Jones v. Deutsch Opinion

Public Court Documents

June 28, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jones v. Deutsch Opinion, 1989. 78c4b872-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5e98a170-28d1-4e3f-a35a-465310b64d0c/jones-v-deutsch-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

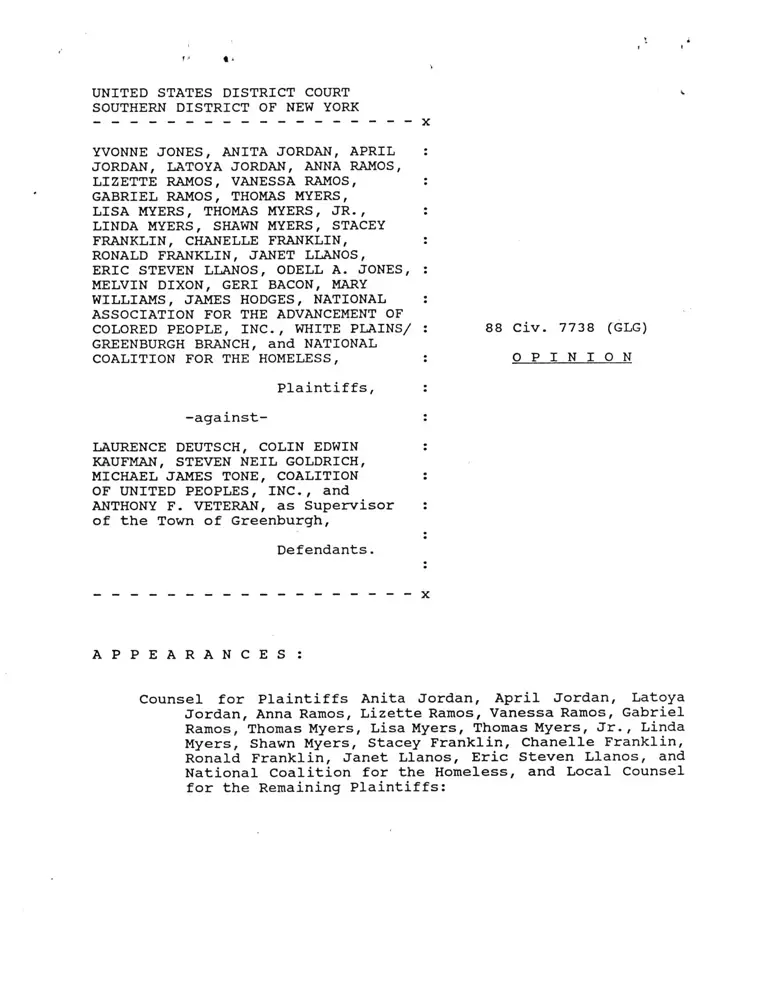

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

— - — — - — - — - - - - - - - - - - x

YVONNE JONES, ANITA JORDAN, APRIL :

JORDAN, LATOYA JORDAN, ANNA RAMOS,

LIZETTE RAMOS, VANESSA RAMOS, :

GABRIEL RAMOS, THOMAS MYERS,

LISA MYERS, THOMAS MYERS, JR., :

LINDA MYERS, SHAWN MYERS, STACEY

FRANKLIN, CHANELLE FRANKLIN, :

RONALD FRANKLIN, JANET LLANOS,

ERIC STEVEN LLANOS, ODELL A. JONES, :

MELVIN DIXON, GERI BACON, MARY

WILLIAMS, JAMES HODGES, NATIONAL :

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF

COLORED PEOPLE, INC., WHITE PLAINS/ : 88 Civ. 7738 (GLG)

GREENBURGH BRANCH, and NATIONAL

COALITION FOR THE HOMELESS, : O P I N I O N

Plaintiffs, :

-against-

LAURENCE DEUTSCH, COLIN EDWIN

KAUFMAN, STEVEN NEIL GOLDRICH,

MICHAEL JAMES TONE, COALITION

OF UNITED PEOPLES, INC., and

ANTHONY F. VETERAN, as Supervisor

of the Town of Greenburgh,

Defendants.

x

A P P E A R A N C E S :

Counsel for Plaintiffs Anita Jordan, April Jordan, Latoya

Jordan, Anna Ramos, Lizette Ramos, Vanessa Ramos, Gabriel

Ramos, Thomas Myers, Lisa Myers, Thomas Myers, Jr., Linda

Myers, Shawn Myers, Stacey Franklin, Chanelle Franklin,

Ronald Franklin, Janet Llanos, Eric Steven Llanos, and

National Coalition for the Homeless, and Local Counsel

for the Remaining Plaintiffs:

1

f' t

PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND, WHARTON & GARRISON

1285 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10019

By: Jay L. Himes, Esq.

Cameron Clark, Esq.

Melinda S. Levine, Esq.

William N. Gerson, Esq.

Of Counsel

Counsel for Plaintiffs Yvonne Jones, Odell A. Jones, Melvin

Dixon, Geri Bacon, Mary Williams, James Hodges, National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Inc.,

White Plains/Greenburgh Branch:

GROVER G. HANKINS, ESQ.

NAACP, Inc.

4805 Mount Hope Drive

Baltimore, Maryland 21215-3297

By: Robert M. Hayes, Esq.

Virginia G. Shubert, Esq.

COALITION FOR THE HOMELESS

105 East 22nd Street

New York, New York 10010

Julius L. Chambers, Esq.

John Charles Boger, Esq.

Sherrilyn Ifill, Esq.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

Andrew M. Cuomo, Esq.

12 East 33rd Street - 6th Floor

New York, New York 10016

Of Counsel

Counsel for Defendants Deutsch, Tone, Goldrich, and Coalition

of United Peoples, Inc.:

LOVETT & GOULD

180 East Post Road

White Plains, New York 10601

By: Jonathan Lovett, Esq.

Of Counsel

Counsel for Defendant Colin Edwin Kaufman:

QUINN & SUHR

170 Hamilton Avenue

White Plains, New York 10601

By: Timothy C. Quinn, Jr., Esq.

Of Counsel

1

G O E T T E L, D. J. :

In January of 1988, leaders from the Town of Greenburgh threw

their support behind a county proposal to build emergency or

"transitional" housing for the homeless on a 30-acre site in the

town owned by the County of Westchester. The current design calls

for the construction of six two-story buildings, each comprising

some 18 units of housing, with a seventh building to be used for

administrative support, day care, and skills training.

In response thereto, a number of residents owning property

surrounding the proposed site formed the Coalition of United

Peoples, Inc. ("COUP"), whose purpose, de facto or otherwise, is

to prevent or substantially modify the housing project. As part

of those efforts, COUP members sought to secede from the Town of

Greenburgh by incorporating as a separate community to be

denominated the Village of Mayfair Knollwood. Pursuant to the

provisions of N.Y. Village Law §§ 2-200 to 2-258 (McKinney 1973 &

Supp. 1989) , an incorporation petition was presented to Greenburgh

Town Supervisor Anthony Veteran. Following a public hearing, Town

Supervisor Veteran rejected the petition on various constitutional

and statutory grounds outlined in a decision dated December 1, 1988

(the "December 1 Decision"). Among other things, Town Supervisor

Veteran concluded that the proposed "boundaries, where

ascertainable, were gerrymandered in a manner to exclude black

persons from the proposed village" and that the petition also would

"racially discriminate against homeless persons who are

predominantly black." December 1 Decision 5 2, at 2 and 5 3 , at

1

7. Two COUP members then appealed that decision to New York

Supreme Court in an Article 78 proceeding,1 which action

subsequently was removed to this court by the respondents.

Concluding that we would abstain from adjudicating the Article 78

proceeding under familiar doctrine finding its origins in Burford

v. Sun Oil Co. . 319 U.S. 315 (1943) and Railroad Comm1n of Texas

v. Pullman. 312 U.S 496 (1941) , we remanded the matter, sua sponte.

to State court. In re Greenberg. No. 89 Civ. 0591, slip op. at 24-

31 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 17, 1989) (LEXIS). Town Supervisor Veteran

appealed and is seeking a stay of the remanded Article 78

proceeding pending decision by the Second Circuit.

The Greenberg respondents argued to us, in essence, that if

the statutory scheme regulating village incorporation is allowed

to proceed in this case, it should be a Federal court that presides

over that process due to the implication of various federal

questions. We disagreed. The ratio decendi of our decision was

that, in the absence of conflicting federal-state mandates imposed

on State or municipal officials concerning the protection of equal

rights, the comprehensive political/regulatory process created by

New York to govern village incorporation should be allowed to work

its will given the State's manifest and overriding interest in such

matters. We emphasized, however, that should that process fail to

See N.Y. Civ. Prac. L. & R. §§ 7801-06 (McKinney 1981 &

Supp. 1989). Under N.Y. Village Law § 2-210 (McKinney 1973 & Supp.

1989) , an Article 78 proceeding statutorily is prescribed as the

avenue for appeal of a town supervisor's decision rejecting an

incorporation petition.

2

serve the people in a color-blind fashion, the Federal courts would

be there to ensure the vindication of federally protected rights.

See Greenberg. slip op. at 29 n.ll (noting that "[h]ad the instant

incorporation petition been approved under the Village Law, and the

Deutsch plaintiffs [plaintiffs in the instant action] (assuming

they had standing) then challenged that action in federal court on

Fourteenth Amendment grounds, we have little doubt that we properly

would have jurisdiction over the subject matter and that

plaintiffs' choice of a federal forum would be respected"). Until

that time, however, we continue to believe that Federal

intervention in the incorporation process is both premature and

imprudent and would undermine sound notions of comity and

federalism.

Plaintiffs in this case (many of whom are respondents in the

Article 78 proceeding) seek to go one step further by, in essence,

preempting the village incorporation process altogether. Charging

COUP with leadership of a conspiracy to violate civil rights,

plaintiffs seek, inter alia. a permanent injunction restraining

COUP from continuing with their heretofore unsuccessful

incorporation efforts. Until the incorporation petition receives

some form of State approval under the Village Law, however, the

harms plaintiffs seek to prevent — alleged discriminatory

3

violations of their voting and housing rights — cannot be

realized.2

Moreover, to issue the injunction sought by plaintiffs, an

evidentiary hearing to assess discriminatory intent/impact

undoubtedly would be required. Given the present posture of this

matter, we could very well be holding a lengthy and expensive

evidentiary hearing on an incorporation petition that will never

be put before the voters. Such a premature and potentially

wasteful exercise of Federal judicial resources cannot be

countenanced.

Understandably, lawyers, like anyone, would prefer to do

battle on familiar turf — in their case, the courts. But this

lawyerly penchant for prematurely bringing local political battles

into Federal court cannot help but erode our legitimacy and

authority in the eyes of the citizens and Constitution we serve if

it is given effect. Simply put, we feel no differently now than

when we issued our remand decision: the process established by the

Before the incorporation can take effect, the petition

must be approved by the town supervisor (who has been delegated the

authority by the State to provide the initial review of

incorporation petitions), survive challenge in the State courts via

the Article 78 process, be ratified by a majority of would-be

residents of the proposed village, and survive challenge to the

election in state court. N.Y. Village Law §§ 2-208, 2-210, 2-222,

& 2-224 (McKinney 1973 & Supp. 1989). If that approval is secured,

the Secretary of State then issues a certificate of incorporation.

Id. at § 2-234. We add that "the restraints imposed by the

Constitution on the States [cannot] be circumvented by local bodies

to whom the State delegates authority." Sailors v. Board of Edu..

387 U.S. 105, 108 n.5 (1967). Consequently, throughout our remand

decision and here we treat the town supervisor, at least when

exercising authority under the Village Law, as an agent of the

State.

4

State to regulate village incorporation should and must be given

a chance to work. Indeed, given the result thus far obtained —

rejection of the petition, the principal result sought by this

complaint — it is hard to fathom why plaintiffs harbor so little

faith in the political process they seek to enjoin. Nonetheless,

as we have made clear, the doors to Federal court will be wide open

should the political process ultimately work an unconstitutionally

discriminatory result. In re Greenberg, slip op. at 29 n.11.

Given these concerns, it should not be surprising that we

believe this action to be both procedurally and substantively

premature unless and until the State acts to give effect to COUP'S

efforts, and we dismiss the complaint as a result.

I. THE FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT

The original complaint in this action was filed prior to the

December 1 Decision rejecting the incorporation petition.

Following that action, plaintiffs were granted leave to file a

first amended complaint ("FAC"), which is the subject of the

instant motions. The pertinent facts underlying this action are

detailed more completely in our remand decision, In re Greenberg,

slip op. at 2-8, familiarity with which is presumed.

The plaintiffs are comprised of two groups: (i) a number of

black individuals who either live in Greenburgh and would be

affected by approval of the allegedly gerrymandered incorporation

petition or who live in Westchester County and would supposedly

qualify for residence at the proposed housing project (the

5

"individual plaintiffs"); and (ii) the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, Inc., White Plains/Greenburgh Branch

(the "NAACP") and the National Coalition for the Homeless (the

"institutional plaintiffs"). The defendants are COUP and four of

its leaders (the "COUP defendants") and Town Supervisor Veteran.

Based on COUP'S allegedly discriminatory efforts to

incorporate the Village of Mayfair Knollwood, FAC 5 1, at 1-2, four

counts are presented in the complaint:

count I — the COUP defendants, in violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3)

("section 1985(3)"), have conspired and are continuing to

conspire to abridge the voting rights of certain of the

individual plaintiffs by gerrymandering in a racially

discriminatory fashion the proposed boundaries of the Village

of Mayfair Knollwood;3

count II — the COUP defendants have conspired and are continuing

to conspire in violation of section 1985(3) to violate the

housing rights of those individual plaintiffs now homeless;

count III — the COUP defendants have conspired and are continuing

to conspire in violation of section 1985(3) to violate the

The substantive violations comprising this count are

alleged violations of U.S. Const, amend. XV; section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973; N.Y. Const, art. I, §§ 1 &

11; and N.Y. Civ. Rights Law § 40-c (McKinney Supp. 1989). The

NAACP joins this count on its own behalf and on behalf of its

members.

A The substantive violations comprising this count are

alleged violations of the U.S. Const, amend. XIV; section 804 of

the Fair Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. § 3604; N.Y. Const, art. I, § 11;

id. at art. XVII, § 1; N.Y. Civ. Rights Law § 40-c (McKinney Supp.

1989); and N.Y. Exec. Law § 291(2) (McKinney 1982). The NAACP

joins this count on its own behalf and on behalf of its members.

The National Coalition for the Homeless joins this count on its own

behalf and on behalf of the homeless of Westchester County.

6

those individualemergency-shelter rights possessed by

plaintiffs now homeless;5

count IV — this count is asserted solely against defendant

Veteran, and it seeks a judgment declaring that Veteran

possesses the authority under the Federal and State

Constitutions, consistent with his oath of office, to reject

the COUP incorporation petition.6

In addition to compensatory damages and attorney's fees,

plaintiffs seek "entry of a permanent injunction restraining the

[COUP] Defendants from continuing their unlawful conspiracy,

including, but not limited to, pursuing any further proceedings

with respect to the Petition to incorporate the proposed Village

of Mayfair Knollwood." FAC at 25. Our jurisdiction is premised

on the bases of the asserted federal claims.

The individual plaintiffs allege standing sufficient to

maintain this action on grounds that (i) they are being denied or

threatened with denial of their voting and housing rights, FAC 5

52(a) & (b), at 20, and (ii) they "are being denied the benefits

of association, residence, interaction and other contact arising

from living in a community that is free from discrimination on

account of race or homelessness," FAC 5 52(c), at 20. The

The substantive violations comprising this count are

alleged violations of the U.S. Const, amend. XIV; 42 U.S.C. §§ 601

& 602; N.Y. Const, art. I, § 1; id̂ _ at art. XVII, § 1; N.Y. Soc.

Serv. Law §§ 62(1) & 131 (McKinney 1983 & Supp. 1989). The

National Coalition for the Homeless joins this count on its own

behalf and on behalf of the homeless of Westchester County.

Town Supervisor Veteran was included in the original

complaint as a member of the alleged civil rights conspiracy. One

of the key changes embodied in the FAC, as a result of the December

1 Decision, is the deletion of Veteran from the section 1985(3)

counts.

7

institutional plaintiffs allege standing on the basis that their

basic goals are being thwarted by the COUP conspiracy and that in

response thereto these groups have had to divert institutional

resources. FAC 5 52(d), at 20-21.

The COUP defendants move to dismiss the complaint on various

grounds, including lack of a justiciable question, standing, and

subject matter jurisdiction.7 In addition, they seek an award of

attorney's fees under 42 U.S.C. § 1988 or sanctions pursuant to

Fed. R. Civ. P. 11. Upon removal of the Article 78 proceeding,

these motions were adjourned sine die pending our decision as to

whether removal of the Article 78 petition was appropriate. Upon

issuance of our remand decision, the instant motions were scheduled

for oral argument, and are now ready for decision. * 8

Defendant Colin Edwin Kaufman, a COUP member, is

represented by separate counsel and he moves individually for

dismissal or, alternatively, for summary judgment. We treat his

motion as part of the motion to dismiss made by the other COUP

defendants.

8 Defendant Veteran has not joined in these motions to

dismiss, undoubtedly for his own strategic reasons. In a benign

sense, he presumably wants this matter resolved as quickly as

possible in whatever forum. In a more Machiavellian sense, a

Federal court order declaring that Veteran had to do what he did

in the December 1 Decision undoubtedly would help relieve whatever

political pressure he may be feeling. In any event, because he has

not moved to dismiss, count IV of the FAC is not addressed by this

decision and, at least temporarily, is left intact. The parties

can be sure, however, that notwithstanding their collective wishes,

the court will sua sponte if necessary seek briefing on dismissal

issues if they intend to press forward with count IV. For example,

given the apparent identity of interests between these parties,

count IV might fairly be considered collusive or, at minimum,

lacking in concrete adverseness. See generally C. Wright, A.

Miller, & E. Cooper, Federal Practice and Procedure 5 3530 (2d ed.

1984) . In addition, as plaintiffs' counsel concedes, "the Article

78 proceeding and [count IV] here are [simply] two sides of the

same coin." Plaintiffs' Brief, at 17. A further question is

8

II. DISCUSSION

If a ripe and cognizable claim embodying the kind of

injunctive relief sought herein could be asserted, and if these

plaintiffs had standing to bring such a claim, a strong argument

could be made that we should stay our hand, for to do otherwise

would potentially allow this action to work an end run on the

pending Article 78 proceeding. These concerns do not present

themselves, however, because we find that the FAC does not contain

the stuff of a ripe and cognizable federal claim.

fâ Ripeness

The COUP defendants move broadly to dismiss due to lack of a

justiciable question. Justiciability is a term of art embracing

the constitutional and related jurisprudential limitations placed

upon the jurisdiction of Federal courts. See generally. Flast v.

Cohen. 392 U.S. 83, 94-97 (1968). It is an umbrella-like term

which finds beneath its cover the various doctrines that shape and

define our authority to act in particular cases: ripeness,

standing, mootness, advisory opinion, and political question.

Although ripeness and standing virtually transect one another in

this case, it is our view that this matter is not ripe and must be

dismissed.

raised, therefore, as to the appropriate exercise of our

jurisdiction under Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971) and/or

Colorado River Water Conservation Dist. v. United States, 424 U.S.

800 (1976).

9

The ripeness doctrine is designed to ensure that a dispute has

"matured to a point that warrants decision." 13A C. Wright, A.

Miller, & E. Cooper, Federal Practice and Procedure § 3532, at 112

(2d ed. 1984) [hereinafter "Wright, Miller. and Cooper"!.

Determining whether that point has been reached "turns on 'the

fitness of the issues for judicial decision' and 'the hardship to

the parties of withholding court consideration.'" Pacific Gas &

Elec. Co. v. State Energy Resources Conservation and Dev. Comm'n,

461 U.S. 190, 201 (1983) (quoting Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner,

387 U.S. 136, 149 (1967)). Neither prong of this formula is

satisfied here.9

The alleged conspiracy is designed to abridge voting, housing,

and emergency-shelter rights purportedly guaranteed by federal and

state law. The vehicle chosen, however, to accomplish these

pernicious ends — incorporation of the Village of Mayfair

Knollwood — is not now and may never be a reality. To the

contrary, the incorporation petition has been rejected by Town

Supervisor Veteran.

Plaintiff contends, nonetheless, that we need not wait for

life to be breathed into this Frankenstein monster, if a monster

it is, before acting to protect established rights. As a general

proposition, we do not disagree with this contention. "'One does

not have to await the consummation of threatened injury to obtain

Although the Abbott Laboratories test was articulated in

a case challenging administrative action, these same concerns

inform analysis in a non-administrative context as well. Poe v .

Ullman. 367 U.S. 497, 508-09 (1961).

10

preventive relief. If the injury is certainly impending, that is

enough [to prevent dismissal on ripeness grounds].'" Regional Rail

Reorganization Act Cases. 419 U.S. 102, 143 (1974) (emphasis added)

(quoting Pennsylvania v. West Virginia. 262 U.S. 553, 593 (1923)).

See also Lake Carriers' Ass'n v. MacMullen, 406 U.S. 498, 506

(1972) (noting ripeness question centers on whether controversy is

111 of sufficient immediacy and reality to warrant'" relief)

(emphasis added) (quoting Maryland Casualty Co. v. Pacific—Coal— &

oil Co. . 312 U.S. 270, 273 (1941)). We do not agree with

plaintiffs that the end of this conspiracy is sufficiently

"impending" or that the controversy is of such "immediacy and

reality" as to warrant the relief here sought.

As to the deprivation or dilution of voting rights, that claim

is based on a number of contingencies that have not yet occurred.

As outlined supra note 2, before a certification of village

incorporation will be issued by the State an incorporation petition

must be certified by the town supervisor, survive challenge via an

Article 78 proceeding, be approved by a majority of the would-be

voting residents of the proposed village, and survive court

challenge to the electoral process utilized. The instant petition

has not even cleared the first of these hurdles.

Obviously, it is conceivable that the December 1 Decision will

be reversed by the New York courts during the Article 78

proceedings. Although conceivable. we think the possibility far

too speculative and of insufficient immediacy and reality as to

render this action fit for judicial decision. Among other things,

11

the December 1 Decision sets forth six separate bases, some

constitutional (both Federal and State) and some statutory, as

reasons for Town Supervisor Veteran's action. See In re Greenberg,

slip op. at 5-6. If any one of these grounds for rejection are

affirmed, then the COUP petition will fail. Thus, not only does

this case rest on a hypothetical reversal of the December 1

Decision by the New York courts, but reversal will occur only if

all six of the grounds stated by Town Supervisor Veteran are found

to be infirm. That we find this possibility to be too removed to

justify intervention by a Federal court should not be surprising.

This case, therefore, is strikingly dissimilar from the

leading Supreme Court decision cited as the linchpin of plaintiffs'

voting rights claims. In Gomillion v. Liqhtfoot, 364 U.S. 339

(1960), plaintiffs sought to enjoin operation of a statute enacted

by the Alabama Legislature which gerrymandered (in a racially

discriminatory fashion) the boundaries of the City of Tuskegee.

The Court held that an injunction would be appropriate, but the 10

10 Moreover, certain of the challenges raised by the Article

78 petitioners are based on contentions that the December 1

Decision is unsupported by sufficient evidence and that the

proceedings held by Town Supervisor Veteran did not comport with

the statutory requirements. Id. at 6-8. If these claims are

proven, an option seemingly available to the New York courts wou

be remand of the petition to Town Supervisor Veteran for further,

corrected proceedings. J. Weinstein, H. Korn, & A. Miller, Ne^

York Civil Practice IT 7806.01, at p. 78-145 (1988). Thus, although

the Article 78 petitioners have sought reinstatement of the

petition, that need not be the necessary product of reversal.

Consequently, even if the reversal feared by plaintiffs occurs, the

conclusion that the allegedly discriminatory petition will then

become a reality remains too attenuated.

12

case clearly was ripe for decision — the Alabama Legislature had

passed the offending statute and the resulting gerrymander,

therefore, certainly was impending. Id. at 340.

As to the threatened deprivation of housing and emergency-

shelter rights, these claims depend initially upon the success of

the currently rejected incorporation effort and then upon the

occurrence of certain additional events. If the gerrymander/voting

rights claims growing from the derailed petition effort are not yet

ripe, it follows a fortiori that the housing claims are premature.11

In arguing that this matter is fit for judicial intervention,

plaintiffs cite four cases in which Federal courts acted to enjoin

allegedly discriminatory secessionist movements that threatened to

frustrate existing school desegregation orders. Although ripeness

was not addressed specifically in any of these decisions, in each

case either the secession being challenged had been approved or

some other event had occurred which rendered the possibility of

secession sufficiently impending. See United States— v.— Scotland

Neck City Bd. of Edu.. 407 U.S. 484, 486-87 (1972) (state statute

11 There is yet a further, fundamental difficulty underlying

the exercise of our jurisdiction in this case. In crafting

injunctive relief, this court must be very specific in delineating

what precisely is being enjoined. Although we could conceivably

enjoin pursuit of the incorporation petition as it was submitted,

assuming its discriminatory purpose or impact, the practical effect

of that relief could prove limited should COUP or a similar group

of citizens decide to initiate a second incorporation petition.

So long as the second petition was substantially different from the

first in its geographical makeup, our injunction would in all

probability not apply. In reality, what plaintiffs really want is

an injunction barring COUP or its members from opposing the housing

project, and such an injunction would clearly be overbroad and

beyond the power of this court to approve.

13

authorizing creation of new school district had been approved and

residents subsequently had ratified ballot referendum effecting

that purpose); Wright v. Council of Emporia. 407 U.S. 451, 454-59

(1972) (new city already formed and steps taken by it to withdraw

its students from desegregated school district and create its own

independent district); Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Edu., 448 F . 2d

746, 749, 752 (5th Cir. 1971) (incorporation of independent school

district had occurred); Burleson v. County Bd. of Election Comm1rs,

308 F. Supp. 352, 353-54 (E.D. Ark.) (incorporation petition had

been certified and election approving secession had occurred),

aff'd. 432 F .2d 1356 (8th Cir. 1970) (per curiam).12 * These cases

are distinguishable from the instant facts where there has been

neither certification of the incorporation petition nor an election

approving incorporation.

Plaintiffs insist that we need not wait for those steps to

occur before acting, citing additionally and primarily two cases

in which Federal courts enjoined ballot referenda that the courts

viewed as unconstitutional. Holmes v. Leadbetter, 294 F. Supp. 991

(E.D. Mich. 1968); Otev v. Common Council of Milwaukee, 281 F.

Supp. 264 (E.D. Wis. 1968). The rationale underpinning these cases

is that courts need not wait for voter approval of a referendum

12 For similar reasons, other cases plaintiffs cite for

analogous authority are unavailing. See Huntington Branch. NAACP

v. Town of Huntington. 844 F.2d 926, 928, 941 (2d Cir. 1988) (town

board had already denied petition to amend discriminatory zoning

regulation), aff1 d . 57 U.S.L.W. 3331 (U.S. Nov. 7, 1988) (per

curiam); United States v. City of Black Jack. 508 F.2d 1179, 1188

(8th Cir.) (town board had adopted discriminatory zoning

ordinance), cert, denied. 422 U.S. 1042 (1975).

14

future events that may not occur as anticipated, or indeed may not

occur at a l l . Thomas v. Union Carbide Agric. Prod. Co., 473 U.S.

568, 580-81 (1985) (quoting 13A Wright, Miller,_& Cooper § 3532,

at 112) .14

In addition to assessing the fitness of the issue for judicial

determination, Abbott Laboratories requires that we consider the

hardships that would inure should we decline to act at this time.

Frankly, we see none — or at least none that would justify

intervention now. Should the incorporation petition be certified

(and, if required, voter approval be obtained), any party with

standing may seek at that time to enjoin the secession and, if that

party can meet the requirements for an injunction, prevent whatever

imminent harm is threatened.

The only "hardships" certain of these plaintiffs are enduring

are the costs incurred in opposing the petition politically and/or

14 We underscore additionally that, notwithstanding Holmes

and otev. we do not pass upon the propriety of court intervention

prior to a scheduled vote on an incorporation petition. As New

Yorkers should well know in light of Governor Thomas Dewey's "upset

loss" in the 1948 presidential election, no vote is certain. We

think voters can comprehend constitutional arguments made in the

context of a referendum campaign, and preempting voters from making

an electoral judgment on that score is a course to be traversed

most warily it seems to us. Nor do we perceive the question to be

as closed as plaintiffs suggest. See, e.g., Burleson, 308 F. Supp.

at 353 (a case cited in plaintiffs' own brief whereby court

enjoined creation of independent school district on grounds it

threatened to undermine desegregation order, but did so only .after

voter approval of secession petition at an election— the— cour-t=.

previously declined to enjoin). Thus, it may well be (although we

do not decide the matter) that before this case ripens for

adjudication the incorporation petition will not only have to be

certified for a vote but an election approving the petition must

also have taken place.

16

as respondents in the underlying Article 78 proceeding. These are

the normal costs we as a society are prepared to recognize as a

consequence of the democratic and statutory processes implicated

here; they are not the kind of "hardships" that would militate in

favor of court intervention in what is an otherwise premature

action.

In that context, we note that, especially when assessing the

hardships resulting from judicial inaction, the ripeness and

standing doctrines tend to merge. See Warth v._Seldin, 422 U.S.

490, 499 n.10 (1975) (noting "standing question thus bears close

affinity to question[] of ripeness") ; Abbott Laboratories, 387 U.S.

at 153-54 (discussing sufficiency of plaintiffs' standing in

determining whether, as matter of ripeness, hardships warranted

court action); accord 13 Wright, Miller, & Cooper § 3529, at 289;

id. § 3531.4, at 437. We add, therefore, that the injuries alleged

in the FAC, outlined supra, are not persuasive in justifying

judicial action at this time.

As to the individual plaintiffs, the claimed "denial" of

voting and housing rights is not material; no one has yet been

denied any thing or any rights (except, of course, COUP, whose

incorporation petition has been denied). As to the "threatened

denial" of these rights, the injury alleged is too remote and

speculative to support standing given the contingencies outlined

above. See Simon v. Eastern Kv. Welfare Rights Org., 426 U.S. 26,

44 (1976) (holding "unadorned speculation will not suffice" to

confer standing). In seeking analogous support for its position,

17

plaintiffs at oral argument generally referenced a case involving

hazardous fire conditions at a prison facility in which prisoners

were found to have standing to challenge those conditions. Such

were the facts and holding of DiMarzo v. Cahill, 575 F.2d 15, 18

(1st Cir.), cert, denied. 439 U.S. 927 (1978), which concluded:

"One need not wait for the conflagration before concluding that a

real and present threat exists." (Emphasis added.) We have no

quarrel with this holding; indeed, a contrary holding requiring

that prisoners first be burned before they could demonstrate

standing to challenge hazardous conditions would render the

threatened injury component of standing a nullity (and absurdity).

DiMarzo is far removed from the facts before us, however. At least

until the incorporation petition is certified, and perhaps until

voter approval also has been obtained, plaintiffs' claims of

threatened harm are too imaginary to support standing.

Finally, their claim of alleged psychic and emotional injury

resulting from the deprivation of benefits that inure with living

in a discrimination—free environment is particularly troubling.

It is true that the Supreme Court has held that Congress intended

the loss of benefits from interracial association to be sufficient

injury to confer standing under the Fair Housing Act. Trafficante

v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co.. 409 U.S. 205, 209-12 (1972). As

noted supra. however, the housing claims in this case are

particularly speculative and, as was apparent at oral argument, the

real debate on ripeness rests on the soundness of the

gerrymander/voting rights claims. As to those claims, we do not

18

think such a generous standing allowance can be engrafted. See Ad

Hoc Comm, of Concerned Teachers v. Greenburah #11 Free Union School

Dist. . No. 88-7697, slip op. at 2774 (2d Cir. Apr. 17, 1989)

(noting that, absent some statutory directive relaxing or

broadening standing requirement, deprivation of benefits of

interracial association has never been recognized as sufficient to

confer Article III standing) . We have been referred to no such

statutory allowance embodied in the Voting Rights Act, nor can we

divine one. To the contrary, it seems to us that injury of this

nature, if deemed sufficient to confer standing, inevitably will

invite friction with First Amendment freedoms. Although the

Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments surely prevent private and

public actors from carrying into practice certain discriminatory

beliefs, the First Amendment just as surely protects the expression

of discriminatory beliefs many of us find offensive as the price

of "uninhibited, robust, and wide-open" debate on public issues.

New York Times v. Sullivan. 376 U.S. 254, 270 (1964). See also

Weiss v. Willow Tree Civic Ass'n. 467 F. Supp. 803, 818 (S.D.N.Y.

1979) (Weinfeld, J.) (noting "defendants have every right to band

together [and petition the government] for the advancement of

beliefs and ideas, however unpalatable the ideas or whatever the

19

underlying motive").15

As to the institutional plaintiffs, they contend that the

basic goals of the institutions are being thwarted by the alleged

conspiracy and that this has led to a consequent diversion of

institutional resources. They believe these financial losses

confer standing under the teaching of Havens Realty_Corp.__

Coleman. 455 U.S. 363 (1982) . We disagree. In Havens, the

organizational plaintiff provided counseling and referral services

to clients in search of housing. To combat the defendants' alleged

practice of "racial steering," id. at 366 n.l, the organization was

forced to spend additional resources for its counseling and

referral services. The Court held this to be sufficient injury for

standing purposes. Id. at 379. That is very different from the

situation here, where the institutional defendants have injected

themselves into this matter in the interest of furthering their

societal goals, and have spent resources to advance their

positions. That is not Havens. Indeed, Havens reaffirms the

notion that an allegation which fundamentally asserts a "setback

to the organization's abstract societal interests" will not satisfy

the standing requirement. Id. (citing Sierra Club v. Morton, 405

U.S. 727, 739 (1972)). Stripped of its trappings, however, we

15 This does not mean, as plaintiffs apparently misperceive,

that we think discriminatory motive is irrelevant and should be

ignored by state or municipal officials in reviewing incorporation

petitions. See In re Greenberg. slip op. at 15 n.6 (and

accompanying text); id. at 29 n.ll. To the contrary, we have

stated very clearly that States are proscribed from approving

gerrymandered plans contrived due to racial animus. Id. at 14 n.5.

20

think the institutional plaintiffs in reality assert just such a

"setback."

In Sierra Club. the Court held that the plaintiff

organization's long-standing interest in protecting the environment

did not confer on it standing to challenge the Government's

development of a national park. Undoubtedly the Sierra Club had

devoted institutional resources in opposing the Government's

action, but the Court nonetheless found the Club's "special

interest" in the project and environmental problems generally to

be insufficient for standing purposes absent some personal harm.

Sierra Club. 405 U.S at 734-40. We think Sierra Club, and not

Havens. controls the issue here.16

Thus, because we find the claims as asserted to be unfit for

judicial resolution, and because we see no cognizable hardship

flowing from our decision to withhold consideration at this time,

we find that plaintiffs' claims are not ripe and counts I, II, and

III of the FAC must be dismissed.

Plaintiffs emphasized repeatedly at oral argument that the

distinguishing feature in this case is the filing of the

Of course, the institutional plaintiffs are entitled to

sue in a representational capacity on behalf of any of their

members who have been injured, but that right is derivative of the

individual member's right to sue. NAACP v. Button. 371 U.S. 415,

428 (1963) (citing NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson. 357 U.S.

449, 458-60 (1958)). Consequently, that allowance is not

implicated here in light of our earlier holdings as to the

individual plaintiffs.

We add only that we perceive certain other infirmities

related to standing, both as to the individual and institutional

plaintiffs, that we need not elaborate upon here given our holding

as to ripeness.

21

incorporation petition. Until that time, plaintiffs admit that the

COUP defendants had engaged in protected organizational activity,

but that once the concrete step of filing the incorporation

petition was taken they say the character of COUP'S conduct changed

and became actionable. For all the reasons outlined above, we

disagree; but even if plaintiffs are correct and the mere filing

of an incorporation petition renders this case fit for judicial

intervention, we think the complaint must be dismissed on a further

and very related ground — failure of subject matter jurisdiction

due to the current lack of state involvement in the conspiracy.

(b) Subject Matter Jurisdiction

Section 1985(3) provides, in pertinent part:

If two or more persons in any State or Territory conspire

. . . for the purpose of depriving, either directly or

indirectly, any person or class of persons of the equal

protection of the laws, or of equal privileges and

immunities under the laws [the "deprivation clause"]; or

for the purpose of preventing or hindering the

constituted authorities of any State or Territory from

giving or securing to all persons within such State or

Territory the equal protection of the laws [the

"preventing-or-hindering clause"]; . . . the party so

injured or deprived may have an action for the recovery

of damages occasioned by such injury or deprivation,

against any one or more of the conspirators.

Plaintiffs rely on both the deprivation and preventing-or-hindering

clauses in support of their claims. They contend that either there

has been state action in furtherance of the conspiracy's goals or,

alternatively, that state action is immaterial since the reach of

section 1985(3) extends to embrace private conspiracies. The

former conclusion is without merit and the latter, although

22

generally unassailable, see Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88,

104-06 (1971), is not controlling here.

1. The Deprivation Clause

Section 1985(3) contains no "color of state law" or "state

action" requirement. Nonetheless, it is a remedial statute; it

creates no substantive rights in itself. United Brotherhood of

Carpenters & Joiners v. Scott. 463 U.S. 825, 833 (1983) (citing

Great Am. Fed. Savinas & Loan Ass'n v. Novotny. 442 U.S. 366, 372

(1979)). Consequently, in Scott the Court made clear that if the

underlying right allegedly deprived by the purported conspiracy

derives from a proscription against state action, state involvement

in the conspiracy is a necessary predicate to the section 1985(3)

claim. Scott. 463 U.S. at 830-33. Thus, in Griffin v.

Breckenridge no state action was required since the underlying

right allegedly deprived — the constitutional right to travel —

served as a shield against both public and private conduct, whereas

in Scott state action was required since the rights allegedly

protected — First Amendment rights made applicable to the States

by the Fourteenth Amendment — are rights guaranteed only from the

excesses of state behavior. Id. at 831-33.17

To the extent Weise v. Syracuse Univ. . 522 F.2d 397, 408

(2d Cir. 1975), a pre-Scott case cited by plaintiffs, holds to the

contrary, we find that it has been overruled by Scott. We reach

the same conclusion as to similar, pre-Scott authority outside this

circuit cited by plaintiffs. But see Cohen v. Illinois Inst, of

Technology. 524 F.2d 818, 827-29 (7th Cir. 1975) (Stevens, J.)

(anticipating Scott and holding that if underlying right is

triggered by state action, section 1985(3) conspiracy to deprive

persons of that right must involve state), cert, denied. 425 U.S.

23

The plaintiffs concede that the rights allegedly deprived by

the COUP conspiracy (or, more accurately, those rights threatened

with deprivation) are rights protected only from state action.* 18

They argue, however, that the Scott state action requirement is

satisfied here. We disagree.

The conduct of private parties may be characterized as state

action generally under the following circumstances:

First, the deprivation must be caused by the exercise of

some right or privilege created by the State or by a rule

of conduct imposed by the State or by a person for whom

the State is responsible. . . . Second, the party charged

with the deprivation must be a person who may fairly be

said to be a state actor.

Lucrar v. Edmondson Oil Co. . 457 U.S. 922, 937 (1982). The

plaintiffs' position, in essence, is that COUP'S utilization of the

state-created village incorporation process satisfied the first

prong, and the town supervisor's actions in calling a public

hearing on the petition satisfies the second prong. This

943 (1976); Weiss v. Willow Tree Civic Ass'n. 467 F. Supp. 803,

811-15 (S.D.N.Y. 1979) (Weinfeld, J.) (same). We add that Justice

Stevens, who authored Cohen, joined the majority in Scott.

18 See United States v. Guest. 383 U.S. 745, 755 (1966)

(Equal Protection Clause protects individuals only from state

action); Terry v. Adams. 345 U.S. 461, 473 (1953) (Frankfurter, J.)

(Fifteenth Amendment requires state action). As to the remaining

Federal statutory rights and the state constitutional and statutory

rights, the plaintiffs do not contest the conclusion that each is

triggered only due to state action and, indeed, they expressly

"assume'' for present purposes that the federal and state voting

rights provisions apply only against state conduct. Plaintiffs'

Supplemental Brief, at 25 n.12. Thus, any reliance plaintiffs

place on Perry v. Manocherian. 675 F. Supp. 1417, 1427-28 (S.D.N.Y.

1987) is misplaced since the underlying rights allegedly deprived

in that case extended to private conduct.

24

conclusion cannot withstand even the most generous reading afforded

existing case law.

Amplifying the above test, the Lugar Court suggested that a

private person "may fairly be said to be a state actor" either

"because he has acted together with or has obtained significant aid

from state officials. or because his conduct is otherwise

chargeable to the State." Id. (emphasis added). In two decisions

rendered the same day as Lugar. the import of the "significant aid"

phraseology was made clear. In Blum v. Yaretskv. 457 U.S. 991,

1004 (1982) , patient transfers effected by a state-regulated

nursing home were held not to constitute state action since "a

State normally can be held responsible for a private decision only

when it has exercised coercive power or has provided such

significant encouragement, either overt or covert, that the choice

must in law be deemed to be that of the State." Likewise, in

Rendell-Baker v. Kohn. 457 U.S. 830, 841 (1982), personnel

decisions by a private school regulated and partially funded by the

State were found to retain their private characteristics since

those actions "were not compelled or even influenced by any state

regulation." Thus, as the Court has made clear, the mere use by

private parties of existing state procedures does not in and of

itself give rise to state action; it is only "when private parties

make use of state procedures with the overt. significant assistance

of state officials [that] state action may be found." Tulsa

25

Professional Collection Serv., Inc, v. Pope. 56 U.S.L.W. 4302, 4304

(U.S. Apr. 19, 1988) .19

That requisite measure of state support, assistance, or

compulsion is patently lacking here. COUP has invoked the state-

created procedures for village incorporation, but that alone is

not enough. The only state act allegedly in furtherance of the

scheme was the town supervisor's actions in convening and chairing

the public hearing on the petition — purely ministerial actions

he was required to take pursuant to New York law. Conversely, the

only substantive action he has taken (issuance of the December 1

Decision) was in opposition to COUP'S efforts. How, then, it

seriously can be argued that the alleged conspiracy has received

the imprimatur or assistance of the State is, to this court's mind,

an unfathomable contention.

Alternatively, plaintiffs insist that COUP has acted "together

with" state officials, Lugar. 457 U.S. at 937, characterizing the

State as a "joint participant" in the alleged conspiracy. The

State's interests, however, as manifested by the December 1

Decision, are completely antagonistic to COUP'S alleged purposes.

Thus, in Tulsa Professional, actions by an estate's

executrix in publishing a notice advising creditors of the pending

probate proceedings were found to include sufficient indicia of

state involvement. In addressing whether the published notice

satisfied due process, the Court found state action because the

executrix was appointed by probate court, and the statutory notice

requirement was not self-executing (indeed, the executrix in that

case was acting under direct court order to publish the notice).

Further, the probate court alternatively was described as being

"intimately involved" with or as playing a "pervasive and

substantial" role in the probate proceedings. Tulsa Professional.

56 U.S.L.W. at 4305.

26

State action cannot be posited on a joint-participation theory

given this posture. NCAA v. Tarkanian. 57 U.S.L.W. 4050, 4055 n.16

(U.S. Dec. 12, 1988).20 The instant facts, therefore, contrast

starkly with Dennis v. Sparks. 449 U.S. 24, 28-29 (1980), where

private parties who bribed and corruptly conspired with a local

judge were found to be state actors. Just as the alleged COUP

conspiracy cannot incorporate the Village of Mayfair Knollwood

without resort to state procedures, neither could the private

parties in Sparks effectuate their scheme (enjoining mineral

production from plaintiff's oil leases) in the absence of a court

order. It was the official action. however — issuance of a court

order corruptly obtained — and not the mere filing of a civil

complaint that provided the necessary state involvement with the

conspiracy. Likewise, in Lugar state action was found because an

ex parte order of attachment had been issued by a state court and

0

executed by the county sheriff. Lugar. 457 U.S. at 924. No such

meaningful or substantive state act in furtherance of the alleged

COUP conspiracy has occurred here.

"In the final analysis the guestion is whether 'the conduct

allegedly causing the deprivation of a federal right [can] be

fairly attributable to the State.'" Tarkanian. 57 U.S.L.W. at 4056

Indeed, we emphasize here that the project is a county-

sponsored project with the implicit, if not explicit, backing of

the State. The project developer, after all, is a not-for-profit

corporation operated by the Governor's son, Andrew Cuomo. In

addition, given this public sponsorship among other things, we

repeat a musing voiced in our remand decision, to wit, it remains

unclear to us just how incorporation of the Village of Mayfair

Knollwood will be able to stop completion of the proposed project.

27

(quoting Lugar. 457 U.S. at 937) . It would be anomalous indeed for

us to reach that conclusion here, particularly in light of the

December 1 Decision, and we decline the invitation. Since the

rights allegedly, deprived here are found in guarantees proscribing

state action, and since state involvement with the conspiracy has

not yet manifested itself in any meaningful way, plaintiffs'

reliance on the deprivation clause of section 1985(3) is

unavailing.

2. The Preventing-or-Hindering Clause

Alternatively, plaintiffs contend that COUP'S actions, if they

do not "involve" the State, broadly "affect" the State and that

this is sufficient to maintain a cause of action under the

preventing-or-hindering clause of section 1985(3). Although we do

not disagree with that conclusion, we find that the preventing-or-

hindering clause is inapplicable to this case.

Scott held that, "to make out [a] § 1985 (3) case, it (is]

necessary for [plaintiffs] to prove that the State was somehow

involved in or affected by the conspiracy." Scott. 463 U.S. at 833

(emphasis added). See also id. at 830 (must prove that "State is

involved in the conspiracy or that the aim of the conspiracy is to

influence the activity of the State"); id. at 831 (conspiracy must

"somehow involve or affect a State"). The Scott Court considered

section 1985(3) generally, and did not parse its various clauses.

28

Nonetheless, we think the "affect-a-State" language is obviously

and primarily directed toward the preventing-or-hindering clause.21

We reach this conclusion because the preventing-or-hindering

clause, by its terms, is designed to proscribe behavior that

impedes the State's ability to safeguard equal protection. Thus,

as this circuit has observed, it would be incongruous to require

state involvement if the preventing-or-hindering clause is to be

given effect since a State would rarely if ever be hindering its

own efforts. People v. 11 Cornwell Co.. 695 F.2d 34, 43 (2d Cir.

1982) . Consequently, and beyond those conspiracies depriving

people of rights secured against private conduct, the language of

section 1985(3) must be read to reach wholly private conspiracies

which "affect" (i.e., prevent or hinder) the State's ability to

secure equal protection. We think Scott so holds. Assuming the

constitutional firmness of that construction, we find that the

preventing-or-hindering clause is inapplicable to this case.

Section 1985(3) also includes two additional clauses

based on preventing an individual from evidencing his or her

support for presidential electors or members of Congress which, it

appears, have rarely been invoked. A fifth and final clause of the

statute merely outlines the remedy available and is not implicated

by the analysis in Scott.

We hasten to emphasize that Scott did not address the

underlying constitutional premise to this construction, to wit:

If the preventing-or-hindering clause reaches wholly private

conspiracies infringing equal protection rights, on what

constitutional authority did Congress act in passing such a

statute? Put differently, "the question [is] whether Congress has

the power under section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment to extend

Fourteenth Amendment guarantees to purely private conduct." 11.

Cornwell. 695 F.2d at 43. This issue has been left open by the

Court, see Griffin. 403 U.S. at 107, and we need not pass upon it

now given our ultimate holding.

29

In 11 Cornwell. the Second Circuit concluded that the

preventing-or-hindering clause must reach private conspiracies

since "there would almost never be a situation in which the State

would be involved in hindering its own efforts to secure equal

protection to its citizens . . . 11 Cornwell. 695 F.2d at 43

(emphasis added). The "almost-never" situation referenced by the

court is, in our view, exactly the scenario manifested by the

instant facts. The COUP defendants, in the absence of state

involvement, cannot effectuate their goal of incorporating the

Village of Mayfair Knollwood and, following therefrom, deprive

plaintiffs of allegedly protected voting and housing rights. To

the contrary, the town supervisor (who has been delegated initial

review authority by the State pursuant to New York's Village Law,

supra note 2) must first approve the petition and that approval,

if challenged, must then survive review by the State courts via an

Article 78 proceeding. Until the State acts, therefore, either

through the town supervisor or the State courts, the COUP petition

cannot prevent or hinder the State in its efforts to secure equal

protection of the laws (assuming the validity of the substantive

deprivations here alleged). Put differently, the State must

affirmatively act in this case if equal protection rights are to

be infringed, bringing these facts within the "almost-never"

situation alluded to in 11 Cornwell. The preventing-or-hindering

clause, therefore, is inapplicable.

This analysis, it seems to us, is further compelled by section

1985(3)'s injury requirement. For a cognizable claim to exist, the

30

*

statute, outlined supra, requires an act in furtherance of the

conspiracy which injured plaintiff in his or her person or

property. The Supreme Court has referred to the injury requirement

as a jurisdictional element of a section 1985(3) claim. See Scott.

463 U.S. at 828-29 (citinq Griffin. 403 U.S. at 103) . Cf. Nalle

v. Oyster. 230 U.S. 165, 182 (1913) (noting "well-settled rule is

that no civil action lies for a conspiracy unless there be an overt

act that results in damage to the plaintiff") (emphasis added).

Whatever else Scott or 11 Cornwell may hold as to private

conspiracies under section 1985(3), they could not and did not

vitiate the statutory injury requirement in such cases. Thus,

since we believe that no cognizable injury can result here or even

be sufficiently threatened until the State acts to give effect to

COUP•s efforts, supra Section 11(a), the preventing-or-hindering

clause cannot be applicable on these facts unless the

jurisdictional prerequisite of injury is to be read out of the

statute. Yet, if plaintiffs' broad reading of Scott is correct

(i.e., the alleged conspiracy is actionable simply because it

affects the State even though not one of the conspiracy's purported

harms can be effected without State assistance), then that would

very much be the result here.23

We add that since not even threatened injury is

cognizable here, we need not decide whether threatened injury alone

is sufficient to sustain a claim under section 1985(3). We may

assume that it is (notwithstanding our reservations to the

contrary), for even that lessened threshold cannot be met here.

31

4

Plaintiffs rely for their argument on a trilogy of cases in

which the preventing-or-hindering clause was invoked in support of

claims against private conspiracies. Each case, however,

represents what we believe to be the paradigmatic facts amenable

to a claim under this clause, viz, a claim where private parties,

on their own accord and without need of affirmative State

assistance in furtherance of the conspiracy's efforts, were able

to affect the State's ability to safeguard equal rights. Reliance

on those case, therefore, is inapposite. See 11 Cornwell. 695 F.2d

at 43 (colorable preventing-or-hindering claim where private

conspirators had bought at private sale a home they knew the State

had already targeted for use in the effort to deinstitutionalize

mentally retarded persons, and the conspirators thereafter refused

to sell the home to the State for the envisioned use); Brewer v.

Hoxie School Dist. No. 46. 238 F.2d 91, 93-94, 103-05 (8th Cir.

1956) (private conspiracy had prevented and hindered school board

in carrying out desegregation effort where conspirators had already

committed numerous acts of trespass on school property, threatened

and intimated board members, and attempted to persuade students to

boycott schools, thereby causing cancelation of a school session,

reduction in school attendance, and loss of school revenues); New

York State Nat'l Ora, for Women v. Terry. 704 F. Supp. 1247, 1260

(S.D.N.Y. 1989) (anti-abortion protesters were impeding State's

ability to secure for "women who choose abortion equal access to

medical treatment" through unannounced, mass protests at abortion

clinics that were designed to and did impede state's efforts to

32

4

ensure access to those clinics) .24 The crucial feature

distinguishing this case is that COUP cannot hinder the State in

its efforts to secure equal protection unless and until the State

approves the incorporation petition. Indeed, as evidence of that

fact, we were told at oral argument that the housing project is

moving forward apace, with an environmental review now underway.

Consequently, we find that plaintiffs have failed to state a

claim under section 1985(3).25

III. ATTORNEY'S FEES OR SANCTIONS

The COUP defendants move for attorney's fees under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988 ("section 1988") or sanctions under Rule 11. We may award

a prevailing defendant attorney's fees under section 1988 if the

complaint was unreasonable, frivolous, or groundless, Eastwav

Constr. Coro, v. City of New York. 762 F.2d 243, 252 (2d Cir.

We add that in each of these cases the state actor

allegedly being hindered was a named or intervening plaintiff. In

this case the state actor (Town Supervisor Veteran) is a named

defendant. Since we find the preventing-or-hindering clause

inapplicable in any event, we do not ascribe any significance to

this fact (although it adds certain confirmation to our conclusion

that this is really a deprivation clause case).

Having found that the absence of state action in this

case dooms the section 1985(3) counts, we do not conclusively

address whether the deprivation of the state rights here asserted

may alone serve as the predicate for a section 1985(3) count. See

Scott. 463 U.S. at 833-34 (generally leaving open that question);

Traqqis v. St. Barbara's Greek Orthodox Church. 851 F.2d 584, 586-

91 (2d Cir. 1988) (same) . Nor do we address whether all of the

underlying rights herein alleged, federal or state, may serve as

predicates for a section 1985(3) claim.

33

♦

#-

1985) , and sanctions under Rule 11 if the complaint was not

reasonably believed to be grounded in law or in a good-faith

argument for the law's extension, id. at 254. Neither test has

been met here.

Although we have disagreed with the arguments made by

plaintiffs' counsel, we think the arguments made were reasonable

and in good faith and the case touches (albeit prematurely) on

matters involving certain substantial and important federal rights.

Consequently, we think an award of fees or sanctions would be both

improvident and unsupported, and the motions are denied.

Conclusion

For all of these reasons, we hold that, as to the COUP

defendants, this case is not yet ripe for decision or,

alternatively, that a cognizable federal claim has not been

asserted. In reality, of course, our holding as to subject matter

jurisdiction is largely the substantive manifestation (no state

action) of the procedural infirmity (ripeness) that afflicts this

case. Simply put, we believe that until the State acts to give

some effect to COUP'S incorporation efforts, this matter is simply

inappropriate for judicial intervention. Not only does this

conclusion reflect both our concern for federalism and our respect

for the political process, the predominant currents running through

our remand decision, but it is bottomed on legal principles that

determine when and why a Federal court may act to issue injunctive

relief and award compensatory damages, the issues relevant here.

34

4 A

Counts I

Dated:

, II, and III of the FAC, therefore, are dismissed.

SO ORDERED.

White Plains, N.Y.

June 28, 1989

A . .

GERARD L. GOETTEL

U.S.D.J.

35

;

+ li >* i

!

® 1 9 7 6 J U L I U S B L U M 8 E R G . INC .

4 - >

STATE OF NEW YORK, COUNTY OF

I, the undersigned, an attorney admitted to practice in the courts of New York State,

xoCO

©Z

9oQ.a<

o

□

□

Certification

By Attorney

Attorney's

Affirmation

certify that the within

has been compared by me with the original and found to be a true and complete copy,

state that I am

the attorney(s) of record for

in the within action; I have read the foregoing

and know the contents thereof; the same is

true to my own knowledge, except as to the matters therein stated to be alleged on information and belief, and as

to those matters I believe it to be true. The reason this verification is made by me and not by

The grounds of my belief as to all matters not stated upon my own knowledge are as follows:

I affirm that the foregoing statements are true, under the penalties of perjury.

Dated:

The name signed must be printed beneath

STATE OF NEW YORK, COUNTY OF ss.:

I, being sworn, say: I am

in the within action; 1 have read the foregoing

and know the contents thereof; the same is true to my own knowledge, except as to

the matters therein stated to be alleged on information and belief, and as to those matters I believe it to be true,

the of

a corporation and a party in the within action; I have read the foregoing

and know the contents thereof; and the same is true to my own knowledge,

except as to the matters therein stated to be alleged upon information and belief, and as to those matters I believe

it to be true. This verification is made by me because the above party is a corporation and 1 am an officer thereof.

The grounds of my belief as to all matters not stated upon my own knowledge are as follows:

I □ Individual

Verification

ID Corporate

Verification

Sworn to before me on 19 .........................................................................

The name signed must be printed beneath

STATE OF NEW YORK, COUNTY OF ss.: ( If both boxes are checked indicate after names, type of service used.)

I( being sworn, say: 1 am not a party to the action, am over 18 years

of age and reside at

On 19 I served the within

x r “ l Service

§ I__ I By Mail©.o«o

^ Personal

£ L -J Service on

Individual o ©.cO

by depositing a true copy thereof in a post-paid wrapper, in an official depository under the exclusive care and

custody of the U.S. Postal Service within New York State, addressed to each of the following persons at the last

known address set forth after each name:

by delivering a true copy thereof personally to each person named below at the address indicated. 1 knew each

person served to be the person mentioned and described in said papers as a party therein:

Sworn to before me on 19

The name signed must be printed beneath

t

Index No. 88 CIV 7738 (GL&^r 19 89

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK= ►=

YVONNE JONES, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

-against-

LAURENCE DEUTSCH, et al.,

Defendants.

NOTICE OF ENTRY OF OPINION AND ORDER

Q U I N N & S U H R

Attorneys fo r Defendant

Office and Post Office Address, Telephone

170 HAMILTON AVENUE

W h i t e P l a i n s , N e w Y o r k 1 0 6 0 1

(9 1 4 ) 9 4 9 - 0 8 0 0

To

Attorney(s) for

Service of a copy of the within is hereby admitted.

Dated,

Attorney(s) for

Sir:— Please take notice

□ ryD T IC E O F EN TRY

that the within is a (certified) true copy of ^ OPINION AND ORDER

duly entered in the office of the clerk of the within named court on j une 28

□ N O TIC E O F S E T T L E M E N T

that an order of which the within is a true copy will be presented for

settlement to the HON. one of the judges

of the within named court, at

on 19 at M.

Dated, WHITE PLAINS , NY

JUNE 2 8 , 1989

To Counsel of Record

Attorney(s) for

Yours, etc.

Q U I N N & S U H R

Attorneys for

Office and Post Office Address

170 HAMILTON AVENUE

W h i t e P l a i n s , N e w Y o r k 1 0 6 0 1

1 3 0 1 — JU L IU S B LU M BER G , INC., LAW BLANK PU B LIS H E R S. NYC 1 0 0 1 3