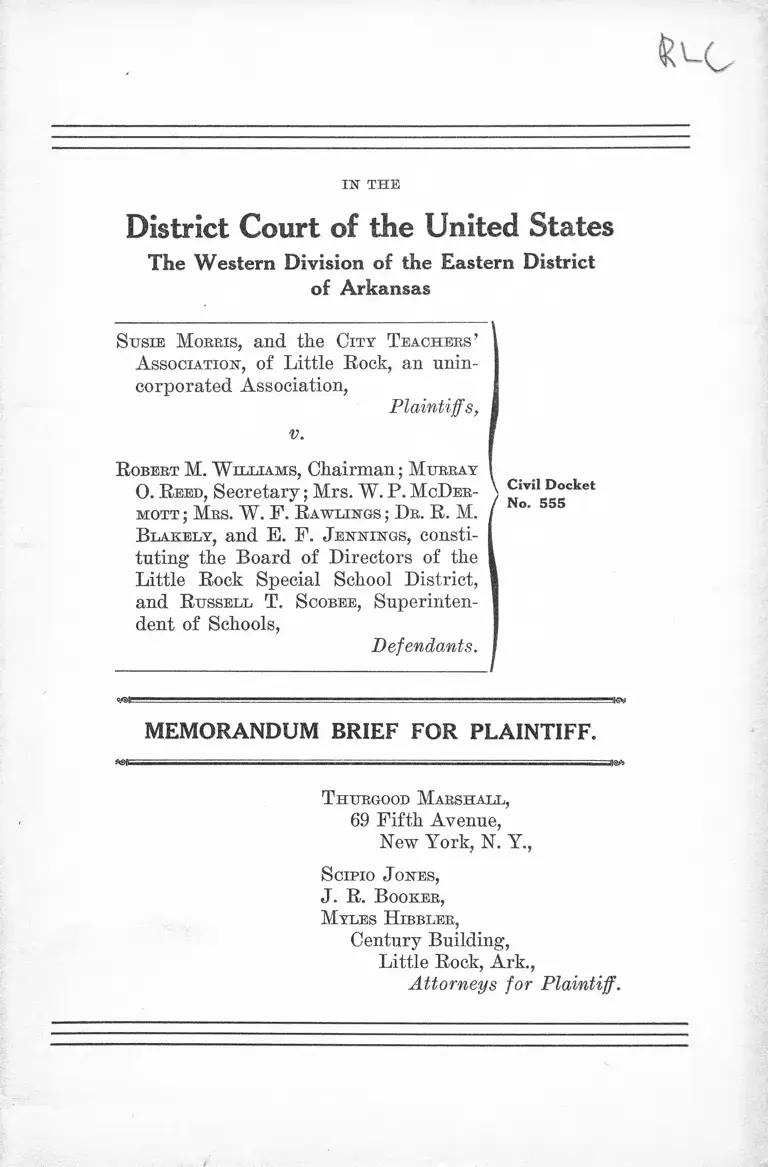

Morris v. Williams Memorandum Brief for Plaintiff

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1945

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Morris v. Williams Memorandum Brief for Plaintiff, 1945. eeeba6c6-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5fd970fe-4018-4c6a-9453-dc30b684cf6d/morris-v-williams-memorandum-brief-for-plaintiff. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

District Court of the United States

The Western Division of the Eastern District

of Arkansas

S usie M orris, and the C it y T eachers ’ 1

A ssociation, of Little Rock, an unin

corporated Association,

Plaintiffs,

v.

R obert M. W illiam s , Chairman; M urray 1

0. R eed, Secretary; Mrs. W. P. M cD er- \ Civ.l Doekct

m ott ; M rs. W. F. R aw lings ; D r . R. M. / °’

B lak ely , and E. F. J en n in g s , consti- I

tuting the Board of Directors of the I

Little Rock Special School District, 1

and R ussell T. S cobee, Superinten- I

dent of Schools,

Defendants. I

M EM ORANDUM BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF.

T hurgood M arshall.,

69 Fifth Avenue,

New York, N. Y.,

S cipio J ones,

J . R. B ooker,

M yles H ibbler,

Century Building,

Little Rock, Ark.,

Attorneys for Plaintiff.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

PAGE

P art O n e :

Statement of the Case_____________________________ 1

P art T w o :

Statement of Facts_______ 9

Method of Fixing Salaries_______________________ 9

New Teachers______________________________ -____ 10

Old Teachers ____________________________________ 13

Policy of Board in Past___________________________ 14

Bonus Payments _________________________________ 16

P art T hree— A rgument :

I. Payment of less salary to Negro public school

teachers because of race is in violation of Four

teenth Amendment ____________________________ 18

II. The policy, custom and usage of fixing salaries of

public school teachers in Little Rock violates the

Fourteenth Amendment________________________ 22

A. General policy of defendants-._____________ 23

Cultural Background ___________________ 23

Economic Theory ______________________ 24

B. Minimum salaries for new teachers________ 25

C. Salaries of older teachers and flat increases 30

Blanket Increases on Basis of Race_____ 32

11

PAGE

D. The discriminatory policy of distributing

supplementary salary payments on an un

equal basis because of race_______________ 33

III. The rating sheets offered in evidence by defen

dants should not have been admitted in evidence 35

IV. The composite rating sheets are entitled to no

weight in determining whether the policy, custom

and usage of fixing salaries in Little Eock is

based on race__________________________________ 38

How the Eatings Were Made in Little Eock___ 39

Elementary Schools ________________________ 40

High Schools________________________________ 41

Eatings by Mr. Hamilton_____________________ 43

Conclusion-— It is, therefore, respectfully submitted

that the declaratory judgment and injunction should

be issued as prayed for___________________________ 47

A ppendix :

Table 1—Negro high school teachers getting less sal

ary than any white teacher in either high or ele

mentary school in Little Eock____________________ 49

Table 2—A comparison of plaintiff with white high

school teachers of English with equal and less ex

perience and professional qualifications__________ 49

Table 3—A comparison of English teachers in high

schools of Little Eock with Master’s degrees_____ 50

Table 4—A comparative table as to years of experi

ence of English teachers in high schools with A.B.

degree or less-___________________________________ 50

Table 5—A comparative table of Mathematics teach

ers in high schools with M.A. degrees____________ 51

I l l

PAGE

Table 6—A comparative table of Mathematics teach

ers in high schools with A.B. degrees or less--------- 51

Table 1-—A comparative table of Science teachers in

high schools with M.A. degrees___________________ 52

Table 8—A comparative table of Science teachers in

high schools with A.B. degrees or less----------------- 52

Table 9—A comparative table of History teachers in

high schools with A.B. degrees or less____________ 52

Table 10—A comparative table of Home Economics

teachers in high schools with A.B. degrees------------ 53

Table 11—A comparative table of Music and Band

teachers in high schools with A.B. degrees or less__ 53

Table 12—A comparative table of elementary teach

ers with A.B. or comparable degrees and 1-5 years

experience in Little Bock________________________ 54

Table 13—A comparative table of elementary teach

ers with A.B. or comparable degrees and 5-10

years experience in Little Rock__________________ 54

Table 14—A comparative table of elementary teach

ers with A.B. or comparable degrees and 10-20

years experience in Little Rock_________________ 55

Table 15—A comparative table of elementary teach

ers with A.B. or comparable degree and more than

20 years experience in Little Rock______ __________ 55

Table 16—A comparative table of elementary teach

ers without degrees and less than 10 years experi

ence in Little Rock______________________________ 56

Table 17—A comparative table of elementary teach

ers without degrees and from 10-20 years experi

ence in Little Rock______________________________ 57

Table 18—A comparative table of elementary teach

ers without degrees and more than 20 years experi

ence in Little Rock______________________________ 58

IV

T able of Cases.

PAGE

Alston V. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F. (2d)

992 (1940) certiorari denied, 311 U. S. 693________ 21,27

Chamberlain v. Kane, 264 S. W. 24 (1924)____________ 38

Hill v. Texas, 86 L. Ed. 1090_________________________ 28

McDaniel v. Board of Education, 39 F. Supp. 638

(1941) ___________________________________________ 27

Mills v. Board of Education, et al., 30 F. Supp. 245

(1939) --------------------------------------------------------- -------19,27

Mills v. Lowndes et al., 26 F. Supp. 792 (1939)________ 18

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 397, 26 L. Ed. 574____ _____ 28

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 IT. S. 354, 83 L. Ed. 757_______ 28

Smith v. Texas, 311 IT. S. 128, 85 L. Ed. 106, 108 (1940) 28

State v. Bolen, 142 Wash. 653, 254, P. 445____________ 38

Steel v. Johnson, 115 P. (2d) 145, 150_________________ 38

Thomas Hibbets et al. v. School Board et al., 46 F.

Supp. 368 ______ ______________ __________________ 25

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886)____________ 27

20 American Jurisprudence 886, P. 1027_____________ 37

IN THE

District Court of the United States

The Western Division of the Eastern District

of Arkansas

S usie M orris, and the C ity T eachers ’ \

A ssociation, of Little Rock, an unin- I

corporated Association,

Plaintiffs, I

v. I

R obert M. W illiam s , Chairman; M urray J

0. R eed, Secretary; Mrs. W. P. M cD er- \ c *vii Docket

mott ; M rs. W. F. R aw lings ; D r . R. M. j No' 555

B lak ely , and E. F. J en n in gs , consti- I

tuting the Board of Directors of the I

Little Rock Special School District,

and R ussell T. S cobee, Superinten

dent of Schools,

Defendants.

M E M O R A N D U M B R I E F F O R

P L A I N T I F F .

PART ONE.

Statement of the Case.

This is an action by Susie Morris, a Negro teacher in

the public schools of Little Rock, on behalf of herself and

the other Negro teachers and principals of Little Rock.

The case seeks a declaratory judgment and an injunction

against the Superintendent of Schools and the School Board

2

of Little Rock to restrain them from continuing the policy

of discrimination against Negro teachers and principals in

paying them less salary than white teachers and principals

of equal qualifications and experience because of race or

color.

The issues in the case are clear. A comparison of the

complaint and answer in the case follows:

Com plain t .

1. Jurisdiction in General.

2. Jurisdiction for declara

tory judgment.

3. Citizenship of parties.

4. a. Plaintiff is colored—

a Negro.

b. Plaintiff is a tax

payer.

c. Regular teacher in

the Dunbar High

S c h o o l , a p u b l i c

school in Little Rock

operated by defen

dants.

d. Class suit.

5. Plaintiff Teachers’ As

sociation.

6. a. Little Rock Special

School District ex

ists pursuant to laws

of Arkansas as an

administrative d e -

partment of state

performing essential

governmental func

tions.

A nsw er .

1. Denied.

2. Denied that there is any

discriminatory policy.

3. Admitted.

4. a. Admitted.

b. Admitted.

c. Admitted.

d. Admitted.

5. Out of case by reason of

ruling on motion to dis

miss as to teacher’s as

sociation.

6. a. Admitted.

3

b. Naming of Defen

dants.

7. a. State of Ark. has de

clared public educa

tion a state function.

b. General assembly of

Ark. has established

a system of free pub

lic schools in Arkan

sas.

c. Administration o f

public school system

is vested in a State

Board, Committee of

Education, School

Districts and local

Supts.

8. a. All teachers in Ark.

are required to hold

teaching licenses in

full force in accord

ance with the rules

of certification laid

down by the State

Board.

b. Duty of enforcing

this system is im

posed on s e v e r a l

school boards.

c. N e g r o and w h i t e

teachers and princi

pals alike must meet

same requirements

to receive teachers’

licenses from State

board and upon qual

ifying are issued

identical certificates.

b. Admitted except that

R. M. Blakely and E.

P. Jennings are now

chairman and secre

tary.

7. a. Entire paragraph

admitted.

b. Entire paragraph

admitted.

c. Admitted.

8. a. Admitted—but state

these requirements

a r e minimum re

quirements only.

b. Admitted.

c. Admitted.

4

9. a. P u b l i c schools of 9. a.

Little Bock are un

der direct control

and supervision of

defendants, acting as

a n administrative

dept, of State of

Arkansas.

b. Defendants are un- b.

der a duty to employ

teachers, fix salaries

and issue warrants

for payment of sal

aries.

10. a. Over a long period 10. a.

of years defendants

h a v e consistently

maintained and are

now maintaining pol

icy, custom and us

age of paying Negro

teachers and princi

pals less salary than

white teachers and

principals possess

ing the same profes

sional qualifications,

licenses and experi

ence, exercising same

duties and perform

ing the same services

as Negro teachers

and principals.

b. Such discrimination b.

is being practiced

against plaintiff and

a l l o t h e r Negro

teachers and princi

pals in L. R.—and is

based solely upon

their race or color.

Admitted ( e n t i r e

paragraph).

Admitted ( e n t i r e

paragraph).

Denied.

Denied.

5

11. a. Plaintiff a n d a l l

other Negro teachers

and principals are

teachers by profes

sion and are spe

cially trained f o r

their calling.

b. By r u l e s , regula

tions, practice, usage

and custom of state

acting through de

fendants as agents

plaintiff and all other

Negro teachers and

principals are being

denied equal protec

tion of laws, in that

solely by reason of

race and color they

are d e n i e d equal

compensation from

p u b l i c funds for

equal work.

12. a. Plaintiff has been

employed as a regu

lar teacher by defen

dants since 1935.

b. A.B. Degree from

Talladega College,

Talladega, Alabama.

c. Plaintiff holds a high

school teacher’s li

cense issued by State

Board of Education.

11. a. Admitted—but state

further that they dif

fer a m o n g them

selves and as com

pared to some white

teachers and princi

pals in degree of spe

cial training, ability,

character, profes

sional qualifications,

experience, duties,

services and accom

plishments.

b. Denied — and state

that if in individual

eases compensation

paid to teachers var

ies in amount it is

based solely on spe

cial training, ability,

character, profes

sional qualifications,

experience, duties,

services and accom

plishments.

12. a. Admitted.

b. Admitted.

c. Admitted.

6

d. In order to qualify

for this license plain

tiff h a s satisfied

same requirements

as those exacted of all

other teachers white

as well as Negroes.

e. Plaintiff exercises

the same duties and

performs services

substantially equiva

lent to those per

formed b y o t h e r

holders of teachers’

licenses with equal

and less experience

receive salaries much

larger than plaintiff.

13. a. Pursuant to policy,

custom and usage set

out above defendants

acting as agents of

State h a v e estab

lished a n d main

tained as s a l a r y

schedule which pro

vides a lower scale

for Negroes,

b. Practical application

has been and will be

to pay Negro teach

ers and principals of

equal qualifications

and experience less

compensation solely

on account of race or

color.

d. Admitted—but state

in doing so plaintiff

satisfied only mini

mum requirements.

e. Denied and state if

w h i t e teachers in

Little Rock receive

salaries larger than

plaintiff the differ

ence is based solely

on difference in spe

cial training ability,

character, profes

sional qualifications,

experience, duties,

services and accom

plishments, and in no

part are based on

race or qolor.

13. a. D e n y defendants

have ever had a sal

ary schedule.

b. Denied salaries are

fixed in whole or in

part on color.

7

14. a. In enforcing a n d

maintaining the pol

icy, regulation, cus

tom and usage by

which plaintiff and

other Negro teach

ers a n d principals

are uniformly paid

lower salaries than

white teachers solely

on account of race

and color, defendants

a r e violating th e

14th Amendment and

Sections 41 and 43 of

Title 8 of U. S. Code.

b. To the extent that

defendants act under

color of statute said

policy, custom and

usage is unconstitu

tional.

c. To the extent that

defendants act with

out benefit of statute

is nevertheless un

constitutional.

15. a. By virtue of discrim

inatory policy, and

schedule plaintiff is

denied an equal par

ticipation in the ben

efit derived from that

portion of her taxes

devoted t o public

school fund.

b. Solely on race or

color.

c. Contrary to 1 4 t h

Amendment.

14. a. Denied — deny that

there is any salary

schedule or discrim

inatory practice.

b. Denied.

c. Denied.

15. a. Denied.

b. Denied.

c. Denied.

8

d. Special and particu

lar damage.

e. Without remedy save

by injunction from

this Court.

16. a. Petition on behalf of

plaintiff and all other

Negro teachers filed

with defendants in

March, 1941, request

ing equalization,

b. Petition denied on or

about May 9, 1941.

17. a. Plaintiff and others

in class are suffering

irrreparable injury,

etc.

b. No plain adequate or

complete remedy to

redress wrongs other

than this suit.

c. Any other remedy

would not give com

plete remedy.

18. a. There is an actual

controversy.

d. Denied.

e. Denied.

16. a. Admitted.

b. Admitted—but state

reason for denial of

petition w a s that

there is no inequality

in salaries paid to

white a n d Negro

teachers.

17. a. Denied ( e n t i r e

paragraph).

b. Denied.

c. Denied.

18. a. Admitted.

9

PART TW O.

Statement of Facts.

The defendant School Board of Little Bock has general

supervision over the school system in Little Bock including

the distribution of the public school fund and the appoint

ment and fixing of salaries of the teachers in the public

schools of Little Bock. The public school fund comes from

state taxes. Separate schools are maintained for white and

colored pupils. All the teachers in the Avhite schools are of

the white race and all of the teachers in the colored schools

are of the Negro race (14).

In the school district of which Little Bock is a part the

per-capita expenditure per white child was $53 and per

colored child was $37 for 1939-40. During the same period

the revenue available was $47 per child. In Arkansas dur

ing that period the average salary for elementary teachers

was: white $526 and Negro $331; and for high school teach

ers was $856 for white and $567 for Negroes (8-9).

All of the public schools in Little Bock, both white and

Negro, are part of one system of schools and the same type

of education is given in all schools, are open the same num

ber of hours per day and the same number of days (296).

The Negro teachers do the same work as the white teachers

(312).

Method of Fixing Salaries.

The salaries of teachers are recommended by the super

intendent to the Personnel Committee of the board after

which a report is made by the Personnel Committee to the

board for adoption (15). Neither the board nor the Per

sonnel Committee interviews the teachers (34, 35, 156). In

the fixing of salaries from year to year the board does not

10

check behind the recommendations of the superintendent

(75). The recommendations of the superintendent to the

Personnel Committee always designate the teachers by race

(178, 180, 313). Likewise, the report from the Personnel

Committee to the hoard always designates the individual

teachers by race (182, 184, 313, 314). The race of the indi

vidual teachers is in the minds of the members of the Per

sonnel Committee in their consideration of the fixing of

salaries (184, 185). The salaries for 1941-42 were not fixed

on the basis of teaching ability or merit (312-313).

New Teachers.

Although all of the defendants denied that there was

a salary ‘ ‘ schedule ’ ’ as such, the plaintiff produced a salary

schedule for Negro teachers providing a minimum salary

of $615 (Plaintiff’s Exhibit 4). Superintendent Scobee de

nied ever having seen such a schedule but admitted that

since 1938 “ practically all” new Negro teachers had been

hired at $615. All new white teachers during that period

have been hired at not less than $810 (530). For years it

has been the policy of the Personnel Committee to recom

mend lower salaries for Negro teachers than for white teach

ers new to the system (41). This has been true for many

years (41). Other defendants admitted that all new Negro

teachers were paid either $615 or $630 and all new white

teachers were paid a minimum of $810 (123, 129, 150, 308).

In 1937 the School Board adopted a resolution whereby

a “ schedule” of salaries was established providing that new

elementary teachers were to be paid a minimum of $810,

junior high $910 and senior high $945 (476-477). Although

Superintendent Scobee denied that the word “ schedule”

actually meant schedule he admitted that since that time all

white teachers had been employed at salaries of not less

than $810 (477-478).

11

The difference in salaries paid new white and Negro

teachers is supposed' to be based upon certain intangible

facts which the superintendent gathers by telephone conver

sations and letters in addition to the information in the

application blanks filed by the applicants (531). For ex

ample, two teachers were being considered for positions, one

white and one Negro. The superintendent, following his

custom, telephoned the professor of the white applicant and

received a very high recommendation for her. He did not

either telephone or write the professors of the Negro appli

cant. As a result he paid the white teacher $810 as an elemen

tary school teacher, and the Negro teacher $630 as a high

school teacher despite the fact that their professional quali

fications were equal (530-533). Superintendent Scobee also

admitted that where teachers have similar qualifications, if

he would solicit recommendations for one and receive good

recommendations and fail to do so for the other, the appli

cant whose recommendations he solicited and obtained

would appear to him to be the better teacher (532). He

seldom sought additional information about the Negro appli

cants (588), although personal interviews were used in the

fixing of salaries (545) and played a large part in determin

ing what salary was to be paid (545).

Superintendent Scobee testified that the employment and

fixing of salaries of new teachers amounted to a “ gamble”

(543). He admitted that he had made several mistakes as

to white teachers and that although he was paying one white

teacher $900 she was so inefficient he was forced to discharge

her (847). During the time he has been superintendent Mr.

Scobee, has never been willing to gamble more than $630 on

any Negro teacher and during the same period has never

gambled less than $810 on a new white teacher (546). Some

new white teachers are paid more than Negro teachers with

superior qualifications and longer experience (559, 570).

12

One of the reasons given for the differential in salaries

is that Negro teachers as a whole are less qualified (45) and

that the majority of the white teachers ‘ ‘ have better back

ground and more cultural background” (85). Another de

fendant testified: “ I think I can explain that this way: the

best explanation of that, however, is the Superintendent of

the Schools is experienced in dealing and working with

teachers, white teachers and colored. He finds that we have

a certain amount of money, and the budget is so much, and

in his dealing with teachers he finds he has to pay a certain

minimum to some white teachers qualified to teach, a teacher

that would suit in the school, and he also finds that he has

to pay around a certain minimum amount in order to get

that teacher, the best he can do about it is around $800 to

$810 to $830, whatever it may be he has to pay that in order

to pay that white teacher that minimum amount, qualified

to do that work. Now, in his experiences with colored

teachers, he finds he has to pay a certain minimum amount

to get a colored teacher qualified to do the work. He finds

that about $630, whatever it may be” (185-186).

Since it is the general understanding that the board can

get Negro teachers for less it has been the policy of the

board to offer them less than white teachers of almost identi

cal background, qualifications and experience (186). Further

explanations of why Negroes are paid less is that: “ They

are willing to accept it, and we are limited by our financial

structure, the taxation is limited, and we have to do the best

we can” (187); and, that Negroes can live on less money than

white teachers (188). The president of the board testified

that they paid Negroes less because they could get them for

less (19).

One member of the school board testified in response to

a question: “ If you had the money, would you pay the

13

Negro teachers the same salary as yon pay the white teach

ers?” testified that: “ I don’t know, we have never had the

money” (80).

Old Teachers.

Comparative tables showing the salaries of white and

Negro teachers according to qualifications, experience and

school taught have been prepared from the exhibits filed in

the case and are attached hereto as appendices. According

to these tables no Negro teacher is being paid a salary equal

to a white teacher with equal qualifications and experience.

This fact is admitted by Superintendent Scobee (862).

It is the policy of the defendants to pay high school

teachers more salary than elementary teachers (297). It is

also the policy of the defendants to pay teachers with ex

perience more than new teachers (610). It is admitted that

the Negro teachers at Dunbar High School are good teachers

(312) . However, the plaintiff and twenty-four other Negro

high school teachers with years of experience are now being

paid less than any white teacher in the system including

elementary teachers as well as teachers new to the system

(304). Superintendent Scobee was unable to explain the

reason for this or to deny that the reason might have been

race or color of the teachers (304). He testified that he

could not fix the salaries of the Negro high school teachers

on any basis of merit because “ my funds are limited”

(313) .

Since Superintendent Scobee has been in office (1941)

he has carried the salaries along on the same basis as he

found them (297). He also testified that if the question of

race had been the basis for the fixing of salaries prior to

1941 then this would be true today (298). Although there

have been a few “ adjustments” there have been no changes

14

in salary since 1941. The salaries for 1941-42 were not

fixed on any basis of merit (312).

In past years Negro teachers have been employed at

smaller salaries than white teachers and under a system of

blanket increases over a period of years Negroes have re

ceived smaller increases (129). The differential over a

period of years has increased rather than decreased (130).

One member of the board testified that “ I think there are

some Negro teachers are as good as some of the white

teachers, but I think there are some not as good” (130-131).

Another board member testified that he thought there were

some Negro teachers getting the same salary as white

teachers with equal qualifications and experience (158).

Policy of Board in Past.

Several portions of the minutes of the school board

starting with 1926 were placed in evidence. In 1926 several

new teachers were appointed. The white teachers were ap

pointed at salaries of from $90 to $150 a month. Negro

teachers were appointed at from $63 to $80 a month (888,

889). Later the same year the superintendent of schools

recommended that “ B. A. teachers without experience get

$100.00, $110.00, $115.00, according to the assignment to

Elementary, Junior High, or Senior High respectively” .

Additional white teachers were appointed at salaries of

from $100 to $200 a month and at the same time Negroes

were appointed at salaries of from $65 to $90 (892, 893) in

1927 all white teachers with the exception of six were given

a flat increase of $75 per year and all Negro teachers were

given a flat increase of $50 per month (896, 897).

On May 14, 1928 the school board adopted a resolution:

“ all salaries for teachers remain as of 1927-1928, and in

event of the 18 mill tax carrying May 19, 1928, the white

15

school teachers are to receive an increase of $100 for 1928-

29 and the colored teachers an increase of $50 for 1928-

1929” (899). During the same year three white principals

were given increases of from $25 a month to $100 a year

while one Negro principal was given an increase of $5 a

month (900).

On May 21, 1929 the board adopted a resolution that:

“ an advance of $100.00 per year be granted all white

teachers, and $50.00 per year for all colored teachers, sub

ject to the conditions of the Teachers’ salary” (907). Prior

to that time Negro teachers were getting less than white

teachers (78). According to this resolution all white teachers

regardless of their qualifications received increases of $100

each while all Negro teachers were limited to increases of

$50 each (79). It was impossible for a Negro teacher to

get more than a $50 increase regardless of qualifications

(79). One reason given for paying all white teachers a $100

increase and all Negro teachers $50 was that at the time

the Negro teachers were only getting about half as much

salary as the white teachers (80).

On April 30, 1932, all teachers’ salaries were cut 10%

(937). On June 19, 1934, a schedule of salaries for school

clerks was established providing $50 to $60 a month for

white clerks and $40 to $50 a month for colored clerks

(967). It was also decided that: “ white teachers entering

Little Rock Schools for 1933-34 for the first time at a mini

mum salary of $688.00, having no cut to be restored, be

given an increase of $30 for the year 1934-35 (967). On

June 28, 1935, at the time the plaintiff was employed white

elementary teachers new to the system were appointed at

$688 to $765 for elementary teachers and $768 for high

school teachers while plaintiff and other Negro teachers

were employed at $540 (973, 974).

16

On March 30, 1936 the school board adopted the follow

ing recommendations: “ that the contracts for 1936-37 of

all white teachers who are now making $832 or less be in

creased $67.50, and all teachers above $832.50 be increased

to $900, and that no adjustment exceed $900.” ; and “ that

the contracts for 1936-37 of all colored teachers who now

receive $655 or less be increased $45, and all above $655 be

increased to $700, and that no adjustment exceed $700” .

It was also provided “ that the salaries of all white teachers

who have entered the employ of the Little Eock School

Board since above salary cuts, or whose salaries were so

low as not to receive any cut, be adjusted $45.00 for 1935-

36” ; and “ that the salaries of all colored teachers who have

entered the employ of the Little Eock School Board since

the above salary cuts, or whose salaries were so low as not

to receive any cut, be adjusted $30.00 for 1935-36” (978-

979).

On April 25, 1936 it was decided by the school board:

“ The contracts are to be the same as for 1935-36, except

that those white teachers receiving less than $900.00, and

all colored teachers receiving less than $700, who are to get

$67.50 and $45 additional respectively, or fraction thereof,

not to exceed $900 and $700, respectively” .

Bonus Payments.

In 1941 the school board made a distribution of certain

public funds as a supplemental payment to all teachers

which was termed by them a “ bonus” . This money was dis

tributed pursuant to a plan adopted by the school board

(136—see Exhibits A and 3-B). The plan was worked out

17

and recommended by a committee of teachers in the public

schools (131). This committee was composed solely of white

teachers (316) because, as one member of the board testi

fied: “ We don’t mix committees in this city” (131) Super

intendent Scobee testified that he did not even consider the

question of putting some Negro teachers on the committee

(322).

Under this plan there are three criteria used in deter

mining how many “ units” a teacher is entitled to: one,

years of experience, two, training, and three salary (see

Exhibits 3-A and 3-B). After the number of units are de

termined the fund was distributed as follows: each white

teacher is paid $3.00 per unit and each Negro teacher is

paid $1.50 per unit. After the number of units were deter

mined the sole determining factor as to whether the teachers

received $3.00 or $1.50 per unit was the race of the teacher

in question (527).

After the 1941 distribution the Negro teachers went to

Superintendent Scobee and protested against the inequality,

yet, another supplemental payment was made in 1942 and

the same plan was used (321).

In 1937 the Negro teachers filed a petition with the de

fendants seeking to have the inequalities in salaries because

of race removed. No action was taken other than to refer

it to the superintendent (985). In 1938: “ Petition signed

by the Colored Teachers of the Little Eock Public Schools,

requesting salary adjustments, was referred to Committee

on Teachers and Schools” (995). On May 27, 1939 a report

was adopted by the school board which included the follow

ing: “ Petition of colored teachers for increase in pay. Dis

allowed” (1003).

18

PART THREE.

ARGUMENT.

I.

Payment of less salary to Negro public school

teachers because of race is in violation of Fourteenth

Amendment.

There are several decisions of United States Court which

have established the rule that the fixing of salaries of Negro

teachers in public schools at a lower rate than that paid to

white teachers of equal qualifications and experience, and

performing essentially the same duties on the basis of race

or color is violative of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The first case is Mills v. Lowndes et al., 26 F. Supp. 792

(1939). This was an action for an injunction brought by a

Negro principal in the public schools of Anne Arundel

County, Maryland, against the state treasurer, comptroller

and other state officials seeking to enjoin the distribution of

the state “ Equalization fund’ ’. It was alleged that the fund

was distributed on the basis of a statutory salary schedule

which provided a lower minimum salary for Negro teachers

than for white teachers. Judge W. Calvin C itesxut dis

missed the petition on the ground that the several counties

and cities of Maryland were the units of education and what

ever action there might be would have to be against these

local units.

Judge Ch esn u t , however, ruled that:

“ The allegations of the complaint that the Mary

land minimum salary statutes for teachers in public

schools are practically administered in many of the

Counties in such a way that there is discrimination

19

against colored teachers solely on account of race and

color charges an unlawful denial of the equal protec

tion of the laws to colored school teachers in Counties,

if any, where such conditions prevail, . . . ” (26 F.

Supp. 792, 805).

In the same decision the point was established that pub

lic school teachers had the right to maintain this type of

action:

“ I conclude therefore that the plaintiff does have

a status, not as a public employee, but as a teacher by

occupation which entitled him to raise the Consti

tutional question; and if the complaint were made

against the County Board of Education, which, it is

alleged, is making the unjust discrimination between

equally qualified white and colored teachers solely on

account of their race and color, it would state a case

requiring an answer. ’ ’

The next case was against the Board of Education of

Anne Arundel County and the County Superintendent of

Schools. Mills v. Board of Education et al, 30 F. Supp. 245

(1939). This case was an action for a declaratory judgment

and injunction. It resulted in a full trial on the merits after

an answer was filed denying all of the essential allegations.

At the trial it developed that Anne Arundel County had its

own minimum salary schedule which was higher than the

statutory schedule. The defendants maintained that the dif

ferences in salary were not based on race but on differences

in qualifications and services rendered. Judge Chesnttt, in

deciding this case by granting the injunction, held that:

“ The controlling question in this case, however,

is not whether the statutes are unconstitutional on

their face, but whether in their practical application

they constitute an unconstitutional discrimination on

account of race and color, prejudicial to the plaintiff.

20

We must therefore look to the testimony in this case

to see how the statutes have been applied in Anne

Arundel County. . . . The county scale fixes the

minimum salary of a white principal of a comparable

school at $1,550, and for a colored principal $995; but

in practice the County Board in many cases actually

pays higher salaries to the principals of schools, in

consideration of particular conditions and capacities

of the respective principals. Thus the plaintiff’s

salary for the current year has been fixed at $1058

or $103 more than the minimum, and in the case of

three white principals, mentioned in the evidence, the

salary is $1880 per year, or $250 more than the mini

mum. The defendants contend that the materially

higher salaries of these white principals of schools

comparable in size to that of which the plaintiff is

principal is due to the judgment of the Board that

the three white principals have superior professional

attainments and efficiency to that of Mills; but it is

to be importantly noted that these personal qualities,

while explaining greater compensation to the particu

lar individuals, than the minimum county scale for

the particular position, do not account for the differ

ence between $1058 only received by Mills and the

minimum of $1550 which by the County scale would

have to be paid to any white principal of a compar

able school. Or, in other words, if Mills were a white

principal he would necessarily receive according to

the county scale not less than $1550 as compared with

his actual salary of $1058.” (30 F. Supp. 245, 248.)

“ I also find from the evidence that in Ann Arun

del County there are 243 white teachers and 91 col

ored teachers but no one colored teacher receives so

much salary as any white teacher of similar qualifica

tions and experience.

“ The crucial question in the case is whether the

very substantial differential between the salaries of

white and colored teachers in Anne Arundel County

21

is due to discrimination on account of race or color.

I find as a fact from the testimony that it is. . . . ”

(30 F. Supp. 245, 249.)

The third case was Alston v. School Board of City of

Norfolk, 112 F. (2d) 992 (1940); certiorari denied, 311 U. S.

693. In this case the Circuit Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit reversed the decision of the lower Court

which had dismissed the complaint of a Negro teacher of

Norfolk. The complaint was similar to the one in the Mills

case {supra) and the instant case. The Alston case involved

a salary schedule providing minimum and maximum sal

aries.

In the opinion for the Circuit Court of Appeals, Judge

P arker, after quoting pertinent paragraphs of the com

plaint, stated:

“ That an unconstitutional discrimination is set

forth in these paragraphs hardly admits argument.

The allegation is that the state, in paying for public

services of the same kind and character to men and

women equally qualified according to standards which

the state itself prescribes, arbitrarily pays less to

Negroes than to white persons. This is as clear a

discrimination on the ground of race as could well be

imagined and falls squarely within the inhibition of

both the due process and the equal protection clauses

of the 14th Amendment. . . . ” (112 F. (2d) 992,

995-996.)

There are no. cases to the contrary. It is, therefore,

clear that the question of race or color cannot be used in the

fixing of salaries of public school teachers. Whenever race

or color is considered in the fixing of teachers’ salaries there

is a violation of the 14th Amendment to the U. S. Consti

tution.

22

II.

The policy, custom and usage of fixing salaries of

public school teachers in Little Rock violates the Four

teenth Amendment.

The evidence in this case consists of the records of the

school board including minutes and records of salary pay

ments along with efforts of members of the school board to

explain and contradict their own records. An examination

of the list of salaries now being paid demonstrates clearly

that Negro teachers are being paid less salary than white

teachers of equal qualifications and experience.

After a full trial on the merits in the second Mills case

{supra) Judge Ch e sn u t decided the case in favor of the

plaintiff because:

“ I also find from the evidence that in Anne Arundel

County there are 91 colored teachers but no one col

ored teacher receives so much salary as any white

teacher of similar qualification and experience.”

(30 F. Supp. 245, 249.)

Comparative tables showing the salaries of white and

Negro teachers according to qualifications, experience and

school taught have been prepared from the exhibits filed in

the instant case and are attached hereto as appendices.

According to these tables “ no one colored teacher receives

so much salary as any white teacher of similar qualifications

and experience.” These facts were admitted by Superin

tendent Scobee (862). This brings the instant case clearly

within the rule as established in the Mills case, which rule

was later approved by the Circuit Court of Appeals in the

Alston case (supra).

The present differential in salaries of white and Negro

teachers is the result of a combination of discriminatory

23

practices of the defendants forming a policy, custom and

usage extending over a long period of years. These prac

tices have been:

A. A general over-all policy of paying Negro teachers

less salary than white teachers.

B. A policy of fixing lower salaries for Negro

teachers than for new white teachers without ex

perience.

C. A system of flat salary increases providing larger

increases for all white teachers than for any Negro

teacher.

D. A system of distributing supplementary payments

on an unequal basis because of race.

A. General policy of defendants.

The facts in the instant case are peculiarly in the hands

of the defendants. It was, therefore, necessary to develop a

large part of the plaintiff’s case by testimony from the

defendants called as adverse witnesses.

The defendants have repeatedly classified teachers by

race in fixing salaries. The defendants admitted that for

many years it has been the policy of the Personnel Com

mittee to recommend lower salaries for Negro teachers than

for white teachers new to the system (41). This has been

true for many years (41). Thus, Negro teachers are

grouped together on the basis of race or color.

Cultural Background.

The defendants attempt to explain this differential in

salaries in several ways. For example, one defendant testi

fied that Negro teachers as a whole are less qualified (45);

and that the majority of the white teachers “ have better

background and more cultural background” (85).

24

Economic Theory.

Another defendant testified: “ I think I can explain that

this way; the best explanation of that, however, is the

Superintendent of the Schools is experienced in dealing and

working with teachers, white and colored. He finds that we

have a certain amount of money, and the budget is so much,

and in his dealing with teachers he finds he has to pay a

certain minimum to some white teachers qualified to teach,

a teacher that would suit the school, and he also finds that

he has to pay around a certain minimum amount in order to

get that teacher, the best he can do about it is around $800 to

$810, to $830, whatever it may be he has to pay that in order

to pay that white teacher that minimum amount, qualified

to do that work. Now, in his experience with colored

teachers, he finds he has to pay a certain minimum amount

to get a colored teacher qualified to do the work. He finds

that about $630, whatever it may be” (185-186).

Further explanation is that since there is a general

understanding that the board can get Negro teachers for

less it has been the policy of the board to offer them less

than white teachers of almost identical background, quali

fications and experience (186). It was also revealed that

Negroes are paid less because: “ They are willing to accept

it, and we are limited by our financial structure, the taxation

is limited, and we have to do the best we can” (188). The

president of the board testified that they paid Negroes less

because they could get them for less (19). Still another

member of the board testified in response to a question: “ If

you had the money, would you pay the Negro teachers the

same salary as you pay the white teachers?” replied that:

“ I don’t know, we have never had the money” (80). Super

intendent Scobee testified that he could not fix the salaries

of Negro high school teachers on any basis of merit because

“ my funds are limited” (313).

25

In the ease of Thomas Hibbets et al. v. School Board

et al., 46 F. Supp. 368, which was decided by IT. S. District

Judge E lm er D. D avies, Judge of the District Court for the

Middle District of Tennessee, the defendants offered as a

defense on part of the Board of Education that the salary

differential was an economic one and not based upon race or

color; and also, that salaries were determined by the school

in which the teacher was employed. In deciding these points

Judge D avies wrote:

“ The Court is unable to reconcile these theories with

the true facts in the case and therefore finds that the

studied and consistent policy of the Board of Educa

tion of the City of Nashville is to pay its colored

teachers salaries which are considerably less than the

salaries paid to white teachers, although the eligi

bility and qualifications and experience as required

by the Board of Education is the same for both white

and colored teachers; and that the sole reason for

this difference is because of the race of the colored

teachers.” 46 F. (Supp.) 368.

B. Minimum salaries for new teachers.

All of the defendants denied that there ever has been a

salary “ schedule” for the fixing of teachers’ salaries. The

plaintiff, however, produced a salary schedule for Negro

teachers providing a minimum salary of $615 (Plaintiff’s

Exhibit 4). Superintendent Scobee denied ever having seen

such a schedule but admitted that since 1939 “ practically

all” new Negro teachers had been hired at $615 while all

new white teachers hired during the same period were paid

not less than $810 (530).

In 1937 the School Board adopted a resolution whereby a

“ schedule” of salaries was established providing that new

elementary teachers were to be paid a minimum of $810

(476-477). Although Superintendent Scobee attempted to

26

explain that the word “ schedule” did not mean schedule,

he admitted that since that time all white teachers had been

hired at salaries of not less than $810 (477-478).

The other defendants admitted that all new Negro

teachers were paid either $615 or $630 and all new white

teachers were paid a minimum of $810 (123, 129, 150, 308).

In the second Mills case Judge Ch e sx u t held that a

minimum salary schedule adopted by local school board

providing a higher minimum salary for white teachers than

for Negro teachers was unconstitutional. In the Alston

case there was a local school board schedule with a m inim um

of $597.50 for Negro teachers new to the system and a mini

mum of $850 for white teachers new to the system. The

Circuit Court of Appeals after quoting paragraphs from

the complaint which set out the minimum and maximum

salary schedule decided:

“ That an unconstitutional discrimination is set

forth in these paragraphs hardly admits argument.

The allegation is that the state, in paying for public

services of the same kind and character to men and

women equally qualified according to standards

which the state itself prescribes, arbitrarily pays

less to Negroes than to white persons. This is as

clear a discrimination on the ground of race as could

well be imagined and falls squarely within the inhibi

tion of both the due process and the equal protective

clauses of the 14th Amendment.” (112 F. (ad) 992,

995-996.)

In the instant case the defendants sought to escape the

rule as established in the Mills and Alston cases {supra) by

denying that they have a salary schedule in writing. They

testified that all teachers, white and Negro, were hired on

an individual basis without regard to race or color. All of

the defendants denied that there was any written schedule

establishing lower salaries for Negro teachers because of

27

race or color. They, however, admitted that in actual prac

tice all Negroes were hired at either $615 or $630 while all

white teachers were hired at not less than $810. The validity

of their method of fixing salaries is determined by the

actual practice rather than the theory.

“ . . . though the law itself be fair on its face and

impartial in appearance yet, if it is applied and ad

ministered by public authority with an evil eye and

an uneven hand, so as practically to make unjust and

illegal discrimination between persons in similar cir

cumstances, material to their rights, the denial of

equal justice is still within the prohibition of the

Constitution. ’ ’

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886).

This is the same theory which has been applied in all

cases involving discrimination against Negro public school

teachers which have come before the Federal Courts.

See:

Alston v. School Board (supra);

Mills v. Board of Education (supra);

McDaniel v. Board of Education, 39 F. Supp. 638

(1941).

In the Mills case (supra) Judge Chesnut stated:

“ . . . In considering the question of constitution

ality we must look beyond the face of the statutes

themselves to the practical application thereof as

alleged in the complaint . . . ”

In one of the latest cases involving the exclusion of

Negroes from jury service it appeared that in Harris

County, Texas, only 5 of 384 grand jurors summoned during

a seven year period were Negroes and only 18 of 512 petit

jurors were Negroes. In reversing the conviction of a

28

Negro under such a system, Mr. Associate Justice B lack

stated:

“ Here, the Texas statutory scheme is not itself

unfair; it is capable of being carried out with no

racial discrimination whatsoever. But by reason of

the wide discretion permissible in the various steps

of the plan, it is equally capable of being applied in

such a manner as practically to proscribe any group

thought by the law’s administrators to be undesirable

and from the record before us the conclusion is in

escapable that it is the latter application that has

prevailed in Harris County. Chance and accident

alone could hardly have brought about the listing for

grand jury service of so few Negroes from among

the thousands shown by the undisputed evidence to

possess the legal qualifications for jury service

7 7

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 85L; Ed. 106, 108

(1940).

See also:

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 397, 26 L. Ed. 574;

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 IJ. S. 354, 83 L. Ed. 757;

Hill v. Texas, 86 L. Ed. 1090.

Superintendent Scobee testified that the difference in

salaries paid new white and Negro teachers has been based

upon certain intangible facts, most of which he had for

gotten by the time of the trial. Much of the information

used in fixing salaries was from letters and telephone con

versations in addition to the application blanks filed by the

applicants (531). In actual practice this procedure itself

discriminates against Negro applicants.

The testimony of Superintendent Scobee reveals the

extent of this discrimination. Two teachers, one white and

one colored, were being considered for teaching positions.

29

The superintendent, following his custom, telephoned the

college professor of the white applicant and received a very

high recommendation for her. He did not either telephone

or write the professors of the Negro applicant. As a result

he offered the white applicant $810 as an elementary teacher

and the Negro $630 as a high school teacher despite the

fact that their professional qualifications were equal (530-

533).

The extent of the discrimination against Negro teachers

brought about by this unequal treatment is emphasized by

further testimony of Superintendent Scobee that:

a. Where teachers have similar qualifications, if he

would solicit recommendations for one and receive

good recommendations and fail to do so for the other,

the applicant whose recommendations he solicited

and obtained would appear to him to be the better

teacher (532).

b. He seldom sought additional information about the

Negro applicants (552).

c. Personal interviews were used in the fixing of salaries

(545); and played a large part in determining the

amount of salary (545).

d. He did not even interview all of the Negro applicants

(588).

In another recent case involving the question of exclu

sion of Negroes from jury service facts were presented

which are closely similar to the facts presented by the de

fendants in this case. In the jury case, Mr. Chief Justice

S tone for the H. S. Supreme Court stated:

“ We think petitioners made out a prima facie

case, which the state failed to meet, of racial dis

crimination in the selection of grand jurors which

the equal protection clause forbids. As we pointed

30

out in Smith v. Texas, supra (311 U. S. 131, 85 L.

Ed. 86, 61 Set. 164), chance or accident could hardly

have accounted for the continuous omission of

Negroes from the grand jury lists for so long a

period as sixteen years or more. The jury commis

sioners, although matter was discussed by them, con

sciously omitted to place the name of any Negro on

the jury list. They made no effort to ascertain

whether there were within the County members of

the colored race qualified to serve as jurors, and if

so who they were. They thus failed to perform their

constitutional duty-recognized by section 4 of the

Civil Eights Act of March 1, 1875, 8 U. 8. C. A. sec

tion 44, and fully established since the decision in

1881 of Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370, 26 L. Ed.

567, supra not to pursue a course of conduct in the

administration of their office which would operate to

discriminate in the selection of jurors on racial

grounds. Discrimination can arise from the action

of commissioners who exclude all Negroes whom they

do not know to he qualified nor seek to learn whether

there are in fact any qualified Negroes available for

jury service.” (Italics ours.) Hill v. Texas {supra).

In the instant case the practice of Superintendent Scobee

outlined above is just as discriminatory as the policy and

custom of the commissioners in the Hill case and in itself

violates the 14th Amendment.

C. Salaries of older teachers and

flat increases.

According to the tables of teachers’ salaries for 1941-

42 attached hereto as appendices no Negro teacher is being

paid a salary equal to a white teacher with equal qualifica

tions and experience. This fact is admitted by Superin

tendent Scobee (862). These salaries for 1941-42 were not

fixed on any basis of merit of the individual teachers (312).

31

All of the public schools in Little Rock, both white and

Negro, are part of one system of schools and the same type

of education is given in all schools, white and Negro (295).

The same courses of study are used. All schools are open

the same number of hours per day and the same number of

days (296). The same type of teaching is given in all schools.

Negro teachers do the same work as the white teachers

(312).

The defendants testified that there is a policy to pay

high school teachers more than elementary teachers (297);

and to pay teachers with experience more than new teachers

(312). It is also admitted that the Negro teachers at Dun

bar High School are good teachers (312). However, the

plaintiff and twenty-four other Negro high school teachers

of Dunbar with years of experience are now being paid less

than any white teacher in the system (304). Superintendent

Scobee was unable to explain this or to deny that the reason

might have been race or color of the teachers (304).

The present differential in salaries between white and

Negro teachers is the result of a long standing policy of

employing Negro teachers at smaller salaries than white

teachers and a system of blanket increases over a period of

years whereby all Negro teachers have received smaller

increases than white teachers (129). It is admitted that

the differential has increased rather than decreased over a

period of years (130).

Several portions of the minutes of the School Board

starting with 1926 were placed in evidence. These minutes

were digested and set out in the Statement of Facts under

the heading “ Policy of the Board in Past” . It is, therefore,

not necessary to repeat these portions of the minutes in

this section of the brief. We respectfully urge a re-reading

of the above section of this Statement of Facts.

32

It is clear from these portions of the minutes and the

testimony of members of the School Board that it is and

has been the policy of the School Board of Little Rock, not

only to employ Negro teachers at a smaller salary than

white teachers, but in addition there has been the policy of

giving blanket increases which are larger for white teachers

than for Negro teachers.

Blanket Increases on Basis of Race.

The defendants repeatedly admitted that all Negro

teachers new to the system are employed at salaries less

than white teachers new to the system. Defending the policy

of giving larger increases to all white teachers than to any

Negro teacher, the defendants testified that the differential

in the increases was based upon the salaries being paid the

two groups of teachers while at the same time admitting

that the differential in salaries was based upon race or color

of the teachers (37-39).

For example: One defendant testified as follows:

“ Q. So is it not true that the worst white teacher

at that time got more than the best Negro teacher?

A. No.

Q. Well, was there any other basis? A. Yes, the

basis of their flat pay.

Q. I mean in order to qualify for this, there are

two amounts involved, $75 and $50, and in order to

qualify for the $75, is it not true that the only thing

you had to do was to be white? A. No.

Q. Well, the white teachers got $75? A. Yes, sir,

just in a different bracket of pay.

Q. Different bracket? A. Different set-up. It

was on a basis of salary they were then drawing.

Q. Well, weren’t they all getting more than the

Negro teachers? A. Yes.

Q. So that prior to that time there was a differ

ence between them, between the white and colored

33

teachers, in the salaries they were receiving and after

that time the difference was even wider. A. I have

not figured out whether it was wider or not, there

was a difference.” (37-38.)

The inevitable result of this type of discrimination is

likewise admitted by the defendants.

“ Q. So the Negro teachers that came in at less

salary are still trailing below the white teachers. Is

that true? A. It probably is.

Q. So, regardless of how many degress they might

go away and get, they would still be trailing behind

the white teachers they came in with. Would that be

true? A. Not in every case, I don’t think.

Q. Can you give any exceptions? A. No.” (48).

D. The discriminatory policy of distributing

supplementary salary payments on an

unequal basis because of race.

Further wilful disregard for the equal protection clause

of the United States Constitution, is apparent in the policy

of distributing supplementary payments to teachers in the

Little Eock School System. It is admitted that the funds

for the supplementary salary payments was received from

state tax funds (522). These supplementary payments

were distributed under the same policy as has been used

in the fixing of the basic salaries of these teachers. Some

of the testimony on that point was :

“ Q. And in distributing the public money didn’t

you feel obligated under the same rules as the other

money you disturbed for the School Board? A. So

far as it was public money, yes.

Q. Why? You didn’t think you could distribute

it any way you pleased, did you? A. No, but the At

torney General of Arkansas ruled it was within the

discretion of the Local Board to distribute it.

34

Q. Did you think you could distribute it on the

basis of—so much to the teacher of one school and

so much to the teacher of another school, on that

basis? A. Well, according to the rule, if I remember

right, said so, I believe we could.

Q. As to the rate, we are not concerned about that.

Do you think you could distribute more to white per

sons than to Negro persons? A. I think, legally

speaking, under the terms of his opinion it would

have been possible.

Q. Then you think the Fourteenth Amendment

did not touch you? A. I did not go into the Four

teenth Amendment.” (522-523.)

This type of total disregard for the Fourteenth Amend

ment is characteristic of the entire policy of the School

Board of the City of Little Bock and the Superintendent of

Schools in administering public funds allotted for the pay

ment of teachers ’ salaries.

The facts concerning the distribution of the supple

mental salary payments, 1941-1942, are not in dispute at all.

The money obtained from public funds was distributed pur

suant to a plan recommended by Superintendent Scobee and

adopted by the School Board (136). (See Exhibits 3-A and

3-B.) The plan was worked out and recommended by a

committee of teachers in the public schools of Little Bock

(131). This committee was composed solely of white

teachers (316), because, as one member of the Board testi

fied: “ We do not mix committees in this City” (131).

Superintendent Scobee, who appointed the committee, tes

tified that he did not even consider the question of putting

some Negro teachers on the committee (322). Under this

plan only three criteria were used in determining how many

“ units” a teacher is entitled to. One, years of experience;

two, training three, salary (see Exhibits 3-A and 3-B). After

35

the number of units were determined, the fund was dis

tributed as follows:

Each white teacher was paid $3 per unit and each Negro

teacher was paid $1.50 per unit. After the number of units

.were determined, the sole determining factor as to whether

the teacher received $3.00 or $1.50 per unit was the race of

the teacher in question (527).

Further evidence of the complete disregard for Negro

teachers in Little Rock and for the Constitution of the

United States, again appear from the fact that although

representatives of the Negro teachers protested to Superin

tendent Scobee against the inequality in the 1941 payment,

yet, another supplemental payment was made in 1942, after

this case was filed and the same plan was used (321). No

effort at all has been made by the defendants to defend this

violation of the United States Constitution other than the

explanation that the opinion of the Attorney General of

Arkansas permitted the discrimination.

III.

The rating sheets offered in evidence by defendants

should not have been admitted in evidence.

Prior to the Spring of 1942 formal rating sheets were

never used by the defendants (50, 52). Some supervisors

used their own rating sheets in order to carry out their work

of supervision. In the Fall of 1941, after the Negro teachers

of Little Rock had petitioned defendants for the equalization

of teachers’ salaries the supervisors along with the super

intendent of schools prepared formal rating sheets of three

columns for the purpose of rating the teachers (623). In

the Spring of 1942 after this ease was filed, the teachers

were rated on the formal rating sheets. These rating sheets

36

according to Mr. Scobee were “ not for the purpose of fixing

salaries” (470). The real purpose of the rating sheets

according to Mr. Scobee, was “ to survey the situation and

find out what I could about individual teachers, looking to

their improvement” (346).

Salaries for the year 1941-42 were not based on rating

of teachers. The salaries for the school year 1942-43 were

not changed from the salaries for the year 1941-42 with one

exception. Salaries for the year 1942-43 were fixed in May,

1942-43 (469-826), while the final reports of the rating sheets

were not completed before June of 1942 (468).

The rating sheets prepared after the suit was filed and

the answer filed and after consultation with lawyers for the

school hoard on its face seemed to completely justify the

difference in salary (848). Defendants’ Exhibit 5 which

included the names, professional training, experience, rating

and salary of each teacher in the Little Rock School system

was on mimeographed sheets of paper in which the name of

the teacher, the name of the school, the qualifications, ex

perience and salary were mimeographed while the ratings

were typed in subsequent to the preparation of the mimeo

graphed sheets themselves (467).

It is, therefore, clear that: (1) Superintendent Scobee

and his assistants actually completed the rating of teachers

after he had given to his lawyers the factual information for

the answer in this case; (2) the final composite rating sheets

were mimeographed showing name of teachers, qualifica

tions, experience, school taught and salary with blank

spaces for ratings; (3) this material was before him when

the ratings were made; (4) Superintendent Scobee admitted

that on the levels of qualifications and experience a com

parison will show that all Negro teachers get less salary

(862); (5) the ratings were later typed in. An examina

tion of this composite rating sheet will show that wherever

37

it appears that teachers with certain qualifications and ex

perience (Negroes) get less salary than white teachers with

equal qualifications and experience lower ratings for these

teachers were typed in. As a matter of fact, Mr. Scobee

testified that in practically all instances the rating figures

prepared after the case and answer were filed seemed to

completely justify the difference in salaries between white

and Negro teachers (848-849).

The composite rating sheets should not have been ad

mitted in evidence. They were prepared under the direc

tion of the Superintendent and were not prepared for either

the School Board or the general public. They were not pub

lic documents. The ratings were not only hearsay but were

conclusions and not facts. There is no statutory authority

requiring the making of the rating sheets.

The law on this point is quite clear and has been set out

as follows:

“ According to the theory advanced by some courts

a record of primary facts made by a public official in

performance of official duty is, or may be made by

litigation, competent prima facie evidence as to the

existence of the fact, but records of investigations

and inquiries conducted either voluntarily or pur

suant to requirement of law by public officers con

cerning causes and effects and involving the exercise

of judgment and discretion, expression of opinion,

and the making of conclusions, are not admissible in

evidence as public records.”

20 American Jurisprudence 886, p. 1027.

In the cases on this point the line is drawn between rec

ords containing facts and those containing conclusions and

opinions involving discretion. In the instant case the rat

ings were based solely on conclusions of several people and

38

did not contain facts. The records, therefore, were not

admissible:

“ In order to be admissible, a report or document

prepared by a public official must contain facts and

not conclusions involving the exercise of judgment or

the expression of opinion. The subject matter must

relate to facts which are of a public nature, it must be

retained for the benefit of the public and there must

be express statutory authority to compile the report.”

Steel v. Johnson, 115 P. (2d) 145, 150.

See also:

Chamberlain v. Kane, 264 S. W. 24 (1924);

State v. Bolen, 142 Wash. 653, 254 P. 445.

IV.

The composite rating sheets are entitled to no

weight in determining whether the policy, custom and

usage of fixing salaries in Little Rock is based on race.

Mr. Scobee testified that he did considerable studying on

the question of school administration and that he had done

quite a bit of studying on the question of methods of fixing

salaries in various school systems. On the question of the

proper methods of fixing salaries, Mr. Scobee testified that

paying salaries pursuant to the rating of teachers’ ability

was not used. He testified further that of the several school

systems he had studied, he did not know of any other school

system in the country using rating as a basis of fixing of

salaries. He also testified that he was familiar with the

several surveys conducted by the National Educational

Association and that these surveys revealed that ratings

are never used in fixing salaries (293-294).

39

As to the ratings used in this case and particularly the

final rating sheets, Mr. Scobee’s response to a question by

the Court was as follows :

“ Q. Whatever its contents are, you considered

them in fixing salaries? A. Never at any time. This

was not for the purpose of fixing salaries” (470).

Mr. Scobee testified further that “ I have not used the

rating, and have not claimed definite accuracy for it.”

These rating sheets were supposed to be used primarily for

helping to correct teaching (591). These rating sheets are

then supposed to be given to the individual teacher so that

they can correct their teaching (591). However, according

to Mr. Scobee, in response to a question as to whether or not

ratings are ever used for the purpose of fixing salaries,

replied, “ I do not believe they are ever used, be rare in

stances if they were” (592). The following testimony of

Mr. Scobee on this point is likewise quite interesting:

“ Q. Do you know of any school system in the

country that bases its salary on a rating of teachers

similar to that there [rating sheets] ? A. I do not

recall any.

Q. So Little Rock is novel in that? A. Little Rock

is not basing its salary on these ratings.” (Empha

sis ours.) (847.)

How the Ratings Were Made in Little Rock.

On several occasions Mr. Scobee testified that the par

ticular ratings in question were not accurate and that there

were too many personal elements involved to be accurate

(591, 592, 847). Supervisor Webb testified that he was not

satisfied with his own rating (809-810). Mr. Webb, under

examination by his attorney, admitted that he transferred a

white teacher in his school, Elizabeth Goetz, because “ she

40

just wasn’t filling the job ” (799). However, on the com

posite rating sheet Miss Goetz is rated as “ 3” which seems

to justify her salary of $852. Superintendent Scobee testi

fied that another white teacher, Bernice Britt, was so ineffi

cient he had to discharge her yet her rating appeared on the

composite rating sheet as “ 3” (847). This was the only

way of justifying her salary.

One supervisor testified that in order to properly rate a

teacher it would take several visits to observe the teacher

and that each visit would have to be more than twenty min

utes (732). However, Mr. Scobee “ rated” the plaintiff in

this case after only one visit of ten minutes (209-210).

According to the evidence of the defendants one super

visor testified that she would prefer at least a year of

observation before undertaking the job of rating a teacher

(733). However, Mrs. Allison testified that although she

rated some Negro teachers she only visited these teachers

about once a year (755); and, as a matter of fact, some

Negro schools were not visited at all during the past school

year (758). Mrs. Allison testified further that in rating

these teachers she did not use any previous knowledge of

the teachers’ ability (760).

Miss Hayes testified she had not visited some Negro

schools in the past two years (771). Mr. Webb testified that

durng the rating of teachers he was “ conscious that some

were white and some are colored” (783). He, however,

testified that there was “ no intentional discrimination”

(781).

Elementary Schools.

In the system of rating used in Little Rock during the

Spring of this year, it was agreed that the better procedure

would be to have the principals rate their own teachers

(811). Following this procedure the white principals of

41

both elementary and high schools rated their teachers (811-

867). However, although the Negro principals were consid