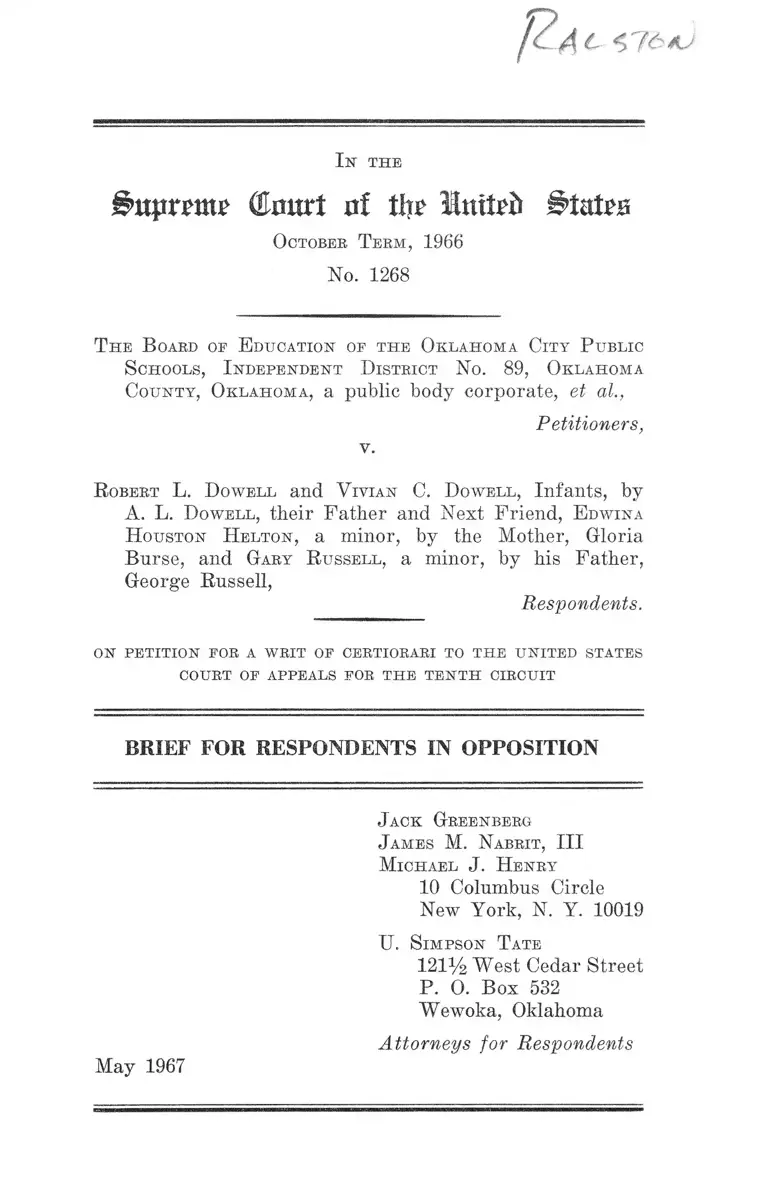

Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief for Respondents in Opposition

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief for Respondents in Opposition, 1967. 9f564827-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5eb0493c-3d8e-4be9-a2df-72109aed88ff/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-brief-for-respondents-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

î ttprnn? (Enurt nt tlit little States

O ctober T erm , 1966

No. 1268

T he B oard oe E ducation of th e O k lah om a C ity P ublic

S chools, I ndependent D istrict N o . 89, O klahom a

Co u n ty , O k la h o m a , a public body corporate, et at.,

v.

Petitioners,

R obert L. D owell and V ivian C. D ow ell , Infants, by

A. L. D ow ell , their Father and Next Friend, E d w in a

H ouston H elton , a minor, by the Mother, Gloria

Burse, and G ary R ussell, a minor, by his Father,

George Russell,

Respondents.

o n p e t it io n fo r a w r it of certiorari to t h e u n it e d states

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

M ichael J. H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

U. S im pson T ate

121% West Cedar Street

P. O. Box 532

Wewoka, Oklahoma

Attorneys for Respondents

May 1967

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Citations to Opinions Below ......................................—- 1

Jurisdiction ..... ............... ......... -.......................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 2

Question Presented .......... ............. - .............. -........ —...... 2

Statement ............. ...........................................-.....—-........... 3

I. Legal Segregation in the Oklahoma City Public

Schools and Practices Which Continued Segre

gation, from 1907 to Date of District Court’s

Order .................................. .......... -........ -................ 4

A. Legal Segregation in Oklahoma City ...... . 4

B. Practices Which Continued Segregation in

the Public Schools After 1955—Zoning,

Transfer Policies, and Faculty Assign

ments .... ................ ................. -.......................... 6

II. The District Court’s Order Authorizing An

Expert Study to Formulate an Adequate Plan

for Desegregation of the Oklahoma City Public

Schools .......... ................... ...... ......... -...... -............ 10

III. The Expert Panel’s Analysis of the Deficiencies

of the School Board’s Approach to Desegrega

tion, and Their Proposals for An Adequate

Plan of Desegregation .................................... 13

A. The Adequacy of the Overall Approach .... 13

B. Transfer Policies ............................................ 15

PAGE

11

PAGE

C. Zoning and Attendance Areas ..................... 18

D. Faculty Assignments...................................... 21

E. In-Service Education of Faculty ................. 24

IV. The District Court’s Order Requiring an Ade

quate Plan of Desegregation, and Specifying

Certain Minimum Components of Such a Plan

Based Upon Recommendations of the Expert

Panel ........................................................................ 26

V. The Opinion of the Court of Appeals ............... 30

A rgument—

I. The Decisions Below Are Clearly Correct ....... 33

A. There Was Overwhelming Evidence of the

Existence and Continuation of Segregation

in the Oklahoma City School System ......... 33

B. The Expert Testimony Provided a Reason

able Basis for the District Court’s Order .... 35

II. There Is No Conflict of Decision ....................... 37

A. The Decision of the Court of Appeals Is

Clearly in Accord With Recent Major Deci

sions of the Other Circuits on the Implemen

tation of Desegregation Relief in School

Systems Where There Has Been Legal

Segregation ............................ ....................... - 37

B. The Decision of the Court of Appeals Is

Clearly Consistent With Decisions of This

Court on School Desegregation .................. 42

Conclusion ...................................................................................... 47

Ill

T able op Cases

PAGE

Bell v. School City of Gary, Inch, 324 F.2d 209 (7th

Cir. 1963), cert. den. 379 U.S. 924 .............................. 38

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, Va.,

382 U.S. 103 (1965) ......... .......................... ................... 46

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C. 1955) .... 38

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483

(1954); 349 U.S. 294 (1955) .......................... 42,43,44,45

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) 43

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.2d

988 (10th Cir. 1964), cert. den. 380 U.S. 914 ............. 38

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683

(1963) ............ ......................... ........... ......... ........ 8, 34, 38, 45

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) ...................... ................. 45

Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public School Dis

trict No. 22 et al., 8th Cir., No. 18,528, April 12,

1967) .............................................. - ..... ...... .......40,41,42,46

Kelley v. Board of Education of Nashville, 270 F.2d

209 (6th Cir. 1959), cert. den. 361 U.S. 924 ............. . 38

Louisiana et al. v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) 45

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ...... ............ ........... 44, 46

Schine Chain Theatres, Inc. v. United States, 334 U.S.

110 (1948) ........................................................................ 45

United States v. Bausch & Lomb Optical Co., 321 U.S.

707 (1943) 45

IV

United States et al. v. Jefferson County Board of Edu

cation et al., 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), re-affirmed

en banc, 5th Cir., Civil No. 23345, March 29, 1967 .....37,

38, 39, 40,46

United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U.S. 319

(1947) ................................................................................ 45

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1 (1910).... 45

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 363 F.2d

738 (4th Cir. 1966) ........................................................ 46

O th er A uthorities

United States Office of Education, Revised Statement

of Policies for School Desegregation Plans (March

1966) implementing Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C.A. §2000d) .......................39, 41, 46

PAGE

In t h e

Bnpum? ( J J m t r t n ! % I n t t p f c U t a t v a

O ctober T erm , 1966

No. 1268

T h e B oard of E ducation of th e O k lah o m a C it y P ublic

S chools, I ndependent D istrict N o. 89, O klahom a

Co u n ty , O k la h o m a , a pub lic b o d y corp ora te , et al.,

Petitioners,

v .

R obert L. D owell and V ivian C. D ow ell , Infants, by

A. L. D ow ell , their Father and Next Friend, E dw ina

H ouston H elton , a minor, b y the Mother, Gloria

Burse, and Gary R ussell, a minor, b y his Father,

George Russell,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

Citations to Opinions Below

There were two opinions of the District Court. The

first (R. 50-82) is reported at 219 F.Supp. 427. The second

(R. 147-165) is reported at 244 F.Supp. 971. The opinion

of the Court of Appeals is unreported and is printed in

Appendix A of the Petition.

2

Jurisdiction

The jurisdictional requisites are adequately set forth

in the Petition.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, and 42

U.S.C. §1983 providing a right of relief in equity for

violations of constitutional rights. These are set forth

in Appendix C of the Petition.

Question Presented

Whether after finding that a school system was still

legally segregated contrary to Brown v. Board of Educa

tion and that the school board refused to undertake an

effective program of desegregation, it was within the

power of a district court to order an independent expert

study of the school system to he made and then to order

the school board to adopt the recommendations of the

expert panel of minimum components of an adequate plan

of desegregation.

Statement*

This is a class action suit by Negro students against the

Oklahoma City Board of Education and its agents to en

join them “ from continuing to enforce rules, regulations,

and procedures which affect and result in the maintenance

of segregated schools in Oklahoma City, . . . from assigning

plaintiffs and the members of the class they represent to

racially segregated schools, . . . and from refusing to

adopt and execute plans to eliminate existing patterns

of racial segregation in the public schools of Oklahoma

City” (B. 39-41). The district court granted the requested

relief in two opinions and orders, the first on July 11,

1963 (B. 50-82), and the second on September 7, 1965

(B. 147-165). The latter order requires the board of

education to develop and institute an effective plan of

desegregation and specifies certain minimum components

of an adequate plan. The board appealed this order to

the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit,

which affirmed the order except for one provision in an

opinion on January 23, 1967, rehearing denied March 15,

1967. The board of education now seeks review of this

judgment on certiorari.

* This brief in opposition is longer than is usual because the issues

depend, to a great extent, on the evidence, and the petition contains an

incomplete statement of the facts and proceedings.

4

I. Legal Segregation in Oklahoma City Public Schools and

Practices Which Continued Segregation, from 1907 to

Date of District Court’s Order.

A. Legal Segregation in Oklahoma City.

For nearly fifty years, from the time of its admission

into the Union in 1907, the State of Oklahoma maintained

legally required segregation of Negro and white students

in public education as well as segregation of the races in

other public activities (R. 56). The Constitution of Okla

homa, Article XIII, Section 3, provided: “ Separate schools

for white and colored children with like accommodation

shall be provided by the Legislature and impartially main

tained” (R. 56).

This state constitutional requirement was implemented

by laws (Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes, Sections 5-1 through

5-8 and 5-11), providing that (1) “ The public schools

of the State of Oklahoma shall be organized and main

tained upon a complete plan of separation between the

white and colored races . . (2) members of each dis

trict school board must be composed exclusively of mem

bers of the majority race; (3) private educational insti

tutions must also be completely segregated; (4) any

teacher or school official who permits a child to attend

a school with members of the other race is guilty of a

misdemeanor; (5) any student who attends a school with

members of the other race is guilty of a misdemeanor;

and (6) transportation will be furnished to other districts

by those districts which do not maintain schools for a

particular race (R. 56-58). It is undisputed that Oklahoma

did in fact maintain the completely segregated educational

system required by its laws for nearly fifty years, until

the time of the second Brown decision in 1955.

In addition to the laws requiring segregation in all

major public activities of the State, the district court

found that residential segregation was customary and

legally supported by statute and court enforcement in

Oklahoma over a long period of time:

[W]hen new additions were added to the cities and

towns in Oklahoma, it was generally the practice of

the developers to provide in the plats restrictive

covenants on lands used for new homes or dwelling

places, prohibiting the sale of lands or lots or the

ownership by persons of the Negro race. These restric

tive covenants also generally provided some penalty

for an attempt to violate them. In the case where

lands or lots were sold at a tax sale in Oklahoma,

these restrictive covenants survive the sale (68 O.S.A.

Section 456) (R. 58).

The district court also found that this general state prac

tice of residential segregation with its supporting legal

structure existed in Oklahoma City:

The residential pattern of the white and Negro people

in the Oklahoma City school district has been set

by law for the period in excess of fifty years, and

residential pattern has much to do with the segrega

tion of the races. . . . The east and southeast portion

of the original city of Oklahoma City was Negro,

and all other sections and districts of the original

city of Oklahoma City were occupied by the white

race. Thus the schools for Negroes have been centrally

located in the Negro section of Oklahoma City, com

prising generally the central east section of the city

(R. 59).

6

B. Practices JFhich Continued Segregation in the

Public Schools After 1955— Zoning, Transfer

Policies, and Faculty Assignments.

As a response to this Court’s decision in Brown v.

Board of Educat-ion, the Oklahoma City Board of Educa

tion adopted the following policy statement:

Statement Concerning Integration Oklahoma Public

Schools 1955-1956

August 1, 1955

All will recognize the difficulties the Board of Edu

cation has met in complying with the recent pro

nouncement of the United States Supreme Court in

regard to discontinuing separate schools for white

and Negro children. The Board of Education asks

the cooperation and patience of our citizens in its

compliance with the law and making the changes that

are necessary and advisable. This action requires the

Oklahoma Board of Education to change a system

which has been in effect for centuries and which is

desired for many of our citizens.

Boundaries have been established for all schools.

These boundaries are shown on a map at the City

Administration Building and maps are being dis

tributed to each school principal. These new bounda

ries conform to the policies always followed in estab

lishing school boundaries. They consider natural

geographical boundaries, such as major traffic streets,

railroads, the river, etc. They consider the capacity

of the school. Any child may continue in the school

where he has been attending until graduation from

that school. Requests for transfers may be made and

each one shall be considered on its merits and within

the respective capacity of the buildings (R. 60).

7

Thus the board of education, as compliance with the

Brown decision, undertook only to redraw school bound

aries to eliminate obvious duality of zones based on race.

Certain new school boundaries were established (R. 61).

The formerly Negro Douglass High School and related

Negro “ feeder” elementary schools in the east central area

of Oklahoma City were zoned in such a way as to remain

predominantly Negro schools, relying upon patterns of

residential segregation which had previously been estab

lished under the dual system. Many of the remaining

white families moved out of the east central area (R. 61).

As the number of Negro families in the east central

area increased, the facilities of Douglass High School were

enlarged considerably through the use of temporary or

portable classrooms until an enrollment of 1,820, the

largest in the school system, was reached—while North

east High School (in an adjacent white area) continued

at an enrollment of 1,215 students without any temporary

or portable facilities (R. 68, 74). This arrangement was

in lieu of a re-zoning which would have distributed stu

dents more evenly among the various high schools, but

which would have lessened the amount of racial segregation.

With respect to the assignment of high school students

from dependent school districts (those without high

schools) outside the city to high schools within the city,

school officials continued their policy of assigning Negroes

to “Negro” schools and whites to “white” schools (R. 64).

Negro plaintiff Robert Dowell was automatically assigned

to all-Negro Douglass High School when he sought ad

mission to the Oklahoma City high schools from outside

the city (R. 63-64).

The effects of the relatively small amount of integra

tion which necessarily took place because of the consolida

8

tion and elimination of dual school zones were counter

acted, the district court found (JR. 79), by the board of

education’s “minority to majority” transfer policy which

was maintained through 1963 until invalidated under

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, 373 U.S.

683 (1963) by the original district court order. The board

had theretofore followed a policy statement which pro

vided :

It is the policy of the school board to consider, pass

upon and to practically always grant the applications

of parents for the transfer of their children from

schools where the children’s race is in the minority

to a school or schools solely of the child’s race or in

which the child’s race is in the majority providing

that transfers under policy last above described be

granted only when it is the opinion of the parents

of the child and the district that such transfer is

necessary for the best interest of the child as a pupil

(R. 70).

The board assumed that “the best interest of the child as a

pupil” was that he not be “unhappy” as a result of being in

a minority racial position, and that this unhappiness was

sufficiently evidenced by the parents’ request to change

schools (R. 66). The district court found that “ the policy

set forth in this resolution is the same policy the school

board has followed at all times since 1955. There can be

no argument but that such a policy is designed to per

petuate and encourage segregation . . . ” (R. 70).

The combination of the board’s zoning and transfer

policies successfully limited desegregation, as is indicated

by a comparison of the racial composition of individual

schools for 1959-60 and 1964-65:

Total

Schools White

9

Negro Integrated

1959-60 73 12 7

1964-65 81 14 12

(R. 97)

Elementary

Schools White Negro Integrated

1959-60 62 9 6

1964-65 67 11 9

(R. 100)

Secondary

Schools White Negro Integrated

1959-60 11 3 1

1964-65 14 3 3

(R. 103)

Note: The working definition of an “ integrated” school used by the

expert panel appointed by the district eourt was a school which

is less than 95% white or less than 95% non-white.

Additionally, there were 13 new elementary schools in

operation in 1964-65 which had not been in operation in

1959-60 (some of the old schools had been closed down or

combined), and all of these were segregated—11 com

pletely so and 2 with 99% members of one race (R. 99).

There were 6 new secondary schools in operation in 1964-65

which had not been in operation in 1959-60, and 5 of these

were completely all-white or all-Negro (R. 101-102). There

were white high school students who lived in the all-Negro

Douglass High School area but none attended Douglass

in any of the years from 1954-55 through 1962-63 (R. 65).

The district court concluded in its original opinion of

July 11, 1963 that “ since August 1, 1955, the only integra

tion has been in the fringe areas as between minority

10

Negro residential pattern and the majority white resi

dential pattern” (R. 79), and “that evidence of gerry

mandering or otherwise of maintaining separate and dis

tinct schools for Negroes and schools for whites can be

seen in a review of the testimony” (R. 77).

Racial segregation was further preserved by the board’s

teacher assignments since 1955. The district court found

that “during the school year 1954-55 there were no Negro

teachers assigned to teach white students in the white

schools or white and Negro schools where the white stu

dents were predominant and the same was true for the

year 1961-62 and all years in between” (R. 65). The

Superintendent stated the reason for this policy, indicat

ing his belief in the undersirability of contact between

members of different races: “I have advised the Board

and have concluded that nothing would be gained educa

tionally by a desegregation of staffs and that as a matter

of fact the appointment of Negro teachers in certain

schools and the mixing of staffs could very well detract

from the quality of the instructional program in Oklahoma

City; and that there would be only one reason that I

could think of for doing this, and it would not be an

educational reason. It would be merely for the sake of

integration . . . ” (R. 76).

II. The District Court’s Order Authorizing An Expert

Study to Formulate an Adequate Plan for Desegrega

tion of the Oklahoma City Public Schools.

Based on the foregoing, the district court concluded

in its original opinion of July 11, 1963, that “ the School

Board has not acted in good faith in its efforts to integrate

the Oklahoma City Public Schools, as defined and required

in the Brown cases, as to pupils and personnel” (R. 76).

This finding of lack of good faith was based primarily on

11

the results, described above, of the board’s approach to

desegregation—by which the system had remained pre

dominantly segregated (R. 76-77). The court also noted

as an element of this finding of lack of good faith, the

failure of the board to engage an expert who is familiar

with the particular problems raised by the duty to desegre

gate a school system (R. 79). The court then ordered the

school board to file a comprehensive plan of desegregation

(R. 82).

The school board adopted another “Policy Statement”

on January 14, 1964, in response to the court’s order,

which stated the general purposes of the Oklahoma City

public schools, the policy of attendance zones based on

“neighborhood schools,” certain criteria for the granting

of special transfers, and the existence of opportunity for

any teacher to apply for any position in the system (R.

105-108). Concluding that this policy statement would still

be inadequate to achieve desegregation of the Oklahoma

City public schools, the district court at the hearing on

the plan on February 28, 1964, suggested that petitioner

school board employ an outside expert in educational

administration to analyze the problem and make pro

posals for an effective plan of desegregation, and that if

they chose not to do so he would invite the plaintiffs to

do so (R. 199-202). Petitioner school board refused to

employ such an expert (R. 83-84). Respondents then moved

for authority to undertake such a study (R. 87-88), which

motion was granted by the court on June 1,1964 (R. 90-91).

The experts commissioned to undertake the study were:

(a) Dr. William R. Carmack, Director, Southwest Center

for Human Relations Studies, The University of Okla

homa, Norman, Oklahoma. Dr. Carmack advised that per

sonnel of the Human Relations Center under his super

vision were prepared and qualified to gather information

12

concerning school curriculnms, pnpil distribution, faculty

distribution, school zones, transfer procedures and other

relevant facts necessary for the proper evaluation of the

problem, (b) Dr. Willard B. Spaulding, Assistant Director,

Coordinating Council for Higher Education, San Fran

cisco, California. Dr. Spaulding is considered one of the

outstanding educators in the nation. He has wide ex

perience in public school administration, having served as

Superintendent of Schools in Massachusetts, New Jersey

and Oregon. He is a former Dean of the College of Edu

cation of the University of Illinois and Chairman of the

Division of Education of Portland State College. He is

the co-author of several books on education, including

The Public Administration of American Schools and

Schools And National Defense, (c) Dr. Earl A. McGovern,

Administrative Assistant to the Superintendent of New

Rochelle Schools, New Rochelle, New York. Dr. McGovern

has been in school administration since 1955 and was then

involved in the research and evaluation problems in the

New Rochelle school system’s efforts to achieve desegrega

tion of its public schools (R. 88).

The report of the expert panel was completed and filed

on January 20, 1965 (R. 123).1

1 The complete report is printed in the record at R. 92-132.

13

III. The Expert Panel’s Analysis of the Deficiencies of

the School Board’s Approach to Desegregation, and

Their Proposals for An Adequate Plan of Desegrega

tion.

A. The Adequacy of the Overall Approach.

Pursuant to order of the court the expert panel analyzed

both the adequacy of the school board’s approach as a

whole, and that of basic elements within it. The total

school population of the Oklahoma City Public Schools

in 1964-65 was 73,963, with 44,019 elementary and 29,244

secondary students (R. 95-100). The percentage of white

and non-white pupils has remained relatively stable over

the last six years with the white population decreasing

slightly from 86.4% to 83.1% while the non-white popula

tion increased from 13.6% to 16.9% (R. 95). The total

number of schools in 1964-65 was 107, with 87 elementary

and 20 secondary schools (R. 95-102).

With regard to the adequacy of the overall approach,

they concluded: “In overview it may be said the policy

statement of the Oklahoma City Board of Education is

not a plan to be followed to achieve integrated public

education in Oklahoma City” (R. 108). Dr. Spaulding,

the member of the expert panel who took primary respon

sibility for the section of the report dealing with the over

all approach, amplified this statement in his oral testimony.

He said: “ First, I would like to state that I do not con

sider this a plan. As I understand planning in the area

of public school administration, and I think I know this

quite well, a plan requires a clear statement of the goals

that will be achieved. It [includes] the description of what

is going to be done to achieve those goals. Thirdly, it

indicates the personnel who are going to be assigned to

these tasks; and fourthly, it includes a time schedule in

14

dicating the steps to be accomplished at particular times,

and the time in which the goal is to be reached” (R. 263).

In analyzing the board’s two stated purposes of public

education in Oklahoma City of (1) providing the best

possible educational program for every pupil, and (2) pro

viding equal educational opportunity for all without refer

ence to any hereditary or environmental differences, the

expert panel pointed out in their report that “ equal oppor

tunity to profit from the best possible educational pro

grams occurs most frequently when programs are designed

to meet individual differences among pupils. When such

differences are found to exist in substantial numbers of

cases, wise educational planning yields adaptations of

programs so that all students . . . may learn from them”

(R. 108). They also noted that the Oklahoma City public

schools now provide programs which are adapted to a

number of pupils, such as those for the physically handi

capped, slow learners, youth with special social and eco

nomic problems, etc. (R. 109). Dr. Spaulding again ampli

fied these statements in oral testimony: “It seems to me

that these two statements [of purposes] are self-contra

dictory. If one is to provide the best possible educational

program for every pupil, then one must necessarily take

into account the individual differences which exist and

which exist among wide numbers of students . . .” (R.

263-264).

Dr. Spaulding suggested that it is impossible to have

an effective desegregation plan without considering factors

of race, economic background, etc., since a system that at

one time had been segregated cannot be effectively deseg

regated unless affirmative steps are taken (R. 270). For

example, he said, “I think we recognize that in any school

system which was segregated, that the location of build

ings was determined by the pattern of segregation rather

15

than by criteria which might have been used otherwise.

Obviously if one is going to have a school into which only

Negroes would be assigned, it is located in an area where

Negroes can be assigned to it . . . so that generally in

school systems of this character, the location of individual

buildings is not the same as would be found in a city which

was not segregated from the beginning” (R. 270-271).

He concluded that the failure to do more than simply issue

a policy statement that “we no longer believe in segregated

schools” would be ineffective in changing the patterns of

a segregated system (E. 271-272).

Dr. McGovern, in oral testimony, noted that during the

five year period of the operation of the school system

which the panel studied, some small progress in terms

of the number of integrated schools had been made. How

ever, he concluded: “As we examined it, we kept turning

these things over, it became more obvious that this was

not anything, that this was not due to any overt action

I believe on the part of the Board of Education to provide

for an integrated school system” (R. 214).

B. Transfer Policies.

Dr. McGovern, who took primary responsibility for the

section of the report dealing with transfers, pointed out

that the board’s present transfer policy continues to per

petuate the segregationist effects of the “minority to

majority” policy which was invalidated in 1963. Up until

that time there had been four or five thousand transfers

annually (R. 218).

Under the present policy, a pupil who successfully trans

ferred under the “minority to majority” policy before

1963 is allowed to remain in the school to which he trans

ferred. Furthermore, a brother or sister of such a student

may also obtain a transfer to that school under the policy

16

permitting transfers to make it possible for two or more

members of the same family to attend the same school

(R. 218, 107). Based on detailed statistical study, he also

said that the “good faith” transfer criterion further pro

vided white pupils with an effective loophole for escaping

from integrated school situations (R. 220, 113). He con

cluded that under the board’s present policy it is still

possible for many parents to achieve the same results

as they might have under the “minority to majority” racial

transfer policy (R. 223-224).

Dr. McGovern also noted that the result of some whites

getting transfers out of schools with Negroes is an ever

increasing tendency of remaining whites to also attempt

to transfer out (R. 221). The effects of these transfer

policies in preserving and fostering segregation could not

be remedied simply by ending the particular policies in

question, since they have, in concert with the board’s

zoning policies and the residential restrictions on Negroes,

caused most of the schools to become clearly identified

as “white” or “ Negro” schools (R. 109, 221, 298).

As a remedy for the effects of these transfer policies

in perpetuating and increasing segregation, the expert

panel proposed a “majority to minority” transfer policy

which would turn the old “minority to majority” policy

inside out (R. 115). The “majority to minority” policy

would permit an elementary school pupil, if he were in a

majority group, to transfer to a school in which he was

in a minority. Thus if the attendance area for a school

was predominantly Negro (over 50%), Negro pupils could

transfer out. However, Negro pupils could transfer

only to schools in which they would be in a minority, i.e.,

white schools (over 50%) (R. 115). The report said:

“A dmittedly, due to present circumstances, it is not likely

that many white pupils would take advantage of this policy,

17

but it would provide Negro pupils— especially those who

care enough—with a way for escaping from the restrictions

of the present neighborhood school plan” (R. 115). In

support of this proposal as a workable means of helping

to remedy the past effects of segregation within the con

fines of the present school system, the report emphasized

the considerable amount of excess capacity available, partic

ularly in the elementary schools (R. 116).2

In amplifying this recommendation in oral testimony,

Dr. McGovern noted that the panel had carefully con

sidered the capacity of the various schools in the system.

It was for this reason that they avoided an open enroll

ment or free transfer plan where everybody could just

go to the school they wished (R. 230). It was pointed out

by Dr. Carmack that “this is not a plan that completely

ignores attendance boundaries or the so-called neighbor

hood concept. This is in fact in relation to some other

plans that are being utilized, a relatively modest plan”

(R. 297). Dr. McGovern said that the basis for this plan

was essentially what is being done in his own city (R. 227).

2 Excluding three elementary schools for which no data was available,

in 1964-65 the total capacity of the remaining 84 elementary schools was

54,973 pupils, while the enrollment was 43,752—leaving space available

for 11,221 pupils (R. 103). The 63 all white schools had room for 8,928

additional pupils, and the 6 schools with a majority of white pupils had

room for 1,137 additional pupils— or a total of 10,065 additional pupils.

Forty-five o f these 69 schools had room for 100-plus pupils (R. 104).

The elementary schools with all or a majority of non-white pupils had

room for 1,156 additional pupils (R. 104).

Excluding three secondary schools for which no data was available,

in 1964-65, the total capacity of the remaining 20 secondary schools was

31,936 pupils, while the enrollment was 29,774—leaving space available

for 2,162 additional pupils (R. 104). The 13 all white secondary schools

had room for 262 additional pupils, and the 4 secondary schools with a

majority of white pupils had room for 759 additional pupils— or a total

o f 1,021 additional pupils. Six of these 17 schools had room for 100-plus

additional pupils (R. 104). The secondary schools with all or a majority

of non-white pupils had room for 1,141 additional pupils (R. 105).

18

In Ms testimony, Dr. Carmack suggested an additional

effect of a “ majority to minority” transfer policy: “ If

there [were] no attendance boundaries in Oklahoma City

where one could go without anticipating the probabilities

of some Negroes in the adjacent schools, the efforts to

move one’s residence would be minimized.” This would

not only help in counteracting the already existing identifi

cation of most schools in the system as “ Negro” or “white”

schools, but help prevent the long range effects of the

board’s past policies from producing more racially desig

nated schools in the future (R. 298).

Dr. Carmack emphasized that at the same time the

proposed transfer policy was reasonable and fair in that

it takes into account not only the need to give substantive

relief to respondents, but also the concept of freedom of

choice. Thus those who do not wish to take advantage

of a different kind of educational environment do not have

to do so (R. 298). He clearly distinguished this proposal

from those which provide for compulsory transportation

across zones without regard to the desires of the students

involved—this is a completely voluntary plan (R. 298).

The Oklahoma City school system does not provide trans

portation for pupils, and would not be required to do so

under the proposed plan (R. 164, 336).

C. Zoning and Attendance Areas.

As indicated above, the expert panel determined that

the location of buildings and related zoning in the segre

gated system was designed to facilitate segregation (R.

270-271). Even after the abolition of an explicit set of

dual zones, the panel concluded that the board’s zoning

policies continued to serve to contain Negroes, and the

few whites who do not wish or cannot afford to move,

in present predominantly Negro attendance areas or in

19

new ones established under those policies (R. 109). These

effects were re-inforced by the board’s transfer policies,

which encouraged those in the racial minority in any

particular zone to transfer out and cause the zone to be

come even more clearly racially identified (R. 221). If

progress toward desegregation of schools is to be achieved,

the panel concluded, the racial composition of schools

must be considered in determining the boundaries of at

tendance areas (R. 109).

Dr. Spaulding, amplifying the report in his testi

mony, noted the confusion which has arisen around the

use of the term “neighborhood school.” He pointed out

that the term “neighborhood” as used in the study of

people is a sociological term which indicates a group of

people having certain kinds of relations with each other.

However, schools are not generally designed for this kind

of a neighborhood, but the boundaries are drawn in order

to get enough students inside the schools to fill them and

to operate them effectively, i.e., in terms of density of

population, size of buildings, etc. (R. 265). It is probably

not proper to attach to these zones the word “neighbor

hood” which has emotional connotations which suggest

that these people are already related to each other and

all know each other, etc. (R. 264-265).

The expert panel recognized that even if the facilities

planning and related zoning for the school system had

been designed for segregation, the panel must work within

the confines of the existing school facilities (R. 239-243).

After analysis of the entire system, the panel concluded

that although the all-Negro schools in the traditionally

Negro area of the city could not be re-zoned so as to

desegregate them, the same policies which had made these

schools “Negro” schools were in the process of making

some other schools “Negro” schools, and these other

20

school zones could be more easily changed (E. 117-120,

237-238).

The expert panel’s report therefore recommended that

two sets of adjacent school districts, each containing schools

with grades 7-12, be combined so that one school in each

combined district would house grades 7-9 and the other

would house grades 10-12. The combination of the Harding

and Northeast districts would produce a racial composi

tion of 91% white and 9% non-white, compared to a 100%

white enrollment in Harding and a 78% white enrollment

in Northeast; the combination of the Classen and the

Central districts would produce a racial composition of

85% white and 15% non-white, compared to a racial com

position of 100% white in Classen and a racial composi

tion of 69% white in Central (1964-65 enrollment figures)

(E. 118-120).3

The practical problems of merging these districts were

considered in detail. The traveling distance required

of pupils in these merged districts would be no further

than the board now requires of pupils living in the north

west section of the city who are assigned to Northwest

High School (E. 239). Merger should produce no sub

stantially different operating costs because of efficiency

gains (E. 240). Furthermore, combining these schools

would allow for a broader and richer curriculum, and

would bring these high schools more nearly in line with

the other high schools in the system. For example, at

Northwest, there is a 12th grade class of 800 pupils, one

at Grant of 600, one at Capitol Hill of 731, one at Marshall

of 468, and one at Douglass of 383. The proposed merged

schools presently have 12th grade classes of the following

8 The overall non-white pupil percentage in the school system was 16.9%

(K. 95).

21

sizes: (a) Central, 162, and Classen, 240; (b) Northeast,

212, and Harding, 288 (R. 243).

D. Faculty Assignments.

The expert panel noted in their report that “ since a

greater percentage of non-white personnel holds masters

degrees than of white personnel, and since testimony of

the superintendent of schools indicated no difference in

quality of performance between white and non-white per

sonnel, it is assumed that the range of individual com

petence among faculty has no relationship to race” (R.

93-94). They concluded, however, that integrated assign

ments of teaching personnel in elementary and secondary

schools have been made only when the pupils in those

schools were integrated, i.e. that if the pupil enrollment

is all-white, so is the faculty, and similarly, if the pupil

enrollment is all non-white, the faculty is all non-white

(R. 95). The report said that although the general policy

statement of the school board appeared to point toward

impartiality in respect to employment of faculty and other

personnel, nevertheless “ it is somewhat too cautious to

lead to further progress toward integrated faculties” (R.

110). It was noted that the school board’s general policy

statement is susceptible of the interpretation that Negro

teachers will be assigned to schools with all-white faculties

only when they are “ ready” to accept Negro teachers

(R. 110).

In order to avoid disrupting the existing faculty

of individual schools which would occur by withdrawing

most of the Negro faculty members from the Negro schools

and distributing them throughout the system, the panel

recommended that “a majority of the Negro teachers as

signed to all white or to integrated schools should be se

cured by employing new teachers” (R. 114). Based on the

22

frequency of vacancies in the system (R. 155, 276), the

panel proposed that “the Board should immediately take

action that it will without reducing either the number of

white or the number of non-white teachers now employed,

integrate the faculty so that, by 1970, the following con

ditions will prevail: The ratios of whites to non-whites in,

(a) the central administration of the schools, (b) non

teaching positions which are filled by certificated per

sonnel, and (c) faculty in each school will be the same

as the ratio of whites to non-whites in the whole number

of certificated personnel of the Oklahoma City Public

Schools. Maintaining these ratios does not imply any

policy in respect to the use of race as a criterion for initial

employment. To the contrary, it assumes that the super

intendent will recommend for employment, and that the

Board will employ, the best faculty available” (R. 114).

The target date for complete integration of faculty was

keyed to an annual turnover rate of approximately 15%,

so that complete re-assignments could be easily accom

plished within five years from the date of the report (1965)

(R. 155, 276).

Dr. Carmack amplified the basis for the panel’s recom

mendation of the ratio-result plan of faculty desegregation

in his oral testimony:

. . . if the members of the faculty who are now of a

minority group are as well qualified and there is some

evidence to suggest that they may be better qualified

than their counterparts in the total faculty, there must

be some artificial factor at work if we find them con

centrated closely together, and that it might not be

unreasonable to hope that if random selection were

employed, eventually random distribution should oc

cur.

23

We ought to find, if we have 15% or 20% or what

ever it might be of this group, and they are just as

well qualified and can function as effectively as the

others, we ought to find them appearing all over the

system in about their ratio on the general faculty

(R. 302).

Dr. Spaulding commented on the situation in the central

administration:

These tables will show also that the Negro teachers

are paid on the average more than the white teachers

are paid. Yet if one examines the way in which people

have been placed in the central administration of the

schools, one finds that only 9% of those employed in

the central administration are Negroes in 1964-65;

and I have some difficulty understanding how it is that

if the policy is in truth being followed that the teach

ers with the longest experience, with the highest level

of training on the average and who are paid best on

the average, don’t provide a higher proportion of the

educational leadership of the city in the central ad

ministration (R. 268).

Dr. Spaulding also pointed out an important reason for

the inclusion of specific standards in an adequate plan of

faculty desegregation:

. . . when schools are desegregated there is a tendency

to dismiss Negro teachers or to reduce the number of

Negro teachers employed and to fill these places with

white teachers . . .

One of the things that we were concerned about

then is that any program of integration of faculty have

safeguards which would prevent the occurrence in

Oklahoma City of what has occurred elsewhere—this

24

has taken place in southern states—and so we were

endeavoring to set up some kind of safeguard here

when we suggest that the current percentage in num

ber of white and Negro teachers be maintained (R.

290).

E. In-Service Education of Faculty.

The panel recommended in their report:

. . . Since more will be involved than the acquisition of

information, and since basic attitudes may, in some

cases, need modification, a carefully prepared in-ser

vice educational program should be part of this plan.

It will not be enough to distribute policy statements

in writing. The components of the personnel training

effort might include:

(1) City-wide workshops may be held devoted to

school integration and conducted in September be

fore school opens. This has been done by some

cities in Oklahoma and should be done in Oklahoma

City. These workshops should provide for complete

and full explanation of policy with reference to such

matters as teacher assignment, pupil transfer and

other administrative details of the desegregation

program. . . . Effort should be made to allow the

the participants time to discuss together, perhaps

in small groups, their own concerns and reserva

tions. They should gain the impression that the

administration is committed to the successful execu

tion of a program of real integration together with

maximum educational opportunity of all children,

whatever their economic or racial background. . . .

(2) In addition to the workshops which will deal

specifically with the Oklahoma City Situation, spe-

25

cial seminars should be held for administrators and

teams of teachers from each school in the processes

and skills involved in educational leadership in a

changing situation. The effort of these special, in

tensive seminars would be to establish in each school

a few leaders who can act both as a special com

mittee of advisors to the administration and as

trainers of the other faculty members. . . . They

should study the psychology of attitude formation

and change (stereotyping and prejudice). They

should develop some sensitivity to culture and cul

tural difference, with special attention to such groups

within the general culture as Negroes, Indians, and

Mexican-Americans. They should know something

about the broad area of inter-group relations. This

is only a partial and suggestive list of topics which

could provide content for training seminars for ad

ministrators and selected faculty members.

(3) Spaced throughout the term, special clinics

of one day, or even a half day, should be conducted

by school grade level or by building for all teaching

and administrative personnel. These could focus on

day by day problems within the schools themselves,

within the community or within patron groups. They

could be planned by teams of teachers and admin

istrators who had developed special interest in the

human relations field from participating in the

seminars described above. Outside consultants could

be brought in from time to time.

This in-service training program would not only

communicate to the personnel of the school and the

community the seriousness with which.the administra

tion was approaching school integration, but it would

also offer concrete help to those most directly con-

26

cerned, and through them, to the parents and PTA

groups of the schools (E. 120-122).

Dr. Carmack amplified the basis for this recommendation

in his oral testimony (E. 293-296). The panel indicated

the underlying premise for this program when they said

at the beginning of their report:

The great weight of experience in school desegre

gation situations throughout the country indicates that

social change meets less resistance when those in

authority act without equivocation and hesitation. . . .

Accordingly, the authors of this report believe that

the Board of Education and the Superintendent of

Schools in Oklahoma City should hold and communi

cate an affirmative view of the program of change

herein outlined. By affirmative action, we mean the

desire and intent to comply fully with both the spirit

and the letter of constitutional provisions without

an effort to minimize changes that might be desirable

(E. 92).

IV. The District Court’s Order Requiring an Adequate

Plan of Desegregation, and Specifying Certain Mini

mum Components of Such a Plan Based Upon Recom

mendations of the Expert Panel.

After the submission of the expert panel’s report on the

deficiencies of the school board’s approach to desegrega

tion, and their minimum proposals for an adequate plan,

the district court held another hearing in the summer of

1965. The court stated that “ the crux of the problem be

fore the Court” was whether or not the school board’s

“Policy Statement” of January 14, 1964, which had been

analyzed by the expert panel, was sufficient to comply

with the court’s previous decision of July 11, 1963 re

27

quiring the adoption of an effective plan of desegregation

(R. 147). The court said that following the first hearing

on the “Policy Statement,” it was without sufficient evi

dence to approve or disapprove it, and for that reason

requested the employment of educational administration

“ experts who were competent, qualified, unbiased, un

prejudiced, and independent of any local sentiment, to

make a survey of the problem” for the benefit of the

court as well as the school system (R. 147).

In its opinion of September 7, 1965, the district court,

in assessing the expert panel’s report, said:

The Report . . . concludes that the absence of an af

firmative program and the maintenance of transfer

policies which enable white pupils to transfer from

predominantly Negro schools to predominantly white

schools has greatly hindered the disestablishment of

segregation in the public school system. The Report

notes that teacher desegregation has taken place on

only a token basis, makes several recommendations

aimed at both correcting existing policies which hinder

desegregation and permitting at least a meaningful

beginning toward the desegregation of the school sys

tem required by the mandate of the Brown decisions.

After careful study and evaluation of the Report

admitted in evidence, hearing the testimony of the

experts who prepared it, observing their demeanor,

and noting their responses to questions posed by coun

sel for defendants, this Court concludes the Report

was prepared by highly qualified individuals in an

atmosphere of objective impartiality; that the sta

tistics and data upon which the recommendations are

based are substantially accurate, and that the recom

mended remedies for the continuing segregation of

28

the defendant school system are reasonable, workable,

and educationally sound (R. 148-149).

The court concluded:

The burden of going forward with desegregation

was placed on the school boards, but the responsibility

for reviewing the adequacy of desegregation and good

faith compliance at the earliest practicable date, was

placed on the Federal Courts, which were admonished

to consider “ * * * the adequacy of any plans the

defendants may propose to meet these problems and

to effectuate a transition to a racially nondiscrim-

inatory school system.” The defendant Board, to com

ply with the Brown decisions, must thus have a plan

which sets forth the steps to be taken to effectuate

the transition to a school system not based on race,

but based on good will.

Paper compliance and policy statements are insuf

ficient to satisfy the standards of desegregation re

quired by the second Brown decision (R. 156).

* * #

The Board maintains that it has no affirmative duty

to adopt policies that would increase the percentage

of pupils who are obtaining a desegregated education.

But a school system does not remain static, and the

failure to adopt an affirmative policy is itself a policy,

adherence to which, at least in this case, has slowed

up—in some cases— reversed the desegregation process

(R. 151-152).

# # #

This Court concludes that the Board has failed to

desegregate the public schools in a manner so as to

eliminate either the tangible elements of the segre

gated system, or the violation of the constitutional

29

rights of the plaintiffs and the members of their class,

enumerated in the Brown decision.

The essential or most important point is that defen

dants have never prepared a plan by which progress

in the desegregation process could be accurately judged

either by themselves or by others. The plan submitted

to this Court in January, 1964 is not a plan, but a

statement of policy. School desegregation is a difficult

and complicated matter, and, as the record shows,

cannot be accomplished by a statement of policy (R.

152-153).

Since the school board had repeatedly refused to under

take any affirmative program to disestablish segregation,

and since the expert panel’s proposals for minimum com

ponents of an adequate plan of desegregation were so

thoroughly supported by their qualifications and testimony,

the court ordered the school board to adopt these proposals

in order to provide the equitable relief required by the

Brown decision, guaranteeing the Constitutional right to a

desegregated education (R. 162-165). The court said:

The recommendations contained in the Integration

Report will permit a meaningful start to the eradica

tion of the inequalities, based on race, still existing

in the defendant school system (R. 154).

The Court also stated:

The Court does not by this Order intend to say that

the performance of the provisions of this Order will

satisfy and meet the full good-faith requirements of

desegregation as provided by law. Further study and

action of the Board of Education should be under

taken in order for the Oklahoma City Public Schools

to be further and completely desegregated as the law

requires (R. 164).

30

V. The Opinion of the Court of Appeals.

The Board of Education appealed the order of Sep

tember 7, 1965, to the Court of Appeals for the Tenth

Circuit. In a 2-1 decision on January 23, 1967, the Court of

Appeals upheld all elements of the district court’s decree,

with the exception of the requirement for in-service edu

cation of faculty. (The opinions of the majority and of

the dissenting judge are printed in Appendix A of the

Petition).

In a review of the evidence, the Court said: “ The record

reflects very little actual desegregation of the school sys

tem between 1955 and the filing of this case. During that

six year period segregation of pupils in the system had

only been reduced from total segregation in 1955 to 88.3

percent in 1961.” The Court noted that even at the time

of the filing of the expert panel’s report in January 1965,

about 80% of the Negro students still attended clearly

segregated schools (schools which are more than 95%

non-white).

The Court pointed out that inherent in the school board’s

argument was the claim that there was no racial dis

crimination in the operation of the school system. In

response to this contention, it said:

The attendance line boundaries, as pointed out by

the trial judge, had the effect in some instances of

locking the Negro pupils into totally segregated

schools. In other attendance districts which were not

totally segregated the operation of the transfer plan

naturally led to a higher percentage of segregation

in those schools.

In upholding the power of a United States district court

to order an impartial expert survey on planning for

31

desegregation in the circumstances of this case, the Court

held:

We agree that in considering or reviewing acts of

school boards and officials, generally, the power of

a court of equity does not extend to the promulgation

of rules or regulations to be adopted and followed

by such boards and officials, This does not mean that

when a court of equity reaches the conclusion that

unconstitutional racial discrimination in a school sys

tem exists, the power of the court ends. When the

trial court here made such a finding and pointed out

the areas of discrimination, it vras the clear duty

of the school authorities to promptly pursue such

measures as would correct the unconstitutional prac

tices. . . .

The trial court was clearly within its equitable

powers in ordering the board to present an adequate

plan for desegregation of the school system. The

board presented no plan, it only reiterated its general

intention to correct some of the existing unlawful

practices. This was not compliance with the order

of the court. It was the existence of this factual situa

tion, due entirely to the failure and refusal of the

board to act, which created the necessity for a survey

of the school system by a panel of experts. Even at

this point, the trial court patiently refrained from

compelling such a survey but asked the board to

cause a survey of the school system to be made. It

was only after the board’s refusal of this request

that the court appointed the three experts and di

rected them to make a survey.

The Court then held that the inclusion of the specific

proposals of the expert panel for minimum elements of

an adequate plan of desegregation in the decree of the

district court was proper (with the exception noted above):

We need not recite again the facts in this record

which conclusively show that for ten years after

the board enunciated its intention to abide the man

date of Brown [the board has] taken only such action

as they have been compelled to take and desegrega

tion has been only of a token nature. Under the factual

situation here we have no hesitancy in sustaining the

trial court’s authority to compel the board to take

specific action in compliance with the decree of the

court so long as such compelled action can be said to

be necessary for the elimination of the unconstitu

tional evils pointed out in the court’s decree. The

procedures ordered by the trial court must be viewed

in light of this test.

The Court of Appeals concluded:

Because of the refusal of the board to take prompt

substantial and affirmative action after the entering

of the court’s decree, without further action by the

court the aggrieved plaintiffs, even with a favorable

decree from the court, were helpless in their efforts

to protect their court-pronounced Constitutional rights.

Under these circumstances it was the duty of the

trial court to take appropriate action to the end that

its equitable decree be made effective. Again, we go

back to the second Brown case where the trial courts

were directed “to take such proceedings and enter

such orders and decrees consistent with this opinion

as are necessary and proper to admit to public schools

on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate

speed the parties to these cases.”

33

ARGUMENT

I.

The Decisions Below Are Clearly Correct.

A. There Was Overwhelming Evidence of the Existence

and Continuation of Segregation in the Oklahoma

City School System.

Without dispute the State of Oklahoma maintained ab

solute segregation in public education for nearly fifty

years. As indicated by the statutory structure concerning

segregation in public education (see Statement, supra)

this meant that all planning concerning schools, all deci

sions on the location of buildings, all pupil attendance

policies, all faculty assignments, etc.,—i.e. every facet of

the school system—had to be designed and executed to

achieve and maintain “ complete” separation between the

races. Thus the entire pattern of operation of the school

system was directed toward segregation as an explicit

and overriding goal. Many policy decisions made during

the period of required segregation necessarily have long

continuing effects.

In this context of fifty years’ history of using all of

the state’s resources to segregate the school system, the

school board ostensibly undertook to achieve the desegrega

tion required by the Fourteenth Amendment by simply

redrawing certain zone lines. It cannot seriously be con

tended that such minimal steps could undo the effects

of fifty years of concentrated state effort to build a segre

gated school system. Because of the obvious inadequacy

of such a token step to effectively desegregate the schools,

and because of the deep roots of the practice of segrega

tion in the public school System, it is not surprising that

34

the record shows that school board policies following

1955 generally had the effect of maintaining segregation.

Thus, as the district court found, the board zoned the

previously all-Negro schools in such a way that they re

mained identified as Negro schools, encouraging many

whites who lived in the area to move out. Furthermore,

all-Negro Douglass High School was continually enlarged

by temporary facilities so that nearly all Negro high

school students in the city could continue to be accommo

dated in the “ Negro” high school.

The “minority to majority” transfer policy was, of

course, fundamental to continuing school segregation,

where zoning was inadequate by itself. Whites assigned

to formerly and still predominantly Negro schools who

could not change their residences were able to transfer

out; Negroes assigned to formerly all-white schools were

encouraged to re-segregate themselves. The net effect

was that virtually all schools in the city became clearly

racially designated or identified. The existence of this

policy until it was struck down by this Court in 19634

belies the board’s asserted dedication to the “neighborhood

school.”

The segregationist design of the board’s attendance

policies is even more graphically shown by the fact that

18 of the 19 new schools opened from 1959-60 through

1964-65 were either all Negro or all white.

Faculty members were assigned to schools only with

members of their own race before 1955, and after 1955

generally continued to be assigned only to schools where

their race predominated, although some whites could teach

in predominantly Negro schools. There is conclusive evi

4 Goss v. B oard o f Education o f K n oxville, 373 U.S. 683 (1963).

dence of perpetuation of racial segregation in faculty-

assignments.

There was, therefore, overwhelming evidence to support

the district court’s conclusion that the Oklahoma City

public schools have not been desegregated. Since the

school board repeatedly refused to undertake any affirma

tive program of desegregation, the district court, as a

court of equity obligated to provide adequate relief for

this existing constitutional violation, sought the assistance

of independent experts in educational administration to

devise minimum components of an adequate plan of de

segregation.

B. The Expert Testimony Provided a Reasonable

Basis for the District Court’s Order.

The expert panel made a detailed study of the Oklahoma

City school system. As detailed supra in the Statement

the three experts were all prominent in the field of educa

tion and obviously competent to undertake this task. All

of the sections of the district court’s order requiring

specific components of an adequate plan of desegregation

are based on the report and recommendations of the

expert panel.

The general conclusion of the panel was that effective

desegregation of a segregated school system requires sub

stantial affirmative action which must be planned in detail

to achieve the goal. The four components of effective

planning which the expert panel outlined were adopted

by the district court.

Having found that the school system remained primarily

segregated and that the board’s policies generally have

the effect of perpetuating that segregation, the expert

panel then developed and recommended specific policies

to implement desegregation.

36

The effectiveness of the past policy of “minority to

majority” transfers in maintaining segregation by causing

schools to become or remain racially designated, indicated

that a converse “majority to minority” policy might'

be effective in producing desegregation. This was con

firmed by an extensive analysis of the pupil composition

of each school in the system, which showed that there

was substantial excess capacity, particularly in the ele

mentary schools. That the school system was able to

process several thousand transfers annually under the

old “minority to majority” policy showed that this pro

posal would not impose an undue administrative burden.

The expert panel also recommended that not only would

the “majority to minority” proposal counteract the former

transfer policy and the present transfer policies which

continue to perpetuate the effects of the former policy,

but w^oild also counteract the effects of the board’s zoning

policies which have fostered segregation through follow

ing racial residential patterns and thereby encouraging

increased residential segregation.

After an analysis of all of the school zones in the city,

the panel concluded that while some traditionally all-

Negro schools could now not be re-zoned so as to desegre

gate them because residential segregation had hardened,

other schools which were in the process of becoming Negro

schools under the same policies could be re-zoned to pre

vent this. They therefore recommended the consolidation

of certain school zones. That this was practical as well

as appropriate relief was shown by the experts’ analyses

of such factors as amount of travel required by pupils in

the merged districts, operating costs of the merged schools,

effects on curriculum, and comparison of size of the merged)

schools with other high schools in the system.

37

The expert panel very carefully considered all aspects

of the problem of a remedy for faculty segregation, in

cluding qualifications of Negro and white teachers, neces

sity for continuity of faculty in individual schools, and

annual faculty turnover rate. In accordance with general

requirements for effective planning, they considered there

must be some defined goal and program if faculty desegre

gation were eventually to be achieved. They proposed

that based on the annual faculty turnover rate, that five

years after the start of the plan, the ratio of whites to

non-whites assigned to each school and in the central

administration should be the same as the ratio of whites

to non-whites in the whole number of certificated per

sonnel in the school system. This would provide a clear

standard for measuring the progress of the school system

toward desegregation of faculty. It would also protect

against the tendency which has developed elsewhere for

desegregation of faculty to result in Negro teachers being

squeezed out of the system.

II.

There Is No Conflict of Decision.

A. The Decision of the Court of Appeals Is Clearly in

Accord With Recent Major Decisions of the Other

Circuits on the Implementation of Desegregation

Relief in School Systems Where There Has Been

Legal Segregation.

The recent landmark school desegregation decision of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit,

United States et al. v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion et al., 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir., 1966), re-affirmed en

banc, Civil No. 23345, March 29, 1967, clearly agrees with

the decision of the Tenth Circuit in this case in all re

spects, including the scope of the relief required, the

38

powers and duties of federal courts of equity in fashion

ing relief, and the specific components of the relief or

dered by the district court in this case.

The Fifth Circuit clearly holds at several points that

the duty of school boards which had operated dual segre

gated school systems is to affirmatively re-organize those

systems into unitary integrated school systems. The con

stitutional issue in a class action suit by Negro plaintiffs

against a school system concerns not the admission of

the individual plaintiffs to formerly all-white schools, but

the segregated operation of the system. The Court states

that the distinction originating in Briggs v. Elliott, 132

F.Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C. 1955) between “desegregation”

and “ integration” is not a meaningful one and has no

basis in Supreme Court jurisprudence.5 The Fifth Cir

cuit’s opinion extensively analyzes the case of Bell v.

School City of Gary, Ind., 324 F.2d 209 (7th Cir., 1963),

cert, denied 379 II.S. 924, a leading Northern “ de facto”

segregation case denying relief, and finds it to be com

pletely inapplicable to school systems where the segre

gated pattern of operation originally arose from state

action.6 Since school systems which had been legally

segregated have an affirmative obligation to disestablish

segregation, the Fifth Circuit holds that “ the only school

6 It is to be noted that the school board in their petition cites K elley

v. B oard o f Education o f Nashville, 270 F.2d 209 (6th Cir., 1959), cert,

denied 361 U.S. 924, for its approval of the B riggs principle. This

opinion, which upheld the “ minority to majority” transfer policy, was

completely undercut later when this Court invalidated that same policy in

Goss v. B oard o f E ducation o f K n oxville, 373 U.S. 683 (1963).

6 D ow ns v. Board o f E ducation o f Kansas C ity, 336 F.2d 988 (10th

Cir., 1964), cert, denied 380 U.S. 914, which follows G ary, also cited by

the school board along with Gary in their petition, is similarly found to

be inapplicable to the duty of a school board which had operated a legally

segregated school system to disestablish that system, since the trial court

found that the system had already been adequately and effectively deseg

regated. The Tenth Circuit itself so held in the opinion below in this case.

39

desegregation plan that meets constitutional standards is

one that works” (emphasis in original). 372 F.2d at 847.

The Court holds in Jefferson County that the extensive

equity power which it exercises in its decree exists in

dependently of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and is inherent

in federal courts. Under the Court’s decision the dis

trict courts are required to evaluate compliance with the

constitutional requirement of desegregation by measuring

actual performance—not promised performance— and may

and should call upon expert assistance to aid in doing so.7

The Fifth Circuit devoted extensive consideration in

Jefferson County to the United States Office of Educa

tion’s Revised Statement of Policies for School Desegre

gation Plans (March 1966) implementing Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964— the “H.E.W. Guidelines.” It

held that they were minimum standards for the adequacy

of school desegregation plans approved by federal courts,

since they generally codified past Supreme Court and

Courts of Appeals decisions, and were prepared by per

sons of high expert qualification in the field of educational

administration. Each of the requirements of the district

court’s order in this case has a parallel in the Guidelines.8

The Court also specifically cites the district court’s opin

7 Such expert assistance may properly be given not only by the Depart

ment of Health, Education, and Welfare, but any responsible government

agency or competent independent group. In appraising the adequacy of

the performance of the constitutional duty to desegregate a school system,

the Court holds that it is proper to use numerical percentages of the num

ber of Negro students in desegregated schools as a yardstick and objective