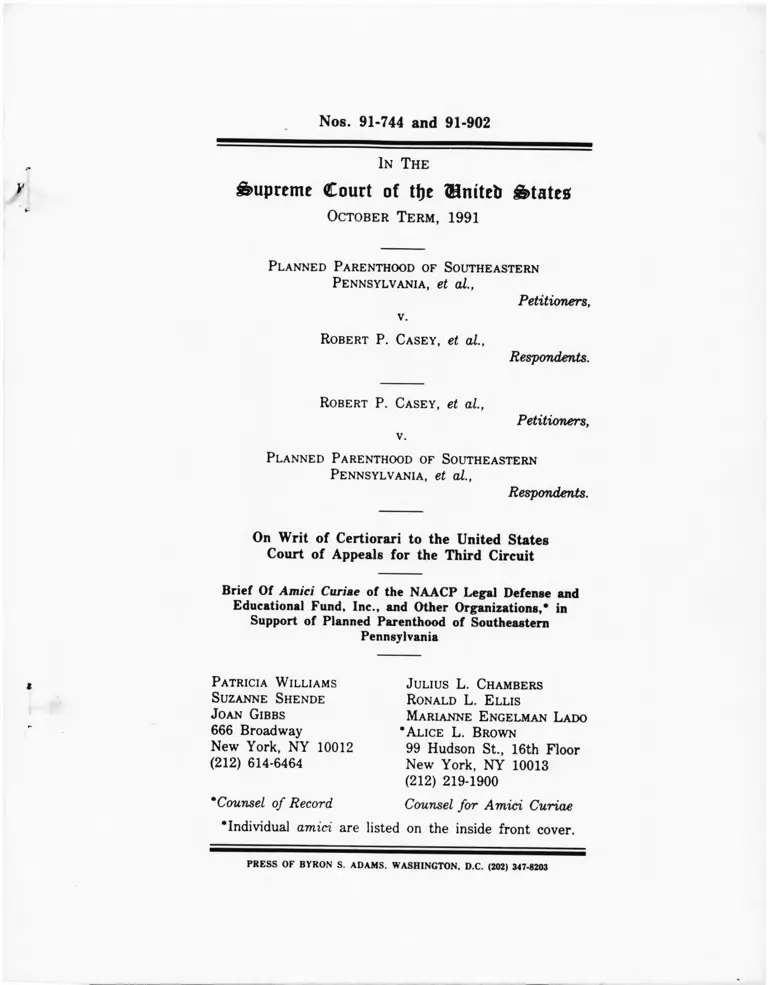

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey Brief Amici Curiae, 1991. ab0dca62-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5da38eec-a67f-4c6e-ab87-1e885943d8de/planned-parenthood-of-southeastern-pennsylvania-v-casey-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed March 03, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 91-744 and 91-902

In The

v Supreme Court of ttje fHmteti Stated

October Term , 1991

P lanned P arenthood of Southeastern

P ennsylvania , et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Robert P. Ca sey , et al.,

Robert P. Ca sey , et al.,

Respondents.

Petitioners,

v.

P lanned P arenthood of S outheastern

P ennsylvania , et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

Brief Of Amici Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., and Other Organizations,* in

Support of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern

Pennsylvania

P atricia W illiams

S uzanne S hende

Joan Gibbs

666 Broadway

New York, NY 10012

(212) 614-6464

* Counsel of Record

J ulius L. Chambers

Ronald L. E llis

Marianne E ngelman Lado

'A lice L. B rown

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Amici Curiae

‘ Individual am ici are listed on the inside front cover.

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS. WASHINGTON. D.C. (202) 347-8203

ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL

FUND, THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS,

CENTER FOR LAW AND SOCIAL JUSTICE AT

MEDGAR EVERS COLLEGE,

THE COMMITTEE FOR HISPANIC CHILDREN AND

FAMILIES,

ECO-JUSTICE PROJECT & NETWORK,

HISPANIC HEALTH COUNCIL,

JAPANESE AMERICAN CITIZENS LEAGUE,

THE LATINA ROUNDTABLE ON HEALTH AND

REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS, MADRE,

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND,

THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SOCIAL WORKERS,

NATIONAL BLACK WOMEN’S HEALTH PROJECT,

THE NATIONAL COALITION FOR BLACK LESBIANS

AND GAYS,

THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF NEGRO WOMEN, INC.,

THE NATIONAL EMERGENCY CIVIL LIBERTIES

COMMITTEE,

NATIONAL LATINA HEALTH ORGANIZATION,

NATIONAL MINORITY AIDS COUNCIL,

THE NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN’S HEALTH

EDUCATION RESOURCE CENTER,

THE NEW YORK WOMEN’S FOUNDATION,

THE PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND,

THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER,

WOMEN FOR RACIAL & ECONOMIC EQUALITY,

THE WOMEN’S POLICY GROUP.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether provisions of the Pennsylvania Abortion

Control Act that impose a 24-hour waiting period

before the performance of an abortion (18 Pa. Cons.

Stat. Ann. § 3205(a) (informed consent)), mandate

parental consent (18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3206),

and require spousal notification (18 Pa. Cons. Stat.

Ann. § 3209) unduly burden women’s right to

privacy.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTION PRESENTED......................................................................i

TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................... ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...............................................................iv

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ..................................................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARG UM ENT....................................................... 5

ARGUM ENT....................................................................................... 6

INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 6

A. L A W S T H A T O P E R A T E TO

INTERFERE WITH OR IMPAIR

ACCESS TO ABORTIONS BURDEN

THE PRIVACY RIGHTS OF POOR

W O M E N ................................................................. 16

B. P E N N S Y L V A N I A ’S A B O R T I O N

CONTROL ACT WOULD IMPEDE THE

DECISION-MAKING PROCESS AND

THE EXERCISE OF THE RIGHT TO

REPRODUCTIVE CHOICE FOR POOR

WOMEN AND THUS CONSTITUTES A

BURDEN ON THE RIGHT TO

PR IV A C Y .............................................................. 19

1. Section 3205(a) of the Act, which

requires a 24-hour delay between

the lime that a woman’s consent for

an abortion is obtained and the

actual time when the procedure is

performed, burdens the right to

abortion..................................................... 19

I ll

2. Section 3206 of the Act, which

requires parental consent before an

abortion can be obtained, burdens

the rights of low-income young

women, creating a virtual bar to

abortion..................................................... 25

3. Section 3209 of the Act, which

requires spousal notification before

an abortion can be obtained,

burdens the right to abortion................ 30

CONCLUSION .................................................................................. 34

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Akron v. Akron Clr. for Reproductive Health,

462 U.S. 416 (1983) ........................................ 8, 11-14, 32

Beal v. Doe, 432 U.S. 438 (1 9 7 7 )............................................... 10, 32

Bellotti v. Baird, 443 U.S. 622 (1 9 7 9 )............................................. 25

Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179 (1973) ................................... 15, 31, 32

Eu v. San Francisco Democratic Comm., 489 U.S. 214 (1989) . 12

Fitzgerald v. Porter Memorial Hospital, 523 F.2d 716

(7th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 425 U.S. 916 (1 9 7 6 ) .......... 9

Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980) ................................ 8, 10, 32

Hodgson v. Minnesota, 497 U .S .__,111 L.Ed.2d 344, (1990) . . 8,

14, 25, 27, 28, 30

Hodgson v. Minnesota, 648 F. Supp. 756 (D. Minn. 1986) . . . . 28

Jacobson v. Mass., 197 U.S. 11 (1905) .......................................... 15

Leigh v. Olson, 497 F.Supp. 1340 (D.N.D. 1980)......................... 21

Maher v. Roe, 432 U.S. 464 (1977) ................................... 12,13,31

Planned Parenthood Ass’n of Kansas City, Missouri

v. Ashcroft, 462 U.S. 476 (1983) .................................... 13

Planned Parenthood of Missouri v. Danforth,

428 U.S. 52 (1976) ................................................ 11,13,32

Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 947 F.2d 682

(3d Cir. 1991)............................................................ 16, 17, 30

Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 744 F. Supp. 1323 (E.D. Pa.

1 9 9 0 ) ........................................................................................ 30

V

Pages:

Poelker v. Doe 432 U.S. 519 (1 9 7 7 ) ............................................... 32

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1 9 7 3 ).......................................... passim

Rust v. Sullivan, 500 U.S. _ , 114 L.Ed.2d 233 (1 9 9 1 ) ............... 32

Tashjihan v. Republican Party, 479 U.S. 208 (1986) .................. 13

Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists, 476 U.S. 747 (1986) ...................... 8, 32, 33

U.S. v. Kras, 409 U.S. 434 (1973)....................................................... 4

Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, 492 U.S. 490

(1989) ............................................................................... 15, 32

VI

Statutes: Pages:

18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3205 ............................................. 7, 19, 23

18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3206 .......................................................... 7

18 Pa. Cons. Stai. Ann. § 3209 .................................................... 7, 30

Other Authorities: Pages:

American Civil Liberties Union Reproductive Freedom

Project, Parental Notification Laws: Their

Catastrophic Impact on Teenagers’ Right to

Abortion 15 (1986) ............................................................... 28

American Medical Association, Council on Ethical and

Judicial Affairs, Black-White Disparities in

Health Care 263 J.A.M.A. 2344 (May 2, 1990) ............. 10

Association for Sickle Cell Education Research and

Treatment Inc. Sickle Cell Anemia: A Family

Affair (1 9 8 8 ) ........................................................................... 24

Avery, A Question of Survival/A Conspiracy of Silence: Abortion

and Black Women‘s Health, in FROM ABORTION

to Reproductive Freedom: Transforming

a Movement 75 (Fried ed. 1 9 9 0 )................................... 20

Belkin, Women in Rural Areas Face Martv Barriers to

Abortion, N.Y. Times, July 11, 1989, at Al,

col. 3 ........................................................................................ 22

Bland, Racial and Ethnic Influences: The Black Woman

and Abortion, in PSYCHIATRIC ASPECTS OF

Abortion 171 (Stotland ed. 1991) ................................. 10

Bonavoglia, Kathy's Dav in Court in FROM ABORTION

to Reproductive F reedom : Transforming

a Movem ent 161 (Fried ed. 1990) ................................. 27

Vll

Cates & Grimes, Morbidity and Morality of Abortion in

the United States, in Abortion and Sterilization:

Medical and Social Aspects 155 (Hodson ed. 1981) . . . 29

Cates & Rochat, Illegal Abortion in the United States:

1972-1974, 8 Fam. Plan. Persp. 86 (1 9 8 6 ) ......................... 4

Cates, Schulz, Grimes and Tyler, The Effect of Delay

and Method Choice on the Risk of Abortion

Morbidity, 9 Fam. Plan. Persp. 266

(Nov./Dec. 1977)................................................................... 23

Centers for Disease Control, HIVIAIDS Surveillance:

Year-End Edition, 15 (January, 1992) .............................. 24

Dixon, Ross, Avery & Jenkins, Reproductive Health of

Black Women and Other Women of Color in

From A bortion to Reproductive Freedom :

Transforming a Movement 157 (Fried ed. 1990) . . . 3

Drury & Powell, Prevalence of Known Diabetes Among

Black Americans, in ADVANCE Data FROM

Vital and Health Statistics, Pub. No. (PHS)

87-1250 .................................................................................. 24

Foes Successfully Chip Away at Abortion Rights;

Poor, Young Affected Most, USA Today,

June 3, 1991, at 6 A .............................................................. 22

Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: Die World Die Slaves Made

(1st Vintage Books Ed. 1972) .......................................... 10

Gold, Abortion and Women’s Health; A Turning

Point for America? The Alan Guttmacher Institute . . . . 3

Grimes, Second-Tnmester Abortions in the United States,

16 Fam. Plan. Persp. 260 (Nov./Dec. 1984).................... 29

Henshaw & Wallisch, Die Medicaid Cutoff and Abortion Services

for the Poor, 16 Fam. Plan. Persp. 170 (1984) .................. 3

Vlll

Henshaw, Forrest & Van Vort, Abortion Services in the

United States, 1984 <4 1985, 19 Fam. Plan. Persp.

63 (1987) ................................................................................ 21

Koonin, Kochanek, Smith & Ramick, Abortion Surveillance,

United States, 1988, 40 Morbidity & Morality 17

(July, 1991) ........................................................................... 20,

28

Lincoln, Doring-Bradley, Lindheim & Cotterill, The Court,

The Congress and the President: Turning Back

the Clock on the Pregnant Poor, 9 Fam. Plan.

Persp. 210 (Sept./Oct. 1977) ............................................. 20

National Abortion Rights Action League Foundation,

Who Decides? A Reproductive Rights Manual

10 (1990) ............................................................ 18, 26, 28, 29

Nsiah-Jefferson, Reproductive Laws, Women of Color,

and Low Income Women, in REPRODUCTIVE Laws

for the 1990’s: A Briefing Handbook (1988) . . . 22

O’Hair, A Brief Historv of Abortion in the United States,

262 J.A.M.A. 1875 (1989) .................................................. 18

O’Keefe & Jones, Easing Restrictions on Minor’s Abortion

Rights, Issues in Sci. & Tech. 74 (Fall, 1990).................. 26

Radecki, A Racial and Ethnic Comparison of Family Formation

and Contraceptive Practices Among Low-Income Women,

106 Pub. Health Rep. 494 (Sept./Oct. 1991).................... 18

Roberts, 77te Future of Reproductive Choice for Poor

Women and Women of Color, 12 Women’s Law

Reporter 59 (1 9 9 0 ) ................................................................. 9

Scott, HHC Finds Hospitals Hurl by Budget Cuts, N.Y.

Newsday, March 4, 1992, at 21 ........................................ 20

Sharpe, 17 Year Old Died of Fear and Abortion, Cincinnati

Enquirer, Nov. 26, 1989........................................................ 26

IX

Siegel, Reasoning from the Body: A Historical Perspective

on Abortion Regulation and Questions of Equal Protection,

44 Stan. L. Rev. 261 (January, 1992) .............................. 16

The Alan Guttmacher Institute, Abortions and the Poor:

Private Morality, Public Responsibility (1979) .................. 18

United States Commission on Civil Rights, The Economic

Status of Black Women (1990) ............................................. 7

United States Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of Census,

Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1991,

No. 748 (1991) ........................................................................ 7

United States Dept, of Health and Human Services, I Report

of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority

Health (1985)'........................................................................ 24

United States Dept, of Health and Human Services, Health

Status of Minorities and Low-Income Groups: Third

Edition (1991)................................................................. 10, 24

United States Dept, of Health and Human Services,

Office of Minority Health, Diabetes and Minorities

in Closing the Gap (1988) ............................................. 24

United States Dept, of Health and Human Services, 1 Report

of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority

Health (1986) ..................................................................... 7, 24

Wilkerson, Michigan Judges' Views of Abortion Are Berated,

N.Y. Times, May 3, 1991.................................................... 27

Zambrana, Research Issues Affecting Poor and Minority Women:

A Model for Understanding Health Needs, 14 Women

and Health 137 (1988) ....................................................... 10

Nos. 91-744 and 91-902

In The

Supreme Court of tfje Hmteb ii>tate£f

October Term , 1991

PLANNED PARENTHOOD OF SOUTHEASTERN

PENNSYLVANIA, et al,

v.

Petitioners,

ROBERT P. CASEY, et al.,

ROBERT P. CASEY, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

PLANNED PARENTHOOD OF SOUTHEASTERN

PENNSYLVANIA, et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. and Other Organizations as Amiens Curiae in

Support of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern

Pennsylvania

INTEREST OP AMICI CURIAE

This brief is filed on behalf of twenty-four

organizations that share a deep concern for the health and

life chances of poor women, and particularly, for poor

2

women of color -- Le., African American, Latina, Asian

American and Native American women. Our ranks include

attorneys, medical professionals, community educators, and

researchers, who fear the devastating effects of greater

governmental interference in the reproductive choices of

poor women and the provision of abortion services.

Poor women lack access to the quality health care

services that more affluent Americans take for granted.

Poor communities have few health care providers and poor

women are already forced to wait long hours in overcrowded

clinics and emergency rooms and to travel at great expense

for needed services. As fifteen studies recently reviewed by

the Institute of Medicine found, financial barriers,

particularly inadequate insurance coverage and limited

personal funds, are the most important obstacle to care

seeking among women receiving insufficient care. United

States Dept, of Health and Human Services, Health Status o f

Minorities and Low-Income Groups: Third Edition 99 (1991).

Indeed, simply paying for the abortion procedure itself

3

entails serious hardship for indigent women who, in order to

exercise their right to abortion, must often let bills go unpaid

or buy fewer necessities, such as food and clothing.

Henshaw & Wallisch, The Medicaid Cutoff and Abortion

Services for the Poor, 16 Fam. Plan. Persp. 170, 171 (1984).

Amici are concerned about the adverse impact of statutory

provisions that require women to delay treatment, to

undertake multiple efforts to obtain care, and to overcome

other psychological and procedural obstacles, such as those

posed by the need to obtain spousal notification and

parental consent.

In 1969, fully seventy-five percent of all the women

who died of illegal abortions in the United States were

women of color, and from 1972 to 1974, the rate of mortality

from illegal abortions for women of color was twelve times

greater than that of white women. Gold, Abortion and

Women’s Health: A Turning Point for America? The Alan

Guttmacher Institute 5 (1990)(hereinafter cited as Gold);

Dixon, Ross, Avery & Jenkins, Reproductive Health o f Black

4

Women and Other Women o f Color in From Abortion TO

Reproductive Freedom: Transforming a Movement

157 (Fried ed. 1990). Even after legalization, high numbers

of poor women of color were still precluded from obtaining

safe and legal abortions. As a result, in 1975 women of

color comprised eighty percent of the deaths associated with

illegal abortions. Cates & Rochat, Illegal Abortion in the

United States: 1972-1974, 8 Fam. Plan. Persp. 86, 87 (1986).

If the undue burden standard is to be adopted, it is

crucial that the Court seriously consider the impact of

statutory restrictions in the real world context in which poor

women live. As Justice Marshall admonished nearly two

decades ago, "It may be easy for some people to think that

weekly savings of less than $2 are no burden. But no one

who has had close contact with poor people can fail to

understand how close to the margin of survival many of

them are." U.S. v. Kras, 409 U.S. 434, 460 (1973)(Marshall,

J., dissenting). Restrictions on the provision of abortion

services and the decision-making process do not fall with

5

equal measure upon rich and poor, and the burdens imposed

on poor women should not be ignored.

A complete list of amici and their statements of

interest are set forth in an Appendix to this brief.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Amici, supporting Planned Parenthood of

Southeastern Pennsylvania, urge this Court to reaffirm Roe

v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). If, however, the Court adopts

the undue burden test developed by Justice O’Connor, the

Court would nevertheless be required to find the provisions

of the Pennsylvania Abortion Control Act that define

medical emergency, establish reporting requirements, and

require informed consent, parental consent, and spousal

notification unconstitutional.

The right to privacy is guaranteed to all women,

regardless of income, race, or ethnicity. Accordingly, if the

Court chooses to adopt the "undue burden" standard

articulated by Justice O’Connor, the threshold examination

of the statute’s "burden" must include the practical impact of

6

the law on the ability of poor women to exercise the

protected right. Laws that place obstacles in the path of

poor women who have chosen to terminate pregnancy — by

imposing delays or procedural obstacles, economic barriers,

or other impediments to access — constitute a burden on the

privacy rights of poor women.

The Pennsylvania provisions under review would

impose enormous burdens on the abortion decisions of poor

women. The 24-hour delay, parental consent, and spousal

notification requirements, in particular, erect prohibitive

barriers in the path of poor women who seek abortions,

thereby threatening the health of, and life chances for, many

women. These provisions, thus, constitute an undue burden

on women’s right to reproductive choice.

ARGUMENT

INTRODUCTION

The Court of Appeals erred in upholding the

constitutionality of provisions of Pennsylvania’s Abortion

Control Act that force women to wait 24 hours between the

7

time that a woman’s consent for abortion is obtained and

the time that the abortion may be performed (18 Pa. Cons.

Stat. Ann. § 3205(a) (informed consent)) and that mandate

parental consent (18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3206). Through

these provisions, as well as the Act’s spousal notification

requirement (18 Pa. Cons. Ann. § 3209), the state of

Pennsylvania would actively restrict the provision of, and

access to, abortion services.1 The provisions unduly burden

the right to privacy, particularly for poor women,2 and are,

‘The issues presently before this Court pertain to five provisions

of the Pennsylvania Abortion Control Act, i.e. (1) the definition of

medical emergency; (2) informed consent; (3) parental consent; (4)

reporting requirements; and (5) spousal notification. Amici assert

that each of these provisions would have a severe and drastic impact

upon the cost and timing of abortions, as well as the number of legal

providers, and, consequently, would place an undue burden on a

woman’s abortion decision. The focus of this brief, however, is

limited to the three provisions listed in the above text.

2Laws that restrict the provision of, and access to, abortion

services for poor women will necessarily affect a high percentage of

women of color. African American women, for example, are five

times more likely to live in poverty and three times more likely to be

unemployed than white women. United States Commission on Civil

Rights, The Economic Status of Black Women 1 (1990). Indeed, the

percentage of people of color living in poverty in the United States

is dramatically high: 29% of Native Americans, United States Dept,

of Health and Human Services, 1 Report of the Secretary’s Task Force

on Black and Minority Health 51 (1986), 31% of African Americans,

and 26% of Latinos, as compared to 10% of whites. United States

8

therefore, unconstitutional.

In Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. at 153, this Court

recognized that the right to privacy "is broad enough to

encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate

her pregnancy." This Court has repeatedly affirmed its

recognition of "a freedom of personal choice in certain

matters of marriage and family life ... [which] includes the

freedom of a woman to decide whether to terminate a

pregnancy." See, e.g., Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297, 312

(1980); Akron v. Akron Ctr. for Reproductive Health, 462 U.S.

416, 420, n. 1 (1983); Hodgson v. Minnesota, 497 U .S._, 111

L.Ed.2d 344, 360 (1990). As Justice Stevens has reminded

us, the Court’s abortion cases implicate basic, fundamental

values and address "the individual’s right to make certain

unusually important decisions that will affect [her] own, or

[her] family’s destiny." Thornburgh v. American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 476 U.S. 747, 781, n. 11

Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of Census, Statistical Abstract o f the

United States, 1991, No. 748, 463 (1991)(1989 data).

9

(1986)(quoting Fitzgerald v. Porter Memorial Hospital, 523

F.2d 716, 719-20 (7th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 425 U.S. 916

(1976)).

For poor women, and particularly for poor African

American women, the right to privacy in matters of body

and reproduction — a right that was trammeled with state

sanction during centuries of slavery -- is fundamental to

notions of freedom and liberty. For years, governmental

protection of the individual’s person or her private decision

making was non-existent. The right to make and carry out

reproductive decisions without governmental intrusion or

government sanctioned interference was, and continues to

be, a valued part of freedom. See generally Roberts, The

Future of Reproductive Choice for Poor Women and Women

of Color, 12 Women’s Law Reporter 59 (1990)(analysis of

the historical significance for poor African American women

of reproductive choice and the "struggle against fearful and

overwhelming odds... to maintain and protect that which

woman holds dearer than life... to keep hallowed their own

10

persons...."); Bland, Racial and Ethnic Influences: The Black

Woman and Abortion, in PSYCHIATRIC ASPECTS OF

A b o r t io n 171 (Stotland ed. 1991); Genovese, Roll, Jordan,

Roll: The World The Slaves Made 497-98 (1st Vintage Books

Ed. 1972).3

Roe and its progeny established the limits of state

authority to regulate the performance of abortions and

announced the standards of review by which restrictions on

3Even today poor women of color are often unable to share in the

freedom of personal choice in matters of reproduction guaranteed

by Roe. Poor women often lack the economic means to avail

themselves of health services and are alienated by the inaccessibility

of health care. The tragic effects of what is truly a health care crisis

for poor women are well known and widely documented. See, e.g.,

United States Dept, of Health and Human Services, Health Status of

Minorities and Low-Income Groups: Third Edition 99 (1991); Bland,

Racial and Ethnic Influences: The Black Woman and Abortion,

Psychiatric Aspects of Abortion 171 (Stotland ed. 1991);

Zambrana, Research Issues Affecting Poor and Minority Women: A

Model for Understanding Health Needs, 14 Women and Health 137,

148-50 (1988); American Medical Association, Council on Ethical and

Judicial Affairs, Black-White Disparities in Health Care 263 J.A.M.A.

2344 (May 2, 1990)("Underlying the racial disparities in the quality of

health among Americans are differences in both need and access.

Blacks are more likely to require health care but are less likely to

receive health care services."); see also Harris, 448 U.S. at 339

(1977)(Marshall, J., dissenting); Beal v. Doe, 432 U.S. 438, 455, n. 1,

459 (1977)(Marshall, J., dissenting)(taking note of the paucity of

abortion providers available to poor women and the lack of a

"meaningful opportunity" to obtain an abortion).

11

this right are to be adjudged. "Where certain ‘fundamental

rights’ are involved, the Court has held that regulation

limiting these rights may be justified only by a ‘compelling

state interest’ ... and that legislative enactments must be

narrowly drawn to express only the legitimate state interests

at stake." Roe, 410 U.S. at 155, 164-66; see Planned

Parenthood o f Missouri v. Danforth, 428 U.S. 52, 61 (1976).

Amici join Planned Parenthood of Southeastern

Pennsylvania in urging this Court to reaffirm Roe v. Wade.

If, however, the Court adopts the undue burden test

developed by Justice O’Connor, the Court’s prior decisions

would also require reversal of the Third Circuit, which failed

to analyze properly the burden imposed by the Pennsylvania

statute.

In Akron, Justice O’Connor articulated the

conceptual basis for the undue burden standard:

This Court has acknowledged that ‘the right

in Roe v. Wade can be understood only by

considering both the woman’s interest and the

nature of the State’s interference with it. Roe

did not declare an unqualified ‘constitutional

right to an abortion’.... Rather, the right

12

protects the woman from unduly burdensome

interference with her freedom to decide

whether to terminate her pregnancy.’

Akron, 462 U.S. at 461 (O’Connor, J., dissenting)(quoting

Maher v. Roe, 432 U.S. 464, 473-74 (1977)). If a statute

"places no obstacles -- absolute or otherwise -- in the

pregnant woman’s path to an abortion" and imposes "no

restriction," then, as this Court found in Maher, the

"regulation does not impinge upon the fundamental right

recognized in Roe," and the judicial inquiry has come to

closure. Maher, 432 U.S. at 474. If, however, a regulation

infringes, interferes, or coercively constrains the free exercise

of the right, then the statutory burden is established and

must be justified.4 See Akron, 462 U.S. at 462, 464

4The Court’s application of a "burden" standard in cases involving

First and Fourteenth Amendment protections of free speech and

associational rights are instructive: the threshold issue is whether a

law burdens the right, not whether there is an undue burden. In Eu

v. San Francisco Democratic Comm., 489 U.S. 214, 222 (1989), the

Court summarized the standard applied in those cases:

To assess the constitutionality of a state election law,

we first examine whether it burdens rights protected

by the First and Fourteenth Amendments. If the

challenged law burdens the rights of political parties

and their members, it can survive constitutional

13

(O’Connor, dissenting). Accord Maher, 432 U.S. at 471

("[T]he central question in this case is whether the

regulation ‘impinges upon a fundamental right explicitly or

implicitly protected by the Constitution.’").

The application of the undue burden standard

involves two steps. First, there is a threshold assessment of

the burden imposed by a statute -- i.e., an inquiry into

whether the regulations restrict, or have a legally significant

impact upon, the right to privacy. See, e.g., Planned

Parenthood Ass’n o f Kansas City, Missouri v. Ashcroft, 462

U.S. 476, 490 (1983)(Powell, J.)(regarding the cost of a

requirement that pathology reports be conducted); Akron,

462 U.S. at 434 ("A primary burden created by the

[hospitalization] requirement is additional cost to the

woman."); Danforth, 428 U.S. at 79 (prohibition of abortion

technique after the first twelve weeks of pregnancy would

scrutiny only if the State shows that it advances a

compelling state interest and is narrowly tailored to

serve that interest.

(citations omitted). See also Tashjihan v. Republican Party, 479 U.S.

208, 213-14 (1986).

14

have the effect o f inhibiting abortions). To constitute a

burden, then, regulations need not impose an absolute bar

to obtaining an abortion or create an absolute deprivation.

See, e.g., Akron, 462 U.S. at 435 (a second-trimester

hospitalization requirement held unconstitutional upon

finding that the requirement "may force women to travel to

find available facilities, resulting in both financial expense

and additional health risk").

Second, if a statute is found to be a burden, then

courts must determine whether such burden is undue, or

lacking in adequate justification.5 Hodgson, 497 U.S. ___,

111 L.Ed.2d at 361 ("Because the Minnesota statute

5The undue burden standard cannot logically be read to require

plaintiffs to establish that the burden is undue as a threshold matter.

Cf Akron, 462 U.S. at 463 (O’Connor, J., dissenting)(The ‘undue

burden’ required in the abortion cases represents the required

threshold inquiry...."). To require such an expansive assessment as a

threshold matter would necessarily encompass a review of the

statute’s justifications and means — i.e., precisely the same issues

considered by the court after the threshold is overcome.

In this brief, Amici discuss only the proper analysis for

determining whether a protected right is "burdened" by state law.

Amici refer to the briefs submitted by other amici in support of

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania for fuller

discussion of how to determine whether the burden is "undue.”

15

unquestionably places obstacles in the pregnant minor’s path

to an abortion, the State has the burden of establishing its

constitutionality. Under any analysis, the Minnesota statute

cannot be sustained if the obstacles it imposes are not

reasonably related to legitimate state interests.") Compare

Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, 492 U.S. 490, 519

(1989)(viability testing requirement deemed justifiable even

though it would raise the cost of abortions) with Doe v.

Bolton, 410 U.S. 179, 198 (1973)("the interposition of the

hospital abortion committee is unduly restrictive of the

patient’s rights and needs..."). As the Court stated in

Jacobson v. Massachusetts, "[Tjhe rights of the individual in

respect to his liberty may at times, under the pressure o f great

dangers, be subjected to restraint...." 197 U.S. 11, 29

(1905)(emphasis added).

In assessing whether a constitutionally protected right

is burdened by state law, the Court must consider the

practical impact of the law on the ability of the individual to

exercise the protected right. In this case, the Pennsylvania

16

Abortion Control Act would so severely restrict the ability

of poor women to obtain abortions that it would render

illusory the right to make a private, procreative choice

without state interference.

A. LAWS THAT OPERATE TO INTERFERE

WITH OR IMPAIR ACCESS TO

ABORTIONS BURDEN THE PRIVACY

RIGHTS OF POOR WOMEN

Laws that burden women’s access to abortion include

those laws that deter women from obtaining abortions by

interposing procedural obstacles, economic barriers, or other

practical impediments to access. See generally Siegel,

Reasoning from the Body: A Historical Perspective on Abortion

Regulation and Questions of Equal Protection, 44 Stan. L.

Rev. 261, 371, n. 431 (1992).6 To assess whether, and the

6The Third Circuit has acknowledged that abortion regulations

infringe upon the abortion right in a number of ways, including,

(1) causing a delay before the abortion is performed;

(2) raising the monetary cost of an abortion; and (3)

reducing the availability of an abortion by directly or

indirectly causing a decrease in the number of legal

abortion providers.

Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 947 F.2d 682, 698 (3d Cir. 1991).

17

degree to which, a regulation is burdensome, courts should

not and, indeed, must not, ignore the way in which the

regulation operates, including its impact on all women.

Any analysis of whether a law that regulates or

restricts the provision of abortions burdens the right to

privacy must include an examination of the law’s burden on

poor women for the simple reason that they, too, are

guaranteed the constitutional right to privacy.7 Moreover,

poor women constitute a significant proportion of the

women who utilize abortion services. For example, women

with family incomes of under $11,000 are nearly four times

more likely to have an abortion than women with family

incomes of over $25,000.® The greater incidence of

unintended pregnancies is a consequence of (i) the greater

likelihood of experiencing contraceptive failure; and (2)

7As the Third Circuit correctly concludes, it is unnecessary that

the regulations impact upon the entire "universe of pregnant women"

in order to constitute a burden. Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 947

F.2d at 691. 8

8Gold at 16.

i

18

preferences for having fewer children than nonpoor

women.9 At least one study indicates that for women below

the poverty level, six out of ten births are unintended, i.e.,

unwanted or mistimed, compared to three out of ten births

to women above 200% of the poverty level.10

In particular, restrictions on the right to abortion fall

most heavily on poor women because they are in a worse

position to overcome barriers of cost,11 availability, or delay

imposed or generated by the regulation of abortion.

’The Alan Guttmacher Institute, Abortions and the Poor: Private

Morality, Public Responsibility at 20 (1979).

10Radecki, A Racial and Ethnic Comparison of Family Formation

and Contraceptive Practices Among Low-Income Women, 106 Pub.

Health Rep. 494, text at n. 32, 33 (Sept./Oct. 1991).

uSee O’Hair, A Brief History of Abortion in the United States, 262

J.A.M.A. 1875 (1989). Significantly, only 13 states permit the use of

state funds for medically necessary abortions. National Abortion

Rights Action League Foundation, Who Decides? A Reproductive

Rights Manual 10 (1990)(hereinafter cited as NARAL).

19

B. P E N N S Y L V A N I A ’S A B O R T I O N

CONTROL ACT WOULD IMPEDE THE

DECISION-MAKING PROCESS AND THE

EXERCISE OF THE RIGHT TO

REPRODUCTIVE CHOICE FOR POOR

WOMEN AND THUS CONSTITUTES A

BURDEN ON THE RIGHT TO PRIVACY.

Through its regulations and restrictions,

Pennsylvania’s Abortion Control Act would actively interfere

with the ability of poor women to obtain abortions. And for

many poor women, the obstacles caused by the Act would

not be merely burdensome, but insurmountable.

1. Section 3205(a) of the Act, which

requires a 24-hour delay between the

time that a woman’s consent for an

abortion is obtained and the actual

time when the procedure is

performed, burdens the right to

abortion.

First, the 24-hour delay may significantly increase the

costs of abortion for poor women because of the limited

availability of abortion services. For poor women, it is

already more difficult to find the necessary financial

resources, medical information, child care and time away

20

from work.12 The additional delay imposed by the 24-hour

waiting period -- exacerbated by the likelihood of

scheduling difficulties at overcrowded facilities at which poor

women receive care,13 as well as barriers of distance and

mobility -- will actively interfere with the ability of poor

women and women of color to obtain abortions.

The need to travel long distances already presents a

substantial barrier to care for many women. For example,

one of the plaintiff clinics in this case, the Women’s Health

12Lincoln, Doring-Bradley, Lindheim & Cotterill, The Court, The

Congress and the President: Turning Back the Clock on the Pregnant

Poor, 9 Fam. Plan. Persp. 207, 210 (Sept./Oct. 1977); Koonin,

Kochanek, Smith & Ramick, Abortion Surveillance, United States,

19S8, 40 Morbidity & Morality 17, 18 (July, 1991). Even the informal

networks built by women to ensure pregnant women access to

abortion are often inaccessible to women of color and the solutions

offered unaffordable. Avery, A Question of Survival/A Conspiracy of

Silence: Abortion and Black Women’s Health, in FROM ABORTION TO

Reproductive Freedom: Transforming a Movement 75 (Fried

ed. 1990).

‘’Overcrowded conditions at public facilities delay and frequently

foreclose timely treatment. At Health and Hospitals medical clinics

in New York City, for example, patients must wait six to twenty-two

weeks to get a first clinic appointment; women must wait four to

fifteen weeks for an appointment with a gynecologist. A recent

Health and Hospitals Corp. report found that "one patient in eight

tires of waiting in city emergency rooms and leaves without

treatment." Scott, HHC Finds Hospitals Hurt by Budget Cuts, N.Y.

Newsday, March 4, 1992, at 21.

21

Services (WHS) in Pittsburgh services an area of 34 counties

within Pennsylvania, portions of Ohio, West Virginia,

Maryland and New York. Against this backdrop, patients

travel great distances and, according to the testimony of that

agency’s Executive Director, "it is not unusual for women to

travel three, four hours to get to the clinic. Sometimes it’s

much longer because they have to take buses to get in."

Trial Testimony of Roselle, Vol. II at 80.

In 1985, eighty-two percent of all counties in the

United States -- in which one-third of all women of

reproductive age lived -- had no abortion provider.14 In

rural areas the problem is especially acute. Nine out of ten

non-metropolitan counties in the United States have no

facility that perform abortions.15 For example,

• Not a single physician in residence in the

state of North Dakota performs abortions.16

MHenshaw, Forrest & Van Vort, Abortion Services in the United

States, 19S4 & 19S5, 19 Fam. Plan. Persp. 63, 65 (1987).

liId.

'“See Leigh v. Olson, 497 F.Supp. 1340, 1347 (D.N.D. 1980).

22

• In South Dakota there is only one doctor who

will perform abortions. As a result, women

must travel hundreds of miles to obtain an

abortion.17

• In northern Minnesota, one clinic must

provide all abortions for 24 counties.18

In particular, poor Native American women face some of

the largest obstacles, since the Indian Health Services, which

may be the only familiar provider of health care and the only

health service available for hundreds of miles, is prohibited

from performing abortions even if women can find the

monetary resources to pay for the procedure themselves.19

The 24-hour delay may require duplicate journeys,

overnight stays away from home, and two or more absences

from work, often without pay, as well as added

transportation expenses. For many poor women, the

11 Foes Successfully Chip Away at Abortion Rights; Poor, Young

Affected Most, USA Today, June 3, 1991, at 6A.

18Belkin, Women in Rural Areas Face Many Barriers to Abortion,

N.Y. Times, July 11, 1989, at A l, col. 3.

l9Nsiah-Jefferson, Reproductive Laws, Women of Color, and Low

Income Women, in REPRODUCTIVE Laws FOR THE 1990’s: A

Briefing Handbook 21-22 (1988).

23

additional expense caused by the waiting period will be

prohibitive.

Secondly, Section 3205(a) may often result in delays

greater than the 24 hours required by statute. The

Executive Director of WHS in Pittsburgh testified that her

agency would not be able to guarantee that delays would be

limited to 24 hours because physicians are not available

every day of the week. Trial Testimony of Roselle, Vol. II

at 82.

Significant delays in obtaining abortions increase

dramatically the health risks associated with abortions.

"[A]ny delay increases the risk of complications to a

pregnant woman who wishes an abortion. Moreover, this

risk appears to increase continuously and linearly as the

length of gestation increases."20 The total morbidity rate

rises 20% when abortion is delayed from the eighth to the

twelfth week, and the complication rate increases 91% for

:oCates, Schulz, Grimes & Tyler, The Effect of Delay and Method

Choice on the Risk of Abortion Morbidity, 9 Fam. Plan. Persp. 266, 267

(Nov./Dec. 1977). See also Trial Testimony of Allen, Vol. I at 45.

24

that same delay.21 Poor women of color in particular, who

disproportionately suffer from illnesses exacerbated by

pregnancy,22 will be most affected by significant delays in

obtaining abortion services.

In sum, the 24-hour waiting period places poor

women at significant risk of harm and constitutes a burden.

21 Id., at 267.

22Poor women of color suffer at high rates from a variety of

serious health conditions that may be exacerbated by pregnancy.

These include high blood pressure, hypertension, diabetes, sickle cell

anemia, AIDS, and certain forms of cancer. See United States Dept,

of Health and Human Services, Health Status o f Minorities and Low-

Income Groups: Third Edition 131-58 (1991); United States Dept, of

Health and Human Services, I Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on

Black and Minority Health 74-75 (1985); United States Dept, of

Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health, Diabetes and

Minorities in CLOSING THE Gap 2 (1988); Drury & Powell, Prevalence

of Known Diabetes Among Black Americans, in ADVANCE D ata

F rom Vital and H ealth Statistics, Pub. No. (PHS) 87-1250;

Association for Sickle Cell Education Research and Treatment Inc.

Sickle Cell Anemia: A Family Affair (1988); Centers for Disease

Control, HIV/AIDS Surveillance: Year-End Edition 15 (January

1992)(comparison of annual rate of reported AIDS cases for White

females, 1.7 per 100,000, with rates for Black and Hispanic females,

24.6 and 12.6, respectively).

25

2. Section 3206 of the Act, which

requires parental consent before an

abortion can be obtained, burdens the

rights of low-income young women,

creating a virtual bar to abortion.

Although a parental consent requirement with a

judicial bypass may be legal in some circumstances, see

Hodgson, 497 U.S. at _, 111 L.Ed.2d at 375; Bellotti v.

Baird, 443 U.S. 622, 633-39 (1979)(discussion of principles to

be applied in parental consent cases), "the constitutional

protection against unjustified state intrusion into the process

of deciding whether or not to bear a child extends to

pregnant minors as well as adult women." Hodgson, 497

U.S. a t __,111 L.Ed.2d at 360. The judicial inquiry begins

with an examination of the burden imposed by the statute.

See, e.g., Hodgson, 497 U.S. a t __, 111 L.Ed.2d at 362-66.

As the Executive Director of WHS testified at trial,

the combined effect of the 24-hour delay and parental

consent provisions will be to create additional obstacles for

teenagers who, in many instances, are already in difficult

circumstances. "If you talk about a 24-hour period, we’re

26

talking about delay and additional costs. If we’re talking

about parental consent, we’re talking about additional delay.

If we talk about a judicial bypass, it’s still more delay, more

expense, more trips to the clinic." Trial Testimony of

Roselle, Vol. II at 81-82. In Massachusetts, for example, a

parental consent law forced one-third of the state’s minors

to travel to a neighboring, less restrictive state to obtain an

abortion.23

Anecdotal evidence points to the horrors of such

restrictions: high school student Rebecca Bell died in 1988

of a massive infection after an illegal abortion that she

obtained rather than telling her parents that she was

pregnant.24 Thirteen-year-old Spring Adams was shot to

death by the father who had impregnated her when he

learned that she was going to abort the pregnancy.25

■30'Keefe & Jones, Easing Restrictions on Minors’ Abortion Rights,

Issues in Sci. & Tech. 74, 78 (Fall 1990).

24Sharpe, 17 Year Old Died of Fear and Abortion, Cincinnati

Enquirer, Nov. 26, 1989, cited in NARAL at 6.

“ NARAL at 6.

27

Moreover, judicial bypass provisions frequently leave

young women and the freedom to exercise their fundamental

right to the discretion of hostile judges.26 One judge, who

openly demonstrated the impermissible grounds on which he

would base a decision, stated that he did not like the law

and that he would only allow a minor to have an abortion

without parental consent in cases of incest or the rape of a

White girl by a Black man.27 In some Minnesota counties,

judges refuse to hear petitions for judicial bypass, forcing

minors to travel 250 miles to receive a hearing. Half of the

minors who were able to utilize the bypass procedure of that

state’s notification law were not residents of the city in which

the hearing was held.23

Parental consent provisions exacerbate delay and

2bSee, e.g., Bonavoglia, K a th y ’s D a y in Court in FROM ABORTION

to Reproductive Freedom : T ransforming a Movem ent 161

(Fried ed. 1990).

:7Wilkerson, Michigan Judges’ Views of Abortion Are Berated, N.Y.

Times, May 3, 1991.

78Hodgson, 497 U.S. at __, 111 L.Ed.2d at 387 (Marshall J.,

dissenting in part).

28

increase both the cost and the risk to teens: in Minnesota,

the parental notification requirement — a far less onerous

law than Section 3206 of the Pennsylvania Abortion Control

Act — increased the number of minors who obtained second

trimester abortions by 26.5%.29 This change ran counter to

the national trend toward earlier term abortions.30

The difficulties of obtaining an abortion and the

additional obstacles created by statute fall heaviest on young

low-income women of color. The proportion of women of

color under 15 years of age who have abortions is high --

nearly double that for their white counterparts.31 For these

young women, the vast majority of whom had unintended

29NARAL at 6; Hodgson v. Minnesota, 648 F. Supp. 756 (D. Minn.

1986), aff’d and rev'd in part, 853 F.2d 1452 (8th Cir. 1988), affd, 497

U.S. 111 L.Ed.2d 344 (1990).

30American Civil Liberties Union Reproductive Freedom Project,

Parental Notification Laws: Tlieir Catastrophic Impact on Teenagers’

Right to Abortion 15 (1986).

31Koonin, Kochanek, Smith & Ramick, Abortion Surveillance,

United States, 1988, 40 Morbidity & Mortality 17 (July 1991).

29 I

pregnancies,32 abortion is a necessary health service. Laws

that place these services further from reach have a severe,

detrimental impact.

The medical dangers of abortion are already

particularly acute for adolescents, in part because they often

postpone pregnancy confirmation and abortion. See Trial

Testimony of Allen, Vol. I at 62-63. As a consequence of

the parental consent provision, compounded by the 24-hour

delay provision, teenagers will not be able to obtain abortion

services until even later, more dangerous stages of

pregnancy. The mortality rate for abortion increases fifty

percent each week after the eighth week of pregnancy, and

the risk of major complications in the procedure increases by

approximately thirty percent per week.33

“ Among teenagers, 84% of all pregnancies and 92% of pre

marital pregnancies, are unintended. NARAL at 7.

“ Grimes, Second-Trimester Abortions in the United States, 16 Fam.

Plan. Persp. 260-65 (Nov./Dec. 1984). See also Cates & Grimes,

Morbidity and Morality of Abortion in the United States, in ABORTION

and Sterilization : Medical and Social Aspects 155 (Hodson

ed. 1981).

i

!

30

3. Section 3209 of the Act, which

requires spousal notification before an

abortion can be obtained, burdens the

right to abortion.

After conducting the requisite legal and factual

analyses, the district court concluded that the spousal

notification requirement "is constitutionally defective because

it impermissibly invades a woman’s fundamental right to

privacy in the abortion decision." Planned Parenthood v.

Casey, 744 F.Supp. 1323, 1384 (E.D.Pa. 1990). On appeal,

the Third Circuit affirmed, holding that the provision

imposes an undue burden on a woman’s abortion decision

and does not serve a compelling state interest. 947 F.2d 682

(3d Cir. 1991). In reaching this conclusion, the Third Circuit

looked to this Court’s opinion in Hodgson, 497 U.S. a t __,

111 L.Ed.2d at 371, & n. 36, and observed,

The Supreme Court has thus been attuned to

the real-world consequences of forced

notification in the context of minor

child/parent relationships.... In this case, we

conclude that the real-world consequences of

forced notification in the context of

wife/husband relationships impose similar

31

kinds of undue burdens on a woman’s right to an

abortion.

947 F.2d at 711 (emphasis added). Amici fully agree. And

just as the courts should be attuned to the real-world

consequences of forced notification in the context of familial

relationships, so too should they heed the real-world burdens

caused by other statutory requirements that would unduly

burden a woman’s abortion decision.

* * *

Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton did not countenance

a test of constitutionality that would prohibit only absolute

deprivations. Roe, 410 U.S. at 164-66 (1973)(specified

standards of review); Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179

(1973)(procedural requirements held unduly restrictive).

Correspondingly, under the undue burden standard, barriers

to abortion that are constructed by government and that

would impinge upon the ability of poor women to exercise

their fundamental right must be recognized as burdensome.

Unlike the line of cases beginning with Maher v. Roe,

432 U.S. 464 (1977), and evidenced, most recently, in

32

Webster, 492 U.S. 490 (1989), and Rust v. Sullivan, 500 U.S.

__, 114 L.Ed.2d 233 (1991), this case does not involve the

question whether a state may choose not to grant benefits

that would further the provision of abortion services. See

also Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980); Poelker v. Doe 432

U.S. 519 (1977); Beal v. Doe, 432 U.S. 438 (1977). To the

contrary, the Pennsylvania laws at issue place discrete and

burdensome obstacles in the pregnant woman’s path to an

abortion. Pennsylvania is not merely encouraging an

alternative option, but, instead, actively delaying and

otherwise burdening the exercise of a protected activity.

Compare Thornburgh, 476 U.S. 747 (1986); Akron, 462 U.S.

416 (1983); Danforth, 428 U.S. 52 (1976); Doe v. Bolton, 410

U.S. 179 (1973).

"Few decisions are more personal and intimate, more

properly private, or more basic to individual dignity and

autonomy, than a woman’s decision... whether to end her

pregnancy. A woman’s right to make that choice freely is

fundamental. Any other result... would protect inadequately

33

a central part of the sphere of liberty that our law

guarantees equally to all...." Thornburgh, 476 U.S. at 772.

Amici believe that the sphere of liberty guaranteed to all

should contain protection for the right of poor women to

make reproductive choices free from intrusion by

burdensome government restrictions. We thus ask that the

Court consider the burdens of governmental restrictions on

the availability of abortions for poor women.

The provisions of the Pennsylvania Abortion Control

Act requiring a 24-hour waiting period, parental consent and

spousal notification actively interfere with women’s decision

making and the provision of abortion services, and will limit

the ability of poor women to obtain needed services. The

provisions unduly burden the right to privacy and are

unconstitutional.

34

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the Third

Circuit regarding Sections 3205(a) and 3206 should be

reversed, and the judgment regarding Section 3209 affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

RONALD L. ELLIS

MARIANNE L. ENGELMAN LADO

* ALICE L. BROWN

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

PATRICIA WILLIAMS

SUZANNE SHENDE

JOAN GIBBS

666 Broadway

New York, NY 10021

(212) 614-6464

Counsel for Amici Curiae

•Counsel of Record

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

THE ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND (AALDEF) is a national

civil rights organization that addresses the critical problems

facing Asian American communities, including the growing

trend of anti-Asian violence, immigrant rights, voting rights,

labor and employment rights, and redress for Japanese

Americans who were incarcerated in camps within the

United States during World War II. AALDEF is committed

to protecting the right to reproductive choice by women

including Asian immigrant women and joins other amici

curiae in support of reproductive choice as a fundamental

right.

♦ * *

THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS

(CCR), a litigation/education organization headquartered in

New York City, was founded in 1966. Born of the civil

rights movement and the struggles of Black people in the

United States for true equality, CCR has litigated for voting

2a

rights, civil rights, and the fundamental and necessary right

of each woman to obtain access to safe and legal abortion.

CCR decries the disproportionate and potentially devastating

effect that the limitation or loss of the right to abortion will

have on women of color and low-income and working

women, and we urge this Court to protect the right to

accessible, safe and legal abortion in their names.

* * *

THE CENTER FOR LAW AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

(CLSJ) at Medgar Evers College is a research and advocacy

institution created in 1985 by a special appropriation of the

New York State Legislature to establish a legally oriented

civil rights and social justice institution in New York City.

CLSJ conducts litigation and public policy projects on

matters involving pressing civil and human rights issues in

such areas as employment, health care and housing.

Discrimination in these areas has historically plagued

the African-American communities CLSJ serves, particularly

the women in these communities. For that reason, CLSJ

3a

joins as amicus curiae in this consolidated appeal to the

United States Supreme Court.

* * *

THE COMMITTEE FOR HISPANIC CHILDREN

AND FAMILIES is a not-for-profit organization in New

York City dedicated to promoting and strengthening the

Hispanic family. In our community education efforts we

seek to heighten awareness of issues such as domestic

violence, teen pregnancy and child abuse and neglect.

Clearly our goal is to mobilize our community in effective

prevention strategies for these and other problems which

afflict our community. Key to being able to confront these

myriad problems is the need for quality and equitable

medical care. We oppose the denial of access to health

services including abortion for Hispanic women.

* * *

THE ECO-JUSTICE PROJECT AND NETWORK

(a project of the Center for Religion, Ethnics, and Social

Policy at Cornell University) is an organization concerned

4a

about both environmental and social justice, and the well

being of all people on a thriving Earth. Our concern in this

case focuses on the effect it may have on the lives of poor

and socially disenfranchised women. Poor women, already

significantly burdened in accessing medical services, will

suffer even greater adverse consequences should the Court

strip the right to abortion of constitutional protections. We

also are concerned about women’s rights of privacy, doctors’

rights to free speech, and the physician-patient relationship

of confidentiality. In a world in which human population

may already be exceeding carrying capacity, we

wholeheartedly support a women’s right to choose whether

or not to give birth to even more human beings.

♦ * *

Founded in 1978, the HISPANIC HEALTH

COUNCIL is a community-based research, education, and

advocacy organization devoted to the improvement of health,

mental health and general social well-being of Puerto Ricans

and other Latino populations in Hartford, Connecticut.

5a

Specifically, the Council seeks to empower Latino families

for community change through education about health and

disease risks, health-related legal rights, and social

conditions underlying poverty and illness. The Council also

strives to alter existing inadequacies in the quality and

quantity of health care available to low income groups.

We join this case as amicus curiae because this kind

of legislation has only proven to be discriminatory towards

underserved populations and impacts negatively on the lives

of the poor because it does not look at other socio-economic

factors which influence people’s behavior.

* * *

THE JAPANESE AMERICAN CITIZENS

LEAGUE (JACL) is a national civil and human rights and

educational organization concerned with the welfare of

Japanese and Asian Americans. It was formed in 1929 and

is the oldest and largest Asian American civil rights

organization. The JACL is committed to educating the

public on the history, experience, contributions, and current

6a

concerns of Japanese Americans and Asian Americans in the

United States. As a civil rights organization, the JACL has

worked to guarantee justice and due process to all persons.

To that end, we are firmly committed to a women’s

fundamental right of choice and self-determination to

exercise her reproductive rights. We believe that abortion -

- choice -- is a fundamental right protected by the United

States Constitution.

* * *

THE LATINA ROUNDTABLE ON HEALTH

AND REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS (LRHRR) is an

organization of Latinas who have come together to examine

and address the legislative, judicial, and policy initiatives that

effect the health and reproductive freedom of Latinas in

New York. The LRHRR is made up of Pro-Choice health

care providers, attorneys, educators, policy makers, and

community activists who through these efforts defend the

rights of Latinas to access abortion services regardless of

age, economic or marital status.

7a

♦ * *

MADRE is a national women’s friendship

organization that sees the connections between U.S. policy

and its effects on women and children in the U.S., Central

America, the Caribbean and the Middle East. MADRE’s

work includes programs which address health care and child

care issues affecting women’s daily lives. We support

reproductive freedom and quality affordable health care for

all. We know that poor women and women of color are

most affected by restrictive policies. We therefore sign on

to the amicus brief in its opposition to any restrictions

placed on a woman’s reproductive choice.

* * *

THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND (MALDEF), established in

1967, is a national civil rights organization headquartered in

Los Angeles. Its principal objective is to secure, through

litigation and education, the civil and constitutional rights of

Hispanics living in the United States. Fundamental among

8a

those rights is the right to privacy which encompasses the

right to choose in matters of family planning. MALDEF

opposes restrictions on the right to choose, as such

restrictions are devastating in their disproportionate effect

upon low-income Hispanic women with regard to their

family planning rights, choices, and alternatives.

* * *

T H E N A A C P L E G A L D E F E N S E &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. (LDF) is a non-profit

corporation formed to assist African Americans to secure

their constitutional and civil rights and liberties. For many

years LDF has pursued litigation to secure the basic civil

and economic rights of low-income African American

families and individuals. Litigation to ensure the non-

discriminatory delivery as well as the adequacy of health care

services available to African American communities has

been a long-standing LDF concern.

Through its Black Women’s Employment and Poverty

& Justice Programs, LDF is also challenging barriers to

9a

economic advancement to help to improve the economic

status and living conditions of the many in poverty.

This case implicates the full panoply of these

important LDF concerns. Burdensome legislation can

severely limit the availability of reproductive health services

to poor African American women. This, in turn, will

increase the number of unwanted pregnancies and promote

continuing cycles of poverty and despair, while creating

unnecessary medical risks for poor, African American

women. LDF feels that it is crucial for the Court to fully

consider how statutory restrictions on abortion operate in

practice to limit the accessibility of health care for poor

women.

* * *

THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SOCIAL

WORKERS, INC. (NASW), a non-profit professional

association with over 135.000 members, is the largest

association of social workers in the United States. The

association is devoted to promoting the quality and

10a

effectiveness of social work practice, to advancing the

knowledge base of the social work profession and to

improving the quality of life through utilization of social

work knowledge and skills. NASW is deeply committed to

the principle of self-determination and to the protection of

individual rights and personal privacy. The association has

been in the forefront of the struggle for women’s equality,

and is particularly concerned in the present instance that the

state not override a pregnant woman’s autonomy nor restrict

her right to choose abortion.

♦ ♦ ♦

THE NATIONAL BLACK WOMEN’S HEALTH

PROJECT (NBWHP) is a self-help, health education and

advocacy organization which works to improve the health

status and quality of life for African American Women and

their families. It consists of 150 developing and established

chapters in 31 states serving a broad constituency of

approximately 2,000 members. The NBWHP is deeply

concerned about barriers that impede or prevent access to

11a

quality health services, including abortion. The purpose of

the NBWHP is the definition, promotion, and maintenance

of health for Black women, including full reproductive rights

and the essential authority of every woman to choose when,

whether, and under what conditions she will bear children.

Because too many single family household in the

United States are headed by Black women living in poverty,

possessing fewer educational and job training opportunities,

enduring inadequate, often non-existent child care services,

subject to substandard housing conditions, and lacking access

to appropriate health services of any kind; because more

than half of all Black children are poor, bom of mothers

receiving inferior, if any, prenatal care, suffering the highest

rate of infant mortality and neonatal deaths in the Western

world; and because we lack fail-safe birth control methods,

lack adequate human sexuality education, and suffer also the

highest rate of teenage pregnancy in the Western world, we

firmly insist upon continued access to safe, legal and

affordable abortion. Restrictive abortion laws exacerbate the

12a

low socioeconomic status of women of color, and the

passage of such laws will further denigrate the dignity of

Black womanhood. The NBWHP joins this brief to voice its

opposition to laws which prevent African American women

from exercising their rights.

♦ * ♦

THE NATIONAL COALITION FOR BLACK

LESBIANS AND GAYS (NCBLG) is the oldest Black

organization in the country working to advocate and

promote the empowerment and enhancement of the lesbian

and gay community. Formally a chapter organization with

branches in Baltimore, Chicago, Detroit, New York, and

Oakland/San Francisco, the national office is located in

Washington, DC. We have over 500 members nationally

and our numbers continue to increase.

Since NCBLG began in 1979, it has been dedicated

to equal rights and civil liberties for the entire community

regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation. In spite of

the strides that have been accomplished in the last 50 years,

13a

injustices continue to be prevalent. NCBLG joins with other

concerned organizations in opposing the restrictions on

abortion services which threaten the right to reproductive

choice and access to health care for low income women and

women of color.

* * *

THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF NEGRO

WOMEN, INC. (NCNW) is a membership organization of

33 national African American’s organizations, 250

community based sections in 42 states and 65,000 individual

members. The NCNW has worked for a half century in

support of the civil and human rights of African American

women and their families. NCNW joins Planned

Parenthood in this brief in opposition to the restrictive and

burdensome requirements of the Pennsylvania statute, which

interferes with the constitutional rights of women.

* * *

THE NATIONAL EMERGENCY CIVIL

LIBERTIES COMMITTEE is a not-for-profit organization

14a

dedicated to the preservation and extension of civil liberties

and civil rights. Founded in 1951, it has brought numerous

actions in the federal courts to vindicate constitutional

rights. Through its educational work, it likewise has sought

to preserve our liberties. From time to time NECLC

submits amicus curiae briefs to the courts when it believes

issues of particular import for civil liberties are at stake.

* * *

T H E N A T I O N A L L A T IN A H E A L T H

ORGANIZATION is committed to work toward the goal of

bilingual access to quality health care, reproductive services

and the self-empowerment of Latinas. Our health and

reproductive issues have not been addressed. Lack of

awareness on the part of the medical profession and the

language barrier have had a major impact on our access to

quality reproductive services and media care. Further

restrictions and lack of access to safe and legal abortion will

jeopardize our health and our lives further. We must have

all information and services available to us so we can make

15a

knowledgeable, educated and healthful choices for ourselves.

* * *

NATIONAL MINORITY AIDS COUNCIL is a

national organization dedicated to creating a greater

response among people of color to HIV/AIDS in our

communities. The council has as its primary focus

leadership. As such we take stands on issues impacting on

minority health. Therefore, we recognize the importance of

supporting increased access to public health, and a national

focus on public health for all women.

* * *

THE NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN’S HEALTH

EDUCATION RESOURCE CENTER of Lake Andes,

South Dakota (The Resource Center) is a reservation based

organization that works with Native women in the

empowerment process involving Native women’s health,

education and reproductive rights. The Resource Center is

currently active in coalition building on the local and

national levels with Native women from diverse tribes, in an

16a

attempt to move forward policies that promote positive

lifestyles and better reproductive health for Native women.

As Native women, whose traditions have shown that

abortion has always been women’s business, determined by

women, we must support other women in their fight to have

the right to have abortion, and to make that decision within

the personal circles of women’s business.

* * *

THE NEW YORK WOMEN’S FOUNDATION is

a cross-cultural alliance of women helping women and girls.

With a membership of approximately 2000 and a board of

forty, The Foundation is committed to address the unmet

needs of low-income women in New York City through

grants and advocacy. The board of The Foundation believes

strongly that every woman has a fundamental right to full

information about her reproductive health, a fundamental

right to make an informed decision about her reproductive

health options, and a fundamental right of access to all

reproductive health services.

17a

The Foundation believes that every woman must have

access to safe, legal and affordable abortion and that the

disproportionate lack of such access in the African-

American, Latina and Asian-American communities is

particularly deplorable.

* * *

THE PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND is a national organization based in

New York City dedicated to protecting and furthering the

civil rights of Puerto Ricans and other Latinos. The Fund’s

litigation efforts focus on the areas of employment,

education, housing and voting rights, with a particular

emphasis on safeguarding the rights of Puerto Ricans of low

economic status. Puerto Rican woman and other woman of

color are particularly vulnerable to discrimination and

therefore the Fund supports efforts to protect their rights.

The Fund opposes any efforts to overturn or in any way

restrict the rights recognized in Roe v. Wade.

* * *

18a

THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER is

dedicated to protecting the legal rights of poor people and

minorities. It has served as counsel in numerous cases

raising constitutional issues of particular significance for

women, including Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677

(1973).

* * *

WOMEN FOR RACIAL AND ECONOMIC

EQUALITY is a multi-racial, multi-ethnic national

organization founded in 1977. Our members are Black,

White, Chicana, Puerto Rican, Caribbean, Asian and Native

American Women who are workers, trade unionists,

unemployed, welfare recipients, professionals, students and

senior citizens. We are women who may be especially

vulnerable to discrimination because of color, national

origin, religious beliefs or sexual preference. We are women

whose experiences have shown that racism is the major

obstacle to bettering our living conditions in any real or

meaningful way. Our program is a 12-point Women’s Bill of

19a

I

Rights which includes: the right to reproductive choice;

access to federally-funded non-racist, nonsexist sex education

and birth control, regardless of age; abortion upon demand;

and outlawing of coerced sterilization.

* * *

THE WOMEN’S POLICY GROUP (WPG), formed

in 1988, is a Georgia-based organization working to improve

the lives of women. We study and analyze issues, and work

with individuals and other groups on women’s concerns. We

are interested in a variety of issues affecting women’s family,

work, and personal lives including insurance coverage for

pap smears and mammograms, child custody, child support,

child care, family violence, Medicaid coverage for pregnant

women and infants, obstetrical malpractice, family medical

leave, universal health care coverage, sexual harassment and

reproductive choice.