Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission v. Continental Air Lines Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission v. Continental Air Lines Brief Amici Curiae, 1963. d2e02cf9-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5fcd0ae5-4484-462e-bb74-0f692cc0392a/colorado-anti-discrimination-commission-v-continental-air-lines-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

nsr x h b

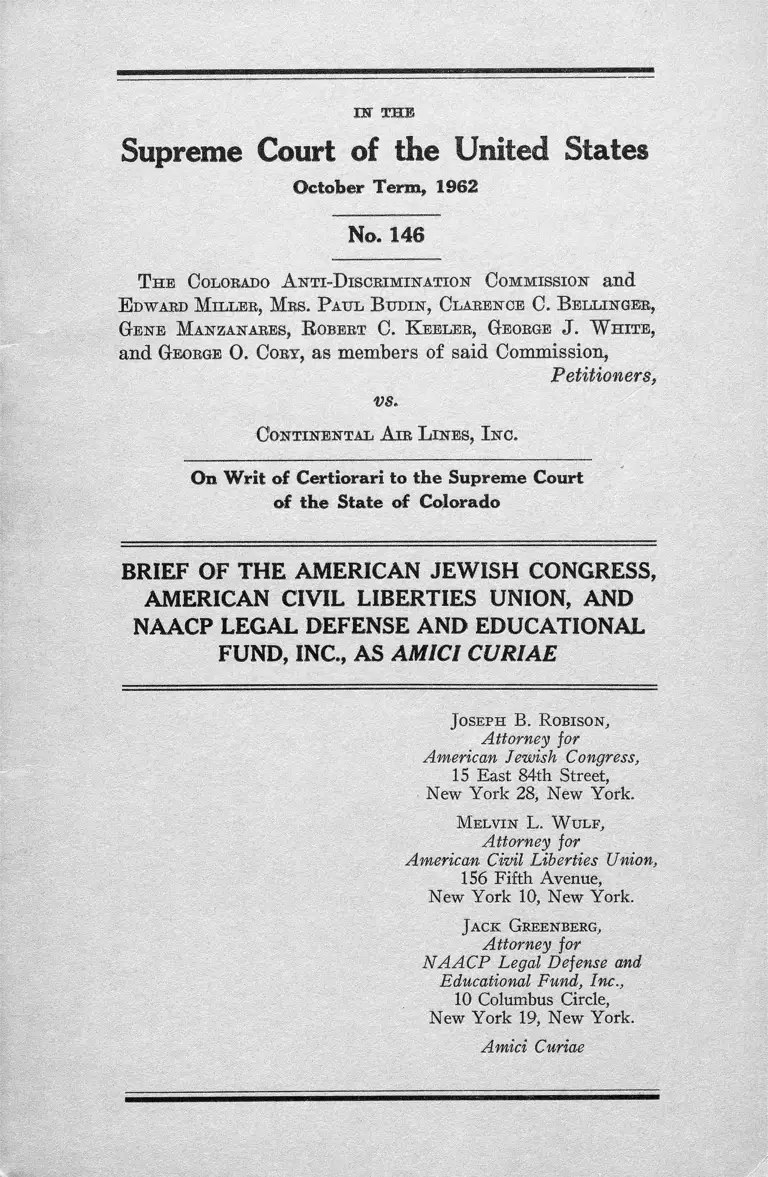

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1962

No. 146

T h e C olorado A n t i-D iscrim in a tio n C om m ission and

E dward M il ia r , M rs . P a u l B u d in , Clarence 0 . B ellin g er ,

G en e M anzan ares , R obert C . K eeler , G eorge J . W h it e ,

and G eorge 0. C orn, as members of said Commission,

Petitioners,

vs.

C o n tin e n ta l A ir L in e s , I n c .

On W rit of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of Colorado

BRIEF OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, AND

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., AS AMICI CURIAE

Joseph B. R obison,

Attorney for

American Jewish Congress,

15 East 84th Street,

New York 28, New York.

M elvin L. W ulf,

Attorney for

American Civil Liberties Union,

156 Fifth Avenue,

New York 10, New York.

Jack Greenberg,

Attorney for

N AACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.,

10 Columbus Circle,

New York 19, New York.

Amici Curiae

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

PAGE

S tatem en t op t h e Case ............................................................ 1

T h e Q uestion to W h ic h t h is B rief is A d d resse d ........ 3

I nterest oe th e A m i c i .............................................................. . 3

S u m m a r y of A rg u m en t ............................................................ 4

A rg u m en t

The United States Constitution does not bar appli

cation to an interstate airline of the Colorado

statute prohibiting discrimination in employment

on the basis of race, religion or national origin 6

I. Congress has not indicated an intent to bar

state regulation of racial discrimination in

employment by persons engaged in inter

state commerce .................................................. 7

A. Congress has accepted state regulation

of this area .............................................. 7

B. No Federal statute precludes state reg

ulation of this area .................................... 14

II. The Colorado fair employment statute

places no burden on interstate commerce 18

A. The non-discrimination requirement

places no burden on employers ............. 18

B. There is no possibility of burdensome

conflicting requirements ........................... 21

III. Accommodation of the competing demands

of the state and national interests requires

a decision upholding the validity of the

Colorado statute ............................................... 26

C on clusion ......................................................................................... 31

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

PAGE

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe R. Co. v. Fair Employ

ment Practice Commission of the State of Cali

fornia, 7 R. R. L. R. 164 (Los Angeles Connty,

Superior Court, decided January 30, 1962) ...... 9

Atlantic Coast Line R. Co. v. Georgia, 234 U. S. 280

(1914) ....................................................................... 16

Baylies v. Curry, 128 111. 287, 21 N. E. 595 (1889) ..... 12

Bolden v. Grand Rapids Operating Corp., 239 Mich.

318, 214 X. W. 241 (1927) ....................................... 12

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen Howard, 343

IT. S. 768 (1952) ................................ 14

Brown v. J. H. Bell Co., 146 Iowa 89, 123 N. W. 231

(1910) ....................................................................... 12

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) ...................... 22

Byams v. N. Y., N. H. & Hartford R. R., 1956 Comm.

Annual Report, p. 57 .............................................. 11

California v. Zook, 336 U. S. 725 (1949) ...................... 17

Chicago, R. I. & P. R. Co. v. Arkansas, 219 U. S., 453

(1911) ....................................................................... 16

Cleveland, etc. Ry. Co. v. People of State of Illinois,

177 IT. S. 514 (1900') .............................................. 19

Commission v. George, 61 Pa. Super. 412 (1915) ...... 12

Conley v. Gibson, 355 H. S. 41 (1957) ......................... 14

Crosswaith v. Bergin, 95 Colo. 241, 35 P. 2d 848 (1934) 12

Darius v. Apostolos, 68 Colo. 323, 190 Pac. 510 (1920) 12

District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., 346

U. S. 100 (1953) ...................................................... 12

Freeman v. Hewit, 329 U. S. 249 (1946) .................... 23

X I

Ill

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 (1962), affirming 142

F. Snpp 707 (M. D., Ala., 1956) ......................... 22

Graham v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and

Enginemen, 338 U. S. 232 (1949) ........................ 14

Hall v. De Cuir, 95 IT. S. 485 (1877) ....................24,25,26

Huron Portland Cement Co. v. Detroit, 362 U. S. 440

(1960) ....................................................................... 6,18

Illinois Cent. B. Co. v. State of Illinois, 163* U. S. 142

(1896) ....................................................................... 19

International Harvester Co. v. Dept, of Treasury, 322

II. S. 340 (1944) ...................................................... 23

McGoldrick v. Berwind-White Co., 309 U. S. 33 (1940) 23

Marshall v. Kansas City, 355 S. W. 2d 877 (Mo., 1962) 12

Messenger v. State, 25 Neb. 674, 41 N. W. 638 (1889) 12

Miller Bros. Co. v. Maryland, 347 U. S. 340 (1954).... 23

Mississippi Railroad Comm. v. Illinois Central R. R.

Co., 203 U. S. 335 (1906) ....................................... 19

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) 22

Missouri Pacific R. Co. v. Norwood, 283 U. S. 249

(1931) ....................................................................... 16

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 (1946) ........ 16, 22, 24, 25

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 (1932) ......................... 26

Pan American World Airways, Inv. 831-59 1960

Comm. Annual Report, p. 90 ................................. 11

Patricia Banks v. Capital Airlines, 1960 Comm. An

nual Report, p. 95 .................................................. 11

People v. King, 110 N. Y. 414, 18 N. E. 245 (1888) .... 12

Pickett v. Kuehan, 323 111. .138, 153 N. E. 667 (1926).... 12

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 IT. S. 88 (1945) 9, 31

Rhone v. Loomis, 74 Minn. 200, 77 N. W. 31 (1898) .... 12

PAGE

XV

Rosa Daly v. British Overseas Airways Corp., 1960

Comm. Annual Report, p. 91.................................. 11

Ruconich v. El A1 Israel Airlines, 1953 Comm. Annual

Report, p. 40 ............................................................ 11

South Covington Ry. v. Covington, 235 U. S. 537

(1915) ............. ......... ................................................ 18

Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 325 U. S. 761

(1945) ..................................................................15,18,26

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co.,, 323 IT. S. 192

(1944) ....................................................................... 14

Valentine v. Brotherhood of Railway & Steamship

Clerks, Lodge 56, 1952 Comm. Annual Report,

p. 34 ........................................................................... 11

Yick Wo v. Hopkins,, 118 IT. S. 356 (1886) .................. 22

Statutes— Federal:

Civil Aeronautics Act

49 U. S. C. Secs. 1301 et seq. ................................. 14

Railway Labor Act (45 U. S. C., Sec. 151, et seq., 181

et seq.) ..................................................................... 14

Statutes— State:

Alaska Comp. Laws Sec. 20-1-3 ........................................ 12

Alaska Comp. Laws Ann., Secs. 43-5-1 to 43-5-10

(Supp. 1957)

PAGE

8

V

Cal. Civ. Code, Sec. 51 .................................................. 12

Cal. Labor Code, Secs. 1410 to 1432, West’s Ann.

Code (1961 Cum. Supp.) ......................................... 8

Colo. Eev. Stats., Sec. 25-2-3 ....................................... 12

Colo. Eev. Stat. Secs. 80-24-1 to 80-24-8 (Supp. 1957) 1, 8

Colo. Eev. Stat., Sec. 5-1-2 ............................................. 17

Conn. Gen. Stat. Secs. 31-122 to 31-128 (1958), as

amended Pub. Act No. 145 (1959) ...................... 7

Conn. Eev. Stat., Sec. 53-35 ......................................... 13

Del. Code Ann. (1960! Supp.), Ch. 7, Sub-Cli. 2, Secs.

710 to 713 ................................................................. 8

D. C. Code 33-604-607 .................................................... 13

Idaho Gen. L. Ann. (1961 Supp.), Ch. 73, Sec. 18-

7302(c) ..................................................................... 12

Idaho Gen. O. Ann. (1961 Supp.), Ch. 73, Sees. 18-7301

to 18-7303 ................................................................. 8

111. Smith-Hurd Ann. Stat., Ch. 48, Secs. 851-866 ..... 8

111. Stats. Ann., Ch. 38, Sec. 125 ................................. 13

Ind. Ann. Stat. (Burn’s 1961 Supp.), Secs. 40-2307

to 40-2317 ................................................................. S

Ind. Stat. Ann.,, Sec. 10-901 ........................................... 13

Iowa Code, Sec. 735.1 .................................................... 13

Kan. Gen. Stats. Ann., Sec. 21-2424 (1949) .............. 13

Kan. Gen. Stat. Ann. 1949 (1957 Supp.) Secs. 44-1001

to 44-1008 ..................................... 8

Maine Eev. Stats.,, Ch. 137, Sec. 50 (1954) .................. 13

Mass. Ann. Laws, Ch. 151B, Secs. 1 to 10 (Supp. 1958) 7

Mass. Ann. Laws, Ch. 272, Sec. 92A ......................... 13

Mass. Gen. Stat. (1860'-66 Supp.), Ch. 277 ................ 12

Mich. Stat. Ann., Secs. 17.458(1) to 17.458(11) ...... 8

Mich. Stats. Ann., Sec. 28.343 ....................................... 13

Minn. Stat. Ann., Sec. 327.09 ....................................... 13

PAGE

Minn. Stat. Ann., Secs. 363.01 to 363.13 (Snpp. 1958) 8

Mo. Ann. Stat. (Vernon Cum. Supp. 1960-1961) Secs.

296.010 to 296.070, 213.010 and 213.030 ................ 8

Mont. Rev. Code, Sec. 64-211 (1957 Supp.) .................. 13

Neb. Rev. Stats., Sec. 20-101 (1943) ........................... 13

N. H. Rev. Stats. Ann., Ch. 354, Sec. 2 ...................... 13

N. J. Rev. Stat., Secs. 18:25-l to 18:25-28 (Supp. 1958) 7

N. J. Stats. Ann., Sec. 10:1-5 ....................................... 13

N. M. Stat. Ann., Secs. 59-4-1 to 59-4-14 (Supp. 1957),

as amended by L. 1959, C. 296 ............................. 7

N. M. Stats. Ann., Sec. 49-8-5....................................... 13

N. J. Rev. Stat., Secs. 18:25-l to 18:25-28 (Supp. 1958) 7

N. Y. Civ. Rights Law, Sec. 40 ................................... 13

New York Exec. Law, Secs. 290-301 (1951) .............. 7

N. D. Century Code Ann. (1961 Supp.), Sec. 12-22-30 13

Ohio Rev. Code, Secs. 4112.01 to 4112.08, 4112.99 ....... 8

Ohio Rev. Code, See. 2901, 35 ....................................... 13

Ore. Rev. Stat., Sec. 30.670 ........................................... 13

Ore. Rev. Stat. 659.010 to 659.115 (Supp. 1957),

659.990 as amended by L. 1959, C. 584 .............. 7

Pa. Stats. Ann., Tit. 18, Sec. 4654 (1945) .................. 13

Pa. Stat, Ann., Tit. 43, Secs. 951 to 963 (Supp. 1958) 8

R. I. Gen. Laws, Sec. 11-24-3 ....................................... 13

R. I. Gen. Laws Ann., Secs. 28-5-1 to 28-5-39 (Supp.

1958) ........................................................................... 7

Vt. Stats. Ann., Sec. 1451 ............................................ 13

Wash. Rev. Code, Sec. 49.60.040 (1956) .................... 13

Wash. Rev. Code Secs. 49.60.010 to 49.60.310 (Supp.

1957), as amended by L. 1959, C. 58

V I

PAGE

7, 28

V I I

Wis, Stat. Ann., Secs. 111.31 to 111.37 (Supp. 1959,

as amended by L. 1959, C. 149) ........................... 8

Wis. Stats. Ann, Sec. 942.04 (1956) ........................... 13

Wyo. Stats. Ann., Sec. 6-83.1.......................................... 13

Miscellaneous:

Elson and Sehanfield, Local Regulation of Discrimi

natory Employment Practices, 56 Yale L. J. 431

(1947) ......... ............................................................. 8

Emerson & Haber, Political and Civil Eights in the

U. S., Vol. II (1958) .............................................. 27

Employment Discrimination, 5 E. E. L. E. 569 (1960) 9

Executive Order No. 8802, 6 Fed. Reg. 3109 (1941) .... 27

Fair Employment Practice Committee, First Report

(1945) .................................................... 27

Fair Employment Practice Committee, Final Report

(1947) '....................................................................... 27

II. Eep. No. 951, 80th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1948) .......... 21, 29

H. Eep. No. 1,165, 81st Cong., 1st Sess. (1949) .......... 29

II. Eep. No. 1370, 87th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1962) ........ 21, 29

Konvitz and Leskes, A Century of Civil Rights,

(1961) ....................................................................... 30

McNamara, Jurisdictional and Commerce Problems,

8 Law and Contemporary Problems 482 (1941) 24

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944) ....................... 26

New York State Commission Against, Discrimination,

Statement before the U. S. Senate Subcommittee

on Labor and Labor Management Eelations, April

16, 1952 ..................................................................... 20

PAGE

V I I I

PAGE

Pennsylvania Fair Employment Practice Act, 17 U.

Pitt. L. Rev. 438 (1956) ......................................... 9

President’s Committee on Civil Rights, Report, To

Secure These Rights (1947) ................................. 29

Sen. Rep. No. 290, 79th Cong., 1st Sess. (1945) ........ 29

Sen. Rep. No. 1,109, 79th Cong. 1st Sess. (1945) ...... 29

Sen. Rep. No. 2,080, 82nd Cong. 2d Sess. (1952) ...... 29

Temporary Commission Against Discrimination, Re

port, Legislative Document (1945) No. 6 ............ 27

The New Pittsburgh Fair Employment Practices Or

dinance, 14 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 604 (1953) ................ 8

The Netv York State Commission Against Discrimi

nation: A New Technique for an Old Problem,

56 Yale L. J. 837 (1947) ....................................... 9

The World Almanac, 1960 ............................................. 22

United States Commission on Civil Rights, Fifty

States Report (1961) ............................................... 30

United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1961 Re

port, Book 3, “ Employment” ............................... 29

Waite, Constitutionality of the Proposed Minnesota

Fair Employment Practices Act, 32 Minn. L.

Rev. 349 (1948) ...................................................... 9

Weaver, Negro, Labor A National Problem (1946).... 27

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1962

No. 146

T h e C olorado A n t i-D iscrim in a tio n C om m ission and

E dward M iller , M rs. P a u l B u d in , C larence C. B ellin g er ,

G ene M anzan ares , R obert C. K eeler , G eorge J . W h it e ,

and G eorge 0. Cory, as members of said Commission,

Petitioners,

vs.

Co n tin e n ta l A ir L in e s , I n c .

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of Colorado

BRIEF OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, AND

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., AS AMICI CURIAE

Statement of the Case

This case arises under the Colorado Anti-Discrimina

tion Act of 1957 (Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. 1953 (1957 Supp.),

Secs. 80-24-1 to 80-24-8). Section 80-24-6(1) and (2) of

that law prohibits discrimination in employment on the

basis of race, creed, color, national origin or ancestry.

2

Under Section 80-24-2(5), this provision is made applicable

to “ every other person employing six or more employees

within the state.”

In April, 1957, Marlon D. Green, a Negro, filed an appli

cation with respondent, Continental Air Lines, Inc., for

employment as a pilot. Green was interviewed by re

spondent and required to fill out an application form that

designated his race. In the succeeding months, a number

of white applicants were hired as pilots but Green was not

hired.

On August 13, 1957, Green filed a complaint with the

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission, petitioner here

in, which administers the Anti-Discrimination Act. The

Commission investigated the complaint, held a hearing and

issued its decision holding that Green was fully qualified

for the position he had applied for and that respondent

had failed to hire him solely because of his race. It re

jected a number of defenses raised by respondent, including

its claim that the anti-discrimination statute could not be

applied to its operations because of their interstate char

acter.

Respondent appealed the Commission’s decision to the

State District Court. Thereafter, further proceedings

were had on the issue of the interstate nature of respond

ent’s operations. Ultimately, the Commission and respond

ent entered into a stipulation that respondent was engaged

in interstate commerce and that the job that Green applied

for involved interstate operations. Thereupon, the District

Court issued its decision setting aside the Commission’s

order solely on the ground that, because respondent was

engaged in the interstate transportation of passengers, the

state Anti-Discrimination Act could not constitutionally

3

apply to its hiring of personnel. The Colorado Supreme

Court affirmed, by a vote of four to three, holding “ that

with reference to interstate carriers the regulation of

racial discrimination is a matter in which there is a ‘ need

for national uniformity,’ and that the states are without

jurisdiction to act in that area.”

The Question to Which this Brief is Addressed

May a state statute prohibiting discrimination in em

ployment because of race, religion or national origin be

constitutionally applied to the employment practices of an

interstate airline!

Interest of the Amici

The American Jewish Congress is an organization of

American Jews established in part “ to help secure and

maintain equality of opportunity for Jews everywhere, and

to safeguard the civil, political, economic and religious

rights of Jews everywhere.” It established its Commis

sion on Law and Social Action in 1945, in part “ to fight

every manifestation of racism and to promote the civil and

political equality of all minorities in America.”

The American Civil Liberties Union is a 42-year old,

private, non-partisan organization engaged solely in the

defense of the Bill of Eights. Its principal interests are

freedom of speech and association, due process of law, and

the equal protection of the laws.

The N. A. A. C. P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. is an organization dedicated to the task of broadening

4

democracy and securing equal justice under the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States. It seeks through legal

redress to assure these rights to all Negroes.

Each of these organizations has in the past been actively

engaged in combatting discrimination in employment based

on race, religion or national origin. They are, therefore,

deeply concerned by the decision of the court below which,

if allowed to stand, would preclude application to a sub

stantial and vital segment of the nation’s economy of the

many state and local fair employment laws that have oper

ated effectively in this country for more than 17 years.

The parties to this proceeding have consented to the

filing of this brief.

Summary of Argument

1. Application of the Colorado statute to respondent’s

operations is not barred by the doctrine of pre-emption be

cause Congress has not indicated any intent to bar such

application.

A. No agency of the Federal Government has moved

to halt application to interstate transportation of the many

state laws prohibiting employment discrimination or even

of the older and more numerous laws against discrimina

tion in transportation facilities. State fair employment

laws have been widely applied to interstate commerce and

interstate transportation.

B. The various federal statutes dealing with interstate

transportation have not been applied to employment dis

crimination. Neither can it be said that the Congressional

5

plan of regulation is so comprehensive as to preclude state

regulation of untouched areas. Finally, even if there is

federal regulation of this area, it does not, by itself, pre

clude state regulation that serves the same policy.

II. The Colorado statute is not a burden on interstate

carriers.

A. No showing has been made that carrier operations

are encumbered by the anti-discrimination requirement.

The 17 years of experience with fair employment laws

shows that employers have operated freely and success

fully under their terms.

B. There is no possibility of subjecting carriers to con

flicting requirements where uniformity is necessary. The

Constitution itself makes it impossible for any state to

adopt a law requiring employment discrimination. More

over, inconsistent regulation of employment practices would

not create the kind of difficulty in operation that has been

held decisive in the case of statutes affecting the actual

operation of railroad trains and other transportation units.

III. If the Colorado statute does impose any burden

on interstate carriers, it is a minimal burden and the na

tional interest in its elimination is far outweighed by the

state interest in the elimination of employment discrimina

tion. The various state anti-bias laws deal with an evil

known to have extensive harmful effects. They are a nor

mal and successful exercise of the police power. No coun

tervailing interest of the Federal Government requires the

result reached below.

6

A R G U M E N T

The United States Constitution does not bar appli

cation to an interstate airline -of the Colorado statute

prohibiting discrimination in employment on the basis

of race, religion or national origin.

The question in this ease is whether a state statute af

fecting an aspect of commerce among the states is rendered

invalid because of a claimed inconsistency with the constitu

tional power of the Federal Government to regulate

interstate commerce. The principles governing the deter

mination of such questions were recently reviewed by this

Court in Huron Portland Cement Co. v. Detroit, 362 U. S.

440 (1960). It was there held that a municipality may

regulate the health aspects of machinery on ships operating

under a federal license in interstate commerce.

Reviewing earlier decisions, this Court described them

as holding that, in the exercise of the police power, “ the

states and their instrumentalities may act, in many areas

of interstate commerce and maritime activities, concurrent

ly with the federal government” (362 U. S. at 442) and

that “ Evenhanded local regulation to effectuate a legiti

mate local public interest is valid unless pre-empted by fed

eral action * * * or unduly burdensome on maritime activi

ties or interstate commerce * * *” (id. at 443). This Court

further said that a Congressional intent to pre-empt state

regulation “ is not to be implied unless the act of Congress,

fairly interpreted, is in actual conflict with the law of the

state” (ibid.).

We submit that application of the Colorado fair employ

ment law to respondent’s operations is not barred by these

principles.

7

I

Congress has not indicated an intent to bar state

regulation of racial discrimination in employment by

persons engaged in interstate commerce.

A. 'Congress has accepted state regulation of this area.

The argument that Congress has acted so as to bar state

regulation of employment discrimination ignores the fact

that state laws on this subject have been in force for many

years and have regularly been applied to interstate car

riers. No branch of the Federal government has taken the

position that those statutes invade an area occupied by

federal regulation.

Since 1945, twenty-two states have adopted laws con

demning discrimination in employment. Nineteen of these

are in the form taken by the Colorado statute, that is, a pro

hibition of such discrimination with provisions for admin

istrative rather than penal enforcement. The first such

laws were adopted in New York and New Jersey in 1945.1 2

Subsequent laws were adopted in Massachusetts in 1946,3 4

Connecticut in 1947,3 New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island

and Washington in 1949,4 Michigan, Minnesota and Penn

1. N. Y. Exec. Law Secs. 290-301 (19 51 ); N. J. Rev. Stat.

Secs. 18:25-1 to 18:25-28 (Supp. 1958).

2. Mass. Ann. Laws, Ch. 151B, Secs. 1 to 10 (Supp. 1958).

3. Conn. Gen. Stat. Secs. 31-122 to 31-128 (1958), as amended,

Pub. Act No. 145 (1959).

4. N. M. Stat. Ann. Secs. 59-4-1 to 59-4-14 (Supp. 1957), as

amended by L. 1959, C. 296; Ore. Rev. Stat. 659.010 to 659.115

(Supp. 1957), 659.990 as amended by L. 1959, C. 584; R. I. Gen.

Laws Ann. Secs. 28-5-1 to 28-5-39 (Supp. 1958); Wash. Rev. Code

Secs. 49.60.010 to 49.60.310 (Supp. 1957), as amended by L. 1959,

C. 58.

8

sylvania in 1955,5 Colorado and Wisconsin in 1957,6 Cali

fornia and Ohio in 19597 and Illinois, Kansas and Missouri

in 1961.8 Alaska adopted such a law in 1953 when it was

still a territory.9 In addition, Delaware in 1960 and Idaho

in 1961 adopted fair employment laws containing penal

rather than administrative sanctions.10 Finally, Indiana,

in 1945, adopted a law condemning employment discrimina

tion hut containing no enforcement provisions.11 Fair

employment ordinances have also been adopted by a num

ber of cities, most of them in states that subsequently en

acted statewide legislation.12

The constitutionality of these statutes as applied to em

ployers generally has never been seriously contested. That

5. Mich. Stat. Ann., Secs. 17.458(1) to 17.458(11); Minn.

Stat. Ann. Secs. 363.01 to 363.13 (Supp. 1958); Pa, Stat. Ann.

Tit. 43, Secs. 951 to 963 (Supp. 1958).

6. Colo. Rev. Stat. Secs. 80-24-1 to 80-24-8 (Supp. 1957) ; Wis.

Stat. Ann. Secs. 111.31 to 111.37 (Supp. 1959), as amended by L.

1959, C. 149.

7. Cal. Labor Code, Secs. 1410 to 1432, W est’s Ann. Code

(1961 Cum. Supp.); Ohio Rev. Code, Secs. 4112.01 to 4112.08,

4112.99.

8. III. Smith-Hurd Ann. Stat., ch. 48, Secs. 851-866; Kan. Gen.

Stat. Ann. 1949 (1957 Supp.), Secs. 44-1001 to 44-1008; Mo. Ann.

Stat. (Vernon Cum. Supps. 1960-1961), Secs. 296.010 to 296.070,

213.010 to 213.030.

9. Alaska Comp. Laws Ann., Secs. 43-5-1 to 43-5-10 (Supp.

1957).

10. Del. Code Ann. (1960 Supp.), Ch. 7, Sub-ch. 2, Secs. 710

to 713; Idaho Gen. L. Ann. (1961 Supp.), Ch. 73, Secs. 18-7301

to 18-7303.

11. Ind. Ann. Stat. (Burn’s 1961 Supp.), Secs. 40-2307 to

40-2317.

12. See Elson and Schanfield, Local Regulation of Discriminatory

Employment Practices, 56 Yale L. J. 431 (1947) ; The New Pitts

burgh Fair Employment Practices Ordinance, 14 U. Pitt. L. Rev.

604, 606-09 (1953).

9

is no doubt due in large part to this Court’s 1945 decision

in Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88, uphold

ing the validity of an earlier New York state law prohibit

ing discrimination by labor unions. It is understandable

that writers on this subject generally agree that fair em

ployment legislation is constitutional. Waite, Constitution

ality of the Proposed Minnesota Fair Employment Prac

tices Act, 32 Minn. L. Rev. 349 (1948); The New York State

Commission Against Discrimination-. A New Technique

for an Old Problem, 56 Yale L-. J. 837, 846-8 (1947); 14 IT.

Pitt., L. Rev., supra, note 12, at 609-11; Pennsylvania Fair

Employment Practice Act, 17 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 438, 442-4

(1956); Employment Discrimination, 5 R. R. L. R. 569,

572-575 (1960).

None of these laws contains any exemption for em

ployers engaged in interstate commerce. They apply to

“ employers” generally. Exemptions are limited to em

ployers of less than a specified number of employees and

religious or other non-profit or distinctly private organi

zations. The various enforcement agencies have admin

istered the laws without regard to whether the employers

involved were engaged in interstate commerce. In addi

tion, the laws have been widely applied to interstate car

riers and only rarely has the issue of federal pre-emption

been raised.13

13. In a few cases, the issue of pre-emption was raised before

an enforcing agency but was not pressed. Aside from the present

case, the only proceeding we know of in which the issue was raised

in court is Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe R. Co. v. Fair Employ

ment Practice Commission of the State of California, 7 R. R. L. R.

164 (Los Angeles County, Superior Court, decided January 30,

1962). In that case, the State Commission had issued an order di

recting a railway company to cease discriminating against an em

1 0

In the preparation of this brief, information on this

point was sought from the state agencies charged with en

forcement of the various state fair employment laws. Re

sponses were received from eleven states, two of which,

Indiana and Missouri, reported that they had handled no

cases involving interstate carriers. The third, in Cali

fornia, reported only the case described in note IB above.

The following information was received from the remain

ing eight states.

The Kansas Commission on Civil Rights, since the adop

tion of the state law in 1961, has docketed one complaint

against an interstate rail carrier. The railroad did not

challenge the Commission’s jurisdiction.14

The Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination

has prosecuted 92 complaints against seven interstate rail

road companies, 18 complaints against 16 interstate truck

ing companies, and 12 complaints against nine interstate

and international air lines.15

The Michigan Fair Employment Practices Commission

has entertained complaints against an interstate bus com

pany, an interstate railroad and Northwest Air Lines. The

Northwest Air Lines complaint is docketed as Claim 598

ployee on the basis of race. The Superior Court set aside the

Commission’s order on the ground that it was not supported by the

evidence. However, it first rejected the railway’s contention that

the Act could not constitutionally be applied to its operations. 7

R. R. L. R. at 165-166.

14. Letter of January 2, 1963 from Carl W . Glatt, Executive Di

rector, Commission on Civil Rights. The letter also noted that,

“ In the eight years prior to July 1, 1961, under the unenforcible

1953 Kansas Act Against Discrimination, the Commission docketed

three formal complaints against interstate carriers, all railroads.”

15. Letter of December 27, 1962 from Walter H. Nolan, Execu

tive Secretary, Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination.

ii

in the Commission’s files. Northwest did not raise any

question over the Commission’s jurisdiction.16

The New York State Commission Against Discrimina

tion has prosecuted the following cases among others.

Valentine v. Brotherhood of Railway and Steamship Clerks,

Lodge 56, 1952 Comm. Annual Report., p. 34; Rmonich v.

El Al Israel Air Lines, 1953 Comm. Annual Report, p. 40;

Byams v. New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad,

1956 Comm. Annual Report, p. 57; Inv. 831-59, Pan Ameri

can World Airways, 1960 Comm. Annual Report, p. 90;

Rosa Daly v. British Overseas Airways Corp., 1960 Comm.

Annual Report, p. 91; Patricia Banks v. Capital Air Lines,

I960 Comm. Annual Report, p. 95.

The Oregon Bureau of Labor has entertained two com

plaints against an interstate air line.17

The Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission has

exercised jurisdiction over seven complaints filed against

several interstate air lines.18

The Washington State Board Against Discrimination

has taken jurisdiction in 13 cases involving interstate car

riers. Three were against the Northern Pacific Railroad,

one was against the Great Northern Railway Company,

six against United Air Lines, two against the Greyhound

Bus Company, and the last was against an interstate truck

ing company.19

16. Information obtained from Edward N. Hodges, III, Execu

tive Director, Michigan Fair Employment Practices Commission.

17. Letter of January 9, 1963 from Mark A. Smith, Administra

tor, Civil Rights Division, Oregon Bureau of Labor.

18. Letter of January 10, 1963 from Elliott M. Shirk, Executive

Director, Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission. Mr. Shirk’s

letter notes that “ our law prevents us from giving specific information

as to name of complainant or respondent and case docket numbers.”

19. Letter of January 9, 1963 from Malcolm B. Pliggins, Execu

tive Secretary, Washington State Board Against Discrimination.

1 2

The Wisconsin Fair Employment Practices Division of

the Industrial Commission has entertained jurisdiction over

several complaints against interstate railroads.20

Congress has accepted application to interstate car

riers not only of fair employment legislation hut also of

other laws prohibiting discrimination. These include laws

dealing with discrimination against passengers—-a matter

directly affecting operation of individual carrier units.

No less than 28 states and the District of Columbia have

enacted laws prohibiting discrimination by enterprises,

variously defined, that solicit the patronage of the general

public. The constitutionality of such laws is well-estab

lished.21

The first of these, which was enacted in Massachusetts

in 1865, specifically applied to any “ public conveyance.” 22

Of the 29 laws now in effect, 22 expressly apply to common

carriers23 * and four are cast in terms broad enough to in-

20. Information obtained from Virginia Heubner, Director, W is

consin Fair Employment Practices Division.

21. District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., 346 U. S.

100 (19 53 ); Darius v. Apostolos, 68 Colo. 323, 190 Pac. 510 (1920) ;

Crosswaith v. Bergin, 95 Colo. 241, 35 P. 2d 848 (19 34 ); Baylies v.

Curry, 128 111. 287, 21 N. E. 595 (1889 ); Pickett v. Kuchan, 323

111. 138, 153 N. E. 667 (1926) ; Bolden v. Grand Rapids Operating

Corp., 239 Mich. 318, 214 N. W . 241 (19 27 ); Brown v. J. H. Bell

Co., 146 Iowa 89, 123 N. W . 231 (19 10 ); Rhone v. Loomis, 74

Minn. 200, 77 N. W . 31 (1898 ); Marshall v. Kansas City, 355 S. W .

2d 877 (M o., 1962) ; Messenger v. State, 25 Neb. 674, 41 N. W .

638 (18 89 ); People v. King, 110 N. Y . 414, 18 N. E. 245 (1888) ;

Commission v. George, 61 Pa. Super. 412 (1915).

22. Gen. Stat. (1860-66 Supp.), Ch. 277.

23. Alaska Com. Laws, Sec. 20-1-3, “ Transportation compa

nies” ; Cal. Civ. Code, Sec. 51, “ Public conveyances and all other

places of public accommodation or amusement” ; Colo. Rev. Stats.,

Sec. 25-2-3, “ Public conveyances on land or water” ; Idaho Gen. L.

Ann. (1961 Supp.), Ch. 73, Sec. 18-7302(e), “ Public conveyance

13

elude common carriers.24 The remaining three appear to

exclude interstate carriers.25

or transportation on land, water or in the air, including the stations

and terminals thereof and the garaging of vehicles” ; III. Stats. Ann.,

Ch. 38, Sec. 125, “ Railroads, omnibuses, stages, street cars, boats,

funeral hearses, and public conveyances on land and water” ; Ind.

Stat. Ann., Sec. 10-901, “ Public conveyances on land and water” ;

Iowa Code, Sec. 735.1, “ Public conveyances” ; Maine Rev. Stats.,

Ch. 137, Sec. 50 (1954), “ Public conveyances on land or water” ;

Mass. Ann. Law, Ch. 272, Sec. 92A, “ A carrier, conveyance or ele

vator for the transportation of persons, whether operated on land,

water or in the air, and the stations, terminals and facilities appur

tenant thereto” ; Mich. Stats. Ann., Sec. 28.343, “ Public conveyances

on land and water” ; Minn. Stats. Ann., Sec. 327.09, “ Public convey

ances” ; Neb. Rev. Stats., Sec. 20-101 (1943), “ Public conveyances” ;

N . H. Rev. Stats. Ann., Ch. 354, Sec. 2, “ Public conveyance on land

or water” ; N. J. Stats. Ann., Sec. 10 :l-5, “ Any garage, any public

conveyance operated on land or water and stations and terminals

thereof” ; N. M. Stats. Ann., Sec. 49-8-5, “ All public conveyances

operated on land, water or in the air as well as the stations and

terminals thereof” ; N. Y. Civ. Rights Law, Sec. 40, “ Garages, all

public conveyances operated on land or water, as well as the stations

and terminals thereof” ; N. D. Century Code Ann. (1961 Supp.),

Sec. 12-22-30, “ Public conveyances” ; Ohio Rev. Code, Sec. 2901,

35, “ Public conveyance by air, land or water” ; Pa. Stats. Ann., Tit.

18, Sec. 4654 (1945), “ Garages, and all public conveyances operated

on land or water as well as the stations and terminals thereof” ; R. I.

Gen. Laws, Sec. 11-24-3, “ All public conveyances, operated on land,

water or in the air as well as the stations and terminals thereof” ;

Wash. Rev. Code, Sec. 49.60.040 (1956), “ Public conveyance or

transportation on land, water, or in the air, including the stations and

terminals thereof and the garaging of vehicles” ; Wis. Stats. Ann.,

Sec. 942.04 (1956), “ Public conveyances.”

24. Conn. Rev. Stat., Sec. 53-35, refers to “ every place of public

accommodation,” and place of public accommodation is defined as

“ any establishment * * * which caters or offers its services or facili

ties or goods to the general public * * *” ; Mont. Rev. Code, Sec.

64-211 (1957 Supp.), “ Public accommodation or amusement” ; Vt.

Stats. Ann., Sec. 1451, “ Any establishment which caters or offers

its services or facilities or goods to the general public” ; Wyo. Stats-.

Ann., Sec. 6-83.1, “ All accommodations * * * public in nature, or

which invite the patronage of the public.”

25. D. C. Code 33-604-607, applies only to eating places; Kan.

Gen. Stats. Ann., Sec. 21-2424 (1949), applies to any steamboat,

railroad, stage coach, omnibus, streetcar, or any means of public

carriage for persons or freight within the state-, Ore. Rev. Stats.,

Sec. 30.670.

14

B, No Federal statute precludes state

regulation of this area.

The Colorado Supreme Court, in its decision in this case,

did not consider the question of pre-emption but confined

its decision to the argument, discussed in Points II and

III below, that the challenged state law constituted a burden

on interstate commerce. However, the trial court, whose

decision the state Supreme Court commented on favorably,

considered the pre-emption argument in detail and con

cluded that certain federal statutes indicated a clear Con

gressional intention to occupy the field of air transportation

so completely as to exclude state regulation of any kind.

This argument has two aspects: first, that the Federal

Government has specifically dealt with racial discrimina

tion in employment by interstate air carriers, and, second,

that, even if it has not, its regulation of such carriers is so

extensive as to bar any state regulation even of matters

not covered by federal statutes. We submit that neither

argument is supported by the decisions of this Court.

The trial court held that employment discrimination by

interstate air carriers is prohibited by the Railway Labor

Act (45 U. S. C. Sec. 151, et seq., 181 et seq.) as well as the

Civil Aeronautics Act. 49 IT. S. C. Secs. 1301 et seq., for

merly 49 IT. S. C. Secs. 401 et seq.

The Railway Labor Act and the decisions of this Court

thereunder deal with discrimination by unions. Steele v.

Louisville <& Nashville R. Co., 323 IT. S. 192 (1944); Graham

v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, 338

IT. S. 232 (1949); Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v.

Howard, 343 IT. S. 768 (1952); Conley v. Gibson, 355 IT. S.

41 (1957). No agency of the Federal Government adminis

tering the Railway Labor Act had suggested or taken any

15

action establishing that the statute deals with the discrimi

natory practice reached here under the Colorado law, i.e.,

discrimination by an employer independent of action by a

union.

The provision in the Civil Aeronautics Act primarily

relied on is 49 U. S. C. Sec. 1374(b) (formerly Sec. 484(b)),

which provides as follows:

(b) No air carrier or foreign air carrier shall make,

give, or cause any undue or unreasonable preference or

advantage to any particular person, port, locality, or

description of traffic in air transportation in any re

spect whatsoever or subject any particular person,

port, locality, or description of traffic in air transporta

tion to any unjust discrimination or any undue or

unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any respect

whatsoever.

The undersigned organizations do not, of course, take

the position that this section cannot be invoked to prevent

employment discrimination by air carriers. However, we

are compelled to note that it has never been so interpreted

or applied and its application to this area is at least an

unresolved issue. This Court could hardly nullify applica

tion of the Colorado law to respondent on the ground of

preemption without resolving that open question. Since

there is at least doubt on this point, this Court, without

resolving the issue, should uphold the state statute since,

as this Court has repeatedly held, “ Congress * * * will not

be deemed to have intended to strike down a statute de

signed to protect the health and safety of the public unless

its purpose to do so is clearly manifested.” Southern

Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 325 U. S. 761, 766 (1945), and cases

there cited.

16

I f employment discrimination by interstate air carriers

is not prohibited by federal legislation, the remaining ques

tion is whether Congress has so occupied the general field

as to bar state regulation of that specific subject. We sub

mit that the lower court’s affirmative answer to that ques

tion is unsound. If it were sound, all state laws dealing in

any way with air, railroad, motor or other forms of inter

state transportation would be invalidated.

Surely, no aspect of our economy is so thoroughly regu

lated by Congress as the interstate railroads. Yet this

Court has upheld even such detailed state regulation of rail

operations as statutes requiring full crews on trains.

Chicago, R. I. & P. R. Co. v. Arkansas, 219 IT. S. 453 (1911);

Missouri Pacific R. Co. v. Norwood, 283 U. S. 249 (1931).

In referring to these statutes as an example of laws not

barred by the Congressional power over interstate com

merce, this Court has described them as “ statutes dealing

with employment of labor” (Morgan v. Virginia, 328 IT. S.

373, 379n (1946)), a description plainly applicable to the

statute here involved.

The courts below apparently believed that federal regu

lation of some aspects of interstate transportation by air

precludes state regulation of all other aspects. Their error

is revealed by this Court’s decision in Atlantic Coast Line

R. Co. v. Georgia, 234 IT. S. 280 (1914), where a similar

argument was rejected even within the narrow area of

safety regulations. It was there argued that a state statute,

based on safety considerations, regulating the strength of

locomotive headlights was barred by federal laws “ relating

to power driving-wheel brakes for locomotives, grabirons,

automatic couplers and height of drawbars,” as well as a

number of other statutes and regulations dealing with

17

safety (234 U. S. at 293). Justice (later Chief Justice)

Hughes, speaking for a unanimous Court, disposed of this

contention briefly, saying “ But it is manifest that none

of these acts provide regulations for locomotive headlights”

(■ibid.; emphasis supplied).

Finally, even if it appears that the Federal Government

has regulated the very conduct here involved, that fact by

itself would not be decisive. In California v. Zook, 336 U. S.

725 (1949), this Court expressly rejected the view that the

mere fact of parallel federal and state regulation nullifies

the latter. It held that there must be some additional show

ing of Congressional intent to exclude state action. Ac

cordingly, the states have duplicated federal regulation in

interstate transportation in a number of ways, one of which

is revealed in the Colorado statute referred to in the deci

sion below, which makes it a state crime to operate aircraft

without the appropriate federal license and registration.

Colo. Rev. Stat,, Sec. 5-1-2. Although the court below

cited this statute as showing state deferment to federal

regulation, it actually shows concurrent regulation by the

state and Federal Governments to enforce a common policy.

We submit that the decisions of this Court establish that

there is ample room for state regulation of employment

discrimination by interstate air carriers. Nothing in the

pre-emption doctrine requires the conclusion that Congress

has barred state regulation of employment discrimination

because it has found it necessary to regulate other unrelated

aspects of air transportation.

18

II

The Colorado fair employment statute places no

burden on interstate commerce.

Independent of the issue of pre-emption, it can be

argued that the Colorado statute may not be applied to

respondent if such application would be “ burdensome * * #

on interstate commerce” (Huron case, supra, 362 XL S. at

443). We submit that there is no basis for arguing, and

that respondent has not shown, that a fair employment law

places a burden on the employers to which it applies or

that there is any danger that air carriers will be subjected

to conflicting regulations.

A. The non-discrimination requirement places

no burden on employers.

At the outset, it should be noted that a burden on inter

state commerce will not be found lightly. In the cases in

which this Court has held state laws unduly burdensome,

there has been an impressive record spelling out the man

ner in which the statute made operation of the carriers’

facilities more difficult or at least more expensive.

Thus, in Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 325 U. S. 761

(1945), this Court discussed in detail the effect of a state

statute limiting the length of railroad trains (325 IT. S. at

771-3). It noted that the statute had an “ admittedly ad

verse effect on the operation of interstate trains” {id. at

764) and concluded that it placed a “ serious burden” on

railroad operations {id. at 773). See also South Covington

Ry. v. Covington, 235 U. S. 537, 547 (1915); Illinois Cent.

19

R. Co. v. State of Illinois, 163 U. S. 142, 153 (1896); Cleve

land, etc. Ry. Co. v. People of State of Illinois, 177 U. S.

514, 521 (1900); Mississippi Railroad Comm. v. Illinois Cen

tral R. R. Co., 203 IT. S. 335, 345, 346 (1906).

No such showing1 is made here. Respondent has not

shown that compliance with the fair employment law would

make the hiring of personnel more difficult. Plainly, it can

not, since the purpose and effect of such legislation is to re

move a restraint on the employment process. Because of

the law, respondent and all competing carriers have a larger

source of manpower supply, free of artificial limitations

based on race.

This is no longer a matter of speculation. As we have

noted, fair employment laws have been in effect for more

than 17 years. It is possible to consider their operation on

the basis of actual experience. If they were burdensome

to the employers affected, respondent would be able to pro

duce evidence to that effect. It has not done so.

The fact is, on the contrary, that employers have oper

ated freely and successfully in fair employment states.

Many employers that have conformed to the requirements

of the law have been outspoken in its support.

Early in 1950, Business Week asked employers in New

Jersey, Connecticut and New York their views of the fair

employment laws in their states. The magazine found that,

while some employers still believed the laws unnecessary,

even those employers who had opposed them wTere no long

er actively hostile. All eleven firms surveyed reported to

Business Week that the laws did not interfere with their

right to hire the most competent employees they could find,

and concluded that the laws were functioning without any

serious problems. (Business Week, Feb. 25, 1950)

20

Even more favorable testimony was produced by the

commission enforcing tbe New York State law in a state

ment to a Subcommittee of tbe United States Senate Com

mittee on Labor and Public Welfare. (Statement of the

New York State Commission Against Discrimination before

the U. S. Senate Subcommittee on Labor and Labor Man

agement Relations, April 16, 1952, pp. 11-12.) A “ repre

sentative of an association of retail merchants” testified

that the law had simple requirements that imposed no hard

ship upon an employer. A “ financial district observer”

noted that the law had had ‘ ‘ a fine effect upon the employ

ment practices of banks and brokerage houses * * * ” A

representative of a “ public utility company” thanked the

New York agency for its fair consideration of the com

pany’s employment practices and concluded that the

agency’s work had been of “ definite value to us in apprais

ing our personnel methods and practices.”

The New York State Commission Against Discrimina

tion (now called the New York State Commission for Hu

man Rights) has also publicized statements from individual

employers on the impact of the state anti-discrimination

law upon them. The executive vice president of the New

York Board of Trade said:

I am one of those who was against the anti-discrimina

tion law when it was first introduced and worked hard

to prevent its passage. Now after six years of opera

tion particularly as it is so ably enforced, I find that

our fears have not been realized, but much more gen

uine progress has been achieved.

The executive vice-president of the Commerce and In

dustry Association of New York State, in March 1953, said:

21

It is our observation that the New York State Anti-

Discrimination program has in general functioned and

has met with a wide degree of acceptance considering

the sensitive area in which it operates. The State Com

mission Against Discrimination has approached its

task with intelligence and there has been due emphasis

on the role of education in effecting the purposes of the

program. We are aware of no concerted employer op

position to the law and only spotty complaints have

come to our attention. There are many illustrations

of employer endorsement of and cooperation with the

program.

The Rhode Island Commission for Fair Employment

Practices has stated that many employers on the basis of

their experience have been convinced of the groundlessness

of their early fears of anti-discrimination laws and the Fair

Employment Practices Commissions of Philadelphia and

Minneapolis have also published reports confirming the

view that employers believe now that fair employment

practices acts have not only not burdened them but have in

fact benefited them. (Reported in Staff Report to the Sub

committee on Labor and Labor Management Relations of

the U. S. Senate, Committee Print, 82nd Cong., 2d Sess.,

p. 19 (1952). See also H. Rep. No. 1370, 87th Cong., 2d

Sess., p. 5 (1962)).

B. There is no possibility of burdensome

conflicting requirements.

Respondent argues, however, that its operations may

be burdened by the Colorado law because it may be sub

jected to conflicting regulations in the various states in

which it operates. In this connection, it relies on the well-

established principle that state regulations may be found

2 2

to be unduly burdensome and bence unconstitutional if they

result in inconsistency “ in matters where uniformity is

necessary * * Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 377

(1946). That argument fails here because respondent

cannot show either a possibility of inconsistency or a need

for uniformity.

As we have noted above, fair employment laws ap

plicable to common carriers are now in effect in 22 states.

These states include 63.1% of the total population of the

nation and most of its industrial areas.26 More important,

there are no state laws requiring discrimination; and it is

now entirely clear that no state can constitutionally adopt

a law requiring discrimination by private parties. See, e.g.,

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 IT. S. 60 (1917); Gayle v. Browder,

352 IT. S. 903 (1962), affirming 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D.,

Ala., 1956).

Hence, this case does not reveal the vice that invali

dated state regulation of interstate or foreign commerce

in other cases, namely, that, if the regulations were sus

tained, other states could with equal right impose con

flicting and diverse regulations that would burden inter

state carriers. The Constitution itself, through the Equal

Protection Clause, insures against a state requirement of

discrimination in employment on account of race. The

Colorado requirement of fair employment carries out the

constitutional “ pledge of the protection of equal laws.”

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 IT. S. 356, 369 (1886); Missouri

ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 IT. S. 337, 350 (1938). It can

not, therefore, be regarded as imposing an undue burden

on interstate commerce.

26. The population of the twenty-two states in the 1960 census

(The W orld Almanac, 1960, p. 255) was 113,232,789. The total

United States population was 179,323,175.

23

Our contention that state regulation of interstate com

merce may be held to be free of burdensome effects, in

view of the restrictive effects of other provisions of the

Constitution, is not new. The interplay between the Com

merce Clause and the Fourteenth Amendment has been an

important factor in sustaining state regulation of inter

state commerce in the area of taxation. McGoldrick v.

Berwind-White Co., 309 U. S. 33 (1940); International

Harvester Co. v. Dept, of Treasury, 322 U. 8. 340 (1944) ;

Miller Bros. Co. v. Maryland, 347 IT. S. 340 (1954). In

determining whether the validation of a state tax would

subject interstate commerce to a risk of undue cumulative

tax burdens, this Court has considered the effect of the

Due Process Clause in restricting the taxing powers of

other states. A basic consideration in the sustaining of

certain state tax levies affecting interstate commerce has

been the inability of other states to tax the same transac

tion, not because of the Commerce Clause, but because of

the restrictions on extraterritorial taxation imposed on

the states by the Due Process Clause.

This interrelation between the Commerce Clause and the

Due Process Clause was illuminated in International Har

vester Co. v. Department of Treasury et ad., supra; and

Freeman v. Ilewit, 329 U. 8. 249 (1946). In the latter case,

Justice Rutledge said (at p. 271):

Selection of a local incident for pegging the tax

has two functions relevant to determination of its

validity. One is to make plain that the state has suffi

cient factual connections with the transaction to com

ply with due process requirements. The other is to

act as a safeguard, to some extent, against repetition

of the same or a similar tax by another state. (Our

emphasis; footnote omitted.)

24

See also McNamara, Jurisdictional and Commerce Prob

lems, 8 Law and Contemporary Problems 482 (1941).

The principle applied in the tax cases affecting inter

state commerce is, we believe, applicable to the instant case.

In the cases referred to, the Due Process Clause made it

impossible for other states to add to the burden of the tax

on the transaction under attack, with the result that the

levies were sustained. So, here, the Equal Protection

Clause precludes diverse or conflicting state action respect

ing employment. Consequently, as in the tax cases, the

regulation is valid, for in the absence of the risk of an

undue burden on commerce, the statute is a proper exer

cise of the state’s police power.

Finally, respondent has not shown that any burden will

be placed on its operation by application of inconsistent

laws regarding employment. The Colorado statute pro

hibits discrimination in employment and does not affect in

any way the operation of respondent’s planes. The con

tract of employment is made at one place and, of course,

is subject to the law of that place and only that place.

Once hired, an employee can be sent to any part of the

country as respondent sees fit.

There is no need here, as there was in Morgan, supra,

and in Hall v. De Cuir, 95 U. S. 485 (1877), for the carrier

to make changes in its transportation units each time they

cross a state line. There is no need for the crew of an

interstate plane to interrupt a trip in order to comply with

changed rules. In short, there is no burden, undue or

otherwise.

Respondent and the court below placed their chief re

liance on this Court’s decisions in Morgan and Hall. We

submit that those cases are clearly distinguishable since

25

they deal with operations rather than employment. There

is a manifest difference, not discussed by the court below,

between what happens day-to-day in the operation of planes

and trains and what happens when a carrier takes on per

sonnel at its home office. In one case, conflicting regula

tions directly affect the operation of the transportation

units; they compel extra work on the part of the operating

crews and sometimes the use of extra equipment and the

halting of trips at state lines. No such problems are posed

by inconsistent regulation of -employment; no other prob

lems are plausibly suggested. No showing has or can be

made of the “ transportation difficulties” that were decisive

in Morgan. 328 U. S. at 385-6.

Respondent has tried to make the rulings in Morgan

and Hall fit a situation to which they have no logical appli

cation. It has attempted to create the impression that

those cases dealt generally with the whole problem of racial

discrimination in interstate transportation in all its forms.

In fact, however, they dealt at most with the handling of

passengers in interstate transportation units. Neither

their rationale nor their factual basis applies to the hiring

of employees.

Moreover, in Morgan, there was not- only the possibility

but the actual fact of inconsistent regulations, as this Court

took pains to show (328 U. S. at 381-383). The possibility

of inconsistent regulations also existed in the Hall case at

the time it was decided. But whatever validity Hall may

have had up to 1954, it is now completely undermined by

the decisions of this Court condemning state segregation

laws, as we have shown above. We therefore respectfully

suggest that this case provides an appropriate occasion

for overruling Hall expressly, at least to the extent that it

26

holds that a law prohibiting discrimination may obstruct

interstate commerce. There is no basis in law or practical

experience for a holding that a law requiring equal treat

ment is burdensome. Such a holding, we believe, is funda

mentally at odds with the equalitarian concepts of the Con

stitution. It might as well he argued that “ the mandates

of liberty and equality that hind officials everywhere”

{Nixon v. Condon, 286 IT. S. 73, 88 (1932)) place a “ bur

den” on government—that the prohibition of racial segre

gation in public schools is a “ burden” on education.

Since the rationale of Hall v. DeCuir has been destroyed,

it is time that the ambiguity caused by its continuing vital

ity be eliminated by this Court.

I l l

Accommodation of the competing demands of the

state and national interests requires a decision up

holding the validity of the Colorado statute.

If it is assumed, contrary to what was said in the previ

ous point, that the Colorado fair employment law does place

some burden on interstate commerce, the national interest

in the elimination of that burden must he weighed against

the state interest sought to be served by the statute. Thus,

in Southern Pacific, supra, this Court measured “ the rela

tive weights of the state and national interests. * * *” (325

U. S. at 770). As already noted, it found first that the

challenged state law placed a substantial, palpable burden

on interstate carriers. It then went on to consider in detail

the evidence relevant to the state need served by the statute

and found that the statute, “ viewed as a safety measure,

affords at most slight and dubious advantage. * * (325* *

27

U. S. at 779). The public purpose served by the Colorado

fair employment law, we submit, is far more substantial.

Both the existence and the harmful effects of discrimi

nation in employment against minority groups have been

fully documented. See, e.g., Myrdal, An American Dilem

ma, Chaps. 9-19 (1944); Weaver, Negro Labor, A National

Problem, pp. 16-97 (1946); Emerson & Haber, Political and

Civil Rights in the United States, Vol. II, pp. 1422-5 (1958).

The first wartime executive order dealing with discrimina

tion by defense contractors, issued by President Roosevelt

in 1941, found that “ available and needed workers have

been barred from employment in industries engaged in

defense production solely because of consideration of race,

creed, color, or national origin, to the detriment of work

ers’ morale and of national unity.” Executive Order No.

8802, 6 Fed. Reg. 3109 (1941). The Fair Employment

Practice Committee established under that order found

extensive evidence of discrimination. Fair Employment

Practice Committee, First Report, pp. 85-101 (1945); Final

Report, pp. 41-97 (1947).

It was also during the period of World War II that the

New York State Legislature established a Temporary Com

mission Against Discrimination, headed by State Senator

Irving M. Ives, later a United States Senator, to investigate

this pressing problem. On the basis of extended hearings,

the Temporary Commission reached the following conclu

sion (Report, Legislative Document (1945) No. 6, at pp.

48-49):

Discrimination in opportunity for employment is the

most injurious and un-American of all the forms of dis

crimination. To deprive any person of the chance to

make a living is to violate one of the most fundamental

of human rights. Moreover, such discrimination is op

28

posed to every sound principle of public policy and

makes against loyalty to democratic institutions. * * *

Social injustice always balances its books with red ink.

Accordingly, the Commission recommended the adop

tion of a state law prohibiting discrimination in employment

and the establishment of an administrative agency to en

force its provisions. In the same year that the Commission

issued its Report, the New York State Legislature adopted

its fair employment law, based on the proposed bill sub

mitted by the Temporary Commission (Report, pp. 77-82).

The Legislature expressly found, in that statute, that

“ practices of discrimination * * * because of race, creed,

color or national origin are a matter of state concern, that

such discrimination threatens not only the rights and prop

er privileges of its inhabitants but menaces the institutions

and foundations of a free democratic state.” New York

Exec. Law, Sec. 290.

Similar findings have been made by many of the other

states that have adopted fair employment legislation.27 In

one of the most recent statutes, the Illinois Legislature

found that “ * * * denial of equal employment opportunity

because of race, color, religion, national origin or ancestry

with consequent failure to utilize the productive capacities

of individuals to the fullest extent deprives a portion of the

population of the State of earnings necessary to maintain

a reasonable standard of living, thereby tending to cause

resort to public charity and may cause conflicts and contro

versies, resulting in grave injury to the public safety,

health and welfare.”

27. See the Alaska, California, Kansas, Minnesota, New Jersey,

New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Washington and W is

consin. statutes cited in notes 1 to 9, supra.

29

Federal government agencies have reached the same

conclusion. The President’s Committee on Civil Rights

found extensive evidence of discrimination in employment

and its evil effects in its 1947 Report, To Secure These

Rights, pp. 53-62 (1947). Thirteen years later, the United

States Commission on Civil Rights issued a 246-page report

dealing with this problem. 1961 Report, Booh 3, “ Employ

ment.”

The widespread existence of employment discrimination

has also been found by Congressional committees studying

the subject, Sen. Rep. No. 2,080, 82nd Cong. 2d Sess., pp.

3-4 (1952); H. Rep. No. 1,165, 81st Cong. 1st Sess., pp. 2-8

(1949); H. Rep. No. 951, 80th Cong. 2d Sess., pp. 2-6 (1948);

Sen. Rep. No. 290, 79th Cong. 1st Sess., p. 3 (1945); Sen.

Rep. No. 1,109, 79th Cong. 1st Sess., pp. 2-3 (1945). Most

recently, the House Committee on Education and Labor, in

a report on a proposed federal fair employment law, stated

(H. Rep. No. 1370, 87th Cong. 2d Sess. pp. 1, 2 (1962)):

The conclusion inescapably to be drawn from 98 wit

nesses in 12 days of hearings, held in various sections

of the country as well as in Washington, and from

many statements filed without oral testimony, is that

in all likelihood fully 50 percent of the people of the

United States in search of employment suffer some

kind of job opportunity discrimination because of their

race, religion, color, national origin, ancestry, or age.

It should be made clear that the evidence poured in

from all parts of the Nation—East, West, North, and

South. # * *

# # *

Arbitrary denial of equal employment opportunity un

questionably contributes to our current staggering wel

fare assistance costs * * *

30

Fair employment legislation of the kind adopted in

Colorado is a reasonable and effective way of dealing with

this well-documented evil. In state after state that has

adopted such legislation, its beneficial effect has been real

ized. Thus, in ten of the states having a number of years

of experience with fair employment laws, the State Ad

visory Committees to the United States Commission on

Civil Eights reported in 1961 that beneficial effects had

been achieved. United States Civil Bights Commission,

Fifty States Report, pp. 56, 80, 287, 297, 405-8, 429-31, 530,

545, 556-7, 631-4 (1961). See also Konvitz and Leskes, A

Century of Civil Rights, pp. 222-224 (1961).

We submit that the Colorado Legislature could reason

ably conclude that employment discrimination based on

race, religion and national origin exists, that it has harmful

effects of the kind normally dealt with under the police

power and that the legislation here challenged was a reason

able and effective method of dealing with it. Hence, the

“ state interest” is substantial. The “ national interest” ,

in barring state laws prohibiting employment discrimina

tion by interstate carriers, as we have seen, is at best mini

mal and, in fact, we believe, non-existent. Indeed, consti

tutional principles as well as practical considerations com

pel the conclusion that the national interest is advanced

rather than hindered by elimination of discrimination by

interstate air carriers. There is therefore no basis for

holding that preservation of the federal-state relationship

requires the result reached below.

31

Conclusion

Fair employment laws are a conventional and widely

accepted exercise of the police power of the states. They

have been applied to interstate carriers for over a decade

without hampering interstate transportation. No national

interest, no constitutional principle, no decision of this

Court requires that Continental Air Lines be given a

license to operate in defiance of the declared policy of Colo

rado, under which the state has “ put its authority behind

one of the cherished aims of American feeling by forbidding

indulgence in racial or religious prejudice to another’s

hurt.” Frankfurter, J., concurring in Railway Mail Asso

ciation v. Corsi, supra, 326 U. S. at 98. The decision of

the Colorado Supreme Court should therefore be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Joseph B. R obison,

Attorney for

American Jewish Congress,

15 East 84th Street,

New York 28, New York.

M elvin L. W ulf,

Attorney for

American Civil Liberties Union,

156 Fifth Avenue,

New York 10, New York.

Jack Greenberg,

Attorney for

N AACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.,

10 Columbus Circle,

New York 19, New York.

Amici Curiae

January, 1963

•3'’i®*"307 BAR PRESS, Inc., 54 Lafayette Street, New York 13 — W A 5-3432

( 223)