Order Transferring Philadelphia School District Case

Public Court Documents

November 24, 1969

6 pages

Cite this item

-

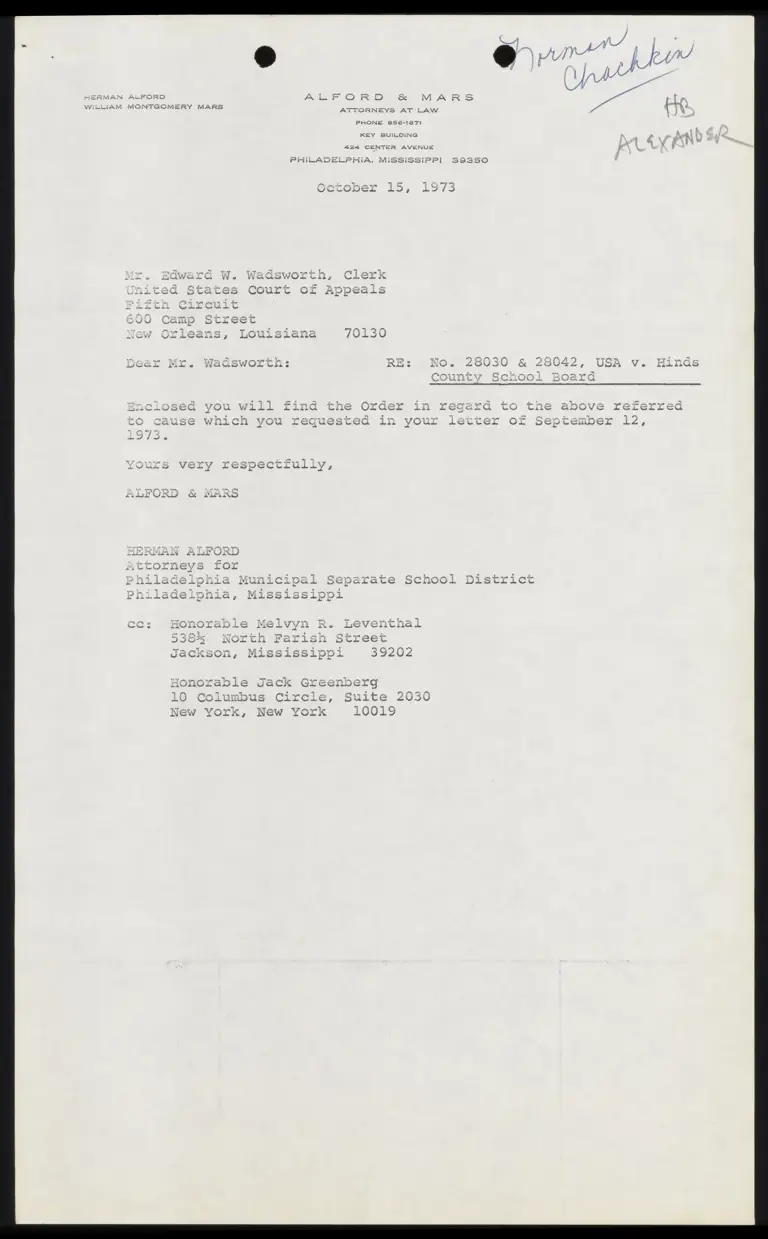

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Order Transferring Philadelphia School District Case, 1969. e051da08-d267-f011-bec2-6045bdd81421. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5dfb51d4-ae91-46d2-8263-e611ecbf558a/order-transferring-philadelphia-school-district-case. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

HERMAN ALFORD Al Eo mRD & MARS

WikLIiAM MONTGOMERY MARS

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

PHONE 656-1871

KEY BUILDING

424 CENTER AVENUE

PHILADELPHIA, MISSISSIPPI 39350

. Nl 7 aT T= ~ PHP Sa rT rl

-— aS AWGL LG Woe Wa asSwOol “id y Nr oe Wo le

CE LF TRIN CEC RE RE eb Te

eas LOW DLA CGO CV w Ul &a pd (= QI.

\ Lod em Rm am yy de

— whe de wal LS

) 77 am CS de wm

“ NJ Gal ede GC

(=

- g en TET, Wa AE NE Se RE ~-ry'i rN

WNCGW Ud A QQRIIS dd Ue DO Kad INA

ps . wa «or. - g ~ gt de Dn - ONO -~ —_

eal mx ™ Wa SwWOX ad 2 ANNA mw LW hy xX Vol v ®

FN wm =p ~ I mon TN en mA

Noh Aa = Ne a a ps <2 NAA A NA

Svs re iy ~ heeg i CL bE devas ZN AY wn pay ‘ a I LR I

ERIC LOSEC YOu Wiis Ting Lhe Urey 1n YedaXa TO The above Zeilierred ph

NATTRS Wht Al WIT rartiiactrad Tn vent OR a SE SR he ~’) Tn Bs Loy aT ae, Te me Le Py in 2 HE

nll ; WALCO YOu IXeguestelQ 1Il your letter OIL ocprcloer —d

- ‘ - - -~ + ~~

ded ALAIN SNL VINNY

doe dm Am mp fr a gn

ALWWiliiCYs 4LU4L

: = - - . _ ’ . - — . ty - 2 . . p 4 NT IN, Re PRL 39 TN yn] Canmrmatra Cha } Cr~T We

SALALQUOC LIL G MULL LAL YUL OC/dild Le OLllVU LL JLo wd -— C Ls

l i 2 1 : |)

PRniLialleiDilda, bs

CC: OONOIXal le MEelvVyl XR. Levelicliad

SIAL. AT din Them ora = C3 doe pn omy oy fe

het JT Lr NOYXrLh PFaXisn street

-— - ap tr : ¢ 3 -— eo Yate oe Xr ae 7% YP VR CR SE C

VALA DULL, MNMAoS iLoodpdy4L 39202

* mn wm pn wg em — ~ ~'Y oT di 7 rt 2 PRIA 2

MAWVIMV LAV LGC UA UA UL CCL 0 A

- - .

a) { ~ 1 wen ri 1 Cyn 4 ~ N= N

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

AV Tat ale NT XT nl : 1 C

VOX XK, NEW YOK - ind

LL mo

he dd i BN UNITED OLA L LD CO URT A

iy

LER} Ll Re

UNITED oLoaALAS UD

~~ ry AT TITY TY

Sara la\l \&L

Ep———. “pp 1 pe a NNT TAT

CVU LL

\ FT AAT

LUCA Ll LUN

—— ~

BOE ANG) ND hdd NLD

NITED Saal hs Ul

vr

\/ &

V &

FOR ——— "pn fp — Tren presp— - ~~ TITY NT rp > 12 ADELPETA MUNIC mw

dds he ahi hd dnd dd dh de dn A HUNIL\CA AL ddd ARATE

CO ATTAAT TNT OMT TA i AT

olLROOL: DisTRICY, 1 AL

PLAINTIFF-APD

ddd Ae dN A de de A

NTN NTS

Sil ENDANTS

DTATNTTD

Xr LAINTIE

XP dp) "IINDA a AN

HOD 9°

WAN Ea AN

: - ’ f - i . : . ry ~ TE I ~~ . a ~~ ~ = ~~ pa Nm ws wn dm =

ZUursuant (SA CLIC WCC LO LVEL VA Cia SUpX eme CouYyc i

; r~ 1 rims dey TD 3 19 ~ O 2ACfy TY c

Ve wh eA ALLELE GY i») ? «J bh ~ AO Ue oe

EC 24 T TIA ) A 1 9 lh c nt veo 3 = Nl 2 i .

“ Jy L*T ddeluhe Ld LJ, Alo LUML LC Lido LCLAddliCll JUL aol Cu

i YI re RA,

(Fw) OER OSE

to Ths

agg {S OL

C9 mam, mA vm ~

dd

=

wi -API

Por § olf of |

— a y | NTF

ded dedi dN 4

P

yi) ANID

~ ELLA AN 4

~~ we -~ ~ rn Fo bm \¥4 be = FS ym wi +h Oo

lowing or Ire entereG by Cll Oo LOUOUL CU WA Lil -

HER Je ns EC Nn Bene Pe SN UE TI Ne

idl LGA A WAllLO MUlllied pad ade DLL Lan o i

{7 \ rq " ~ AN Save Or

LL) V. Hinds (OUINCY SC

mun 77 10A0 A231 IA 1264 { Fim mdm RET TS TS Shand

November i -— DA ul Lo oe & 4d mie leet NJ (EPP A didi Cd Ja A we Wed ANI

I vi : . y - } - 2 . Tis = - - ~ mm ow gun | em wa - No ml Wen lo] - Pa 3 oo R= am ~ dm pm wm - en

(44d o Al LACULGL VLLUCL LCalliTo ald doo allG canton -—

Wri iii WL00 States

mo ADDRTTER

'S=-APP SUBNET LY J)

m

-~d

19 CH iQ ‘ry

di yg ANS

= NS ~F d=

“Uda OU 4 “ili

AE avon evi

(1 = QAil

fe += no +1

~ Add Cl, -

RT pr

Ah la SERS ACE LEIA ba |

- ru rT rE

omy go

wih

NP a) ERB SEAL REXHBLBS EA COOLERS XBL A

LL Mae pi .

— TEE qT 8 = i 3 ° - or bm = - de 1a “am PRT Be ag ono o

SClil-allllal STATUS

- . .

- Nm -

L 3 . Ee " i TL LT, ve ELL EE

COO gn an lnc. Ul Liddy

A “Lon, £ bi - -y

VeTlUORL Lo, De

de FS A" a —~ ~~ wer 4 boy = dw lea DY “1 aA on Tv yt = RATT YS ~~ v ] CY mv = oo = de

hn nov appeax -—adly wad Lil JdlLdlclUC a siiaa Municipal woppaLa [OR =)

| ve ree vaya d= In

LIAaAnCo With

7.3% Pus a rd ro Tw ni iin ps aa 2QANWN oc DQANAD " : Se

\ =~) ATRL Lamia dt eicdSNtil (Ul. INS.» LU SY xX LOU 4L, Uni ted Sea tes 6

A YS 28% 0 15] syd py ded ER A vy de ’ AA sma on EI

SeniC ll hl LF dud ddd edd de ppellant 7 Municirc pad wGAdLA LO iL

TU A dom mgd on om am Tam v2 ~~ - bo om mm Yo iv4 a a= ko N=

DCN lL Lista “2 Ade gy Derendcdancs=- SHC LALCTO “4 MT LCV Ld QAO -

of oo, a en my d= a TTrme =a al To. TN By ode FR £5 pm, 8 wr en Lo d= Tu 11 += Jn Sv vn

-— de de SA (Re tae Vidi. Loa - Ca Ces Dist Nr CT VL a UA ilo Sou [SP FR er

™- de a - . po fon

DAS LL 100 Vi

fF ~ \ - o- 1 .

2 ne ~f+ +hat

\<) w QA 2 I “iid ©

ig ES, PP EE ER OR v ArTSETYSA EAT cers ry ha

LUVUWL EL wl CCL LW WC - GUMCLICW LVL boul Wise LILAC

of on ~ Lo -— rt Gee 7 o om de mw oF ~~ CV NY

applica ELON OF any pal - Y (OF 8 inter cvenoxr, or SRONLSS

£m il Pn 7 DEA ee Zn tnd Coy ‘pve ow Yyme YT Tu rn

‘a, -— ha <a Ox sald oxragers Cli tered ddd oO cour | 9 AACA Ad WC

~~ ~~ ton o ~~ ales I= areal ac 1e ~+= and are to be made the

CUI LUCL CU ab the mancatce CTR WHE dourt dill dL LLU DC Hilde Liic

Y PROS fp £7 mye

v. Hinds County

~~ ~~ | T02)

ana J1luda) which are

TY Av Vo

Vi S Uda X

™ EOE ok

filed with the Department of

. - a’ 4

= taneously witn mA WAMU A LRAAICVG IO A hd

. : ~ 1. Kk] % n ~ em dem om a of pan ge fn vu og fo ~NYY I co Jp

racalnel a Jd. rie QlsStTict OCUl -— Sd

. . . . a To A AWA mye wm mgr ee ITY mA

eXamina C10 neyeln ae Qi 0 gh Coe

; —— —- 7 d= oy man om fe ~ Vv ~ ro dow T a ome dee bm ~, TITNAT orn = eo de 1m ~ Ph LT an mS = my de Va lalalel.

Sao Ql da lLiidd ed VT a | LiadS DOW LC UVAL Woy Lid UC LCalldiilL Oo ClilVU dL

gy ' : — A Ala adnan mde es ATE a aE aE ER ETE re iy Corvnty tune

CA de nw? de de Ne 0 Ae V Se ldiai vw andd WG J L WN 8 ie oe ob ed ead “J fod

\

- - 5 n . 9 le vy - 5 ~y fo ~ _ on am wy ~— mo cn nm pn de LR LE PA ovember 1.5 do

Mule Wald Gul CaldiillUG lh VAG O Ao MVLE Ad LCL Lilies NU VCUILWGL wr (SR

fi wp ov 4 at ve AY gle nT 2 yr YT rg a

wel =U [=] dl Vero d he Vo A

TOTO OA ADT TID TI IE Pl Ee Romer VE Orin 1Q 73

de dead wm WSN LING Cad Wail Lay VL UL Luca, med fw

———

Vind 4

rer im 7 NTH

VAL Ula h

om 5

F i bx "47 ri

A BERG PLE IN Tn

he

| FIST - TQ TTI TS

WIN LIL ed AEE SR EFP LG Fuh

-— me Pa 8 bade] Be hte pe hm NT INTO ~ NTS ~ - a

\ —~ is . { ) ye 7 ~ C

-—— oh hd AN de a add Pa EE Neha SA FL el nT 0 Wf

Ny pT gam ie - pn my pe op mm pm

- NN hdd TEN a CL WT I Wl

INCI rw on LOVIN OX LON L

TT ET ~~ CA FT Py AY A Rs ba

\ + 3 A A y, ii ) " a

LN PSS SE wr EL SS a Can add he Nl" -— dr at a whe he a Sak & had chad ds Bn de® he

—

Vie

NY TI WTS TAT YY TTT A ITNT CC TDAT bre SN rT

ST 1 SU has aa ANd dl SA PP I GF vl ap WF Wap Nt Se 6h

~~ ~~ —- —- “NE y J —- TNE D NTC rT i TLE

bo 4 0% LO LO 5 BEEN WIR Be UE I LT 7 Ce Gay oe et hd SNDANLDLS a hte dn Add chk deed ded od

~ -" ~X TO ~, owe, ~~

TNE Sao0Ve STV. sana nunoered Cause Cane On “IS

rd u-ocn the not og oe ey FanAnrto E41 Tar vi1vaiy amie Je

e YO E08 MOCLon OL Lhe BeTenaents Tile pDUursualll “

x ~ wh ~ ON ~~ a a Ta Ye dn ~~ “Ln x 3 0. TR Ph ~~ a WN ren - - “vm we 8 “

de Cae _— a Vio - - Lv edie l WW Ar hah WL a a J Letencantc -~ 4

~ - ~ i; y a ay p— he Tom an Ne a 1 ~ 3 "I~ V4 Cm, ~~ Ny mm

[EPL WV Apa ee 4 2 o_o (SN contrary ence PO / | SP S| Wa ag (

-t

~ yal) - AT Ya) A = a ~~ — Tnx Sp, 2

Noenner \ OF -— NIA — NCW Ve a Sli0 ded HiStalla,; oY which

- “i . =m " No - et al a he he ad oo, ~" - ~~ PPR Ja ta 7. ¥ - ~~ - — 1 - - ~~~

MOTION The perencalils Soh Col/'La li: CllGiay —— “id WhQis LL C™

-— 4 es FEF ~ ys olin yy ~ tan ey fk yy he | rons iF

Je 8lnD —aa ls TLL od zCGUCe Caldas, Lepal “iilCaawe UVa JCC Lang

~~ - -

dm on mm — am PN PE FN mm md ~ mm nm ma

ToLucation and welrare and which Rls LOoUITC DIdereael LAL

A ~ - oh Py | ~ ol. ~~ ~ Ry Bn ) C

el reCe ~ Y -— ed crdex owe Novemnoer / ; we of \J

7 af dh me TY oy 23 oe en ig | Ta NASTY ES TY TET fo} Soy orale

ALTer ad A he ral Gade CULAiw dl C am edly “id Cour [S

J. A SI LI eA de 7 ay ole oe Poioy

PIES TP PL WR” asl waa AMV LALVae we wa SSTas Qld “hill = POR =

. 3 yp oh a gt 2d

ae JO Sa J WAL SS EP EL trl NG

En rah \ -—L — h- gm

edd UID LS AND DECREED “ialh (SPP =

sy pm ps groysamens. gi shy Wf wal on re a “a haoaranht Sv ml me mem T TT ALC

Lava CllC.. tioned MamGia Ui lle le w 1S NIelelyV alieliCe ad LU LLWD

-

CO my, .

Jt i om, Im wil "oT SYR 58TVVE y; Alby

whe Fig N1IiaGC LY riia Deke CAC LL eA he | = Sa a,

I Rp. vi oo Pe Pa i BS a CE ed a i PA dela OAT Tal”RalTAak - = BD ,

Sougencts ——-- br diet a wh ER \ ——- “ede J dark de GAC WL Jaa aad Ae oa

: o mn dee Com TN Hm my omy

7 CA wo J AdLlUL CO Ned NJ ned wn nd Ct hs ha oe he @

- -—

J ~~ N -— . -~ ——

a @ "1 Selve CA che whe SNC Een vS

: crades 7 8 Re ee Tr i SG, GIR ER Ay nn] 3 on

——e Aas LLCO whe fou who th sh Rp Eh a dE Munioi ras Ca A -

Sr ad ~~~

[SUPER NR WY oo Nee a ANAS LI SB I A NF BES

-~

. -

- . . i

v ect AMMEN ~~

civ ed amd 2

~~»

Aodhan

Se

oo Ass 2 Chadian CA de

ps Tn IT OwWwe -

Co od de AJ JAY Oe

~~

Ra rah 5 y ATARI NTT OO wT (NTN

Veil a ad ay dala & oN NY a ds ks a dod 8 ln

ou Tm vy] S ~ RP 2 -

ag SO SE Sa at

- . \ AA AT =D YN

LLC li eG a Y -

Wn NSP

a v, vo Vi Dd “of

— ha

Lr nt bod eo Pw /O

Lr

=

/

La | ~Tenlan

Pugin) SET SN oS NPL Ne dn dn ne Ce

veld o

~~ ~ , ~~ -~ ~~ mi

Crt ~~

A NCL 2.7 - =< LLC

a Eb wo CLIVUV A

Ode C/O Pa de sw/O

maa nO

IOC AL Odds

mia OYooer Btn ~~ YNIYYT OMY T oe 2 ~~ NAvZemner 7 a ou a

. LidS Va lCa COl1lS LUUL LW Cll Vad WNW VCUU/ Ca J od J

2 ens VIVA « $= ~ PYX 7 Xml ry

—-— a dale CHLOE “Leo JL OVLUCK LV

Alo UIT) LSadNhdd JOLLY Vad — m— m STYTN A WTI y— ee han re

day of November, 47

~TN SNT TTT —— pm

CLALUVLL VvUUITL

v

~— NTY TT ee Te on

(OUI CUPL WJ Sa 8 WUT

~~, ATT TN NT i

LP a WU UANT -

SYA