Adams v. Bell Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

August 24, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Adams v. Bell Court Opinion, 1982. 6cd513d2-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5ef207a4-4276-426b-a2e4-1f5da3c95159/adams-v-bell-court-opinion. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

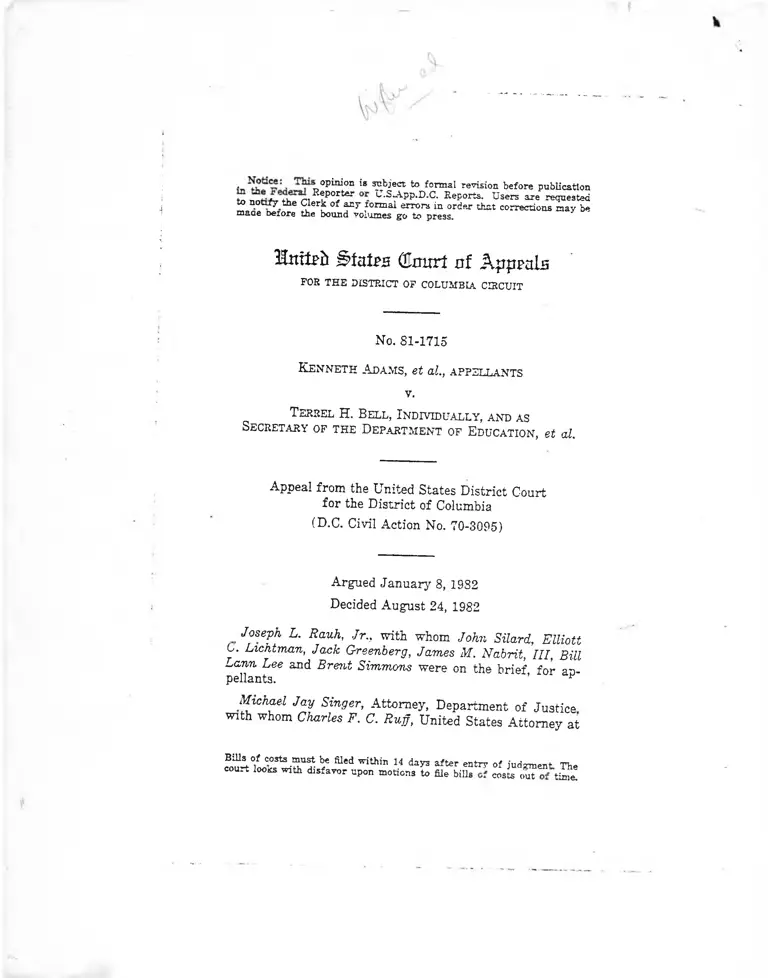

. opinion is subject to formal revision before publication

Et P°5ter '^ -A p p .D .C . Reports. Users axe requested

to n otify the Clerk of any iorm al errors in order that corrections m ay be

Q2&Q6 Dcxors tiiG bound volumes q o to press.

Hnttpb Elates (Cmrrt of Appeals

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA C 3C UIT

No. 81-1715

Kenneth Adams, et al., appellants

v.

Terrel H. Bell, Individually, and as

Secretary of the Department of Education, et al.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

(D.C. Civil Action No. 70-3095)

Argued January 8, 1982

Decided August 24, 1982

Joseph L. Rauh, Jr., with whom John Silard, Elliott

C. Lichtman, Jack Greenberg, James M. Nabrit, III, Bill

Lann Lee and Brent Simmons were on the brief for ap

pellants. ’ y

Michael Jay Singer, Attorney, Department of Justice

with whom Charles F. C. Ruff, United States Attorney at

Bills of costs m ust be filed w ithin 14 days a f te r en try of iudvm ent T t,.

court loess w ith d isfavor upon motions to file b ill, cosL <£?“ t S £

2

the time the brief was filed, and William Ranter, Attor

ney, Department of Justice, were on the brief, for ap*

pellees.

Before: Wright and Tamm , Circuit Judges, and

Markey," Chief Judge, United States Court of Customs

and Patent Appeals.

Opinion for the Court filed by Chief Judge Markey.

Dissenting opinion filed by Circuit Judge Wright.

Markey, Chief Judge: Appeal from the district

court's denial of motions for a temporary restraining

order and preliminary injunction to prevent the Depart

ment of Education (DE) from entering a settlement

of its Title VI administrative enforcement proceeding

against the state university system of North Carolina.

We dismiss the appeal.

Background

Beginning in 1970, Adams has brought a series of suits

in this circuit, seeking to force the Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare (HEW ), now the Department of

Education (D E),1 to carry out its statutory duty under

Title VI.a In Adams v. Richardson, 351 F. Supp. 636

♦ Sitting by designation pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 293 (a).

1 Responsibility for the matters involved has been trans

ferred to the Department of Education under the terms of

the Department of Education Organization Act, Pub. L. No.

96-88 (Oct. 17, 1979), 93 Stat. 669-695. See 20 U.S.C. § 3401

et seq. (Supp. Ill, 1979).

2 Title VI concerns discrimination in federally assisted pro

grams. The basic prohibition established under that title is

set forth at 42 U.S.C. § 2000d which provides:

No person in the United States shall, on the ground of

race, color, or national origin, be excluded from partici

pation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to

discrimination under any program or activity receiving

Federal financial assistance.

3

(D.D.C. 1972), Adams v. Richardson, 356 F. Supp. 92

(D.D.C. 1973), Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159

(D.C. Cir. 1973), and Adams v. Califano, 430 F. Supp.

118, the courts of this circuit issued orders requiring

HEW /DE to establish criteria, to accept or reject state

plans for desegregation of their higher education systems

in light of the criteria, and to initiate enforcement pro

ceedings when voluntary compliance with Title VI was

not forthcoming.

North Carolina’s 1974 desegregation plan, along with

those of other states, was accepted by HEW, but HEW

was ordered to revoke its acceptance in Adams v. Cali

fano, 480 F . Supp. at 121. Concluding that compliance

with Title VI was wanting in North Carolina, HEW

served that state in March, 1979 with a Notice of Op

portunity for Hearing in accordance with 42 U.S.C

§ 2000d-l.»

North Carolina then filed suit against HEW in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

North Carolina, challenging HEW’s effort to enforce

Title VI, and seeking to enjoin the hearing and HEW’s

deferral of federal aid during its progress. HEW sought

to transfer the action to the District of Columbia under

28 U.S.C. § 1404(a) (1976).

* Section 2000d-l provides in pertinent part:

Each Federal department and agency which is empowered

to extend Federal financial assistance to any program or

activity . . . is authorized and directed to effectuate the

provisions of section 2000d. . . . Compliance with any

requirement adopted pursuant to this section may be

effected (1) by the termination of or refusal to grant or

to continue assistance under such program or activity to

any recipient as to whom there has been an express find

ing on the record, after opportunity for hearing, of a

failure to comply roith such requirement . . . . or (2) by

any other means authorized by law: Provided, however,

That no such action shall be taken until the department

or agency . . . has determined thnt compliance cannot be

secured by voluntary means. (Emphasis added.)

4

The North Carolina district court, per Judge Dupree,

denied HEW’s motion for a change of venue and the

State’s motion to enjoin the Title YI administrative hear

ing, enjoined the deferral of aid during the hearing, re

tained jurisdiction over the action, and stayed judicial

proceedings pending completion of the hearing. North

Carolina v. Department of Health, Education and Wel

fare, 480 F. Supp. 929 (E.D.N.C. 1979).'1

In July 1980, a formal hearing in which Adams was

allowed a limited right to intervene, In the Matter of

the State of North Carolina, E.D. Docket No. 79-VI-l

and HUD Docket No. 79-4 (Order of August 13, 1979,

Permitting Adams Plaintiffs to Intervene), commenced

at DE before an administrative law judge. Over a period

of nine months the parties presented their affirmative

cases, creating a record of 15,000 pages and 500 exhibits.

Part of North Carolina’s case rested on constitutional

challenges. On June 22, 1981, DE notified Adams that a

settlement between DE and North Carolina had been pro

posed which, if accepted by Secretary of Education Bell,

would be filed in the North Carolina district court in the

form of a consent decree.

Three days later, on June 25, 1981, Adams moved in

the District of Columbia district court, before Judge

Pratt, for a temporary restraining order and preliminary

injunction against DE’s entering the proposed settlement.

Ruling from the bench, Judge P ra tt denied the motion.

On the following day, Adams filed this appeal.®

* Adams applied to the district court for the District of

Columbia for a mandatory injunction requiring the deferral

of aid enjoined by Judge Dupree. Noting the "basic principles

of comity” and the need to avoid “irreconcilable judicial man

dates", Judge Pratt denied the request. Adams V. Harris, No.

70-3095, slip. op. at 3 (D.D.C., mem. opinion Oct. 18, 1979).

® On June 29, 1981, Adams fded in this court an Emergency

Motion for Injunction Pending Appeal. This Court denied the

5

DE joined with North Carolina in presenting the pro

posed consent decree to the Eastern District of North

Carolina district court for approval. Judge Dupree sched

uled a hearing for July 13, 1981, giving Adams notice

and opportunity to appear as amicus curiae. Judge

Dupree noted that Adams never sought to intervene as

a party in the action before him. DE and North Carolina

filed memoranda in support of the consent decree, and

Adams filed an opposition. The parties submitted to the

court the entire record of the administrative hearing.

On July 17, 1981, "unpersuaded that the settlement

reached is in any way violative of either the [D.C.J dis

trict court or circuit court orders” discussed above, and

finding that “ [t] he plan which the decree embodies com

plies substantially with the criteria promulgated by HEW

in 1977,” Judge Dupree approved the consent decree.

North Carolina v. Department of Education, No. 79-217-

CIV-5 (E.D.N.C., mem. dec. July 17, 1981). In accord

ance with the terms of the consent decree, the North Car

olina district court will “retain jurisdiction over the case

until December 31, 1988, to monitor continued compliance

by . . . [North Carolina] with Title VI and the four

teenth amendment.” ®

motion by order of June 30, 1981, and later denied Adams’

motions for an expedited appeal.

8 A provision of the consent decree obligates the govern

ment to dismiss the administrative enforcement proceeding

against North Carolina without prejudice. On July 27, 1981,

DE’r General Counsel moved the administrative law judge to

dismiss the proceeding, and Adams opposed the dismissal.

The administrative law judge certified the question of dis

missal to DE’s Reviewing Authority for a ruling. In the Mat

ter of the State of North Carolina, E.D. Docket No. 79-VI-l

and HUD Docket 79-4 (Order of August 17, 1981, Certifying

Motion to Dismiss to the Reviewing Authority). The motion

is pending, so far as the present record reflects.

6

Opinion

Though not argued by the parties, the threshold issue

on this appeal is whether the case is moot.7 Adams’ mo

tion requested relief in the form of an order prohibiting

DE’s entry into a settlement to be submitted to Judge

Dupree in the form of consent decree. The action sought

to be prohibited has now been consummated, State of

North Carolina V. Department of Education, No. 79-217-

CIV-5 (E.D.N.C., July 17, 1981), rendering the case

moot. Mills v. Green, 159 U.S. 651 (1895); Jones v.

Montague, 194 U.S. 147 (1904); Oil Workers Unions v.

Missouri, 361 U.S. 363 (1960); Hall V. Beals, 396 U.S.

45 (1969)."

7 The mootness concept has been subjected to erosion and

confusion. See Note, Mootness on Appeal in the Supreme

Court, 83 Harv. L. Rev. 1672 (1970). That courts of equity

may grant relief not prayed for is established. Fed. R. Civ. P.

54(c). A basis for unrequested declaratory relief can be

visualized in virtually every case, making it possible for state

and federal declaratory judgment acts to virtually swallow

the mootness concept. Whatever may be the appropriate view

respecting a sua sponte grant of a declaratory judgment af

fecting tho rights and duties of the parties in a particular

case, tho day has not yet come when courts of one circuit

should issue declaratory judgments evaluating actions taken

by courts of another circuit.

* Mootness precluding justiciability, matters such as the

correspondence of the settlement/consent decree with the

criteria, the status of desegregation in the higher education

system of North Carolina, and Judge Pratt’s denial of Adams'

motion, are matters not before us. Our decision in this case

casts no reflection on the substance of any criteria, or on any

earlier court decision requiring HEW/DE to adopt and em

ploy some criteria in its administrative evaluation of desegre

gation plans submitted by the states. Indeed, such court deci

sions have been a major factor in stimulating the agency to

fulfill its statutory obligations under Title VI. As important

ns such matters may be, they are not involved in any determi

nation of whether a district court of this circuit may properly

enjoin DE’s conduct in an enforcement proceeding in a court

of another circuit, nor are such matters involved in this court’s

recognition of the fact of mootness on this appeal.

7

For this court to order revocation of DE’s settlement

of the North Carolina enforcement litigation would run

counter to the court-approved consent decree of a court of

another circuit, would be contrary to the principles of

comity, and would erect an unseemly and irreconcilable

conflict between federal courts.

Nor is there another form of effectual relief which this

court might grant. The case before us relates to North

Carolina, which is not a party and not in this case subject

to this court’s jurisdiction.8 A declaratory judgment on

the extent to which DE may or may not have met its

statutory obligations in submitting the consent decree to

Judge Dupree, for example, would be merely an advisory

opinion, having no effect on the parties or the situation

in the North Carolina litigation. It would, moreover, en

tail an inappropriate review of, and an advisory pro

nouncement on, Judge Dupree’s action in approving the

settlement and decree.10

8 Adams says the criteria "are of national significance” and

that it is “highly appropriate for courts in Washington, D.C.

to rule upon the necessity for, and the propriety of, these

desegregation criteria applicable to many states.” That action

would be highly convenient. It would not be highly appro

priate in this case under the rules governing our judicial

system. Moreover, this court has rejected the notion that it

is alone suited to review issues of national importance. See

Starnes V. McGuire, 512 F.2d 918, 928 (D.C. Cir. 1974) (en

banc). This court is not a national court of appeals, nor a

judicial panel on multi-district litigation. See 28 U.S.C. § 1407

(1976). It plays not the role of the Supreme Court. Its loca

tion renders it neither more nor less appropriate that it rule

on matters of "national significance.”

10 Whether DE should in general be declared to be disre

garding the criteria may be considered in connection with

Adams’ Motion for Further Relief pending in the district

court. Adams V. Bell, Civ. Action No. 70-3095 (D.D.C.), copy

filed with this court on May 18, 1982. In that Motion, Adams

includes a 35-page statistical compilation purporting to show

disregard of the criteria by DE in 11 states, (not including

8

Accordingly, the case is moot and the appeal is dis

missed.

Appeal Dismissed

North Carolina), and seeks an order requiring every previ

ously de jure segregated state to comply with the criteiia.

Unlike the present case, jurisdiction to determine whether a

federal agency is fulfilling its legal obligations may be impli

cated in considering the Motion for Further Relief. Consid

erations of case or controversy, private cause of action, stand

ing, ripeness, and the authority of courts in this circuit to

issue orders to the states, need not be treated here, where as

in other states, DE’s enforcement efforts are before other

courts. See, e.g., United States V. Louisiana, 527 F. Supp. 509

(E.D. La 1981) (order of three-judge court approving con

sent decree in settlement of government s Title VI desegrega

tion case). Whether DE is shirking its duty by entering par

ticular consent decrees is for tbe particular courts considering

those decrees, not this court, to consider. We are not .author

ized to substitute our views of those decrees for the views of

other courts, whose dedication to enforcement of Title VI and

constitutional rights must be presumed equal to our own.

1

Wright, Circuit Judge, dissenting: For over a decade

appellants' have patiently sought to compel the Depart

ment of Education 2 to fulfill its legal obligation * to as

sure desegregation of higher education. On at least three

occasions—twice in the.District Court of this circuit4 and

once in this court8—appellants’ efforts were vindicated.

On June 22, 1981 the Department notified appellants’

counsel that it intended to enter into an agreement ac

cepting a desegregation plan submitted by North Carolina

for its university system.8 Prior court orders had man

dated this notification.7 Appellants immediately returned

1 Plaintiffs-appellants are certain black students, citizens,

and taxpayers.

2 This action was originally brought against the Secretary

of Health, Education and Welfare (IIEW) ; responsibility for

the matters involved in this suit was transferred to the Sec

retary of Education in 1979. See 20 U.S.C. § 3401 et scq.

(Supp. IV 1980). The current defendants nre Secretary of

Education Terrel II. Bell and the director of the Department

of Education’s Office of Civil Rights.

»See Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 19G4, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000d et seq. (1976 & Supp. IV 1980).

4 Adams v. Richardson, 351 F.Supp. 636 (D. D.C. 1972)

(Memorandum Opinion), 356 F.Supp. 92 (D. D.C. 1972) (De

claratory Judgment and Injunction Order) ; Adams v. Cali-

fano, 430 F.Supp. 118 (D. D.C. 1977) (Second Supplemental

Order).

5 Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973)

(enhanc) (per curiam).

8 See Letter from Frank K. Krueger to Joseph Rauh, Juno

22, 1981, Appendix A to Points and Authorities in Support

of Issuance of a Temporary Restraining Order and Pre

liminary Injunction, Adams v. Bell, D. D.C. Civil Action No.

70-3095 (filed June 25,1981).

7 See Adams v. Califano, supra note 4, 430 F.Supp. at 121

(ordering that plaintiffs be afforded “timely access’’to revised

desegregation plans). In a subsequent order issued July 14,

1978, the court defined “timely access” as 72 hours for prior

2

to the District Court of this circuit (hereafter referred

to as the District Court) seeking to enjoin the Secretary

of Education from approving the proposed agreement.

They claimed that it conflicted with the Department’s

legal obligation that the courts of this circuit had previ

ously elaborated.

On June 25, 1981 the District Court here denied the

request for relief on the ground that it “wholly lackfed]

jurisdiction.” 8 The Secretary of Education subse

quently approved North Carolina’s desegregation plan.

On July 13, 1981 the Department and the State

of North Carolina submitted a consent decree em

bodying the plan to the District Court for the Eastern

District of North Carolina (hereafter referred to as the

North Carolina court). Within four days the North Car

olina court approved the consent decree. North Carolina

v. Dep't of Education, E.D. N.C. No. 79-217-CIV-5

(Memorandum Decision July 17, 1981). The majority,

without assessing the District Court’s conclusion as to the

jurisdiction issue, affirms because, in its opinion, the De

partment’s entrance into the consent decree in the North

Carolina court moots this lawsuit.

I respectfully dissent. This case is not moot. While I

agree that the primary issue at stake is the adequacy of

the consent decree, I believe that additional relief can

still be granted to plaintiffs. The District Court had not

only the jurisdiction to enforce its previously issued in

junction, but also the duty to determine whether the De

partment had fulfilled its legal obligation. The Secre

tary's approval of the consent agreement ignored the ear

lier judgment of the District Court; in my opinion, only

review and comment upon any new, amended, or supplemental

desegregation plan.

" Transcript of June 25, 1981 Hearing at 25 (Finding of the

Court), Appendix of Plaintiffs-Appellants (App.) 80.

3

that court—the rendering court—has the authority to de

termine whether the Department has complied with its

prior orders. Conversely, the North Carolina court had

no business usurping the continuing authority of the Dis

trict Court to supervise its earlier-issued decree. The ma

jority is correct in asserting that the Secretary’s approval

of the consent decree prevents the District Court from

awarding the plaintiffs the relief they requested: to en

join the Secretary from approving the consent decree.

But since unrequested relief is available that would grant

plaintiffs the ultimate remedy they sought—to require the

Department to abide by the earlier orders of the District

Court—this case is not moot. The District Court should

order the Department to petition the North Carolina

court to allow it to withdraw from the consent order. If

the Secretary cannot withdraw, then the Department

should be cited for contempt for not complying with the

injunction the District Court issued in 1977. Since either

of these remedies would further the Department’s com

pliance with the earlier orders of the District Court, ef

fectual relief is available and this case is not moot.

Therefore, in my judgment, the majority incorrectly af

firms the result reached below.

I. Background

Before addressing the holdings of the District Court

and the majority, it is imperative to understand the ori

gins of the controversy in this case. A review of the his-

toiy of segregation in Southern higher education, of Title

VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its implementa

tion, of the Adams litigation, and of the specific events

precipitating this suit is essential to exposing the fail

ings of the holdings of the District Court and the ma

jority.

A. Segregation in Southern Higher Education

After the Civil War states throughout the South en

acted statutes or constitutional provisions requiring seg-

4

regation of the races in elementary and secondaiy

schools.0 E.g., North Carolina Laws 1868-G9, ch. 184,

§ 50, p. 471; North Carolina Const. 1875, Art. IX, §2.

Initially, these provisions did not apply to colleges or uni

versities. Nonetheless, state legislatures created a pattern

of segregation through individual enactments establishing

institutions intended for only one race, and thereafter

Southern states confirmed this pattern by passing stat

utes extending compulsory racial segregation to higher

education.10

With the Supreme Court’s implicit sanction in Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), the states for decades

maintained separate institutions of public education.

However, in a series of higher education cases starting

in 1938, the Court ordered admission of black students

to white-only graduate schools after finding inequalities

between the opportunities offered to blacks and whites

with the same educational qualifications. Missouri ex rel.

Gaine3 v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938); Sipuel v. Board

of Regents of University of Oklahoma, 332 U.S. 631

(1948); Siveatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950); Mc-

Laurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950).

These suits had their counterpart in North Carolina in

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F.2d 949 (4th Cir.), cert,

denied, 341 U.S. 951 (1951). In 1939, after Missouri ex

rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra, North Carolina had added

a Law School for Negroes to the North Carolina College

for Negroes at Durham.11 Subsequently, four qualified

black students applied for admission to the School of Law

at the University of North Carolina. They were rejected

solely because of their race. The students brought suit

0 U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, Equal Protection op the

Laws in Public Higher Education 9 & n.46 (1960).

10 Id. at 9 & n.47.

11 See McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F.2d 949, 951 (4th

Cir.), cert, denied, 341 U.S. 951 (1951).

against the school authorities under the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The State argued

that the Law School for Negroes afforded an education

substantially equivalent to that offered at the University’s

law school. The federal district judge dismissed the com

plaint. On appeal the Fourth Circuit concluded “that the

Negro School is clearly inferior to the white’’ and re

versed the lower court’s decision on the basis of Siveatt

v. Painter, supra, 187 F.2d at 950.

Such cases laid the groundwork for Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). In Brown the Court

rejected “separate but equal” public education as violative

of equal protection of the laws, finding that separate edu

cational facilities were inherently unequal. Id. at 495.

Nonetheless, many Southern states displayed immediate

intransigence in the face of Brown. For instance, on

May 23, 1955 the Board of Trustees of the University of

North Carolina passed a resolution reaffirming its policy

against admission of blacks to the all-white undergraduate

schools of the University system.” In Frasier v. Board,

of Trustees, 134 F.Supp. 589 (M.D. N.C. 1955) (three-

judge court), ajf’d, 350 U.S. 979 (1956), this policy was

held to violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment. The court flatly rejected the Uni

versity’s argument that Brown applied only to lower pub

lic schools and not to segregataion at the college or uni-

12 The resolution stated:

The State of North Carolina having spent millions of

dollars in providing adequate and equal education facili

ties in the undergraduate departments of its institutions

of higher learning for all races, it is hereby declared to

be the policy of the Board of Trustees of the Consolidated

University of North Carolina that applications of Negroes

to the undergraduate schools of the three branches of the

Consolidated University be not accepted.

Quoted in Frasier v. Board of Trustees, 134 F.Supp. 589, 590

(M.D. N.C. 1955) (3-judge court), aff’d, 350 U.S. 979 (1956).

6

vcrsity level. 134 F.Supp. at 592 (University’s conten

tion was “without merit” ).

Even with the passage of time, resistance in the Deep

South to desegregation of higher education remained in

tense, while other Southern states exhibited only “token

compliance” with the mandate to desegregate.1B In North

Carolina, for example, by 1964 the traditionally white in

stitutions of public higher education remained 99 percent

white; the traditionally black institutions remained 99.9

percent black.14

B. Enactment of Title VI

Spurred by the general lack of progress that had been

achieved by constitutional litigation, Congress adopted a

federal solution to the problems e f segregation and racial

discrimination in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d et seq. (1976 & Supp. IV 1980).

Title VI declares that “ [n]o person in the United States

shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin,

• * * be subjected to discrimination under any program

or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Id.

§ 2000d. Each federal agency empowered to extend fed

eral aid is both “authorized and directed" to effectuate the

law with respect to the particular programs it admin

isters. Id. § 2000d-l (emphasis added).15 The ultimate

'»U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, supra note 9, at 56, 69.

14 H. Edwards & V. Nordin, Higher Education and the

Law 515 n.5 (1979).

lB As originally proposed by the Administration, Title VI

would simply have granted each agency discretion to withhold

federal funds from public agencies that discriminated. House

Doc. 124, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., Message from the President

of the United States Relative to Civil Rights at 24 (June 19,

1963). However, the House Judiciary Committee reported

out a bill close to the ultimately enacted statute that declared

unequivocal rights and made their agency vindication manda

tory. Thus the reported bill made it "the mandatory duty of

every Federal department or agency to utilize the funds pro

7

sanction for violation of the Act is termination of federal

funds. Id. The Department of Health, Education and

Welfare (HEW) was the original enforcement agency in

the field of higher education. The Department of Educa

tion assumed this responsibility in 1979.15

Unfortunately, because of the problem of lax enforce

ment, enactment of Title VI produced little change at the

college or university level. As late as 1969 HEW had

taken virtually no action to effectuate the law with re

spect to institutions of higher education. Thus in North

Carolina the traditionally white institutions remained

98 percent white.” Between January 1969 and February

1970 HEW finally undertook its first enforcement efforts.

Having concluded that ten states,’8 including North Caro

lina, were operating segregated systems of higher educa

tion in violation of Title VI,19 the Department sent letters

of noncompliance to each of these states.20 HEW re

quested each state to submit a desegregation plan within

vided for Federal financial assistance in every program or

activity to enforce civil rights requirements (sec. 602).” H.R.

Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., Pt. 1 at 76 (1963) (Mi

nority report's characterization) (emphasis added).

16 See note 2 supra.

17 H. Edwards & V. Nordin, supra note 14, at 515-516 n.5.

18 Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, North Carolina, Flor

ida, Arkansas, Pennsylvania, Georgia, Maryland, and Vir

ginia.

19 Adams v. Richardson, supra note 4, 351 F.Supp. at 637-

638.

20 The letter to North Carolina characterized the State’s

system of higher education as one “in which certain institu

tions are clearly identifiable as serving students on the basis

of race.” Letter from Leon Panetta, Director, Office of Civil

Rights, HEW, to Governor Robert W. Scott, February 16,

1970, quoted in Rentschler, Courts and Politics: Integrating

Higher Education in North Carolina, 7 NOLPE Sen. L. J. 1,

2 (1977).

8

120 days. North Carolina and four other states21 totally

ignored the request. The other five s ta tes22 submitted

plans that were unacceptable to HEW. Nonetheless, HEW

took no further action against any state.2'’ Thus the ma

laise of indecisive enforcement efforts continued.

C. The Adams Litigation

In late 1970 appellants sued senior HEW officials, al

leging defaults in the administration of their Title VI

responsibilities. The lower court agreed. Finding the De

partment’s policy to be one of “benign neglect,” 24 the

District Court concluded that HEW had “not properly

fulfilled its obligation under Title VI to effectuate the

provisions of Section 2000d of such Title and thereby to

eliminate the vestiges of past policies and practices of

segregation in programs receiving federal financial as

sistance.” Adams v. Richardson, 351 F.Supp. 636, 637

(D. D.C. 1972) (Memorandum Opinion). The court then

declared that the time for securing voluntary compliance

had “long since passed” and that HEW’s continued fi

nancial assistance to segregated systems of higher educa

tion in the ten states violated plaintiffs’ rights under

Title VI. Adams v. Richardson, 356 F.Supp. 92, 94 (D.

D.C. 1973) (Declaratory Judgment and Injunction Or

der). Therefore, the court ordered HEW to institute

compliance proceedings within 120 days against those

states that had not submitted acceptable plans. Id.

On appeal the government argued that the District

Court lacked jurisdiction to review the Department’s ac

tions 2" and asserted that the lower court’s order “virtu-

21 Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Florida.

25 Arkansas, Pennsylvania, Georgia, Maryland, and Vir

ginia.

22 Adams v. Richardson, supra note 4, 351 F.Supp. at G38.

2< Id. at 642.

n Brief for Appellants at 11-16 in Adams v. Richardson,

supra note 5.

9

ally transferred ] the responsibility for the administra

tion of Title VI to a single district judge.” 28 Nonethe

less, a unanimous Court of Appeals affirmed, Adams v.

Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973) (en banc)

(per curiam),2'' although it gave HEW an additional pe

riod of 180 days to secure acceptable plans, id. a t 1165.

The court explicitly rejected HEW’s argument that en

forcement of Titlp VI was committed to agency discre

tion and that review of such action was not within the

jurisdiction of the court. Id. at 1161-1163. Instead, the

court’s purpose was “to assure that the agency properly

construes its statutory obligations, and that the policies

it adopts and implements are consistent with those duties

and not a negation of them.” Id. at 1163-1164 (footnote

omitted).

HEW then sent individual communications to each of

the ten states and identified the critical requirements of

acceptable desegregation plans. Thereafter North Caro

lina and seven other states 28 submitted higher education

plans. In June of 1974 HEW found these plans accepta

ble and approved them.28 In 1975 appellants moved for

further relief, emphasizing numerous deficiencies in the

approved plans. The appellants focused their attack on

the plan that North Carolina submitted in 1974 89 (“the

28 Id. at 10.

27 The court sua sponte decided to hear the case en banc

because of the exceptional importance of the issues involved.

28 Oklahoma, Florida, Arkansas, Pennsylvania, Georgia,

Maryland, nnd Virginia.

29 The remaining two states, Louisiana and Mississippi,

were referred to the Department of Justice for enforcement

proceedings.

50 See Motion for Further Relief and Points and Authorities

in Support Thereof, Adams v. Weinberger, D. D.C. Civil Ac

tion No. 3095-70 (filed 1975).

'W PSWW NMW.

10

1974 Plan” )."1 Appellants requested that HEW be re

quired to revoke its approval of the desegregation plans

of North Carolina and the other states, and that the

states be directed to submit new plans.

In 1977 the lower court once again ruled in favor of

appellants. Adams v. Califano, 430 F.Supp. 118 (D. D.C.

1977) (Second Supplemental Order). The court found

that the desegregation plans submitted by North Carolina

and five other Btates "2 “did not meet important desegre

gation requirements” earlier specified by HEW and “have

failed to achieve significant progress toward higher edu

cation desegregation.” Id. at 119. The court therefore

ordered HEW to notify the Bix states, including North

Carolina, that the plans submitted by them were not ade

quate to comply with Title VI. Id. at 121.

Moreover, the court ordered HEW to transmit to the

states and to serve upon appellants and file with the court

“final guidelines or criteria specifying the ingredients of

an acceptable higher education desegregation plan.” Id.

In particular, the court recognized

the need to obtain specific commitments necessary

for a workable higher education desegregation plan

11 The Revised North Carolina State Plan for the Further

Elimination of Racial Duality in the Public Post-Secondary

Education Systems (May 31, 1974). A copy of the plan was

filed with the District Court in 1974 as Appendix XIV (e), and

is part of the record on appeal in the case at hand.

« The other states were Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Okla

homa, and Virginia. The court deferred action with respect

to Louisiana and Mississippi, which were the subject of judi

cial enforcement proceedings elsewhere; Maryland, whose

claim that HEW failed adequately to engage in voluntary

compliance was pending before another Court of Appeals; and

Pennsylvania, which was in the midst of settlement negotia

tions. Thus, where the Department was fulfilling its legal

obligations, the court deferred action. On the other hand,

with respect to the six states where the Department had failed

to do so, the court intervened.

11

* * * concerning admission, recruitment, and reten

tion of students * * *, concerning the placement and

duplication of program offerings among institutions

* * ", the role and the enhancement of Black institu

tions * * *, and concerning changes in the racial

composition of the faculties involved * * *.

Id. at 120.

In directing the parties to draft the order the District

Judge had made clear that he wanted the Department to

be “under the compulsion of a Court Order to submit to

the Btates certain specific requirements which the states

must respond to * * *.” "* This mandate was directly in

line with the concern of this court en banc that HEW

had “not yet formulated guidelines for desegregating

state-wide systems of higher learning * * *.” 480 F.2d

at 1164 (footnote omitted).*4 HEW was ordered to re

quire each state to submit revised desegregation plans

within 60 days of receipt of the criteria and to accept or

reject such submissions within 120 days thereafter. 430

F.Supp. at 121.

Pursuant to the “specific direction” of the District

Court, HEW issued “Amended Criteria Specifying In

gredients of Acceptable Plans to Desegregate State Sys

tems of Public Higher Education,” 42 Fed. Reg. 40780

(1977) (hereafter Amended Criteria), Appendix of

Plaintiffs-Appellants (App.) 102. According to the court,

811 Transcript of January 17, 1977 Hearing at 54 (emphasis

added).

84 This court, 480 F.2d at 11G4 n.9, had cited Alabama

NAACP State Conference of Branches v. Wallace, 269 F.

Supp. 346 (M.D. Ala. 1967). In that case a three-judge court

had stressed the importance of “explicit, certain and definite”

guidelines for assuring compliance with the law. Id. at 352.

As the court stated, “In the absence of judicial review, the

school authorities may and should respect the Guidelines as a

reliable guide to what the Department's enforcement action

should be.” Id. at 351.

12

wth the statute 88 and the Constitution *• imposed an af

firmative duty on the states to devise and implement

plans that would be effective in desegregating higher edu-

” IIEW regulations implementing Title VI provided that

8 r r nt ° f, federal funds had previously discrimi-

S d °r thf baS'8 ° f raCe’ “tho rec'P»ent must take affirm a- tive action to overcome the effects of prior discrimination.”

45C .F R. § 80 3(b) ( 6 ) 0 ) (1977) (emphasis added). These

n o f i m ' ° T h 8tl ex! ? ' See 34 C F R ' § 100.3(b) (6) (i)

L 8i° 1' ,Thus’. acc°rdmg to the Department, the states had

a statutory obligation to devise and implement plans that

Am .ach,evin2 the desegregation of the system.”

Amended Criteria specifying Ingredients of Acceptable Plans

to Desegregate State Systems of Public Higher Education 44

App. 102 10380’ 40781 (1977) (hereafter Amended Criteria),

80 Relying on the 14th Amendment, the Supreme Court long

go made clear that public school officials have “the affirma

tive duty to take whatever steps might be necessary to convert

to a unitary system in which racial discrimination would be

c lminated root and branch.” Green v. County School Board

of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 437-438 (1968). This

2 ™ to be implemented “now," id. at 439 (emphasis in

^ a,);,and,the obJ?ctlve waa “to eliminate from the public

rhn? 8 ®Ij e8fjget °f s^te-imposed segregation.” Swann v.

/in-TiV *Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 15

(1071). While the Supreme Court has not made clear’the

precise application of its desegregation doctrines to institu

tions of higher education, the weight of precedent at the lower

court level confirms the application of the duty to integrate

f h‘3n°r adl,cation' See- e-9-. Morris v. State Conned of Higher Education, 327 F.Supp. 1368, 1373 (E.D.

Va.) (3-judge court), aff’d per curiam, 404 U.S 907(1971)-

Ellin^ 1’ 2̂ FSupp- 937- 942 (M.D. Tenn.’ 1968). These cases hold that, while “ [t]he means of eliminat-

lng discrimination in public schools necessarily differ from its

elimination in colleges, * * * the state’s duty is as exacting."

Norris, supra, 327 F.Supp. at 1373 (emphasis added). In

issuing the Criteria the Department concluded that “ ftlhe

affinnative duty to desegregate applies with equal force to

higher education.” Amended Criteria, supra note 35, nt 40780

App. 102 (citing Norris, supra; Lee v. Macon County Board

of Education, 267 F.Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala.) (3-judge court),

13

cation systems.37 The Department recognized that the

court had directed it “to prepare criteria which would

i entity for the states the specific elements to be included

l h Tri.reVi? 1(,eSegregatio11 pIans-” I d ■ at 40781, App.

• Taus> [cjonsistent with the requirements of Title

VI these criteria set forth the elements of a desegrega

tion plan which would eliminate the effects of past dis-

Z Z nat'0no The detai,ed sefc of criteria issued by

HEW specified the ingredients of acceptable plans, as re-

qinred by this court’s order.™ HEW subsequently prom

ulgated Revised Criteria” to serve as guidelines for

desegregation plans in all states. See 43 Fed. Reg. 6658

HEW then attempted to secure revised plans under the

new Desegregation Criteria. By early 1979, the Depart

ment had obtained compliance in five of the six states

covered by the District Court’s Second Supplemental Or

der. HEW s efforts proved fruitless, however, with re

spect to North Carolina. First, the Department found

as a matter of substance that the measures proposed by

the State offered “no realistic promise * * * of desegre-

gating the UNC [University of North Carolina] system

in the foreseeable future, as the law requires.” 80 Second,

(M.D.Tenml9722)5 (1%7) J ^ ** ° Unn’ 337 RSuPP- 573

102 10™end*d Eriteria' ™pra note 35, at 40780-40781, App.

102-103. See Comment, Integrating Higher Education' De

L b U m l l 9 7 2 ) tkC Afflrmf l C DutV ^ Integrate, 57 IOWA U ilKV. 898 (1972) ; Comment, Racially Identifiable Dual Sys

tems of Higher Education: The 1071 Affirmative Duty to

Desegregate, 18 Wayne L. Rev. 1069 (1972) • Note The A t

t0 integrate in Higher Education, 79 Y a i .e U

88 See Amended Criteria, supra note 35, at 40780, App. 102 •

Adams v. Cahfano, supra note 4, 430 F.Supp. at 121.

r /°.ILEt.te^ ,fr1oai Albert T. Hamlin, Ass’t General Counsel

m M p p ! m HEW' ta ,08°ph Uvin’ Es’ - D“ - «

14

as to the form of the State’s settlement offers—a consent

decree to be submitted to a court—the government ex

plained that “IIEW’s enforcement of Title VI would be

irreparably undermined if a recipient of funds could

routinely by-pass statutorily-mandated administrative

compliance procedures by the expedient of filing a law

suit and then obtaining a substantive consent decree

* * * >> 40

As a result, in April 1979 HEW filed a Notice of Op

portunity for Hearing to determine whether federal funds

to assist higher education in North Carolina should be

terminated. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-l (1976) (mandating

hearing before fund termination). North Carolina re

sponded by filing suit against HEW in the Eastern Dis

trict of North Carolina, seeking, inter alia, to enjoin the

administrative proceeding and to enjoin enforcement of

HEW’s Amended Criteria. State v. Dep't of Health, Edu

cation & Welfare, 480 F.Supp. 929 (E.D. N.C. 1979).

The government, in’ turn, requested that the action be

removed to the District Court for the District of Colum

bia because of comity principles and because North Caro

lina’s suit collaterally attacked the Adams orders. Judge

Dupree rejected the government’s motion, id. at 931, but

also denied North Carolina its requested relief, id. at 937-

938.4‘ Thus a formal hearing commenced in July 1980

before an administrative law judge, and the Adams plain

tiffs were allowed to participate in that hearing. The

parties eventually completed presentation of their affirma

tive cases, and the record already includes 16,000 pages

of testimony and over 600 exhibits.

40 Letter from James P. Turner, Deputy Ass’t Att’y Gen.,

Civil Rights Div., Dep’t of Justice, to Joseph J. Levin, Esq.,

July 23,1979, at 1, App. 108.

41 However, the court did rostrain HEW from imposing

limited deferral of funds. 480 F.Supp. at 930.

16

D. Events Precipitating This Suit

While the administrative hearing was in progress the

Department began secret negotiations with North Caro

lina. The new Secretary of Education subsequently cred

ited United States Senator Jesse Helms with helping to

get the talks started.42 On June 20, 1981 Secretary Bell

publicly announced the government’s intention to settle

its dispute with the North Carolina University System.

Brief for appellees at 7. On June 22 appellants were noti

fied of the proposed agreement and were served with a

copy of the proposed consent decree.4" The Department

indicated, astonishing as it may seem given both the con

tinuing injunctive order of the District Court and the

government’s previous attempts to remove the North Car

olina litigation to the court here,44 that it might submit

the proposed agreement to the North Carolina court as

soon as June 25, 1981,45 the expiration date of the 72-

hour comment period mandated by Judge P ratt’s previous

court order.49

On June 25, 1981 appellants went to the District Court

seeking a temporary restraining order and a preliminary

injunction to stop the Secretary from entering the pro

posed agreement and thereby to prevent the Secretary

from violating the prior injunctive decree. The District

Court’s denial of relief resulted in this appeal.

42 Washington Post, June 21, 1981, p. A ll, cols. 1-2. This

article was brought to the court’s attention by the govern

ment. See brief for appellees at 7.

4* See Letter, supra note 6. The consent decree appears in

the record at App. 32.

44 See State v. Dep’t of Health, Education & Welfare, 480

F.Supp. 929 (E.D. N.C. 1979) (motion denied).

49 Letter, supra note 6.

49 See note 7 supra.

16

II. T he Ruling of the D istrict Court

Appellants Bought to restrain the Secretary of Educa

tion from entering into the proposed agreement with the

State of North Carolina.47 On June 25, 1981, in an opin

ion delivered from the bench, Judge P ra tt denied the re

quested relief for lack of jurisdiction. Adams v. Bell,

D. D.C. Civil Action No. 70-3095 (June 25, 1981), App.

26-30. The court reasoned as follows: First, the court

stated that its jurisdiction “was directed against the

agency to see that the agency complied with its statutory

[and] constitutional responsibilities.” 48 Second, the court

found that “ [t] he Agency has carried out its function.” 48

Therefore, the court concluded, “we would wholly lack

jurisdiction.” 80

In my opinion, the lower court’s reasoning is not in

ternally consistent. Plaintiffs alleged that the Department

was not complying with its legal obligations. The Dis

trict Court clearly reached this issue and concluded that

the agency had complied. But to make Buch a determina

tion, the District Court must have had jurisdiction, for

“ [jurisd iction is authority to decide the case either

way.” The Fair v. Kohler Die cfe Specialty Co., 228 U.S.

22, 25 (1913). As the Supreme Court long ago stated:

"To determine whether [a] claim is well founded, the

District Court must take jurisdiction whether its ultimate

resolution is to be in the affirmative or the negative.”

Montana-Dakota Utilities Co. v. North-Western Public

Service Co., 341 U.S. 246, 249 (1951) (emphasis added).

Thus the court’s conclusion that it wholly lacked jurisdic

tion cannot logically coexist with its determination that

the agency complied with its legal obligations.

47 See Motion for Temporary Restraining Order and Motion

for Preliminary Injunction, Adams v. Bell, D. D.C. Civil Ac

tion No. 70-3095 (filed June 25,1981), App. 4-5.

4B Transcript of June 25, 1981 Proceeding at 25, App. 30.

40 Id. at 24, App. 29.

1,0 Id. at 25, App. 30.

17

The majority opinion on appeal, choosing to ignore the

ground on which the case was argued and decided below,

commits a different, though similarly inexcusable, error.

The court properly asks whether the case is mooted by

the North Carolina court’s acceptance of the consent

decree. But the majority incorrectly asserts that it is,

arguing that appellants requested only that the Secretary

be enjoined from entering into that decree. “The action

sought to be prohibited has now been consummated.” Ma

jority opinion (Maj. op.) at 6. This argument confuses

the ultimate relief which appellants’ were pursuing—to

keep the Department from shirking its statutory obliga

tion and from evading the prior decrees of this court—

with the specific relief which appellants requested in their

petition—to enjoin the Secretary from entering into that

decree. Because the District Court can devise relief that

will prevent the Department from violating the court’s

earlier orders, the relief sought can be granted and this

case is not moot.81

III. T he District Court Had Jurisdiction Over

T his Action

In 1972 the District Court identified six separate statu

tory bases for jurisdiction over appellants’ original law

suit.82 Adams v. Richardson, supra, 351 F.Supp. at 640.

81 Accordingly, I believe that comity principles do not bar

the District Court from requiring that the Department peti

tion to withdraw from its consent decree. See Part V infra.

Indeed, I believe that the North Carolina court should not have

entertained either the earlier litigation or the consent decree

because of these same comity principles. A District Court

should never entertain a suit which impinges upon the order

of another court. See Gregory-Portland Independent School

District v. Texas Education Agency, 576 F.2d 81 (6th Cir.

1978), cert, denied, 440 U.S. 946 (1979) ; Lapin v. Shulton,

Inc., 333 F.2d 169 (9th Cir.), cert, denied, 379 U.S. 904

(1964).

82 Those statutory provisions were: 6 U.S.C. §§ 702-704

(review of agency action under the Administrative Procedure

A ct); 28 U.S.C. § 1331 (general federal question jurisdic-

18

At no point in the subsequent history of the lawsuit did

anyone question the lower court’s jurisdiction. On June

25, 1981, in argument before the District Court, appel

lants naturally asserted that jurisdiction over their mo

tion for injunction was identical with the jurisdiction

that obtained at the start of the case.0* The lower court

now holds that jurisdiction no longer exists, and the ma-

joiity of this panel affirms by finding that the case is

moot. Yet the lower court did not address any of the

specific jurisdictional bases identified in 1972. This was

a remarkable omission. Moreover, had the majority ana

lyzed these specific jurisdictional bases they would have

seen why the District Court must have continuing au

thority to supervise its prior decree (and, therefore, why

the Secretary s acceptance of the consent decree does not

moot this case).

Rather than belabor all the jurisdictional grounds, I

will focus on two of the most significant and obvious bases

on which the District Court should have acted.®1 Either

tion); id. § 1343(4) (jurisdiction over actions to protect civil

rights) ; id. § 1361 (jurisdiction over action to compel officer

of the United States to perform his duty) ; id. § 2201 (de-

clnratory judgment authority) ; id. 2202 (granting of further

necessary relief).

'"Transcript of June 25, 1981 Proceeding at 18, App. 23

(statement of Mr. Lichtman) ("the jurisdiction is the very

same jurisdiction that began this case”) ; id. nt 19, App. 24.

81 In determining the existence of jurisdiction, it is impor

tant to distinguish a dismissal for lack of jurisdiction from a

dismissal for failure to state a claim. 5 C. Wright & A.

Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure § 1350 at 543

(19G9). To determine subject matter jurisdiction, a court

must examine whether a plaintiff purports to state a federal

claim regardless of the actual validity of the claim. See

Wheeldin v. Wheeler, 373 U.S. 647, 649 (1963). Thus, with

respect to jurisdiction over federal questions, the only inquiry

is whether the claim is either wholly insubstantinl and frivo

lous or immaterial and made solely for the purpose of obtain-

.19

one of these grounds would have established jurisdiction

and formed a basis for structuring appropriate relief.

The first ground is jurisdiction to enforce prior decisions

and orders; the second ground is jurisdiction to determine

whether the Department is fulfilling its legal obligations.

A. Jurisdiction to Enforce Prior Decisions and Orders

There can be "no doubt that federal courts have con

tinuing jurisdiction to protect and enforce their judg

ments.” Central of Georgia R. Co. v. United States, 410

F.Supp. 354, 357 (D. D.C.) (3-judge court), afj’d, 429

U.S. 968 (1976). This continuing jurisdiction after ren

dition of a judgment must be broadly construed, or else

the judicial power "would be incomplete and entirely in

adequate to the purposes for which it was conferred by

the Constitution.” Riggs v. Johnson County, 73 U.S. (6

Wall.) 166, 187 (1867). As a result, such jurisdiction

clearly extends to efforts to assure that a prior judgment

“may be carried fully into execution or that it may be

given fuller effect * * Dugas v. American Surety Co

300 U.S. 414, 428 (1937).

In this case plaintiffs sought to enjoin the Department

from entering into an agreement that would have al

legedly undermined the Second Supplemental Order of the

District Court,88 and other court orders, in two distinct

ways.

First, in 1977, the District Court had ordered the De

partment to transmit “final guidelines” ®* that would con

stitute “specific requirements which the states must re-

ing jurisdiction. See Dell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678, 682-683

(1946) ; Harper v. McDonald, 679 F.2d 955 (D.C. Cir. 1982).

88 Adams v. Califano, supra note 4.

80 4 3 0 F.Supp. at 121.

20

spond to * * * ” 87 The District Court had ruled that it

was HEW's responsibility to devise those criteria and ob

tain "specific commitments,” 88 and pursuant to the court’s

"specific direction” 80 the Department had promulgated

the Amended Criteria, supra. Yet, according to the plain

tiffs’ motion below, the Department had abandoned the

court-mandated Criteria in its proposed agreement with

North Carolina.00 Surely the District Court had jurisdic

tion over such a claim in order to carry “fully into execu

tion” and into “fuller effect” its prior judgment. Ju ris

diction in this respect is entirely analogous to that exer

cised in 1977. At that time the District Court had juris

diction because the Department had accepted state plans

that “failed to meet the requirements earlier specified”

by HEW in letters to the states.01 Here, the court nec

essarily had jurisdiction because North Carolina’s plan

allegedly failed to meet the requirements specified by

HEW pursuant to court order.

87 Transcript, supra note 33, at 54. (Another federal District

Court had also specifically ordered adoption of such criteria.)

See Mayor & City Council of Baltimore v. Mathews, 571 F.2d

1273,1276 (4tli Cir.) (Winter, J., concurring and dissenting)

(District Court enjoined Secretary of HEW to "adopt specific

standards for compliance with Title VI by institutions of

higher education”), cert, denied, 439 U.S. 862 (1978), aff'g

by equally divided coxirt Mandel v. HEW, 411 F.Supp. 542

(D. Md. 1976). See also Alabama NAACP State Conference

of Branches v. Wallace, 269 F.Supp. 346, 351 (M.D. Ala.

1967) (Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires Department to act

pursuant to guidelines of general applicability).

88 4 30 F.Supp. at 120.

80 Amended Criteria, supra note 35, 42 Fed. Reg. at 40780,

App. 102.

00 See Points and Authorities, supra note 6, at 5-10 (argu

ment that proposed agreement constitutes a total abandon

ment of Criteria).

01 430 F.Supp. at 119.

21

Second, in 1977 the District Court had also specifically

ordered the Department to revoke its acceptance of North

Carolina’s 1974 Desegregation Plan and the plans of five

other states because they were “not adequate to comply

with Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.” 02 Yet, ac

cording to the plaintiffs’ motion below, the 1981 proposed

agreement contained the same infirmities as the 1974

Plan whose approval was revoked by court order.08 The

District Court must have jurisdiction over such a claim if

it is to execute fully its prior judgments. Otherwise, the

agency could circumvent a court order with impunity.

B. Jxirisdiction to Determine Whether the Departmexit

is Fulfilling its Legal Obligations

A District Court indisputably has jurisdiction to deter

mine whether a federal department is fulfilling its legal

obligations. See Hill v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284, 289

(1976) (affirming District Court’s jurisdiction to remedy

department’s violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

and the Fifth Amendment). Indeed, the whole thrust of

the Adams litigation has centered on the court’s jurisdic

tion to determine whether the Department has properly

fulfilled its obligations under Title VI. As this court

stated in 1973, our role is “to assure that the agency

properly construes its statutory obligations, and that the

policies it adopts and implements are consistent with

those duties and not a negation of them.” Adams v.

Richardson, supra, 480 F.2d at 1163-64.

In the lower court, the crux of plaintiffs’ argument was

that by entering the proposed agreement the Department

would be defaulting on its legal obligations under Title

VI.04 Thus, as in 1972, the Department has "not prop

erly fulfilled its obligation under Title VI to effectuate

02 Id. at 121.

03 See Points nnd Authorities, supra note 6, at 10-11.

04 Sec brief for plaintiffs-appellants at 17.

22

the provisions of Section 2000d of such Title and thereby

to eliminate the vestiges of past policies and practices of

segregation in programs receiving federal financial as

sistance.” Adams v. Richardson, supra, 351 F.Supp. at

637. And, as in 1977, the Department was "continuing

to grant federal aid to public higher education systems

which have not achieved desegregation or submitted ac

ceptable and adequate desegregation plans * * Adams

P. Calif ano, supra, 430 F.Supp. a t 120.

For over a decade the Department’s performance in ef

fectuating its legal obligations under Title VI had been

abysmal. Only through, repeated intervention by the

courts of this circuit had progress been stimulated. But

suddenly, when faced once again with allegations that

the Department was falling down on the job, the District

Court held that it had no jurisdiction. The court thus

adopted the position argued by the government a decade

ago which the Court of Appeals en banc 88 unanimously

rejected. Because a court always has jurisdiction to de

termine whether a Department has fulfilled its legal obli

gations, the District Court’s dismissal for lack of juris

diction was, in my view, reversible error.

C. Erroneous View of the Court’s Jurisdiction

The District Judge relied heavily on dicta contained

in a footnote in the 1973 Adams en banc decision to pre

scribe narrowly the lower court’s jurisdiction.'8 The

Court of Appeals stated in part:

F ar from dictating the final result with regard to

any of these districts, the order [of the District

Court issued in 1972] merely requires initiation of a

process which, excepting contemptuous conduct, will

then pass beyond the District Court’s continuing con

trol and supervision. * * *

85 See text at p. 10 & nn.29-30 supra.

88 See Transcript, supra note 8, at 23, App. 28.

23

Adams v. Richardson, supra, 480 F.2d at 1163 n.5 (em

phasis added).

The District Judge misconstrued what the Court of Ap

peals intended by this language. To begin with, the Court

of Appeals was discussing a portion of the 1972 District

Court order that concerned primary and secondary school

districts, not state-operated systems of higher education.87

That is why the footnote refers to school “districts,” a

term inapposite to a discussion of state higher education

systems. Cf. id. at 1164 ("The problem of integrating

higher education must be dealt with on a state-wide

rather than a school-by-school basis.” ) (footnote omitted).

More importantly, although the enforcement process

was temporarily to pass beyond the District Court’s con

trol, it was not to do so permanently or irrevocably. In

deed, after further actions by HEW in accord with the

original District Court order, this case most definitely did

return to the "control and supervision” of the District

Court in 1977. In its Second Supplemental Order the

District Court once again examined HEW’s activities.

Adams v. Califano, supra, 430 F.Supp. 118. The District

Court’s assertion of jurisdiction in 1977 directly conflicts

with the attempt to narrow its authority here. At that

time plaintiffs argued that the Department had accepted

desegregation plans tha t failed to meet "the requirements

of [HEW’s]own detailed letters, or the ruling in this case

and other judicial authorities, or of Title VI and the

Constitution.” 88 The District Court reviewed HEW’s ac-

81 In Adams v. Richardson, supra note 4, 356 F.Supp. 92,

only one portion of the lower court’s order concerned higher

education. Id. at 94-95. The remainder of the decision in

volved elementary and secondary school districts and also

vocational and other schools. Id. at 95-100.

08 See Motion for Further Relief and Points and Authorities

in Support Thereof, Adams v. Weinberger, D. D.C. Civil Ac

tion No. 3095-70 filed in 1975 (motion leading to Adams v.

Califano, supra note 4).

24

ceptance of desegregation plans, ordered that the accept

ances be revolced, and ordered additional relief in several

areas. In 1981, plaintiffs returned to the District Court

and once again attempted to remedy the Department’s

failure in the proposed agreement to enforce its own Title

VI compliance standards, i.e., the Amended Criteria,

supra. The two cases are simply indistinguishable; if ju

risdiction existed in 1977, it still existed in 1981.

Both the lower court and the majority here, through

their holdings, display fundamental misunderstandings

about the Title VI enforcement process and about the

lower court’s authority to supervise its earlier decrees.

The Title VI enforcement process was first discussed in

footnote 5 of the en banc decision. See 480 F.2d at 1163-

64 n.5. As the Court of Appeals explained, federal funds

recipients must be given notice and a hearing to be found

formally out of compliance with Title VI.68 A hearing

examiner must then make a specific finding of non-com

pliance if statutory sanctions are to be imposed.70 The

examiner’s decision can be appealed to a reviewing au

thority, then to the Secretary, and finally to the courts.71

At that point, and only a t that point, a state has a right

to seek judicial review in the venue of its choice.72.

In this case, the individual enforcement process was

aborted. Unable to secure voluntary compliance, the De

partment had commenced an administrative enforcement

proceeding. However, instead of allowing the hearing to

be completed, the Department terminated it as part of

the proposed agreement.7* Thus, the hearing examiner

42 U.S.C. § 2000(1-1 (1976). See 34 C.F.R. § 100.8-100.9

(1980).

70 42 U.S.C. §2000d-l (1976). See 34 C.F.R. §100.10

(1980).

71 Id. ; see 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-2 (1976).

72 Adams v. Richardson, supra note 6, 480 F.2d at 1164 n.5.

78 See text at p. 16 supra.

25

never reached an initial decision, and the state’s right

to judicial review never accrued.

Yet the District Judge apparently was under the mis

taken belief that the state “got an adverse decision out of

the Hearing Examiner or the Administrative Law

Judge.” 74 As a result of this erroneous assumption, the

lower court felt that the state “had a right to appeal to

any court that they wanted to * * 78 This conclusion

is incorrect. The right of the state to appeal under Title

VI applies to a final administrative decision, and the ex

aminer in this case never even reached an initial deci

sion. Thus the state had no right to determine which

court would scrutinize the consent decree. Moreover, be

cause the Department did not allow the formal admin

istrative enforcement proceeding to run its course, it

was once again under the supervision of the rendering

court when the hearing was aborted.

The majority reinforces the District Court’s error by

broadly holding that the courts of this circuit cannot con

sider whether the Department is avoiding its Title VI

obligations by entering into particular consent decrees.

Maj. op. at 8 n.10. Instead, the majority asserts that

courts of other jurisdictions are the appropriate judicial

bodies for determining whether the Department is ful

filling its Title VI obligations. But this broad holding

misses the narrower, more fundamental issue that is at

Btake in this case: Does another court have the authority

to supervise an outstanding judicial decree that the Dis

trict Court previously rendered to compel the Department

to fulfill its legal obligations?78 The answer to this

74 Transcript, infra note 78, at 24, App. 29.

78 Id.

70 Because the issue in this case is whether a nonrendering

court can usurp the authority of a rendering court in the

supervision of a previously issued injunction, there is no rea

son to decide the more complex question concerning whether

26

question is obvious: only the rendering court can super

vise its continuing injunction, and a nonrendering court

should decline jurisdiction so long as the rendering court

can still provide a remedy. Since the District Court can

still provide effectual relief, see Part V infra, only it can

determine whether the Department is abiding by its

earlier order.

Because of their misunderstanding about the issue at

stake in this case, the lower court and the majority fail

to stand behind the effective enforcement of Title VI and

appellants’ constitutional rights. Just as the District

Court had jurisdiction in 1977 to order the Department

to revoke its approval of North Carolina’s 1974 Plan, so

the District Court had jurisdiction in 1981 to enjoin the

Department from approving a warmed-over version of

that same hopelessly inadequate plan.77 For roughly a dec

ade, the court’s jurisdiction focused on the Department’s

actions, and that is where and why jurisdiction had re

mained.

IV. T he Department Did N ot F ulfill Its Legal

Obligation

Although the District Court found that it lacked juris

diction, it nevertheless reached the merits when it found

that the Department "has carried out its function” 78 and

had thus complied with its statutory and constitutional

this court or courts of particular localities should determine

whether the Department is adequately enforcing Title VI.

Thus, the majority decides an issue that it need not reach, and

misses the narrower, threshold issue that this case presents.

See Maj. op. at 7 n.9 ("This court is not a national court of

appeals, not a judicial panel on multi-district litigation”) and

Maj. op. at 8 n.10 (courts of particular jurisdictions can de

termine whether the Department is shirking its enforcement

duty).

77 See Part IV infra.

78 Transcript of June 26, 1981 Hearing at 24, App. 29.

27

responsibilities.7® In my view, a careful examination of

the record demonstrates that the District Court seriously

erred when it reached this conclusion. First, in approv

ing North Carolina’s plan the Department was abandon

ing its own desegregation criteria, implementation of

which was judicially mandated. Second, the Department

was approving a plan with the same basic infirmities as

the 1974 Plan, which had already been judicially deter

mined to be inadequate under the law.

A. Abandonment of the Desegregation Criteria

In promulgating desegregation criteria pursuant to the

District Court’s order, the Department found specific

guidance in the prior opinions in the Adams litigation.80

Accordingly, the Amended Criteria, supra, provided nu

merous specific steps to be taken under three broad

rubrics: I. Disestablishment of the Structure of the Dual

System;81II. Desegregation of Student Enrollment;87 and

III. Desegregation of Faculty, Administrative Staffs, Non-

Academic Personnel, and Governing Boards.88

A comparison of the North Carolina plan 84 with the

Amended Critei-ia reveals innumerable, fundamental dis-

70 Id. at 25, App. 80.

80 For instance, the District Court had found that "specific

comments [were] necessary * * * concerning admission, re

cruitment, and retention of students * * *, concerning the

placement and duplication of program offerings among in

stitutions * * *, the role and the enhancement of Black in

stitutions * * *, and concerning changes in the racial composi

tion of the faculties involved * * V ’ Adams v. Califano, supra

note 4,430 F.Supp. at 120.

81 Amended Criteria, supra note 85, 42 Fed. Reg. at 40782-

40783, App. 104-105.

82 Id. at 40783-40784, App. 105-106.

88 Id. at 40784, App. 106.

84 Consent Decree, App. 82.

28

crepancies. Several examples suffice to show a common

pattern. For instance, part I-C of the Criteria requires

the state to "take specific steps to eliminate educationally

unnecessary program duplication among traditionally

black and traditionally white institutions in the same

service area.” 85 This requirement reflected the District

Court’s concern that “specific commitments” were neces

sary in the area of "duplication of program offerings

among institutions.” 88 This was a crucial area for re

form because, as the Department hgd explained to North

Carolina’s counsel late in 1979, "[p]rogram duplication

is the most obvious vestige of past state-sanctioned segre

gation, and modifying the structure of non-core dupli

cated programs is the least intrusive, least disruptive

method which would promise to eliminate the vestiges of

discrimination in the UNC system.” 87 Nonetheless, the

new state plan approved by the Department is totally

silent on the subject of program duplication.88

P art II-C of the Criteria requires each state plan to

adopt the goal that "the proportion of black state resi

dents who graduate from undergraduate institutions in

the state system and enter graduate study or professional

schools in the state system shall be at least equal to the

proportion of white state residents who graduate from

undergraduate institutions in the state system and enter

88 Amended Criteria, supra note 35, 42 Fed. Reg. at 40783,

App. 105 (emphasis deleted).

88 Adams v. Califano, supra note 4, 430 F.Supp. at 120.

87 Letter, supra note 39, at 3, App. 113. By consolidating

identical programs at neighboring schools into a single school,

the result should be a larger and stronger program more likely

to attract students of all races.

88 This actually confirms a step backward. In 1978 the UNC

Board of Governors had committed itself to reduce program

duplication, though the University subsequently renounced

this goal. See Letter, supra note 39, at 3, App. 113.

29

Such schools.” 80 This criterion responded to a specific

concern expressed by the en banc Court of Appeals con

cerning the “lack of state-wide planning to provide more

and better trained minority group * * * professionals.” 00

Yet the new state plan approved by the Department does

not even mention, let alone adopt, this goal.

Similarly, part II-E of the Criteria mandated a com

mitment to take all reasonable steps to reduce the dis

parity between the proportion of black and white students

graduating from public institutions of higher education.81

This requirement wa‘s directly in line with the District

Court’s finding that specific commitments were necessary

concerning retention of students.02 Once again, the new

state plan ignores the requirement. As for admission of

students, also mentioned by the District Court,08 states

were required to adopt the goal that the proportion of

black high school graduates who enter public higher edu

cation equal the proportion of white high school graduates

who do so.04 The new plan does little more than docu

ment the existing disparity: 20.5 percent of all black

high school graduates entering university institutions as

opposed to 25.5 percent of white high school graduates.08

P art III of the Criteria identified a number of specific

measures to be taken to assure desegregation of faculty

80 Amended Criteria, supra note 35, 42 Fed. Reg. at 40783,

App. 105 (emphasis deleted).

00 Adams v. Richardson, supra note 5, 480 F.2d at 1165.

See Amended Criteria, supra note 35, 42 Fed. Reg. at 40783,

App. 105.

01 Id. at 40784, App. 106.

02 Adams v. Calif ano, supra note 4, 430 F.Supp. at 120.

08 Id.

04 Part II-A of Amended Criteria, supra note 35, 42 Fed.

Reg. at 40783, App. 105.

08 Consent Decree, Appendix I at 1, App. 69.

30

and non-academic employees."'* With respect to employ

ment, however, the new state plan fails to respond to any

of the requirements identified in the Criteria; instead, the

plan merely incorporates each constituted institution’s

individual affirmative action plan.87 This approach, does

not comport with the Court of Appeals’ guidance that

“ [t] he problem of integrating higher education must be

dealt with on a state-wide rather than a school-by-school

basis.” 88 Moreover, the inadequacies of the existing af

firmative action plans had already been explained in some

detail by the Department itself.88 For instance, under the

existing programs the faculties of the traditionally white

institutions in the UNC system will be no more than 3

percent black in 1985.100 Yet the Department has already

indicated that “ fujntil there are substantial numbers of

black faculty and administrators at the [traditionally