants by erecting barriers to

their obtaining union membership. In some instances, the Court

found that these barriers served to exclude blacks. In others,

it concluded that these practices violate the law by discouraging

blacks from obtaining union membership.

All the named plaintiffs were either excluded or dis

couraged from obtaining union membership by one or more of these

26

three discriminatory barriers. First, named plaintiffs Bellamy,

Lewis, Kirkland and Tucker all worked out of Local 201 when they

were under 31. Since all these plaintiffs lacked high school

diplomas, each of them was excluded for a period of time from

obtaining union membership by the Apprenticeship Program's high

school diploma requirement. (Findings, HU 14, 15, 16, and 17.)

And plaintiff Tucker has never been admitted to the Training Pro

gram and, therefore, this barrier actually excluded him from

union membership. (Findings, U 16.) Second, plaintiffs Kirkland

and Bellamy, who failed the discriminatory membership exam during

the open period and had to take the Training Program to have a

second chance at union membership, have claims typical of those

blacks who were excluded and/or delayed from obtaining union mem

bership by the exam requirement. (Findings, UU 14 and 17.)

Third, plaintiffs Berger, Jackson, Kirkland and Bellamy, even

though they had extensive work experience, were discouraged from

obtaining union membership by the delays associated with the

Training program. (Findings, 1111 12,13, 14 and 17.) Finally,

plaintiffs Simmons and McMilliam were, in fact, discouraged from

entering the Union's Apprenticeship Program. (Findings, UU 18

and 19.)

t ion

these

In light of these facts,

that the trial court correctly

named plaintiffs were typical

there can be no serious ques-

found that the claims of

of the class members.— ̂ The

12/ See e ■q ■, De la Fuente v. Stokely-Van Camp, Inc., 713

S • 2 d 225, 232 ( /1 h Cir. 1985) (similarity between, lecal theories

controls even in the face of different facts).

27

District Court did not abuse its discretion when certifying the

plaintiff classes.

III. THE DEFENDANTS' VIOLATION OF TITLE VII AND

SECTION 1981 OCCURRED WITHIN THE APPLICABLE

STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS._______________________

Local 201 asserts that the District Court failed to

apply the appropriate statutes of limitation under Title VII and

Section 1981 when it permitted the named plaintiffs to bring this

suit. (Local's Brief, at 51-54.) The Local's argument ignores

the District Court's factual findings, as well as established

precedent in this Circuit, which unquestionably places this case

in" the class of true "continuing violation" cases.

A "continuing violation" is "a series of related acts,

one or more of which falls within the limitation period, or the

maintenance of a discriminatory system both before and during the

statutory period." Milton v. Weinberger, 645 F.2d 1070, 1075

(D.C. Cir. 1981), quoting Schlei & Grossman, Employment

Discrimination Law 232 [Supp. 1979]; Valantino v. United States

Postal Service, 674 F.2d 56, 65 (D.C. Cir. 1982). This Court has

traditionally applied the continuing violation principle to

cases, like the one at bar, where established policies and prac

tices have discriminated against a certain class of workers on an

ongoing basis. McKenzie v. Sawyer, 684 F.2d 62, 72-73 (D.C. Cir.

1982); Shehadeh v. Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Co., 595 F.2d

711, 724-25 (D.C. Cir. 1978) .

28

This Court has also held that, in cases involving

established practices and policies that have a discriminatory

impact, "discrimination is not limited to the isolated events."

Laffev v. Northwestern Airlines, Inc., 567 F.2d 429, 473 (D.C.

Cir. 1976), cert. denied., 434 U.S. 1086 (1978). In these cases,

therefore, the ongoing program of discrimination, rather than any

of its particular manifestations, is the focus of the court's

inquiry. When determining the existence of discrimination in vio

lation of Title VII and Section 1981. Shehadeh v. Chesapeake and

Potomac Telephone Co., 595 F.2d at 724-25. Thus, in this Cir

cuit, when a plaintiff relies upon a "continuing violation" the

ory, suit may be brought on acts occurring before the limitations

period when the underlying discriminatory policy remains in

effect during the actionable period. See Thompson v. Sawyer, 678

F .2d 257, 289 (D.C. Cir. 1982), aff'd sub nom,, Thompson v.

Kennickell, 797 F.2d 1015 (D.C. Cir. 1986), cert. denied, 109 S.

Ct. 1347 (1987). Cf. Milton v. Weinberger, 645 F.2d 1070, 1076

(D.C. Cir. 1981) (case involved specific instances of discrimina

tion that could not be causally connected to an unlawful program

of discrimination).

Since plaintiffs challenge longstanding practices in

the selection of union members, which were in effect up to the

filing of this law suit, this case undoubtably falls into the

class of matters where the "continuing violation" theory applies.

Thus, it was appropriate for the District Court to consider the

29

discriminatory effects of this ongoing practice during the period

before and after the date of the limitations period date under

Section 1981 and Title VII. There simply has been no error here.

The Local's invitation to this Court to depart from its well-

established precedent should be ignored.

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY FOUND THE INTERNATIONAL

AND CCC LIABLE FOR THE DISCRIMINATORY BARRIERS TO

TO UNION MEMBERSHIP.___________________________________

The International and CCC argue that the District Court

erred when it found them jointly liable with the Local for the

discriminatory barriers to entry into the Union. Although their

principal dispute is with the District Court's factual findings,

they also argue they were inappropriately found vicariously

liable for the acts of the Local union. (International Brief,

at 11-13; CCC Brief at 77-93.) Under Title VII, however, the

case law unquestionably supports the District Court's finding of

liability with respect to both the International and CCC on

grounds that they violated their affirmative duty to root out and

eliminate discriminatory practices by the Local. Further, with

respect to Section 1981, this argument is based on the erroneous

assumption that the District Court employed the theory of

respondeat superior when imposing liability.

30

A. Under Applicable Case Law, The International

is Liable for the Discriminatory Barriers

to Union Membership.__________________ ________

It is well-established that an international union is

liable for the discriminatory acts of the local union whenever

there is a sufficent connection between the international union

and the discriminatory act. Howard v. International Molders and

Allied Workers Union, 799 F.2d 1546, 1548 (11th Cir.), cert.

denied, 106 S. Ct. 2902 (1986). When the record shows that the

international has the right to control the activities of the

local, the law places an affirmative duty on the international

18/union to police the locals' activities.—

Here, there is no doubt that the International had a

duty to police the activities of the Local to prevent the perpet

uation of past discrimination against black rodmen. As the Dis

trict Court found, the International's constitution gave it the

power to exercise complete control over all aspects of the

Local's activities. And the International actually participated

18/ Myers v. Gilman Paper Coro,, 544 F.2d 837, 850 (5th

Cir.), mod i f i ed on other grounds, 556 F.2d 758 , cert, dismissed,

434 U.S. 801 (1977) (labor organizations have affirmative duty to

"prevent the perpetuation of past discrimination...."); Kaplan v ■

IATSE, 525 F .2d 1354 (9th Cir. 1975) (under Title VII, an

international must scrutinize closely the practices of its local

officials to reveal discriminatory acts or consequences);

Wheeler v. American Home Products Coro., 19 FEP Cas. 143, 146

(N.D. Ga. 1979) (". . . Title VII places an affirmative_obiiga-

tion upon umbrella labor organizations such as international

unions to take reasonable steps to end discrimination . . . .").

31

in the Local's discriminatory activities in a number of ways.

For instance, it was instrumental in the establishment of the

Apprenticeship Program, the Training Program and the

implemetation of the membership exam. (Finding of Fact, HI 130-

134.) Thus, the International misses the point when it argues

that it should not be held liable under the principles of vicari

ous liability. It simply fails to understand that liability was

imposed here because it violated its own, well-established duty

under Title VII to root out and correct discriminatory practices

on the part of its local af f i 1 iates / The District Court did

not err when it ruled that the International was liable for

violating Title VII.

Nor did it err when finding the International liable

under Section 1981. The rights embodied in this federal statu

tory provision redress "a fundamental injury to the individual

rights of a person." Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., Nos. 85-1626;

85-2010, slip op. at 4 (U.S. June 19, 1987). As this court has

recognized, Section 1981 "provide[s] remedies for a broad range

of actions that could be characterized as various state torts."

Banks v. Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone, 802 F.2d 1416, 1421

(D.C. Cir. 1985). Thus, it was appropriate for a District Court

to look to common-law tort principals of joint liability when

19/ Indeed, most of the cases cited by the International

involve labor relations, not Title VII. See, e .g ., Carbon Fuel

Co. v. United States Mine Workers, 444 U.S. 212 (1979).

32

imposing liability because CCC had been closely associated with

the discriminatory practices of the Local and the International.

The District Court's finding that the International was

liable under Section 1981 is supported by either of two

well-established theories of common-law tort liability:

respondeat superior or concerted action. First, in the circum

stances, the International and Local had the type of princi-

pal/agent relationship that under the common law would render the

International liable for the acts of the Local. See Prosse_r_and

Keeton on Torts, 501-502, 505-506 (5th ed. 1984). Second, with

respect to concerted action, the International engaged in a com

mon plan to discriminate when it permitted the Local to continue

its discriminatory practices with respect to black rodmen after

it became aware of this discrimination. (Findings, U 136.)

'Thus, the International's liability is not vicarious, but is

imposed on the International for its direct participation in the

establishment of the discriminatory barriers to union memberships

and the perpetuation of the referral system.

3. The Court Below Properly Imposed

Liability on CCC.__________ _

The District Court correctly held CCC liable under

Title VII. Title VII imposes a duty on all secondary parties

involved with discriminatory practices to inquire into and elimi

nate discriminatory practices. Myers v. Gilman Paper Corp, 544

33

F.2d at 850 (both labor organizations and employers have an

affirmative duty to prevent the perpetuation of past discrimina

tion). The courts have imposed this duty on multiemployer bar

gaining associations such as the CCC. For instance, one court

found the local division of the National Electrical Contractors

Association liable for discriminatory practices engaged in by the

Joint Apprenticeship Committe of the Union with which it entered

into a collective bargaining agreement. United States v. United

Association of Journeymen & Apprentices, 364 F. Supp. 808 (D.

N.J. 1973). In another case, the court employed similar reason

ing to deny a contractors' association's motion to dismiss where,

like this case, the association operated an apprenticeship pro

gram jointly with the union. Byrd v. Local Union No. 24

International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, 375 F. Supp.

545, 560-63 (D. Md. 1974). See also Macklin v. Soector Freight

Sys., Inc., 478 F.2d 979, 889 (D.C. Cir. 1973), aff'd mem. 547

F .2d 706 (D.C. Cir. 1977) (passivity at bargaining table between

union and employer can constitute a violation of Title VII).

The District Court did not err when it found CCC liable

under Section 1981. CCC's reliance on the the Supreme Court's

decision in General Building Contractor Association, Inc, v.

Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 375 (1982), is inapposite. Although the

General Building court ruled that the trial court had inappropri

ately applied the theory of respondeat superior when finding the

contractors association liable, id. at 375, nothing in the

34

opinion of the court disapproves the use of common law theories

of tort liability to determine the liability of secondary parties

for discriminatory practices under Section 1981. Indeed, the

concurrence in that case specifically stated that the opinion of

the court was based on the failure of the trial court to make the

appropriate factual findings, and went on to instruct the plain

tiffs that the court's opinion did not prevent them from

"attempting to prove" the traditional elements of respondeat

superior on remand. I_d. at 403-404 (1982) (O'Connor, J. concur

ring.) Thus, contrary to the Appellants' claims, General

Building does not preclude the application under Section 1981 of

a respondeat superior theory of liability to a contractors asso

ciation such as CCC.

Further, the District Court's decision did not rely

upon the theory of respondeat superior when imposing liability on

CCC. Instead, the District Court's ruling makes it abundantly

clear that the imposition of liability on CCC resulted from its

participation in, and control over, the Apprenticeship Program

and referral system. (Conclusions of Law, 1HT 32.) The District

Court was, in effect, applying a theory of common-law, joint

tortfeasor liability, which imposes direct, not vicarious,

liability on anyone associated with a common endeavor that

injures another 2 0 / In light of the judicial recognition that

20/ Prosser and Keeton on Torts, 322, 323 (5th Ed. 1984)

("All those who in pursuance of a common plan or design commit a

[Footnote continued next page]

Section 1981 claims are analogous to tort actions for personal

injury, see Goodman v. Luken Steel, Nos. 85-1626; 85-2010, Slip

opinion, at 4; Banks v. Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Co..,

802 F .2d, at 1142, the District Court's finding that CCC was

liable because of its knowing participation in the Union's

discriminatory practice should be upheld as valid application of

common-law tort principals to the analogous wrongs embodied in

Section 1981. (Findings, H 144.)

V. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER PROVIDED THE PLAINTIFFS WITH

APPROPRIATE REMEDIES FOR PAST DISCRIMINATION.__________

As a last ditch effort to avoid making amends for their

discriminatory practices, Appelants challenge the appropriateness

of the District Court's remedial order. In particular, they com

plain that the Amended Order exceeds the necessary relief by

eliminating the training program and, thereby, permitting unqual

ified individuals to enter the rodmen's union. (Local's Brief,

at 120- 130.) These arguments are not supported by the case law

or the facts.

The relief provided by the amended order to the injured

class members is consistent with recent precedent addressing

[Footnote continued from preceding page]

tortious act, actively take part in it, or furthers it by

cooperation or request, or who lend aid or encouragement to the

wrongdoer, or ratify and adopt the wrongdoers' acts done_tor

the i r bene f i t, are equally liable.") (Emphasis added).

36

similar issues that have arisen in other Title VII and Section

1981 cases. For instance, in Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers

International Association v. EEOC, 106 S. Ct. 3019 (1986), the

Supreme Court held that affirmative relief is "appropriate where

an employer or a labor union has engaged in persistent or egre

gious discrimination, or where necessary to dissipate the lin

gering effects of pervasive discrimination." Id., at 3034. Such

affirmative relief is appropriate even though it may benefit per

sons who were not actual victims of discrimination." Id., at

3035. Indeed, the relief provided here is perfectly consistent

with the "broad discretion" courts enjoy under Title VII when

exercising their equitable powers to fashion the most complete

relief possible. Id., at 3045, citing, 118 Cong. Rec. 7168

( 1972 ) .

Further, even though in Sheet Metal Workers the Supreme

Court stated that a court cannot order a union to admit unquali

fied individuals, id., at 3035, the amended order here has no

such effect. The District court's original order required the

Union to admit all class members that had worked at least 2150

hours -- the time period used by the Union to select individuals

to take the journeyman exam during the "open period." (Find

ings, H 34.) After a stay was granted pending appeal, the par

ties negotiated and filed an amended order, which increased the