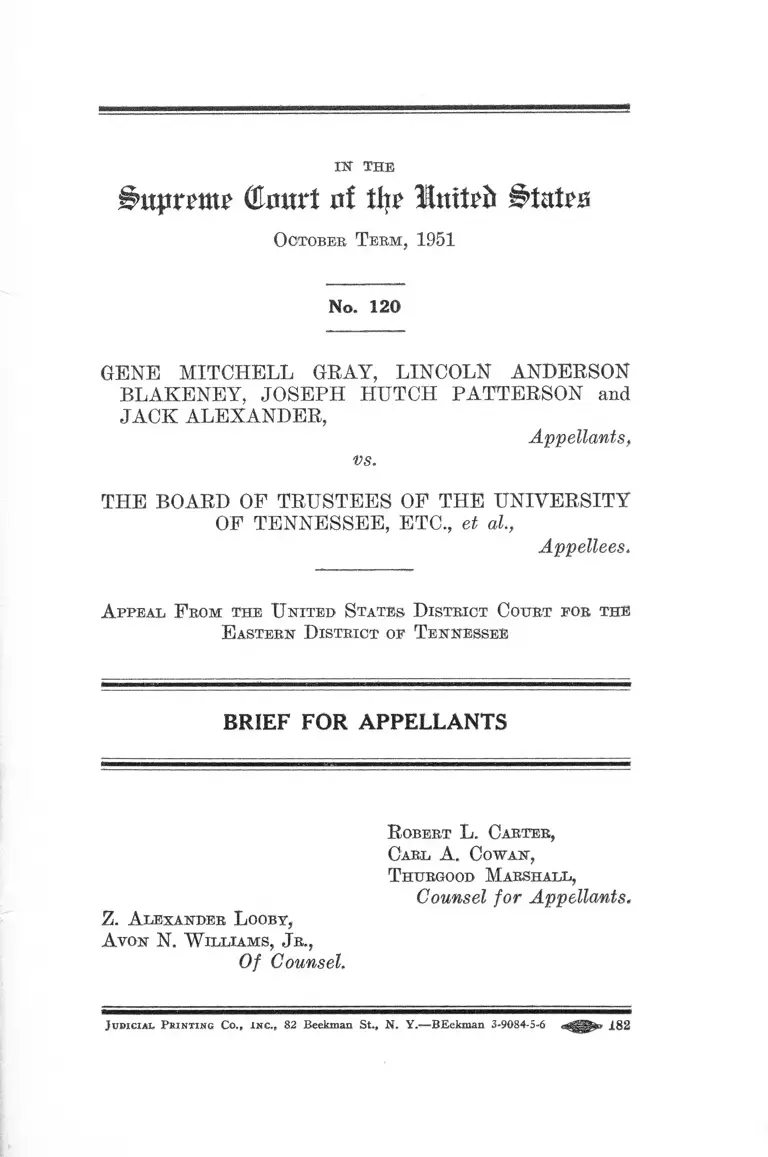

Gray v. University of Tennessee Board of Trustees Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gray v. University of Tennessee Board of Trustees Brief for Appellants, 1951. 22f5fe14-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5f22f224-d55f-4042-8c14-ad4e1c0b257b/gray-v-university-of-tennessee-board-of-trustees-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

IN' THE

uptime Court of tljr llmlrtt ^tatro

October T erm, 1951

No. 120

GENE MITCHELL GRAY, LINCOLN ANDERSON

BLAKENEY, JOSEPH HUTCH PATTERSON and

JACK ALEXANDER,

Appellants,

vs.

THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE UNIVERSITY

OF TENNESSEE, ETC., et al,

Appellees.

Appeal F rom the U nited States District Court for the

E astern D istrict of T ennessee

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

R obert L, Carter,

Carl A. Cowan,

T hurgood Marshall,

Counsel for Appellants.

7 . Alexander L ooby,

Avon N. W illiams, J r.,

Of Counsel.

J udicial P rin tin g Co.» in g ., 82 Beekman S t., N . Y.-—BEekm an 3-9084-5-6 J.82

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below............................................................... 1

Jurisdiction.............. 2

Statement of the C ase ................................................... 2

Errors Belied U pon ........................... 6

Summary of Argum ent.................................................. 7

Argument.................................................................... io

I—Appellants are entitled to admission to the Uni

versity of Tennessee subject only to the same rules

and regulations applicable to all other students . . . 10

II—This case is one in which a three-judge court has

jurisdiction and in which review by this Court on

direct appeal is w arranted..................................... 12

Conclusion........................................................................ 17

Cases Cited

American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327 U. S.

582 ........................................................................... 14,16n

American Insurance Co. v. Lucas, 314 U. S. 575 . . . . 15

Ayshire Collieries Corp. v. United States, 331 U. S. 132 17

Bader, In re, 271 U. S. 4 6 1 .......................................... 14

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U. S. 4 5 ...................... 13

Board of Supervisors, La. State University v. Wilson,

340 U. S. 909; rehearing denied 340 U. S. 939__10,13,15

Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U. S. 315 ........................ 14

Chicago v. Fieldcrest Dairies, Inc., 316 U. S. 168 .. 14,16n

11 I N D E X

PAGE

Ex parte Collins, 277 U. 8. 565 ..................................... 16

Exparte Hobbs, 280 U. S. 1 68 ............................. . 14

Ex parte Metropolitan Water Co., 220 U. S. 539 ......... 17

Ex parte Northern Pacific Ry., 280 U. S. 142 . . . . . . . . 17

Ex parte Williams, 277 U. S. 267 ................................16,17

General Electric Co. v. Marvel Rare Metals Co., 287

U. S. 430 ...................................................................... 17

Gong Lum v Rice, 275 U. S. 7 8 ..................................... 13

Grubb v. Public Utilities Commission, 281 U. S. 470.. 15

Gully v. Interstate Natural Gas Co., 292 U. S. 16 . . . . 15

International Garment Workers Union v. Donnelly

Garment Co., 304 U. S. 243 ......... .....................14,15,16

Jameson & Co. v. Morgen than, 307 U. S. 1 71 ............. 15

McCabe v. Atcheson, T. & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151.. 13

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (4th Cir. 1951);

Moore v Fidelity & Deposit Co., 272 U. S. 317............. 14

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637 ....... 8,10,11,

13,14,15

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 ...10,13,14

Oklahoma Gas & Electric Co. v. Oklahoma Packing Co.,

292 U. S. 386 .............................................................14,15

Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v. Russell, 261 U. S. 290.. 14

Pendergast v. United States, 314 U. S. 574 ................. 15

Phillips v. United States, 312 U. S. 246 ........................ 14

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ......................8,11,12,13

Public Service Commission of Missouri v Brashear

Freight Lines, Inc., 312 U. S. 784 ............................ 15

Query v. United States, 316 U. S. 486 ........................ 14

Railroad Commisssion of Texas v. Pullman, 312 U. S.

496 ................................................................................ 16n

Rice v. Arnold, 340 U. S. 848 . . . . ...................... ........ 12

I N D E X iii

PAGE

Riis & Co. v. Hocli, 99 F. 2d 553 (10th Cir. 1938)........ 16

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 IT. S. 631.................. 10,13

cert. den. 341 U. 8. 951 ...................................... 10

Smith v. Dudley, 89 F. 2d 453 (8th Cir. 1937) ............. 16

Smith v. Wilson, 273 U. S. 388 ..................................... 14

Spector Motor Service v. McLaughlin, 323 U. S. 101.14,16n

Sprunt & Son v. United States, 281 U. S. 249 ............. 15

Stratton v. St. Louis S. W. Rv. Co., 282 U. S. 10 .. .14,16,17

Sweat! v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 .......................8,10,11,13

Thompson v. Magnolia Petroleum Co., 309 U. S. 478.. 16n

Statutes Cited

Tennessee Code, Sections 11395, 11396, 11397 . . . . . . 4 , 7,12

Tennessee Constitution, Article 11, Section 12. . . . 3, 4, 7,12

United States Code, Title 28, Sections 1253 and

2101(h) ........................................................................ 2,9

United States Code, Title 28, Sections 2281 and

2284 ............................................................. 5,6,7,8,13,15

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment.5, 7,11

Other A uthorities

Berueffy, The Three Judge Federal Court (1942), 15

Rocky Mt. L. Rev. 6 4 ...................................... . l ln

Bowen, When are Three Judges Required (1931), 16

Minn. L. Rev. 1, ................................................... lln , 15

Frankfurter, Distribution of Judicial Power Between

United States and State Courts (1928), 13 Conn.

L. Q. 499 ............................................................ 16n

IV I N D E X

PAGE

Hutcheson, A. Case For Three Judges (1934) 47

Harv. L. Rev. 795 .............................................. . l ln

Lockwood, Maw and Rosenberry, The Use of the Fed

eral Injunction in Constitutional Litigation (1930),

43 How. L. Rev. 426 .................................................. 16n

Notes in 28 111. L. Rev. 839 (1934) .............................. l ln

Notes in 32 Mich. L. Rev. 853 (1934) ............. l ln

Notes in 38 Yale L. J. 955 (1929) ................................ l ln

Pogue, State Determination of State Law and the

Judicial Code (1928), 41 Harv. L. Rev. 623 ......... 16n

I N THE

Bnpvtm? (tort at % Imtrft BUtta

October T erm, 1951

No. 120

Gene Mitchell Gray, L incoln A nderson Blakeney,

J oseph H utch P atterson and J ack Alexander,

Appellants,

vs.

T he B oard op Trustees of the U niversity of T ennessee,

etc., et al.,

Appellees.

B R IEF FO R A PPELLA N TS

Opinions Below

After notice and hearing, the statutory three-judge

District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee dis

claimed jurisdiction as a statutory three-judge court and

remanded the cause for proceedings before a single judge.

An opinion setting forth the reasons for this action was

filed on April 13, 1951, and appears at pages 35-40 of the

record. It is not officially reported.

Without further hearing or notice to the parties, Dis

trict Judge R obert L. Taylor, in whose district the com

plaint had been filed, on April 20, 1951, filed an opinion in

which he found that appellants had been denied the equal

protection of the laws but refused to grant affirmative

relief. The cause was retained “ for such orders as may

o

be proper when it appears that the appropriate law has

been finally declared. ’ ’ That opinion is reported in 97 F.

Supp. 463 and may be found at pages 40-47 of this record.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title 28,

United States Code, Sections 1253 and 2101(b), this being

a direct appeal from an order which, in effect at least,

denied, after notice and hearing, appellants’ application

for a preliminary and permanent injunction to restrain

the enforcement by appellees of constitutional and statu

tory provisions of the State of Tennessee, and a Decem

ber 4, 1950 order of the Board of Trustees of the Uni

versity of Tennessee, on the grounds that these aforesaid

provisions and order deny to appellants the equal protec

tion of the laws as secured by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States.

Appellants in their complaint contested the constitution

ality of these provisions and order, and injunctive relief

was specifically sought (R. 1-20). In their answer, appel

lees defended their refusal to admit appellants to the Uni

versity of Tennessee on the grounds that they had no other

recourse under the constitution and statutes of the state

(R. 25-27). Thus, the constitutionality of the order of an

administrative agency and of laws of the State of Ten

nessee wms squarely in issue.

S ta tem en t of the Case

Appellants, having met all lawful requirements, made

due and proper application for admission to the graduate

and law schools of the University of Tennessee. Gene

Mitchell Gray sought permission to enroll in the graduate

school commencing in the fall quarter of 1950, and Jack

3

Alexander desired approval of Ms application for enroll

ment in the graduate school beginning in the winter quarter

of 1951. Both Lincoln Anderson Blakeney and Joseph

Hutch Patterson desired to enroll in the first-year class of

the law school in the winter quarter of 1951 (R. 9).

The University of Tennessee is the only state institution

offering the courses appellants desire to pursue, and they

would have been admitted except for the fact that they are

Negroes (R. 6). On December 4, 1950, appellees, the Board

of Trustees of the University of Tennessee, met and denied

appellants ’ application solely because of their color (R. 14).

Its action was embodied in the following formal order:

“ Whereas, the Constitution and the Statutes of

the State of Tennessee expressly provide that there

shall be segregation in the education of the races in

schools and colleges in the State and that a violation

of the laws of the State in this regard subjects the

violator to prosecution, conviction, and punishment

as therein provided; and,

“ Whereas, this Board is bound by the Constitu

tional provision and acts referred to ;

“ Be it therefore resolved, that the applications

by members of the Negro race for admission as stu

dents into The University of Tennessee be and the

same are hereby denied” (R. 14).

The applicable state constitution and statutory provi

sions upon which the above order vras based a re :

Article 11, Section 12 of Constitution of Tennessee

“ . . . And the fund called the common school

fund, and all the lands and proceeds thereof . . .

heretofore by law appropriated by the General As

sembly of this State for the use of common schools,

and all such as shall hereafter be appropriated, shall

remain a perpetual fund, . . . and the interest thereof

shall be inviolably appropriated to the support and

encouragement of common schools throughout the

4

State, and for the equal benefit of all the people

thereof. . . No school established or aided under

this section shall allow white and negro children to

be received as scholars together in the same

school. . .”

Section 11395 of the Code of Tennessee

“ . . . It shall be unlawful for any school,

academy, college, or other place of learning to allow

white and colored persons to attend the same school,

academy, college, or other place of learning.”

Section 11396 of the Code

. . It shall be unlawful for any teacher, pro

fessor, or educator in any college, academy, or school

of learning, to allow the white and colored races to

attend the same school, or for any teacher or edu

cator or other person to instruct or teach both the

white and colored races in the same class, school, or

college building, or in any other place or places of

learning, or allow or permit the same to be done with

their knowledge, consent or procurement.”

and

Section 11397 of the Code

“ . . . Any person violating any of the provisions

of this article, shall be guilty of misdemeanor, and,

upon conviction, shall be fined for each offense fifty

dollars, and imprisonment not less than thirty days

nor more than six months.”

Appellants thereupon filed on January 12, 1951, a com

plaint in the court below in the nature of a class suit, in

which application was made for both a preliminary and a

permanent injunction to restrain the enforcement of the

December 4th order of the Board of Trustees, Article 11,

Section 12 of the Constitution and Sections 11395, 11396

and 11397 of the Code of Tennessee, on the grounds that

the aforesaid order and provisions under attack deprived

5

appellants of rights secured under the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States (R. 1-20).

On February 1, 1951, appellees filed their answer in

which no material allegations in appellants ’ complaint were

controverted and in which the denial of appellants’ admis

sion to the University of Tennessee was defended on the

grounds that such denial was required by the constitution

and statutes of the state (R. 25-27).

On February 12, 1951, appellants filed a motion for

judgment on the pleadings (R. 28). The court, below, which

had been convened pursuant to Title 28, United States

Code, Sections 2281 and 2284 (R. 28-29), held a hearing in

Knoxville, Tennessee, on March 13, 1951, and on April 13,

1951, handed down an opinion in which jurisdiction was

disclaimed, the three-judge court was ordered dissolved

and the cause ordered to proceed before District Judge

R obert Taylor in whose district the complaint had been

filed (R. 35-40).

On April 20, 1951, Judge T aylor ruled that appellees’

refusal to admit appellants to the University of Tennessee

constituted a denial of the equal protection of the laws but

refused to issue any affirmative order in enforcement

of appellants’ rights (R. 40-47). Appellants thereupon

brought the cause here on direct appeal. This Court, on

October 15, 1951, ordered a hearing on the merits, post

poning further consideration of jurisdiction and the motion

to dismiss pending such hearing (R. 53).

6

Errors R elied U pon

T h e c o u r t below e r re d :

1. In re fu s in g to g ra n t a p p e lla n ts ’ m o tio n fo r ju d g m e n t

on th e p le a d in g s in th a t a p p e lle e s ’ o rd e r , re fu s in g a p p e l

la n ts ’ ad m issio n to th e U n iv ersity o f T en n essee , so lely

b ec au se o f th e ir co lor, m a d e p u rs u a n t to th e co n stitu tio n

a n d s ta tu te s o f T en n essee w as a n u n c o n s titu tio n a l d e p r iv a

tio n o f a p p e lla n ts ’ r ig h ts .

2. In h o ld in g th a t th e issues ra is e d d id n o t involve th e

co n s titu tio n a l ity o f th e co n s titu tio n a n d s ta tu te s o f th e S ta te

o f T en n essee a n d o f th e o rd e r o f th e a p p e lle e s as a n a d m in

is tra tiv e ag e n cy o f th e s ta te , fo r th e re a so n th a t in th e

o rd e r re fu s in g a p p e lla n ts ad m issio n a n d in th e ir a n sw e r to

a p p e lla n ts ’ co m p la in t, a p p e lle e s seek to ju s tify th e ir re fu s a l

on th e g ro u n d s th a t th e co n s titu tio n a n d s ta tu te s o f T en

n essee m a k e m a n d a to ry th e ir d en ia l o f a p p e lla n ts ’ a p p lic a

tions.

3. In re fu s in g to g ra n t a p p e lla n ts ’ a p p lic a tio n fo r a

te m p o ra ry a n d p e rm a n e n t in ju n c tio n as p ra y e d fo r in th e ir

co m p la in t.

4. In h o ld in g th a t th is cau se does n o t com e w ith in th e

ju r isd ic tio n o f a d is tr ic t c o u rt o f th re e ju d g e s as su ch ju r is

d ic tio n is defined in T itle 28, U n ited S ta te s C ode, S ections

2281 a n d 2284.

5. In o rd e r in g th e d isso lu to n o f th e th re e - ju d g e c o u r t

a n d in re m a n d in g th e cau se to D is tric t J u d g e R o b e rt T ay lo r

s ittin g a lo n e , s ince u n d e r T itle 28, U n ited S ta te s C ode, Sec

tions 2281 a n d 2284, a s in g le D is tr ic t J u d g e is w ith o u t

p o w e r a n d a u th o r ity to g ra n t o r d en y th e in ju n c tiv e re lie f

h e re in p ra y e d fo r.

7

Sum m ary of A rgum ent

On December 4, 1950, appellees, the Board of Trustees

of the University of Tennessee, issued a formal order deny

ing appellants’ admission to the graduate school and law

school of the University of Tennessee, because of their race.

This action was taken pursuant to Article 11, Section 12

of the Constitution and Sections 11395, 11396 and 11397

of the Code of Tennessee. These provisions make it un

lawful for white and Negro persons to attend the same

school or college, and violators are subject to criminal

prosecution. Appellants contend that the order, the con

stitutional and statutory provisions conflict with the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

and are, therefore, invalid. Application for injunctive re

lief to restrain enforcement by appellees of this unconsti

tutional state policy was made in the lower court pursuant

to Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281. Appellees

rely upon Article 11, Section 12 of the Constitution and

Sections 11395, 11396 and 11397 of the Code as a complete'

defense, and allege that they have no recourse other than

to refuse to admit appellants to the University of Tennessee

because of these state provisions.

Although actually upholding the constitutionality of

Article 11, Section 12 of the Constitution and Sections

11395, 11396 and 11397 of the Code, the court below ruled,

that appellants’ right to contest this question in a pro

ceeding of this nature had been foreclosed by decisions of.

this Court sustaining the constitutionality of state laws

requiring racial segregation. In effect, the court found

that appellants’ claim that the state’s policy was unconsti

tutional was not substantial. The only issue which appel

lants could raise, or had raised according to the court

below, was one of “ unjust discrimination . . . under the

Equal Protection Clause .. . and not the constitutionality of

certain statutes of the state of Tennessee” (R. 39-40). On

8

this basis, it was held that the jurisdictional requirements

fo r a district court of three judges under Title 28, United

States Code, Section 2281, had not been met; the three-

judge court was ordered dissolved and the cause remanded

fo r proceedings before Judge Taylor.

We are confident that the court was in error and that

all the requisite requirements essential to the jurisdiction

of a three judge federal court have been met. Appellants’

claim of unconstitutionality is that they have been and are

being denied educational opportunities and advantages by

the state equal to those available to all other persons. That

this allegation presents a substantial federal question can

hardly be open to doubt at this stage of the development

of our law.

While there is sharp disagreement between appellants

and the court below with respect to interpretation of the

substantive law determinative of appellants’ rights, what

ever view one takes, we submit, he is forced to conclude

that the jurisdictional requirements for a three judge court

have been met in this case.

We interpret the Sweatt and McLaurin cases to mean

that a state cannot enforce distinctions based upon race

with respect to graduate and professional education avail

able in state institutions. While Pless'if v. Ferguson was

not overruled, whatever may be the impact of the separate

but equal doctrine on the state’s power to impose racial

classifications and distinctions in general, in the area of

state graduate and professional education, that doctrine

is now totally without significance. The court below has

taken this Court’s discussion of Plessy v. Ferguson in the

Sweatt case to mean that enforced racial segregation in

state graduate and professional schools is still valid under

the separate but equal doctrine. In view of this unrecon-

cilable conflict in interpretation we hope the Court will

use this occasion to clarify the question once and for all.

9

The real problems involved in this appeal are pro

cedural—whether appellant may seek review of the action

of the court below on direct appeal or by petition for writ

of mandamus. Persuasive considerations tend to support

either remedy. Our position is that this Court has juris

diction on appeal, but if it does not, mandamus will lie.

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1253, grants a

direct appeal to this Court from a grant or denial of a

preliminary or permanent injunction by a three judge court.

Had the court below dismissed appellants’ complaint or

expressly denied their application for injunctive relief,

there would be no question concerning the jurisdiction of

this Court on direct appeal. Here, however, the court’s

order did not directly do either of those things. It merely

dissolved the three judge court and remanded the cause to

Judge T aylor sitting alone for further proceedings. This

being an appropriate case for a three judge federal court,

a single federal judge is without power to grant appellants

the relief for which they have applied. By dissolving the

only court having jurisdiction of the case, the lower court

made it impossible for appellants to secure injunctive re

lief. Appellants’ application for a preliminary and perma

nent injunction has been denied, therefore, as effectively

as if a judgment expressly denying the injunction or dis

missing the complaint had been entered. For those reasons

this Court has jurisdiction to review this case on direct

appeal.

1 0

ARGUMENT

I

Appellants are entitled to admission to toe Uni

versity of Tennessee subject only to the same rules and

regulations applicable to all other students.

The substantive rights which appellants are here seek

ing to enforce have been conclusively determined by prior

decisions of this Court. A state cannot deny educational

facilities to one racial group while offering it to others; and

where such facilities are available in only one state institu

tion, Negroes cannot be barred by the state from attending

that institution pursuant to a policy of enforced racial

separation. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S.

337. When educational facilities are offered to white per

sons, they must be offered to Negroes at the same time.

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631. A state can

not impose a policy of racial separation or make any other

distinctions grounded in race or color with respect to pro

fessional and graduate education offered at state universi

ties. In short, all persons meeting the requirements for

admission are entitled to attend graduate and professional

schools of state universities subject only to same rules and

regulations applicable to all other persons. Stveatt v.

Painter, 339 U. S. 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma, 339 IT. S.

637; Board of Supervisors, La. State University v. Wil

son, 340 U. 8. 909; rehearing den. 340 U. S. 939; McKissick

v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (4th Cir. 1951); cert, denied

341 U. S. 951. From the cases it is clear, therefore, that any

state action, whether in the form of an order of an admin

istrative agency, constitutional provision or statute which

prohibits appellants’ admission to the University of Ten

nessee is unconstitutional and void.

While this Court did not specifically strike down the

segregation statutes and laws of Texas and Oklahoma

under which those states sought to impose a policy of racial

segregation with respect to their graduate and professional

schools, the Court declared such policy void and unconsti

tutional. See McLaurin and Sweatt cases. The only pos

sible effect of those decisions was that such laws were no

longer operative.

It is true that the Court stated in Sweatt case at pages

635, 636 that it could not “ agree with respondents that the

doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 IT. S. 537 .. . requires af

firmation of the judgment below. Nor need we reach peti

tioner’s contention that Plessy v. Ferguson should he reex

amined in the light of contemporary knowledge respecting

the purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment and the effects

of racial segregation. See supra, page 631.” At that page

the Court said that McLaurin and Sweatt cases “ present

different aspects of this general question: To what extent

does the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, limit the power of a state to distinguish between

students of different races in professional and gradu

ate education in a state university? Broader issues have

been urged for our consideration, but we adhere to the

principle of deciding constitutional questions only in the

context of the particular case before the Court.” The

Court found that, the segregated law school in the Sweatt

case and the special rules and regulations imposed because

of race in the McLaurin case deprived both of equal edu

cational opportunities as required by the Fourteenth

Amendment. On reading the two cases it is clear that the

Court means that the constitutional requirement that equal

educational opportunities he afforded cannot be met in

graduate and professional schools where the state seeks to

enforce racial distinctions and seeks to treat persons dif

ferently because of race. Hence, the Fourteenth Amend

1 2

ment denies to the state the power to make racial distinc

tions or classifications with respect to that phase of the

state’s educational process.

The statement quoted above with respect to Plessy v.

Ferguson, which the court below interprets as “ eliminat

ing from the case the question of constitutionality of the

State statute which restricted admission to the University

to white students” (R. 38-39), was intended to emphasize

that the Court’s decisions specifically concerned graduate

and professional education only. But see Rice v. Arnold,

340 U. S. 848. Whatever present weight the separate but

equal doctrine may carry, it is clear that it can no longer

be used to determine whether equality of educational op

portunities in graduate and professional education is avail

able. Here where state laws seek to deny appellants ad

mission to graduate and professional schools of the state

university, they are clearly unconstitutional. The court

below believes them to still have vitality. We think the

Court should take this opportunity to clarify this point.

II

This case is one in w hich a th ree-judge court has

ju risd ic tion and in w hich review by th is C ourt on d i

rec t appeal is w arran ted .

A preliminary and a permanent injunction to restrain

the enforcement of appellees’ order of December 4, 1950,

refusing to admit appellants to the University of Tennes

see pursuant to Article II, Section 12 of the Constitution

of the State and Sections 11395, 11396, and 11397 of the

Code of Tennessee is here being sought on the grounds

that the order, constitutional provision and statutes de

prive appellants of their rights to equal educational op

portunities as secured under the Fourteenth Amendment

13

to the Constitution of the United States. Appellees are

state officers, Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada; supra, and

the Board of Trustees of the Universitj7 of Tennessee is an

administrative board within the meaning of Title 28, United

States Code, Sections 2281 and 2284. McLaurin v. Board

of Regents, supra; Board of Supervisors, La. State Uni

versity v. Wilson, supra. Appellants’ claim of unconstitu

tionality presents a substantial federal question. Sweatt

v. Painter, supra; Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra.

The court below seeks to redefine the issues raised by

describing them as allegations of unjust discrimination

under the equal protection clause rather than of constitu

tionality of state segregation statutes. The court stated

that state legislation requiring segregation was not uncon

stitutional because of the feature of segregation. Plessy

v. Ferguson, supra; McCabe v. Atcheson, T. & S. F. Ry. Co.,

235 U. S. 151; Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U. S. 45; and

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 are cited in support of

this contention. It is alleged that Sweatt v. Painter did

not change this rule. What we take the court to mean is

that in the light of these decisions appellants’ claim that

the state policy is unconstitutional has been foreclosed and

that hence that claim does not present a substantial federal

question.

We have already attempted to point out that the court

was in error in its analysis of the Sweatt case. We cannot

accept in toto either the court’s analysis of the other cases

and do not believe them to be applicable to this case. Even

assuming arguendo, however, the correctness of the court’s

view, we fail to see how it affects appellants ’ right to have

their applications for injunctive relief heard and deter

mined by a three judge court. At the very least those

cases stand for the proposition that enforced racial segre

gation is permissible as long as the facilities provided

Negroes are equal to those available to other racial groups.

14

This is the condition which must be satisfied if segregation

laws are to be held constitutional under the separate but

equal doctrine. Ergo, where that condition has not been

met, the segregation is unconstitutional. Certainly where

the record shows that the University of Tennessee is the

only state institution offering the courses appellants desire

to pursue; that they have been denied admission thereto

solely because of their race pursuant to state policy; and

appellants seek to enjoin enforcement of that policy on the

grounds that it conflicts with the federal constitution, a

substantial claim of unconstitutionality has been made.

See Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, supra.

Thus all ingredients essential to the jurisdiction of a

three judge federal court have been met. See Stratton v.

St. Louis S. W. Ry. Co., 282 U. S'. 10 ; Smith v. Wilson, 273

U. S. 388; Moore v. Fidelity & Deposit Co, 272 U. S. 317;

International Garment Workers Union v. Donnelly Garment

Co., 304 U. S. 243; Ex parte Hobbs, 280 U. S. 168; Phillips

v. United States, 312 U. S. 246; Oklahoma Gas & Electric

Co. v. Oklahoma Packing Co., 292 IT. S. 386; Ex parte

Poresky, 290 U. S. 30; In re Buder, 271 IT. S'. 461; Oklahoma

Natural Gas Co. v. Russell, 261 U. S. 290; Query v. United

States, 316 U. S. 486; American Federation of Labor v.

Watson, 327 IT. S. 582.1 Of course, equity jurisdiction

may be withheld in the public interest in exercise of sound

discretion, see Spector Motor Service v. McLaughlin, 323

IT. S. 101; Chicago v. Fieldcrest Dairies, Inc., 316 U. S. 168;

Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U. S'. 315; but the public inter

est in this case demands that the chancellor exercise his

power. See McLaurin v. Board of Regents, supra.

Decisions of a properly convened three judge court may

be reviewed by this Court on direct appeal, and if the case

1 For discussion of three judge court requirements, see: Hutcheson, A Case

For Three Judges (1934), 47 Harv. L. Rev. 795; Berueffy, The Three Judge

Federal Court (1942), 15 Rocky Mt. L. Rev. 64; Bowen, When Are Three

Judges Required (1931), 16 Minn. L. Rev. 1; and Notes in 28 111. L. Rev. 839

(1934); 32 Mich. L. Rev. 853 (1934); 38 Tale Ii. J . 955 (1929).

15

is not appropriate for decision by a three judge court, ap

peal to this Court does not lie. Oklahoma Gas & Electric. Co.

v. Oklahoma Packing Co., supra; Jameson & Co. v. Morgen-

thau, 307 U. S. 171; Public Service Commission of Missouri

v. Brashear Freight Lines, Inc., 312 IT. S. 784; Gully v.

Interstate Natural Gas Co., 292 U. S. 16; International

Garment Workers Union v. Donnelly Garment Co., supra.

Pendergast v. United States, 314 U. S. 574; American In

surance Co. v. Lucas, 314 IT. S. 575. Yet notwithstanding

lack of jurisdiction on appeal, this Court has issued orders

for the purpose of carrying out the objectives of Section

2281 by virtue of authority to determine whether the lower

court acted within its jurisdiction under that statute. See

Gully v. Interstate Natural Gas Co., supra.

Had the court below expressly granted or denied the

preliminary and permanent injunctions for which appel

lants prayed, appellants would clearly have been entitled

to review by direct appeal, McLaurin v. Board of Regents,

supra; Board of Supervisors v. Wilson, supra; or if the

court had dismissed the complaint, direct appeal would

have been the appropriate remedy, Grubb v. Public Utilities

Commission, 281 U. S. 470; Sprunt •& Son v. United States,

281 U. S. 249; and see Bowen, When Are Three Judges

Required (1931), 16 Minn. L. Rev. 1. Here, however, the

court below merely disclaimed jurisdiction and remanded

the cause for proceedings before a single district judge.

Unless this order constitutes a denial of injunctive relief

and/or a dismissal of the complaint, it would not appear

that direct appeal will lie.

In order to determine whether this order is appealable,

it is essential to examine its effect in respect to appellants’

cause of action. Appellants have met all the requirements

essential to jurisdiction of a three judge court and for pur

poses of this suit a hearing and determination by a three

judge court is mandatory. Under such circumstances a

single judge cannot assume or be awarded jurisdiction,

16

Stratton v. St. Louis S. W. Ry. Co., supra; Ex parte Col

lins, 277 U. S. 565; Ex parte Williams, 277 U. S. 267. See

also Riis & Co. v. Iloch, 99 F. 2d 553 (10th Cir. 1938); Smith

v. Dudley, 89 F. 2d 453 (8th Cir. 1937). Even if appellants

had not sought an injunction on g’rounds of unconstitution

ality, in which case a three judge court would not have been

necessary, International Garment Workers Union v. Don

nelly Garment Co., supra; appellees seek to defend their

conduct on grounds that it was mandatory under Tennessee

law and that they would be acting illegally in admitting

appellants. Thus, the issue of the conflict between the

Tennessee law and the Board’s order with the federal

constitution would have to be decided, and the convening

of a three judge court would have been rendered necessary

without regard to appellants’ complaint. At any rate, hav

ing properly elected to proceed under Section 2281, this is

not a situation where it may be appropriate for a court to

require appellants to seek a different mode of redress.2

By dissolving the only court which has jurisdiction to

grant appellants the relief sought, the court below has

effectively denied appellants injunctive relief. Such relief

cannot be granted by a single judge. Had Judge T a ylor

attempted to issue an injunction restraining appellees from

enforcing the state’s policy, it could only have been issued

on the grounds that this policy violated the constitution.

If Judge T a y l o r had granted injunctive relief under those

2 Usually this occurs when the issues involved concern constitutionality

under the state constitution, and state courts have not spoken. Normally

federal jurisdiction is withheld pending determination by the state courts of

the state question. See Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman, 312 IT. S.

496; Thompson v. Magnolia Petroleum Co., 309 TJ. S. 478; Chicago v. Field-

crest Dairies Inc., supra; Spector Motor Service v. McLaughlin, supra;

American Federation of Labor v. Watson, supra. See also: Pogue, State

Determination of State Law and the Judicial Code (1928), 41 Harv. L. Rev.

623; Frankfurter Distribution of Judicial Power Between United States and

State Courts (1928), 13 Corn. L. Q. 499; Lockwood, Maw and Rosenberry,

The Use of the Federal Injunction in Constitutional Litigation (1930), 43

How. L. Rev. 426. But here the sole and only question is whether the state

policy conflicts with federal constitution and hence the doctrine of the Pullman

ease has no application.

17

circumstances, he would have exceeded his jurisdiction.

Ex parte Metropolitan Water Co., 220 U. S. 539 ; Ex parte

Williams, supra; Stratton v. St. Louis S. W. By., supra; Ex

parte Northern Pacific By., 280 U. 8. 142; Ayrshire Collier

ies Corp. v. United States, 331 U. S. 132. Actually, there

fore, the court below has denied appellants injunctive relief

and their order should be as subject to appeal as a decree

expressly denying the injunctive relief sought. See Gen

eral Electric Co. v. Marvel Bare Metals Co., 287 U. S. 430.

Although Judge T a y l o r has declared appellants are

entitled to admission to the University of Tennessee, and

this decision was handed down last August, the state has

made no move to accept appellants as students at the Uni

versity. I t is clear that only by a restraining order

against enforcement of the state policy barring their admis

sion because of race, on grounds that this is in conflict with

the federal constitution, will appellants be admitted to the

University of Tennessee. The substantive law on this sub

ject is clear and conclusive, and appellants should not be

further delayed in their educational pursuits through pro

cedural delays. This case should be reviewed on the merits

and, we submit, this Court has jurisdiction on appeal.

Conclusion

Direct appeal to this Court from decisions of three

judge district courts provides a speedy method for review

of important constitutional questions. Under the decisions

of this Court, there can be no doubt that appellants are

entitled to be admitted to the University of Tennessee.

The injury to them, in terms of loss of time and of potem

tial development, caused by appellees’ illegal conduct is

irremedial. Further procedural delays in vindicating their

rights will merely compound the injury. Review of this

case on the merits by this Court on direct appeal will serve

1 8

to hasten the final determination of appellants’ rights to

attend the University of Tennessee.

For these reasons, we submit, a direct appeal to this

Court should be allowed, and the cause reversed and

remanded with instructions to the court below to enjoin

appellees from enforcing their order, the constitution and

statutes of the state pursuant to which appellants have

been denied admission to the University of Tennessee.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert L. Carter,

Carl A. Cowart,

T hubgood Marshall,

Counsel for Appellants,

Z. A lexander L oobt,

Avon N. W illiams, J r.,

Of Counsel.

(4585)