Whitfield v. Clinton Appendix to the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1988 - April 10, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Whitfield v. Clinton Appendix to the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1988. 6dda130b-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5e6561f9-aa81-4cd5-8b42-eb59e0f4ec16/whitfield-v-clinton-appendix-to-the-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

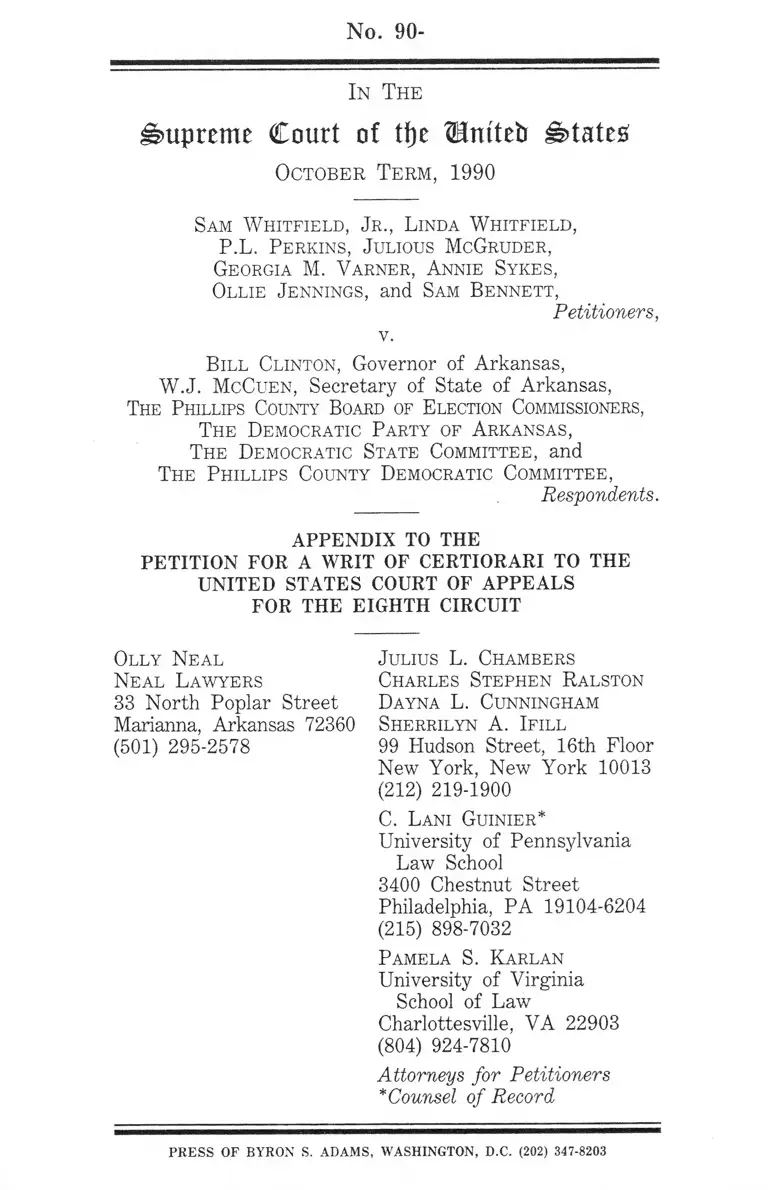

No. 90-

In The

Supreme Court of tf)e ^Hniteb H>tate£

October Term, 1990

Sam Whitfield, J r ., L inda Whitfield ,

P.L. Perkins, J ulious McGruder,

Georgia M. Varner, Annie Sykes,

Ollie J ennings, and Sam Bennett,

Petitioners,

v.

Bill Clinton, Governor of Arkansas,

W.J. McCuen, Secretary of State of Arkansas,

The Phillips County Board of Election Commissioners,

The Democratic Party of Arkansas,

The Democratic State Committee, and

The P hillips County Democratic Committee,

Respondents.

APPENDIX TO THE

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Olly Neal

Neal Lawyers

33 North Poplar Street

Marianna, Arkansas 72360

(501) 295-2578

J ulius L. Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Dayna L. Cunningham

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

C. Lani Guinier*

University of Pennsylvania

Law School

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104-6204

(215) 898-7032

P amela S. Karlan

University of Virginia

School of Lawr

Charlottesville, VA 22903

(804) 924-7810

Attorneys for Petitioners

*Counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EIGHTH CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS’

OPINION UPON REHEARING EN BANC la

EIGHTH CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS’

PANEL OPINION 3a

MEMORANDUM OPINION OF THE DISTRICT

COURT DISMISSING PETITIONERS’

CHALLENGE TO THE PRIMARY

RUNOFF STATUTE 58a

ORDER DISMISSING THE GOVERNOR AND

SECRETARY OF STATE AS

DEFENDANTS 132a

RELEVANT PORTIONS OF THE DISTRICT

COURT’S ORAL RULINGS 135a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF

ARKANSAS EASTERN DIVISION

TELEPHONE CONFERENCE 145a

COURT OF APPEALS’ OPINION UPON

REHEARING EN BANC

Sam Whitfield, Jr., Linda Whitfield, P.L. Perkins, Julious

McGruder, Georgia M. Varner, Annie Sykes, Ollie Jennings,

and Sam Bennett, Appellants.

v.

The Democratic Party of the State of Arkansas, the State of

Arkansas Democratic Central Committee, the Phillips County

Democratic Central Committee, and the Phillips County

Republican Party Committee, Appellees.

No. 88-1953.

United States Court of Appeals,

Eighth Circuit.

Submitted April 10, 1990.

Decided May 4, 1990.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Arkansas; G. Thomas Eisele, District

Judge.

Carol Lani Guinier, Philadelphia, Pa., for appellants.

Tim Humphries, Little Rock, Ark., for appellees.

Before LAY, Chief Judge, BRIGHT, Senior Circuit

Judge, MCMILLIAN, ARNOLD, JOHN R. GIBSON,

- 2a -

FAGG, BOWMAN, WOLLMAN, MAGILL and BEAM,

Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM.

In this matter, a panel of this court, Judge Bright,

dissenting, reversed the Judgment of the district court.

Whitfield v. The Democratic Party. 890 F.2d 1423 (8th Cir.

1989). After rehearing en banc, the judgment is now

affirmed by an equally divided court. Judges Bright, Arnold,

Bowman, Wollman and Magill vote to affirm the district

court. Chief Judge Lay and Judges McMillian, John R.

Gibson, Fagg and Beam would reverse. The Clerk of the

Court is directed to issue the mandate forthwith.

- 3a -

COURT OF APPEALS’ PANEL OPINION

Sam Whitfield, Jr., Linda Whitfield, P.L. Perkins, Julious

McGruder, Georgia M. Varner, Annie Sykes, Ollie Jennings,

and Sam Bennett, Appellants.

v.

The Democratic Party of the State of Arkansas, the State of

Arkansas Democratic Central Committee, the Phillips County

Democratic Central Committee, and the Phillips County

Republican Party Committee, Appellees.

No. 88-1953.

United States Court of Appeals,

Eighth Circuit.

Submitted June 14, 1989.

Decided Dec. 7, 1989.

Carol Lani Guinier, Philadelphia, Pa., for appellants.

Tim Humphries, Little Rock, Ark., for appellees.

Before BEAM, Circuit Judge, BRIGHT, Senior Circuit

Judge and HANSON,* District Judge.

The HONORABLE WILLIAM C. HANSON, Senior

United States District Judge for the Northern District of Iowa,

sitting by designation.

- 4a -

BEAM, Circuit Judge.

Whitfield and other appellants, black voters in Phillips

County, Arkansas, challenge the district court’s dismissal of

their complaint. Whitfield sued the Democratic Party of

Arkansas and others, alleging that a state statute which

requires a general (runoff) primary election if one candidate

does not receive a majority of the vote is both unconstitutional

and in violation of section 2 et seq. of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 et seq. (1982). We affirm in part

and reverse in part.

I. BACKGROUND

A. Facts

The population of Arkansas is approximately 16.3

percent black. Approximately 47 of the 75 counties in

Arkansas have black populations below this statewide

percentage, and twenty-one counties are less than one percent

black. Twenty-two counties have a black population over

- 5a -

twenty-five percent.

The state has a history of official discrimination in its

electoral process. Arkansas has used racially discriminatory

voting practices such as statutory restrictions on the rights of

blacks to vote, discriminatory literacy tests, poll taxes, a

"whites only" Democratic primary, segregated polling places,

and at-large elections. Perkins v. City of West Helena.

Arkansas. 675 F.2d 201, 211 (8th Cir.), aff’d mem.. 459

U.S. 801, 103 S.Ct. 33, 74 L.Ed.2d 47 (1982). See also

Smith v. Clinton. 687 F. Supp. 1310, 1317 (E.D. Ark.)

(taking judicial notice of the history of electoral racial

discrimination in Arkansas), affd mem.. ___U .S .___ , 109

S.Ct. 548, 102 L.Ed.2d 576 (1988).

The focus here is not only on the State of Arkansas,

but also on Phillips County. While over fifty percent of the

residents of Phillips County are black, black residents of legal

- 6a -

voting age number less than fifty percent.1 Statistics on

education and income, indicators closely correlated with

political participation, see Perkins. 675 F.2d at 211, reveal

that blacks in Phillips County are on the average much less

educated and far poorer than whites.

No black candidate has been nominated for or elected

to a county-wide or city-wide office or to a state legislative

position from Phillips County since the turn of the century.

In the past two years, four black candidates have come in

first in preferential primary elections in Phillips County, yet

all four were subsequently unable to obtain the Democratic

nomination because they were defeated by white candidates in

general (runoff) primaries. 1

1 According to the 1980 census, Phillips County had

34,772 residents. Of these, 16,100 (46.30%) were white and

18,410 (52.94%) were black. However, of the 22,110

residents age 18 and over 11,542 (52.20%) were white and

10,395 (47.00%) were black. Earlier census figures show

that these percentages are generally stable. Exhibit JX1 at 1-

3, Whitfield v. Democratic Party. 686 F. Supp. 1365 (E.D.

Ark. 1988).

- 7a -

Racially polarized (bloc) voting is the norm in Phillips

County. Whitfield’s expert, who performed both extreme

case analyses and bivariate ecological regression analyses on

the fifteen county-wide, city-wide, and state legislative

elections since 1984, testified that in all fifteen elections,

voting was racially polarized as shown by the fact that black

candidates were supported by an average of over ninety-four

percent of black voters and, in most county-wide races,

virtually no white voters supported black candidates.

B. The Primary Election Runoff Requirement

The Arkansas Code sets forth the procedures for

primary elections, Ark. Code Ann. §§ 7-7-201 to -311

(1987), pursuant to amendment 29 of the Arkansas

Constitution. Amendment 29 states:

Only the names of candidates for office

nominated by an organized political party at a

convention of delegates, or bv a majority of all the

votes cast for candidates for the office in a primary

election, or by petition of electors as provided by law,

shall be placed on the ballots in any election.

- 8a -

Ark. Const, amend. 29, § 5 (emphasis added).

Whitfield is challenging section 7-7-202, which states:

(a) Whenever any political party shall, by

primary election, select party nominees as candidates

at any general election for any United States, state,

district, county, township, or municipal office, the

party shall hold a preferential primary election and a

general primary election on the respective dates

provided in § 7-7-203(a) and (b).

(b) A General primary election shall not be

held if there are no races where three (3) or more

candidates qualify for the same office or position as

provided in subsection (c) of this section, unless a

general primary election is necessary to break a tie

vote for the same office or position at the preferential

primary.

(c) If there are no races where three (3) or

more candidates qualify for the same office or

position, only the preferential primary election shall be

held. If all nominations have been determined at the

preferential primary election, or by withdrawal of

candidates as provided in § 7-7-304(a) and (b), the

general primary election shall not be held.

Ark. Code Ann. § 7-7-202 (1987).

Under the current system, candidates for a particular

party nomination run in preferential party primary elections.

If three or more candidates run in the preferential primary,

- 9a -

and none receives a majority of the votes, the top two

candidates are required to run in a subsequent general (runoff)

primary election. Both appellants and appellees acknowledge

that, in Arkansas, the Democratic nomination is tantamount

to election for most local and state offices.

C. The District Court Holding

The district court dismissed Whitfield’s constitutional

challenge to section 7-7-202 because the court found no

racially discriminatory purpose or intent underlying the

primary runoff enactments. The Court also rejected

Whitfield’s argument that the runoff had been maintained for

racially discriminatory purposes. Whitfield. 686 F. Supp. at

1370.

The district court denied relief under the Voting Rights

Act, stating that the plaintiffs failed to convince the court that

section 2 applies to runoff provisions such as those found in

section 7-7-202, given the demographics of the area and the

manner in which the runoffs operate. The court also

- 10a -

concluded that, even if section 2 does apply, the plaintiffs

failed to sustain their burden of proof that section 7-7-202

results in blacks having less opportunity than whites to

participate in the political process or to elect candidates of

their choice. Id. at 1387.

II. DISCUSSION

A. Constitutional Violation

Whitfield argues that section 7-7-202 was enacted and

has been maintained with discriminatory intent and thus

violates the Equal Protection Clause of the fourteenth

amendment. "[I]n order for the Equal Protection Clause to

be violated, ’the invidious quality of a law claimed to be

racially discriminatory must ultimately be traced to a racially

discriminatory purpose.’" Rogers v. Lodge. 458 U.S. 613,

617, 102 S.Ct. 3272, 3275, 73 L.Ed.2d 1012 (1982) (quoting

Washington v. Davis. 426 U.S. 229, 240, 96 S.Ct. 2040,

2048, 48 L.Ed.2d 597 (1976)). "The ultimate issue in a case

alleging unconstitutional dilution of the votes of a racial group

- 11a -

is whether the [voting scheme] under attack exists because it

was intended to diminish or dilute the political efficacy of that

group." Rogers. 458 U.S. at 621, 102 S.Ct. at 3277-78

(quoting Nevett v. Sides. 571 F.2d 209, 226 (5th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied. 446 U.S. 951, 100 S.Ct. 2916, 64 L.Ed. 2d 807

(1980)).

A plaintiff challenging the constitutionality of a

discriminatory electoral system must prove, by a

preponderance of the evidence, that the defendant had racially

motivated discriminatory intent in enacting or maintaining a

voting practice. Perkins. 675 F.2d at 207; Nevett. 571 F.2d

at 219. See also City of Carrollton Branch of the NAACP v.

Stallings. 829 F.2d 1547, 1549 (11th Cir. 1987), cert denied

sub nom. Duncan v. City of Carrollton. Georgia. Branch of

the NAACP. ___U .S .___ , 108 S.Ct. 1111, 99 L.Ed.2d 272

(1988); Weslev v, Collins. 791 F.2d 1255, 1262 (6th Cir.

1986) (citations omitted). The trial court must consider "the

totality of the circumstances" surrounding the alleged

- 12a -

discriminatory practice in order to "determine whether the

[challenged voting practice] was created or maintained to

accord the members of the allegedly injured group less

opportunity than other voters to participate meaningfully in

the political process and elect [candidates] of their choice."

Perkins, 675 F.2d at 209. "Because a finding of intentional

discrimination is a finding of fact, the standard governing

appellate review of a district court’s finding of discrimination

is [the clearly erroneous standard]." Anderson v. Bessemer

Gty, 470 U.S. 564, 573, 105 S.Ct. 1504, 1511, 84 L.Ed.2d

518 (1985).

Whitfield provided the following evidence of racially

discriminatory purpose. First, in 1939, at the time the

primary runoff statute was adopted in its original form,

Arkansas was a one-party state and the Democratic white

primary was the only election that mattered. At the same

time, an amendment to repeal a poll tax, which effectively

disenfranchised blacks, failed. Second, after the white

- 13a -

primary was held unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in

the 1940s, the majority runoff system was retained to

diminish black electoral influence. Third, the recodification

of the Election Code in 1969 maintained the use of runoffs in

primary elections. Fourth, in 1975 and 1983, attempts were

made to also impose general election runoffs in response to

the presence of black candidates in multi-candidate municipal

contests. Finally, the current version of the statute was

passed in 1983; two members of the legislature who served

that year testified that the statute was intended to prevent

blacks from winning further elections due to splits in the

white community .

Based on a detailed review of the evidence surrounding

the enactment of section 7-7-202 and the adoption of

amendment 29 of the Arkansas Constitution, the district court

held that Whitfield failed to establish his constitutional

challenge to the Arkansas primary runoff requirement.

Whitfield. 686 F. Supp. at 1374. The court noted that the

- 14a -

majority vote requirement set forth in the state constitution

was initiated through petitions (not by the legislature) and

adopted by a vote of the people of the State of Arkansas at a

time when blacks in Arkansas could not vote in the

Democratic primary. The requirement could not have been

maintained by the General Assembly with discriminatory

intent because nothing in the record indicates that the

legislature had the power to repeal amendment 29. In fact,

in 1940, the Arkansas legislature proposed an amendment to

repeal amendment 29, but that effort was soundly defeated by

the popular vote. Id. at 1371. The court determined that

"the issue is beyond direct legislative reach" and thus

concluded that the actual purpose behind the enactment of

section 7-7-202 was the stated purpose "to insure that no one

was nominated as a candidate of the Democratic Party who

had not received a majority of the votes cast." Id. at 1370-

71.

We agree that discriminatory legislative intent has not

- 15a -

been adequately established, given the time frame and

political background of amendment 29. While the legislators

may have enacted more recent statutes which continue to

advocate primary runoffs, they were mandated to continue the

use of runoffs by the state constitution and voter tendencies

present in Arkansas. The district court’s conclusion that

discriminatory intent was not proved is not clearly erroneous.

Thus, we affirm that portion of the district court opinion.

B. Violation of the Voting Rights Act

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act provides:

Denial or abridgement of right to vote on account of

race or color through voting qualifications or

prerequisites; establishment of violation

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite

to voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any State or political

subdivision in a manner which results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United

- 16a -

States to vote on account of race or color, * * * as

provided in subsection (b) of this section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section

is established if, based on the totality of the

circumstances, it is shown that the political processes

leading to nomination or election in the State or

political subdivision are not equally open to

participation by members of a class of citizens

protected by subsection (a) of this section in that its

members have less opportunity than other members of

the electorate to participate in the political process and

to elect representatives of their choice. The extent to

which members of a protected class have been elected

to office in the State or political subdivision is one

circumstance which may be considered: Provided, that

nothing in this section establishes a right to have

members of a protected class elected in numbers equal

to their proportion in the population.

- 17a -

42 U.S.C. § 1973 (1982).

1. Applicability of the Act

The Democratic Party urges us to affirm the district

court’s holding that section 2 of the Voting Rights Act does

not apply to section 7-7-202. The Party notes that virtually

all of the cases decided under section 2 deal with at-large

elections or legislative districting matters. We conclude,

however, that section 2 was not meant to apply only to cases

challenging at-large election schemes and districting matters,

although it is true that most of the previous section 2 cases

concern these types of discriminatory voting practices.

The Senate Report emphasizes that section 2 is the

"major statutory prohibition of ah voting rights

discrimination," prohibiting practices which "result in the

denial of equal access to any phase of the electoral process

for minority group members." S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess. 30 reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin.

News 177, 207 (emphasis added). Nowhere in the language

- 18a -

of the statute did Congress limit the application of section 2

cases to those involving at-large elections or redistricting; in

fact, the Senate Report specifically identifies "majority runoffs

[which] prevent victories under a prior plurality system" as a

"dilution scheme^ * * * employed to cancel the impact of the

* * * black vote." Id. at 6, 1982 U.S. Code Cong. &

Admin. News at 1983.2

The district court stressed that majority rule is one of

the underlying concepts of our democratic system. However,

we agree with the Fifth Circuit that "[t]he fact that majority

vote requirements may be commonplace does not alter the fact

that Congress clearly did conclude that such provisions could

serve to * * * dilute the voting strength of minorities."

2 We recognize that this language in the Senate Report

refers, in part, to section 5 of the Act which section deals

with "preclearance" of changes in election laws in certain

jurisdictions. Nonetheless, we believe this legislative

discussion, which encompasses both special practices and

general prohibitions clearly supports our analysis of

congressional intent on the scope of section 2 of the Act.

- 19a -

Westwego Citizens for Better Government v. City of

Westwego. 872 F.2d 1201, 1212 (5th Cir. 1989) (citing

Thornburg v. Gingles. 478 U.S. 30, 56, 106 S.Ct. 2752,

2769, 92 L.Ed.2d 25 (1986)).

Furthermore, the Supreme Court has explicitly stated

that "[sjubsection 2(a) prohibits all States and political

subdivisions from imposing any voting qualifications or

prerequisites to voting, or any standards, practices, or

procedures which result in the denial or abridgement of the

right to vote of any citizen who is a member of a protected

class of racial and language minorities." Gingles. 478 U.S.

at 43, 106 S.Ct. at 2762 (emphasis in original). The Court

has specifically recognized majority vote requirements as

"potentially dilutive electoral devices." Id. at 56, 106 S.Ct.

at 2769. Here, that potential has been realized.

The district court held, "as a matter of law, that the

undisputed population figures here are not such as will permit

the plaintiffs to challenge the primary runoff law of the state

- 20a -

of Arkansas as a violation of Section 2 of the 1965 Voting

Rights Act, as amended." Whitfield. 686 F. Supp. at 1381.

The court based this premise on "the circumstance that the

voting age populations of blacks and whites in Phillips County

is equal for practical purposes." Id. The court rejected the

idea that "even where black voting populations equal or

exceed white voting populations, blacks should nevertheless

be considered a ’minority’ because of the evidence that they

have not participated in the past in the political processes of

the county in as large a proportion as have whites." Id.

We disagree with the district court’s analysis of this

issue. The inquiry does not stop with bare statistics. Section

2 is not restricted to numerical minorities but is violated

whenever the voting strength of a traditionally disadvantaged

racial group is diluted. " [Historically disadvantaged

minorities require more than a simple majority in a voting

district in order to have * * * a practical opportunity to elect

candidates of their choice." Smith v, Clinton. 687 F. Supp.

- 21a -

1361, 1362 (E.D. Ark.), affd mem.. __ U.S. ____, 109

S.Ct. 548, 102 L.Ed.2d 576 (1988). We conclude, as a

matter of law, that a numerical analysis of the voting age

population in a particular geographic area does not

automatically preclude application of section 2 to a challenged

voting practice used in that area.

Furthermore, the parties stipulated to census figures

showing that blacks do constitute a minority of the voting age

population in Phillips County (47%). In addition, at every

election studied by Whitfield’s expert, blacks turned out at a

lower rate than whites. Thus, although theoretically a black

candidate may be able to muster a majority of the votes in

Phillips County, the practical reality is that there simply are

not enough blacks voting in each election to allow a victory

for a black candidate.

While the district court believes that the registration

level of voting age blacks is equal, or nearly equal, to that of

voting age whites in some of the challenged geographic areas,

- 22a -

we find that conclusion to be speculative. Whitfield points

out that the census data in the record contains no references

whatsoever to registration rates, and indeed, Arkansas

apparently does not keep such data by race. Appellants’ Brief

at 12 n. 12. The district court also supports its conclusion by

relying on the fact that efforts to register blacks have greatly

increased in recent years and black citizens no longer face

harassment and intimidation in registering and voting.

However, if we were also permitted to speculate, we would

probably conclude that even with these changes in Arkansas

politics, the voting statistics show that black registration

numbers are still significantly lower than white voter levels.

Blacks could not vote at all in the State of Arkansas until

1940, and as such blacks have had less than fifty years to

increase their voter numbers. Their registration level could

hardly be equal to that of the white community, which has

been able to recruit and assemble voters since the creation of

the state.

- 23a -

2. Discriminatory Results

The district court also concluded that, even if section

2 did apply to majority runoff requirements in Phillips

County, Whitfield failed to prove that, based on a totality of

the evidence, section 7-7-202 results in discrimination against

blacks in Phillips County. We disagree.

Although the district court apparently recognized that

"plaintiffs need not show "that the challenged voting practice

or procedure was the product of purposeful discrimination,"

Whitfield. 686 F. Supp. at 1374, we believe the court failed

to properly analyze the runoff requirement in light of the

results-oriented test articulated in the Senate Report. Rather,

it appears that the district court made a combined analysis of

the discriminatory intent underlying section 7-7-202 and the

cause and effect relationship between the runoff requirement

and election results in Phillips County. This analysis

circumvents the true issue: whether the challenged voting

practice, a primary election runoff requirement, results in

- 24a -

blacks in Phillips County having less of an opportunity to

participate in the political process and elect representatives of

their choice.

Throughout the legislative history of the 1982

amendment to section 2, Congress emphasizes that a violation

of this portion of the voting Rights Act may be ascertained

through a results-oriented analysis. The Senate Report states

that one of the objectives of the 1982 amendment was "to

amend the language of Section 2 in order to clearly establish

the standards intended by Congress for proving a violation of

that section." S. Rep. No. 417 at 2, 1982 U.S. Code Cong.

& Admin. News at 178. The Report then elaborates on this

stated purpose:

This amendment is designed to make clear that proof

of discriminatory intent is not required to establish a

violation of Section 2. * * * The amendment also

adds a new subsection to Section 2 which delineates

the legal standards under the results test * * *.

- 25a -

This new subsection provides that the issue to

be decided under the results test is whether the

political processes are equally open to minority voters,

Id. at 2, 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News at 179.

The Report reiterates that the legal standard set forth by the

amendment to section 2 does not require proof of

discriminatory purpose and thus a minority plaintiff may

establish a section 2 violation by showing that the challenged

electoral practice results in denial of equal access to the

political process. Id. at 15-17, 27, 1982 U.S. Code Cong. &

Admin. News at 192-94, 205.

The Supreme Court has recognized Congress’s intent

to establish a results test, stating:

The Senate Report which accompanied the 1982

amendments elaborates on the nature of § 2 violations

and on the proof required to establish these violations.

First and foremost, the Report dispositively rejects the

position of the plurality in Mobile v. Bolden. 446 U.S.

- 26a -

55 [100 S.Ct. 1490, 64 L.Ed.2d 47] (1980), which

required proof that the contested electoral practice or

mechanism was adopted or maintained with the intent

to discriminate against minority voters. The intent

test was repudiated for three principal reasons—it is

"unnecessarily divisive because it involves charges of

racism on the part of individual officials or entire

communities," it places an "inordinately difficult"

burden of proof on plaintiffs, and it "asks the wrong

question." The "right" question, as the Report

emphasizes repeatedly, is whether "as a result of the

challenged practice or structure plaintiffs do not have

an equal opportunity to participate in the political

processes and to elect candidates of their choice."

Gingles, 478 U.S. at 43-44, 106 S.Ct. at 2762-63 (quoting S.

Rep. No. 417 at 2, 15-16, 27, 28, 36) (footnotes omitted).

Based on the clear language of the Senate Report and

the Supreme Court’s subsequent verification of the results

- 27a -

test, we reject the inferences made by the district court that

Whitfield’s failure to prove discriminatory intent under section

2 results in a dismissal of his claim. While proof of intent

may be used to show a violation of section 2, S, Rep. No.

417 at 27 & n. 108, 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News

at 205, such proof is not required of a plaintiff under the

statutory language.

The Gingles Court explained that "a court must assess

the impact of the contested structure or practice on minority

electoral opportunities" on the basis of the plaintiffs proof as

to a variety of factors, as set forth in the Senate Report.

Gingles. 478 U.S. at 44-45, 106 S.Ct. at 2763-64. "Typical

factors" include (1) the extent of any history of official voting

discrimination, (2) the extent of racially polarized voting, (3)

the extent to which the state or political subdivision has used

other voting practices or procedures which may enhance the

opportunity for discrimination, (4) whether minority group

members have been denied access to the candidate slating

- 28a -

process, (5) the extent to which minority group members

suffer the effects of discrimination "in such areas as

education, employment and health, which hinder their ability

to participate effectively in the political process," (6) whether

political campaigning has been typified by racial appeals, and

(7) the extent to which minority group members have been

elected to public office. S. Rep. No. 417 at 28-29, 1982

U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News at 206-07.

The district court reviewed the evidence presented by

Whitfield as it related to the factors set forth in the Senate

Report. For five of the seven factors, the court made factual

findings which favored the conclusion that section 2 had been

violated in Phillips County. Specifically, the court found that

(1) Arkansas has a long history of racial discrimination which

has touched the rights of blacks to participate in the

democratic process; (2) Phillips County has experienced

"extreme racial polarization in voting" in recent years; (3)

other than majority vote requirements, Phillips County has not

- 29a -

used any other "discrimination-enhancing" voting practices in

the recent past; (4) no evidence was submitted on this point;

(5) Phillips County has experienced "devastating" effects of

discrimination in the areas of education, employment, and

health, because of "dire economic circumstances"; (6)

although no evidence was presented of significant, overt or

subtle racial appeals, race does play "a central role" in

Phillips County politics and has "frequently dominated over

qualifications and issues"; and (7) no black candidate has ever

been elected to county-wide or state legislative office in

Phillips County. Whitfield. 686 F. Supp. at 1383-85.

After adopting these findings, the district court

reasoned that "the Senate Report factors more logically

support proof relating to ’intent’ issues than ’cause and

effects’ issues." Id. at 1382. However, this conclusion is

contradicted by the language of the Senate Report. After

noting that plaintiffs who choose to establish a section 2

violation on the basis of intent may do so through direct or

- 30a -

indirect circumstantial evidence, the Report states, "If the

plaintiff proceeds under the ’results test,’ then the court would

assess the impact of the challenged structure or practice on

the basis of objective factors, rather than making a

determination about the motivations which lay [sic] behind its

adoption or maintenance." S. Rep. No. 417 at 27, 1982 U.S,

Code Cong. & Admin. News at 205. Contrary to the district

court’s opinion, we conclude that the factors set forth by the

Senate Report are to be used primarily as proof of a section

2 violation under the results test. See id. at 28, 1982 U.S.

Code Cong. & Admin. News at 206.

The district court also held that Whitfield did not meet

his burden of proof of showing a causal connection between

the runoff requirement and the lack of minority electoral

success. We again disagree. During the past four years, but

for the runoff primary elections, four black candidates would

have been the Democratic Party’s nominee. The court infers

that the actual cause of lack of success by black candidates

- 31a -

was the lack of motivation on the part of black voters—

apathy-and if black voters would turn out at the polls in high

numbers, their candidates would not be defeated because

forty-seven percent of the voting population is black and some

cross-over voting does occur. It seems to us, however, that

these conclusions are based on two erroneous premises: (1)

that plaintiffs must actually prove a causal link between the

lack of black electoral success and the discriminatory system

being implemented against them, and (2) as noted above, that

the Senate factors do not apply to the cause and effect

analysis.

We agree that a causal connection between the

challenged practice, as it occurs within the political climate of

the geographic area, and the diluted voting power of the

minority must be established. Here, the proof is two-fold.

First, the plaintiffs have proved that the majority vote

requirement has impaired their ability to elect a candidate

because blacks of voting age, although they are numerous in

- 32a -

Phillips County, fail to turn out at the polls in numbers

sufficient to meet a majority vote requirement. Second, the

plaintiffs have established, through proof of Senate factors,

that the political climate of Phillips County has caused the

low voter participation, because "[ojnce lower socio-economic

status of blacks has been shown, there is no need to show the

causal link of this lower status on political participation."

United States v. Dallas Countv Comm’n. 739 F.2d 1529,

1537 (11th Cir. 1984). The Senate Report states:

[D]isproportionate educational, employment, income

level and living conditions arising from past

discrimination tend to depress minority political

participation. Where these conditions are shown, and

where the level of black participation in politics is

depressed, plaintiffs need not prove any further causal

nexus between their disparate socio-economic status

and the depressed level of political participation.

S. Rep. No. 417 at 29 n. 114, 1982 U.S. Code Cong. &

Admin. News at 207 (citations omitted).

The evidence adduced, the stipulated facts, and the

district court opinion all confirm that blacks in Phillips

- 33a -

County suffer from less education, less employment, lower

income levels, and disparate living conditions as compared to

whites. Blacks also suffer from the remnants of official

discrimination in Arkansas.

[P]ast discrimination can severely impair the present-

day ability of minorities to participate on an equal

footing in the political process^] * * * may cause

blacks to register or vote in lower numbers than whites

* * * [and] may * * * lead to present socioeconomic

disadvantages, which in turn can reduce participation

and influence in political affairs.

United States v. Marengo County Comm’n. 731 F.2d 1546,

1567 (11th Cir.), appeal dismissed. 469 U.S. 976, 105 S.Ct.

375, 83 L.Ed.2d 311 (1984).

Here, the district court required an improper burden

of proof of causal relationships by holding, in effect, that the

socioeconomic factors and the effects of discrimination did

not hinder blacks’ ability to participate in any legally

significant way. See Dallas County Comm’n. 739 F.2d at

1537. "It is not necessary in any case that a minority prove

such a causal link. Inequality of access is an inference which

- 34a -

flows from the existence of economic and educational

inequalities." M. (citations omitted). See also Marengo

County Comm’n. 731 F.2d at 1569 (holding that "when there

is clear evidence of present socioeconomic or political

disadvantage resulting from past discrimination, * * * the

burden is not on the plaintiffs to prove that this disadvantage

is causing reduced political participation, but rather is on

those who deny the causal nexus to show that the cause is

something else").

Furthermore, the district court improperly assumed

that lack of motivation caused lower turnout at the Phillips

County polls. See Gomez v. City of Watsonville. 863 F.2d

1407, 1416 (9th Cir. 1988) (stating that the district court

should have focused only on actual voting patterns rather than

speculating on reasons why minority voters were apathetic),

cert denied. ___U.S. ___ , 109 S.Ct. 1534, 103 L.Ed.2d

839 (1989); Dallas County Comm’n. 739 F.2d at 1536

(concluding that "[t]he existence of apathy is not a matter for

- 35a -

judicial notice"); Marengo County Comm’n. 731 F.2d at

1568-69 (noting that "[b]oth Congress and the courts have

rejected efforts to blame reduced black participation on

’apathy’"). Also, the internal documents in this case simply

do not support such an assumption. While, as the district

court recognized, blacks are working strenuously in Phillips

County to register black voters and to encourage black voter

participation, voter turnout is still low. Yet, black turnout at

some of the general primary (runoff) elections did not drop as

significantly as did white voter turnout, when compared with

the preceding preferential primary. These factors indicate to

us that black voters are not apathetic. We believe that other

factors contribute to a lack of political participation which

nonparticipation is significant enough to make a runoff

election victory an impossibility for a black candidate.

The plaintiffs presented statistical and expert evidence

on the lower social, educational, and employment conditions

in Phillips County. Contrary to the district court’s

- 36a -

determination, we conclude that such evidence is relevant to

prove cause and effect. Thus, without more, the plaintiffs

adequately carried their burden of proof that the majority

runoff requirement, as it operates in the political system of

Phillips County, has caused blacks in that county to have less

opportunity than whites to elect the candidate of their choice.3

The Senate Report states that the factors enumerated

3 Judge Hanson’s research in this matter turns up a

significant factor which none of the parties has addressed

through evidence or in briefs or oral argument; that is, that

Arkansas election law does not preclude cross-party voting in

runoff (general) primary elections. It is factually uncontested

that virtually no white voters support black candidates in

Phillips County.

Thus, the Phillips County runoff system permits white

Republicans, if they have a mind to do so, to, at least in

limited circumstances, support a white Democrat in a runoff

primary and to further dilute black voting strength. This

cross-over factor distinguishes and attenuates the holding in

Butts v. City of New York. 779 F.2d 141 (2d Cir. 1985)

since Butts clearly dealt with a closed (no cross-over) runoff

primary. While we subscribe to Chief Judge Oakes’ panel

dissent, which opinion fully supports our results, we believe

that the precedential value of the majority opinion in Butts is

erased when the cross-over component is added to the factual

mix.

- 37a -

"will often be the most relevant ones," though in certain cases

other factors may also be used to show vote dilution. S. Rep.

No. 417 at 29, 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News at

207. Here, a majority of the factors have been found by the

district court to exist in Phillips County. Furthermore, the

findings relating to the third and fourth factors do not weigh

against the plaintiffs’ proof. However, the final determination

"of whether the voting strength of minority voters is * * *

’canceled out’" demands the court’s "overall judgment, based

on the totality of the circumstances and guided by those

relevant factors in the particular case." Id. at 29 n. 118,

1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News at 207. We

conclude that, based on the proof set forth by Whitfield and

the totality of the circumstances in Phillips County, a section

2 violation has been established under the results test.4

4 Whitfield has also asserted the argument that the

district court erroneously dismissed the plaintiffs’ challenge to

the general election majority vote requirement. Before trial,

the district court dismissed plaintiffs’ claim, citing as one of

its reasons lack of standing. Whitfield asserts that plaintiffs

- 38a -

C. Remedy

We are well aware of the difficulty of fashioning a

remedy for Phillips County alone, while allowing the other

counties of Arkansas to continue implementing a majority vote

runoff requirement for primary elections. However, the

evidence requires just such a remedy, and courts have created

remedial orders which affect only one legislative district,

while affecting no other portion of the Arkansas state

legislative structure. See Smith v. Clinton. 687 F. Supp. at

1311; Smith v. Clinton. 687 F. Supp. at 1362 (rejecting the

argument that any plan affecting only a single legislative

district would interfere with the state-wide scheme of

apportionment).

Where, as here, a violation of the Voting Rights Act

had standing because they are black citizens and registered

voters. We disagree with this argument. We conclude that

the challenge was properly dismissed because the plaintiffs

lacked standing in that no black had ever participated as a

candidate in an election covered by the general (multi-party)

election runoff statute and they failed to allege that such

elections have been discriminatory in Phillips County.

- 39a -

has been established, "courts should make an affirmative

effort to fashion an appropriate remedy for that violation."

Monroe v. City of Woodville. Mississippi. 819 F.2d 507, 511

n. 2 (5th Cir. 1987) (per curiam), cert, denied. 484 U.S.

1042, 108 S.Ct. 774, 98 L.Ed.2d 860 (1988). The legislative

history of the Act states:

The basic principle of equity that the remedy

fashioned must be commensurate with the right that

has been violated provides adequate assurance, without

disturbing the prior case law or prescribing in the

statute mechanistic rules for formulating remedies in

cases which necessarily depend upon widely varied

proof and local circumstances. The court should

exercise its traditional equitable powers to fashion the

relief so that it completely remedies the prior dilution

of minority voting strength and fully provides equal

opportunity for minority citizens to participate and to

elect candidates of their choice.

S. Rep. No. 417 at 31, 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin.

News at 208 (footnote omitted). In sum, "’the [district] court

has not merely the power but the duty to render a decree

which will so far as possible eliminate the discriminatory

effects of the past as well as bar like discrimination in the

- 40a -

future.’" Ketchum v, Byrne. 740 F,2d 1398, 1412 (7th Cir.

1984) (quoting Louisiana v. United States. 380 U.S. 145,

154, 85 S.Ct. 817, 822, 13 L.Ed.2d 709 (1965)), cert.

denied, sub nom. City Council v. Ketchum. 471 U.S. 1135,

105 S.Ct. 2673, 86 L.Ed.2d 692 (1985).

We agree with the Seventh Circuit that it is not the

proper role of an appeals court to formulate its own remedial

plan "or to dictate to a district court minute details of how

such a plan should be devised." Ketchum. 740 F.2d at 1412.

Therefore, we remand this case to the district court with

directions to formulate an appropriate remedy for violation of

the Voting Rights Act in Phillips County. We instruct the

district court to limit its remedy to within the borders of

Phillips County, since the evidence requires such a limitation.

We are well aware of the district court’s concerns that

elimination of the primary runoff requirement may not

provide a total solution to the problem of the inability of

black candidates to be elected in Phillips County and, indeed,

- 41a -

may perpetuate racially polarized voting there. However, the

majority vote requirement has, up to this point, prevented

blacks from electing the candidates of their choice, and so,

the elimination of that requirement is mandated by section 2.

While the duties of a district judge are multitudinous,

accurately forecasting the future is not one of them.

Legislators are responsible for the results stemming from their

decision-making. Thus, these potential problems are for

Congress, not the courts, to solve. If the remedy fashioned

for Phillips County serves to intensify the problem, as the

district court anticipates, then the Congress will have to

reevaluate section 2 as it is applied to realistic voting

situations and the realities of political life in America.

III. CONCLUSION

Section 2 was broadly written to protect minorities

from disparate voting practices and procedures, including

majority vote requirements. The Gingles Court stated that

"[t]he essence of a § 2 claim is that a certain electoral law,

- 42a -

practice, or structure interacts with social and historical

conditions to cause an inequality in the opportunities enjoyed

by black and white voters to elect their preferred

representatives." Gingles. 478 U.S. at 47, 106 S.Ct. at 2764.

We determine that this definition encompasses the Phillips

County situation.

Therefore, while we affirm the district court’s

conclusion that Whitfield failed to prove his constitutional

claim, we reverse the court’s conclusion that section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended in 1982, is

inapplicable. We conclude that section 2 is violated by the

application of Ark. Code Ann. § 7-7-202 to Phillips County,

Arkansas. Thus, we remand to the district court for

determination of the appropriate remedy in accordance with

the instructions set forth in this opinion.

HANSON, Senior District Judge, concurring.

I write separately to express my concern over the

remedy that will be required by this ruling. Although we

- 43a -

have left the remedy unspecified, it will necessarily leave

Phillips County, Arkansas, with a voting procedure that, at

least temporarily, varies from that used in the rest of the

state.5 This is a situation which I believe courts should avoid

whenever possible because the fragmentation of state law is

a grave matter. There is, however, no way to avoid this

situation in this case.

The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution undeniably vest Congress and the

Judiciary with the power to end any and all state voting

procedures which abridge the rights of minority citizens to

vote. City of Rome v. United States. 446 U.S. 156, 173-

79, 100 S.Ct. 1548, 1559-63, 64 L.Ed.2d 119 (1979); South

Carolina v. Katzenback, 383 U.S. 301, 323-27, 86 S.Ct. 803,

5 It appears that the district court may receive some

guidance on the potential breadth of the remedy available in

this case by the ultimate disposition of Spallone v. United

States. 856 F.2d 444 (2nd Cir. 1988), cert, granted. ___U.S.

__ , 109 S. Ct. 3211, 106 L.Ed,2d 562 (1989) (argued Oct.

2, 1989).

- 44a -

815-18, 15 L.Ed.2d 769 (1965). Congress, acting within the

authority granted by these provisions of our Constitution, has

mandated that no state voting procedure can be allowed to

stand which "results" in the dilution of the voting strength of

a traditionally disadvantaged racial group in "any state" or

"subdivision" thereof. See 42 U.S.C. § 1973 (1982). I am

bound to follow this mandate.

In this case, a most able and fair district judge has

found inequalities which indicate a violation of this law in

Phillips County, Arkansas. There is no doubt in my mind,

that under the present factual situation, the primary run-off

requirement dilutes the votes of Phillips County blacks in a

manner proscribed by the Voting Rights Act. Further, I am

not prepared to accept as a major premise in syllogistic

argument the premise, which I believe underlies Judge

Bright’s dissent, that there can be no injustice where majority

vote rules.

I do not know that Congress, in its passage of the

- 45a -

1982 Amendments to the voting Rights Act and adoption of

the "results" test, fully recognized that the statute as crafted

would open the door to the fragmentation of state law when

a statewide law is shown to result in a dilution of minority

voting strength in only one subdivision of a state. I assume,

however, that Congress did intend the natural consequences

of its actions. If they did not, it is up to Congress to act

pursuant to their wisdom to change the law—not this court.

Thus, because the people of this country, through the

Congress and the Constitution, have decreed that no state

voting procedure can be allowed to stand which results in the

dilution of the voting rights of racial minorities in a

subdivision of a state, I join in striking down the application

of the law at issue in Phillips County.

I harbor no illusions that this ruling enforcing the

Voting Rights Act will dissolve the racial prejudice which

continues to haunt Phillips County. There are problems in

social and political human relations which defy solution by

- 46a -

legislative action. And, as noted by Justice Holmes,

legislative efforts to solve these problems often create

uncertainties over which judges, with all their frailties, labor.

Racial problems, are now, and have been, one of these most

difficult areas of concern. Thus, although I join in striking

down the barrier in this case, it seems to me that such

problems can only be truly "solved" by time, patience, and

most importantly, education.

My study and research on this matter does not disclose

a perfect precedent for that action which we take today.

BRIGHT, Senior Circuit Judge, concurring in part and

dissenting in part.

I write separately to express my disagreement with the

reasoning and conclusion of the majority regarding section 2

of the Voting Rights Act. This case presents a voting rights

challenge to the use of run-off primaries in elections for

single-member offices, a procedure that without more does

not dilute the opportunity of any group of voters to participate

- 47a -

equally with other voters in the political processes leading to

the nomination and election of public officials. Accordingly,

I dissent.

Run-off primaries serve a basic principle of

representative government: majority rule. States have always

had the right to require that a majority of the voters support

the winner of an election. While it is unquestionably true that

run-off primaries combined with at-large elections or other

dilutive electoral devices can produce discriminatory results,

see Thornburg v. Gingles. 478 U.S. 30, 56, 106 S.Ct. 2752,

2769, 92 L.Ed.2d 25 (1986); City of Port Arthur v. United

States. 459 U.S. 159, 167, 103 S.Ct. 530, 535, 74 L.Ed.2d

334 (1983); Rogers v. Lodge. 458 U.S. 613, 627, 102 S.Ct.

3272, 3280, 73 L.Ed.2d 1012 (1982); White v. Regester. 412

U.S. 755, 766, 93 S.Ct. 2332, 2339, 37 L.Ed.2d 314 (1973),

no federal court has ever taken the position that run-off

primaries standing alone violate section 2. Moreover, the

only court ever faced with this issue reached the opposite

- 48a -

conclusion. Butts v. City of New York. 779 F.2d 141 (2d

Cir. 19851. cert, denied. 478 U.S. 1021, 106 S.Ct. 3335, 92

L.Ed.2d 740 (1986). Because of the importance of the

principle underlying run-off primaries, their long history and

the absence of authority for the position the court today

adopts, I would require explicit direction from Congress

before invalidating the use of run-off primaries standing

alone.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act is less than explicit.

It states that an electoral procedure violates the Act if

based on the totality of circumstances, it is shown that

the political processes leading to nomination or

election in the State or political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by [minority voters] in

that [minority voters] have less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate in the political

process and to elect representatives of their choice.

42 U.S.C. § 1973(b) (1982).

Section 2 forbids two types of electoral procedures:

restrictive procedures that prevent members of a minority

group from voting and procedures that have the effect of

- 49a -

diluting minority voting strength. Butts. 779 F.2d at 148.

In this case we confront the issue whether the use of run-off

primaries standing alone dilutes minority voting strength.

This issue does not lend itself to easy analysis because the

phrase "vote dilution" "suggests a norm with respect to which

the fact of dilution may be ascertained." Mississippi

Republican Executive Comm, v. Brooks. 469 U.S. 1002,

1012, 105 S.Ct. 416, 422-23, 83 L.Ed.2d 343 (1984)

(Rehnquist, J., dissenting from summary affirmance). No

such norm exists.

The Senate Report accompanying the 1982

amendments to the Act set forth a list of "typical" factors

relevant to the existence of a section 2 violation. S. Rep. No.

417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 28-29, reprinted in 1982 U.S.

Code Cong. & Admin. News 177, 206-07. While the

Supreme court discussed these factors with approval in

Thornburg v, Gingles. the Court nevertheless observed

that this list of typical factors is neither comprehensive

- 50a -

nor exclusive. While the enumerated factors will often

be pertinent to certain types of § 2 violations,

particularly to vote dilution claims, other factors may

also be relevant and may be considered. Furthermore,

the Senate Committee observed that "there is no

requirement that any particular number of factors be

proved, or that a majority of them point one way or

the other. Rather, the Committee determined that "the

question whether the political processes are ’equally

open’ depends upon a searching practical evaluation of

the ’past and present reality,”' and on a "functional"

view of the political process.

478 U.S. at 45, 106 S.Ct. at 2763-64 (citing S. Rep. No.

417, 97th Cong. 2d Sess. 29, reprinted m U.S. Code Cong.

& Admin. News at 206-07) (footnote and citations omitted).

In this case, the majority does not conduct a searching

evaluation but simply adds up a number of factors and

concludes that a violation has occurred. Moreover, the

majority fails to recognize that the district court conducted

an appropriate evaluation.

In analyzing the effect of the run-off primary on the

nomination of black candidates, District Judge Eisele quoted

from the work of Professor Harold Stanley:

- 51a -

The likelihood of black nominees gaining a plurality

of the primary vote in a crowded field seems enticing

enough to encourage some to argue for ending the

runoff. However, in majority black districts—as

supporters of the runoff point out-the lack of a runoff

might cause several black candidates to split the black

vote and allow a white candidate to gain a plurality

nomination. Thus, the runoff can protect and promote

black political prospects in majority black districts.

Whitfield v. Democratic Party. 686 F. Supp. 1365, 1378

(E.D. Ark. 1988) (quoting Stanley, Runoff Primaries and

Black Political Influence, in Blacks in Southern Politics 259,

262-63 (1987)). Other commentators agree that invalidating

the use of run-off primaries may hamper the ability of black

voters to nominate their preferred representatives.

McDonald, The Majority Vote Requirement: Its Use and

Abuse in the South. 17 Urb. Law. 429, 437-38 (1985);

Butler, The Majority Vote Requirement: The Case Against

Its Wholesale Elimination. 17 Urb. Law. 441, 454 (1985).

The able district judge cited evidence in the record to support

his conclusion that the use of run-off primaries does not

produce discriminatory effects: "The blacks have a voting

- 52a -

age population majority in some of the Justice of the Peace

districts in Phillips County. If two or more blacks chose to

run in the primary and only one white, then the same

possibility, i.e., of a minority white plurality nominee, would

occur." Whitfield. 686 F. Supp. at 1378. District Judge

Eisele, residing in the state of Arkansas and familiar with its

political processes, is in a far better position than we appellate

judges to evaluate whether the run-off primary denies black

voters an equal opportunity to nominate candidates of their

choice.

Judge Eisele also reasoned that the existence of the

run-off primary has the effect over time of easing racial

polarization in voting. "[Plurality-win statutes or rules

promote racial polarization and separation. Run-off

provisions promote communication and collaboration among

the various constituencies by which coalitions are built."

Whitfield. 686 F. Supp. at 1386. In support of this

statement, Judge Eisele observed:

- 53a -

For Democratic candidates, nomination rules that

encourage the seeking of biracial support, promote

prospects for election. Retaining the runoff can lead

to more black-white coalitions that [sic] back

Democratic candidates who make successful biracial

appeals. Courting and composing such biracial

coalitions require a politics that is capable of reducing

racial polarization, rather than reinforcing it. Such

political cooperation between the races provides a

more promising basis for collaboration on the eventual

nomination and election of southern black candidates.

On the other hand, eliminating the runoff where strong

racial polarization exists-even if this would produce

more black nominees (which seems unlikely)-should

mean continued racial polarization....

Id. at 1386 (quoting Stanley, Runoff Primaries and Black

Political Influence, in Blacks in Southern Politics 259, 264

(1987)). Racial polarization needs discouragement not

enhancement. We should avoid any conclusion, such as the

one the majority reaches today, that has the effect of

continuing racial polarization in voting.

In addition to failing to recognize that the

determination of a section 2 violation depends on a searching

evaluation of the political process, the majority opinion

o

- 54a -

contains a second flaw: none of the authority cited by the

majority supports a conclusion that section 2 applies to run

off primaries standing alone. The majority refers to the

Supreme Court’s recognition that majority voting requirements

are "potentially dilutive electoral devices...." Thornburg v.

Gingles. 478 U.S. at 56, 106 S.Ct. at 2769. But the Court

in Gingles was referring to the use of majority vote

requirements in connection with multi-member districts. The

majority also refers to language in Westwego Citizens for

Better Gov’t v. City ofWestwego. 872 F.2d 1201, 1212 (5th

Cir. 1989), that majority voting requirements "could serve to

further dilute the voting strength of minorities." The

Westwego court, however, was remanding to the district court

for a determination of whether an at-large voting scheme

diluted the voting strength of minorities in violation of section

2. The Westwego court was merely recognizing that a

majority vote requirement combined with an at-large voting

scheme could dilute minority voting strength. Finally, the

- 55a -

majority states that the Senate Report that accompanied the

1982 amendments identified a number of "dilution schemes,"

including "majority run-offs...." S. Rep. No. 417, 97th

Cong. 2d Sess. 6, reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code Cong. &

Admin. News at 183. The quoted portion of the Senate

Report, however, is discussing section 5, dealing with pre

clearance of legislative efforts to undermine the Act. Section

5 is obviously not at issue here and the Arkansas legislature

enacted the run-off primary law long before passage of the

Voting Rights Act.

As stated earlier, the only court to address the use of

run-off primaries reached a conclusion different from the one

the majority reaches today. Butts v. City of New York. 779

F.2d 141 (2d Cir. 1985). Butts involved a voting rights

challenge to a New York statute that required a run-off

primary if no candidate received more than 40% of the vote

in the general primary. In holding that in the absence of

dilutive electoral procedures the run-off primary at issue did

- 56a -

not violate section 2, the court stated:

Whereas, in an election to a multi-member body, a

minority class has an opportunity to secure a share of

representation equal to that of other classes by electing

its members from districts in which it is dominant,

there is no such thing as a "share" of a single-member

office. The distinction is implicit in City of Port

Arthur v. United States. 459 U.S. 159, 103 S.Ct. 530,

74 L.Ed.2d 334 (1982), where the Court struck down

a run-off requirement that Port Arthur had appended

to its at-large voting system for seats on the multi

member city council, but made no mention of a similar

run-off requirement for the election of mayor. The

latter run-off was not even challenged.

The rule in elections for single-member offices

has always been that the candidate with the most votes

wins, and nothing in the Act alters this basic political

principle. Nor does the Act prevent any governmental

unit from deciding that the winner must have not

merely a plurality of the votes, but an absolute

majority (as where run-offs are required when no

candidate in the initial vote secures a majority) or at

least a substantial plurality, such as the 40% level

required by § 6-162.

Id. at 148-49. The Butts rationale gives strong support to the

district court’s perceptive and well-reasoned opinion.1

1 Judge (now Chief Judge) Oakes dissented in Butts,

contending that while minority voters have no right to "a

proportionate ’share’" of a single member office, "they do

have a right not to be subject to any structural process that

- 57a -

For all of the reasons given above, I would affirm.

under the totality of circumstances deprives them of equal

opportunity to field a candidate for one of those offices." 779

F.2d at 155 (Oakes, J., dissenting). Judge Oakes further

opined that a run-off election after an open primary would not

violate section 2. Ick (Oakes, J., dissenting). In footnote 3

of its opinion, the majority reveals that in this case Arkansas

law does not prohibit cross-party voting. Thus, the Butts

dissent seems not to support the opinion of the majority.

- 58a -

MEMORANDUM OPINION OF THE DISTRICT

COURT DISMISSING PETITIONERS5

CHALLENGE TO THE PRIMARY

RUNOFF STATUTE

Sam Whitfield, Jr., Linda Whitfield, P.L. Perkins, Julious

McGruder, Georgia M. Varner, Annie Sykes, Ollie Jennings,

and Sam Bennett, Plaintiffs.

v.

The Democratic Party of the State of Arkansas, the State of

Arkansas Democratic Central Committee, and the Phillips

County Democratic Central Committee, Defendants.

No. H-C-86-47.

United States District Court,

E.D. Arkansas, E.D.

May 20, 1988.

Oily Neal, Kathleen Bell, Marianna[;j Lani Guinier,

Pamela S. Karlan, New York City, for plaintiffs.

Tim Humphries, Asst. Atty. Gen., Little Rock, Ark.,

for defendants.

MEMORANDUM OPINION

EISELE, Chief Judge.

This case involves a challenge to Ark. Code Ann. § 7-

- 59a -

7-202, which requires that a candidate receive a majority of

the votes cast in a political party’s primary election in order

to obtain the nomination of that political party. That section

provides in pertinent part:

Whenever any political party shall, by primary

election, select party nominees as candidates ... for

any United States, state, district, county, township, or

municipal office, the party shall hold a preferential

primary election and a general primary election on the

respective dates provided in section 7-7-202(a) and

(b).

Without spelling it out the plaintiffs are actually attacking

Amendment 29, Section 5 of the Constitution of Arkansas

(adopted November 8, 1938) which provides:

Only the names of candidates for office nominated by

an organized political party at a convention of

delegates, or by a majority of all the votes cast for

candidates for the office in a primary election, or by

petition of electors as provided by law shall be placed

on the ballots of any election. (Emphasis Supplied)

The majority vote requirement is established by Amendment

29 and the mechanisms for carrying it out are set forth in

section 7-7-202.

- 60a -

Plaintiffs are proceeding under two distinct theories.

First, they contend that section 7-7-202 and Amendment 29

result in their being less able than white citizens to participate

in the political process and elect the candidates of their

choice. This cause of action arises, they state, entirely under

section 2 et seq. of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 et seq. See Plaintiffs’ Pretrial

Brief, p. 2. Secondly, plaintiffs allege that section 7-7-202

and Amendment 29 were enacted and have been maintained

for racially discriminatory reasons and, therefore, violate the

fourteenth and fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution.

The Court will deal with the latter contention first, i.e.,

plaintiffs’ "intent" claims.

Plaintiffs’ Constitutional Claims

Plaintiffs rely upon the City of Mobile v. Bolden. 446

U.S. 55, 100 S.Ct. 1490, 64 L.Ed.2d 47 (1980) and Rogers

v. Lodge. 458 U.S. 613, 102 S.Ct. 3272, 73 L.Ed.2d 1012

(1982). Under this theory, plaintiffs must establish that

- 61a -

section 7-7-202 and Amendment 29 were enacted, or has been

maintained, for a discriminatory purpose. As stated in

Village_of Arlington Heiehts v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp.. 429 U.S. 252, 266, 97 S.Ct. 555, 564,

50 L.Ed.2d 450 (1977):

[D]etermining whether invidious discriminatory

purpose was a motivating factor demands a sensitive

inquiry into such circumstantial and direct evidence as

may be available."

In making this determination, the Court may consider the

factors identified in the Senate Report along with all the other

facts and circumstances. See infra discussion of section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965. As the Court understands the

law in this area, if legislation was motivated or maintained

out of a desire to discriminate against blacks on account of

their race and if, indeed, such legislation in fact has that

effect, it would violate the Equal Protection clause. With

these legal principles in mind, the Court will discuss the

history of Amendment 29 and section 7-7-202.

- 62a -

Arkansas has had such a majority-vote requirement

since 1933. Prior to that time, at least two counties in

Arkansas followed the practice without the benefit of any act

of the Legislature.

In his inaugural address in January 1933, Governor

Futrell stated, "nominations for public office should be made

by a majority of the qualified electors voting at an election.

By no means should an insubstantial minority be allowed to

make a nomination." The bill was approved by the Senate by

a vote of 28 to 0 on January 18, 1933, and passed the House

by a vote of 84 to 3 on February 14. The Governor signed

the bill and it became Act 38 of 1933.

Mr. Henry Alexander, in his article, "The Double

Primary" in Volume 3 of the Arkansas Historical Orderly

(1944) (cited by all parties and also by several of the

witnesses) explained the overwhelming vote as follows:

In view of the potent opposition in the legislature to

earlier bills providing a double primary, passage of

Act 38 with only three negative votes is difficult to

- 63a -

understand. The hectic Democratic primaries of 1932

may in some measure explain revival of agitation for

the double primary system. The primary ballot of that

year in Pulaski County, described as being "as long as

your arm," contained seventy-six names exclusive of

candidates for nomination to township offices and for

election to party office. The ballot listed seven

candidates for the gubernatorial nomination, a like

number for the United States senatorial nomination.

Six entrants sought the nomination for lieutenant

governor and twenty candidates filed for seven other

contested nominations to state office. Winners in

several races failed to poll a majority of the votes

case. J.M. Futrell, nominee for governor, polled less

than forty-five per cent; Lee Cazort, nominee for

lieutenant governor, less than thirty-one per cent.

Converted to the principle of majority nominations by

numerous minority nominations in the primaries of this

and former years, a small group of influential citizens

organized a Run-Off Primary Association. This short

lived organization was formed to advocate enactment

of a double primary law at the 1933 session of the

General Assembly. The organization, its headquarters

in Little Rock, chose J. Bruce Streett, president, and

Grady Forgy, secretary. Its officers had a hand in

drafting Act 38 and its influence counted for much in

obtaining passage of the statute.

During the 1935 legislative session, Act 38 was

repealed. This prompted a movement to embody the

majority-vote double primary system into the Arkansas

Constitution where it would be beyond legislative power.

- 64a -

According to Mr. Alexander, in 1928, Mr. Brooks

Hayes was runner-up in a seven-man race for the

gubernatorial nomination which was won by Harvey Parnell

with a plurality of less than 42%. Two years later, Mr.

Hayes urged adoption of the double primary system in the

form of an initiated amendment to the Constitution. Mr.

Collins was at that time president of the Arkansas Bar

Association. This effort culminated in the adoption of

Amendment 29 to the Arkansas Constitution. The amendment

covers a variety of "good government" election principles.

For our purposes, the most important is found in Section 5,

which reads:

Only the names of candidates for office nominated by

an organized political party at a convention of

delegates, or by a majority of all the votes cast for

candidates for the office in a primary election, or by

petition of electors as provided by law, shall be placed

on the ballots in any election.

As stated by Alexander:

Sponsors of the proposed amendment were moved,

primarily, by hostility to committee nominations and

- 65a -

special elections and, secondarily, by hostility to

plurality nominations. The latter, however, should not

be minimized. The section of Amendment 29

requiring the double primary was included in earliest

drafts of the proposal. Suggestions, at one time

considered, to incorporate provision for a double

primary in a separate amendment were discarded.

Writing on August 31, 1937, Abe Collins stated, with

reference to the section of the proposed amendment

requiring the double primary, "I think it is the most

important part of it (draft of Amendment 29)."

Opposition to minority nominations was strengthened

in some quarters when, in the primary of August 11,

1936, Carl E. Bailey won the gubernatorial nomination

in a five-man race by a plurality of less than thirty-

two percent of the votes cast.

Amendment 29 was laboriously drafted during

a period of almost a year by Abe Collins, Judge B.E.

Isbell of DeQueen, and Doctor Robert A. Leflar of

Fayetteville. C.T. Coleman of Little Rock and Doctor

J.S. Waterman of Fayetteville cooperated.

Dr. Leflar and Dr. Waterman are recognized nationally as

legal scholars.

Over 18,000 signatures were needed in order to initiate

Amendment 29. The effort was successful. According to

Mr. Alexander:

The press of Arkansas vigorously and almost without

exception supported ratification of Amendment 29 at

- 66a -

the general election in November, 1938. No organized

opposition appeared and, on November 8, the measure

was approved by narrow margin of 63,414 to 56,947.

Opposition to ratification was somewhat centered in

so-called "machine" counties. In eleven counties often

so characterized ratification was opposed by a popular

majority of 61.5 per cent of votes cast in these

counties.

Two temporary enabling acts were then passed.

In 1939, the Legislature proposed Amendment 30 to

the Constitution which would have abolished the double