Heyward v. Public Housing Administration Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Heyward v. Public Housing Administration Reply Brief for Appellants, 1954. 945c1f24-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5eeb1785-04d2-4233-8710-4745c5ed854b/heyward-v-public-housing-administration-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

X

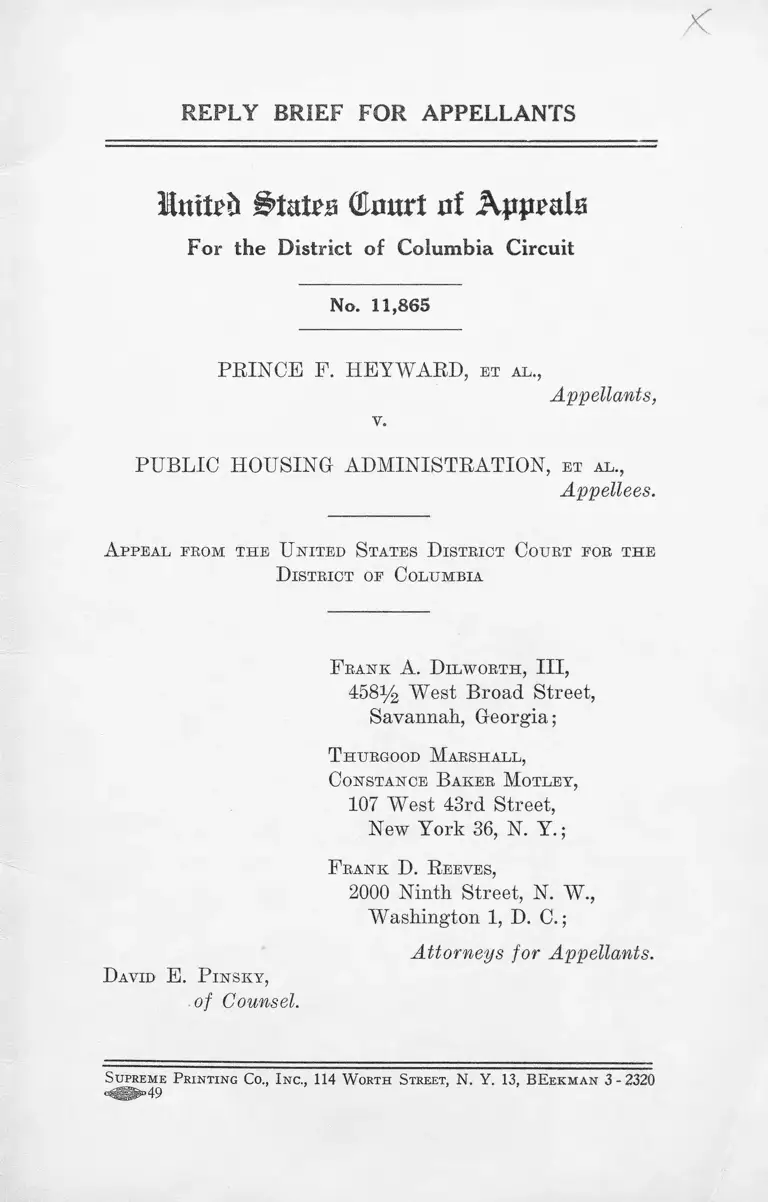

REPLY BRIEF FO R A PPELLA N TS

Qkrurt nf Appeals

For the D istrict of Colum bia C ircuit

No. 11,865

PRINCE F. HEYWARD, e t a l .,

Appellants,

v.

PUBLIC HOUSING ADMINISTRATION, et al .,

Appellees.

A p p e a l e e o m t p ie U n it e d S t a t e s D is t r ic t C o u r t f o r t h e

D is t r ic t o f C o l u m b ia

F r a n k A . D il w o r t h , III,

458% West Broad Street,

Savannah, Georgia;

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l ,

C o n s t a n c e B a k e r M o t l e y ,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, N. Y.;

F r a n k D . R e e v e s ,

2000 Ninth Street, N. W.,

Washington 1, D. C.;

D avid E. P in s k y ,

of Counsel.

Attorneys for Appellants.

S upreme Printing Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3-2320

«^i8SD49

I N D E X

PAGE

I. The Action is Not Premature by Appellees’ Own Admis

sion ....................................................................................... 1

II. There is a Justiciable Controversy Between These

Appellees and Appellants .................................................. 1

III. Appellees Have Injured Appellants By Denying Them

The Statutory Preference For Admission........................ 9

IV. The Savannah Housing Authority is Not An Indis

pensable Party ................................................................... 10

Conclusion ....................................................................................... 15

TABLE OF CASES

Ainsworth v. Barn Ballroom Company, 157 F. 2d 97 (C. A. 4th, 1946) .. 14

Balter v. lckes, 89 F. 2d 856 (C. A. D. C. 1937) ....................................... 13

Barrow v. Shields, 17 How. (U. S.) 130 ...................................................... 14

Berlinsky v. Wood, 178 F. 2d 265 (C. A. 4th, 1949 ).................................... 13

Blank v. Bitker, 135 F. 2d 962 (C. A. 7th, 1943) ....................................... 15

Bourdien v. Pacific Western Oil Company, 299 U. S. 65 ............................ 14

Daggs v. Klein, 169 F. 2d 174 (C. A. 9th, 1948) ......... ................................. 13

Federal Trade Commission v. Winsted Hosiery Co., 258 U. S. 483 ......... 7

Franklin Township in Somerset County v. Tugwell, 85 F. (2d) 208 (C. A.

D. C. 1936) ............................................................................................... 11

Frothingham v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 447 ............................................................ 8

Fulton Iron Company v. Larson, 171 F. 2d 994 (C. A. D. C. 1946) ......... 14

Howard v. United States ex rel Alexander, 126 F. 2d 667 (C. A. 10th,

1942) 15

Jacobs v. Office of Housing Expediter, 176 F. 2d 338 (C. A. 7th, 1949) 13

Joint Anti Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath, 341 U. S. 123 ................. 7

Massachusetts v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 447 .......................................................... 8

Money v. Wallin, 186 F. 2d 411 (C. A. 3rd, 1951) ....................................... 13

National Licorice Company v. National Labor Relations Board, 309

U. S. 350 ................................................................................................. 12,13

Payne v. Fite, 184 F. 2d 977 (C. A. 5th, 1950) ............................................. 13

Rorick v. Brd of Comm’rs, Everglades Drainage District, 27 F. 2d 377,

381 (N. D. Fla. 1928) 11

Smart v. Woods, 184 F. 2d 714 (C. A. 6th, 1950) ....................................... 13

State of Washington v. United States, 87 F. 2d 421 (C. A. 9th, 1936) . . . . 14

11

STATUTES

PAGE

Act of Sept. 1, 1937, c. 896, 50 Stat. 888, as amended by Act of

July 15, 1949, c. 338, Title III, 63 Stat. 442, Title 42, U. S. C.,

Sections 1409 ......................................................................................

1410(a) ........................................................................................

1410(c) .........................................................................................

1410(g) ........................................................................................ 7,10

1411(a) ........................................................................................ 7

1413 .............................................................................................. 7

1415(7) (c) ................................................................................. 7

1421(a)(1) ................................................................................. 7

Act of April 9, 1866, c. 31, Sec. 1, 14 Stat. 27, Title 8, U. S. C. § 42 ......... 10

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Restatement of Torts, Section 876 .................................................................. 7-8

Memorandum of Jan. 12, 1954 of Secretary of Defense Charles E.

Wilson ....................................................................................................... 11

M

V

J V

I

llmtrii (tart nf Appeal#

For the D istrict of C olum bia C ircuit

No. 11,865

------------------o-------------------

P r in c e F . H ey w a r d , E r s a l in e S m a l l , W il l ia m M it c h e l l ,

W il l ia m G o l d e n , M ik e M a u s t ip h e r , W il l is H o l m e s ,

A l o n z o S t e r l in g , M a r t h a S in g l e t o n , I r e n e C h is h o l m ,

J o h n F u l l e r , B e n j a m i n E . S im m o n s , J a m e s Y o u n g ,

O l a B l a k e ,

Appellants,

v.

P u b l ic H o u s in g A d m in is t r a t io n , body corporate; J o h n

T . E g a n , Commissioner, Public Housing Administra

tion,

Appellees.

A p p e a l f r o m t h e U n it e d S t a t e s D is t r ic t C o u r t fo r t h e

D is t r ic t o f C o l u m b ia

------- ------------o-------------------

REPLY BRIEF FO R A PPELLA N TS

1

I. This A ction Is Not P rem ature By A ppellees’

O w n A dm ission.

Appellees in their motion for summary judgment in

the court below said in Paragraph 5 that: “ This project

will not be ready for occupancy until approximately March,

1954” (Joint Appendix 16). Therefore, Appellees’ argu

ment in their brief in this court that the order below dis

missing the complaint should be affirmed on the ground

that the action is premature is no longer valid by Appellees ’

own statement and admission with respect to completion

of Fred Wessels Homes, the project under construction

at the time this complaint was filed. The court below, upon

hearing the Appellees’ motion for summary judgment,

refused to sustain Appellees’ contention that the action

is premature (Joint Appendix 63).

II. T here Is A Justic iab le C ontrovery Between

These A ppellees A nd A ppellants.

Appellees’ argument that there is no justiciable case

or controversy rests primarily on the contention that it

is the local authority which leases the housing units and

it alone determined that this project will be occupied by

white families. Thus, the basis of this argument is that

Appellees have done no act which can be considered the

legal cause of Appellants ’ injury. This contention, Appel

lants submit, is wholly specious. In Appellants’ brief,

the nature and extent of the Public Housing Administra

tion’s involvement in the local program has been related

in detail (Appellants’ brief pp. 8-18). The bulk of this

factual material thus need not be reiterated here. The

inescapable conclusion, however, is that the Public Housing

Administration’s involvement is so extensive and com

plete in the planning, construction and operation of each

project that it cannot be seriously contended that this low-

2

rent public housing program is a local undertaking devoid

of any major federal control.

Of particularly crucial importance is the special role

played by the Public Housing Administration with respect

to local racial policies. In Appellants’ brief (p. 14) there

is set forth the Public Housing Administration’s so-called

“ racial equity formula” and the more recent policy direc

tive promulgated in a release issued January 17, 1953

(HHFA-OA No. 470) (pp. 14-16). The significance of the

Appellees’ racial equity formula and related policy is

candidly admitted in the affidavit of Mr. John T. Egan,

the Commissioner of the Public Housing Administration,

which is attached to Appellees’ motion for summary judg

ment. He states that:

“ (b) The regulations of the Public Housing

Administration further require that programs for

the development of low-rent housing must reflect

equitable provision for eligible families of all races

determined on the approximate volume and urgency

of their respective needs for such housing (Low-

Bent Housing Manual, Section 102.1, a copy of which

is attached to this affidavit as Exhibit 2) ” (emphasis

supplied) (Joint Appendix p. 20).

The nature of the role played by the Public Housing-

Administration with respect to local racial policies can

be pinpointed in the following manner. If a local authority

such as the Savannah Housing Authority is interested in

securing approval for a development program, it has two

alternatives. First, it can agree to make all low-rent

public housing projects to be constructed by it available

for occupancy to all racial groups without discrimination

or segregation of any kind.

However, if such a plan is unacceptable to the local

authority, it has a second alternative. It can agree to pro

3

vide a specified number of units for the occupancy of white

families and a specified number for the occupancy of Negro

families, the families to be housed on a racially segregated

basis. If the percentage for white families and the per

centage for Negro families meet the standards for achiev

ing racial equity determined by the Public Housing Admin

istration, then the Development Program is approved in so

far as this aspect is concerned. (See affidavit of John T.

Egan, Joint Appendix pp. 23-24). In the instant case, the

percentages approved by the Public Housing Administra

tion were 36.7% of the dwelling units for whites and 63.3%

of the units for Negroes. This overall percentage allocation

must be approved by the Public Housing Administration.

And once it was approved, it became a part of the con

tractual relationship between the Public Housing Adminis

tration and the Savannah Housing Authority.

There is, of course, logically a third possible alterna

tive. The local authority could conceivably have complete

freedom of choice. But a local housing authority has no

such freedom, and it is the determination of the Public

Housing Administration which deprives local authorities

of such freedom.

In the instant case, the Savannah Housing Authority

was obviously unwilling to agree to the first alternative

noted above—i.e., open occupancy. Therefore, it was

required by the Public Housing Administration to agree

to the second alternative plan, i.e., segregated housing,

with a specified percentage allocation to white families and

to Negro families. For short-hand reference, we shall term

the second plan the “ segregation-quota” plan. Once the

Savannah Housing Authority agreed to the “ segregation-

quota” plan and once the number of units for whites and

the number of units for Negroes was agreed upon and thus

made a part of the contractual relationship between the

4

parties, the Savannah Authority had no contractual right to

deviate. The Savannah Authority obviously has no right to

lease to white persons all units in all projects including

those units designated exclusively for Negroes. Similarly,

it has no right to lease all units in all projects to Negroes.

In other words, the Savannah Authority has no right to

deviate in any way from the quota system agreed upon,

i.e., 36.7% of the dwelling units for whites and 63.3% of

the dwelling units for Negroes. Thus, the statement in

Appellees’ brief that they would have no objection if the

local authority were to decide to admit Negro occupants

(p. 13) is a flagrant distortion. If the Savannah Authority

decided to integrate projects designated exclusively for

whites, while leasing the projects designated exclusively

for Negroes in conformance with the overall plan, then

Negroes in Savannah would be securing a disproportionate

number of units in violation of the Public Housing Adminis

tration’s racial equity formula. Such action by the Savan

nah Authority would thus clearly be in violation of the

contractual relationship between it and the Public Housing

Administration.

Plaintiffs are individual Negroes who claim that on the

basis of their qualifications (and with the factor of race

excluded) that they are entitled to be admitted to the Fred

Wessels Homes. The Savannah Authority cannot admit

these plaintiffs, for its contractual relationship with the

Public Housing Administration requires it to allocate only

63.3% units to Negro families and 36.7% to white families.

For the Savannah Authority to admit Negroes to the Fred

Wessels Homes would thus destroy the elaborate quota

system set up and as required by the Public Jlousing

Administration. The Savannah Authority has no contrac

tual right to do this.

A hypothetical situation may help clarify the above

analysis. Assume that a local housing authority chooses

the “ segregation-quota” plan of development. Assume

b

further that the local authority agrees with the Public

Housing Administration’s determination that an alloca

tion of 200 units for whites and 200 units for Negroes will

provide racial equity. This agreement of course becomes

a part of the contractual relationship between the local

authority and the Public Housing Administration. Assume

further that the Negro project is completed first and that

200 Negro families are given occupancy. If 50 additional

Negroes were to apply to the local housing authority and

were able to prove that they were more qualified and had

a higher priority than 50 white families who were scheduled

to be given occupancy in the 200 unit white project, could

the local housing authority admit these 50 Negro families

along with 150 white families to the project originally

designated for whites? Appellants submit that the local

authority would have no contractual right to admit these 50

Negroes because such an act on the part of the local au

thority would be in violation of the racial equity formula

agreed upon by the local authority and required by the

Public Housing Administration. Thus, it is the Public

Housing Administration which determines whether any

given Negro family can be admitted to Fred Wessels Homes.

It is these Appellees who have made the determination to

limit Fred Wessels Homes to occupancy by white families

to the injury of these Appellants.

It is Appellants’ position that Appellees here do con

siderably more than supply funds to the local authority.

On the contrary, the Appellees exercise complete super

visory control and participate in every material determi

nation. However, even if this court should conclude that

the role played by the Appellees is limited to the expendi

ture of funds, Appellants contend that such expenditures

here are unlawful and violative of their rights and that

Appellants, therefore, have a justiciable case or contro

versy.

6

The equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment prohibits the Savannah Housing Authority, a state

agency, from leasing housing units on the basis of race or

color. See cases cited in Appellants’ brief, pages 22-30.

The expenditures by the Public Housing Administration

constitute more than minor assistance—the expenditure of

federal funds makes the illegal project possible.1 By these

1 Federal financial involvement in a project may precede the

actual construction of the project and may continue for as long a

period as sixty years after its construction.

The federal agency administering the basic act is authorized by

it to make loans to local public housing agencies. These loans may

be made for the purpose of assisting the local agency in defraying

the costs involved in developing, acquiring or administering a project.

PHA may therefore commence involving the federal government

financially by making a preliminary loan to the local agency in order

that it may have the funds with which to proceed to make plans for

the proposed project and to conduct any necessary surveys in connec

tion therewith. PHA may then make a further loan which enables

the local agency to meet the cost of construction and to repay the

preliminary loans. It may even loan money to pay any costs in

administering the project.

PHA is, in addition, authorized by the basic enactment to specify

in a contract with a local agency that it will contribute a fixed sum

annually over a predetermined period of years “to assist in achieving

and maintaining the low-rent character” of the project. PHA may

therefore commit the federal government to financially subsidizing

a project, after it is constructed, for a period as long as sixty years.

From this subsidy the local agency may presumably repay any monies

loaned to it by the federal government for construction of the project

or in connection with its administration.

The annual contribution made by the federal agency is one of

two methods provided whereby the federal government may subsidize

a public housing project. The alternate method of effecting a federal

subsidy provided for in the act provides for a capital grant to a local

agency in connection with the development or acquisition of a project

which will thereby enable it to maintain the low rent character of the

project. PHA may make a capital grant in any amount which it

considers necessary to assure the low rent character of the project.

The PHA may, therefore, make a capital grant to a local agency

which will pay the entire cost of development or acquisition of a

project.

7

expenditures, the Public Housing Administration know

ingly supplies the state agency with the means whereby

the latter can effectively discriminate in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment. In so doing, Appellees flagrantly

violate Appellants’ rights and the public policy of the

United States.

Further, there is a firm basis in the common law to

support our contention that a justiciable case or contro

versy exists. See Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v.

McGrath, 341 U. S. 123, 159. For example, it has long been

the law of unfair competition that one who furnishes

another with the means of consummating a fraud is also

guilty of unfair competition. See, Federal Trade Commis

sion v. Winsted Hosiery Co., 258 U. S. 483, 494. Section

876 of the Restatement of Torts expresses general prin

ciples which are firmly imbedded in the common law.

In addition to this financial assistance which may be given to a

local agency, PHA is further authorized to involve the federal gov

ernment financially in the event of any foreclosure by any party on,

or in the event of any sale of, any project in which the federal gov

ernment has a financial interest. In the event of foreclosure, PHA

may bid for and purchase such a project, or it may acquire and take

possession of any project which it previously owned or in connection

with which it has made a loan, annual contribution or capital grant.

In such case it may complete the project, administer the project, pay

the principal of and the interest on any obligation issued in connec

tion with the project, thus further involving the federal government

financially.

Finally, in the event of any substantial contractual default on the

part of the local agency, PHA may involve the federal government to

the extent of taking title or possession of a project as then consti

tuted and must involve the federal government further financially

by continuing to make annual contributions available to such project

to pay the principal and interest on any obligation for which these

contributions have been pledged as security.

It is, therefore, quite possible for the financial involvement of the

federal government to constitute at some point the entire financial

investment in a project. [Title 42 U. S. C. Secs. 1409, 1410, 1411,

1413, 1415, 1421.]

8

“ Section 876 Persons Acting In Concert

For harm resulting* to a third person from the tor

tious conduct of another, a person is liable if he * # *

“ (b) knows that the other’s conduct consti

tutes a breach of duty and gives substantial

assistance or encouragement to the other so to

conduct himself, or

“ (c) gives substantial assistance to the other

in accomplishing* a tortious result and his own

conduct, separately considered, constitutes a

breach of duty to the third person.”

The above principles can be used by analogy to demon

strate that even if the injury which Appellants receive

originates from the unlawful conduct of the Savannah

Housing Authority, Appellees’ participation nevertheless

can be considered to be a legal cause of Appellants ’ injury.

Massachusetts v. Mellon and Frothingham v. Mellon,

262 U. S. 447, upon which Appellees rely in Point Y of their

brief, present merely one aspect of the general problem of

justiciable issue. The Frothingham ease, which is the one

more pertinent here, decided merely that federal taxpayers

have too remote an interest in the expenditure of fed

eral funds to be deemed legally injured by such expendi

ture. Appellants here do not sue as taxpayers. On the

contrary, Appellants sue as low-income families for whose

specific benefit the federal government’s low rent housing

program was enacted and as displaced families who, by

express statutory provisions, must be granted preference

for admission to Fred Wessels Homes. Hence, the doc

trine of Massachusetts v. Mellon is not applicable and the

question of justiciable case or controversy must be deter

mined on the basis of principles already discussed.

9

III. A ppellees H ave In ju red A ppellan ts By D eny

ing Them The S tatu to ry Preference For Admission.

In the preceding section of this brief Appellants have

demonstrated that it is Appellees who are responsible for

the Fred Wessels Homes racial policy. Since it is Apelllees

who require that Fred Wessels Homes be limited to white

occupancy, it is Appellees who are denying- displaced Negro

families their statutory preference for admission.

Congress has imposed upon Appellees the duty to see to

it that every contract for annual contributions contains a

clause requiring the local authority to extend preference

to displaced families for admission to any low-rent housing

project initiated after January 1, 1947. Appellees’ conten

tion that their sole duty is to place the preference provision

in each annual contributions contract is weak and uncon

vincing. Certainly Congress intended to give those for

whom it intended a preference a more substantial right than

that. It must necessarily have been the intention of Con

gress that the federal agency administering the Act should

have the duty to enforce this provision. Appellees ’ failure

to require the Savannah Authority to grant Appellants the

preference to which they are entitled is the proximate legal

cause of Appellants ’ injury.

If the statutory preference has any meaning, then cer

tainly the holder of the preference has the right to receive

occupancy as soon as it is available, consistent with the

rights of others with a higher priority. It is indeed a rare

species of preference which grants the holder occupancy in

1955, while others with no preference obtain occupancy

in 1954.

10

IV. The Savannah H ousing A uthority Is Not An

Indispensable Party .

Appellees in their motion for summary judgment urged

that the Savannah Housing Authority is an indispensable

party. However, the court below, upon hearing* Appellees ’

motion, refused to sustain this contention (Joint Appendix

63).

Appellees on this appeal renew this contention, urging:

that the lower court’s dismissal of the complaint be affirmed,

on this ground. Appellees here contend that the Savannah

Authority is indispensable for two reasons: 1) that it is

the Savannah Authority and not these Appellees which is

proposing the occupancy policy which Appellants challenge,

and 2) that Appellants seek to invalidate Savannah’s con

tractual rights in this action.

Appellants, in section II of this brief, have demonstrated

that it is these Appellees by their own admission in Mr.

Egan’s affidavit who required, proposed, and approved the

occupancy policy of which Appellants complain. Appellees ’

first reason for urging that the Savannah Housing Author

ity is an indispensable party is therefore without substance.

The Savannah Housing Authority has a contractual

right to receive from Appellees federal funds for the con

struction and operation of Fred Wessels Homes. But

Savannah’s contractual right to receive such funds is obvi

ously contingent upon its and Appellees’ compliance with

the Housing Act of 1937, as amended, specifically section

1410(g) of Title 42, United States Code. This right is

further conditioned upon compliance with the Fifth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States by Appellees,

and upon compliance by both Appellees and the Savannah

Authority with the provisions of Title 8 Section 42 of the

United States Code. Appellees, as federal administrative

officials, are subject to federal constitutional and statutory

11

proscriptions on their right to contract. They are under a

duty to administer the federal program involved here in

conformity with the Constitution, laws and public policy of

the United States.2 The Savannah Housing Authority is

likewise subject to federal constitutional and statutory pro

scriptions on its right to contract. Neither these Appellees

nor the Savannah Authority can lawfully contract to violate

rights secured to Appellants by the Constitution and laws

of the United States or in violation of the public policy of

the United States.

Appellants in their brief have demonstrated that the law

is clearly established that the Savannah Authority may not.

under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, enforce a policy of racial segregation in public hous

ing. Since the Savannah Authority does not have the right

to enforce racial segregation in public housing, it cannot

have a right to receive federal funds from Appellees for

the operation of a project from which Appellants will be

excluded and denied admission solely because of race and:

color under the “ segregation-quota” plan. Therefore, no

legally protected right of the Savannah Authority could be

adversely affected by a judgment for the Appellants in this

action. Thus, the Savannah Authority is not an indispen

sable party. Franklin Township in Somerset County,

N. J. v. Tugwell, 85 F. 2d 208 (C. A. D. C. 1936); Rorick v.

Brd. of Comm’rs, Everglades Drainage District (N. D. Fla.,

1928), 27 F. 2d 377, 381.

2 The most recent evidence of the public policy of the United States

government is contained in a Memorandum issued January 12, 1954 by

Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson barring racial segregation in

schools operated by local public agencies on military posts. In Secre

tary Wilson’s Order the policy of the United States government in

cases involving the use of federal funds is made clear and unequiv

ocal. The public policy issue in the instant case is identical with the

public policy issue in the Wilson Order.

12

In addition, a judgment for Appellants, as a practical

matter, will not result in any real injury to the Savannah

Authority, since despite a judgment for the Appellants, it

can nevertheless receive the money contracted for by simply

adopting an open occupancy policy. In other words, the

money contracted for can always be obtained by Savannah

by complying with the law.

The public policy issue here asserted by Appellants

supercedes any contract rights of the Savannah Housing

Authority alleged to be at stake in this action. In fact, even

in purely private litigation, where the rights asserted arise

independently of any contract which the adverse party may

have made with another, not a party to the suit, many courts

have allowed the suit to be maintained if the absent party

to the contract could not be joined. See, National Licorice

Company v. National Labor Relations Board, 309 U. S. 350,

363-364, and cases cited therein.

If the Housing Authority of Savannah is an indispen

sable party to the instant case, it follows that Appellees

here would be indispensable to a suit in Savannah against

the Savannah Authority because Appellees’ contractual

rights would be equally affected in such an action. The

Savannah Authority, as Appellees point out, may not be

joined in this action because it is outside the jurisdiction

of the court below. Similarly, Appellees could not be joined

in an action in Savannah since they would be outside the'

jurisdiction of both the state and federal courts in Savannah.

The suggestion, therefore, that Savannah is an indispen

sable party, if sustained, would render these Appellants

remediless in a case where federal constitutional and statu

tory rights are sought to be secured and where vindication

of the public policy of the United States is sought. Where

the public interest or public policy is involved and parties

deemed proper or even necessary cannot be brought before

the court, a federal court should not refuse to proceed to

13

judgment without such parties. National Licorice Company

v. National Labor Relations Board, 309 U. 8. 350.

Balter v. I ekes, 89 F. 2d 856 (C. A. D. C. 1937), relied

on by Appellees in urging lack of indispensable party,

involved three factors not present in the instant case. First,

in that case, the defendant federal official held the property

of the City of St. Louis, the party not before the court. In

ruling that St. Louis was an indispensable party, the court

was simply following the settled line of decisions that where

there is property to be disposed of the court cannot do so in

the absence of those parties whose interest in such property

will be determined by its decree. In this case Appellees

hold no property of the local authority.

The second factor is that the plaintiffs sought to annul

the contract between the federal officers and St. Louis.

Here Appellants do not seek, as Appellees contend, to

have the contract between them and Savannah Housing

Authority annulled, per se. They seek to have the perform

ance of the contract conditioned on securing their constitu

tional and statutory rights and seek to have the contract

carried out in accordance with the public policy of the

United States.

The third factor is that the court was of the opinion that

the plaintiffs were “ third parties, asserting a somewhat

questionable interest. ’ ’ Balter v. lekes, supra, at 359. The

plaintiffs in that case failed to show legal injury inflicted

by either the federal officials or the City of St. Louis. The

Balter case therefore was one in which there was no real

controversy between the plaintiffs and defendants.

Appellees cite Money v. Wallin, 186 F. 2d 411 (C. A. 3rd,

1951); Payne v. Fite, 184 F. 2d 977 (C. A. 5th, 1950); Daggs

v. Klein, 169 F. 2d 174 (C. A. 9th, 1948); Smart v. Woods,

184 F. 2d 714 (C. A. 6th, 1950); Berlinsky v. Wood, 178

F. 2d 265 (C. A. 4th, 1949); Jacobs v. Office of Housing

14

Expeditor, 176 F. 2d 338 (C. A. 7th, 1949), and Ainsworth v.

Barn Ballroom Company, 157 F. 2d 97 (C. A. 4th, 1946),

all of which involved the question whether the defendants ’

superior officer was an indispensable party. Since this

question is not involved in this action, these cases are clearly

inapplicable.

Appellees also rely on Fulton Iron Company v. Larson,

171 F. 2d 994 (C. A. D. C. 1948), and State of Washington v.

United States, 87 F. 2d 421 (C. A. 9th, 1936). In the Larson

case the real basis of the decision was that the plaintiff was

a mere member of the public who had no right which had

been violated by the federal officer. An alternative basis of

the decision was that the case was in fact a suit against the

United States. In State of Washington v. United States,

supra, the situation there was quite different from the one

presented in the instant case. There suit was brought by

the United States against two private companies to obtain

title and to be adjudged owner of certain lands between the

States of Washington and Oregon. The private companies

were the lessees of the States. The States had been denied

the right to intervene and on appeal the court held that the

States were indispensable parties to such an action. In the

instant case, title to property is not in dispute.

It is only where a decree would do violence to equity

and good conscience that a court should refuse to proceed

to judgment without an absent party. Barrow v. Shields,

17 How. (U. S.) 130, 139. In Bourdien v. Pacific Western

Oil Company, 299 U. S. 65, 70-71, the Court said:

‘ ‘ The rule is that if the merits of the cause may be

determined without prejudice to the rights of neces

sary parties, absent and beyond the jurisdiction of

the court, it will be done; and a court of equity will

strain hard to reach that result. (Citing cases.)

“ We refer to the rule established by these authori

ties because it illustrates the diligence with which

15

courts of equity will seek a way to adjudicate the

merits of a case in the absence of interested parties

that cannot be brought in. ’ ’

It should be noted, further, that if, as Appellees contend,

the Savannah Housing Authority has such an interest in

this case that it ought to be brought in, there is nothing

which prevents the said Authority from voluntarily appear

ing in this action. Matters of jurisdiction and venue may

always be waived. See, Howard v. United States ex red.

Alexander, 126 F. 2d 667 (C. A. 10th, 1942); and Blank v.

Bitker, 135 F. 2d 962 (C. A. 7th, 1942).

Appellants therefore urge that the lower court be sus

tained in its view that the Savannah Authority is not an

indispensable party.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, Appellants urge that the judg

ment of the court below be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

F r a n k A. D il w o r t h , I I I ,

458)/2 West Broad Street,

Savannah, Georgia;

T httrgood M a r s h a l l ,

C o n s t a n c e B a k e r M o t l e y ,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, N. Y.;

F r a n k D . R e e v e s ,

2000 Ninth Street, N. W.,

Washington 1, D . O.;

Attorneys for Appellants.

D avid E. P in s k y ,

of Counsel.