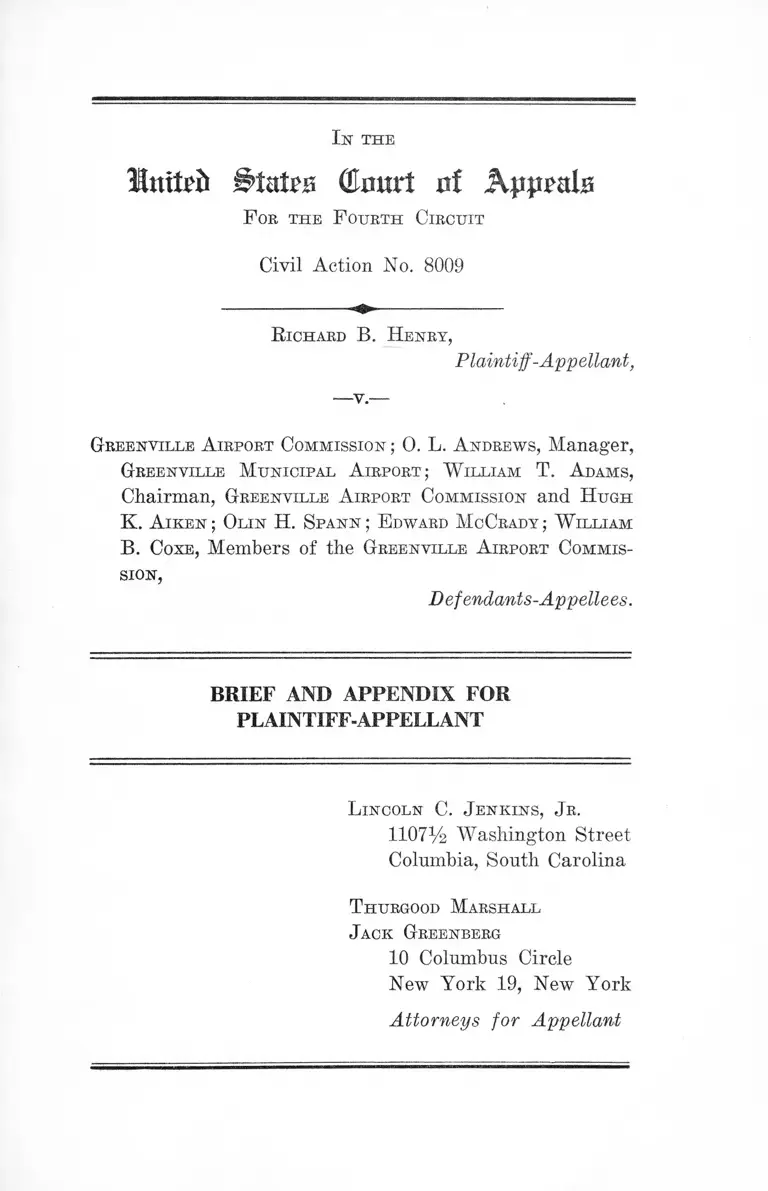

Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission Brief and Appendix for Plaintiff-Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission Brief and Appendix for Plaintiff-Appellant, 1959. 834dd211-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5ee606e8-86ce-4f03-b412-f224258e478f/henry-v-greenville-airport-commission-brief-and-appendix-for-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Mnxteb (Eiuirt nf Kppm h

F ob the F oubth Circuit

Civil Action No. 8009

R ichard B. H enry,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

—v.—

Greenville A irport Commission ; 0. L. A ndrews, Manager,

Greenville Municipal A irport; W illiam T. Adams,

Chairman, Greenville A irport Commission and H ugh

K. A iken ; Olin H. Spann ; E dward McCrady ; W illiam

B. Coxe, Members of the Greenville A irport Commis

sion,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR

PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

L incoln C. J enkins, J r.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

T hurgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellant

INDEX TO BRIEF

Statement of the Case....... ....................................... 1

Questions Involved ........ .......... .................... ........... 5

Statement of the Facts .......... ................... ...... ......... 6

\ Argument 1................................................................... 8

PAGE

I. The court below erred in holding that Four

teenth Amendment rights had not been de

nied, thereby dismissing the complaint, and in

holding that there was no jurisdiction under

Title 28 U. S. C. §1343 and Title 42 U. S. C.

§1983 .......................... ........... ........................ 8

II. The court below erred in dismissing the com

plaint which alleged that appellant, an inter

state passenger in the course of his interstate

journey, was racially segregated in his use

of the facilities at the Greenville Municipal

Airport contrary to Article I, Section 8 of

the United States Constitution (Commerce

Clause) ................... .................. ................... 17

III. The court below erred in dismissing the com

plaint insofar as it alleged that on informa

tion and belief the Greenville Airport Com

mission has from time to time received sub

stantial sums of money from the government

of the United States for the purposes of con

structing substantial portions of and main

taining operations at said Airport whereby

the discrimination against appellant violated

the due process clause of the Fifth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States 19

11

IY. The court below, contrary to Rule 23(a)(3)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

erred in striking paragraph 2 of the com

plaint which alleges that this is a class action 21

V. The court below erred in denying appellant’s

application for preliminary injunction which

was based upon an uncontroverted affidavit

supporting the allegations of the complaint.... 24

VI. The court below erred in not permitting ap

pellant to introduce evidence on the motion

for preliminary injunction .......................... 26

Table oe Cases

Air Terminal Servs. Inc. v. Rentzel, 81 F. Supp. 611

(E. D. Va. 1949) ..................................................... 10

Alston v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 112

F. 2d 992 (4th Cir. 1940), cert, denied 311 U. S. 693 18

Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780 (5th Cir. 1958) .... 16

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 .................... ........10,19, 20

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956),

aff’d, 352 U. S. 903 ......................... ........................ 9,10

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) .. 9

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (4th Cir. 1951),

cert, denied, 341 U. S. 941 ..... ............................... 17

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, Ohio,

228 F. 2d 853, 857 (6th Cir. 1956), cert, denied,

350 U. S. 1006 ................................. ....................... 24

Conley v. Gibson, 355 U. S. 41, 4 7 ............................ 13

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 19 ............................... 10

PAGE

Ill

Dawson v. Mayor, 220 F. 2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955),

aff’d 350 IT. S. 877 .............. ........... ........................ 9

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202 ......... ......... -............. 11

Flemming v. South Carolina Elect. & Gas Co., 224

F. 2d 752 (4th Cir. 1955), app. dism., 351 IT. S. 901 10

Frasier v. Board of Trustees of the ITniv. of N. C.,

134 F. Supp. 589, 592 (M. D. N. C. 1955), aff’d,

350 U. S. 979 (1956) ........... ................................ . 9, 22

Frost Trucking Co. v. E. E. Commission, 271 U. S.

583 ................................. ..............- ......... .............. 18

Gossnell v. Spang, 84 F. 2d 889 (3rd Cir. 1936), cert,

denied, 299 U. S. 605 ________________ ____ 25

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U. S. 496 ................................... 15

Hawkins v. Board of Control of Florida, 253 F. 2d

752 (5th Cir. 1958) __ ___________ _____ _____ 26-27

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816, 825 ___ 18

Heyward v. Public Housing Administration, 238 F.

2d 689 (5th Cir. 1956) .... ..................................... 20

Holmes v. Atlanta, 124 F. Supp. 290 (N. D. Ga. 1954) 16

Jinks, et al. v. Hodge, 11 F. E. D. 346 (E. D. Tenn.

1951) ___ ____________________ _______ ___ 22

Johnson v. Board of Trustees of ITniv. of Ky., 83 F.

Supp. 707 (E. D. Ky. 1949) ____ __________ ____ 15

Lonesome v. Maxwell, 220 F. 2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955) .. 9,11

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 ................... ......... 17

Nash v. Air Terminal Servs., 85 F. Supp. 545 (E. D.

Va. 1949) ............. .................... ........... ................. 10,20

PAGE

IV

N. Y. N. H. & H. R. Co. v. Nothnagle, 346 U. S. 128 .... 18

Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 U. S. 218, 229 19

Royal Brewing Co. v. Missouri K. & T. Ry. Co., 217

F. 146 (D. Kan. 1914) ............... ........... ................ 25

Sprout v. South Bend, 277 U. S. 163, 168 ................. 19

Union Tool Co. v. Wilson, 259 U. S. 107,112.............. 24

United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 332 U. S. 218, 228 19

Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, 177 F. 2d 949 (6th

Cir. 1949) ................................................................ 17

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d

845 (4th Cir. 1959) .................................... ............. 10

Wrighten v. Board of Trustees of Univ. of S. C., 72

F. Supp. 948 (E. D. S. C. 1947) ............................ 15

STATUTES

South Carolina Statutes

Act. No. 919 of the Acts and Joint Resolutions of

the General Assembly of the State of South Caro

lina ........................................................................... 1,6

United States Constitution

Article 1, Section 8 ..................................................... 5, 8,17

Fifth Amendment ........ .......... ............. .................... 10,19

Fourteenth Amendment ............................................ 2,19

PAGE

V

U nited States Code

PAGE

Title 28 §1331 ....... ........................-................... . ..2, 4,14,15

Title 28 §1332 ...... ..... ........... ......... .......... ......... .... ..2, 5,14

Title 28 §1343 ........ .......... ......... ......... .......... ..5, 8,14,15

Title 42 §1981 .... ........................ ........................ 2

Title 42 §1983 .............. .......... .................... ....... ...... 8,9

F ederal R ules oe Civil P rocedure

Rule 6 ............................... .... ........... ......... ........ ...... 2

Rule 12(b) _____ ________________ ________ ___ 2

Rule 23(a)(3) ............. ....................................... .... 2, 21, 22

Rule 65 ................... .................................. .......... ...... 26

Other A uthority

2 Race Relations Law Reporter 269 (1957) .... . 15

VI

INDEX TO APPENDIX

PAGE

Complaint................ la

Exhibit “A”—Acts and Joint Resolutions of the

General Assembly ........................................... 5a

Motion for Preliminary Injunction ........ .................. 8a

Affidavit, of Richard B. H enry................................... 9a

Motion to Strike ....................................................... 11a

Motion to Dismiss ....... .............................................. 13a

Renewal of Motion for Preliminary Injunction...... 14a

Affidavit of Richard B. Henry ................................. 15a

Affidavit of Freda A. McPherson ............................ 18a

Order Dated September 8, 1959 .................................. 20a

Excerpts from Transcript of Proceedings, July 20,

1959 .......................................... 21a

Opinion of Hon. George Bell Timmerman, U. S. D. J. 26a

I n t h e

Inttpft BMta ©mart at Kppmh

F oe the F ourth Circuit

Civil Action No. 8009

R ichard B. H enry,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

—v.—

Greenville A irport Commission ; 0. L. A ndrews, Manager,

Greenville Municipal A irport; W illiam T. Adams,

Chairman, Greenville A irport Commission and H ugh

K. A ik e n ; Olin H. Spa n n ; E dward McCrady; W illiam

B. Coxb, Members of the Greenville A irport Commis

sion,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

This action was filed in Greenville, South Carolina, in

the United States District Court for the Western District

of South Carolina, Greenville Division, on January 20,

1959, against the Airport Commission for the City and

County of Greenville, an entity created by Act No. 919 of

the Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly

of the State of South Carolina, passed at the regular ses

sion of 1928 (see Exhibit to Complaint). Two of the indi

vidual appellee members of said Commission are, by said

statute, selected by the City Council of the City of Green

ville ; two are selected by the Greenville County Delegation

in the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina;

another member is selected by a majority vote of said four

2

members. The remaining appellee, 0. L. Andrews, is

manager of the Greenville Municipal Airport.

The appellant is a civilian employee of the United States

Air Force, and a resident of Michigan, who in the course

of his employment was required to use the facilities of the

Greenville Municipal Airport (Complaint, f[6; Appendix*

pp. 2a-3a) and reasonably expects that such duties will con

tinue to take him to said airport (Complaint, 1(3).

Appellant prayed for an interlocutory and permanent in

junction restraining appellees from making any distinc

tion based upon color in regard to service at the Greenville

Municipal Airport. Along with the Complaint was filed a

Motion for Preliminary Injunction and Notice of Motion.

In support of the Motion for Preliminary Injunction an

affidavit was filed relating racial discrimination practiced

against him at the airport upon which the suit and motion

were founded.

On February 7, 1959, appellees filed a Motion to Dis

miss the complaint under the provisions of Rule 12(b)(1)

and (6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure on the

grounds (1) that the court had no jurisdiction of the sub

ject matter of the action and, (2) that the complaint failed

to state a claim upon which relief could be granted. Ap

pellees also filed a Motion to Strike as immaterial, under

the provisions of Rule 12(f) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, the following portions of the Complaint:

“1. (a) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under Title 28, United States Code, Section 1331 as

this action arises under Article 1, Section 8, and the

Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States, Section 1; and Title 42, United States

Code, Section 1981 and the matter in controversy ex-

* Appendix refers to the appendix to plaintiffs’ brief printed herein.

3

“1. (c) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under Title 28, United States Code, Section 1332, plain

tiff being a citizen of the State of Michigan and defen

dants being citizens of the State of South Carolina

and the matter in controversy exceeding the sum or

value of Ten Thousand ($10,000.00) Dollars exclusive

of interest and costs.

“2. Plaintiff brings this action pursuant to Rule 23

(a) (3) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for

himself and on behalf of all other Negroes similarly

situated, whose numbers make it impracticable to bring

them all before the court; they seek common relief

based upon common questions of law and fact.

“5. Plaintiff alleges on information and belief that

said Greenville Airport Commission has from time to

time received substantial sums of money from the gov

ernment of the United States for the purposes of

constructing substantial portions of and maintaining

operations at the Greenville Municipal Airport.”

Thereupon, the cause was transferred to and ultimately

heard in Columbia although still in the Greenville Division

of the Western District.

Appellees filed no counter affidavit or other refutation of

appellant’s factual allegations.

At the hearing on July 20 appellant filed a motion en

titled Renewal of Motion for Preliminary Injunction which,

with slight variation, restated the averments of the original

application for preliminary injunction (App. p. 14a). In

support of the renewed motion there were filed appellant’s

affidavit (App. p. 15a) which paralleled the earlier affi

ceeds, exclusive of in te res t and costs, the sum or value

of Ten T housand ($10,000.00) D ollars.

4

davit except for reference to the fact that on the day prior

to hearing appellees were continuing to maintain the

segregation in question and an affidavit of one Freda Mc

Pherson, a resident of Greenville, relating her knowledge

that the practices complained of were maintained by ap

pellees (App. p. 18a). Appellees objected to the re

newed motion and the affidavits in support thereof on the

ground that “ [t]he motion for preliminary injunction men

tions nothing about any further affidavits to be filed”

(Transcript of Proceedings,* p. 3; App. p. 21a). Upon

this assertion the court declined to hear the motion for

preliminary injunction at that time and proceeded to hear

appellees’ motion to strike and dismiss (Tr. p. 5; App.

p. 22a). Thereupon appellant offered also to place on

the stand as witnesses the affiants who were then in court

to testify and subject themselves to cross-examination (Tr.

p. 6). To this the court stated “I realize that I may do that.

I also realize that it could aid one side or the other to get

an advantage that they are not entitled to. I don’t intend

being a party to that” (Tr. p. 6; App. p. 23a). Follow

ing this ruling plaintiff stated that “we will submit to

having it [the motion for preliminary injunction] heard

on that single affidavit at this time” (Tr. p. 8; App. p. 24a).

Appellant argued the motion for preliminary injunction.

Appellees argued their motions to strike and to dismiss.

At the end of the hearing the court stated that “the court

will refuse the motion for a preliminary injunction” (Tr.

p. 39; App. p. 25a). Thereafter, on September 11, the

court entered an order denying the motion for preliminary

injunction (as it had held in open court) and granting ap

pellees’ motions to strike paragraphs 1(a), 1(c), 2 and 5

of the complaint and to dismiss the complaint,

In granting the motions to strike the court below ruled

that there was neither federal question (28 U. S. C. §1331)

Hereinafter referred to as Tr.

5

nor diversity (28 U. S. C. §1332) jurisdiction. The opinion

of the court (App. p. 35a) holds that neither was there

jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. §1343.

On September 25 appellant filed notice of appeal.

Questions Involved

1. (a) Whether the court below erred in granting ap

pellees’ motion to dismiss where the complaint alleged that,

contrary to the equal protection and due process clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment to United States Constitu

tion, appellant had been racially segregated by appellees,

governmental officers, in his use of the waiting room facili

ties of the Greenville Municipal Airport; and

(b) which alleged that appellant, an interstate passenger

in the course of his interstate journey, was racially segre

gated by appellees, governmental officers, in his use of

the facilities of the Greenville Municipal Airport, contrary

to the commerce clause, Article 1, Section 8 of the United

States Constitution; and

(c) which alleged that, on information and belief, the

appellee Greenville Airport Commission has from time

to time received substantial sums of money from the gov

ernment of the United States for the purpose of construct

ing substantial portions of and maintaining operations at

the Greenville Airport, whereby the racial segregation of

appellant constituted also a denial of due process of law

guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

2. Whether the court below erred in holding that it had

no jurisdiction of the cause.

3. Whether the court below erred in granting appellees’

motions to strike paragraphs 2 (alleging that this is a

class action), and 5 (that there have been substantial fed

6

eral contributions for construction and maintenance of the

airport), of the complaint as immaterial.

4. Whether the court below erred in denying appellant’s

motion for preliminary injunction supported by appellant’s

affidavit—in opposition to which no factual issue had been

raised.

5. Whether the court below erred in refusing to permit

appellant to present testimony at the hearing on motion

for preliminary injunction on the ground that the motion

did not state that testimony would be presented.

Statement of the Facts

This ease was dismissed on motion to dismiss and con

sequently the averments of the complaint have been ac

cepted as true for purposes of the motion and this appeal.

The appellees in this case are the Airport Commission

for the City and County of Greenville which has been

created by Act No. 919 of the Acts and Joint Resolutions

of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina,

passed at its regular session of 1928. This Commission

consists of five members selected as follows: Two by the

City Council of the City of Greenville; two by the Green

ville County Delegation in the General Assembly and one

selected by a majority vote of the four selected as above

described (Exhibit to complaint; App. p. 5a). At Green

ville, South Carolina this Commission performs the widely

recognized governmental function of maintaining an air

port for the service of interstate air travelers. The com

plaint alleges, on information and belief, that the appellee

Greenville Airport Commission has from time to time re

ceived substantial sums of money from the government of

the United States for the purpose of constructing substan

tial portions of and maintaining operations at the airport

(Complaint, fl5; App. p. 3a).

7

Appellant is a resident of the State of Michigan and a

citizen of the United States. He is a civil service employee

of the United States Air Force at Headquarters, 10th Air

Force, Selfridge Air Force Base, Michigan. In such capac

ity he is required to travel about the United States. His

travels have taken him to the Greenville Airport and it is

reasonably expected that they will take him there again

(Complaint, 113; App. p. 2a). In the course of his travels

appellant, early in November 1958, was at Donaldson Air

port near Greenville, South Carolina, on air force business.

When it was time for appellant to return to Michigan the

air force travel officer arranged his ticket reservation and

appellant arrived at the Greenville Air Terminal about 4 :20

Friday, November 7,1958. Before boarding his plane which

was scheduled for a 5 :2l p.m. take-off, appellant seated him

self in the waiting room. Shortly thereafter the manager

of the Greenville Airport, appellee 0. L. Andrews, or

dered plaintiff out, advising him that “we have a waiting

room for colored folks over there.” Appellant protested

that this was a violation of his federal rights. Nevertheless,

appellee Andrews insisted that appellant go and as a con

sequence appellant was required to be racially segregated

(Complaint, H6; App. p. 3a). The complaint also alleges

that appellant is but one of a class of travelers constituted

of Negroes similarly situated whose numbers make it im

practicable to bring them all before the court and that they

seek common relief based upon common questions of law

and fact (Complaint, H2; App. p. 2a).

The complaint alleges that the segregation of appellant

under the circumstances described constitutes a denial of

equal protection and due process of law guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

and a denial of due process of law secured by the Fifth

Amendment to the United States Constitution and an un

constitutional burden of interstate commerce contrary to

8

Article 1, Section 8 of the Commerce Clause to the United

States Constitution.

In support of the motion for preliminary injunction ap

pellant filed an affidavit, which for all practical purposes

related his experience at the airport, and in so doing swore

to the factual averments of the complaint.

A R G U M E N T

I.

The court below erred in holding that Fourteenth

Amendment rights had not been denied, thereby dismiss

ing the complaint, and in holding that there was no

jurisdiction under Title 2 8 U. S. C. §1343 and Title 42

U. S. C. §1983.

Appellant will discuss the substantive question of Four

teenth Amendment rights and the question of jurisdiction

under Title 28 U. S. C. §1343 and Title 28 U. S. C. §1983

together, for it is obvious that they stand or fall as a single

argument. Indeed, it appears that the holding, in its

opinion (App. pp. 35a~39a) of the court below that there

was no jurisdiction was inseparable from its substantive

ruling that there was no claim stated upon which relief

could be granted.

The core of the complaint is that the Greenville Munici

pal Airport is a governmentally owned and operated facility

and that under the Fourteenth Amendment the airport

commission composed of governmental officers may not

practice racial discrimination at such a place. The juris

dictional argument is inextricably intertwined with the

substantive one for §1343 provides that the district courts

shall have jurisdiction of actions to redress deprivation,

under state law, of constitutional rights assuring equality:

“ (3) To redress the deprivation, under color of any

State law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or

9

usage, of any right, privilege or immunity secured by

the Constitution of the United States or by any Act

of Congress providing for equal rights of citizens or

of all persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States

And Title 42 IT. S. C. §1983 provides similarly that an

action lies for deprivation under state law of constitutional

rights:

“Every person who, under color of any statute, ordi

nance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or

Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citi

zen of the United States or other person within the

jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights,

privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution

and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an

action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceed

ing for redress.’’

Therefore, if appellant has been denied his substantive

constitutional civil rights an action will lie under these

jurisdictional provisions. Conversely, there would be no

point in discussing jurisdiction if no constitutionally pro

tected civil right is involved.

On the substantive question it is now clearly settled that

governmental officers may not practice racial segregation.

This is true as to intrastate travel, Browder v. Gayle, 142

F. Supp. 707, 717 (M. D. Ala. 1956), aff’d, 352 U. S. 903;

as to recreational facilities, Lonesome v. Maxwell, 220 F.

2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955); Dawson v. Mayor, 220 F. 2d 386

(4th Cir. 1955), aff’d 350 U. S. 877; as to elementary and

high schools, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483

(1954); as to graduate and professional schools, Frasier

v. Board of Trustees of the TJniv. of N. C., 134 F. Supp.

589, 592 (M. D. N. C. 1955), aff’d, 350 U. S. 979 (1956).

So far as airports are concerned there has been no decided

10

case involving Fourteenth Amendment rights, but when

separate-but-equal was still recognized as good law it was

held that the Fifth Amendment’s due process clause pro

hibited segregation compounded by inequality at the Wash

ington, D. C., airport. See Nash v. Air Terminal Servs.,

85 F. Supp. 545 (E. D. Va. 1949); see also, Air Terminal

Servs. Inc. v. Rentzel, 81 F. Supp. 611 (E. D. Va. 1949).

Because of the intimate correspondence between Fifth

Amendment due process and Fourteenth Amendment equal

protection and due process, see Bolling v. Sharpe, 347

U. S. 497, Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1, 19, the decisions

point to the obvious result that segregation at airports is

to be treated by the courts like all other governmentally

imposed segregation.

In the face of this uniform body of authority, however,

the opinion of the court below states:

“It is inferable from the complaint that there were

waiting room facilities at the Airport, but whether

those accorded the plaintiff: and other negroes were in

ferior, equal or superior to those accorded white citi

zens is not stated” (App. p. 37a).

But no authority whatsoever is suggested by the court be

low to indicate that the separate-but-equal doctrine is viable

today in the slightest degree. See, Browder v. Gayle, 142

F. Supp. 707, 717 (M. D. Ala. 1956), aff’d 352 U. S. 903

(1956); Flemming v. South Carolina Elect. & Gas Co., 224

F. 2d 752 (4th Cir. 1955), app. dism., 351 U. S. 901.

The opinion below relies heavily on Williams v. Howard

Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d 845 (4th Cir. 1959) (App.

p. 37a). But in that case the restaurant in question was

clearly a wholly privately owned entity, the proprietors

were not state officers. In this case the airport is clearly

a governmental facility; the appellees are state officers.

11

The opinion below relies on the fact that there is no

statute in the State of South Carolina requiring the segre

gation involved (App. p. 36a), but obviously, it is not

necessary that there be a statute for there to be state action.

The discriminatory acts of governmental officers without

benefit of statute are just as unconstitutional. Lonesome

v. Maxwell, supra.

The opinion below states:

“ . . . It is also inferable from the complaint that

the plaintiff did not go to the waiting room in quest

of waiting room facilities, but solely as a volunteer for

the purpose of instigating litigation which otherwise

would not have been started. The Court does not and

should not look with favor on volunteer trouble makers

or volunteer instigators of strife or litigation” (App.

p. 37a).

But there is no evidence to indicate that appellant re

quested equal rights as a volunteer for the purpose of

instigating litigation. Indeed, it is obvious that he was

acting in the course of his duties for the United iStates

Air Force, But even if the court’s wholly gratuitous as

sumption1 were true, Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202, holds

that an action certainly lies.

The opinion below states that the complaint is unclear

as to what is the nature of the discrimination complained

of.

1 The opinion also states:

“The Court’s attention has been directed to no law that confers on any

citizen, white or negro, the right or privilege of stirring up racial discord,

of instigating strife between the races, of encouraging the destruction of

racial integrity, or of provoking litigation, especially when to do so the

provoker must travel a great distance at public expense” (App. p. 37a).

There is certainly not a shred of evidence in the record indicating that

the factors mentioned in this quotation exists.

12

“ . . . From whom was he segregated? The affidavit

doesn’t say. Was he segregated from his family or

from his friends, acquaintances or associates, from

those who desired his company and he theirs? There

is nothing in the affidavit to indicate such to be true.

Was he segregated from people whom he did not

know and who did not care to know him? The affi

davit is silent as to that also. But suppose he was

segregated from people who did not care for his com

pany or association, what civil right of his was there

by invaded? If he was trying to invade the civil

rights of others, an injunction might be more prop-

erly invoked against him to protect their civil rights.

I know of no civil or uncivil right that anyone has,

be he white or colored, to deliberately make a nuisance

of himself to the annoyance of others, even in an effort

to create or stir up litigation” (App. p. 29a).

But, in the context of the complaint it is difficult to imagine

what could have been intended by it except to aver that

appellant was discriminated against racially. The com

plaint states:

“Early in November, 1958, plaintiff was at Donald

son Air Force Base near Greenville, South Carolina

on Air Force business. When it was time for him

to return to Michigan the Air Force travel officer

arranged his ticket reservations, and plaintiff arrived

at the Greenville Air Terminal at about 4:20 p. m.,

Friday, November 7, 1958. Before boarding his plane,

which was scheduled for a 5:21 p. m. take-off, plain

tiff seated himself in the waiting room. Shortly there

after the manager of the Greenville Airport ordered

plaintiff out, advising him that ‘we have a waiting

room for colored folks over there.’ Plaintiff informed

him that he was an interstate traveler and that plain

13

tiff believed that said manager’s action was in viola

tion of federal law and ICC regulations. Neverthe

less, said manager insisted that plaintiff go. As a

consequence plaintiff was required to be segregated”

(Complaint H3, App. 2a).

Moreover, the opinion of the court below itself clearly

interprets the complaint as one assailing the racial segre

gation of the plaintiff by the defendants at the municipal

airport. The reference to separate-but-equal in the opinion,

discussed above, and the court’s statement that “even

whites, as yet, still have the right to choose their own

companions and associates, and to preserve the integrity

of the race with which God Almighty has endowed them”

(App. 30a) both acknowledge that this case involves an

issue of racial discrimination. The statement in the opinion

that there is no state law requiring racial segregation in

the airport waiting room and the court’s quotation from

the complaint—“we have a waiting room for colored folks

over there”—would hardly leave any doubt in the mind

of an objective reader, as there obviously was no doubt in

the mind of the court, that here is anything but a com

plaint asserting constitutional rights against racial dis

crimination.

Appellants submit that here there is no ambiguity at

all in the complaint. It requires nothing but an objective

reading to comprehend what plaintiff’s claim is. But the

federal rules go further than is here required. As was

stated in Conley v. Gibson, 355 U. S. 41, 47:

The respondents also argue that the complaint

failed to set forth specific facts to support its gen

eral allegations of discrimination and that its dis

missal is therefore proper. The decisive answer to

this is that the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure do

14

not require a claimant to set out in detail the facts

upon which he bases his claim. To the contrary, all

the Eules require is ‘a short and plain statement of

the claim’ that will give the defendant fair notice

of what the plaintiff’s claim is and the grounds upon

which it rests. The illustrative forms appended to

the Eules plainly demonstrate this. Such simplified

‘notice pleading’ is made possible by the liberal op

portunity for discovery and the other pretrial pro

cedures established by the Eules to disclose more

precisely the basis of both claim and defense and to

define more narrowly the disputed facts and issues.

Following the simple guide of Eule 8(f) that ‘all

pleadings shall be so construed as to do substantial

justice,’ we have no doubt that petitioners’ complaint

adequately set forth a claim and gave the respondents

fair notice of its basis. The Federal Eules reject the

approach that pleading is a game of skill in which

one misstep by counsel may be decisive to the outcome

and accept the principle that the purpose of pleading

is to facilitate a proper decision on the merits. Cf.

Maty v. Grasselli Chemical Co., 303 U. S. 197, 82 L.

ed. 745, 58 S. Ct. 507.

If, as has been established, the defendants have wrong

fully imposed a racial classification on plaintiff, a cause

of action lies under the Fourteenth Amendment and the

District Court had jurisdiction to hear the cause.

Among the jurisdictional provisions upon which appellant

bases the complaint was Title 28 U. S. C. §1343. Appellees’

motion to strike which attacked the complaint’s assertion

of federal question of jurisdiction under Title 28 U. S. C.

§1331 and diversity jurisdiction under Title 28 U. S. C.

§1332, made no issue whatsoever of the averment of juris

15

diction under Title 28 U. S. C. §1343, although at the oral

argument jurisdiction on this ground was assailed also.

It is obvious, however, that the defendants’ motion to

strike was correct in not attacking §1343 jurisdiction.

This section since Hague v. G. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496, has been

the basis upon which almost all civil rights cases have been

brought. As Mr. Justice Stone wrote in that case §1343

would be meaningless unless it permitted suit for redress

of civil rights incapable of pecuniary valuation:

Since the two provisions [§1331 and §1343] stand

and must be read together, it is obvious that neither is

to be interpreted as abolishing the other. . . . By

treating [§1343(3)] as conferring federal jurisdiction

of suits brought under the Act of 1871 in which the

right asserted is inherently incapable of pecuniary

valuation, we harmonize the two parallel provisions of

the Judicial Code, construe neither as superfluous, and

give to each a scope in conformity with its history and

manifest purpose. 307 U. S. at 530.

Appellants respectfully submit that many of the authori

ties are so well discussed and summarized in an exhaustive

analysis of federal jurisdiction in civil rights cases which

appears in 2 R. R. L. R. 269 (1957), from which the fol

lowing quotation is excerpted, that little further need be

added:

Jurisdiction under Section 1343 has been sustained

in actions by Negro applicants for declaratory judg

ments against universities (Johnson v. Board of Trus

tees of University of Kentucky, 83 F. Supp. 707, E. D.

Ky. 1949; Wrighten v. Board of Trustees of University

of S. C., 72 F. Supp. 948, E. D. S. C. 1947), by persons

excluded on account of race from government-operated

places of recreation (Holmes v. Atlanta, 124 F. Supp.

16

290, N. D. Ga. 1954, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 146, 1956,

affirmed 223 F. 2d 93, 5th Cir. 1955, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep.

149, 1956, vacated and remanded with direction 350

U. S. 879, 76 S. Ct. 141, 100 L. E d .----- , 1955, 1 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 14, 1956, golf courses; Williams v. Kan

sas City, Mo., 104 F. Supp. 848, W. D. Mo. 1952,

affirmed 205 F. 2d 47, certiorari denied 346 U. S. 826,

74 S. Ct. 45, 98 L. Ed. 351, 1953, swimming pool;

Lopez v. Seccombe, 71 F. Supp. 769, S. D. Cal. 1947,

swimming pool and park facilities), by Negro teachers

asking a declaratory judgment or an injunction against

salary discrimination (Thompson v. Gibbes, 60 F.

Supp. 872, E. D. S. C. 1945; Davis v. Cook, 55 F. Supp.

1004, N. D. Ga. 1944; Thomas v. Hibbitts, 46 F. Supp.

368, M. D. Tenn. 1942; Mills v. Board of Education,

30 F. Supp. 245, D. Md. 1939), and by children seek

ing an injunction against segregation in a city’s

schools (Allen v. School Board of the City of Char

lottesville, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 886, W. D. Va. 1956;

Romero v. Weakley, 226 F. 2d 399, 9th Cir. 1955, 1

Race Rel. L. Rep. 48, 1956). 2 R. R. L. R. at 283.

See also Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780, especially at

787 (5th Cir. 1958).

17

II.

The court below erred in dismissing the complaint

which alleged that plaintiff, an interstate passenger in

the course of his interstate journey, was racially segre

gated in his use of the facilities at the Greenville Mu

nicipal Airport contrary to Article 1, §8 of the United

States Constitution (Commerce Clause).

In Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 the United States

Supreme Court held that Virginia could not require racial

segregation on interstate buses. The basis of the decision

is that the enforcement of such seating arrangements so

disturbed Negro passengers in interstate motor travel that

a burden on interstate commerce was created in violation

of Article 1, Section 8 of the United States Constitution.

Id. at 381-82. The United States Supreme Court held that

absent congressional legislation on the subject the Con

stitution required “a single uniform rule to .promote and

protect national travel.” Id. at 386. An identical rule has

been applied to similar racial restrictions on commerce

imposed by rules of the carrier enforced by arrest and

criminal conviction. Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines,

177 F. 2d 949 (6th Cir. 1949); Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d

879 (4th Cir. 1951), cert, denied 341 U. S. 941. It is obvious

that interstate air travel cannot be conducted without

airports and airport waiting rooms and anyone who has

flown on commercial planes knows that it is necessary

to arrive at the airport substantially in advance of de

parture time to allow for ticketing, receipt of baggage and

other incidents of air transportation. In fact, in this case,

the complaint reveals that appellant arrived at approxi

mately one hour befor flight time, certainly not an inordi

nate or unusual length of time in advance of the flight, and

seated himself in the waiting room as any air traveler

18

would expect to do. To humiliate him on the basis of race

and require him to go to a waiting room for ‘‘colored folks”

certainly may be expected to embarrass and disturb anyone

so treated. Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816, 825,

while dealing with the Interstate Commerce Act, con

demned racial segregation in railroad dining cars as “em-

phasiz[ing] the artificiality of the difference in treatment

which serves only to call attention to a racial classification

of passengers holding identical tickets and using the same

public dining facility.” These same considerations apply

with equal force to the restrictions imposed upon plaintiff.

The natural and expectable result is either to discour

age the use of air travel by Negroes or to encourage them

to arrive at the terminal immediately before flight time so

that the waiting room will not have to be used. This latter

result would, of course, hamper air travel by interfering

with the orderly processing of passengers sufficiently in

advance of flight time. A third possibility—-submission to

segregation or waiting outside of the building—is so ob

viously an unconstitutional condition as to require no fur

ther discussion. See, Frost Trucking Co. v. R. R. Commis

sion, 271 U. S. 583; Alston v. School Hoard of the City of

Norfolk, 112 F. 2d 992 (4th Cir. 1940), cert, denied 311

U. S. 693 (1940).

The airport was built as an integral and essential part

of interstate air travel. It cannot seriously be urged that

because the terminal is stationary or local as to perhaps

some persons, it is therefore not in interstate commerce

at all and that petitioner’s treatment for that reason did

not constitute a burden on interstate commerce. The

United States Supreme Court has held that a transaction

with a red cap at a railroad station is in interstate com

merce, N. Y. N. H. & H. R. Co. v. Nothnagle, 346 U. S. 128.

As stated in that case at page 130, “Neither continuity of

19

interstate movement nor isolated segments of the trip can

be decisive. ‘The actual facts govern. For this purpose,

the destination intended by the passenger when he begins

his journey and known to the carrier, determines the char

acter of the commerce,’ ” citing Sprout v. South Bend,

277 U. S. 163, 168. Moreover, grain elevators surely as

stationary as the air terminal have been held to be in

interstate commerce. See Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp.,

331 U. S. 218, 229. And taxi service between two rail

terminals in Chicago which to the man in the street might

look like ordinary local taxi traffic also has been held to

be in interstate commerce. United States v. Yellow Cab

Co., 332 IT. S. 218, 228.

Therefore, to have racially segregated plaintiff, an in

terstate traveler, in the course of an essential use of the

waiting room during his interstate journey did constitute

a burden on interstate commerce and certainly the com

plaint as to this count should not have been dismissed.

III.

The court below erred in dismissing the complaint

insofar as it alleged that on information and belief the

Greenville Airport Commission has from time to time

received substantial sums of money from the govern

ment of the United States for the purposes of construct

ing substantial portions of and maintaining operations

at said Airport whereby the discrimination against plain

tiff violated the due process clause of the Fifth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

As fundamental as the Fourteenth Amendment’s pro

hibition on state imposed racial discrimination is the Fifth

Amendment’s proscription of federally imposed racial dis

crimination. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497. To the ex

20

tent that the airport in question has been built and main

tained by substantial sums of money from the federal

government the Fifth Amendment therefore also applies.

The case involving the Washington, D. C. airport, discussed

supra, Nash v. Air Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545

(E. D. Va. 1949), held in 1949 before the separate but

equal doctrine was finally discredited, that a federally

owned airport may not segregated where Negro facilities

are inferior to white ones. Obviously, in view of later

legal developments which definitively have struck down

separate but equal, such an airport cannot now segregate

whether the facilities are equal or not. Similarly, Heyward

v. Public Housing Administration, 238 F. 2d 689 (5th Cir.

1956), held that a cause of action under the Fifth Amend

ment was stated against the Public Housing Authority in

charging it with racial discrimination in expending fed

eral funds for public housing. Id. at 696. And, of course,

Bolling v. Sharpe, supra, establishes a parallel proposition

with regard to federally maintained schools.

There is neither reason in logic nor authority why sub

stantial sums of federal money should be insulated from

the constitutional requirement of nondiscriminatory appli

cation by the fact that said sums may be given to state offi

cers for maintenance of a facility rather than said facility

being maintained by federal officers themselves. Plaintiff

respectfully submits, therefore, that paragraph 5 of the

complaint alleging this federal participation also states

a cause of action and that this portion of the complaint

should not have been dismissed or stricken as immaterial.

21

IV.

The court below, contrary to Rule 2 3 ( a ) ( 3 ) of the

Federal Mules of Civil Procedure, erred in striking para

graph 2 of the complaint which alleges that this is a class

action.

Rule 23(a)(3) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

states:

Rule 23. Class Actions.

(a) Representation. If persons constituting a

class are so numerous as to make it impracticable

to bring them all before the court, such of them, one

or more, as will fairly insure the adequate represen

tation of all may, on behalf of all, sue or be sued,

when the character of the right sought to be enforced

for or against the class is

# # # * *

(3) several, and there is a common question of law

or fact affecting the several rights and a common

relief is sought.

The complaint alleges that:

Plaintiff brings this action pursuant to Rule 23(a)

(3) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for him

self and on behalf of all other Negroes sim ila r ly

situated, whose numbers make it impracticable to

bring them all before the court; they seek common

relief based upon common question of law and fact.

(Complaint ]\2, App. p. 2a.)

Clearly this is an adequate statement under the scope

of the rule and appellant should have been permitted to

make his proof without this paragraph having been

22

stricken and the complaint having been dismissed out of

hand. The authority for dismissing as a class action cited

by the court below was Jinks, et al. v. Hodge, 11 F. R. D.

346 (E. D. Tenn. 1951).

However, the Jinks case holds flatly contrary to the

proposition for which it is cited.

That case involved a complaint which sought an injunc

tion and also was sounded in tort. As to the cause of action

in tort the court in Jinks held, as the court below here has

pointed out, that a class action was inappropriate.

However, as to that portion of the complaint which

prayed for an injunction—as the complaint in the instant

case prayed—Jinks, et al. v. Hodge held that a class action

was appropriate.

The action purports to be a class suit under Rule 23

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 28 U. S. C. A.

So far as the action seeks an injunction, this suit may

be considered a class action. 11 F. R. D. at 347.

In Frasier v. Board of Trustees of the University of

North Carolina, 134 F. Supp. 589 (M. D. N. C. 1955), aff’d

350 U. S. 979, the plaintiffs sought a declaratory judgment

that the order of defendant board denying plaintiffs’ ad

mission to the university was a violation of their rights

under the Fourteenth Amendment. The board defended

by stating that such a judgment in a class action would

deprive the school of its power to pass upon the qualifica

tions of each individual applicant to the university. The

court in rejecting defendant’s position stated:

Such is not the case. The action in this instance is

within the provisions of Rule 23(a) of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure because the attitude of the

University affects the rights of all Negro citizens of

23

the State who are qualified for admission to the under

graduate schools. But we decide only that the Negroes

as a class may not be excluded because of their race

or color; and the Board retains the power to decide

whether the applicants possess the necessary qualifica

tions. This applies to the plaintiffs in the pending

case as well as to all Negroes who subsequently apply

for admission. 134 F. Supp. at 593.

Similarly, in this case one may conceive of circumstances

in which a traveler might be excluded from the airport.

Such a circumstance, however, would not include the

traveler’s race.

In any event, all that the class action aspect of this suit

seeks is an injunction against racial distinctions practiced

against appellant “and all other Negroes similarly situ

ated.” Plaintiff should be permitted to make his proof

unless, of course, it is inherently incredible that other

Negroes employ air transportation at the Greenville Air

port—a contention which would not be worthy of serious

consideration.2 Indeed, the existence of a place for “colored

folks,” to use appellee manager’s language quoted in the

complaint, would belie an assertion that no other Negroes

use the terminal.

2 See the affidavit of Freda McPherson (App. p. 18a) (which was ex

cluded from consideration by the court below) and the proffer of her testimony

(App. pp. 23a; 25a) which was not permitted. This affidavit and proffer are

hardly needed to sustain the proposition that Negroes other than defendant

employ air transportation, but merely serve to confirm a matter of common

knowledge.

24

y.

The court below erred in denying appellant’s appli

cation for preliminary injunction which was based upon

an uncontroverted affidavit supporting the allegations of

the complaint.

Rule 65 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides

for the issuance of preliminary injunctions upon notice

and hearing. It is a well recognized proposition, of course,

that whether or not to issue a preliminary injunction is in

the discretion of the court. However, the existence of “dis

cretion” does not mean that there is unfettered discretion.

As Justice Brandeis wrote in Union Tool Co. v. Wilson,

259 U. S. 107, 112, “legal discretion . . . does not extend

to a refusal to apply well-settled principles of law to a

conceded state of facts.” And as was held in Clemons v.

Board of Education of Hillsboro, Ohio, 228 F. 2d 853, 857

(6th Cir. 1956), cert. den. 350 IJ. S. 1006, a suit in which

Negro children sought the abolition of segregated school

ing, “it is generally held that the trial court abuses its

discretion when it fails or refuses properly to apply the

law to conceded or undisputed facts.” The Clemons case

further stated:

If injunction will issue to protect property rights and

“to prevent any wrong” ; . . . it will issue to protect

and preserve basic civil rights such as these for which

the appellant seeks protection. While the granting

of an injunction is within the judicial discretion of the

District Judge, extensive research has revealed no

case in which it is declared that a judge has judicial

discretion by denial of an injunction to continue the

deprivation of basic human rights.

25

The application for preliminary injunction was based

upon appellant’s affidavit which supported the averments

of the complaint and which at this point in the brief it

would be redundant to once more recite. Much is made

by the opinion of the court of the allegation in the affidavit

that “a man purporting to be the manager” ordered the

appellant to leave the white waiting room (App. p. 10a).

It should be noted also that in paragraph 5 of the affidavit

it is stated that “plaintiff is further informed that 0. L.

Andrews [appellee herein] is manager of the said Green

ville Municipal Airport” (App. pp. 9a-10a). Of course, the

appellant with information available to him at the time

could not allege other than that appellee Andrews held

himself out to be manager. But there is no denial of the

fact that appellee Andrews is the manager and the use

of the word “purporting” merely means in the context of the

affidavit “professing outwardly” (Webster’s New Interna

tional Dictionary, 2d ed.). If appellee 0. L. Andrews were

not the manager one might properly have expected a motion

to dismiss him from the suit as an improper party. No

such motion, of course, was filed.

It is respectfully suggested that if any issue were to

be made of this factor, it would behoove appellees to

have filed a counter-affidavit and not to argue tenuously

with respect to the interpretation of plain language and

indeed the situation with which appellant was confronted.

There is no reason why in this case the court below should

not have followed the general rule which is that a verified

complaint or affidavit standing undenied may be presumed

true. See Royal Brewing Co. v. Missouri K. T. Ry. Co.,

217 F. 146 (D. Kan. 1914); Gossnell v. Spang, 84 F. 2d

889 (3rd Cir. 1936), cert. den. 299 U. S. 605.

26

VI.

The court below erred in not permitting appellant to

introduce evidence on th e motion for preliminary in

junction.

At the hearing of the motion for preliminary injunc

tion appellant sought to introduce additional affidavits.

One affidavit, that of appellant, merely related the aver

ments of the first affidavit filed with the original motion

for preliminary injunction and also stated that the dis

criminatory practice in question was still being maintained

on the day before the hearing (App. p. 15a). Another affi

davit, that of Freda McPherson, a resident of Greenville,

stated that she too knew of the existence of the discrimina

tory practice assailed in the complaint (App. p. 18a).

Appellees objected to the introduction of these affidavits

on the ground that they had not had sufficient oppor

tunity to study these documents and decide upon a course

of action with respect to them prior to the hearing (App.

pp. 21a-22a). The court refused to permit the affidavits

to be introduced because the motion for preliminary in

junction “mentions nothing about any further affidavits

to be filed” (App. p. 21a).

At this time appellant requested permission to place

on the witness stand two witnesses: appellant and Mrs.

McPherson who would testify, it was proffered, concerning

the discrimination in question (App. pp. 23a, 25a). This

the court denied, apparently on the ground that the mo

tion had not stated that witnesses would be presented on

the hearing (App. pp. 23a-24a).

Rule 65 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure requires

that a motion for preliminary injunction “shall be set

. . . for hearing . . . ” As stated in Hawkins v. Board of

27

Control of Florida, 253 F. 2d 752, 753 (5th Cir. 1958)

“hearing” requires that there be a trial of an issue of

fact:

Hearing requires a trial of an issue of fact. Trial

of an issue of fact necessitates an opportunity to pre

sent evidence. Sims v. Greene, 161 F. 2d 87 (3rd Cir.

1947). Since appellant was not given the opportunity

to present evidence in his behalf, the order denying the

preliminary injunction must be set aside.

It is inherent in the application for preliminary injunc

tion and the requirement that a hearing be given thereon

that testimony may be proffered. Indeed, it generally has

been held that although a motion for preliminary injunc

tion can be decided on affidavits, especially upon uncon

troverted affidavits as in this case, it is better that oral

testimony be heard. 7 Moore’s Federal Practice jf65.04[3],

especially page 1639 (2d ed.).

The motion while stating that it was based upon ap

pellant’s affidavit, certainly did not state that the appended

affidavit would be the only grounds upon which appellant

would move. The implicit requirement of a hearing cer

tainly required that appellant be permitted to make full

and fair proof. While an objection of hearsay or insuffi

cient time might be made with respect to affidavits certainly

no such objection is tenable with respect to witnesses. It

is normally expected that they will be heard and a full

opportunity to cross examine them is, of course, always

granted.

In view of appellees’ failure to traverse even the affidavit

which had been before them or to produce witnesses in

opposition to it, it seems inappropriate for them to argue

that if they had known that witnesses would be presented

28

—which they reasonably might have expected—they would

have been prepared in some other manner.

Of course the opportunity to present witnesses, it may

be argued, was not flatly denied, but merely denied at

that time. It might have been that at some later date the

court would have permitted witnesses to appear on the

motion for preliminary injunction, or such an inference

at least may be urged. However, appellees had notice of

a hearing which implies that testimony may be taken.

Moreover, appellant had waited six months for hearing

on his motion for preliminary injunction. Further delay

would for all practical purposes have completely defeated

the purpose which a preliminary injunction is to serve,

that is, according speedy relief.

While, it is submitted, on appellant’s uncontroverted

affidavit alone it was an abuse of discretion to deny appel

lant his preliminary injunction, further ground for reversal

exists in the fact that appellant was denied a complete

hearing by the arbitrary exclusion of his witness’ testimony.

W herefore fo r the foregoing reasons it is respectfully

submitted tha t the judgm ent below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

L incoln C. J enkins, J r.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

T hurgood Marshall

J ack G r e e n b e r g

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

A t to r n e y s f o r A p p e l la n t

APPENDIX TO APPELLANT’S BRIEF

la

HttM States SiHtrirt (Umirt

F oe the W estern District of South Carolina

Greenville Division

R ichard B. H enry,

-v.-

Plaintiff,

Greenville A irport Commission ; 0. L. A ndrews, Manager,

Greenville Municipal A irport; W illiam T. A dams,

Chairman, Greenville A irport Commission and H ugh

K. A iken ; Olin H. Spann ; E dward McGrady ; W illiam

B. Coxe, Members of the Greenville A irport Commis

sion,

Defendants.

Complaint

1. (a) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1331 as this action

arises under Article I, Section 8 and the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States, Section 1;

and Title 42, United States Code, Section 1981 and the

matter in controversy exceeds, exclusive of interest and

costs, the sum or value of Ten Thousand ($10,000.00) Dol

lars.

(b) The jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1343. This action is

authorized by Title 42, United States Code, Section 1983 to

be commenced by any citizen of the United States or other

person within the jurisdiction thereof to redress the depri

vation, under color of a state law, statute, ordinance, regula

tion, custom or usage, of rights, privileges and immunities

2a

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States, Section 1, and by Title 42, United

States Code, Section 1981, providing for the equal rights

of citizens and of all persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States.

(c) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title

28, United States Code, Section 1332, plaintiff being a

citizen of the State of Michigan and defendants being

citizens of the State of South Carolina and the matter in

controversy exceeding the sum or value of Ten Thousand

($10,000.00) Dollars exclusive of interest and costs.

2. Plaintiff brings this action pursuant to Rule 23(a)(3)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for himself and on

behalf of all other Negroes similarly situated, whose num

bers make it impracticable to bring them all before the

court; they seek common relief based upon common ques

tions of law and fact.

3. Plaintiff, Richard B. Henry, is a resident of the City

of Ferndale and State of Michigan and a citizen of the

United States. He is a civil service employe of the United

States Air Force at Headquarters Tenth Air Force, Self

ridge Air Force Base, Michigan. In such capacity he is

required to travel about the United States. His travels

have taken him to the Greenville, South Carolina Airport

and it is reasonably expected that they will take him there

again.

4. (a) Defendant, Greenville Airport Commission, is a

commission created by the Acts and Joint Resolutions of

the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, No.

919 (1928), a copy of which is appended to this complaint as

Exhibit “A”. Said commission is a governmental body of

the State of South Carolina, and operates the Greenville,

South Carolina Airport.

C o m p la in t

3a

(b) Defendant 0. L. Andrews is manager of the Green

ville Municipal Airport.

(c) Defendant William T. Adams is chairman of the

Greenville Airport Commission.

(d) Defendants Hugh K. Aiken, Olin H. Spann, Edward

McCrady and William B. Coxe are members of the Green

ville Airport Commission.

5. Plaintiff alleges on information and belief that said

Greenville Airport Commission has from time to time re

ceived substantial sums of money from the government of

the United States for the purposes of constructing sub

stantial portions of and maintaining operations at the

Greenville Municipal Airport.

6. Early in November, 1958, plaintiff was at Donaldson

Air Force Base near Greenville, South Carolina on Air

Force business. When it was time for him to return to

Michigan the Air Force travel officer arranged his ticket

reservations, and plaintiff arrived at the Greenville Air

Terminal at about 4:20 P. M., Friday, November 7, 1958.

Before boarding his plane, which was scheduled for a 5 :21

P. M. take-off, plaintiff seated himself in the waiting room.

Shortly thereafter the manager of the Greenville Airport

ordered plaintiff out, advising him that “we have a waiting

room for colored folks over there.” Plaintiff informed him

that he was an interstate traveler and that plaintiff believed

that said manager’s action was in violation of federal law

and ICC regulations. Nevertheless, said manager insisted

that plaintiff go. As a consequence plaintiff was required

to be segregated.

7. Requiring plaintiff to be segregated denied to him

rights guaranteed by the equal protection clause of the

C o m p la in t

4a

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution,

and by the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment to

the United States Constitution, and constituted a burden on

interstate commerce forbidden by Article I, Section 8 of the

United States Constitution.

W herefore plaintiff and those similarly situated suffer

and are threatened with irreparable injury by the acts

herein complained of. They have no plain, adequate or

complete remedy to redress these wrongs other than this

suit for an injunction. Any other remedy would be at

tended by such uncertainties and delays as to deny sub

stantial relief, would involve multiplicity of suits, cause

further irreparable injury and occasion damage, vexation

and inconvenience, not only to the plaintiff and those sim

ilarly situated, but to defendants as governmental agencies.

A nd wherefore plaintiff respectfully prays that this

Court enter interlocutory and permanent injunctions re

straining defendants from making any distinction based

upon color in regard to service at the Greenville Municipal

Airport; and that the court allow plaintiff his costs and

such other relief as may appear to the court to be just.

Respectfully submitted,

L incoln C. J enkins, J r.

11071/2 Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Thurgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

C o m p la in t

A t to r n e y s f o r P la in t i f f

5a

EXHIBIT “A” ANNEXED TO COMPLAINT

ACTS AND JOINT RESOLUTIONS

of the

GENERAL ASSEMBLY

of the

State of South Carolina

Passed At The Regular Session Of 1928

No. 919

A n A ct to Create an Airport Commission for the City and

County of Greenville and define its Powers and Duties

and to Authorize the City of Greenville to make Certain

Donations to Said Commission.

Section 1. G r e e n v il l e A ir p o r t C o m m is s io n -—-Ap p o in t

m e n t — Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State

of South Carolina: There is hereby created a Commission

for the City and County of Greenville, to be known as

Greenville Airport Commission. This Commission shall

consist of five members to be selected as follows: T wto by

the City Council of the City of Greenville; two by the

Greenville County Delegation in the General Assembly and

one to be selected by a majority vote of the four selected

as hereinabove provided.

Section 2. T e r m s— That the term of office of the members

of this Commission shall be as follows: The two appointed

by the Greenville County Delegation shall serve for a

period of two years; the two appointed by the City Council

shall serve for a period of four years; and the one selected

by this Commission shall serve for a period of six years;

6a

and at the expiration of the terms of office of the Commis

sion as hereinabove selected, the term of office of each

Commissioner shall be for a period of two years and until

his successor is appointed and qualifies.

Section 3. Chairman—The Commission herein appointed

shall select one of its number as Chairman.

Section 4. P owers—The Commission herein created is

hereby vested with the power to receive any gifts or do

nations from any source, and also to hold and enjoy prop

erty, both real and personal, in the County of Greenville,

as granted to individuals under the laws of this State, for

the purpose of establishing and maintaining aeroplane

landing fields and county parks in the County of Green

ville; and to make such rules and regulations as may be

necessary in the conduct and operation of said aeroplane

landing fields and county parks.

Section 5. City op Greenville May A id—The City of

Greenville is hereby empowered and authorized to appro

priate and donate to said Commission such sums of money

as it may deem expedient and necessary for the purposes

aforesaid.

Section 6. Abandonment op A irport—That in ease the

property acquired by the Commission as aforesaid shall

cease to be used for the purposes herein provided, then all

of the said property, both real and personal, may be sold

by the Commission and converted into cash and said pro

ceeds shall be divided among the City of Greenville, the

County of Greenville, the Park and Tree Commission of

the City of Greenville, and the American Legion organiza

tion of the County of Greenville, in equal proportion, and

E x h ib i t “A ” A n n e x e d to C o m p la in t

7a

to that end the said Commission is hereby authorized by

such officers as it may designate to make, execute and

deliver deed or deeds of conveyance to any and all of said

property.

Section 7. All Acts or parts of Acts inconsistent herewith

are hereby repealed.

Section 8. This Act shall take effect immediately upon its

approval by the Governor.

Approved the 10th day of March, A.D. 1928.

E x h ib i t “A ” A n n e x e d to C o m p la in t

8a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe the W estern District of South Carolina

Greenville Division

M otion for Prelim inary Injunction

[same title]

Plaintiff moves the court to grant a preliminary injunc

tion against defendants and each of them and their agents,

servants and attorneys and all persons in active concert

and participation with them pending the final determina

tion of this action and until the further order of this court

restraining them from making any distinctions based upon

color in regard to service at the Greenville Municipal Air

port on the grounds that unless restrained by this court

defendants will commit the acts referred to which will

result in irreparable injury, loss and damage to plaintiff

during the pendency of this action, as more fully appears

from the affidavit of plaintiff attached hereto and made a

part hereof.

L incoln C. J enkins, J r .

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

T hurgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

A t to r n e y s f o r P la in t i f f .

9a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob the W estern District of South Carolina

Greenville Division

Affidavit o f R ichard B . H enry

[ sa m e t it l e ]

R ichard B. H enry being duly sworn hereby deposes and

say s :

1. He is the plaintiff in the above-entitled case.

2. This is an action for interlocutory and permanent

injunction to restrain defendants from making any dis

tinctions based upon color at the Greenville Municipal

Airport.

3. Plaintiff is a resident of the City of Ferndale, Michi

gan and a citizen of the United States.

4. Plaintiff is a civilian employe of the United States

Air Force at Headquarters Tenth Air Force, Selfridge Air

Force Base, Michigan. In such capacity his travels take

him about the country, have taken him to the Greenville

Air Terminal and may be expected to take him there again.

5. Plaintiff is informed that defendant Greenville Air

port Commission is a commission created by the laws of

the State of South Carolina, that it operates the Greenville

Municipal Airport and that the chairman of said commis

sion is William T. Adams; Hugh K. Aiken, Olin H. Spann,

Edward McCrady and William B. Coxe are members of

the Greenville Airport Commission. Plaintiff is further

10a

informed that 0. L. Andrews is Manager of said Green

ville Municipal Airport.

6. Early in November, 1958, plaintiff was at Donaldson

Air Force Base, near Greenville, South Carolina on Air

Force business. When it was time for him to return to

Michigan the Air Force travel officer arranged his ticket

reservations, and plaintiff arrived at the Greenville Air

Terminal at about 4:20 P.M., Friday, November 7, 1958.

7. Before boarding his plane, which was scheduled for

a 5 :21 P.M. take-off, plaintiff seated himself in the waiting

room. Shortly thereafter a man purporting to be the man

ager ordered plaintiff out, advising him that “we have a

waiting room for colored folks over there.” Plaintiff in

formed him that he was an interstate traveler and that

plaintiff believed that said manager’s action was in viola

tion of federal law and ICC regulations. Nevertheless,

said manager insisted that plaintiff go. As a consequence

plaintiff was required to be segregated.

8. The reason why plaintiff will suffer great irreparable

damage unless this injunction is granted is that he reason

ably expects during the course of his employment in the

United States Air Force that his travels will, on future

occasions, take him to the Greenville Municipal Airport

and that to be denied the opportunity to use said airport

without being subjected to racial discrimination is a denial

of his constitutional rights and a gross inconvenience in

the course of his interstate travels.

A f f id a v i t o f R ic h a r d B . H e n r y

R ichard B. H enry

11a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe the Western District of South Carolina

Greenville Division

Civil Action No. 2491

M otion to Strike

[ same title]

T o H onorable George Bell T immerman, U nited States

D istrict J udge for the E astern and W estern Districts

of South Carolina :

The defendants, under the provisions of Rule 12 (f) of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Title 28, move to

strike certain allegations of the Complaint of the plaintiff

in the above entitled case, to-wit:

“1. (a) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1331 as this action

arises under Article I, Section 8 and the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, Sec

tion 1; and Title 42, United States Code, Section 1981 and

the matter in controversy exceeds, exclusive of interest

and costs, the sum or value of Ten Thousand ($10,000.00)

Dollars.”

“1. (c) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1332, plaintiff being

a citizen of the State of Michigan and defendants being

citizens of the State of South Carolina and the matter in

controversy exceeding the sum or value of Ten Thousand

($10,000.00) Dollars exclusive of interest and costs.”

12a

“2. Plaintiff brings this action pursuant to Rule 23

(a) (3) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for him

self and on behalf of all other Negroes similarly situated,

whose numbers make it impracticable to bring them all

before the court; they seek common relief based upon com

mon questions of law and fact.”

“5. Plaintiff alleges on information and belief that said

Greenville Airport Commission has from time to time re

ceived substantial sums of money from the government

of the United States for the purposes of constructing sub

stantial portions of and maintaining operations at the

Greenville Municipal Airport.”

on the ground that it appears upon the face of the Com

plaint that the said allegations are immaterial.

s/ T homas A. W offord

214 Masonic Temple

Greenville, South Carolina

L ove, T hornton & Arnold

By: s/ W. H. Arnold

103 Lawyers Building