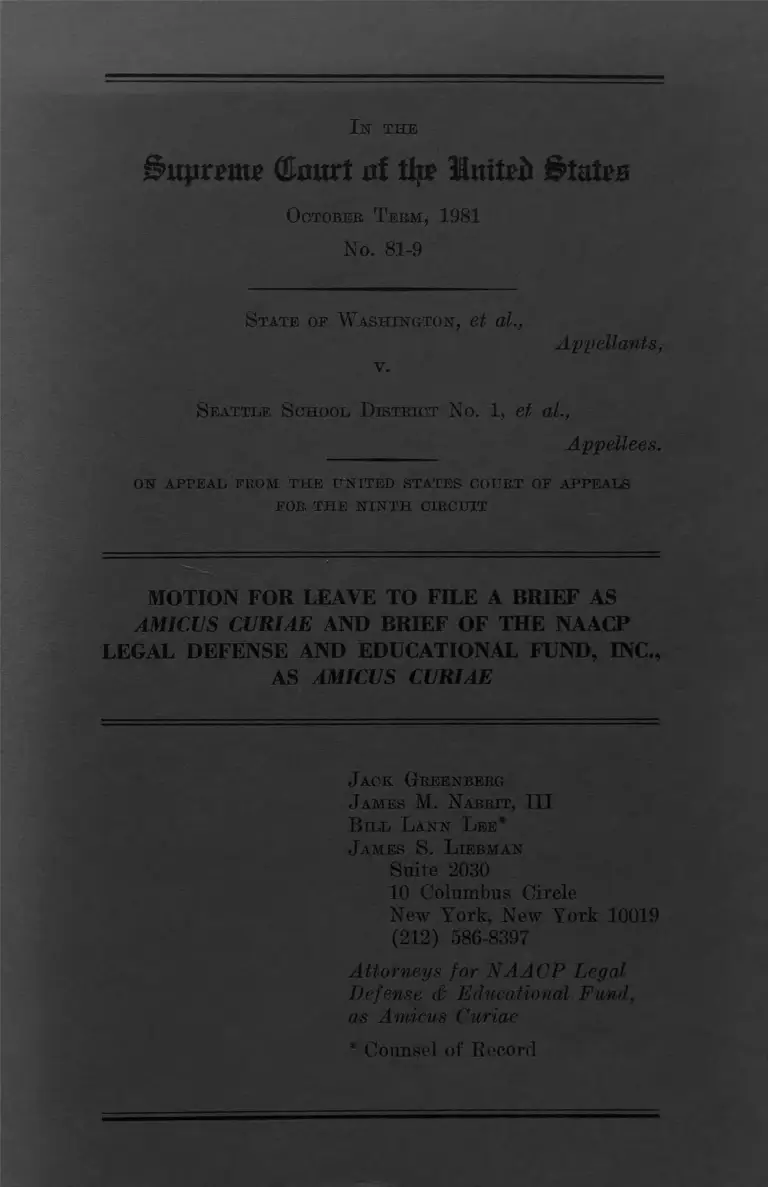

Washington State v. Seattle School District No. 1 Brief Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal Defense Fund

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Washington State v. Seattle School District No. 1 Brief Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal Defense Fund, 1981. 028d4597-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5e8610e7-bf8b-4d80-b587-766c7270493a/washington-state-v-seattle-school-district-no-1-brief-amicus-curiae-naacp-legal-defense-fund. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Xw th e

S>upr£m? fflourt of % Intteii States

O ctober T erm , 1981

No. 81-9

S tate of IV ash in g to n , et al.,

v.

Appellants,

S eattle S chool D istrict No. 1, et al.,

Appellees.

OH APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AS

AMICUS CURIAE AND BRIEF OF THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AS AMICUS CURIAE

J ac k Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, I II

B ill L a n k L ee*

J am es S. L iebm an

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for NAACP Legal

Defense <§ Educational Fund,

as Amicus Curiae

* Counsel o f Record

INDEX

Table o f A u t h o r i t i e s ............................... i i i

Motion For Leave For NAACP Legal

Defense and Educat iona l Fund,

Page

I n c . , To F i l e A B r i e f

Amicus Curiae .................................... 1

Question Presented .................................... 6

B r i e f For the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educat iona l Fund, I n c . ,

as Amicus Curiae ............................. 7

Summary o f Argument ................................. 7

Argument ........................................................... 9

I . I n i t i a t i v e 350 V i o l a t e s

The Fourteenth Amendment's

Most Bas ic P r o h i b i t i o n By

S t r u c t u r in g The P o l i t i c a l

Process So That Governmental

A c t i o n B e n e f i t in g The Minor

i t y V ic t im s Of School Segre

g a t i o n Is More D i f f i c u l t To

Achieve Than Governmental

A c t i o n B e n e f i t in g A l l Other

C i t i z e n s .................................................... 9

A. R a c ia l C l a s s i f i c a

t i o n s D i s t o r t i n g the

P o l i t i c a l Process ...................... 12

B. Hunter v. Er ickson .......... 15

i

Page

C. Nyquist v. Lee ................... 27

D. I n i t i a t i v e 350 ................... 34

I I . R a c ia l I n t e a r a t i o n Of

P u b l i c Education In Appel

l e e Loca l D i s t r i c t s , Which

I n i t i a t i v e 350 Nonneutral ly

F r u s t r a t e s , Is A L e g i t im a te ,

Indeed P r e s s in g , P o l i t i c a l

O b j e c t i v e o f Black C i t i z e n s

In A p p e l l e e Schoo l D i s t r i c t s . . . 47

C onc lus ion 56

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Alexander v. Holmes County

Board o f Educat ion , 396 U.S.

19 ( 1 969) .................................................... 3 ,49

Avery v. Midland County,

390 U.S. 474 ( 1 968) ............................. 13

B o l l i n a v. Sharpe,

347 U.S. 499 ( 1 954) . .......................... 10

Brown v. Board o f Educat ion ,

347 U.S. 483 ( 1 954) ............................. 3

Crawford v. Board o f Education

o f the C i t y o f Los A nge les ,

No. 8 1-38 ........................ ............................ 23

C i t i z e n s Against Mandatory

Bussinq v. Palmason,

495 P. 2d 657 (Wash. 1 972) ............. 36,37

Columbus Board o f Education

v. P en ick , 443 U.S. 449

(1979) .................................................... 3 , 5 , 2 3 , 2 4

31,54

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1

(1958) .................................................... 3

Dayton Board o f Education v.

Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406

( 1 977) ........................................................... 18

Dunn v. Blumstein,

405 U.S. 330 ( 1972) ............................. 12

- iii -

Page

Evans v. Buchanan, 398

F. Supp. 428 (D. Del.)r

a f f ' d , 423 U.S. 963 (1975) ............ 30

Ex p a r te V i r g i n i a , 100 U.S.

339 ( 1 880) .................................................. 10

Fo ley v. C on n e l i e , 435 U.S.

291 ( 1 978) .................................................. 1 1

Green v. County Schoo l Board, 391

U.S. 430 ( 1 968) ................. ............. 3

Harper v. V i r g i n i a Board

o f E l e c t o r s , 383 U.S.

663 ( 1 966) ........................ ......................... 12

Hunter v . E r ickson ,

393 U.S. 385 ( 1 969) ....... .................... passim

In re G r i f f i t h s ,

413 U.S. 717 ( 1973) ............................. 1 1

James v. V a l t i e r r a ,

402 U.S. 1 37 ( 1 971 ) ............................. 44

Keyes v. School D i s t r i c t No. 1,

413 U.S. 1 89 ( 1 973) ------ ---------- 3

Lovinq v. V i r g i n i a ,

388 U.S. 1 ( 1 967) ................................. 10

Massachusetts Board o f

Ret irement v. Murgia,

427 U.S. 307 (1 976) ............................. 1 1

IV

Page

McDaniel v. B a r r e s i ,

402 U.S. 39 ( 1971 ) ............................... 48

McLauqhlin v. F l o r i d a ,

379 U.S. 39 ( 1971 ) ............................... 10

M i l l ik e n v. Bradley ,

418 U.S. 717 ( 1 974) ............................. 27,35

Mobile v. Bolden,

446 U.S. 55 ( 1 980) ................... 1 1,1 4 ,2 2 ,4 5

New York G a s l iq h t Club, Inc . v.

Carey, 447 U.S. 54 (1980) ____ 5

Nixon v. Herndon,

273 U.S. 536 ( 1927) .......................... 1 1,1 2,31

North C aro l in a Sta te Board

o f Educat ion v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 ( 1971 ) ............................. 2 4 ,2 8 ,4 9

Nyquist v . Lee, 401 U.S. 935

a f f 1g , 318 F. Supp. 710

(W.D~N.Y. 1970) ...................................... passim

Personnel A dm in is t ra tor v.

Feeney, 442 U.S. 256

( 1979) ........................................................... 22,44

Regents o f the U n iv e r s i t y o f

C a l i f o r n i a v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265 ( 1 978) ...................................... 47

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S.

533 ( 1 964) .................................................. 13

v

Paae

San Antonio School D i s t . v .

Rodr iquez , 411 U.S. 1

( 1973) ................................. .................... . 11 ,25 ,34

S e a t t l e Schoo l D i s t . No. 1

v. Washington, 473 F. Supp.

996 (W.D. Wash. 1979), a f f ' d ,

633 F .2d 1338 (9th C ir .

1980) ......................................................... 3 6 , 3 7 ,4 0 ,

41,42

Slaughterhouse Cases,

83^U.S. 36 (1973) ............................. 10

S ta te ex r e l . Lukens v.

Spokane Schoo l D i s t r i c t 81,

147 Wash. 467 ( 1 928 ) ................... . 36

Strauder v. West V i r g i n i a ,

100 U.S. 303 ( 1880) ................. . . . 10

Swann v . C har lo t te -M eck lenburg

Board o f Educat ion , 402 U.S.

1 (1971) .................................................. 3 , 2 8 , 4 1 ,

48,49

Takahashi v. Fish and Game

Comm'n, 334 U.S. 410 (1948) . . . 11

United S ta te s v. Carolene

Products C o . , 304 U.S.

144 ( 1 938) ........................................ .. 10,25

V i l l a g e o f A r l in g t o n Heights

v. M e tro p o l i tan Housing

A u t h o r i t y , 429 U.S. 252

(1977) ....................................................... 44

- v i -

Page

Washinqton v. Davis , 426 U.S.

229 ( 1976) .................................................. 44

White v. R e g e s te r , 412 U.S.

755 ( 1 973) .................................................. 1 1,12

Wright v. Counci l o f the

C i ty o f Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 ( 1 972) .................................................. 23,24

Other A u t h o r i t i e s :

Buses: Backbone o f Urban T r a n s i t ,

The American C i t y , Dec. 1974 . . . . 50

120 Cong. Rec. 8757 ( 1 974) ................. 50

Davis , Bussing, in 2 R. Crain ,

e t a l . , Southern S c h o o l s : An

Evaluat ion o f the Emergency

School A s s i s t a n c e Program and

o f School D esegregat ion ( 1 9 7 3 ) . . . 51

Department o f T r a n s p o r t a t i o n ,

T ra n sp o r ta t io n o f School

Chi ldren (1972) ...................................... 50

G. Gunther, Cases and M ater ia ls

on C o n s t i t u t i o n a l Law

(9th Ed. 1975) ......................................... 26

W. Hawley, e t a l . , 1 Assessment

o f Current Knowledge About

The E f f e c t i v e n e s s o f School

D esegregat ion S t r a t e g i e s ,

S t r a t e g i e s f o r E f f e c t i v e

D e segrega t ion : A Synthes is

o f Findings (1981) 5 2 ,5 3 ,5 4

Page

Hawley, "The False Premises o f

Ant i -Bus ing L e g i s l a t i o n , "

test imony b e f o r e the Subcom.

on Separat ion o f Powers,

Sen. Com. on the J u d i c i a r y ,

97th Cong . , 1st Sess .

(September 30, 1981) ...................... 5 2 ,5 4 ,5 5

M e tro p o l i ta n Appl ied Research

Center , Busing Task Force

Fact Book ( 1 972 ) ................................... 49

The New York Times,

Dec. 4, 1980 .................................... 50

N at iona l A s s o c i a t i o n o f Motor

Bus Owners, Bus Facts (39th

ed. 1 972) .................................................. 50

G. O r f i e l d , Must We Bus? (1978) . . 49,50

C. R o s s e l l , e t a l . , 5 Assessment

o f Current Knowledge About

the E f f e c t i v e n e s s o f School

D esegregat ion S t r a t e g i e s ,

A Review o f the Empir ica l

Research on D e se g re ga t io n :

Community Response, Race

R e l a t i o n s , Academic A ch ie v e

ment and R esegreg a t ion (1981) . . 5 3 ,5 4 ,5 5

U.S. Commission on C i v i l R ig h t s ,

P u b l i c Knowledge and Busing

O p p o s i t io n (1973) ............................... 50

Z o l o t h , The Impact o f Busing on

Student Achievement, 7 Growth

& Change 45 (Ju ly 1976) ................. 51

- viii

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1981

No. 81-9

STATE OF WASHINGTON, e t a l . ,

A p p e l l a n t s ,

v.

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO.-1, e t a l . ,

A p p e l l e e s .

On Appeal From The United S ta te s Court

o f Appeals For The Ninth C i r c u i t

MOTION FOR LEAVE FOR THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

TO FILE A BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

The NAACP L e g a l D e fe n s e and Educa

t i o n a l Fund, I n c . , h e r e b y r e s p e c t f u l l y

moves f o r ~ l e a v e to f i l e the attached b r i e f

amicus cu r ia e in t h i s case . Counsel f o r

a p p e l l e e s , t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s , and t h e

S e a t t l e i n t e r v e n o r - p l a i n t i f f s - a p p e l l e e s

2

have c o n s e n t e d t o the f i l i n g o f th e a t

tached b r i e f . The consent o f the a t t o r n e y

f o r a p p e l la n t s was r e q u e s te d , but r e f u s e d ,

thus n e c e s s i t a t i n g t h i s moion.

1. The NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e and

Educat iona l Fund, I n c . , ( h e r e i n a f t e r "LDF")

i s a n o n - p r o f i t c o r p o r a t i o n e s t a b l i s h e d

under the laws o f the S ta te o f New York.

I t was formed to a s s i s t b la ck persons to

s ecure t h e i r c o n s t i t u t i o n a l r i g h t s by the

p r o s e c u t i o n o f l a w s u i t s . I t s c h a r t e r

d e c l a r e s that i t s purposes in c lu d e re n d e r

ing l e g a l s e r v i c e s g r a t u i t o u s l y t o b lack

persons s u f f e r i n g i n j u s t i c e by reason o f

r a c i a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n . LDF i s independent

o f o t h e r o r g a n i z a t i o n s and i s supported by

c o n t r i b u t i o n s from the p u b l i c .

2. For many y e a r s a t t o r n e y s o f th e

Legal Defense Fund have rep resen ted p a r

t i e s in l i t i g a t i o n b e f o r e t h i s Court and

3

th e l o w e r c o u r t s i n v o l v i n g a v a r i e t y o f

r a c e d i s c r i m i n a t i o n i s s u e s , i n c l u d i n g

la w s u i t s brought on b e h a l f o f b la ck parents

and s tudents t o d e seg rega te p u b l i c s c h o o l s .

E . g . , Brown v. Board o f E d u ca t io n , 347 U.S.

483 ( 1 9 5 4 ) ; C oop er v . A a r o n , 358 U .S . 1

(1 9 5 8 ) ; Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430 (1 9 6 8 ) ; Alexander v. Holmes County

Board o f E d u c a t i o n , 396 U .S . 19 ( 1 9 6 9 ) ;

Swann v. Char lo t te -M eck lenburg Board o f Ed

u c a t i o n , 402 U.S. 1 (1 9 7 1 ) ; Keyes v. School

D i s t r i c t No. 1 , 413 U.S. 189 ( 1 973) . The

Legal Defense Fund a l s o has p a r t i c i p a t e d as

amicus c u r i a e in numerous d e s e g r e g a t i o n

cases in t h i s Court. E . g . , Columbus Board

o f E d u c a t i o n v .__P e n i c k , 443 U . S . 449

(1 9 7 9 ) ; Regents o f the U n iv e r s i t y o f C a l i -

f o r n i a v . B a k k e , 4 38 U . S . 2 6 5 ( 1 9 7 8 ) .

4

3. Amicus a l s o r e p r e s e n t s b l a c k

p a r e n t s and s c h o o l c h i l d r e n in numerous

pending lower cou r t c a s e s . Those parents

and c h i l d r e n have a p a r t i c u l a r i n t e r e s t and

concern in encouraging l o c a l s c h o o l d i s

t r i c t s t o undertake v o lu n ta ry " a f f i r m a t i v e

a c t i o n " p r o g r a m s t o d e s e g r e g a t e t h e i r

s t u d e n t b o d i e s and f a c i l i t i e s w i t h o u t

undergoing f u l l - b l o w n l i t i g a t i o n , which i s

o f t e n t a x in g , t ime-consuming and e x p e n s iv e .

LDF a l s o has an i n t e r e s t in sa fegu a rd in g

the r i g h t o f b lack parents and o t h e r b lack

c i t i z e n s , as e x e r c i s e d h e r e , t o s e e k

re d re s s o f g r ie v a n ce s and t o o b t a in f a v o r

a b l e g o v e r n m e n t a l a c t i o n t h r o u g h t h e

p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s on the same b a s i s as a l l

o t h e r c i t i z e n s . As th e a t t a c h e d b r i e f

p o in t s o u t , amicus b e l i e v e s that both these

i n t e r e s t s w i l l be im per i led i f I n i t i v i v e

350 i s upheld.

5

4. Amicus r e s p e c t f u l l y submits that

i t s long e x p e r i e n ce in s c h o o l d e s e g r e g a t i o n

m a t t e r s and i t s f a m i l i a r i t y w i t h t h e

s o c i a l - s c i e n c e data on the su cce s s o f d e

s e g r e g a t i o n remedies may a s s i s t the Court

* /m r e s o l v i n g t h i s m a t t e r . -

^_/ The s o l e o b j e c t i o n o f a p p e l l a n t s '

cou n se l t o LDF's p a r t i c i p a t i o n as amicus —

that LDF's p e r s p e c t i v e i s rep resen ted here

by the S e a t t l e , Washington Branch o f the

N at ion a l A s s o c i a t i o n f o r the Advancement o f

C o l o r e d P e o p l e (NAACP), one o f s e v e r a l

p 1 a i n t i f f - i n t e r v e n o r s - - i s m i s t a k e n .

Although o r i g i n a l l y founded by the NAACP,

LDF has been a wholly separa te o r g a n i z a t i o n

from the NAACP f o r over 20 y e a r s , with a

s e p a r a t e Board o f D i r e c t o r s , program o f

o p e r a t i o n s , s t a f f , o f f i c e and b u d g e t .

Moreover, while the NAACP i s p a r t i c i p a t i n g

in t h i s case s o l e l y on b e h a l f o f i t s members

in S e a t t l e , Washington, LDF seeks t o p a r t i

c i p a t e in o rd e r t o rep resen t the i n t e r e s t s

o f i t s c l i e n t s in s c h o o l d e s e g r e g a t i o n

l i t i g a t i o n t h r o u g h o u t th e c o u n t r y . For

these re a s o n s , LDF has been perm itted to

p a r t i c i p a t e as amicus cu r ia e in cases in

which the NAACP was a l s o a m i c u s , e . g . ,

R e g e n t s o f the U n iv e r s i t y o f C a l i f o r n i a v .

Ba k ke , s u p r a , and i n c a s e s in w h i c h

NAACP a t t o r n e y s r e p r e s e n t e d one o f the

p a r t i e s , e . g . , Columbus Board o f Education

v. P e n i c k , s u p r a ; New York G a s l ig h t C lub ,

In c , v . Carey, 447 U.S. 54 (19 80 ) .

6

WHEREFORE, f o r the f o r e g o i n g re a s o n s ,

amicus c u r ia e NAACP Legal Defense and Edu

c a t i o n a l Fund, I n c . prays that the at tached

b r i e f be permitted t o be f i l e d .

R e s p e c t f u l l y s u b m i t t e d ,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, I I I

BILL LANN LEE*

JAMES S. LIEBMAN

Suite 2030

10 Columbus C i r c l e

New York, New York 10019

(212)586-8397

*Counsel o f Record

Attorneys f o r NAACP Legal

Defense & Educat iona l Fund,

as Amicus Curiae

QUESTION PRESENTED

Does I n i t i a t i v e 350 v i o l a t e the Four

teenth Amendment by s t r u c t u r i n g the p o l i t i

c a l p r o c e s s o f the Sta te o f Washington so

t h a t g o v e r n m e n t a l a c t i o n b e n e f i t i n g th e

m in o r i t y v i c t im s o f s c h o o l s e g r e g a t i o n i s

more d i f f i c u l t t o a ch ieve than governmental

a c t i o n b e n e f i t i n g a l l o t h e r c i t i z e n s ?

7

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1981

No. 81-9

STATE OF WASHINGTON, e t a l . ,

A p p e l l a n t s ,

v.

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, e t a l . ,

A p p e l l e e s .

On Appeal From The United S ta te s Court

o f Appeals For The Ninth C i r c u i t

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Amicus r e s p e c t f u l l y submits that t h i s

appeal i s governed by the fundamental Four

t e e n t h Amendment p r i n c i p l e t h a t a s t a t e

must maintain p o l i t i c a l n e u t r a l i t y among

the races and may not burden m in o r i t y -g r o u p

p o l i t i c a l p a r t i c i p a t i o n by r e q u i r i n g r a c i a l

8

m i n o r i t i e s to u t i l i z e more onerous means

than a l l o th e r c i t i z e n s to o b t a i n govern

mental a c t i o n on t h e i r b e h a lv e s . Hunter

v, E r i c k s o n , 393 U.S. 385 (1 9 6 9 ) ; Nyquist

v . L e e , 401 U.S. 935 ( 1 97 1 ) , a f f ' g 318

F. Supp. 710 (W.D.N.Y. 1 970) . The f a t a l

c o n s t i t u t i o n a l d e f e c t o f I n i t i a t i v e 350 i s

that i t i s a " s t a t u t e [] which s t r u c t u r e [ s ]

the in t e r n a l governmental p r o c e s s " in such

a way as to "make[] i t more d i f f i c u l t f o r

r a c i a l . . . m i n o r i t i e s " than f o r a l l o th e r

c i t i z e n s t o " f u r t h e r t h e i r p o l i t i c a l a im s . "

Hunter v . E r i c k s o n , s u p r a , 393 U.S. at 393

(Harlan, J. , c o n c u r r i n g ) . Because Hunter

and N y q u i s t v . Lee are d i s p o s i t i v e , we

l i m i t Part I o f t h i s b r i e f t o a d i s c u s s i o n

o f the a p p l i c a t i o n here o f the p r i n c i p l e

which animates those c a s e s .

Part I I b r i e f l y d i s c u s s e s the r e c e n t

s o c i a l s c i e n t i f i c data e s t a b l i s h i n g that

d e s e g r e g a t i o n o f p u b l i c s c h o o l s i s a

- 9 -

l e g i t i m a t e , in d e e d p r e s s i n g , p o l i t i c a l

g o a l o f m i n o r i t i e s , which has s u c c e e d e d

o v e r t h e p a s t f i f t e e n y e a r s i n d r a m a

t i c a l l y im p r o v in g a c a d e m ic a c h ie v e m e n t

among b lacks and race r e l a t i o n s among a l l

s t u d e n t s .

ARGUMENT

I

INITIATIVE 350 VIOLATES THE FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENT'S MOST BASIC

PROHIBITION BY STRUCTURING THE

POLITICAL PROCESS SO THAT GOVERN

MENTAL ACTION BENEFITING THE MINORITY

VICTIMS OF SCHOOL SEGREGATION IS MORE

DIFFICULT TO ACHIEVE THAN GOVERN

MENTAL ACTION BENEFITING ALL OTHER

CITIZENS

In i t s most fu n d a m en ta l a s p e c t , th e

Equal P r o t e c t i o n Clause o f the Fourteenth

Amendment f o r b i d s the Sta tes from p ass in g

laws, not born o f a com pe l l ing n e c e s s i t y ,

t h a t c l a s s i f y b l a c k s o r o t h e r r a c i a l

m i n o r i t i e s d i f f e r e n t l y , and l e s s a d -

10

v a n t a g e o u s l y , than a l l o t h e r c i t i z e n s ,

S 1 a u g h t e r h o u s e C a s e s , 83 U . S . 3 6 , 71

( 1 8 7 3 ) ; S t r a u d e r v . West V i r g i n i a , 100

U .S . 303 , 3 07 -0 8 ( 1 8 8 0 ) ; Ex p a r t e V i r

g i n i a , 100 U . S . 3 3 9 , 3 4 4 - 4 5 ( 1 8 8 0 ) ;

B o l l i n g v . S h a r p e , 347 U .S . 499 ( 1 9 5 4 ) ;

McLaughlin v . F l o r i d a , 379 U.S. 184, 192

(1 9 6 4 ) ; Loving v. V i r g i n i a , 388 U.S. 1, 10

(1 9 6 7 ) . This deep m is t r u s t o f l e g i s l a t i v e

c l a s s i f i c a t i o n s s i n g l i n g o u t b l a c k s o r

o t h e r r a c i a l m i n o r i t i e s d e r iv e s from a r e

c o g n i t i o n that " p r e j u d i c e a g a in s t d i s c r e t e

and i n s u l a r m i n o r i t i e s " in t h i s c o u n t r y

h i s t o r i c a l l y has been "a s p e c i a l c o n d i -

d i t i o n , which tends s e r i o u s l y t o c u r t a i l

t h e o p e r a t i o n o f t h o s e p o l i t i c a l p r o

c e s s e s o r d i n a r i l y t o be r e l i e d upon t o

p r o t e c t m i n o r i t i e s . . . . " U n i te d S t a t e s

v . C a r o l e n e P r o d u c t s C o . , 304 U .S . 144,

152 n .4 ( 1 9 3 8 ) . B ecau se th e C la u s e was

des igned as an a n t id o t e to the " p o s i t i o n

o f p o l i t i c a l p o w e r l e s s n e s s . . . [ i n ] th e

m a j o r i t a r ia n p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s " to which

b l a c k s and o t h e r r a c i a l m i n o r i t i e s have

b e e n r e l e g a t e d i n t h i s c o u n t r y , 53an

A n t o n i o S c h o o l D i s t . v . R o d r i q u e z , 411

1/CJ.S. 1 , 28 ( 1 973 ) , i t s p r o h i b i t o r y f o r c e

f a l l s h e a v i l y , perhaps most h e a v i l y , on

" laws which d e f in e the s t r u c t u r e o f p o l i

t i c a l i n s t i t u t i o n s " s o as t o c l a s s i f y

r a c i a l m i n o r i t i e s l e s s advantageously than

a l l o t h e r c i t i z e n s . Hunter v . E r i c k s o n ,

393 U.S. 385, 393 (1969) (Harlan, J . , con

c u r r i n g ) ; see Mobile v . B o ld e n , 446 U.S.

55 , 8 3 -8 4 (1 9 80 ) ( S t e v e n s , J . , c o n c u r

r i n g ) ; s e e e . g . , White v . R e g e s t e r , 412

U .S . 755 ( 1 9 7 3 ) ; Nixon v . H e r n d o n , 273

U.S. 536 (1927 ) .

J_/ See Fo ley v , C o n n e l i e , 435 U.S. 291,

294 (1 9 78 ) ; Massachusetts Board o f R e t i r e -

ment v . Murgia, 427 U.S. 307, 313 ( 1 976) ;

In re G r i f f i t h s , 413 U.S. 717, 721 (1 973) ;

Takahashi v . Fish and Game Comm'n, 334 U.S.

410, 420 (1948 ) .

12

A. R a c ia l C l a s s i f i c a t i o n s D i s t o r t i n g

the P o l i t i c a l Process

Forbidden r a c i a l c l a s s i f i c a t i o n s im

p in g in g on the p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s in c l u d e ,

f o r example, the simple d e n ia l t o b la ck s

and o th e r r a c i a l m i n o r i t i e s o f the f r a n

c h i s e a v a i l a b l e t o a l l o t h e r c i t i z e n s . C f .

Dunn v . B l u m s t e i n , 405 U .S . 330 ( 1 9 7 2 ) ;

Harper v . V i r g i n i a Board o f E l e c t o r s , 383

2/U.S. 663 (1966 ) .

S i m i l a r l y r i t i s fu n d a m e n ta l t o th e

Equal P r o t e c t i o n C la u s e t h a t th e S t a t e s

may not un favorab ly s i n g l e out b la ck s o r

o t h e r m i n o r i t i e s in th e p o l i t i c a l arena

by weight ing t h e i r v o te s l e s s h e a v i l y than

2 / Such a c l a s s i f i c a t i o n i s no l e s s

o b n o x i o u s t o t h e F o u r t e e n t h Amendment

b e c a u s e i t d i s a d v a n t a g e s o n l y ' some mem

bers o f a r a c i a l m in o r i ty - - f o r example,

by d e p r iv in g o n ly b la ck s who wish t o vo te

in th e D e m o c r a t i c P a r t y p r im a r y o f th e

a b i l i t y t o do so . E. g , White v . R e g e s t e r ,

s u p r a ; Nixon v . Herndon, s u p r a .

13

t h e v o t e s o f a l l o t h e r p e r s o n s — f o r

e x a m p l e , by a f f o r d i n g b l a c k s o n l y o n e

r e p r e s e n t a t i v e f o r every 10,000 c i t i z e n s ,

whi le a f f o r d i n g o th e rs one r e p r e s e n t a t i v e

f o r e v e r y 5 ,0 0 0 c i t i z e n s . Cf_. A very v .

3 /

Mid land C o u n t y , 390 U.S . 474 ( 1 9 6 8 ) . “

F i n a l l y , even where b la ck s and o t h e r

m i n o r i t i e s are al lowed the f r a n c h i s e and

r e p r e s e n t a t i o n e q u a l t o t h a t a f f o r d e d

o t h e r c i t i z e n s , t h i s Court has re co gn iz e d

t h a t t h e S t a t e s o f f e n d t h e F o u r t e e n t h

Amendment 's fu n d a m en ta l r e q u i r e m e n t o f

p o l i t i c a l n e u t r a l i t y among the races when

t h e y p a ss " s t a t u t e s which s t r u c t u r e the

i n t e r n a l g o v e r n m e n t a l p r o c e s s " s o as t o

"make[] i t more d i f f i c u l t f o r r a c i a l and

r e l i g i o u s m i n o r i t i e s [than f o r the r e s t o f

3 / Again, such a c l a s s i f i c a t i o n v i o l a t e s

the Fourteenth Amendment even i f i t does

n o t v i c t i m i z e a l l b l a c k s but o n l y , f o r

e x a m p le , b l a c k s l i v i n q in urban a r e a s .

C f . Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964 ) .

14 -

the c i t i z e n r y ] t o fu r t h e r t h e i r p o l i t i c a l

a im s . " Hunter v. E r i c k s o n , s u p r a , 393 U.S.

at 393 (Harlan, J. , c o n c u r r in g ) (emphasis

added) . For m in o r i ty c i t i z e n s are no l e s s

p o l i t i c a l l y pow er less with the vo te than

without i t i f the S ta te has arranged the

i n t e r n a l mechanics o f government so that

l e g i t i m a t e s t a t e a c t i o n b e n e f i t i n g r a c i a l

m i n o r i t i e s i s s t r u c t u r a l l y more d i f f i c u l t

t o a c h i e v e than s t a t e a c t i o n b e n e f i t i n g

o t h e r c o n s t i t u e n c i e s . See Mobile v. B o l

den , s u p r a , 446 U.S. at 83-84 (S te v e n s , J . ,

c o n c u r r i n g ) .

In t h i s l i g h t , f o r e x a m p le , a s t a t e

law r e q u i r i n q a t w o - t h i r d s m a j o r i t y f o r

l e g i s l a t i o n b e n e f i t i n g b l a c k s , where a

s i m p l e m a j o r i t y s u f f i c e s f o r a l l o t h e r

l e g i s l a t i o n , would c l e a r l y f a l l a f o u l o f

the Fourteenth Amendment. So, t o o , would

a s t a t e law s i n g l i n g out o n ly some b l a c k s ,

o r some s u b s t a n t iv e area o f governmental

15

b e n e f i t o f p a r t i c u l a r i n t e r e s t t o some

b l a c k s , f o r d isadvantageous treatment in

the p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s . Such was the h o ld

ing o f Hunter v. E r i c k s o n , s u p r a .

B. Hunter v. Erickson

In Hunter th e m u n i c i p a l lawmaking

p r o c e s s in Akron , Ohio had in th e p a s t

been s t ru c tu re d so that the C i ty Counci l

c o u l d a d o p t any m u n i c i p a l o r d i n a n c e r e

l a t i n g t o a l e g i t i m a t e g o a l o f l o c a l

government — i n c l u d i n g , f o r example, the

r e g u l a t i o n o f r e a l - p r o p e r t y t r a n s a c t i o n s

— by a m a j o r i t y v o t e , s u b j e c t t o a c i t i

z e n s ' v e t o i f ( i ) 10 p ercen t o f the e l e c

t o r a t e s i g n e d a p e t i t i o n c a l l i n g f o r a

r e f e re n d u m on the o r d i n a n c e , and ( i i ) a

m a j o r i t y o f the C i t y ' s e l e c t o r a t e t h e r e

a f t e r d i s a p p r o v e d t h e o r d i n a n c e i n a

g e n e r a l e l e c t i o n . See 393 U .S . a t 387;

i d . a t 3 9 3 -9 4 (H a r l a n , J . , c o n c u r r i n g ) .

1 6

H_u nj: e r i n v o l v e d a c o n s t i t u t i o n a l

c h a l l e n g e t o a c i t y - c h a r t e r amendment,

l e g i s l a t e d by referendum, that p a r t i a l l y

r e a r r a n g e d t h i s s t r u c t u r e . U n d er t h e

amendment, " [ a ] n y o r d i n a n c e which r e g u

l a t e [d] th e u s e , s a l e [ o r ] l e a s e . . . o f

r e a l p r o p e r t y o f any kind . . . on the b a s i s

o f r a c e , c o l o r , r e l i g i o n , n a t i o n a l o r i g i n

o r a n c e s t r y " n ot o n l y had t o s e c u r e th e

v o te s o f a m a jo r i t y o f the C i t y C o u n c i l ,

but a l s o had t o "be approved by a m a j o r i t y

o f the e l e c t o r s v o t i n g on the q u e s t i o n at

a r e g u la r or gen era l e l e c t i o n . . . . " Ic3. at

387 . A l l o t h e r m u n i c i p a l laws - - i . e . ,

o r d i n a n c e s n o t r e g u l a t i n g t h e s a l e o r

l e a s e o f r e a l p r o p e r t y , and t h o s e r e g u

l a t i n g the s a l e o r l e a s e o f r e a l p r o p e r t y

on some b a s i s o t h e r than race - - remained

s u b j e c t to the p r e e x i s t i n g , l e s s onerous

l e g i s l a t i v e p r o c e s s .

1 7

The C o u r t h e l d t h a t t h e c h a r t e r

amendment v i o l a t e d the Fourteenth Amend

ment. In so d o in g , both J u s t i c e White f o r

th e C ou r t and J u s t i c e Har lan in c o n c u r

rence noted that the c h a r t e r amendment ( i )

was d e s i g n e d t o r e s c i n d a f a i r - h o u s i n g

o r d i n a n c e p a s s e d by th e C i t y C o u n c i l in

o r d e r t o r e l i e v e r a c i a l and r e l i g i o u s

m i n o r i t i e s o f housing d i s c r i m i n a t i o n , and

( i i ) served to make the passage o f muni

c i p a l l e g i s l a t i o n by the C i t y C ounc i l more

d i f f i c u l t in the f u t u r e by p l a c i n g more

power d i r e c t l y in the hands o f the e l e c

t o r a t e , and l e s s in the hands o f the c i t y

government. But, as J u s t i c e H ar lan 's con

c u r r e n c e makes e x p l i c i t , i t was n e i t h e r

o f t h e s e f a c t s a l o n e t h a t r e n d e r e d th e

4 /

amendment u n c o n s t i t u t i o n a l . - Rather , the

4 / In the f i r s t p l a c e , that b la ck s and

r e l i g i o u s m i n o r i t i e s had u t i l i z e d t h e

18

law was u n c o n s t i t u t i o n a l becau se , by way

_4/ cont inued

p r e - e x i s t i n g p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s to b e n e f i t

t h e m s e l v e s by e x t e n d i n g t h e i r s t a t u t o r y

c i v i l r i g h t s beyond what f e d e r a l law r e

q u i r e d d id n o t r e n d e r u n c o n s t i t u t i o n a l

the subsequent r e s c i s s i o n o f that a c t i o n

t h r o u g h e x e r c i s e o f t h e same g e n e r a l

p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s :

S t a t u t e s . . . which a r e g rou n d ed

upon g e n e r a l d e m o c r a t i c p r i n

c i p l e , do n o t v i o l a t e th e Equal

P r o t e c t i o n Clause simply because

t h e y o c c a s i o n a l l y o p e r a t e t o

d i s a d v a n t a g e N e g r o p o l i t i c a l

i n t e r e s t s . I f a g o v e r n m e n t a l

i n s t i t u t i o n i s t o be f a i r , one

g r o u p c a n n o t a lw ays be e x p e c t e d

t o w i n . I f t h e [ A k r o n C i t y ]

C o u n c i l ' s f a i r h o u s i n g l e g i s

l a t i o n were d e fe a te d at a r e f e r

endum, Negroes would undoubtedly

l o s e an i m p o r t a n t p o l i t i c a l

b a t t l e , but they would not thereby

b e d e n i e d e q u a l p r o t e c t i o n .

Hunter v . E r i c k s o n , s u p r a , 393 U.S. at 394

(Harlan, J . , c o n c u r r i n g ) . A cco rd , i d . at

390 n .5 ( m a j o r i t y o p i n i o n ) . See Dayton

Board o f Education v. Brinkman, 4 33 U.S.

406 , 4 1 3 -1 4 (1 9 7 7 ) ( s c h o o l b o a r d ' s r e s

c i s s i o n o f a p r i o r b o a r d ' s r e s o l u t i o n

19

o f a nonneutral s u b j e c t - m a t t e r c l a s s i f i c a

t i o n , i t r e q u i r e d m i n o r i t i e s s e e k i n g

l e g i s l a t i v e p r o t e c t i o n from housing d i s

c r i m i n a t i o n t o s u r m o u n t a r e f e r e n d u m

hurd le that s tood in the way o f no o th e r

4 / cont inued

i n i t i a t i n g a f f i r m a t i v e a c t i o n to undo de

f.£ c t_ o s e g r e g a t i o n d o e s n o t by i t s e F f

v i o l a t e the Fourteenth Amendment).

S i m i l a r l y , w e re a s t a t e o r l o c a l

g o v e r n m e n t t o o r g a n i z e i t s e l f s o t h a t

l e g i s l a t i o n , o r even some r a c i a l l y n eu tra l

s p e c i e s o f l e g i s l a t i o n — say that regu

l a t i n g a l l r e a l e s t a t e t r a n s a c t i o n s — i s

always d i f f i c u l t to p ass , such a govern

m en ta l s t r u c t u r e would not n e c e s s a r i l y

v i o l a t e the C o n s t i t u t i o n even though i t

might have the e f f e c t o f hampering e f f o r t s

by b la ck s t o pass f a i r - h o u s i n g l e g i s l a t i o n .

Such a r u le

o b v i o u s l y d o e s n o t h a v e t h e

p u r p o s e o f p r o t e c t i n g one p a r

t i c u l a r g r o u p t o t h e d e t r i

ment o f a l l o t h e r s . I t w i l l

s o m e t i m e s o p e r a t e in f a v o r o f

one f a c t i o n , sometimes in fa v o r o f

another .

Hunter v. E r i c k s o n , 393 U.S. at 394 (Harlan

J . , c o n c u r r i n g ) .

- 20

g e n e r a l , o r even h o u s i n g - r e l a t e d , l e g i s -

5 /

l a t i o n .

5 / N ota b ly , the Akron law s t ru ck down in

Hunter was f a c i a l l y n e u t r a l , s i n c e i t sub

j e c t e d ord in a n ces r e g u l a t i n g r e a l e s t a t e

t r a n s a c t i o n s "on the b a s i s o f r a c e " t o the

same b e f o r e - t h e - f a c t referendum r e q u i r e

ment w h e t h e r t h e y b e n e f i t e d w h i t e s o r

b l a c k s . The C o u r t c o n c l u d e d , h o w e v e r ,

t h a t th e l a w ' s f a c i a l n e u t r a l i t y was a

t r a n s p a r e n t d i s g u i s e f o r a n o n n e u t r a l

c l a s s i f i c a t i o n drawn p u r e l y and c l e a r l y

a long r a c i a l l i n e s :

[ A j l t h o u g h th e law on i t s f a c e

t r e a t s Negro and w h ite , Jew and

g e n t i l e in an i d e n t i c a l manner,

th e r e a l i t y i s t h a t th e l a w ' s

im pact f a l l s on the m i n o r i t y .

The m a j o r i t y needs no p r o t e c t i o n

a g a i n s t d i s c r i m i n a t i o n and i f

i t d i d , a re f e re n d u m m ight be

b o t h e r s o m e b u t no m ore t h a n

t h a t . L i k e t h e law r e q u i r i n g

s p e c i f i c a t i o n o f c a n d i d a t e s '

ra ce on the b a l l o t , Anderson v.

M a r t i n , 375 U . S . 399 ( 1 9 6 4 ) ,

[ t h e Akron c h a r t e r amendment]

p l a c e s s p e c i a l burdens on r a c i a l

m i n o r i t i e s w i t h i n th e g o v e r n

mental p r o c e s s . This i s no more

p e r m i s s i b l e than d e n y in g them

the vo te on an equal b a s i s with

o t h e r s . The p r e a m b l e t o t h e

open h o u s in g l e g i s l a t i o n which

was su spen ded by [ t h e c h a r t e r

amendment] . . . r e c i t e d t h a t

the p o p u la t i o n o f Akron c o n s i s t s

21

Because " the c i t y o f Akron ha[d] not

attempted t o a l l o c a t e governmental power

5 / cont inued

o f " p e o p l e o f d i f f e r e n t r a c e ,

c o l o r , r e l i g i o n , a n c e s t r y o r

n a t i o n a l o r i g i n , many o f whom

l i v e in c i r cu m scr ib ed and s e g r e

gated a re a s , under substandard,

u n h e a l t h fu l , unsa fe , unsanitary

and o v e r c r o w d e d c o n d i t i o n s ,

because o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n in the

s a l e , l e a s e , r e n t a l and f i n a n

c i n g o f h o u s i n g . " Such was

the^ s i t u a t i o n in Akron . I t i s

a g a in s t t h i s background that the

r e f e r e n d u m r e q u i r e d by [ t h e

c h a r t e r amendment] . . . must be

a s s e s s e d .

Hunter v. E r i c kson, supra, 393 U.S. at 391

( c i t a t i o n s o m i t t e d ) .

S i n c e the c l a s s i f i c a t i o n c o v e r t l y

drawn by the law was based upon race (as

w e l l as e t h n i c i t y and r e l i g i o n ) a l o n e , and

was not j u s t i f i e d by a com p e l l in g n e c e s

s i t y , the Court concluded that i t v i o l a t e d

the Equal P r o t e c t i o n Clause without r e f e r

ence to the Akron e l e c t o r a t e ' s m o t iv a t io n

f o r drawing i t . Id . at 389 ("we need not

r e s t on [ t h e C o u r t ' s i n v i d i o u s - p u r p o s e

ca ses ] t o d e c id e t h i s ca se . Here, u n l ike

[ in those c a s e s ] , there was an e x p l i c i t l y

r a c i a l c l a s s i f i c a t i o n t r e a t i n g r a c i a l

h o u s i n g m a t t e r s d i f f e r e n t f r o m o t h e r

r a c i a l and housing m a t t e r s " ) ; i d . at 395

(H a r l a n , J . , c o n c u r r i n g ) . As ~ th e C ourt

22

on th e b a s i s o f any g e n e r a l p r i n c i p l e , "

Hunter v . E r i c k s o n , s u p r a , 393 U.S. at 394

( H a r l a n , J . , c o n c u r r i n g ) , o r t o p r o v i d e

"a p o l i t i c a l s t r u c t u r e t h a t t r e a t s a l l

i n d i v i d u a l s as e q u a l s , " Mobile v . B o ld e n ,

s u p r a , 446 U.S. at 84 (S te v e n s , J . , c on

c u r r i n g ) , but ins tead passed "a p r o v i s i o n

that ha[d] the c l e a r purpose o f making i t

m ore d i f f i c u l t f o r c e r t a i n r a c i a l and

r e l i g i o u s m i n o r i t i e s t o a ch ieve l e g i s l a

t i o n t h a t i s i n t h e i r i n t e r e s t , " t h e

c h a r t e r amendment v i o l a t e d the Fourteenth

Amendment in the absence o f a com p e l l in g

j u s t i f i c a t i o n . Hunter v . E r i c k s o n , 393

U . S . a t 394 ( H a r l a n , J . , c o n c u r r i n g ) .

5 / cont inued

su bsequ en t ly r e i t e r a t e d in Personnel Ad

m i n i s t r a t o r v . F e e n e y , 442 U .S . 2 5 6 , 274

( 1 9 7 9 ) , i t i s on ly " [ i j f the c l a s s i f i c a

t i o n i t s e l f , c o v e r t o r o v e r t , i s not based

upon [ r a c e ] " t h a t th e c o u r t s must r e a ch

" t h e s e c o n d q u e s t i o n . . . w h e t h e r t h e

adverse E f f e c t r e f l e c t s in v i d i o u s [ r a c e - ]

b ased d i s c r i m i n a t i o n " (em p h a s is a d d e d ) .

23

Hunter e s t a b l i s h e d t h a t , whi le mem

bers o f the p o l i t i c a l m a jo r i t y are f r e e

t o ( i ) u t i l i z e g o v e r n m e n t a l p r o c e s s e s

org an ized a long a "ge n e ra l p r i n c i p l e " t o

r e s c i n d s t a t e a c t i o n b e n e f i t i n g r a c i a l

• v 1/m i n o r i t i e s , and ( 1 1 ) t o s u b j e c t them

s e l v e s and a l l o t h e r s , in c lu d in g r a c i a l

6 / Of c o u r s e , the i n v i d i o u s l y motivated

r e s c i s s i o n o f a p r i o r b e n e f i t t o minor

i t i e s does v i o l a t e the C o n s t i t u t i o n . Such

i s the case o f P r o p o s i t i o n 1 in C a l i f o r n i a .

S e e C r a wf o r d v . Board o f E d u c a t i o n o f

t h e C i t y o f Los A n g e l e s , No. 8 1 - 3 8 .

S i m i l a r l y , s t a t e and l o c a l g o v e r n

ments g u i l t y o f p r i o r r a c i a l d i s c r i m i n a

t i o n have a c o n t in u in g a f f i r m a t i v e duty t o

remedy i t s consequences and a c c o r d i n g l y

are not c o n s t i t u t i o n a l l y f r e e to withdraw

r i g h t s o r b e n e f i t s s e rv in g that remedial

purpose . E . g . , Columbus Board o f Educa

t i o n v . P e n icF , 443 U.S. 449, 459 (1979 ) ;

Wright v . Counci l o f the C i ty o f Emporia,

4 07 U.S. 451 ( 1 972) . In advance o f Phase

I I o f the presen t l i t i g a t i o n , we assume

f o r purposes o f argument that n e i t h e r the

S ta te o f Washington, nor any o f the o t h e r

munic ipa l governments in v o lv e d , i s g u i l t y

o f p r i o r r a c i a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n .

N o t a b l y , a f i n d i n g t h a t I n i t i a t i v e

350 i s u n c o n s t i t u t i o n a l would p r o b a b l y

r e m o v e any h e e d F o r P h a s e I I , s i n c e

24

m i n o r i t i e s , t o an a r d u o u s p r o c e s s o f

s e c u r in g l e g i s l a t i o n o r o t h e r governmental

a c t i o n b e n e f i c i a l t o th em se lves , in c l u d i n g

by r e a rra n g in g governmental power so that

more o f i t r e s i d e s at one l e v e l ( e . g . ,

with the e l e c t o r a t e ) and l e s s at another

( e . g . , with l o c a l governmental o f f i c i a l s ) ,

members o f the m a j o r i t y may not pass a law

d e p r i v i n g r a c i a l m i n o r i t i e s o f the bene

f i t s o f the p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s by s u b j e c t

i n g m i n o r i t i e s , b u t n o t t h e m s e l v e s ,

t o s t r u c t u r a l o r o t h e r p o l i t i c a l d i s

a b i l i t i e s . Such a law i s not "grounded in

6 / cont inued

S e a t t l e ' s v o l u n t a r i l y adopted d e se g re g a

t i o n p lan moots any need f o r c o u r t - o r d e r e d

measures. On the o t h e r hand, under Penick

and W r ig h t , s u p r a , I n i t i a t i v e 350 cannot

f i n a l l y be adjudged c o n s t i t u t i o n a l u n t i l

a f t e r Phase I I determines whether ( i ) the

S ta te o f Washington o r S e a t t l e i s under a

c o n t in u in g duty t o d e se g re g a te the s c h o o l s

o f S e a t t l e , and ( i i ) whether the I n i t i a

t i v e i n t e r f e r e s with that duty . See North

C a ro l in a Sta te Board o f Education v . Swann,

402 U.S. 43 (1971 ) .

25

in n e u tra l p r i n c i p l e . " Hunter v. E r i c k s o n ,

393 U.S. at 395 (Harlan, J. , c o n c u r r i n g ) .

By d i v i d i n g the p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s a long

r a c i a l l i n e s , i t cements i n t o th e p o

l i t i c a l s t r u c t u r e o f the S ta te the same

" s p e c i a l c o n d i t i o n " — i . e . , a " p r e j u d i c e

a g a in s t d i s c r e t e and in s u la r m i n o r i t i e s

. . . which tends t o c u r t a i l the o p e r a t i o n

o f the p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s o r d i n a r i l y t o be

r e l i e d upon t o p r o t e c t m i n o r i t i e s , " United

S t a t e s v . C a r o l e n e P roducts Co. , s u p r a ,

304 U .S . a t 152 n .4 — whose e x i s t e n c e

j u s t i f i e s t h e F o u r t e e n t h A m e n d m e n t ' s

" e x t r a o r d i n a r y p r o t e c t i o n " o f b la ck s and

o t h e r m i n o r i t i e s " from the m a j o r i t a r ia n

p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s . " San Antonio School

D i s t . v . R o d r i q u e z , s u p r a , 411 U .S . a t

28.

The requirement that s t a t e p o l i t i c a l

p r o c e s s e s be r a c i a l l y n e u t r a l i s no

Fourteenth Amendment f e l l o w t r a v e l e r . I t

26

i s c o m p e l l e d by th e same " b a s i c p r i n

c i p l e s , " Hunter v. E r i c k s o n , 393 U.S. at

396 (Harlan, J . , c o n c u r r i n g ) , l y i n g at the

" c o r e o f the Fourteenth Amendment," ic3. at

391 ( m a j o r i t y o p i n i o n ) , th a t demand that

r a c i a l m i n o r i t i e s be a f f o r d e d t h e same

r i g h t t o v o t e , and t h e same l e v e l o f

p o l i t i c a l r e p r e s e n t a t i o n , as a l l o t h e r

c i t i z e n s . S e e G. GUNTHER, CASES AND

MATERIALS ON CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 691-707

(9th Ed. 1975). Whatever o t h e r g o a l s the

Equal P r o t e c t i o n C la u s e i s d e s i g n e d t o

a c h i e v e , at the very l e a s t i t demands " the

p r e v e n t i o n o f meaningful and u n j u s t i f i e d

o f f i c i a l d i s t i n c t i o n s based on r a c e , " and

p a r t i c u l a r l y those d i s t i n c t i o n s d isadvan

ta g in g r a c i a l m i n o r i t i e s in the p o l i t i c a l

p r o c e s s . Hunter v. E r i ck s o n , s u p r a , 393

U.S at 391.

71

C. Nyquist v. Lee

In N y q u i s t v . L e e , 401 U. S . 935

(1 9 7 1 ) , a f f 'g 318 F. Supp. 710 (W.D. N.Y.

1970) , the Court re a f f i rm e d th ese p r i n

c i p l e s in a c o n t e x t in v o lv in g the uneven,

s u b j e c t - m a t t e r - s p e c i f i c r e a l i g n m e n t o f

p o l i t i c a l power - - n o t , as in H u n t e r ,

between l o c a l munic ipal o f f i c i a l s and the

e l e c t o r a t e , but between s t a t e and l o c a l

p u b l i c - s c h o o l o f f i c i a l s .

In New York (u n l ik e in most American

s t a t e s , see M i l l ik e n v. B r a d le y , 418 U.S.

717, 742 & n.20 ( 1 9 7 4 ) ) , a u t h o r i t y over

t h e p u b l i c s c h o o l s l a r g e l y b e l o n g s t o

s t a t e , r a t h e r t h a n l o c a l , e d u c a t i o n

o f f i c i a l s . Thus, the Board o f Regents o f

the U n iv e r s i t y o f the State o f New York,

and i t s c h i e f e x e c u t i v e o f f i c e r , t h e

Commissioner o f Educat ion , have long had

" t h e a u t h o r i t y t o o r d e r l o c a l s c h o o l

b o a r d s t o a c t in a c c o r d a n c e w i th s t a t e

28

e d u c a t i o n a l p o l i c i e s f o r m u l a t e d by th e

Board o f R e g e n ts . " Lee v . N y q u i s t , 318

F.Supp. at 719. As in Hunter, with regard

t o housing in Akron, the r a c i a l m i n o r i t i e s

b e f o r e the Court in Lee had succeeded in

the past in co n v in c in g th ese o f f i c i a l s t o

adopt "a p o l i c y o f e r a d i c a t i n g de f a c t o

s e g r e g a t i o n " in the p u b l i c s c h o o l s o f New

7 /

York. 3!d̂ at 716. D esp i te " c o n s i d e r a b l e

l o c a l r e s i s t a n c e , " the Regents and Commis

s i o n e r o f Education e n fo r ce d t h i s p o l i c y

by o r d e r i n g l o c a l s c h o o l b o a r d s t o r e

a ss ig n s tudents to assure r a c i a l ba lance

in the s c h o o l s . Id .

7 / " [ S j c h o o l a u t h o r i t i e s have wide d i s

c r e t i o n in fo rm u la t in g s c h o o l p o l i c y , and

. . . as a matter o f e d u c a t i o n a l p o l i c y . . .

may w e l l con c lu d e that some kind o f r a c i a l

ba lance in the s c h o o l s i s d e s i r a b l e q u i t e

a p a r t from any c o n s t i t u t i o n a l r e q u i r e

m ents . " North C aro l in a Board o f Education

v . Swann, 402 U.S. 31, 45 (1 9 7 1 ) ; a c c o r d ,

Swann v . C h a r l o t t e - M e c k l e n b u r g Board o f

E ducat ion , 402 U.S. 1, 16 (1 9 71 ) .

29

The opponents o f mandatory d e s e g re g a

t i o n in New York secured l e g i s l a t i o n r e s

c in d in g such o r d e r s . As in Hunter, how

e v e r , t h i s goa l was not accomplished by

simply r e v e r s in g the same p o l i t i c a l p r o

c e s s that m i n o r i t i e s had p r e v i o u s l y used

t o secure s ta te - im posed a n t i - s e g r e g a t i v e

m e a s u r e s . N o r was i t a c c o m p l i s h e d by

g e n e r a l l y r e a r r a n g i n g t h e p o l i t i c a l

p r o c e s s t o make a c t i o n by s t a t e ed u ca t ion

o f f i c i a l s , in c lu d in g a c t i o n b e n e f i c i a l t o

the v i c t im s o f de f a c t o s e g r e g a t i o n , more

d i f f i c u l t t o a c h i e v e , f o r i n s t a n c e by

f o r c i n g s t a t e o f f i c i a l s g e n e r a l l y t o share

a u t h o r i t y with l o c a l ones .

In s te ad , as in Hunter, the opponents

o f s tate-mandated d e s e g r e g a t io n adopted a

s u b j e c t - m a t t e r - s p e c i f i c law p r o v id in g that

any a c t i o n regarding student assignment

" o n a c c o u n t o f r a c e , c r e e d , c o l o r o r

30

n a t i o n a l o r i g i n " would r e q u i r e , in a d d i

t i o n t o the approval o f s t a t e o f f i c i a l s ,

" the express approval o f a [ l o c a l ] board

o f e d u c a t i o n h a v i n g j u r i s d i c t i o n , a

m a j o r i t y o f th e members o f such b o a r d

8 /

h a v i n g b e e n e l e c t e d . . . . " — Lee v .

8/ As in Hunter , the law s t r u c k down in

Lee on i t s f a c e was r a c i a l l y n e u t r a l ,

s i n c e r a c e - c o n s c i o u s r e a s s i g n m e n t o f

s tudents t o b e n e f i t whites was s u b je c t e d

t o the same s p e c i a l hurd les as r e a s s i g n

ment t o b e n e f i t b la c k s . However, as in

Hunter , see note 5, s u p r a , the Lee Court

r e c o g n i z e d , g iven the s t a t u t e ' s g e n e s i s in

" l o c a l r e s i s t a n c e " t o p a s t i n t e g r a t i v e

s tuden t -ass ign m en t p la n s , that the s t a t u t e

e f f e c t i v e l y embodied an " e x p l i c i t l y r a c i a l

c l a s s i f i c a t i o n " a f f o r d i n g the e d u c a t i o n a l

i n t e r e s t s o f the b lack v i c t im s o f de f a c t o

s e g r e g a t i o n l e s s fa v o r a b le treatment than

th e e d u c a t i o n a l i n t e r e s t s o f a l l o t h e r

c i t i z e n s . Lee v . N y g u i s t , s u p r a , 318

F. Supp. at 718. As in Hunter, the law

was a c c o r d i n g l y h e ld u n c o n s t i t u t i o n a l

i r r e s p e c t i v e o f th e m o t i v a t i o n o f i t s

p ropon en ts . Id .

In view o f L e e , and the o t h e r cases

a p p l y i n g Hunter in s c h o o l - s e g r e g a t i o n

c o n t e x t s , e . g . , Evans v . B u ch an an , 393

F. Supp. 428 , 4 4 0 -4 1 ( D. D e l . ) ( 3 - j u d g e

c o u r t ) , a f f ' d , 423 U.S. 963 ( 1 9 7 5 ) ( c i t i n g

c a s e s ) , the Government 's s u g g e s t i o n that

31

N y q u i s t , s u p r a , 318 F.Supp. at 712. While

g i v i n g l o c a l o f f i c i a l s a u t h o r i t y over t h i s

8/ cont inued

t h e F o u r t e e n t h Amendment p r o h i b i t i o n

e n u n c i a t e d in Hunter i s l i m i t e d t o non

n e u t r a l l a w s d i s c o u r a g i n g e f f o r t s t o

end de f a c t o housing s e g r e g a t i o n , and does

not apply to nonneutral laws d i s c o u r a g in g

e f f o r t s t o end de f a c t o s c h o o l s e g r e g a

t i o n , i s l u d i c r o u s . E. g . , B r i e f o f the

U n i te d S t a t e s , a t 1 7 - 1 8 . See g e n e r a l l y

Columbus Board o f Education v. P e n i c k , 443

U .S . 449 , 465 n .1 3 ( 1 9 7 9 ) ( c i t i n g c a s e s )

( n o t i n g th e h a n d - i n - g l o v e r e l a t i o n s h i p

between housing and s ch o o l s e g r e g a t i o n ) .

Indeed, the c h a r a c t e r i s t i c o f e f f o r t s

t o end de f a c t o s c h o o l s e g r e g a t i o n on

which the Government r e l i e s to d i s t i n g u i s h

t h i s c a s e from Hunter — i . e . , t h a t some

m i n o r i t i e s may n o t be b e n e f i t e d by such

measures, B r i e f o f the United S t a t e s , at

17-18 - - a p p l i e s e q u a l l y in th e h o u s in g

c o n te x t in Hunter. However, that not a l l

m i n o r i t i e s s u p p o r t open h o u s in g o r i n

t e g r a t e d s c h o o l i n g does not undermine the

c o n c lu s i o n in Hunter, Lee and below that

a l e g i s l a t i v e c l a s s i f i c a t i o n b u r d e n in g

such s u p p o r t e r s , but no o th e r c i t i z e n s , i s

u n c o n s t i t u t i o n a l b e c a u s e t h o s e whom i t

does d isadvantage are m i n o r i t i e s . Other

w ise , f o r example, the C o u r t ' s c o n c lu s i o n

in Nixon v. Herndon, s u p r a , that a "white

Democratic primary" law u n c o n s t i t u t i o n a l l y

d isadvantages b lacks would be undermined

by th e f a c t t h a t many b l a c k s are Repub

l i c a n s , and have no d e s i r e t o vo te in the

Democratic primary. See notes 2, 3, supra.

32

o n e a s p e c t o f e d u c a t i o n a l p o l i c y — - -

o f s p e c i a l i n t e r e s t t o the r a c i a l m in o r i ty

v i c t i m s o f de f a c t o s e g r e g a t i o n —■ the law

l e f t the a u t h o r i t y o f s t a t e o f f i c i a l s in

t a c t as to a l l o t h e r e d u c a t i o n a l m a tters ,

i n c l u d i n g a l l o t h e r s t u d e n t - a s s i g n m e n t

m a t t e r s .

As in Hunter, the Court in Lee found

t h i s la w u n c o n s t i t u t i o n a l u n d e r t h e

Fourteenth Amendment because the s p e c i f i c

r e a r r a n g e m e n t o f th e p o l i t i c a l sys tem

c h o s e n t o a c c o m p l i s h th e p r e s e n t r e s

c i s s i o n and f u t u r e d i s c o u r a g e m e n t o f

9 / The law s t ru ck down in Lee a c t u a l l y

r e a l i g n e d a u t h o r i t y o v e r s tudent a s s i g n

ment t o a l l e v i a t e ale f a c t o s e g r e g a t i o n - in

two ways. In s c h o o l d i s t r i c t s governed by

an e l e c t e d s c h o o l board , f i n a l a u t h o r i t y

r e s t e d w i th t h a t b o a r d . In d i s t r i c t s

g o v e r n e d by an a p p o i n t e d s c h o o l b o a r d ,

however, the law withdrew the a u t h o r i t y t o

a s s ig n s tudents t o a l l e v i a t e s e g r e g a t i o n

from a l l ( i . e . , s t a t e and l o c a l ) e d u ca t io n

o f f i c i a l s , l e a v in g i t e x c l u s i v e l y in the

hands o f the s t a t e l e g i s l a t u r e . See Lee v .

N y q u i s t , s u p r a , 318 F. S u p p . a t 7 1 9 .

33

c i v i l - r i g h t s - o r i e n t e d b e n e f i t s previously-

c o n fe r r e d on m i n o r i t i e s was not r a c i a l l y

n e u t r a l :

[The s t a t u t e ] s i n g l e s o u t f o r

d i f f e r e n t t r e a t m e n t a l l p l a n s

w h i c h h a v e as t h e i r p u r p o s e

th e a ss ig n m e n t o f s t u d e n t s in

o r d e r t o a l l e v i a t e r a c i a l im

b a l a n c e . The C o m m is s io n e r and

l o c a l a p p o i n t e d o f f i c i a l s [ s e e

n o t e 9 , s u p r a ] a re p r o h i b i t e d

f r o m a c t i n g m t h e s e m a t t e r s

o n l y where r a c i a l c r i t e r i a are

i n v o l v e d . The s t a t u t e t h u s

c r e a t e s a c l e a r l y r a c i a l c l a s s i

f i c a t i o n , t r e a t i n g e d u c a t i o n a l

matters in v o lv in g r a c i a l c r i t e r i a

d i f f e r e n t l y from o t h e r e d u c a

t i o n a l m a t t e r s and m a k in g i t

m ore d i f f i c u l t t o d e a l w i t h

r a c i a l im b a la n ce in th e p u b l i c

s c h o o l s . We can co n c e iv e o f no

more c o m p e l l i n g c a s e f o r t h e

a p p l i c a t i o n o f the Hunter p r i n

c i p l e .

318 F. Supp. at 719 (Hays, J. ) , a f f ' d , 401

U.S. 935 (1971 ) .

Lee, l i k e Hunter, l i e s at the " c o r e "

o f the Fourteenth Amendment's " p r o t e c t i o n

[ o f m i n o r i t i e s ] f r o m t h e m a j o r i t a r i a n

34

p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s . " San Antonio Schoo l

D i s t . v . R o d r iq u e z , s u p r a , 411 U.S. at 28.

I t t o o s t r i k e s down an e f f o r t by members

o f the m a j o r i t y t o s t r u c t u r e the p o l i t i c a l

p r o c e s s s o t h a t t h e b l a c k v i c t i m s o f

s e g r e g a t i o n are once again r e l e g a t e d to

t h e h i s t o r i c a l p o s i t i o n o f " p o l i t i c a l

p o w e r le s s n e s s " v i s a v i s a l l o t h e r c i t i

zens th a t the Equal P r o t e c t i o n Clause was

p a r t i c u l a r l y d e s i g n e d t o rem edy . I d .

D. I n i t i a t i v e 350

I n i t i a t i v e 350 i s a m ir r o r image o f

the law found u n c o n s t i t u t i o n a l in Nyquist

v . L e e . Like that law, I n i t i a t i v e 350 was

l e g i s l a t e d in d i r e c t response t o a plan

( i n t h i s c a s e "T h e S e a t t l e P l a n " ) o f

" m a n d a t o r y " s t u d e n t r e a s s i g n m e n t t o

a ch ie v e g r e a t e r i n t e r r a c i a l c o n t a c t in the

1 0 /

s c h o o l s , o n l y h e r e t h e n o n n e u t r a l

10/ "Mandatory" i s a misnomer. For the

c i t i z e n s o f S e a t t l e , through t h e i r e l e c t e d

35

real ignment o f power runs from the l o c a l

to the State l e v e l , ra th e r than from the

1 1/S t a t e t o th e l o c a l l e v e l , as in L e e .

In the S t a t e o f W a s h in g t o n , as in

most American j u r i s d i c t i o n s ( e x c e p t i n g

New Y o rk ) , see M i l l ik e n v. B r a d le y , s u p r a ,

418 U.S. at 742 & n. 20, the a u t h o r i t y to

10/ cont inued

r e p r e s e n t a t i v e s on the s c h o o l board o f

t h a t d i s t r i c t , v o l u n t a r i l y c h o s e t o r e

a s s i g n s t u d e n t s i n o r d e r t o a c h i e v e a

g r e a t e r d e g r e e o f r a c i a l b a l a n c e . The

mandate, that i s , came not from a f e d e r a l

c o u r t o r o t h e r a g e n c y n o t d i r e c t l y r e s

p o n s i b l e to the c i t i z e n s o f S e a t t l e , but

from those c i t i z e n s themselves . The term

i s a ccu ra te on ly in the sense t h a t , as in

v i r t u a l l y e v e r y p u b l i c s c h o o l sys tem in

the cou n try , the student assignment plan

in S e a t t l e re q u ire s that s tudents l i v i n g

i n s p e c i f i e d a r e a s a t t e n d s p e c i f i e d

s c h o o l s , ra th e r than a l low in g each student

v o l u n t a r i l y t o c h o o s e th e s c h o o l he o r

she a t te n d s .

11 / The law in Lee r e a l ig n e d the p o l i t i

c a l p r o c e s s in some d i s t r i c t s in New York

by removing a u t h o r i t y from e d u ca t io n o f f i

c i a l s g e n e r a l l y and g iv in g i t to the Sta te

l e g i s l a t u r e . See note 9, s u p r a . To t h i s

e x t e n t , I n i t i a t i v e 350 i s an e x a c t , ra th er

than m ir r o r , image o f the law s t ru ck down

in Lee.

36

o p e r a t e the p u b l i c s c h o o l s and, s p e c i f i c

a l l y , t o a s s i g n s t u d e n t s t o p a r t i c u l a r

f a c i l i t i e s , r e s i d e s a lm o s t e x c l u s i v e l y

in l o c a l s c h o o l b o a r d s . "The law [ o f

Washington] has p l a i n l y ves ted the board

o f d i r e c t o r s o f s c h o o l d i s t r i c t s such as

t h i s w i th d i s c r e t i o n a r y powers in such

m a t t e r s . " S ta te ex r e l , Lukens v . Spokane

S c h o o l D i s t r i c t 81 , 147 Wash. 4 6 7 ,

474, 266 P. 189, 191 (1 9 2 8 ) . See S e a t t l e

Schoo l D i s t . No. 1 v. Washington, 473 F.

Supp. 996, 1010 (W.D. Wash. 1979) (F inding

o f F a c t 8 . 2 ) . As t h e Supreme C ou r t o f

Washington has e x p r e s s l y h e l d , the S e a t t l e

s c h o o l board was f r e e t o adopt a mandatory

i n t e g r a t i o n program such as The S e a t t l e

Plan in the proper e x e r c i s e o f i t s broad

d i s c r e t i o n a r y power over s tudent a s s i g n

ment . See C i t i z e n s A g a i n s t Mandatory

B u s s in g v . P a lm a s o n , 495 P .2d 6 5 7 , 666

37

12/

(Wash. 1 9 7 2 ) .—

Although the S e a t t l e Plan encountered

o p p o s i t i o n , i t s o p p o n e n t s d id n o t seek

t o r e s c in d the Plan through the p r e - e x i s t

ing p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s . In s te a d , they found

i t e a s i e r t o rearrange that p r o c e s s through

13/

adopt ion o f I n i t i a t i v e 350. 473 p. supp.

at 1006-07 (Findings o f Fact 6 . 3 , 7 . 1 - 7 . 5 ) .

12/ In P a lm a s o n , th e Supreme C ourt o f

Washington h e ld , p r i o r to the enactment o f

I n i t i a t i v e 350, that l o c a l s c h o o l boards

in Washington have almost p len a ry " d i s c r e

t i o n a r y power" o v e r s t u d e n t a s s ig n m e n t s

w i t h i n t h e i r d i s t r i c t s , s u b j e c t o n l y t o

j u d i c i a l review to determine i f such as

signments " v i o l a t e some fundamental r i g h t

o f the party c h a l l e n g in g them." 495 P.2d

at 660 & n n . 3 , 4. The C ou rt c o n c l u d e d

that a p r e d e c e s s o r o f "The S e a t t l e Plan"

v i o l a t e d no such r i g h t . I_d. a t 6 6 2 - 6 3 .

13/ P r e v i o u s a t t e m p t s by o p p o n e n t s o f

d e s e g r e g a t i o n t o r e c a l l the p r o - i n t e g r a t i o n

members o f t h e S e a t t l e s c h o o l b o a r d

had f a i l e d . 473 F. Supp. at 1006 (F inding

o f Fact 6 . 3 ) , a f f ' d , 633 F.2d 1338, 1346

(9th C i r . 1980).

38 -

As in Hunter and L e e , however, the Wash

in g ton v o t e r s who adopted the I n i t i a t i v e

d i d n o t g e n e r a l l y r e s t r u c t u r e th e p o l i

t i c a l p r o c e s s s o t h a t a_l__l c o m p a r a b l e

g o v e r n m e n t a l a c t i o n would be h a r d e r t o

s e c u r e in th e f u t u r e . R a t h e r , u s i n g a

s u b j e c t - m a t t e r c l a s s i f i c a t i o n l i k e those

s t ru ck down in Hunter and L e e , I n i t i a t i v e

350 re s c in d e d The S e a t t l e Plan and p reven

ted i t s d u p l i c a t i o n in the fu t u r e by non-

n e u t r a l l y r e a l i g n i n g the p o l i t i c a l s t r u c

t u r e o f p u b l i c e d u c a t i o n in W ash in gton

a long l i n e s co r resp on d in g t o the race o f

the persons a d v e r s e ly a f f e c t e d . Under the

I n i t i a t i v e , th e m i n o r i t y v i c t i m s o f de

f a c t o s c h o o l s e g r e g a t i o n cou ld o n ly secure

governmental a c t i o n r e l i e v i n g that c o n d i

t i o n from t h e S t a t e l e g i s l a t u r e o r th e

S t a t e e l e c t o r a t e a t l a r g e , a l t h o u g h a l l

o t h e r c i t i z e n s remained f r e e t o a c h i e v e

any o t h e r g o a l o f p u b l i c e d u c a t i o n o r

s tudent assignment through l o c a l s c h o o l

b o a r d s .

The r a c i a l c l a s s i f i c a t i o n drawn by

I n i t i a t i v e 350 i s c l e a r from the f a c e o f

that p r o v i s i o n . Under the I n i t i a t i v e , the

c i t i z e n s o f W ash ington remain f r e e , as

b e f o r e i t was a d o p t e d , t o s e c u r e from

l o c a l s c h o o l boards : ( i ) any governmental

a c t i o n a f f e c t i n g p u b l i c ed u ca t ion o t h e r

than student assignment ( I n i t i a t i v e 350,

§ 1 ) , and any s tudent -ass ignment a c t i o n

d e s i g n e d t o ( i i ) u t i l i z e " t h e s c h o o l

n e a re s t o r next neares t t o s t u d e n t ' s p l a c e

o f r e s i d e n c e " ( ic3. ) , o r , r e g a r d l e s s o f the

l o c a t i o n o f the s c h o o l f a c i l i t y , t o ( i i i )

improve " the course o f s tudy" a v a i l a b l e to

s t u d e n t s ( i (3. ) , ( i v ) p r o v i d e " s p e c i a l

e d u c a t i o n , care o r g u id a n c e , " in c lu d in g

f o r " s tu den ts who are p h y s i c a l l y , m enta l ly

40

o r e m o t i o n a l ly handicapped" (Ld. §§ 1 ( 1 ) ,

( 4 ) ) , (v ) a l l e v i a t e t r a n s p o r t a t i o n d i f f i

c u l t i e s , c a u s e d by " h e a l t h o r s a f e t y

h azard s , e i t h e r na tura l o r man-made, o r

p h y s i c a l b a r r i e r s o r o b s t a c l e s , e i t h e r

n a tu ra l o r man-made" ( i d . § 1 ( 2 ) ) , ( v i )

avo id a ttendance at f a c i l i t i e s that are

" u n f i t o r i n a d e q u a t e b e c a u s e o f o v e r

c r o w d i n g , u n s a f e c o n d i t i o n s o r l a c k o f

p h y s i c a l f a c i l i t i e s " (_id. § 1 ( 3 ) ) , o r

( v i i ) s a t i s f y "most, i f not a l l , o f the

major reasons f o r which s tudents are at

p r e s e n t ass igned t o s c h o o l s o t h e r than the

n e a re s t o r next n eares t s c h o o l s " e x c e p t

f o r d e s e g r e g a t i o n (453 F. Supp. at 1010,

1 4 /

Finding o f Fact 8 . 3 ) . As i t s p ro p o

nents promised the v o t e r s o f Washington,

14/ I n i t i a t i v e 350 i s not a n e ig h borh ood -

s c h o o l law. I t l e a v e i i n t a c t the l o c a l

s c h o o l b o a r d ' s broad d i s c r e t i o n t o d e f i n e

the c u r r i c u l u r , r e m e d ia l , h e a l t h , s a f e t y ,

t r a n s p o r t a t i o n and s p a c e n eeds o f i t s

41

I n i t i a t i v e 350 o c c a s i o n s " n o l o s s o f

[ l o c a l ] s c h o o l d i s t r i c t f l e x i b i l i t y o t h e r

than in b u s i n g f o r d e s e g r e g a t i o n p u r

p o se s " (473 F. Supp. at 1008, Finding o f

Fact 7 . 1 8 ) , and in no way a f f e c t s the "99%

o f th e s c h o o l d i s t r i c t s " i n W ash ington

( i , e . , a l l but the three respondent d i s

t r i c t s ) t h a t are not now a s s i g n i n g o r

contem plat ing the assignment o f s tudents

14/ cont inued

s t u d e n t s , and t o a ss ign those s tudents to

s c h o o l s o th e r than those neares t o r next

n ea res t t h e i r p la c e o f r e s i d e n c e , i f i t

con c lu d es that any o f those needs w i l l be

b e t t e r served by such ass ignments . A c c o r

d i n g l y , even were a n e ig h b o r h o o d -s c h o o l

p o l i c y com p e l l in g enough t o j u s t i f y what

o t h e r w i s e amounts t o a c o n s t i t u t i o n a l

v i o l a t i o n — but see Swann v . C h a r l o t t e -

Mecklenburg Board o f E d u ca t ion , 402 U.S 1,

28 (1971) — I n i t i a t i v e 350 i s des igned t o

a c h i e v e no such p o l i c y , s i n c e as b o th

c o u r t s below expi?essly found, i t f r e e l y

a l l o w s l o c a l s c h o o l boards t o ignore that

g o a l whenever any e d u c a t i o n a l i n t e r e s t

o t h e r than r a c i a l i n t e g r a t i o n i s in v o lv e d .

453 F. Supp. a t 1010 ( F i n d i n g o f F a c t

8 . 3 ) , a f f ' d , 633 F . 3 d a t 1344 & n . 4 .

42

t o encourage i n t e r r a c i a l c o n t a c t (i<3. at

1008-09, Finding o f Fact 7 . 9 ) .

A c c o r d i n g l y , t h e s i n g l e c l a s s s u b

j e c t e d by I n i t i a t i v e 350 t o th e e x t r a

o r d i n a r y p o l i t i c a l burden o f h a v in g t o

o b t a i n s ta te w id e l e g i s l a t i v e o r popu lar

approva l o f l o c a l s tudent -ass ignm ent p r o

p o s a l s s u i t i n g i t s p a r t i c u l a r n eed s i s

composed e x c l u s i v e l y o f " th e b la ck s t u

d e n t s " in th e S t a t e o f W a s h in g to n who

a r e v i c t i m i z e d b y s e g r e g a t i o n i n t h e

p u b l i c s c h o o l s . Id . at 1007 (F inding o f

15/Fact 6 . 1 2 ) , a f f ' d , 633 F.2d at 1342 -44 .—

S i n c e , as in Hunter and Lee the d i s a d v a n -

15/ The C o u r t s b e l o w b o t h found t h a t

b la ck c i t i z e n s l i v i n g in segreg atd n e ig h

borhoods in Washington b e l i e v e th a t r a c i a l

i n t e g r a t i o n o f the s c h o o l s would b e n e f i t

t h e i r c h i l d r e n . R e g a r d l e s s o f w h e th e r

t h o s e c i t i z e n s a re r i g h t o r wrong ( s e e

S e c t i o n I I , i n f r a ) , the S ta te o f Washing

ton may not c o n s t i t u t i o n a l l y s u b j e c t them

t o p o l i t i c a l h u r d l e s , n o t a p p l i c a b l e

t o o t h e r c i t i z e n s , t h a t im p e d e t h e i r

achievement o f th a t g o a l . In s h o r t , the

taged c l a s s i s d e f in e d by the race o f i t s

members, the law o f f e n d s the Equal P r o t e c

t i o n Clause r e g a r d le s s o f th e m o t iv a t i o n

£ . 1 6 /

o f i t s proponents .

15/ continued

s o c i a l v a l i d i t y o f r a c i a l i n t e g r a t i o n i s

not at i s su e here . What i s at i s su e i s

the r i g h t o f b lack c i t i z e n s t o pursue that

l e g i t i m a t e governmental o b j e c t i v e through

l a w f u l p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s e s on th e same

b a s i s as a l l o th e r c i t i z e n s are perm itted

t o pursue t h e i r l e g i t i m a t e governmental

e n d s .

1 6 / Much i s made by a p p e l l a n t s o f th e

f a c t t h a t th e p r o v i s i o n s i n Hunter and

Lee d e f in e d the fo r b id d e n s u b j e c t - m a t t e r

c l a s s i f i c a t i o n in terms o f the s u b j e c t -

matter on which a s p e c i a l p o l i t i c a l burden

was p l a c e d by t h e S t a t e ( i . e . , f a i r

housing r e g u l a t i o n in Hunter and student

r e a s s i g n m e n t t o a c h i e v e i n t e g r a t i o n in

Le e ) , and a c c o r d i n g l y u s e d t h e word

" r a c e , " w hi le the d r a f t e r s o f I n i t i a t i v e

350 d e f in e d the s u b j e c t - m a t t e r c l a s s i f i

c a t i o n in terms o f a l l o f th e s u b j e c t

m a t t e r s on which the s p e c i a l p o l i t i c a l

burden was n ot p l a c e d ( i . e . , e v e r y use

o f s t u d e n t r e a s s ig n m e n t sav e f o r i n t e

g r a t i o n ) , and thereby avoided using the

word " r a c e . " However , i t was not the

wording o f the laws in Hunter and Lee, o r

even any f a c i a l n o n n e u t r a l i t y in t h a t

w o r d i n g , t h a t r e n d e r e d t h o s e laws un-

44

To p u t i t b l u n t l y , members o f th e

p o l i t i c a l m a j o r i t y in W ash in g ton have

passed a law r e q u i r i n g r a c i a l m i n o r i t i e s

t o seek s ta te w id e approval o f govermental

a c t i o n on t h e i r b e h a l f , whi le i n s i s t i n g

t h a t a c t i o n on e v e r y one e l s e ' s b e h a l f

need o n l y s e c u r e t h e a p p r o v a l o f l o c a l

o f f i c i a l s . As a r e s u l t , t h e i n t e r n a l

16/ cont inued

c o n s t i t u t i o n a l . As the Hunter Court n o t

e d , th ose laws on t h e i r f a c e s " t r e a t [ e d ]

Negro and w h i t e , Jew and g e n t i l e i n an

i d e n t i c a l m a t t e r . " Hunter v . E r i c k s o n ,

s u p r a , 393 U.S. at 391. The Court s t ru ck

down the laws in Hunter and Lee because i t

was c l e a r , o n c e th e " c o v e r t " s t a t u t o r y

c l a s s i f i c a t i o n s they c re a te d were exposed

( s e e P e r s o n n e l A d m in is t ra t io n v . Feeney,

4 42 U. S . ...2'5_67'"'"2T4'"TT979 ) ) , ..t h a T f h e y

separated persons f o r d i f f e r e n t i a l t r e a t

ment a long l i n e s th a t corresponded e x a c t l y

( r a t h e r than o n ly approx im a te ly , as in ,

e . g . , Feeney , s u p r a ; V i l l a g e o f A r l in g t o n

Heights v. M e tr o p o l i ta n Housing A u t h o r i t y ,

429 U.S. 252 (1 977 ) ; Washington v . Davis

426 U .S . 229 ( 1 9 7 6 ) ; and James v . V a l -

t i e r r a , 402 U.S. 137 ( 1 971 ) ) t o the race

o f the persons a d v e r s e ly a f f e c t e d . I t i s

in t h i s sense that the o f f e n s i v e c l a s s i f i

c a t i o n s were " e x p l i c i t l y r a c i a l , " and thus

45

p o l i t i c a l p r o c e s s e s g o v e r n i n g p u b l i c

e d u ca t io n in Washington are not o rgan ized

"on the b a s i s o f any gen era l p r i n c i p l e , "

Hunter v. E r i c k s o n , s u p r a , 393 U.S. at 395

( H a r l a n , J . , c o n c u r r i n g ) , and do n o t

" t r e a t [] a l l i n d iv id u a l s as eq u a ls " r e

g a r d l e s s o f r a c e , Mobile v . Bolden, s u p r a ,

16/ cont inued

u n c o n s t i t u t i o n a l , r e g a r d l e s s o f the motive

f o r d raw in g them. Hunter v . E r i c k s o n ,

s u p r a , 393 U.S at 389; see notes 5, 8,

supra.

The c l a s s i f i c a t i o n drawn by I n i t i a t i v e

350 i s nonneutral and e x p l i c i t l y r a c i a l

in p r e c i s e l y the same way as the c l a s s i f i

c a t i o n s s t r u c k down in Hunter and Lee .

Indeed, as the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s f a c t f i n d -

ings make c l e a r , the c l a s s i f i c a t i o n drawn

by I n i t i a t i v e 350 — between m i n o r i t i e s

f a v o r i n g mandatory student assignment t o

r e l i e v e them o f r a c i a l i s o l a t i o n and a l l

o t h e r persons seeking b e n e f i c i a l govern

m en ta l a c t i o n r e l a t i n g t o e d u c a t i o n o r

s tudent assignment — i s i d e n t i c a l t o the

e x p l i c i t l y r a c i a l c l a s s i f i c a t i o n s truck

down in Lee . See 473 F. Supp. at 1008-09

(F indings o f Fact 7 . 8 , 7 . 9 , 7 .1 8 , 7 . 1 9 ) .

Put s im ply , i t was the substance o f

the laws s t ruck down in Hunter and Lee,

- 46

446 U.S. at 84 (S te ve n s , J. , c o n c u r r i n g ) .

R a t h e r , t h e y deny th e b l a c k v i c t i m s o f

s c h o o l s e g r e g a t i o n t h e same d e g r e e o f

p o l i t i c a l p r o t e c t i o n a f f o r d e d a l l o t h e r

c i t i z e n s by the laws o f the S t a t e . T h is ,

in i t s rawest form, i s the d e n ia l o f " the

e q u a l p r o t e c t i o n o f t h e l a w s . " I t i s

u n c o n s t i t u t i o n a l u n d e r t h e F o u r t e e n t h

Amendment.

16/ cont inued

and i t i s t h e i d e n t i c a l s u b s t a n c e o f

I n i t i a t i v e 350 - - t h e c o r r e s p o n d e n c e o f

t h e c l a s s i f i c a t i o n drawn t o th e r a c e o f

the persons a d v e r s e ly a f f e c t e d — r a th e r

than the form o r s p e c i f i c wording o f those

p r o v i s i o n s that (b a rr in g some com p e l l in g

j u s t i f i c a t i o n ) render a l l three u n c o n s t i